Giles Daubeny, 1st Baron Daubeny on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

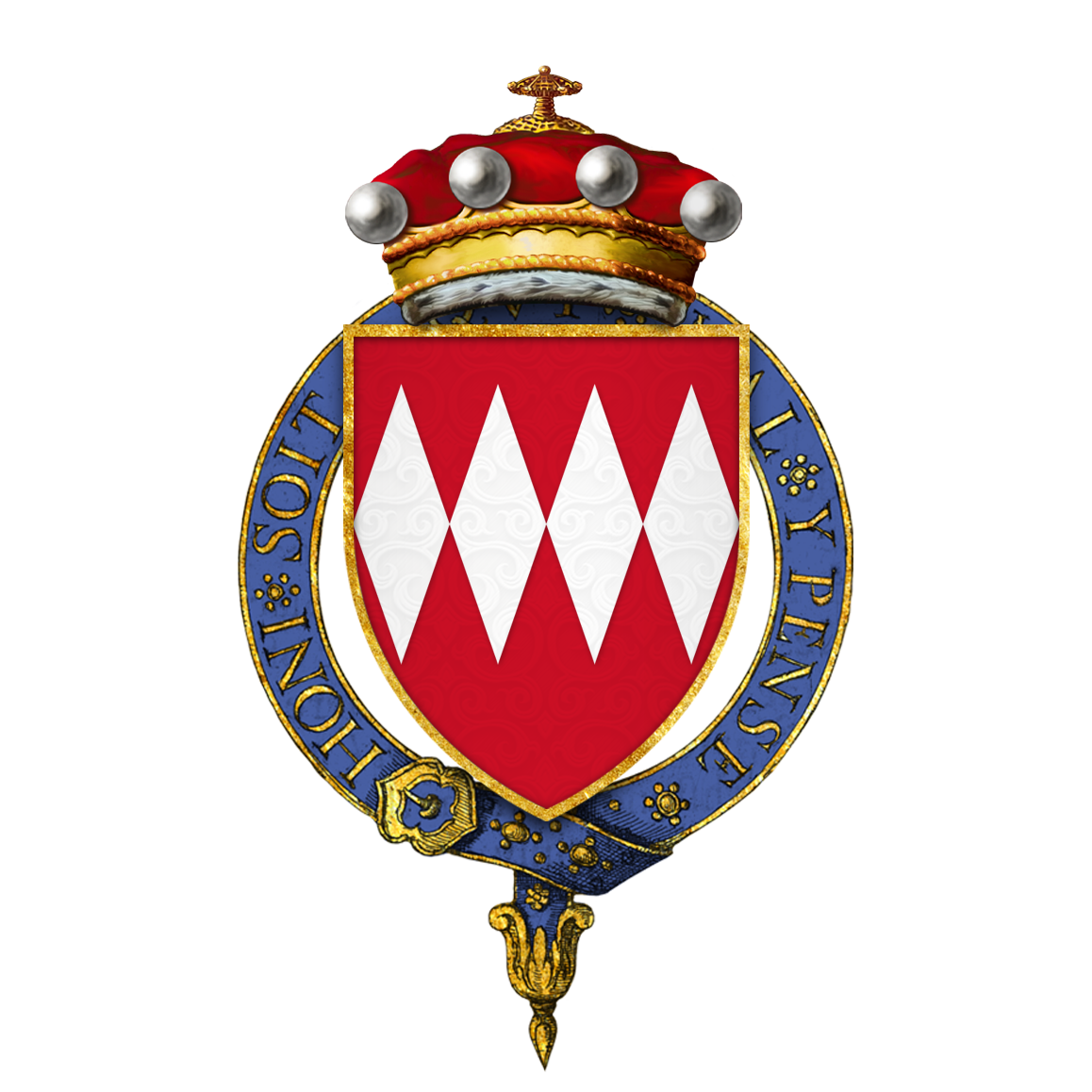

