G. Mennen Williams on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

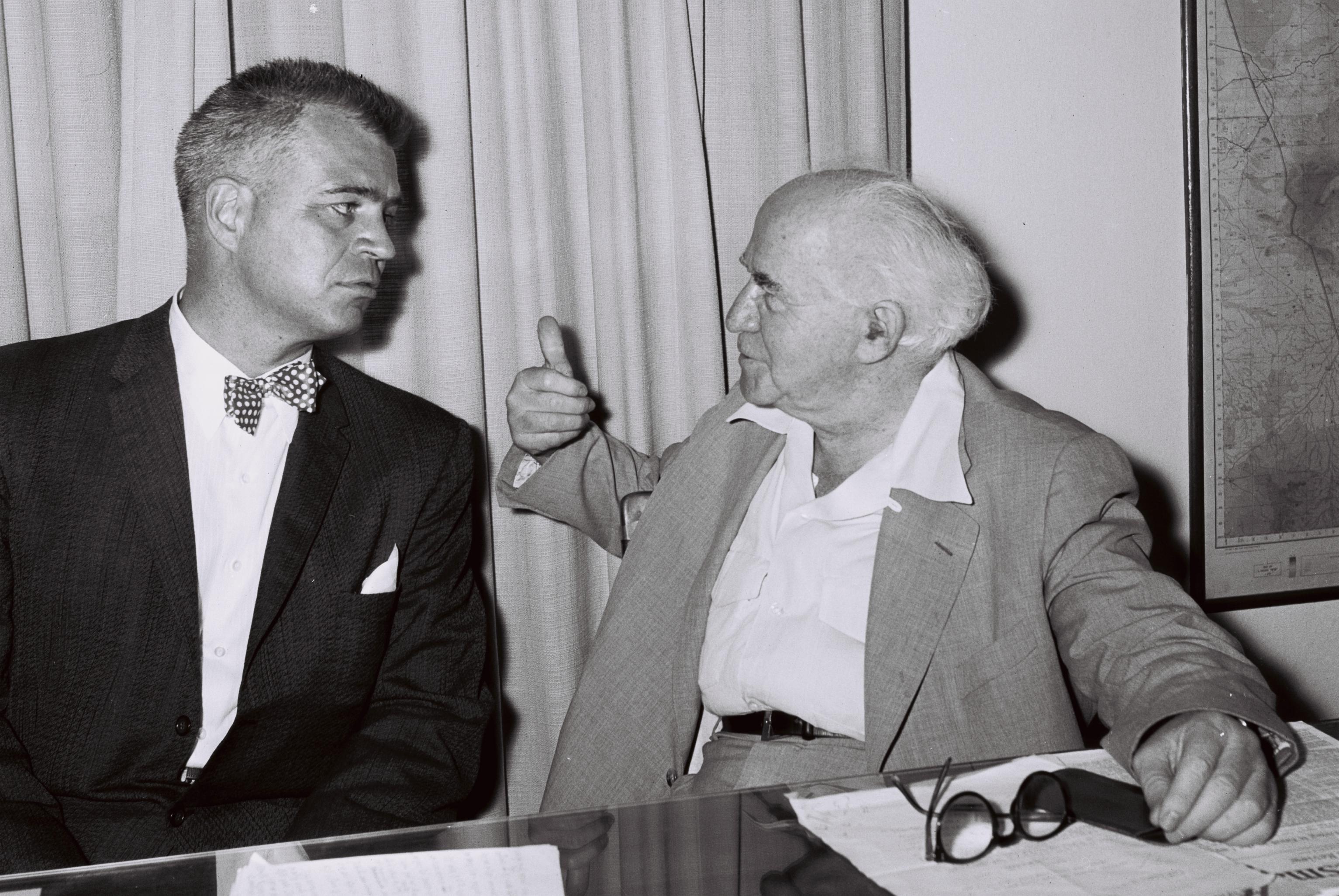

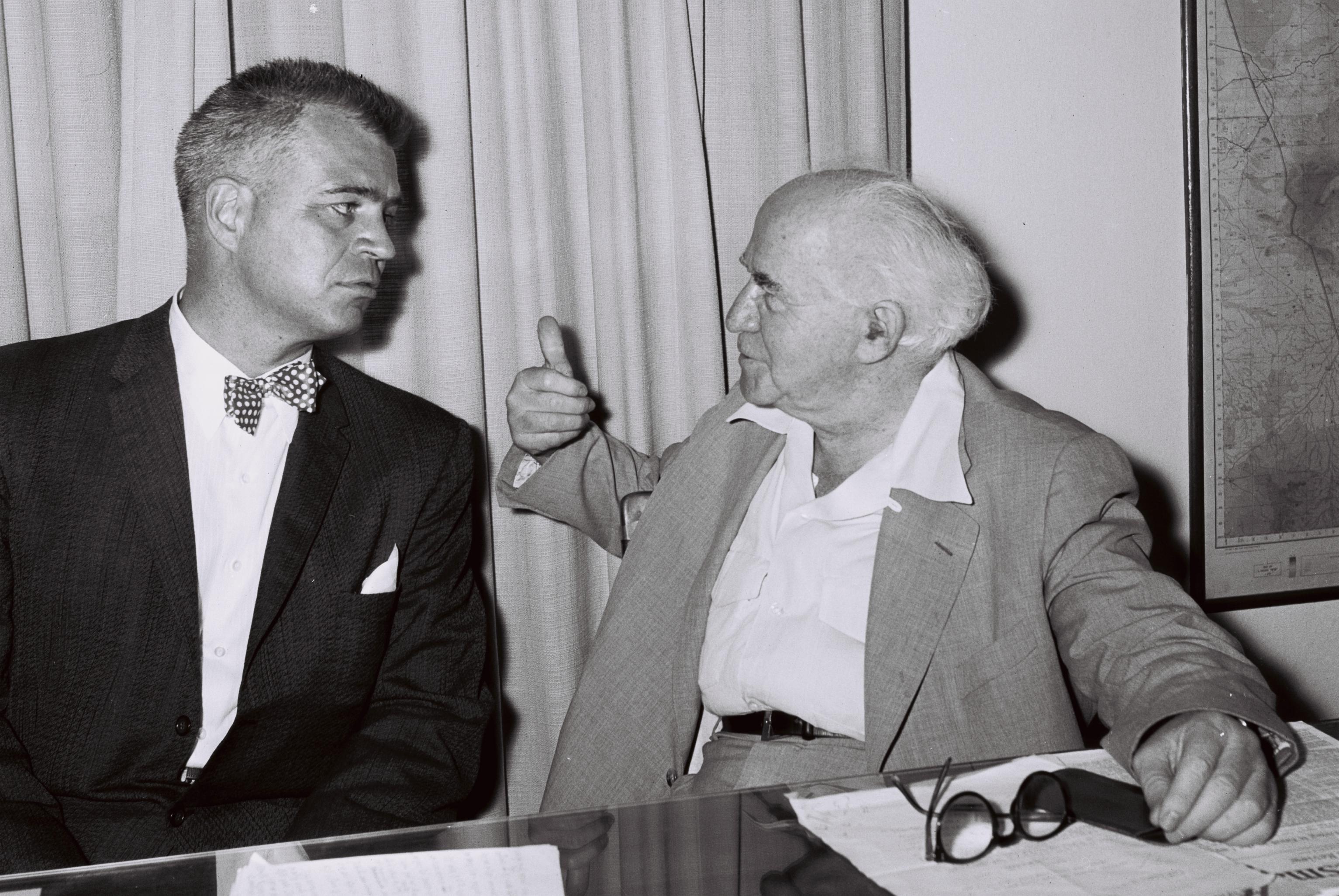

Gerhard Mennen "Soapy" Williams (February 23, 1911 – February 2, 1988) was an American politician who served as the 41st

On November 2, 1948, Williams was elected Governor of Michigan, defeating Governor Kim Sigler with the support of labor unions and dissident Republicans. He was elected to a record six two-year terms in that post. Among his accomplishments was the construction of the Mackinac Bridge. He appeared on the cover of '' Time'' September 15, 1952, issue, sporting his signature green bow tie with white polka dots.

