Genetic Engineering In Science Fiction on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Aspects of

Aspects of

Modern genetics began with the work of the monk

Modern genetics began with the work of the monk

Aspects of

Aspects of genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar wor ...

including mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, mi ...

, hybridisation, cloning

Cloning is the process of producing individual organisms with identical or virtually identical DNA, either by natural or artificial means. In nature, some organisms produce clones through asexual reproduction. In the field of biotechnology, cl ...

, genetic engineering

Genetic engineering, also called genetic modification or genetic manipulation, is the modification and manipulation of an organism's genes using technology. It is a set of technologies used to change the genetic makeup of cells, including t ...

, and eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or ...

have appeared in fiction since the 19th century.

Genetics is a young science, having started in 1900 with the rediscovery of Gregor Mendel

Gregor Johann Mendel, Augustinians, OSA (; cs, Řehoř Jan Mendel; 20 July 1822 – 6 January 1884) was a biologist, meteorologist, mathematician, Augustinians, Augustinian friar and abbot of St Thomas's Abbey, Brno, St. Thomas' Abbey in Br� ...

's study on the inheritance of traits in pea plants. During the 20th century it developed to create new sciences and technologies including molecular biology

Molecular biology is the branch of biology that seeks to understand the molecular basis of biological activity in and between cells, including biomolecular synthesis, modification, mechanisms, and interactions. The study of chemical and physi ...

, DNA sequencing

DNA sequencing is the process of determining the nucleic acid sequence – the order of nucleotides in DNA. It includes any method or technology that is used to determine the order of the four bases: adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine. Th ...

, cloning, and genetic engineering. The ethical implications were brought into focus with the eugenics movement.

Since then, many science fiction

Science fiction (sometimes shortened to Sci-Fi or SF) is a genre of speculative fiction which typically deals with imaginative and futuristic concepts such as advanced science and technology, space exploration, time travel, parallel unive ...

novels and films have used aspects of genetics as plot devices, often taking one of two routes: a genetic accident with disastrous consequences; or, the feasibility and desirability of a planned genetic alteration. The treatment of science in these stories has been uneven and often unrealistic. The film ''Gattaca

''Gattaca'' is a 1997 American dystopian science fiction thriller film written and directed by Andrew Niccol in his filmmaking debut. It stars Ethan Hawke and Uma Thurman with Jude Law, Loren Dean, Ernest Borgnine, Gore Vidal, and Alan Arkin ap ...

'' did attempt to portray science accurately but was criticised by scientists.

Background

Gregor Mendel

Gregor Johann Mendel, Augustinians, OSA (; cs, Řehoř Jan Mendel; 20 July 1822 – 6 January 1884) was a biologist, meteorologist, mathematician, Augustinians, Augustinian friar and abbot of St Thomas's Abbey, Brno, St. Thomas' Abbey in Br� ...

in the 19th century, on the inheritance of traits in pea plants. Mendel found that visible traits, such as whether peas were round or wrinkled, were inherited discretely, rather than by blending the attributes of the two parents. In 1900, Hugo de Vries

Hugo Marie de Vries () (16 February 1848 – 21 May 1935) was a Dutch botanist and one of the first geneticists. He is known chiefly for suggesting the concept of genes, rediscovering the laws of heredity in the 1890s while apparently unaware of ...

and other scientists rediscovered Mendel's research; William Bateson

William Bateson (8 August 1861 – 8 February 1926) was an English biologist who was the first person to use the term genetics to describe the study of heredity, and the chief populariser of the ideas of Gregor Mendel following their rediscove ...

coined the term "genetics" for the new science, which soon investigated a wide range of phenomena including mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, mi ...

(inherited changes caused by damage to the genetic material), genetic linkage

Genetic linkage is the tendency of DNA sequences that are close together on a chromosome to be inherited together during the meiosis phase of sexual reproduction. Two genetic markers that are physically near to each other are unlikely to be separ ...

(when some traits are to some extent inherited together), and hybridisation (crosses of different species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

).