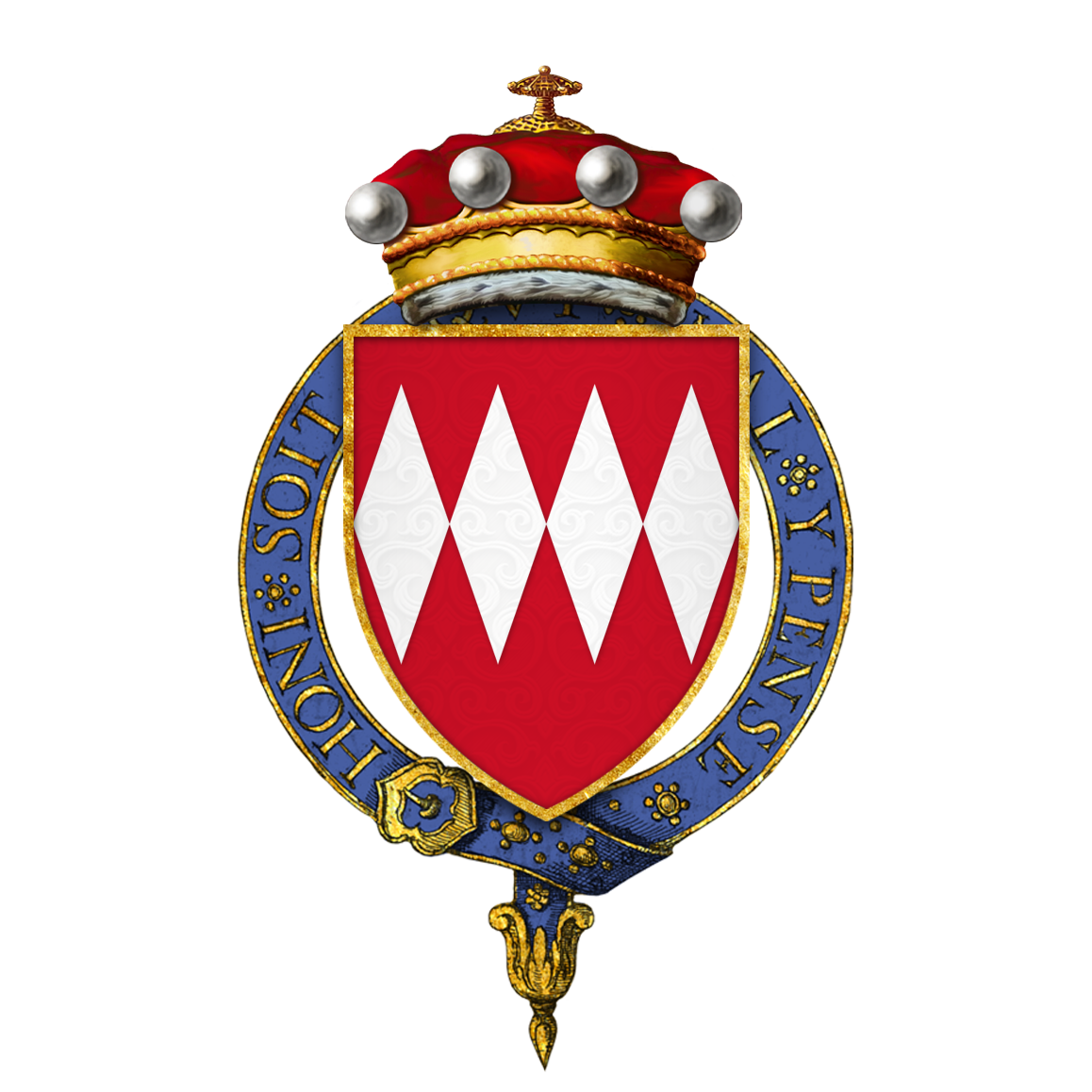

Giles Daubeney, 1st Baron Daubeney, KG PC (1 June 1451 – 21 May 1508) was an English soldier, diplomat, courtier and politician.

