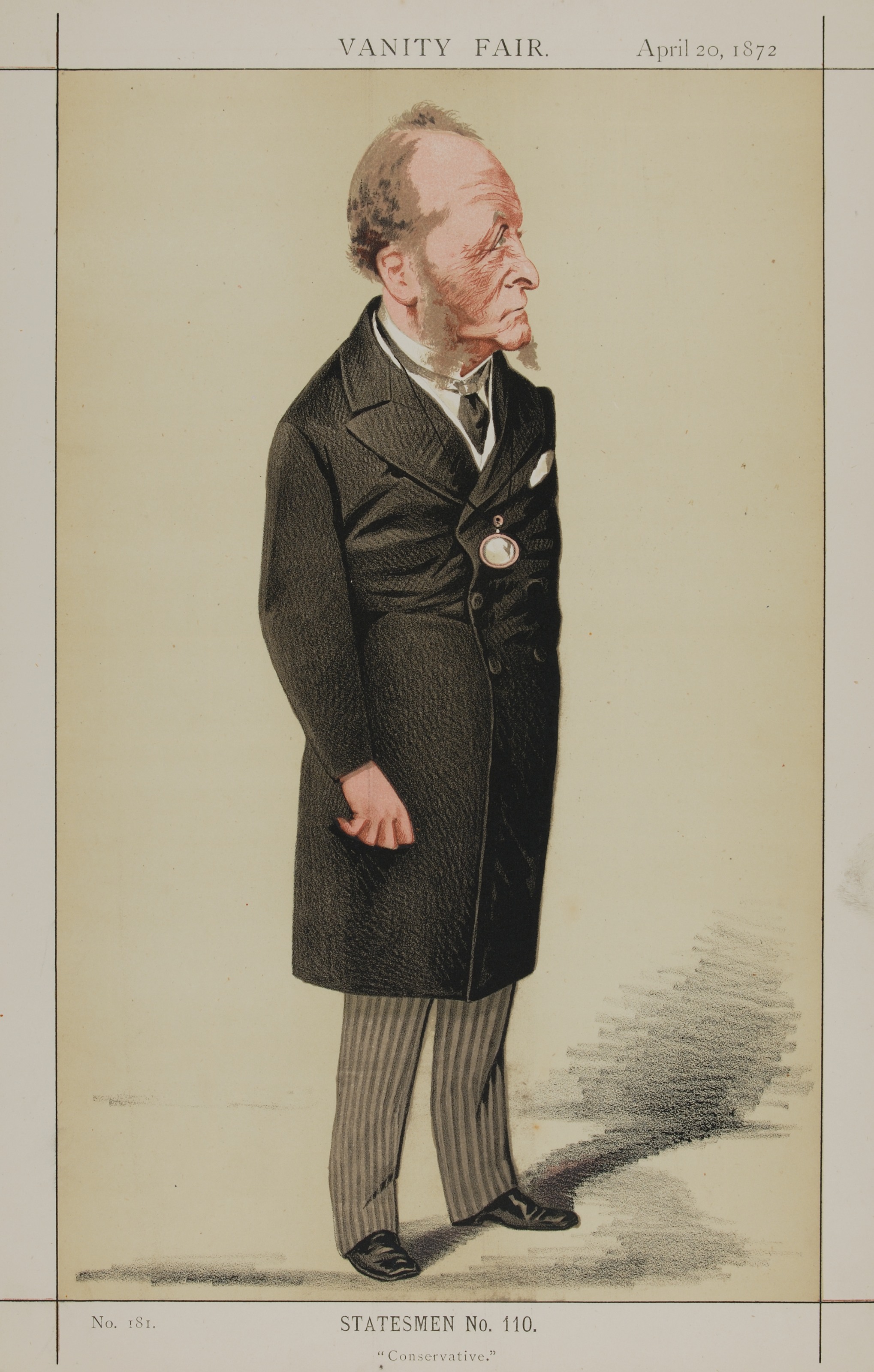

Gathorne Gathorne-Hardy, 1st Earl of Cranbrook on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Gathorne Gathorne-Hardy, 1st Earl of Cranbrook, (born Gathorne Hardy; 1 October 1814 – 30 October 1906) was a prominent British statesman, Conservative politician and key ally of Benjamin Disraeli. He held cabinet office in every Conservative government between 1858 and 1892 and notably served as