Williams believed the Michigan Department of Corrections was underfunded and outdated, and that the state's prisons were dangerously overcrowded. While visiting Marquette Branch Prison in July 1950, Williams was attacked and briefly held hostage by a group of three inmates hoping to escape. The governor had a knife held to his throat, but his attackers were soon overpowered by his bodyguard and prison employees. One of his attackers was shot dead. Williams was unharmed and mostly unshaken, choosing to continue on with his tour of the Upper Peninsula. He used the attack to his political advantage, blaming it on budget cuts made by the Republican-controlled

On November 2, 1948, Williams was elected Governor of Michigan, defeating Governor Kim Sigler with the support of labor unions and dissident Republicans. He was elected to a record six two-year terms in that post. Among his accomplishments was the construction of the Mackinac Bridge. He appeared on the cover of '' Time'' September 15, 1952, issue, sporting his signature green bow tie with white polka dots.

Williams believed the Michigan Department of Corrections was underfunded and outdated, and that the state's prisons were dangerously overcrowded. While visiting Marquette Branch Prison in July 1950, Williams was attacked and briefly held hostage by a group of three inmates hoping to escape. The governor had a knife held to his throat, but his attackers were soon overpowered by his bodyguard and prison employees. One of his attackers was shot dead. Williams was unharmed and mostly unshaken, choosing to continue on with his tour of the Upper Peninsula. He used the attack to his political advantage, blaming it on budget cuts made by the Republican-controlled

After leaving office in 1961, Williams assumed the post of

After leaving office in 1961, Williams assumed the post of

Williams was elected to the Michigan Supreme Court in 1970 and was named Chief Justice in 1983. Thus, like William Howard Taft in the federal government, he occupied the highest executive and judicial offices in Michigan government.

Williams was elected to the Michigan Supreme Court in 1970 and was named Chief Justice in 1983. Thus, like William Howard Taft in the federal government, he occupied the highest executive and judicial offices in Michigan government.

Michigan Supreme Court Historical Society

Michigan Lawyers in History

Find a Grave Memorial

National Governors Association

, - {{DEFAULTSORT:Williams, G. Mennen 1911 births 1988 deaths 20th-century American diplomats 20th-century American politicians Ambassadors of the United States to the Philippines American Episcopalians Assistant Secretaries of State for African Affairs Burials in Michigan Chief Justices of the Michigan Supreme Court Democratic Party governors of Michigan Kennedy administration personnel Lyndon B. Johnson administration personnel Justices of the Michigan Supreme Court Military personnel from Detroit Politicians from Detroit Princeton University alumni United States Navy officers United States Navy personnel of World War II University of Michigan Law School alumni

governor of Michigan

The governor of Michigan is the head of state, head of government, and chief executive of the U.S. state of Michigan. The current governor is Gretchen Whitmer, a member of the Democratic Party, who was inaugurated on January 1, 2019, as the stat ...

, elected in 1948 and serving six two-year terms in office. He later served as Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs

The Assistant Secretary for the Bureau of African Affairs is the head of the Bureau of African Affairs, within the United States Department of State, who guides operation of the U.S. diplomatic establishment in the countries of sub-Saharan Afric ...

under Presidents John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination i ...

and Lyndon B. Johnson and as chief justice of the Michigan Supreme Court.

Williams advocated for civil rights, racial equality, and justice for the poor. As assistant secretary of state, his remark that "what we want for the Africans is what they want for themselves", reported in the press as "Africa for the Africans", sparked controversy at the time.

