George Ledyard Stebbins on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

George Ledyard Stebbins Jr. (January 6, 1906 – January 19, 2000) was an American

Stebbins started graduate studies at Harvard in 1928, initially working on flowering

Stebbins started graduate studies at Harvard in 1928, initially working on flowering

In 1935, Stebbins was offered a genetics research position at the

In 1935, Stebbins was offered a genetics research position at the  Stebbins's review, "The significance of polyploidy in plant evolution", published in '' American Naturalist'' in 1940, demonstrated how work done on artificial polyploids and natural polyploid complexes had shown that polyploidy was important in developing large, complex, and widespread genera. However, by looking at the history of polyploidy in plant

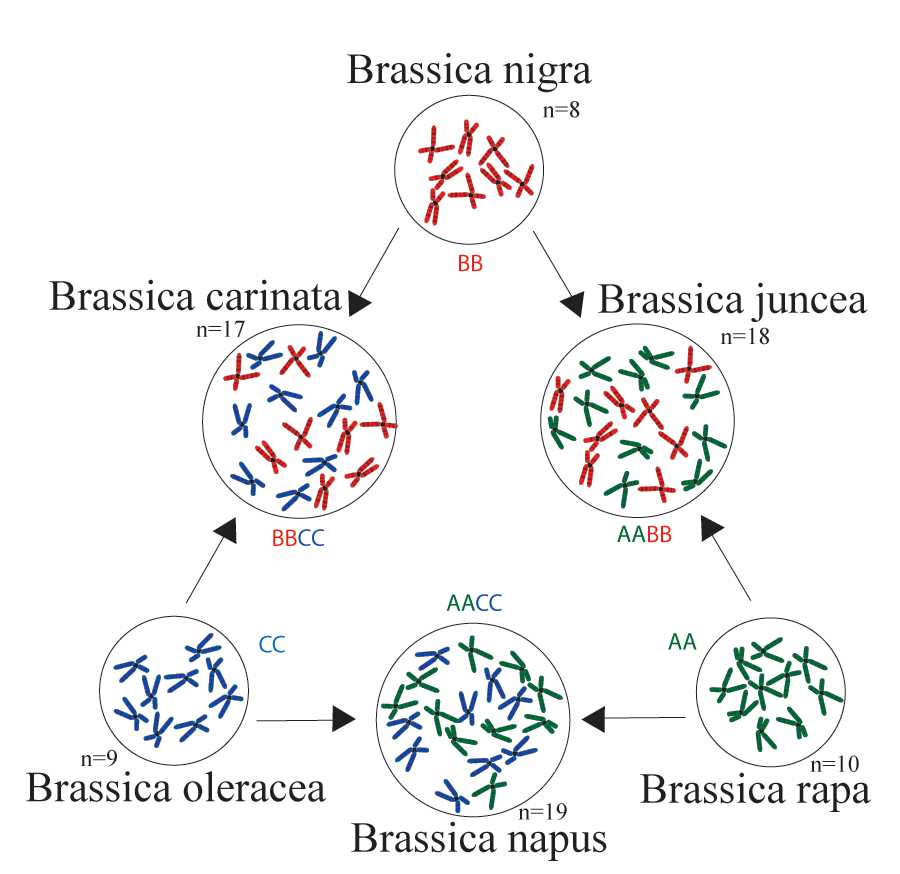

Stebbins's review, "The significance of polyploidy in plant evolution", published in '' American Naturalist'' in 1940, demonstrated how work done on artificial polyploids and natural polyploid complexes had shown that polyploidy was important in developing large, complex, and widespread genera. However, by looking at the history of polyploidy in plant

January 20, 2000, UC Davis News Service His ashes were scattered at

George Ledyard Stebbins, January 6, 1906–January 19, 2000

''Biographical Memoirs'', vol. 85, Washington DC: National Academies Press, pp. 1–24. * Stebbins, G. L. (V. C. Hollowell, V. B. Smocovitis and E. P. Duggan, editors). 2007. The Ladyslipper and I. Monographs in Systematic Botany from the Missouri Botanical Garden. Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis utobiography

Full list of Stebbins' publications

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Stebbins, G. Ledyard Botanists with author abbreviations Evolutionary biologists 1906 births 2000 deaths Botanists active in California Botanists active in North America Modern synthesis (20th century) National Medal of Science laureates Foreign Members of the Royal Society University of California, Berkeley faculty University of California, Davis faculty Harvard University alumni Botanical Society of America People from St. Lawrence County, New York Deaths from cancer in California People from Carpinteria, California Scientists from California 20th-century American biologists 20th-century American botanists Scientists from New York (state) Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Members of the American Philosophical Society

botanist

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek wo ...

and geneticist who is widely regarded as one of the leading evolutionary biologists

Evolutionary biology is the subfield of biology that studies the evolution, evolutionary processes (natural selection, common descent, speciation) that produced the Biodiversity, diversity of life on Earth. It is also defined as the study of ...

of the 20th century. Stebbins received his Ph.D. in botany from Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

in 1931. He went on to the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant u ...