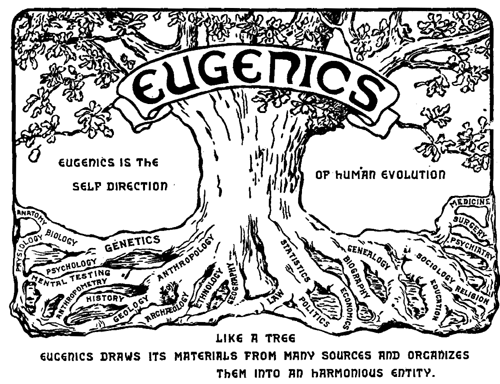

Eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or ...

, the production of better human beings by selective breeding, was named and advocated by Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

's cousin, the scientist Francis Galton

Sir Francis Galton, FRS FRAI (; 16 February 1822 – 17 January 1911), was an English Victorian era polymath: a statistician, sociologist, psychologist, anthropologist, tropical explorer, geographer, inventor, meteorologist, proto- ...

, in 1883. It had both a positive aspect, the breeding of more children with high intelligence and good health; and a negative aspect, aiming to suppress "race degeneration" by preventing supposedly "defective" families with attributes such as profligacy, laziness, immoral behaviour and a tendency to criminality from having children.

Molecular biology

Molecular biology is the branch of biology that seeks to understand the molecular basis of biological activity in and between cells, including biomolecular synthesis, modification, mechanisms, and interactions. The study of chemical and physi ...

, the interactions and regulation

Regulation is the management of complex systems according to a set of rules and trends. In systems theory, these types of rules exist in various fields of biology and society, but the term has slightly different meanings according to context. For ...

of genetic materials, began with the identification in 1944 of DNA as the main genetic material; Reprint: the genetic code

The genetic code is the set of rules used by living cells to translate information encoded within genetic material ( DNA or RNA sequences of nucleotide triplets, or codons) into proteins. Translation is accomplished by the ribosome, which links ...

and the double helix

A double is a look-alike or doppelgänger; one person or being that resembles another.

Double, The Double or Dubble may also refer to:

Film and television

* Double (filmmaking), someone who substitutes for the credited actor of a character

* ...

structure of DNA was determined by James Watson

James Dewey Watson (born April 6, 1928) is an American molecular biologist, geneticist, and zoologist. In 1953, he co-authored with Francis Crick the academic paper proposing the double helix structure of the DNA molecule. Watson, Crick and ...

and Francis Crick

Francis Harry Compton Crick (8 June 1916 – 28 July 2004) was an English molecular biologist, biophysicist, and neuroscientist. He, James Watson, Rosalind Franklin, and Maurice Wilkins played crucial roles in deciphering the helical struc ...

in 1953. DNA sequencing

DNA sequencing is the process of determining the nucleic acid sequence – the order of nucleotides in DNA. It includes any method or technology that is used to determine the order of the four bases: adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine. Th ...

, the identification of an exact sequence of genetic information in an organism, was developed in 1977 by Frederick Sanger

Frederick Sanger (; 13 August 1918 – 19 November 2013) was an English biochemist who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry twice.

He won the 1958 Chemistry Prize for determining the amino acid sequence of insulin and numerous other p ...

.

Genetic engineering

Genetic engineering, also called genetic modification or genetic manipulation, is the modification and manipulation of an organism's genes using technology. It is a set of technologies used to change the genetic makeup of cells, including t ...

, the modification of the genetic material of a live organism, became possible in 1972 when Paul Berg

Paul Berg (born June 30, 1926) is an American biochemist and professor emeritus at Stanford University. He was the recipient of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1980, along with Walter Gilbert and Frederick Sanger. The award recognized their con ...

created the first recombinant DNA

Recombinant DNA (rDNA) molecules are DNA molecules formed by laboratory methods of genetic recombination (such as molecular cloning) that bring together genetic material from multiple sources, creating sequences that would not otherwise be foun ...

molecules (artificially assembled genetic material) using virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1 ...

es.

Cloning

Cloning is the process of producing individual organisms with identical or virtually identical DNA, either by natural or artificial means. In nature, some organisms produce clones through asexual reproduction. In the field of biotechnology, cl ...

