Glucose is a

sugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose

Glucose is a sugar with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecul ...

with the

molecular formula

A chemical formula is a way of presenting information about the chemical proportions of atoms that constitute a particular chemical compound or molecule, using chemical element symbols, numbers, and sometimes also other symbols, such as paren ...

, which is often abbreviated as Glc. It is overall the most abundant

monosaccharide

Monosaccharides (from Greek '' monos'': single, '' sacchar'': sugar), also called simple sugars, are the simplest forms of sugar and the most basic units (monomers) from which all carbohydrates are built.

Chemically, monosaccharides are polyhy ...

,

a subcategory of

carbohydrate

A carbohydrate () is a biomolecule composed of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), and oxygen (O) atoms. The typical hydrogen-to-oxygen atomic ratio is 2:1, analogous to that of water, and is represented by the empirical formula (where ''m'' and ''n'' ...

s. It is mainly made by

plants

Plants are the eukaryotes that form the kingdom Plantae; they are predominantly photosynthetic. This means that they obtain their energy from sunlight, using chloroplasts derived from endosymbiosis with cyanobacteria to produce sugars f ...

and most

algae

Algae ( , ; : alga ) is an informal term for any organisms of a large and diverse group of photosynthesis, photosynthetic organisms that are not plants, and includes species from multiple distinct clades. Such organisms range from unicellular ...

during

photosynthesis

Photosynthesis ( ) is a system of biological processes by which photosynthetic organisms, such as most plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, convert light energy, typically from sunlight, into the chemical energy necessary to fuel their metabo ...

from water and carbon dioxide, using energy from sunlight. It is used by plants to make

cellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the chemical formula, formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to many thousands of glycosidic bond, β(1→4) linked glucose, D-glucose units. Cellulose is an important s ...

, the most abundant carbohydrate in the world, for use in

cell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer that surrounds some Cell type, cell types, found immediately outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. Primarily, it provides the cell with structural support, shape, protection, ...

s, and by all living

organisms

An organism is any living thing that functions as an individual. Such a definition raises more problems than it solves, not least because the concept of an individual is also difficult. Many criteria, few of them widely accepted, have been pr ...

to make

adenosine triphosphate

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is a nucleoside triphosphate that provides energy to drive and support many processes in living cell (biology), cells, such as muscle contraction, nerve impulse propagation, and chemical synthesis. Found in all known ...

(ATP), which is used by the cell as energy.

In

energy metabolism

Bioenergetics is a field in biochemistry and cell biology that concerns energy flow through living systems. This is an active area of biological research that includes the study of the transformation of energy in living organisms and the study ...

, glucose is the most important source of energy in all

organism

An organism is any life, living thing that functions as an individual. Such a definition raises more problems than it solves, not least because the concept of an individual is also difficult. Many criteria, few of them widely accepted, have be ...

s. Glucose for metabolism is stored as a

polymer

A polymer () is a chemical substance, substance or material that consists of very large molecules, or macromolecules, that are constituted by many repeat unit, repeating subunits derived from one or more species of monomers. Due to their br ...

, in plants mainly as

amylose

Amylose is a polysaccharide made of α-D-glucose units, bonded to each other through α(1→4) glycosidic bonds. It is one of the two components of starch, making up approximately 20–25% of it. Because of its tightly packed Helix, helical struct ...

and

amylopectin Amylopectin is a water-insoluble polysaccharide and highly branched polymer of α-glucose units found in plants. It is one of the two components of starch, the other being amylose.

Plants store starch within specialized organelles called amyloplas ...

, and in animals as

glycogen

Glycogen is a multibranched polysaccharide of glucose that serves as a form of energy storage in animals, fungi, and bacteria. It is the main storage form of glucose in the human body.

Glycogen functions as one of three regularly used forms ...

. Glucose circulates in the blood of animals as

blood sugar

The blood sugar level, blood sugar concentration, blood glucose level, or glycemia is the measure of glucose concentrated in the blood. The body tightly regulates blood glucose levels as a part of metabolic homeostasis.

For a 70 kg (1 ...

.

The naturally occurring form is -glucose, while its

stereoisomer

In stereochemistry, stereoisomerism, or spatial isomerism, is a form of isomerism in which molecules have the same molecular formula and sequence of bonded atoms (constitution), but differ in the three-dimensional orientations of their atoms in ...

-glucose is produced synthetically in comparatively small amounts and is less biologically active.

Glucose is a monosaccharide containing six carbon atoms and an

aldehyde

In organic chemistry, an aldehyde () (lat. ''al''cohol ''dehyd''rogenatum, dehydrogenated alcohol) is an organic compound containing a functional group with the structure . The functional group itself (without the "R" side chain) can be referred ...

group, and is therefore an

aldohexose

In chemistry, a hexose is a monosaccharide (simple sugar) with six carbon atoms. The chemical formula for all hexoses is , and their molecular weight is 180.156 g/mol.

Hexoses exist in two forms, open-chain or cyclic, that easily convert into e ...

. The glucose molecule can exist in an open-chain (acyclic) as well as ring (cyclic) form. Glucose is naturally occurring and is found in its free state in fruits and other parts of plants. In animals, it is released from the breakdown of glycogen in a process known as

glycogenolysis

Glycogenolysis is the breakdown of glycogen (n) to glucose-1-phosphate and glycogen (n-1). Glycogen branches are catabolized by the sequential removal of glucose monomers via phosphorolysis, by the enzyme glycogen phosphorylase.

Mechanis ...

.

Glucose, as

intravenous sugar solution

Intravenous sugar solution, also known as dextrose solution, is a mixture of dextrose (glucose) and water. It is used to treat low blood sugar or water loss without electrolyte loss. Water loss without electrolyte loss may occur in fever, hype ...

, is on the

World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines

The WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (aka Essential Medicines List or EML), published by the World Health Organization (WHO), contains the medications considered to be most effective and safe to meet the most important needs in a health s ...

.

It is also on the list in combination with

sodium chloride

Sodium chloride , commonly known as Salt#Edible salt, edible salt, is an ionic compound with the chemical formula NaCl, representing a 1:1 ratio of sodium and chloride ions. It is transparent or translucent, brittle, hygroscopic, and occurs a ...

(table salt).

The name glucose is derived from

Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

() 'wine, must', from () 'sweet'. The suffix ''

-ose

The suffix ''-ose'' () is used in organic chemistry to form the names of sugars. This Latin suffix means "full of", "abounding in", "given to", or "like". Numerous systems exist to name specific sugars more descriptively. The suffix is also used mo ...

'' is a chemical classifier denoting a sugar.

History

Glucose was first isolated from

raisin

A raisin is a Dried fruit, dried grape. Raisins are produced in many regions of the world and may be eaten raw or used in cooking, baking, and brewing. In the United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland, Ireland, New Zealand, Australia and South Afri ...

s in 1747 by the German chemist

Andreas Marggraf

Andreas Sigismund Marggraf (; 3 March 1709 – 7 August 1782) was a German chemist from Berlin, then capital of the Margraviate of Brandenburg, and a pioneer of analytical chemistry. He isolated zinc in 1746 by heating calamine and carbon. Though ...

.

Glucose was discovered in grapes by another German chemist

Johann Tobias Lowitzin 1792, and distinguished as being different from cane sugar (

sucrose

Sucrose, a disaccharide, is a sugar composed of glucose and fructose subunits. It is produced naturally in plants and is the main constituent of white sugar. It has the molecular formula .

For human consumption, sucrose is extracted and refined ...

). Glucose is the term coined by

Jean Baptiste Dumas

Jean Baptiste André Dumas (; 14 July 180010 April 1884) was a French chemist, best known for his works on organic analysis and synthesis, as well as the determination of atomic weights (relative atomic masses) and molecular weights by measuring ...

in 1838, which has prevailed in the chemical literature.

Friedrich August Kekulé proposed the term dextrose (from the

Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

, meaning "right"), because in aqueous solution of glucose, the plane of linearly polarized light is turned to the right. In contrast,

l-fructose

Fructose (), or fruit sugar, is a ketonic simple sugar found in many plants, where it is often bonded to glucose to form the disaccharide sucrose. It is one of the three dietary monosaccharides, along with glucose and galactose, that are absorb ...

(usually referred to as -fructose) (a ketohexose) and l-glucose (-glucose) turn linearly

polarized light to the left. The earlier notation according to the rotation of the plane of linearly polarized light (''d'' and ''l''-nomenclature) was later abandoned in favor of the

- and -notation, which refers to the absolute configuration of the asymmetric center farthest from the carbonyl group, and in concordance with the configuration of - or -glyceraldehyde.

[John F. Robyt: ''Essentials of Carbohydrate Chemistry''. Springer Science & Business Media, 2012, . p. 7.]

Since glucose is a basic necessity of many organisms, a correct understanding of its

chemical

A chemical substance is a unique form of matter with constant chemical composition and characteristic properties. Chemical substances may take the form of a single element or chemical compounds. If two or more chemical substances can be combin ...

makeup and structure contributed greatly to a general advancement in

organic chemistry

Organic chemistry is a subdiscipline within chemistry involving the science, scientific study of the structure, properties, and reactions of organic compounds and organic matter, organic materials, i.e., matter in its various forms that contain ...

