Gerrit Smith on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Gerrit Smith (March 6, 1797 – December 28, 1874), also spelled Gerritt Smith, was a leading

Smith's maternal aunt, Margaret Livingston, was married to Judge

Smith's maternal aunt, Margaret Livingston, was married to Judge

After becoming an opponent of land

After becoming an opponent of land

Gerrit Smith Papers

Syracuse University Special Collections Research Center. 10,000 letters, 74 boxes. Library description of holdings: "Business, family and general correspondence; business and land records; writings; and maps. Notable correspondents include

''The Road to Seneca Falls''

University of Illinois Press, 2004. * * * * Frothingham, O. B., ''Gerrit Smith: a Biography'' (New York, 1879). . *

''The Gerrit Smith Virtual Museum'' (New York History Net)

at

Historic Peterboro

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Smith, Gerrit 1797 births 1874 deaths 19th-century American politicians Activists from New York (state) American libertarians Former Presbyterians Free Soil Party members of the United States House of Representatives from New York (state) Hamilton College (New York) alumni Liberty Party (United States, 1840) presidential nominees New York (state) Free Soilers New York (state) Libertyites New York (state) Republicans Politicians from Utica, New York People of New York (state) in the American Civil War American social reformers Underground Railroad people American temperance activists American colonization movement American philanthropists Secret Six American suffragists John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry Underground Railroad in New York (state) Members of the United States House of Representatives from New York (state) People from Peterboro, New York Lake Placid, New York

American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

social reformer, abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

, businessman, public intellectual

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and reflection about the reality of society, and who proposes solutions for the normative problems of society. Coming from the world of culture, either as a creator or ...

, and philanthropist

Philanthropy is a form of altruism that consists of "private initiatives, for the public good, focusing on quality of life". Philanthropy contrasts with business initiatives, which are private initiatives for private good, focusing on material ...

. Married to Ann Carroll Fitzhugh, Smith was a candidate for President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

in 1848

1848 is historically famous for the wave of revolutions, a series of widespread struggles for more liberal governments, which broke out from Brazil to Hungary; although most failed in their immediate aims, they significantly altered the polit ...

, 1856

Events

January–March

* January 8 – Borax deposits are discovered in large quantities by John Veatch in California.

* January 23 – American paddle steamer SS ''Pacific'' leaves Liverpool (England) for a transatlantic voya ...

, and 1860

Events

January–March

* January 2 – The discovery of a hypothetical planet Vulcan is announced at a meeting of the French Academy of Sciences in Paris, France.

* January 10 – The Pemberton Mill in Lawrence, Massachusetts ...

, but only won the election to a single term, 1853–1854, in the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

.

Valedictorian

Valedictorian is an academic title for the highest-performing student of a graduating class of an academic institution.

The valedictorian is commonly determined by a numerical formula, generally an academic institution's grade point average (GPA) ...

of his class at the new Hamilton College

Hamilton College is a private liberal arts college in Clinton, Oneida County, New York. It was founded as Hamilton-Oneida Academy in 1793 and was chartered as Hamilton College in 1812 in honor of inaugural trustee Alexander Hamilton, following ...

, he had "a fine mind", with "a strong literary bent and a marked gift for public speaking". He was called "the sage of Peterboro." He was well liked, even by his political enemies. The many who appeared at his house in Peterboro, invited or not, were well received.

Smith, the richest man in New York State and one of the wealthiest in the country, was committed to political reform. Above all, the elimination of slavery; so many fugitive slaves came to Peterboro to ask for his help (usually, in reaching Canada) that there is a book about them. Peterboro was, because of him; the capital of the abolition movement; the only assembly of escaped slaves (as opposed to free Blacks) ever to meet in the United States—the Fugitive Slave Convention

The Fugitive Slave Law Convention was held in Cazenovia, New York, on August 21 and 22, 1850. Madison County, New York, was the abolition headquarters of the country, because of philanthropist and activist Gerrit Smith, who lived in neighboring P ...

of 1850—took place in neighboring Cazenovia because Peterboro was too small for the meeting.

Smith was also, and less successfully, a temperance activist, and a women's rights suffrage advocate. He was a significant financial contributor to the Liberty Party and the Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

* Republican Party (Liberia)

*Republican Party ...

throughout his life. Besides making substantial donations of both land and money to create Timbuctoo

''Timbuctoo'' is a series of 25 children's books, written and illustrated by Roger Hargreaves, better known for his '' Mr. Men'' and ''Little Miss'' series. It was published from 1978 to 1979, with selected reprints in 1993 and 1999. The books ...

, an African-American community in North Elba, New York

North Elba is a town in Essex County, New York, United States. The population was 8,957 at the 2010 census.

North Elba is on the western edge of the county. It is by road southwest of Plattsburgh, south-southwest of Montreal, and north of ...

, he was involved in the temperance movement

The temperance movement is a social movement promoting temperance or complete abstinence from consumption of alcoholic beverages. Participants in the movement typically criticize alcohol intoxication or promote teetotalism, and its leaders emph ...

and the colonization movement

The back-to-Africa movement was based on the widespread belief among some European Americans in the 18th and 19th century United States that African Americans would want to return to the continent of Africa. In general, the political movement wa ...

,Stauffer, ''The Black Hearts of Men'', p. 265 before abandoning colonization in favor of abolitionism

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

, the immediate freeing of all the slaves. He was a member of the Secret Six

The so-called Secret Six, or the Secret Committee of Six, were a group of men who secretly funded the 1859 raid on Harper's Ferry by abolitionist John Brown.

Sometimes described as "wealthy," this was true of only two. The other four were in po ...

who financially supported John Brown's raid

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second ...

at Harpers Ferry

Harpers Ferry is a historic town in Jefferson County, West Virginia. It is located in the lower Shenandoah Valley. The population was 285 at the 2020 census. Situated at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers, where the U.S. stat ...

, in 1859. Brown's farm, in North Elba, was on land he bought from Smith.

Early life

Forebears

Smith was born inUtica, New York

Utica () is a Administrative divisions of New York, city in the Mohawk Valley and the county seat of Oneida County, New York, United States. The List of cities in New York, tenth-most-populous city in New York State, its population was 65,283 ...

, when it was still an unincorporated village, to Peter Gerrit Smith (1768–1837), whose ancestors were from Holland (Gerrit

Gerrit is a Dutch male name meaning "''brave with the spear''", the Dutch and Frisian form of Gerard. People with this name include:

* Gerrit Achterberg (1905–1962), Dutch poet

* Gerrit van Arkel (1858–1918), Dutch architect

* Gerrit Badenh ...

is a Dutch name), and Elizabeth (Livingston) Smith, daughter of Col. James Livingston and Elizabeth (Simpson) Livingston. Peter was a slave owner and the largest landholder in New York State. "In partnership with John Jacob Astor

John Jacob Astor (born Johann Jakob Astor; July 17, 1763 – March 29, 1848) was a German-American businessman, merchant, real estate mogul, and investor who made his fortune mainly in a fur trade monopoly, by smuggling opium into China, and ...

in the fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the mos ...

and alone in real estate, Peter Smith admanaged to amass a considerable fortune. Peter was the county judge of Madison County, New York

Madison County is a county located in the U.S. state of New York. As of the 2020 census, the population was 68,016. Its county seat is Wampsville. The county is named after James Madison, the fourth president of the United States, and was fir ...