, the production of genetically identical organisms from some chosen starting point, was shown to be practicable in a mammal with the creation of Dolly the sheep

Dolly (5 July 1996 – 14 February 2003) was a female Finnish Dorset sheep and the first mammal cloned from an adult somatic cell. She was cloned by associates of the Roslin Institute in Scotland, using the process of nuclear transfer from a ...

from an ordinary body cell in 1996 at the Roslin Institute

The Roslin Institute is an animal sciences research institute at Easter Bush, Midlothian, Scotland, part of the University of Edinburgh, and is funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council.

It is best known for creati ...

.

Genetics themes

Mutants and hybrids

Mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, mi ...

and hybridisation are widely used in fiction, starting in the 19th century with science fiction

Science fiction (sometimes shortened to Sci-Fi or SF) is a genre of speculative fiction which typically deals with imaginative and futuristic concepts such as advanced science and technology, space exploration, time travel, parallel unive ...

works such as Mary Shelley's 1818 novel ''Frankenstein

''Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus'' is an 1818 novel written by English author Mary Shelley. ''Frankenstein'' tells the story of Victor Frankenstein, a young scientist who creates a sapient creature in an unorthodox scientific ex ...

'' and H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells"Wells, H. G."

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

The Island of Dr Moreau

''The Island of Doctor Moreau'' is an 1896 science fiction novel by English author H. G. Wells (1866–1946). The text of the novel is the narration of Edward Prendick who is a shipwrecked man rescued by a passing boat. He is left on the island ...

''.

In her 1977 ''Biological Themes in Modern Science Fiction'', Helen Parker identified two major types of story: "genetic accident", the uncontrolled, unexpected and disastrous alteration of a species; and "planned genetic alteration", whether controlled by humans or aliens

Alien primarily refers to:

* Alien (law), a person in a country who is not a national of that country

** Enemy alien, the above in times of war

* Extraterrestrial life, life which does not originate from Earth

** Specifically, intelligent extrate ...

, and the question of whether that would be either feasible or desirable. In science fiction up to the 1970s, the genetic changes were brought about by radiation

In physics, radiation is the emission or transmission of energy in the form of waves or particles through space or through a material medium. This includes:

* ''electromagnetic radiation'', such as radio waves, microwaves, infrared, visi ...

, breeding programmes, or manipulation with chemicals or surgery

Surgery ''cheirourgikē'' (composed of χείρ, "hand", and ἔργον, "work"), via la, chirurgiae, meaning "hand work". is a medical specialty that uses operative manual and instrumental techniques on a person to investigate or treat a pat ...

(and thus, notes Lars Schmeink, not necessarily by strictly genetic means). Examples include ''The Island of Dr Moreau'' with its horrible manipulations; Aldous Huxley

Aldous Leonard Huxley (26 July 1894 – 22 November 1963) was an English writer and philosopher. He wrote nearly 50 books, both novels and non-fiction works, as well as wide-ranging essays, narratives, and poems.

Born into the prominent Huxley ...

's 1932 ''Brave New World

''Brave New World'' is a dystopian novel by English author Aldous Huxley, written in 1931 and published in 1932. Largely set in a futuristic World State, whose citizens are environmentally engineered into an intelligence-based social hierarch ...

'' with a breeding programme; and John Taine

Eric Temple Bell (7 February 1883 – 21 December 1960) was a Scottish-born mathematician and science fiction writer who lived in the United States for most of his life. He published non-fiction using his given name and fiction as John Tai ...

's 1951 ''Seeds of Life

''Seeds of Life'' is a science fiction novel by American writer John Taine (pseudonym of Eric Temple Bell). It was first published in 1951 by Fantasy Press in an edition of 2,991 copies. The novel originally appeared in the magazine ''Amazing St ...

'', using radiation to create supermen. After the discovery of the double helix and then recombinant DNA, genetic engineering became the focus for genetics in fiction, as in books like Brian Stableford

Brian Michael Stableford (born 25 July 1948) is a British academic, critic and science fiction writer who has published more than 70 novels. His earlier books were published under the name Brian M. Stableford, but more recent ones have dropped ...

's tale of a genetically modified society in his 1998 ''Inherit the Earth'', or Michael Marshall Smith

Michael Paul Marshall Smith (born 3 May 1965) is an English novelist, screenwriter and short story writer who also writes as Michael Marshall, M. M. Smith and Michael Rutger.