. This understanding occurred largely as a result of the investigations of

Emil Fischer

Hermann Emil Louis Fischer (; 9 October 1852 – 15 July 1919) was a German chemist and List of Nobel laureates in Chemistry, 1902 recipient of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He discovered the Fischer esterification. He also developed the Fisch ...

, a German chemist who received the 1902

Nobel Prize in Chemistry

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry () is awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to scientists in the various fields of chemistry. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Alfred Nobel in 1895, awarded for outst ...

for his findings. The synthesis of glucose established the structure of organic material and consequently formed the first definitive validation of

Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff

Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff Jr. (; 30 August 1852 – 1 March 1911) was a Dutch physical chemistry, physical chemist. A highly influential theoretical chemistry, theoretical chemist of his time, Van 't Hoff was the first winner of the Nobe ...

's theories of chemical kinetics and the arrangements of chemical bonds in carbon-bearing molecules. Between 1891 and 1894, Fischer established the

stereochemical

Stereochemistry, a subdiscipline of chemistry, studies the spatial arrangement of atoms that form the structure of molecules and their manipulation. The study of stereochemistry focuses on the relationships between stereoisomers, which are defined ...

configuration of all the known sugars and correctly predicted the possible

isomer

In chemistry, isomers are molecules or polyatomic ions with identical molecular formula – that is, the same number of atoms of each element (chemistry), element – but distinct arrangements of atoms in space. ''Isomerism'' refers to the exi ...

s, applying

Van 't Hoff equation

The Van 't Hoff equation relates the change in the equilibrium constant, , of a chemical reaction to the change in temperature, ''T'', given the standard enthalpy change, , for the process. The subscript r means "reaction" and the superscript \om ...

of asymmetrical carbon atoms. The names initially referred to the natural substances. Their

enantiomers

In chemistry, an enantiomer (Help:IPA/English, /ɪˈnænti.əmər, ɛ-, -oʊ-/ Help:Pronunciation respelling key, ''ih-NAN-tee-ə-mər''), also known as an optical isomer, antipode, or optical antipode, is one of a pair of molecular entities whi ...

were given the same name with the introduction of systematic nomenclatures, taking into account absolute stereochemistry (e.g.

Fischer nomenclature, / nomenclature).

For the discovery of the metabolism of glucose

Otto Meyerhof

Otto Fritz Meyerhof (; 12 April 1884 – 6 October 1951) was a German physician and biochemist who won the 1922 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine.

Biography

Otto Fritz Meyerhof was born in Hannover, at Theaterplatz 16A (now:Rathenaustrasse ...

received the

Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine () is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, acco ...

in 1922.

Hans von Euler-Chelpin

Hans Karl August Simon Euler-Chelpin, since 28 July 1884 von Euler-Chelpin (15 February 1873 – 6 November 1964), was a German-born Swedish biochemist. He won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1929 with Arthur Harden for their investigations on ...

was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry along with

Arthur Harden

Sir Arthur Harden, FRS (12 October 1865 – 17 June 1940) was a British biochemist. He shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1929 with Hans Karl August Simon von Euler-Chelpin for their investigations into the fermentation of sugar and ferme ...

in 1929 for their "research on the

fermentation

Fermentation is a type of anaerobic metabolism which harnesses the redox potential of the reactants to make adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and organic end products. Organic molecules, such as glucose or other sugars, are catabolized and reduce ...

of sugar and their share of enzymes in this process". In 1947,

Bernardo Houssay (for his discovery of the role of the

pituitary gland

The pituitary gland or hypophysis is an endocrine gland in vertebrates. In humans, the pituitary gland is located at the base of the human brain, brain, protruding off the bottom of the hypothalamus. The pituitary gland and the hypothalamus contr ...

in the metabolism of glucose and the derived carbohydrates) as well as

Carl Carl may refer to:

*Carl, Georgia, city in USA

*Carl, West Virginia, an unincorporated community

*Carl (name), includes info about the name, variations of the name, and a list of people with the name

*Carl², a TV series

* "Carl", an episode of tel ...

and

Gerty Cori

Gerty Theresa Cori (; August 15, 1896 – October 26, 1957) was a Bohemian-Austrian and American biochemist who in 1947 was the third woman to win a Nobel Prize in science, and the first woman to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Me ...

(for their discovery of the conversion of glycogen from glucose) received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. In 1970,

Luis Leloir

Luis Federico Leloir (September 6, 1906 – December 2, 1987) was an Argentine physician and biochemist who received the 1970 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his discovery of the metabolic pathways by which carbohydrates are synthesized and co ...

was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of glucose-derived sugar nucleotides in the biosynthesis of carbohydrates.

Chemical and physical properties

Glucose forms white or colorless solids that are highly

soluble

In chemistry, solubility is the ability of a substance, the solute, to form a solution with another substance, the solvent. Insolubility is the opposite property, the inability of the solute to form such a solution.

The extent of the solubi ...

in water and

acetic acid

Acetic acid , systematically named ethanoic acid , is an acidic, colourless liquid and organic compound with the chemical formula (also written as , , or ). Vinegar is at least 4% acetic acid by volume, making acetic acid the main compone ...

but poorly soluble in

methanol

Methanol (also called methyl alcohol and wood spirit, amongst other names) is an organic chemical compound and the simplest aliphatic Alcohol (chemistry), alcohol, with the chemical formula (a methyl group linked to a hydroxyl group, often ab ...

and

ethanol

Ethanol (also called ethyl alcohol, grain alcohol, drinking alcohol, or simply alcohol) is an organic compound with the chemical formula . It is an Alcohol (chemistry), alcohol, with its formula also written as , or EtOH, where Et is the ps ...

. They melt at (''α'') and (''beta''),

decompose

Decomposition is the process by which dead organic substances are broken down into simpler organic or inorganic matter such as carbon dioxide, water, simple sugars and mineral salts. The process is a part of the nutrient cycle and is essen ...

starting at with release of various volatile products, ultimately leaving a residue of

carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalence, tetravalent—meaning that its atoms are able to form up to four covalent bonds due to its valence shell exhibiting 4 ...

.

Glucose has a

pKa value of 12.16 at in water.

With six carbon atoms, it is classed as a

hexose

In chemistry, a hexose is a monosaccharide (simple sugar) with six carbon atoms. The chemical formula for all hexoses is , and their molecular weight is 180.156 g/mol.

Hexoses exist in two forms, open-chain or cyclic, that easily convert into ...

, a subcategory of the

monosaccharide

Monosaccharides (from Greek '' monos'': single, '' sacchar'': sugar), also called simple sugars, are the simplest forms of sugar and the most basic units (monomers) from which all carbohydrates are built.

Chemically, monosaccharides are polyhy ...

s. -Glucose is one of the sixteen

aldohexose

In chemistry, a hexose is a monosaccharide (simple sugar) with six carbon atoms. The chemical formula for all hexoses is , and their molecular weight is 180.156 g/mol.

Hexoses exist in two forms, open-chain or cyclic, that easily convert into e ...

stereoisomer

In stereochemistry, stereoisomerism, or spatial isomerism, is a form of isomerism in which molecules have the same molecular formula and sequence of bonded atoms (constitution), but differ in the three-dimensional orientations of their atoms in ...

s. The -

isomer

In chemistry, isomers are molecules or polyatomic ions with identical molecular formula – that is, the same number of atoms of each element (chemistry), element – but distinct arrangements of atoms in space. ''Isomerism'' refers to the exi ...

, -glucose, also known as dextrose, occurs widely in nature, but the -isomer,

-glucose, does not. Glucose can be obtained by

hydrolysis

Hydrolysis (; ) is any chemical reaction in which a molecule of water breaks one or more chemical bonds. The term is used broadly for substitution reaction, substitution, elimination reaction, elimination, and solvation reactions in which water ...

of carbohydrates such as milk sugar (

lactose

Lactose is a disaccharide composed of galactose and glucose and has the molecular formula C12H22O11. Lactose makes up around 2–8% of milk (by mass). The name comes from (Genitive case, gen. ), the Latin word for milk, plus the suffix ''-o ...

), cane sugar (sucrose),

maltose

}

Maltose ( or ), also known as maltobiose or malt sugar, is a disaccharide formed from two units of glucose joined with an α(1→4) bond. In the isomer isomaltose, the two glucose molecules are joined with an α(1→6) bond. Maltose is the tw ...

,

cellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the chemical formula, formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to many thousands of glycosidic bond, β(1→4) linked glucose, D-glucose units. Cellulose is an important s ...

,

glycogen

Glycogen is a multibranched polysaccharide of glucose that serves as a form of energy storage in animals, fungi, and bacteria. It is the main storage form of glucose in the human body.

Glycogen functions as one of three regularly used forms ...

, etc. Dextrose is commonly commercially manufactured from

starches

Starch or amylum is a polymeric carbohydrate consisting of numerous glucose units joined by glycosidic bonds. This polysaccharide is produced by most green plants for energy storage. Worldwide, it is the most common carbohydrate in human die ...

