George Wishart on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

George Wishart (also Wisehart; c. 15131 March 1546) was a Scottish Protestant Reformer and one of the early Protestant

George Wishart (also Wisehart; c. 15131 March 1546) was a Scottish Protestant Reformer and one of the early Protestant

Stirnet Genealogy: 'Wishart1'

(George is listed as son of Sir James Wyschart of Pittarrow and Elizabeth Learmont)

George Wishart Quincentennial

{{DEFAULTSORT:Wishart, George

1510s births

1546 deaths

16th-century Protestant martyrs

16th-century Calvinist and Reformed ministers

People from Kincardine and Mearns

Scottish Calvinist and Reformed ministers

Alumni of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge

Alumni of the University of Aberdeen

Old University of Leuven alumni

Executed Scottish people

Executed British people

People executed for heresy

People executed by the Kingdom of Scotland by burning

16th-century executions by Scotland

People from Aberdeenshire

Scottish Reformation

People associated with Dundee

Protestant martyrs of Scotland

{{DEFAULTSORT:Wishart, George

1510s births

1546 deaths

16th-century Protestant martyrs

16th-century Calvinist and Reformed ministers

People from Kincardine and Mearns

Scottish Calvinist and Reformed ministers

Alumni of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge

Alumni of the University of Aberdeen

Old University of Leuven alumni

Executed Scottish people

Executed British people

People executed for heresy

People executed by the Kingdom of Scotland by burning

16th-century executions by Scotland

People from Aberdeenshire

Scottish Reformation

People associated with Dundee

Protestant martyrs of Scotland

George Wishart (also Wisehart; c. 15131 March 1546) was a Scottish Protestant Reformer and one of the early Protestant

George Wishart (also Wisehart; c. 15131 March 1546) was a Scottish Protestant Reformer and one of the early Protestant martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an externa ...

s burned at the stake as a heretic

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

.

George Wishart was the son of James and brother of Sir John of Pitarrow, both ranking themselves on the side of the Reformers. He was educated at the University of Aberdeen

The University of Aberdeen ( sco, University o' 'Aiberdeen; abbreviated as ''Aberd.'' in List of post-nominal letters (United Kingdom), post-nominals; gd, Oilthigh Obar Dheathain) is a public university, public research university in Aberdeen, Sc ...

, then recently founded, and travelled afterwards on the Continent. It is thought that it was while he was abroad that he first turned attention to the study of the Reformed doctrines. He engaged for some time in teaching Greek at Montrose. Wishart afterwards proceeded to Cambridge and resided there for about six years, from 1538 to 1543. He returned to Scotland in the train of the Commissioners who had been appointed to arrange a marriage with Prince Edward and the Queen of Scots

The monarch of Scotland was the head of state of the Kingdom of Scotland. According to tradition, the first King of Scots was Kenneth I MacAlpin (), who founded the state in 843. Historically, the Kingdom of Scotland is thought to have grown ...

. He preached to the people with much acceptance at Montrose, Dundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, Dùn Dè or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

, and throughout Ayrshire

Ayrshire ( gd, Siorrachd Inbhir Àir, ) is a historic county and registration county in south-west Scotland, located on the shores of the Firth of Clyde. Its principal towns include Ayr, Kilmarnock and Irvine and it borders the counties of Re ...

. On passing East to the Lothians, Wishart, who spoke latterly as in near prospect of death, was apprehended by Bothwell in the house of Cockburn, of Ormiston

Ormiston is a village in East Lothian, Scotland, near Tranent, Humbie, Pencaitland and Cranston, located on the north bank of the River Tyne at an elevation of about .

The village was the first planned village in Scotland, founded in 1735 ...

. He was carried captive to St. Andrews, where he was tried by a clerical Assembly, found guilty, and condemned as an obstinate heretic. The following day he was executed at the stake on Castle Green, his persecutor, Cardinal David Beaton or Bethune, looking on the scene from the windows of the castle, where he himself would be assassinated within three months.

