George B. McClellan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American soldier,

George Brinton McClellan was born in

George Brinton McClellan was born in

McClellan resigned his commission January 16, 1857, and, capitalizing on his experience with railroad assessment, became chief engineer and vice president of the

McClellan resigned his commission January 16, 1857, and, capitalizing on his experience with railroad assessment, became chief engineer and vice president of the

During the summer and fall, McClellan brought a high degree of organization to his new army, and greatly improved its morale with frequent trips to review and encourage his units. It was a remarkable achievement, in which he came to personify the Army of the Potomac and reaped the adulation of his men. He created defenses for Washington that were almost impregnable, consisting of 48 forts and strong points, with 480 guns manned by 7,200 artillerists. The Army of the Potomac grew in number from 50,000 in July to 168,000 in November, becoming the largest military force the United States had raised until that time. But this was also a time of tension in the high command, as he continued to quarrel frequently with the government and the general-in-chief, Lt. Gen. Scott, on matters of strategy. McClellan rejected the tenets of Scott's

During the summer and fall, McClellan brought a high degree of organization to his new army, and greatly improved its morale with frequent trips to review and encourage his units. It was a remarkable achievement, in which he came to personify the Army of the Potomac and reaped the adulation of his men. He created defenses for Washington that were almost impregnable, consisting of 48 forts and strong points, with 480 guns manned by 7,200 artillerists. The Army of the Potomac grew in number from 50,000 in July to 168,000 in November, becoming the largest military force the United States had raised until that time. But this was also a time of tension in the high command, as he continued to quarrel frequently with the government and the general-in-chief, Lt. Gen. Scott, on matters of strategy. McClellan rejected the tenets of Scott's

On November 1, 1861,

On November 1, 1861,

McClellan's army began to sail from

McClellan's army began to sail from  Lee continued his offensive at Gaines's Mill to the east. That night, McClellan decided to withdraw his army to a safer base, well below Richmond, on a portion of the James River that was under control of the Union Navy. In doing so, Lee had assumed that the Union army would withdraw to the east toward its existing supply base and McClellan's move to the south delayed Lee's response for at least 24 hours. Ethan Rafuse notes "McClellan's change of base to the James, however, thwarted Lee's attempt to do this. Not only did McClellan's decision allow the Federals to gain control of the time and place for the battles that took place in late June and early July, it enabled them to fight in a way that inflicted terrible beating on the Confederate army....More importantly, by the end of the Seven Days Battles, McClellan had dramatically improved his operational situation."

But McClellan was also tacitly acknowledging that he would no longer be able to

Lee continued his offensive at Gaines's Mill to the east. That night, McClellan decided to withdraw his army to a safer base, well below Richmond, on a portion of the James River that was under control of the Union Navy. In doing so, Lee had assumed that the Union army would withdraw to the east toward its existing supply base and McClellan's move to the south delayed Lee's response for at least 24 hours. Ethan Rafuse notes "McClellan's change of base to the James, however, thwarted Lee's attempt to do this. Not only did McClellan's decision allow the Federals to gain control of the time and place for the battles that took place in late June and early July, it enabled them to fight in a way that inflicted terrible beating on the Confederate army....More importantly, by the end of the Seven Days Battles, McClellan had dramatically improved his operational situation."

But McClellan was also tacitly acknowledging that he would no longer be able to  McClellan was also fortunate that the failure of the campaign left his army mostly intact, because he was generally absent from the fighting and neglected to name any second-in-command who might direct his retreat. Military historian Stephen W. Sears wrote, "When he deserted his army on the

McClellan was also fortunate that the failure of the campaign left his army mostly intact, because he was generally absent from the fighting and neglected to name any second-in-command who might direct his retreat. Military historian Stephen W. Sears wrote, "When he deserted his army on the

At the discovery of the Lost Order, McClellan's Assistant Adjutant General verified the signature and handwriting of the officer who wrote out the order, as he knew him well, so there was no doubt as to its authenticity. Within hours of receiving the order, McClellan dispatched some of his cavalry to assess whether The Confederates had moved in accordance with the order.

Still, historians – including

At the discovery of the Lost Order, McClellan's Assistant Adjutant General verified the signature and handwriting of the officer who wrote out the order, as he knew him well, so there was no doubt as to its authenticity. Within hours of receiving the order, McClellan dispatched some of his cavalry to assess whether The Confederates had moved in accordance with the order.