Gathorne Gathorne-Hardy, 1st Earl of Cranbrook, (born Gathorne Hardy; 1 October 1814 – 30 October 1906) was a prominent British statesman, Conservative politician and key ally of Benjamin Disraeli. He held cabinet office in every Conservative government between 1858 and 1892 and notably served as

Gathorne Hardy was the third son of John Hardy, of the Manor House Bradford, and Isabel, daughter of Richard Gathorne. His father was a barrister, the main owner of the

Gathorne Hardy was the third son of John Hardy, of the Manor House Bradford, and Isabel, daughter of Richard Gathorne. His father was a barrister, the main owner of the

Hardy had unsuccessfully contested Bradford in the 1847 general election. However, after his father's death in 1855 he was able to concentrate fully on a political career, and in 1856 he was elected for

Hardy had unsuccessfully contested Bradford in the 1847 general election. However, after his father's death in 1855 he was able to concentrate fully on a political career, and in 1856 he was elected for

In 1874 the Conservatives returned to office under Disraeli, and Hardy was appointed

In 1874 the Conservatives returned to office under Disraeli, and Hardy was appointed

Gathorne Gathorne-Hardy, 1st Earl of Cranbrook, (born Gathorne Hardy; 1 October 1814 – 30 October 1906) was a prominent British statesman, Conservative politician and key ally of Benjamin Disraeli. He held cabinet office in every Conservative government between 1858 and 1892 and notably served as

Gathorne Gathorne-Hardy, 1st Earl of Cranbrook, (born Gathorne Hardy; 1 October 1814 – 30 October 1906) was a prominent British statesman, Conservative politician and key ally of Benjamin Disraeli. He held cabinet office in every Conservative government between 1858 and 1892 and notably served as Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national ...

from 1867 to 1868 and as Secretary of State for War

The Secretary of State for War, commonly called War Secretary, was a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, which existed from 1794 to 1801 and from 1854 to 1964. The Secretary of State for War headed the War Office and ...

from 1874 to 1878. Gathorne-Hardy oversaw the British declaration of war for the Second Anglo-Afghan War.

Background and education

Gathorne Hardy was the third son of John Hardy, of the Manor House Bradford, and Isabel, daughter of Richard Gathorne. His father was a barrister, the main owner of the

Gathorne Hardy was the third son of John Hardy, of the Manor House Bradford, and Isabel, daughter of Richard Gathorne. His father was a barrister, the main owner of the Low Moor ironworks

The Low Moor Ironworks was a wrought iron foundry established in 1791 in the village of Low Moor about south of Bradford in Yorkshire, England. The works were built to exploit the high-quality iron ore and low-sulphur coal found in the area. L ...

and also represented Bradford in Parliament; his ancestors had been attorneys and stewards to the Spencer-Stanhope family of Horsforth

Horsforth is a town and civil parish within the City of Leeds, in West Yorkshire, England, lying about five miles north-west of Leeds city centre. Historically a village within the West Riding of Yorkshire, it had a population of 18,895 at the ...

since the beginning of the 18th century. He was educated at Shrewsbury School

Shrewsbury School is a public school (English independent boarding school for pupils aged 13 –18) in Shrewsbury.

Founded in 1552 by Edward VI by Royal Charter, it was originally a boarding school for boys; girls have been admitted into th ...

and Oriel College, Oxford

Oriel College () is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in Oxford, England. Located in Oriel Square, the college has the distinction of being the oldest royal foundation in Oxford (a title formerly claimed by University College, ...

, and was called to the Bar, Inner Temple

The Honourable Society of the Inner Temple, commonly known as the Inner Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court and is a professional associations for barristers and judges. To be called to the Bar and practise as a barrister in England and W ...

, in 1840. He established a successful legal practice on the Northern Circuit, being based at Leeds, but was denied when he applied for silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from the ...

in 1855.

Early political career, 1847–1874

Hardy had unsuccessfully contested Bradford in the 1847 general election. However, after his father's death in 1855 he was able to concentrate fully on a political career, and in 1856 he was elected for

Hardy had unsuccessfully contested Bradford in the 1847 general election. However, after his father's death in 1855 he was able to concentrate fully on a political career, and in 1856 he was elected for Leominster

Leominster ( ) is a market town in Herefordshire, England, at the confluence of the River Lugg and its tributary the River Kenwater. The town is north of Hereford and south of Ludlow in Shropshire. With a population of 11,700, Leominster is t ...