, and has been described as 'easily its leading citizen'." He was "a devout and emotionally religious man .. From 1822 on, Peter Smith was intensely engaged in the work of the Bible and Tract

Tract may refer to:

Geography and real estate

* Housing tract, an area of land that is subdivided into smaller individual lots

* Land lot or tract, a section of land

* Census tract, a geographic region defined for the purpose of taking a census

...

societies."

The author of the only book on Peter calls him greedy, self-centered, driven by the search for profits, and someone who did not like people who were not like him: white, male, and Dutch.

He turned over a $400,000 business [] to his son Gerrit in 1819 and bequeathed $800,000 more [] to his children in 1837. Gerrit also inherited of land from his father, and at one point he owned , an area bigger than Rhode Island. An 1846 listing of lands he is offering for sale fills 45 pages.

Smith's maternal aunt, Margaret Livingston, was married to Judge

Smith's maternal aunt, Margaret Livingston, was married to Judge Daniel Cady

Daniel Cady (April 29, 1773 – October 31, 1859 in Johnstown, Fulton County, New York) was a prominent American lawyer, politician and judge in upstate New York. While perhaps better known today as the father of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Judge C ...

. Their daughter Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (November 12, 1815 – October 26, 1902) was an American writer and activist who was a leader of the women's rights movement in the U.S. during the mid- to late-19th century. She was the main force behind the 1848 Seneca ...

, a founder and leader of the women's suffrage movement, was Smith's first cousin. Elizabeth Cady met her future husband, Henry Stanton

Henry Brewster Stanton (June 27, 1805 – January 14, 1887) was an American abolitionist, social reformer, attorney, journalist and politician. His writing was published in the '' New York Tribune,'' the ''New York Sun,'' and William Lloy ...

, also an active abolitionist, at the Smith family home in Peterboro, New York

Peterboro, located approximately southeast of Syracuse, New York, is a historic hamlet and currently the administrative center for the Town of Smithfield, Madison County, New York, United States. Peterboro has a Post Office, ZIP code 13134 ...

. Established in 1795, the town had been founded by and named for Gerrit Smith's father, Peter Smith, who built the family homestead there in 1804. Gerrit came there when he was 9.

Gerrit as a young man

Gerrit was described as "tall, magnificently built and magnificently proportioned, his large head superbly set on his shoulders;" he "might have served as a model for a Greek god in the days when man deified beauty and worshipped it." He attended Hamilton Oneida Academy inClinton, Oneida County, New York

Clinton (or ''Ka-dah-wis-dag'', "white field" in Seneca language) is a village in Oneida County, New York, United States. The population was 1,942 at the 2010 census. It was named for George Clinton, the first Governor of New York.

The Vill ...

, and graduated with honors from its successor Hamilton College

Hamilton College is a private liberal arts college in Clinton, Oneida County, New York. It was founded as Hamilton-Oneida Academy in 1793 and was chartered as Hamilton College in 1812 in honor of inaugural trustee Alexander Hamilton, following ...

in 1818, giving the valedictory

Valedictorian is an academic title for the highest-performing student of a graduating class of an academic institution.

The valedictorian is commonly determined by a numerical formula, generally an academic institution's grade point average (GPA ...

address, and describing his stay at the college as "very active with many friends". In January 1819, he married Wealtha Ann Backus (1800–1819), daughter of Hamilton College's first President, Azel Backus

Azel Backus (October 13, 1765 – December 28, 1816) was an American educator, born in New London County, Connecticut. After having a long preaching career, he was elected as the first President of Hamilton College in New York. He died on Decem ...

D.D. (1765–1817), and sister of Frederick F. Backus (1794–1858). Wealtha died in August of the same year. In 1822, he married Ann Carroll Fitzhugh (1805–1879), sister of Henry Fitzhugh (1801–1866); their relationship "appeared to be loving". They had eight children, but only Elizabeth Smith Miller

Elizabeth Smith Miller ( Smith; September 20, 1822 – May 23, 1911), known as "Libby", was an American advocate and financial supporter of the women's rights movement.NY History Net (April 21, 2011).

Biography

Elizabeth Smith was born Septembe ...

(1822–1911), mother of his grandson Gerrit Smith Miller

Gerrit Smith Miller (January 30, 1845 – March 10, 1937) was a grandson of and named for the famous abolitionist, businessman, and philanthropist Gerrit Smith. His parents were Smith's daughter, Elizabeth Smith Miller, and her husband Charles Dud ...

, and Greene Smith

Greene Smith (1842–1886) was an Americans, American amateur scientist and taxidermist with a specific interest in ornithology. His father was Gerrit Smith.

Personal life

Greene Smith was born in 1842. He was the son of Gerrit Smith. He starte ...

(c. 1841–1880) survived to adulthood.

In the year of his graduation, the death of his mother plunged his father, Peter, into severe depression. He withdrew from all business and vested in his second son Gerrit, who had to abandon plans for a law career, the entire charge of his estate, described as "monumental".

He became an active temperance

Temperance may refer to:

Moderation

*Temperance movement, movement to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed

*Temperance (virtue), habitual moderation in the indulgence of a natural appetite or passion

Culture

*Temperance (group), Canadian danc ...

campaigner, and claimed to have given in 1824 the first temperance speech ever in the New York State Legislature

The New York State Legislature consists of the two houses that act as the state legislature of the U.S. state of New York: The New York State Senate and the New York State Assembly. The Constitution of New York does not designate an official ...

. In his hometown of Peterboro, he built one of the first temperance hotels in the country, which was not successful commercially, and was disliked by many locals.

Smith wrote of himself:

Gerrit in the 1830s

He attended numerous revival meetings, and taughtSunday school

A Sunday school is an educational institution, usually (but not always) Christian in character. Other religions including Buddhism, Islam, and Judaism have also organised Sunday schools in their temples and mosques, particularly in the West.

Su ...

. He thought of establishing a seminary for Black students. In 1834 he began a Peterboro Manual Labor School

A manual labor college was a type of school in the United States, primarily between 1825 and 1860, in which work, usually agricultural or mechanical, supplemented academic activity.

The manual labor model was intended to make educational opportuni ...

for Black students, along the model of nearby Oneida Institute

The Oneida Institute was a short-lived (1827–1843) but highly influential school that was a national leader in the emerging Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist movement. It was the most radical school in the country, the first at w ...

. It had only one instructor, and it lasted only one year. Previously a supporter of the American Colonization Society

The American Colonization Society (ACS), initially the Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America until 1837, was an American organization founded in 1816 by Robert Finley to encourage and support the migration of freebor ...

