George Bellamy Mackaness on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

George Bellamy Mackaness (20 August 1922 – 4 March 2007) was an Australian professor of

On returning to Australia, Mackeness moved to Canberra having been appointed to at first staff and then acting head of the Department of Experimental Pathology at the

On returning to Australia, Mackeness moved to Canberra having been appointed to at first staff and then acting head of the Department of Experimental Pathology at the

In 1965 he became director of the

In 1965 he became director of the

microbiology

Microbiology () is the scientific study of microorganisms, those being unicellular (single cell), multicellular (cell colony), or acellular (lacking cells). Microbiology encompasses numerous sub-disciplines including virology, bacteriology, prot ...

, immunologist, writer and administrator, who researched and described the life history of the macrophage

Macrophages (abbreviated as M φ, MΦ or MP) ( el, large eaters, from Greek ''μακρός'' (') = large, ''φαγεῖν'' (') = to eat) are a type of white blood cell of the immune system that engulfs and digests pathogens, such as cancer cel ...

. He showed that by infecting mice with intracellular bacteria, macrophages could be activated to attack other bacteria, triggering further research on "macrophage activation", a term he has come to be associated with.

Mackaness completed his early medical training at Sydney Hospital

Sydney Hospital is a major hospital in Australia, located on Macquarie Street in the Sydney central business district. It is the oldest hospital in Australia, dating back to 1788, and has been at its current location since 1811. It first rece ...

. After the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

he moved to London to study pathology

Pathology is the study of the causes and effects of disease or injury. The word ''pathology'' also refers to the study of disease in general, incorporating a wide range of biology research fields and medical practices. However, when used in ...

before taking up a graduate post at Howard Florey

Howard Walter Florey, Baron Florey (24 September 189821 February 1968) was an Australian pharmacologist and pathologist who shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1945 with Sir Ernst Chain and Sir Alexander Fleming for his role in ...

's laboratory in Oxford. There he studied the role of monocytes

Monocytes are a type of leukocyte or white blood cell. They are the largest type of leukocyte in blood and can differentiate into macrophages and conventional dendritic cells. As a part of the vertebrate innate immune system monocytes also infl ...

and macrophages in killing ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis

''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (M. tb) is a species of pathogenic bacteria in the family Mycobacteriaceae and the causative agent of tuberculosis. First discovered in 1882 by Robert Koch, ''M. tuberculosis'' has an unusual, waxy coating on its c ...

''. Simultaneously he worked on anti-tuberculous medicines, including streptomycin

Streptomycin is an antibiotic medication used to treat a number of bacterial infections, including tuberculosis, ''Mycobacterium avium'' complex, endocarditis, brucellosis, ''Burkholderia'' infection, plague, tularemia, and rat bite fever. Fo ...

and isoniazid

Isoniazid, also known as isonicotinic acid hydrazide (INH), is an antibiotic used for the treatment of tuberculosis. For active tuberculosis it is often used together with rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and either streptomycin or ethambutol. For l ...

, before receiving his DPhil in 1953. Shortly after returning to Australia, Mackeness was appointed acting head of the Department of Experimental Pathology at the John Curtin School of Medical Research

The John Curtin School of Medical Research (JCSMR) is an Australian multidisciplinary translational medical research institute and postgraduate education centre that forms part of the Australian National University (ANU) in Canberra. The school w ...

(JCSMR), where his observations led him to describe "acquired cellular resistance" and that specifically committed T-cells

A T cell is a type of lymphocyte. T cells are one of the important white blood cells of the immune system and play a central role in the adaptive immune response. T cells can be distinguished from other lymphocytes by the presence of a T-cell rec ...

reacting with antigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule or molecular structure or any foreign particulate matter or a pollen grain that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response. ...

, activated the macrophages. He had by this time completed a sabbatical to the Rockefeller Institute, and had written extensively on renin

Renin (etymology and pronunciation), also known as an angiotensinogenase, is an aspartic protease protein and enzyme secreted by the kidneys that participates in the body's renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS)—also known as the r ...

and high blood pressure

Hypertension (HTN or HT), also known as high blood pressure (HBP), is a long-term medical condition in which the blood pressure in the arteries is persistently elevated. High blood pressure usually does not cause symptoms. Long-term high bl ...

.

