Giedroyc-Mieroszewski Doctrine on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Giedroyc doctrine (; pl, doktryna Giedroycia) or Giedroyc–Mieroszewski doctrine was a

The Giedroyc doctrine (; pl, doktryna Giedroycia) or Giedroyc–Mieroszewski doctrine was a

Lithuanian – Polish Relations Reconsidered: A Constrained Bilateral Agenda or an Empty Strategic Partnership?

' pp. 126–27 online, direct PDF download.) and other émigrés of the "

Słownik Polityki Wschodniej

Polityka Wschodnia, 2011 The doctrine can be traced to the interwar Prometheist project of

„''Jeśli nie ULB, to co? Doktryna Giedroycia w XXI w.''”

("If Not ULB, Then What? The Giedroyc Doctrine in the 21st Century", 17 June 2010) *Bartłomiej Sienkiewicz

("Farewell to Giedroyc", ''Rzeczpospolita'', 28-05-2010). *

"'Doktryna ULB – koncepcja Giedroycia i Mieroszewskiego w XXI wieku''"

("The ULB Doctrine: Giedroyc's and Mieroszewski's Concept in the 21st century")

*Marcin Wojciechowski

"''Co po Giedroyciu? Giedroyc!''"

("What Comes after Giedroyc? Giedroyc!"), ''Nowa Europa Wschodnia'' (New Eastern Europe), 1/2010, pp. 69–77. Foreign relations of Poland Polish People's Republic History of Poland (1989–present) Political history of Poland Foreign policy doctrines Aftermath of World War II in Poland

The Giedroyc doctrine (; pl, doktryna Giedroycia) or Giedroyc–Mieroszewski doctrine was a

The Giedroyc doctrine (; pl, doktryna Giedroycia) or Giedroyc–Mieroszewski doctrine was a political doctrine

Doctrine (from la, doctrina, meaning "teaching, instruction") is a codification of beliefs or a body of teachings or instructions, taught principles or positions, as the essence of teachings in a given branch of knowledge or in a belief system ...

that urged reconciliation among Central and Eastern European countries. It was developed by postwar Polish émigré

An ''émigré'' () is a person who has emigrated, often with a connotation of political or social self-exile. The word is the past participle of the French ''émigrer'', "to emigrate".

French Huguenots

Many French Huguenots fled France followin ...

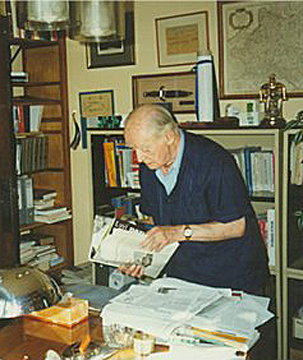

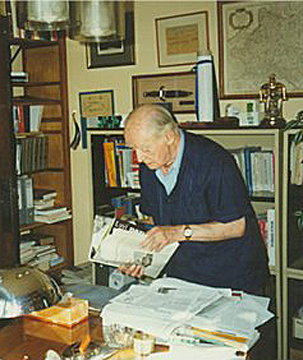

s, and was named for Jerzy Giedroyc

Jerzy Władysław Giedroyc (; 27 July 1906 – 14 September 2000) was a Polish writer and political activist and for many years editor of the highly influential Paris-based periodical, '' Kultura''.

Early life

Giedroyć was born into a Polish- ...

, a Polish émigré publicist, with significant contributions by Juliusz Mieroszewski for whom it is also sometimes named.

History

Giedroyc developed the doctrine in the 1970s in the journal ''Kultura

''Kultura'' (, ''Culture'')—sometimes referred to as ''Kultura Paryska'' ("Paris-based Culture")—was a leading Polish-émigré literary-political magazine, published from 1947 to 2000 by ''Instytut Literacki'' (the Literary Institute), ini ...

'' with Juliusz Mieroszewski (the doctrine is sometimes called the Giedroyc-Mieroszewski doctrineŽivilė Dambrauskaitė, Tomas Janeliūnas, Vytis Jurkonis, Vytautas Sirijos Gira, Lithuanian – Polish Relations Reconsidered: A Constrained Bilateral Agenda or an Empty Strategic Partnership?

' pp. 126–27 online, direct PDF download.) and other émigrés of the "

Maisons-Laffitte

Maisons-Laffitte () is a commune in the Yvelines department in the northern Île-de-France region of France. It is a part of the affluent outer suburbs of northwestern Paris, from its centre. In 2018, it had a population of 23,611.

Maisons-Laf ...

group".Piotr A. MaciążekSłownik Polityki Wschodniej

Polityka Wschodnia, 2011 The doctrine can be traced to the interwar Prometheist project of

Józef Piłsudski

Józef Klemens Piłsudski (; 5 December 1867 – 12 May 1935) was a Polish statesman who served as the Naczelnik państwa, Chief of State (1918–1922) and Marshal of Poland, First Marshal of Second Polish Republic, Poland (from 1920). He was ...

.

