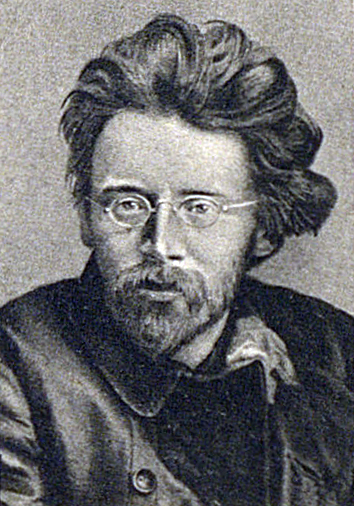

Georgy Pyatakov on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Georgy Leonidovich Pyatakov (; ; 6 August 1890 – 30 January 1937) was a Ukrainian revolutionary and Soviet politician. He was a leading

In October 1914, he and Bosch escaped from exile through

In October 1914, he and Bosch escaped from exile through

After the

After the

From the end of the civil war, in 1920, until 1936, Pyatakov worked as an economic administrator, with short interruptions. From 1920–1921, he was placed in charge of the management of the coal mining industry in the

From the end of the civil war, in 1920, until 1936, Pyatakov worked as an economic administrator, with short interruptions. From 1920–1921, he was placed in charge of the management of the coal mining industry in the

Biography

Mentioning of Leonid Pyatakov

{{DEFAULTSORT:Pyatakov, Georgy 1890 births 1937 deaths Candidates of the Central Committee of the 11th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 12th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 13th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 14th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 16th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 17th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) People from Horodyshche People from Cherkassky Uyezd Russians in Ukraine Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members Old Bolsheviks Left communists Left Opposition Party leaders of the Soviet Union Chairmen of the Board of Gosbank Communist Party of Ukraine (Soviet Union) politicians First secretaries of the Communist Party of Ukraine (Soviet Union) Chairpersons of the Council of Ministers of Ukraine People of the Russian Revolution Russian revolutionaries Russian Revolution in Ukraine GRU officers Cheka Saint Petersburg State University alumni Russian exiles in Siberia Emigrants from the Russian Empire to the United States Emigrants from the Russian Empire to Sweden Emigrants from the Russian Empire to Norway Soviet expatriates in France Trial of the Seventeen Great Purge victims from Russia Soviet rehabilitations Members of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union executed by the Soviet Union Signatories of the Treaty on the Creation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics Trade Representative of the Soviet Union Deputies to the Ukrainian Constituent Assembly Russian Constituent Assembly members Military Opposition

Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

in Ukraine during and after the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution, social change in Russian Empire, Russia, starting in 1917. This period saw Russia Dissolution of the Russian Empire, abolish its mona ...

of 1917.

Born in Kiev Governorate

Kiev Governorate was an administrative-territorial unit ('' guberniya'') of the Russian Empire (1796–1917), Ukrainian People's Republic (1917–18; 1918–1921), Ukrainian State (1918), and the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (1919–19 ...

, Pyatakov was expelled from St Petersburg University in 1910 and later that year joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party (RSDWP) or the Russian Social Democratic Party (RSDP), was a socialist political party founded in 1898 in Minsk, Russian Empire. The ...

. He was arrested in 1912 and exiled to Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

, but in 1914 escaped to Switzerland, where he worked with Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

. Pyatakov returned to Ukraine after the February Revolution

The February Revolution (), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and sometimes as the March Revolution or February Coup was the first of Russian Revolution, two revolutions which took place in Russia ...

of 1917 and was elected the chairman of the party's Kiev committee, and following the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

was elected the first secretary of the Communist Party of Ukraine

The Communist Party of Ukraine (CPU or KPU) is a banned political party in Ukraine. It was founded in 1993 and claimed to be the successor to the Soviet-era Communist Party of Ukraine, which had been banned in 1991. In 2002 it held a "unifi ...