In 1962 he was appointed professor in microbiology at the University of Adelaide

The University of Adelaide (informally Adelaide University) is a public research university located in Adelaide, South Australia. Established in 1874, it is the third-oldest university in Australia. The university's main campus is located on N ...

. Later, he transferred to the Trudeau Institute

The Trudeau Institute is an independent, not-for-profit, biomedical research center located on a campus in Saranac Lake, New York. Its scientific mission is to make breakthrough discoveries that lead to improved human health.

Trudeau scientists ...

in the US before moving to the Squibb Institute for Medical Research, where he played an important part in getting the first ACE inhibitor

Angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors) are a class of medication used primarily for the treatment of hypertension, high blood pressure and heart failure. They work by causing relaxation of blood vessels as well as a decrease i ...

, captopril

Captopril, sold under the brand name Capoten among others, is an ACE inhibitor, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor used for the treatment of hypertension and some types of congestive heart failure. Captopril was the first oral ACE inh ...

, licensed.

Early life and education

George Bellamy Mackaness was born on 20 August 1922 in Sydney, Australia, the third child of James Vincent Mackaness, a Sussex Street grocer, and his wife Eleanor Frances Bellamy Mackaness. He used his name in full to distinguish himself from his uncle, George Mackaness, an author and historian. He attendedFort Street High School

Fort Street High School (FSHS) is a Education in Australia#Government schools, government-funded Mixed-sex school, co-educational Selective school (New South Wales), academically selective secondary school, secondary day school, located in Petersh ...

, before gaining admission to study medicine at the University of Sydney

The University of Sydney (USYD), also known as Sydney University, or informally Sydney Uni, is a public research university located in Sydney, Australia. Founded in 1850, it is the oldest university in Australia and is one of the country's si ...

, from where he graduated with a Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery

Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery ( la, Medicinae Baccalaureus, Baccalaureus Chirurgiae; abbreviated most commonly MBBS), is the primary medical degree awarded by medical schools in countries that follow the tradition of the United King ...

.

Early career

Mackaness completed a one year residency inmedicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pract ...

at Sydney Hospital

Sydney Hospital is a major hospital in Australia, located on Macquarie Street in the Sydney central business district. It is the oldest hospital in Australia, dating back to 1788, and has been at its current location since 1811. It first rece ...

followed by a year in pathology at the hospital's Kanematsu Institute, before becoming a demonstrator in pathology. After WWII he moved to London and completed a Diploma in Clinical Pathology (DCP) at the University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in post-nominals) is a federal public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The university was established by royal charter in 1836 as a degree ...

. In 1948 he matriculated from Lincoln College, Oxford.

Sir William Dunn School of Pathology

Howard Florey

Howard Walter Florey, Baron Florey (24 September 189821 February 1968) was an Australian pharmacologist and pathologist who shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1945 with Sir Ernst Chain and Sir Alexander Fleming for his role in ...

offered Mackaness a job in his laboratory at the Sir William Dunn School of Pathology

The Sir William Dunn School of Pathology is a department within the University of Oxford. Its research programme includes the cellular and molecular biology of pathogens, the immune response, cancer and cardiovascular disease. It teaches undergra ...

in Oxford. There, Mackeness worked for his DPhil

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, Ph.D., or DPhil; Latin: or ') is the most common degree at the highest academic level awarded following a course of study. PhDs are awarded for programs across the whole breadth of academic fields. Because it is a ...

alongside James Learmonth Gowans

Sir James Learmonth Gowans (7 May 1924 – 1 April 2020) was a British physician and immunologist. In 1945, while studying medicine at King's College Hospital, he assisted at the liberated Bergen-Belsen concentration camp as a voluntary m ...

and later Henry Harris. Mackaness's main study for his thesis was on the role of monocytes

Monocytes are a type of leukocyte or white blood cell. They are the largest type of leukocyte in blood and can differentiate into macrophages and conventional dendritic cells. As a part of the vertebrate innate immune system monocytes also infl ...

and macrophages in killing ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis

''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (M. tb) is a species of pathogenic bacteria in the family Mycobacteriaceae and the causative agent of tuberculosis. First discovered in 1882 by Robert Koch, ''M. tuberculosis'' has an unusual, waxy coating on its c ...

