GalĂ¡pagos Tortoise on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The GalĂ¡pagos tortoise or GalĂ¡pagos giant tortoise (''Chelonoidis niger'') is a species of very large

Within the archipelago, 14-15 subspecies of GalĂ¡pagos tortoises have been identified, although only 12 survive to this day. Five are found on separate islands; five of them on the volcanoes of Isabela Island. Several of the surviving subspecies are seriously endangered. A 13th subspecies, '' C. n. abingdonii'' from

Within the archipelago, 14-15 subspecies of GalĂ¡pagos tortoises have been identified, although only 12 survive to this day. Five are found on separate islands; five of them on the volcanoes of Isabela Island. Several of the surviving subspecies are seriously endangered. A 13th subspecies, '' C. n. abingdonii'' from

Quoy &

Quoy &

Harlan, 1827 (''nomen dubium'') * ''Testudo nigrita''

Duméril and

Williams, 1952 * ''Geochelone'' (''Chelonoidis'') ''elephantopus''

Pritchard, 1967 * ''Chelonoidis elephantopus''

Bour, 1980 ''C. n. nigra'' (

Quoy &

Quoy &

GĂ¼nther, 1875 (partim, misidentified type specimen once erroneously attributed to what is now ''C. n. duncanensis'') * ''Testudo abingdoni''

GĂ¼nther, 1877 ''C. n. becki'' * ''Testudo becki''

Van Denburgh, 1907 ''C. n. darwini'' * ''Testudo wallacei''

Van Denburgh, 1907 ''C. n. duncanensis'' * ''Testudo ephippium''

GĂ¼nther, 1875 (''partim'', misidentified type) * ''Geochelone nigra duncanensis''

Van Denburgh, 1907 ''C. n. phantastica'' * ''Testudo phantasticus''

Van Denburgh, 1907 ''C. n. porteri'' * ''Testudo nigrita''

Duméril and

GĂ¼nther, 1875 * ''Testudo vicina''

GĂ¼nther, 1875 * ''Testudo gĂ¼ntheri''

De Sola, R. 1930 (''nomen nudum'') ; '' Chelonoidis nigra nigra'' * ''Testudo nigra'' Quoy & Gaimard, 1824 * ''Testudo californiana'' Quoy & Gaimard, 1824 * ''Testudo galapagoensis'' Baur, 1889 * ''Testudo elephantopus galapagoensis'' Mertens & Wermuth, 1955 * ''Geochelone elephantopus galapagoensis'' Pritchard, 1967 * ''Chelonoidis galapagoensis'' Bour, 1980 * ''Chelonoidis nigra'' Bour, 1985 * ''Chelonoidis elephantopus galapagoensis'' Obst, 1985 * ''Geochelone nigra'' Pritchard, 1986 * ''Geochelone nigra nigra'' Stubbs, 1989 * ''Chelonoidis nigra galapagoensis'' David, 1994 * ''Chelonoidis nigra nigra'' David, 1994 * ''Geochelone elephantopus nigra'' Bonin, Devaux & Dupré, 1996 * ''Testudo california'' Paull, 1998 (''

The Pinta Island subspecies (''C. n. abingdonii'', now extinct) has been found to be most closely related to the subspecies on the islands of San CristĂ³bal (''C. n. chathamensis'') and Española (''C. n. hoodensis'') which lie over 300 km (190 mi) away, rather than that on the neighbouring island of Isabela as previously assumed. This relationship is attributable to dispersal by the strong local current from San CristĂ³bal towards Pinta. This discovery informed further attempts to preserve the ''C. n. abingdonii'' lineage and the search for an appropriate mate for

The Pinta Island subspecies (''C. n. abingdonii'', now extinct) has been found to be most closely related to the subspecies on the islands of San CristĂ³bal (''C. n. chathamensis'') and Española (''C. n. hoodensis'') which lie over 300 km (190 mi) away, rather than that on the neighbouring island of Isabela as previously assumed. This relationship is attributable to dispersal by the strong local current from San CristĂ³bal towards Pinta. This discovery informed further attempts to preserve the ''C. n. abingdonii'' lineage and the search for an appropriate mate for

tortoise

Tortoises () are reptiles of the family Testudinidae of the order Testudines (Latin: ''tortoise''). Like other turtles, tortoises have a turtle shell, shell to protect from predation and other threats. The shell in tortoises is generally hard, ...

in the genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus com ...

''Chelonoidis

''Chelonoidis'' is a genus of turtles in the tortoise family erected by Leopold Fitzinger in 1835.

They are found in South America and the GalĂ¡pagos Islands, and formerly had a wide distribution in the West Indies.

The multiple subspecies of t ...

'' (which also contains three smaller species from mainland South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the southe ...

). It comprises 15 subspecies

In biological classification, subspecies is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics (morphology), but that can successfully interbreed. Not all species ...

(13 extant

Extant is the opposite of the word extinct. It may refer to:

* Extant hereditary titles

* Extant literature, surviving literature, such as ''Beowulf'', the oldest extant manuscript written in English

* Extant taxon, a taxon which is not extinct, ...

and 2 extinct

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

). It is the largest living species of tortoise

Tortoises () are reptiles of the family Testudinidae of the order Testudines (Latin: ''tortoise''). Like other turtles, tortoises have a turtle shell, shell to protect from predation and other threats. The shell in tortoises is generally hard, ...

, with some modern GalĂ¡pagos tortoises weighing up to . With lifespans in the wild of over 100 years, it is one of the longest-lived vertebrates

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () ( chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, ...

. Captive Galapagos tortoises can live up to 177 years. For example, a captive individual, Harriet, lived for at least 175 years. Spanish explorers, who discovered the islands in the 16th century, named them after the Spanish '' galĂ¡pago'', meaning "tortoise".

GalĂ¡pagos tortoises are native to seven of the GalĂ¡pagos Islands

The GalĂ¡pagos Islands (Spanish: , , ) are an archipelago of volcanic islands. They are distributed on each side of the equator in the Pacific Ocean, surrounding the centre of the Western Hemisphere, and are part of the Republic of Ecuador ...

. Shell

Shell may refer to:

Architecture and design

* Shell (structure), a thin structure

** Concrete shell, a thin shell of concrete, usually with no interior columns or exterior buttresses

** Thin-shell structure

Science Biology

* Seashell, a hard ou ...