Giles Daubeney, 1st Baron Daubeney, KG PC (1 June 1451 – 21 May 1508) was an English soldier, diplomat, courtier and politician.

thePeerage.com (accessed 23 November 2010)

;Attribution Endnotes: ** Burke's ''Extinct and Dormant Peerage'' ** Collinson's ''Somerset'', iii. 109 ** Polydore Vergil ** Hall's ''Chronicle'' ** Gairdner's ''Memorials of Henry VII'' ** Gairdner's ''Letters, &c. of Richard III and Henry VII'' ** Leland's ''Collectanea'', iv. 230, 236, 238, 240, 245, 247, 259, 260 ** ''Spanish Calendar'', vol. i. ** ''Venetian Calendar'', vol. i. ** Campbell's ''Materials for the Reign of Henry VII'' * Halliwell's Letters, i. 179 * Anstis's History of the Garter * Will (Bennett, 16) in Somerset House {{DEFAULTSORT:Daubeney, Giles Daubeney, 1st Baron 1451 births 1508 deaths Members of the Privy Council of England Knights Bachelor Knights of the Garter Barons Daubeney High Sheriffs of Cornwall High Sheriffs of Devon High Sheriffs of Dorset High Sheriffs of Somerset People from Somerset 15th-century soldiers 16th-century English soldiers English MPs 1478 Burials at Westminster Abbey 16th-century English nobility

Giles Daubeney, 1st Baron Daubeney, KG PC (1 June 1451 – 21 May 1508) was an English soldier, diplomat, courtier and politician.

Giles Daubeney, 1st Baron Daubeney, KG PC (1 June 1451 – 21 May 1508) was an English soldier, diplomat, courtier and politician.

Origins

Giles Daubeney was the eldest son and heir of Sir William Daubeney (1424-1460/1) of South Ingelby in Lincolnshire, andSouth Petherton

South Petherton is a village and civil parish in the South Somerset district of Somerset, England, located east of Ilminster and north of Crewkerne. The parish had a population of 3,367 in 2011 and includes the smaller village of Over Stra ...

and Barrington Court in Somerset, MP for Bedfordshire

Bedfordshire (; abbreviated Beds) is a ceremonial county in the East of England. The county has been administered by three unitary authorities, Borough of Bedford, Central Bedfordshire and Borough of Luton, since Bedfordshire County Council wa ...

1448/9, and Sheriff of Cornwall

Sheriffs and high sheriffs of Cornwall: a chronological list:

The right to choose high sheriffs each year is vested in the Duchy of Cornwall. The Privy Council, chaired by the sovereign, chooses the sheriffs of all other English counties, oth ...

1452/3. His mother, Alice Stourton, was the youngest of the three daughters and co-heiresses (by his 3rd wife Katherine Payne) of John Stourton (died 1438), builder of the Abbey Farm House, Preston Plucknett

Preston Plucknett is a suburb of Yeovil in Somerset, England. It was once a small village, and a separate civil parish until 1930, when it was absorbed into the neighbouring parishes of Yeovil, Brympton and West Coker. It was listed in the Dome ...

and owner of Brympton d'Evercy

Brympton d'Evercy (alternatively Brympton House), a grade I listed manor house near Yeovil in the county of Somerset, England, has been called the most beautiful in England. In 1927 the British magazine '' Country Life'' devoted three articles ...

in Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lord_ ...

, who was seven times MP for Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lord_ ...

, in 1419, 1420, December 1421, 1423, 1426, 1429 and 1435. He was probably born at South Petherton

South Petherton is a village and civil parish in the South Somerset district of Somerset, England, located east of Ilminster and north of Crewkerne. The parish had a population of 3,367 in 2011 and includes the smaller village of Over Stra ...

in Somerset, where his father seems to have been resident. He had a brother James and sister Eleanor.