''. He showed that by infecting mice with intracellular bacteria, macrophages could be activated to attack other bacteria. It resulted in an increase in research on "macrophage activation", a term he has become associated with. Discovering antibiotics was his side interest and his work in this field later earned him a fellowship to the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

. At Florey's suggestion, Mackaness simultaneously took to studying anti-tuberculous medicines, including streptomycin and isoniazid. His investigations into how isoniazid

Isoniazid, also known as isonicotinic acid hydrazide (INH), is an antibiotic used for the treatment of tuberculosis. For active tuberculosis it is often used together with rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and either streptomycin or ethambutol. For l ...

acted in tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

, published in 1952, were some of the first on this topic. He used the techniques he had developed during his study of the life history of monocytes and macrophages to show that for a drug to be effective against tuberculosis, it had to be effective inside the macrophage, and showed that isoniazid entered the macrophage to be active against ''M. tuberculosis''. He delayed completing his thesis while working on isoniazid and received his DPhil in 1953. A year later, he moved back to Australia.

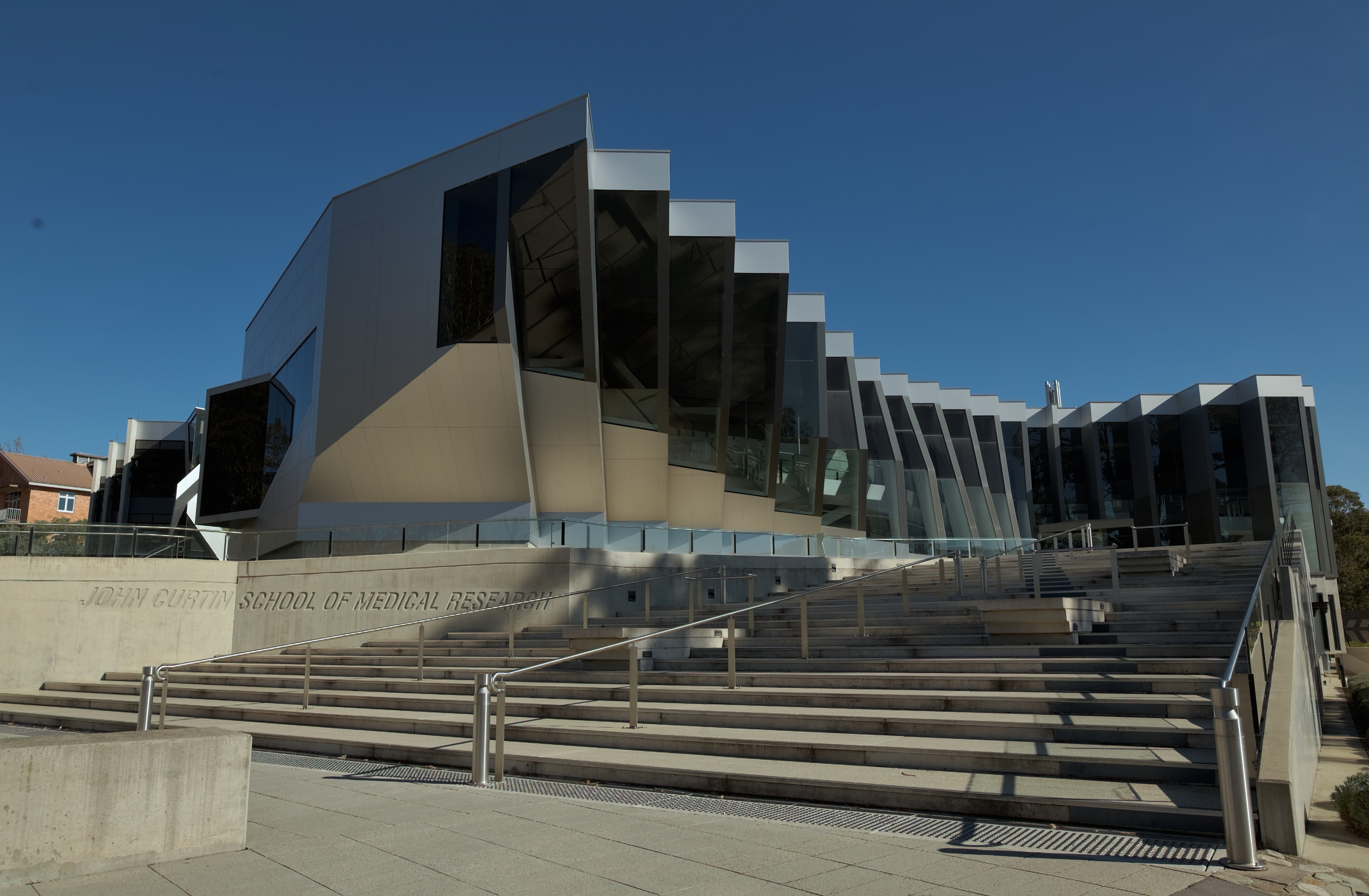

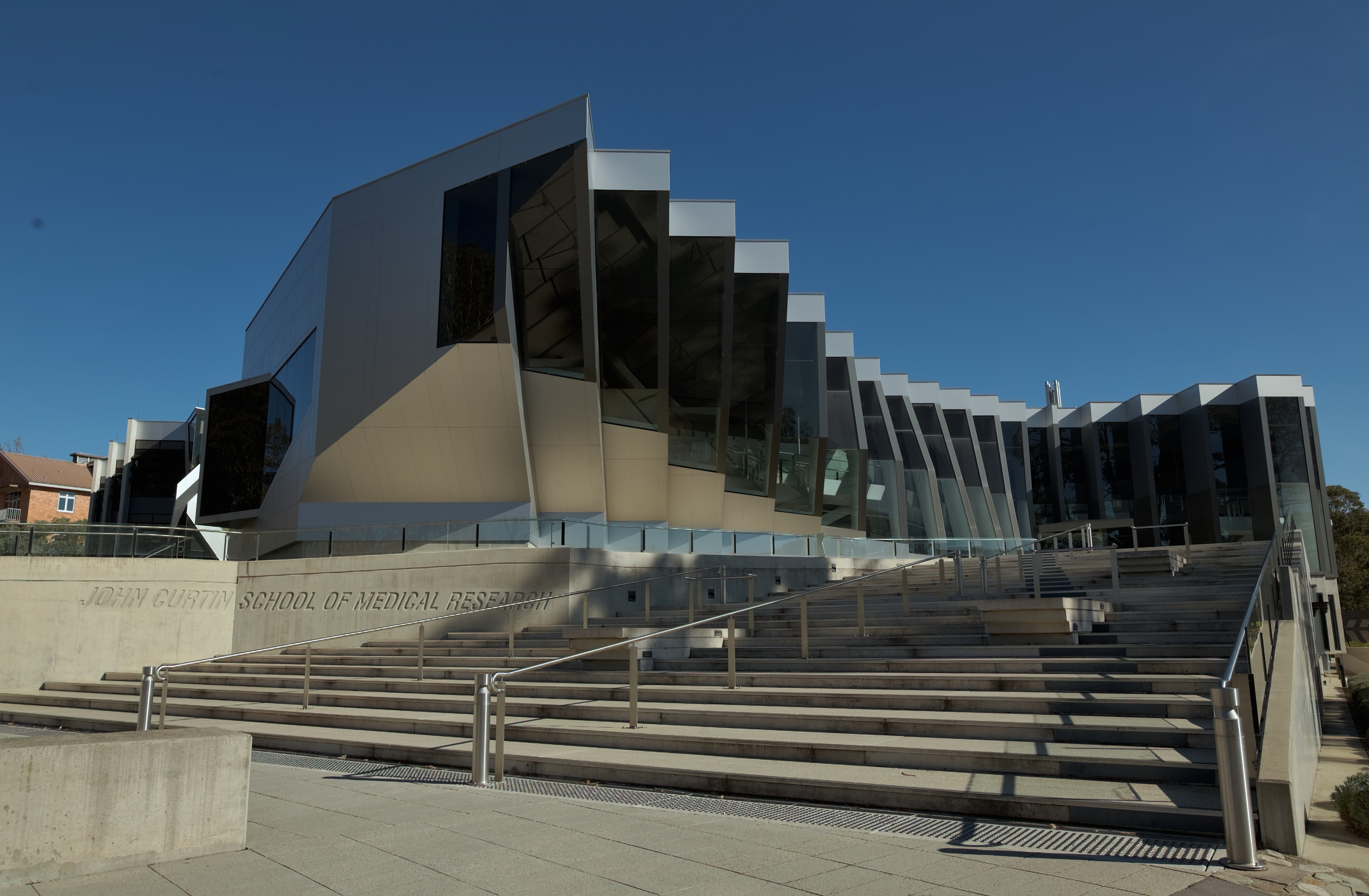

John Curtin School of Medical Research

On returning to Australia, Mackeness moved to Canberra having been appointed to at first staff and then acting head of the Department of Experimental Pathology at the