, such as

corn starch

Cornflour, cornstarch, maize starch, or corn starch (American English) is the starch derived from corn (maize) grain. The starch is obtained from the endosperm of the seed, kernel. Corn starch is a common food ingredient, often used to thick ...

in the US and Japan, from potato and wheat starch in Europe, and from

tapioca starch

Tapioca (; ) is a starch extracted from the tubers of the cassava plant (''Manihot esculenta,'' also known as manioc), a species native to the North Region, Brazil, North and Northeast Region, Brazil, Northeast regions of Brazil, but which has ...

in tropical areas. The manufacturing process uses hydrolysis via pressurized steaming at controlled

pH in a jet followed by further enzymatic depolymerization. Unbonded glucose is one of the main ingredients of

honey

Honey is a sweet and viscous substance made by several species of bees, the best-known of which are honey bees. Honey is made and stored to nourish bee colonies. Bees produce honey by gathering and then refining the sugary secretions of pl ...

.

The term ''dextrose'' is often used in a clinical (related to patient's health status) or nutritional context (related to dietary intake, such as food labels or dietary guidelines), while "glucose" is used in a biological or physiological context (chemical processes and molecular interactions),

but both terms refer to the same molecule, specifically D-glucose.

''Dextrose monohydrate'' is the hydrated form of D-glucose, meaning that it is a glucose molecule with an additional water molecule attached.

Its chemical formula is · .

Dextrose monohydrate is also called ''hydrated D-glucose'', and commonly manufactured from plant starches.

Dextrose monohydrate is utilized as the predominant type of dextrose in food applications, such as beverage mixes—it is a common form of glucose widely used as a nutrition supplement in production of foodstuffs. Dextrose monohydrate is primarily consumed in North America as a

corn syrup

Corn syrup is a food syrup that is made from the starch of corn/maize and contains varying amounts of sugars: glucose, maltose and higher oligosaccharides, depending on the grade. Corn syrup is used in foods to soften Mouthfeel, texture, add vol ...

or

high-fructose corn syrup

High-fructose corn syrup (HFCS), also known as glucose–fructose, isoglucose, and glucose–fructose syrup, is a sweetener made from corn starch. As in the production of conventional corn syrup, the starch is broken down into glucose by enzy ...

.

''Anhydrous dextrose'', on the other hand, is glucose that does not have any water molecules attached to it.

Anhydrous chemical substances are commonly produced by eliminating water from a hydrated substance through methods such as heating or drying up (desiccation).

Dextrose monohydrate can be dehydrated to anhydrous dextrose in industrial setting. Dextrose monohydrate is composed of approximately 9.5% water by mass; through the process of dehydration, this water content is eliminated to yield anhydrous (dry) dextrose.

Anhydrous dextrose has the chemical formula , without any water molecule attached which is the same as glucose.

Anhydrous dextrose on open air tends to absorb moisture and transform to the monohydrate, and it is more expensive to produce.

Anhydrous dextrose (anhydrous D-glucose) has increased stability and increased shelf life,

has medical applications, such as in oral

glucose tolerance test

The glucose tolerance test (GTT, not to be confused with GGT test) is a medical test in which glucose is given and blood samples taken afterward to determine how quickly it is cleared from the blood. The test is usually used to test for diabetes, ...

.

Whereas molecular weight (molar mass) for D-glucose monohydrate is 198.17 g/mol, that for anhydrous D-glucose is 180.16 g/mol The density of these two forms of glucose is also different.

In terms of chemical structure, glucose is a monosaccharide, that is, a simple sugar. Glucose contains six carbon atoms and an

aldehyde group

In organic chemistry, an aldehyde () (lat. ''al''cohol ''dehyd''rogenatum, dehydrogenated alcohol) is an organic compound containing a functional group with the structure . The functional group itself (without the "R" side chain) can be referred ...

, and is therefore an

aldohexose

In chemistry, a hexose is a monosaccharide (simple sugar) with six carbon atoms. The chemical formula for all hexoses is , and their molecular weight is 180.156 g/mol.

Hexoses exist in two forms, open-chain or cyclic, that easily convert into e ...

. The glucose molecule can exist in an

open-chain

In chemistry, an open-chain compound (or open chain compound) or acyclic compound (Greek prefix ''α'' 'without' and ''κύκλος'' 'cycle') is a compound with a linear structure, rather than a cyclic one.

An open-chain compound having no side ...

(acyclic) as well as ring (cyclic) form—due to the presence of

alcohol

Alcohol may refer to:

Common uses

* Alcohol (chemistry), a class of compounds

* Ethanol, one of several alcohols, commonly known as alcohol in everyday life

** Alcohol (drug), intoxicant found in alcoholic beverages

** Alcoholic beverage, an alco ...

and

aldehyde

In organic chemistry, an aldehyde () (lat. ''al''cohol ''dehyd''rogenatum, dehydrogenated alcohol) is an organic compound containing a functional group with the structure . The functional group itself (without the "R" side chain) can be referred ...

or

ketone

In organic chemistry, a ketone is an organic compound with the structure , where R and R' can be a variety of carbon-containing substituents. Ketones contain a carbonyl group (a carbon-oxygen double bond C=O). The simplest ketone is acetone ( ...

functional groups, the form having the straight chain can easily convert into a chair-like

hemiacetal

In organic chemistry, a hemiacetal is a functional group the general formula , where is a hydrogen atom or an organic substituent. They generally result from the nucleophilic Addition reaction, addition of an Alcohol (chemistry), alcohol (a compo ...

ring structure commonly found in carbohydrates.

Structure and nomenclature

Glucose is present in solid form as a

monohydrate

In chemistry, a hydrate is a substance that contains water or its constituent elements. The chemical state of the water varies widely between different classes of hydrates, some of which were so labeled before their chemical structure was understo ...

with a closed

pyran

In chemistry, pyran is a six-membered heterocyclic, non-aromatic ring, consisting of five carbon atoms and one oxygen atom and containing two double bonds. The molecular formula is C5H6O. There are two isomers of pyran that differ by the location ...

ring (α-D-glucopyranose monohydrate, sometimes known less precisely by dextrose hydrate). In aqueous solution, on the other hand, a small proportion of glucose can be found in an open-chain configuration while remaining predominantly as α- or β-

pyranose

In organic chemistry, pyranose is a collective term for saccharides that have a chemical structure that includes a six-membered ring consisting of five carbon atoms and one oxygen atom (a heterocycle). There may be other carbons external to the ...

, which interconvert. From aqueous solutions, the three known forms can be crystallized: α-glucopyranose, β-glucopyranose and α-glucopyranose monohydrate.

Glucose is a building block of the disaccharides lactose and sucrose (cane or beet sugar), of

oligosaccharide

An oligosaccharide (; ) is a carbohydrate, saccharide polymer containing a small number (typically three to ten) of monosaccharides (simple sugars). Oligosaccharides can have many functions including Cell–cell recognition, cell recognition and ce ...

s such as

raffinose

Raffinose is a trisaccharide composed of galactose, glucose, and fructose. It can be found in beans, cabbage, brussels sprouts, broccoli, asparagus, other vegetables, and whole grains. Raffinose can be hydrolyzed to D-galactose and sucrose by th ...

and of

polysaccharide

Polysaccharides (), or polycarbohydrates, are the most abundant carbohydrates found in food. They are long-chain polymeric carbohydrates composed of monosaccharide units bound together by glycosidic linkages. This carbohydrate can react with wat ...

s such as

starch

Starch or amylum is a polymeric carbohydrate consisting of numerous glucose units joined by glycosidic bonds. This polysaccharide is produced by most green plants for energy storage. Worldwide, it is the most common carbohydrate in human diet ...

,

amylopectin Amylopectin is a water-insoluble polysaccharide and highly branched polymer of α-glucose units found in plants. It is one of the two components of starch, the other being amylose.

Plants store starch within specialized organelles called amyloplas ...

,

glycogen

Glycogen is a multibranched polysaccharide of glucose that serves as a form of energy storage in animals, fungi, and bacteria. It is the main storage form of glucose in the human body.

Glycogen functions as one of three regularly used forms ...

, and

cellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the chemical formula, formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to many thousands of glycosidic bond, β(1→4) linked glucose, D-glucose units. Cellulose is an important s ...

.

The

glass transition temperature

The glass–liquid transition, or glass transition, is the gradual and reversible transition in amorphous materials (or in amorphous regions within semicrystalline materials) from a hard and relatively brittle "glassy" state into a viscous or rub ...

of glucose is and the Gordon–Taylor constant (an experimentally determined constant for the prediction of the glass transition temperature for different mass fractions of a mixture of two substances)

[Patrick F. Fox: ''Advanced Dairy Chemistry Volume 3: Lactose, water, salts and vitamins'', Springer, 1992. Volume 3, . p. 316.] is 4.5.

[Benjamin Caballero, Paul Finglas, Fidel Toldrá: ''Encyclopedia of Food and Health''. Academic Press (2016). , Volume 1, p. 76.]

Open-chain form

A open-chain form of glucose makes up less than 0.02% of the glucose molecules in an aqueous solution at equilibrium. The rest is one of two cyclic hemiacetal forms. In its

open-chain

In chemistry, an open-chain compound (or open chain compound) or acyclic compound (Greek prefix ''α'' 'without' and ''κύκλος'' 'cycle') is a compound with a linear structure, rather than a cyclic one.