. In 1918, he was part of the Left Communist party faction, and during the civil war served as the first chairman of the Provisional Workers' and Peasants' Government of Ukraine and in several military roles.

From 1923 to 1926, Pyatakov was deputy chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the National Economy

Supreme Soviet of the National Economy, Superior Soviet of the People's Economy, (Высший совет народного хозяйства, ВСНХ, ''Vysshiy sovet narodnogo khozyaystva'', VSNKh) was the superior state institution for mana ...

. In 1927, he was expelled from the party, led by Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

, for his membership in Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ...

's Left Opposition

The Left Opposition () was a faction within the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) from 1923 to 1927 headed '' de facto'' by Leon Trotsky. It was formed by Trotsky to mount a struggle against the perceived bureaucratic degeneration within th ...

, but recanted and rejoined in 1928. Pyatakov was later arrested in 1936, found guilty at the Stalinist show trials

A show trial is a public trial in which the guilt or innocence of the defendant has already been determined. The purpose of holding a show trial is to present both accusation and verdict to the public, serving as an example and a warning to ...

, and executed in 1937.

Biography

Early life and pre-revolution

Pyatakov (party pseudonyms: Kievsky, Lyalin, Petro, Yaponets (Japanese), Ryjii) was born 6 August 1890 in theCherkasy

Cherkasy (, ) is a city in central Ukraine. Cherkasy serves as the administrative centre of Cherkasy Oblast as well as Cherkasy Raion within the oblast. The city has a population of

Cherkasy is the cultural, educational and industrial centre ...

district in the Kiev Governorate

Kiev Governorate was an administrative-territorial unit ('' guberniya'') of the Russian Empire (1796–1917), Ukrainian People's Republic (1917–18; 1918–1921), Ukrainian State (1918), and the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (1919–19 ...

of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

, now modern-day Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

, where his father, Leonid Timofeyevich Pyatakov (1847–1915), was an engineer and director of the large Mariinsky or . Leonid Pyatakov was also the co-owner of Musatov, Pyatakov, Sirotin, and Co.

Pyatakov first became politically active at the age of 14 in secondary school in Kiev. During the 1905 revolution

The Russian Revolution of 1905, also known as the First Russian Revolution, was a revolution in the Russian Empire which began on 22 January 1905 and led to the establishment of a constitutional monarchy under the Russian Constitution of 1906, t ...

, he was expelled for leading a 'school revolution', and joined an anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

group, which carried out armed robberies. In 1907 he was involved in a plot to assassinate the Governor General of Kiev, Vladimir Sukhomlinov, but broke with anarchism that same year and began to study Marxism

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflict, ...

, particularly the writings of Georgi Plekhanov

Georgi Valentinovich Plekhanov ( rus, Георгий Валентинович Плеханов, p=ɡʲɪˈorɡʲɪj vəlʲɪnʲˈtʲinəvʲɪtɕ plʲɪˈxanəf, a=Ru-Georgi Plekhanov-JermyRei.ogg; – 30 May 1918) was a Russian revolutionary, ...

and Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

.

From 1907, he was a student at the Faculty of Economics of St Petersburg University, until he was expelled in 1910, and deported back to Kiev, for taking part in student disturbances. There, he joined the Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

wing of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party (RSDWP) or the Russian Social Democratic Party (RSDP), was a socialist political party founded in 1898 in Minsk, Russian Empire. The ...

. Arrested in June 1912, he spent a year and a half exile

Exile or banishment is primarily penal expulsion from one's native country, and secondarily expatriation or prolonged absence from one's homeland under either the compulsion of circumstance or the rigors of some high purpose. Usually persons ...

d to Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

with his partner, Yevgenia Bosch, in the village of Usolye, Irkutsk

Irkutsk ( ; rus, Иркутск, p=ɪrˈkutsk; Buryat language, Buryat and , ''Erhüü'', ) is the largest city and administrative center of Irkutsk Oblast, Russia. With a population of 587,891 Irkutsk is the List of cities and towns in Russ ...