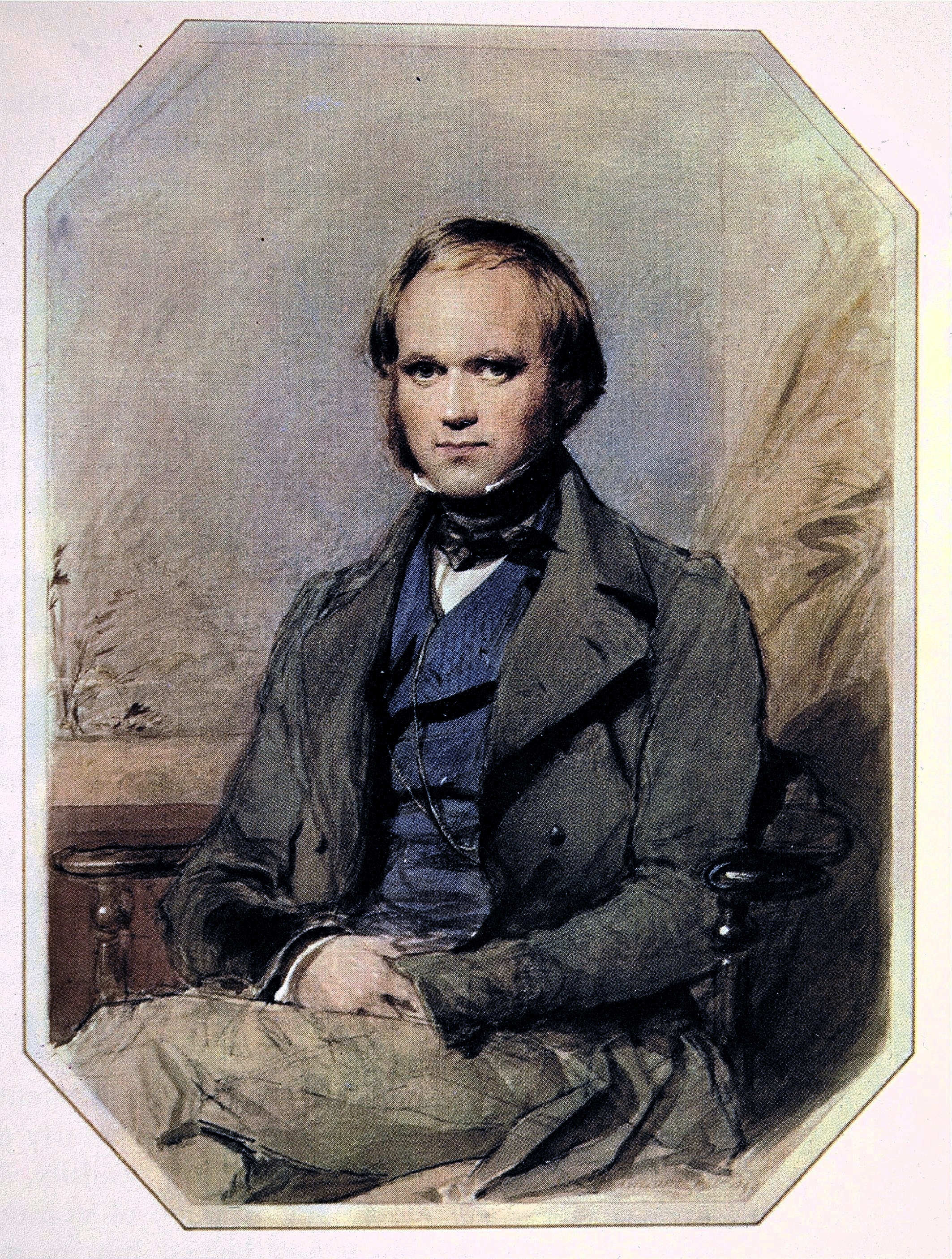

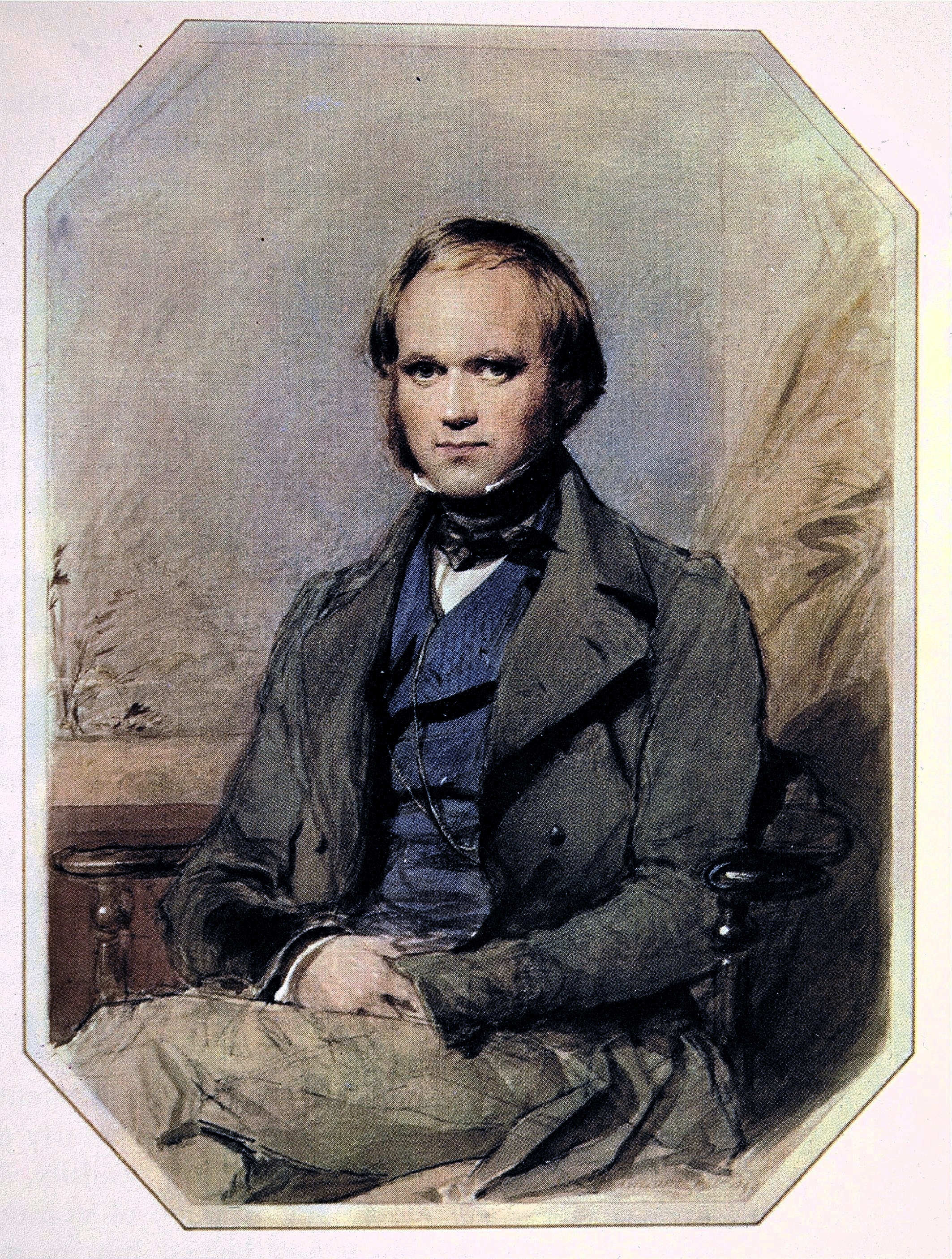

size and shape vary between subspecies and populations. On islands with humid highlands, the tortoises are larger, with domed shells and short necks; on islands with dry lowlands, the tortoises are smaller, with "saddleback" shells and long necks. Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

's observations of these differences on the second voyage of the ''Beagle'' in 1835, contributed to the development of his theory of evolution.

Tortoise numbers declined from over 250,000 in the 16th century to a low of around 15,000 in the 1970s. This decline was caused by overexploitation

Overexploitation, also called overharvesting, refers to harvesting a renewable resource to the point of diminishing returns. Continued overexploitation can lead to the destruction of the resource, as it will be unable to replenish. The term app ...

of the subspecies for meat and oil, habitat clearance for agriculture, and introduction of non-native animals to the islands, such as rats, goats, and pigs. The extinction of most giant tortoise lineages is thought to have also been caused by predation by humans or human ancestors, as the tortoises themselves have no natural predators. Tortoise populations on at least three islands have become extinct in historical times due to human activities. Specimens of these extinct taxa exist in several museums and also are being subjected to DNA analysis. 12 subspecies of the original 14-15 survive in the wild; a 13th subspecies ('' C. n. abingdonii'') had only a single known living individual, kept in captivity and nicknamed Lonesome George

Lonesome George ( es, Solitario George or , 1910 – June 24, 2012) was a male Pinta Island tortoise (''Chelonoidis niger abingdonii'') and the last known individual of the subspecies. In his last years, he was known as the rarest creat ...

until his death in June 2012. Two other subspecies, '' C. n. niger'' (the type subspecies of GalĂ¡pagos tortoise) from Floreana Island

Floreana Island (Spanish: ''Isla Floreana'') is an island of the GalĂ¡pagos Islands. It was named after Juan JosĂ© Flores, the first president of Ecuador, during whose administration the government of Ecuador took possession of the archipelago. ...

and an undescribed subspecies from Santa Fe Island

Santa Fe Island (Spanish: ''Isla Santa Fe''), also called Barrington Island after admiral Samuel Barrington, is a small island of which lies in the centre of the GalĂ¡pagos archipelago, to the south-east of Santa Cruz Island. Visitor access is ...

are known to have gone extinct in the mid-late 19th century. Conservation efforts, beginning in the 20th century, have resulted in thousands of captive-bred juveniles being released onto their ancestral home islands, and the total number of the subspecies is estimated to have exceeded 19,000 at the start of the 21st century. Despite this rebound, all surviving subspecies are classified as Threatened

Threatened species are any species (including animals, plants and fungi) which are vulnerable to endangerment in the near future. Species that are threatened are sometimes characterised by the population dynamics measure of ''critical depensat ...

by the International Union for Conservation of Nature

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN; officially International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natu ...

.

The GalĂ¡pagos tortoises are one of two insular radiations of giant tortoises that still survive to the modern day; the other is ''Aldabrachelys gigantea

The Aldabra giant tortoise (''Aldabrachelys gigantea'') is a species of tortoise in the family Testudinidae. The species is endemic to the islands of the Aldabra Atoll in the Seychelles. It is one of the largest tortoises in the world.Pritchar ...

'' of Aldabra

Aldabra is the world's second-largest coral atoll, lying south-east of the continent of Africa. It is part of the Aldabra Group of islands in the Indian Ocean that are part of the Outer Islands of the Seychelles, with a distance of 1,120 k ...

and the Seychelles

Seychelles (, ; ), officially the Republic of Seychelles (french: link=no, RĂ©publique des Seychelles; Creole: ''La Repiblik Sesel''), is an archipelagic state consisting of 115 islands in the Indian Ocean. Its capital and largest city, V ...

in the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by th ...

, east of Tanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands and ...

. While giant tortoise radiations were common in prehistoric times, humans have wiped out the majority of them worldwide; the only other radiation of tortoises to survive to historic times, ''Cylindraspis

''Cylindraspis'' is a genus of recently extinct giant tortoises. All of its species lived in the Mascarene Islands (Mauritius, Rodrigues and RĂ©union) in the Indian Ocean and all are now extinct due to hunting and introduction of non-native pre ...

'' of the Mascarenes

The Mascarene Islands (, ) or Mascarenes or Mascarenhas Archipelago is a group of islands in the Indian Ocean east of Madagascar consisting of the islands belonging to the Republic of Mauritius as well as the French department of RĂ©union. Their ...

, was driven to extinction by the 19th century, and other giant tortoise radiations such as a ''Centrochelys

''Centrochelys'' is a genus of tortoise. It contains one extant species and several extinct species:

* ''Centrochelys atlantica''

* ''Centrochelys burchardi''

* ''Centrochelys marocana''

* ''Centrochelys robusta''

* ''Centrochelys vulcanica''

* ...

'' radiation on the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to the African mainland, they are west of Morocc ...

and another ''Chelonoidis'' radiation in the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la CaraĂ¯be; ht, Karayib; nl, De CaraĂ¯ben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

were driven to extinction prior to that.

Taxonomy

Early classification

The GalĂ¡pagos Islands were discovered in 1535, but first appeared on the maps, ofGerardus Mercator

Gerardus Mercator (; 5 March 1512 – 2 December 1594) was a 16th-century geographer, cosmographer and Cartography, cartographer from the County of Flanders. He is most renowned for creating the Mercator 1569 world map, 1569 world map based on ...

and Abraham Ortelius

Abraham Ortelius (; also Ortels, Orthellius, Wortels; 4 or 14 April 152728 June 1598) was a Brabantian cartographer, geographer, and cosmographer, conventionally recognized as the creator of the first modern atlas, the ''Theatrum Orbis Terraru ...