Life

He belonged to a younger branch of the Wisharts of Pitarrow nearFordoun

Fordoun ( gd, Fordun) (Pronounced "For-Dun") is a parish and village in Aberdeenshire, Scotland. Fothirdun (possibly "the lower place"), as it was historically known, was an important area in the Howe of the Mearns. Fordoun and Auchenblae, t ...

, Kincardineshire. His mother was Elizabeth, sister of Sir James Learmonth, married James Wishart of Pitarrow in April 1512. He was probably called George after his maternal grandfather of granduncle Prior George Leirmont, the name was certainly derived from his mother's family. George's father, James Wishart, died in May 1525, therefore, his mother, Elizabeth together with her brother, Sir James Learmonth of Balcomie, were the two people who were responsible for George's upbringing. Some have suggested that he may have graduated M.A.

A Master of Arts ( la, Magister Artium or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA, M.A., AM, or A.M.) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Tho ...

, probably at King's College, Aberdeen

King's College in Old Aberdeen, Scotland, the full title of which is The University and King's College of Aberdeen (''Collegium Regium Abredonense''), is a formerly independent university founded in 1495 and now an integral part of the Universi ...

, though others, including Wishart biographer Rev. Charles Rogers says that his name does not occur on the records of any Scottish college. He was certainly a student at the University of Leuven, from which he graduated in 1531. Around this time he translated the First Helvetic Confession

The Helvetic Confessions are two documents expressing the common belief of the Calvinist churches of Switzerland.

History

The First Helvetic Confession ( la, Confessio Helvetica prior), known also as the Second Confession of Basel, was drawn up in ...

into English from the Latin. He taught the New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christ ...

in Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

as schoolmaster at Montrose in Angus, until investigated for heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

by the Bishop of Brechin in 1538. He fled to England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, where a similar charge was brought against him at Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

in the following year by Thomas Cromwell

Thomas Cromwell (; 1485 – 28 July 1540), briefly Earl of Essex, was an English lawyer and statesman who served as chief minister to King Henry VIII from 1534 to 1540, when he was beheaded on orders of the king, who later blamed false charge ...

. Under examination by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer (2 July 1489 – 21 March 1556) was a leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He helped build the case for the annulment of Henry' ...

he recanted some utterances. In 1539 or 1540 he may have visited Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

, but by 1542 he had entered Corpus Christi College, Cambridge

Corpus Christi College (full name: "The College of Corpus Christi and the Blessed Virgin Mary", often shortened to "Corpus"), is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. From the late 14th century through to the early 19th century ...

, where he studied and taught.

In 1543 he returned to Scotland, in the train of a Scottish embassy which had come to London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

to consider the treaty of marriage between Prince Edward (later Edward VI of England

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour and the first En ...

) and the infant Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legitimate child of James V of Scot ...

. He returned to Montrose, where again he taught Scripture.

He may have been the "Scottish man called Wishart" acting as a messenger to England for Alexander Crichton of Brunstane

Alexander Crichton of Brunstane, (died before December 1558), was a Scottish Protestant laird who advocated the murder of Cardinal David Beaton and supported the plan for the marriage of Mary, Queen of Scots and Prince Edward of England. In contem ...

in a 1544 plot against Cardinal David Beaton

David Beaton (also Beton or Bethune; 29 May 1546) was Archbishop of St Andrews and the last Scotland, Scottish Cardinal (Catholicism), cardinal prior to the Scottish Reformation, Reformation.

Career

Cardinal Beaton was the sixth and youngest ...

. Some historians such as Alphons Bellesheim Christian Peter "Alphons" Maria Joseph Bellesheim (16 December 1839 Monschau, Germany - 5 February 1912 Aachen, Germany) was a church historian. He also reviewed and collected books.

Family

Alphons was the son of Heinrich "Wilhelm" Ludwig Joseph ...

and Richard Watson Dixon

Richard Watson Dixon (5 May 1833 – 23 January 1900), English poet and divine, son of Dr James Dixon, a Wesleyan minister.