On returning to Australia, Mackeness moved to Canberra having been appointed to at first staff and then acting head of the Department of Experimental Pathology at the John Curtin School of Medical Research

The John Curtin School of Medical Research (JCSMR) is an Australian multidisciplinary translational medical research institute and postgraduate education centre that forms part of the Australian National University (ANU) in Canberra. The school w ...

(JCSMR), an institution he saw being planned by Florey while in Oxford.

In 1959 he took a sabbatical to the Rockefeller Institute, by which time he was professorial fellow, having written extensively on renin

Renin (etymology and pronunciation), also known as an angiotensinogenase, is an aspartic protease protein and enzyme secreted by the kidneys that participates in the body's renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS)—also known as the r ...

and hypertension. There he worked with René Dubos

René Jules Dubos (February 20, 1901 – February 20, 1982) was a French-American microbiologist, experimental pathologist, environmentalist, humanist, and winner of the Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction for his book ''So Human An Animal ...

, who had worked with Selman Waksman

Selman Abraham Waksman (July 22, 1888 – August 16, 1973) was a Jewish Russian-born American inventor, Nobel Prize laureate, biochemist and microbiologist whose research into the decomposition of organisms that live in soil enabled the discov ...

and had a quest to find cures for tuberculosis. Mackeness was set to buddy up with Jim Hirsch and focus on anti-infection immunity. In 1960 they published a paper on the phagocytosis of staphylococci.

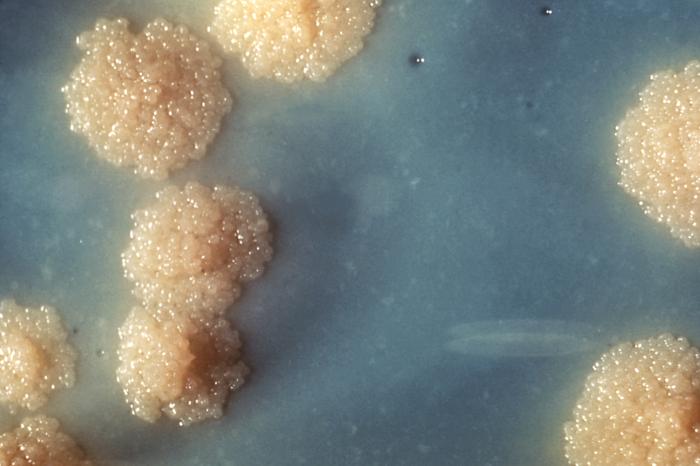

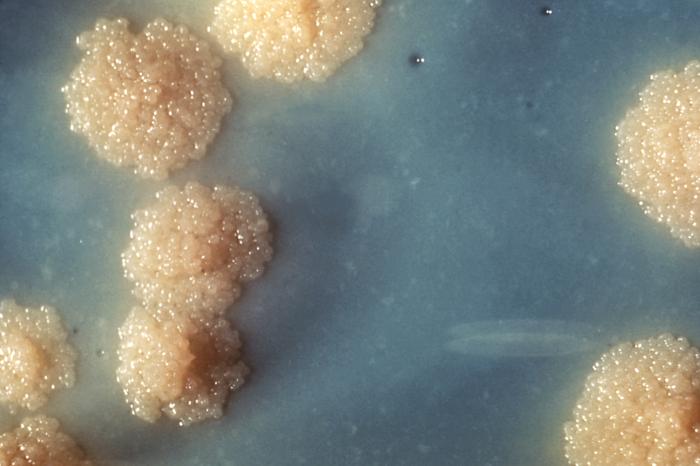

While at the JCSMR, he found that mice were good at producing an antibody-independent immune response to the bacteria ''Listeria monocytogenes

''Listeria monocytogenes'' is the species of pathogenic bacteria that causes the infection listeriosis. It is a facultative anaerobic bacterium, capable of surviving in the presence or absence of oxygen. It can grow and reproduce inside the host' ...

