Golden Bull (1356) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

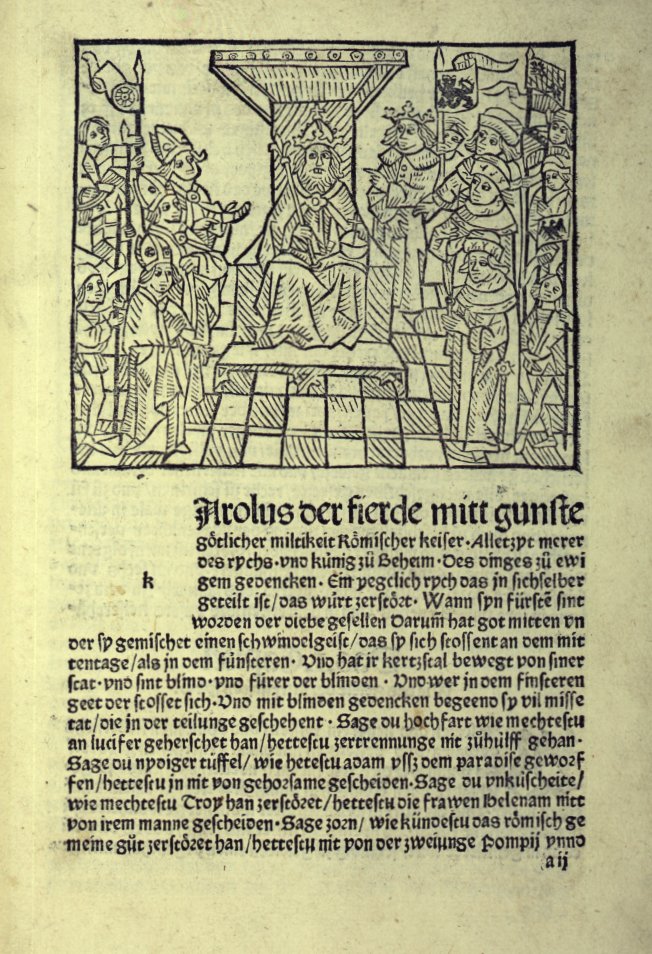

The Golden Bull of 1356 (, , , , ) was a decree issued by the Imperial Diet at Nuremberg and Metz ( Diet of Metz, 1356/57) headed by the Emperor Charles IV which fixed, for a period of more than four hundred years, important aspects of the constitutional structure of the Holy Roman Empire. It was named the '' Golden Bull'' for the golden seal it carried.

In June 2013 the Golden Bull was included in the UNESCO's Memory of the World Register.

Secondly, the principle of majority voting was explicitly stated for the first time in the Empire. The Bull prescribed that four (out of seven) votes would always suffice to elect a new King; as a result, three Electors could no longer block the election. Thirdly, the Electoral principalities were declared indivisible, and succession to them was regulated to ensure that the votes would never be divided. Finally, the Bull cemented a number of privileges for the Electors, confirming their elevated role in the Empire. It is therefore also a milestone in the establishment of largely independent states in the Empire, a process to be concluded only centuries later, notably with the

Secondly, the principle of majority voting was explicitly stated for the first time in the Empire. The Bull prescribed that four (out of seven) votes would always suffice to elect a new King; as a result, three Electors could no longer block the election. Thirdly, the Electoral principalities were declared indivisible, and succession to them was regulated to ensure that the votes would never be divided. Finally, the Bull cemented a number of privileges for the Electors, confirming their elevated role in the Empire. It is therefore also a milestone in the establishment of largely independent states in the Empire, a process to be concluded only centuries later, notably with the  This codification of prince-electors, though largely based on precedence, was not uncontroversial, especially in regard to the two chief rivals of the ruling House of Luxembourg:

*The

This codification of prince-electors, though largely based on precedence, was not uncontroversial, especially in regard to the two chief rivals of the ruling House of Luxembourg:

*The

The complete Golden Bull of 1356

translated into English.

Selections from the Golden Bull

from th

at th

Fordham University Centre for Mediaeval Studies

in Latin, comparative listing of all five initial copies. * Bernd-Ulrich Hergemöller, Golden Bull, 1356, published 8 March 2010, english version published 27 February 2020 ; in

Historisches Lexikon Bayerns

Background

According to the written text of the Golden Bull of 1356: Though the election of theKing of the Romans

King of the Romans ( la, Rex Romanorum; german: König der Römer) was the title used by the king of Germany following his election by the princes from the reign of Henry II (1002–1024) onward.

