Garibaldi FS (Milan Metro), Garibaldi FS on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

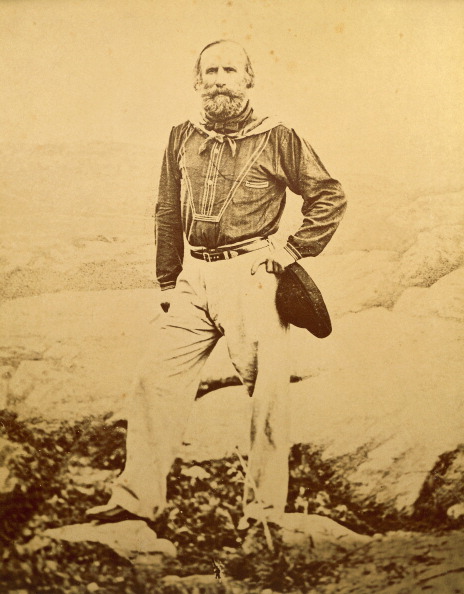

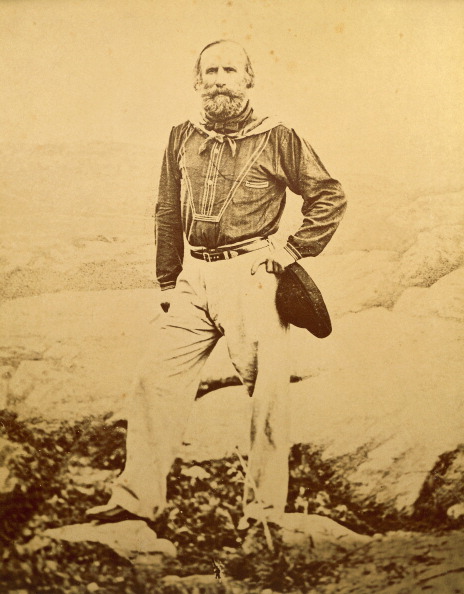

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi ( , ;In his native Ligurian language, he is known as (). In his particular Niçard dialect of Ligurian, he was known as () or (). 4 July 1807 – 2 June 1882) was an Italian general,

''LeCitazioni''. Retrieved 2 September 2020. "È il più generoso dei pirati che abbia mai incontrato." Francesco de Sanctis,

Garibaldi was born and christened Joseph-Marie GaribaldiPronounced in French as . on 4 July 1807 in

Garibaldi was born and christened Joseph-Marie GaribaldiPronounced in French as . on 4 July 1807 in

Garibaldi first sailed to the Beylik of Tunis before eventually finding his way to the

Garibaldi first sailed to the Beylik of Tunis before eventually finding his way to the

revolutionary

A revolutionary is a person who either participates in, or advocates for, a revolution. The term ''revolutionary'' can also be used as an adjective to describe something producing a major and sudden impact on society.

Definition

The term—bot ...

and republican. He contributed to Italian unification

The unification of Italy ( ), also known as the Risorgimento (; ), was the 19th century political and social movement that in 1861 ended in the annexation of various states of the Italian peninsula and its outlying isles to the Kingdom of ...

(Risorgimento) and the creation of the Kingdom of Italy. He is considered to be one of Italy's " fathers of the fatherland", along with Camillo Benso di Cavour, King Victor Emmanuel II and Giuseppe Mazzini

Giuseppe Mazzini (, ; ; 22 June 1805 – 10 March 1872) was an Italian politician, journalist, and activist for the unification of Italy (Risorgimento) and spearhead of the Italian revolutionary movement. His efforts helped bring about the ...

. Garibaldi is also known as the "Hero of the Two Worlds" because of his military enterprises in South America and Europe.

Garibaldi was a follower of the Italian nationalist Mazzini and embraced the republican nationalism of the Young Italy movement. He became a supporter of Italian unification under a democratic republic

A democratic republic is a form of government operating on principles adopted from a republic and a democracy. As a cross between two similar systems, democratic republics may function on principles shared by both republics and democracies.

Whil ...

an government. However, breaking with Mazzini, he pragmatically allied himself with the monarchist Cavour and Kingdom of Sardinia

The Kingdom of Sardinia, also referred to as the Kingdom of Sardinia and Corsica among other names, was a State (polity), country in Southern Europe from the late 13th until the mid-19th century, and from 1297 to 1768 for the Corsican part of ...

in the struggle for independence, subordinating his republican ideals to his nationalist ones until Italy was unified. After participating in an uprising in Piedmont, he was sentenced to death, but escaped and sailed to South America, where he spent 14 years in exile, during which he took part in several wars and learned the art of guerrilla warfare. In 1835 he joined the rebels known as the Ragamuffins (), in the Ragamuffin War in Brazil

Brazil, officially the Federative Republic of Brazil, is the largest country in South America. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by area, fifth-largest country by area and the List of countries and dependencies by population ...

, and took up their cause of establishing the Riograndense Republic and later the Catarinense Republic. Garibaldi also became involved in the Uruguayan Civil War

The Uruguayan Civil War, also known in Spanish as the ''Guerra Grande'' ("Great War"), was a series of armed conflicts between the leaders of Uruguayan independence. While officially the war lasted from 1839 until 1851, it was a part of armed ...

, raising an Italian force known as Redshirts, and is still celebrated as an important contributor to Uruguay's reconstitution.

In 1848, Garibaldi returned to Italy and commanded and fought in military campaigns that eventually led to Italian unification. The provisional government of Milan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

made him a general and the Minister of War

A ministry of defence or defense (see American and British English spelling differences#-ce.2C -se, spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is the part of a government responsible for matters of defence and Mi ...

promoted him to General of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

in 1849. When the war of independence

Wars of national liberation, also called wars of independence or wars of liberation, are conflicts fought by nations to gain independence. The term is used in conjunction with wars against foreign powers (or at least those perceived as foreign) ...

broke out in April 1859, he led his Hunters of the Alps in the capture of major cities in Lombardy

The Lombardy Region (; ) is an administrative regions of Italy, region of Italy that covers ; it is located in northern Italy and has a population of about 10 million people, constituting more than one-sixth of Italy's population. Lombardy is ...

, including Varese

Varese ( , ; or ; ; ; archaic ) is a city and ''comune'' in north-western Lombardy, northern Italy, north-west of Milan. The population of Varese in 2018 was 80,559.

It is the capital of the Province of Varese. The hinterland or exurban part ...

and Como, and reached the frontier of South Tyrol

South Tyrol ( , ; ; ), officially the Autonomous Province of Bolzano – South Tyrol, is an autonomous administrative division, autonomous provinces of Italy, province in northern Italy. Together with Trentino, South Tyrol forms the autonomo ...

; the war ended with the acquisition of Lombardy. The following year, 1860, he led the Expedition of the Thousand

The Expedition of the Thousand () was an event of the unification of Italy that took place in 1860. A corps of volunteers led by Giuseppe Garibaldi sailed from Quarto al Mare near Genoa and landed in Marsala, Sicily, in order to conquer the Ki ...

on behalf of, and with the consent of, Victor Emmanuel II, King of Sardinia. The expedition was a success and concluded with the annexation of Sicily, Southern Italy, Marche and Umbria to the Kingdom of Sardinia before the creation of a unified Kingdom of Italy on 17 March 1861. His last military campaign took place during the Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

as commander of the Army of the Vosges.

Garibaldi became an international figurehead for national independence and republican ideals, and is considered by twentieth-century historiography and popular culture as Italy's greatest national hero. He was showered with admiration and praise by many contemporary intellectuals and political figures, including Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

,Mack Smith, ed., Denis (1969). ''Garibaldi'' (Great Lives Observed). Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs. pp. 69–70. . William Brown,"Frasi di William Brown (ammiraglio)"''LeCitazioni''. Retrieved 2 September 2020. "È il più generoso dei pirati che abbia mai incontrato." Francesco de Sanctis,

Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo, vicomte Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romanticism, Romantic author, poet, essayist, playwright, journalist, human rights activist and politician.