Still, historians – including

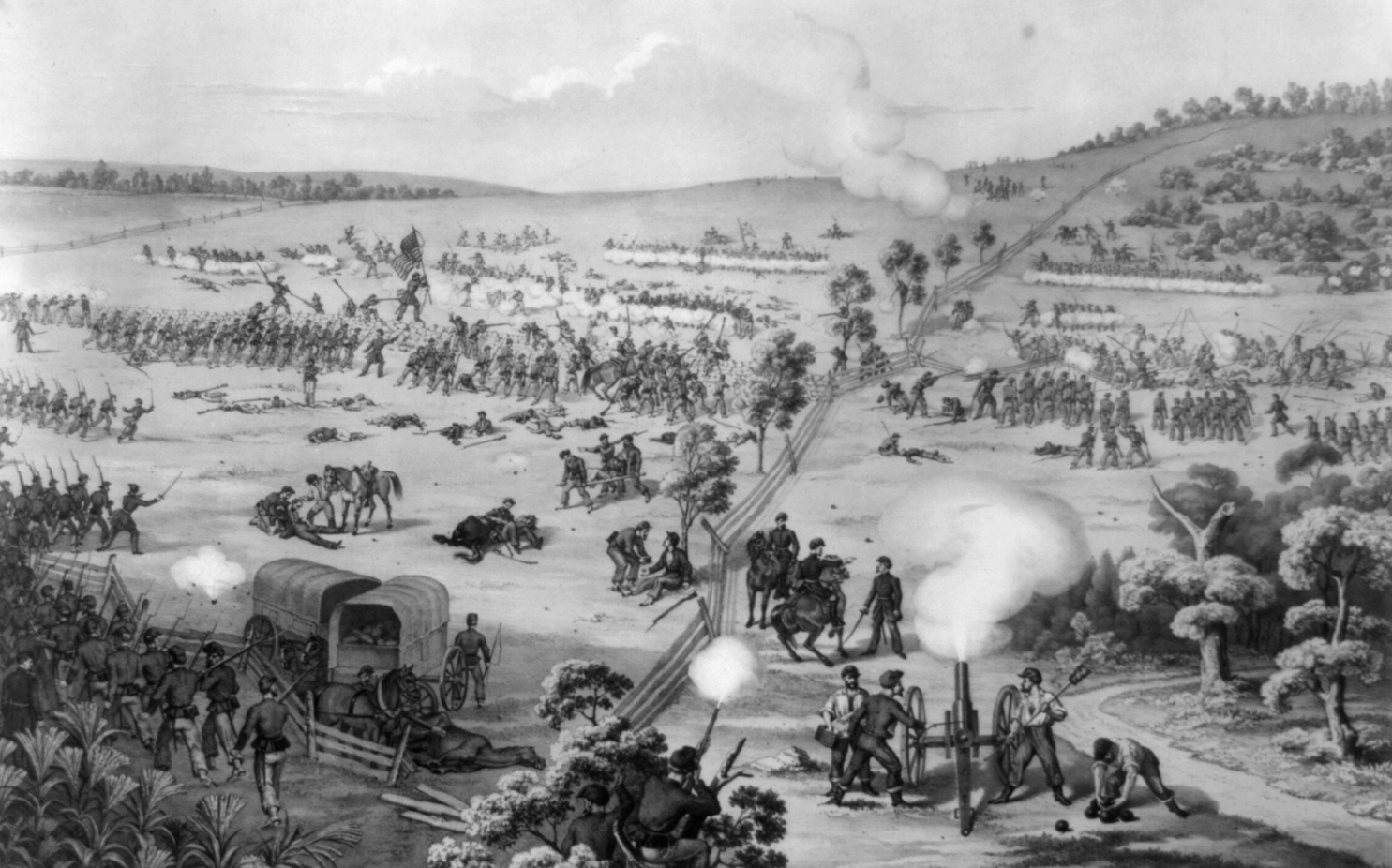

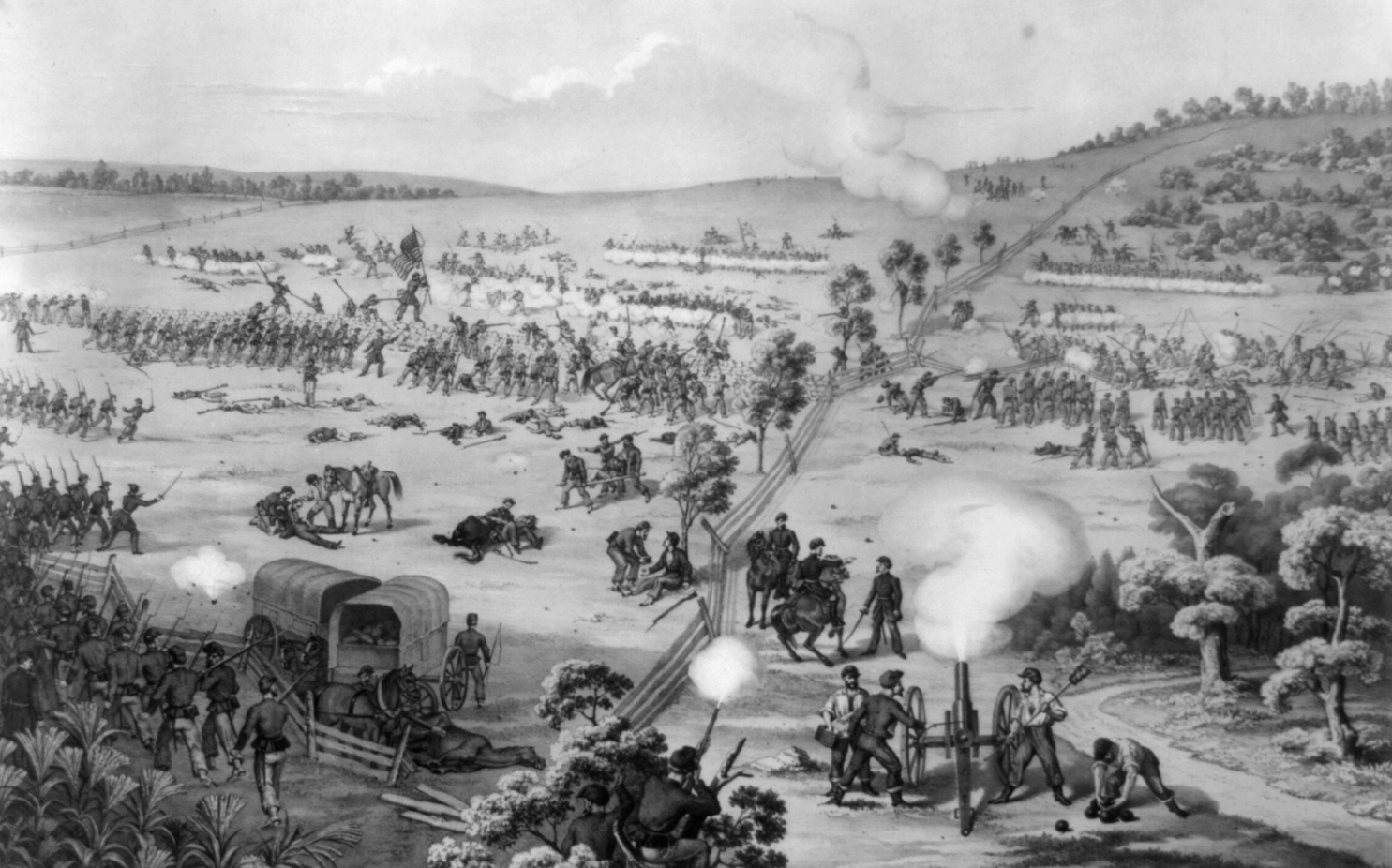

The

The  The battle was tactically inconclusive, with the Union suffering a higher overall number of casualties, although Lee technically was defeated because he withdrew first from the battlefield and retreated back to Virginia, and lost a larger percentage of his army than McClellan did. McClellan wired to Washington, "Our victory was complete. The enemy is driven back into Virginia." Yet there was obvious disappointment that McClellan had not crushed Lee, who was fighting with a smaller army with its back to the Potomac River. Although McClellan's subordinates can claim their share of responsibility for delays (such as

The battle was tactically inconclusive, with the Union suffering a higher overall number of casualties, although Lee technically was defeated because he withdrew first from the battlefield and retreated back to Virginia, and lost a larger percentage of his army than McClellan did. McClellan wired to Washington, "Our victory was complete. The enemy is driven back into Virginia." Yet there was obvious disappointment that McClellan had not crushed Lee, who was fighting with a smaller army with its back to the Potomac River. Although McClellan's subordinates can claim their share of responsibility for delays (such as

Secretary Stanton ordered McClellan to report to Trenton,

Secretary Stanton ordered McClellan to report to Trenton,  McClellan was nominated by the Democrats to run against

McClellan was nominated by the Democrats to run against

McClellan was appointed chief engineer of the New York City Department of Docks in 1870. Beginning in 1872, he also served as the president of the

McClellan was appointed chief engineer of the New York City Department of Docks in 1870. Beginning in 1872, he also served as the president of the

The New York ''Evening Post'' commented in McClellan's obituary, "Probably no soldier who did so little fighting has ever had his qualities as a commander so minutely, and we may add, so fiercely discussed." This fierce discussion has continued for over a century. McClellan is usually ranked in the lowest tier of Civil War generals. However, the debate over McClellan's ability and talents remains the subject of much controversy among Civil War and military historians. He has been universally praised for his organizational abilities and for his very good relations with his troops. They referred to him affectionately as "Little Mac"; others sometimes called him the "Young Napoleon". McClellan himself summed up his style of warfare in a draft of his memoirs:

Stephen Sears notes that

One of the reasons that McClellan's reputation has suffered is his own memoirs. Historian

The New York ''Evening Post'' commented in McClellan's obituary, "Probably no soldier who did so little fighting has ever had his qualities as a commander so minutely, and we may add, so fiercely discussed." This fierce discussion has continued for over a century. McClellan is usually ranked in the lowest tier of Civil War generals. However, the debate over McClellan's ability and talents remains the subject of much controversy among Civil War and military historians. He has been universally praised for his organizational abilities and for his very good relations with his troops. They referred to him affectionately as "Little Mac"; others sometimes called him the "Young Napoleon". McClellan himself summed up his style of warfare in a draft of his memoirs:

Stephen Sears notes that

One of the reasons that McClellan's reputation has suffered is his own memoirs. Historian

The Mexican War Diary of George B. McClellan

' (William Starr Myers, Editor). Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1917. * ''Bayonet Exercise, or School of the Infantry Soldier, in the Use of the Musket in Hand-to-Hand Conflicts'' (translated from the French of Gomard), 1852. Reissued as

Manual of Bayonet Exercise, Prepared for the Use of the Army of the United States

'. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1862. *

The Report of Captain George B. McClellan, One of the Officers Sent to the Seat of War in Europe, in 1855 and 1856

', 1857. Reissued as

The Armies of Europe, Comprising Descriptions in Detail of the Military Systems of England, France, Russia, Prussia, Austria, and Sardinia

'. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1861. *

European Cavalry, Including Details of the Organization of the Cavalry Service Among the Principal Nations of Europe

'. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1861. *

Exploration of the Red River of Louisiana in the Year 1852

' (with Randolph B. Marcy). Washington: A.O.P. Nicholson, 1854. * ''Regulations and Instructions for the Field Service of the United States Cavalry in Time of War'', 1861. Reissued as

Regulations and Instructions for the Field Service of the U.S. Cavalry in Time of War

'. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1862. *

McClellan's Own Story: The War for the Union, The Soldiers Who Fought It, The Civilians Who Directed It and His Relations to It and to Them

' (William C. Prime, Editor). New York: Charles L. Webster & Company, 1887. *

The Life, Campaigns, and Public Services of General George B McClellan

'. Philadelphia: T.B. Peterson & Brothers, 1864. *

The Democratic Platform, General McClellan's Letter of Acceptance

'. New York: Democratic National Committee, 1864. *

The Army of the Potomac, General McClellan's Report of Its Operations While Under His Command

'. New York: G.P. Putnam, 1864. *

Report of Major General George B McClellan, Upon the Organization of the Army of the Potomac and Its campaigns in Virginia and Maryland

'. Boston:

Letter of the Secretary of War by George Brinton McClellan

'. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1864. *

West Point Battle Monument, History of the Project to the Dedication of the Site

' (Oration of Major-General McClellan). New York: Sheldon & Co., 1864.