Career

In 1475 he went over to France withEdward IV

Edward IV (28 April 1442 – 9 April 1483) was King of England from 4 March 1461 to 3 October 1470, then again from 11 April 1471 until his death in 1483. He was a central figure in the Wars of the Roses, a series of civil wars in England ...

, from whom he obtained a licence before going to make a trust-deed of his lands in the counties of Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lord_ ...

and Dorset

Dorset ( ; archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the unitary authority areas of Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole and Dorset (unitary authority), Dors ...

. He was then designated esquire, and he went in command of four men-at-arms and fifty archers. Soon after he became one of the esquires for the king's body, and two years later he had a grant for life of the custody of the king's park at Petherton, near Bridgwater

Bridgwater is a large historic market town and civil parish in Somerset, England. Its population currently stands at around 41,276 as of 2022. Bridgwater is at the edge of the Somerset Levels, in level and well-wooded country. The town lies alon ...

. Member of Parliament for Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lord_ ...

in 1477–8, he was knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the Christian denomination, church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood ...

before the end of King Edward's reign. He was also present at the coronation of Richard III

Richard III (2 October 145222 August 1485) was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 26 June 1483 until his death in 1485. He was the last king of the House of York and the last of the Plantagenet dynasty. His defeat and death at the Battl ...

on 6 July 1483.

He was consulted before anyone else by Reginald Bray

Sir Reginald Bray (c. 1440 – 5 August 1503) was an English administrator and statesman. He was the Chancellor of the Duchy and County Palatine of Lancaster under Henry VII, briefly Treasurer of the Exchequer, and one of the most influenti ...

about the projected invasion of Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond, planned with Henry Stafford, 2nd Duke of Buckingham

Henry Stafford, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, KG (4 September 1455 – 2 November 1483) was an English nobleman known as the namesake of Buckingham's rebellion, a failed but significant collection of uprisings in England and parts of Wales agains ...

. On the failure of Buckingham's rebellion

Buckingham's rebellion was a failed but significant uprising, or collection of uprisings, of October 1483 in England and parts of Wales against Richard III of England.

To the extent that these local risings had a central coordination, the plo ...

he with others fled to Richmond in Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo language, Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, Historical region, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known ...

, and he was consequently attainted

In English criminal law, attainder or attinctura was the metaphorical "stain" or "corruption of blood" which arose from being condemned for a serious capital crime (felony or treason). It entailed losing not only one's life, property and hereditary ...

in Richard's parliament. The custody of Petherton Park

Petherton Park (also known as North Petherton Park or Newton Park) was a Deer park around North Petherton within the English county of Somerset.

The origins are unclear but the area was part of an earlier Royal Forest stretching from the River P ...

was granted to Richard FitzHugh, 6th Baron FitzHugh

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from Old Frankish and is a compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' and ''*hardu-'' 'strong, brave, hardy', and it therefore means 'stron ...

and Daubeney's lands in Somerset, Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (abbreviated Lincs.) is a county in the East Midlands of England, with a long coastline on the North Sea to the east. It borders Norfolk to the south-east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south-west, Leicestershire ...

and Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

were confiscated.

Under Henry VII

His fortunes were revived when Henry became King Henry VII in 1485. His attainder was reversed in Henry's first parliament, and he became aprivy councillor

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

. On 2 November he was appointed Master of the Mint

Master of the Mint is a title within the Royal Mint given to the most senior person responsible for its operation. It was an important office in the governments of Scotland and England, and later Great Britain and then the United Kingdom, between ...

, an office in which Bartholomew Reade

Sir Bartholomew Reade (or Rede; died 1505) was an English goldsmith and politician who served as Lord Mayor of London.

