George Rogers Clark on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

George Rogers Clark (November 19, 1752 – February 13, 1818) was an American surveyor, soldier, and militia officer from

Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the East Coast of the United States, Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography an ...

who became the highest-ranking American patriot military officer on the northwestern frontier during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of ...

. He served as leader of the militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non- professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

in Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virgini ...

(then part of Virginia) throughout much of the war. He is best known for his captures of Kaskaskia

The Kaskaskia were one of the indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands. They were one of about a dozen cognate tribes that made up the Illiniwek Confederation, also called the Illinois Confederation. Their longstanding homeland was in th ...

(1778) and Vincennes (1779) during the Illinois Campaign, which greatly weakened British influence in the Northwest Territory. The British ceded the entire Northwest Territory to the United States in the 1783 Treaty of Paris

The Treaty of Paris, signed in Paris by representatives of King George III of Great Britain and representatives of the United States of America on September 3, 1783, officially ended the American Revolutionary War and overall state of conflict ...

, and Clark has often been hailed as the "Conqueror of the Old Northwest".

Clark's major military achievements occurred before his thirtieth birthday. Afterward, he led militia in the opening engagements of the Northwest Indian War, but was accused of being drunk on duty. He was disgraced and forced to resign, despite his demand for a formal investigation into the accusations. He left Kentucky to live on the Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th ...

frontier but was never fully reimbursed by Virginia for his wartime expenditures. During the final decades of his life, he worked to evade creditors and suffered living in increasing poverty and obscurity. He was involved in two failed attempts to open the Spanish-controlled Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it ...

to American traffic. After suffering a stroke and the amputation of his right leg, he became an invalid. He was aided in his final years by family members, including his younger brother William

William is a masculine given name of Norman French origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conq ...

, one of the leaders of the Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery Expedition, was the United States expedition to cross the newly acquired western portion of the country after the Louisiana Purchase. The Corps of Discovery was a select gr ...

. He died of a stroke on February 13, 1818.

Early years

George Rogers Clark was born on November 19, 1752, in Albemarle County, Virginia, near Charlottesville, the hometown ofThomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the nati ...

. He was the second of 10 children of John and Ann Rogers Clark, who were Anglicans

Anglicanism is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Euro ...

of English and possibly Scottish ancestry. Five of their six sons became officers during the American Revolutionary War. Their youngest son William

William is a masculine given name of Norman French origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conq ...

was too young to fight in the war, but he later became famous as a leader of the Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery Expedition, was the United States expedition to cross the newly acquired western portion of the country after the Louisiana Purchase. The Corps of Discovery was a select gr ...

. The family moved from the Virginia frontier to Caroline County, Virginia

Caroline County is a United States county located in the eastern part of the Commonwealth of Virginia. The northern boundary of the county borders on the Rappahannock River, notably at the historic town of Port Royal. The Caroline county seat ...

, around 1756, after the outbreak of the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the st ...

. They lived on a plantation that they later developed to a total of more than .

Clark had little formal education. He lived with his grandfather so that he could receive a common education at Donald Robertson's school, where fellow students included James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for h ...

and John Taylor of Caroline. He was also tutored at home, as was usual for the children of Virginia planters in this period. There was no public education. His grandfather trained him to be a surveyor.

In 1771 at age 19, Clark left his home on his first surveying trip into western Virginia. In 1772, he made his first foray into Kentucky via the Ohio River at Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

and spent the next two years surveying the Kanawha River region, as well as learning about the area's natural history and customs of the various tribes of Indians

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

who lived there. In the meantime, thousands of settlers were entering the area as a result of the Treaty of Fort Stanwix of 1768, by which some of the tribes had agreed to peace.

Clark's military career began in 1774, when he served as a captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

in the Virginia militia. He was preparing to lead an expedition of 90 men down the Ohio River when hostilities broke out between the Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

and settlers on the Kanawha frontier; this conflict eventually culminated in Lord Dunmore's War. Most of Kentucky was not inhabited by Indians, although such tribes as the Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

, Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, th ...

, and Seneca (of the Iroquois Confederacy) used the area for hunting. Tribes in the Ohio country who had not been party to the treaty signed with the Cherokee were angry, because the Kentucky hunting grounds had been ceded without their approval. As a result, they tried to resist encroachment by the American settlers, but were unsuccessful. Clark spent a few months surveying in Kentucky, as well as assisting in organizing Kentucky as a county for Virginia prior to the American Revolutionary War.

Revolutionary War

As the American Revolutionary War began in the East, Kentucky's settlers became involved in a dispute about the region's sovereignty. Richard Henderson, a judge and land speculator fromNorth Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia a ...

, had purchased much of Kentucky from the Cherokee by an illegal treaty. Henderson intended to create a proprietary colony

A proprietary colony was a type of English colony mostly in North America and in the Caribbean in the 17th century. In the British Empire, all land belonged to the monarch, and it was his/her prerogative to divide. Therefore, all colonial proper ...

known as Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the ...

, but many Kentucky settlers did not recognize Transylvania's authority over them. In June 1776, these settlers selected Clark and John Gabriel Jones

John Gabriel Jones (June 6, 1752 – December 25, 1776) was a colonial American pioneer and politician. An early settler of Kentucky, he and George Rogers Clark sought to petition Virginia to allow Kentucky to become a part of the Colony of Vir ...

to deliver a petition to the Virginia General Assembly

The Virginia General Assembly is the legislative body of the Commonwealth of Virginia, the oldest continuous law-making body in the Western Hemisphere, the first elected legislative assembly in the New World, and was established on July 30, 1 ...

