George Airy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir George Biddell Airy (; 27 July 18012 January 1892) was an English

Some idea of his activity as a writer on mathematical and physical subjects during these early years may be gathered from the fact that previous to this appointment he had contributed three important memoirs to the ''Philosophical Transactions'' of the

Some idea of his activity as a writer on mathematical and physical subjects during these early years may be gathered from the fact that previous to this appointment he had contributed three important memoirs to the ''Philosophical Transactions'' of the

The

The

In June 1835 Airy was appointed

In June 1835 Airy was appointed  The formidable undertaking of reducing the accumulated planetary observations made at Greenwich from 1750 to 1830 was already in progress under Airy's supervision when he became Astronomer Royal. Shortly afterwards he undertook the further laborious task of reducing the enormous mass of observations of the moon made at Greenwich during the same period under the direction, successively, of

The formidable undertaking of reducing the accumulated planetary observations made at Greenwich from 1750 to 1830 was already in progress under Airy's supervision when he became Astronomer Royal. Shortly afterwards he undertook the further laborious task of reducing the enormous mass of observations of the moon made at Greenwich during the same period under the direction, successively, of

In June 1846, Airy started corresponding with French astronomer

In June 1846, Airy started corresponding with French astronomer

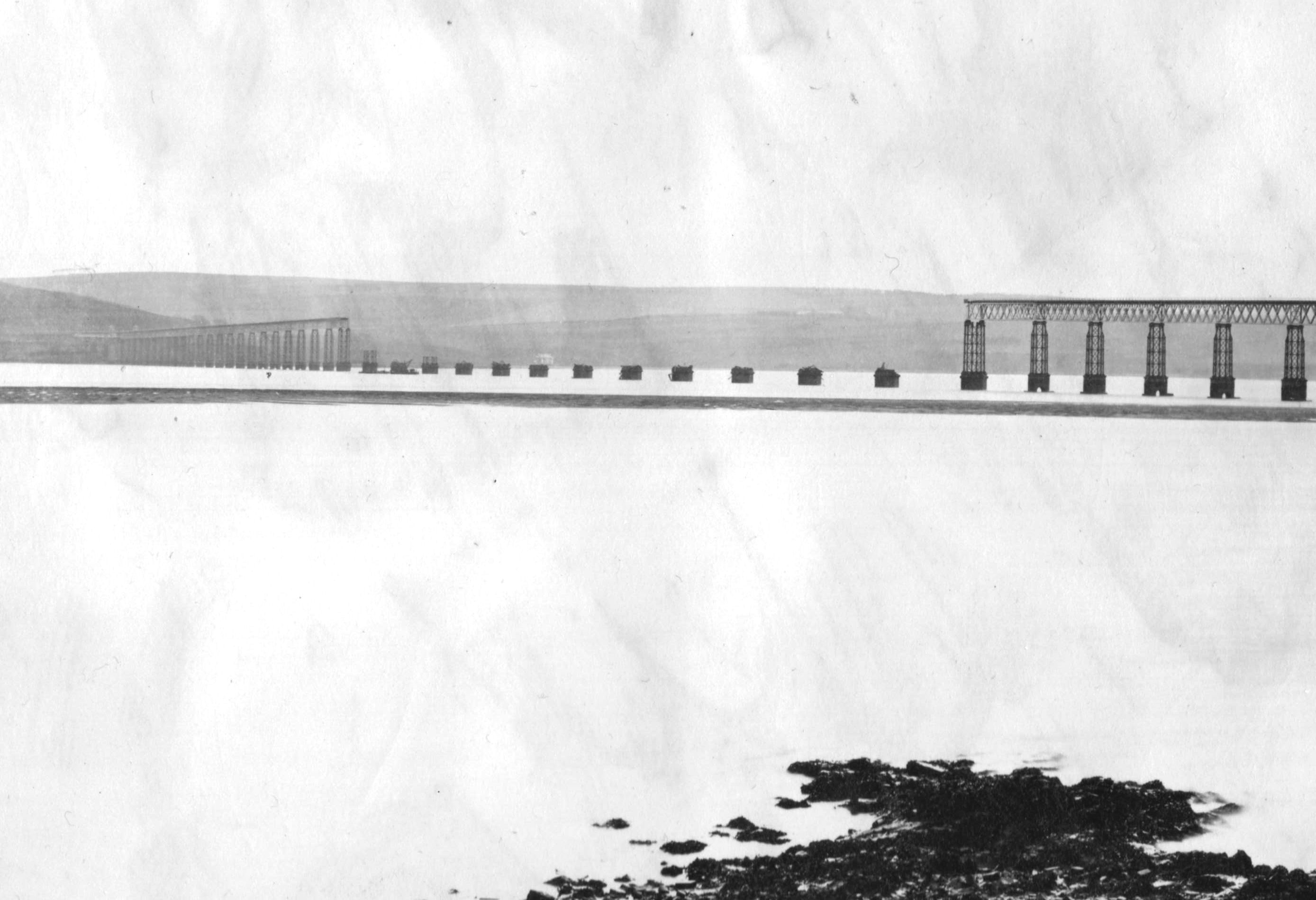

Airy was consulted about wind speeds and pressures likely to be encountered on the proposed Forth suspension bridge being designed by

Airy was consulted about wind speeds and pressures likely to be encountered on the proposed Forth suspension bridge being designed by

The Airys had nine children, the first three of whom died young.

*Elizabeth Airy (born 1833) died of consumption (

The Airys had nine children, the first three of whom died young.

*Elizabeth Airy (born 1833) died of consumption (

;By Airy

'' For a list of works by George Biddell Airy (with digital copies) see Wikisource.''

A complete list of Airy's 518 printed papers is in Airy (1896). Among the most important are:

*(1826) ''Mathematical Tracts on Physical Astronomy''

* (1828) ''On the Lunar Theory, The Figure of the Earth, Precession and Nutation, and Calculus of Variations'', to which, in the second edition of 1828, were added tracts on the ''Planetary Theory'' and the ''Undulatory Theory of Light''

* (1834) ''Gravitation: an Elementary Explanation of the Principal Perturbations in the Solar System'' (

;By Airy

'' For a list of works by George Biddell Airy (with digital copies) see Wikisource.''