Family

Reade was born in Cromer, Norfolk. His parents were Roger Reade (d. 1470) and his wife Catherine, and he had at least t ...

of London, goldsmith, as the practical 'worker of monies,' was associated with him in survivorship.The mastership of the king's harthounds had been granted to him on 12 October before. He had also the offices of constable of Winchester Castle

Winchester Castle is a medieval building in Winchester, Hampshire, England. It was founded in 1067. Only the Great Hall still stands; it houses a museum of the history of Winchester.

History

Early history

Around AD 70 the Romans constructed a ...

, constable of Bristol Castle

Bristol Castle was a Norman castle built for the defence of Bristol. Remains can be seen today in Castle Park near the Broadmead Shopping Centre, including the sally port. Built during the reign of William the Conqueror, and later owned by Rob ...

, steward of the lands of the duchy of Lancaster

The Duchy of Lancaster is the private estate of the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, British sovereign as Duke of Lancaster. The principal purpose of the estate is to provide a source of independent income to the sovereign. The estate consists of ...

in Hampshire and Dorset, steward of the lands of the earldom of Salisbury in Somerset, and various minor appointments given him about the same time. On 7 March 1486 he was appointed Lieutenant of Calais

The town of Calais, now part of France, was in English hands from 1347 to 1558, and this page lists the commanders of Calais, holding office from the English Crown, called at different times Captain of Calais, King's Lieutenant of Calais (Castle ...

for a term of seven years, as reward for his services to the king; and on 12 March he was created Baron Daubeney with succession in tail male.

On 15 December 1486 he was named at the head of a major embassy to treat for a league with Maximilian, King of the Romans. About this time he was made a knight of the Garter

The Most Noble Order of the Garter is an order of chivalry founded by Edward III of England in 1348. It is the most senior order of knighthood in the British honours system, outranked in precedence only by the Victoria Cross and the George ...

. On 25 November 1487 he was present at the coronation of Elizabeth of York

Elizabeth of York (11 February 1466 – 11 February 1503) was Queen of England from her marriage to King Henry VII on 18 January 1486 until her death in 1503. Elizabeth married Henry after his victory at the Battle of Bosworth Field, which ma ...

. On 20 December 1487 he was appointed one of the chamberlains of the receipt of the exchequer. He appears about this time to have gone on an embassy to France, and then was with the king at Greenwich

Greenwich ( , ,) is a town in south-east London, England, within the ceremonial county of Greater London. It is situated east-southeast of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwich ...

on Twelfth Night

''Twelfth Night'', or ''What You Will'' is a romantic comedy by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written around 1601–1602 as a Twelfth Night's entertainment for the close of the Christmas season. The play centres on the twins Vio ...

, 1488. On 7 July 1488 of the same year he and Richard Foxe

Richard Foxe (sometimes Richard Fox) ( 1448 – 5 October 1528) was an English churchman, the founder of Corpus Christi College, Oxford. He was successively Bishop of Exeter, Bath and Wells, Durham, and Winchester, and became also Lo ...

, bishop of Exeter

The Bishop of Exeter is the ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Exeter in the Province of Canterbury. Since 30 April 2014 the ordinary has been Robert Atwell.

, as commissioners for Henry VII, arranged with the Spanish ambassadors the first treaty for the marriage of Prince Arthur Prince Arthur may refer to:

* Arthur I, Duke of Brittany (1187-1203), nephew and possible heir of Richard I of England

* Arthur, Prince of Wales (1486–1502), eldest son Henry VII of England

* Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn (1850� ...

with Catherine of Aragon

Catherine of Aragon (also spelt as Katherine, ; 16 December 1485 – 7 January 1536) was Queen of England as the first wife of King Henry VIII from their marriage on 11 June 1509 until their annulment on 23 May 1533. She was previously ...

.

Military operations

In 1489 he crossed toCalais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's prefecture is its third-largest city of Arras. Th ...

, raised the siege of Diksmuide

(; french: Dixmude, ; vls, Diksmude) is a Belgian city and municipality in the Flemish province of West Flanders. The municipality comprises the city of proper and the former communes of Beerst, Esen, Kaaskerke, Keiem, Lampernisse, Leke, N ...