Biography

He was the eldest son of Dr. James Dixon, a distinguished Wesleyan preacher, by Mary, only daughter of the ...

have accepted this identification; others are sceptical. Other possibilities include a George Wishart, Baillie of Dundee, who allied himself with Beaton's murderers; and Sir John Wishart (died 1576), afterwards a Scottish judge.

His career as an itinerant preacher began in 1544, from when he traveled Scotland from east to west. The story has been told by his disciple John Knox

John Knox ( gd, Iain Cnocc) (born – 24 November 1572) was a Scottish minister, Reformed theologian, and writer who was a leader of the country's Reformation. He was the founder of the Presbyterian Church of Scotland.

Born in Giffordgat ...

. He went from place to place, in danger of his life, denouncing the errors of the Papacy

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

and the abuses in the churches of Montrose, Dundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, Dùn Dè or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

(where he escaped an attempt on his life), Ayr

Ayr (; sco, Ayr; gd, Inbhir Àir, "Mouth of the River Ayr") is a town situated on the southwest coast of Scotland. It is the administrative centre of the South Ayrshire Subdivisions of Scotland, council area and the historic Shires of Scotlan ...

, Perth

Perth is the capital and largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia. It is the fourth most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of 2.1 million (80% of the state) living in Greater Perth in 2020. Perth is ...

, Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, Leith

Leith (; gd, Lìte) is a port area in the north of the city of Edinburgh, Scotland, founded at the mouth of the Water of Leith. In 2021, it was ranked by '' Time Out'' as one of the top five neighbourhoods to live in the world.

The earliest ...

, Haddington (where Knox accompanied him) and elsewhere.

At Ormiston

Ormiston is a village in East Lothian, Scotland, near Tranent, Humbie, Pencaitland and Cranston, located on the north bank of the River Tyne at an elevation of about .

The village was the first planned village in Scotland, founded in 1735 ...

in East Lothian

East Lothian (; sco, East Lowden; gd, Lodainn an Ear) is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland, as well as a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area. The county was called Haddingtonshire until 1921.

In 1975, the histo ...

, in January 1546, he was seized by Lord Bothwell on the orders of Cardinal Beaton, taken to Elphinstone Castle, and transferred by order of the privy council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

to Edinburgh castle

Edinburgh Castle is a historic castle in Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland. It stands on Castle Rock (Edinburgh), Castle Rock, which has been occupied by humans since at least the Iron Age, although the nature of the early settlement is unclear. ...

on 19 January 1546. Thence he was handed over to Beaton, who had a "show trial

A show trial is a public trial in which the judicial authorities have already determined the guilt or innocence of the defendant. The actual trial has as its only goal the presentation of both the accusation and the verdict to the public so th ...

", with John Lauder prosecuting Wishart. He was hanged on a gibbet and his body burned at St Andrews

St Andrews ( la, S. Andrea(s); sco, Saunt Aundraes; gd, Cill Rìmhinn) is a town on the east coast of Fife in Scotland, southeast of Dundee and northeast of Edinburgh. St Andrews had a recorded population of 16,800 , making it Fife's fou ...

on 1 March 1546. Foxe and Knox attribute to him a prophecy of the death of the Cardinal, who was assassinated on 29 May following, partly in revenge for Wishart's death.

Wishart's preaching in 1544–45 helped popularise the teachings of Calvin Calvin may refer to:

Names

* Calvin (given name)

** Particularly Calvin Coolidge, 30th President of the United States

* Calvin (surname)

** Particularly John Calvin, theologian

Places

In the United States

* Calvin, Arkansas, a hamlet

* Calvi ...

and Zwingli

Huldrych or Ulrich Zwingli (1 January 1484 – 11 October 1531) was a leader of the Reformation in Switzerland, born during a time of emerging Swiss patriotism and increasing criticism of the Swiss mercenary system. He attended the Unive ...

in Scotland. He translated into English the first '' Helvetic Confession of Faith'' in 1536. At his trial he refused to accept that confession

A confession is a statement – made by a person or by a group of persons – acknowledging some personal fact that the person (or the group) would ostensibly prefer to keep hidden. The term presumes that the speaker is providing information th ...

was a sacrament

A sacrament is a Christianity, Christian Rite (Christianity), rite that is recognized as being particularly important and significant. There are various views on the existence and meaning of such rites. Many Christians consider the sacraments ...

