Gilbert K. Chesterton on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

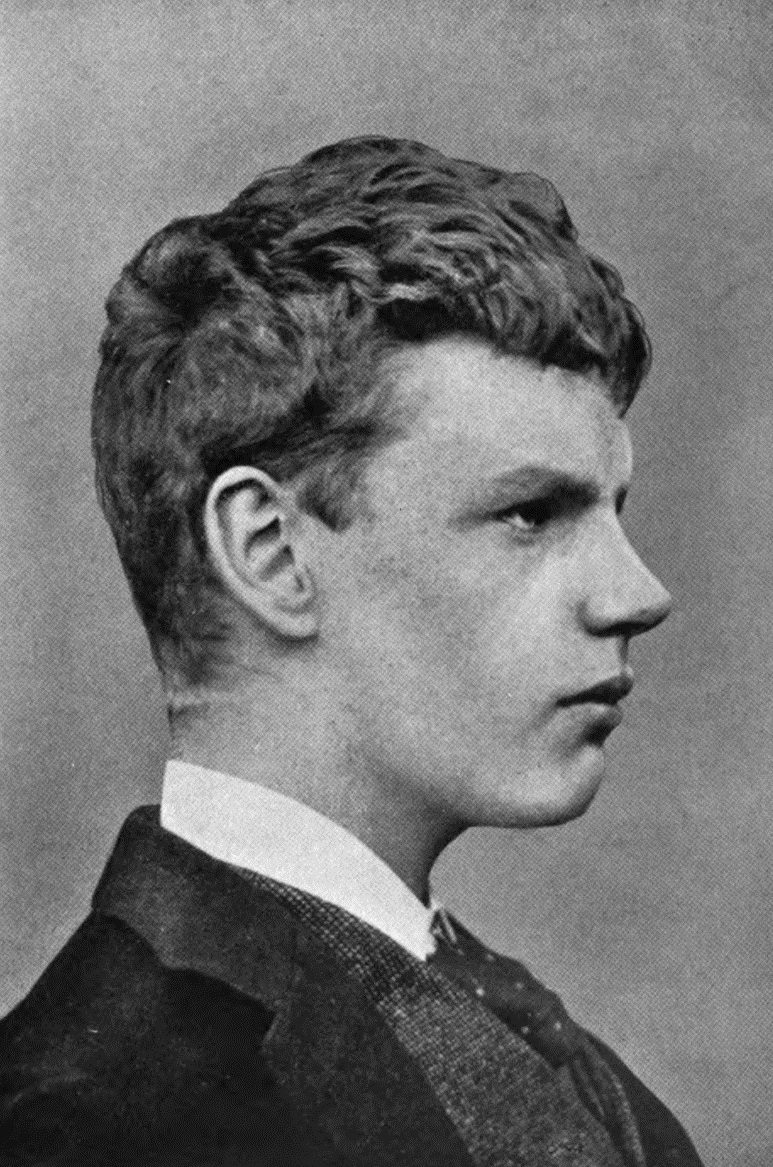

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936) was an English writer,

Chesterton was born in

Chesterton was born in

Chesterton loved to debate, often engaging in friendly public disputes with such men as

Chesterton loved to debate, often engaging in friendly public disputes with such men as

philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

, Christian apologist

Christian apologetics ( grc, ἀπολογία, "verbal defense, speech in defense") is a branch of Christian theology that defends Christianity.

Christian apologetics has taken many forms over the centuries, starting with Paul the Apostle in th ...

, and literary and art critic. He has been referred to as the "prince of paradox

A paradox is a logically self-contradictory statement or a statement that runs contrary to one's expectation. It is a statement that, despite apparently valid reasoning from true premises, leads to a seemingly self-contradictory or a logically u ...

". Of his writing style, ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, to ...

'' observed: "Whenever possible, Chesterton made his points with popular sayings, proverbs, allegories—first carefully turning them inside out."

Chesterton created the fictional priest-detective Father Brown

Father Brown is a fictional Roman Catholic priest and amateur detective who is featured in 53 short stories published between 1910 and 1936 written by English author G. K. Chesterton. Father Brown solves mysteries and crimes using his intuiti ...

, and wrote on apologetics

Apologetics (from Greek , "speaking in defense") is the religious discipline of defending religious doctrines through systematic argumentation and discourse. Early Christian writers (c. 120–220) who defended their beliefs against critics and ...

. Even some of those who disagree with him have recognised the wide appeal of such works as ''Orthodoxy

Orthodoxy (from Greek: ) is adherence to correct or accepted creeds, especially in religion.

Orthodoxy within Christianity refers to acceptance of the doctrines defined by various creeds and ecumenical councils in Antiquity, but different Churc ...

'' and ''The Everlasting Man

''The Everlasting Man'' is a Christian apologetics book written by G. K. Chesterton, published in 1925. It is, to some extent, a deliberate rebuttal of H. G. Wells' ''The Outline of History'', disputing Wells' portrayals of human life and civi ...

''. Chesterton routinely referred to himself as an "orthodox

Orthodox, Orthodoxy, or Orthodoxism may refer to:

Religion

* Orthodoxy, adherence to accepted norms, more specifically adherence to creeds, especially within Christianity and Judaism, but also less commonly in non-Abrahamic religions like Neo-pag ...

" Christian, and came to identify this position more and more with Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, eventually converting to Roman Catholicism from high church

The term ''high church'' refers to beliefs and practices of Christian ecclesiology, liturgy, and theology that emphasize formality and resistance to modernisation. Although used in connection with various Christian traditions, the term originate ...

Anglicanism

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the ...

. Biographers have identified him as a successor to such Victorian authors as Matthew Arnold

Matthew Arnold (24 December 1822 – 15 April 1888) was an English poet and cultural critic who worked as an inspector of schools. He was the son of Thomas Arnold, the celebrated headmaster of Rugby School, and brother to both Tom Arnold, lite ...

, Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher. A leading writer of the Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art, literature and philosophy.

Born in Ecclefechan, Dum ...

, John Henry Newman

John Henry Newman (21 February 1801 – 11 August 1890) was an English theologian, academic, intellectual, philosopher, polymath, historian, writer, scholar and poet, first as an Anglican ministry, Anglican priest and later as a Catholi ...

and John Ruskin

John Ruskin (8 February 1819 20 January 1900) was an English writer, philosopher, art critic and polymath of the Victorian era. He wrote on subjects as varied as geology, architecture, myth, ornithology, literature, education, botany and politi ...

.

Biography

Early life

Chesterton was born in

Chesterton was born in Campden Hill

Campden Hill is a hill in Kensington, West London, bounded by Holland Park Avenue on the north, Kensington High Street on the south, Kensington Palace Gardens on the east and Abbotsbury Road on the west. The name derives from the former ''Campde ...

in Kensington

Kensington is a district in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in the West End of London, West of Central London.

The district's commercial heart is Kensington High Street, running on an east–west axis. The north-east is taken up b ...

, London, the son of Edward Chesterton (1841–1922), an estate agent, and Marie Louise, née Grosjean, of Swiss French origin. Chesterton was baptised at the age of one month into the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

, though his family themselves were irregularly practising Unitarians. According to his autobiography, as a young man he became fascinated with the occult

The occult, in the broadest sense, is a category of esoteric supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving otherworldly agency, such as magic and mysticism a ...

and, along with his brother Cecil

Cecil may refer to:

People with the name

* Cecil (given name), a given name (including a list of people and fictional characters with the name)

* Cecil (surname), a surname (including a list of people with the name)

Places Canada

*Cecil, Alberta, ...

, experimented with Ouija boards

The ouija ( , ), also known as a spirit board or talking board, is a flat board marked with the letters of the Latin alphabet, the numbers 0–9, the words "yes", "no", occasionally "hello" and "goodbye", along with various symbols and grap ...

. He was educated at St Paul's School, then attended the Slade School of Art

The UCL Slade School of Fine Art (informally The Slade) is the art school of University College London (UCL) and is based in London, England. It has been ranked as the UK's top art and design educational institution. The school is organised as ...

to become an illustrator. The Slade is a department of University College London

, mottoeng = Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £143 million (2020)

, budget = ...

, where Chesterton also took classes in literature, but did not complete a degree in either subject. He married Frances Blogg

Frances Alice Blogg Chesterton (28 June 1869 – 12 December 1938) was an English author of verse, songs and school drama. She was the wife of G. K. Chesterton and had a large role in his career as amanuensis and personal manager.

Early life

...

in 1901; the marriage lasted the rest of his life. Chesterton credited Frances with leading him back to Anglicanism

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the ...

