Freedom Rides on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Freedom Riders

- slideshow by ''

FBI files on the Freedom Riders

Online collection of Ride-related articles written by Freedom Riders~ Civil Rights Movement Archive.

Curated links to Freedom Riders archival material

Civil Rights Digital Library.

Civil Rights Activist Bob Zellner interviewed

on ''Conversations from Penn State''

Freedom Riders

historical marker in

CORE's Route 40 Project

campaign for desegregation of Maryland highway, 1961

''Freedom Riders'' interviews by ''American Experience''

at the

Freedom Riders were

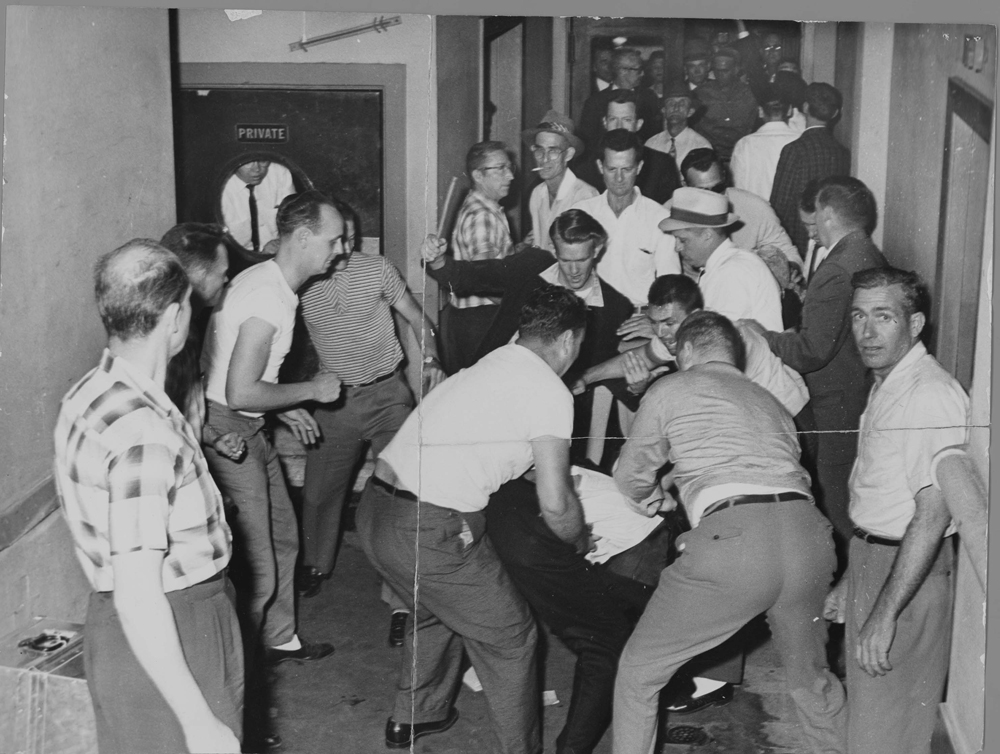

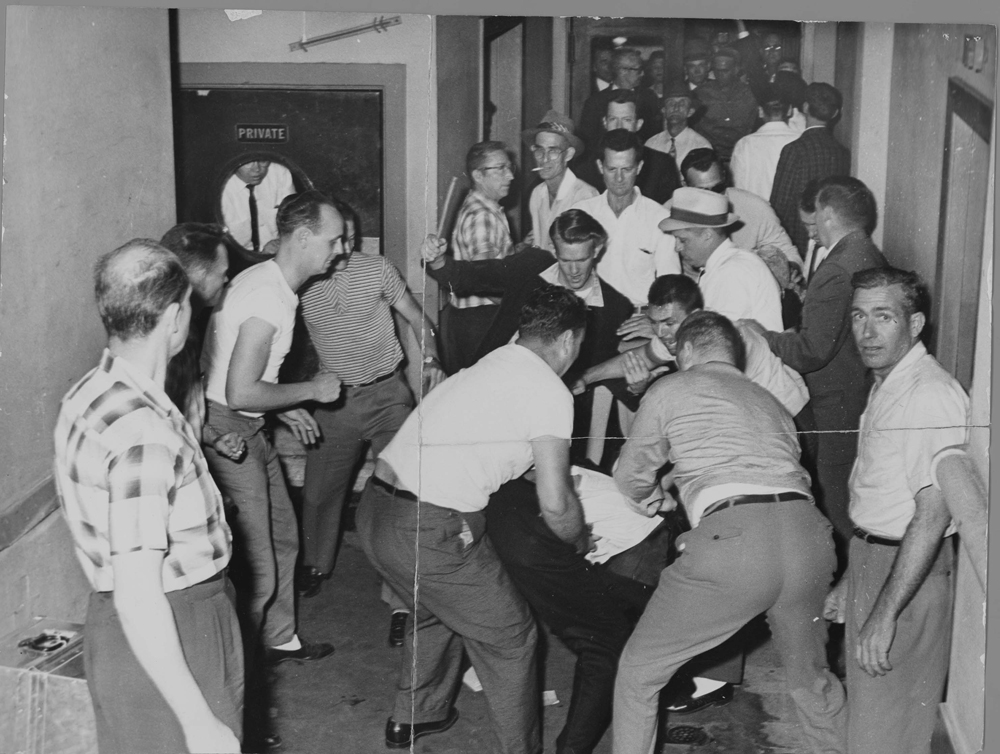

When the bus arrived in Birmingham, it was attacked by a mob of KKK members aided and abetted by police under the orders of Commissioner Connor.Freedom Rides

When the bus arrived in Birmingham, it was attacked by a mob of KKK members aided and abetted by police under the orders of Commissioner Connor.Freedom Rides

~ Civil Rights Movement Archive. As the riders exited the bus, they were beaten by the mob with baseball bats, iron

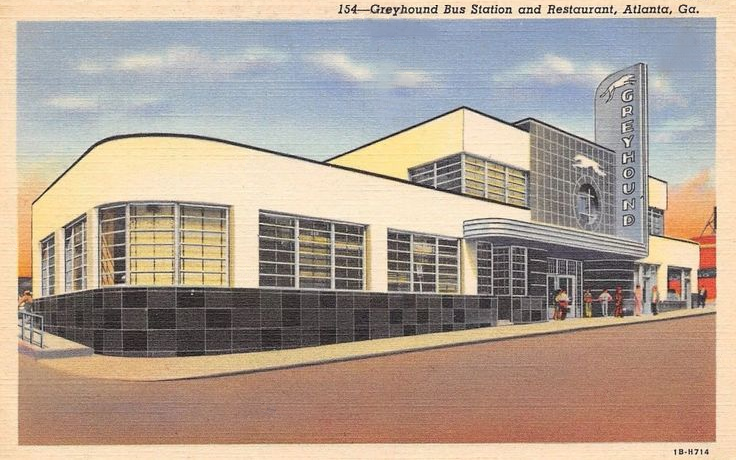

The Highway Patrol abandoned the bus and riders at the Montgomery city limits. At the Montgomery Greyhound station on South Court Street, a white mob awaited. They beat the Freedom Riders with baseball bats and iron pipes. The local police allowed the beatings to go on uninterrupted. Again, white Freedom Riders were singled out for particularly brutal beatings. Reporters and news photographers were attacked first and their cameras destroyed, but one reporter took a photo later of Jim Zwerg in the hospital, showing how he was beaten and bruised. Seigenthaler, a Justice Department official, was beaten and left unconscious lying in the street. Ambulances refused to take the wounded to the hospital. Local black residents rescued them, and a number of the Freedom Riders were hospitalized.

On the following night, Sunday, May 21, more than 1500 people packed into Reverend Ralph Abernathy's First Baptist Church to honor the Freedom Riders. Among the speakers were Rev.