. Only two years later, in 1858, he was appointed Under-Secretary of State for Home Affairs in the second administration of the Earl of Derby

Earl of Derby ( ) is a title in the Peerage of England. The title was first adopted by Robert de Ferrers, 1st Earl of Derby, under a creation of 1139. It continued with the Ferrers family until the 6th Earl forfeited his property toward the e ...

. He remained in this office until the government fell in June 1859.

In 1865 Hardy reluctantly agreed to stand against William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-con ...

in the Oxford University constituency. However, on 17 July 1865, he defeated Gladstone by a majority of 180, which greatly enhanced his standing within the Conservative party thanks to the influence of rural clergy voters, but still did not come first in the poll. Gladstone's response was "Dear Dream is dispelled. God's will be done." The Conservatives returned to office under Derby in 1866, and Hardy was appointed President of the Poor Law Board, with a seat in the cabinet. He was admitted to the Privy Council at the same time. During his tenure in this office he notably carried a poor law amendment bill through parliament. Cranbrook also supported the Reform Act of 1867

The Representation of the People Act 1867, 30 & 31 Vict. c. 102 (known as the Reform Act 1867 or the Second Reform Act) was a piece of British legislation that enfranchised part of the urban male working class in England and Wales for the first ...

, which significantly increased the size of the electorate to one in five. By May Disraeli had recognised Gathorne Hardy's value to the Conservatives as a rising star in the Commons, proving a capable debater, a resilient antagonist to Gladstone, and nobody's fool. In 1867 he succeeded Spencer Horatio Walpole as Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national ...

and was forced to deal with the Fenian Rising of that year. By accepting an amendment that all ratepayers should be enfranchised, Disraeli had created a new Victorian constitution, which surprisingly Hardy and others were prepared to accept. One new entrant in 1868, an admirer of Disraeli, the Radical, Sir Charles Dilke thought Hardy the most eloquent Englishman, whose talents were wasted in the Conservative Party. But Hardy himself, not so easily deceived, remained a stalwart Tory to the end.

The next year, Benjamin Disraeli succeeded Derby as Prime Minister, but the Conservative government resigned in autumn 1868, after both the Queen and Disraeli delayed dissolution to register a new electorate, which since 1865 had accepted postal votes. The Liberals came to power under Gladstone. In opposition, Hardy occasionally acted as opposition leader in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

when Disraeli was absent.

There was criticism of the Anglican Church in Ireland, which Liberals intended to disestablish in its entirety. A committed Anglican, Hardy opposed the measure on religious grounds:"I say that the Church of Ireland has made many converts; not, it may be, by violent controversial proceedings, but by a quiet influence which has affected the minds of those who have been around her clergy, and who have gradually become leavened by their sentiments".Being an orthodox Anglican he considered fragmentation of the church as contrariwise to Conservative principles. In the

"I have faith in the principles we are professing, and when I am told by the right hon. Gentleman the President of the Board of Trade, and by others who have spoken like him, that all thoughtful men are against the Irish Church, that for fifty years every Statesman has looked forward to some such consummation."He spoke manfully in the Irish Church bill debate on 23 March 1869, before Gladstone gave the government's winding-up in one of the greatest oratorical expositions during the second reading. Hardy linked the Irish church bill to the Fenian rising and resulting atrocities, vis-à-vis a Catholic church allegedly willing to sell benefices for money. Moreover, he directly attacked the Prime Minister's followers whom he accused of being "indebted to the Fenian movement for that tardy measure of justice. This shows the encouragement to disloyalty given by this measure." And in provoking the government he linked tendentiously Baron Plunket, the nationalist, to the Liberal Party: which no doubt they disowned. During debates on education Hardy produced eloquent and stinging rebukes that deflected time from Gladstone's Irish reform agenda. Hardy proved an able lieutenant in the Disraelian tradition, mocking Gladstone's bill's cumbersome progress through the Commons. Gladstone gradually became hotter and bothered by Cranbrook's adroit remarks. When he was likened to the Hyde Park riots of 1866, the Prime Minister "caused such an explosion of passion and temper." The defeat threatened Disraeli's party leadership, but despite being considered Hardy declined, whilst the great man was still 'looking over his shoulder'. On 1 February 1872, Hardy was present at the Burghley House Conference of Tory grandees: only Derby and Disraeli were missing for the discussion about the party's and country's future. Hosted by Lord Exeter, a Cecil descendant of the Elizabethan Lord Burghley, other Cabinet members were Sir Stafford Northcote, Sir John Pakington, Lord Cairns, and Lord John Manners, a personal friend of Disraeli. Only Manners and Northcote were prepared to support Disraeli's continued leadership. The group suggested that Lord Stanley, Derby's son, take the Commons post of party leader. For his part, the younger Stanley was a very different character than his father. Short and plump, Stanley was a reformer, open to change, and ideas around progressive politics. He was also more amenable to Disraeli, recognizing that he was unfit, he did not wish to displace a man whom backbenchers knew was the outstanding parliamentarian. Stanley's neutrality would convert other cabinet members towards acceptance of the flamboyant Jew. Latterly Hardy worked well with Disraeli, although they were not close intimates. At the end of the month the mood in London lifted: the Prince of Wales was out of trouble, and Hardy amongst others attended a service of thanksgiving and praise at St Paul's on 27 February.