, though he later considered Anglicanism to be a "pale imitation". He entered full communion with the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

in 1922. The couple were unable to have children.

A friend from schooldays was Edmund Clerihew Bentley

Edmund Clerihew Bentley (10 July 1875 – 30 March 1956), who generally published under the names E. C. Bentley or E. Clerihew Bentley, was a popular English novelist and humorist, and inventor of the clerihew, an irregular form of humorous verse ...

, inventor of the clerihew

A clerihew () is a whimsical, four-line biographical poem of a type invented by Edmund Clerihew Bentley. The first line is the name of the poem's subject, usually a famous person, and the remainder puts the subject in an absurd light or reveals som ...

, a whimsical, four-line biographical poem. Chesterton himself wrote clerihews and illustrated his friend's first published collection of poetry, ''Biography for Beginners'' (1905), which popularised the clerihew form. He became godfather to Bentley's son, Nicolas

Nicolas or Nicolás may refer to:

People Given name

* Nicolas (given name)

Mononym

* Nicolas (footballer, born 1999), Brazilian footballer

* Nicolas (footballer, born 2000), Brazilian footballer

Surname Nicolas

* Dafydd Nicolas (c.1705–1774), ...

, and opened his novel ''The Man Who Was Thursday'' with a poem written to Bentley.

Career

In September 1895, Chesterton began working for the London publisher George Redway, where he remained for just over a year. In October 1896 he moved to the publishing houseT. Fisher Unwin

T. Fisher Unwin was the London publishing house founded by Thomas Fisher Unwin, husband of British Liberal politician Jane Cobden in 1882.

Unwin was a co-founder of the Johnson Club, formed 13 September 1884, to mark the hundred years since the ...

, where he remained until 1902. During this period he also undertook his first journalistic work, as a freelance art and literary critic. In 1902 the '' Daily News'' gave him a weekly opinion column, followed in 1905 by a weekly column in ''The Illustrated London News

''The Illustrated London News'' appeared first on Saturday 14 May 1842, as the world's first illustrated weekly news magazine. Founded by Herbert Ingram, it appeared weekly until 1971, then less frequently thereafter, and ceased publication in ...

'', for which he continued to write for the next thirty years.

Early on Chesterton showed a great interest in and talent for art. He had planned to become an artist, and his writing shows a vision that clothed abstract ideas in concrete and memorable images. Even his fiction contained carefully concealed parables. Father Brown

Father Brown is a fictional Roman Catholic priest and amateur detective who is featured in 53 short stories published between 1910 and 1936 written by English author G. K. Chesterton. Father Brown solves mysteries and crimes using his intuiti ...

is perpetually correcting the incorrect vision of the bewildered folks at the scene of the crime and wandering off at the end with the criminal to exercise his priestly role of recognition and repentance. For example, in the story "The Flying Stars", Father Brown entreats the character Flambeau to give up his life of crime: "There is still youth and honour and humour in you; don't fancy they will last in that trade. Men may keep a sort of level of good, but no man has ever been able to keep on one level of evil. That road goes down and down. The kind man drinks and turns cruel; the frank man kills and lies about it. Many a man I've known started like you to be an honest outlaw, a merry robber of the rich, and ended stamped into slime."

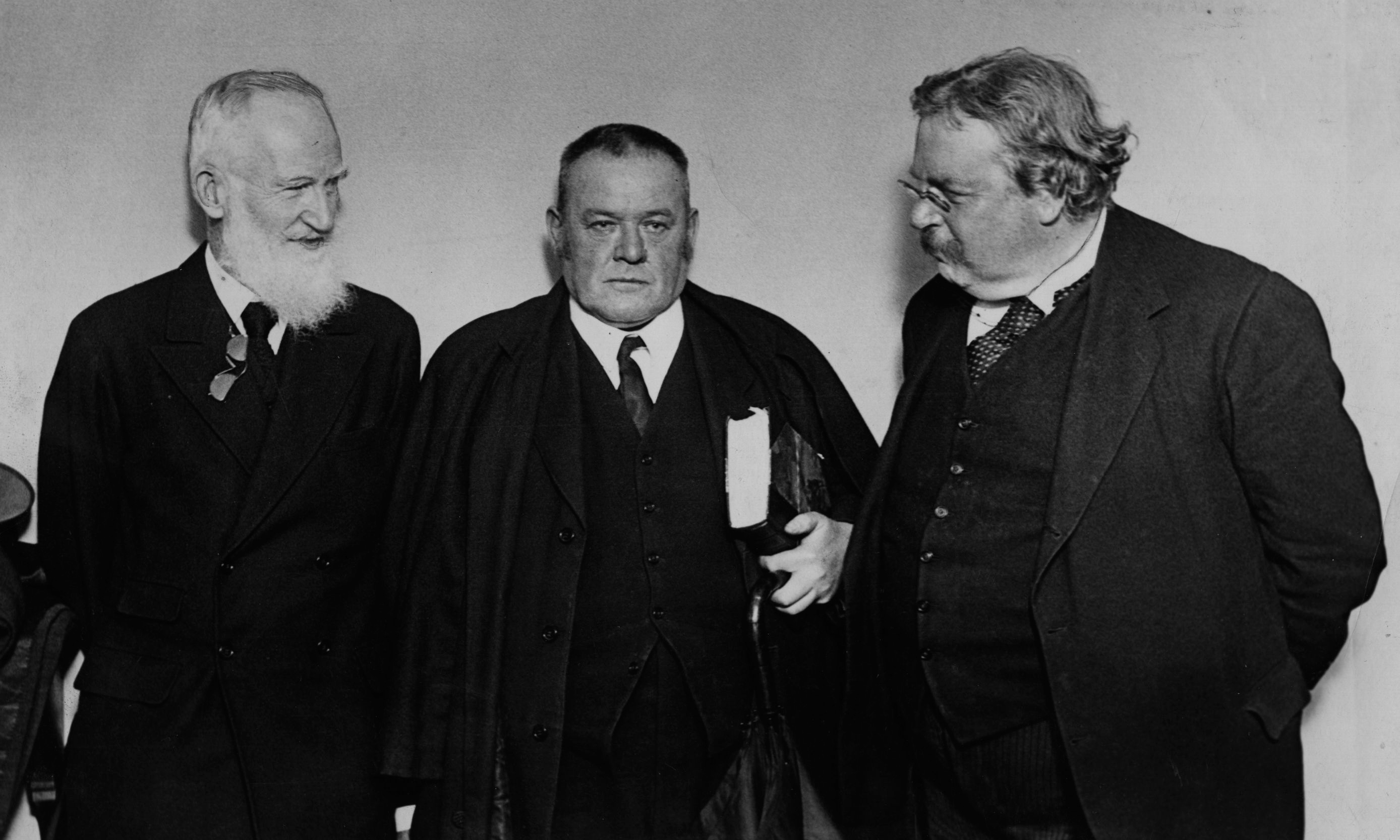

Chesterton loved to debate, often engaging in friendly public disputes with such men as

Chesterton loved to debate, often engaging in friendly public disputes with such men as George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

, H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells"Wells, H. G."

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

Chesterton died of

Chesterton died of

Chesterton is often associated with his close friend, the poet and essayist

Chesterton is often associated with his close friend, the poet and essayist

"The Trees of Pride"

1922 * "The Crime of the Communist", ''Collier's Weekly'', July 1934. * "The Three Horsemen", ''Collier's Weekly'', April 1935. * "The Ring of the Lovers", ''Collier's Weekly'', April 1935. * "A Tall Story", ''Collier's Weekly'', April 1935. * "The Angry Street – A Bad Dream", ''Famous Fantastic Mysteries'', February 1947.

''Gilbert Keith Chesterton''

London: Chelsea Publishing Company. * Cammaerts, Émile (1937). ''The Laughing Prophet: The Seven Virtues And G. K. Chesterton''. London: Methuen & Co., Ltd. * Campbell, W. E. (1908)

"G.K. Chesterton: Inquisitor and Democrat"

''The Catholic World'', Vol. LXXXVIII, pp. 769–782. * Campbell, W. E. (1909)

"G.K. Chesterton: Catholic Apologist"

''The Catholic World'', Vol. LXXXIX, No. 529, pp. 1–12. * Chesterton, Cecil (1908)

''G.K. Chesterton: A Criticism''

London: Alston Rivers (Rep. b

John Lane Company

1909). * Clipper, Lawrence J. (1974). ''G.K. Chesterton''. New York: Twayne Publishers. * Coates, John (1984). ''Chesterton and the Edwardian Cultural Crisis''. Hull University Press. * Coates, John (2002). ''G.K. Chesterton as Controversialist, Essayist, Novelist, and Critic''.