The Highway Patrol abandoned the bus and riders at the Montgomery city limits. At the Montgomery Greyhound station on South Court Street, a white mob awaited. They beat the Freedom Riders with baseball bats and iron pipes. The local police allowed the beatings to go on uninterrupted. Again, white Freedom Riders were singled out for particularly brutal beatings. Reporters and news photographers were attacked first and their cameras destroyed, but one reporter took a photo later of Jim Zwerg in the hospital, showing how he was beaten and bruised. Seigenthaler, a Justice Department official, was beaten and left unconscious lying in the street. Ambulances refused to take the wounded to the hospital. Local black residents rescued them, and a number of the Freedom Riders were hospitalized.

On the following night, Sunday, May 21, more than 1500 people packed into Reverend Ralph Abernathy's First Baptist Church to honor the Freedom Riders. Among the speakers were Rev.  In a commemorative Op-Ed piece in 2011,

In a commemorative Op-Ed piece in 2011,

The next day, Monday, May 22, more Freedom Riders arrived in Montgomery to continue the rides through the South and replace the wounded riders still in the hospital. Behind the scenes, the Kennedy administration arranged a deal with the governors of Alabama and Mississippi, where the governors agreed that state police and the National Guard would protect the Riders from mob violence. In return, the federal government would not intervene to stop local police from arresting Freedom Riders for violating segregation ordinances when the buses arrived at the depots.

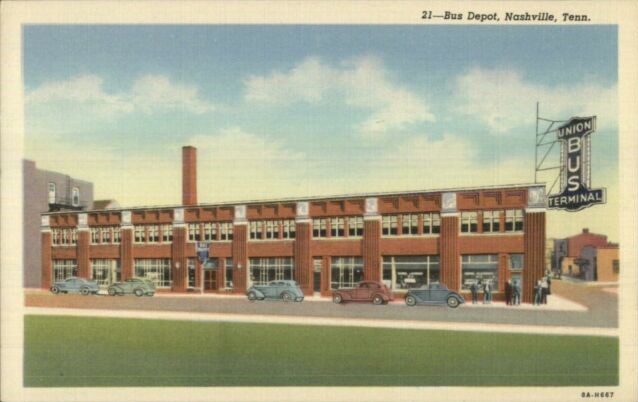

On Wednesday morning, May 24, Freedom Riders boarded buses for the journey to

The next day, Monday, May 22, more Freedom Riders arrived in Montgomery to continue the rides through the South and replace the wounded riders still in the hospital. Behind the scenes, the Kennedy administration arranged a deal with the governors of Alabama and Mississippi, where the governors agreed that state police and the National Guard would protect the Riders from mob violence. In return, the federal government would not intervene to stop local police from arresting Freedom Riders for violating segregation ordinances when the buses arrived at the depots.

On Wednesday morning, May 24, Freedom Riders boarded buses for the journey to

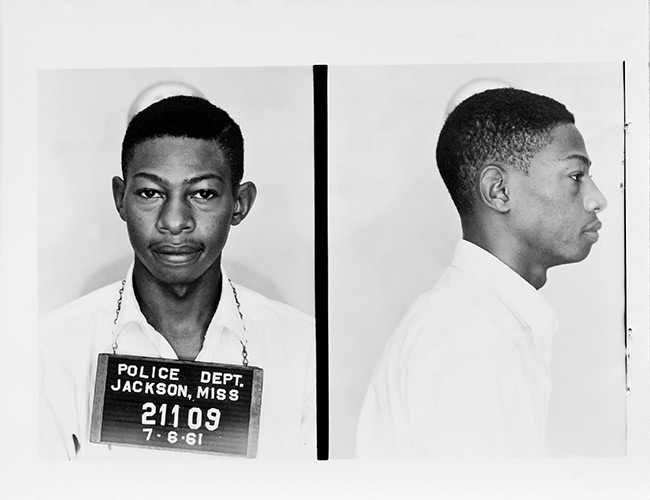

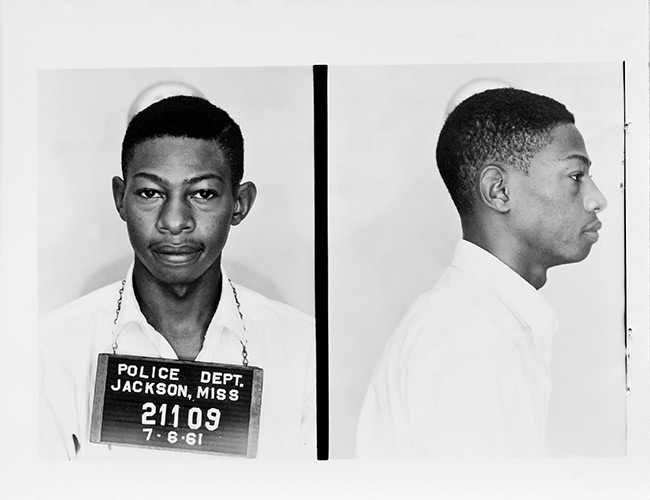

CORE, SNCC, and the SCLC rejected any "cooling off period". They formed a Freedom Riders Coordinating Committee to keep the Rides rolling through June, July, August, and September. During those months, more than 60 different Freedom Rides criss-crossed the South, most of them converging on Jackson, where every Rider was arrested, more than 300 in total. An unknown number were arrested in other Southern towns. It is estimated that almost 450 people participated in one or more Freedom Rides. About 75% were male, and the same percentage were under the age of 30, with about equal participation from black and white citizens.

During the summer of 1961, Freedom Riders also campaigned against other forms of

CORE, SNCC, and the SCLC rejected any "cooling off period". They formed a Freedom Riders Coordinating Committee to keep the Rides rolling through June, July, August, and September. During those months, more than 60 different Freedom Rides criss-crossed the South, most of them converging on Jackson, where every Rider was arrested, more than 300 in total. An unknown number were arrested in other Southern towns. It is estimated that almost 450 people participated in one or more Freedom Rides. About 75% were male, and the same percentage were under the age of 30, with about equal participation from black and white citizens.

During the summer of 1961, Freedom Riders also campaigned against other forms of

In celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Freedom Rides, Oprah Winfrey invited all living Freedom Riders to join her TV program to celebrate their legacy. The episode aired on May 4, 2011.

On May 6–16, 2011, 40 college students from across the United States embarked on a bus ride from Washington, D.C. to New Orleans, retracing the original route of the Freedom Riders. The 2011 Student Freedom Ride, which was sponsored by PBS and ''American Experience'', commemorated the 50th anniversary of the original Freedom Rides. Students met with civil rights leaders along the way and traveled with original Freedom Riders such as Ernest "Rip" Patton, Joan Mulholland, Bob Singleton, Helen Singleton, Jim Zwerg, and Charles Person. On May 16, 2011, PBS aired a documentary called '' Freedom Riders''.

On May 19–21, 2011, the Freedom Rides were commemorated in Montgomery, Alabama, at the new Freedom Ride Museum in the old Greyhound Bus terminal, where some of the violence had taken place in 1961. On May 22–26, 2011, the arrival of the Freedom Rides in Jackson, Mississippi was commemorated with a 50th Anniversary Reunion and Conference in the city. During commemorative events in February 2013 in Montgomery, Congressman

In celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Freedom Rides, Oprah Winfrey invited all living Freedom Riders to join her TV program to celebrate their legacy. The episode aired on May 4, 2011.

On May 6–16, 2011, 40 college students from across the United States embarked on a bus ride from Washington, D.C. to New Orleans, retracing the original route of the Freedom Riders. The 2011 Student Freedom Ride, which was sponsored by PBS and ''American Experience'', commemorated the 50th anniversary of the original Freedom Rides. Students met with civil rights leaders along the way and traveled with original Freedom Riders such as Ernest "Rip" Patton, Joan Mulholland, Bob Singleton, Helen Singleton, Jim Zwerg, and Charles Person. On May 16, 2011, PBS aired a documentary called '' Freedom Riders''.