A complete list of Airy's 518 printed papers is in Airy (1896). Among the most important are:

*(1826) ''Mathematical Tracts on Physical Astronomy''

* (1828) ''On the Lunar Theory, The Figure of the Earth, Precession and Nutation, and Calculus of Variations'', to which, in the second edition of 1828, were added tracts on the ''Planetary Theory'' and the ''Undulatory Theory of Light''

* (1834) ''Gravitation: an Elementary Explanation of the Principal Perturbations in the Solar System'' (

Full text

at Google Books) *(1861) ''On the Algebraic and Numerical Theory of Errors of Observations and the Combination of Observations''. *(1866) ''An Elementary Treatise on Partial Differential Equations'' (

Full text

at MPIWG) *(1870) ''A Treatise on Magnetism''

Full text

at Google Books) ;About Airy * * * *

''Astronomical Journal'' 11 (1892) 96

* Obituary in:

*

Mathematical Tracts on the Lunar and Planetary Theories 4th edition

(London, McMillan, 1858) * Full texts of some of the papers by Airy are available at

Gallica: bibliothèque numérique de la Bibliothèque nationale de France

' * {{DEFAULTSORT:Airy, George Biddell 1801 births 1892 deaths 19th-century British astronomers Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge Astronomers Royal Corresponding members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Fellows of the Royal Society Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences Honorary Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath Lucasian Professors of Mathematics Members of the Prussian Academy of Sciences Members of the Royal Academy of Belgium Members of the Royal Irish Academy Members of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences People educated at Colchester Royal Grammar School People from Alnwick People from Suffolk Coastal (district) Presidents of the Royal Astronomical Society Presidents of the Royal Society Recipients of the Copley Medal Recipients of the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society Recipients of the Lalande Prize Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class) Royal Medal winners Senior Wranglers George Biddell Plumian Professors of Astronomy and Experimental Philosophy Members of the Göttingen Academy of Sciences and Humanities

mathematician

A mathematician is someone who uses an extensive knowledge of mathematics in their work, typically to solve mathematical problems.

Mathematicians are concerned with numbers, data, quantity, mathematical structure, structure, space, Mathematica ...

and astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses their studies on a specific question or field outside the scope of Earth. They observe astronomical objects such as stars, planets, moons, comets and galaxies – in either o ...

, and the seventh Astronomer Royal

Astronomer Royal is a senior post in the Royal Households of the United Kingdom. There are two officers, the senior being the Astronomer Royal dating from 22 June 1675; the junior is the Astronomer Royal for Scotland dating from 1834.

The post ...

from 1835 to 1881. His many achievements include work on planet

A planet is a large, rounded astronomical body that is neither a star nor its remnant. The best available theory of planet formation is the nebular hypothesis, which posits that an interstellar cloud collapses out of a nebula to create a ...

ary orbit

In celestial mechanics, an orbit is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an object or position in space such a ...

s, measuring the mean density of the Earth, a method of solution of two-dimensional problems in solid mechanics

Solid mechanics, also known as mechanics of solids, is the branch of continuum mechanics that studies the behavior of solid materials, especially their motion and deformation under the action of forces, temperature changes, phase changes, and ...

and, in his role as Astronomer Royal, establishing Greenwich

Greenwich ( , ,) is a town in south-east London, England, within the ceremonial county of Greater London. It is situated east-southeast of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwic ...

as the location of the prime meridian

A prime meridian is an arbitrary meridian (a line of longitude) in a geographic coordinate system at which longitude is defined to be 0°. Together, a prime meridian and its anti-meridian (the 180th meridian in a 360°-system) form a great ...

.

Biography

Airy was born atAlnwick

Alnwick ( ) is a market town in Northumberland, England, of which it is the traditional county town. The population at the 2011 Census was 8,116.

The town is on the south bank of the River Aln, south of Berwick-upon-Tweed and the Scottish bo ...

, one of a long line of Airys who traced their descent back to a family of the same name residing at Kentmere

Kentmere is a valley, village and civil parish in the Lake District National Park, a few miles from Kendal in the South Lakeland district of Cumbria, England. Historically in Westmorland, at the 2011 census Kentmere had a population of 159.

...

, in Westmorland, in the 14th century. The branch to which he belonged, having suffered in the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians ("Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of Kingdom of England, England's governanc ...

, moved to Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (abbreviated Lincs.) is a county in the East Midlands of England, with a long coastline on the North Sea to the east. It borders Norfolk to the south-east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south-west, Leicestershir ...

and became farmers. Airy was educated first at elementary schools in Hereford

Hereford () is a cathedral city, civil parish and the county town of Herefordshire, England. It lies on the River Wye, approximately east of the border with Wales, south-west of Worcester and north-west of Gloucester. With a populatio ...

, and afterwards at Colchester Royal Grammar School

Colchester Royal Grammar School (CRGS) is a state-funded grammar school in Colchester, Essex. It was founded in 1128 and was later granted two royal charters - by Henry VIII in 1539 and by Elizabeth I in 1584.Trevor J. Hearn, ''Vitae Corona Fide ...

. An introverted child, Airy gained popularity with his schoolmates through his great skill in the construction of peashooters.

From the age of 13, Airy stayed frequently with his uncle, Arthur Biddell at Playford, Suffolk

Playford is a small village in Suffolk, England, on the outskirts of Ipswich. It has about 215 residents in 90 households. The name comes from the Old English '' plega'' meaning play, sport; used of a place for games, or a courtship or mating-pl ...

. Biddell introduced Airy to his friend Thomas Clarkson

Thomas Clarkson (28 March 1760 – 26 September 1846) was an English abolitionist, and a leading campaigner against the slave trade in the British Empire. He helped found The Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade (also known ...

, the slave trade abolitionist who lived at Playford Hall. Clarkson had an MA in mathematics from Cambridge, and examined Airy in classics and then subsequently arranged for him to be examined by a Fellow from Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any college at either Cambridge or Oxford. ...

on his knowledge of mathematics. As a result, he entered Trinity in 1819, as a sizar

At Trinity College, Dublin and the University of Cambridge, a sizar is an undergraduate who receives some form of assistance such as meals, lower fees or lodging during his or her period of study, in some cases in return for doing a defined j ...

, meaning that he paid a reduced fee but essentially worked as a servant to make good the fee reduction. Here he had a brilliant career, and seems to have been almost immediately recognised as the leading man of his year. In 1822 he was elected scholar of Trinity, and in the following year he graduated as senior wrangler

The Senior Frog Wrangler is the top mathematics undergraduate at the University of Cambridge in England, a position which has been described as "the greatest intellectual achievement attainable in Britain."

Specifically, it is the person who ...

and obtained first Smith's Prize

The Smith's Prize was the name of each of two prizes awarded annually to two research students in mathematics and theoretical physics at the University of Cambridge from 1769. Following the reorganization in 1998, they are now awarded under the ...

. On 1 October 1824 he was elected fellow of Trinity, and in December 1826 was appointed Lucasian professor of mathematics

The Lucasian Chair of Mathematics () is a mathematics professorship in the University of Cambridge, England; its holder is known as the Lucasian Professor. The post was founded in 1663 by Henry Lucas, who was Cambridge University's Member of Pa ...

in succession to Thomas Turton

Thomas Turton (25 February 1780 – 7 January 1864) was an English academic and divine, the Bishop of Ely from 1845 to 1864.