"G.K. Chesterton"

In: ''Some Impressions of my Elders''. New York: The Macmillan Company, pp. 90–112. * * ''Gilbert Magazine'' (November/December 2008). Vol. 12, No. 2-3, ''Special Issue: Chesterton & The Jews''. * Haldane, John. 'Chesterton's Philosophy of Education', philosophy, Vol. 65, No. 251 (Jan. 1990), pp. 65–80. *

"The Reactionary"

''The Atlantic''. * Herts, B. Russell (1914)

"Gilbert K. Chesterton: Defender of the Discarded"

In: ''Depreciations''. New York: Albert & Charles Boni, pp. 65–86. * Hollis, Christopher (1970). ''The Mind of Chesterton''. London: Hollis & Carter. * Hunter, Lynette (1979). ''G.K. Chesterton: Explorations in Allegory''. London: Macmillan Press. * Jaki, Stanley (1986). ''Chesterton: A Seer of Science''. University of Illinois Press. * Jaki, Stanley (1986). "Chesterton's Landmark Year". In: ''Chance or Reality and Other Essays''. University Press of America. * Kenner, Hugh (1947). ''Paradox in Chesterton''. New York: Sheed & Ward. * Roger Kimball, Kimball, Roger (2011)

"G. K. Chesterton: Master of Rejuvenation"

''The New Criterion'', Vol. XXX, p. 26. * Russell Kirk, Kirk, Russell (1971). "Chesterton, Madmen, and Madhouses", ''Modern Age'', Vol. XV, No. 1, pp. 6–16. * Knight, Mark (2004). ''Chesterton and Evil''. Fordham University Press. * Lea, F. A. (1947). "G. K. Chesterton". In: Donald Attwater (ed.) ''Modern Christian Revolutionaries''. New York: Devin-Adair Co. * McCleary, Joseph R. (2009). ''The Historical Imagination of G.K. Chesterton: Locality, Patriotism, and Nationalism''. Taylor & Francis. * Marshall McLuhan, McLuhan, Marshall (January 1936)

"G. K. Chesterton: A Practical Mystic"

''Dalhousie Review'', 15 (4): 455–464. * * Oddie, William (2010). ''Chesterton and the Romance of Orthodoxy: The Making of GKC, 1874–1908''. Oxford University Press. * Alfred Richard Orage, Orage, Alfred Richard. (1922)

"G.K. Chesterton on Rome and Germany"

In: ''Readers and Writers (1917–1921)''. London: George Allen & Unwin, pp. 155–161. * Oser, Lee (2007). ''The Return of Christian Humanism: Chesterton, Eliot, Tolkien, and the Romance of History''. University of Missouri Press. * * * Peck, William George (1920)

"Mr. G.K. Chesterton and the Return to Sanity"

In: ''From Chaos to Catholicism''. London: George Allen & Unwin, pp. 52–92. * Raymond, E. T. (1919)

"Mr. G.K. Chesterton"

In: ''All & Sundry''. London: T. Fisher Unwin, pp. 68–76. * James V. Schall, Schall, James V. (2000). ''Schall on Chesterton: Timely Essays on Timeless Paradoxes''. Catholic University of America Press. * Scott, William T. (1912)

''Chesterton and Other Essays''

Cincinnati: Jennings & Graham. * Seaber, Luke (2011). ''G.K. Chesterton's Literary Influence on George Orwell: A Surprising Irony''.

"The Adventures of a Journalist: G.K. Chesterton"

In: ''The Catholic Spirit in Modern English Literature''. New York: The Macmillan Company, pp. 229–248. * Edwin Emery Slosson, Slosson, Edwin E. (1917)

"G.K. Chesterton: Knight Errant of Orthodoxy"

In: ''Six Major Prophets''. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, pp. 129–189. * Marion Couthouy Smith, Smith, Marion Couthouy (1921)

"The Rightness of G.K. Chesterton"

''The Catholic World'', Vol. CXIII, No. 678, pp. 163–168. * Stapleton, Julia (2009). ''Christianity, Patriotism, and Nationhood: The England of G.K. Chesterton''. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. * * Joseph de Tonquedec, Tonquédec, Joseph de (1920)

''G.K. Chesterton, ses Idées et son Caractère''

Nouvelle Librairie National. * Maisie Ward, Ward, Maisie (1952). ''Return to Chesterton'', London: Sheed & Ward. * West, Julius (1915)

''G.K. Chesterton: A Critical Study''

London: Martin Secker. *

Works by G.K. Chesterton

at HathiTrust *

What's Wrong: GKC in Periodicals

Articles by G. K. Chesterton in periodicals, with critical annotations. * .

G. K. Chesterton: Quotidiana

G.K. Chesterton research collection

at The Marion E. Wade Center at Wheaton College (Illinois), Wheaton College

G.K. Chesterton Archival Collection

at the University of St. Michael's College at the University of Toronto * {{DEFAULTSORT:Chesterton, Gilbert Keith G. K. Chesterton, 1874 births 1936 deaths 20th-century English novelists 20th-century English poets Alumni of the Slade School of Fine Art Alumni of University College London Aphorists Anti-consumerists Anti-Masonry Anti-imperialism Antisemitism in the United Kingdom British anti-capitalists British anti-communists British male poets British Roman Catholics English World War I poets 20th-century English male writers Burials in Buckinghamshire Christian apologists Christian novelists Christian poets Christian humanists Christian radicals Lay theologians Converts to Roman Catholicism from Anglicanism Critics of classical liberalism Critics of atheism Critics of Marxism English autobiographers English Catholic poets English crime fiction writers English essayists English fantasy writers English male journalists English male novelists English male short story writers English mystery writers English Roman Catholic writers English short story writers Detective fiction writers Knights Commander with Star of the Order of St. Gregory the Great Male essayists Members of the Detection Club Members of the Fabian Society People educated at St Paul's School, London People from Kensington Catholic philosophers English Roman Catholic theologians Simple living advocates Distributism British Zionists

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British mathematician, philosopher, logician, and public intellectual. He had a considerable influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, linguistics, ...

and Clarence Darrow

Clarence Seward Darrow (; April 18, 1857 – March 13, 1938) was an American lawyer who became famous in the early 20th century for his involvement in the Leopold and Loeb murder trial and the Scopes "Monkey" Trial. He was a leading member of t ...

. According to his autobiography, he and Shaw played cowboys in a silent film that was never released. On 7 January 1914 Chesterton (along with his brother Cecil

Cecil may refer to:

People with the name

* Cecil (given name), a given name (including a list of people and fictional characters with the name)

* Cecil (surname), a surname (including a list of people with the name)

Places Canada

*Cecil, Alberta, ...

and future sister-in-law Ada

Ada may refer to:

Places

Africa

* Ada Foah, a town in Ghana

* Ada (Ghana parliament constituency)

* Ada, Osun, a town in Nigeria

Asia

* Ada, Urmia, a village in West Azerbaijan Province, Iran

* Ada, Karaman, a village in Karaman Province, Tur ...

) took part in the mock-trial of John Jasper for the murder of Edwin Drood

''The Mystery of Edwin Drood'' is the final novel by Charles Dickens, originally published in 1870.

Though the novel is named after the character Edwin Drood, it focuses more on Drood's uncle, John Jasper, a precentor, choirmaster and opium ...

. Chesterton was Judge and George Bernard Shaw played the role of foreman of the jury.

Chesterton was a large man, standing tall and weighing around . His girth gave rise to an anecdote during the First World War, when a lady in London asked why he was not "out at the Front

Front may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''The Front'' (1943 film), a 1943 Soviet drama film

* ''The Front'', 1976 film

Music

* The Front (band), an American rock band signed to Columbia Records and active in the 1980s and e ...

"; he replied, "If you go round to the side, you will see that I am." On another occasion he remarked to his friend George Bernard Shaw, "To look at you, anyone would think a famine had struck England." Shaw retorted, "To look at you, anyone would think you had caused it." P. G. Wodehouse

Sir Pelham Grenville Wodehouse, ( ; 15 October 188114 February 1975) was an English author and one of the most widely read humorists of the 20th century. His creations include the feather-brained Bertie Wooster and his sagacious valet, Jeev ...

once described a very loud crash as "a sound like G. K. Chesterton falling onto a sheet of tin". Chesterton usually wore a cape and a crumpled hat, with a swordstick

A swordstick or cane-sword is a cane containing a hidden blade. The term is typically used to describe European weapons from around the 18th century, but similar devices have been used throughout history, notably the Roman ''dolon'', the Japanes ...

in hand, and a cigar hanging out of his mouth. He had a tendency to forget where he was supposed to be going and miss the train that was supposed to take him there. It is reported that on several occasions he sent a telegram to his wife Frances from an incorrect location, writing such things as "Am in Market Harborough

Market Harborough is a market town in the Harborough district of Leicestershire, England, in the far southeast of the county, forming part of the border with Northamptonshire.