On May 19–21, 2011, the Freedom Rides were commemorated in Montgomery, Alabama, at the new Freedom Ride Museum in the old Greyhound Bus terminal, where some of the violence had taken place in 1961. On May 22–26, 2011, the arrival of the Freedom Rides in Jackson, Mississippi was commemorated with a 50th Anniversary Reunion and Conference in the city. During commemorative events in February 2013 in Montgomery, Congressman

"Freedom Rides: Recollections by David Fankhauser"Freedom Rides of 1961

~ Civil Rights Movement Archive

''Get On the Bus: The Freedom Riders of 1961''

National Public Radio

NEVER-SEEN: MLK & the Freedom Rides

- slideshow by ''

''You Don't Have to Ride Jim Crow!''

New Hampshire Public Television/American Public Television documentary of the Journey of Reconciliation

''Eyes on the Prize''

Blackside, Inc./PBS documentary of the Civil Rights Movement (Episode 3 is the Freedom Rides)

"JFK, Freedom Riders, and the Civil Rights Movement"

EDSITEment lesson plan

"The Freedom Riders and the Popular Music of the Civil Rights"

EDSITEment lesson plan

Montgomery County Sheriff's Office, Alabama Department of Archives & History *

''

civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life o ...

activists who rode interstate buses into the segregated Southern United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

in 1961 and subsequent years to challenge the non-enforcement of the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

decisions '' Morgan v. Virginia'' (1946) and '' Boynton v. Virginia'' (1960), which ruled that segregated public buses were unconstitutional. The Southern states had ignored the rulings and the federal government did nothing to enforce them. The first Freedom Ride left Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

on May 4, 1961, and was scheduled to arrive in on May 17.

''Boynton'' outlawed racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crimes against hum ...

in the restaurants and waiting rooms in terminals serving buses that crossed state lines. Five years prior to the ''Boynton'' ruling, the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) had issued a ruling in '' Sarah Keys v. Carolina Coach Company'' (1955) that had explicitly denounced the ''Plessy v. Ferguson

''Plessy v. Ferguson'', 163 U.S. 537 (1896), was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision in which the Court ruled that racial segregation laws did not violate the U.S. Constitution as long as the facilities for each race were equal in qualit ...

'' (1896) doctrine of separate but equal

Separate but equal was a legal doctrine in United States constitutional law, according to which racial segregation did not necessarily violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which nominally guaranteed "equal protec ...

in interstate bus travel. The ICC failed to enforce its ruling, and Jim Crow travel laws remained in force throughout the South.

The Freedom Riders challenged this status quo by riding interstate buses in the South in mixed racial groups to challenge local laws or customs that enforced segregation in seating. The Freedom Rides, and the violent reactions they provoked, bolstered the credibility of the American Civil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the United ...

. They called national attention to the disregard for the federal law and the local violence used to enforce segregation in the southern United States. Police arrested riders for trespassing

Trespass is an area of tort law broadly divided into three groups: trespass to the person, trespass to chattels, and trespass to land.

Trespass to the person historically involved six separate trespasses: threats, assault, battery, wounding, ...

, unlawful assembly Unlawful assembly is a legal term to describe a group of people with the mutual intent of deliberate disturbance of the peace. If the group is about to start an act of disturbance, it is termed a rout; if the disturbance is commenced, it is then ter ...

, violating state and local Jim Crow laws, and other alleged offenses, but often they first let white mobs attack them without intervention.

The Congress of Racial Equality

The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) is an African-American civil rights organization in the United States that played a pivotal role for African Americans in the civil rights movement. Founded in 1942, its stated mission is "to bring about ...

(CORE) sponsored most of the subsequent Freedom Rides, but some were also organized by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The Freedom Rides, beginning in 1960, followed dramatic sit-ins against segregated lunch counters conducted by students and youth throughout the South, and boycotts of retail establishments that maintained segregated facilities.

The Supreme Court's decision in ''Boynton'' supported the right of interstate travelers to disregard local segregation ordinances. Southern local and state police considered the actions of the Freedom Riders to be criminal and arrested them in some locations. In some localities, such as Birmingham, Alabama

Birmingham ( ) is a city in the north central region of the U.S. state of Alabama. Birmingham is the seat of Jefferson County, Alabama's most populous county. As of the 2021 census estimates, Birmingham had a population of 197,575, down 1% fr ...

, the police cooperated with Ku Klux Klan chapters and other white people opposing the actions, and allowed mobs to attack the riders.

History

Prelude

The Freedom Riders were inspired by the 1947Journey of Reconciliation

The Journey of Reconciliation, also called "First Freedom Ride", was a form of nonviolent direct action to challenge state segregation laws on interstate buses in the Southern United States.

Bayard Rustin and 18 other men and women were the ea ...

, led by Bayard Rustin

Bayard Rustin (; March 17, 1912 – August 24, 1987) was an African American leader in social movements for civil rights, socialism, nonviolence, and gay rights.

Rustin worked with A. Philip Randolph on the March on Washington Movement, ...

and George Houser and co-sponsored by the Fellowship of Reconciliation

The Fellowship of Reconciliation (FoR or FOR) is the name used by a number of religious nonviolent organizations, particularly in English-speaking countries. They are linked by affiliation to the International Fellowship of Reconciliation (IFOR). ...

and the then-fledgling Congress of Racial Equality

The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) is an African-American civil rights organization in the United States that played a pivotal role for African Americans in the civil rights movement. Founded in 1942, its stated mission is "to bring about ...

(CORE). Like the Freedom Rides of 1961, the Journey of Reconciliation was intended to test an earlier Supreme Court ruling that banned racial discrimination

Racial discrimination is any discrimination against any individual on the basis of their skin color, race or ethnic origin.Individuals can discriminate by refusing to do business with, socialize with, or share resources with people of a certain g ...

in interstate travel. Rustin, Igal Roodenko, Joe Felmet and Andrew Johnnson, were arrested and sentenced to serve on a chain gang in North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and ...

for violating local Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

regarding segregated seating on public transportation.

The first Freedom Ride began on May 4, 1961. Led by CORE Director James Farmer

James Leonard Farmer Jr. (January 12, 1920 – July 9, 1999) was an American civil rights activist and leader in the Civil Rights Movement "who pushed for nonviolent protest to dismantle segregation, and served alongside Martin Luther King Jr." ...

, 13 young riders (seven black, six white, including but not limited to John Lewis

John Robert Lewis (February 21, 1940 – July 17, 2020) was an American politician and civil rights activist who served in the United States House of Representatives for from 1987 until his death in 2020. He participated in the 1960 Nashville ...

(21), Genevieve Hughes

Genevieve Hughes Houghton ("HOW-ton"; 1932–2012) is known as one of three women participants in the original 13-person Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) Freedom Rides.

Biography

Hughes grew up in the upper-middle-class suburban community of ...

(28), Mae Frances Moultrie, Joseph Perkins, Charles Person (18), Ivor Moore, William E. Harbour (19), Joan Trumpauer Mullholland (19), and Ed Blankenheim). left Washington, DC, on Greyhound

The English Greyhound, or simply the Greyhound, is a breed of dog, a sighthound which has been bred for coursing, greyhound racing and hunting. Since the rise in large-scale adoption of retired racing Greyhounds, the breed has seen a resurgenc ...

(from the Greyhound Terminal) and Trailways

The Trailways Transportation System is an American network of approximately 70 independent bus companies that have entered into a brand licensing agreement. The company is headquartered in Fairfax, Virginia.

History

The predecessor to Trailwa ...

buses. Their plan was to ride through Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, the Carolinas, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,765 ...

, and Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

, ending in , where a civil rights rally was planned. Many of the Riders were sponsored by CORE and SNCC

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, often pronounced ) was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Emerging in 1960 from the student-led sit-ins at segreg ...

with 75% of the Riders between 18 and 30 years old. A diverse group of volunteers came from 39 states, and were from different economic classes and racial backgrounds. Most were college students and received training in nonviolent tactics.