An open-chain compound having no side ...

form, the glucose molecule has an open (as opposed to

cyclic

Cycle, cycles, or cyclic may refer to:

Anthropology and social sciences

* Cyclic history, a theory of history

* Cyclical theory, a theory of American political history associated with Arthur Schlesinger, Sr.

* Social cycle, various cycles in s ...

) unbranched backbone of six carbon atoms, where C-1 is part of an

aldehyde group

In organic chemistry, an aldehyde () (lat. ''al''cohol ''dehyd''rogenatum, dehydrogenated alcohol) is an organic compound containing a functional group with the structure . The functional group itself (without the "R" side chain) can be referred ...

. Therefore, glucose is also classified as an

aldose

An aldose is a monosaccharide (a simple sugar) with a carbon backbone chain with a carbonyl group on the endmost carbon atom, making it an aldehyde, and hydroxyl groups connected to all the other carbon atoms. Aldoses can be distinguished from ket ...

, or an

aldohexose

In chemistry, a hexose is a monosaccharide (simple sugar) with six carbon atoms. The chemical formula for all hexoses is , and their molecular weight is 180.156 g/mol.

Hexoses exist in two forms, open-chain or cyclic, that easily convert into e ...

. The aldehyde group makes glucose a

reducing sugar

A reducing sugar is any sugar that is capable of acting as a reducing agent. In an alkaline solution, a reducing sugar forms some aldehyde or ketone, which allows it to act as a reducing agent, for example in Benedict's reagent. In such a react ...

giving a positive reaction with the

Fehling test

In organic chemistry, Fehling's solution is a chemical reagent used to differentiate between water-soluble carbohydrate and ketone () functional groups, and as a test for reducing sugars and non-reducing sugars, supplementary to the Tollens' rea ...

.

Cyclic forms

In solutions, the open-chain form of glucose (either "-" or "-") exists in equilibrium with several

cyclic isomers, each containing a ring of carbons closed by one oxygen atom. In aqueous solution, however, more than 99% of glucose molecules exist as

pyranose

In organic chemistry, pyranose is a collective term for saccharides that have a chemical structure that includes a six-membered ring consisting of five carbon atoms and one oxygen atom (a heterocycle). There may be other carbons external to the ...

forms. The open-chain form is limited to about 0.25%, and

furanose

A furanose is a collective term for carbohydrates that have a chemical structure that includes a five-membered ring system consisting of four carbon atoms and one oxygen atom. The name derives from its similarity to the oxygen heterocycle furan, ...

forms exist in negligible amounts. The terms "glucose" and "-glucose" are generally used for these cyclic forms as well. The ring arises from the open-chain form by an intramolecular

nucleophilic addition

In organic chemistry, a nucleophilic addition (AN) reaction is an addition reaction where a chemical compound with an electrophilic double or triple bond reacts with a nucleophile, such that the double or triple bond is broken. Nucleophilic addit ...

reaction between the aldehyde group (at C-1) and either the C-4 or C-5 hydroxyl group, forming a

hemiacetal

In organic chemistry, a hemiacetal is a functional group the general formula , where is a hydrogen atom or an organic substituent. They generally result from the nucleophilic Addition reaction, addition of an Alcohol (chemistry), alcohol (a compo ...

linkage, .

The reaction between C-1 and C-5 yields a six-membered

heterocyclic

A heterocyclic compound or ring structure is a cyclic compound that has atoms of at least two different elements as members of its ring(s). Heterocyclic organic chemistry is the branch of organic chemistry dealing with the synthesis, proper ...

system called a pyranose, which is a monosaccharide sugar (hence "-ose") containing a derivatised

pyran

In chemistry, pyran is a six-membered heterocyclic, non-aromatic ring, consisting of five carbon atoms and one oxygen atom and containing two double bonds. The molecular formula is C5H6O. There are two isomers of pyran that differ by the location ...

skeleton. The (much rarer) reaction between C-1 and C-4 yields a five-membered furanose ring, named after the cyclic ether

furan

Furan is a Heterocyclic compound, heterocyclic organic compound, consisting of a five-membered aromatic Ring (chemistry), ring with four carbon Atom, atoms and one oxygen atom. Chemical compounds containing such rings are also referred to as f ...

. In either case, each carbon in the ring has one hydrogen and one hydroxyl attached, except for the last carbon (C-4 or C-5) where the hydroxyl is replaced by the remainder of the open molecule (which is or respectively).

The ring-closing reaction can give two products, denoted "α-" and "β-". When a glucopyranose molecule is drawn in the

Haworth projection

In chemistry, a Haworth projection is a common way of writing a structural formula to represent the cyclic structure of monosaccharides with a simple three-dimensional perspective. A Haworth projection approximates the shapes of the actual mole ...

, the designation "α-" means that the hydroxyl group attached to C-1 and the group at C-5 lies on opposite sides of the ring's plane (a

'' trans'' arrangement), while "β-" means that they are on the same side of the plane (a

'' cis'' arrangement). Therefore, the open-chain isomer -glucose gives rise to four distinct cyclic isomers: α--glucopyranose, β--glucopyranose, α--glucofuranose, and β--glucofuranose. These five structures exist in equilibrium and interconvert, and the interconversion is much more rapid with acid

catalysis

Catalysis () is the increase in rate of a chemical reaction due to an added substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed by the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recycles quick ...

.

The other open-chain isomer -glucose similarly gives rise to four distinct cyclic forms of -glucose, each the mirror image of the corresponding -glucose.

The glucopyranose ring (α or β) can assume several non-planar shapes, analogous to the "chair" and "boat" conformations of

cyclohexane

Cyclohexane is a cycloalkane with the molecular formula . Cyclohexane is non-polar. Cyclohexane is a colourless, flammable liquid with a distinctive detergent-like odor, reminiscent of cleaning products (in which it is sometimes used). Cyclohexan ...

. Similarly, the glucofuranose ring may assume several shapes, analogous to the "envelope" conformations of

cyclopentane

Cyclopentane (also called C pentane) is a highly flammable alicyclic compound, alicyclic hydrocarbon with chemical formula C5H10, C5H10 and CAS number 287-92-3, consisting of a ring of five carbon atoms each bonded with two hydrogen atoms above and ...

.

In the solid state, only the glucopyranose forms are observed.

Some derivatives of glucofuranose, such as

1,2-''O''-isopropylidene--glucofuranose are stable and can be obtained pure as crystalline solids.

For example, reaction of α-D-glucose with

''para''-tolylboronic acid reforms the normal pyranose ring to yield the 4-fold ester α-D-glucofuranose-1,2:3,5-bis(''p''-tolylboronate).

Mutarotation

Mutarotation consists of a temporary reversal of the ring-forming reaction, resulting in the open-chain form, followed by a reforming of the ring. The ring closure step may use a different group than the one recreated by the opening step (thus switching between pyranose and furanose forms), or the new hemiacetal group created on C-1 may have the same or opposite handedness as the original one (thus switching between the α and β forms). Thus, though the open-chain form is barely detectable in solution, it is an essential component of the equilibrium.

The open-chain form is

thermodynamically unstable, and it spontaneously

isomer

In chemistry, isomers are molecules or polyatomic ions with identical molecular formula – that is, the same number of atoms of each element (chemistry), element – but distinct arrangements of atoms in space. ''Isomerism'' refers to the exi ...

izes to the cyclic forms. (Although the ring closure reaction could in theory create four- or three-atom rings, these would be highly strained, and are not observed in practice.) In solutions at

room temperature

Room temperature, colloquially, denotes the range of air temperatures most people find comfortable indoors while dressed in typical clothing. Comfortable temperatures can be extended beyond this range depending on humidity, air circulation, and ...

, the four cyclic isomers interconvert over a time scale of hours, in a process called

mutarotation

In stereochemistry, mutarotation is the change in optical rotation of a chiral material in a solution due to a change in proportion of the two constituent anomers (i.e. the interconversion of their respective stereocenters) until equilibrium is re ...

. Starting from any proportions, the mixture converges to a stable ratio of α:β 36:64. The ratio would be α:β 11:89 if it were not for the influence of the

anomeric effect

In organic chemistry, the anomeric effect or Edward-Lemieux effect (after J. T. Edward and Raymond Lemieux) is a stereoelectronic effect that describes the tendency of heteroatomic substituents adjacent to the heteroatom in the ring in, e.g., t ...

. Mutarotation is considerably slower at temperatures close to .

Optical activity

Whether in water or the solid form, -(+)-glucose is

dextrorotatory

Optical rotation, also known as polarization rotation or circular birefringence, is the rotation of the orientation of the plane of polarization about the optical axis of linearly polarized light as it travels through certain materials. Circul ...

, meaning it will rotate the direction of

polarized light

, or , is a property of transverse waves which specifies the geometrical orientation of the oscillations. In a transverse wave, the direction of the oscillation is perpendicular to the direction of motion of the wave. One example of a polarize ...

clockwise as seen looking toward the light source. The effect is due to the

chirality

Chirality () is a property of asymmetry important in several branches of science. The word ''chirality'' is derived from the Greek (''kheir''), "hand", a familiar chiral object.

An object or a system is ''chiral'' if it is distinguishable fro ...

of the molecules, and indeed the mirror-image isomer, -(−)-glucose, is

levorotatory

Optical rotation, also known as polarization rotation or circular birefringence, is the rotation of the orientation of the plane of polarization about the optical axis of linearly polarized light as it travels through certain materials. Circul ...