His most famous works are the novels ''The Hunchbac ...

, Alexandre Dumas

Alexandre Dumas (born Alexandre Dumas Davy de la Pailleterie, 24 July 1802 – 5 December 1870), also known as Alexandre Dumas , was a French novelist and playwright.

His works have been translated into many languages and he is one of the mos ...

, Malwida von Meysenbug, George Sand

Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin de Francueil (; 1 July 1804 – 8 June 1876), best known by her pen name George Sand (), was a French novelist, memoirist and journalist. Being more renowned than either Victor Hugo or Honoré de Balz ...

, Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English novelist, journalist, short story writer and Social criticism, social critic. He created some of literature's best-known fictional characters, and is regarded by ...

, and Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ;"Engels"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.Jawaharlal Nehru Jawaharlal Nehru (14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat, and statesman who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20th century. Nehru was a pr ...

and ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.Jawaharlal Nehru Jawaharlal Nehru (14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat, and statesman who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20th century. Nehru was a pr ...

Che Guevara

Ernesto "Che" Guevara (14th May 1928 – 9 October 1967) was an Argentines, Argentine Communist revolution, Marxist revolutionary, physician, author, Guerrilla warfare, guerrilla leader, diplomat, and Military theory, military theorist. A majo ...

.Di Mino, Massimiliano; Di Mino, Pier Paolo (2011). ''Il libretto rosso di Garibaldi''. Rome: Castelvecchi Editore. p. 7. . Historian A. J. P. Taylor called him "the only wholly admirable figure in modern history". The volunteers who followed Garibaldi during his campaigns were known as the ''Garibaldini'' or Redshirts, after the color of the shirts that they wore in lieu of a uniform.

Early life

Garibaldi was born and christened Joseph-Marie GaribaldiPronounced in French as . on 4 July 1807 in

Garibaldi was born and christened Joseph-Marie GaribaldiPronounced in French as . on 4 July 1807 in Nice

Nice ( ; ) is a city in and the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes department in France. The Nice agglomeration extends far beyond the administrative city limits, with a population of nearly one millionFrench Republic

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

in 1792, to the Liguria

Liguria (; ; , ) is a Regions of Italy, region of north-western Italy; its Capital city, capital is Genoa. Its territory is crossed by the Alps and the Apennine Mountains, Apennines Mountain chain, mountain range and is roughly coextensive with ...

n family of Domenico Garibaldi from Chiavari

Chiavari (; ) is a seaside comune (municipality) in the Metropolitan City of Genoa, in Italy. It has about 28,000 inhabitants. It has a beachside promenade and a marina and is situated near the river Entella (river), Entella.

History

Pre-Rom ...

and Maria Rosa Nicoletta Raimondi from Loano. In 1814, the Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon, Napol ...

returned Nice to Victor Emmanuel I of Sardinia

Victor Emmanuel I (; 24 July 1759 – 10 January 1824) was the Duke of Savoy, King of Sardinia and ruler of the Savoyard states from 4 June 1802 until his reign ended in 1821 upon abdication due to a liberal revolution. Shortly thereafter, hi ...

. (Nice would be returned to France in 1860 by the Treaty of Turin, over the objections of Garibaldi.)

Garibaldi's family's involvement in coastal trade drew him to a life at sea.

He lived in the Pera district of Istanbul

Istanbul is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, constituting the country's economic, cultural, and historical heart. With Demographics of Istanbul, a population over , it is home to 18% of the Demographics ...

from 1828 to 1832. He became an instructor and taught Italian, French, and mathematics in the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. Garibaldi had close ties with the vast Sardinian exile network in the Ottoman Empire, befriending people such as Giovanni Timoteo Calosso.

In April 1833, he travelled to Taganrog

Taganrog (, ) is a port city in Rostov Oblast, Russia, on the north shore of Taganrog Bay in the Sea of Azov, several kilometers west of the mouth of the Don (river), Don River. It is in the Black Sea region. Population:

Located at the site of a ...

, in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

, aboard the schooner

A schooner ( ) is a type of sailing ship, sailing vessel defined by its Rig (sailing), rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more Mast (sailing), masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than t ...

''Clorinda'' with a shipment of oranges. During ten days in port, he met Giovanni Battista Cuneo from Oneglia, a politically active immigrant and member of the secret Young Italy movement of Giuseppe Mazzini

Giuseppe Mazzini (, ; ; 22 June 1805 – 10 March 1872) was an Italian politician, journalist, and activist for the unification of Italy (Risorgimento) and spearhead of the Italian revolutionary movement. His efforts helped bring about the ...

. Mazzini was a passionate proponent of Italian unification as a liberal republic via political and social reform.

In November 1833, Garibaldi met Mazzini in Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

, starting a long relationship that later became troubled. He joined the Carbonari

The Carbonari () was an informal network of Secret society, secret revolutionary societies active in Italy from about 1800 to 1831. The Carbonari may have further influenced other revolutionary groups in France, Portugal, Spain, Brazil, Urugua ...

revolutionary association, and in February 1834 participated in a failed Mazzinian insurrection in Piedmont

Piedmont ( ; ; ) is one of the 20 regions of Italy, located in the northwest Italy, Northwest of the country. It borders the Liguria region to the south, the Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna regions to the east, and the Aosta Valley region to the ...

.

South America

Garibaldi first sailed to the Beylik of Tunis before eventually finding his way to the

Garibaldi first sailed to the Beylik of Tunis before eventually finding his way to the Empire of Brazil

The Empire of Brazil was a 19th-century state that broadly comprised the territories which form modern Brazil and Uruguay until the latter achieved independence in 1828. The empire's government was a Representative democracy, representative Par ...

. Once there, he took up the cause of the Riograndense Republic in its attempt to separate from Brazil, joining the rebels known as the Ragamuffins in the Ragamuffin War of 1835.

During this war, he met Ana Maria de Jesus Ribeiro da Silva, commonly known as Anita. When the rebels proclaimed the Catarinense Republic in the Brazilian province of Santa Catarina in 1839, she joined him aboard his ship, ''Rio Pardo'', and fought alongside him at the battles of Imbituba and Laguna.

In 1841, Garibaldi and Anita moved to Montevideo

Montevideo (, ; ) is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Uruguay, largest city of Uruguay. According to the 2023 census, the city proper has a population of 1,302,954 (about 37.2% of the country's total population) in an area of . M ...

, Uruguay, where Garibaldi worked as a trader and schoolmaster. The couple married in Church of St. Francis of Assisi in the Ciudad Vieja

Ciudad Vieja () is a town and municipality in the Guatemalan Departments of Guatemala, department of Sacatepéquez. According to the 2018 census, the town has a population of 32,802Domenico Menotti (1840–1903), Rosa (1843–1845), Teresa Teresita (1845–1903), and Ricciotti (1847–1924). A skilled horsewoman, Anita is said to have taught Giuseppe about the

Translated from Giuseppe Garibaldi Massone by the Grand Orient of Italy Garibaldi regularized his position later in 1844, joining the lodge Les Amis de la Patrie of

Garibaldi returned to Italy amidst the turmoil of the

Garibaldi returned to Italy amidst the turmoil of the  On 30 April 1849, the Republican army, under Garibaldi's command, defeated a numerically far superior French army at the Porta San Pancrazio gate of Rome. Subsequently, French reinforcements arrived, and the Siege of Rome began on 1 June. Despite the resistance of the Republican army, the French prevailed on 29 June. On 30 June the Roman Assembly met and debated three options: surrender, continue fighting in the streets, or retreat from Rome to continue resistance from the

On 30 April 1849, the Republican army, under Garibaldi's command, defeated a numerically far superior French army at the Porta San Pancrazio gate of Rome. Subsequently, French reinforcements arrived, and the Siege of Rome began on 1 June. Despite the resistance of the Republican army, the French prevailed on 29 June. On 30 June the Roman Assembly met and debated three options: surrender, continue fighting in the streets, or retreat from Rome to continue resistance from the

The ship was to be purchased in the United States. Garibaldi went to New York City, arriving on 30 July 1850. However, the funds for buying a ship were lacking. While in New York, he stayed with various Italian friends, including some exiled revolutionaries. He attended the Masonic lodges of New York in 1850, where he met several supporters of democratic internationalism, whose minds were open to socialist thought, and to giving Freemasonry a strong anti-papal stance.