St. Petersburg, FL: Red and Black Publishers, 2008. . First published 1904 by Doubleday, Page & Co. * McPherson, James M. '' Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era''. Oxford History of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. . * McPherson, James M. ''Crossroads of Freedom: Antietam, The Battle That Changed the Course of the Civil War''. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. . * McPherson, James M. ''Tried by War: Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief''. New York: Penguin Press, 2008. . * Nevins, Allan. ''The War for the Union''. vol. 1, ''The Improvised War 1861–1862''. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1959. . * Rafuse, Ethan S. ''McClellan's War: The Failure of Moderation in the Struggle for the Union''. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005. . * Rowland, Thomas J. "George Brinton McClellan." In ''Leaders of the American Civil War: A Biographical and Historiographical Dictionary''. Edited by Charles F. Ritter and Jon L. Wakelyn. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1998. . * Rowland, Thomas J. ''George B. McClellan and Civil War History: In the Shadow of Grant and Sherman''. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1998. . * Sandburg, Carl. ''Storm Over the Land: A Profile of the Civil War''. New York: Harcourt Brace and Company, 1942. . * Sears, Stephen W. ''Controversies & Commanders: Dispatches from the Army of the Potomac''. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1999. . * Sears, Stephen W. ''George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon''. New York: Da Capo Press, 1988. . * Sears, Stephen W. ''Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam''. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1983. . * Sears, Stephen W. ''To the Gates of Richmond: The Peninsula Campaign''. Ticknor and Fields, 1992. . * Smith, Gustavus, Woodson. (2001) ''Company "A" Corps of Engineers, U.S.A., 1846–1848, in the Mexican War.'' Edited by Leonne M. Hudson, The Kent State University Press * Bonekemper, Edward H. ''McClellan and failure''. McFarland & Co, 2007 * Stotelmyer, Steven R. ''Too Useful to Sacrifice: Reconsidering George B. McClellan's Generalship in the Maryland Campaign from South Mountain to Antietam''. California: Savas Beatie, 2019.

Report of the Secretary of War Communicating the Report of Captain George B McClellan, One of the Officers Sent to the Seat of War in Europe in 1855 and 1856

'. Washington: A.O.P. Nicholson, 1857. * Hearn, Chester G. ''Lincoln and McClellan at War''. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2012. . * Hillard, George S.

Life and Campaigns of George B. McClellan, Major-General U.S. Army

'. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1864. * Leigh, Philip "Lee's Lost Dispatch and Other Civil War Controversies". Yardley, Penna.: Westholme Publishing, 2015. . * Melville, Herman. ''Battle-Pieces and Aspects of the War

The Victor of Antietam

'. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1866.

George B. McClellan in ''Encyclopedia Virginia''

Georgia's Blue and Gray Trail McClellan timeline

Lincoln and Lee at Antietam

Mr. Lincoln and New York: George B. McClellan

* Marcy, Randolph B, assisted by McClellan, George B., ttps://web.archive.org/web/20060329165243/http://texashistory.unt.edu/permalink/meta-pth-6105 ''Exploration of the Red River of Louisiana, in the year 1852''hosted by th

Portal to Texas History

McClellan's May 30th, 1885 Decoration Day Oration

(Lowell ''Daily Courier'', June 5, 1885)

Biography of George B. McClellan

New Jersey Governor George Brinton McClellan

"L'il Mac" George McClellan

Song parody

American Heritage on George McClellan's appointment

''The Mexican War diary of George B. McClellan'' at archive.org

Abraham Lincoln and George B. McClellan

Newspaper articles about reaction to Lincoln appointing McClellan head of the Army of the Potomac

* * , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:McClellan, George B. 1826 births 1885 deaths American military personnel of the Mexican–American War American people of Scottish descent American Presbyterians Burials in New Jersey Democratic Party (United States) presidential nominees Democratic Party governors of New Jersey McClellan family Members of the Aztec Club of 1847 New York State Superintendents of Public Works People from Orange, New Jersey People from West Orange, New Jersey People of New Jersey in the American Civil War People of Ohio in the American Civil War Politicians from Philadelphia Union Army generals United States Military Academy alumni Candidates in the 1864 United States presidential election Commanding Generals of the United States Army University of Pennsylvania alumni 19th-century American politicians Bourbon Democrats

Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

Union general, civil engineer, railroad executive, and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey

The governor of New Jersey is the head of government of New Jersey. The office of governor is an elected position with a four-year term. There is a two consecutive term term limit, with no limitation on non-consecutive terms. The official res ...

. A graduate of West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

, McClellan served with distinction during the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

and later left the Army to serve as an executive and engineer on railroads until the outbreak of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

Early in the conflict, McClellan was appointed to the rank of major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

and played an important role in raising a well-trained and disciplined army, which would become the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confedera ...

in the Eastern Theater; he served a brief period (November 1861 to March 1862) as Commanding General of the United States Army

The Commanding General of the United States Army was the title given to the service chief and highest-ranking officer of the United States Army (and its predecessor the Continental Army), prior to the establishment of the Chief of Staff of the ...

of the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

.

McClellan organized and led the Union army in the Peninsula Campaign in southeastern Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

from March through July 1862. It was the first large-scale offensive in the Eastern Theater. Making an amphibious clockwise turning movement around the Confederate Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting ...

in northern Virginia, McClellan's forces turned west to move up the Virginia Peninsula, between the James River and York River, landing from Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the ...

, with the Confederate capital, Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

, as their objective. Initially, McClellan was somewhat successful against General Joseph E. Johnston

Joseph Eggleston Johnston (February 3, 1807 – March 21, 1891) was an American career army officer, serving with distinction in the United States Army during the Mexican–American War (1846–1848) and the Seminole Wars. After Virginia secede ...

, but the emergence of General Robert E. Lee to command the Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most oft ...

turned the subsequent Seven Days Battles

The Seven Days Battles were a series of seven battles over seven days from June 25 to July 1, 1862, near Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. Confederate General Robert E. Lee drove the invading Union Army of the Potomac, command ...

into a Union defeat. However, historians note that Lee's victory was in many ways pyrrhic

A pyrrhic (; el, πυρρίχιος ''pyrrichios'', from πυρρίχη ''pyrrichē'') is a metrical foot used in formal poetry. It consists of two unaccented, short syllables. It is also known as a dibrach.

Poetic use in English

Tennyson us ...

as he failed to destroy the Army of the Potomac and suffered a bloody repulse at Malvern Hill.