, where his work with E. B. Babcock

Ernest Brown Babcock (July 10, 1877 – December 8, 1954) was an American plant geneticist who pioneered the under

standing of plant evolution in terms of genetics. He is particularly known for seeking to understand by field investigations and e ...

on the genetic evolution of plant species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

, and his association with a group of evolutionary biologists known as the Bay Area Biosystematists, led him to develop a comprehensive synthesis of plant evolution incorporating genetics.

His most important publication was '' Variation and Evolution in Plants'', which combined genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar wor ...

and Darwin's theory of natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Charle ...

to describe plant speciation

Speciation is the evolutionary process by which populations evolve to become distinct species. The biologist Orator F. Cook coined the term in 1906 for cladogenesis, the splitting of lineages, as opposed to anagenesis, phyletic evolution within ...

. It is regarded as one of the main publications which formed the core of the modern synthesis

Modern synthesis or modern evolutionary synthesis refers to several perspectives on evolutionary biology, namely:

* Modern synthesis (20th century), the term coined by Julian Huxley in 1942 to denote the synthesis between Mendelian genetics and s ...

and still provides the conceptual framework for research in plant evolutionary biology; according to Ernst Mayr

Ernst Walter Mayr (; 5 July 1904 – 3 February 2005) was one of the 20th century's leading evolutionary biologists. He was also a renowned Taxonomy (biology), taxonomist, tropical explorer, ornithologist, Philosophy of biology, philosopher o ...

, "Few later works dealing with the evolutionary systematics of plants have not been very deeply affected by Stebbins' work." He also researched and wrote widely on the role of hybridization

Hybridization (or hybridisation) may refer to:

*Hybridization (biology), the process of combining different varieties of organisms to create a hybrid

*Orbital hybridization, in chemistry, the mixing of atomic orbitals into new hybrid orbitals

*Nu ...

and polyploidy in speciation and plant evolution; his work in this area has had a lasting influence on research in the field.

From 1960, Stebbins was instrumental in the establishment of the Department of Genetics at the University of California, Davis

The University of California, Davis (UC Davis, UCD, or Davis) is a public land-grant research university near Davis, California. Named a Public Ivy, it is the northernmost of the ten campuses of the University of California system. The institut ...

, and was active in numerous organizations involved in the promotion of evolution, and of science in general. He was elected to the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nati ...

and the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

, was awarded the National Medal of Science, and was involved in the development of evolution-based science programs for California high schools, as well as the conservation of rare plants in that state.

Early life and education

Stebbins was born in Lawrence, New York, the youngest of three children. His parents were George Ledyard Stebbins, a wealthy real estate financier who developedSeal Harbor, Maine

Mount Desert is a town on Mount Desert Island in Hancock County, Maine, United States. The population was 2,146 at the 2020 census. Incorporated in 1789, the town currently encompasses the villages of Otter Creek, Seal Harbor, Northeast Harb ...

and helped to establish Acadia National Park, and Edith Alden Candler Stebbins; both parents were native New Yorkers and Episcopalian

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the l ...

s. Stebbins was known throughout his life as Ledyard, to distinguish himself from his father. The family encouraged their sons' interest in natural history during their periodic journeys to Seal Harbor. In 1914, Edith contracted tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

and the Stebbins moved to Santa Barbara, California

Santa Barbara ( es, Santa Bárbara, meaning "Saint Barbara") is a coastal city in Santa Barbara County, California, of which it is also the county seat. Situated on a south-facing section of coastline, the longest such section on the West Coas ...

to improve her health. In California, Stebbins was enrolled at the Cate School in Carpinteria where he became influenced by Ralph Hoffmann

Ralph Hoffmann (November 30, 1870 – July 21, 1932) was an American natural history teacher, ornithologist, and botanist. He was the author of the first true bird field guide.