, around 1570. The islands were named "Insulae de los Galopegos" (Islands of the Tortoises) in reference to the giant tortoises found there.The first navigation chart showing the individual islands was drawn up by the pirate Ambrose Cowley

William Ambrosia Cowley was a 17th-century English people, English buccaneer who surveyed the GalĂ¡pagos Islands during his circumnavigation of the world while serving under several Captains such as John Eaton (pirate), John Eaton, John Cook (pir ...

in 1684. He named them after fellow pirates or English noblemen. More recently, the Ecuadorian government gave most of the islands Spanish names. While the Spanish names are official, many researchers continue to use the older English names, particularly as those were the names used when Darwin visited. This article uses the Spanish island names.

Initially, the giant tortoises of the Indian Ocean and those from the GalĂ¡pagos were thought to be the same subspecies. Naturalists thought that sailors had transported the tortoises there. In 1676, the pre-Linnaean authority Claude Perrault

Claude Perrault (25 September 1613 – 9 October 1688) was a French physician and an amateur architect, best known for his participation in the design of the east façade of the Louvre in Paris.Johann Gottlob Schneider

Johann Gottlob Theaenus Schneider (18 January 1750 – 12 January 1822) was a German Empire, German classicist and natural history, naturalist.

Biography

Schneider was born at Collm in Saxony. In 1774, on the recommendation of Christian Gottlob ...

classified all giant tortoises as ''Testudo indica'' ("Indian tortoise"). In 1812, August Friedrich Schweigger

August Friedrich Schweigger (8 September 1783 – 28 June 1821) was a German naturalist born in Erlangen. He was the younger brother of scientist Johann Salomo Christoph Schweigger (1779-1857).

He studied medicine, zoology and botany at Erl ...

named them ''Testudo gigantea'' ("gigantic tortoise"). In 1834, André Marie Constant Duméril

André Marie Constant Duméril (1 January 1774 – 14 August 1860) was a French zoologist. He was professor of anatomy at the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle from 1801 to 1812, when he became professor of herpetology and ichthyology. His ...

and Gabriel Bibron

Gabriel Bibron (20 October 1805 – 27 March 1848) was a French zoologist and herpetologist. He was born in Paris. The son of an employee of the Museum national d'histoire naturelle, he had a good foundation in natural history and was hir ...

classified the GalĂ¡pagos tortoises as a separate subspecies, which they named ''Testudo nigrita'' ("black tortoise").

Recognition of subpopulations

The first systematic survey of giant tortoises was by the zoologistAlbert GĂ¼nther

Albert Karl Ludwig Gotthilf GĂ¼nther FRS, also Albert Charles Lewis Gotthilf GĂ¼nther (3 October 1830 – 1 February 1914), was a German-born British zoologist, ichthyologist, and herpetologist. GĂ¼nther is ranked the second-most productive re ...

of the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

, in 1875. GĂ¼nther identified at least five distinct populations from the GalĂ¡pagos, and three from the Indian Ocean islands. He expanded the list in 1877 to six from the GalĂ¡pagos, four from the Seychelles

Seychelles (, ; ), officially the Republic of Seychelles (french: link=no, RĂ©publique des Seychelles; Creole: ''La Repiblik Sesel''), is an archipelagic state consisting of 115 islands in the Indian Ocean. Its capital and largest city, V ...

, and four from the Mascarenes

The Mascarene Islands (, ) or Mascarenes or Mascarenhas Archipelago is a group of islands in the Indian Ocean east of Madagascar consisting of the islands belonging to the Republic of Mauritius as well as the French department of RĂ©union. Their ...

. GĂ¼nther hypothesized that all the giant tortoises descended from a single ancestral population which spread by sunken land bridge

In biogeography, a land bridge is an isthmus or wider land connection between otherwise separate areas, over which animals and plants are able to cross and Colonisation (biology), colonize new lands. A land bridge can be created by marine regre ...

s. This hypothesis was later disproven by the understanding that the GalĂ¡pagos, the atolls of Seychelles, and the Mascarene islands are all of recent volcanic origin and have never been linked to a continent by land bridges. GalĂ¡pagos tortoises are now thought to have descended from a South American ancestor, while the Indian Ocean tortoises derived from ancestral populations on Madagascar.

At the end of the 19th century, Georg Baur

Georg Baur (1859–1898) was a German vertebrate paleontologist and Neo-Lamarckian who studied reptiles of the Galapagos Islands, particularly the GalĂ¡pagos tortoises, in the 1890s. He is perhaps best known for his subsidence theory of the o ...

and Walter Rothschild

Lionel Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild, Baron de Rothschild, (8 February 1868 – 27 August 1937) was a British banker, politician, zoologist and soldier, who was a member of the Rothschild family. As a Zionist leader, he was present ...

recognised five more populations of GalĂ¡pagos tortoise. In 1905–06, an expedition by the California Academy of Sciences

The California Academy of Sciences is a research institute and natural history museum in San Francisco, California, that is among the largest museums of natural history in the world, housing over 46 million specimens. The Academy began in 1853 ...

, with Joseph R. Slevin in charge of reptiles, collected specimens which were studied by Academy herpetologist John Van Denburgh

John Van Denburgh (August 23, 1872 – October 24, 1924) was an American herpetologist from California (who also used the name Van Denburgh in publications, hence this name is used below).

Biography

Van Denburgh was born in San Francisco and enr ...

. He identified four additional populations, and proposed the existence of 15 subspecies. Van Denburgh's list still guides the taxonomy

Taxonomy is the practice and science of categorization or classification.

A taxonomy (or taxonomical classification) is a scheme of classification, especially a hierarchical classification, in which things are organized into groups or types. ...

of the GalĂ¡pagos tortoise, though now 10 populations are thought to have existed.

Current species and genus names

The current specific designation of ''niger'', formerly feminized to ''nigra'' ("black" – Quoy &Gaimard

Joseph Paul Gaimard (31 January 1793 – 10 December 1858) was a French naval surgeon and naturalist.

Biography

Gaimard was born at Saint-Zacharie on January 31, 1793. He studied medicine at the naval medical school in Toulon, subsequent ...

, 1824b) was resurrected in 1984 after it was discovered to be the senior synonym

A synonym is a word, morpheme, or phrase that means exactly or nearly the same as another word, morpheme, or phrase in a given language. For example, in the English language, the words ''begin'', ''start'', ''commence'', and ''initiate'' are all ...

(an older taxonomic synonym taking historical precedence) for the then commonly used subspecies name of ''elephantopus'' ("elephant-footed" – Harlan, 1827). Quoy and Gaimard's Latin description explains the use of ''nigra: "Testudo toto corpore nigro"'' means "tortoise with completely black body". Quoy and Gairmard described ''nigra'' from a living specimen, but no evidence indicates they knew of its accurate provenance within the GalĂ¡pagos – the locality was in fact given as California. Garman proposed the linking of ''nigra'' with the extinct Floreana

Floreana Island (Spanish: ''Isla Floreana'') is an island of the GalĂ¡pagos Islands. It was named after Juan JosĂ© Flores, the first president of Ecuador, during whose administration the government of Ecuador took possession of the archipelago. ...

subspecies. Later, Pritchard deemed it convenient to accept this designation, despite its tenuousness, for minimal disruption to the already confused nomenclature of the subspecies. The even more senior subspecies synonym of ''californiana'' ("californian" – Quoy & Gaimard

Joseph Paul Gaimard (31 January 1793 – 10 December 1858) was a French naval surgeon and naturalist.

Biography

Gaimard was born at Saint-Zacharie on January 31, 1793. He studied medicine at the naval medical school in Toulon, subsequent ...

, 1824a) is considered a ''nomen oblitum

In zoological nomenclature, a ''nomen oblitum'' (plural: ''nomina oblita''; Latin for "forgotten name") is a disused scientific name which has been declared to be obsolete (figuratively 'forgotten') in favour of another 'protected' name.

In its p ...

'' ("forgotten name").

Previously, the GalĂ¡pagos tortoise was considered to belong to the genus ''Geochelone

''Geochelone'' is a genus of tortoises.

''Geochelone'' tortoises, which are also known as typical tortoises or terrestrial turtles, can be found in southern Asia. They primarily eat plants. Species

The genus consists of two extant species:

A n ...

'', known as 'typical tortoises' or 'terrestrial turtles'. In the 1990s, subgenus ''Chelonoidis

''Chelonoidis'' is a genus of turtles in the tortoise family erected by Leopold Fitzinger in 1835.

They are found in South America and the GalĂ¡pagos Islands, and formerly had a wide distribution in the West Indies.

The multiple subspecies of t ...

'' was elevated to generic status based on phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek φυλή/ φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups o ...

evidence which grouped the South American members of ''Geochelone'' into an independent clade

A clade (), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that are monophyletic – that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants – on a phylogenetic tree. Rather than the English term, ...

(branch of the tree of life

The tree of life is a fundamental archetype in many of the world's mythological, religious, and philosophical traditions. It is closely related to the concept of the sacred tree.Giovino, Mariana (2007). ''The Assyrian Sacred Tree: A History ...

). This nomenclature has been adopted by several authorities.Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group. (2016). ''Chelonoidis nigra''. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species

Subspecies

Pinta Island

Pinta Island (Spanish: ''Isla Pinta''), also known as Abingdon Island, after the Earl of Abingdon, is an island located in the GalĂ¡pagos Islands group, Ecuador. It has an area of and a maximum altitude of .