The Freedom Riders' tactics for their journey were to have at least one interracial pair sitting in adjoining seats, and at least one black rider sitting up front, where seats under segregation had been reserved for white customers by local custom throughout the South. The rest of the team would sit scattered throughout the rest of the bus. One rider would abide by the South's segregation rules in order to avoid arrest and to contact CORE and arrange bail for those who were arrested.

Only minor trouble was encountered in Virginia and North Carolina, but John Lewis

John Robert Lewis (February 21, 1940 – July 17, 2020) was an American politician and civil rights activist who served in the United States House of Representatives for from 1987 until his death in 2020. He participated in the 1960 Nashville ...

was attacked in Rock Hill, South Carolina

Rock Hill is the largest city in York County, South Carolina and the fifth-largest city in the state. It is also the fourth-largest city of the Charlotte metropolitan area, behind Charlotte, Concord, and Gastonia (all located in North Carolina, ...

. Over 300 Riders were arrested in Charlotte, North Carolina

Charlotte ( ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of North Carolina. Located in the Piedmont region, it is the county seat of Mecklenburg County. The population was 874,579 at the 2020 census, making Charlotte the 16th-most populo ...

; Winnsboro, South Carolina

Winnsboro is a town in Fairfield County, South Carolina, United States. The population was 3,550 at the 2010 census. The population was 3,215 at the 2020 census. A population decrease of approximately 9.5% for the same 10 year period. It is the c ...

; and Jackson, Mississippi

Jackson, officially the City of Jackson, is the capital of and the most populous city in the U.S. state of Mississippi. The city is also one of two county seats of Hinds County, along with Raymond. The city had a population of 153,701 at t ...

.

Mob violence in Anniston and Birmingham

TheBirmingham, Alabama

Birmingham ( ) is a city in the north central region of the U.S. state of Alabama. Birmingham is the seat of Jefferson County, Alabama's most populous county. As of the 2021 census estimates, Birmingham had a population of 197,575, down 1% fr ...

, Police Commissioner, Bull Connor

Theophilus Eugene "Bull" Connor (July 11, 1897 – March 10, 1973) was an American politician who served as Commissioner of Public Safety for the city of Birmingham, Alabama, for more than two decades. A member of the Democratic Party, ...

, together with Police Sergeant Tom Cook (an avid Ku Klux Klan supporter), organized violence against the Freedom Riders with local Klan chapters. The pair made plans to bring the Ride to an end in Alabama. They assured Gary Thomas Rowe

Gary Thomas Rowe Jr. (August 13, 1933 – May 25, 1998), known in Witness Protection as Thomas Neil Moore, was a paid informant and agent provocateur for the FBI. As an informant, he infiltrated the Ku Klux Klan, as part of the FBI's COINTELPRO ...

, an FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, t ...

informer and member of Eastview Klavern #13 (the most violent Klan group in Alabama), that the mob would have fifteen minutes to attack the Freedom Riders without any arrests being made. The plan was to allow an initial assault in Anniston with a final assault taking place in Birmingham.

Anniston

On Sunday, May 14, 1961, Mother's Day, in Anniston, Alabama, a mob of Klansmen, some still in church attire, attacked the first of the two Greyhound buses. The driver tried to leave the station, but he was blocked until KKK members slashed its tires. The mob forced the crippled bus to stop several miles outside town and then threw a firebomb into it. As the bus burned, the mob held the doors shut, intending to burn the riders to death. Sources disagree, but either an explodingfuel tank

A fuel tank (also called a petrol tank or gas tank) is a safe container for flammable fluids. Though any storage tank for fuel may be so called, the term is typically applied to part of an engine system in which the fuel is stored and propelle ...

or an undercover state investigator who was brandishing a revolver caused the mob to retreat, and the riders escaped the bus. The mob beat the riders after they got out. Warning shots which were fired into the air by highway patrolmen were the only thing which prevented the riders from being lynched

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged transgressor, punish a convicted transgressor, or intimidate people. It can also be an ex ...

. The roadside site in Anniston and the downtown Greyhound station were preserved as part of the Freedom Riders National Monument in 2017.

Some injured riders were taken to Anniston Memorial Hospital. That night, the hospitalized Freedom Riders, most of whom had been refused care, were removed from the hospital at 2 AM, because the staff feared the mob outside the hospital. The local civil rights leader Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth organized several cars of black citizens to rescue the injured Freedom Riders in defiance of the white supremacists. The black people were under the leadership of Colonel Stone Johnson and were openly armed as they arrived at the hospital, protecting the Freedom Riders from the mob.

When the Trailways bus reached Anniston and pulled in at the terminal an hour after the Greyhound bus was burned, it was boarded by eight Klansmen. They beat the Freedom Riders and left them semi-conscious in the back of the bus.

Birmingham

When the bus arrived in Birmingham, it was attacked by a mob of KKK members aided and abetted by police under the orders of Commissioner Connor.Freedom Rides

When the bus arrived in Birmingham, it was attacked by a mob of KKK members aided and abetted by police under the orders of Commissioner Connor.Freedom Rides~ Civil Rights Movement Archive. As the riders exited the bus, they were beaten by the mob with baseball bats, iron

pipe

Pipe(s), PIPE(S) or piping may refer to:

Objects

* Pipe (fluid conveyance), a hollow cylinder following certain dimension rules

** Piping, the use of pipes in industry

* Smoking pipe

** Tobacco pipe

* Half-pipe and quarter pipe, semi-circular ...

s and bicycle chains. Among the attacking Klansmen was Gary Thomas Rowe

Gary Thomas Rowe Jr. (August 13, 1933 – May 25, 1998), known in Witness Protection as Thomas Neil Moore, was a paid informant and agent provocateur for the FBI. As an informant, he infiltrated the Ku Klux Klan, as part of the FBI's COINTELPRO ...

, an FBI informant. White Freedom Riders were singled out for especially frenzied beatings; James Peck required more than 50 stitches to the wounds in his head. Peck was taken to Carraway Methodist Medical Center

Carraway Methodist Medical Center was a medical facility in Birmingham, Alabama founded as Carraway Infirmary in 1908 by Dr. Charles N. Carraway. It was moved in 1917 to Birmingham's Norwood neighborhood. Its facilities were Racial segregation, se ...

, which refused to treat him; he was later treated at Jefferson Hillman Hospital.

When reports of the bus burning and beatings reached US Attorney General

The United States attorney general (AG) is the head of the United States Department of Justice, and is the chief law enforcement officer of the federal government of the United States. The attorney general serves as the principal advisor to the p ...

Robert F. Kennedy

Robert Francis Kennedy (November 20, 1925June 6, 1968), also known by his initials RFK and by the nickname Bobby, was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 64th United States Attorney General from January 1961 to September 1964, ...

, he urged restraint on the part of Freedom Riders and sent an assistant, John Seigenthaler, to Alabama to try to calm the situation.

Despite the violence suffered and the threat of more to come, the Freedom Riders intended to continue their journey. Kennedy had arranged an escort for the Riders in order to get them to Montgomery, Alabama

Montgomery is the capital city of the U.S. state of Alabama and the county seat of Montgomery County. Named for the Irish soldier Richard Montgomery, it stands beside the Alabama River, on the coastal Plain of the Gulf of Mexico. In the 202 ...

