Geneva Conference (1976) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Geneva Conference (28 October – 14 December 1976) took place in

Following a dispute over the terms for the granting of full statehood, the predominantly white minority

Following a dispute over the terms for the granting of full statehood, the predominantly white minority

The

The

Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

, Switzerland during the Rhodesian Bush War

The Rhodesian Bush War, also called the Second as well as the Zimbabwe War of Liberation, was a civil conflict from July 1964 to December 1979 in the unrecognised country of Rhodesia (later Zimbabwe-Rhodesia).

The conflict pitted three for ...

. Held under British mediation, its participants were the unrecognised government of Rhodesia

Rhodesia (, ), officially from 1970 the Republic of Rhodesia, was an unrecognised state in Southern Africa from 1965 to 1979, equivalent in territory to modern Zimbabwe. Rhodesia was the ''de facto'' successor state to the British colony of S ...

, led by Ian Smith

Ian Douglas Smith (8 April 1919 – 20 November 2007) was a Rhodesian politician, farmer, and fighter pilot who served as Prime Minister of Rhodesia (known as Southern Rhodesia until October 1964 and now known as Zimbabwe) from 1964 to ...

, and a number of rival Rhodesian black nationalist parties: the African National Council

The United African National Council (UANC) is a political party in Zimbabwe. It was briefly the ruling party during 1979–1980, when its leader Abel Muzorewa was Prime Minister.

History

The party was founded by Muzorewa in 1971.< ...

, led by Bishop Abel Muzorewa

Abel Tendekayi Muzorewa (14 April 1925 – 8 April 2010), also commonly referred to as Bishop Muzorewa, was a Zimbabwean bishop and politician who served as the first and only Prime Minister of Zimbabwe Rhodesia from the Internal Settlement to ...

; the Front for the Liberation of Zimbabwe The Front for the Liberation of Zimbabwe (FROLIZI) was an African nationalism, African nationalist organisation established in opposition to the white minority government of Rhodesia. It was announced in Lusaka, Zambia in October 1971 as a merger of ...

, led by James Chikerema

James Robert Dambaza Chikerema (2 April 1925 – 22 March 2006) served as the President of the Front for the Liberation of Zimbabwe.Nyangoni, Wellington Winter. ''Africa in the United Nations System.'' Page 141. He changed his views on militant s ...

; and a joint "Patriotic Front" made up of Robert Mugabe

Robert Gabriel Mugabe (; ; 21 February 1924 – 6 September 2019) was a Zimbabwean revolutionary and politician who served as Prime Minister of Zimbabwe from 1980 to 1987 and then as President from 1987 to 2017. He served as Leader of the ...

's Zimbabwe African National Union

The Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) was a militant organisation that fought against white minority rule in Rhodesia, formed as a split from the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU). ZANU split in 1975 into wings loyal to Robert Muga ...

and the Zimbabwe African People's Union

The Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU) is a Zimbabwean political party. It is a militant organization and political party that campaigned for majority rule in Rhodesia, from its founding in 1961 until 1980. In 1987, it merged with the Zimba ...

led by Joshua Nkomo

Joshua Mqabuko Nyongolo Nkomo (19 June 1917 – 1 July 1999) was a Zimbabwean revolutionary and Matabeleland politician who served as Vice-President of Zimbabwe from 1990 until his death in 1999. He founded and led the Zimbabwe African People's ...

. The purpose of the conference was to attempt to agree on a new constitution for Rhodesia and in doing so find a way to end the Bush War raging between the government and the guerrillas commanded by Mugabe and Nkomo respectively.