, asking Virginia to formally extend its boundaries to include Kentucky.

Clark and Jones traveled the Wilderness Road to Williamsburg

Williamsburg may refer to:

Places

*Colonial Williamsburg, a living-history museum and private foundation in Virginia

*Williamsburg, Brooklyn, neighborhood in New York City

*Williamsburg, former name of Kernville (former town), California

*Williams ...

, where they convinced Governor Patrick Henry

Patrick Henry (May 29, 1736June 6, 1799) was an American attorney, planter, politician and orator known for declaring to the Second Virginia Convention (1775): " Give me liberty, or give me death!" A Founding Father, he served as the first ...

to create Kentucky County, Virginia. Clark was given of gunpowder to help defend the settlements and was appointed a major in the Kentucky County militia. Although he was only 24 years old, older settlers such as Daniel Boone

Daniel Boone (September 26, 1820) was an American pioneer and frontiersman whose exploits made him one of the first folk heroes of the United States. He became famous for his exploration and settlement of Kentucky, which was then beyond the w ...

, Benjamin Logan, and Leonard Helm considered him a leader.

Illinois campaign

In 1777, the Revolutionary War intensified in Kentucky. Lieutenant-governor Henry Hamilton, based at Fort Detroit, provided weapons to his Indian allies, supporting their raids on settlers in hope of reclaiming their lands. The Continental Army could spare no men for an invasion in the northwest or for the defense of Kentucky, which was left entirely to the local population. Clark spent several months defending settlements against the Indian raiders as a leader in the Kentucky County militia, while developing his plan for a long-distance strike against the British. His strategy involved seizing British outposts north of the Ohio River to destroy British influence among their Indian allies. In December 1777, Clark presented his plan to Virginia's Governor Patrick Henry, and he asked for permission to lead a secret expedition to capture the British-held villages atKaskaskia

The Kaskaskia were one of the indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands. They were one of about a dozen cognate tribes that made up the Illiniwek Confederation, also called the Illinois Confederation. Their longstanding homeland was in th ...

, Cahokia, and Vincennes in the Illinois country. Governor Henry commissioned him as a lieutenant colonel in the Virginia militia and authorized him to raise troops for the expedition. Clark and his officers recruited volunteers from Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; (Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, Ma ...

, Virginia, and North Carolina. Clark arrived at Redstone, a settlement on the Monongahela River south of Fort Pitt on February 1, where he made preparations for the expedition over the next several months. The men gathered at Redstone and the regiment departed from there on May 12, proceeding on boats down the Monongahela to Fort Pitt to take on supplies and then down the Ohio to Fort Henry and on to Fort Randolph at the mouth of the Kanawha. They reached the Falls of the Ohio in early June where they spent about a month along the Ohio River preparing for their secret mission.

In July 1778, Clark led the Illinois Regiment of the Virginia militia of about 175 men and crossed the Ohio River at Fort Massac and marched to Kaskaskia

The Kaskaskia were one of the indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands. They were one of about a dozen cognate tribes that made up the Illiniwek Confederation, also called the Illinois Confederation. Their longstanding homeland was in th ...

, capturing it on the night of July 4 without firing their weapons. The next day, Captain Joseph Bowman and his company captured Cahokia in a similar fashion without firing a shot. The garrison at Vincennes along the Wabash River surrendered to Clark in August. Several other villages and British forts were subsequently captured, after British hopes of local support failed to materialize. To counter Clark's advance, Hamilton recaptured the garrison at Vincennes, which the British called Fort Sackville, with a small force in December 1778.

Prior to initiating a march on Fort Detroit, Clark used his own resources and borrowed from his friends to continue his campaign after the initial appropriation had been depleted from the Virginia legislature. He re-enlisted some of his troops and recruited additional men to join him. Hamilton waited for spring to begin a campaign to retake the forts at Kaskaskia and Cahokia, but Clark planned another surprise attack on Fort Sackville at Vincennes. He left Kaskaskia on February 6, 1779, with about 170 men, beginning an arduous overland trek, encountering melting snow, ice, and cold rain along the journey. They arrived at Vincennes on February 23 and besieged Fort Sackville. After a siege which included the killing of 5 captive Indians on Clark's orders to intimidate the British, Hamilton surrendered the garrison on February 25 and was captured in the process. The winter expedition was Clark's most significant military achievement and became the basis of his reputation as an early American military hero.

News of Clark's victory reached General George Washington, and his success was celebrated and was used to encourage the alliance with France. General Washington recognized that Clark's achievement had been gained without support from the regular army, either in men or funds. Virginia also capitalized on Clark's success, laying claim to the Old Northwest by calling it Illinois County, Virginia.

Final years of the war

Clark's ultimate goal during the Revolutionary War was to seize the British-held fort at Detroit, but he could never recruit enough men and acquire sufficient munitions to make the attempt. Kentucky militiamen generally preferred to defend their own territory and stay closer to home, rather than make the long and potentially perilous expedition to Detroit. Clark returned to the Falls of the Ohio andLouisville, Kentucky

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana borde ...

, where he continued to defend the Ohio River valley until the end of the war.

In June 1780, a mixed force of British and Indians from the Detroit area, including Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

, Delaware (Lenape)

The Lenape (, , or Lenape , del, Lënapeyok) also called the Leni Lenape, Lenni Lenape and Delaware people, are an indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands, who live in the United States and Canada. Their historical territory includ ...

