George T. Reynolds on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

George Thomas Reynolds (May 27, 1917 – April 19, 2005) was an American

physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate caus ...

best known for his accomplishments in particle physics

Particle physics or high energy physics is the study of fundamental particles and forces that constitute matter and radiation. The fundamental particles in the universe are classified in the Standard Model as fermions (matter particles) an ...

, biophysics and environmental science

Environmental science is an interdisciplinary academic field that integrates physics, biology, and geography (including ecology, chemistry, plant science, zoology, mineralogy, oceanography, limnology, soil science, geology and physical geograp ...

.

Reynolds received his PhD PHD or PhD may refer to:

* Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), an academic qualification

Entertainment

* '' PhD: Phantasy Degree'', a Korean comic series

* ''Piled Higher and Deeper'', a web comic

* Ph.D. (band), a 1980s British group

** Ph.D. (Ph.D. albu ...

in physics from Princeton

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the nine ...

in 1943, writing a thesis of the propagation of shock wave

In physics, a shock wave (also spelled shockwave), or shock, is a type of propagating disturbance that moves faster than the local speed of sound in the medium. Like an ordinary wave, a shock wave carries energy and can propagate through a med ...

s. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, he joined the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

, and served with the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

. He worked with George Kistiakowsky

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd President ...

on the design of the explosive lenses required by the implosion-type nuclear weapon. He was involved in the investigation of the Port Chicago disaster, served with Project Alberta

Project Alberta, also known as Project A, was a section of the Manhattan Project which assisted in delivering the first nuclear weapons in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II.

Project Alberta was formed in March 19 ...

on Tinian, and was part of the Manhattan Project team sent to Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui h ...

and Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in the ...

to inspect the bomb damage.

After the war, Reynolds began a long academic career at Princeton University. He was director of the Princeton's High Energy Physics Program from 1948 until 1970, when he became the first director of Princeton's new Center for Environmental Studies. He combined his interest in the sea and science by working during the summers at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, where he studied marine bioluminescence

Bioluminescence is the production and emission of light by living organisms. It is a form of chemiluminescence. Bioluminescence occurs widely in marine vertebrates and invertebrates, as well as in some fungi, microorganisms including some b ...

. He also worked at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI, acronym pronounced ) is a private, nonprofit research and higher education facility dedicated to the study of marine science and engineering.

Established in 1930 in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, it i ...

.

Early life

George Thomas Reynolds was born inTrenton, New Jersey

Trenton is the capital city of the U.S. state of New Jersey and the county seat of Mercer County. It was the capital of the United States from November 1 to December 24, 1784.trainmaster for the

Pennsylvania Railroad

The Pennsylvania Railroad (reporting mark PRR), legal name The Pennsylvania Railroad Company also known as the "Pennsy", was an American Class I railroad that was established in 1846 and headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was named ...

, and his wife Laura, a secretary with the New Jersey Department of Geology. Raised in Highland Park, New Jersey from the age of two, he attended Franklin Junior High School

Franklin Junior High School is a public middle school in Franklin, Ohio, part of the Franklin City School District. The building was constructed in 1921 for grades 6-12. In 1948 the building became a four-year high school until 1954, when the Hamp ...

in his hometown through tenth grade and then New Brunswick High School.

He received a bachelor's degree in physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

from Rutgers University

Rutgers University (; RU), officially Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, is a Public university, public land-grant research university consisting of four campuses in New Jersey. Chartered in 1766, Rutgers was originally called Queen's ...

in 1939. He then entered Princeton University

Princeton University is a private university, private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial Colleges, fourth-oldest ins ...

, where was awarded a Master of Science

A Master of Science ( la, Magisterii Scientiae; abbreviated MS, M.S., MSc, M.Sc., SM, S.M., ScM or Sc.M.) is a master's degree in the field of science awarded by universities in many countries or a person holding such a degree. In contrast to ...

degree in 1942. He earned his PhD PHD or PhD may refer to:

* Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), an academic qualification

Entertainment

* '' PhD: Phantasy Degree'', a Korean comic series

* ''Piled Higher and Deeper'', a web comic

* Ph.D. (band), a 1980s British group

** Ph.D. (Ph.D. albu ...

in 1943 under the supervision of Walker Bleakney

Walker Bleakney (February 8, 1901 – January 15, 1992) was an American physicist, one of inventors of mass spectrometers, and widely noted for his research in the fields of atomic physics, molecular physics, fluid dynamics, the ionization of g ...

, writing his thesis "Studies in the production, propagation, and interactions of shock waves".

Manhattan Project

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

was raging at this time, and someone with a doctorate in such a topic area was highly sought after by the wartime Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

, but Reynolds turned down an offer to join it. An avid surf fisherman and sailor, he aspired to join the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

. He attempted to enlist, but was turned down because he wore glasses. He then lobbied the Navy, which waived this requirement. He was then commissioned as an ensign in 1943, and married Virginia Rendall, a librarian, while he waited for his first assignment.