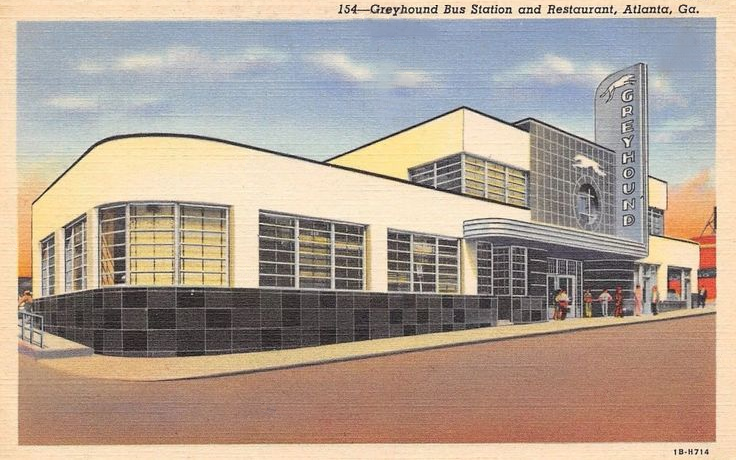

, safely. However, radio reports told of a mob awaiting the riders at the bus terminal, as well as on the route to Montgomery. The Greyhound clerks told the Riders that their drivers were refusing to drive any Freedom Riders anywhere.

New Orleans

Recognizing that their efforts had already called national attention to the civil rights cause and wanting to get to the rally in New Orleans, the Riders decided to abandon the rest of the bus ride and fly directly to New Orleans from Birmingham. When they first boarded the plane, all passengers had to exit because of a bomb threat. Upon arriving in New Orleans, local tensions prevented normal accommodations—after which Norman C. Francis, president ofXavier University of Louisiana

Xavier University of Louisiana (also known as XULA) is a private, historically black, Catholic university in New Orleans, Louisiana. It is the only Catholic HBCU and, upon the canonization of Katharine Drexel in 2000, became the first Cathol ...

(XULA), decided to house them on campus in secret at St Michael's Hall, a dormitory.

Nashville Student Movement continuation

Diane Nash

Diane Judith Nash (born May 15, 1938) is an American civil rights activist, and a leader and strategist of the student wing of the Civil Rights Movement.

Nash's campaigns were among the most successful of the era. Her efforts included the first s ...

, a Nashville college student who was a leader of the Nashville Student Movement and SNCC

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, often pronounced ) was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Emerging in 1960 from the student-led sit-ins at segreg ...

, believed that if Southern violence were allowed to halt the Freedom Rides the movement would be set back years. She pushed to find replacements to resume the rides. On May 17, a new set of riders, 10 students from Nashville who were active in the Nashville Student Movement, took a bus to Birmingham, where they were arrested by Bull Connor and jailed.

The students kept their spirits up in jail by singing freedom songs. Out of frustration, Connor drove them back up to the Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

line and dropped them off, saying, "I just couldn't stand their singing." They immediately returned to Birmingham.

Mob violence in Montgomery

In answer to SNCC's call, Freedom Riders from across the Eastern US joinedJohn Lewis

John Robert Lewis (February 21, 1940 – July 17, 2020) was an American politician and civil rights activist who served in the United States House of Representatives for from 1987 until his death in 2020. He participated in the 1960 Nashville ...

and Hank Thomas, the two young SNCC members of the original Ride, who had remained in Birmingham. On May 19, they attempted to resume the ride, but, terrified by the howling mob surrounding the bus depot, the drivers refused. Harassed and besieged by the mob, the riders waited all night for a bus.

Under intense public pressure from the Kennedy administration

John F. Kennedy's tenure as the 35th president of the United States, began with his inauguration on January 20, 1961, and ended with his assassination on November 22, 1963. A Democrat from Massachusetts, he took office following the 1960 ...

, Greyhound was forced to provide a driver. After direct intervention by Byron White

Byron "Whizzer" Raymond White (June 8, 1917 April 15, 2002) was an American professional football player and jurist who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1962 until his retirement in 1993.

Born and raised in Colo ...

of the Attorney General's office, Alabama Governor John Patterson reluctantly promised to protect the bus from KKK mobs and snipers on the road between Birmingham and Montgomery. On the morning of May 20, the Freedom Ride resumed, with the bus carrying the riders traveling toward Montgomery at 90 miles an hour, protected by a contingent of the Alabama State Highway Patrol.

The Highway Patrol abandoned the bus and riders at the Montgomery city limits. At the Montgomery Greyhound station on South Court Street, a white mob awaited. They beat the Freedom Riders with baseball bats and iron pipes. The local police allowed the beatings to go on uninterrupted. Again, white Freedom Riders were singled out for particularly brutal beatings. Reporters and news photographers were attacked first and their cameras destroyed, but one reporter took a photo later of Jim Zwerg in the hospital, showing how he was beaten and bruised. Seigenthaler, a Justice Department official, was beaten and left unconscious lying in the street. Ambulances refused to take the wounded to the hospital. Local black residents rescued them, and a number of the Freedom Riders were hospitalized.

On the following night, Sunday, May 21, more than 1500 people packed into Reverend Ralph Abernathy's First Baptist Church to honor the Freedom Riders. Among the speakers were Rev.

The Highway Patrol abandoned the bus and riders at the Montgomery city limits. At the Montgomery Greyhound station on South Court Street, a white mob awaited. They beat the Freedom Riders with baseball bats and iron pipes. The local police allowed the beatings to go on uninterrupted. Again, white Freedom Riders were singled out for particularly brutal beatings. Reporters and news photographers were attacked first and their cameras destroyed, but one reporter took a photo later of Jim Zwerg in the hospital, showing how he was beaten and bruised. Seigenthaler, a Justice Department official, was beaten and left unconscious lying in the street. Ambulances refused to take the wounded to the hospital. Local black residents rescued them, and a number of the Freedom Riders were hospitalized.

On the following night, Sunday, May 21, more than 1500 people packed into Reverend Ralph Abernathy's First Baptist Church to honor the Freedom Riders. Among the speakers were Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

, who had led the 1955–1956 Montgomery bus boycott

The Montgomery bus boycott was a political and social protest campaign against the policy of racial segregation on the public transit system of Montgomery, Alabama. It was a foundational event in the civil rights movement in the United States ...

, Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, and James Farmer

James Leonard Farmer Jr. (January 12, 1920 – July 9, 1999) was an American civil rights activist and leader in the Civil Rights Movement "who pushed for nonviolent protest to dismantle segregation, and served alongside Martin Luther King Jr." ...

. Outside, a mob of more than 3,000 white people attacked the black attendees, with a handful of the United States Marshals Service

The United States Marshals Service (USMS) is a federal law enforcement agency in the United States. The USMS is a bureau within the U.S. Department of Justice, operating under the direction of the Attorney General, but serves as the enforc ...

protecting the church from assault and fire bombs. With city and state police making no effort to restore order, the civil rights leaders appealed to the President for protection. President Kennedy threatened to intervene with federal troops if the governor would not protect the people. Governor Patterson forestalled that by finally ordering the Alabama National Guard

The Alabama National Guard is the National Guard of the U.S State of Alabama, and consists of the Alabama Army National Guard and the Alabama Air National Guard. (The Alabama State Defense Force is the third military unit of the Alabama Milita ...

to disperse the mob, and the Guard reached the church in the early morning.

In a commemorative Op-Ed piece in 2011,

In a commemorative Op-Ed piece in 2011, Bernard Lafayette

use both this parameter and , birth_date to display the person's date of birth, date of death, and age at death) -->

, death_place =

, death_cause =

, body_discovered =

, resting_place =

, resting_place_coordinates = ...

remembered the mob breaking windows of the church with rocks and setting off tear gas canisters. He recounted heroic action by King. After learning that black taxi drivers were arming and forming a group to rescue the people inside, he worried that more violence would result. He selected ten volunteers, who promised non-violence, to escort him through the white mob, which parted to let King and his escorts pass as they marched two by two. King went out to the black drivers and asked them to disperse, to prevent more violence. King and his escorts formally made their way back inside the church, unmolested. Lafayette also was interviewed by the BBC in 2011 and told about these events in an episode broadcast on the radio on August 31, 2011, in commemoration of the Freedom Rides. The Alabama National Guard finally arrived in the early morning to disperse the mob and safely escorted all the people from the church.