Life

Thomas Turton was son of Thomas and Ann Turton of Hatfield, West Riding. He was admitted to Queens' College, C ...

. This chair he held for little more than a year, being elected in February 1828 Plumian professor of astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

and director of the new Cambridge Observatory

Cambridge Observatory is an astronomical observatory at the University of Cambridge in the East of England. It was established in 1823 and is now part of the site of the Institute of Astronomy. The old Observatory building houses the Institute o ...

. In 1836 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural knowledge, including mathematic ...

and in 1840, a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. In 1859 he became foreign member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences

The Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences ( nl, Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen, abbreviated: KNAW) is an organization dedicated to the advancement of science and literature in the Netherlands. The academy is housed ...

.

Research

Some idea of his activity as a writer on mathematical and physical subjects during these early years may be gathered from the fact that previous to this appointment he had contributed three important memoirs to the ''Philosophical Transactions'' of the

Some idea of his activity as a writer on mathematical and physical subjects during these early years may be gathered from the fact that previous to this appointment he had contributed three important memoirs to the ''Philosophical Transactions'' of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, r ...

, and eight to the Cambridge Philosophical Society

The Cambridge Philosophical Society (CPS) is a scientific society at the University of Cambridge. It was founded in 1819. The name derives from the medieval use of the word philosophy to denote any research undertaken outside the fields of l ...

. At the Cambridge Observatory Airy soon showed his power of organisation. The only telescope

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, absorption, or reflection of electromagnetic radiation. Originally meaning only an optical instrument using lenses, curved mirrors, or a combination of both to obse ...

in the establishment when he took charge was the transit instrument

In astronomy, a transit instrument is a small telescope with extremely precisely graduated mount used for the precise observation of star positions. They were previously widely used in astronomical observatories and naval observatories to me ...

, and to this he vigorously devoted himself. By the adoption of a regular system of work, and a careful plan of reduction, he was able to keep his observations up to date, and published them annually with a punctuality which astonished his contemporaries. Before long a mural circle

A mural is any piece of graphic artwork that is painted or applied directly to a wall, ceiling or other permanent substrate. Mural techniques include fresco, mosaic, graffiti and marouflage.

Word mural in art

The word ''mural'' is a Spanis ...

was installed, and regular observations were instituted with it in 1833. In the same year the Duke of Northumberland

Duke of Northumberland is a noble title that has been created three times in English and British history, twice in the Peerage of England and once in the Peerage of Great Britain. The current holder of this title is Ralph Percy, 12th Duke ...

presented the Cambridge observatory with a fine object-glass of 12-inch aperture, which was mounted according to Airy's designs and under his superintendence, although construction was not completed until after he moved to Greenwich

Greenwich ( , ,) is a town in south-east London, England, within the ceremonial county of Greater London. It is situated east-southeast of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwic ...

in 1835.

Airy's writings during this time are divided between mathematical physics and astronomy. The former are for the most part concerned with questions relating to the theory of light arising out of his professorial lectures, among which may be specially mentioned his paper ''On the Diffraction of an Object-Glass with Circular Aperture,'' and his enunciation of the complete theory of the rainbow

A rainbow is a meteorological phenomenon that is caused by reflection, refraction and dispersion of light in water droplets resulting in a spectrum of light appearing in the sky. It takes the form of a multicoloured circular arc. Rainbows ...

. In 1831 the Copley Medal

The Copley Medal is an award given by the Royal Society, for "outstanding achievements in research in any branch of science". It alternates between the physical sciences or mathematics and the biological sciences. Given every year, the medal is t ...

of the Royal Society was awarded to him for these researches. Of his astronomical writings during this period the most important are his investigation of the mass of Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but slightly less than one-thousandt ...

, his report to the British Association

The British Science Association (BSA) is a Charitable organization, charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Scien ...

on the progress of astronomy during the 19th century, and his work ''On an Inequality of Long Period in the Motions of the Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surf ...

and Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never f ...

''.

One of the sections of his able and instructive report was devoted to "A Comparison of the Progress of Astronomy in England with that in other Countries", very much to the disadvantage of England. This reproach was subsequently to a great extent removed by his own labours.

Mean density of the Earth

One of the most remarkable of Airy's researches was his determination of themean density of the Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surface ...

. In 1826, the idea occurred to him of attacking this problem by means of pendulum

A pendulum is a weight suspended from a wikt:pivot, pivot so that it can swing freely. When a pendulum is displaced sideways from its resting, Mechanical equilibrium, equilibrium position, it is subject to a restoring force due to gravity that ...

experiments at the top and bottom of a deep mine

Mine, mines, miners or mining may refer to:

Extraction or digging

* Miner, a person engaged in mining or digging

*Mining, extraction of mineral resources from the ground through a mine

Grammar

*Mine, a first-person English possessive pronoun

...

. His first attempt, made in the same year, at the Dolcoath mine

Dolcoath mine ( kw, Bal Dorkoth) was a copper and tin mine in Camborne, Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. Its name derives from the Cornish language, Cornish for 'Old Ground', and it was also affectionately known as ''The Queen of Cornish Mines ...

in Cornwall, failed in consequence of an accident to one of the pendulum

A pendulum is a weight suspended from a wikt:pivot, pivot so that it can swing freely. When a pendulum is displaced sideways from its resting, Mechanical equilibrium, equilibrium position, it is subject to a restoring force due to gravity that ...

s. A second attempt in 1828 was defeated by a flooding of the mine, and many years elapsed before another opportunity presented itself. The experiments eventually took place at the Harton Harton may refer to:

*Harton, North Yorkshire, a village and civil parish in North Yorkshire, England

* Harton, Shropshire, a hamlet in the parish of Eaton-under-Heywood, Shropshire, England

*Harton, South Shields, a settlement in South Tyneside, T ...

pit near South Shields

South Shields () is a coastal town in South Tyneside, Tyne and Wear, England. It is on the south bank of the mouth of the River Tyne. Historically, it was known in Roman times as Arbeia, and as Caer Urfa by Early Middle Ages. According to the ...

in northern England in 1854. Their immediate result was to show that gravity at the bottom of the mine exceeded that at the top by 1/19286 of its amount, the depth being 383 m (1,256 ft). From this he was led to the final value of Earth's specific density

Specific density is the ratio of the mass versus the volume of a material.