Instead of the seafaring assignment he hoped for, Reynolds was sent to the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos Laboratory to assist George Kistiakowsky

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd President ...

in the design of the explosive lenses required by the implosion-type nuclear weapon. In April 1944, Kistiakowsky named Reynolds as one of eleven men that he would like to have working for him at Los Alamos.

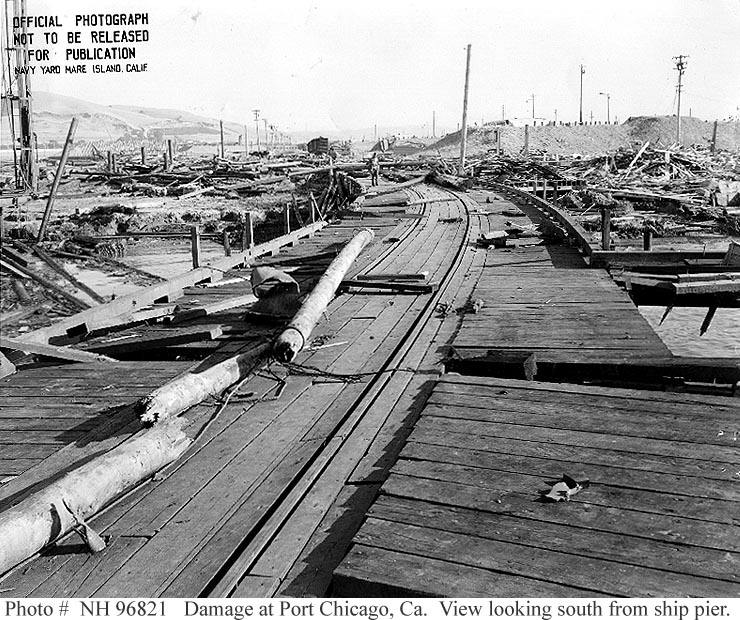

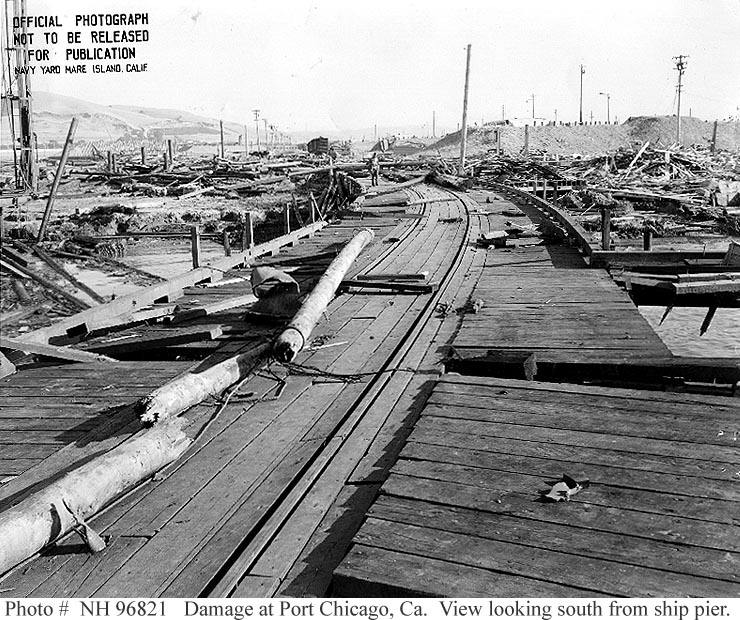

Reynolds was one of the naval officers who was sent to investigate the Port Chicago disaster, in which an ammunition ship had blown up in the harbor. He was tasked with estimating the size of the explosion, based upon observations of the damage. His estimate was ± tons. A bill of lading was subsequently found for 1,540 tons, confirming his estimate.

Reynolds was one of several researchers who determined that an atomic bomb would do maximum damage if detonated in the air rather than at ground level.

He later served with Project Alberta

Project Alberta, also known as Project A, was a section of the Manhattan Project which assisted in delivering the first nuclear weapons in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II.

Project Alberta was formed in March 19 ...

, the part of the Manhattan Project for operations in the field. He served on Tinian, where the worked with the X-Unit Section, which was responsible for the Fat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) is the codename for the type of nuclear bomb the United States detonated over the Japanese city of Nagasaki on 9 August 1945. It was the second of the only two nuclear weapons ever used in warfare, the fir ...

bomb's firing unit. He flew a number of practice missions, but not the bombing of Hiroshima or Nagasaki. After the fighting ended, he was part of the Manhattan Project team sent to Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui h ...

and Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in the ...

to inspect the bomb damage.