, he became an abolitionist in 1835 after a mob in Utica, including New York congressman and future Attorney General Samuel Beardsley

Samuel Beardsley (February 6, 1790 – May 6, 1860) was an American attorney, judge and legislator from New York. During his career he served as a member of the United States House of Representatives, New York Attorney General, United States ...

, broke up the initial meeting of the New York Anti-Slavery Society, which he attended at the urging of his friends Beriah Green

Beriah Green Jr. (March 24, 1795May 4, 1874) was an American reformer, abolitionist, temperance advocate, college professor, minister, and head of the Oneida Institute. He was "consumed totally by his abolitionist views". He has been described as ...

and Alvan Stewart Alvan or Alavan may refer to:

* Alvan (singer), a French singer

* Alvan (biblical figure), a minor biblical figure

* Alvan, East Azerbaijan, a village in East Azerbaijan Province, Iran

* Alvan, Iran, a city in Khuzestan Province

* Alvan, Shadegan, ...

. At his invitation, the meeting continued the next day in Peterboro. He resigned as a trustee of Hamilton College "on the grounds that the school was insufficiently anti-slavery", and joined the board of and financially assisted the Oneida Institute

The Oneida Institute was a short-lived (1827–1843) but highly influential school that was a national leader in the emerging Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist movement. It was the most radical school in the country, the first at w ...

, "a hotbed of anti-slavery activity". He contributed $9,000 () to support schools in Liberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to its north, Ivory Coast to its east, and the Atlantic Ocean ...

, but realized by 1835 that the American Colonization Society

The American Colonization Society (ACS), initially the Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America until 1837, was an American organization founded in 1816 by Robert Finley to encourage and support the migration of freebor ...

had no intention of abolishing slavery.

Smith was a laggard instead of a leader in changing from supporting colonization to "immediatism",

immediate full abolitionism

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

. Support for Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as a ...

after the war would have been unthinkable for Garrison, Douglass, or other abolitionist leaders.

Political career

"It must be admitted that few men in this country have been a candidate for high office so many times and polled so few votes." In 1840, Smith played a leading part in the organization of the Liberty Party; the name of the party was his. In the same year, theirpresidential candidate

A candidate, or nominee, is the prospective recipient of an award or honor, or a person seeking or being considered for some kind of position; for example:

* to be elected to an office — in this case a candidate selection procedure occurs.

* t ...

James G. Birney married Elizabeth Potts Fitzhugh, Smith's sister-in-law. Smith and Birney travelled to London that year to attend the World Anti-Slavery Convention

The World Anti-Slavery Convention met for the first time at Exeter Hall in London, on 12–23 June 1840. It was organised by the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, largely on the initiative of the English Quaker Joseph Sturge. The exclu ...

in London.

Birney, but not Smith, is recorded in the commemorative painting of the event. In 1848, Smith was nominated for the Presidency

A presidency is an administration or the executive, the collective administrative and governmental entity that exists around an office of president of a state or nation. Although often the executive branch of government, and often personified b ...

by the remnant of this organization that had not been absorbed by the Free Soil Party

The Free Soil Party was a short-lived coalition political party in the United States active from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party. The party was largely focused on the single issue of opposing the expansion of slavery int ...

. An "Industrial Congress" at Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

also nominated him for the presidency in 1848, and the "Land Reformers" in 1856. In 1840

Events

January–March

* January 3 – One of the predecessor papers of the ''Herald Sun'' of Melbourne, Australia, ''The Port Phillip Herald'', is founded.

* January 10 – Uniform Penny Post is introduced in the United Kingdom.

* Janua ...

and again in 1858, he ran for Governor of New York

The governor of New York is the head of government of the U.S. state of New York. The governor is the head of the executive branch of New York's state government and the commander-in-chief of the state's military forces. The governor has ...

on an anti-slavery platform.

On June 2, 1848, in Rochester, New York

Rochester () is a City (New York), city in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York, the county seat, seat of Monroe County, New York, Monroe County, and the fourth-most populous in the state after New York City, Buffalo, New York, Buffalo, ...

, Smith was nominated as the Liberty Party's presidential candidate.Wellman, 2004, p. 176. At the National Liberty Convention, held June 14–15 in Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second-largest city in the U.S. state of New York (behind only New York City) and the seat of Erie County. It is at the eastern end of Lake Erie, at the head of the Niagara River, and is across the Canadian border from South ...

, Smith gave a major address, including in his speech a demand for "universal suffrage in its broadest sense, females as well as males being entitled to vote." The delegates approved a passage in their address to the people of the United States addressing votes for women: "Neither here, nor in any other part of the world, is the right of suffrage allowed to extend beyond one of the sexes. This universal exclusion of woman...argues, conclusively, that, not as yet, is there one nation so far emerged from barbarism, and so far practically Christian, as to permit woman to rise up to the one level of the human family." Reverend Charles C. Foote was nominated as his running mate. The ticket would come in fourth place in the election, carrying 2,545 popular votes, all from New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

.

At the request of friends, Smith had 3,000 copies printed of an 1851 speech in Troy in which he set forth his views of government. Smith laments the people's universal dependence on government. As a consequence of that dependence, government occupies itself "for the most part, in doing that it belongs to the people to do". He opposed tariffs, internal improvements, such as the Erie Canal

The Erie Canal is a historic canal in upstate New York that runs east-west between the Hudson River and Lake Erie. Completed in 1825, the canal was the first navigable waterway connecting the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes, vastly reducing t ...

, at public expense, and publicly-supported schools, which could not teach religion, which Smith thought the main function of schools. The remedy was less government, and the less, the better.

The only political office to which Smith was ever elected, and that by a very large majority, was Representative in the U.S. Congress. Smith served a single term in Congress, on the Free Soil ticket, from March 4, 1853, until the end of the session on August 7, 1854, although he said that because of his business activities he had sought neither the nomination nor his election. ("My nomination to Congress alarmed me greatly, because I believed that it would result in my election.") He made a point of resigning his seat on the last day of the session. He then published a lengthy letter to his constituents explaining his frustrations in Congress and his decision not to run for a second term. He was well liked, even by Southern members, who found him "one of the best fellows in the Capitol, as one, although well known as an abolitionist, still as one to be tolerated".

By 1856, very little of the Liberty Party remained after most of its members joined the Free Soil Party in 1848 and nearly of all what remained of the party joined the Republicans in 1854. The small remnant of the party renominated Smith under the name of the "National Liberty Party".