The title originally referred to any German k ...

by the chief ecclesiastical and secular princes of the Holy Roman Empire was well established, disagreements about the process and papal involvement had repeatedly resulted in controversies, most recently in 1314 when Louis of Bavaria Ludwig of Bavaria or Louis of Bavaria may refer to:

Dukes

*Louis I, Duke of Bavaria (1173–1231), Duke of Bavaria in 1183 and the Count of Palatinate of the Rhine in 1214. He was a son of Otto I

*Louis II, Duke of Bavaria (1229–1294), Duke of Ba ...

and Frederick of Austria had been elected by opposing sets of electors. Louis, who had eventually subdued his rival's claim on the battlefield, made a first attempt to clarify the process in the Declaration of Rhense of 1338, which renounced any papal involvement and had restricted the right to choose a new king to the prince-electors. The Golden Bull, promulgated by Louis's successor and rival, Charles IV, was more precise in several ways.

Prince-electors

Firstly, the Bull explicitly named the seven Prince-electors (''Kurfürsten'') who were to choose the King and also defined the ''Reichserzämter'', their (largely ceremonial) offices at court: Secondly, the principle of majority voting was explicitly stated for the first time in the Empire. The Bull prescribed that four (out of seven) votes would always suffice to elect a new King; as a result, three Electors could no longer block the election. Thirdly, the Electoral principalities were declared indivisible, and succession to them was regulated to ensure that the votes would never be divided. Finally, the Bull cemented a number of privileges for the Electors, confirming their elevated role in the Empire. It is therefore also a milestone in the establishment of largely independent states in the Empire, a process to be concluded only centuries later, notably with the

Secondly, the principle of majority voting was explicitly stated for the first time in the Empire. The Bull prescribed that four (out of seven) votes would always suffice to elect a new King; as a result, three Electors could no longer block the election. Thirdly, the Electoral principalities were declared indivisible, and succession to them was regulated to ensure that the votes would never be divided. Finally, the Bull cemented a number of privileges for the Electors, confirming their elevated role in the Empire. It is therefore also a milestone in the establishment of largely independent states in the Empire, a process to be concluded only centuries later, notably with the Peace of Westphalia

The Peace of Westphalia (german: Westfälischer Friede, ) is the collective name for two peace treaties signed in October 1648 in the Westphalian cities of Osnabrück and Münster. They ended the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) and brought pea ...

of 1648.

This codification of prince-electors, though largely based on precedence, was not uncontroversial, especially in regard to the two chief rivals of the ruling House of Luxembourg:

*The

This codification of prince-electors, though largely based on precedence, was not uncontroversial, especially in regard to the two chief rivals of the ruling House of Luxembourg:

*The House of Wittelsbach

The House of Wittelsbach () is a German dynasty, with branches that have ruled over territories including Bavaria, the Palatinate, Holland and Zeeland, Sweden (with Finland), Denmark, Norway, Hungary (with Romania), Bohemia, the Electorate ...

ruled the Duchy of Bavaria as well as the County Palatinate. Dynastic divisions had caused the two territories to devolve upon distinct branches of the house. The Treaty of Pavia

The Treaty of Pavia was signed in Pavia on October 9, 1617, between representatives of the Spanish Empire and the Duchy of Savoy. Based on the terms of the accord, Savoy returned the Duchy of Montferrat to the Duchy of Mantua. Moreover, the treaty ...

, which in 1329 restored the Palatinate branch, stipulated that Bavaria and the Palatinate would alternate in future elections, but the Golden Bull fixed the electoral vote upon the Palatinate and not upon Bavaria, partly because Charles's predecessor and rival Louis IV was of that branch. Louis IV's sons, Louis V Louis V may refer to:

* Louis V of France (967–987)

* Louis IV, Holy Roman Emperor and V of Germany (1282–1347)

* Louis V, Duke of Bavaria (1315–1361)

* Louis V, Elector Palatine (ruled 1508–1544)

* Louis V, Landgrave of Hesse-Darmstadt (ru ...

and Stephen II of Bavaria, protested this omission, feeling that Bavaria, one of the original duchies of the realm and their family's chief territory for over 170 years, deserved primacy over the Palatinate. The omission of Bavaria from the list of prince-electors also allowed Bavaria, which had only recently been reunited, to fall into dynastic fragmentation again. Brandenburg was in the hands of the Bavarian Wittelsbachs (though held by a junior member of the house) in 1356; they eventually lost the territory to the Luxemburgs in 1373, leaving the Bavarian branch without representation in the electoral college until 1623.

*The House of Habsburg, long-time rivals of the Luxembourgs, were completely omitted from the list of prince-electors, leading to decreased political influence and dynastic fragmentation. In retaliation, Duke Rudolf IV

Rudolf IV (1 November 1339 – 27 July 1365), also called Rudolf the Founder (german: der Stifter), was a scion of the House of Habsburg who ruled as duke of Austria (self-proclaimed archduke), Styria and Carinthia from 1358, as well as count ...