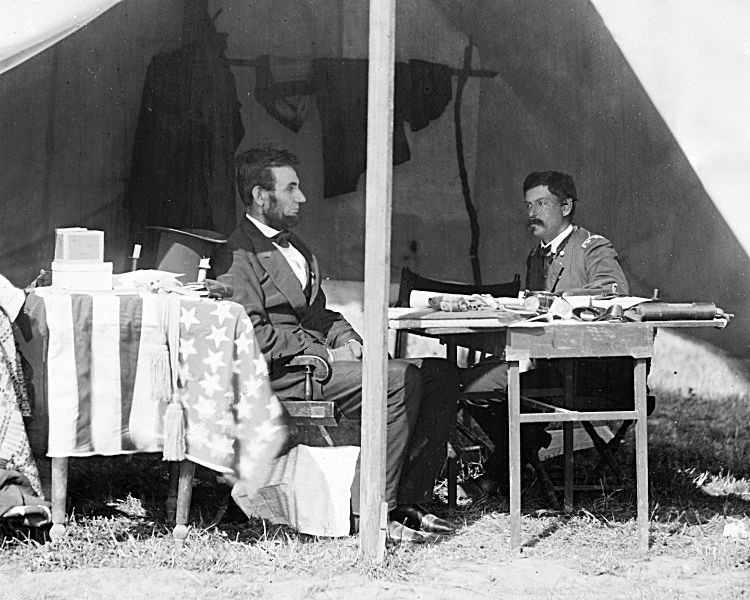

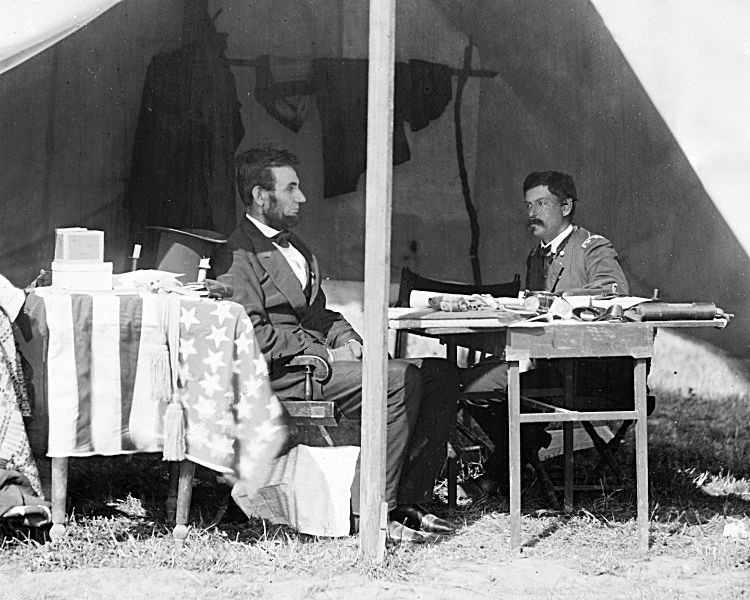

General McClellan and President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

developed a mutual distrust, and McClellan was privately derisive of Lincoln. McClellan was removed from command in November in the aftermath of the 1862 midterm elections. A major contributing factor in this decision was McClellan's failure to pursue Lee's army following the tactically inconclusive but strategic Union victory at the Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam (), or Battle of Sharpsburg particularly in the Southern United States, was a battle of the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, between Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union G ...

outside Sharpsburg, Maryland

Sharpsburg is a town in Washington County, Maryland. The town is approximately south of Hagerstown. Its population was 705 at the 2010 census.

During the American Civil War, the Battle of Antietam, sometimes referred to as the Battle of Sharpsb ...

.

McClellan never received another field command and went on to become the unsuccessful Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

nominee in the 1864 presidential election against the Republican Lincoln. The effectiveness of his campaign was damaged when he repudiated his party's platform, which promised an end to the war and negotiations with the Confederacy. He served as the 24th Governor of New Jersey

The governor of New Jersey is the head of government of New Jersey. The office of governor is an elected position with a four-year term. There is a two consecutive term term limit, with no limitation on non-consecutive terms. The official res ...

from 1878 to 1881; he eventually became a writer, and vigorously defended his Civil War conduct.

Early life and career

George Brinton McClellan was born in

George Brinton McClellan was born in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

on December 3, 1826, the son of a prominent surgeon, Dr. George McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American soldier, Civil War Union general, civil engineer, railroad executive, and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey. A graduate of West Point, McCl ...

, the founder of Jefferson Medical College

Thomas Jefferson University is a private research university in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Established in its earliest form in 1824, the university officially combined with Philadelphia University in 2017. To signify its heritage, the univer ...

. His father's family was of Scottish and English heritage. His mother was Elizabeth Sophia Steinmetz Brinton McClellan (1800–1889), daughter of a leading Pennsylvania family, a woman noted for her "considerable grace and refinement." Her father was of English origin, while her mother was Pennsylvania Dutch

The Pennsylvania Dutch ( Pennsylvania Dutch: ), also known as Pennsylvania Germans, are a cultural group formed by German immigrants who settled in Pennsylvania during the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. They emigrated primarily from German-spe ...

. The couple had five children: Frederica, John, George, Arthur and Mary. One of McClellan's great-grandfathers was Samuel McClellan

Samuel McClellan (January 4, 1730 – October 17, 1807) was an American brigadier general in the American Revolutionary War. He was born in Worcester, Massachusetts.

Samuel McClellan served as Ensign and Lieutenant in the French and Indian War ...

of Woodstock, Connecticut

Woodstock is a New England town, town in Windham County, Connecticut, Windham County, Connecticut, United States. The population was 8,221 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census.

History

17th century

In the mid-17th century, John Eliot (m ...

, a brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

who served during the Revolutionary War.

McClellan initially intended to follow his father into the medical profession, and attended a private academy, which was followed by enrollment in a private preparatory school for the University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (also known as Penn or UPenn) is a private research university in Philadelphia. It is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and is ranked among the highest-regarded universitie ...

. He began attending the university in 1840, when he was 14 years old, resigning himself to the study of law after his family decided that medical educations for both McClellan and his older brother John were too expensive. After two years at the university, he changed his goal to military service. With the assistance of his father's letter to President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

John Tyler

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 – January 18, 1862) was the tenth president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president dire ...

, McClellan was accepted at the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a fort, since it sits on strategic high groun ...

in 1842 at the age of 15, with the academy waiving its usual minimum age of 16.

At West Point, he was an energetic and ambitious cadet, deeply interested in the teachings of Dennis Hart Mahan

Dennis Hart Mahan (Mă-hăn) əˈhæn(April 2, 1802 – September 16, 1871) was a noted American military theorist, civil engineer and professor at the United States Military Academy at West Point from 1824–1871. He was the father of Amer ...

and the theoretical strategic principles of Antoine-Henri Jomini

Antoine-Henri Jomini (; 6 March 177922 March 1869) was a Swiss military officer who served as a general in French and later in Russian service, and one of the most celebrated writers on the Napoleonic art of war. Jomini's ideas are a staple at ...

. His closest friends were aristocratic southerners including George Pickett

George Edward Pickett (January 16,Military records cited by Eicher, p. 428, and Warner, p. 239, list January 28. The memorial that marks his gravesite in Hollywood Cemetery lists his birthday as January 25. Thclaims to have accessed the baptism ...

, Dabney Maury, Cadmus Wilcox

Cadmus Marcellus Wilcox (May 20, 1824 – December 2, 1890) was a career United States Army officer who served in the Mexican–American War and also was a Confederate general during the American Civil War.

Early life and career

Wilcox was ...

, and A. P. Hill. These associations gave McClellan what he considered to be an appreciation of the southern mind and an understanding of the political and military implications of the sectional differences in the United States that led to the Civil War. He graduated at age 19 in 1846, second in his class of 59 cadets, losing the top position to Charles Seaforth Stewart only because of inferior drawing skills. He was commissioned a brevet

Brevet may refer to:

Military

* Brevet (military), higher rank that rewards merit or gallantry, but without higher pay

* Brevet d'état-major, a military distinction in France and Belgium awarded to officers passing military staff college

* Aircre ...

second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army until ...

in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Mexican–American War 1846–1848

McClellan's first assignment was with a company of engineers formed at West Point, but he quickly received orders to sail for the Mexican War. He arrived near the mouth of theRio Grande

The Rio Grande ( and ), known in Mexico as the Río Bravo del Norte or simply the Río Bravo, is one of the principal rivers (along with the Colorado River) in the southwestern United States and in northern Mexico.