In 1860, the remnant of the party was also called the Radical Abolitionists. A convention of one hundred delegates was held in Convention Hall, Syracuse, New York, on August 29, 1860. Delegates were in attendance from New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Michigan, Illinois, Ohio, Kentucky, and Massachusetts. Several of the delegates were women. Smith, despite his poor health, fought William Goodell in regard to the nomination for the presidency. In the end, Smith was nominated for president and Samuel McFarland

Samuel ''Šəmūʾēl'', Tiberian Hebrew, Tiberian: ''Šămūʾēl''; ar, شموئيل or صموئيل '; el, Σαμουήλ ''Samouḗl''; la, Samūēl is a figure who, in the narratives of the Hebrew Bible, plays a key role in the transit ...

from Pennsylvania was nominated for vice president. The ticket won 171 popular votes from Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...

and Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

. In Ohio, a slate of presidential electors pledged to Smith ran with the name of the Union Party.

Smith, along with his friend and ally Lysander Spooner

Lysander Spooner (January 19, 1808May 14, 1887) was an American individualist anarchist, abolitionist, entrepreneur, essayist, legal theorist, pamphletist, political philosopher, Unitarian and writer.

Spooner was a strong advocate of the labo ...

, was a leading advocate of the United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven ar ...

as an antislavery document, as opposed to abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was a prominent American Christian, abolitionist, journalist, suffragist, and social reformer. He is best known for his widely read antislavery newspaper '' The Liberator'', which he found ...

, who believed it was to be condemned as a pro-slavery document, and was in favor of secession by the North. In 1852, Smith was elected to the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the Lower house, lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the United States Senate, Senate being ...

as a Free-Soiler. In his address, he declared that all men have an equal right to the soil; that wars are brutal and unnecessary; that slavery could be sanctioned by no constitution, state or federal; that free trade is essential to human brotherhood; that women should have full political rights; that the Federal government and the states should prohibit the liquor traffic within their respective jurisdictions; and that government officers, so far as practicable, should be elected by direct vote of the people. Unhappy with his separation from his home and business, Smith resigned his seat at the end of the first session, ostensibly to allow voters sufficient time to select his successor.

In 1869, Smith served as a delegate to the founding convention of the Prohibition Party

The Prohibition Party (PRO) is a political party in the United States known for its historic opposition to the sale or consumption of alcoholic beverages and as an integral part of the temperance movement. It is the oldest existing third party ...

. During the 1872 presidential election Smith was considered for the Prohibition Party's presidential nomination.

Support for Blacks

According to Black Rev.Henry Highland Garnet

Henry Highland Garnet (December 23, 1815 – February 13, 1882) was an African-American abolitionist, minister, educator and orator. Having escaped as a child from slavery in Maryland with his family, he grew up in New York City. He was educat ...

, who moved there at Smith's invitation, "There are yet two places where slave holders cannot come—Heaven and Peterboro."