Market Harborough's population was 25,143 in 2020. It is the admi ...

. Where ought I to be?" to which she would reply, "Home". Chesterton himself told this story, omitting, however, his wife's alleged reply, in his autobiography.

In 1931, the BBC invited Chesterton to give a series of radio talks. He accepted, tentatively at first. However, from 1932 until his death, Chesterton delivered over 40 talks per year. He was allowed (and encouraged) to improvise on the scripts. This allowed his talks to maintain an intimate character, as did the decision to allow his wife and secretary to sit with him during his broadcasts. The talks were very popular. A BBC official remarked, after Chesterton's death, that "in another year or so, he would have become the dominating voice from Broadcasting House." Chesterton was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, caption =

, awarded_for = Outstanding contributions in literature

, presenter = Swedish Academy

, holder = Annie Ernaux (2022)

, location = Stockholm, Sweden

, year = 1901

, ...

in 1935.

Chesterton was part of the Detection Club

The Detection Club was formed in 1930 by a group of British mystery writers, including Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, Ronald Knox, Freeman Wills Crofts, Arthur Morrison, Hugh Walpole, John Rhode, Jessie Rickard, Baroness Emma Orczy, R. Aus ...

, a society of British mystery authors founded by Anthony Berkeley

Anthony Berkeley Cox (5 July 1893 – 9 March 1971) was an English crime writer. He wrote under several pen-names, including Francis Iles, Anthony Berkeley and A. Monmouth Platts.

Early life and education

Anthony Berkeley Cox was born 5 July ...

in 1928. He was elected as the first president and served from 1930 to 1936 till he was succeeded by E. C. Bentley

Edmund Clerihew Bentley (10 July 1875 – 30 March 1956), who generally published under the names E. C. Bentley or E. Clerihew Bentley, was a popular English novelist and humorist, and inventor of the clerihew, an irregular form of humorous verse ...

.

Death and veneration

Chesterton died of

Chesterton died of congestive heart failure

Heart failure (HF), also known as congestive heart failure (CHF), is a syndrome, a group of signs and symptoms caused by an impairment of the heart's blood pumping function. Symptoms typically include shortness of breath, excessive fatigue, a ...

on 14 June 1936, aged 62, at his home in Beaconsfield

Beaconsfield ( ) is a market town and civil parish within the unitary authority of Buckinghamshire, England, west-northwest of central London and south-southeast of Aylesbury. Three other towns are within : Gerrards Cross, Amersham and High W ...

, Buckinghamshire. His last words were a greeting of good morning spoken to his wife Frances. The sermon at Chesterton's Requiem Mass

A Requiem or Requiem Mass, also known as Mass for the dead ( la, Missa pro defunctis) or Mass of the dead ( la, Missa defunctorum), is a Mass of the Catholic Church offered for the repose of the soul or souls of one or more deceased persons, ...

in Westminster Cathedral

Westminster Cathedral is the mother church of the Catholic Church in England and Wales. It is the largest Catholic church in the UK and the seat of the Archbishop of Westminster.

The site on which the cathedral stands in the City of ...

, London, was delivered by Ronald Knox

Ronald Arbuthnott Knox (17 February 1888 – 24 August 1957) was an Catholic Church in England and Wales, English Catholic priest, Catholic theology, theologian, author, and radio broadcaster. Educated at Eton College, Eton and Balliol Colleg ...

on 27 June 1936. Knox said, "All of this generation has grown up under Chesterton's influence so completely that we do not even know when we are thinking Chesterton." He is buried in Beaconsfield in the Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

Cemetery. Chesterton's estate was probate

Probate is the judicial process whereby a will is "proved" in a court of law and accepted as a valid public document that is the true last testament of the deceased, or whereby the estate is settled according to the laws of intestacy in the sta ...

d at £28,389, .

Near the end of Chesterton's life, Pope Pius XI invested him as Knight Commander with Star of the Papal Order of St. Gregory the Great

The Pontifical Equestrian Order of St. Gregory the Great ( la, Ordo Sancti Gregorii Magni; it, Ordine di San Gregorio Magno) was established on 1 September 1831, by Pope Gregory XVI, seven months after his election as Pope.

The order is one of ...

(KC*SG). The Chesterton Society has proposed that he be beatified

Beatification (from Latin ''beatus'', "blessed" and ''facere'', "to make”) is a recognition accorded by the Catholic Church of a deceased person's entrance into Heaven and capacity to intercede on behalf of individuals who pray in their nam ...

.

Writing

Chesterton wrote around 80 books, several hundred poems, some 200 short stories, 4,000 essays (mostly newspaper columns), and several plays. He was a literary and social critic, historian, playwright, novelist, Catholic theologian andapologist

Apologetics (from Greek , "speaking in defense") is the religious discipline of defending religious doctrines through systematic argumentation and discourse. Early Christian writers (c. 120–220) who defended their beliefs against critics and ...

, debater, and mystery writer. He was a columnist for the ''Daily News'', ''The Illustrated London News

''The Illustrated London News'' appeared first on Saturday 14 May 1842, as the world's first illustrated weekly news magazine. Founded by Herbert Ingram, it appeared weekly until 1971, then less frequently thereafter, and ceased publication in ...

'', and his own paper, ''G. K.'s Weekly

''G.K.'s Weekly'' was a British publication founded in 1925 (with its pilot edition surfacing in late 1924) by writer G. K. Chesterton, continuing until his death in 1936. Its articles typically discussed topical cultural, political, and socio-e ...

''; he also wrote articles for the ''Encyclopædia Britannica

The (Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various time ...

'', including the entry on Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian e ...

and part of the entry on Humour in the 14th edition (1929). His best-known character is the priest-detective Father Brown

Father Brown is a fictional Roman Catholic priest and amateur detective who is featured in 53 short stories published between 1910 and 1936 written by English author G. K. Chesterton. Father Brown solves mysteries and crimes using his intuiti ...

, who appeared only in short stories, while ''The Man Who Was Thursday

''The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare'' is a 1908 novel by G. K. Chesterton. The book has been described as a metaphysical thriller.

Plot summary

Chesterton prefixed the novel with a poem written to Edmund Clerihew Bentley, revisiting the ...

'' is arguably his best-known novel. He was a convinced Christian long before he was received into the Catholic Church, and Christian themes and symbolism appear in much of his writing. In the United States, his writings on distributism

Distributism is an economic theory asserting that the world's productive assets should be widely owned rather than concentrated.

Developed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, distributism was based upon Catholic social teaching prin ...

were popularised through '' The American Review'', published by Seward Collins

Seward Bishop Collins (April 22, 1899 – December 8, 1952) was an American New York socialite and publisher. By the end of the 1920s, he was a self-described " fascist".

Biography

Collins was born in Syracuse, New York to Irish Catholic par ...

in New York.

Of his nonfiction, ''Charles Dickens: A Critical Study'' (1906) has received some of the broadest-based praise. According to Ian Ker

Ian Turnbull Ker (30 August 1942 – 5 November 2022) was an English Roman Catholic priest, a former Anglican and a scholar and author. He was generally regarded as the world's authority on John Henry Newman, on whom he published more than 20 book ...

(''The Catholic Revival in English Literature, 1845–1961'', 2003), "In Chesterton's eyes Dickens belongs to Merry

Merry may refer to:

A happy person with a jolly personality People

* Merry (given name)

* Merry (surname)

Music

* Merry (band), a Japanese rock band

* ''Merry'' (EP), an EP by Gregory Douglass

* "Merry" (song), by American power pop band Magna ...

, not Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

, England"; Ker treats Chesterton's thought in chapter 4 of that book as largely growing out of his true appreciation of Dickens, a somewhat shop-soiled property in the view of other literary opinions of the time. The biography was largely responsible for creating a popular revival for Dickens's work as well as a serious reconsideration of Dickens by scholars.

Chesterton's writings consistently displayed wit and a sense of humour. He employed paradox, while making serious comments on the world, government, politics, economics, philosophy, theology and many other topics.

T.S. Eliot

Thomas Stearns Eliot (26 September 18884 January 1965) was a poet, essayist, publisher, playwright, literary critic and editor.Bush, Ronald. "T. S. Eliot's Life and Career", in John A Garraty and Mark C. Carnes (eds), ''American National B ...

summed up his work as follows:

Eliot commented further that "His poetry was first-rate journalistic balladry, and I do not suppose that he took it more seriously than it deserved. He reached a high imaginative level with ''The Napoleon of Notting Hill

''The Napoleon of Notting Hill'' is a novel written by G. K. Chesterton in 1904, set in a nearly unchanged London in 1984.