''. Once infected with ''L. monocytogenes'', the mice developed temporary protection to ''L. monocytogenes'', but also to other bacteria, an observation he termed "acquired cellular resistance", and he attributed this to macrophages. Compared to macrophages from uninfected mice, these macrophages could then be removed and were found to kill several other bacteria. The protection faded with time, but regained when the mice were re-challenged with the original bacteria. The macrophages were activated immediately. When challenged with other un-related bacteria, the macrophages did not respond. He concluded that the macrophage response was dependent on the particular original infection and the findings were published in ''The Journal of Experimental Medicine'' in 1962 and 1964. His experiments have since been described as "classic". With his colleagues, he confirmed that specifically committed T-lymphocytes

A T cell is a type of lymphocyte. T cells are one of the important white blood cells of the immune system and play a central role in the adaptive immune response. T cells can be distinguished from other lymphocytes by the presence of a T-cell rec ...

reacting with antigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule or molecular structure or any foreign particulate matter or a pollen grain that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response. ...

, activated the macrophages.

University of Adelaide

His 1962 paper titled "Cellular Resistance to Infection", published in the ''Journal of Experimental Medicine

''Journal of Experimental Medicine'' is a monthly peer-reviewed medical journal published by Rockefeller University Press that publishes research papers and commentaries on the physiological, pathological, and molecular mechanisms that encompass th ...

'', played a significant part in earning him a professorship in microbiology at the University of Adelaide

The University of Adelaide (informally Adelaide University) is a public research university located in Adelaide, South Australia. Established in 1874, it is the third-oldest university in Australia. The university's main campus is located on N ...

.

Later career

In 1965 he became director of the

In 1965 he became director of the Trudeau Institute

The Trudeau Institute is an independent, not-for-profit, biomedical research center located on a campus in Saranac Lake, New York. Its scientific mission is to make breakthrough discoveries that lead to improved human health.

Trudeau scientists ...

, where over the subsequent ten years he appointed and led staff on work relating to cell-mediated immunity

Cell-mediated immunity or cellular immunity is an immune response that does not involve antibodies. Rather, cell-mediated immunity is the activation of phagocytes, antigen-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocytes, and the release of various cytokines in ...

to infection and, later, cancer.

He became president of the Squibb Institute for Medical Research in New Jersey in 1976. While at Squibb, the FDA had denied a license to the first ACE inhibitor, captopril, due the side effects being too unacceptable, particularly the risk of producing a severe low blood count. Mackaness persuaded the company to reduce the dose by half, resulting in FDA approval and significant profits for the Squibb. His last publication before retirement was a review article on ACE inhibitors.

Following retirement in 1985, he moved to Seabrook Island, South Carolina, to be near his son and three granddaughters. He later developed Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease that usually starts slowly and progressively worsens. It is the cause of 60–70% of cases of dementia. The most common early symptom is difficulty in remembering recent events. As t ...

.

Personal and family

In 1945, after graduating, Mackaness married Gwynneth Patterson, an army nurse, who he met during the early years of theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, whilst a medical student. They had one son, Miles.

Awards and honours

He was awarded thePaul Ehrlich and Ludwig Darmstaedter Prize

The Paul Ehrlich and Ludwig Darmstaedter Prize is an annual award bestowed by the since 1952 for investigations in medicine. It carries a prize money of 120,000 Euro. The prize awarding ceremony is traditionally held on March 14, the birthday of N ...

in 1975. In 1976 he was elected fellow of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

. In 1998 he received the Novartis Prizes for Immunology

The Novartis Prizes for Immunology were established in 1990 by Sandoz to honour outstanding research in immunology, and expanded to their current form in 1992. Prizes for basic and clinical immunology are awarded every 3 years. A special prize was ...

and he was also elected a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Death

His death on 4 March 2007 inCharleston

Charleston most commonly refers to:

* Charleston, South Carolina

* Charleston, West Virginia, the state capital

* Charleston (dance)

Charleston may also refer to:

Places Australia

* Charleston, South Australia

Canada

* Charleston, Newfoundlan ...

, South Carolina was followed a few days later by his wife's. Both had spent a year together at the same extended care facility.

Selected publications

* * (Co-author) * * * * * *References

Further reading

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Mackaness, George Bellamy 1922 births 2007 deaths Australian immunologists Australian microbiologists Australian pathologists Academic staff of the University of Adelaide Academic staff of the Australian National University