Biography

Born in Knutsford, Cheshire, Smith moved with his family a ...

's story of organ farming in his 1997 ''Spares''.

Comic books

A comic book, also called comicbook, comic magazine or (in the United Kingdom and Ireland) simply comic, is a publication that consists of comics art in the form of sequential juxtaposed panels that represent individual scenes. Panels are of ...

have imagined mutated superhumans

The term superhuman refers to humans or human-like beings with enhanced qualities and abilities that exceed those naturally found in humans. These qualities may be acquired through natural ability, self-actualization or technological aids. Th ...

with extraordinary powers. The DC Universe

The DC Universe (DCU) is the fictional shared universe where most stories in American comic book titles published by DC Comics take place. Superheroes such as Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, Robin, Martian Manhunter, The Flash, Green Lant ...

(from 1939) imagines "metahuman

In DC Comics' DC Universe, a metahuman is a human with superpowers. The term is roughly synonymous with both ''mutant'' and ''mutate'' in the Marvel Universe and '' posthuman'' in the Wildstorm and Ultimate Marvel Universes. In DC Comics, the term ...

s"; the Marvel Universe

The Marvel Universe is a fictional shared universe where the stories in most American comic book titles and other media published by Marvel Comics take place. Super-teams such as the Avengers, the X-Men, the Fantastic Four, the Guardians of ...

(from 1961) calls them "mutants

In biology, and especially in genetics, a mutant is an organism or a new genetic character arising or resulting from an instance of mutation, which is generally an alteration of the DNA sequence of the genome or chromosome of an organism. It ...

", while the Wildstorm

Wildstorm Productions, (stylized as WildStorm), is an American comic book imprint. Originally founded as an independent company established by Jim Lee under the name "Aegis Entertainment" and expanded in subsequent years by other creators, Wilds ...

(from 1992) and Ultimate Marvel

Ultimate Marvel, later known as Ultimate Comics, was an imprint of comic books published by Marvel Comics, featuring re-imagined and modernized versions of the company's superhero characters from the Ultimate Marvel Universe. Those characters in ...

(2000–2015) Universes name them "posthuman

Posthuman or post-human is a concept originating in the fields of science fiction, futurology, contemporary art, and philosophy that means a person or entity that exists in a state beyond being human. The concept aims at addressing a variety of ...

s".

Stan Lee introduced the concept of mutants in the Marvel X-Men books in 1963; the villain Magneto declares his plan to "make ''Homo sapiens

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, ...

'' bow to ''Homo superior''!", implying that mutants will be an evolutionary step up from current humanity. Later, the books speak of an X-gene that confers powers from puberty

Puberty is the process of physical changes through which a child's body matures into an adult body capable of sexual reproduction. It is initiated by hormonal signals from the brain to the gonads: the ovaries in a girl, the testes in a boy. ...

onwards. X-men powers include telepathy

Telepathy () is the purported vicarious transmission of information from one person's mind to another's without using any known human sensory channels or physical interaction. The term was first coined in 1882 by the classical scholar Frederic W ...

, telekinesis

Psychokinesis (from grc, ψυχή, , soul and grc, κίνησις, , movement, label=ㅤ), or telekinesis (from grc, τηλε, , far off and grc, κίνησις, , movement, label=ㅤ), is a hypothetical psychic ability allowing a person ...

, healing, strength, flight, time travel

Time travel is the concept of movement between certain points in time, analogous to movement between different points in space by an object or a person, typically with the use of a hypothetical device known as a time machine. Time travel is a w ...

, and the ability to emit blasts of energy. Marvel's god-like Celestials are later (1999) said to have visited Earth long ago and to have modified human DNA to enable mutant powers.

James Blish

James Benjamin Blish () was an American science fiction and fantasy writer. He is best known for his ''Cities in Flight'' novels and his series of ''Star Trek'' novelizations written with his wife, J. A. Lawrence. His novel ''A Case of Conscienc ...