Pinta was the original home to Lones ...

, is extinct

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

since 2012. The last known specimen, named Lonesome George

Lonesome George ( es, Solitario George or , 1910 – June 24, 2012) was a male Pinta Island tortoise (''Chelonoidis niger abingdonii'') and the last known individual of the subspecies. In his last years, he was known as the rarest creat ...

, died in captivity on 24 June 2012; George had been mated with female tortoises of several other subspecies, but none of the eggs from these pairings hatched. The subspecies inhabiting Floreana Island

Floreana Island (Spanish: ''Isla Floreana'') is an island of the GalĂ¡pagos Islands. It was named after Juan JosĂ© Flores, the first president of Ecuador, during whose administration the government of Ecuador took possession of the archipelago. ...

(''G. niger'') is thought to have been hunted to extinction by 1850, only 15 years after Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

's landmark visit of 1835, when he saw shells, but no live tortoises there. However, recent DNA testing shows that an intermixed, non-native population currently existing on the island of Isabela is of genetic resemblance to the subspecies native to Floreana, suggesting that ''G. niger'' has not gone entirely extinct. The existence of the '' C. n. phantastica'' subspecies of Fernandina Island

Fernandina Island (Spanish: ''Isla Fernandina'', named after King Ferdinand of Spain, the sponsor of Christopher Columbus) (formerly known in English as Narborough Island, after John Narborough) is the third largest, and youngest, island of the ...

was disputed, as it was described from a single specimen that may have been an artificial introduction to the island; however, a live female was found in 2019, likely confirming the subspecies' validity.

Prior to widespread knowledge of the differences between the populations (sometimes called races) from different islands and volcanoes, captive collections in zoos were indiscriminately mixed. Fertile offspring resulted from pairings of animals from different races. However, captive crosses between tortoises from different races have lower fertility and higher mortality than those between tortoises of the same race, and captives in mixed herds normally direct courtship only toward members of the same race.

The valid scientific names of each of the individual populations are not universally accepted, and some researchers still consider each subspecies to be distinct species. Prior to 2021, all subspecies were classified as distinct species from one another, but a 2021 study analyzing the level of divergence within the extinct West Indian ''Chelonoidis'' radiation and comparing it to the GalĂ¡pagos radiation found that the level of divergence within both clades may have been significantly overestimated, and supported once again reclassifying all GalĂ¡pagos tortoises as subspecies of a single subspecies, ''C. niger''. This was followed by the Turtle Taxonomy Working Group The Turtle Taxonomy Working Group (TTWG) is an informal working group of the IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group (TFTSG). It is composed of a number of leading turtle taxonomists, with varying participation by individual partici ...

and the Reptile Database

The Reptile Database is a scientific database that collects taxonomic information on all living reptile species (i.e. no fossil species such as dinosaurs). The database focuses on species (as opposed to higher ranks such as families) and has entrie ...

later that year. The taxonomic status of the various races is not fully resolved.

* ''Testudo californiana'' Quoy &

Gaimard

Joseph Paul Gaimard (31 January 1793 – 10 December 1858) was a French naval surgeon and naturalist.

Biography

Gaimard was born at Saint-Zacharie on January 31, 1793. He studied medicine at the naval medical school in Toulon, subsequent ...

, 1824a (''nomen oblitum'')

* ''Testudo nigra'' Quoy &

Gaimard

Joseph Paul Gaimard (31 January 1793 – 10 December 1858) was a French naval surgeon and naturalist.

Biography

Gaimard was born at Saint-Zacharie on January 31, 1793. He studied medicine at the naval medical school in Toulon, subsequent ...

, 1824b (''nomen novum'')

* ''Testudo elephantopus'' Harlan, 1827 (''nomen dubium'') * ''Testudo nigrita''

Duméril and

Bibron

Gabriel Bibron (20 October 1805 – 27 March 1848) was a French zoologist and herpetologist. He was born in Paris. The son of an employee of the Museum national d'histoire naturelle, he had a good foundation in natural history and was hir ...

, 1834 (''nomen dubium'')

* ''Testudo planiceps'' Gray

Grey (more common in British English) or gray (more common in American English) is an intermediate color between black and white. It is a neutral or achromatic color, meaning literally that it is "without color", because it can be composed o ...

, 1853 (''nomen dubium'')

* ''Testudo clivosa'' Garman Garman is a surname or first name. Notable people with the name include:

Sports

* Ann Garman, All-American Girls Professional Baseball League player

* Judi Garman (born 1954), American softball coach

* Mike Garman (born 1949), American baseball pla ...

, 1917 (''nomen dubium'')

* ''Testudo typica'' Garman Garman is a surname or first name. Notable people with the name include:

Sports

* Ann Garman, All-American Girls Professional Baseball League player

* Judi Garman (born 1954), American softball coach

* Mike Garman (born 1949), American baseball pla ...

, 1917 (''nomen dubium'')

* ''Testudo'' (''Chelonoidis'') ''elephantopus'' Williams, 1952 * ''Geochelone'' (''Chelonoidis'') ''elephantopus''

Pritchard, 1967 * ''Chelonoidis elephantopus''

Bour, 1980 ''C. n. nigra'' (

nominate subspecies

In biological classification, subspecies is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics (morphology), but that can successfully interbreed. Not all species ...

)

* ''Testudo californiana'' Quoy &

Gaimard

Joseph Paul Gaimard (31 January 1793 – 10 December 1858) was a French naval surgeon and naturalist.

Biography

Gaimard was born at Saint-Zacharie on January 31, 1793. He studied medicine at the naval medical school in Toulon, subsequent ...

, 1824a (''nomen oblitum'')

* ''Testudo nigra'' Quoy &

Gaimard

Joseph Paul Gaimard (31 January 1793 – 10 December 1858) was a French naval surgeon and naturalist.

Biography

Gaimard was born at Saint-Zacharie on January 31, 1793. He studied medicine at the naval medical school in Toulon, subsequent ...

, 1824b (''nomen novum'')

* ''Testudo galapagoensis'' Baur Baur can refer to:

People

* A. C. Baur (1900–1931), American football player and stock broker

* Alfred Baur, Swiss collector of Asian art

* Eleonore Baur, only woman to participate in Munich Beer Hall Putsch

* Erwin Baur, German geneticist and b ...

1889

''C. n. abingdoni''

* ''Testudo ephippium''GĂ¼nther, 1875 (partim, misidentified type specimen once erroneously attributed to what is now ''C. n. duncanensis'') * ''Testudo abingdoni''

GĂ¼nther, 1877 ''C. n. becki'' * ''Testudo becki''

Rothschild

Rothschild () is a name derived from the German ''zum rothen Schild'' (with the old spelling "th"), meaning "with the red sign", in reference to the houses where these family members lived or had lived. At the time, houses were designated by sign ...

, 1901

''C. n. chathamensis''

* ''Testudo wallacei''Rothschild

Rothschild () is a name derived from the German ''zum rothen Schild'' (with the old spelling "th"), meaning "with the red sign", in reference to the houses where these family members lived or had lived. At the time, houses were designated by sign ...

1902 (''partim'', ''nomen dubium'')

* ''Testudo chathamensis''Van Denburgh, 1907 ''C. n. darwini'' * ''Testudo wallacei''

Rothschild

Rothschild () is a name derived from the German ''zum rothen Schild'' (with the old spelling "th"), meaning "with the red sign", in reference to the houses where these family members lived or had lived. At the time, houses were designated by sign ...

1902 (''partim'', ''nomen dubium'')

* ''Testudo darwini''Van Denburgh, 1907 ''C. n. duncanensis'' * ''Testudo ephippium''

GĂ¼nther, 1875 (''partim'', misidentified type) * ''Geochelone nigra duncanensis''

Garman Garman is a surname or first name. Notable people with the name include:

Sports

* Ann Garman, All-American Girls Professional Baseball League player

* Judi Garman (born 1954), American softball coach

* Mike Garman (born 1949), American baseball pla ...

, 1917 in Pritchard, 1996(''nomen nudum'')

''C. n. hoodensis''

* ''Testudo hoodensis''Van Denburgh, 1907 ''C. n. phantastica'' * ''Testudo phantasticus''

Van Denburgh, 1907 ''C. n. porteri'' * ''Testudo nigrita''

Duméril and

Bibron

Gabriel Bibron (20 October 1805 – 27 March 1848) was a French zoologist and herpetologist. He was born in Paris. The son of an employee of the Museum national d'histoire naturelle, he had a good foundation in natural history and was hir ...

, 1834 (''nomen dubium'')

* ''Testudo porteri''Rothschild

Rothschild () is a name derived from the German ''zum rothen Schild'' (with the old spelling "th"), meaning "with the red sign", in reference to the houses where these family members lived or had lived. At the time, houses were designated by sign ...

, 1903

''C. n. vicina''

* ''Testudo microphyes''GĂ¼nther, 1875 * ''Testudo vicina''

GĂ¼nther, 1875 * ''Testudo gĂ¼ntheri''

Baur Baur can refer to:

People

* A. C. Baur (1900–1931), American football player and stock broker

* Alfred Baur, Swiss collector of Asian art

* Eleonore Baur, only woman to participate in Munich Beer Hall Putsch

* Erwin Baur, German geneticist and b ...

, 1889

* ''Testudo macrophyes''Garman Garman is a surname or first name. Notable people with the name include:

Sports

* Ann Garman, All-American Girls Professional Baseball League player

* Judi Garman (born 1954), American softball coach

* Mike Garman (born 1949), American baseball pla ...