Early life

Ralph Hoffmann was born on November 30, 1870, at Stockbr ...

, an American natural history instructor and amateur ornithologist

Ornithology is a branch of zoology that concerns the "methodological study and consequent knowledge of birds with all that relates to them." Several aspects of ornithology differ from related disciplines, due partly to the high visibility and th ...

and botanist

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek wo ...

. After graduating from high school, he embarked on a major in political studies at Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

. By the third year of his undergraduate study, he had decided to major in botany

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek w ...

.

Stebbins started graduate studies at Harvard in 1928, initially working on flowering

Stebbins started graduate studies at Harvard in 1928, initially working on flowering plant taxonomy

Plant taxonomy is the science that finds, identifies, describes, classifies, and names plants. It is one of the main branches of taxonomy (the science that finds, describes, classifies, and names living things).

Plant taxonomy is closely allied ...

and biogeography

Biogeography is the study of the distribution of species and ecosystems in geographic space and through geological time. Organisms and biological communities often vary in a regular fashion along geographic gradients of latitude, elevation, ...

—particularly that of the flora of New England—with Merritt Lyndon Fernald. He completed his MA in 1929 and continued to work toward his Ph.D.

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, Ph.D., or DPhil; Latin: or ') is the most common degree at the highest academic level awarded following a course of study. PhDs are awarded for programs across the whole breadth of academic fields. Because it is a ...

He became interested in using chromosome

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins are ...

s for taxonomic studies, a method that Fernald did not support. Stebbins chose to concentrate his doctoral work on the cytology of plant reproductive processes in the genus ''Antennaria

''Antennaria'' is a genus of dioecious perennial herbs in the family Asteraceae, native to temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere, with a few species (''A. chilensis'', ''A. linearifolia'', ''A. sleumeri'') in temperate southern South A ...

'', with cytologist E. C. Jeffrey

Edward Charles Jeffrey (May 21, 1866 – April 19, 1952) was a Canadian- American botanist who worked on vascular plant anatomy and phylogeny.

From 1892 to 1902 Jeffrey was a lecturer at the University of Toronto. While on leave of absence, he ...

as his supervisor and Fernald on his supervisory panel. During his Ph.D. candidature, Stebbins sought advice and supervision from geneticist Karl Sax

Karl Sax (November 2, 1892 – October 8, 1973) was an American botanist and geneticist, noted for his research in cytogenetics and the effect of radiation on chromosomes.

Early life and education

Sax was born in Spokane, Washington in 1892. His ...

. Sax identified several errors in Stebbins's work and disapproved of his interpretation of results that, while in accordance with Jeffrey's views, were inconsistent with the work of contemporary geneticists. Jeffrey and Sax argued over Stebbins's dissertation, and the thesis was revised numerous times to accommodate their differing views.

Stebbins's Ph.D. was granted by Harvard in 1931. In March that year, he married Margaret Chamberlin, with whom he had three children. In 1932, he took a teaching position in biology at Colgate University

Colgate University is a private liberal arts college in Hamilton, New York. The college was founded in 1819 as the Baptist Education Society of the State of New York and operated under that name until 1823, when it was renamed Hamilton Theologi ...

. While at Colgate, he continued his work in cytogenetics; in particular, he continued to study the genetics of ''Antennaria'' and began to study the behaviour of chromosomes in hybrid peonies bred by biologist Percy Saunders. Saunders and Stebbins attended the 1932 International Congress of Genetics in Ithaca, New York. Here, Stebbins's interest was captured by talks given by Thomas Hunt Morgan and Barbara McClintock

Barbara McClintock (June 16, 1902 – September 2, 1992) was an American scientist and cytogeneticist who was awarded the 1983 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. McClintock received her PhD in botany from Cornell University in 1927. There s ...

, who spoke about chromosomal crossover

Chromosomal crossover, or crossing over, is the exchange of genetic material during sexual reproduction between two homologous chromosomes' non-sister chromatids that results in recombinant chromosomes. It is one of the final phases of geneti ...

. Stebbins reproduced McClintock's crossover experiments in the peony, and published several papers on the cytogenetics of ''Paeonia'', which established his reputation as a geneticist.

UC Berkeley

In 1935, Stebbins was offered a genetics research position at the

In 1935, Stebbins was offered a genetics research position at the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant u ...

working with geneticist E. B. Babcock

Ernest Brown Babcock (July 10, 1877 – December 8, 1954) was an American plant geneticist who pioneered the under

standing of plant evolution in terms of genetics. He is particularly known for seeking to understand by field investigations and e ...