Although the novel is set in the future, it is, in effect, set in an alternative reality of Chesterton's own period, wit ...

'', and higher with ''The Man Who Was Thursday

''The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare'' is a 1908 novel by G. K. Chesterton. The book has been described as a metaphysical thriller.

Plot summary

Chesterton prefixed the novel with a poem written to Edmund Clerihew Bentley, revisiting the ...

'', romances in which he turned the Stevensonian fantasy to more serious purpose. His book on Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian er ...

seems to me the best essay on that author that has ever been written. Some of his essays can be read again and again; though of his essay-writing as a whole, one can only say that it is remarkable to have maintained such a high average with so large an output."

Views and contemporaries

Wilde and Shaw

In his book ''Heretics

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

'', Chesterton said this of Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular playwrights in London in the early 1890s. He is ...

: "The same lesson f the pessimistic pleasure-seeker

F, or f, is the sixth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''ef'' (pronounced ), and the plural is ''efs''.

Hist ...

was taught by the very powerful and very desolate philosophy of Oscar Wilde. It is the carpe diem

is a Latin aphorism, usually translated "seize the day", taken from book 1 of the Roman poet Horace's work ''Odes'' (23 BC).

Translation

is the second-person singular present active imperative of '' carpō'' "pick or pluck" used by Horace t ...

religion; but the carpe diem religion is not the religion of happy people, but of very unhappy people. Great joy does not gather the rosebuds while it may; its eyes are fixed on the immortal rose which Dante saw." More briefly, and with a closer approximation to Wilde's own style, he wrote in his 1908 book ''Orthodoxy

Orthodoxy (from Greek: ) is adherence to correct or accepted creeds, especially in religion.

Orthodoxy within Christianity refers to acceptance of the doctrines defined by various creeds and ecumenical councils in Antiquity, but different Churc ...

'' concerning the necessity of making symbolic sacrifices for the gift of creation: "Oscar Wilde said that sunsets were not valued because we could not pay for sunsets. But Oscar Wilde was wrong; we can pay for sunsets. We can pay for them by not being Oscar Wilde."

Chesterton and George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

were famous friends and enjoyed their arguments and discussions. Although rarely in agreement, they each maintained good will toward, and respect for, the other. In his writing, Chesterton expressed himself very plainly on where they differed and why. In ''Heretics'' he writes of Shaw:

Shaw represented the new school of thought, modernism

Modernism is both a philosophy, philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western world, Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new fo ...

, which was rising at the time. Chesterton's views, on the other hand, became increasingly focused towards the Church. In ''Orthodoxy'' he wrote: "The worship of will is the negation of will ..If Mr Bernard Shaw comes up to me and says, 'Will something', that is tantamount to saying, 'I do not mind what you will', and that is tantamount to saying, 'I have no will in the matter.' You cannot admire will in general, because the essence of will is that it is particular."

This style of argument is what Chesterton refers to as using 'Uncommon Sense' – that is, that the thinkers and popular philosophers of the day, though very clever, were saying things that were nonsensical. This is illustrated again in ''Orthodoxy'': "Thus when Mr H. G. Wells says (as he did somewhere), 'All chairs are quite different', he utters not merely a misstatement, but a contradiction in terms. If all chairs were quite different, you could not call them 'all chairs'." Or, again from ''Orthodoxy'':

Chesterton, as a political thinker, cast aspersions on both progressivism

Progressivism holds that it is possible to improve human societies through political action. As a political movement, progressivism seeks to advance the human condition through social reform based on purported advancements in science, tec ...

and conservatism

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilizati ...

, saying, "The whole modern world has divided itself into Conservatives and Progressives. The business of Progressives is to go on making mistakes. The business of the Conservatives is to prevent the mistakes from being corrected." He was an early member of the Fabian Society

The Fabian Society is a British socialist organisation whose purpose is to advance the principles of social democracy and democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist effort in democracies, rather than by revolutionary overthrow. The Fa ...

, but resigned at the time of the Boer War.

The author James Parker, in ''The Atlantic

''The Atlantic'' is an American magazine and multi-platform publisher. It features articles in the fields of politics, foreign affairs, business and the economy, culture and the arts, technology, and science.

It was founded in 1857 in Boston, ...

'', gave a modern appraisal:

Advocacy of Catholicism

Chesterton's ''The Everlasting Man

''The Everlasting Man'' is a Christian apologetics book written by G. K. Chesterton, published in 1925. It is, to some extent, a deliberate rebuttal of H. G. Wells' ''The Outline of History'', disputing Wells' portrayals of human life and civi ...

'' contributed to C. S. Lewis

Clive Staples Lewis (29 November 1898 – 22 November 1963) was a British writer and Anglican lay theologian. He held academic positions in English literature at both Oxford University (Magdalen College, 1925–1954) and Cambridge Univers ...

's conversion to Christianity. In a letter to Sheldon Vanauken

Sheldon Vanauken (August 4, 1914 – October 18, 1996) was an American author, best known for his autobiographical book ''A Severe Mercy'' (1977), which recounts his and his wife's friendship with C. S. Lewis, their conversion to Christianity ...

(14 December 1950), Lewis called the book "the best popular apologetic I know", and to Rhonda Bodle he wrote (31 December 1947) "the ery

Yeru or Eru (Ы ы; italics: ''Ы'' ''ы''), usually called Y in modern Russian language, Russian or Yery or Ery historically and in modern Church Slavonic, is a letter in the Cyrillic script. It represents the close central unrounded ...

best popular defence of the full Christian position I know is G. K. Chesterton's ''The Everlasting Man''". The book was also cited in a list of 10 books that "most shaped his vocational attitude and philosophy of life".

Chesterton's hymn "O God of Earth and Altar" was printed in ''The Commonwealth

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the ...

'' and then included in the ''English Hymnal

''The English Hymnal'' is a hymn book which was published in 1906 for the Church of England by Oxford University Press. It was edited by the clergyman and writer Percy Dearmer and the composer and music historian Ralph Vaughan Williams, and was ...

'' in 1906. Several lines of the hymn appear in the beginning of the song "Revelations" by the British heavy metal band Iron Maiden

Iron Maiden are an English heavy metal band formed in Leyton, East London, in 1975 by bassist and primary songwriter Steve Harris. While fluid in the early years of the band, the lineup for most of the band's history has consisted of Harri ...

on their 1983 album ''Piece of Mind

''Piece of Mind'' is the fourth studio album by English heavy metal band Iron Maiden. It was released on 16 May 1983 in the United Kingdom by EMI Records and in the United States by Capitol Records. It was the first album to feature drummer Ni ...

''. Lead singer Bruce Dickinson

Paul Bruce Dickinson (born 7 August 1958) is an English singer who has been the lead vocalist of the heavy metal band Iron Maiden from 1981 to 1993 and 1999–present. He is known for his wide-ranging operatic vocal style and energetic stage ...

in an interview stated "I have a fondness for hymns. I love some of the ritual, the beautiful words, ''Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

'' and there was another one, with words by G.K. Chesterton ''O God of Earth and Altar'' – very fire and brimstone: 'Bow down and hear our cry'. I used that for an Iron Maiden song, "Revelations". In my strange and clumsy way I was trying to say look it's all the same stuff."

Étienne Gilson

Étienne Henri Gilson (; 13 June 1884 – 19 September 1978) was a French philosopher and historian of philosophy. A scholar of medieval philosophy, he originally specialised in the thought of Descartes; he also philosophized in the tradition o ...

praised Chesterton's book on St Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known wit ...

: "I consider it as being, without possible comparison, the best book ever written on Saint Thomas ..the few readers who have spent twenty or thirty years in studying St. Thomas Aquinas, and who, perhaps, have themselves published two or three volumes on the subject, cannot fail to perceive that the so-called 'wit' of Chesterton has put their scholarship to shame."

Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen

Fulton John Sheen (born Peter John Sheen, May 8, 1895 – December 9, 1979) was an American bishop of the Catholic Church known for his preaching and especially his work on television and radio. Ordained a priest of the Diocese of Peoria in ...

, the author of 70 books, identified Chesterton as the stylist who had the greatest impact on his own writing, stating in his autobiography ''Treasure in Clay'', "the greatest influence in writing was G. K. Chesterton who never used a useless word, who saw the value of a paradox, and avoided what was trite." Chesterton wrote the introduction to Sheen's book ''God and Intelligence in Modern Philosophy; A Critical Study in the Light of the Philosophy of Saint Thomas''.