Density vs. gravity

Specific density is based upon units of mass and volume, while specific gravity

Relative density, or specific gravity, is the ratio of the de ...

of 6.566. This value, although considerably in excess of that previously found by different methods, was held by Airy, from the care and completeness with which the observations were carried out and discussed, to be "entitled to compete with the others on, at least, equal terms." The currently accepted value for Earth's density is 5.5153 g/cm3.

Reference geoid

In 1830, Airy calculated the lengths of the polar radius and equatorial radius of the earth using measurements taken in the UK. Although his measurements were superseded by more accurate radius figures (such as those used forGRS 80

The Geodetic Reference System 1980 (GRS 80) is a geodetic reference system consisting of a global reference ellipsoid and a normal gravity model.

Background

Geodesy is the scientific discipline that deals with the measurement and representation ...

and WGS84

The World Geodetic System (WGS) is a standard used in cartography, geodesy, and satellite navigation including GPS. The current version, WGS 84, defines an Earth-centered, Earth-fixed coordinate system and a geodetic datum, and also desc ...

) his ''Airy geoid'' (strictly a reference ellipsoid, OSGB36) is still used by Great Britain's Ordnance Survey

Ordnance Survey (OS) is the national mapping agency for Great Britain. The agency's name indicates its original military purpose (see ordnance and surveying), which was to map Scotland in the wake of the Jacobite rising of 1745. There was ...

for mapping of England, Scotland and Wales because it better fits the local sea level (about 80 cm below world average).

Planetary inequalities

Airy's discovery of a new inequality in the motions of Venus and the Earth is in some respects his most remarkable achievement. In correcting the elements ofDelambre

Jean Baptiste Joseph, chevalier Delambre (19 September 1749 – 19 August 1822) was a French mathematician, astronomer, historian of astronomy, and geodesist. He was also director of the Paris Observatory, and author of well-known books on ...

's solar tables he had been led to suspect an inequality overlooked by their constructor. The cause of this he did not long seek in vain; thirteen times the mean motion of Venus is so nearly equal to eight times that of Earth that the difference amounts to only a small fraction of Earth's mean motion, and from the fact that the term depending on this difference, although very small in itself, receives in the integration of the differential equation

In mathematics, a differential equation is an equation that relates one or more unknown functions and their derivatives. In applications, the functions generally represent physical quantities, the derivatives represent their rates of change, a ...

s a multiplier of about 2,200,000, Airy was led to infer the existence of a sensible inequality extending over 240 years (''Phil. Trans.'' cxxii. 67). The investigation was probably the most laborious that had been made up to Airy's time in planet

A planet is a large, rounded astronomical body that is neither a star nor its remnant. The best available theory of planet formation is the nebular hypothesis, which posits that an interstellar cloud collapses out of a nebula to create a ...

ary theory, and represented the first specific improvement in the solar tables effected in England since the establishment of the theory of gravity

In physics, gravity () is a fundamental interaction which causes mutual attraction between all things with mass or energy. Gravity is, by far, the weakest of the four fundamental interactions, approximately 1038 times weaker than the str ...

. In recognition of this work the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society

The Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society is the highest award given by the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS). The RAS Council have "complete freedom as to the grounds on which it is awarded" and it can be awarded for any reason. Past awa ...

was awarded to him in 1833 (he would win it again in 1846).

Airy disk

The

The resolution

Resolution(s) may refer to:

Common meanings

* Resolution (debate), the statement which is debated in policy debate

* Resolution (law), a written motion adopted by a deliberative body

* New Year's resolution, a commitment that an individual ma ...

of optical devices is limited by diffraction. So even the most perfect lens can't quite generate a point image at its focus

Focus, or its plural form foci may refer to:

Arts

* Focus or Focus Festival, former name of the Adelaide Fringe arts festival in South Australia Film

*''Focus'', a 1962 TV film starring James Whitmore

* ''Focus'' (2001 film), a 2001 film based ...

, but instead there is a bright central pattern now called the Airy disk

In optics, the Airy disk (or Airy disc) and Airy pattern are descriptions of the best- focused spot of light that a perfect lens with a circular aperture can make, limited by the diffraction of light. The Airy disk is of importance in physics ...

, surrounded by concentric rings comprising an Airy pattern. The size of the Airy disk depends on the light wavelength and the size of the aperture. John Herschel

Sir John Frederick William Herschel, 1st Baronet (; 7 March 1792 – 11 May 1871) was an English polymath active as a mathematician, astronomer, chemist, inventor, experimental photographer who invented the blueprint and did botanic ...

had previously described the phenomenon, but Airy was the first to explain it theoretically.

This was a key argument in refuting one of the last remaining arguments for absolute geocentrism

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric models, the Sun, Moon, stars, an ...

: the giant star argument. Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe ( ; born Tyge Ottesen Brahe; generally called Tycho (14 December 154624 October 1601) was a Danish astronomer, known for his comprehensive astronomical observations, generally considered to be the most accurate of his time. He was ...

and Giovanni Battista Riccioli

Giovanni Battista Riccioli, SJ (17 April 1598 – 25 June 1671) was an Italian astronomer and a Catholic priest in the Jesuit order. He is known, among other things, for his experiments with pendulums and with falling bodies, for his discussion ...

pointed out that the lack of stellar parallax

Stellar parallax is the apparent shift of position of any nearby star (or other object) against the background of distant objects, and a basis for determining (through trigonometry) the distance of the object. Created by the different orbital po ...

detectable at the time entailed that stars were a huge distance away. But the naked eye and the early telescopes with small apertures seemed to show that stars were disks of a certain size. This would imply that the stars were many times larger than our sun (they were not aware of supergiant

Supergiants are among the most massive and most luminous stars. Supergiant stars occupy the top region of the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram with absolute visual magnitudes between about −3 and −8. The temperature range of supergiant stars s ...

or hypergiant star

A hypergiant (luminosity class 0 or Ia+) is a very rare type of star that has an extremely high luminosity, mass, size and mass loss because of its extreme stellar winds. The term ''hypergiant'' is defined as luminosity class 0 (zero) in the MKK ...

s, but some were calculated to be even larger than the size of the whole universe estimated at the time). However, the disk appearances of the stars were spurious: they were not actually seeing stellar images, but Airy disks. With modern telescopes, even with those having the largest magnification, the images of almost all stars correctly appear as mere points of light.

Astronomer Royal

In June 1835 Airy was appointed

In June 1835 Airy was appointed Astronomer Royal

Astronomer Royal is a senior post in the Royal Households of the United Kingdom. There are two officers, the senior being the Astronomer Royal dating from 22 June 1675; the junior is the Astronomer Royal for Scotland dating from 1834.

The post ...

in succession to John Pond

John Pond FRS (1767 – 7 September 1836) was a renowned English astronomer who became the sixth Astronomer Royal, serving from 1811 to 1835.