. Babcock needed assistance with a large Rockefeller Rockefeller is a German surname, originally given to people from the village of Rockenfeld near Neuwied in the Rhineland and commonly referring to subjects associated with the Rockefeller family. It may refer to:

People with the name Rockefeller fa ...

-funded project characterizing the genetics and evolutionary processes of plants from the genus '' Crepis'' and was interested in developing ''Crepis'' into a model plant

A model organism (often shortened to model) is a non-human species that is extensively studied to understand particular biological phenomena, with the expectation that discoveries made in the model organism will provide insight into the working ...

, to enable genetic investigations similar to those possible in the model insect ''Drosophila melanogaster

''Drosophila melanogaster'' is a species of fly (the taxonomic order Diptera) in the family Drosophilidae. The species is often referred to as the fruit fly or lesser fruit fly, or less commonly the "vinegar fly" or "pomace fly". Starting with Ch ...

''. Like the genera that Stebbins had previously studied, ''Crepis'' commonly hybridized, displayed polyploidy (chromosome doubling), and could make seed without fertilization (a process known as apomixis

In botany, apomixis is asexual reproduction without fertilization. Its etymology is Greek for "away from" + "mixing". This definition notably does not mention meiosis. Thus "normal asexual reproduction" of plants, such as propagation from cuttin ...

). The collaboration between Babcock and Stebbins produced numerous papers and two monograph

A monograph is a specialist work of writing (in contrast to reference works) or exhibition on a single subject or an aspect of a subject, often by a single author or artist, and usually on a scholarly subject.

In library cataloging, ''monograph ...

s. The first monograph, published in 1937, resulted in splitting off the Asiatic ''Crepis'' species into the genus ''Youngia

''Youngia'' is a genus of Asian plants in the tribe Cichorieae within the family Asteraceae. There are several weedy species in the genus as well as the endangered ''Youngia nilgiriensis'' from Sispara in southern India, and '' Youngia japonica' ...

''. The second, published in 1938, was titled ''The American Species of Crepis: their interrelationships and distribution as affected by polyploidy and apomixis''.

In ''The American Species of Crepis'', Babcock and Stebbins described the concept of the polyploid complex A polyploid complex, also called a diploid-polyploid complex, is a group of interrelated and interbreeding species that also have differing levels of ploidy that can allow interbreeding.

A polyploid complex was described by E. B. Babcock and G. Led ...

, and its role in plant evolution. Some genera, such as ''Crepis'', have a complex of reproductive forms that center on sexually diploid populations that have also given rise to polyploid ones. Babcock and Stebbins also observed that allopolyploid

Polyploidy is a condition in which the cells of an organism have more than one pair of ( homologous) chromosomes. Most species whose cells have nuclei (eukaryotes) are diploid, meaning they have two sets of chromosomes, where each set contains ...

types formed from the hybridization of two different species always have a wider distribution than diploid or autotetraploid species, and proposed that polyploids formed through hybridization have a greater potential to exploit varied environments, because they inherit all traits from both parents. They also showed that hybridization in the polyploid complex could provide a mechanism for genetic exchange between diploid species that were otherwise unable to breed. Their observations offered insight into species formation and knowledge of how all these complex processes could provide information on the history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the History of writing#Inventions of writing, invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbr ...

of a genus. This monograph was described by Swedish botanist Åke Gustafsson as the most important work on the formation of species during that period.

families

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Ideall ...

, he argued that polyploidy was only common in herbaceous perennials and infrequent in woody plants and annuals. As such, polyploids played a conservative role in evolution since problems with fertility prevented the acquisition and replication of new genetic material that might lead to a new line of evolution. This work continued with the 1947 paper "Types of polyploids: their classification and significance", which detailed a system for the classification of polyploids and described Stebbins' ideas about the role of paleopolyploidy

Paleopolyploidy is the result of genome duplications which occurred at least several million years ago (MYA). Such an event could either double the genome of a single species (autopolyploidy) or combine those of two species (allopolyploidy). Bec ...

in angiosperm evolution, where he argued that chromosome number may be a useful tool for the construction of phylogenies. These reviews were highly influential and provided a basis for others to study the role of polyploidy in evolution.