Charges of antisemitism

Chesterton faced accusations ofantisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

during his lifetime, saying in his 1920 book '' The New Jerusalem'' that it was something "for which my friends and I were for a long period rebuked and even reviled". Despite his protestations to the contrary, the accusation continues to be repeated. An early supporter of Captain Dreyfus

Alfred Dreyfus ( , also , ; 9 October 1859 – 12 July 1935) was a French artillery officer of Jewish ancestry whose trial and conviction in 1894 on charges of treason became one of the most polarizing political dramas in modern French history. ...

, by 1906 he had turned into an anti-dreyfusard

The Dreyfus affair (french: affaire Dreyfus, ) was a political scandal that divided the French Third Republic from 1894 until its resolution in 1906. "L'Affaire", as it is known in French, has come to symbolise modern injustice in the Francop ...

. From the early 20th century, his fictional work included caricatures of Jews, stereotyping them as greedy, cowardly, disloyal and communists. Martin Gardner

Martin Gardner (October 21, 1914May 22, 2010) was an American popular mathematics and popular science writer with interests also encompassing scientific skepticism, micromagic, philosophy, religion, and literatureespecially the writings of Lewis ...

suggests that ''Four Faultless Felons'' was allowed to go out of print in the United States because of the "anti-Semitism which mars so many pages."

The Marconi scandal

The Marconi scandal was a British political scandal that broke in mid-1912. Allegations were made that highly placed members of the Liberal government under the Prime Minister H. H. Asquith had profited by improper use of information about the gove ...

of 1912–13 brought issues of anti-Semitism into the political mainstream. Senior ministers in the Liberal government had secretly profited from advance knowledge of deals regarding wireless telegraphy, and critics regarded it as relevant that some of the key players were Jewish. According to historian Todd Endelman, who identified Chesterton as among the most vocal critics, "The Jew-baiting at the time of the Boer War and the Marconi scandal was linked to a broader protest, mounted in the main by the Radical wing of the Liberal Party, against the growing visibility of successful businessmen in national life and their challenge to what were seen as traditional English values."

In a work of 1917, titled ''A Short History of England'', Chesterton considers the royal decree of 1290 by which Edward I expelled Jews from England, a policy that remained in place until 1655. Chesterton writes that popular perception of Jewish moneylenders could well have led Edward I's subjects to regard him as a "tender father of his people" for "breaking the rule by which the rulers had hitherto fostered their bankers' wealth". He felt that Jews, "a sensitive and highly civilized people" who "were the capitalists of the age, the men with wealth banked ready for use", might legitimately complain that "Christian kings and nobles, and even Christian popes and bishops, used for Christian purposes (such as the Crusades and the cathedrals) the money that could only be accumulated in such mountains by a usury they inconsistently denounced as unchristian; and then, when worse times came, gave up the Jew to the fury of the poor".

In ''The New Jerusalem'' Chesterton dedicated a chapter to his views on the Jewish question

The Jewish question, also referred to as the Jewish problem, was a wide-ranging debate in 19th- and 20th-century European society that pertained to the appropriate status and treatment of Jews. The debate, which was similar to other "national ...

: the sense that Jews were a distinct people without a homeland of their own, living as foreigners in countries where they were always a minority. He wrote that in the past, his position:

In the same place he proposed the thought experiment (describing it as "a parable" and "a flippant fancy") that Jews should be admitted to any role in English public life on condition that they must wear distinctively Middle Eastern garb, explaining that "The point is that we should know where we are; and he would know where he is, which is in a foreign land."

Chesterton, like Belloc, openly expressed his abhorrence of Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and then ...

's rule almost as soon as it started. As Rabbi Stephen Wise

Stephen Samuel Wise (March 17, 1874 – April 19, 1949) was an early 20th-century American Reform Judaism, Reform rabbi and Zionism, Zionist leader in the Progressive Era. Born in Budapest, he was an infant when his family immigrated to New Yor ...

wrote in a posthumous tribute to Chesterton in 1937:

In ''The Truth about the Tribes'' Chesterton blasted German race theories, writing: "the essence of Nazi Nationalism is to preserve the purity of a race in a continent where all races are impure."

The historian Simon Mayers points out that Chesterton wrote in works such as ''The Crank'', ''The Heresy of Race'', and ''The Barbarian as Bore'' against the concept of racial superiority and critiqued pseudo-scientific race theories, saying they were akin to a new religion. In ''The Truth About the Tribes'' Chesterton wrote, "the curse of race religion is that it makes each separate man the sacred image which he worships. His own bones are the sacred relics; his own blood is the blood of St. Januarius." Mayers records that despite "his hostility towards Nazi antisemitism … t is unfortunate that he made

T, or t, is the twentieth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''tee'' (pronounced ), plural ''tees''. It is deri ...

claims that 'Hitlerism' was a form of Judaism, and that the Jews were partly responsible for race theory." In ''The Judaism of Hitler'', as well as in ''A Queer Choice'' and ''The Crank'', Chesterton made much of the fact that the very notion of "a Chosen Race" was of Jewish origin, saying in ''The Crank'': "If there is one outstanding quality in Hitlerism it is its Hebraism" and "the new Nordic Man has all the worst faults of the worst Jews: jealousy, greed, the mania of conspiracy, and above all, the belief in a Chosen Race."

Mayers also shows that Chesterton portrayed Jews not only as culturally and religiously distinct, but racially as well. In ''The Feud of the Foreigner'' (1920) he said that the Jew "is a foreigner far more remote from us than is a Bavarian from a Frenchman; he is divided by the same type of division as that between us and a Chinaman or a Hindoo. He not only is not, but never was, of the same race."

In ''The Everlasting Man'', while writing about human sacrifice, Chesterton suggested that medieval stories about Jews killing children might have resulted from a distortion of genuine cases of devil-worship. Chesterton wrote:

The American Chesterton Society has devoted a whole issue of its magazine, ''Gilbert'', to defending Chesterton against charges of antisemitism. Likewise, Ann Farmer, author of ''Chesterton and the Jews: Friend, Critic, Defender'', writes, "Public figures from Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

to Wells

Wells most commonly refers to:

* Wells, Somerset, a cathedral city in Somerset, England

* Well, an excavation or structure created in the ground

* Wells (name)

Wells may also refer to:

Places Canada

*Wells, British Columbia

England

* Wells ...

proposed remedies for the 'Jewish problem

The Jewish question, also referred to as the Jewish problem, was a wide-ranging debate in 19th- and 20th-century European society that pertained to the appropriate status and treatment of Jews. The debate, which was similar to other "national ...

' – the seemingly endless cycle of anti-Jewish persecution – all shaped by their worldviews. As patriots, Churchill and Chesterton embraced Zionism; both were among the first to defend the Jews from Nazism," concluding that "A defender of Jews in his youth – a conciliator as well as a defender – GKC returned to the defence when the Jewish people needed it most."

Opposition to eugenics

In ''Eugenics and Other Evils'', Chesterton attackedeugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or ...

as Parliament was moving towards passage of the Mental Deficiency Act 1913

The Mental Deficiency Act 1913 was an act of Parliament of the United Kingdom creating provisions for the institutional treatment of people deemed to be "feeble-minded" and "moral defectives". "It proposed an institutional separation so that menta ...

. Some backing the ideas of eugenics called for the government to sterilise people deemed "mentally defective"; this view did not gain popularity but the idea of segregating them from the rest of society and thereby preventing them from reproducing did gain traction. These ideas disgusted Chesterton who wrote, "It is not only openly said, it is eagerly urged that the aim of the measure is to prevent any person whom these propagandists do not happen to think intelligent from having any wife or children." He blasted the proposed wording for such measures as being so vague as to apply to anyone, including "Every tramp who is sulk, every labourer who is shy, every rustic who is eccentric, can quite easily be brought under such conditions as were designed for homicidal maniacs. That is the situation; and that is the point ..we are already under the Eugenist State; and nothing remains to us but rebellion." He derided such ideas as founded on nonsense, "as if one had a right to dragoon and enslave one's fellow citizens as a kind of chemical experiment". Chesterton mocked the idea that poverty was a result of bad breeding: "t is a

T, or t, is the twentieth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''tee'' (pronounced ), plural ''tees''. It is deri ...

strange new disposition to regard the poor as a race; as if they were a colony of Japs or Chinese coolies ..The poor are not a race or even a type. It is senseless to talk about breeding them; for they are not a breed. They are, in cold fact, what Dickens describes: 'a dustbin of individual accidents,' of damaged dignity, and often of damaged gentility."