.

In October 1914, he and Bosch escaped from exile through

In October 1914, he and Bosch escaped from exile through Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

and the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

to Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

, where they joined the émigré

An ''émigré'' () is a person who has emigrated, often with a connotation of political or social exile or self-exile. The word is the past participle of the French verb ''émigrer'' meaning "to emigrate".

French Huguenots

Many French Hugueno ...

revolutionary community, and joined the editorial board of the journal ''Kommunist''. However, during 1915, the Bolshevik group in Switzerland was split over the issue of small nations' rights to national self-determination

Self-determination refers to a people's right to form its own political entity, and internal self-determination is the right to representative government with full suffrage.

Self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international la ...

, which Lenin supported, but Nikolai Bukharin

Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin (; rus, Николай Иванович Бухарин, p=nʲɪkɐˈlaj ɪˈvanəvʲɪdʑ bʊˈxarʲɪn; – 15 March 1938) was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and Marxist theorist. A prominent Bolshevik ...

, Pyatakov, and Bosch opposed. On 30 November 1916, Lenin wrote to his confidant Inessa Armand, complaining that "neither Yuri (Pyatakov), quite a little pig, nor E. B. has a particle of brain, and if they had allowed themselves to descend to group stupidity with Bukharin, then we had to break with them, more precisely with ''Kommunist''. And that was done."

After this breach, Pyatakov, Bukharin, and Bosch moved to Stockholm

Stockholm (; ) is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in Sweden by population, most populous city of Sweden, as well as the List of urban areas in the Nordic countries, largest urban area in the Nordic countries. Approximately ...

, but were expelled from Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

in April 1916 for being present at a conference organised by Swedish socialists to oppose attempts to involve Sweden in World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. They moved to Oslo

Oslo ( or ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Norway. It constitutes both a county and a municipality. The municipality of Oslo had a population of in 2022, while the city's greater urban area had a population of 1,064,235 in 2022 ...

, Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

(then called Kristiania

Oslo ( or ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Norway. It constitutes both a county and a municipality. The municipality of Oslo had a population of in 2022, while the city's greater urban area had a population of 1,064,235 in 2022, an ...

), where they lived in "extreme poverty".

Pyatakov and Bosch remained together until she committed suicide by self-inflicted gunshot in January 1925, after hearing that Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ...

had been forced to resign as leader of the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

, as well as in pain from her heart condition and tuberculosis.

Revolution and Civil War

After the

After the February Revolution

The February Revolution (), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and sometimes as the March Revolution or February Coup was the first of Russian Revolution, two revolutions which took place in Russia ...

, Pyatakov returned to Russia from Norway but was arrested at the border due to having a false passport. He was subsequently escorted to Petrograd

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea. The city had a population of 5,601, ...

, and then finally to Kiev. He lived in Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

from March 1917, becoming a member, then in April, chairman, of the Kiev Committee of the RSDLP. He was elected a of the on 5 August 1917.

For the next ten years, Pyatakov was a leader of the left-wing communists. His opinions on some points of the theory and tactics of the revolutionary struggle were in opposition to that of the party's Central Committee. He was one of Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

's fiercest opponents on the national problem regarding both the course to be followed towards the socialist revolution as well as the Bolsheviks' peace settlement with Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

. After Lenin died in 1924, Pyatakov campaigned to prevent the rise of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

.

During the party conference in Petrograd, in May 1917–at a time of growing support in Finland for independence from Russia– Stalin put forward a motion in favour of self-determination

Self-determination refers to a people's right to form its own political entity, and internal self-determination is the right to representative government with full suffrage.

Self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international la ...

of small nations, which Pyatakov opposed. He declared that the party had to end the idea of self-identification of every nation, and stood for anti- chauvinistic international principles; he proposed that the party adopt the slogan "down with frontiers", which Lenin dismissed as "hopelessly muddled" and a "mess".