Into Mississippi

Jackson, Mississippi

Jackson, officially the City of Jackson, is the capital of and the most populous city in the U.S. state of Mississippi. The city is also one of two county seats of Hinds County, along with Raymond. The city had a population of 153,701 at t ...

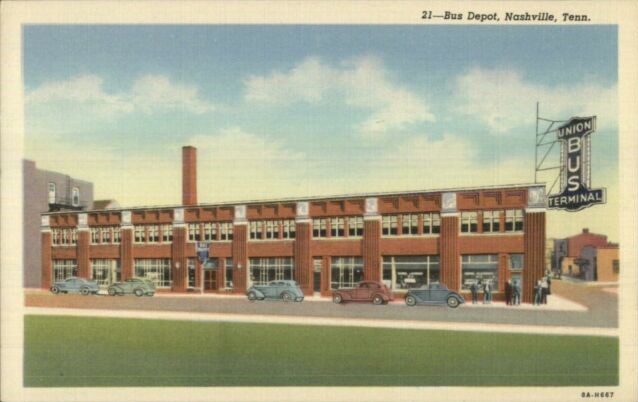

. Surrounded by Highway Patrol and the National Guard, the buses arrived in Jackson without incident, but the riders were immediately arrested when they tried to use the white-only facilities at the Tri-State Trailways depot. The third bus arrived at the Jackson Greyhound station early on May 28, and its Freedom Riders were arrested.

In Montgomery, the next round of Freedom Riders, including the Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Sta ...

chaplain William Sloane Coffin

William Sloane Coffin Jr. (June 1, 1924 – April 12, 2006) was an American Christian clergyman and long-time peace activist. He was ordained in the Presbyterian Church, and later received ministerial standing in the United Church of Christ. In h ...

, Gaylord Brewster Noyce, and southern ministers Shuttlesworth, Abernathy, Wyatt Tee Walker

Wyatt Tee Walker (August 16, 1928 – January 23, 2018) was an African-American pastor, national civil rights leader, theologian, and cultural historian. He was a chief of staff for Martin Luther King Jr., and in 1958 became an early board memb ...

, and others were similarly arrested for violating local segregation ordinances.

This established a pattern followed by subsequent Freedom Rides, most of which traveled to Jackson, where the Riders were arrested and jailed. Their strategy became one of trying to fill the jails. Once the Jackson and Hinds County jails were filled to overflowing, the state transferred the Freedom Riders to the infamous Mississippi State Penitentiary (known as Parchman Farm). Abusive treatment there included placement of Riders in the Maximum Security Unit ( Death Row), issuance of only underwear, no exercise, and no mail privileges. When the Freedom Riders refused to stop singing freedom songs, prison officials took away their mattresses, sheets, and toothbrushes. More Freedom Riders arrived from across the country, and at one time, more than 300 were held in Parchman Farm.

Riders arrested in Jackson included Stokley Carmichael (19), Catherine Burks (21), Gloria Bouknight (20), Luvahgn Brown (16), Margaret Leonard (19), Helen O'Neal (20), Hank Thomas (20), Carol Silver (22), Hezekiah Watkins (13), Peter Stoner (22), Byron Baer (31), and LeRoy Glenn Wright (19) in addition to many more

While in Jackson, Freedom Riders received support from local grassroots civil rights organization Womanpower Unlimited, which raised money and collected toiletries, soap, candy and magazines for the imprisoned protesters. Upon Freedom Riders' release, Womanpower members would provide places for them to bathe while offering them clothes and food. Founded by Clarie Collins Harvey, the group was considered instrumental in the success of the Freedom Riders. Freedom Rider Joan Trumpauer Mulholland said the Womanpower members "were like angels supplying us with just little simple necessities."

Kennedy urges "cooling off period"

The Kennedys called for a "cooling off period" and condemned the Rides as unpatriotic because they embarrassed the nation on the world stage at the height of the Cold War.James Farmer

James Leonard Farmer Jr. (January 12, 1920 – July 9, 1999) was an American civil rights activist and leader in the Civil Rights Movement "who pushed for nonviolent protest to dismantle segregation, and served alongside Martin Luther King Jr." ...

, head of CORE, responded to Kennedy saying, "We have been cooling off for 350 years, and if we cooled off any more, we'd be in a deep freeze." The Soviet Union criticized the United States for its racism and the attacks on the Riders.

Nonetheless, international outrage about the widely covered events and racial violence created pressure on American political leaders. On May 29, 1961, Attorney General Kennedy sent a petition to the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) asking it to comply with the bus-desegregation ruling it had issued in November 1955, in '' Sarah Keys v. Carolina Coach Company''. That ruling had explicitly repudiated the concept of "separate but equal

Separate but equal was a legal doctrine in United States constitutional law, according to which racial segregation did not necessarily violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which nominally guaranteed "equal protec ...

" in the realm of interstate bus travel. Chaired by the South Carolina Democrat J. Monroe Johnson the ICC had failed to implement its own ruling.

Summer escalation

CORE, SNCC, and the SCLC rejected any "cooling off period". They formed a Freedom Riders Coordinating Committee to keep the Rides rolling through June, July, August, and September. During those months, more than 60 different Freedom Rides criss-crossed the South, most of them converging on Jackson, where every Rider was arrested, more than 300 in total. An unknown number were arrested in other Southern towns. It is estimated that almost 450 people participated in one or more Freedom Rides. About 75% were male, and the same percentage were under the age of 30, with about equal participation from black and white citizens.

During the summer of 1961, Freedom Riders also campaigned against other forms of

CORE, SNCC, and the SCLC rejected any "cooling off period". They formed a Freedom Riders Coordinating Committee to keep the Rides rolling through June, July, August, and September. During those months, more than 60 different Freedom Rides criss-crossed the South, most of them converging on Jackson, where every Rider was arrested, more than 300 in total. An unknown number were arrested in other Southern towns. It is estimated that almost 450 people participated in one or more Freedom Rides. About 75% were male, and the same percentage were under the age of 30, with about equal participation from black and white citizens.

During the summer of 1961, Freedom Riders also campaigned against other forms of racial discrimination

Racial discrimination is any discrimination against any individual on the basis of their skin color, race or ethnic origin.Individuals can discriminate by refusing to do business with, socialize with, or share resources with people of a certain g ...

. They sat together in segregated restaurants, lunch counters and hotels. This was especially effective when they targeted large companies, such as hotel chains. Fearing boycotts in the North, the hotels began to desegregate their businesses.

Tallahassee

In mid-June, a group of Freedom Riders had scheduled to end their ride inTallahassee, Florida

Tallahassee ( ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Florida. It is the county seat and only incorporated municipality in Leon County. Tallahassee became the capital of Florida, then the Florida Territory, in 1824. In 2020, the populatio ...

, with plans to fly home from the Tallahassee Municipal Airport. They were provided a police escort to the airport from the city's bus facilities. At the airport, they decided to eat at the ''Savarin'' restaurant that was marked "For Whites Only". The owners decided to close rather than serve the mixed group of Freedom Riders. Although the restaurant was privately owned, it was leased from the county government. Canceling their plane reservations, the Riders decided to wait until the restaurant re-opened so they could be served. They waited until 11:00 pm that night and returned the following day. During this time, hostile crowds gathered, threatening violence. On June 16, 1961, the Freedom Riders were arrested in Tallahassee for unlawful assembly. That arrest and subsequent trial became known as ''Dresner v. City of Tallahassee,'' named for Israel S. Dresner, a rabbi among the group arrested. The Riders were convicted of unlawful assembly by the Municipal Court of Tallahassee, and the convictions were affirmed in the Florida Circuit Court of the Second Judicial District.

The convictions were appealed to the US Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point of ...

in 1963, which refused to hear the case based on jurisdictional reasons. In 1964, the ''Tallahassee 10'' protesters returned to the city to serve brief jail sentences.