, and took Ostend

Ostend ( nl, Oostende, ; french: link=no, Ostende ; german: link=no, Ostende ; vls, Ostende) is a coastal city and municipality, located in the province of West Flanders in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It comprises the boroughs of Mariakerk ...

from the French. In 1490 he was sent to the Duchess Anne in Brittany to arrange the terms of a treaty against France, and later in the year he was appointed commander of a body of troops sent to her assistance. In June 1492, Brittany having now lost her independence, he was again sent over to France, but this time as ambassador, with Foxe, then bishop of Bath and Wells

The Bishop of Bath and Wells heads the Church of England Diocese of Bath and Wells in the Province of Canterbury in England.

The present diocese covers the overwhelmingly greater part of the (ceremonial) county of Somerset and a small area of Do ...

, to negotiate a treaty of peace with Charles VIII. No settlement, however, was arrived at, and the king four months later invaded France and besieged Boulogne. The French then at once agreed to treat, and Daubeney was commissioned to arrange a treaty with the Sieur des Querdes, which was concluded at Étaples

Étaples or Étaples-sur-Mer (; vls, Stapel, lang; pcd, Étape) is a commune in the Pas-de-Calais department in northern France. It is a fishing and leisure port on the Canche river.

History

Étaples takes its name from having been a medieval ...

on 3 November.

In 1495, after the execution of Sir William Stanley, he was made Lord Chamberlain

The Lord Chamberlain of the Household is the most senior officer of the Royal Household of the United Kingdom, supervising the departments which support and provide advice to the Sovereign of the United Kingdom while also acting as the main cha ...

. On the meeting of parliament in October the same year he was elected one of the triers of petitions, as he also was in the parliaments of 1497 and 1504. In 1496 he, as the lieutenant of Calais, with Sir Richard Nanfan his deputy there, was commissioned to receive for the king payment of the twenty-five thousand francs due half-yearly from the French king under the Peace of Étaples

The Peace of Étaples was signed on 3 November 1492 in Étaples between Charles VIII of France and Henry VII of England. Charles agreed to end his support for the Yorkist Pretender Perkin Warbeck, in return for being recognised as ruler of the Du ...

.

In 1497 the king had prepared an army to invade Scotland to punish James IV

James IV (17 March 1473 – 9 September 1513) was King of Scotland from 11 June 1488 until his death at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. He inherited the throne at the age of fifteen on the death of his father, James III, at the Battle of Sauchi ...

for his support of Perkin Warbeck

Perkin Warbeck ( 1474 – 23 November 1499) was a pretender to the English throne claiming to be Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York, who was the second son of Edward IV and one of the so-called "Princes in the Tower". Richard, were he alive, ...

, and had given the command to Daubeney. He had hardly marched when he was recalled to put down the Cornish rebels

Cornish Rebels are an amateur rugby league team based in Redruth, Cornwall. They were founded in January 2013 by John Beach and Rob Butland. Cornish Rebels RLFC are affiliated with the Rugby Football League, rugby league's governing body in the ...

, who came to Blackheath Blackheath may refer to:

Places England

*Blackheath, London, England

** Blackheath railway station

**Hundred of Blackheath, Kent, an ancient hundred in the north west of the county of Kent, England

*Blackheath, Surrey, England

** Hundred of Blackh ...

unmolested, and was criticised by the king. He set on the rebels at Deptford Strand, and they took him prisoner, but soon after let him go and were defeated (17 June). This ended the Cornish revolt. In September, Perkin having landed in Cornwall, there was a new disturbance in the west, to meet which Daubeney was sent with a troop of light horse, announcing that the king himself would shortly follow. The siege of Exeter

Exeter () is a city in Devon, South West England. It is situated on the River Exe, approximately northeast of Plymouth and southwest of Bristol.

In Roman Britain, Exeter was established as the base of Legio II Augusta under the personal comm ...

was raised on his approach, and Perkin soon left.