After the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

, in November 1917, Lenin called Pyatakov to Petrograd to take over the state bank, whose staff were refusing to release funds for the new government.

In January 1918, Pyatakov was one of the leaders of the Left Communists, who opposed Lenin's decision to end the war with Germany through the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was a separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Soviet Russia and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria), by which Russia withdrew from World War I. The treaty, whi ...

(signed 3 March 1918). In protest, he resigned his post at the state bank and returned to Ukraine, intending to organise partisan warfare against the advancing Imperial German Army

The Imperial German Army (1871–1919), officially referred to as the German Army (), was the unified ground and air force of the German Empire. It was established in 1871 with the political unification of Germany under the leadership of Kingdom o ...

.

At the founding congress of the Communist Party (Bolsheviks) of Ukraine, in Taganrog

Taganrog (, ) is a port city in Rostov Oblast, Russia, on the north shore of Taganrog Bay in the Sea of Azov, several kilometers west of the mouth of the Don (river), Don River. It is in the Black Sea region. Population:

Located at the site of a ...

in July 1918, Pyatakov was elected as Central Committee Secretary. He maintained that Ukraine was not a signatory to the Brest-Litovsk treaty, and could therefore justifiably go to war against Germany. He and his supporters on the left, who included Bosch and Andrei Bubnov

Andrei Sergeyevich Bubnov (; – 1 August 1938) was a Russian Bolshevik revolutionary leader, Soviet Union, Soviet politician and military leader, member of the Left Opposition, and an important Bolshevik figure in Ukraine.

Life

Early career ...

, remained in control of the Ukrainian party during most of 1918, but the insurrection which they launched against the pro-German Hetman

''Hetman'' is a political title from Central and Eastern Europe, historically assigned to military commanders (comparable to a field marshal or imperial marshal in the Holy Roman Empire). First used by the Czechs in Bohemia in the 15th century, ...

, Pavlo Skoropadskyi

Pavlo Petrovych Skoropadskyi (; – 26 April 1945) was a Ukrainian aristocrat, military and state leader, who served as the Hetman of all Ukraine, hetman of the Ukrainian State throughout 1918 following a 1918 Ukrainian coup d'état, coup d'éta ...

, failed.

From November 1918, after the German army withdrew from Ukraine, to mid-January 1919, Pyatakov was a head of the Provisional Worker's and Peasant's Government of Ukraine (). In January 1919 Lenin replaced Pyatakov as head of the Ukrainian government with Christian Rakovsky

Christian Georgiyevich Rakovsky ( – September 11, 1941), Bulgarian name Krastyo Georgiev Rakovski, born Krastyo Georgiev Stanchov, was a Bulgarian-born socialist Professional revolutionaries, revolutionary, a Bolshevik politician and Soviet Un ...

In March 1919, while attending the 8th Congress of the Russian Communist Party, Pyatakov again unsuccessfully opposed Lenin's position on national self-determination

Self-determination refers to a people's right to form its own political entity, and internal self-determination is the right to representative government with full suffrage.

Self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international la ...

, which he denounced as a 'bourgeois' slogan that "unites all counter-revolutionary forces."

Pyatakov collaborated with Nikolai Bukharin

Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin (; rus, Николай Иванович Бухарин, p=nʲɪkɐˈlaj ɪˈvanəvʲɪdʑ bʊˈxarʲɪn; – 15 March 1938) was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and Marxist theorist. A prominent Bolshevik ...

to co-author the chapter on "The Economic Categories of Capitalism in the Transition Period" in ''The Economics of the Transformation Period'', published in 1920.

Pyatakov served as a political commissar with the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

in Ukraine during the Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War () was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the 1917 overthrowing of the Russian Provisional Government in the October Revolution, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. I ...