Biography

Pond was born in London and, although the year of his birth is known, the records indi ...

, and began his long career at the national observatory which constitutes his chief title to fame. The condition of the observatory at the time of his appointment was such that Lord Auckland

Baron Auckland is a title in both the Peerage of Ireland and the Peerage of Great Britain. The first creation came in 1789 when the prominent politician and financial expert William Eden was made Baron Auckland in the Peerage of Ireland. In ...

, the first Lord of the Admiralty

This is a list of Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty (incomplete before the Restoration, 1660).

The Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty were the members of The Board of Admiralty, which exercised the office of Lord High Admiral when it was ...

, considered that "it ought to be cleared out," while Airy admitted that "it was in a queer state." With his usual energy he set to work at once to reorganise the whole management. He remodelled the volumes of observations, put the library on a proper footing, mounted the new ( Sheepshanks) equatorial Equatorial may refer to something related to:

*Earth's equator

**the tropics, the Earth's equatorial region

**tropical climate

*the Celestial equator

**equatorial orbit

**equatorial coordinate system

**equatorial mount, of telescopes

* equatorial b ...

and organised a new magnetic observatory. In 1847 an altazimuth was erected, designed by Airy to enable observations of the moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width ...

to be made not only on the meridian

Meridian or a meridian line (from Latin ''meridies'' via Old French ''meridiane'', meaning “midday”) may refer to

Science

* Meridian (astronomy), imaginary circle in a plane perpendicular to the planes of the celestial equator and horizon

* ...

, but whenever it might be visible. In 1848 Airy invented the reflex zenith tube to replace the zenith sector

A zenith telescope is a type of telescope that is designed to point straight up at or near the zenith. They are used for precision measurement of star positions, to simplify telescope construction, or both.

A classic zenith telescope, also known ...

previously employed. At the end of 1850 the great transit circle of 203 mm (8 inch) aperture and 3.5 m (11 ft 6 in) focal length

The focal length of an optical system is a measure of how strongly the system converges or diverges light; it is the inverse of the system's optical power. A positive focal length indicates that a system converges light, while a negative foca ...

was erected, and is still the principal instrument of its class at the observatory. The mounting in 1859 of an equatorial of 330 mm (13 inch) aperture evoked the comment in his journal for that year, "There is not now a single person employed or instrument used in the observatory which was there in Mr Pond's time"; and the transformation was completed by the inauguration of spectroscopic

Spectroscopy is the field of study that measures and interprets the electromagnetic spectra that result from the interaction between electromagnetic radiation and matter as a function of the wavelength or frequency of the radiation. Matter ...

work in 1868 and of the photographic registration of sunspots

Sunspots are phenomena on the Sun's photosphere that appear as temporary spots that are darker than the surrounding areas. They are regions of reduced surface temperature caused by concentrations of magnetic flux that inhibit convection. S ...

in 1873.

The formidable undertaking of reducing the accumulated planetary observations made at Greenwich from 1750 to 1830 was already in progress under Airy's supervision when he became Astronomer Royal. Shortly afterwards he undertook the further laborious task of reducing the enormous mass of observations of the moon made at Greenwich during the same period under the direction, successively, of

The formidable undertaking of reducing the accumulated planetary observations made at Greenwich from 1750 to 1830 was already in progress under Airy's supervision when he became Astronomer Royal. Shortly afterwards he undertook the further laborious task of reducing the enormous mass of observations of the moon made at Greenwich during the same period under the direction, successively, of James Bradley

James Bradley (1692–1762) was an English astronomer and priest who served as the third Astronomer Royal from 1742. He is best known for two fundamental discoveries in astronomy, the aberration of light (1725–1728), and the nutation of th ...

, Nathaniel Bliss

Nathaniel Bliss (28 November 1700 – 2 September 1764) was an English astronomer of the 18th century, serving as Britain's fourth Astronomer Royal between 1762 and 1764.

Life

Nathaniel Bliss was born in the Cotswolds village of Bisley i ...

, Nevil Maskelyne

Nevil Maskelyne (; 6 October 1732 – 9 February 1811) was the fifth British Astronomer Royal. He held the office from 1765 to 1811. He was the first person to scientifically measure the mass of the planet Earth. He created the ''British Na ...

and John Pond, to defray the expense of which a large sum of money was allotted by the Treasury. As a result, no fewer than 8,000 lunar observations were rescued from oblivion, and were, in 1846, placed at the disposal of astronomers in such a form that they could be used directly for comparison with the theory and for the improvement of the tables of the moon's motion.

For this work Airy received in 1848 a testimonial from the Royal Astronomical Society

(Whatever shines should be observed)

, predecessor =

, successor =

, formation =

, founder =

, extinction =

, merger =

, merged =

, type = NG ...

, and it at once led to the discovery by Peter Andreas Hansen

Peter Andreas Hansen (born 8 December 1795, Tønder, Schleswig, Denmark; died 28 March 1874, Gotha, Thuringia, Germany) was a Danish-born German astronomer.

Biography

The son of a goldsmith, Hansen learned the trade of a watchmaker at Flensburg, ...

of two new inequalities in the moon's motion. After completing these reductions, Airy made inquiries, before engaging in any theoretical investigation in connection with them, whether any other mathematician was pursuing the subject, and learning that Hansen had taken it in hand under the patronage of the king of Denmark

The monarchy of Denmark is a constitutional political system, institution and a historic office of the Kingdom of Denmark. The Kingdom includes Denmark proper and the autonomous administrative division, autonomous territories of the Faroe ...

, but that, owing to the death of the king and the consequent lack of funds, there was danger of his being compelled to abandon it, he applied to the admiralty on Hansen's behalf for the necessary sum. His request was immediately granted, and thus it came about that Hansen's famous ''Tables de la Lune'' were dedicated to ''La Haute Amirauté de sa Majesté la Reine de la Grande Bretagne et d'Irlande''.

In 1851 Airy established a new Prime Meridian

A prime meridian is an arbitrary meridian (a line of longitude) in a geographic coordinate system at which longitude is defined to be 0°. Together, a prime meridian and its anti-meridian (the 180th meridian in a 360°-system) form a great ...

at Greenwich. This line, the fourth "Greenwich Meridian", became the definitive internationally recognised line in 1884.

Search for Neptune

In June 1846, Airy started corresponding with French astronomer

In June 1846, Airy started corresponding with French astronomer Urbain Le Verrier

Urbain Jean Joseph Le Verrier FRS (FOR) HFRSE (; 11 March 1811 – 23 September 1877) was a French astronomer and mathematician who specialized in celestial mechanics and is best known for predicting the existence and position of Neptune using ...

over the latter's prediction that irregularities in the motion of Uranus

Uranus is the seventh planet from the Sun. Its name is a reference to the Greek god of the sky, Uranus (Caelus), who, according to Greek mythology, was the great-grandfather of Ares (Mars), grandfather of Zeus (Jupiter) and father of Cronu ...

were due to a so-far unobserved body. Aware that Cambridge Astronomer John Couch Adams

John Couch Adams (; 5 June 1819 – 21 January 1892) was a British mathematician and astronomer. He was born in Laneast, near Launceston, Cornwall, and died in Cambridge.