Cabinet minister, 1874–1880

In 1874 the Conservatives returned to office under Disraeli, and Hardy was appointed

In 1874 the Conservatives returned to office under Disraeli, and Hardy was appointed Secretary of State for War

The Secretary of State for War, commonly called War Secretary, was a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, which existed from 1794 to 1801 and from 1854 to 1964. The Secretary of State for War headed the War Office and ...

, for which he was not best suited. He should have been offered the Home Office, but this went to a fine debater, Richard Cross. But the House rose on 7 August, leaving the minister the remainder of the year to settle into departmental work. Hardy stayed in post for more than four years overseeing the army reforms initiated by his Liberal predecessor Edward Cardwell. In 1876, Disraeli was elevated to the peerage, and the House of Lords, as Earl of Beaconsfield. Hardy had expected to become Conservative leader in the House of Commons, but was overlooked in favour of Sir Stafford Northcote; Disraeli disliked the fact Hardy neglected the house to go home in the evening to dine with his wife.

Two years later, in April 1878, Hardy succeeded The Marquess of Salisbury

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (; 3 February 183022 August 1903) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom three times for a total of over thirteen ...

as Secretary of State for India, and the following month he was raised to the peerage as Viscount Cranbrook, of Hemsted in the County of Kent. At the same time, he assumed his mother's maiden surname of Gathorne in addition to that of Hardy at the request of his family. In December 1878, Cranbrook attended court, and heard from the Queen her complaints about Gladstone's mishandling of the Prince of Wales' rejection of the proposal to make him Viceroy of Ireland. Cranbrook remained one of the ministers at the centre of the court being a monarchist, frequently interacting with the Queen and Prince of Wales. When Gladstone's portrait was shown in public, Cranbrook tactfully observed protocol.

The Eastern Question had posed the biggest single foreign policy dilemma in 1877. Hardy was in favour of actively pursuing the bankrupted Sultan with a loan, and going to war if necessary to keep Russia out of Constantinople. He proved one of Disraeli's closest allies in cabinet. Cranbrook was a relative ''parvenu''; the rich aristocrats wanted peace and so did Gladstone, at any price. But he was vindicated; when Salisbury swapped sides to support the PM, he was raised to Foreign Minister. A 'War Party', an Inner Cabinet, sent Royal Navy battleships to defend the Turks against a threatening Russian Army. At the India Office

The India Office was a British government department established in London in 1858 to oversee the administration, through a Viceroy and other officials, of the Provinces of India. These territories comprised most of the modern-day nations of ...

Cranbrook was forced to deal with the Second Afghan War

The Second Anglo-Afghan War (Dari: جنگ دوم افغان و انگلیس, ps, د افغان-انګرېز دويمه جګړه) was a military conflict fought between the British Raj and the Emirate of Afghanistan from 1878 to 1880, when the l ...

in 1878, aimed at restoring British influence in Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bord ...

. After a peaceful summer of 1878 deer-stalking in Scotland, Cranbrook returned to a crisis dealing with an ill-prepared Viceroy of India. A full invasion of Afghanistan was ordered on 21 November. The Afghans were defeated within weeks, but the new Third Empire had begun in a state of panic. A peace deal was struck in May 1879, but war again erupted after the British resident, Sir Louis Cavagnari, was murdered by mutinous Afghan troops. British troops under Frederick Roberts managed once again to restore control. However, the situation was still volatile when Cranbrook, along with the rest of the government, resigned in April 1880. As a peer Cranbrook was disqualified from making speeches during elections, which ended in a Liberal majority. He took a well-earned rest in Italy early in 1881, and was still there when the only one of Disraeli's cabinet absent for the Earl of Beaconsfield's funeral at Hughenden.