The inventor Antonio Meucci employed Garibaldi in his candle factory on

The ship was to be purchased in the United States. Garibaldi went to New York City, arriving on 30 July 1850. However, the funds for buying a ship were lacking. While in New York, he stayed with various Italian friends, including some exiled revolutionaries. He attended the Masonic lodges of New York in 1850, where he met several supporters of democratic internationalism, whose minds were open to socialist thought, and to giving Freemasonry a strong anti-papal stance.

The inventor Antonio Meucci employed Garibaldi in his candle factory on

On 24 January 1860, Garibaldi married 18-year-old Giuseppina Raimondi. Immediately after the wedding ceremony, she informed him that she was pregnant with another man's child and Garibaldi left her the same day. At the beginning of April 1860, uprisings in

On 24 January 1860, Garibaldi married 18-year-old Giuseppina Raimondi. Immediately after the wedding ceremony, she informed him that she was pregnant with another man's child and Garibaldi left her the same day. At the beginning of April 1860, uprisings in  Swelling the ranks of his army with scattered bands of local rebels, Garibaldi led 800 volunteers to victory over an enemy force of 1,500 at the Battle of Calatafimi on 15 May. He used the counter-intuitive tactic of an uphill bayonet charge. He saw that the hill was terraced, and the terraces would shelter his advancing men. Though small by comparison with the coming clashes at Palermo, Milazzo, and Volturno, this battle was decisive in establishing Garibaldi's power on the island. An apocryphal but realistic story had him say to his lieutenant Nino Bixio, "Here we either make Italy, or we die." His Neapolitan adversaries now fought for him, which led to accusations of bribery being made against their leader, Francesco Landi.

The next day, he declared himself dictator of Sicily in the name of

Swelling the ranks of his army with scattered bands of local rebels, Garibaldi led 800 volunteers to victory over an enemy force of 1,500 at the Battle of Calatafimi on 15 May. He used the counter-intuitive tactic of an uphill bayonet charge. He saw that the hill was terraced, and the terraces would shelter his advancing men. Though small by comparison with the coming clashes at Palermo, Milazzo, and Volturno, this battle was decisive in establishing Garibaldi's power on the island. An apocryphal but realistic story had him say to his lieutenant Nino Bixio, "Here we either make Italy, or we die." His Neapolitan adversaries now fought for him, which led to accusations of bribery being made against their leader, Francesco Landi.

The next day, he declared himself dictator of Sicily in the name of  Having conquered Sicily, he crossed the

Having conquered Sicily, he crossed the

At the outbreak of the

At the outbreak of the

– The Civil War Society's "Encyclopedia of the Civil War" – Italian-Americans in the Civil War. Garibaldi expressed interest in aiding the Union, and he was offered a major general's commission in the U.S. Army through a letter from Secretary of State William H. Seward to Henry Shelton Sanford, the U.S. Minister at Brussels, 27 July 1861. On 9 September 1861, Sanford met with Garibaldi and reported the result of the meeting to Seward: But

Far from supporting this endeavour, the Italian government was quite disapproving. General Enrico Cialdini dispatched a division of the regular army, under Colonel Emilio Pallavicini, against the volunteer bands. On 28 August, the two forces met in the rugged

Far from supporting this endeavour, the Italian government was quite disapproving. General Enrico Cialdini dispatched a division of the regular army, under Colonel Emilio Pallavicini, against the volunteer bands. On 28 August, the two forces met in the rugged

Garibaldi took up arms again in 1866, this time with the full support of the Italian government. The

Garibaldi took up arms again in 1866, this time with the full support of the Italian government. The  In the same year, Garibaldi sought international support for altogether eliminating the papacy. At the 1867 congress for the League of Peace and Freedom in Geneva he proposed: "The papacy, being the most harmful of all secret societies, ought to be abolished."

In the same year, Garibaldi sought international support for altogether eliminating the papacy. At the 1867 congress for the League of Peace and Freedom in Geneva he proposed: "The papacy, being the most harmful of all secret societies, ought to be abolished."

Garibaldi had long claimed an interest in vague ethical socialism such as that advanced by Henri Saint-Simon and saw the struggle for liberty as an international affair, one which "does not make any distinction between the African and the American, the European and the Asian, and therefore proclaims the fraternity of all men whatever nation they belong to". He interpreted the

Garibaldi had long claimed an interest in vague ethical socialism such as that advanced by Henri Saint-Simon and saw the struggle for liberty as an international affair, one which "does not make any distinction between the African and the American, the European and the Asian, and therefore proclaims the fraternity of all men whatever nation they belong to". He interpreted the

Garibaldi's popularity, skill at rousing the common people, and his military exploits are all credited with making the unification of Italy possible. He was also a global exemplar of mid-19th century revolutionary liberalism and nationalism. After the liberation of southern Italy from the House of Bourbon, Neapolitan monarchy in the

Garibaldi's popularity, skill at rousing the common people, and his military exploits are all credited with making the unification of Italy possible. He was also a global exemplar of mid-19th century revolutionary liberalism and nationalism. After the liberation of southern Italy from the House of Bourbon, Neapolitan monarchy in the  Along with Giuseppe Mazzini and other Europeans, Garibaldi supported the creation of a European federation. Many Europeans expected that the 1871 unification of Germany would make Germany a European and world leader that would champion humanitarian policies. This idea is apparent in the following letter Garibaldi sent to Karl Blind on 10 April 1865:

Through the years, Garibaldi was showered with admiration and praises by many intellectuals and political figures. Francesco De Sanctis stated that "Garibaldi must win by force: he is not a man; he is a symbol, a form; he is the Italian soul. Between the beats of his heart, everyone hears the beats of his own."De Santis, Francesco; Ferrarelli, Giuseppe, ed. (1900)

Along with Giuseppe Mazzini and other Europeans, Garibaldi supported the creation of a European federation. Many Europeans expected that the 1871 unification of Germany would make Germany a European and world leader that would champion humanitarian policies. This idea is apparent in the following letter Garibaldi sent to Karl Blind on 10 April 1865:

Through the years, Garibaldi was showered with admiration and praises by many intellectuals and political figures. Francesco De Sanctis stated that "Garibaldi must win by force: he is not a man; he is a symbol, a form; he is the Italian soul. Between the beats of his heart, everyone hears the beats of his own."De Santis, Francesco; Ferrarelli, Giuseppe, ed. (1900)

''Scritti politici di Francesco de Sanctis''

Naples: Antonio Morano e Figlio Editorivia the Internet Archive. Admiral William Brown called him "the most generous of the pirates I have ever encountered". Argentine revolutionary

Gay, H. Nelson, "Lincoln's Offer of a Command to Garibaldi: Light on a Disputed Point of History", ''The Century Magazine'' LXXV (Nov. 1907): 66

* Christopher Hibbert, Hibbert, Christopher. ''Garibaldi and His Enemies: The Clash of Arms and Personalities in the Making of Italy'' (1965), a standard biography. * pp. 332–416.