The doctrine urged the need to rebuild good relations among East-Central and East European

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whi ...

countries. The doctrine also claimed that the preservation of independence by the new post-Soviet states that lie between Poland and the Russian Federation is a fundamental Polish long-term interest. This called for Poland to reject any imperial ambitions and controversial territorial claims, and to accept the postwar border changes. The doctrine supported independence for Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

and Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

. It also advocated treating all East European countries as equal in importance to Russia, and refusing special treatment for Russia. The doctrine was not hostile to Russia, but called on both Poland and Russia to abandon their struggle over domination of other East European countries — in this context, mainly the Baltic states, Belarus, and Ukraine (hence another name for the doctrine: the "ULB doctrine", where "ULB" stands for "Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus").

Initially it was addressing the attitude of the post-World War II

The aftermath of World War II was the beginning of a new era started in late 1945 (when World War II ended) for all countries involved, defined by the decline of all colonial empires and simultaneous rise of two superpowers; the Soviet Union (US ...

Polish emigres, especially around the Polish government-in-exile

The Polish government-in-exile, officially known as the Government of the Republic of Poland in exile ( pl, Rząd Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej na uchodźstwie), was the government in exile of Poland formed in the aftermath of the Invasion of Pola ...

in London, and basically calling for the recognition of the post-war ''status quo''. Later it was adapted towards the goal of the moving of Belarus, Ukraine and Lithuania away from the Soviet and later Russian sphere of influence.

The doctrine supported the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been de ...

and aimed at removing East-Central and East European countries from the Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nation ...

sphere of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence (SOI) is a spatial region or concept division over which a state or organization has a level of cultural, economic, military or political exclusivity.

While there may be a formal a ...

. After Poland regained its independence from Soviet influence following the fall of communism

The Revolutions of 1989, also known as the Fall of Communism, was a revolutionary wave that resulted in the end of most communist states in the world. Sometimes this revolutionary wave is also called the Fall of Nations or the Autumn of Nat ...

in 1989, the doctrine was implemented in Poland's Eastern foreign policies. Poland itself began integrating into the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been de ...

, eventually joining the EU in 2004. Poland has likewise supported Ukrainian membership in the European Union and NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

. The doctrine has resulted in some tensions in Polish-Russian relations.

The doctrine has been questioned by some commentators and politicians, particularly in the 21st century, and it has been suggested that in recent years the doctrine has been abandoned by the Polish Foreign Ministry

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs (''Ministerstwo Spraw Zagranicznych'', MSZ) is the Polish government department tasked with maintaining Poland's international relations and coordinating its participation in international and regional supra-nation ...

. Others, however, argue that the policy remains in force and is endorsed by the Polish Foreign Ministry.

Pietrzak argues that "Although Giedroyć and Mieroszewski were idealistic, and they were very often criticized for the naïve character of their ideas, they were proven right, for they managed to inadvertently shape the future of the region and encourage most of the countries that border Russia to be more proactive in doing their utmost to preventing a domino effect in Eastern Europe – for Russia clearly attempted to implement a Sudetenland-type scenario in Ukraine in 2022".Piotr Pietrzak (2023, February 3). The Giedroyć-Mieroszewski Doctrine and Poland’s Response to Russia’s Assault on Ukraine. Modern Diplomacy. https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2023/02/03/the-giedroyc-mieroszewski-doctrine-and-polands-response-to-russias-assault-on-ukraine/

See also

*Intermarium

Intermarium ( pl, Międzymorze, ) was a post-World War I geopolitical plan conceived by Józef Piłsudski to unite former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth lands within a single polity. The plan went through several iterations, some of which antic ...

(''Międzymorze'')

* Polish Government in exile

*Prometheism

Prometheism or Prometheanism ( Polish: ''Prometeizm'') was a political project initiated by Józef Piłsudski, a principal statesman of the Second Polish Republic from 1918 to 1935. Its aim was to weaken the Russian Empire and its successor states ...

*Territorial changes of Poland

Poland is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north. The total ...

References

{{reflistExternal links

„''Jeśli nie ULB, to co? Doktryna Giedroycia w XXI w.''”

("If Not ULB, Then What? The Giedroyc Doctrine in the 21st Century", 17 June 2010) *Bartłomiej Sienkiewicz

("Farewell to Giedroyc", ''Rzeczpospolita'', 28-05-2010). *

Zdzisław Najder

Zdzisław Najder (; 31 October 1930 – 15 February 2021) was a Polish literary historian, critic, and political activist.

He was primarily known for his studies on Joseph Conrad, for his periods of service as political adviser to Lech Wałęs ...

"'Doktryna ULB – koncepcja Giedroycia i Mieroszewskiego w XXI wieku''"

("The ULB Doctrine: Giedroyc's and Mieroszewski's Concept in the 21st century")

*Marcin Wojciechowski

"''Co po Giedroyciu? Giedroyc!''"

("What Comes after Giedroyc? Giedroyc!"), ''Nowa Europa Wschodnia'' (New Eastern Europe), 1/2010, pp. 69–77. Foreign relations of Poland Polish People's Republic History of Poland (1989–present) Political history of Poland Foreign policy doctrines Aftermath of World War II in Poland