, and again during the 1920 Polish–Soviet War

The Polish–Soviet War (14 February 1919 – 18 March 1921) was fought primarily between the Second Polish Republic and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, following World War I and the Russian Revolution.

After the collapse ...

. From 1 January to 16 February 1920, he led the Registration Directorate, the Red Army's military intelligence

Military intelligence is a military discipline that uses information collection and analysis List of intelligence gathering disciplines, approaches to provide guidance and direction to assist Commanding officer, commanders in decision making pr ...

arm that went on to become the GRU

Gru is a fictional character and the main protagonist of the ''Despicable Me'' film series.

Gru or GRU may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Gru (rapper), Serbian rapper

* Gru, an antagonist in '' The Kine Saga''

Organizations Georgia (c ...

.

Post-Civil War

From the end of the civil war, in 1920, until 1936, Pyatakov worked as an economic administrator, with short interruptions. From 1920–1921, he was placed in charge of the management of the coal mining industry in the

From the end of the civil war, in 1920, until 1936, Pyatakov worked as an economic administrator, with short interruptions. From 1920–1921, he was placed in charge of the management of the coal mining industry in the Donbas

The Donbas (, ; ) or Donbass ( ) is a historical, cultural, and economic region in eastern Ukraine. The majority of the Donbas is occupied by Russia as a result of the Russo-Ukrainian War.

The word ''Donbas'' is a portmanteau formed fr ...

. In February 1921, he was appointed deputy chairman of the Gosplan

The State Planning Committee, commonly known as Gosplan ( ), was the agency responsible for economic planning, central economic planning in the Soviet Union. Established in 1921 and remaining in existence until the dissolution of the Soviet Unio ...

(State Planning Committee) of the RSFSR

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR or RSFSR), previously known as the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and the Russian Soviet Republic, and unofficially as Soviet Russia,Declaration of Rights of the labo ...

. From 1923–1926, he was deputy Chairman of the Supreme Council of the National Economy of the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

.

From June–August 1922, Pyatakov was chairman of the panel of judges during the Trial of the Socialist Revolutionaries

The Trial of the Socialist Revolutionaries was an internationally publicized political trial in Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Soviet Russia, which brought twelve prominent members of the anti-Bolshevik Socialist Revolutionary Part ...

. At the conclusion of which, he sentenced all 12 defendants to death- though the death sentences were later commuted.

In October 1923, travelling under the name 'Arwid', Pyatakov was part of the Comintern

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern and also known as the Third International, was a political international which existed from 1919 to 1943 and advocated world communism. Emerging from the collapse of the Second Internatio ...

sent to Germany during the abortive attempt to bring about a communist revolution.

Pyatakov was one of only six leading Bolsheviks mentioned in Lenin's Testament

Lenin's Testament is a document alleged to have been dictated by Vladimir Lenin in late 1922 and early 1923, during and after his suffering of multiple strokes. In the testament, Lenin proposed changes to the structure of the Soviet governing bod ...

, dictated in December 1922, during Lenin's terminal illness. The other five-Stalin, Trotsky, Grigory Zinoviev

Grigory Yevseyevich Zinoviev (born Ovsei-Gershon Aronovich Radomyslsky; – 25 August 1936) was a Russian revolutionary and Soviet politician. A prominent Old Bolsheviks, Old Bolshevik, Zinoviev was a close associate of Vladimir Lenin prior to ...

, Lev Kamenev

Lev Borisovich Kamenev. ( Rozenfeld; – 25 August 1936) was a Russian revolutionary and Soviet politician. A prominent Old Bolsheviks, Old Bolshevik, Kamenev was a leading figure in the early Soviet government and served as a Deputy Premier ...

, and Bukharin- were all members of the Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the highest organ of the central committee in communist parties. The term is also sometimes used to refer to similar organs in socialist and Islamist parties, such as the UK Labour Party's NEC or the Poli ...