Mack Smith, Denis, ed. ''Garibaldi'' (Great Lives Observed), Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

(primary and secondary sources) * Denis Mack Smith, Mack Smith, Denis. "Giuseppe Garibaldi: 1807–1882". ''History Today'' (March 1956) 5 #3 pp. 188–196. * Mack Smith, Denis. ''Garibaldi: A Great Life in Brief'' (1956

online

*

Marraro, Howard R. "Lincoln's Offer of a Command to Garibaldi: Further Light on a Disputed Point of History." ''Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society'' 36 #3 (Sept. 1943): 237–270

* Tim Parks, Parks, Tim. ''The Hero's Way: Walking With Garibaldi From Rome to Ravenna'' (W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2021), travelogue in which Parks and his partner retrace Garibaldi and the Garibaldini's 1849 march. * Parris, John. ''The Lion of Caprera: A Biography of Giuseppe Garibaldi'' (Arthur Barker, 1962). * Lucy Riall, Riall, Lucy. ''The Italian Risorgimento: State, Society, and National Unification'' (Routledge, 1994

online

* Riall, Lucy. ''Garibaldi: Invention of a Hero'' (Yale University Press, 2007). * Riall, Lucy. "Hero, saint or revolutionary? Nineteenth-century politics and the cult of Garibaldi." ''Modern Italy'' 3.02 (1998): 191–204. * Riall, Lucy. "Travel, migration, exile: Garibaldi's global fame." ''Modern Italy'' 19.1 (2014): 41–52. * Jasper Ridley (historian), Ridley, Jasper. ''Garibaldi'' (1974), a standard biograph

online

* * * * *

gaucho

A gaucho () or gaúcho () is a skilled horseman, reputed to be brave and unruly. The figure of the gaucho is a folk symbol of Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil, the southern part of Bolivia, and the south of Chilean Patago ...

culture of Argentina, southern Brazil and Uruguay. Around this time he adopted his distinctive style of clothing—wearing the red shirt, poncho

A poncho (; ; ; "blanket", "woolen fabric") is a kind of plainly formed, loose outer garment originating in the Americas, traditionally and still usually made of fabric, and designed to keep the body warm. Ponchos have been used by the Indige ...

, and hat commonly worn by gauchos.

In 1842, Garibaldi took command of the Uruguayan fleet and raised an Italian Legion of soldiers—known as Redshirts—for the Uruguayan Civil War

The Uruguayan Civil War, also known in Spanish as the ''Guerra Grande'' ("Great War"), was a series of armed conflicts between the leaders of Uruguayan independence. While officially the war lasted from 1839 until 1851, it was a part of armed ...

. This recruitment was possible as Montevideo had a large Italian population at the time: 4,205 out of a total population of 30,000 according to an 1843 census.

Garibaldi aligned his forces with the Uruguayan Colorados led by Fructuoso Rivera and Joaquín Suárez, who were aligned with the Argentine Unitarian Party

The Unitarian Party was the political party who had proponents the concept of a unitary state (centralized government) in Buenos Aires during the Argentine Civil Wars, civil wars that shortly followed the Declaration of Independence of Argenti ...

. This faction received some support from the French and British in their struggle against the forces of former Uruguayan president Manuel Oribe

Manuel Ceferino Oribe y Viana (August 26, 1792 – November 12, 1857) was the 2nd Constitutional president of Uruguay and founder of Uruguay's National Party, the oldest Uruguayan political party and considered one of the two Uruguayan "tr ...

's Blancos, which was also aligned with Argentine Federales

''Federales'' is a slang term in English language, English and Spanish languages referring to security forces, particularly those of the federal government of Mexico. The term gained widespread usage by English speakers due to being popularized ...

under the rule of Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires, controlled by the government of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Argentina. It is located on the southwest of the Río de la Plata. Buenos Aires is classified as an Alpha− glob ...

caudillo Juan Manuel de Rosas

Juan Manuel José Domingo Ortiz de Rozas y López de Osornio (30 March 1793 – 14 March 1877), nicknamed "Restorer of the Laws", was an Argentine politician and army officer who ruled Buenos Aires Province and briefly the Argentine Confedera ...

. The Italian Legion adopted a black flag that represented Italy in mourning, with a volcano at the centre that symbolized the dormant power in their homeland. Though contemporary sources do not mention the Redshirts, popular history asserts that the legion first wore them in Uruguay, getting them from a factory in Montevideo that had intended to export them to the slaughterhouses of Argentina. These shirts became the symbol of Garibaldi and his followers.

Between 1842 and 1848, Garibaldi defended Montevideo against forces led by Oribe. In 1845, he managed to occupy Colonia del Sacramento

Colonia del Sacramento (; ) is a city in southwestern Uruguay, by the Río de la Plata, facing Buenos Aires, Argentina. It is one of the oldest towns in Uruguay and the capital of the Colonia Department. As of the 2023 census, it has a populatio ...

and Martín García Island, and led the infamous sacks of Martín García island and Gualeguaychú during the Anglo-French blockade of the Río de la Plata. Garibaldi escaped with his life after being defeated in the Costa Brava combat, delivered on 15 and 16 August 1842, thanks to the mercy of Admiral William Brown. The Argentines, wanting to pursue him to finish him off, were stopped by Brown who exclaimed "let him escape, that gringo is a brave man." Years later, a grandson of Garibaldi would be named William, in honour of Admiral Brown. Adopting amphibious guerrilla tactics, Garibaldi later achieved two victories during 1846, in the Battle of Cerro and the Battle of San Antonio del Santo.

Induction to Freemasonry

Garibaldi joinedFreemasonry

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

during his exile, taking advantage of the asylum the lodges offered to political refugees from European countries. At the age of 37, during 1844, Garibaldi was initiated in the Asilo de la Virtud Lodge of Montevideo. This was an irregular lodge under a Brazilian Freemasonry not recognized by the main international masonic obediences, such as the United Grand Lodge of England

The United Grand Lodge of England (UGLE) is the governing Masonic lodge for the majority of freemasons in England, Wales, and the Commonwealth of Nations. Claiming descent from the Masonic Grand Lodge formed 24 June 1717 at the Goose & Gridiron ...

or the Grand Orient de France.

While Garibaldi had little use for Masonic rituals, he was an active Freemason and regarded Freemasonry as a network that united progressive men as brothers both within nations and as a global community. Garibaldi was eventually elected as the Grand Master of the Grand Orient of Italy.Garibaldi – the masonTranslated from Giuseppe Garibaldi Massone by the Grand Orient of Italy Garibaldi regularized his position later in 1844, joining the lodge Les Amis de la Patrie of

Montevideo

Montevideo (, ; ) is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Uruguay, largest city of Uruguay. According to the 2023 census, the city proper has a population of 1,302,954 (about 37.2% of the country's total population) in an area of . M ...

under the Grand Orient of France.

Election of Pope Pius IX, 1846

The fate of his homeland continued to concern Garibaldi. The election ofPope Pius IX

Pope Pius IX (; born Giovanni Maria Battista Pietro Pellegrino Isidoro Mastai-Ferretti; 13 May 1792 – 7 February 1878) was head of the Catholic Church from 1846 to 1878. His reign of nearly 32 years is the longest verified of any pope in hist ...

in 1846 caused a sensation among Italian patriots, both at home and in exile. Pius's initial reforms seemed to identify him as the liberal pope called for by Vincenzo Gioberti, who went on to lead the unification of Italy. When news of these reforms reached Montevideo, Garibaldi wrote to the Pope:

Mazzini, from exile, also applauded the early reforms of Pius IX. In 1847, Garibaldi offered the apostolic nuncio

An apostolic nuncio (; also known as a papal nuncio or simply as a nuncio) is an ecclesiastical diplomat, serving as an envoy or a permanent diplomatic representative of the Holy See to a state or to an international organization. A nuncio is ...

at Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro, or simply Rio, is the capital of the Rio de Janeiro (state), state of Rio de Janeiro. It is the List of cities in Brazil by population, second-most-populous city in Brazil (after São Paulo) and the Largest cities in the America ...

, Bedini, the service of his Italian Legion for the liberation of the peninsula. Then news of the outbreak of the Sicilian revolution of 1848 in January and revolutionary agitation elsewhere in Italy, encouraged Garibaldi to lead approximately 60 members of his legion home.