A staunch liberal, Williams was described by the '' Chicago Tribune'' as a political reformer who "helped forge the alliance between Democrats, blacks and union voters in the late 1940s that began a strong liberal tradition in Michigan."

Personal life and early career

Williams was born in Detroit, Michigan, to Henry P. Williams and Elma Mennen. His mother came from a prominent family; her father, Gerhard Heinrich Mennen, was the founder of the Mennen brand of men's personal care products. Because of this, Williams acquired the popular nickname "Soapy". Williams attended the Salisbury School in Connecticut, an exclusiveEpiscopal

Episcopal may refer to:

*Of or relating to a bishop, an overseer in the Christian church

*Episcopate, the see of a bishop – a diocese

*Episcopal Church (disambiguation), any church with "Episcopal" in its name

** Episcopal Church (United State ...

preparatory school. He graduated from Princeton University with an A.B. in history in 1933 after completing a senior thesis titled "Social Significance of Henry Ford". At Princeton, Williams was a member of the Quadrangle Club

The Princeton Quadrangle Club, often abbreviated to "Quad", is one of the eleven eating clubs at Princeton University that remain open. Located at 33 Prospect Avenue, the club is currently "sign-in," meaning it permits any second semester sophom ...

. He then received a Juris Doctor

The Juris Doctor (J.D. or JD), also known as Doctor of Jurisprudence (J.D., JD, D.Jur., or DJur), is a graduate-entry professional degree in law

and one of several Doctor of Law degrees. The J.D. is the standard degree obtained to practice law ...

degree from the University of Michigan Law School. While at law school, Williams became affiliated with the Democratic Party, departing from his family's strong ties to the Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

*Republican Party (Liberia)

* Republican Part ...

.

Williams met Nancy Quirk on a blind date while attending the university. She was the daughter of D. L. Quirk and Julia (Trowbridge) Quirk, a prominent Ypsilanti family involved in banking and paper milling. Her brother, Daniel Quirk, was later mayor of Ypsilanti. The couple married in 1937 and had three children; a son, G. Mennen Williams Jr., and two daughters, Nancy Ketterer III and Wendy Stock Williams.

He worked with the law firm Griffiths, Williams and Griffiths from 1936 to 1941. Law firm partners included Hicks Griffiths and Martha Griffiths, later elected a Member of Congress and Michigan Lt. Governor.

During World War II, he served four years in the United States Navy as an air combat intelligence officer in the South Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

. He achieved the rank of lieutenant commander and earned ten battle stars. He later served as the deputy director of the Office of Price Administration from 1946 to 1947, and was named to the Michigan Liquor Control Commission

The Michigan Liquor Control Commission is an agency of the U.S. state of Michigan, within the Michigan Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs (LARA), responsible for regulating the sale and distribution of liquor in the state.

History

T ...

in 1947.

Governor of Michigan

On November 2, 1948, Williams was elected Governor of Michigan, defeating Governor Kim Sigler with the support of labor unions and dissident Republicans. He was elected to a record six two-year terms in that post. Among his accomplishments was the construction of the Mackinac Bridge. He appeared on the cover of '' Time'' September 15, 1952, issue, sporting his signature green bow tie with white polka dots.

Williams believed the Michigan Department of Corrections was underfunded and outdated, and that the state's prisons were dangerously overcrowded. While visiting Marquette Branch Prison in July 1950, Williams was attacked and briefly held hostage by a group of three inmates hoping to escape. The governor had a knife held to his throat, but his attackers were soon overpowered by his bodyguard and prison employees. One of his attackers was shot dead. Williams was unharmed and mostly unshaken, choosing to continue on with his tour of the Upper Peninsula. He used the attack to his political advantage, blaming it on budget cuts made by the Republican-controlled

On November 2, 1948, Williams was elected Governor of Michigan, defeating Governor Kim Sigler with the support of labor unions and dissident Republicans. He was elected to a record six two-year terms in that post. Among his accomplishments was the construction of the Mackinac Bridge. He appeared on the cover of '' Time'' September 15, 1952, issue, sporting his signature green bow tie with white polka dots.