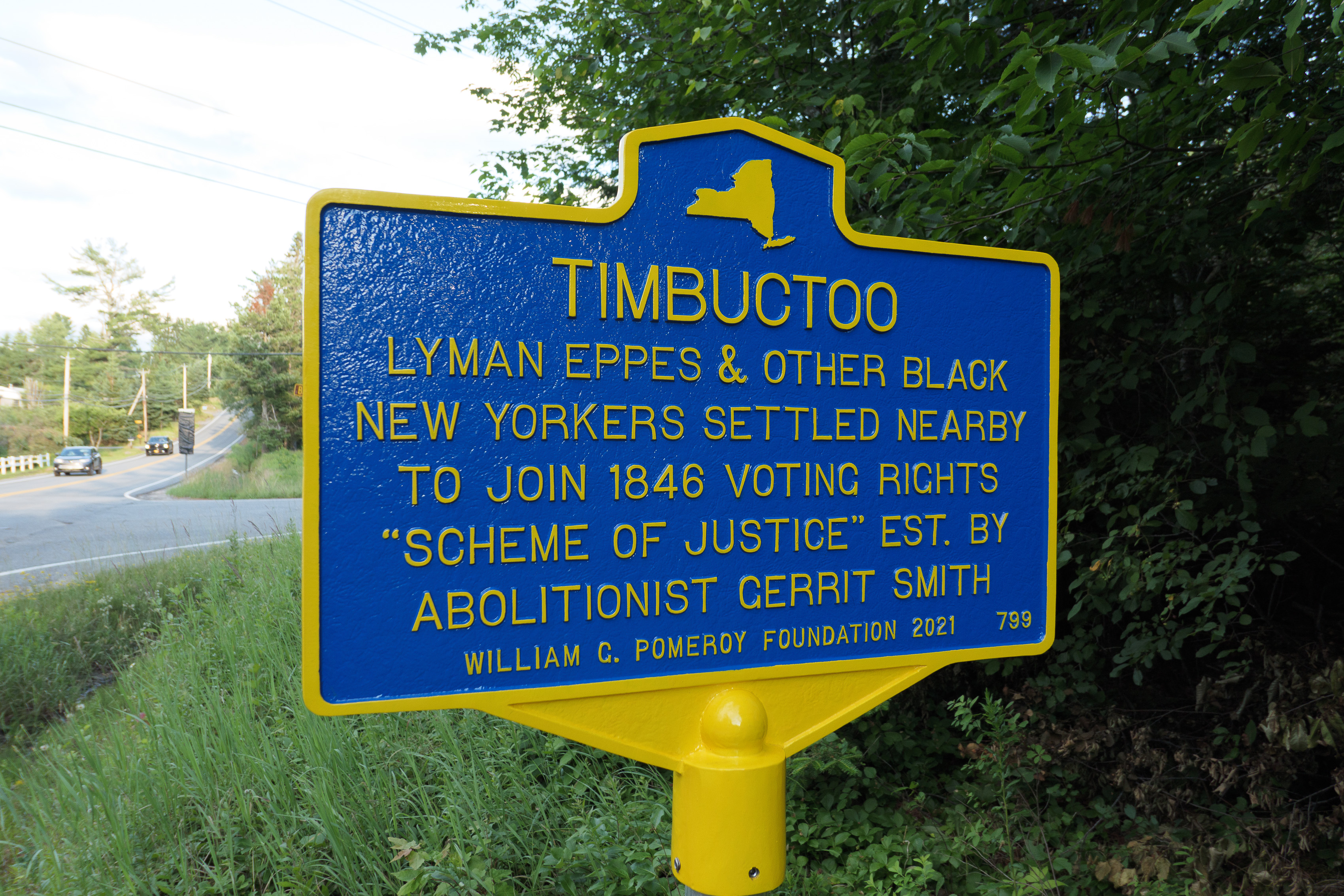

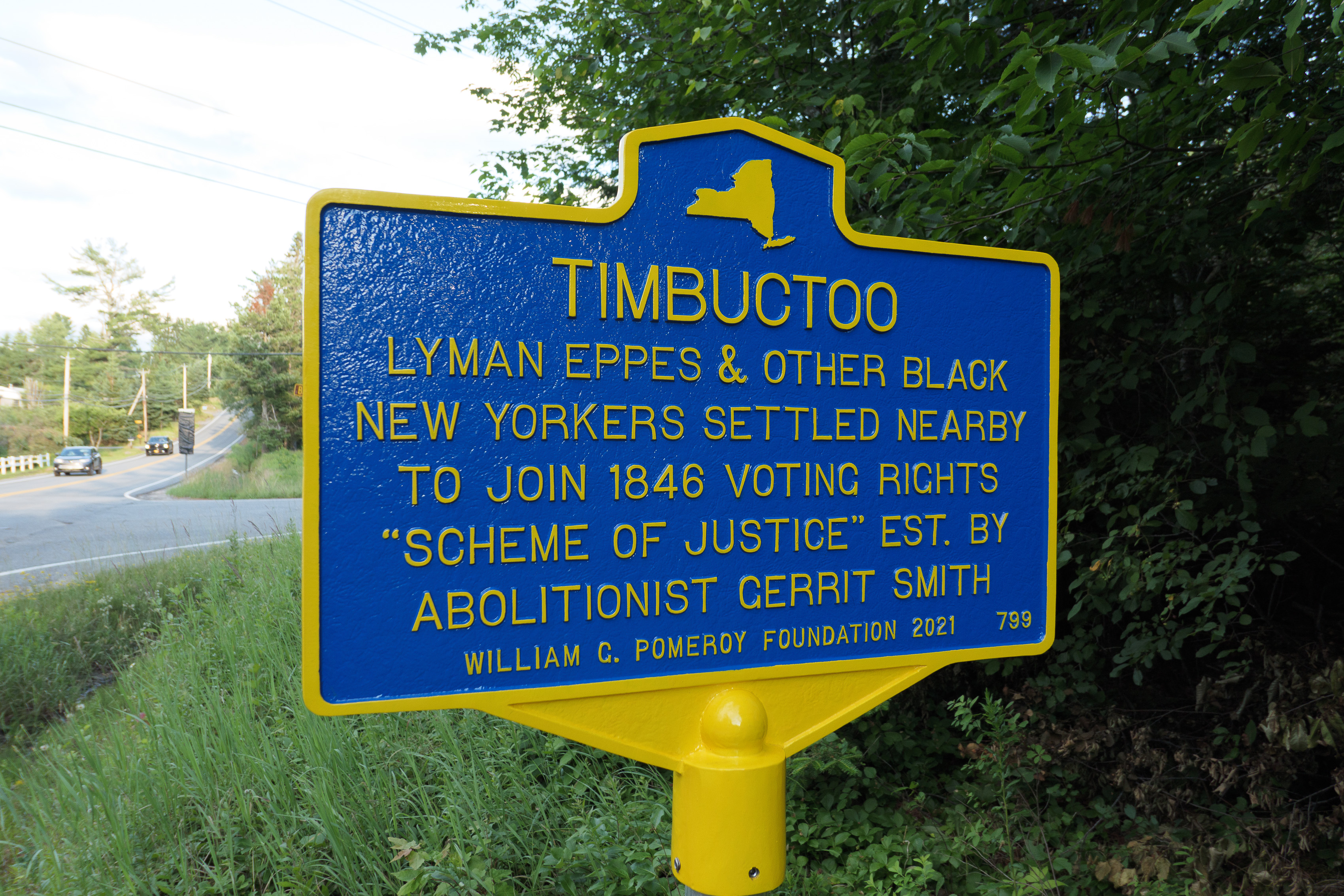

The failed land redistribution project (Timbuctoo)

After becoming an opponent of land

After becoming an opponent of land monopoly

A monopoly (from Greek language, Greek el, μόνος, mónos, single, alone, label=none and el, πωλεῖν, pōleîn, to sell, label=none), as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situati ...

, he gave numerous farms of each to 1,000 "worthy" New York state Blacks. In 1846, hoping to help black families become self-sufficient, to isolate and thus protect them from escaped slave-hunters, and to provide them with the property ownership that was needed for Blacks to vote in New York, Smith attempted to help free blacks settle approximately of land he owned in the remote Adirondacks

The Adirondack Mountains (; a-də-RÄN-dak) form a massif in northeastern New York with boundaries that correspond roughly to those of Adirondack Park. They cover about 5,000 square miles (13,000 km2). The mountains form a roughly circular d ...

. Abolitionist John Brown John Brown most often refers to:

*John Brown (abolitionist) (1800–1859), American who led an anti-slavery raid in Harpers Ferry, Virginia in 1859

John Brown or Johnny Brown may also refer to:

Academia

* John Brown (educator) (1763–1842), Ir ...

joined his project, purchasing land and moving his family there. However, the land Smith gave away was "of but moderate fertility", "heavily timbered, and in no respect remarkably inviting". In Smith's own words, it was his "poorest land"; his better land he sold.

Most grantees never saw the remote land Smith had given them; many of those who did visit it soon left, and in 1857, it was estimated that less than 10% of the grantees were actually living on their land. The difficulty of farming in the mountains, coupled with the settlers' lack of experience in housebuilding and farming and the bigotry of white neighbors, caused the project to fail. As Smith put it, "I was perhaps a better land-reformer in theory than in practice." The John Brown Farm State Historic Site

The John Brown Farm State Historic Site includes the home and final resting place of abolitionist John Brown (1800–1859). It is located on John Brown Road in the town of North Elba, 3 miles (5 km) southeast of Lake Placid, New York, where ...

is all that remains of the settlement, called Timbuctoo, New York

Timbuctoo, New York, was a mid-19th century farming community of African-American homesteaders in the remote town of North Elba, New York. It was located in the vicinity of , near today's Lake Placid village (which did not exist then), in the Adi ...

.

The Chapin slave escape

Peterboro became a station on theUnderground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. T ...

. Due to his connections with it, Smith financially supported a planned mass slave escape in Washington, D.C., in April 1848, organized by William L. Chaplin

William Lawrence Chaplin (October 27, 1796 – April 28, 1871) was a prominent abolitionist in the years before the American Civil War. Known by the title of "General," he was an agent for the American Anti-Slavery Society and a general agent fo ...

, another abolitionist, as well as numerous members of the city's large free black community. The Pearl incident

The ''Pearl'' incident was the largest recorded nonviolent escape attempt by enslaved people in United States history. On April 15, 1848, seventy-seven slaves attempted to escape Washington D.C. by sailing away on a schooner called ''The Pearl'' ...

attracted widespread national attention after the 77 slaves were intercepted and captured about two days after they sailed from the capital.

Defending Fugitive Slave Law violators

Smith paid the legal expenses of several persons charged with infractions of theFugitive Slave Law of 1850

The Fugitive Slave Act or Fugitive Slave Law was passed by the United States Congress on September 18, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850 between Southern interests in slavery and Northern Free-Soilers.

The Act was one of the most cont ...

.

Helping John Brown in Kansas

Smith became a leading figure in the Kansas Aid Movement, a campaign to raise money and show solidarity with anti-slavery immigrants to that territory. It was during this movement that he first met and financially supportedJohn Brown John Brown most often refers to:

*John Brown (abolitionist) (1800–1859), American who led an anti-slavery raid in Harpers Ferry, Virginia in 1859

John Brown or Johnny Brown may also refer to:

Academia

* John Brown (educator) (1763–1842), Ir ...