In 1939, with Babcock's support, Stebbins was made a full professor in the Department of Genetics at UC Berkeley, after the Department of Botany failed to promote him. Stebbins was required to teach a course on evolution, and during his preparation he became excited by contemporary research combining genetics and evolution. He became associated with a group known as the Bay Area Biosystematists, which included botanist Jens Clausen

Jens Christen (Christian) Clausen (March 11, 1891 – November 22, 1969) was a Danish-American botanist, geneticist, and ecologist. He is considered a pioneer in the field of ecological and evolutionary genetics of plants.

Biography

Clausen wa ...

, taxonomist David D. Keck

David Daniels Keck (October 24, 1903 – March 10, 1995) was an American botanist who was notable for his work on angiosperm taxonomy and genetics.

Keck was born in Omaha, Nebraska. He completed undergraduate studies at Pomona College in 1925 ...

, physiologist William Hiesey

William McKinley Hiesey (August 21, 1903 – August 7, 1998) was an American botanist who specialized in ecological physiology. He was notable for his collaboration with Jens Clausen and David D. Keck at Stanford University in the 1930s. In 194 ...

and the evolutionary geneticist Theodosius Dobzhansky

Theodosius Grigorievich Dobzhansky (russian: Феодо́сий Григо́рьевич Добржа́нский; uk, Теодо́сій Григо́рович Добржа́нський; January 25, 1900 – December 18, 1975) was a prominent ...

. During this time he also became friends with the botanist Herbert Baker. With the encouragement of this group of scientists, Stebbins directed his research towards evolution. He became involved with the Society for the Study of Evolution in 1946, and was one of the few botanists involved with the new organization.

His research on plant evolution also progressed during this period; he worked on the genetics of forage grasses, looking at polyploidy and the evolution of the Poaceae

Poaceae () or Gramineae () is a large and nearly ubiquitous family of monocotyledonous flowering plants commonly known as grasses. It includes the cereal grasses, bamboos and the grasses of natural grassland and species cultivated in lawns an ...

and publishing numerous papers on the subject though the 1940s. He produced an artificial autotetraploid grass from the diploid species ''Ehrharta erecta

''Ehrharta erecta'' is a species of grass commonly known as panic veldtgrass. The species is native to Southern Africa and Yemen. It is a documented invasive species in the United States, New Zealand, Australia, southern Europe, and China.

The ...

'' through treatment with the chromosome doubling agent colchicine. He was able to establish the plant in the field, and after 39 years of field trials was able to show that the autopolyploid was not as successful as its diploid parent in an unchanging environment.

''Variation and Evolution in Plants''

Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

's Jesup Lectures were the starting point for many of the most important works of the modern evolutionary synthesis

Modern synthesis or modern evolutionary synthesis refers to several perspectives on evolutionary biology, namely:

* Modern synthesis (20th century), the term coined by Julian Huxley in 1942 to denote the synthesis between Mendelian genetics and s ...

. The presenters introduced the connection between two important discoveries—the units of evolution (gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a ba ...

s) with selection as the primary mechanism of evolution. In 1941, Edgar Anderson (whose work on hybridization in the genus '' Iris'' had interested Stebbins since they met in 1930) and Ernst Mayr

Ernst Walter Mayr (; 5 July 1904 – 3 February 2005) was one of the 20th century's leading evolutionary biologists. He was also a renowned Taxonomy (biology), taxonomist, tropical explorer, ornithologist, Philosophy of biology, philosopher o ...

co-presented the lecture series and Mayr later published his lectures as ''Systematics and the Origin of Species ''Systematics and the Origin of Species from the Viewpoint of a Zoologist'' is a book written by zoologist and evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr, first published in 1942 by Columbia University Press. The book became one of the canonical publications ...

''. In 1946, Stebbins was invited on Dobzhansky's recommendation to present the prestigious lectures. Stebbins' lectures drew together the otherwise disparate fields of genetics, ecology, systematics, cytology, and paleontology. In 1950, these lectures were published as '' Variation and Evolution in Plants'', which proved to be one of the most important books in 20th-century botany. The book brought botanical science into the new synthesis of evolutionary theory, and became part of the canon of biological works written between 1936 and 1950 that formed the modern synthesis of evolution.