Williams believed the Michigan Department of Corrections was underfunded and outdated, and that the state's prisons were dangerously overcrowded. While visiting Marquette Branch Prison in July 1950, Williams was attacked and briefly held hostage by a group of three inmates hoping to escape. The governor had a knife held to his throat, but his attackers were soon overpowered by his bodyguard and prison employees. One of his attackers was shot dead. Williams was unharmed and mostly unshaken, choosing to continue on with his tour of the Upper Peninsula. He used the attack to his political advantage, blaming it on budget cuts made by the Republican-controlled Michigan Legislature

The Michigan Legislature is the legislature of the U.S. state of Michigan. It is organized as a bicameral body composed of an upper chamber, the Senate, and a lower chamber, the House of Representatives. Article IV of the Michigan Constitution, ...

. Later in the same year, Williams gained prominence for his refusal to extradite Haywood Patterson

Haywood Patterson (December 12, 1912 – August 24, 1952) was one of the Scottsboro Boys (See Powell v. Alabama). He was accused of raping Victoria Price and Ruby Bates. He wrote a book about his experience, ''Scottsboro Boy''.

Patterson was i ...

, one of the Scottsboro Boys, who had escaped from prison in Alabama in 1948 and hidden in Detroit for two years.

Also during Williams's twelve years in office, a farm-marketing program was sanctioned, teachers' salaries, school facilities and educational programs were improved and there were also commissions formed to research problems related to aging, sex offenders and adolescent behavior.

Williams named the first woman judge in the state's history as well as the first black judge. As a delegate to the Democratic National Convention

The Democratic National Convention (DNC) is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1832 by the United States Democratic Party. They have been administered by the Democratic National Committee since the 1852 ...

in 1956, he unsuccessfully sought the vice-presidential nomination. At the 1952, 1956 and 1960 conventions he fought for insertion of a strong civil rights plank in the party platform. He strongly opposed the selection of Lyndon Baines Johnson as vice president in 1960, feeling that Johnson was "ideologically wrong on civil rights". Williams made public his opposition, shouting "No" when a call was made for Johnson's nomination to be made unanimous. He was the only delegate to publicly oppose Johnson's nomination.

His final term in office was marked by high-profile struggles with the Republican-controlled state legislature

A state legislature is a legislative branch or body of a political subdivision in a federal system.

Two federations literally use the term "state legislature":

* The legislative branches of each of the fifty state governments of the United Sta ...

and a near-shutdown of the state government. He therefore chose not to seek reelection in 1960. Williams left office on January 1, 1961.

Post-gubernatorial years

After leaving office in 1961, Williams assumed the post of

After leaving office in 1961, Williams assumed the post of Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs

The Assistant Secretary for the Bureau of African Affairs is the head of the Bureau of African Affairs, within the United States Department of State, who guides operation of the U.S. diplomatic establishment in the countries of sub-Saharan Afric ...

in the administration of President John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination i ...

. His remark at a press conference that "what we want for the Africans is what they want for themselves", reported in the press as "Africa for the Africans", sparked controversy. Whites in South Africa and Rhodesia

Rhodesia (, ), officially from 1970 the Republic of Rhodesia, was an unrecognised state in Southern Africa from 1965 to 1979, equivalent in territory to modern Zimbabwe. Rhodesia was the ''de facto'' successor state to the British colony of S ...

, and in the British and Portuguese colonies contended that Williams wanted them expelled from the continent. Williams defended his remarks, saying that he included white Africans as Africans. Williams was defended by Kennedy at a press conference, saying that "Africa for the Africans does not seem to me to be an unreasonable statement." Kennedy said that Williams made it clear he was referring to Africans of all colors, and "I don't know who else Africa should be for."