(rotates polarized light counterclockwise) by the same amount. The strength of the effect is different for each of the five

tautomer

In chemistry, tautomers () are structural isomers (constitutional isomers) of chemical compounds that readily interconvert.

The chemical reaction interconverting the two is called tautomerization. This conversion commonly results from the reloca ...

s.

The - prefix does not refer directly to the optical properties of the compound. It indicates that the C-5 chiral centre has the same handedness as that of

-glyceraldehyde (which was so labelled because it is dextrorotatory). The fact that -glucose is dextrorotatory is a combined effect of its four chiral centres, not just of C-5; some of the other -aldohexoses are levorotatory.

The conversion between the two anomers can be observed in a

polarimeter

A polarimeter is a scientific instrument used to measure optical rotation: the angle of rotation caused by passing linearly polarized light through an Optical activity, optically active substance.

Some chemical substances are optically active, ...

since pure α--glucose has a specific rotation angle of +112.2° mL/(dm·g), pure β--glucose of +17.5° mL/(dm·g).

[Manfred Hesse, Herbert Meier, Bernd Zeeh, Stefan Bienz, Laurent Bigler, Thomas Fox: ''Spektroskopische Methoden in der organischen Chemie''. 8th revised Edition. Georg Thieme, 2011, , p. 34 (in German).] When equilibrium has been reached after a certain time due to mutarotation, the angle of rotation is +52.7° mL/(dm·g).

By adding acid or base, this transformation is much accelerated. The equilibration takes place via the open-chain aldehyde form.

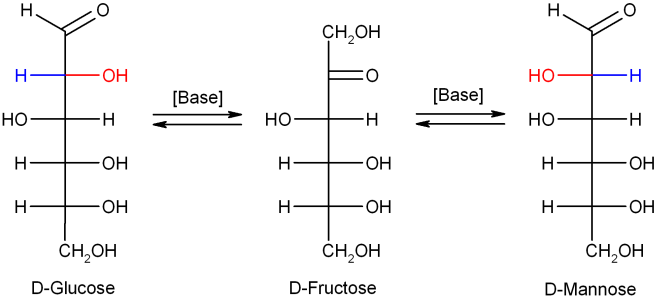

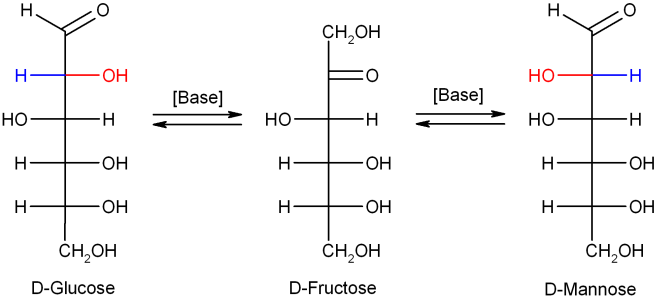

Isomerisation

In dilute

sodium hydroxide

Sodium hydroxide, also known as lye and caustic soda, is an inorganic compound with the formula . It is a white solid ionic compound consisting of sodium cations and hydroxide anions .

Sodium hydroxide is a highly corrosive base (chemistry), ...

or other dilute bases, the monosaccharides

mannose

Mannose is a sugar with the formula , which sometimes is abbreviated Man. It is one of the monomers of the aldohexose series of carbohydrates. It is a C-2 epimer of glucose. Mannose is important in human metabolism, especially in the glycosylatio ...

, glucose and

fructose

Fructose (), or fruit sugar, is a Ketose, ketonic monosaccharide, simple sugar found in many plants, where it is often bonded to glucose to form the disaccharide sucrose. It is one of the three dietary monosaccharides, along with glucose and gal ...

interconvert (via a

Lobry de Bruyn–Alberda–Van Ekenstein transformation), so that a balance between these isomers is formed. This reaction proceeds via an

enediol

In organic chemistry, enols are a type of functional group or intermediate in organic chemistry containing a group with the formula (R = many substituents). The term ''enol'' is an abbreviation of ''alkenol'', a portmanteau deriving from "-ene ...

:

Biochemical properties

Glucose is the most abundant monosaccharide. Glucose is also the most widely used aldohexose in most living organisms. One possible explanation for this is that glucose has a lower tendency than other aldohexoses to react nonspecifically with the

amine

In chemistry, amines (, ) are organic compounds that contain carbon-nitrogen bonds. Amines are formed when one or more hydrogen atoms in ammonia are replaced by alkyl or aryl groups. The nitrogen atom in an amine possesses a lone pair of elec ...

groups of

protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

s.

This reaction—

glycation

Glycation (non-enzymatic glycosylation) is the covalent bond, covalent attachment of a sugar to a protein, lipid or nucleic acid molecule. Typical sugars that participate in glycation are glucose, fructose, and their derivatives. Glycation is th ...

—impairs or destroys the function of many proteins,

[ e.g. in ]glycated hemoglobin

Glycated hemoglobin, also called glycohemoglobin, is a form of hemoglobin (Hb) that is chemically linked to a sugar. Most monosaccharides, including glucose, galactose, and fructose, spontaneously (that is, non-enzymatically) bond with hemoglob ...

. Glucose's low rate of glycation can be attributed to its having a more stable cyclic form

Cyclic form is a technique of musical construction, involving multiple sections or movements, in which a theme, melody, or thematic material occurs in more than one movement as a unifying device. Sometimes a theme may occur at the beginning and ...

compared to other aldohexoses, which means it spends less time than they do in its reactive open-chain form.[ The reason for glucose having the most stable cyclic form of all the aldohexoses is that its ]hydroxy group

In chemistry, a hydroxy or hydroxyl group is a functional group with the chemical formula and composed of one oxygen atom covalently bonded to one hydrogen atom. In organic chemistry, alcohols and carboxylic acids contain one or more hydroxy ...

s (with the exception of the hydroxy group on the anomeric carbon of -glucose) are in the equatorial position. Presumably, glucose is the most abundant natural monosaccharide because it is less glycated with proteins than other monosaccharides.[Jeremy M. Berg: ''Stryer Biochemie'' . Springer-Verlag, 2017, , p. 531.] Another hypothesis is that glucose, being the only -aldohexose that has all five hydroxy substituents in the equatorial position in the form of β--glucose, is more readily accessible to chemical reactions,esterification

In chemistry, an ester is a compound derived from an acid (either organic or inorganic) in which the hydrogen atom (H) of at least one acidic hydroxyl group () of that acid is replaced by an organyl group (R). These compounds contain a distin ...

acetal

In organic chemistry, an acetal is a functional group with the connectivity . Here, the R groups can be organic fragments (a carbon atom, with arbitrary other atoms attached to that) or hydrogen, while the R' groups must be organic fragments n ...

formation. For this reason, -glucose is also a highly preferred building block in natural polysaccharides (glycans). Polysaccharides that are composed solely of glucose are termed glucan

A glucan is a polysaccharide derived from D-glucose, linked by glycosidic bonds. Glucans are noted in two forms: alpha glucans and beta glucans. Many beta-glucans are medically important. They represent a drug target for antifungal medications of ...

s.

Glucose is produced by plants through photosynthesis using sunlight,chitin

Chitin (carbon, C8hydrogen, H13oxygen, O5nitrogen, N)n ( ) is a long-chain polymer of N-Acetylglucosamine, ''N''-acetylglucosamine, an amide derivative of glucose. Chitin is the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (behind only cell ...

, which are components of the cell wall in plants or fungi

A fungus (: fungi , , , or ; or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and mold (fungus), molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as one ...

and arthropod

Arthropods ( ) are invertebrates in the phylum Arthropoda. They possess an arthropod exoskeleton, exoskeleton with a cuticle made of chitin, often Mineralization (biology), mineralised with calcium carbonate, a body with differentiated (Metam ...

s, respectively. These polymers, when consumed by animals, fungi and bacteria, are degraded to glucose using enzymes. All animals are also able to produce glucose themselves from certain precursors as the need arises. Neuron

A neuron (American English), neurone (British English), or nerve cell, is an membrane potential#Cell excitability, excitable cell (biology), cell that fires electric signals called action potentials across a neural network (biology), neural net ...

s, cells of the renal medulla

The renal medulla (Latin: ''medulla renis'' 'marrow of the kidney') is the innermost part of the kidney. The renal medulla is split up into a number of sections, known as the renal pyramids. Blood enters into the kidney via the renal artery, which ...

and erythrocytes

Red blood cells (RBCs), referred to as erythrocytes (, with -''cyte'' translated as 'cell' in modern usage) in academia and medical publishing, also known as red cells, erythroid cells, and rarely haematids, are the most common type of blood cel ...

depend on glucose for their energy production.[Peter C. Heinrich: ''Löffler/Petrides Biochemie und Pathobiochemie'' .. Springer-Verlag, 2014, , p. 195.] In adult humans, there is about of glucose,[U. Satyanarayana: ''Biochemistry''. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2014, . p. 674.] of which about is present in the blood. Approximately of glucose is produced in the liver of an adult in 24 hours.diabetes

Diabetes mellitus, commonly known as diabetes, is a group of common endocrine diseases characterized by sustained high blood sugar levels. Diabetes is due to either the pancreas not producing enough of the hormone insulin, or the cells of th ...