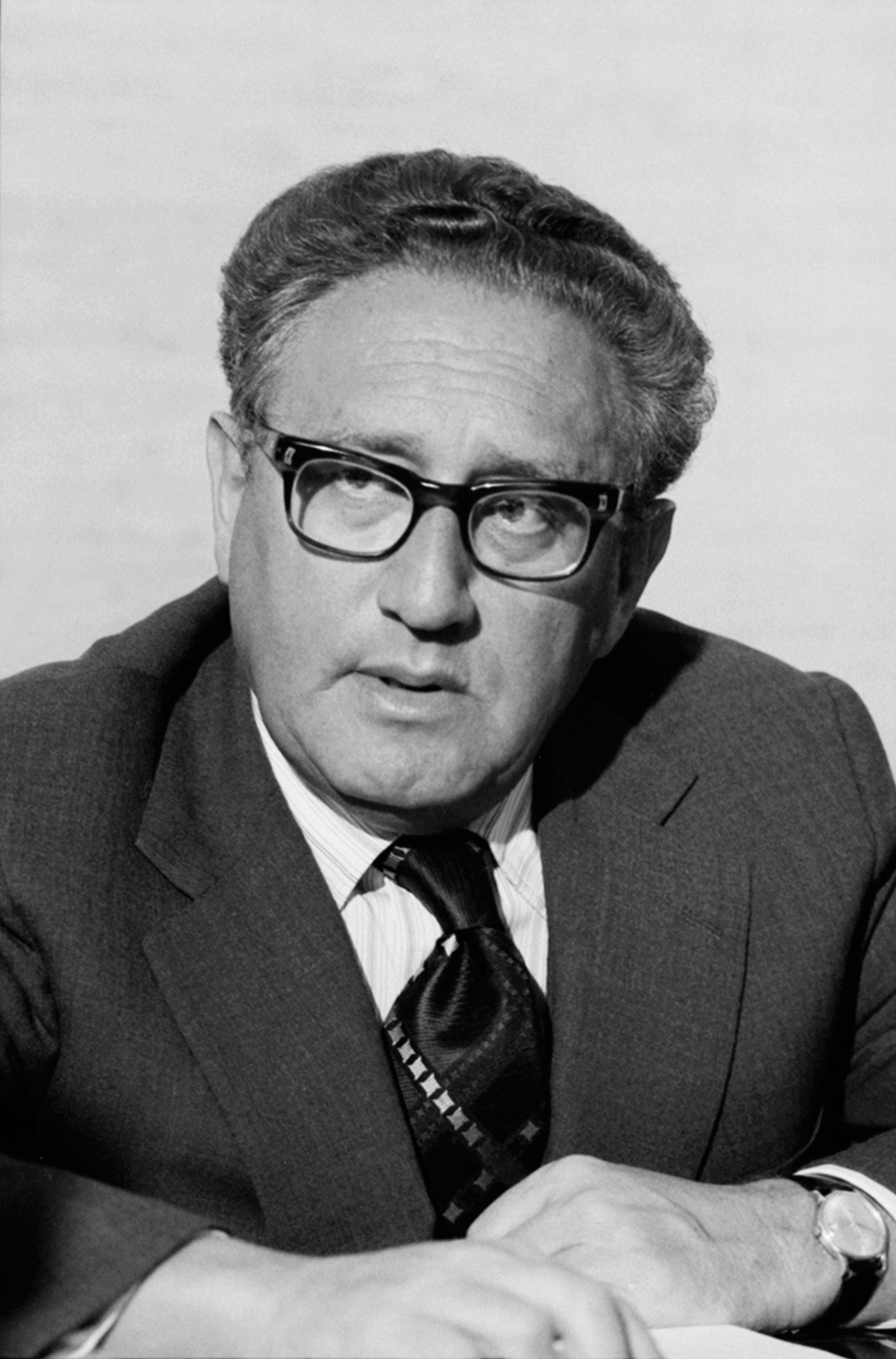

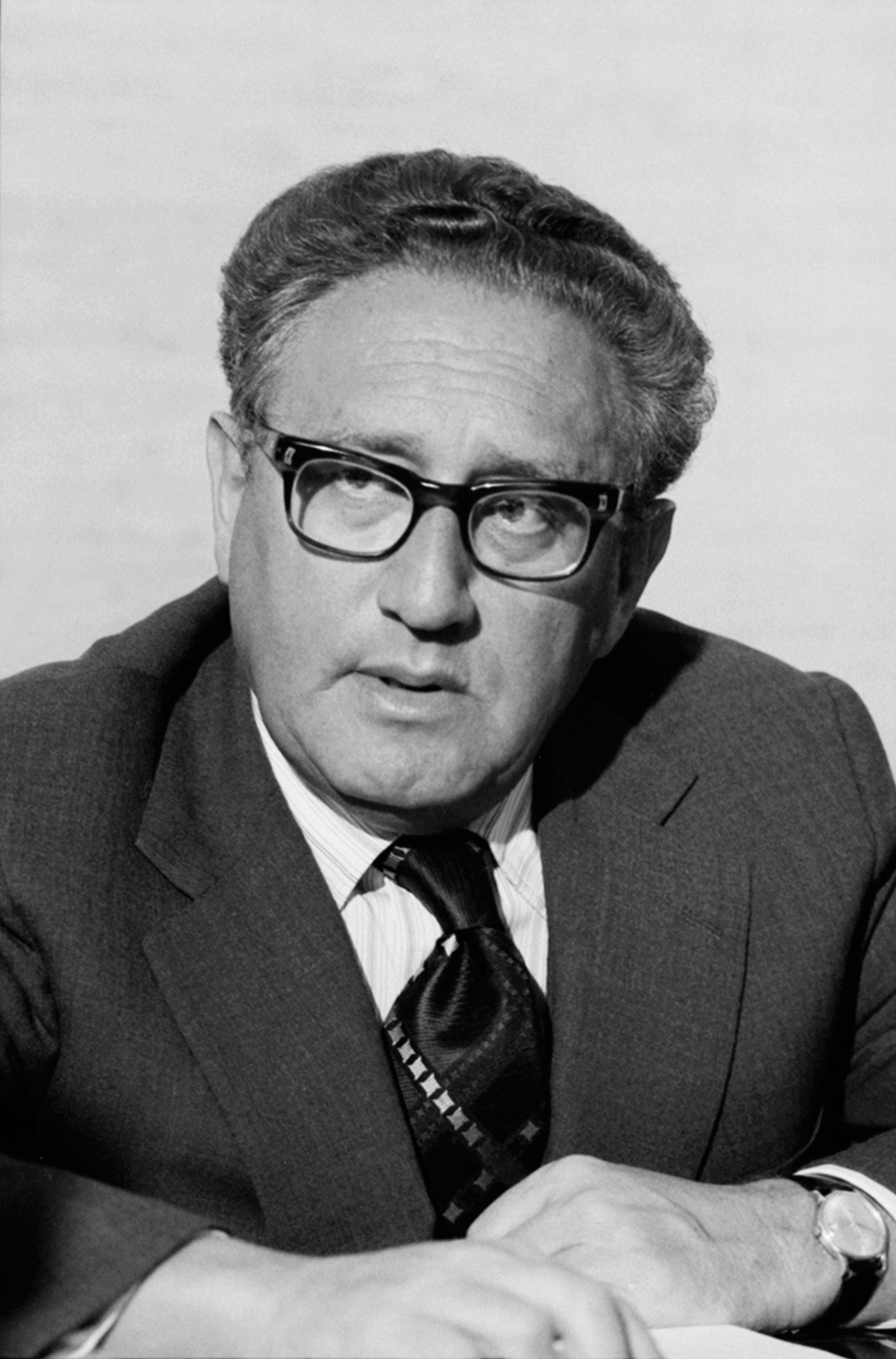

The Geneva Conference had its origins in the South African "détente" policy instituted in late 1974, and more directly in the peace initiative headed by the United States Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State. The office holder is one of the highest ranking members of the president's Ca ...

, Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (; ; born Heinz Alfred Kissinger, May 27, 1923) is a German-born American politician, diplomat, and geopolitical consultant who served as United States Secretary of State and National Security Advisor under the presid ...

, earlier in 1976. After the Kissinger plan was rejected by the nationalists, talks were organised in Geneva by Britain to try to salvage a deal. The proceedings began on 28 October 1976, eight days behind schedule, and were chaired by a British mediator, Ivor Richard

Ivor Seward Richard, Baron Richard, (30 May 1932 – 18 March 2018) was a British Labour politician who served as a member of Parliament (MP) from 1964 until 1974. He was also a member of the European Commission and latterly sat as a life pee ...