He served in this post until early 1966, when he resigned to unsuccessfully challenge Republican United States Senator Robert P. Griffin

Robert Paul Griffin (November 6, 1923 – April 16, 2015) was an American politician. A member of the Republican Party, he represented Michigan in the United States House of Representatives and United States Senate and was a Justice of the M ...

. Two years later, he was named by President Lyndon B. Johnson to be U.S. ambassador to the Philippines

The ambassador of the United States of America to the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Sugo ng Estados Unidos sa Pilipinas) was established on July 4, 1946, after the Philippines gained its independence from the United States.

The ambassador t ...

, where he served less than a year.

In 1969 he wrote a book on the emergence of modern Africa, ''Africa for the Africans''.

Michigan Supreme Court

Williams was elected to the Michigan Supreme Court in 1970 and was named Chief Justice in 1983. Thus, like William Howard Taft in the federal government, he occupied the highest executive and judicial offices in Michigan government.

Williams was elected to the Michigan Supreme Court in 1970 and was named Chief Justice in 1983. Thus, like William Howard Taft in the federal government, he occupied the highest executive and judicial offices in Michigan government.

Retirement and death

Williams left the Court on January 1, 1987, and died the following year in Detroit at the age of 76, just three weeks before his 77th birthday. He was temporarily entombed at Evergreen Cemetery in Detroit and there was a formal military funeral for him. After winter his remains were interred at the Protestant Cemetery onMackinac Island

Mackinac Island ( ; french: Île Mackinac; oj, Mishimikinaak ᒥᔑᒥᑭᓈᒃ; otw, Michilimackinac) is an island and resort area, covering in land area, in the U.S. state of Michigan. The name of the island in Odawa is Michilimackinac an ...

. His ''New York Times'' obituary said of Williams's diplomatic service: "Traveling widely, he studied the needs of countries in the birth pangs of independence and brought their pleas for American investment and trust to Washington."

Honors

The state government's law building, G. Mennen Williams Building in Lansing, constructed in 1967, was dedicated in Williams's honor in 1997. A G. Mennen Williams dinner is an annual event held by the Ionia County Democratic Party each July at the World's Largest Free Fair in Ionia, Michigan. Originally called the Democratic Tent Dinner at its start in the mid-40s, it was renamed after Soapy in 1988 as a way to pay homage to the man that paved the way for dinners to be held at the fair. The Ionia Republican Party had held dinners at the fairgrounds during the 1940s, but the Democrats could not until Soapy stepped up and gained the party equal access in 1949. A portion of Interstate 75 inCheboygan County

Cheboygan County ( ) is a County (United States), county in the U.S. state of Michigan. As of the 2020 United States Census, 2020 Census, the population was 25,579. The county seat is Cheboygan, Michigan, Cheboygan. The county boundaries were s ...

is known as the G. Mennen Williams Highway.

At Detroit Mercy Law (formerly: University of Detroit Mercy School of Law), the Moot Court Board of Advocates hosts the annual G. Mennen Williams Moot Court Competition for all first-year students through their Applied Legal Theory and Analysis course. First year students draft a dispositive motion and brief in support as part of their writing course, and argue their position before a mock tribunal.

Notes

References

Further reading

*External links

Michigan Supreme Court Historical Society

Michigan Lawyers in History

Find a Grave Memorial

National Governors Association

, - {{DEFAULTSORT:Williams, G. Mennen 1911 births 1988 deaths 20th-century American diplomats 20th-century American politicians Ambassadors of the United States to the Philippines American Episcopalians Assistant Secretaries of State for African Affairs Burials in Michigan Chief Justices of the Michigan Supreme Court Democratic Party governors of Michigan Kennedy administration personnel Lyndon B. Johnson administration personnel Justices of the Michigan Supreme Court Military personnel from Detroit Politicians from Detroit Princeton University alumni United States Navy officers United States Navy personnel of World War II University of Michigan Law School alumni