, and Wyandot, invaded Kentucky. They captured two fortified settlements and seized hundreds of prisoners. In August 1780, Clark led a retaliatory force that won a victory at the Shawnee village of '' Peckuwe.'' It has been commemorated as George Rogers Clark Park near Springfield, Ohio

Springfield is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Clark County. The municipality is located in southwestern Ohio and is situated on the Mad River, Buck Creek, and Beaver Creek, approximately west of Columbus and northe ...

.

In 1781, Virginia Governor Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the nati ...

promoted Clark to brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed t ...

and gave him command of all the militia in the Kentucky and Illinois counties. As Clark prepared to lead another expedition against the British and their allies in Detroit, General Washington transferred a small group of regulars to assist, but the detachment was disastrously defeated in August 1781 before they could meet up with Clark. This ended the western campaign.

In August 1782, another British-Indian force defeated the Kentucky militia at the Battle of Blue Licks. Clark was the militia's senior military officer, but he had not been present at the battle and was severely criticized in the Virginia Council for the disaster. In response November 1782, Clark led another expedition into the Ohio country, destroying several Indian villages along the Great Miami River, including the Shawnee village of Piqua, Miami County, Ohio. This was the last major expedition of the war.

The importance of Clark's activities during the Revolutionary War has been the subject of much debate among historians. As early as 1779 George Mason

George Mason (October 7, 1792) was an American planter, politician, Founding Father, and delegate to the U.S. Constitutional Convention of 1787, one of the three delegates present who refused to sign the Constitution. His writings, including s ...

called Clark the "Conqueror of the Northwest." Because the British ceded the entire Old Northwest Territory to the United States in the Treaty of Paris, some historians, including William Hayden English, credit Clark with nearly doubling the size of the original thirteen colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th cent ...

when he seized control of the Illinois country during the war. Clark's Illinois campaign—particularly the surprise march to Vincennes—was greatly celebrated and romanticized.

More recent scholarship from historians such as Lowell Harrison has downplayed the importance of the campaign in the peace negotiations and the outcome of the war, arguing that Clark's "conquest" was little more than a temporary occupation of territory. Although the Illinois campaign is frequently described in terms of a harsh, winter ordeal for the Americans, James Fischer points out that the capture of Kaskaskia and Vincennes may not have been as difficult as previously suggested. Kaskaskia proved to be an easy target; Clark had sent two spies there in June 1777, who reported "an absence of soldiers in the town."

Clark's men also easily captured Vincennes and Fort Sackville. Prior to their arrival in 1778, Clark had sent Captain Leonard Helm to Vincennes to gather intelligence. In addition, Father Pierre Gibault, a local priest, helped persuade the town's inhabitants to side with the Americans. Before Clark and his men set out to recapture Vincennes in 1779, Francis Vigo

Francis may refer to:

People

*Pope Francis, the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State and Bishop of Rome

*Francis (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

*Francis (surname)

Places

*Rural Mu ...

provided Clark with additional information on the town, its surrounding area, and the fort. Clark was already aware of the fort's military strength, poor location (surrounded by houses that could provide cover to attackers), and dilapidated condition. Clark's strategy of a surprise attack and strong intelligence were critical in catching Hamilton and his men unaware and vulnerable. After killing five captive Indians by hatchet within view of the fort, Clark forced its surrender.