Return to Italy

First Italian War of Independence

Garibaldi returned to Italy amidst the turmoil of the

Garibaldi returned to Italy amidst the turmoil of the revolutions of 1848 in the Italian states

The 1848 Revolutions in the Italian states, part of the wider Revolutions of 1848 in Europe, were organized revolts in the states of the Italian peninsula and Sicily, led by intellectuals and agitators who desired a liberal government. As Italian ...

and was one of the founders and leaders of the Action Party. Garibaldi offered his services to Charles Albert of Sardinia, who displayed some liberal inclinations, but he treated Garibaldi with coolness and distrust. Rebuffed by the Piedmontese, he and his followers crossed into Lombardy

The Lombardy Region (; ) is an administrative regions of Italy, region of Italy that covers ; it is located in northern Italy and has a population of about 10 million people, constituting more than one-sixth of Italy's population. Lombardy is ...

where they offered assistance to the provisional government of Milan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

, which had rebelled against the Austrian occupation. In the course of the following unsuccessful First Italian War of Independence

The First Italian War of Independence (), part of the ''Risorgimento'' or unification of Italy, was fought by the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia (Piedmont) and Italian volunteers against the Austrian Empire and other conse ...

, Garibaldi led his legion to two minor victories at Luino and Morazzone.

After the crushing Piedmontese defeat at the Battle of Novara on 23 March 1849, Garibaldi moved to Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

to support the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

recently proclaimed in the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; ; ), officially the State of the Church, were a conglomeration of territories on the Italian peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope from 756 to 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th c ...

. However, a French force sent by Louis Napoleon threatened to topple it. At Mazzini's urging, Garibaldi took command of the defence of Rome. In fighting near Velletri

Velletri (; ; ) is an Italian ''comune'' in the Metropolitan City of Rome, approximately 40 km to the southeast of the city centre, located in the Alban Hills, in the region of Lazio, central Italy. Neighbouring communes are Rocca di Papa, Lar ...

, Achille Cantoni saved his life. After Cantoni's death, during the Battle of Mentana, Garibaldi wrote the novel ''Cantoni the Volunteer''.

On 30 April 1849, the Republican army, under Garibaldi's command, defeated a numerically far superior French army at the Porta San Pancrazio gate of Rome. Subsequently, French reinforcements arrived, and the Siege of Rome began on 1 June. Despite the resistance of the Republican army, the French prevailed on 29 June. On 30 June the Roman Assembly met and debated three options: surrender, continue fighting in the streets, or retreat from Rome to continue resistance from the

On 30 April 1849, the Republican army, under Garibaldi's command, defeated a numerically far superior French army at the Porta San Pancrazio gate of Rome. Subsequently, French reinforcements arrived, and the Siege of Rome began on 1 June. Despite the resistance of the Republican army, the French prevailed on 29 June. On 30 June the Roman Assembly met and debated three options: surrender, continue fighting in the streets, or retreat from Rome to continue resistance from the Apennine Mountains

The Apennines or Apennine Mountains ( ; or Ἀπέννινον ὄρος; or – a singular with plural meaning; )Latin ''Apenninus'' (Greek or ) has the form of an adjective, which would be segmented ''Apenn-inus'', often used with nouns s ...

. Garibaldi, having entered the chamber covered in blood, made a speech favouring the third option, ending with: ''Ovunque noi saremo, sarà Roma'' ("Wherever we will go, that will be Rome").

The sides negotiated a truce on 1–2 July, Garibaldi withdrew from Rome with 4,000 troops, and ceded his ambition to rouse popular rebellion against the Austrians in central Italy. The French Army entered Rome on 3 July and reestablished the Holy See

The Holy See (, ; ), also called the See of Rome, the Petrine See or the Apostolic See, is the central governing body of the Catholic Church and Vatican City. It encompasses the office of the pope as the Bishops in the Catholic Church, bishop ...

's temporal power. Garibaldi and his forces, hunted by Austrian, French, Spanish, and Neapolitan troops, fled to the north, intending to reach Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

, where the Venetians were still resisting the Austrian siege. After an epic march, Garibaldi took temporary refuge in San Marino

San Marino, officially the Republic of San Marino, is a landlocked country in Southern Europe, completely surrounded by Italy. Located on the northeastern slopes of the Apennine Mountains, it is the larger of two European microstates, microsta ...

, with only 250 men having not abandoned him. Anita, who was carrying their fifth child, died near Comacchio during the retreat.

North America and the Pacific

Garibaldi eventually managed to reachPorto Venere

Porto Venere (; until 1991 ''Portovenere''; ) is a town and ''comune'' (municipality) located on the Ligurian coast of Italy in the province of La Spezia. It comprises the three villages of Fezzano, Le Grazie and Porto Venere, and the three islan ...

, near La Spezia

La Spezia (, or ; ; , in the local ) is the capital city of the province of La Spezia and is located at the head of the Gulf of La Spezia in the southern part of the Liguria region of Italy.

La Spezia is the second-largest city in the Liguria ...

, but the Piedmontese government forced him to emigrate again. He went to Tangier

Tangier ( ; , , ) is a city in northwestern Morocco, on the coasts of the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. The city is the capital city, capital of the Tanger-Tetouan-Al Hoceima region, as well as the Tangier-Assilah Prefecture of Moroc ...

, where he stayed with Francesco Carpanetto, a wealthy Italian merchant. Carpanetto suggested that he and some of his associates finance the purchase of a merchant ship, which Garibaldi would command. Garibaldi agreed, feeling that his political goals were, for the moment, unreachable, and he could at least earn a living.

Staten Island

Staten Island ( ) is the southernmost of the boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City, coextensive with Richmond County and situated at the southernmost point of New York (state), New York. The borough is separated from the ad ...

(the cottage where he stayed is listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government's official United States National Register of Historic Places listings, list of sites, buildings, structures, Hist ...

and is preserved as the Garibaldi Memorial). Garibaldi was not satisfied with this, and in April 1851 he left New York with his friend Carpanetto for Central America, where Carpanetto was establishing business operations. They first went to Nicaragua, and then to other parts of the region. Garibaldi accompanied Carpanetto as a companion, not a business partner, and used the name ''Giuseppe Pane''.

Carpanetto went on to Lima

Lima ( ; ), founded in 1535 as the Ciudad de los Reyes (, Spanish for "City of Biblical Magi, Kings"), is the capital and largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón River, Chillón, Rímac River, Rímac and Lurín Rive ...

, Peru, where a shipload of his goods was due, arriving late in 1851 with Garibaldi. En route, Garibaldi called on revolutionary heroine Manuela Sáenz. At Lima, Garibaldi was generally welcomed. A local Italian merchant, Pietro Denegri, gave him command of his ship ''Carmen'' for a trading voyage across the Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is bounded by the cont ...

, for which he required Peruvian citizenship, which he obtained that year. Garibaldi took the ''Carmen'' to the Chincha Islands for a load of guano

Guano (Spanish from ) is the accumulated excrement of seabirds or bats. Guano is a highly effective fertiliser due to the high content of nitrogen, phosphate, and potassium, all key nutrients essential for plant growth. Guano was also, to a le ...

. Then on 10 January 1852, he sailed from Peru for Canton, China, arriving in April.

After side trips to Xiamen

Xiamen,), also known as Amoy ( ; from the Zhangzhou Hokkien pronunciation, zh, c=, s=, t=, p=, poj=Ē͘-mûi, historically romanized as Amoy, is a sub-provincial city in southeastern Fujian, People's Republic of China, beside the Taiwan Stra ...

and Manila

Manila, officially the City of Manila, is the Capital of the Philippines, capital and second-most populous city of the Philippines after Quezon City, with a population of 1,846,513 people in 2020. Located on the eastern shore of Manila Bay on ...