, 1917

* ''Testudo vandenburghi''De Sola, R. 1930 (''nomen nudum'') ; '' Chelonoidis nigra nigra'' * ''Testudo nigra'' Quoy & Gaimard, 1824 * ''Testudo californiana'' Quoy & Gaimard, 1824 * ''Testudo galapagoensis'' Baur, 1889 * ''Testudo elephantopus galapagoensis'' Mertens & Wermuth, 1955 * ''Geochelone elephantopus galapagoensis'' Pritchard, 1967 * ''Chelonoidis galapagoensis'' Bour, 1980 * ''Chelonoidis nigra'' Bour, 1985 * ''Chelonoidis elephantopus galapagoensis'' Obst, 1985 * ''Geochelone nigra'' Pritchard, 1986 * ''Geochelone nigra nigra'' Stubbs, 1989 * ''Chelonoidis nigra galapagoensis'' David, 1994 * ''Chelonoidis nigra nigra'' David, 1994 * ''Geochelone elephantopus nigra'' Bonin, Devaux & Dupré, 1996 * ''Testudo california'' Paull, 1998 (''

ex errore

This is a list of terms and symbols used in scientific names for organisms, and in describing the names. For proper parts of the names themselves, see List of Latin and Greek words commonly used in systematic names. Note that many of the abbreviat ...

'')

* ''Testudo californianana'' Paull, 1999 (''ex errore'')

; ''Chelonoidis nigra abingdonii

The Pinta Island tortoise (''Chelonoidis niger ''), also known as the Pinta giant tortoise, Abingdon Island tortoise, or Abingdon Island giant tortoise, was a subspecies of GalĂ¡pagos tortoise native to Ecuador's Pinta Island.

The subspecies wa ...

''

* ''Testudo ephippium'' GĂ¼nther, 1875

* ''Testudo abingdonii'' GĂ¼nther, 1877

* ''Testudo abingdoni'' Van Denburgh, 1914 (''ex errore'')

* ''Testudo elephantopus abingdonii'' Mertens & Wermuth, 1955

* ''Testudo elephantopus ephippium'' Mertens & Wermuth, 1955

* ''Geochelone abingdonii'' Pritchard, 1967

* ''Geochelone elephantopus abingdoni'' Pritchard, 1967

* ''Geochelone elephantopus ephippium'' Pritchard, 1967

* ''Geochelone ephippium'' Pritchard, 1967

* ''Chelonoidis abingdonii'' Bour, 1980

* ''Chelonoidis ephippium'' Bour, 1980

* ''Geochelone elephantopus abingdonii'' Groombridge, 1982

* ''Geochelone abingdoni'' Fritts, 1983

* ''Geochelone epphipium'' Fritts, 1983 (''ex errore'')

* ''Chelonoidis nigra ephippium'' Pritchard, 1984

* ''Chelonoidis elephantopus abingdoni'' Obst, 1985

* ''Chelonoidis elephantopus ephippium'' Obst, 1985

* ''Geochelone nigra abingdoni'' Stubbs, 1989

* ''Chelonoidis nigra abingdonii'' David, 1994

* ''Chelonoidis elephantopus abingdonii'' Rogner, 1996

* ''Chelonoidis nigra abingdonii'' Bonin, Devaux & Dupré, 1996

* ''Chelonoidis nigra abdingdonii'' Obst, 1996 (''ex errore'')

* ''Geochelone abdingdonii'' Obst, 1996

* ''Geochelone nigra abdingdoni'' Obst, 1996 (''ex errore'')

* ''Geochelone nigra ephyppium'' Caccone, Gibbs, Ketmaier, Suatoni & Powell, 1999 (''ex errore'')

* ''Chelonoidis nigra ahingdonii'' Artner, 2003 (''ex errore'')

* ''Chelonoidis abingdoni'' Joseph-Ouni, 2004

; '' Chelonoidis nigra becki''

* ''Testudo becki'' Rothschild, 1901

* ''Testudo bedsi'' Heller, 1903 (''ex errore'')

* ''Geochelone becki'' Pritchard, 1967

* ''Geochelone elephantopus becki'' Pritchard, 1967

* ''Chelonoidis becki'' Bour, 1980

* ''Chelonoidis elephantopus becki'' Obst, 1985

* ''Chelonoidis nigra beckii'' David, 1994 (''ex errore'')

* ''Chelonoidis elephantopus beckii'' Rogner, 1996

* ''Chelonoidis nigra becki'' Obst, 1996

; ''Chelonoidis nigra chathamensis

''Chelonoidis'' is a genus of turtles in the tortoise family erected by Leopold Fitzinger in 1835.

They are found in South America and the GalĂ¡pagos Islands, and formerly had a wide distribution in the West Indies.

The multiple subspecies of t ...

''

* ''Testudo wallacei'' Rothschild, 1902

* ''Testudo chathamensis'' Van Denburgh, 1907

* ''Testudo elephantopus chathamensis'' Mertens & Wermuth, 1955

* ''Testudo elephantopus wallacei'' Mertens & Wermuth, 1955

* ''Testudo chatamensis'' Slevin & Leviton, 1956 (''ex errore'')

* ''Geochelone chathamensis'' Pritchard, 1967

* ''Geochelone elephantopus chathamensis'' Pritchard, 1967

* ''Geochelone elephantopus wallacei'' Pritchard, 1967

* ''Geochelone wallacei'' Pritchard, 1967

* ''Chelonoidis chathamensis'' Bour, 1980

* ''Chelonoidis elephantopus chathamensis'' Obst, 1985

* ''Chelonoidis elephantopus wallacei'' Obst, 1985

* ''Chelonoidis elephantopus chatamensis'' Gosławski & Hryniewicz, 1993

* ''Chelonoidis nigra chathamensis'' David, 1994

* ''Chelonoidis nigra wallacei'' Bonin, Devaux & Dupré, 1996

* ''Geochelone cathamensis'' Obst, 1996 (''ex errore'')

* ''Geochelone elephantopus chatamensis'' Paull, 1996

* ''Testudo chathamensis chathamensis'' Pritchard, 1998

* ''Cherlonoidis nigra wallacei'' Wilms, 1999

* ''Geochelone nigra chatamensis'' Caccone, Gibbs, Ketmaier, Suatoni & Powell, 1999

* ''Geochelone nigra wallacei'' Chambers, 2004

; '' Chelonoidis nigra darwini''

* ''Testudo wallacei'' Rothschild, 1902

* ''Testudo darwini'' Van Denburgh, 1907

* ''Testudo elephantopus darwini'' Mertens & Wermuth, 1955

* ''Testudo elephantopus wallacei'' Mertens & Wermuth, 1955

* ''Geochelone darwini'' Pritchard, 1967

* ''Geochelone elephantopus darwini'' Pritchard, 1967

* ''Geochelone elephantopus wallacei'' Pritchard, 1967

* ''Geochelone wallacei'' Pritchard, 1967

* ''Chelonoidis darwini'' Bour, 1980

* ''Chelonoidis elephantopus darwini'' Obst, 1985

* ''Chelonoidis elephantopus wallacei'' Obst, 1985

* ''Chelonoidis nigra darwinii'' David, 1994 (''ex errore'')

* ''Chelonoidis elephantopus darwinii'' Rogner, 1996

* ''Chelonoidis nigra darwini'' Bonin, Devaux & Dupré, 1996

* ''Chelonoidis nigra wallacei'' Bonin, Devaux & Dupré, 1996

* ''Cherlonoidis nigra wallacei'' Wilms, 1999

* ''Geochelone nigra darwinii'' Ferri, 2002

* ''Geochelone nigra wallacei'' Chambers, 2004

; '' Chelonoidis nigra duncanensis''

* ''Testudo duncanensis'' Garman, 1917 (''nomen nudum

In taxonomy, a ''nomen nudum'' ('naked name'; plural ''nomina nuda'') is a designation which looks exactly like a scientific name of an organism, and may have originally been intended to be one, but it has not been published with an adequate descr ...

'')

* ''Geochelone nigra duncanensis'' Stubbs, 1989

* ''Geochelone nigra duncanensis'' Garman, 1996

* ''Chelonoidis nigra duncanensis'' Artner, 2003

* ''Chelonoidis duncanensis'' Joseph-Ouni, 2004

; '' Chelonoidis nigra hoodensis''

* ''Testudo hoodensis'' Van Denburgh, 1907

* ''Testudo elephantopus hoodensis'' Mertens & Wermuth, 1955

* ''Geochelone elephantopus hoodensis'' Pritchard, 1967

* ''Geochelone hoodensis'' Pritchard, 1967

* ''Chelonoidis hoodensis'' Bour, 1980

* ''Chelonoidis elephantopus hoodensis'' Obst, 1985

* ''Chelonoidis nigra hoodensis'' David, 1994

; '' Chelonoidis nigra phantastica''

* ''Testudo phantasticus'' Van Denburgh, 1907

* ''Testudo phantastica'' Siebenrock, 1909

* ''Testudo elephantopus phantastica'' Mertens & Wermuth, 1955

* ''Geochelone elephantopus phantastica'' Pritchard, 1967

* ''Geochelone phantastica'' Pritchard, 1967

* ''Chelonoidis phantastica'' Bour, 1980

* ''Geochelone phantasticus'' Crumly, 1984

* ''Chelonoidis elephantopus phantastica'' Obst, 1985

* ''Chelonoidis nigra phantastica'' David, 1994

; ''Chelonoidis nigra porteri

''Chelonoidis'' is a genus of turtles in the tortoise family erected by Leopold Fitzinger in 1835.

They are found in South America and the GalĂ¡pagos Islands, and formerly had a wide distribution in the West Indies.

The multiple subspecies of ...