Later years

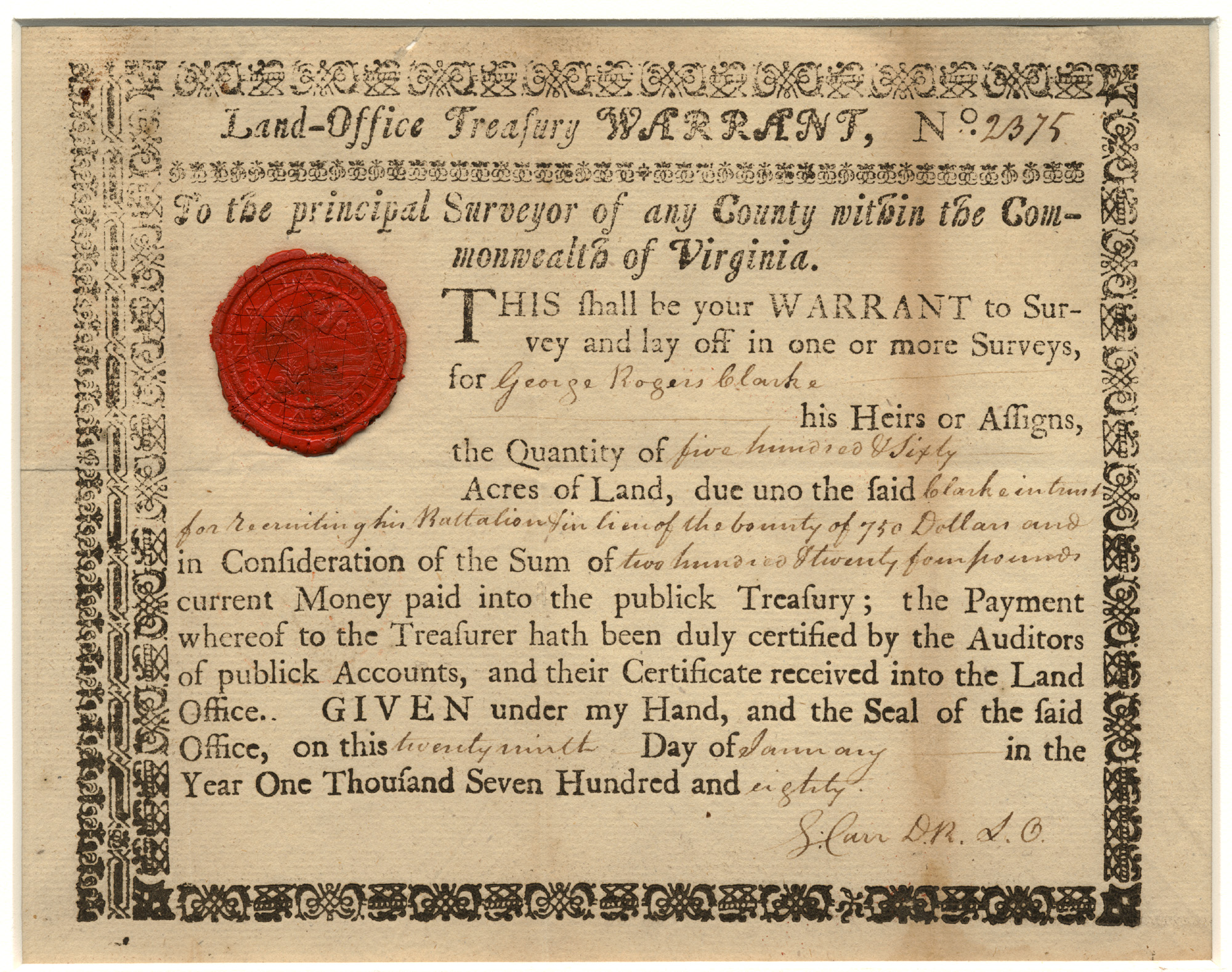

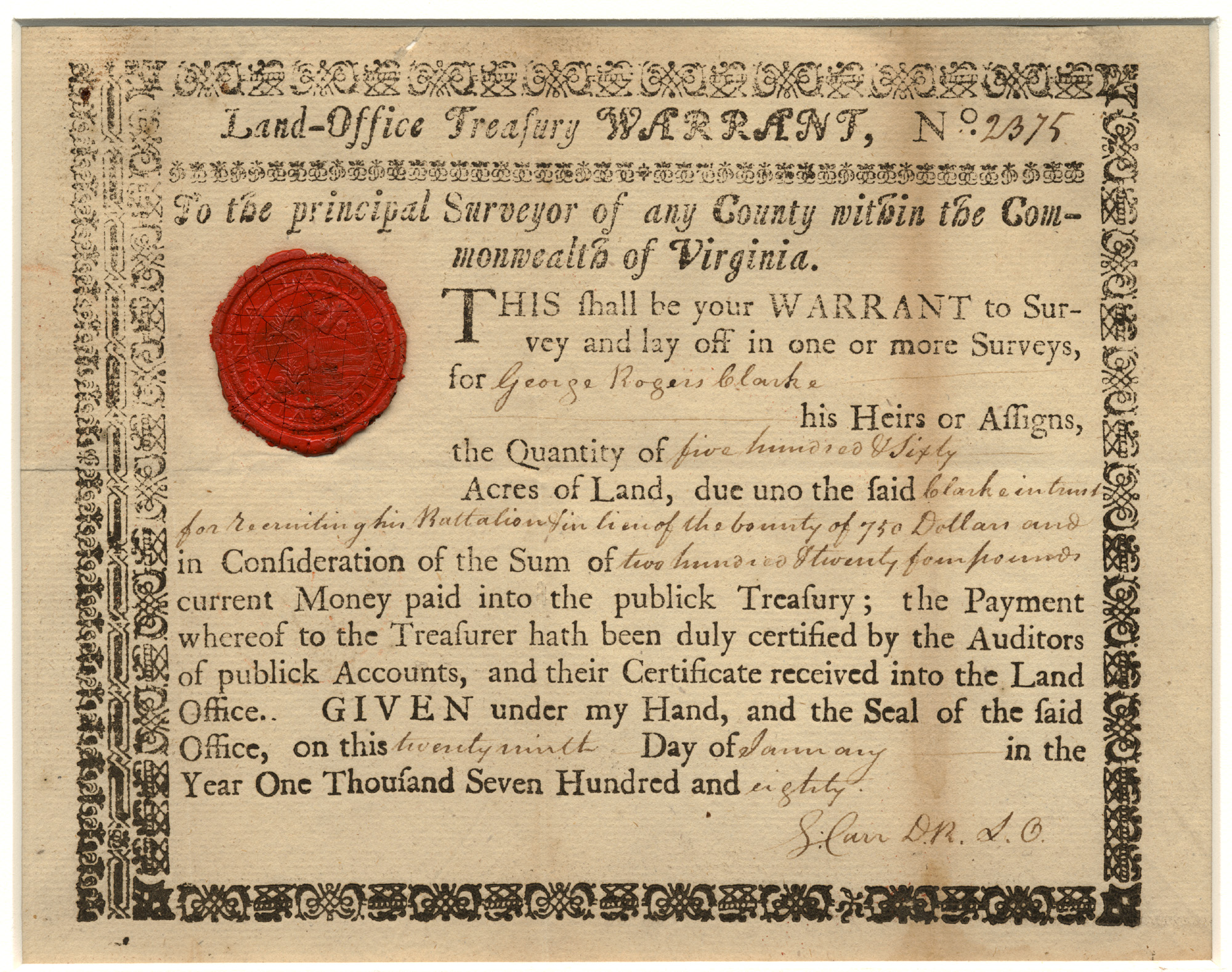

After Clark's victories in the Illinois country, settlers continued to pour into Kentucky and spread into and develop the land north of the Ohio River. On December 17, 1783, was Clark appointed Principal Surveyor of Bounty Lands. From 1784 to 1788 Clark served as the superintendent-surveyor for Virginia's war veterans, surveying lands granted to them for their service in the war. The position brought Clark a small income, but he devoted very little time to the enterprise. In 1785 Clark helped to negotiate the Treaty of Fort McIntosh and the Treaty of Fort Finney in 1786, but the violence between Native Americans and European-American settlers continued to escalate. According to a 1790 U.S. government report, 1,500 Kentucky settlers had been killed in Indian raids since the end of the Revolutionary War. In an attempt to end the raids, Clark led an expedition of 1,200 drafted men against Native American villages along the Wabash River in 1786. The campaign, one of the first actions of the Northwest Indian War, ended without a victory. After approximately three hundred militiamen mutinied due to a lack of supplies, Clark had to withdraw, but not before concluding a ceasefire with the native tribes. It was rumored, most notably by James Wilkinson, that Clark had often been drunk on duty. When Clark learned of the accusations, he demanded an official inquiry, but the Virginia governor declined his request and Virginia Council condemned Clark's actions. With Clark's reputation tarnished, he never again led men in battle. Clark left Kentucky and moved across the Ohio River to theIndiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th ...

frontier, near present-day Clarksville, Indiana.

Life in Indiana

Following his military service, and especially after 1787, Clark spent much of the remainder of his life dealing with financial difficulties. Clark had financed the majority of his military campaigns with borrowed funds. When creditors began pressuring him to repay his debts, Clark was unable to obtain reimbursement from Virginia or theUnited States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washi ...

. Due to haphazard record keeping on the frontier during the war, Virginia refused payment, claiming that Clark's receipts for his purchases were "fraudulent".

As compensation for his wartime service, Virginia gave Clark a gift of of land that became known as Clark's Grant in present-day southern Indiana, while the soldiers who fought with Clark also received smaller tracts of land. Clark's Grant and his other holdings gave Clark ownership of land that encompassed present-day Clark County, Indiana

Clark County is a county in the U.S. state of Indiana, located directly across the Ohio River from Louisville, Kentucky. At the 2020 census, the population was 121,093. The county seat is Jeffersonville. Clark County is part of the Louisvil ...