The length of the Rio G ...

in October 1846, well prepared for action with a double-barreled shotgun, two pistols, a saber, a dress sword, and a Bowie knife. He complained that he had arrived too late to take any part in the American victory at Monterrey

Monterrey ( , ) is the capital and largest city of the northeastern state of Nuevo León, Mexico, and the third largest city in Mexico behind Guadalajara and Mexico City. Located at the foothills of the Sierra Madre Oriental, the city is anchor ...

in September. During a temporary armistice in which the forces of Gen. Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader who served as the 12th president of the United States from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army, rising to th ...

awaited action, McClellan was stricken with dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

and malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

, which kept him in the hospital for nearly a month. Malaria would recur in later years; he called it his "Mexican disease." He served as an engineering officer during the war, was frequently subject to enemy fire, and was appointed a brevet first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a s ...

for his services at Contreras and Churubusco and to captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

for his service at Chapultepec

Chapultepec, more commonly called the "Bosque de Chapultepec" (Chapultepec Forest) in Mexico City, is one of the largest city parks in Mexico, measuring in total just over 686 hectares (1,695 acres). Centered on a rock formation called Chapultep ...

. He performed reconnaissance missions for Maj. Gen.

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

, a close friend of McClellan's father.

McClellan's experiences in the war would shape his military and political life. He learned that flanking movements (used by Scott at Cerro Gordo) are often better than frontal assaults, and the value of siege operations (Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

). He witnessed Scott's success in balancing political with military affairs and his good relations with the civil population as he invaded, enforcing strict discipline on his soldiers to minimize damage to property. McClellan also developed a disdain for volunteer soldiers and officers, particularly politicians who cared nothing for discipline and training.

Peacetime service

McClellan returned to West Point to command his engineering company, which was attached to the academy for the purpose of training cadets in engineering activities. He chafed at the boredom of peacetime garrison service, although he greatly enjoyed the social life. In June 1851, he was ordered toFort Delaware

Fort Delaware is a former harbor defense facility, designed by chief engineer Joseph Gilbert Totten and located on Pea Patch Island in the Delaware River.Dobbs, Kelli W., et al. During the American Civil War, the Union used Fort Delaware as ...

, a masonry work under construction on an island in the Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. From the meeting of its branches in Hancock (village), New York, Hancock, New York, the river flows for along the borders of N ...

, downriver from Philadelphia. In March 1852, he was ordered to report to Capt. Randolph B. Marcy

Randolph Barnes Marcy (April 9, 1812 – November 22, 1887) was an officer in the United States Army, chiefly noted for his frontier guidebook, the ''Prairie Traveler'' (1859), based on his own extensive experience of pioneering in the west. This p ...

at Fort Smith, Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the Osage ...

, to serve as second-in-command on an expedition to discover the sources of the Red River. By June the expedition reached the source of the north fork of the river and Marcy named a small tributary McClellan's Creek. Upon their arrival on July 28, they were astonished to find that they had been given up for dead. A sensational story had reached the press that the expedition had been ambushed by 2,000 Comanche

The Comanche or Nʉmʉnʉʉ ( com, Nʉmʉnʉʉ, "the people") are a Native American tribe from the Southern Plains of the present-day United States. Comanche people today belong to the federally recognized Comanche Nation, headquartered in La ...

s and killed to the last man. McClellan blamed the story on "a set of scoundrels, who seek to keep up agitation on the frontier in order to get employment from the Govt. in one way or other."

In the fall of 1852, McClellan published a manual on bayonet tactics that he had translated from the original French. He also received an assignment to the Department of Texas, with orders to perform a survey of Texas rivers and harbors. In 1853, he participated in the Pacific Railroad survey

The Pacific Railroad Surveys (1853–1855) were of a series of explorations of the American West designed to find and document possible routes for a transcontinental railroad across North America. The expeditions included surveyors, scientists, and ...

s, ordered by Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as a ...

, to select an appropriate route for the planned transcontinental railroad

A transcontinental railroad or transcontinental railway is contiguous railroad trackage, that crosses a continental land mass and has terminals at different oceans or continental borders. Such networks can be via the tracks of either a single ...

. McClellan surveyed the western portion of the northern corridor along the 47th and 49th parallels from St. Paul

Paul; grc, Παῦλος, translit=Paulos; cop, ⲡⲁⲩⲗⲟⲥ; hbo, פאולוס השליח (previously called Saul of Tarsus;; ar, بولس الطرسوسي; grc, Σαῦλος Ταρσεύς, Saũlos Tarseús; tr, Tarsuslu Pavlus; ...

to the Puget Sound

Puget Sound ( ) is a sound of the Pacific Northwest, an inlet of the Pacific Ocean, and part of the Salish Sea. It is located along the northwestern coast of the U.S. state of Washington. It is a complex estuarine system of interconnected ma ...

. In doing so, he demonstrated a tendency for insubordination toward senior political figures. Isaac Stevens

Isaac Ingalls Stevens (March 25, 1818 – September 1, 1862) was an American military officer and politician who served as governor of the Territory of Washington from 1853 to 1857, and later as its delegate to the United States House of Represe ...

, governor of the Washington Territory

The Territory of Washington was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1853, until November 11, 1889, when the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Washington. It was created from the ...

, became dissatisfied with McClellan's performance in his scouting of passes across the Cascade Range

The Cascade Range or Cascades is a major mountain range of western North America, extending from southern British Columbia through Washington and Oregon to Northern California. It includes both non-volcanic mountains, such as the North Cascades, ...

.

McClellan selected Yakima Pass () without a thorough reconnaissance and refused the governor's order to lead a party through it in winter conditions, relying on faulty intelligence about the depth of snowpack in that area. In so doing, he missed three greatly superior passes in the near vicinity, which were eventually used for railroads and interstate highways. The governor ordered McClellan to turn over his expedition logbooks, but McClellan steadfastly refused, most likely because of embarrassing personal comments that he had made throughout his adventures.

Returning to the East, McClellan began courting his future wife, Mary Ellen Marcy (1836–1915), the daughter of his former commander. Ellen, or Nelly, refused McClellan's first proposal of marriage, one of nine that she received from a variety of suitors, including his West Point friend, A. P. Hill. Ellen accepted Hill's proposal in 1856, but her family did not approve and he withdrew.

In June 1854, McClellan was sent on a secret reconnaissance mission to Santo Domingo at the behest of Jefferson Davis. McClellan assessed local defensive capabilities for the secretary. (The information was not used until 1870 when President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

unsuccessfully attempted to annex the Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic ( ; es, República Dominicana, ) is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean region. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares wit ...

.) Davis was beginning to treat McClellan almost as a protégé, and his next assignment was to assess the logistical readiness of various railroads in the United States, once again with an eye toward planning for the transcontinental railroad. In March 1855, McClellan was promoted to captain and assigned to the 1st U.S. Cavalry regiment.

Because of his political connections and his mastery of French, McClellan received the assignment to be an official observer of the European armies in the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the de ...

in 1855. Traveling widely, and interacting with the highest military commands and royal families, McClellan observed the siege of Sevastopol. Upon his return to the United States in 1856, he requested an assignment in Philadelphia to prepare his report, which contained a critical analysis of the siege and a lengthy description of the organization of the European armies. He also wrote a manual on cavalry tactics

For much of history, humans have used some form of cavalry for war and, as a result, cavalry tactics have evolved over time. Tactically, the main advantages of cavalry over infantry troops were greater mobility, a larger impact, and a higher pos ...

that was based on Russian cavalry regulations. Like other observers, though, McClellan did not appreciate the importance of the emergence of rifled muskets in the Crimean War, and the fundamental changes in warfare tactics it would require.

The Army adopted McClellan's cavalry manual and also his design for a saddle

The saddle is a supportive structure for a rider of an animal, fastened to an animal's back by a girth. The most common type is equestrian. However, specialized saddles have been created for oxen, camels and other animals. It is not kno ...