Tory grandee

Lord Cranbrook remained at the heart of the party elite. In 1884 a new Chief Whip, Aretas Akers-Douglas gained promotion from Salisbury partly through the austere influence of this knowledgeable and experienced grandee. In early 1885 the government was rent with division, Chamberlain refusing to agree with the franchise as 'ransom' of private property. Cranbrook wrote to Lord Cairns on 9 January, "all this comes from the Irish policy for wh. Mr Gladstone is responsible." The writing was on the wall for the government. In June 1885 the Conservatives returned to power as "Caretakers", and Cranbrook was made Lord President of the Council. Cranbrook was shocked to find out that behind the cabinet's back Lord Carnarvon had been negotiating a deal, known in the newspapers as 'Tory Parnellism', with the Irish Party. For two weeks in early 1886 he again served as Secretary of State for War. The government fell in January 1886 but soon returned to office in July of the same year after a General Election under a new franchise. Cranbrook was once again appointed Lord President of the council, in which office he was mainly concerned with education. He also served briefly asChancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

The chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster is a ministerial office in the Government of the United Kingdom. The position is the second highest ranking minister in the Cabinet Office, immediately after the Prime Minister, and senior to the Minist ...

in August 1886. He declined the post of Foreign Secretary

The secretary of state for foreign, Commonwealth and development affairs, known as the foreign secretary, is a minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom and head of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. Seen as ...

in 1886 owing to his inability to speak foreign languages, and also refused the viceroyalty of Ireland. Perhaps the stolid familiarity of the council was additionally welcome after the turmoil in government caused by Lord Randolph Churchill's erratic, argumentative behaviour. He remained as Lord President of the council until the second Salisbury ministry fell in 1892. Shortly after, he was further honoured when he was made Baron Medway, of Hemsted in the County of Kent, and Earl of Cranbrook, in the County of Kent. In opposition, Cranbrook was a strong opponent of the Second Home Rule Bill

The Government of Ireland Bill 1893 (known generally as the Second Home Rule Bill) was the second attempt made by Liberal Party leader William Ewart Gladstone, as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, to enact a system of home rule for Ireland. ...

, which was heavily defeated in the House of Lords. He retired from public life after the 1895 general election.

Marriage and family

Lord Cranbrook married Jane Stewart Orr, daughter of Irish landowner James Orr, in 1838. They had four sons and five daughters. One son and two of their daughters predeceased them. Lord Cranbrook died in October 1906, aged ninety-two, and was succeeded by his eldest son John. His third son the Hon.Alfred Gathorne-Hardy

Alfred Erskine Gathorne-Hardy (27 February 1845 – 11 November 1918), styled The Honourable from 1878, was a British Conservative Member of Parliament.

Gathorne-Hardy was the third son of Gathorne Gathorne-Hardy, 1st Earl of Cranbrook, and J ...

was also a politician.Debrett's Peerage and Baronetage (107th edition)

See also

**Irish Church Act 1869

The Irish Church Act 1869 (32 & 33 Vict. c. 42) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom which separated the Church of Ireland from the Church of England and disestablished the former, a body that commanded the adherence of a small min ...

** Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland ( ga, Eaglais na hÉireann, ; sco, label=Ulster-Scots, Kirk o Airlann, ) is a Christian church in Ireland and an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the second l ...

** Anglicanism

** Conservative Party

** Second Afghan War

The Second Anglo-Afghan War (Dari: جنگ دوم افغان و انگلیس, ps, د افغان-انګرېز دويمه جګړه) was a military conflict fought between the British Raj and the Emirate of Afghanistan from 1878 to 1880, when the l ...

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Cranbrook, Gathorne Gathorne-Hardy, 1st Earl of 1814 births 1906 deaths British Secretaries of State Chancellors of the Duchy of Lancaster Earls in the Peerage of the United Kingdom Knights Grand Commander of the Order of the Star of India Lord Presidents of the Council Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom People educated at Shrewsbury School Alumni of Oriel College, Oxford Hardy, Gathorne Hardy, Gathorne Hardy, Gathorne Hardy, Gathorne Hardy, Gathorne Hardy, Gathorne Hardy, Gathorne Hardy, Gathorne UK MPs who were granted peerages Gathorne-Hardy family Peers of the United Kingdom created by Queen Victoria