, and portions of adjoining Floyd and Scott

Scott may refer to:

Places Canada

* Scott, Quebec, municipality in the Nouvelle-Beauce regional municipality in Quebec

* Scott, Saskatchewan, a town in the Rural Municipality of Tramping Lake No. 380

* Rural Municipality of Scott No. 98, Saska ...

Counties.Madison, ''Hoosiers'', p. 27 Although Clark had claims to tens of thousands of acres of land, the result of his military service and land speculation, he was "land-poor," meaning that he owned much land but lacked the resources to develop it. George Rogers Clark's Receipts were discovered in the Richmond Virginia's Auditors building,in the early Nineteen hundreds and that his records keeping efforts were Complete and correct but not reimbursed due to the State of Virginia's incompetencies, thus GRC WAS fully exhonerated in truth but not officially.e his memoirs around 1791, but they were not published during his lifetime. Although the autobiography contains factual inaccuracies, the work includes Clark's perspective on the events of his life. Some historians believe Clark wrote his memoirs in attempt to salvage his damaged reputation and to document his contributions during the Revolutionary War.

In the service of the French

On February 2, 1793, with his career seemingly over and his prospects for prosperity doubtful, Clark offered his services to Edmond-Charles Genêt, the controversial ambassador ofrevolutionary France

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

, hoping to earn money to maintain his estate. Western Americans were outraged that the Spanish, who controlled Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a U.S. state, state in the Deep South and South Central United States, South Central regions of the United States. It is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 20th-smal ...

, denied Americans free access to the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it ...

, their only easy outlet for long-distance commerce. The Washington administration was also unresponsive to western matters.

Genêt appointed Clark "Major General in the Armies of France and Commander-in-chief of the French Revolutionary Legion

The French Revolutionary Legion on the Mississippi was an American mercenary force commissioned by leaders of Revolutionary France in 1793. Its purpose was to reassert French influence in the North American interior, which was lost in the Treaty ...

on the Mississippi River". Clark began to organize a campaign to seize New Madrid, St. Louis, Natchez, and New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

John Montgomery, and winning the tacit support of Kentucky governor Isaac Shelby. Clark spent $4,680 () of his own money for supplies.

In early 1794, however, President Washington issued a proclamation forbidding Americans from violating U.S. neutrality and threatened to dispatch General

, Fort Campbell website, accessed October 11, 2008 and Clarksburg, West Virginia.