His most famous achievement was predicting the existence and position o ...

had suggested that he had made similar predictions, on 9 July Airy urged James Challis

James Challis FRS (12 December 1803 – 3 December 1882) was an English clergyman, physicist and astronomer. Plumian Professor of Astronomy and Experimental Philosophy and the director of the Cambridge Observatory, he investigated a wide r ...

to undertake a systematic search in the hope of securing the triumph of discovery for Britain. Ultimately, a rival search in Berlin by Johann Gottfried Galle

Johann Gottfried Galle (9 June 1812 – 10 July 1910) was a German astronomer from Radis, Germany, at the Berlin Observatory who, on 23 September 1846, with the assistance of student Heinrich Louis d'Arrest, was the first person to view the ...

, instigated by Le Verrier, won the race for priority. Though Airy was "abused most savagely both by English and French" for his failure to act on Adams's suggestions more promptly, there have also been claims that Adams's communications had been vague and dilatory and further that the search for a new planet was not the responsibility of the Astronomer Royal.

Ether drag test

Using a water-filledtelescope

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, absorption, or reflection of electromagnetic radiation. Originally meaning only an optical instrument using lenses, curved mirrors, or a combination of both to obse ...

, in 1871 Airy looked for a change in stellar aberration

In astronomy, aberration (also referred to as astronomical aberration, stellar aberration, or velocity aberration) is a phenomenon which produces an apparent motion of celestial objects about their true positions, dependent on the velocity of t ...

through the refract

In physics, refraction is the redirection of a wave as it passes from one medium to another. The redirection can be caused by the wave's change in speed or by a change in the medium. Refraction of light is the most commonly observed phenomen ...

ing water due to the aether drag hypothesis

In the 19th century, the theory of the luminiferous aether as the hypothetical medium for the propagation of light waves was widely discussed. The aether hypothesis arose because physicists of that era could not conceive of light waves propagating ...

. Like all other attempts to detect aether drift or drag, Airy obtained a negative result.

Lunar theory

In 1872 Airy conceived the idea of treating thelunar theory Lunar theory attempts to account for the motions of the Moon. There are many small variations (or perturbations) in the Moon's motion, and many attempts have been made to account for them. After centuries of being problematic, lunar motion can now b ...

in a new way, and at the age of seventy-one he embarked on the prodigious toil which this scheme entailed. A general description of his method will be found in the ''Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society

''Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society'' (MNRAS) is a peer-reviewed scientific journal covering research in astronomy and astrophysics. It has been in continuous existence since 1827 and publishes letters and papers reporting origina ...

'', vol. xxxiv, No. 3. It consisted essentially in the adoption of Charles-Eugène Delaunay

Charles-Eugène Delaunay (9 April 1816 – 5 August 1872) was a French astronomer and mathematician. His lunar motion studies were important in advancing both the theory of planetary motion and mathematics.

Life

Born in Lusigny-sur-Barse ...

's final numerical expressions for longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east– west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek let ...

, latitude

In geography, latitude is a coordinate that specifies the north– south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from –90° at the south pole to 90° at the north po ...

, and parallax

Parallax is a displacement or difference in the apparent position of an object viewed along two different lines of sight and is measured by the angle or semi-angle of inclination between those two lines. Due to foreshortening, nearby object ...

, with a symbolic term attached to each number, the value of which was to be determined by substitution in the equations of motion.

In this mode of treating the question the order of the terms is numerical, and though the amount of labour is such as might well have deterred a younger man, yet the details were easy, and a great part of it might be entrusted to "a mere computer".

The work was published in 1886, when its author was eighty-five years of age. For some little time previously he had been harassed by a suspicion that certain errors had crept into the computations, and accordingly he addressed himself to the task of revision. But his powers were no longer what they had been, and he was never able to examine sufficiently into the matter. In 1890 he tells us how a grievous error had been committed in one of the first steps, and pathetically adds, "My spirit in the work was broken, and I have never heartily proceeded with it since."

Engineering mechanics

=Stress function method

= In 1862, Airy presented a new technique to determine thestrain

Strain may refer to:

Science and technology

* Strain (biology), variants of plants, viruses or bacteria; or an inbred animal used for experimental purposes

* Strain (chemistry), a chemical stress of a molecule

* Strain (injury), an injury to a mu ...

and stress field within a beam

Beam may refer to:

Streams of particles or energy

* Light beam, or beam of light, a directional projection of light energy

** Laser beam

* Particle beam, a stream of charged or neutral particles

**Charged particle beam, a spatially localized g ...

. This technique, sometimes called the Airy stress function method, can be used to find solutions to many two-dimensional problems in solid mechanics

Solid mechanics, also known as mechanics of solids, is the branch of continuum mechanics that studies the behavior of solid materials, especially their motion and deformation under the action of forces, temperature changes, phase changes, and ...

(see Wikiversity

Wikiversity is a Wikimedia Foundation project that supports learning communities, their learning materials, and resulting activities. It differs from Wikipedia in that it offers tutorials and other materials for the fostering of learning, rather ...

). For example, it was used by H. M. Westergaard to determine the stress and strain field around a crack tip and thereby this method contributed to the development of fracture mechanics

Fracture mechanics is the field of mechanics concerned with the study of the propagation of cracks in materials. It uses methods of analytical solid mechanics to calculate the driving force on a crack and those of experimental solid mechanics ...

.

=Tay Bridge disaster

=

Thomas Bouch

Sir Thomas Bouch (; 25 February 1822 – 30 October 1880) was a British railway engineer. He was born in Thursby, near Carlisle, Cumberland, and lived in Edinburgh. As manager of the Edinburgh and Northern Railway he introduced the first roll ...

for the North British Railway

The North British Railway was a British railway company, based in Edinburgh, Scotland. It was established in 1844, with the intention of linking with English railways at Berwick. The line opened in 1846, and from the outset the company followe ...

in the late 1870s. He thought that pressures no greater than about could be expected, a comment Bouch took to mean also applied to the first Tay railway bridge then being built. Much greater pressures, however, can be expected in severe storms. Airy was called to give evidence before the Official Inquiry into the Tay Bridge disaster

The Tay Bridge disaster occurred during a violent storm on Sunday 28 December 1879, when the first Tay Rail Bridge collapsed as a North British Railway (NBR) passenger train on the Edinburgh to Aberdeen Line from Burntisland bound for its fina ...