, while Pyatakov was not even one of the 27 full members of the Central Committee, to which he had been elected a candidate member, for the first time, in April 1922. He became a full member only in May 1924. Lenin described Pyatakov as "a man undoubtedly distinguished in will and ability, but too much given over to administration and the administrative side of things to be relied on in a serious political situation."

Pyatakov supported Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ...

in the power struggle that began during Lenin's terminal illness. He was a signatory of The Declaration of 46 in October 1923, and in the debate that followed he was "their most aggressive and effective spokesman" who "wherever he went easily obtained large majorities for bluntly worded resolutions." But his personal relationship with Trotsky was distant. Simon Liberman, who worked for the Soviet government during part on the 1920s was with Pyatakov in the Crimea, in 1920, and witnessed how he reacted when Trotsky rang:

Despite his support for Trotsky, Pyatakov was anxious that the communist party did not split irreconcilably. After an angry meeting in October 1926, at which Trotsky called Stalin the 'gravedigger of the revolution' to his face, Pyatakov was visibly distressed and demanded of Trotsky "Why, why have you said this?", but Trotsky simply brushed him aside.

In 1927, Pyatakov was sent to Paris as trade representative at the USSR embassy. In December 1927, he was expelled from the Communist Party for belonging to the "Trotskyite–Zinovievite" bloc. He was the first "Trotskyist

Trotskyism (, ) is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Russian revolutionary and intellectual Leon Trotsky along with some other members of the Left Opposition and the Fourth International. Trotsky described himself as an ...

" to renounce Trotskyism. His capitulation was reported in Pravda

''Pravda'' ( rus, Правда, p=ˈpravdə, a=Ru-правда.ogg, 'Truth') is a Russian broadsheet newspaper, and was the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when it was one of the most in ...

on 29 February 1928. For the next eight years he stuck to the party line. This prompted a scathing comment from Trotsky:

When the former Menshevik

The Mensheviks ('the Minority') were a faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with Vladimir Lenin's Bolshevik faction at the Second Party Congress in 1903. Mensheviks held more moderate and reformist ...

, Nikolai Valentinov met Pyatakov in Paris early in 1928 and suggested to him that he has capitulated out of cowardice, Pyatakov riposted with a eulogy about the historic role of the Soviet communist party saying that, for the party, nothing was inadmissible, and nothing impossible, and that a true Bolshevik submerged his personality in the party to the extent that he could break with his own beliefs and honestly agree with the party.

Pyatakov was recalled to Moscow and restored to party membership in 1928. He was deputy chairman of Gosbank in 1928–29, and chairman, 1929–30. After Stalin had ordered the start of the campaign to force peasant farmers to move on to collective farms, Pyatakov gave a speech in October 1929 calling for "extreme rates of collectivisation" and declaring that "the heroic period of our socialist construction has begun."

But in August 1930, Stalin complained in a letter to the head of the soviet government, Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov (; – 8 November 1986) was a Soviet politician, diplomat, and revolutionary who was a leading figure in the government of the Soviet Union from the 1920s to the 1950s, as one of Joseph Stalin's closest allies. ...

that Pyatakov was a "poor commissar" and a "hostage to his bureaucracy". In September, he called him a "genuine rightist Trotskyist" and a "harmful element". Pyatakov was removed from office on 15 October, and appointed head of the All-Union Chemical Industry Association.

In 1932, when the Supreme Economic Council was broken up, and part of it became the People's Commissariat of Heavy Industry of the USSR, Pyatakov was appointed deputy People's Commissar, under Sergo Ordzhonikidze

Sergo Konstantinovich Ordzhonikidze, ; (born Grigol Konstantines dze Orjonikidze; 18 February 1937) was an Old Bolshevik and a Soviet statesman.

Born and raised in Georgia, in the Russian Empire, Ordzhonikidze joined the Bolsheviks at an e ...