, who offended both delegations before the conference even started. When Richard read an opening statement from British prime minister James Callaghan

Leonard James Callaghan, Baron Callaghan of Cardiff, ( ; 27 March 191226 March 2005), commonly known as Jim Callaghan, was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1976 to 1979 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1976 to 1980. Callaghan is ...

which referred to the country as "Zimbabwe", the nationalists were somewhat placated, while Smith's team was insulted yet further. Little progress was made during the two sides' discussions, causing the conference to be indefinitely adjourned on 14 December 1976. It was never reconvened.

Background

Following a dispute over the terms for the granting of full statehood, the predominantly white minority

Following a dispute over the terms for the granting of full statehood, the predominantly white minority government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

of Rhodesia, headed by Prime Minister Ian Smith

Ian Douglas Smith (8 April 1919 – 20 November 2007) was a Rhodesian politician, farmer, and fighter pilot who served as Prime Minister of Rhodesia (known as Southern Rhodesia until October 1964 and now known as Zimbabwe) from 1964 to ...

, unilaterally declared independence from Britain on 11 November 1965. Because British prime minister Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, (11 March 1916 – 24 May 1995) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from October 1964 to June 1970, and again from March 1974 to April 1976. He ...

and Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London. The road forms the first part of the A roads in Zone 3 of the Great Britain numbering scheme, A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea, London, Chelsea. It is the main ...

had been insisting on an immediate transfer to majority rule before independence, this declaration went unrecognised and caused Britain and the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

(UN) to impose economic sanctions on Rhodesia.

The two most prominent black nationalist

Black nationalism is a type of racial nationalism or pan-nationalism which espouses the belief that black people are a race (human categorization), race, and which seeks to develop and maintain a black racial and national identity. Black natio ...

parties in Rhodesia were the Zimbabwe African National Union

The Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) was a militant organisation that fought against white minority rule in Rhodesia, formed as a split from the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU). ZANU split in 1975 into wings loyal to Robert Muga ...

(ZANU)—a predominantly Shona

Shona often refers to:

* Shona people, a Southern African people

* Shona language, a Bantu language spoken by Shona people today

Shona may also refer to:

* ''Shona'' (album), 1994 album by New Zealand singer Shona Laing

* Shona (given name)

* S ...

movement, influenced by Chinese Maoism

Maoism, officially called Mao Zedong Thought by the Chinese Communist Party, is a variety of Marxism–Leninism that Mao Zedong developed to realise a socialist revolution in the agricultural, pre-industrial society of the Republic of Chi ...

—and the Zimbabwe African People's Union

The Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU) is a Zimbabwean political party. It is a militant organization and political party that campaigned for majority rule in Rhodesia, from its founding in 1961 until 1980. In 1987, it merged with the Zimba ...

(ZAPU), which was Marxist–Leninist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialect ...

, and mostly Ndebele

Ndebele may refer to:

*Southern Ndebele people, located in South Africa

*Northern Ndebele people, located in Zimbabwe and Botswana

Languages

* Southern Ndebele language, the language of the South Ndebele

*Northern Ndebele language

Northern ...

. ZANU and its military wing, the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army

Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA) was the military wing of the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU), a militant African nationalist organisation that participated in the Rhodesian Bush War against white minority rule of Rhod ...

(ZANLA), received considerable backing in training, materiel and finances from the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

and its allies, while the Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist republic ...

and associated nations, prominently Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

, gave similar support to ZAPU and its Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army

Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA) was the military wing of the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU), a Marxist–Leninist political party in Rhodesia. It participated in the Rhodesian Bush War against white minority rule of Rhodes ...

(ZIPRA).; ZAPU and ZIPRA were headed by Joshua Nkomo

Joshua Mqabuko Nyongolo Nkomo (19 June 1917 – 1 July 1999) was a Zimbabwean revolutionary and Matabeleland politician who served as Vice-President of Zimbabwe from 1990 until his death in 1999. He founded and led the Zimbabwe African People's ...

throughout their existence, while the Reverend Ndabaningi Sithole

Ndabaningi Sithole (21 July 1920 – 12 December 2000) founded the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU), a militant organisation that opposed the government of Rhodesia, in July 1963.Veenhoven, Willem Adriaan, Ewing, and Winifred Crum. ''Cas ...

founded and initially led ZANU. The two rival nationalist movements launched what they called their "Second ''Chimurenga

''Chimurenga'' is a word in the Shona language. The Ndebele equivalent, though not as widely used since the majority of Zimbabweans are Shona speaking, is ''Umvukela'', meaning "revolutionary struggle" or uprising. In specific historical term ...