''Variation and Evolution in Plants'' was the first book to provide a wide-ranging explanation of how evolutionary mechanisms operated in plants at the genetic level. It brought concepts related to plant evolution into line with animal evolution as it emerged from Dobzhansky's 1937 '' Genetics and the Origin of Species'' and provided the conceptual framework to organize a disparate set of disciplines into a new field: plant evolutionary biology. In the book Stebbins argued that evolution needed to be studied as a dynamic problem and that evolution must be considered on three levels: first, that of individual variation within an interbreeding population; second, that of the distribution and frequency of this variation; and third, that of the separation and divergence of populations as the result of the building up of isolating mechanisms leading to the formation of species. He used the work of biosystematists Clausen, Keck, Hiesey, and Turesson to show that it was possible to distinguish between genotypic

The genotype of an organism is its complete set of genetic material. Genotype can also be used to refer to the alleles or variants an individual carries in a particular gene or genetic location. The number of alleles an individual can have in a ...

and phenotypic

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology or physical form and structure, its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological proper ...

variation—that is, genetically identical plants could have different phenotypes in different environments. One of the book's most original chapters used the cytogenetics work of C. D. Darlington

Cyril Dean Darlington (19 December 1903 – 26 March 1981) was an English biologist, cytologist, geneticist and eugenicist, who discovered the mechanics of chromosomal crossover, its role in inheritance, and therefore its importance to evoluti ...

to show that genetic systems like hybridization and polyploidy were also subject to selection.

The book offered few original hypotheses, but Stebbins hoped that by summarising the available research on plant evolution the book would "help to open the way towards a deeper understanding of evolutionary problems and more fruitful research in the direction of their solution." The book effectively ended any serious belief in alternative mechanisms of evolution in plants, such as Lamarckian evolution or soft inheritance

Lamarckism, also known as Lamarckian inheritance or neo-Lamarckism, is the notion that an organism can pass on to its offspring physical characteristics that the parent organism acquired through use or disuse during its lifetime. It is also calle ...

, which were still upheld by some botanists. Following that publication, Stebbins was regarded as an expert on modern evolutionary theory and is widely credited with the founding of the science of plant evolutionary biology. ''Variation and Evolution in Plants'' continues to be widely cited in contemporary scientific botanical literature more than 50 years after its publication.

Stebbins regarded his contribution to the modern synthesis as the application of genetic principles already established by other workers to botany. "I didn't add any new elements o the modern synthetic theoryto speak of. I just modified things so that people could understand how things were in the plant world."

UC Davis and later life

Stebbins took an appointment at theUniversity of California, Davis

The University of California, Davis (UC Davis, UCD, or Davis) is a public land-grant research university near Davis, California. Named a Public Ivy, it is the northernmost of the ten campuses of the University of California system. The institut ...

in 1950, where he was a key figure in the establishment of the University's Department of Genetics; he was the department's first chairman and held the position from 1958 to 1963. At Davis, the focus of his research changed to incorporate newer areas, such as developmental morphology and genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar wor ...

in crop plants, including barley

Barley (''Hordeum vulgare''), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains, particularly in Eurasia as early as 10,000 years ago. Globally 70% of barley pr ...

. He continued to publish widely and extensively on plant evolution, writing over 200 papers and several books after 1950.

Stebbins and Edgar Anderson wrote a paper in 1954 on the importance of hybridization in adapting to new environments. They proposed novel adaptations would facilitate the invasion of habitats not utilized previously by either parent and that novel adaptations may facilitate the formation of stabilized hybrid species. Following this paper, Stebbins developed the first model of adaptive radiation

In evolutionary biology, adaptive radiation is a process in which organisms diversify rapidly from an ancestral species into a multitude of new forms, particularly when a change in the environment makes new resources available, alters biotic int ...

. He proposed that a high degree of genetic variability was necessary for major evolutionary advances, that because of slow mutation rates, genetic recombination

Genetic recombination (also known as genetic reshuffling) is the exchange of genetic material between different organisms which leads to production of offspring with combinations of traits that differ from those found in either parent. In eukaryo ...

was the most likely source of this variation, and that variation could be maximised though hybridization. As of 2006, research is ongoing regarding whether hybridization is an accidental consequence of evolution or if it is necessary for the creation and evolution of plant species; it has been argued that contemporary studies are part of an intellectual lineage that started with the work of Stebbins and Anderson.