's 1952 novel ''Titan's Daughter'' (in Kendell Foster Crossen

Kendell Foster Crossen (July 25, 1910 – November 29, 1981) was an American pulp fiction and science fiction writer. He was the creator and writer of stories about the Green Lama (a pulp and comic book hero) and the Milo March detective and spy ...

's ''Future Tense'' collection) featured stimulated polyploidy

Polyploidy is a condition in which the cells of an organism have more than one pair of ( homologous) chromosomes. Most species whose cells have nuclei ( eukaryotes) are diploid, meaning they have two sets of chromosomes, where each set contain ...

(giving organisms multiple sets of genetic material, something that can create new species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

in a single step), based on spontaneous polyploidy in flowering plant

Flowering plants are plants that bear flowers and fruits, and form the clade Angiospermae (), commonly called angiosperms. The term "angiosperm" is derived from the Greek words ('container, vessel') and ('seed'), and refers to those plants th ...

s, to create humans with more than normal height, strength, and lifespans.

Cloning

Cloning

Cloning is the process of producing individual organisms with identical or virtually identical DNA, either by natural or artificial means. In nature, some organisms produce clones through asexual reproduction. In the field of biotechnology, cl ...

, too, is a familiar plot device. Aldous Huxley

Aldous Leonard Huxley (26 July 1894 – 22 November 1963) was an English writer and philosopher. He wrote nearly 50 books, both novels and non-fiction works, as well as wide-ranging essays, narratives, and poems.

Born into the prominent Huxley ...

's 1931 dystopian novel ''Brave New World

''Brave New World'' is a dystopian novel by English author Aldous Huxley, written in 1931 and published in 1932. Largely set in a futuristic World State, whose citizens are environmentally engineered into an intelligence-based social hierarch ...

'' imagines the ''in vitro

''In vitro'' (meaning in glass, or ''in the glass'') studies are performed with microorganisms, cells, or biological molecules outside their normal biological context. Colloquially called "test-tube experiments", these studies in biology an ...

'' cloning of fertilised human Egg (biology), eggs. Huxley was influenced by J. B. S. Haldane's 1924 non-fiction book ''Daedalus; or, Science and the Future'', which used the Greek myth of Daedalus to symbolise the coming revolution in genetics; Haldane predicted that humans would Directed evolution (transhumanism), control their own evolution through directed mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, mi ...

and in vitro fertilisation. Cloning was explored further in stories such as Poul Anderson's 1953 ''UN-Man''. In his 1976 novel, The Boys from Brazil (novel), The Boys from Brazil, Ira Levin describes the creation of 96 clones of Adolf Hitler, replicating for all of them the rearing of Hitler (including the death of his father at age 13), with the goal of resurrecting Nazism. In his 1990 novel ''Jurassic Park (novel), Jurassic Park'', Michael Crichton imagined the recovery of the complete genome of a dinosaur from fossil remains, followed by its use to recreate living animals of an extinct species.

Cloning is a recurring theme in science fiction films like ''Jurassic Park'' (1993), ''Alien Resurrection'' (1997), ''The 6th Day'' (2000), ''Resident Evil (film), Resident Evil'' (2002), ''Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones, Star Wars: Episode II'' (2002) and ''The Island (2005 film), The Island'' (2005). The process of cloning is represented variously in fiction. Many works depict the artificial creation of humans by a method of growing cells from a tissue or DNA sample; the replication may be instantaneous, or take place through slow growth of human embryos in artificial wombs. In the long-running British television series ''Doctor Who'', the Fourth Doctor and his companion Leela (Doctor Who), Leela were cloned in a matter of seconds from DNA samples ("The Invisible Enemy (Doctor Who), The Invisible Enemy", 1977) and then—in an apparent Homage (arts), homage to the 1966 film ''Fantastic Voyage''—shrunk to microscopic size in order to enter the Doctor's body to combat an alien virus. The clones in this story are short-lived, and can only survive a matter of minutes before they expire. Films such as ''The Matrix'' and ''Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones'' have featured human foetuses being cultured on an industrial scale in enormous tanks.

Cloning humans from body parts is a common science fiction trope, one of several genetics themes parodied in Woody Allen's 1973 comedy ''Sleeper (1973 film), Sleeper'', where an attempt is made to clone an assassinated dictator from his disembodied nose.