, and was criticised for his advice. However, little was known about the problems of wind resistance of large structures, and a Royal Commission on Wind Pressure was asked to conduct research into the problem.

Controversy

Airy was described in his obituary published by theRoyal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, r ...

as being "a tough adversary" and stories of various disagreements and conflicts with other scientists survive. Francis Ronalds

Sir Francis Ronalds FRS (21 February 17888 August 1873) was an English scientist and inventor, and arguably the first electrical engineer. He was knighted for creating the first working electric telegraph over a substantial distance. In 1816 ...

discovered Airy to be his foe while he was inaugural Honorary Director of the Kew Observatory

The King's Observatory (called for many years the Kew Observatory) is a Grade I listed building in Richmond, London. Now a private dwelling, it formerly housed an astronomical and terrestrial magnetic observatory founded by King George III. T ...

, which Airy considered to be a competitor to Greenwich. Other well documented conflicts were with Charles Babbage

Charles Babbage (; 26 December 1791 – 18 October 1871) was an English polymath. A mathematician, philosopher, inventor and mechanical engineer, Babbage originated the concept of a digital programmable computer.

Babbage is considered ...

and Sir James South

Sir James South FRS FRSE PRAS FLS LLD (October 1785 – 19 October 1867) was a British astronomer.

He was a joint founder of the Astronomical Society of London, and it was under his name, as President of the Society in 1831, that a peti ...

.

Private life

In July 1824, Airy met Richarda Smith (1804–1875), "a great beauty", on a walking tour ofDerbyshire

Derbyshire ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands, England. It includes much of the Peak District National Park, the southern end of the Pennine range of hills and part of the National Forest. It borders Greater Manchester to the no ...

. He later wrote, "Our eyes met ... and my fate was sealed ... I felt irresistibly that we must be united," and Airy proposed two days later. Richarda's father, the Revd Richard Smith, felt that Airy lacked the financial resources to marry his daughter. Only in 1830, with Airy established in his Cambridge position, was permission for the marriage granted.

The Airys had nine children, the first three of whom died young.

*Elizabeth Airy (born 1833) died of consumption (

The Airys had nine children, the first three of whom died young.

*Elizabeth Airy (born 1833) died of consumption (tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in w ...

) in 1852.

*The eldest child to survive to adulthood was Wilfrid (1836–1925), who designed and engineered "Colonel" George Tomline

George Tomline (3 March 1813 – 25 August 1889), referred to as Colonel Tomline, was an English politician who served as Member of Parliament (MP) for various constituencies. He was the son of William Edward Tomline and grandson of George Pretym ...

's Orwell Park Observatory. Wilfrid's daughter was the artist Anna Airy

Anna Airy (6 June 1882 – 23 October 1964) was an English oil painter, pastel artist and etcher. She was one of the first women officially commissioned as a war artist and was recognised as one of the leading women artists of her generation.

...

. Anna's mother died shortly after she was born and she was raised by her maiden aunts Christabel and Annot (see below).

*George Airy's son Hubert Airy

Hubert Airy (June 14, 1838 – June 1, 1903) was an English physician who was the pioneer in the study of a migraine. He was the son of Sir George Airy, Astronomer Royal. He has two portraits in the National Portrait Gallery.

He was one of the ...

(1838–1903) was a doctor, and a pioneer in the study of migraine

Migraine (, ) is a common neurological disorder characterized by recurrent headaches. Typically, the associated headache affects one side of the head, is pulsating in nature, may be moderate to severe in intensity, and could last from a few ho ...

. Airy himself suffered from this condition.

*The Airys' eldest daughter, Hilda (1840–1916), married the mathematician Edward Routh

Edward John Routh (; 20 January 18317 June 1907), was an English mathematician, noted as the outstanding coach of students preparing for the Mathematical Tripos examination of the University of Cambridge in its heyday in the middle of the ninet ...

in 1864.

*Christabel (1842–1917) died unmarried, as did the next sister Annot (1843–1924).

*The Airys youngest child was Osmund (1845–1929).

Airy was knighted on 17 June 1872.

Airy retired in 1881, living with his two unmarried daughters at Croom's Hill near Greenwich. In 1891, he suffered a fall and an internal injury. He survived the consequential surgery only a few days. His wealth at death was £27,713, equivalent to £3,746,548.49 in 2021. Airy and his wife and three pre-deceased children are buried at St. Mary's Church in Playford, Suffolk

Playford is a small village in Suffolk, England, on the outskirts of Ipswich. It has about 215 residents in 90 households. The name comes from the Old English '' plega'' meaning play, sport; used of a place for games, or a courtship or mating-pl ...

. A cottage owned by Airy still stands, adjacent to the church and now in private hands.

Sir Patrick Moore

Sir Patrick Alfred Caldwell-Moore (; 4 March 1923 – 9 December 2012) was an English amateur astronomer who attained prominence in that field as a writer, researcher, radio commentator and television presenter.

Moore was president of the Br ...

asserted in his autobiography that the ghost of Airy has been seen haunting the Royal Greenwich Observatory after nightfall. (page 178)

Legacy and honours

* Elected president of theRoyal Astronomical Society

(Whatever shines should be observed)

, predecessor =

, successor =

, formation =

, founder =

, extinction =

, merger =

, merged =

, type = NG ...

four times, for a total of seven years (1835–37, 1849–51, 1853–55, 1863–64). No other person has been president more than four times (a record he shares with Francis Baily

Francis Baily (28 April 177430 August 1844) was an English astronomer. He is most famous for his observations of " Baily's beads" during a total eclipse of the Sun. Baily was also a major figure in the early history of the Royal Astronomical S ...

).

* Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, ...

(1832)

*The Martian crater Airy

Airy may refer to:

* Sir George Biddell Airy (1801–1892), British Astronomer Royal from 1835 to 1881, for whom the following features, phenomena, and theories are named:

** Airy (lunar crater)

** Airy (Martian crater)

** Airy-0, a smaller crater ...

is named for him. Within that crater lies another smaller crater called Airy-0

Airy-0 is a crater inside the larger Airy Crater on Mars, whose location defined the position of the prime meridian of that planet. It is about 0.5 km (0.3 mile) across and lies within the dark region Sinus Meridiani, one of the early ...

whose location defines the prime meridian

A prime meridian is an arbitrary meridian (a line of longitude) in a geographic coordinate system at which longitude is defined to be 0°. Together, a prime meridian and its anti-meridian (the 180th meridian in a 360°-system) form a great ...

of that planet, as does the location of Airy's 1850 telescope for Earth.