Stebbins wrote several books during his time at UC Davis. These included his follow-up to ''Variation and Evolution'', '' Flowering Plants: Evolution Above the Species Level'', which was published in 1974, following his delivery of the Prather Lectures at Harvard. Stebbins discusses the origins, genetics and developmental biology of the angiosperm

Flowering plants are plants that bear flowers and fruits, and form the clade Angiospermae (), commonly called angiosperms. The term "angiosperm" is derived from the Greek words ('container, vessel') and ('seed'), and refers to those plants th ...

s. He argues for the role of adaptive radiation in the diversification of the angiosperms and the usefulness of applying our current understanding of species' genetics and ecology to gain knowledge about the evolution of ancient species. He also wrote ''Processes of Organic Evolution'', ''The Basis of Progressive Evolution'', ''Chromosomal Evolution in Plants'' and the textbook ''Evolution'' with co-authors Dobzhansky, Francisco Ayala and James W. Valentine. His last book, ''Darwin to DNA, Molecules to Humanity'' was published in 1982.

Stebbins was passionate about teaching evolution, advocating during the 1960s and 70s the teaching of Darwinian evolution in public schools. He worked closely with the Biological Sciences Curriculum Study

BSCS Science Learning, formerly known as Biological Sciences Curriculum Study (BSCS), is an educational center that develops curricular materials, provides educational support, and conducts research and evaluation in the fields of science and techn ...

to develop high school curricula based on evolution as the central unifying principle in biology. He also opposed scientific creationism groups. Stebbins was active in numerous science organizations—including the International Union of Biological Sciences, the Western Society of Naturalists, the Botanical Society of America, and the Society for the Study of Evolution—and served as President of the American Society of Naturalists. He was elected to the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nati ...

in 1952. Stebbins received numerous awards for his contributions to science: the National Medal of Science, the Gold Medal from the Linnean Society of London

The Linnean Society of London is a learned society dedicated to the study and dissemination of information concerning natural history, evolution, and taxonomy. It possesses several important biological specimen, manuscript and literature colle ...

, the Addison Emery Verrill Medal

The Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale University is among the oldest, largest, and most prolific university natural history museums in the world. It was founded by the philanthropist George Peabody in 1866 at the behest of his nephew Othn ...

from the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, and the John Frederick Lewis Award from the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and ...

in 1952. He was awarded the 1983 Leidy Award from the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia.

Stebbins was active in conservation issues in California during his later life. He established a California Native Plant Society branch in Sacramento in the early 1960s. Through the society, he created an active field trip program to increase interest in the native flora of California and to document rare plants. Stebbins was the state President of the Society during 1966. The society was instrumental in preventing the destruction of a beach on the Monterey Peninsula that he referred to as "Evolution Hill"—the area is now known as the S.F.B. Morse Botanical Area and is managed by the Del Monte Forest Foundation. He was a major contributor to the Society's 1996 book ''California's Wild Gardens: A Living Legacy''. Stebbins was instrumental in the establishment of the ''Inventory of Rare and Endangered Vascular Plants of California'' by the California Native Plant Society; it is still used by state and federal bodies in the United States for conservation policy-making. Stebbins was also a member of the Sierra Club

The Sierra Club is an environmental organization with chapters in all 50 United States, Washington D.C., and Puerto Rico. The club was founded on May 28, 1892, in San Francisco, California, by Scottish-American preservationist John Muir, who be ...

.

During his tenure at UC Davis, he trained more than 30 graduate students in genetics, developmental biology and agricultural science. In 1973, Stebbins gave his last lectures at UC Davis and was made professor emeritus

''Emeritus'' (; female: ''emerita'') is an adjective used to designate a retired chair, professor, pastor, bishop, pope, director, president, prime minister, rabbi, emperor, or other person who has been "permitted to retain as an honorary title ...

. Following his retirement, he travelled widely, taught, and visited colleagues for the next 20 years. His last paper, "A brief summary of my ideas on evolution", was published in the '' American Journal of Botany'' in 1999. The same year he was co-recipient with Ernst Mayr of the Distinguished Service award from the American Institute of Biological Sciences. A colloquium was held by the National Academies of Science in 2000 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the publication of ''Variation and Evolution in Plants''. Stebbins died in his home in Davis the same year from a cancer-related illness. Stebbins was honored at a Unitarian memorial service—he had been active in the church in his later years following his 1958 marriage to his second wife, Barbara Monaghan Stebbins.Pioneering Evolutionist Ledyard Stebbins Dies at Age 94January 20, 2000, UC Davis News Service His ashes were scattered at

Stebbins Cold Canyon Reserve

Stebbins Cold Canyon Reserve is a unit of the University of California Natural Reserve System and is administered by the University of California, Davis. It is within the Blue Ridge Berryessa Natural Area, in the Northern Inner California Coast Ra ...