''

* ''Testudo nigrita'' Duméril & Bibron, 1835

* ''Testudo porteri'' Rothschild, 1903

* ''Testudo elephantopus nigrita'' Mertens & Wermuth, 1955

* ''Geochelone elephantopus porteri'' Pritchard, 1967

* ''Geochelone nigrita'' Pritchard, 1967

* ''Chelonoidis nigrita'' Bour, 1980

* ''Geochelone elephantopus nigrita'' Honegger, 1980

* ''Geochelone porteri'' Fritts, 1983

* ''Chelonoidis elephantopus nigrita'' Obst, 1985

* ''Geochelone nigra porteri'' Stubbs, 1989

* ''Chelonoidis elephantopus porteri'' Gosławski & Hryniewicz, 1993

* ''Chelonoidis nigra nigrita'' David, 1994

* ''Geochelone nigra perteri'' MĂ¼ller & Schmidt, 1995 (''ex errore'')

* ''Chelonoidis nigra porteri'' Bonin, Devaux & Dupré, 1996

; '' Chelonoidis nigra vicina''

* ''Testudo elephantopus'' Harlan, 1827

* ''Testudo microphyes'' GĂ¼nther, 1875

* ''Testudo vicina'' GĂ¼nther, 1875

* ''Testudo macrophyes'' Garman, 1917

* ''Testudo vandenburghi'' de Sola, 1930

* ''Testudo elephantopus elephantopus'' Mertens & Wermuth, 1955

* ''Geochelone elephantopus'' Williams, 1960

* ''Geochelone elephantopus elephantopus'' Pritchard, 1967

* ''Geochelone elephantopus guentheri'' Pritchard, 1967

* ''Geochelone elephantopus guntheri'' Pritchard, 1967 (''ex errore'')

* ''Geochelone elephantopus microphyes'' Pritchard, 1967

* ''Geochelone elephantopus vandenburgi'' Pritchard, 1967 (''ex errore'')

* ''Geochelone guntheri'' Pritchard, 1967

* ''Geochelone microphyes'' Pritchard, 1967

* ''Geochelone vandenburghi'' Pritchard, 1967

* ''Geochelone vicina'' Pritchard, 1967

* ''Geochelone elephantopus microphys'' Arnold, 1979 (''ex errore'')

* ''Geochelone elephantopus vandenburghi'' Pritchard, 1979

* ''Chelonoides elephantopus'' Obst, 1980

* ''Chelonoidis elephantopus'' Bour, 1980

* ''Chelonoidis guentheri'' Bour, 1980

* ''Chelonoidis microphyes'' Bour, 1980

* ''Chelonoidis vandenburghi'' Bour, 1980

* ''Geochelone guentheri'' Fritts, 1983

* ''Chelonoidis elephantopus elephantopus'' Obst, 1985

* ''Chelonoidis elephantopus guentheri'' Obst, 1985

* ''Chelonoidis elephantopus microphyes'' Obst, 1985

* ''Chelonoidis elephantopus vandenburghi'' Obst, 1985

* ''Geochelone elephantopus vicina'' Swingland, 1989

* ''Geochelone elephantopus vicini'' Swingland, 1989 (''ex errore'')

* ''Chelonoidis elephantopus guntheri'' Gosławski & Hryniewicz, 1993

* ''Chelonoidis nigra guentheri'' David, 1994

* ''Chelonoidis nigra microphyes'' David, 1994

* ''Chelonoidis nigra vandenburghi'' David, 1994

* ''Geochelone nigra elephantopus'' MĂ¼ller & Schmidt, 1995

* ''Chelonoidis elephantopus vicina'' Rogner, 1996

* ''Geochelone elephantopus vandenburghii'' Obst, 1996 (''ex errore'')

* ''Geochelone vandenburghii'' Obst, 1996

* ''Chelonoidis nigra microphyies'' Bonin, Devaux & Dupré, 1996 (''ex errore'')

* ''Geochelone elephantopus microphytes'' Paull, 1996 (''ex errore'')

* ''Geochelone elephantopus vandenbergi'' Paull, 1996 (''ex errore'')

* ''Testudo elephantopus guntheri'' Paull, 1999

* ''Chelonoidis nigra vicina'' Artner, 2003

* ''Chelonoidis vicina'' Joseph-Ouni, 2004

* ''Geochelone nigra guentheri'' Chambers, 2004

Evolutionary history

All subspecies of GalĂ¡pagos tortoises evolved from common ancestors that arrived from mainland South America by overwater dispersal. Genetic studies have shown that theChaco tortoise

The Chaco tortoise (''Chelonoidis chilensis''), also known commonly as the Argentine tortoise, the Patagonian tortoise, or the southern wood tortoise, is a species of tortoise in the family Testudinidae. The species is endemic to South America.

...

of Argentina and Paraguay is their closest living relative. The minimal founding population was a pregnant female or a breeding pair. Survival on the 1000-km oceanic journey is accounted for because the tortoises are buoyant, can breathe by extending their necks above the water, and are able to survive months without food or fresh water. As they are poor swimmers, the journey was probably a passive one facilitated by the Humboldt Current

The Humboldt Current, also called the Peru Current, is a cold, low- salinity ocean current that flows north along the western coast of South America.Montecino, Vivian, and Carina B. Lange. "The Humboldt Current System: Ecosystem components and pr ...

, which diverts westwards towards the GalĂ¡pagos Islands from the mainland. The ancestors of the genus ''Chelonoidis

''Chelonoidis'' is a genus of turtles in the tortoise family erected by Leopold Fitzinger in 1835.

They are found in South America and the GalĂ¡pagos Islands, and formerly had a wide distribution in the West Indies.

The multiple subspecies of t ...

'' are believed to have similarly dispersed from Africa to South America during the Oligocene

The Oligocene ( ) is a geologic epoch of the Paleogene Period and extends from about 33.9 million to 23 million years before the present ( to ). As with other older geologic periods, the rock beds that define the epoch are well identified but the ...

.

The closest living relative (though not a direct ancestor) of the GalĂ¡pagos giant tortoise is the Chaco tortoise

The Chaco tortoise (''Chelonoidis chilensis''), also known commonly as the Argentine tortoise, the Patagonian tortoise, or the southern wood tortoise, is a species of tortoise in the family Testudinidae. The species is endemic to South America.

...

(''Chelonoidis chilensis''), a much smaller subspecies from South America. The divergence between ''C. chilensis'' and ''C. niger'' probably occurred 11.95–25 million years ago, an evolutionary event preceding the volcanic formation of the oldest modern GalĂ¡pagos Islands 5 million years ago. Mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA or mDNA) is the DNA located in mitochondria, cellular organelles within eukaryotic cells that convert chemical energy from food into a form that cells can use, such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial D ...

analysis indicates that the oldest existing islands (Española and San CristĂ³bal) were colonised first, and that these populations seeded the younger islands via dispersal in a "stepping stone" fashion via local currents. Restricted gene flow

In population genetics, gene flow (also known as gene migration or geneflow and allele flow) is the transfer of genetic material from one population to another. If the rate of gene flow is high enough, then two populations will have equivalent a ...

between isolated islands then resulted in the independent evolution of the populations into the divergent forms observed in the modern subspecies. The evolutionary relationships between the subspecies thus echo the volcanic history of the islands.

Subspecies

Modern DNA methods have revealed new information on the relationships between the subspecies: Isabela Island The five populations living on the largest island, Isabela, are the ones that are the subject of the most debate as to whether they are true subspecies or just distinct populations or subspecies. It is widely accepted that the population living on the northernmost volcano, Volcan Wolf, is genetically independent from the four populations to the south and is therefore a separate subspecies. It is thought to be derived from a different colonization event than the others. A colonization from the island of Santiago apparently gave rise to the Volcan Wolf subspecies (''C. n. becki'') while the four southern populations are believed to be descended from a second colonization from the more southerly island of Santa Cruz. Tortoises from Santa Cruz are thought to have first colonized the Sierra Negra volcano, which was the first of the island's volcanoes to form. The tortoises then spread north to each newly created volcano, resulting in the populations living on Volcan Alcedo and then Volcan Darwin. Recent genetic evidence shows that these two populations are genetically distinct from each other and from the population living on Sierra Negra (''C. guentheri'') and therefore form the subspecies ''C. n. vandenburghi'' (Alcedo) and ''C. n. microphyes'' (Darwin). The fifth population living on the southernmost volcano (''C. n. vicina'') is thought to have split off from the Sierra Negra population more recently and is therefore not as genetically different as the other two. Isabela is the most recently formed island tortoises inhabit, so its populations have had less time to evolve independently than populations on other islands, but according to some researchers, they are all genetically different and should each be considered as separate subspecies. Floreana Island Phylogenetic analysis may help to "resurrect" the extinct subspecies of Floreana (''C. n. niger'') – a subspecies known only fromsubfossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved in ...

remains. Some tortoises from Isabela were found to be a partial match for the genetic profile of Floreana specimens from museum collections, possibly indicating the presence of hybrids from a population transported by humans from Floreana to Isabela, resulting either from individuals deliberately transported between the islands, or from individuals thrown overboard from ships to lighten the load. Nine Floreana descendants have been identified in the captive population of the Fausto Llerena Breeding Center on Santa Cruz; the genetic footprint was identified in the genomes of hybrid offspring. This allows the possibility of re-establishing a reconstructed subspecies from selective breeding

Selective breeding (also called artificial selection) is the process by which humans use animal breeding and plant breeding to selectively develop particular phenotypic traits (characteristics) by choosing which typically animal or plant mal ...

of the hybrid animals. Furthermore, individuals from the subspecies possibly are still extant. Genetic analysis from a sample of tortoises from Volcan Wolf found 84 first-generation ''C. n. niger'' hybrids, some less than 15 years old. The genetic diversity of these individuals is estimated to have required 38 ''C. n. niger'' parents, many of which could still be alive on Isabela Island.