, dubbed the McClellan Saddle, which he claimed to have seen used by Hussar

A hussar ( , ; hu, huszár, pl, husarz, sh, husar / ) was a member of a class of light cavalry, originating in Central Europe during the 15th and 16th centuries. The title and distinctive dress of these horsemen were subsequently widely ...

s in Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

and Hungary. It became standard issue for as long as the U.S. horse cavalry existed and is still used for ceremonies.

Civilian pursuits

McClellan resigned his commission January 16, 1857, and, capitalizing on his experience with railroad assessment, became chief engineer and vice president of the

McClellan resigned his commission January 16, 1857, and, capitalizing on his experience with railroad assessment, became chief engineer and vice president of the Illinois Central Railroad

The Illinois Central Railroad , sometimes called the Main Line of Mid-America, was a railroad in the Central United States, with its primary routes connecting Chicago, Illinois, with New Orleans, Louisiana, and Mobile, Alabama. A line also co ...

, and then president of the Ohio and Mississippi Railroad

The Ohio and Mississippi Railway (earlier the Ohio and Mississippi Rail Road), abbreviated O&M, was a railroad operating between Cincinnati, Ohio, and East St. Louis, Illinois, from 1857 to 1893.

The railroad started in 1854 and paralleled the ...

in 1860. He performed well in both jobs, expanding the Illinois Central toward New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

and helping the Ohio and Mississippi recover from the Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Panic of 1857

The Panic of 1857 was a financial panic in the United States caused by the declining international economy and over-expansion of the domestic economy. Because of the invention of the telegraph by Samuel F. Morse in 1844, the Panic of 1857 was ...

. Despite his successes and lucrative salary ($10,000 per year), he was frustrated with civilian employment and continued to study classical military strategy assiduously. During the Utah War

The Utah War (1857–1858), also known as the Utah Expedition, Utah Campaign, Buchanan's Blunder, the Mormon War, or the Mormon Rebellion was an armed confrontation between Mormon settlers in the Utah Territory and the armed forces of the US go ...

against the Mormons

Mormons are a religious and cultural group related to Mormonism, the principal branch of the Latter Day Saint movement started by Joseph Smith in upstate New York during the 1820s. After Smith's death in 1844, the movement split into several ...

, he considered rejoining the Army. He also considered service as a filibuster

A filibuster is a political procedure in which one or more members of a legislative body prolong debate on proposed legislation so as to delay or entirely prevent decision. It is sometimes referred to as "talking a bill to death" or "talking out ...

in support of Benito Juárez

Benito Pablo Juárez García (; 21 March 1806 – 18 July 1872) was a Liberalism in Mexico, Mexican liberal politician and lawyer who served as the 26th president of Mexico from 1858 until his death in office in 1872. As a Zapotec peoples, Zapo ...

in Mexico.

Before the outbreak of the Civil War, McClellan became active in politics, supporting the presidential campaign of Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. A senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party for president in the 1860 presidential election, which wa ...

in the 1860 election. He claimed to have defeated an attempt at vote fraud by Republicans by ordering the delay of a train that was carrying men to vote illegally in another county, enabling Douglas to win the county.

In October 1859, McClellan was able to resume his courtship of Mary Ellen, and they were married in Calvary Church, New York City, on May 22, 1860.

Civil War

Ohio and strategy

At the start of theCivil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, McClellan's knowledge of what was called "big war science" and his railroad experience suggested he might excel at military logistics. This placed him in great demand as the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

mobilized. The governors of Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York, the three largest states of the Union, actively pursued him to command their states' militia. Ohio Governor William Dennison was the most persistent, so McClellan was commissioned a major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

of volunteers and took command of the Ohio militia on April 23, 1861. Unlike some of his fellow Union officers who came from abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

families, he was opposed to federal interference with slavery. For this reason, some of his Southern colleagues approached him informally about siding with the Confederacy, but he could not accept the concept of secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics le ...

.

On May 3 McClellan re-entered federal service as commander of the Department of the Ohio

The Department of the Ohio was an administrative military district created by the United States War Department early in the American Civil War to administer the troops in the Northern states near the Ohio River.

1st Department 1861–1862

Gener ...

, responsible for the defense of the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and, later, western Pennsylvania, western Virginia, and Missouri. On May 14, he was commissioned a major general in the regular army. At age 34, he outranked everyone in the Army except Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

, the general-in-chief. McClellan's rapid promotion was partly due to his acquaintance with Salmon P. Chase

Salmon Portland Chase (January 13, 1808May 7, 1873) was an American politician and jurist who served as the sixth chief justice of the United States. He also served as the 23rd governor of Ohio, represented Ohio in the United States Senate, a ...

, Treasury Secretary

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

and former Ohio governor and senator.

As McClellan scrambled to process the thousands of men who were volunteering for service and to set up training camps, he also applied his mind to grand strategy. He wrote a letter to Gen. Scott on April 27, four days after assuming command in Ohio, that presented the first proposal for a strategy for the war. It contained two alternatives, each envisioning a prominent role for himself as commander. The first would use 80,000 men to invade Virginia through the Kanawha Valley

The Kanawha River ( ) is a tributary of the Ohio River, approximately 97 mi (156 km) long, in the U.S. state of West Virginia. The largest inland waterway in West Virginia, its valley has been a significant industrial region of the sta ...

toward Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

. The second would use the same force to drive south instead, crossing the Ohio River into Kentucky and Tennessee. Scott rejected both plans as logistically unfeasible. Although he complimented McClellan and expressed his "great confidence in your intelligence, zeal, science, and energy", he replied by letter that the 80,000 men would be better used on a river-based expedition to control the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

and split the Confederacy, accompanied by a strong Union blockade

The Union blockade in the American Civil War was a naval strategy by the United States to prevent the Confederacy from trading.

The blockade was proclaimed by President Abraham Lincoln in April 1861, and required the monitoring of of Atlanti ...

of Southern ports. This plan, which would require considerable patience of the Northern public, was derided in newspapers as the Anaconda Plan

The Anaconda Plan is the name applied to a strategy outlined by the Union Army for suppressing the Confederacy at the beginning of the American Civil War. Proposed by Union General-in-Chief Winfield Scott, the plan emphasized a Union blockade ...

, but eventually proved to be the outline of the successful prosecution of the war. Relations between the two generals became increasingly strained over the summer and fall.

Western Virginia

McClellan's first military operations were to occupy the area of westernVirginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

that wanted to remain in the Union and subsequently became the state of West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the Bur ...

. He had received intelligence reports on May 26 that the critical Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the first common carrier railroad and the oldest railroad in the United States, with its first section opening in 1830. Merchants from Baltimore, which had benefited to some extent from the construction of ...

bridges in that portion of the state were being burned. As he quickly implemented plans to invade the region, he triggered his first serious political controversy by proclaiming to the citizens there that his forces had no intentions of interfering with personal property—including slaves. "Notwithstanding all that has been said by the traitors to induce you to believe that our advent among you will be signalized by interference with your slaves, understand one thing clearly—not only will we abstain from all such interference but we will on the contrary with an iron hand, crush any attempted insurrection on their part." He quickly realized that he had overstepped his bounds and apologized by letter to President Lincoln. The controversy was not that his proclamation was diametrically opposed to the administration's policy at the time, but that he was so bold in stepping beyond his strictly military role.

His forces moved rapidly into the area through Grafton and were victorious at the Battle of Philippi

The Battle of Philippi was the final battle in the Wars of the Second Triumvirate between the forces of Mark Antony and Octavian (of the Second Triumvirate) and the leaders of Julius Caesar's assassination, Brutus and Cassius in 42 BC, at P ...

, the first land conflict of the war. His first personal command in battle was at Rich Mountain, which he also won. His subordinate commander, William S. Rosecrans

William Starke Rosecrans (September 6, 1819March 11, 1898) was an American inventor, coal-oil company executive, diplomat, politician, and U.S. Army officer. He gained fame for his role as a Union general during the American Civil War. He was ...