Later life

In 1500 Daubeney accompanied Henry VII to Calais, and was present at his meeting with theArchduke Philip

Philip the Handsome, es, Felipe, french: Philippe, nl, Filips (22 July 1478 – 25 September 1506), also called the Fair, was ruler of the Burgundian Netherlands and titular Duke of Burgundy from 1482 to 1506, as well as the first Habsburg Kin ...

. In 1501 he had charge of many of the arrangements for Catherine's reception in London, and in November he was a witness to Prince Arthur's assignment of her dower. On Thursday 18 May 1508, after riding with the king from Eltham

Eltham ( ) is a district of southeast London, England, within the Royal Borough of Greenwich. It is east-southeast of Charing Cross, and is identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London. The three wards of Elt ...

to Greenwich, he was taken suddenly ill. He was ferried down the river to his house in London. On Saturday the 20th he received the sacrament. He died about ten o'clock in the evening of the 21st, aged 56, and his obit, according to old ecclesiastical custom, was kept on the 22nd. On the afternoon of the 26th his body was conveyed to Westminster by the river, and almost all the nobility of the kingdom witnessed his funeral rites.

He had in his will appointed Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

as his place of sepulture, and his body rests now under a monument in St Paul's chapel (Westminster Abbey) with alabaster

Alabaster is a mineral or rock that is soft, often used for carving, and is processed for plaster powder. Archaeologists and the stone processing industry use the word differently from geologists. The former use it in a wider sense that includes ...

effigies of himself and his wife by his side. A Latin epitaph was written for him by Bernard André

Bernard André, O.E.S.A. (1450–1522), also known as Andreas, was a French Augustinian friar and poet, who was a noted chronicler of the reign of Henry VII of England, and poet laureate.

A native of Toulouse, André was tutor to Prince Arthur ...

, and may have been inscribed on his tomb.

Family

His wife Elizabeth, was a daughter of Sir John Arundell of Lanherne in Cornwall. She survived him some years, and obtained from Henry VIII the wardship of his son and heir Henry, 2nd Lord Daubeney, later 1st Earl of Bridgewater. Their first daughter, Cecily Daubeney, marriedJohn Bourchier, 1st Earl of Bath

John Bourchier, 1st Earl of Bath (20 July 1470 – 30 April 1539) was named Earl of Bath in 1536. He was feudal baron of Bampton in Devon.

Origins

John Bourchier was born in Essex, England, the eldest son and heir of Fulk Bourchier, 10th Baron F ...

, and had descendants. Their second daughter, Anne, married Alexander Buller.

Notes

References

* * * * * Daubeney, Giles, first Baron DaubenethePeerage.com (accessed 23 November 2010)

;Attribution Endnotes: ** Burke's ''Extinct and Dormant Peerage'' ** Collinson's ''Somerset'', iii. 109 ** Polydore Vergil ** Hall's ''Chronicle'' ** Gairdner's ''Memorials of Henry VII'' ** Gairdner's ''Letters, &c. of Richard III and Henry VII'' ** Leland's ''Collectanea'', iv. 230, 236, 238, 240, 245, 247, 259, 260 ** ''Spanish Calendar'', vol. i. ** ''Venetian Calendar'', vol. i. ** Campbell's ''Materials for the Reign of Henry VII'' * Halliwell's Letters, i. 179 * Anstis's History of the Garter * Will (Bennett, 16) in Somerset House {{DEFAULTSORT:Daubeney, Giles Daubeney, 1st Baron 1451 births 1508 deaths Members of the Privy Council of England Knights Bachelor Knights of the Garter Barons Daubeney High Sheriffs of Cornwall High Sheriffs of Devon High Sheriffs of Dorset High Sheriffs of Somerset People from Somerset 15th-century soldiers 16th-century English soldiers English MPs 1478 Burials at Westminster Abbey 16th-century English nobility