, Garibaldi brought the ''Carmen'' back to Peru via the Indian Ocean and the South Pacific, passing clear around the south coast of Australia. He visited Three Hummock Island in the Bass Strait

Bass Strait () is a strait separating the island state of Tasmania from the Mainland Australia, Australian mainland (more specifically the coast of Victoria (Australia), Victoria, with the exception of the land border across Boundary Islet). The ...

. Garibaldi then took the ''Carmen'' on a second voyage: to the United States via Cape Horn

Cape Horn (, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which is Águila Islet), Cape Horn marks the nor ...

with copper from Chile, and also wool. Garibaldi arrived in Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

and went on to New York. There he received a hostile letter from Denegri and resigned his command. Another Italian, Captain Figari, had just come to the U.S. to buy a ship and hired Garibaldi to take the ship to Europe. Figari and Garibaldi bought the ''Commonwealth'' in Baltimore

Baltimore is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland. With a population of 585,708 at the 2020 census and estimated at 568,271 in 2024, it is the 30th-most populous U.S. city. The Baltimore metropolitan area is the 20th-large ...

, and Garibaldi left New York for the last time in November 1853. He sailed the ''Commonwealth'' to London, and then to Newcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne, or simply Newcastle ( , Received Pronunciation, RP: ), is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. It is England's northernmost metropolitan borough, located o ...

for coal.

Tyneside

The ''Commonwealth'' arrived on 21 March 1854. Garibaldi, already a popular figure onTyneside

Tyneside is a List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, built-up area across the banks of the River Tyne, England, River Tyne in Northern England. The population of Tyneside as published in the United Kingdom Census 2011, 2011 census was 774,891 ...

, was welcomed enthusiastically by local working men—although the ''Newcastle Courant'' reported that he refused an invitation to dine with dignitaries in the city. He stayed in Huntingdon Place Tynemouth

Tynemouth () is a coastal town in the metropolitan borough of North Tyneside, in Tyne and Wear, England. It is located on the north side of the mouth of the River Tyne, England, River Tyne, hence its name. It is east-northeast of Newcastle up ...

for a few days, and in South Shields

South Shields () is a coastal town in South Tyneside, Tyne and Wear, England; it is on the south bank of the mouth of the River Tyne. The town was once known in Roman Britain, Roman times as ''Arbeia'' and as ''Caer Urfa'' by the Early Middle Ag ...

on Tyneside for over a month, departing at the end of April 1854. During his stay, he was presented with an inscribed sword, which his grandson Giuseppe Garibaldi II later carried as a volunteer in British service in the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

. He then sailed to Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

, where his five years of exile ended on 10 May 1854.

Second Italian War of Independence

Garibaldi returned to Italy in 1854. Using an inheritance from the death of his brother, he bought half of the Italian island of Caprera (north ofSardinia

Sardinia ( ; ; ) is the Mediterranean islands#By area, second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, and one of the Regions of Italy, twenty regions of Italy. It is located west of the Italian Peninsula, north of Tunisia an ...

), devoting himself to agriculture. In 1859, the Second Italian War of Independence

The Second Italian War of Independence, also called the Sardinian War, the Austro-Sardinian War, the Franco-Austrian War, or the Italian War of 1859 (Italian: ''Seconda guerra d'indipendenza italiana''; German: ''Sardinischer Krieg''; French: ...

(also known as the Franco-Austrian War) broke out in the midst of internal plots at the Sardinian government. Garibaldi was appointed major general and formed a volunteer unit named the Hunters of the Alps (''Cacciatori delle Alpi''). Thenceforth, Garibaldi abandoned Mazzini's republican ideal of the liberation of Italy, assuming that only the Sardinian monarchy could effectively achieve it. He and his volunteers won victories over the Austrians at Varese

Varese ( , ; or ; ; ; archaic ) is a city and ''comune'' in north-western Lombardy, northern Italy, north-west of Milan. The population of Varese in 2018 was 80,559.

It is the capital of the Province of Varese. The hinterland or exurban part ...

, Como, and other places.

Garibaldi was very displeased as his home city of Nice (''Nizza'' in Italian) had been surrendered to the French in return for crucial military assistance. In April 1860, as deputy for Nice in the Piedmontese parliament at Turin

Turin ( , ; ; , then ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital from 1861 to 1865. The city is main ...

, he vehemently attacked Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour

Camillo Paolo Filippo Giulio Benso, Count of Cavour, Isolabella and Leri (; 10 August 1810 – 6 June 1861), generally known as the Count of Cavour ( ; ) or simply Cavour, was an Italian politician, statesman, businessman, economist, and no ...

, for ceding the County of Nice

The County of Nice (; ; Niçard ) was a historical region of France and Italy located around the southeastern city of Nice and roughly equivalent to the modern arrondissement of Nice. It was part of the Savoyard state within the Holy Roman Emp ...

(''Nizzardo'') to Emperor Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

of France. In the following years, Garibaldi (with other passionate Niçard Italians

Niçard Italians ( ) are Italians who have full or partial County of Nice, Nice heritage by birth or ethnicity.

History

Niçard Italians have roots in Nice and the County of Nice. They often speak the Ligurian language after Nice joined the Genoa ...

) promoted the Italian irredentism of his native city, supporting the Niçard Vespers riots in 1871.

Campaign of 1860

On 24 January 1860, Garibaldi married 18-year-old Giuseppina Raimondi. Immediately after the wedding ceremony, she informed him that she was pregnant with another man's child and Garibaldi left her the same day. At the beginning of April 1860, uprisings in

On 24 January 1860, Garibaldi married 18-year-old Giuseppina Raimondi. Immediately after the wedding ceremony, she informed him that she was pregnant with another man's child and Garibaldi left her the same day. At the beginning of April 1860, uprisings in Messina

Messina ( , ; ; ; ) is a harbour city and the capital city, capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of 216,918 inhabitants ...

and Palermo

Palermo ( ; ; , locally also or ) is a city in southern Italy, the capital (political), capital of both the autonomous area, autonomous region of Sicily and the Metropolitan City of Palermo, the city's surrounding metropolitan province. The ...

in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies () was a kingdom in Southern Italy from 1816 to 1861 under the control of the House of Bourbon-Two Sicilies, a cadet branch of the House of Bourbon, Bourbons. The kingdom was the largest sovereign state by popula ...

provided Garibaldi with an opportunity. He gathered a group of volunteers called ''i Mille'' (the Thousand), or the Redshirts as popularly known, in two ships named ''Il Piemonte'' and ''Il Lombardo'', and left from Quarto

Quarto (abbreviated Qto, 4to or 4º) is the format of a book or pamphlet produced from full sheets printed with eight pages of text, four to a side, then folded twice to produce four leaves. The leaves are then trimmed along the folds to produc ...

, in Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

, on 5 May in the evening and landed at Marsala

Marsala (, ; ) is an Italian comune located in the Province of Trapani in the westernmost part of Sicily. Marsala is the most populated town in its province and the fifth largest in Sicily.The town is famous for the docking of Giuseppe Garibal ...

, on the westernmost point of Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

, on 11 May.

Swelling the ranks of his army with scattered bands of local rebels, Garibaldi led 800 volunteers to victory over an enemy force of 1,500 at the Battle of Calatafimi on 15 May. He used the counter-intuitive tactic of an uphill bayonet charge. He saw that the hill was terraced, and the terraces would shelter his advancing men. Though small by comparison with the coming clashes at Palermo, Milazzo, and Volturno, this battle was decisive in establishing Garibaldi's power on the island. An apocryphal but realistic story had him say to his lieutenant Nino Bixio, "Here we either make Italy, or we die." His Neapolitan adversaries now fought for him, which led to accusations of bribery being made against their leader, Francesco Landi.