. In February 1934, he was restored to full membership of the Central Committee. In October 1935, he chaired the first congress of Stakhanovite

The Stakhanovite movement was a Mass movement (politics), mass cultural movement for Workforce, workers established by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Communist Party in the 1930s Soviet Union. Its promoters encouraged Rationalization (e ...

workers.

Arrest and execution

Pyatakov's wife was arrested July 1936, during the preliminary stage of theGreat Purge

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (), also known as the Year of '37 () and the Yezhovshchina ( , ), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. After the Assassination of Sergei Kirov, assassination of ...

. He was in Kislovodsk at the time, but returned to Moscow, and met Stalin and other senior communists, who told him that several former members of the Left Opposition being held by the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (, ), abbreviated as NKVD (; ), was the interior ministry and secret police of the Soviet Union from 1934 to 1946. The agency was formed to succeed the Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) se ...

had confessed to being part of an anti-soviet conspiracy, and had implicated Pyatakov. He insisted that they were lying. According to what Stalin told a Central Committee plenum six months later, Pyatakov was invited to act as public prosecutor in the forthcoming show trial

A show trial is a public trial in which the guilt (law), guilt or innocence of the defendant has already been determined. The purpose of holding a show trial is to present both accusation and verdict to the public, serving as an example and a d ...

, to which he readily agreed, but, according to Stalin, when told that he would not be suited to the task, he exclaimed: "How can I prove that I am right? Let me! I will personally shoot all those you condemn to be shot. All the bastards!"

This has been taken to imply that Pyatakov was volunteering to shoot his wife, the mother of his children, if she were convicted and condemned to death.

Pyatakov was allowed to put his name to an article that appeared in ''Pravda

''Pravda'' ( rus, Правда, p=ˈpravdə, a=Ru-правда.ogg, 'Truth') is a Russian broadsheet newspaper, and was the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when it was one of the most in ...

'' on 21 August 1936, halfway through the first of the Moscow show trials, in which Zinoviev and Kamenev were lead defendants, declaring: "These people have lost the last semblance of humanity. They must be destroyed like carrion polluting the pure bracing air of the lands of the soviets...", but that evening the prosecutor Andrey Vyshinsky

Andrey Yanuaryevich Vyshinsky (; ) ( – 22 November 1954) was a Soviet politician, jurist and diplomat.

He is best known as a Procurator General of the Soviet Union, state prosecutor of Joseph Stalin's Moscow Trials and in the Nuremberg trial ...

publicly announced that Pyatakov, among others, had been named by the defendants as being involved in 'criminal counter-revolutionary activities, and was under investigation. On 11 September 1936, the Politburo ruled that he was to be expelled from the Central Committee and from the party.

On 12 September 1936, Pyatakov was arrested in his service car at the in Nizhny Tagil

Nizhny Tagil ( rus, Нижний Тагил, p=ˈnʲiʐnʲɪj tɐˈgʲil) is a classification of inhabited localities in Russia, city in Sverdlovsk Oblast, Russia, located east of the Boundaries between the continents#Asia and Europe, boundary ...

. From 23–30 January 1937, he was the lead defendant at the second of the Moscow show trials, the trial of the so-called 'Anti-Soviet Trotskyite Centre', a 'parallel' centre that was supposedly run from abroad by Trotsky with the intention of overthrowing the Soviet government.

At his trial he was accused of conspiring with Trotsky in connection with the case of a so-called Parallel anti-Soviet Party Centre to overthrow the Soviet government in collaboration with Nazi Germany, the latter being promised a reward of large tracts of Soviet territory, including Ukraine. On the opening day of the trial Pyatakov told a story that while he was on an official visit to Berlin in December 1935, he secretly flew by private plane to an airdrome 'in Oslo' where he was taken by car to meet Trotsky, who was in exile in Norway, to receive instructions. This was provably false. Within a few days, Norwegian journalists had established that no aircraft had landed at Oslo's Kjeller airfield in December 1935, nor on any date between September and May. On 30 January 1937, he was sentenced to death, and executed on 1 February.