*winner of the Lalande Prize

The Lalande Prize (French: ''Prix Lalande'' also known as Lalande Medal) was an award for scientific advances in astronomy, given from 1802 until 1970 by the French Academy of Sciences.

The prize was endowed by astronomer Jérôme Lalande in 1801 ...

for astronomy from the French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (French: ''Académie des sciences'') is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French scientific research. It was at th ...

, 1834

*Elected as a member of the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communi ...

in 1879.

*There is also a lunar crater

Lunar craters are impact craters on Earth's Moon. The Moon's surface has many craters, all of which were formed by impacts. The International Astronomical Union currently recognizes 9,137 craters, of which 1,675 have been dated.

History

The wor ...

Airy

Airy may refer to:

* Sir George Biddell Airy (1801–1892), British Astronomer Royal from 1835 to 1881, for whom the following features, phenomena, and theories are named:

** Airy (lunar crater)

** Airy (Martian crater)

** Airy-0, a smaller crater ...

named in his honour.

*Airy wave theory

In fluid dynamics, Airy wave theory (often referred to as linear wave theory) gives a linearised description of the propagation of gravity waves on the surface of a homogeneous fluid layer. The theory assumes that the fluid layer has a uniform me ...

is the linear theory for the propagation of gravity waves

In fluid dynamics, gravity waves are waves generated in a fluid medium or at the interface between two media when the force of gravity or buoyancy tries to restore equilibrium. An example of such an interface is that between the atmosphere a ...

on the surface of a fluid

In physics, a fluid is a liquid, gas, or other material that continuously deforms (''flows'') under an applied shear stress, or external force. They have zero shear modulus, or, in simpler terms, are substances which cannot resist any shea ...

.

* The Airy function

In the physical sciences, the Airy function (or Airy function of the first kind) is a special function named after the British astronomer George Biddell Airy (1801–1892). The function and the related function , are linearly independent soluti ...

s Ai(x) and Bi(x) and the differential equation they arise from are named in his honour, as well as the Airy disc

In optics, the Airy disk (or Airy disc) and Airy pattern are descriptions of the best- focused spot of light that a perfect lens with a circular aperture can make, limited by the diffraction of light. The Airy disk is of importance in physics ...

and Airy points Airy points (after George Biddell Airy) are used for precision measurement (metrology) to support a length standard in such a way as to minimise bending or drop of a horizontally supported beam.

Choice of support points

A kinematic support fo ...

.

*Honorary Fellow of the Institution of Engineering and Technology

The Institution of Engineering and Technology (IET) is a multidisciplinary professional engineering institution. The IET was formed in 2006 from two separate institutions: the Institution of Electrical Engineers (IEE), dating back to 1871, and ...

.

Bibliography

;By Airy

'' For a list of works by George Biddell Airy (with digital copies) see Wikisource.''

A complete list of Airy's 518 printed papers is in Airy (1896). Among the most important are:

*(1826) ''Mathematical Tracts on Physical Astronomy''

* (1828) ''On the Lunar Theory, The Figure of the Earth, Precession and Nutation, and Calculus of Variations'', to which, in the second edition of 1828, were added tracts on the ''Planetary Theory'' and the ''Undulatory Theory of Light''

* (1834) ''Gravitation: an Elementary Explanation of the Principal Perturbations in the Solar System'' (

;By Airy

'' For a list of works by George Biddell Airy (with digital copies) see Wikisource.''

A complete list of Airy's 518 printed papers is in Airy (1896). Among the most important are:

*(1826) ''Mathematical Tracts on Physical Astronomy''

* (1828) ''On the Lunar Theory, The Figure of the Earth, Precession and Nutation, and Calculus of Variations'', to which, in the second edition of 1828, were added tracts on the ''Planetary Theory'' and the ''Undulatory Theory of Light''

* (1834) ''Gravitation: an Elementary Explanation of the Principal Perturbations in the Solar System'' (Full text

In text retrieval, full-text search refers to techniques for searching a single computer-stored document or a collection in a full-text database. Full-text search is distinguished from searches based on metadata or on parts of the original texts ...

at Internet Archive)

* (1839) ''Experiments on Iron-built Ships, instituted for the purpose of discovering a correction for the deviation of the Compass produced-by the Iron of the Ships''

* (1848 881, 10th edition ''Popular Astronomy: A Series of Lectures Delivered at Ipswich'' (Full text

In text retrieval, full-text search refers to techniques for searching a single computer-stored document or a collection in a full-text database. Full-text search is distinguished from searches based on metadata or on parts of the original texts ...

at Wikisource)

* (1855) ''A Treatise on Trigonometry''Full text

at Google Books) *(1861) ''On the Algebraic and Numerical Theory of Errors of Observations and the Combination of Observations''. *(1866) ''An Elementary Treatise on Partial Differential Equations'' (

Full text

In text retrieval, full-text search refers to techniques for searching a single computer-stored document or a collection in a full-text database. Full-text search is distinguished from searches based on metadata or on parts of the original texts ...

at Internet Archive)

*(1868) ''On Sound and Atmospheric Vibrations with the Mathematical Elements of Music''Full text

at MPIWG) *(1870) ''A Treatise on Magnetism''

Full text

at Google Books) ;About Airy * * * *

References

Notes

Citations

Sources

*Further reading

*Obituaries

* E. J. R., ''Proceedings of the Royal Society'', 51 (1892), i–xii *''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ...

'', 5 January 1892

*''East Anglian Daily Times'', 11 January 1892

*''Suffolk Chronicle'', 9 January 1892

*''Daily Times'', 5 January 1892

*

*''Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers'', 108 (1891–92), 391–394

''Astronomical Journal'' 11 (1892) 96

* Obituary in:

External links

* * * * * * **

Mathematical Tracts on the Lunar and Planetary Theories 4th edition

(London, McMillan, 1858) * Full texts of some of the papers by Airy are available at

Gallica: bibliothèque numérique de la Bibliothèque nationale de France

' * {{DEFAULTSORT:Airy, George Biddell 1801 births 1892 deaths 19th-century British astronomers Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge Astronomers Royal Corresponding members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Fellows of the Royal Society Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences Honorary Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath Lucasian Professors of Mathematics Members of the Prussian Academy of Sciences Members of the Royal Academy of Belgium Members of the Royal Irish Academy Members of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences People educated at Colchester Royal Grammar School People from Alnwick People from Suffolk Coastal (district) Presidents of the Royal Astronomical Society Presidents of the Royal Society Recipients of the Copley Medal Recipients of the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society Recipients of the Lalande Prize Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class) Royal Medal winners Senior Wranglers George Biddell Plumian Professors of Astronomy and Experimental Philosophy Members of the Göttingen Academy of Sciences and Humanities