.

Legacy

Stebbins made an enormous contribution to scientific thought and botany by developing an intellectual framework for studying plant evolution including modern concepts of plant species and plant speciation. His contributions to the literature of plant evolutionary biology, in addition to his seven books, include more than 280 journal articles and book chapters, a compilation of which were published in 2004—''The Scientific Papers of G. Ledyard Stebbins (1929–2000)'' (). Betty Smocovitis, a historian of science who is preparing a book-length biography on Stebbins, described Stebbins's scientific contribution as follows:In science as in everything, small-scale synthesizers usually get credit from all constituent parties, but truly great synthesizers can fall between the cracks in the cycle of scientific credit. Ledyard Stebbins was in the latter category; neither fish nor fowl, he frequently failed to receive credit for work in some areas, usually at the hands of narrower colleagues. Few, however, have challenged his contributions to plant evolutionary biology, nor questioned his ability to synthesize disparate literature into a coherent framework. His ability to read quickly, recognize novel insights, digest new material, and then integrate the knowledge were the hallmarks of his scientific work style. He was a masterful synthesizer and master of the review essay or synthetic thought piece.In 1980, the University of California, Davis, named a parcel of land near Lake Berryessa, California, the

Stebbins Cold Canyon Reserve

Stebbins Cold Canyon Reserve is a unit of the University of California Natural Reserve System and is administered by the University of California, Davis. It is within the Blue Ridge Berryessa Natural Area, in the Northern Inner California Coast Ra ...

in recognition of his contributions to conservation and evolutionary science. The reserve is part of the University of California Natural Reserve System

The University of California Natural Reserve System (UCNRS) is a system of protected areas throughout California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Co ...

. The UC Davis Herbarium maintains a G. Ledyard Stebbins student grant program, established in celebration of his 90th birthday.

''Calystegia stebbinsii

''Calystegia stebbinsii'' is a rare species of morning glory known by the common name Stebbins' false bindweed. It is Endemism, endemic to the Sierra Nevada (U.S.), Sierra Nevada foothills and the Tehachapi Mountains in Kern County, of California ...

'', '' Lomatium stebbinsii'', ''Harmonia stebbinsii

''Harmonia stebbinsii'' (Synonym (taxonomy), syn. ''Madia stebbinsii'') is a species of flowering plant in the family Asteraceae known by the common name Stebbins' tarweed, or Stebbins' madia. It is Endemism, endemic to northern California, where ...

'', ''Elymus stebbinsii

''Elymus stebbinsii'' is a species of wild rye known by the common name Parish wheatgrass. It is endemic to California, where it grows in the forests and chaparral of many of the coastal and inland mountain ranges. It is a perennial grass growing ...

'', '' Lewisia stebbinsii'' and others are named in honor of Stebbins.

Key publications

*'' Variation and Evolution in Plants'' (1950) *''Processes of Organic Evolution'' (1966) *''The Basis of Progressive Evolution'' (1969) *''Chromosomal Evolution in Higher Plants'' (1971) () * *''Evolution'' (1977) with Dobzhansky, Ayala and Valentine *''Darwin to DNA, Molecules to Humanity'' (1982) ()References

Bibliography

* * * * * Smocovitis, V. B. 2001. "Stebbins, G. Ledyard". ''American National Biography Online''. Oxford University Press. * Smocovitis, V. B. and F. J. Ayala. 2004.George Ledyard Stebbins, January 6, 1906–January 19, 2000

''Biographical Memoirs'', vol. 85, Washington DC: National Academies Press, pp. 1–24. * Stebbins, G. L. (V. C. Hollowell, V. B. Smocovitis and E. P. Duggan, editors). 2007. The Ladyslipper and I. Monographs in Systematic Botany from the Missouri Botanical Garden. Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis utobiography

External links

Full list of Stebbins' publications

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Stebbins, G. Ledyard Botanists with author abbreviations Evolutionary biologists 1906 births 2000 deaths Botanists active in California Botanists active in North America Modern synthesis (20th century) National Medal of Science laureates Foreign Members of the Royal Society University of California, Berkeley faculty University of California, Davis faculty Harvard University alumni Botanical Society of America People from St. Lawrence County, New York Deaths from cancer in California People from Carpinteria, California Scientists from California 20th-century American biologists 20th-century American botanists Scientists from New York (state) Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Members of the American Philosophical Society