.

Harpers Ferry

Smith was a member of what much later was called theSecret Six

The so-called Secret Six, or the Secret Committee of Six, were a group of men who secretly funded the 1859 raid on Harper's Ferry by abolitionist John Brown.

Sometimes described as "wealthy," this was true of only two. The other four were in po ...

, a informal group of influential Northern abolitionists, who supported Brown in his efforts to capture the armory at Harpers Ferry

Harpers Ferry is a historic town in Jefferson County, West Virginia. It is located in the lower Shenandoah Valley. The population was 285 at the 2020 census. Situated at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers, where the U.S. stat ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

(since 1863, West Virginia) and start a slave revolt. After the failed raid on Harpers Ferry, Senator Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as a ...

unsuccessfully attempted to have Smith accused, tried, and hanged along with Brown. Governor Wise suggested that Smith be brought to him, "by fair or foul means", but residents of Peterboro said publicly that they would use guns to protect him.

Upset by the raid, its outcome, and its aftermath, expecting to be indicted, Smith suffered a mental breakdown; he was described in the press as "a raving lunatic", who became "very violent". For several weeks he was confined to the Utica Psychiatric Center

The Utica Psychiatric Center, also known as Utica State Hospital, opened in Utica on January 16, 1843.

It was New York's first state-run facility designed to care for the mentally ill, and one of the first such institutions in the Un ...

, at the time called the State Lunatic Asylum. He was accused of feigning his illness, but multiple reports state that it was genuine. He was initially on a suicide watch.

When the Chicago ''Tribune'' later claimed Smith had full knowledge of Brown's plan at Harper's Ferry, Smith sued the paper for libel

Defamation is the act of communicating to a third party false statements about a person, place or thing that results in damage to its reputation. It can be spoken (slander) or written (libel). It constitutes a tort or a crime. The legal defini ...

, claiming that he lacked any such knowledge and thought only that Brown wanted guns so that slaves who ran away to join him might defend themselves against attackers. Smith's claim was countered by the ''Tribune'', which produced an affidavit, signed by Brown's son, swearing that Smith had full knowledge of all the particulars of the plan, including the plan to instigate a slave uprising. In writing later of these events, Smith said, "That affair excited and shocked me, and a few weeks after I was taken to a lunatic asylum. From that day to this I have had but a hazy view of dear John Brown's great work. Indeed, some of my impressions of it have, as others have told me, been quite erroneous and even wild." Ralph Harlow concluded his examination of the episode with this quote from Brown: "G S he knew to be a timid man".

While in the New York Lunatic Asylum, today (2022) the Utica Psychiatric Center

The Utica Psychiatric Center, also known as Utica State Hospital, opened in Utica on January 16, 1843.

It was New York's first state-run facility designed to care for the mentally ill, and one of the first such institutions in the Un ...

, he was treated with cannabis

''Cannabis'' () is a genus of flowering plants in the family Cannabaceae. The number of species within the genus is disputed. Three species may be recognized: ''Cannabis sativa'', '' C. indica'', and '' C. ruderalis''. Alternatively ...

and morphine

Morphine is a strong opiate that is found naturally in opium, a dark brown resin in poppies (''Papaver somniferum''). It is mainly used as a analgesic, pain medication, and is also commonly used recreational drug, recreationally, or to make ...

.

Other social activism

Smith was a major benefactor ofNew-York Central College

New York Central College, commonly called New York Central College, McGrawville, and simply Central College, was the first college in the United States founded on the principle that all qualified students were welcome. It was thus an abolitionist ...

, a co-educational

Mixed-sex education, also known as mixed-gender education, co-education, or coeducation (abbreviated to co-ed or coed), is a system of education where males and females are educated together. Whereas single-sex education was more common up to t ...

and "racially" integrated college in Cortland County

Cortland County is a County (United States), county located in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population of Cortland County was 46,809. The county seat is Cortland, New York, C ...

.

Smith supported the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, but at its close he advocated a mild policy toward the late Confederate states

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

, declaring that part of the guilt of slavery lay upon the North. In 1867, Smith, together with Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and newspaper editor, editor of the ''New-York Tribune''. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congressm ...

and Cornelius Vanderbilt

Cornelius Vanderbilt (May 27, 1794 – January 4, 1877), nicknamed "the Commodore", was an American business magnate who built his wealth in railroads and shipping. After working with his father's business, Vanderbilt worked his way into lead ...

, helped to underwrite the $100,000 bond needed to free Jefferson Davis, who had, at that time, been imprisoned for nearly two years without being charged with any crime. In doing this, Smith incurred the resentment of Northern Radical Republican

The Radical Republicans (later also known as " Stalwarts") were a faction within the Republican Party, originating from the party's founding in 1854, some 6 years before the Civil War, until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Reco ...

leaders.

Smith's passions extended to religion as well as politics. Believing that sectarianism

Sectarianism is a political or cultural conflict between two groups which are often related to the form of government which they live under. Prejudice, discrimination, or hatred can arise in these conflicts, depending on the political status quo ...

was sinful, he separated from the Presbyterian Church

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

in 1843. He was one of the founders of the Church at Peterboro, a non-denominational institution open to all non-slave-owning Christians.

His private benefactions were substantial; of his gifts he kept no record, but their value is said to have exceeded $8,000,000. Though a man of great wealth, his life was one of marked simplicity. He died in 1874 while visiting relatives in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

.

The Gerrit Smith Estate

The Gerrit Smith Estate is a historic residential estate at Oxbow Road and Peterboro Road in Peterboro, New York. It was home to Gerrit Smith (1797-1874), a 19th-century social reformer, abolitionist, and presidential candidate, and his wife, ...

, in Peterboro, New York

Peterboro, located approximately southeast of Syracuse, New York, is a historic hamlet and currently the administrative center for the Town of Smithfield, Madison County, New York, United States. Peterboro has a Post Office, ZIP code 13134 ...

, was declared a National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the United States government for its outstanding historical significance. Only some 2,500 (~3%) of over 90,000 places listed ...

in 2001.

Tribute

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

dedicated to Smith ''My Bondage and My Freedom

''My Bondage and My Freedom'' is an autobiographical slave narrative written by Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social refo ...

'' (1855):

Years before, a student at his Peterboro Manual Labor School, where "Mr. Smith liberally supplies us with stationery, books, board and lodging", stated that "if the man of color has a sincere friend, that friend is Gerrit Smith".

Philanthropic activities

Smith provided support for a large number of progressive causes and people and, except for his land grants, did not keep careful records. The dates given are in some cases approximate, either because documents do not provide a definite date, or because there were multiple payments. * " of his land he had divided among various destitute people, and 650 poor women have received money from him to help provide themselves with homes." * Built and ran unsuccessfultemperance hotel

A coffee palace was an often large and elaborate residential hotel that did not serve alcohol, most of which were built in Australia in the late 19th century.