Princeton

After the war, Reynolds accepted an offer of an assistant professorship at Princeton University. He would spend the rest of his career there, being promoted to associate professor in 1951, and then to professor in 1959. John Archibald Wheeler interested him incosmic ray

Cosmic rays are high-energy particles or clusters of particles (primarily represented by protons or atomic nuclei) that move through space at nearly the speed of light. They originate from the Sun, from outside of the Solar System in our own ...

s. Reybolds was director of Princeton's high-energy physics program from 1948 to 1970. He initially recruited Ronald Rau from Caltech and Joseph Ballam from the University of California. Ballam eventually became a professor and division head at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, while Rau went on to become chairman of the physics department at the Brookhaven National Laboratory. Reynolds later hired Sam Treiman, Giorgio Salvini

Giorgio Salvini (24 April 1920 – 8 April 2015) was an Italian physicist and politician. Life

Born in Milan, in 1953 Salvini was responsible for the construction of the first Italian circular particle accelerator, the electron synchrotron of Fra ...

, Riccardo Giacconi

Riccardo Giacconi ( , ; October 6, 1931 – December 9, 2018) was an Italian-American Nobel Prize-winning astrophysicist who laid down the foundations of X-ray astronomy. He was a professor at the Johns Hopkins University.

Biography

Born in ...

, Val Fitch

Val Logsdon Fitch (March 10, 1923 – February 5, 2015) was an American nuclear physicist who, with co-researcher James Cronin, was awarded the 1980 Nobel Prize in Physics for a 1964 experiment using the Alternating Gradient Synchrotron at Broo ...

and Jim Cronin. His reputation for spotting and hiring talent was assured when Giacconi, Fitch and Cronin won Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

s.

For his cosmic ray research, Reynolds attempted to grow large organic crystal scintillators to use as ionized particle detectors. Scintillators are luminescent materials that, when struck by an incoming particle, absorb its energy and scintillate – emit light. They are used in many areas of scientific research. He was frustrated by cracks in the crystals, and attempted to get around the problem by dissolving them in liquid. To the surprise of many, the liquid was just as effective as crystal scintillators. Today, liquid scintillators are in widespread use in nuclear, biological and medical research. He also developed automated X-ray detectors for collecting data on protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

structures.

Interest in environmental issues increased in the late 1960s, and in 1970, Princeton established Princeton's Center for Environmental Studies. Reynolds was appointed as its first director. Under his leadership, it investigated a number of unusual inter-disciplinary topics, such as energy conservation in buildings, indoor air quality, the relationship between nuclear power and nuclear weapons, and the decision-making process in environmental issues

Although most of his career was at Princeton, he spent some time in England, where was a Churchill Fellow

Winston Churchill Memorial Trusts (WCMT) are three independent but related living memorials to Sir Winston Churchill, based in the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand. They exist for the purpose of administering Churchill Fellowships, a ...

at Cambridge University

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

in 1973 and 1974. He was later a visiting senior research fellow at the laboratory of molecular biology at Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, and a visiting professor at Oxford Research Unit of the Open University

The Open University (OU) is a British public research university and the largest university in the United Kingdom by number of students. The majority of the OU's undergraduate students are based in the United Kingdom and principally study off- ...

, from 1981 to 1982, and a Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

Guest Research Fellow at Oxford University in 1985.

Reynolds became the Class of 1909 Professor of Physics in 1978, and professor emeritus

''Emeritus'' (; female: ''emerita'') is an adjective used to designate a retired chair, professor, pastor, bishop, pope, director, president, prime minister, rabbi, emperor, or other person who has been "permitted to retain as an honorary title ...

1987. For 31 years he combined his interest in the sea and science by working during the summer at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, where he studied marine bioluminescence

Bioluminescence is the production and emission of light by living organisms. It is a form of chemiluminescence. Bioluminescence occurs widely in marine vertebrates and invertebrates, as well as in some fungi, microorganisms including some b ...

. He also worked at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI, acronym pronounced ) is a private, nonprofit research and higher education facility dedicated to the study of marine science and engineering.

Established in 1930 in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, it i ...

.

Reynolds died from cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Possible signs and symptoms include a lump, abnormal b ...

at his home in the Skillman section of Montgomery Township, New Jersey

Montgomery Township is a Township (New Jersey), township in southern Somerset County, New Jersey, Somerset County, New Jersey, United States. It is located in the New York Metropolitan Area. As of the 2020 United States Census, the township’s ...

, on April 19, 2005. He was survived by his wife, Virginia, and his four sons, G. Thomas, Richard, Robert and David.

References

Bibliography

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Reynolds, George 1917 births 2005 deaths People from Highland Park, New Jersey People from Montgomery Township, New Jersey People from Trenton, New Jersey Princeton University alumni Rutgers University alumni 20th-century American physicists Manhattan Project people New Brunswick High School alumni Princeton University faculty Physicists from New Jersey United States Navy officers Military personnel from New Jersey