Chesterton's fence

'Chesterton's fence' is the principle that reforms should not be made until the reasoning behind the existing state of affairs is understood. The quotation is from Chesterton's 1929 book, ''The Thing: Why I Am a Catholic'', in the chapter, "The Drift from Domesticity":"Chesterbelloc"

Chesterton is often associated with his close friend, the poet and essayist

Chesterton is often associated with his close friend, the poet and essayist Hilaire Belloc

Joseph Hilaire Pierre René Belloc (, ; 27 July 187016 July 1953) was a Franco-English writer and historian of the early twentieth century. Belloc was also an orator, poet, sailor, satirist, writer of letters, soldier, and political activist. H ...

. George Bernard Shaw coined the name "Chesterbelloc" for their partnership, and this stuck. Though they were very different men, they shared many beliefs; in 1922, Chesterton joined Belloc in the Catholic faith, and both voiced criticisms of capitalism and socialism. They instead espoused a third way: distributism

Distributism is an economic theory asserting that the world's productive assets should be widely owned rather than concentrated.

Developed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, distributism was based upon Catholic social teaching prin ...

. '' G. K.'s Weekly'', which occupied much of Chesterton's energy in the last 15 years of his life, was the successor to Belloc's ''New Witness

''G.K.'s Weekly'' was a British publication founded in 1925 (with its pilot edition surfacing in late 1924) by writer G. K. Chesterton, continuing until his death in 1936. Its articles typically discussed topical cultural, political, and socio-e ...

'', taken over from Cecil Chesterton

Cecil Edward Chesterton (12 November 1879 – 6 December 1918) was an English journalist and political commentator, known particularly for his role as editor of '' The New Witness'' from 1912 to 1916, and in relation to its coverage of the Marco ...

, Gilbert's brother, who died in World War I.

In his book ''On the Place of Gilbert Chesterton in English Letters'', Belloc wrote that "Everything he wrote upon any one of the great English literary names was of the first quality. He summed up any one pen (that of Jane Austen

Jane Austen (; 16 December 1775 – 18 July 1817) was an English novelist known primarily for her six major novels, which interpret, critique, and comment upon the British landed gentry at the end of the 18th century. Austen's plots of ...

, for instance) in exact sentences; sometimes in a single sentence, after a fashion which no one else has approached. He stood quite by himself in this department. He understood the very minds (to take the two most famous names) of Thackeray

William Makepeace Thackeray (; 18 July 1811 – 24 December 1863) was a British novelist, author and illustrator. He is known for his satirical works, particularly his 1848 novel '' Vanity Fair'', a panoramic portrait of British society, and t ...

and of Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian er ...

. He understood and presented Meredith. He understood the supremacy in Milton

Milton may refer to:

Names

* Milton (surname), a surname (and list of people with that surname)

** John Milton (1608–1674), English poet

* Milton (given name)

** Milton Friedman (1912–2006), Nobel laureate in Economics, author of '' Free t ...

. He understood Pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

. He understood the great Dryden

''

John Dryden (; – ) was an English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who in 1668 was appointed England's first Poet Laureate.

He is seen as dominating the literary life of Restoration England to such a point that the peri ...

. He was not swamped as nearly all his contemporaries were by Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

, wherein they drown as in a vast sea – for that is what Shakespeare is. Gilbert Chesterton continued to understand the youngest and latest comers as he understood the forefathers in our great corpus of English verse and prose."

Legacy

Literary

Chesterton's socio-economic system of Distributism affected the sculptorEric Gill

Arthur Eric Rowton Gill, (22 February 1882 – 17 November 1940) was an English sculptor, letter cutter, typeface designer, and printmaker. Although the ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' describes Gill as ″the greatest artist-cra ...

, who established a commune of Catholic artists at Ditchling

Ditchling is a village and civil parish in the Lewes District of East Sussex, England. The village is contained within the boundaries of the South Downs National Park; the order confirming the establishment of the park was signed in Ditchling.

...

in Sussex. The Ditchling group developed a journal called ''The Game'', in which they expressed many Chestertonian principles, particularly anti-industrialism and an advocacy of religious family life. His novel ''The Man Who Was Thursday

''The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare'' is a 1908 novel by G. K. Chesterton. The book has been described as a metaphysical thriller.

Plot summary

Chesterton prefixed the novel with a poem written to Edmund Clerihew Bentley, revisiting the ...

'' inspired the Irish Republican leader Michael Collins Michael Collins or Mike Collins most commonly refers to:

* Michael Collins (Irish leader) (1890–1922), Irish revolutionary leader, soldier, and politician

* Michael Collins (astronaut) (1930–2021), American astronaut, member of Apollo 11 and Ge ...

with the idea that "If you didn't seem to be hiding nobody hunted you out." Collins's favourite work of Chesterton was ''The Napoleon of Notting Hill

''The Napoleon of Notting Hill'' is a novel written by G. K. Chesterton in 1904, set in a nearly unchanged London in 1984.

Although the novel is set in the future, it is, in effect, set in an alternative reality of Chesterton's own period, wit ...

'', and he was "almost fanatically attached to it", according to his friend Sir William Darling. His column

A column or pillar in architecture and structural engineering is a structural element that transmits, through compression, the weight of the structure above to other structural elements below. In other words, a column is a compression member. ...

in the ''Illustrated London News

''The Illustrated London News'' appeared first on Saturday 14 May 1842, as the world's first illustrated weekly news magazine. Founded by Herbert Ingram, it appeared weekly until 1971, then less frequently thereafter, and ceased publication in ...

'' on 18 September 1909 had a profound effect on Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

. P. N. Furbank

Philip Nicholas Furbank FRSL (; 23 May 1920 – 27 June 2014) was an English biographer, critic and academic. His most significant biography was the well-received life of his friend E. M. Forster.

Career

After Reigate Grammar School, Furbank e ...

asserts that Gandhi was "thunderstruck" when he read it, while Martin Green notes that "Gandhi was so delighted with this that he told ''Indian Opinion

The ''Indian Opinion'' was a newspaper established by Indian lawyer and future anti-colonial activist M. K. Gandhi (later known as the Mahatma). The publication was an important tool for the political movement led by Gandhi and the Natal Indian ...

'' to reprint it." Another convert was Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan

Herbert Marshall McLuhan (July 21, 1911 – December 31, 1980) was a Canadian philosopher whose work is among the cornerstones of the study of media theory. He studied at the University of Manitoba and the University of Cambridge. He began his ...

, who said that the book ''What's Wrong with the World'' changed his life in terms of ideas and religion. The author Neil Gaiman

Neil Richard MacKinnon GaimanBorn as Neil Richard Gaiman, with "MacKinnon" added on the occasion of his marriage to Amanda Palmer. ; ( Neil Richard Gaiman; born 10 November 1960) is an English author of short fiction, novels, comic books, gr ...

stated that he grew up reading Chesterton in his school's library, and that ''The Napoleon of Notting Hill'' influenced his own book ''Neverwhere

''Neverwhere'' is an urban fantasy television miniseries by Neil Gaiman that first aired in 1996 on BBC 2. The series is set in "London Below", a magical realm coexisting with the more familiar London, referred to as "London Above". It was dev ...

''. Gaiman based the character Gilbert Gilbert may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Gilbert (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

*Gilbert (surname), including a list of people

Places Australia

* Gilbert River (Queensland)

* Gilbert River (South ...

from the comic book ''The Sandman

The Sandman is a mythical character in European folklore who puts people to sleep and encourages and inspires beautiful dreams by sprinkling magical sand onto their eyes.

Representation in traditional folklore

The Sandman is a traditional charact ...

'' on Chesterton, while the novel

A novel is a relatively long work of narrative fiction, typically written in prose and published as a book. The present English word for a long work of prose fiction derives from the for "new", "news", or "short story of something new", itsel ...

he co-wrote with Terry Pratchett

Sir Terence David John Pratchett (28 April 1948 – 12 March 2015) was an English humourist, satirist, and author of fantasy novels, especially comical works. He is best known for his ''Discworld'' series of 41 novels.

Pratchett's first nov ...

is dedicated to him. The Argentine author and essayist Jorge Luis Borges

Jorge Francisco Isidoro Luis Borges Acevedo (; ; 24 August 1899 – 14 June 1986) was an Argentine short-story writer, essayist, poet and translator, as well as a key figure in Spanish-language and international literature. His best-known bo ...

cited Chesterton as influential on his fiction, telling interviewer Richard Burgin that "Chesterton knew how to make the most of a detective story."