(e.g., Visual impairment, blindness, kidney failure, and peripheral neuropathy) are probably due to the glycation of proteins or lipids. In contrast, enzyme-regulated addition of sugars to protein is called glycosylation and is essential for the function of many proteins.

Uptake

Ingested glucose initially binds to the receptor for sweet taste on the tongue in humans. This complex of the proteins T1R2 and T1R3 makes it possible to identify glucose-containing food sources.[Peter C. Heinrich: ''Löffler/Petrides Biochemie und Pathobiochemie''. Springer-Verlag, 2014, , p. 404.] but it is also synthesized from other metabolites in the body's cells. In humans, the breakdown of glucose-containing polysaccharides happens in part already during chewing by means of amylase, which is contained in saliva, as well as by maltase, lactase, and sucrase on the brush border of the small intestine. Glucose is a building block of many carbohydrates and can be split off from them using certain enzymes. Glucosidases, a subgroup of the glycosidases, first catalyze the hydrolysis of long-chain glucose-containing polysaccharides, removing terminal glucose. In turn, disaccharides are mostly degraded by specific glycosidases to glucose. The names of the degrading enzymes are often derived from the particular poly- and disaccharide; inter alia, for the degradation of polysaccharide chains there are amylases (named after amylose, a component of starch), cellulases (named after cellulose), chitinases (named after chitin), and more. Furthermore, for the cleavage of disaccharides, there are maltase, lactase, sucrase, trehalase, and others. In humans, about 70 genes are known that code for glycosidases. They have functions in the digestion and degradation of glycogen, sphingolipids, mucopolysaccharides, and poly(Adenosine diphosphate ribose, ADP-ribose). Humans do not produce cellulases, chitinases, or trehalases, but the bacteria in the gut microbiota do.

In order to get into or out of cell membranes of cells and membranes of cell compartments, glucose requires special transport proteins from the major facilitator superfamily. In the small intestine (more precisely, in the jejunum),[Harold A. Harper: ''Medizinische Biochemie'' . Springer-Verlag, 2013, , p. 641.] glucose is taken up into the intestinal epithelium with the help of glucose transporters via a secondary active transport mechanism called sodium ion-glucose symport via sodium/glucose cotransporter 1 (SGLT1).

Biosynthesis

In plants and some prokaryotes, glucose is a product of photosynthesis

Photosynthesis ( ) is a system of biological processes by which photosynthetic organisms, such as most plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, convert light energy, typically from sunlight, into the chemical energy necessary to fuel their metabo ...

.glycogen

Glycogen is a multibranched polysaccharide of glucose that serves as a form of energy storage in animals, fungi, and bacteria. It is the main storage form of glucose in the human body.

Glycogen functions as one of three regularly used forms ...

(in animals and mushrooms) or starch (in plants). The cleavage of glycogen is termed glycogenolysis, the cleavage of starch is called starch degradation.

The metabolic pathway that begins with molecules containing two to four carbon atoms (C) and ends in the glucose molecule containing six carbon atoms is called gluconeogenesis and occurs in all living organisms. The smaller starting materials are the result of other metabolic pathways. Ultimately almost all biomolecules come from the assimilation of carbon dioxide in plants and microbes during photosynthesis.[ The free energy of formation of α--glucose is 917.2 kilojoules per mole.][ In humans, gluconeogenesis occurs in the liver and kidney,][Leszek Szablewski: ''Glucose Homeostasis and Insulin Resistance''. Bentham Science Publishers, 2011, , p. 46.] but also in other cell types. In the liver about of glycogen are stored, in skeletal muscle about .[Peter C. Heinrich: ''Löffler/Petrides Biochemie und Pathobiochemie'' . Springer-Verlag, 2014, , p. 389.] However, the glucose released in muscle cells upon cleavage of the glycogen can not be delivered to the circulation because glucose is phosphorylated by the hexokinase, and a glucose-6-phosphatase is not expressed to remove the phosphate group. Unlike for glucose, there is no transport protein for Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (coenzyme-F420), glucose-6-phosphate. Gluconeogenesis allows the organism to build up glucose from other metabolites, including lactic acid, lactate or certain amino acids, while consuming energy. The renal tubular cells can also produce glucose.

Glucose also can be found outside of living organisms in the ambient environment. Glucose concentrations in the atmosphere are detected via collection of samples by aircraft and are known to vary from location to location. For example, glucose concentrations in atmospheric air from inland China range from 0.8 to 20.1 pg/L, whereas east coastal China glucose concentrations range from 10.3 to 142 pg/L.