, denied free will

Free will is the capacity of agents to choose between different possible courses of action unimpeded.

Free will is closely linked to the concepts of moral responsibility, praise, culpability, sin, and other judgements which apply only to actio ...

, recognised the priesthood of all believing Christians, and rejected the notion that the infinite God could be "comprehended in one place" between "the priest's hands". He proclaimed that the true Church was where the Word of God was faithfully preached and the two dominical sacrament

A sacrament is a Christianity, Christian Rite (Christianity), rite that is recognized as being particularly important and significant. There are various views on the existence and meaning of such rites. Many Christians consider the sacraments ...

s rightly administered.

Memorials

The Martyrs Memorial atSt Andrews

St Andrews ( la, S. Andrea(s); sco, Saunt Aundraes; gd, Cill Rìmhinn) is a town on the east coast of Fife in Scotland, southeast of Dundee and northeast of Edinburgh. St Andrews had a recorded population of 16,800 , making it Fife's fou ...

was erected to the honour of George Wishart, Patrick Hamilton, and other martyrs of the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

era.

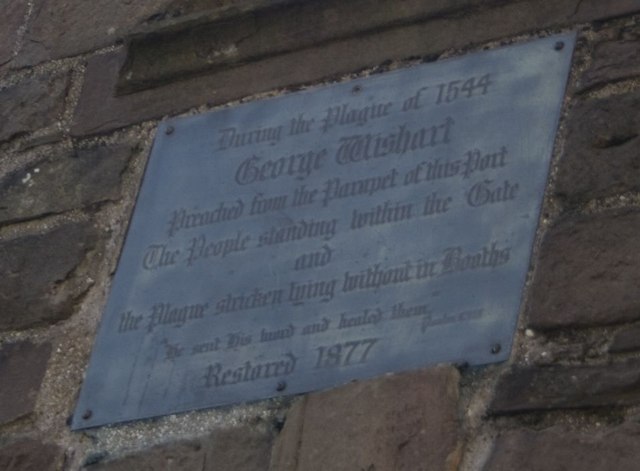

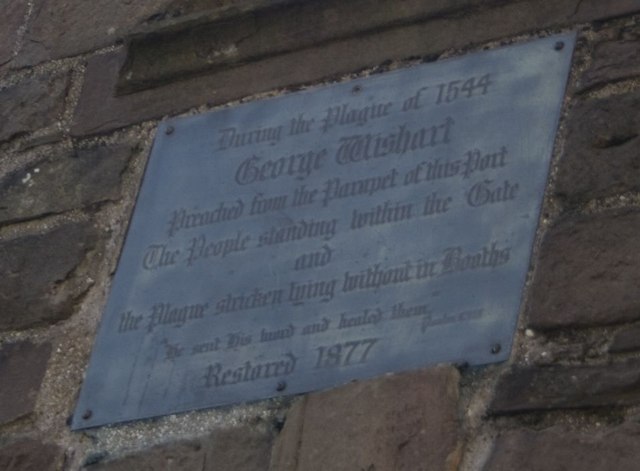

Dundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, Dùn Dè or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

's East Port (also known as Cowgate Port), the remains of a gateway in the town's walls, is known as the Wishart Arch. The Arch is the only surviving portion of the town's walls, and probably survived owing to a story that George Wishart preached from it in 1544 to plague victims. However this story has been described as 'probably-mythical' and the structure is thought to have been built around 1590, long after Wishart's death. Wishart was also commemorated in Dundee with a United Presbyterian church being named after him. Wishart church was built in Dundee' Cowgate in 1841 and could seat over 700 people. It was this church that the missionary Mary Slessor

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a feminine given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religious contexts

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also calle ...

was a member of when she lived in Dundee. It was renamed Wishart Memorial Church in 1901, a year after it had become part of the United Free Church of Scotland

The United Free Church of Scotland (UF Church; gd, An Eaglais Shaor Aonaichte, sco, The Unitit Free Kirk o Scotland) is a Scottish Presbyterian denomination formed in 1900 by the union of the United Presbyterian Church of Scotland (or UP) and ...