* Schools named in Clark's honor include: ** George Rogers Clark Elementary School of

Patrick Henry's Secret Orders to Clark

dated January 2, 1778 – Indiana Historical Society

*

Indiana Historical Bureau

Indiana Historical Bureau

Clark Family Papers

– Missouri History Museum Archives *

"The Clarks: The First Family of the Frontier,"

8thVirginia.com. *

Guide to the Reuben T. Durrett Collection of George Rogers Clark Papers 1776-1896

at th

University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center

{{DEFAULTSORT:Clark, George Rogers 1752 births 1818 deaths American people of the Northwest Indian War Burials at Cave Hill Cemetery Clark County, Ohio Clarksburg, West Virginia Clarksville, Indiana American people of English descent American amputees History of Louisville, Kentucky Illinois in the American Revolution Indiana in the American Revolution Kentucky militiamen in the American Revolution Militia generals in the American Revolution American mercenaries American filibusters (military) Military personnel from Louisville, Kentucky People in Dunmore's War American slave owners American explorers Kentucky pioneers People of Virginia in the American Revolution People of Kentucky in the American Revolution People from Clark County, Indiana American people of Scottish descent Virginia colonial people 18th-century Anglicans American Anglicans American surveyors American naturalists

Anthony Wayne

Anthony Wayne (January 1, 1745 – December 15, 1796) was an American soldier, officer, statesman, and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. He adopted a military career at the outset of the American Revolutionary War, where his mi ...

to Fort Massac to stop the expedition. The French government recalled Genêt and revoked the commissions he granted to the Americans for the war against Spain. Clark's planned campaign gradually collapsed, and he was unable to convince the French to reimburse him for his expenses. Clark's reputation, already damaged by earlier accusations at the end of the Revolutionary War, was further maligned as a result of his involvement in these foreign intrigues.

Mounting debts

In his later years Clark's mounting debts made it impossible for him to retain ownership of his land, since it became subject to seizure due to his debts. Clark deeded much of his land to friends or transferred ownership to family members so his creditors could not seize it. Lenders and their assignees eventually deprived the veteran of nearly all of the property that remained in his name. Clark, who was at one time the largest landholder in the Northwest Territory, was left with only a small plot of land in Clarksville. In 1803 Clark built a cabin overlooking the Falls of the Ohio, where he lived until his health failed in 1809. He also purchased a smallgristmill

A gristmill (also: grist mill, corn mill, flour mill, feed mill or feedmill) grinds cereal grain into flour and middlings. The term can refer to either the grinding mechanism or the building that holds it. Grist is grain that has been separated ...

, which Clark operated with two slaves he owned.

Clark's knowledge of the region helped him to become an expert on the West's natural history. Over the years he welcomed travelers, including those interested in natural history, to his home overlooking the Ohio River. Clark supplied details on the area's plant and animal life to John Pope and John James Audubon, and hosted his brother, William, and Meriweather Lewis, prior to their expedition to the Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (sometimes Cascadia, or simply abbreviated as PNW) is a geographic region in western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Though ...

. Clark also provided information on the Ohio Valley's native tribes to Allan Bowie Magruder

Allan Bowie Magruder (1775April 16, 1822) was an American poet, historian, lawyer, and politician, who served as a United States Senator from Louisiana from September 3, 1812 to March 3, 1813.

Early life

Allan Bowie Magruder was born in either ...

and archaeological evidence related to the Mound Builders to John P. Campbell.

In later life Clark continued to struggle with alcohol abuse, a problem which had plagued him on-and-off for many years. He also remained bitter about his treatment and neglect by Virginia, and blamed it for his financial misfortune.

When the Indiana Territory

The Indiana Territory, officially the Territory of Indiana, was created by a congressional act that President John Adams signed into law on May 7, 1800, to form an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 4, ...

chartered the Indiana Canal Company in 1805 to build a canal around the Falls of the Ohio, near Clarksville, Clark was named to the board of directors. He became part of the surveying team that assisted in laying out the route of the canal. The company collapsed the next year before construction could begin, when two of the fellow board members, including Vice President

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is o ...

Aaron Burr, were arrested for treason. A large part of the company's $1.2 million (equivalent to $ million in ) in investments was unaccounted for; its location was never determined.

Return to Kentucky

Alcoholism and poor health afflicted Clark during his final years. In 1809 he suffered a severe stroke. When he fell into a burning fireplace, he suffered a burn on his right leg that was so severe it had to be amputated. The injury made it impossible for Clark to continue to operate his mill and live independently. As a result, he moved to Locust Grove, a farm eight miles (13 km) from the growing town of Louisville, and became a member of the household of his sister, Lucy, and brother-in-law, Major William Croghan, a planter. In 1812 the Virginia General Assembly granted Clark a pension of four hundred dollars per year and finally recognized his services in the Revolutionary War by presenting him with a ceremonial sword.Death and legacy

After another stroke, Clark died at Locust Grove on February 13, 1818; he was buried at Locust Grove Cemetery two days later. Clark's remains were exhumed along with those of his other family members on October 29, 1869, and buried at Cave Hill Cemetery in Louisville. In his funeral oration, JudgeJohn Rowan John Rowan may refer to:

* John Rowan (American football) (1896–1967)

* John Rowan (footballer) (1890-1963), Scottish footballer

* John Rowan (high sheriff) (1778–1855), Irish high sheriff and militia officer

*John Rowan (Kentucky politicia ...

succinctly summed up Clark's stature and importance during the critical years on the trans-Appalachian frontier: "The mighty oak of the forest has fallen, and now the scrub oaks sprout all around." Clark's career was closely tied to events in the Ohio-Mississippi Valley at a pivotal time when the region was inhabited by numerous Native American tribes and claimed by the British, Spanish, and French, as well as the fledgling U.S. government. As a member of the Virginia militia, and with Virginia's support, Clark's campaign into the Illinois country helped strengthen Virginia's claim on lands in the region as it came under the control of the Americans. Clark's military service in the interior of North America also helped him became an "important source of leadership and information (although not necessarily accurate) on the West."