, bitterly complained that his attack was not reinforced as McClellan had agreed. Nevertheless, these two minor victories propelled McClellan to the status of national hero. The ''New York Herald

The ''New York Herald'' was a large-distribution newspaper based in New York City that existed between 1835 and 1924. At that point it was acquired by its smaller rival the ''New-York Tribune'' to form the '' New York Herald Tribune''.

His ...

'' entitled an article about him "Gen. McClellan, the Napoleon of the Present War".

Building an army

After the defeat of the Union forces at Bull Run on July 21, 1861, Lincoln summoned McClellan from western Virginia, where McClellan had given the North the only engagements bearing a semblance of victory. He traveled by special train on the main Pennsylvania line from Wheeling throughPittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

, Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, and Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

, and on to Washington City, and was greeted by enthusiastic crowds that met his train along the way.

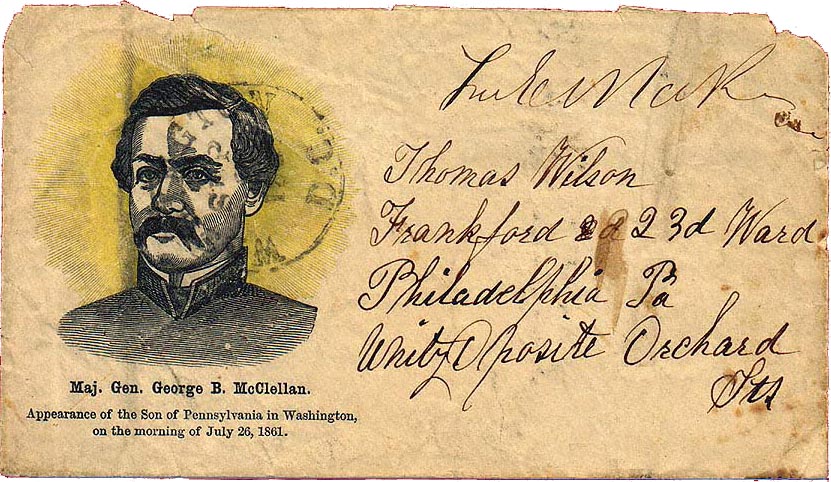

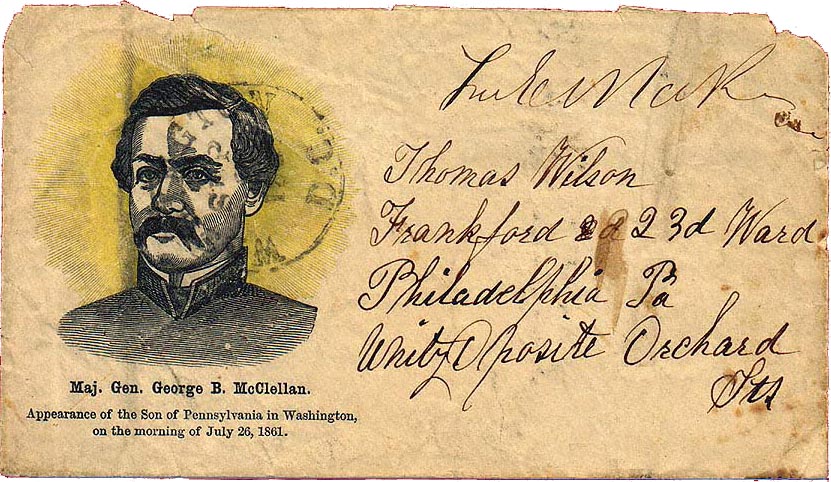

Carl Sandburg

Carl August Sandburg (January 6, 1878 – July 22, 1967) was an American poet, biographer, journalist, and editor. He won three Pulitzer Prizes: two for his poetry and one for his biography of Abraham Lincoln. During his lifetime, Sandburg ...

wrote, "McClellan was the man of the hour, pointed to by events, and chosen by an overwhelming weight of public and private opinion." On July 26, the day he reached the capital, McClellan was appointed commander of the Military Division of the Potomac, the main Union force responsible for the defense of Washington. On August 20, several military units in Virginia were consolidated into his department and he immediately formed the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confedera ...

, with himself as its first commander. He reveled in his newly acquired power and influence:

During the summer and fall, McClellan brought a high degree of organization to his new army, and greatly improved its morale with frequent trips to review and encourage his units. It was a remarkable achievement, in which he came to personify the Army of the Potomac and reaped the adulation of his men. He created defenses for Washington that were almost impregnable, consisting of 48 forts and strong points, with 480 guns manned by 7,200 artillerists. The Army of the Potomac grew in number from 50,000 in July to 168,000 in November, becoming the largest military force the United States had raised until that time. But this was also a time of tension in the high command, as he continued to quarrel frequently with the government and the general-in-chief, Lt. Gen. Scott, on matters of strategy. McClellan rejected the tenets of Scott's

During the summer and fall, McClellan brought a high degree of organization to his new army, and greatly improved its morale with frequent trips to review and encourage his units. It was a remarkable achievement, in which he came to personify the Army of the Potomac and reaped the adulation of his men. He created defenses for Washington that were almost impregnable, consisting of 48 forts and strong points, with 480 guns manned by 7,200 artillerists. The Army of the Potomac grew in number from 50,000 in July to 168,000 in November, becoming the largest military force the United States had raised until that time. But this was also a time of tension in the high command, as he continued to quarrel frequently with the government and the general-in-chief, Lt. Gen. Scott, on matters of strategy. McClellan rejected the tenets of Scott's Anaconda Plan

The Anaconda Plan is the name applied to a strategy outlined by the Union Army for suppressing the Confederacy at the beginning of the American Civil War. Proposed by Union General-in-Chief Winfield Scott, the plan emphasized a Union blockade ...

, favoring instead an overwhelming grand battle, in the Napoleonic

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

style. He proposed that his army should be expanded to 273,000 men and 600 guns and "crush the rebels in one campaign". He favored a war that would impose little impact on civilian populations and require no emancipation of slaves.

McClellan's antipathy to emancipation added to the pressure on him, as he received bitter criticism from Radical Republicans

The Radical Republicans (later also known as " Stalwarts") were a faction within the Republican Party, originating from the party's founding in 1854, some 6 years before the Civil War, until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Reco ...

in the government. He viewed slavery as an institution recognized in the Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

, and entitled to federal protection wherever it existed (Lincoln held the same public position until August 1862). McClellan's writings after the war were typical of many Northerners: "I confess to a prejudice in favor of my own race, & can't learn to like the odor of either Billy goats or niggers." But in November 1861, he wrote to his wife, "I will, if successful, throw my sword onto the scale to force an improvement in the condition of those poor blacks." He later wrote that had it been his place to arrange the terms of peace, he would have insisted on gradual emancipation, guarding the rights of both slaves and masters, as part of any settlement. But he made no secret of his opposition to the Radical Republicans. He told Ellen, "I will not fight for the abolitionists." This put him in opposition with officials of the administration who believed he was attempting to implement the policies of the opposition party.

The immediate problem with McClellan's war strategy was that he was convinced the Confederates were ready to attack him with overwhelming numbers. On August 8, believing that the Confederacy had over 100,000 troops facing him (in contrast to the 35,000 they had actually deployed at Bull Run a few weeks earlier), he declared a state of emergency in the capital. By August 19, he estimated 150,000 rebel soldiers on his front. In this, McClellan was perhaps influenced by his questioning of Confederate deserter Edward B. McMurdy, whose testimony was not accepted by Lincoln, Secretary of State Seward, or General-in-Chief Scott, but reaffirmed for McClellan the numbers he had convinced himself of. McClellan's feeling of facing overwhelming odds in subsequent campaigns throughout his tenure as General of the Army of the Potomac were strongly influenced by the overblown enemy strength estimates of his secret service chief, detective Allan Pinkerton

Allan J. Pinkerton (August 25, 1819 – July 1, 1884) was a Scottish cooper, abolitionist, detective, and spy, best known for creating the Pinkerton National Detective Agency in the United States and his claim to have foiled a plot in 1861 to a ...