Monroe, North Carolina, and Robert F. Williams

In early August, SNCC staff membersJames Forman

James Forman (October 4, 1928 – January 10, 2005) was a prominent African-American leader in the civil rights movement. He was active in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Black Panther Party, and the League of Revolutio ...

and Paul Brooks, with the support of Ella Baker

Ella Josephine Baker (December 13, 1903 – December 13, 1986) was an African-American civil rights and human rights activist. She was a largely behind-the-scenes organizer whose career spanned more than five decades. In New York City and t ...

, began planning a Freedom Ride in solidarity with Robert F. Williams. Williams was an extremely militant and controversial NAACP chapter president for Monroe, North Carolina. After making the public statement that he would "meet violence with violence," (since the federal government would not protect his community from racial attacks) he had been suspended by the NAACP national board over the objections of Williams' local membership. Williams continued his work against segregation however, but now had massive opposition in both black and white communities. He was also facing repeated attempts on his life because of it. Some SNCC staff members sympathized with the idea of armed self-defense, although many on the ride to Monroe saw this as an opportunity to prove the superiority of Gandhian nonviolence over the use of force. Forman was among those who were still supportive of Williams.

The Freedom Riders in Monroe were brutally attacked by white supremacists with the approval of local police. On August 27, James Forman - SNCC's Executive Secretary - was struck unconscious with the butt of a rifle and taken to jail with numerous other demonstrators. Police and white supremacists roamed the town shooting at black civilians, who returned the gunfire. Robert F. Williams fortified the black neighborhood against attack and in the process briefly detained a white couple who had gotten lost there. The police accused Williams of kidnapping and called in the state militia and FBI to arrest him, in spite of the couple being quickly released. Certain he would be lynched, Williams fled and eventually found refuge in Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

. Movement lawyers, eager to disengage from the situation, successfully urged the Freedom Riders not to practice the normal "jail-no bail" strategy in Monroe. Local officials, also apparently eager to de-escalate, found demonstrators guilty but immediately suspended their sentences. One Freedom Rider however, John Lowry, went on trial for the kidnapping case, along with several associates of Robert F. Williams, including Mae Mallory. Monroe legal defense committees were popular around the country, but ultimately Lowry and Mallory served prison sentences. In 1965, their convictions were vacated due to the exclusion of black citizens from the jury selection.

Jackson, Mississippi, and ''Pierson v. Ray''

On September 13, 1961, a group of 15 Episcopal priests including 3 black priests entered theJackson, Mississippi

Jackson, officially the City of Jackson, is the capital of and the most populous city in the U.S. state of Mississippi. The city is also one of two county seats of Hinds County, along with Raymond. The city had a population of 153,701 at t ...

Trailways

The Trailways Transportation System is an American network of approximately 70 independent bus companies that have entered into a brand licensing agreement. The company is headquartered in Fairfax, Virginia.

History

The predecessor to Trailwa ...

bus terminal. Upon entering the coffee shop, they were stopped by two policemen, who asked them to leave. After refusing to leave, all 15 were arrested and jailed for breach of peace, under a now-repealed section of the Mississippi code § 2087.5 that "makes guilty of a misdemeanor anyone who congregates with others in a public place under circumstances such that a breach of the peace may be occasioned thereby, and refuses to move on when ordered to do so by a police officer."

The group included 35-year-old Reverend Robert L Pierson. After the case against the priests was dismissed on May 21, 1962, they sought damages against the police under the Civil Rights Act of 1871

The Enforcement Act of 1871 (), also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act, Third Enforcement Act, Third Ku Klux Klan Act, Civil Rights Act of 1871, or Force Act of 1871, is an Act of the United States Congress which empowered the President to suspend ...

. Their claims were ultimately rejected in the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

case '' Pierson v. Ray'' (1967), which held that the police were protected by qualified immunity.

Resolution and legacy

By September it had been over three months since the filing of the petition by Robert Kennedy. CORE and SNCC leaders made tentative plans for a mass demonstration known as the "Washington Project". This would mobilize hundreds, perhaps thousands, of nonviolent demonstrators to the capital city to apply pressure on the ICC and the Kennedy administration. The idea was pre-empted when the ICC finally issued the necessary orders just before the end of the month. The new policies went into effect on November 1, 1961, six years after the ruling in '' Sarah Keys v. Carolina Coach Company''. After the new ICC rule took effect, passengers were permitted to sit wherever they pleased on interstate buses and trains; "white" and "colored" signs were removed from the terminals; racially-segregated drinking fountains, toilets, and waiting rooms serving interstate customers were consolidated; and the lunch counters began serving all customers, regardless of race. The widespread violence provoked by the Freedom Rides sent shock waves through American society. People were worried that the Rides were evoking widespread social disorder and racial divergence, an opinion supported and strengthened in many communities by the press. The press in white communities condemned the direct action approach that CORE was taking, while some of the national press negatively portrayed the Riders as provoking unrest. At the same time, the Freedom Rides established great credibility with black and white people throughout the United States and inspired many to engage in direct action for civil rights. Perhaps most significantly, the actions of the Freedom Riders from the North, who faced danger on behalf of southern black citizens, impressed and inspired the many black people living inrural

In general, a rural area or a countryside is a geographic area that is located outside towns and cities. Typical rural areas have a low population density and small settlements. Agricultural areas and areas with forestry typically are descri ...

areas throughout the South. They formed the backbone of the wider civil rights movement, engaging in voter registration

In electoral systems, voter registration (or enrollment) is the requirement that a person otherwise eligible to vote must register (or enroll) on an electoral roll, which is usually a prerequisite for being entitled or permitted to vote.

The r ...

and other activities. Southern black activists generally organized around their churches, the center of their communities and a base of moral strength.

The Freedom Riders helped inspire participation in subsequent civil rights campaigns, including voter registration throughout the South, freedom schools, and the Black Power movement. At the time, most black Southerners had been unable to register to vote, due to state constitutions, laws and practices that had effectively disfranchised them since the turn of the 20th century. For instance, white administrators supervised reading comprehension and literacy tests that highly educated black people could not pass.

List of Freedom Rides

Precursors to Freedom Rides

Original and subsequent Freedom Rides

:'' Denotes location a Freedom Rider tested the compliance of the Boynton v. Virginia (1960) decision at a terminal facility only''

Mississippi Freedom Rides

:'' Denotes location a Freedom Rider tested the compliance of the Boynton v. Virginia (1960) decision at a terminal facility only''

Commemorations and monument

In celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Freedom Rides, Oprah Winfrey invited all living Freedom Riders to join her TV program to celebrate their legacy. The episode aired on May 4, 2011.

On May 6–16, 2011, 40 college students from across the United States embarked on a bus ride from Washington, D.C. to New Orleans, retracing the original route of the Freedom Riders. The 2011 Student Freedom Ride, which was sponsored by PBS and ''American Experience'', commemorated the 50th anniversary of the original Freedom Rides. Students met with civil rights leaders along the way and traveled with original Freedom Riders such as Ernest "Rip" Patton, Joan Mulholland, Bob Singleton, Helen Singleton, Jim Zwerg, and Charles Person. On May 16, 2011, PBS aired a documentary called '' Freedom Riders''.

On May 19–21, 2011, the Freedom Rides were commemorated in Montgomery, Alabama, at the new Freedom Ride Museum in the old Greyhound Bus terminal, where some of the violence had taken place in 1961. On May 22–26, 2011, the arrival of the Freedom Rides in Jackson, Mississippi was commemorated with a 50th Anniversary Reunion and Conference in the city. During commemorative events in February 2013 in Montgomery, Congressman

In celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Freedom Rides, Oprah Winfrey invited all living Freedom Riders to join her TV program to celebrate their legacy. The episode aired on May 4, 2011.