Clark is best known as a war hero of the Revolutionary War in the West, especially as the leader of the secret expeditionary forces that captured Kaskaskia, Cahokia, and Vincennes in 1778–79. Some historians have suggested that the campaign supported American claims to the Northwest Territory during negotiations that resulted in the Treaty of Paris (1783)

The Treaty of Paris, signed in Paris by representatives of King George III of Great Britain and representatives of the United States of America on September 3, 1783, officially ended the American Revolutionary War and overall state of conflict ...

.

Clark's Grant, the large tract of land on the north side of the Ohio River that he received as compensation for his military service, included a large portion of Clark County, Indiana, and portions of Floyd and Scott

Scott may refer to:

Places Canada

* Scott, Quebec, municipality in the Nouvelle-Beauce regional municipality in Quebec

* Scott, Saskatchewan, a town in the Rural Municipality of Tramping Lake No. 380

* Rural Municipality of Scott No. 98, Saska ...

Counties, as well as the present-day site of Clarksville, Indiana, the first American town laid out in the Northwest Territory (in 1784). Clark served as the first chairman of the Clarksville, Indiana, board of trustees. Clark was unable to retain title to his landholdings. At the end of his life, he was poor, in ill health, and frequently intoxicated.

Several years after Clark's death the state of Virginia granted his estate $30,000 () as a partial payment on the debts it owed him. The government of Virginia continued to repay Clark for decades; the last payment to his estate was made in 1913.

Clark never married and he kept no account of any romantic relationships, although his family held that he had once been in love with Teresa de Leyba, sister of Don Fernando de Leyba, the lieutenant governor of Spanish Louisiana. Writings from his niece and cousin in the Draper Manuscripts in the archives of the Wisconsin Historical Society

The Wisconsin Historical Society (officially the State Historical Society of Wisconsin) is simultaneously a state agency and a private membership organization whose purpose is to maintain, promote and spread knowledge relating to the history of ...

attest to their belief in Clark's lifelong disappointment over the failed romance.

Honors and tributes

* On May 23, 1928, PresidentCalvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States from 1923 to 1929. Born in Vermont, Coolidge was a Republican lawyer from New England who climbed up the ladder of Ma ...

ordered a memorial to Clark to be erected at Vincennes, Indiana. Completed in 1933, the George Rogers Clark Memorial was dedicated on June 14, 1936, by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The Roman-style temple was erected on what was believed to have been the site of Fort Sackville. The site, now called the George Rogers Clark National Historical Park, became a part of the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an List of federal agencies in the United States, agency of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government within the United States Department of the Interior, U.S. Department of ...

in 1966. Hermon Atkins MacNeil created the monument's bronze statue of Clark. The monument's walls include seven murals depicting Clark's famous expedition.

* On February 25, 1929, to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the surrender of Fort Sackville, the U.S. Postal Service issued a two-cent postage stamp

A postage stamp is a small piece of paper issued by a post office, postal administration, or other authorized vendors to customers who pay postage (the cost involved in moving, insuring, or registering mail), who then affix the stamp to the ...

depicting the event.

* In 1975 the Indiana General Assembly

The Indiana General Assembly is the state legislature, or legislative branch, of the state of Indiana. It is a bicameral legislature that consists of a lower house, the Indiana House of Representatives, and an upper house, the Indiana Senate. ...

designated February 25 as George Rogers Clark Day in Indiana.

* In 1979 Indiana's automobile license plates commemorated the 200th anniversary of Clark's capture of Fort Sackville.

* A bronze statue of Clark is one of several erected on Monument Circle, surrounding the Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument, in downtown Indianapolis, Indiana

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the List of U.S. state and territorial capitals, state capital and List of U.S. states' largest cities by population, most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the county seat, seat of ...

. Sculptor John H. Mahoney received the commission to create the statue, which was completed in 1895.

* The Daughters of the American Revolution

The Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) is a lineage-based membership service organization for women who are directly descended from a person involved in the United States' efforts towards independence.

A non-profit group, they promot ...

placed a statue by sculptor Leon Hermant at Metropolis, the site of Fort Massac, in Massac County, Illinois, in the early 1900s.

* Sculptor Felix de Weldon created the Clark statue at Riverfront Plaza/Belvedere

Riverfront Plaza/Belvedere is a public area on the Ohio River in Downtown Louisville, Kentucky. Although proposed as early as 1930, the project did not get off the ground until $13.5 million in funding was secured in 1969 to revitalize the downtow ...

, next to the wharf on the Ohio River, in Louisville, Kentucky.Kleber, John E., ed. (2001). "Riverfront Plaza/Belvedere". Encyclopedia of Louisville.

* Charles Keck created the memorial statue of Clark at the site of the Battle of Piqua

The Battle of Piqua, also known as the Battle of Peckowee, Battle of Pekowi, Battle of Peckuwe and the Battle of Pickaway, was a military engagement fought on August 8, 1780 at the Indian village of Piqua along the Mad River in western Ohio Cou ...

, near Springfield, Ohio

Springfield is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Clark County. The municipality is located in southwestern Ohio and is situated on the Mad River, Buck Creek, and Beaver Creek, approximately west of Columbus and northe ...

.

* Robert Aitken's bronze sculpture of Clark was erected on Monument Square, on the grounds of the University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. Founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson, the university is ranked among the top academic institutions in the United States, with College admission ...

at Charlottesville, Virginia

Charlottesville, colloquially known as C'ville, is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia. It is the county seat of Albemarle County, which surrounds the city, though the two are separate legal entities. It is named after Queen ...

, in 1921. It was removed by the University of Virginia in July 2021, after it was deemed offensive in its portrayal of Native Americans and its removal was recommended by a racial equity task force.