, and 1929 became part of the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Scottish Reformation, Reformation of 1560, when it split from t ...

. In 1975 the church congregation was united with Dundee church and the building was sold to Dundee Cyrenians who turned it into a hostel for people with alcohol problems called the Wishart Centre. There is a house at Saint Kentigern College

Saint Kentigern College is a private co-educational Presbyterian secondary school in the suburb of Pakuranga on the eastern side of Auckland, New Zealand, beside the Tamaki Estuary. It is operated by the Saint Kentigern Trust Board which also ...

in Auckland

Auckland (pronounced ) ( mi, Tāmaki Makaurau) is a large metropolitan city in the North Island of New Zealand. The List of New Zealand urban areas by population, most populous urban area in the country and the List of cities in Oceania by po ...

, New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

, named after him. A lodge of the Scottish Orange Order, formed with a warrant in Dundee but often meeting in near by Forfar, is named The Wishart Arch Defenders in his honour.

See also

*Patrick Hamilton (martyr)

Patrick Hamilton (1504 – 29 February 1528) was a Scottish churchman and an early Protestant Reformer in Scotland. He travelled to Europe, where he met several of the leading reformed thinkers, before returning to Scotland to preach. He wa ...

*John Ogilvie (saint)

John Ogilvie (1580 – 10 March 1615) was a Scottish Jesuit martyr. For his work as a priest in service to a persecuted Roman Catholic community in 17th century Scotland, and in being hanged for his faith, he became the only post-Reformation ...

*List of Protestant martyrs of the Scottish Reformation

Two people were executed under heresy laws during the reign of James I of Scotland, James I (1406–1437). Protestants were then executed during persecutions against Protestant religious reformers for their Christian denomination#Protestant Re ...

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * Lady, By a, 'Memorials of the life of George Wishart the Martyr' (St. Andrews: J. Cook & Sons, Printers, 1869) * Cramond's ''Truth about Wishart'' (1898). * Cameron M, et al. (eds), ''Dictionary of Scottish Church History and Theology'' (Edinburgh:T&T Clark

T&T Clark is a British publishing firm which was founded in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1821 and which now exists as an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing.

History

The firm was founded in 1821 by Thomas Clark, then aged 22 and who had a Free Church ...

, 1993).

* Ryrie, Alec, ''The Origins of the Scottish Reformation'' (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2006)

External links

Stirnet Genealogy: 'Wishart1'

(George is listed as son of Sir James Wyschart of Pittarrow and Elizabeth Learmont)

George Wishart Quincentennial

{{DEFAULTSORT:Wishart, George

1510s births

1546 deaths

16th-century Protestant martyrs

16th-century Calvinist and Reformed ministers

People from Kincardine and Mearns

Scottish Calvinist and Reformed ministers

Alumni of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge

Alumni of the University of Aberdeen

Old University of Leuven alumni

Executed Scottish people

Executed British people

People executed for heresy

People executed by the Kingdom of Scotland by burning

16th-century executions by Scotland

People from Aberdeenshire

Scottish Reformation

People associated with Dundee

Protestant martyrs of Scotland

{{DEFAULTSORT:Wishart, George

1510s births

1546 deaths

16th-century Protestant martyrs

16th-century Calvinist and Reformed ministers

People from Kincardine and Mearns

Scottish Calvinist and Reformed ministers

Alumni of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge

Alumni of the University of Aberdeen

Old University of Leuven alumni

Executed Scottish people

Executed British people

People executed for heresy

People executed by the Kingdom of Scotland by burning

16th-century executions by Scotland

People from Aberdeenshire

Scottish Reformation

People associated with Dundee

Protestant martyrs of Scotland