''" against the Rhodesian government and security forces

Security forces are statutory organizations with internal security mandates. In the legal context of several nations, the term has variously denoted police and military units working in concert, or the role of military and paramilitary forces (s ...

during the mid-1960s. The army, air force

An air force – in the broadest sense – is the national military branch that primarily conducts aerial warfare. More specifically, it is the branch of a nation's armed services that is responsible for aerial warfare as distinct from an a ...

and police

The police are a constituted body of persons empowered by a state, with the aim to enforce the law, to ensure the safety, health and possessions of citizens, and to prevent crime and civil disorder. Their lawful powers include arrest and t ...

successfully repulsed numerous guerrilla incursions, most of which were perpetrated by ZIPRA, over the rest of that decade.

After abortive talks between Smith and Wilson in 1966 and 1968, a constitution was agreed upon by the Rhodesian and British governments in November 1971; however, when a British test of Rhodesian public opinion was undertaken in early 1972, black opinion was judged to be against the new deal, causing it to be shelved. The Rhodesian Bush War

The Rhodesian Bush War, also called the Second as well as the Zimbabwe War of Liberation, was a civil conflict from July 1964 to December 1979 in the unrecognised country of Rhodesia (later Zimbabwe-Rhodesia).

The conflict pitted three for ...

suddenly re-erupted in December 1972, after two years of relative inactivity, when ZANLA attacked Altena and Whistlefield Farms in north-eastern Rhodesia. After a successful security force counter-campaign during 1973 and 1974, drastic changes in the foreign policy of the Rhodesian government's two main backers, Portugal and South Africa, caused the conflict's momentum to shift in the nationalists' favour. In April 1974, the Portuguese government was overthrown by a military coup

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such ...

and replaced with a leftist administration in favour of ending the unpopular Colonial War

Colonial war (in some contexts referred to as small war) is a blanket term relating to the various conflicts that arose as the result of overseas territories being settled by foreign powers creating a colony. The term especially refers to wars ...

in Angola

, national_anthem = " Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordina ...

, Mozambique

Mozambique (), officially the Republic of Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique or , ; ny, Mozambiki; sw, Msumbiji; ts, Muzambhiki), is a country located in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi ...

and Portugal's other African territories.

The institution by Pretoria

Pretoria () is South Africa's administrative capital, serving as the seat of the Executive (government), executive branch of government, and as the host to all foreign embassies to South Africa.

Pretoria straddles the Apies River and extends ...

of a détente initiative in late 1974 forced a ceasefire in Rhodesia, and in June 1975 Mozambique became independent from Portugal under a communist government allied with ZANU. Unsuccessful rounds of talks were held between the Rhodesian government and the nationalists, united under the banner of Abel Muzorewa

Abel Tendekayi Muzorewa (14 April 1925 – 8 April 2010), also commonly referred to as Bishop Muzorewa, was a Zimbabwean bishop and politician who served as the first and only Prime Minister of Zimbabwe Rhodesia from the Internal Settlement to ...

's African National Council

The United African National Council (UANC) is a political party in Zimbabwe. It was briefly the ruling party during 1979–1980, when its leader Abel Muzorewa was Prime Minister.

History

The party was founded by Muzorewa in 1971.< ...