* A Clark statue was erected in Riverview Park, on the eastern bank of the Mississippi River at Quincy, Illinois

Quincy ( ), known as Illinois's "Gem City", is a city in and the county seat of Adams County, Illinois, United States, located on the Mississippi River. The 2020 census counted a population of 39,463 in the city itself, down from 40,633 in 2010. ...

, in 1909.

* In April 1929, the Paul Revere Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution

The Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) is a lineage-based membership service organization for women who are directly descended from a person involved in the United States' efforts towards independence.

A non-profit group, they promot ...

of Muncie, Indiana, erected a monument to Clark on Washington Avenue in Fredericksburg, Virginia

Fredericksburg is an independent city located in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 27,982. The Bureau of Economic Analysis of the United States Department of Commerce combines the city of Fredericksburg wi ...

. Clark spent his childhood in southwestern Caroline County, about 40 miles from Fredericksburg.

* Clark is the namesake of a number of counties in the United States: Clark County, Illinois

Clark County is a county located in the southeastern part of U.S. state of Illinois, along the Indiana state line. As of the 2010 census, the population was 16,335. Its county seat is Marshall. The county was named for George Rogers Clark, a ...

; Clark County, Indiana

Clark County is a county in the U.S. state of Indiana, located directly across the Ohio River from Louisville, Kentucky. At the 2020 census, the population was 121,093. The county seat is Jeffersonville. Clark County is part of the Louisvil ...

; Clark County, Kentucky; Clark County, Ohio; Clarke County, Virginia; and Clark County, Wisconsin.

* Several communities in the U.S. have been named in his honor: Clarksville, Indiana; Clarksville, Tennessee;Clarksville, Tennessee: Gateway to the New South, Fort Campbell website, accessed October 11, 2008 and Clarksburg, West Virginia.

* Schools named in Clark's honor include: ** George Rogers Clark Elementary School of

Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

, Illinois.

** George Rogers Clark Elementary School, Clarksville, Indiana (closed 2010)

** George Rogers Clark College, Indianapolis, Indiana (closed 1992)

** George Rogers Clark Middle School, Vincennes, Indiana

** George Rogers Clark Junior High School, Springfield, Ohio (now closed)

** George Rogers Clark Middle/High School, Whiting, Lake County, Indiana (school closing following the 2020–21 school year)

** George Rogers Clark Elementary School, Paducah, Kentucky

** George Rogers Clark High School, Winchester, Clark County, Kentucky

** George Rogers Clark Elementary School, Charlottesville, Virginia

Charlottesville, colloquially known as C'ville, is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia. It is the county seat of Albemarle County, which surrounds the city, though the two are separate legal entities. It is named after Queen ...

* Other sites and structures:

** The George Rogers Clark Memorial Bridge (Second Street Bridge), built in 1929, carries U.S. Highway 31

U.S. Route 31 or U.S. Highway 31 (US 31) is a major north–south U.S. highway connecting southern Alabama to northern Michigan. Its southern terminus is at an intersection with US 90/ US 98 in Spanish Fort, Alabama. Its ...

over the Ohio River at Louisville, Kentucky.

** In 1979 the Indiana American Revolution Bicentennial Commission and the Indiana Highway Commission erected an estimated 600 signs to establish the George Rogers Clark Trail, marking the routes used by Clark and his men in Indiana during the Revolutionary War.

** Clark Street in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

, is named in his honor.

* The Liberty Ship

Liberty ships were a ship class, class of cargo ship built in the United States during World War II under the Emergency Shipbuilding Program. Though British in concept, the design was adopted by the United States for its simple, low-cost constr ...

SS ''George Rogers Clark''. Launched 9 November 1942; Commissioned 2 January 1943; Sold private 1947, scrapped 1963.

See also

*History of Louisville, Kentucky

The geology of the Ohio River, with but a single series of rapids halfway in its length from the confluence of the Monongahela and Allegheny rivers to its union with the Mississippi, made it inevitable that a town would grow on the site. Louisvi ...

* List of people from the Louisville metropolitan area

* George Rogers Clark Flag

* Old Clarksville Site

* George Rogers Clark (bust)

''George Rogers Clark'' is a plaster bust made by American artist David McLary. Dated 1985, the sculpture depicts American Revolutionary War hero and frontiersman George Rogers Clark. The bust is located in an alcove on the third floor of the ...

Notes

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * * * * * *External links

Patrick Henry's Secret Orders to Clark

dated January 2, 1778 – Indiana Historical Society

*

Indiana Historical Bureau

Indiana Historical Bureau

Clark Family Papers

– Missouri History Museum Archives *

"The Clarks: The First Family of the Frontier,"

8thVirginia.com. *

Guide to the Reuben T. Durrett Collection of George Rogers Clark Papers 1776-1896

at th

University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center

{{DEFAULTSORT:Clark, George Rogers 1752 births 1818 deaths American people of the Northwest Indian War Burials at Cave Hill Cemetery Clark County, Ohio Clarksburg, West Virginia Clarksville, Indiana American people of English descent American amputees History of Louisville, Kentucky Illinois in the American Revolution Indiana in the American Revolution Kentucky militiamen in the American Revolution Militia generals in the American Revolution American mercenaries American filibusters (military) Military personnel from Louisville, Kentucky People in Dunmore's War American slave owners American explorers Kentucky pioneers People of Virginia in the American Revolution People of Kentucky in the American Revolution People from Clark County, Indiana American people of Scottish descent Virginia colonial people 18th-century Anglicans American Anglicans American surveyors American naturalists