Pinta Island

The Pinta Island subspecies (''C. n. abingdonii'', now extinct) has been found to be most closely related to the subspecies on the islands of San CristĂ³bal (''C. n. chathamensis'') and Española (''C. n. hoodensis'') which lie over 300 km (190 mi) away, rather than that on the neighbouring island of Isabela as previously assumed. This relationship is attributable to dispersal by the strong local current from San CristĂ³bal towards Pinta. This discovery informed further attempts to preserve the ''C. n. abingdonii'' lineage and the search for an appropriate mate for

The Pinta Island subspecies (''C. n. abingdonii'', now extinct) has been found to be most closely related to the subspecies on the islands of San CristĂ³bal (''C. n. chathamensis'') and Española (''C. n. hoodensis'') which lie over 300 km (190 mi) away, rather than that on the neighbouring island of Isabela as previously assumed. This relationship is attributable to dispersal by the strong local current from San CristĂ³bal towards Pinta. This discovery informed further attempts to preserve the ''C. n. abingdonii'' lineage and the search for an appropriate mate for Lonesome George

Lonesome George ( es, Solitario George or , 1910 – June 24, 2012) was a male Pinta Island tortoise (''Chelonoidis niger abingdonii'') and the last known individual of the subspecies. In his last years, he was known as the rarest creat ...

, which had been penned with females from Isabela. Hope was bolstered by the discovery of a ''C. n. abingdonii'' hybrid male in the VolcĂ¡n Wolf population on northern Isabela, raising the possibility that more undiscovered living Pinta descendants exist.

Santa Cruz Island

Mitochondrial DNA studies of tortoises on Santa Cruz show up to three genetically distinct lineages found in nonoverlapping population distributions around the regions of Cerro Montura, Cerro Fatal, and La Caseta. Although traditionally grouped into a single subspecies (''C. n. porteri''), the lineages are all more closely related to tortoises on other islands than to each other: Cerro Montura tortoises are most closely related to ''C. n. duncanensis'' from PinzĂ³n, Cerro Fatal to ''C. n. chathamensis'' from San CristĂ³bal, and La Caseta to the four southern races of Isabela as well as Floreana tortoises.

In 2015, the Cerro Fatal tortoises were described as a distinct taxon, '' donfaustoi''. Prior to the identification of this subspecies through genetic analysis, it was noted that there existed differences in shells between the Cerro Fatal tortoises and other tortoises on Santa Cruz. By classifying the Cerro Fatal tortoises into a new taxon, greater attention can be paid to protecting its habitat, according to Adalgisa Caccone, who is a member of the team making this classification.

PinzĂ³n Island

When it was discovered that the central, small island of PinzĂ³n had only 100–200 very old adults and no young tortoises had survived into adulthood for perhaps more than 70 years, the resident scientists initiated what would eventually become the Giant Tortoise Breeding and Rearing Program. Over the next 50 years, this program resulted in major successes in the recovery of giant tortoise populations throughout the archipelago.

In 1965, the first tortoise eggs collected from natural nests on PinzĂ³n Island were brought to the Charles Darwin Research Station, where they would complete the period of incubation and then hatch, becoming the first young tortoises to be reared in captivity. The introduction of black rats onto PinzĂ³n sometime in the latter half of the 19th century had resulted in the complete eradication of all young tortoises. Black rats had been eating both tortoise eggs and hatchlings, effectively destroying the future of the tortoise population. Only the longevity of giant tortoises allowed them to survive until the GalĂ¡pagos National Park, Island Conservation

Island Conservation is a non-profit organization with the mission to prevent extinctions by removing invasive species from islands. Island Conservation has therefore focused its efforts on islands with species categorized as Critically Endangere ...

, Charles Darwin Foundation, the Raptor Center, and Bell Laboratories removed invasive rats in 2012. In 2013, heralding an important step in PinzĂ³n tortoise recovery, hatchlings emerged from native PinzĂ³n tortoise nests on the island and the GalĂ¡pagos National Park successfully returned 118 hatchlings to their native island home. Partners returned to PinzĂ³n Island in late 2014 and continued to observe hatchling tortoises (now older), indicating that natural recruitment is occurring on the island unimpeded. They also discovered a snail subspecies new to science. These exciting results highlight the conservation value of this important management action. In early 2015, after extensive monitoring, partners confirmed that PinzĂ³n and Plaza Sur Islands are now both rodent-free.

Española

On the southern island of Española, only 14 adult tortoises were found, two males and 12 females. The tortoises apparently were not encountering one another, so no reproduction was occurring. Between 1963 and 1974, all 14 adult tortoises discovered on the island were brought to the tortoise center on Santa Cruz and a tortoise breeding program was initiated. In 1977, a third Española male tortoise was returned to Galapagos from the San Diego Zoo and joined the breeding group. After 40 years' work reintroducing captive animals, a detailed study of the island's ecosystem has confirmed it has a stable, breeding population. Where once 15 were known, now more than 1,000 giant tortoises inhabit the island of Española. One research team has found that more than half the tortoises released since the first reintroductions are still alive, and they are breeding well enough for the population to progress onward, unaided. In January 2020, it was widely reported that Diego, a 100-year-old male tortoise, resurrected 40% of the tortoise population on the island and is known as the "Playboy Tortoise".

Fernandina

The ''C. n. phantasticus'' subspecies from Fernandina was originally known from a single specimen — an old male from the voyage of 1905–06. No other tortoises or remains were found on the island for a long time after its sighting, leading to suggestions that the specimen was an artificial introduction from elsewhere. Fernandina has neither human settlements nor feral

A feral () animal or plant is one that lives in the wild but is descended from domesticated individuals. As with an introduced species, the introduction of feral animals or plants to non-native regions may disrupt ecosystems and has, in some ...

mammals, so if this subspecies ever did exist, its extinction would have been by natural means, such as volcanic activity. Nevertheless, there have occasionally been reports from Fernandina. In 2019, an elderly female specimen was finally discovered on Fernandina and transferred to a breeding center, and trace evidence found on the expedition indicates that more individuals likely exist in the wild. It has been theorized that the rarity of the subspecies may be due to the harsh habitat it survives in, such as the lava

Lava is molten or partially molten rock (magma) that has been expelled from the interior of a terrestrial planet (such as Earth) or a moon onto its surface. Lava may be erupted at a volcano or through a fracture in the crust, on land or un ...

flows that are known to frequently cover the island.

Santa Fe

The extinct Santa Fe subspecies has not yet been described and thus has nobinomial name

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called nomenclature ("two-name naming system") or binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, bot ...

, having been identified from the limited evidence of bone fragments (but no shells, the most durable part) of 14 individuals, old eggs, and old dung found on the island in 1905–06. The island has never been inhabited by man nor had any introduced predators, but reports have been made of whalers hauling tortoises off the island. Later genetic studies of the bone fragments indicate that the Santa Fe subspecies was distinct, and was most closely related to ''C. n. hoodensis''. A population of ''C. n. hoodensis'' has since been reintroduced to and established on the island to fill in the ecological role of the Santa Fe tortoise.

Species of doubtful existence

The purported RĂ¡bida Island

RĂ¡bida Island (), is one of the GalĂ¡pagos Islands. The island has also been known as Jervis Island named in honour of the 18th-century British admiral John Jervis. In Ecuador it is officially known as Isla RĂ¡bida.

Wildlife

In addition to ...

subspecies (''C. n. wallacei'') was described from a single specimen collected by the California Academy of Sciences

The California Academy of Sciences is a research institute and natural history museum in San Francisco, California, that is among the largest museums of natural history in the world, housing over 46 million specimens. The Academy began in 1853 ...

in December 1905, which has since been lost. This individual was probably an artificial introduction from another island that was originally penned on RĂ¡bida next to a good anchorage, as no contemporary whaling or sealing logs mention removing tortoises from this island.

Description

The tortoises have a large bony shell of a dull brown or grey color. The plates of the shell are fused with the ribs in a rigid protective structure that is integral to the skeleton.Lichen

A lichen ( , ) is a composite organism that arises from algae or cyanobacteria living among filaments of multiple fungi species in a mutualistic relationship. Tortoises keep a characteristic

The tortoises are

The tortoises are

Charles Darwin visited the GalĂ¡pagos for five weeks on the second voyage of HMS ''Beagle'' in 1835 and saw GalĂ¡pagos tortoises on San Cristobal (Chatham) and Santiago (James) Islands. They appeared several times in his writings and journals, and played a role in the development of the theory of evolution.

Darwin wrote in his account of the voyage:

Charles Darwin visited the GalĂ¡pagos for five weeks on the second voyage of HMS ''Beagle'' in 1835 and saw GalĂ¡pagos tortoises on San Cristobal (Chatham) and Santiago (James) Islands. They appeared several times in his writings and journals, and played a role in the development of the theory of evolution.

Darwin wrote in his account of the voyage:

However, Darwin did have four live juvenile specimens to compare from different islands. These were pet tortoises taken by himself (from San Salvador), his captain

However, Darwin did have four live juvenile specimens to compare from different islands. These were pet tortoises taken by himself (from San Salvador), his captain

The remaining subspecies of tortoise range in IUCN classification from

The remaining subspecies of tortoise range in IUCN classification from  ;Legal protection

The GalĂ¡pagos giant tortoise is now strictly protected and is listed on Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered subspecies of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). The listing requires that trade in the

;Legal protection

The GalĂ¡pagos giant tortoise is now strictly protected and is listed on Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered subspecies of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). The listing requires that trade in the

images and movies of the GalĂ¡pagos giant tortoise (''Geochelone'' spp.)