, across the Victoria Falls Bridge in August 1975, then directly between the government and ZAPU starting in December 1975. Around this time, Robert Mugabe

Robert Gabriel Mugabe (; ; 21 February 1924 – 6 September 2019) was a Zimbabwean revolutionary and politician who served as Prime Minister of Zimbabwe from 1980 to 1987 and then as President from 1987 to 2017. He served as Leader of the ...

replaced Sithole as ZANU leader, winning an internal leadership election which Sithole refused to recognise. Guerrilla incursions picked up strongly in the first months of 1976, leading Smith to declare on the evening of 6 February 1976 that "a new terrorist offensive has begun and, to defeat it, Rhodesians will have to face heavier military commitments." Security force reports indicated that around 1,000 insurgent fighters were active within Rhodesia, with a further 15,000 encamped in various states of readiness in Mozambique.

Prelude: Kissinger initiative

The

The United States Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State. The office holder is one of the highest ranking members of the president's Ca ...

, Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (; ; born Heinz Alfred Kissinger, May 27, 1923) is a German-born American politician, diplomat, and geopolitical consultant who served as United States Secretary of State and National Security Advisor under the presid ...

, announced a formal interest in the Rhodesian situation in February 1976, and spent the rest of the year holding discussions with the British, South African and Frontline

Front line refers to the forward-most forces on a battlefield.

Front line, front lines or variants may also refer to:

Books and publications

* ''Front Lines'' (novel), young adult historical novel by American author Michael Grant

* ''Frontlines ...

governments to produce a mutually satisfactory proposal. The plan that Kissinger eventually presented would give a transition period of two years before majority rule began, during which time an interim government would take control while a specially convened "council of state", made up of three whites, three blacks and a white chairman, drew up a new constitution. This constitution would have to result in majority rule at the end of the two-year interim period. This plan was supported by Kenneth Kaunda

Kenneth David Kaunda (28 April 1924 – 17 June 2021), also known as KK, was a Zambian politician who served as the first President of Zambia from 1964 to 1991. He was at the forefront of the struggle for independence from British rule. Dissat ...

and Julius Nyerere

Julius Kambarage Nyerere (; 13 April 1922 – 14 October 1999) was a Tanzanian anti-colonial activist, politician, and political theorist. He governed Tanganyika as prime minister from 1961 to 1962 and then as president from 1962 to 1964, aft ...

, the presidents of Zambia and Tanzania respectively, which South African Prime Minister B. J. Vorster

Balthazar Johannes "B. J." Vorster (; also known as John Vorster; 13 December 1915 – 10 September 1983) was a South African apartheid politician who served as the prime minister of South Africa from 1966 to 1978 and the fourth state presid ...

said guaranteed its acceptance by the black nationalists. Vorster had no reply when Smith ventured that he had said the same thing before the Victoria Falls talks in 1975, when Kaunda and Nyerere had agreed on no preconditions for talks, then allowed the nationalists to seek them.

Smith met Kissinger in Pretoria on 18 September 1976 to discuss the terms. The American diplomat told the prime minister that although he was obliged to take part, his participation in what he termed the "demise of Rhodesia" was "one of the great tragedies of my life". All the same, he encouraged Smith strongly to accept the deal he placed on the table, though he knew it was unpalatable, as any future offer could only be worse. Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

opinion was already "soft and decadent", Kissinger warned, and would become even more so if, as projected, American President Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. ( ; born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was an American politician who served as the 38th president of the United States from 1974 to 1977. He was the only president never to have been elected ...

lost that year's presidential election

A presidential election is the election of any head of state whose official title is President.

Elections by country

Albania

The president of Albania is elected by the Assembly of Albania who are elected by the Albanian public.

Chile

The pre ...

to Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he previously served as th ...

. A session including Kissinger, Smith and Vorster then began, and here Smith relayed his concern that his acceptance could be perceived by the Rhodesian electorate as "selling out" and could cause a mass exodus of skilled workers and investment, which would in turn severely damage the country's economy. Vorster requested a break in the session and took Smith's team into a private side-room, accompanied by South African Foreign Minister Hilgard Muller

Hilgard Muller, (4 May 1914 – 10 July 1985) was a South African politician of the National Party, Mayor of Pretoria in 1953–1955, elected an MP in 1958, appointed Minister of Foreign Affairs after the resignation of Eric Louw i ...