, one of the dukes of fragmented Austria, had the '' Privilegium Maius'' forged, a document supposedly issued by Emperor Frederick Barbarossa

Frederick Barbarossa (December 1122 – 10 June 1190), also known as Frederick I (german: link=no, Friedrich I, it, Federico I), was the Holy Roman Emperor from 1155 until his death 35 years later. He was elected King of Germany in Frankfurt on ...

. The document gave Austria – elevated to the position of an Archduchy

Archduke (feminine: Archduchess; German: ''Erzherzog'', feminine form: ''Erzherzogin'') was the title borne from 1358 by the Habsburg rulers of the Archduchy of Austria, and later by all senior members of that dynasty. It denotes a rank within ...

– special privileges, including primogeniture

Primogeniture ( ) is the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn legitimate child to inherit the parent's entire or main estate in preference to shared inheritance among all or some children, any illegitimate child or any collateral relativ ...

. While ignored by the Emperor and other princes at the time, the document was eventually ratified when Frederick of Austria himself became Emperor in the 15th century. Still, the Habsburgs remained without an electoral vote until they succeeded to the Kingdom of Bohemia in 1526.

Procedures

The bull regulated the whole election process in great detail, listing explicitly where, when, and under which circumstances what should be done by whom, not only for the prince-electors but also (for example) for the population of Frankfurt, where the elections were to be held, and also for the counts of the regions the prince-electors had to travel through to get there. The decision to hold the elections in Frankfurt reflected a traditional feeling dating from East Frankish days that both election and coronation ought to take place on Frankish soil. However, the election location was not the only specified location; the bull specified that the coronation would take place inAachen

Aachen ( ; ; Aachen dialect: ''Oche'' ; French and traditional English: Aix-la-Chapelle; or ''Aquisgranum''; nl, Aken ; Polish: Akwizgran) is, with around 249,000 inhabitants, the 13th-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia, and the 28th- ...

, and Nuremberg would be the place where the first diet of a reign should be held. The elections were to be concluded within thirty days; failing that, the bull prescribed that the prince-electors were to receive only bread and water until they had decided:

Besides regulating the election process, the chapters of the Golden Bull contained many minor decrees. For instance, it also defined the order of marching when the emperor was present, both with and without his insignia. A relatively major decision was made in chapter 15, where Charles IV outlawed any , and , meaning in particular the city alliances (), but also other communal leagues that had sprung up through the communal movement in mediaeval Europe

Medieval communes in the European Middle Ages had sworn allegiances of mutual defense (both physical defense and of traditional freedoms) among the citizens of a town or city. These took many forms and varied widely in organization and makeup.

C ...

. Most were subsequently dissolved, sometimes forcibly, and where refounded, their political influence was much reduced. Thus the Golden Bull also strengthened the nobility in general to the detriment of the cities.

The pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

's involvement with the Golden Bull of 1356 was basically nonexistent, which was significant in the history of relations between the popes and the emperors. When Charles IV laid down procedure for electing a King of the Romans, he mentioned nothing about receiving papal confirmation of the election. However, Pope Innocent VI

Pope Innocent VI ( la, Innocentius VI; 1282 or 1295 – 12 September 1362), born Étienne Aubert, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 18 December 1352 to his death in September 1362. He was the fifth Avignon pope a ...

did not protest this because he needed Charles’s support against the Visconti

Visconti is a surname which may refer to:

Italian noble families

* Visconti of Milan, ruled Milan from 1277 to 1447

** Visconti di Modrone, collateral branch of the Visconti of Milan

* Visconti of Pisa and Sardinia, ruled Gallura in Sardinia from ...

. Pope Innocent continued to have good relations with Charles IV after the Golden Bull of 1356 until the former's death in 1362.D. S. Chambers, ''Popes, Cardinals and War'' (London: I.B. Tauris, 2006), 28.

References

Further reading

*External links

The complete Golden Bull of 1356

translated into English.

Selections from the Golden Bull

from th

at th

Fordham University Centre for Mediaeval Studies

in Latin, comparative listing of all five initial copies. * Bernd-Ulrich Hergemöller, Golden Bull, 1356, published 8 March 2010, english version published 27 February 2020 ; in

Historisches Lexikon Bayerns

Literature

* Bryce, James, The Holy Roman Empire (London: The Macmillan Company, A New Edition, 1978), 243. * Chambers. D.S., Popes, Cardinals and War (London: I.B. Tauris, 2006), 28. * Renouard, Yves, The Avignon Papacy 1305–1403 (Connecticut : Archon Books, 1970), 127. * Heer, Friedrich, trans. Janet Sondheimer, The Holy Roman Empire (New York: Federick A. Praeger Publishers, 1968), 117. {{Authority control Golden Bulls History of Frankfurt 1350s in law Political charters Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor Manuscripts of the Austrian National Library 1350s in the Holy Roman Empire 1356 in Europe Imperial election (Holy Roman Empire)