Pyatakov was posthumously rehabilitated and reinstated in the party on 13 June 1988 by a decision taken under the leadership of Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet and Russian politician who served as the last leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

.

Family

Pyatakov's older brother, Leonid (1888–1917) joined the Bolsheviks in 1916, and in 1917 was elected chairman of the Kiev revolutionary committee. He stayed in Kiev while it was ruled by the Central Rada. He was arrested by Cossacks on 25 December 1917, and was found dead near Kiev on 15 January, his body showing marks of torture. The Rada denied ordering his killing. Their older brother, Mikhail, (1886–1958) joined theConstitutional Democratic Party

The Constitutional Democratic Party (, K-D), also called Constitutional Democrats and formally the Party of People's Freedom (), was a political party in the Russian Empire that promoted Western constitutional monarchy—among other policies� ...

before the Bolshevik revolution. Afterwards, he worked as a scientist. He was arrested three times: in Vladivostok, in 1931; and sentenced to three years' exile; in Baku, in 1939, and sentenced to eight years in labour camps; and in 1948, in Aralsk. He died in Baku.

Their younger brother, Ivan (1893–1937), who worked as an agronomist in Vinnytsia

Vinnytsia ( ; , ) is a city in west-central Ukraine, located on the banks of the Southern Bug. It serves as the administrative centre, administrative center of Vinnytsia Oblast. It is the largest city in the historic region of Podillia. It also s ...

, was shot in 1937.

Their sister, Vera, (1897–1938), who worked as a biologist, was arrested in 1937, and shot.

Pyatakov's second wife, Ludmila Dityateva (1899–1937), whom he married during the civil war, joined the communist party in 1919, was expelled in 1927 as a member of the Left Opposition, and reinstated in 1929. On 11 June 1936, she was appointed the first woman director of the Krasnopresnenskaya Thermal Power Plant in Moscow. Just one and a half months later, she was arrested on 27 July. She was shot on 20 June 1937. She was 'rehabilitated' at the same time as Pyatakov in 1991.

They had three children. Their son, Grigori, born in 1919, changed his name to Proletarsky to avoid being persecuted because of his parents. He died in 2011. Their daughter, Rada, (1923–1942), was sent to an orphanage in 1937 and died during the Siege of Leningrad

The siege of Leningrad was a Siege, military blockade undertaken by the Axis powers against the city of Leningrad (present-day Saint Petersburg) in the Soviet Union on the Eastern Front (World War II), Eastern Front of World War II from 1941 t ...

. Their youngest, Yuri, born 1929, was also sent to an orphanage. His fate is unknown.

Notes

References

External links

Biography

Mentioning of Leonid Pyatakov

{{DEFAULTSORT:Pyatakov, Georgy 1890 births 1937 deaths Candidates of the Central Committee of the 11th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 12th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 13th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 14th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 16th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 17th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) People from Horodyshche People from Cherkassky Uyezd Russians in Ukraine Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members Old Bolsheviks Left communists Left Opposition Party leaders of the Soviet Union Chairmen of the Board of Gosbank Communist Party of Ukraine (Soviet Union) politicians First secretaries of the Communist Party of Ukraine (Soviet Union) Chairpersons of the Council of Ministers of Ukraine People of the Russian Revolution Russian revolutionaries Russian Revolution in Ukraine GRU officers Cheka Saint Petersburg State University alumni Russian exiles in Siberia Emigrants from the Russian Empire to the United States Emigrants from the Russian Empire to Sweden Emigrants from the Russian Empire to Norway Soviet expatriates in France Trial of the Seventeen Great Purge victims from Russia Soviet rehabilitations Members of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union executed by the Soviet Union Signatories of the Treaty on the Creation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics Trade Representative of the Soviet Union Deputies to the Ukrainian Constituent Assembly Russian Constituent Assembly members Military Opposition