Education

Chesterton's many references to education and human formation have inspired a variety of educators including the 44 schools of the Chesterton Schools Network (which includes theChesterton Academy

Chesterton Academy is a private, co-ed, Catholic secondary school in Hopkins, Minnesota, United States. It is located in the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis.

Launched in the fall of 2008 by Dale Ahlquist and Tom Bengts ...

founded by Dale Ahlquist

Dale Ahlquist (born June 14, 1958) is an American author and advocate of the thought of G. K. Chesterton. Ahlquist is the president and co-founder of the American Chesterton Society and the publisher of its magazine, ''Gilbert''. He is also th ...

. Pulisher and educator Christopher Perrin

Christopher Perrin (born 1961) is a publisher, educator, speaker, and writer. He is the CEO and cofounder of Classical Academic Press (a classical education curriculum, media, and consulting company started in 2001) and speaks regularly at schoo ...

(who completed his doctoral work on Chesterton) makes frequent reference to Chesterton in his work with classical schools.

Namesakes

In 1974,Father Ian Boyd

Ian Boyd is Distinguished Professor of Catholic Studies at Seton Hall University, founder and editor of ''The Chesterton Review'', and president of the G.K. Chesterton Institute for Faith & Culture. A renowned scholar of G. K. Chesterton, he is ...

, C.S.B, founded ''The Chesterton Review

''The Chesterton Review'' is the peer-reviewed academic journal of the G. K. Chesterton Institute for Faith & Culture (Seton Hall University). It was established in 1974 to promote an interest in all aspects of G. K. Chesterton's life, work, art, a ...

'', a scholarly journal devoted to Chesterton and his circle. The journal is published by the G.K. Chesterton Institute for Faith and Culture based in Seton Hall University, South Orange, New Jersey.

In 1996, Dale Ahlquist

Dale Ahlquist (born June 14, 1958) is an American author and advocate of the thought of G. K. Chesterton. Ahlquist is the president and co-founder of the American Chesterton Society and the publisher of its magazine, ''Gilbert''. He is also th ...

founded the American Chesterton Society to explore and promote his writings.

In 2008, a Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

high school, Chesterton Academy

Chesterton Academy is a private, co-ed, Catholic secondary school in Hopkins, Minnesota, United States. It is located in the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis.

Launched in the fall of 2008 by Dale Ahlquist and Tom Bengts ...

, opened in the Minneapolis

Minneapolis () is the largest city in Minnesota, United States, and the county seat of Hennepin County. The city is abundant in water, with thirteen lakes, wetlands, the Mississippi River, creeks and waterfalls. Minneapolis has its origins ...

area. In the same year Scuola Libera Chesterton opened in San Benedetto del Tronto

San Benedetto del Tronto is a city and ''comune'' in Marche, Italy. Part of an urban area with 100,000 inhabitants, it is one of the most densely populated areas along the Adriatic Sea coast. It is the most populated city in Province of Ascoli P ...

, Italy.

In 2012, a crater on the planet Mercury

Mercury commonly refers to:

* Mercury (planet), the nearest planet to the Sun

* Mercury (element), a metallic chemical element with the symbol Hg

* Mercury (mythology), a Roman god

Mercury or The Mercury may also refer to:

Companies

* Merc ...

was named Chesterton after the author.

In 2014, G.K. Chesterton Academy of Chicago, a Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

high school, opened in Highland Park, Illinois

Highland Park is a suburban city located in the southeastern part of Lake County, Illinois, United States, about north of downtown Chicago. Per the 2020 census, the population was 30,176. Highland Park is one of several municipalities located o ...

.

A fictionalised G. K. Chesterton is the central character in the ''Young Chesterton Chronicles'', a series of young adult

A young adult is generally a person in the years following adolescence. Definitions and opinions on what qualifies as a young adult vary, with works such as Erik Erikson's stages of human development significantly influencing the definition of ...

adventure novels by John McNichol, and in the ''G K Chesterton Mystery series'', a series of detective novels by Australian Kel Richards

Kelvin Barry "Kel" Richards (born 8 February 1946) is an Australian author, journalist, radio personality and lay Christian.

Richards has written a series of crime novels and thrillers for adult readers which includes ''The Case of the Vanishi ...

.

Major works

Books

* * * * * * * * * * (detective fiction) * * * * * * * * * *Short stories

"The Trees of Pride"

1922 * "The Crime of the Communist", ''Collier's Weekly'', July 1934. * "The Three Horsemen", ''Collier's Weekly'', April 1935. * "The Ring of the Lovers", ''Collier's Weekly'', April 1935. * "A Tall Story", ''Collier's Weekly'', April 1935. * "The Angry Street – A Bad Dream", ''Famous Fantastic Mysteries'', February 1947.

Plays

* ''Magic

Magic or Magick most commonly refers to:

* Magic (supernatural), beliefs and actions employed to influence supernatural beings and forces

* Ceremonial magic, encompasses a wide variety of rituals of magic

* Magical thinking, the belief that unrela ...

'', 1913.

References

Citations

Sources

Cited biographies * *Further reading

* * * Belmonte, Kevin (2011). ''Defiant Joy: The Remarkable Life and Impact of G.K. Chesterton''. Nashville, Tenn.: Thomas Nelson. * Blackstock, Alan R. (2012). ''The Rhetoric of Redemption: Chesterton, Ethical Criticism, and the Common Man''. New York. Peter Lang Publishing. * Braybrooke, Patrick (1922)''Gilbert Keith Chesterton''

London: Chelsea Publishing Company. * Cammaerts, Émile (1937). ''The Laughing Prophet: The Seven Virtues And G. K. Chesterton''. London: Methuen & Co., Ltd. * Campbell, W. E. (1908)

"G.K. Chesterton: Inquisitor and Democrat"

''The Catholic World'', Vol. LXXXVIII, pp. 769–782. * Campbell, W. E. (1909)

"G.K. Chesterton: Catholic Apologist"

''The Catholic World'', Vol. LXXXIX, No. 529, pp. 1–12. * Chesterton, Cecil (1908)

''G.K. Chesterton: A Criticism''

London: Alston Rivers (Rep. b

John Lane Company

1909). * Clipper, Lawrence J. (1974). ''G.K. Chesterton''. New York: Twayne Publishers. * Coates, John (1984). ''Chesterton and the Edwardian Cultural Crisis''. Hull University Press. * Coates, John (2002). ''G.K. Chesterton as Controversialist, Essayist, Novelist, and Critic''.

Lewiston, New York

Lewiston is a town in Niagara County, New York, United States. The population was 15,944 at the 2020 census. The town and its contained village are named after Morgan Lewis, a governor of New York.

The Town of Lewiston is on the western bord ...

: Edwin Mellen Press

The Edwin Mellen Press or Mellen Press is an international Independent business, independent company and Academic publisher, academic publishing house with editorial offices in Lewiston (town), New York, Lewiston, New York, and Lampeter, Lampete ...

.

* Conlon, D. J. (1987). ''G.K. Chesterton: A Half Century of Views''. Oxford University Press.

*

*

* Corrin, Jay P. (1981). ''G.K. Chesterton & Hilaire Belloc: The Battle Against Modernity''. Ohio University Press.

* Ervine, St. John G. (1922)"G.K. Chesterton"

In: ''Some Impressions of my Elders''. New York: The Macmillan Company, pp. 90–112. * * ''Gilbert Magazine'' (November/December 2008). Vol. 12, No. 2-3, ''Special Issue: Chesterton & The Jews''. * Haldane, John. 'Chesterton's Philosophy of Education', philosophy, Vol. 65, No. 251 (Jan. 1990), pp. 65–80. *

Hitchens, Christopher

Christopher Eric Hitchens (13 April 1949 – 15 December 2011) was a British-American author and journalist who wrote or edited over 30 books (including five essay collections) on culture, politics, and literature. Born and educated in England, ...

(2012)"The Reactionary"

''The Atlantic''. * Herts, B. Russell (1914)

"Gilbert K. Chesterton: Defender of the Discarded"

In: ''Depreciations''. New York: Albert & Charles Boni, pp. 65–86. * Hollis, Christopher (1970). ''The Mind of Chesterton''. London: Hollis & Carter. * Hunter, Lynette (1979). ''G.K. Chesterton: Explorations in Allegory''. London: Macmillan Press. * Jaki, Stanley (1986). ''Chesterton: A Seer of Science''. University of Illinois Press. * Jaki, Stanley (1986). "Chesterton's Landmark Year". In: ''Chance or Reality and Other Essays''. University Press of America. * Kenner, Hugh (1947). ''Paradox in Chesterton''. New York: Sheed & Ward. * Roger Kimball, Kimball, Roger (2011)

"G. K. Chesterton: Master of Rejuvenation"