. There he privately informed Smith that it was no longer viable for South Africa to support Rhodesia financially and militarily, and that Smith should make up his mind quickly and announce his acceptance that evening. This ultimatum deeply shocked the Rhodesian team; two of Smith's ministers, Desmond Lardner-Burke

Desmond William Lardner-Burke ID (17 October 1909 – 1984) was a politician in Rhodesia.

Early years

Desmond Lardner-Burke was born in Kimberley in the Cape of Good Hope on 17 October 1909, and was educated at St. Andrew's College, Grahamsto ...

and Jack Mussett

Jack may refer to:

Places

* Jack, Alabama, US, an unincorporated community

* Jack, Missouri, US, an unincorporated community

* Jack County, Texas, a county in Texas, USA

People and fictional characters

* Jack (given name), a male given name, ...

, were unable to contain their anger and vociferously berated the South African prime minister for his "irresponsibility", leading Vorster to rise from his seat without a word and leave the room.

The Rhodesians were then summoned back out into the main lounge, where Kissinger insisted that their prime minister sit next to him. "Ian Smith made accepting the deal worse by acting like a gentleman," Kissinger later said. Vorster opened the discussion by announcing that he had applied no pressure to the Rhodesian delegates, which caused further consternation amongst the Rhodesians which they had difficulty suppressing. It was agreed that the Rhodesians should return to Salisbury

Salisbury ( ) is a cathedral city in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers Avon, Nadder and Bourne. The city is approximately from Southampton and from Bath.

Salisbury is in the southeast of Wil ...

and consult their cabinet, then announce their answer. Despite expressing "incredulity" at what had happened in Pretoria, and showing deep reluctance, the politicians in Salisbury resolved that despite what they perceived as "South African treachery" the responsible course of action could only be to go on with the peace process, and that meant accepting Kissinger's terms, which they agreed were better than any they could get in the future should they refuse. Smith announced his government's answer on the evening of 24 September 1976: "Yes." South Africa's wavering financial and military assistance suddenly became available again, but the Frontline States then abruptly changed tack and turned the Kissinger terms down, saying that any interim period before majority rule was unacceptable. A new constitutional conference in Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

, Switzerland, was hastily organised by Britain to try to salvage something from the wreckage, with 20 October 1976 set as the start date.

Geneva Conference

ZANU and ZAPU announced on 9 October that they would attend this conference and any thereafter as a joint "Patriotic Front" (PF), including members of both parties under a combined leadership. Kaunda and Nyerere welcomed the new negotiations, but with the Soviet Union proposing that they once again alter their line, the talks were delayed indefinitely. In an attempt to encourage the other parties to travel to Switzerland, British mediatorIvor Richard

Ivor Seward Richard, Baron Richard, (30 May 1932 – 18 March 2018) was a British Labour politician who served as a member of Parliament (MP) from 1964 until 1974. He was also a member of the European Commission and latterly sat as a life pee ...

asked the Rhodesian delegation to hasten their arrival, which they did, leaving Salisbury on 20 October 1976. Richard himself did not arrive until two days later. Some of the guerrillas arriving for the conference from the heat of Mozambique were unprepared for the Swiss winter: Rex Nhongo

Solomon Mujuru (born Solomon Tapfumaneyi Mutusva; 5 May 1945 – 15 August 2011), also known by his nom-de-guerre, Rex Nhongo, was a Zimbabwean military officer and politician who led Robert Mugabe's guerrilla forces during the Rhodesian Bush Wa ...

, for example, felt so cold that he turned every heating appliance in his room, including the stove, to maximum and went to sleep. When the room caught fire, he was forced to jump from the balcony in his pyjamas.

Even arranging the conference proved a struggle, with the Rhodesians taking exception to being served cards of admittance on 27 October denoting them "The Smith Delegation", rather than the "Rhodesian Government Delegation" as had happened in previous conferences and correspondence. The Rhodesians unilaterally altered their cards to this effect, then confronted Richard with them, causing him some shock. The conference was eventually arranged to commence on 28 October at 15:00, but at very short notice the British mediator delayed the start for two hours; some Patriotic Front delegates were questioning his role as chairman and threatening not to attend, and Richard hoped to talk them around in the extra time. When the parties finally met, some hours later than planned, Muzorewa sat opposite Smith as the leader of the nationalist delegates, as at Victoria Falls, but with empty seats directly either side of him, marked "Comrade Enos Nkala

Enos Mzombi Nkala (23 August 1932 – 21 August 2013) was one of the founders of the Zimbabwe African National Union.