The next day, he declared himself dictator of Sicily in the name of

Swelling the ranks of his army with scattered bands of local rebels, Garibaldi led 800 volunteers to victory over an enemy force of 1,500 at the Battle of Calatafimi on 15 May. He used the counter-intuitive tactic of an uphill bayonet charge. He saw that the hill was terraced, and the terraces would shelter his advancing men. Though small by comparison with the coming clashes at Palermo, Milazzo, and Volturno, this battle was decisive in establishing Garibaldi's power on the island. An apocryphal but realistic story had him say to his lieutenant Nino Bixio, "Here we either make Italy, or we die." His Neapolitan adversaries now fought for him, which led to accusations of bribery being made against their leader, Francesco Landi.

The next day, he declared himself dictator of Sicily in the name of Victor Emmanuel II of Italy

Victor Emmanuel II (; full name: ''Vittorio Emanuele Maria Alberto Eugenio Ferdinando Tommaso di House of Savoy, Savoia''; 14 March 1820 – 9 January 1878) was King of Sardinia (also informally known as Piedmont–Sardinia) from 23 March 1849 u ...

. He advanced to the outskirts of Palermo, the capital of the island, and launched a siege on 27 May. He had the support of many inhabitants, who rose up against the garrison, but before they could take the city, reinforcements arrived and bombarded the city nearly to ruins. At this time, a British admiral intervened and facilitated a truce, by which the Neapolitan royal troops and warships surrendered the city and departed. The young Henry Adams—later to become a distinguished American writer—visited the city in June and described the situation, along with his meeting with Garibaldi, in a long and vivid letter to his older brother Charles. Historians Clough et al. argue that Garibaldi's Thousand were students, independent artisans, and professionals, not peasants. The support given by Sicilian peasants was not out of a sense of patriotism but from their hatred of exploitive landlords and oppressive Neapolitan officials. Garibaldi himself had no interest in social revolution and instead sided with the Sicilian landlords against the rioting peasants.

By conquering Palermo, Garibaldi had won a signal victory. He gained worldwide renown and the adulation of Italians. Faith in his prowess was so strong that doubt, confusion, and dismay seized even the Neapolitan court. Six weeks later, he marched against Messina in the east of the island, winning a ferocious and difficult Battle of Milazzo Battle of Milazzo may refer to the following battles fought near the city of Milazzo in Sicily, southern Italy:

* Battle of Mylae (260 BC)

*Battle of Milazzo (880)

*Battle of Milazzo (888)

*Battle of Milazzo (1718), during the War of the Quadruple ...

. By the end of July, only the citadel resisted.

Having conquered Sicily, he crossed the

Having conquered Sicily, he crossed the Strait of Messina

The Strait of Messina (; ) is a narrow strait between the eastern tip of Sicily (Punta del Faro) and the western tip of Calabria (Punta Pezzo) in Southern Italy. It connects the Tyrrhenian Sea to the north with the Ionian Sea to the south, with ...

and marched north. Garibaldi's progress was met with more celebration than resistance, and on 7 September he entered the capital city of Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

, by train. Despite taking Naples, however, he had not to this point defeated the Neapolitan army. Garibaldi's volunteer army of 24,000 was not able to conclusively defeat the reorganized Neapolitan army—about 25,000 men—on 30 September at the Battle of Volturno. This was the largest battle he ever fought, but its outcome was effectively decided by the arrival of the Royal Sardinian Army.

Meanwhile, Garibaldi's victories started to cause disquiet to the Piedmont, and particularly the Sardinian prime minister, Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour

Camillo Paolo Filippo Giulio Benso, Count of Cavour, Isolabella and Leri (; 10 August 1810 – 6 June 1861), generally known as the Count of Cavour ( ; ) or simply Cavour, was an Italian politician, statesman, businessman, economist, and no ...

. He feared that, should the revolutionaries succeed in conquering the entire Neapolitan state, they would then invade the Papal States, which would lead to France intervening. The Piedmontese themselves had conquered most of the Pope's territories in their march south to meet Garibaldi, but they had deliberately avoided Rome, the capital of the Papal state. Garibaldi deeply disliked Cavour. To an extent, he simply mistrusted Cavour's pragmatism and '' realpolitik'', but he also bore a personal grudge for Cavour's trading away his home city of Nice to the French the previous year. On the other hand, he supported the Sardinian monarch, Victor Emmanuel II, despite his dislike of royalty, who he admired as a champion of Italian independence. In his famous meeting with Victor Emmanuel at Teano on 26 October 1860, Garibaldi greeted him as King of Italy

King is a royal title given to a male monarch. A king is an absolute monarch if he holds unrestricted governmental power or exercises full sovereignty over a nation. Conversely, he is a constitutional monarch if his power is restrained by ...

and shook his hand. Garibaldi rode into Naples at the king's side on 7 November, then retired to the rocky island of Caprera, refusing to accept any reward for his services.Godkin, 1880 p. 230.

Aftermath

At the outbreak of the

At the outbreak of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

(in 1861), Garibaldi was a very popular figure. The 39th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment was named ''Garibaldi Guard'' after him.Civil War Home– The Civil War Society's "Encyclopedia of the Civil War" – Italian-Americans in the Civil War. Garibaldi expressed interest in aiding the Union, and he was offered a major general's commission in the U.S. Army through a letter from Secretary of State William H. Seward to Henry Shelton Sanford, the U.S. Minister at Brussels, 27 July 1861. On 9 September 1861, Sanford met with Garibaldi and reported the result of the meeting to Seward: But

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

was not ready to free the slaves; Sanford's meeting with Garibaldi occurred a year before Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War. The Proclamation had the eff ...

. Sanford's mission was hopeless, and Garibaldi did not join the Union army. A historian of the American Civil War, Don H. Doyle, however, wrote, "Garibaldi's full-throated endorsement of the Union cause roused popular support just as news of the Emancipation Proclamation broke in Europe." On 6 August 1863, after Lincoln had issued the final Emancipation Proclamation, Garibaldi wrote to Lincoln, "Posterity will call you the great emancipator, a more enviable title than any crown could be, and greater than any merely mundane treasure."

On 5 October 1860, Garibaldi set up the International Legion bringing together different national divisions of French, Poles, Swiss, Germans and other nationalities, with a view not just of finishing the liberation of Italy, but also of their homelands. With the motto "Free from the Alps

The Alps () are some of the highest and most extensive mountain ranges in Europe, stretching approximately across eight Alpine countries (from west to east): Monaco, France, Switzerland, Italy, Liechtenstein, Germany, Austria and Slovenia.

...

to the Adriatic", the unification movement set its gaze on Rome and Venice. Mazzini was discontented with the perpetuation of monarchial government, and continued to agitate for a republic. Garibaldi, frustrated at inaction by the king, and bristling over perceived snubs, organized a new venture. This time, he intended to take on the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; ; ), officially the State of the Church, were a conglomeration of territories on the Italian peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope from 756 to 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th c ...

.

Expedition against Rome

Garibaldi himself was intenselyanti-Catholic

Anti-Catholicism is hostility towards Catholics and opposition to the Catholic Church, its clergy, and its adherents. Scholars have identified four categories of anti-Catholicism: constitutional-national, theological, popular and socio-cul ...

and anti-papal. His efforts to overthrow the pope by military action mobilized anti-Catholic support. On 28 September 1862, 500 Irish labourers disrupted a pro-Garibaldi meeting in London by chanting "God and Rome", which triggered weeks of ethnic conflict between Protestants and Irish Catholics. Garibaldi's hostility to the pope's temporal domain was viewed with great distrust by Catholics around the world, and the French Emperor Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

had guaranteed the independence of Rome from Italy by stationing a French garrison there. Victor Emmanuel was wary of the international repercussions of attacking Rome and the pope's seat there, and discouraged his subjects from participating in revolutionary ventures with such intentions. Nonetheless, Garibaldi believed he had the secret support of his government. Once he was excommunicated by the pope, he chose the Protestant pastor Alessandro Gavazzi as his army chaplain.