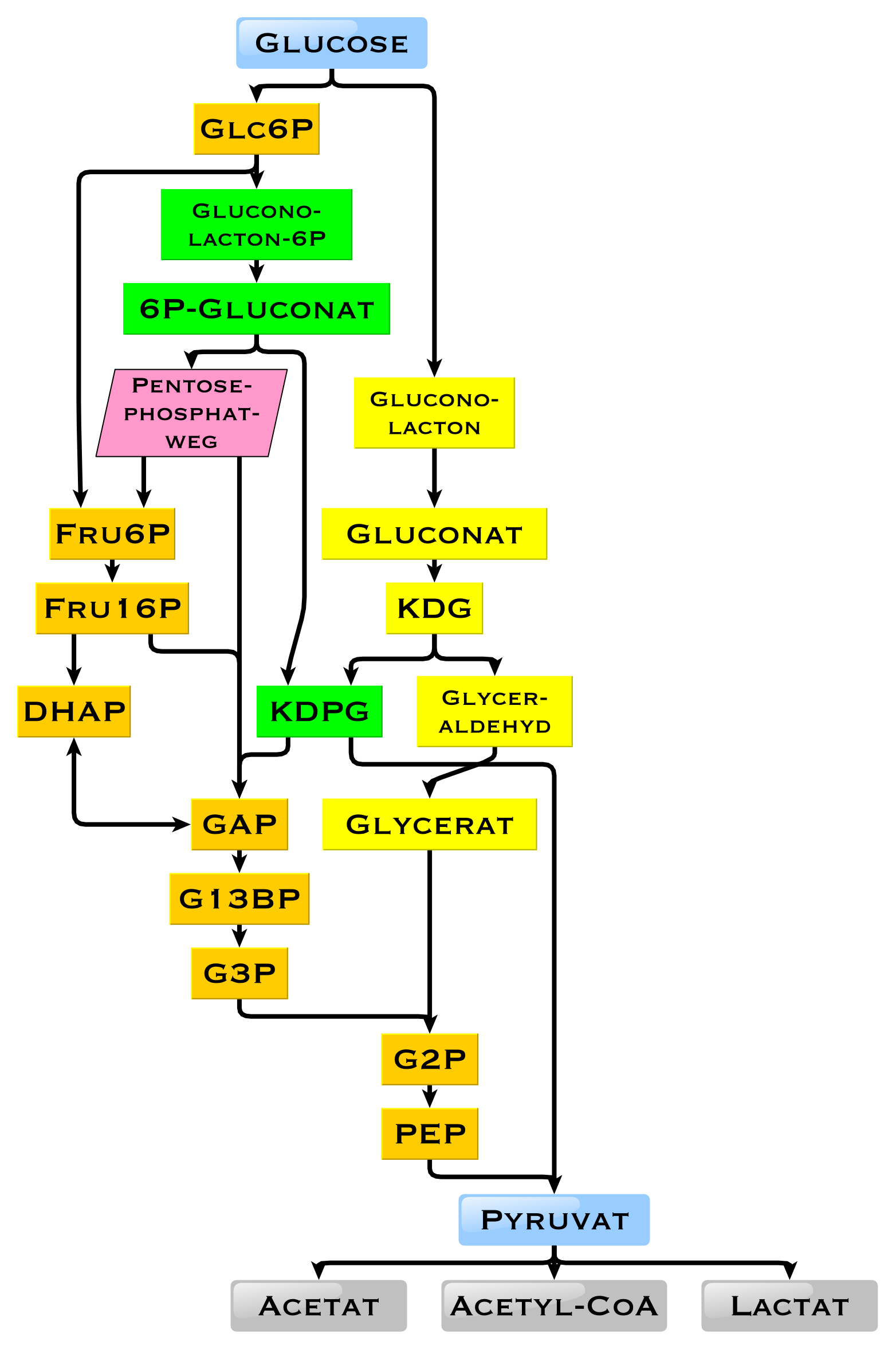

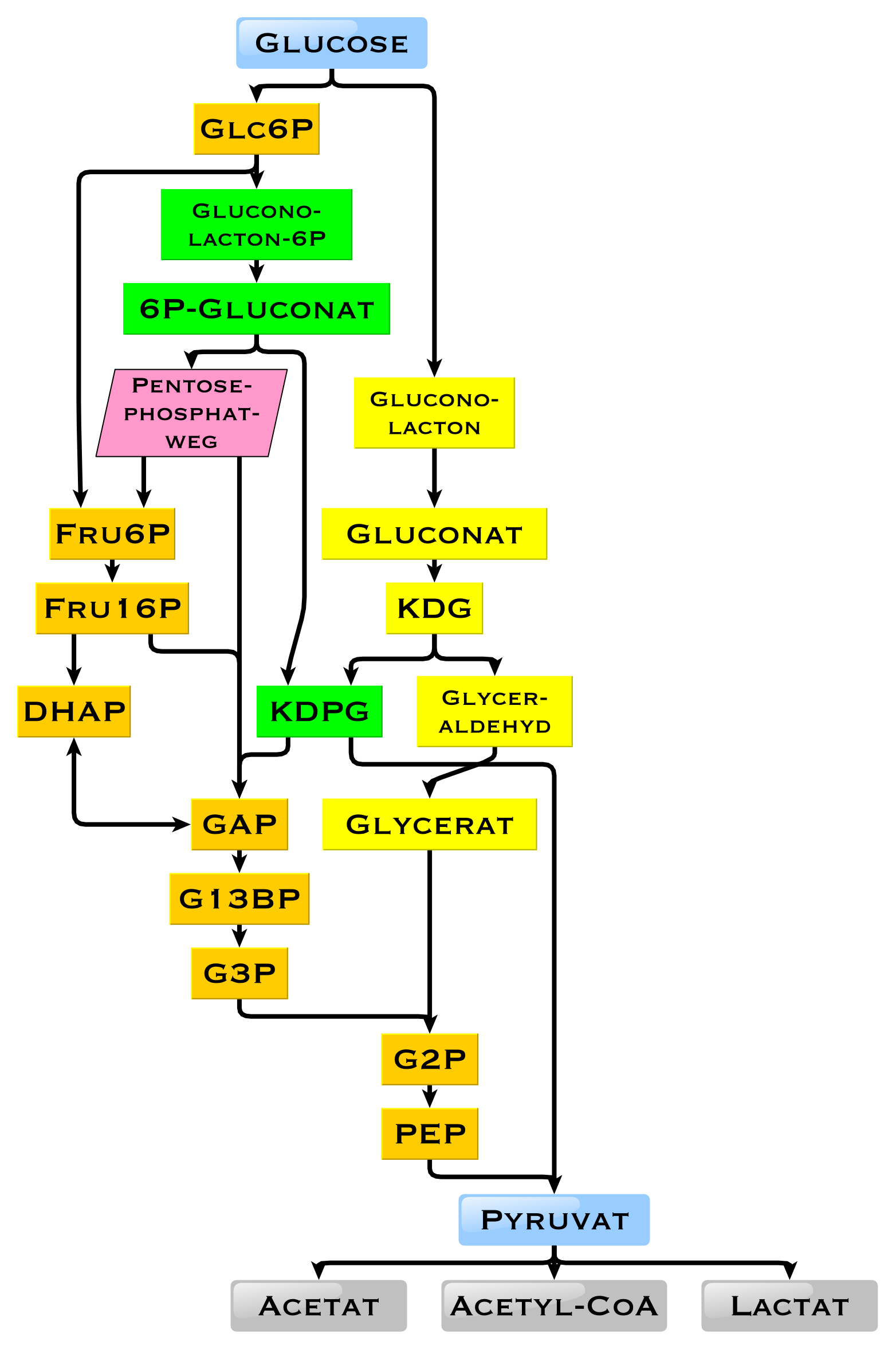

Glucose degradation

In humans, glucose is metabolized by glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway.

In humans, glucose is metabolized by glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway.[H. Robert Horton, Laurence A. Moran, K. Gray Scrimgeour, Marc D. Perry, J. David Rawn: ''Biochemie'' . Pearson Studium; 4. aktualisierte Auflage 2008; ; pp. 490–496.] Glycolysis is used by all living organisms,[Brian K. Hall: ''Strickberger's Evolution''. Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2013, , p. 164.] with small variations, and all organisms generate energy from the breakdown of monosaccharides.[ In some bacteria and, in modified form, also in archaea, glucose is degraded via the Entner-Doudoroff pathway. With glucose, a mechanism for gene regulation was discovered in ''E. coli'', the catabolite repression (formerly known as ''glucose effect'').]

Energy source

Glucose is a ubiquitous fuel in biology. It is used as an energy source in organisms, from bacteria to humans, through either aerobic respiration, anaerobic respiration (in bacteria), or Fermentation (biochemistry), fermentation. Glucose is the human body's key source of energy, through aerobic respiration, providing about 3.75 kilocalories (16 kilojoules) of food energy per gram. Breakdown of carbohydrates (e.g., starch) yields mono- and disaccharides, most of which is glucose. Through glycolysis and later in the reactions of the citric acid cycle and oxidative phosphorylation, glucose is oxidized to eventually form carbon dioxide and water, yielding energy mostly in the form of

Glucose is a ubiquitous fuel in biology. It is used as an energy source in organisms, from bacteria to humans, through either aerobic respiration, anaerobic respiration (in bacteria), or Fermentation (biochemistry), fermentation. Glucose is the human body's key source of energy, through aerobic respiration, providing about 3.75 kilocalories (16 kilojoules) of food energy per gram. Breakdown of carbohydrates (e.g., starch) yields mono- and disaccharides, most of which is glucose. Through glycolysis and later in the reactions of the citric acid cycle and oxidative phosphorylation, glucose is oxidized to eventually form carbon dioxide and water, yielding energy mostly in the form of adenosine triphosphate

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is a nucleoside triphosphate that provides energy to drive and support many processes in living cell (biology), cells, such as muscle contraction, nerve impulse propagation, and chemical synthesis. Found in all known ...

(ATP). The insulin reaction, and other mechanisms, regulate the concentration of glucose in the blood. The physiological caloric value of glucose, depending on the source, is 16.2 kilojoules per gram[Georg Schwedt: ''Zuckersüße Chemie'' . John Wiley & Sons, 2012, , p. 100.] or 15.7 kJ/g (3.74 kcal/g). The high availability of carbohydrates from plant biomass has led to a variety of methods during evolution, especially in microorganisms, to utilize glucose for energy and carbon storage. Differences exist in which end product can no longer be used for energy production. The presence of individual genes, and their gene products, the enzymes, determine which reactions are possible. The metabolic pathway of glycolysis is used by almost all living beings. An essential difference in the use of glycolysis is the recovery of NADPH as a reductant for anabolism that would otherwise have to be generated indirectly.

Glucose and oxygen supply almost all the energy for the brain, so its availability influences psychological processes. When Hypoglycaemia, glucose is low, psychological processes requiring mental effort (e.g., self-control, effortful decision-making) are impaired. In the brain, which is dependent on glucose and oxygen as the major source of energy, the glucose concentration is usually 4 to 6 mM (5 mM equals 90 mg/dL),blood sugar

The blood sugar level, blood sugar concentration, blood glucose level, or glycemia is the measure of glucose concentrated in the blood. The body tightly regulates blood glucose levels as a part of metabolic homeostasis.

For a 70 kg (1 ...

. Blood sugar levels are regulated by glucose-binding nerve cells in the hypothalamus.[Harold A. Harper: ''Medizinische Biochemie''. Springer-Verlag, 2013, , p. 294.]

Some glucose is converted to lactic acid by astrocytes, which is then utilized as an energy source by brain cells; some glucose is used by intestinal cells and red blood cells, while the rest reaches the liver, adipose tissue and muscle cells, where it is absorbed and stored as glycogen (under the influence of insulin). Liver cell glycogen can be converted to glucose and returned to the blood when insulin is low or absent; muscle cell glycogen is not returned to the blood because of a lack of enzymes. In Adipocyte, fat cells, glucose is used to power reactions that synthesize some fat types and have other purposes. Glycogen is the body's "glucose energy storage" mechanism, because it is much more "space efficient" and less reactive than glucose itself.

As a result of its importance in human health, glucose is an analyte in glucose tests that are common medical blood tests. Eating or fasting prior to taking a blood sample has an effect on analyses for glucose in the blood; a high fasting glucose blood sugar level may be a sign of prediabetes or diabetes mellitus.

The glycemic index is an indicator of the speed of resorption and conversion to blood glucose levels from ingested carbohydrates, measured as the area under a curve, area under the curve of blood glucose levels after consumption in comparison to glucose (glucose is defined as 100).[Richard A. Harvey, Denise R. Ferrier: ''Biochemistry''. 5th Edition, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011, , p. 366.] The clinical importance of the glycemic index is controversial,[U Satyanarayana: ''Biochemistry''. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2014, , p. 508.] as foods with high fat contents slow the resorption of carbohydrates and lower the glycemic index, e.g. ice cream.

Precursor

Organisms use glucose as a precursor for the synthesis of several important substances. Starch, cellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the chemical formula, formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to many thousands of glycosidic bond, β(1→4) linked glucose, D-glucose units. Cellulose is an important s ...

, and glycogen ("animal starch") are common glucose polymer

A polymer () is a chemical substance, substance or material that consists of very large molecules, or macromolecules, that are constituted by many repeat unit, repeating subunits derived from one or more species of monomers. Due to their br ...

s (polysaccharides). Some of these polymers (starch or glycogen) serve as energy stores, while others (cellulose and chitin

Chitin (carbon, C8hydrogen, H13oxygen, O5nitrogen, N)n ( ) is a long-chain polymer of N-Acetylglucosamine, ''N''-acetylglucosamine, an amide derivative of glucose. Chitin is the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (behind only cell ...