Genetic engineering

Genetic engineering

Genetic engineering, also called genetic modification or genetic manipulation, is the modification and manipulation of an organism's genes using technology. It is a set of technologies used to change the genetic makeup of cells, including t ...

features in many science fiction stories. Films such as The Island (2005 film), ''The Island'' (2005) and ''Blade Runner'' (1982) bring the engineered creature to confront the person who created it or the being it was cloned from, a theme seen in some film versions of ''Frankenstein''. Few films have informed audiences about genetic engineering as such, with the exception of the 1978 ''The Boys from Brazil (film), The Boys from Brazil'' and the 1993 ''Jurassic Park (film), Jurassic Park'', both of which made use of a lesson, a demonstration, and a clip of scientific film. In 1982, Frank Herbert's novel ''The White Plague'' described the deliberate use of genetic engineering to create a pathogen which specifically killed women. Another of Herbert's creations, the ''Dune (franchise), Dune'' series of novels, starting with ''Dune (novel), Dune'' in 1965, emphasises genetics. It combines selective breeding by a powerful sisterhood, the Bene Gesserit, to produce a supernormal male being, the Kwisatz Haderach, with the genetic engineering of the powerful but despised Tleilaxu.

Genetic engineering methods are weakly represented in film; Michael Clark, writing for The Wellcome Trust, calls the portrayal of genetic engineering and biotechnology "seriously distorted" in films such as Roger Spottiswoode's 2000 ''The 6th Day'', which makes use of the trope of a "vast clandestine laboratory ... filled with row upon row of 'blank' human bodies kept floating in tanks of nutrient liquid or in suspended animation". In Clark's view, the biotechnology is typically "given fantastic but visually arresting forms" while the science is either relegated to the background or fictionalised to suit a young audience.

Eugenics

Eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or ...

plays a central role in films such as Andrew Niccol's 1997 ''Gattaca

''Gattaca'' is a 1997 American dystopian science fiction thriller film written and directed by Andrew Niccol in his filmmaking debut. It stars Ethan Hawke and Uma Thurman with Jude Law, Loren Dean, Ernest Borgnine, Gore Vidal, and Alan Arkin ap ...

'', the title alluding to the letters G, A, T, C for guanine, adenine, thymine, and cytosine, the four nucleobases of DNA. Genetic engineering of humans is unrestricted, resulting in genetic discrimination, loss of diversity, and adverse effects on society. The film explores the Bioethics, ethical implications; the production company, Sony Pictures, consulted with a gene therapy researcher, William French Anderson, French Anderson, to ensure that the portrayal of science was realistic, and test-screened the film with the Society of Mammalian Cell Biologists and the American National Human Genome Research Institute before its release. This care did not prevent researchers from attacking the film after its release. Philim Yam of ''Scientific American'' called it "science bashing"; in ''Nature (journal), Nature'' Kevin Davies called it a ""surprisingly pedestrian affair"; and the Molecular biology, molecular biologist Lee M. Silver, Lee Silver described the film's extreme genetic determinism as "a straw man".

Myth and oversimplification

The geneticist Dan Koboldt observes that while science and technology play major roles in fiction, from fantasy and science fiction to thriller (genre), thrillers, the representation of science in both literature and film is often unrealistic. In Koboldt's view, genetics in fiction is frequently oversimplified, and some myths are common and need to be debunked. For example, the Human Genome Project has not (he states) immediately led to a ''Gattaca'' world, as the relationship between genotype and phenotype is not straightforward. People do differ genetically, but only very rarely because they are missing a gene that other people have: people have different alleles of the same genes. Eye and hair colour are controlled not by one gene each, but by multiple genes. Mutations do occur, but they are rare: people are 99.99% identical genetically, the 3 million differences between any two people being dwarfed by the hundreds of millions of DNA bases which are identical; nearly all DNA variants are inherited, not acquired afresh by mutation. And, Koboldt writes, believable scientists in fiction should know their knowledge is limited.See also

* Evolution in fiction * :Genetic engineering in fiction * Parasites in fictionReferences

{{Biology in fiction Genetics Science in fiction by theme Cloning in fiction