, but in August 1861, these estimates were entirely McClellan's own. The result was a level of extreme caution that sapped the initiative of McClellan's army and dismayed the government. Historian and biographer Stephen W. Sears observed that McClellan's actions would have been "essentially sound" for a commander who was as outnumbered as McClellan thought he was, but McClellan in fact rarely had less than a two-to-one advantage over the armies that opposed him in 1861 and 1862. That fall, for example, Confederate forces ranged from 35,000 to 60,000, whereas the Army of the Potomac in September numbered 122,000 men; in early December 170,000; by year end, 192,000.

The dispute with Scott became increasingly personal. Scott (as well as many in the War Department) was outraged that McClellan refused to divulge any details about his strategic planning, or even such basic information as the strengths and dispositions of his units. McClellan claimed he could not trust anyone in the administration to keep his plans secret from the press, and thus the enemy. In the course of a disagreement about defensive forces on the Potomac River, McClellan wrote to his wife on August 10: "Genl Scott is the great obstacle—he will not comprehend the danger & is either a traitor, or an incompetent. I have to fight my way against him." Scott became so disillusioned with the young general that he offered his resignation to President Lincoln, who initially refused to accept it. Rumors traveled through the capital that McClellan might resign, or instigate a military coup, if Scott were not removed. Lincoln's Cabinet met on October 18 and agreed to accept Scott's resignation for “reasons of health”.

However, the subsequently formed Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confedera ...

had high morale and was extremely proud of their general, some even referring to McClellan as the savior of Washington. He prevented the army's morale from collapsing at least twice, in the aftermath of the First

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

and Second

The second (symbol: s) is the unit of time in the International System of Units (SI), historically defined as of a day – this factor derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes and finally to 60 seconds ...

Battles of Bull Run. Many historians argue that he was talented in this aspect.

General-in-chief

On November 1, 1861,

On November 1, 1861, Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

retired and McClellan became general-in-chief of all the Union armies. The president expressed his concern about the "vast labor" involved in the dual role of army commander and general-in-chief, but McClellan responded, "I can do it all."

Lincoln, as well as many other leaders and citizens of the northern states, became increasingly impatient with McClellan's slowness to attack the Confederate forces still massed near Washington. The Union defeat at the minor Battle of Ball's Bluff

The Battle of Ball's Bluff was an early battle of the American Civil War fought in Loudoun County, Virginia, on October 21, 1861, in which Union Army forces under Major General George B. McClellan suffered a humiliating defeat.

The operation was ...

near Leesburg in October added to the frustration and indirectly damaged McClellan. In December, the Congress formed a Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War

The Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War was a United States congressional committee started on December 9, 1861, and was dismissed in May 1865. The committee investigated the progress of the war against the Confederacy. Meetings were held ...

, which became a thorn in the side of many generals throughout the war, accusing them of incompetence and, in some cases, treason. McClellan was called as the first witness on December 23, but he contracted typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several ...

and could not attend. Instead, his subordinate officers testified, and their candid admissions that they had no knowledge of specific strategies for advancing against the Confederates raised many calls for McClellan's dismissal.

McClellan further damaged his reputation by his insulting insubordination to his commander-in-chief. He privately referred to Lincoln, whom he had known before the war as a lawyer for the Illinois Central, as "nothing more than a well-meaning baboon", a "gorilla", and "ever unworthy of ... his high position". On November 13, he snubbed the president, who had come to visit McClellan's house, by making him wait for 30 minutes, only to be told that the general had gone to bed and could not receive him.

On January 10, 1862, Lincoln met with top generals (McClellan did not attend) and directed them to formulate a plan of attack, expressing his exasperation with General McClellan with the following remark: "If General McClellan does not want to use the army, I would like to borrow it for a time." On January 12, 1862, McClellan was summoned to the White House, where the Cabinet demanded to hear his war plans. For the first time, he revealed his intentions to transport the Army of the Potomac by ship to Urbanna

Urbanna is a town in Middlesex County, Virginia, United States. Urbanna means “City of Anne” and was named in honor of England's Queen Anne. The population was 476 at the 2010 census.

Geography

Urbanna is located at (37.637796, −76 ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, on the Rappahannock River

The Rappahannock River is a river in eastern Virginia, in the United States, approximately in length.U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed April 1, 2011 It traverses the entir ...

, outflanking the Confederate forces near Washington, and proceeding overland to capture Richmond. He refused to give any specific details of the proposed campaign, even to his friend, newly appointed War Secretary

The Secretary of State for War, commonly called War Secretary, was a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, which existed from 1794 to 1801 and from 1854 to 1964. The Secretary of State for War headed the War Office and ...

Edwin M. Stanton

Edwin McMasters Stanton (December 19, 1814December 24, 1869) was an American lawyer and politician who served as U.S. Secretary of War under the Lincoln Administration during most of the American Civil War. Stanton's management helped organize ...

. On January 27, Lincoln issued an order that required all of his armies to begin offensive operations by February 22, Washington's birthday

Presidents' Day, also called Washington's Birthday at the federal governmental level, is a holiday in the United States celebrated on the third Monday of February to honor all persons who served as presidents of the United States and, since 1879 ...

. On January 31, he issued a supplementary order for the Army of the Potomac to move overland to attack the Confederates at Manassas Junction

Manassas (), formerly Manassas Junction, is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia, United States. The population was 42,772 at the 2020 Census. It is the county seat of Prince William County, although the two are separate jurisdi ...

and Centreville. McClellan immediately replied with a 22-page letter objecting in detail to the president's plan and advocating instead his Urbanna plan, which was the first written instance of the plan's details being presented to the president. Although Lincoln believed his plan was superior, he was relieved that McClellan finally agreed to begin moving, and reluctantly approved. On March 8, doubting McClellan's resolve, Lincoln again interfered with the army commander's prerogatives. He called a council of war

A council of war is a term in military science that describes a meeting held to decide on a course of action, usually in the midst of a battle. Under normal circumstances, decisions are made by a commanding officer, optionally communicated ...

at the White House in which McClellan's subordinates were asked about their confidence in the Urbanna plan. They expressed their confidence to varying degrees. After the meeting, Lincoln issued another order, naming specific officers as corps commanders to report to McClellan (who had been reluctant to do so prior to assessing his division commanders' effectiveness in combat, even though this would have meant his direct supervision of twelve divisions in the field).

Two more crises would confront McClellan before he could implement his plans. The Confederate forces under General Joseph E. Johnston

Joseph Eggleston Johnston (February 3, 1807 – March 21, 1891) was an American career army officer, serving with distinction in the United States Army during the Mexican–American War (1846–1848) and the Seminole Wars. After Virginia secede ...

withdrew from their positions before Washington, assuming new positions south of the Rappahannock, which completely nullified the Urbanna strategy. McClellan revised his plans to have his troops disembark at Fort Monroe

Fort Monroe, managed by partnership between the Fort Monroe Authority for the Commonwealth of Virginia, the National Park Service as the Fort Monroe National Monument, and the City of Hampton, is a former military installation in Hampton, Virgi ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, and advance up the Virginia Peninsula

The Virginia Peninsula is a peninsula in southeast Virginia, USA, bounded by the York River, James River, Hampton Roads and Chesapeake Bay. It is sometimes known as the ''Lower Peninsula'' to distinguish it from two other peninsulas to the ...

to Richmond, an operation that would be known as the Peninsula Campaign. Then, however, McClellan came under extreme criticism in the press and Congress when it was learned that Johnston's forces had not only slipped away unnoticed, but had for months fooled the Union Army with logs painted black to appear as cannons, nicknamed Quaker Guns. Congress's joint committee visited the abandoned Confederate lines and radical Republicans introduced a resolution demanding the dismissal of McClellan, but it was narrowly defeated by a parliamentary maneuver. The second crisis was the emergence of the Confederate ironclad CSS ''Virginia'', which threw Washington into a panic and made naval support operations on the James River seem problematic.