, which is made from a derivative of glucose) have structural roles. Oligosaccharides of glucose combined with other sugars serve as important energy stores. These include lactose, the predominant sugar in milk, which is a glucose-galactose disaccharide, and sucrose, another disaccharide which is composed of glucose and fructose. Glucose is also added onto certain proteins and lipids in a process called glycosylation. This is often critical for their functioning. The enzymes that join glucose to other molecules usually use phosphorylation, phosphorylated glucose to power the formation of the new bond by coupling it with the breaking of the glucose-phosphate bond.

Other than its direct use as a monomer, glucose can be broken down to synthesize a wide variety of other biomolecules. This is important, as glucose serves both as a primary store of energy and as a source of organic carbon. Glucose can be broken down and converted into lipids. It is also a precursor for the synthesis of other important molecules such as vitamin C (ascorbic acid). In living organisms, glucose is converted to several other chemical compounds that are the starting material for various metabolic pathways. Among them, all other monosaccharides[Peter C. Heinrich: ''Löffler/Petrides Biochemie und Pathobiochemie'' . Springer-Verlag, 2014, , p. 27.] such as fructose (via the polyol pathway),[Peter C. Heinrich: ''Löffler/Petrides Biochemie und Pathobiochemie'' . Springer-Verlag, 2014, , p. 199, 200.] mannose (the epimer of glucose at position 2), galactose (the epimer at position 4), fucose, various uronic acids and the amino sugars are produced from glucose.[Peter C. Heinrich: ''Löffler/Petrides Biochemie und Pathobiochemie'' . Springer-Verlag, 2014, , p. 214.] In addition to the phosphorylation to glucose-6-phosphate, which is part of the glycolysis, glucose can be oxidized during its degradation to glucono-1,5-lactone. Glucose is used in some bacteria as a building block in the trehalose or the dextran biosynthesis and in animals as a building block of glycogen. Glucose can also be converted from bacterial xylose isomerase to fructose. In addition, glucose metabolites produce all nonessential amino acids, sugar alcohols such as mannitol and sorbitol, fatty acids, cholesterol and nucleic acids.

Regulatory role in cell differentiation

In addition to its well-known function as a cellular energy source, glucose has been identified as a master regulator of tissue maturation. A 2025 study by Stanford Medicine uncovered that glucose, in its intact (non-metabolized) form, can bind to various regulatory proteins involved in gene expression. One such protein is IRF6, which alters its conformation upon glucose binding, thereby influencing the expression of genes associated with stem cell differentiation. This regulatory role is independent of glucose’s catabolic function and has been observed across multiple tissue types, including skin, bone, fat, and white blood cells. The research demonstrated that even glucose analogs incapable of metabolism could promote differentiation, suggesting a signaling function for glucose. These findings have potential implications in understanding and treating diseases characterized by impaired differentiation, such as diabetes and certain cancers.

Pathology

Diabetes

Diabetes is a metabolic disorder where the body is unable to regulate Blood sugar, levels of glucose in the blood either because of a lack of insulin in the body or the failure, by cells in the body, to respond properly to insulin. Each of these situations can be caused by persistently high elevations of blood glucose levels, through pancreatic burnout and insulin resistance. The pancreas is the organ responsible for the secretion of the hormones insulin and glucagon. Insulin is a hormone that regulates glucose levels, allowing the body's cells to absorb and use glucose. Without it, glucose cannot enter the cell and therefore cannot be used as fuel for the body's functions. If the pancreas is exposed to persistently high elevations of blood glucose levels, the beta cell, insulin-producing cells in the pancreas could be damaged, causing a lack of insulin in the body. Insulin resistance occurs when the pancreas tries to produce more and more insulin in response to persistently elevated blood glucose levels. Eventually, the rest of the body becomes resistant to the insulin that the pancreas is producing, thereby requiring more insulin to achieve the same blood glucose-lowering effect, and forcing the pancreas to produce even more insulin to compete with the resistance. This negative spiral contributes to pancreatic burnout, and the disease progression of diabetes.

To monitor the body's response to blood glucose-lowering therapy, glucose levels can be measured. Blood glucose monitoring can be performed by multiple methods, such as the fasting glucose test which measures the level of glucose in the blood after 8 hours of fasting. Another test is the 2-hour glucose tolerance test (GTT)for this test, the person has a fasting glucose test done, then drinks a 75-gram glucose drink and is retested. This test measures the ability of the person's body to process glucose. Over time the blood glucose levels should decrease as insulin allows it to be taken up by cells and exit the blood stream.

Hypoglycemia management

Individuals with diabetes or other conditions that result in hypoglycemia, low blood sugar often carry small amounts of sugar in various forms. One sugar commonly used is glucose, often in the form of glucose tablets (glucose pressed into a tablet shape sometimes with one or more other ingredients as a binder), hard candy, or sugar packet.

Sources

Most dietary carbohydrates contain glucose, either as their only building block (as in the polysaccharides starch and glycogen), or together with another monosaccharide (as in the hetero-polysaccharides sucrose and lactose). Unbound glucose is one of the main ingredients of honey. Glucose is extremely abundant and has been isolated from a variety of natural sources across the world, including male cones of the coniferous tree ''Wollemia nobilis'' in Rome, the roots of ''Ilex asprella'' plants in China, and straws from rice in California.

Most dietary carbohydrates contain glucose, either as their only building block (as in the polysaccharides starch and glycogen), or together with another monosaccharide (as in the hetero-polysaccharides sucrose and lactose). Unbound glucose is one of the main ingredients of honey. Glucose is extremely abundant and has been isolated from a variety of natural sources across the world, including male cones of the coniferous tree ''Wollemia nobilis'' in Rome, the roots of ''Ilex asprella'' plants in China, and straws from rice in California.

Commercial production

Glucose is produced industrially from starch by enzyme, enzymatic

Glucose is produced industrially from starch by enzyme, enzymatic hydrolysis

Hydrolysis (; ) is any chemical reaction in which a molecule of water breaks one or more chemical bonds. The term is used broadly for substitution reaction, substitution, elimination reaction, elimination, and solvation reactions in which water ...

using glucose amylase or by the use of acids. Enzymatic hydrolysis has largely displaced acid-catalyzed hydrolysis reactions.[P. J. Fellows: ''Food Processing Technology. Woodhead Publishing'', 2016, , p. 197.] The result is glucose syrup (enzymatically with more than 90% glucose in the dry matter)[Thomas Becker, Dietmar Breithaupt, Horst Werner Doelle, Armin Fiechter, Günther Schlegel, Sakayu Shimizu, Hideaki Yamada: ''Biotechnology'', in: ''Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry'', 7th Edition, Wiley-VCH, 2011. . Volume 6, p. 48.] This is the reason for the former common name "starch sugar". The amylases most often come from ''Bacillus licheniformis''[The Amylase Research Society of Japan: ''Handbook of Amylases and Related Enzymes''. Elsevier, 2014, , p. 195.] or ''Bacillus subtilis'' (strain MN-385),[Alan Davidson: ''The Oxford Companion to Food''. OUP Oxford, 2014, , p. 527.] corn husk and sago are all used in various parts of the world. In the United States, corn starch

Cornflour, cornstarch, maize starch, or corn starch (American English) is the starch derived from corn (maize) grain. The starch is obtained from the endosperm of the seed, kernel. Corn starch is a common food ingredient, often used to thick ...

(from maize) is used almost exclusively. Some commercial glucose occurs as a component of invert sugar, a roughly 1:1 mixture of glucose and fructose that is produced from sucrose. In principle, cellulose could be hydrolyzed to glucose, but this process is not yet commercially practical.

Conversion to fructose

In the US, almost exclusively corn (more precisely, corn syrup) is used as glucose source for the production of isoglucose, which is a mixture of glucose and fructose, since fructose has a higher sweetening powerwith same physiological calorific value of 374 kilocalories per 100 g. The annual world production of isoglucose is 8 million tonnes (as of 2011).high-fructose corn syrup

High-fructose corn syrup (HFCS), also known as glucose–fructose, isoglucose, and glucose–fructose syrup, is a sweetener made from corn starch. As in the production of conventional corn syrup, the starch is broken down into glucose by enzy ...

(HFCS).

Commercial usage

Glucose is mainly used for the production of fructose and of glucose-containing foods. In foods, it is used as a sweetener, humectant, to increase the volume and to create a softer mouthfeel.

Glucose is mainly used for the production of fructose and of glucose-containing foods. In foods, it is used as a sweetener, humectant, to increase the volume and to create a softer mouthfeel.[Steve T. Beckett: ''Beckett's Industrial Chocolate Manufacture and Use''. John Wiley & Sons, 2017, , p. 82.] Typical chemical reactions of glucose when heated under water-free conditions are caramelization and, in presence of amino acids, the Maillard reaction.

In addition, various organic acids can be biotechnologically produced from glucose, for example by fermentation with ''Clostridium thermoaceticum'' to produce acetic acid

Acetic acid , systematically named ethanoic acid , is an acidic, colourless liquid and organic compound with the chemical formula (also written as , , or ). Vinegar is at least 4% acetic acid by volume, making acetic acid the main compone ...