In June 1862, he sailed from Genoa to Palermo to gather volunteers for the impending campaign, under the slogan ''Roma o Morte'' ("Rome or Death"). An enthusiastic party quickly joined him, and he turned for Messina, hoping to cross to the mainland there. He arrived with a force of around two thousand, but the garrison proved loyal to the king's instructions and barred his passage. They turned south and set sail from Catania

Catania (, , , Sicilian and ) is the second-largest municipality on Sicily, after Palermo, both by area and by population. Despite being the second city of the island, Catania is the center of the most densely populated Sicilian conurbation, wh ...

, where Garibaldi declared that he would enter Rome as a victor or perish beneath its walls. He landed at Melito di Porto Salvo on 14 August and marched at once into the Calabria

Calabria is a Regions of Italy, region in Southern Italy. It is a peninsula bordered by the region Basilicata to the north, the Ionian Sea to the east, the Strait of Messina to the southwest, which separates it from Sicily, and the Tyrrhenian S ...

n mountains.

Far from supporting this endeavour, the Italian government was quite disapproving. General Enrico Cialdini dispatched a division of the regular army, under Colonel Emilio Pallavicini, against the volunteer bands. On 28 August, the two forces met in the rugged

Far from supporting this endeavour, the Italian government was quite disapproving. General Enrico Cialdini dispatched a division of the regular army, under Colonel Emilio Pallavicini, against the volunteer bands. On 28 August, the two forces met in the rugged Aspromonte

The Aspromonte is a mountain massif in the Metropolitan City of Reggio Calabria (Calabria, southern Italy). In Italian aspro means "rough" whereas in Greek it means "white" (wikt:άσπρος, Άσπρος), therefore the name literally translat ...

. One of the regulars fired a chance shot, and several volleys followed, killing a few of the volunteers. The fighting ended quickly, as Garibaldi forbade his men to return fire on fellow subjects of the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

. Many of the volunteers were taken prisoner, including Garibaldi, who had been wounded by a shot in the foot. The episode was the origin of a famous Italian nursery rhyme

A nursery rhyme is a traditional poem or song for children in Britain and other European countries, but usage of the term dates only from the late 18th/early 19th century. The term Mother Goose rhymes is interchangeable with nursery rhymes.

Fr ...

: ''Garibaldi fu ferito'' ("Garibaldi was wounded").

A government steamer took him to a prison at Varignano near La Spezia

La Spezia (, or ; ; , in the local ) is the capital city of the province of La Spezia and is located at the head of the Gulf of La Spezia in the southern part of the Liguria region of Italy.

La Spezia is the second-largest city in the Liguria ...

, where he was held in a sort of honourable imprisonment and underwent a tedious and painful operation to heal his wound. His venture had failed, but he was consoled by Europe's sympathy and continued interest. After he regained his health, the government released Garibaldi and let him return to Caprera.

En route to London in 1864 he stopped briefly in Malta, where many admirers visited him in his hotel. Protests by opponents of his anticlericalism were suppressed by the authorities. In London, his presence was received with enthusiasm by the population. He met the British prime minister Viscount Palmerston, as well as revolutionaries then living in exile in the city. At that time, his ambitious international project included the liberation of a range of occupied nations, such as Croatia, Greece, and Hungary. He also visited Bedford

Bedford is a market town in Bedfordshire, England. At the 2011 Census, the population was 106,940. Bedford is the county town of Bedfordshire and seat of the Borough of Bedford local government district.

Bedford was founded at a ford (crossin ...

and was given a tour of the Britannia Iron Works, where he planted a tree (which was cut down in 1944 due to decay).

Final struggle with Austria

Garibaldi took up arms again in 1866, this time with the full support of the Italian government. The

Garibaldi took up arms again in 1866, this time with the full support of the Italian government. The Austro-Prussian War

The Austro-Prussian War (German: ''Preußisch-Österreichischer Krieg''), also known by many other names,Seven Weeks' War, German Civil War, Second War of Unification, Brothers War or Fraternal War, known in Germany as ("German War"), ''Deutsc ...

had broken out, and Italy had allied with Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

against the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire, officially known as the Empire of Austria, was a Multinational state, multinational European Great Powers, great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the Habsburg monarchy, realms of the Habsburgs. Duri ...

in the hope of taking Venetia from Austrian rule in the Third Italian War of Independence. Garibaldi gathered again his Hunters of the Alps, now some 40,000 strong, and led them into the Trentino

Trentino (), officially the Autonomous Province of Trento (; ; ), is an Autonomous province#Italy, autonomous province of Italy in the Northern Italy, country's far north. Trentino and South Tyrol constitute the Regions of Italy, region of Tren ...

. He defeated the Austrians at Bezzecca, and made for Trento

Trento ( or ; Ladin language, Ladin and ; ; ; ; ; ), also known in English as Trent, is a city on the Adige, Adige River in Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol in Italy. It is the capital of the Trentino, autonomous province of Trento. In the 16th ...

.

The Italian regular forces were defeated at Lissa on the sea, and made little progress on land after the disaster of Custoza. The sides signed an armistice by which Austria ceded Venetia to Italy, but this result was largely due to Prussia's successes on the northern front. Garibaldi's advance through Trentino was for nought, and he was ordered to stop his advance to Trento. Garibaldi answered with a short telegram from the main square of Bezzecca with the famous motto: ''Obbedisco!'' ("I obey!").

After the war, Garibaldi led a political party that agitated for the capture of Rome, the peninsula's ancient capital. In 1867, he again marched on the city, but the Papal army, supported by a French auxiliary force, proved a match for his badly armed volunteers. He was shot in the leg in the Battle of Mentana, and had to withdraw from the Papal territory. The Italian government again imprisoned him for some time, after which he returned to Caprera.

In the same year, Garibaldi sought international support for altogether eliminating the papacy. At the 1867 congress for the League of Peace and Freedom in Geneva he proposed: "The papacy, being the most harmful of all secret societies, ought to be abolished."

In the same year, Garibaldi sought international support for altogether eliminating the papacy. At the 1867 congress for the League of Peace and Freedom in Geneva he proposed: "The papacy, being the most harmful of all secret societies, ought to be abolished."

Franco-Prussian War

When theFranco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

broke out in July 1870, Italian public opinion heavily favoured the Prussians, and many Italians attempted to sign up as volunteers at the Prussian embassy in Florence. After the French garrison was recalled from Rome, the Italian Army captured the Papal States without Garibaldi's assistance. Following the wartime collapse of the Second French Empire

The Second French Empire, officially the French Empire, was the government of France from 1852 to 1870. It was established on 2 December 1852 by Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, president of France under the French Second Republic, who proclaimed hi ...

after the Battle of Sedan, Garibaldi, undaunted by the recent hostility shown to him by the men of Napoleon III, switched his support to the newly declared Government of National Defense of France. On 7 September 1870, within three days of the revolution in Paris that ended the Empire, he wrote to the ''Movimento'' of Genoa, "Yesterday I said to you: war to the death to Bonaparte. Today I say to you: rescue the French Republic by every means."

Subsequently, Garibaldi went to France and assumed command of the Army of the Vosges, an army of volunteers. French socialist Louis Blanc

Louis Jean Joseph Charles Blanc ( ; ; 29 October 1811 – 6 December 1882) was a French Socialism, socialist politician, journalist and historian. He called for the creation of cooperatives in order to job guarantee, guarantee employment for t ...

referred to Garibaldi as a "soldier of revolutionary cosmopolitanism" based on his support for liberation movements throughout the world. After the war he was elected to the French National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the repr ...

, where he briefly served as a member of Parliament for Alpes-Maritimes

Alpes-Maritimes (; ; ; ) is a Departments of France, department of France located in the country's southeast corner, on the France–Italy border, Italian border and Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean coast. Part of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'A ...

before returning to Caprera.

Involvement with the First International

When theParis Commune