* ttp://galapagosconservation.org.uk/projects/galapagos-tortoise-movement-ecology-programme/ Galapagos Tortoise Movement Ecology Programme

'Extinct' Galapagos tortoise may still exist

{{DEFAULTSORT:Galapagos tortoise Tortoise, Galapagos Taxa named by Jean René Constant Quoy Taxa named by Joseph Paul Gaimard Reptiles described in 1824 Reptiles of Ecuador Turtles of South America

scute

A scute or scutum (Latin: ''scutum''; plural: ''scuta'' "shield") is a bony external plate or scale overlaid with horn, as on the shell of a turtle, the skin of crocodilians, and the feet of birds. The term is also used to describe the anterior po ...

(shell segment) pattern on their shells throughout life, though the annual growth bands are not useful for determining age because the outer layers are worn off with time. A tortoise can withdraw its head, neck, and fore limbs into its shell for protection. The legs are large and stumpy, with dry, scaly skin and hard scales

Scale or scales may refer to:

Mathematics

* Scale (descriptive set theory), an object defined on a set of points

* Scale (ratio), the ratio of a linear dimension of a model to the corresponding dimension of the original

* Scale factor, a number w ...

. The front legs have five claws, the back legs four.

Gigantism

The discoverer of the GalĂ¡pagos Islands, Fray TomĂ¡s de Berlanga, Bishop of Panama, wrote in 1535 of "such big tortoises that each could carry a man on top of himself." Naturalist Charles Darwin remarked after his trip three centuries later in 1835, "These animals grow to an immense size ... several so large that it required six or eight men to lift them from the ground". The largest recorded individuals have reached weights of over and lengths of . Size overlap is extensive with theAldabra giant tortoise

The Aldabra giant tortoise (''Aldabrachelys gigantea'') is a species of tortoise in the family Testudinidae. The species is endemic to the islands of the Aldabra Atoll in the Seychelles. It is one of the largest tortoises in the world.Pritchar ...

, however taken as a subspecies, the GalĂ¡pagos tortoise seems to average slightly larger, with weights in excess of being slightly more commonplace. Weights in the larger bodied subspecies range from in mature males and from in adult females. However, the size is variable across the islands and subspecies; those from PinzĂ³n Island

PinzĂ³n Island (Spanish: ''Isla PinzĂ³n''), sometimes called Duncan Island (after Adam Duncan, 1st Viscount Duncan), is an island in the GalĂ¡pagos Islands, Ecuador.

PinzĂ³n is home to giant GalĂ¡pagos tortoises of the endemic subspecies '' Chel ...

are relatively small with a maximum known weight of and carapace length of approximately compared to range in tortoises from Santa Cruz Island

Santa Cruz Island (Spanish: ''Isla Santa Cruz'', Chumash: ''Limuw'') is located off the southwestern coast of Ventura, California, United States. It is the largest island in California and largest of the eight islands in the Channel Islands a ...

. The tortoises' gigantism was probably a trait useful on continents that was fortuitously helpful for successful colonisation of these remote oceanic islands rather than an example of evolved insular gigantism

Island gigantism, or insular gigantism, is a biological phenomenon in which the size of an animal species isolated on an island increases dramatically in comparison to its mainland relatives. Island gigantism is one aspect of the more general Fos ...

. Large tortoises would have a greater chance of surviving the journey over water from the mainland as they can hold their heads a greater height above the water level and have a smaller surface area/volume ratio, which reduces osmotic

Osmosis (, ) is the spontaneous net movement or diffusion of solvent molecules through a selectively-permeable membrane from a region of high water potential (region of lower solute concentration) to a region of low water potential (region of ...

water loss. Their significant water and fat reserves would allow the tortoises to survive long ocean crossings without food or fresh water, and to endure the drought-prone climate of the islands. A larger size allowed them to better tolerate extremes of temperature due to gigantothermy Gigantothermy (sometimes called ectothermic homeothermy or inertial homeothermy) is a phenomenon with significance in biology and paleontology, whereby large, bulky ectothermic animals are more easily able to maintain a constant, relatively high bod ...

. Fossil giant tortoises from mainland South America have been described that support this hypothesis of gigantism that pre-existed the colonization of islands.

Shell shape

GalĂ¡pagos tortoises possess two main shell forms that correlate with the biogeographic history of the subspecies group. They exhibit a spectrum of carapace morphology ranging from "saddleback" (denoting upward arching of the front edge of the shell resembling a saddle) to "domed" (denoting a rounded convex surface resembling a dome). When a saddleback tortoise withdraws its head and forelimbs into its shell, a large unprotected gap remains over the neck, evidence of the lack of predation during the evolution of this structure. Larger islands with humid highlands over in elevation, such as Santa Cruz, have abundant vegetation near the ground. Tortoises native to these environments tend to have domed shells and are larger, with shorter necks and limbs. Saddleback tortoises originate from small islands less than in elevation with dry habitats (e.g. Española and PinzĂ³n) that are more limited in food and other resources. Two lineages of GalĂ¡pagos tortoises possess the Island of Santa Cruz and when observed it is concluded that despite the shared similarities of growth patterns and morphological changes observed during growth, the two lineages and two sexes can be distinguished on the basis of distinct carapace features. Lineages differ by the shape of the vertebral and pleural scutes. Females have a more elongated and wider carapace shape than males. Carapace shape changes with growth, with vertebral scutes becoming narrower and pleural scutes becoming larger during lateontogeny

Ontogeny (also ontogenesis) is the origination and development of an organism (both physical and psychological, e.g., moral development), usually from the time of fertilization of the egg to adult. The term can also be used to refer to the stu ...

.

;Evolutionary implications

In combination with proportionally longer necks and limbs, the unusual saddleback carapace structure is thought to be an adaptation to increase vertical reach, which enables the tortoise to browse tall vegetation such as the ''Opuntia

''Opuntia'', commonly called prickly pear or pear cactus, is a genus of flowering plants in the cactus family Cactaceae. Prickly pears are also known as ''tuna'' (fruit), ''sabra'', ''nopal'' (paddle, plural ''nopales'') from the Nahuatl word f ...

'' (prickly pear) cactus that grows in arid environments. Saddlebacks are more territorial and smaller than domed varieties, possibly adaptations to limited resources. Alternatively, larger tortoises may be better-suited to high elevations because they can resist the cooler temperatures that occur with cloud cover or fog.

A competing hypothesis is that, rather than being principally a feeding adaptation, the distinctive saddle shape and longer extremities might have been a secondary sexual characteristic

Secondary sex characteristics are features that appear during puberty in humans, and at sexual maturity in other animals. These characteristics are particularly evident in the sexual dimorphism, sexually dimorphic phenotypic traits that distinguis ...

of saddleback males. Male competition over mates is settled by dominance displays on the basis of vertical neck height rather than body size ( see below). This correlates with the observation that saddleback males are more aggressive than domed males. The shell distortion and elongation of the limbs and neck in saddlebacks is probably an evolutionary compromise between the need for a small body size in dry conditions and a high vertical reach for dominance displays.

The saddleback carapace probably evolved independently several times in dry habitats, since genetic similarity between populations does not correspond to carapace shape. Saddleback tortoises are, therefore, not necessarily more closely related to each other than to their domed counterparts, as shape is not determined by a similar genetic background, but by a similar ecological one.

; Sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where the sexes of the same animal and/or plant species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most ani ...

is most pronounced in saddleback populations in which males have more angled and higher front openings, giving a more extreme saddled appearance. Males of all varieties generally have longer tails and shorter, concave plastrons with thickened knobs at the back edge to facilitate mating. Males are larger than females — adult males weigh around while females are .

Behavior

Routine

The tortoises areectotherm

An ectotherm (from the Greek () "outside" and () "heat") is an organism in which internal physiological sources of heat are of relatively small or of quite negligible importance in controlling body temperature.Davenport, John. Animal Life a ...

ic (cold-blooded), so they bask for 1–2 hours after dawn to absorb the sun's heat through their dark shells before actively foraging for 8–9 hours a day.Swingland, I.R. (1989). Geochelone elephantopus. ''Galapagos giant tortoises''. In: Swingland I.R. and Klemens M.W. (eds.) ''The Conservation Biology of Tortoises.'' Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC), No. 5, pp. 24–28. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. . They travel mostly in the early morning or late afternoon between resting and grazing areas. They have been observed to walk at a speed of .

On the larger and more humid islands, the tortoises seasonally migrate between low elevations, which become grassy plains in the wet season, and meadowed areas of higher elevation (up to ) in the dry season. The same routes have been used for many generations, creating well-defined paths through the undergrowth known as "tortoise highways". On these wetter islands, the domed tortoises are gregarious and often found in large herds, in contrast to the more solitary and territorial disposition of the saddleback tortoises.

Tortoises sometimes rest in mud wallows or rain-formed pools, which may be both a thermoregulatory

Thermoregulation is the ability of an organism to keep its body temperature within certain boundaries, even when the surrounding temperature is very different. A thermoconforming organism, by contrast, simply adopts the surrounding temperature ...

response during cool nights, and a protection from parasites

Parasitism is a Symbiosis, close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the Host (biology), host, causing it some harm, and is Adaptation, adapted structurally to this way of lif ...

such as mosquitoes and ticks. Parasites are countered by taking dust baths in loose soil. Some tortoises have been noted to shelter at night under overhanging rocks. Others have been observed sleeping in a snug depression in the earth or brush called a "pallet". Local tortoises using the same pallet sites, such as on VolcĂ¡n Alcedo, results in the formation of small, sandy pits.

Diet