A modest temperance hotel was opened in 1826 by activist Gerrit Smith in his hom ...

in Peterboro, 1826–1831.

* Supporter of American Colonization Society

The American Colonization Society (ACS), initially the Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America until 1837, was an American organization founded in 1816 by Robert Finley to encourage and support the migration of freebor ...

, 1820s–early 1830s.

* Support for the Oneida Institute

The Oneida Institute was a short-lived (1827–1843) but highly influential school that was a national leader in the emerging Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist movement. It was the most radical school in the country, the first at w ...

, 1830s.

* Manual labor school

A manual labor college was a type of school in the United States, primarily between 1825 and 1860, in which work, usually agricultural or mechanical, supplemented academic activity.

The manual labor model was intended to make educational opportuni ...

for "colored boys" in Peterboro, 1834-1836 (two years). Benjamin Quarles suggests that Smith may have ended the project because it was duplicating what was available at the nearby Oneida Institute

The Oneida Institute was a short-lived (1827–1843) but highly influential school that was a national leader in the emerging Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist movement. It was the most radical school in the country, the first at w ...

, headed by his friend Beriah Green

Beriah Green Jr. (March 24, 1795May 4, 1874) was an American reformer, abolitionist, temperance advocate, college professor, minister, and head of the Oneida Institute. He was "consumed totally by his abolitionist views". He has been described as ...

.

* Founder of church in Peterboro, 1843. (Dissatisfied with existing churches' refusal to insist on abolition.)

* Supported Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

' abolitionist newspaper, The North Star, late 1840s.

* Supported planned mass slave escape in Washington, DC, in April 1848, organized by William L. Chaplin

William Lawrence Chaplin (October 27, 1796 – April 28, 1871) was a prominent abolitionist in the years before the American Civil War. Known by the title of "General," he was an agent for the American Anti-Slavery Society and a general agent fo ...

.

* Provided land in North Elba, New York

North Elba is a town in Essex County, New York, United States. The population was 8,957 at the 2010 census.

North Elba is on the western edge of the county. It is by road southwest of Plattsburgh, south-southwest of Montreal, and north of ...

, to support Timbuctoo

''Timbuctoo'' is a series of 25 children's books, written and illustrated by Roger Hargreaves, better known for his '' Mr. Men'' and ''Little Miss'' series. It was published from 1978 to 1979, with selected reprints in 1993 and 1999. The books ...

settlement of Black farmers, 1848.

* Sold land in North Elba to John Brown John Brown most often refers to:

*John Brown (abolitionist) (1800–1859), American who led an anti-slavery raid in Harpers Ferry, Virginia in 1859

John Brown or Johnny Brown may also refer to:

Academia

* John Brown (educator) (1763–1842), Ir ...

"for a bargain price of $1 an acre".

* Major benefactor of New-York Central College

New York Central College, commonly called New York Central College, McGrawville, and simply Central College, was the first college in the United States founded on the principle that all qualified students were welcome. It was thus an abolitionist ...

, 1850s.

* Helped with legal expenses of Fugitive Slave Law

The fugitive slave laws were laws passed by the United States Congress in 1793 and 1850 to provide for the return of enslaved people who escaped from one state into another state or territory. The idea of the fugitive slave law was derived from ...

violators, 1850s.

* About 1855, gave $25,000 () to build the Oswego City Library, and $5,000 for books.

* Leading figure in the New England Emigrant Aid Society

The New England Emigrant Aid Company (originally the Massachusetts Emigrant Aid Company) was a transportation company founded in Boston, Massachusetts by activist Eli Thayer in the wake of the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which allowed the population of ...

(Kansas Aid Movement), assisting abolitionist settlers and John Brown John Brown most often refers to:

*John Brown (abolitionist) (1800–1859), American who led an anti-slavery raid in Harpers Ferry, Virginia in 1859

John Brown or Johnny Brown may also refer to:

Academia

* John Brown (educator) (1763–1842), Ir ...

working to make Kansas a free state, 1850s.

* Paid for printing of James Redpath

James Redpath (August 24, 1833 in Berwick upon Tweed, England – February 10, 1891, in New York, New York) was an American journalist and anti-slavery activist.

Life

In 1848 or 1849, Redpath and his family emigrated from Scotland to a farm nea ...

's ''The Roving Editor: or, Talks with Slaves in the Southern States'', 1859.

* One of Secret Six

The so-called Secret Six, or the Secret Committee of Six, were a group of men who secretly funded the 1859 raid on Harper's Ferry by abolitionist John Brown.

Sometimes described as "wealthy," this was true of only two. The other four were in po ...

that helped finance John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry, 1859

* One of guarantors of Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as a ...

's bond, 1867.

* William G. Allen and family, in or near poverty in London, 1870s and 1880s.

After his death, a newspaper reported his philanthropic activities as follows:

Writings

Smith paid for the printing of hundreds ofbroadside

Broadside or broadsides may refer to:

Naval

* Broadside (naval), terminology for the side of a ship, the battery of cannon on one side of a warship, or their near simultaneous fire on naval warfare

Printing and literature

* Broadside (comic ...

s, with his views on a variety of subjects. His own collection of his pamphlets is in the Syracuse University Library. A number of recipients bound those they received into volumes, different contents for each collector.

*

*

*

*

* Probably written by Smith. Includes (pp. 16–23) an "Extract from a letter by Gerrit Smith to Rev. Wm. H. Brisbane".

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Archival material

Smith's grandson,Gerrit Smith Miller

Gerrit Smith Miller (January 30, 1845 – March 10, 1937) was a grandson of and named for the famous abolitionist, businessman, and philanthropist Gerrit Smith. His parents were Smith's daughter, Elizabeth Smith Miller, and her husband Charles Dud ...

, was the final resident of the Smith mansion. In 1928, before it burned, he donated Smith's enormous collection of letters, documents, diaries, and daybooks to the Syracuse University Library, along with a pamphlet and broadside collection of over 700 items. There is nothing like it for any other businessman of his day.

Gerrit Smith Papers

Syracuse University Special Collections Research Center. 10,000 letters, 74 boxes. Library description of holdings: "Business, family and general correspondence; business and land records; writings; and maps. Notable correspondents include

Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony (born Susan Anthony; February 15, 1820 – March 13, 1906) was an American social reformer and women's rights activist who played a pivotal role in the women's suffrage movement. Born into a Quaker family committed to s ...

, John Jacob Astor

John Jacob Astor (born Johann Jakob Astor; July 17, 1763 – March 29, 1848) was a German-American businessman, merchant, real estate mogul, and investor who made his fortune mainly in a fur trade monopoly, by smuggling opium into China, and ...

, Henry Ward Beecher

Henry Ward Beecher (June 24, 1813 – March 8, 1887) was an American Congregationalist clergyman, social reformer, and speaker, known for his support of the Abolitionism, abolition of slavery, his emphasis on God's love, and his 1875 adultery ...