Political career Role in ZANU-PF

During the Rhodesian Bush War, he served on the ZANU high command, or Dare reChimurenga as Tr ...

" and "Comrade Edson Sithole Edson Furatidzayi Chisingaitwi Sithole (5 June 1935 - 15 October 1975) was the second black African to be admitted to the Rhodesian Bar in 1963 after Herbert Chitepo. He received his LLB from the University of London through correspondence. Subsequ ...

" respectively—each of these ZANU cadres had refused to attend the opening meeting despite Richard's entreaties. The mediator read an opening statement from British prime minister James Callaghan

Leonard James Callaghan, Baron Callaghan of Cardiff, ( ; 27 March 191226 March 2005), commonly known as Jim Callaghan, was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1976 to 1979 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1976 to 1980. Callaghan is ...

which, to the nationalists' delight and the government's chagrin, referred to the country as "Zimbabwe". The proceedings were then adjourned, to start again the next day.

On the morning of 29 October, Mugabe and Nkomo spoke in turn, giving emotionally charged speeches about the "dreadful sacrifices which the white governments have exacted from the poor black people". Neither made any comment relevant to a new constitution. Muzorewa then told the story of the life of the Ndebele King Lobengula

Lobengula Khumalo (c. 1845 – presumed January 1894) was the second and last official king of the Northern Ndebele people (historically called Matabele in English). Both names in the Ndebele language mean "the men of the long shields", a refere ...

in reverent tones, before Sithole made the only directly relevant nationalist contribution of the day, saying simply that he hoped the two sides could come to an agreement. A few days' break were then agreed as constitutional lawyers drew up a plan based on Kissinger's for the delegates to discuss. The American election result came through on the morning of 2 November 1976; as expected, Carter had won. In Geneva, meanwhile, it soon became clear that while the Rhodesians wished to stick to the plan they had agreed with Kissinger, the nationalists had no intention of doing so, regarding those terms only as a starting point for further negotiation. They continually interrupted the lawyers' work with new demands, meaning that by 8 November practically no progress had been made.

A meeting was organised for the next day, 9 November: the chaotic parley led nowhere, with the nationalists once again taking turns to make long, irrelevant speeches while the Rhodesians attempted to have Richard return the subject to the new constitution. Smith, who had earlier supported Richard as mediator in the face of the nationalists' criticism, became very frustrated by Richard's refusal to be firm with the PF and restore order to the proceedings. Unproductive discussions continued for another month, with Mugabe persistently arriving late to the meetings. When Rhodesian minister P K van der Byl confronted Mugabe about his tardiness and tersely demanded an apology, the ZANU leader became enraged and screamed, "Foul-mouthed bloody fool!"

Abandonment

Finally, on 14 December 1976, British Foreign MinisterAnthony Crosland

Charles Anthony Raven Crosland (29 August 191819 February 1977) was a British Labour Party politician and author. A social democrat on the right wing of the Labour Party, he was a prominent socialist intellectual. His influential book ''The ...

announced that the conference was to be adjourned. It was never reconvened—the Patriotic Front now said that it would not return to Geneva or take part in any further talks unless immediate black rule was made the only subject for discussion. Apparently believing that the British and Rhodesians were secretly working together to prevent this, Nkomo laid down pre-conditions for any new conference. "The Rhodesian situation is a war situation ... On our side it is the Patriotic Front, and on the British ... side it is the British government with the Rhodesian régime as tsextension. ... The agenda must have only one item ... the transfer of power from the minority to the majority. This means a constitution based on universal adult suffrage. ... This item should take four to five days."

Notes and references

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * {{Rhodesia topics 1976 conferences 1976 in international relations 1976 in Switzerland 1976 in Rhodesia 20th-century diplomatic conferences Diplomatic conferences in Switzerland Foreign relations of Rhodesia History of Rhodesia ZANU–PF Rhodesian Bush War