, Antoinette Blackwell, Caleb Calkins, Lydia Maria Child

Lydia Maria Child ( Francis; February 11, 1802October 20, 1880) was an American abolitionist, women's rights activist, Native American rights activist, novelist, journalist, and opponent of American expansionism.

Her journals, both fiction and ...

, Cassius Clay

Muhammad Ali (; born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr.; January 17, 1942 – June 3, 2016) was an American professional boxer and activist. Nicknamed "The Greatest", he is regarded as one of the most significant sports figures of the 20th century, a ...

, Alfred Conkling

Alfred Conkling (October 12, 1789 – February 5, 1874) was a United States representative from New York, a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Northern District of New York and United States Minister to Mex ...

, Roscoe Conkling

Roscoe Conkling (October 30, 1829April 18, 1888) was an American lawyer and Republican Party (United States), Republican politician who represented New York (state), New York in the United States House of Representatives and the United States Se ...

, Charles A. Dana, Paulina W. Davis, Edward C. Delavan Edward Cornelius Delavan (1793–1871) was a wealthy businessman who devoted much of his fortune to promoting the temperance movement. He helped establish the American Temperance Union; attacked the use of wine in Christian communion; established a ...

, Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

, Albert G. Finney, Sarah Grimké

Sarah (born Sarai) is a biblical matriarch and prophetess, a major figure in Abrahamic religions. While different Abrahamic faiths portray her differently, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam all depict her character similarly, as that of a pi ...

, Elizabeth Cady and Henry B. Stanton

Henry Brewster Stanton (June 27, 1805 – January 14, 1887) was an American Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, social reformer, Lawyer, attorney, journalist and politician. His writing was published in the ''New York Tribune, ...

, Louis Tappan, Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth (; born Isabella Baumfree; November 26, 1883) was an American abolitionist of New York Dutch heritage and a women's rights activist. Truth was born into slavery in Swartekill, New York, but escaped with her infant daughter to f ...

, and Theodore Weld

Theodore Dwight Weld (November 23, 1803 – February 3, 1895) was one of the architects of the American abolitionist movement during its formative years from 1830 to 1844, playing a role as writer, editor, speaker, and organizer. He is best known ...

." The collection has been microfilmed, and together with materials of his father Peter Smith, fills 89 reels. A partial calendar of the general correspondence was published in 1941. The Special Collections Research Center of Syracuse University

Syracuse University (informally 'Cuse or SU) is a Private university, private research university in Syracuse, New York. Established in 1870 with roots in the Methodist Episcopal Church, the university has been nonsectarian since 1920. Locate ...

also holds Smith's pamphlet collection, "700+ items", which has also been microfilmed, and over half digitized and available online.

* Another important collection of documents related to Gerrit Smith is found in the archives of his alma mater, Hamilton College

Hamilton College is a private liberal arts college in Clinton, Oneida County, New York. It was founded as Hamilton-Oneida Academy in 1793 and was chartered as Hamilton College in 1812 in honor of inaugural trustee Alexander Hamilton, following ...

, in Clinton, Oneida County, New York

Clinton (or ''Ka-dah-wis-dag'', "white field" in Seneca language) is a village in Oneida County, New York, United States. The population was 1,942 at the 2010 census. It was named for George Clinton, the first Governor of New York.

The Vill ...

.

* Additional documents are in the collections of the Peterboro and the Madison County Historical Societies.

See also

*Fugitive Slave Convention

The Fugitive Slave Law Convention was held in Cazenovia, New York, on August 21 and 22, 1850. Madison County, New York, was the abolition headquarters of the country, because of philanthropist and activist Gerrit Smith, who lived in neighboring P ...

* Gerrit Smith Estate

The Gerrit Smith Estate is a historic residential estate at Oxbow Road and Peterboro Road in Peterboro, New York. It was home to Gerrit Smith (1797-1874), a 19th-century social reformer, abolitionist, and presidential candidate, and his wife, ...

* National Abolition Hall of Fame and Museum

The National Abolition Hall of Fame and Museum is located on the second floor of a historic Presbyterian church, located at 5255 Pleasant Valley Road, between Elizabeth and Park Streets, in the hamlet of Peterboro, New York. The church, built in ...

* Peterboro Land Office

The Peterboro Land Office is located in the hamlet of Peterboro, in the Town of Smithfield in Madison County, New York. The small, Federal style building was built in 1804. It was constructed of locally produced brick laid in Flemish bond on ...

* Peterboro, New York

Peterboro, located approximately southeast of Syracuse, New York, is a historic hamlet and currently the administrative center for the Town of Smithfield, Madison County, New York, United States. Peterboro has a Post Office, ZIP code 13134 ...

Relatives of Smith

* Ann Carroll Fitzhugh, wife *Elizabeth Smith Miller

Elizabeth Smith Miller ( Smith; September 20, 1822 – May 23, 1911), known as "Libby", was an American advocate and financial supporter of the women's rights movement.NY History Net (April 21, 2011).

Biography

Elizabeth Smith was born Septembe ...

, daughter

* Gerrit Smith Miller

Gerrit Smith Miller (January 30, 1845 – March 10, 1937) was a grandson of and named for the famous abolitionist, businessman, and philanthropist Gerrit Smith. His parents were Smith's daughter, Elizabeth Smith Miller, and her husband Charles Dud ...

, grandson

* Gerrit Smith Miller Jr., great-grandson

* Greene Smith

Greene Smith (1842–1886) was an Americans, American amateur scientist and taxidermist with a specific interest in ornithology. His father was Gerrit Smith.

Personal life

Greene Smith was born in 1842. He was the son of Gerrit Smith. He starte ...

, son

References

Notes

* *Further reading (most recent first)

* * * * Wellman, Judith''The Road to Seneca Falls''

University of Illinois Press, 2004. * * * * Frothingham, O. B., ''Gerrit Smith: a Biography'' (New York, 1879). . *

External links

''The Gerrit Smith Virtual Museum'' (New York History Net)

at

The Political Graveyard

The Political Graveyard is a website and database that catalogues information on more than 277,000 American political figures and political families, along with other information. The name comes from the website's inclusion of burial locations of ...

*

* NYHistory.comHistoric Peterboro

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Smith, Gerrit 1797 births 1874 deaths 19th-century American politicians Activists from New York (state) American libertarians Former Presbyterians Free Soil Party members of the United States House of Representatives from New York (state) Hamilton College (New York) alumni Liberty Party (United States, 1840) presidential nominees New York (state) Free Soilers New York (state) Libertyites New York (state) Republicans Politicians from Utica, New York People of New York (state) in the American Civil War American social reformers Underground Railroad people American temperance activists American colonization movement American philanthropists Secret Six American suffragists John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry Underground Railroad in New York (state) Members of the United States House of Representatives from New York (state) People from Peterboro, New York Lake Placid, New York