On May 6–16, 2011, 40 college students from across the United States embarked on a bus ride from Washington, D.C. to New Orleans, retracing the original route of the Freedom Riders. The 2011 Student Freedom Ride, which was sponsored by PBS and ''American Experience'', commemorated the 50th anniversary of the original Freedom Rides. Students met with civil rights leaders along the way and traveled with original Freedom Riders such as Ernest "Rip" Patton, Joan Mulholland, Bob Singleton, Helen Singleton, Jim Zwerg, and Charles Person. On May 16, 2011, PBS aired a documentary called '' Freedom Riders''.

On May 19–21, 2011, the Freedom Rides were commemorated in Montgomery, Alabama, at the new Freedom Ride Museum in the old Greyhound Bus terminal, where some of the violence had taken place in 1961. On May 22–26, 2011, the arrival of the Freedom Rides in Jackson, Mississippi was commemorated with a 50th Anniversary Reunion and Conference in the city. During commemorative events in February 2013 in Montgomery, Congressman John Lewis

John Robert Lewis (February 21, 1940 – July 17, 2020) was an American politician and civil rights activist who served in the United States House of Representatives for from 1987 until his death in 2020. He participated in the 1960 Nashville ...

accepted the apologies of Chief Kevin Murphy of the Montgomery Police Department; Murphy gave Lewis his own badge, off his uniform, moving Lewis to tears.

In late 2011, Palestinian activists, inspired by the Freedom Riders, used the same methods in Israel by boarding a bus from which they were excluded.

In January, 2017, President Barack Obama declared the Anniston, Alabama bus station the Freedom Riders National Monument.

Cultural depictions

The 1980sPBS

The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) is an American public broadcaster and non-commercial, free-to-air television network based in Arlington, Virginia. PBS is a publicly funded nonprofit organization and the most prominent provider of educat ...

series, '' Eyes on the Prize,'' had an episode, "Ain't Scared of Your Jails: 1960-1961," which gave attention to the Freedom Riders. It included an interview with James Farmer.

The title of the 2007 film ''Freedom Writers

''Freedom Writers'' is a 2007 American drama film written and directed by Richard LaGravenese and starring Hilary Swank, Scott Glenn, Imelda Staunton, Patrick Dempsey and Mario.

It is based on the 1999 book '' The Freedom Writers Diary'' by te ...

'' is an explicit pun on the Freedom Riders, a fact made clear in the film itself which references the campaign.

PBS in 2012 broadcast ''Freedom Riders'' as part of its ''American Experience

''American Experience'' is a television program airing on the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) in the United States. The program airs documentaries, many of which have won awards, about important or interesting events and people in American his ...

'' series. It included interviews and news footage from the Freedom Riders movement.

Dan Shore

Dan Shore (born 1975) is an American composer and playwright from Allentown, Pennsylvania, whose works include ''The Beautiful Bridegroom'', '' An Embarrassing Position'', ''Travel'', ''Works of Mercy'', and ''Lady Orchid''.

Education

Shore atte ...

's 2013 opera ''Freedom Ride'', set in New Orleans, celebrates the Freedom Riders.

'' The Boondocks'' aired a 2014 episode about the Freedom Rides with the title "Freedom Ride or Die".

''The Freedom Riders: The Civil Rights Musical'' is a theater musical retelling the story of the Freedom Rides. The musical was created by Los Angeles screenwriter/director Richard Allen, and San Diego native music artist Taran Gray. Richard and Taran finalized the music in March 2016, and by April of the same year were asked to perform excerpts from their musical as a BETA Event at the New York Musical Festival (NYMF). The FREEDOM RIDERS musical received NYMF's inaugural BETA Event Award, and is scheduled to return to New York, summer of 2017, for an Off-Broadway run as part of NYMF's festival.

Notable Freedom Riders

* Zev Aelony *James Bevel

James Luther Bevel (October 19, 1936 – December 19, 2008) was a minister and leader of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement in the United States. As a member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and then as its Director of Direct ...

* Albert Bigelow

* Malcolm Boyd

* Amos C. Brown

*Gordon Carey

Gordon Ray Carey (January 7, 1932 – November 27, 2021) was an American civil rights worker and Freedom Rider.

Life

Carey was born on January 7, 1932, in Grand Rapids, Michigan to Marguerite (Jellema) Carey and Howard Ray Carey. His mother was ...

*Stokely Carmichael

Kwame Ture (; born Stokely Standiford Churchill Carmichael; June 29, 1941November 15, 1998) was a prominent organizer in the civil rights movement in the United States and the global pan-African movement. Born in Trinidad, he grew up in the Unite ...

*William Sloane Coffin

William Sloane Coffin Jr. (June 1, 1924 – April 12, 2006) was an American Christian clergyman and long-time peace activist. He was ordained in the Presbyterian Church, and later received ministerial standing in the United Church of Christ. In h ...

* Israel S. Dresner

*James Farmer

James Leonard Farmer Jr. (January 12, 1920 – July 9, 1999) was an American civil rights activist and leader in the Civil Rights Movement "who pushed for nonviolent protest to dismantle segregation, and served alongside Martin Luther King Jr." ...

*Bob Filner

Robert Earl "Bob" Filner (born September 4, 1942) is an American former politician who was the 35th mayor of San Diego from December 2012 through August 2013, when he resigned amid multiple allegations of sexual harassment. He later pleaded gui ...

*James Forman

James Forman (October 4, 1928 – January 10, 2005) was a prominent African-American leader in the civil rights movement. He was active in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Black Panther Party, and the League of Revolutio ...

* Tom Hayden

* Mary Hamilton

* William E. Harbour

*Genevieve Hughes

Genevieve Hughes Houghton ("HOW-ton"; 1932–2012) is known as one of three women participants in the original 13-person Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) Freedom Rides.

Biography

Hughes grew up in the upper-middle-class suburban community of ...

*Bernard Lafayette

use both this parameter and , birth_date to display the person's date of birth, date of death, and age at death) -->

, death_place =

, death_cause =

, body_discovered =

, resting_place =

, resting_place_coordinates = ...

* James Lawson

* Frederick Leonard

*John Lewis

John Robert Lewis (February 21, 1940 – July 17, 2020) was an American politician and civil rights activist who served in the United States House of Representatives for from 1987 until his death in 2020. He participated in the 1960 Nashville ...

* Robert Martinson

* Salynn McCollum

* Charles McDew

* Winonah Myers

*Diane Nash

Diane Judith Nash (born May 15, 1938) is an American civil rights activist, and a leader and strategist of the student wing of the Civil Rights Movement.

Nash's campaigns were among the most successful of the era. Her efforts included the first s ...

* Wally Nelson

* James Peck

* Charles Person

* Robert Laughlin Pierson

* John Curtis Raines

* Cordell Reagon

* Meryle Joy Reagon

* Charles Grier Sellers

* Charles Sherrod

* Fred Shuttlesworth

* Carol Ruth Silver

* Helen Singleton

* George Bundy Smith

* Ruby Doris Smith-Robinson

* Peter Sterling

* Daniel N. Stern

* Hank Thomas

* Joan Trumpauer Mulholland

* C. T. Vivian

*Wyatt Tee Walker

Wyatt Tee Walker (August 16, 1928 – January 23, 2018) was an African-American pastor, national civil rights leader, theologian, and cultural historian. He was a chief of staff for Martin Luther King Jr., and in 1958 became an early board memb ...

* James Zwerg

* Janet Braun-Reinitz

See also

*" He Was My Brother", a 1964 Simon & Garfunkel song about the Freedom Riders *'' Breach of Peace'', 2008 book * Redlining * Reverse freedom rides *Freedom Ride (Australia)

The Freedom Ride of 1965 was a journey undertaken by a group of Aboriginal Australians in a bus across New South Wales, led by Charles Perkins. Its aim was to bring to the attention of the public the extent of racial discrimination in Australia ...

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * *Further reading

Scholarly works

* * * * * * * * *Autobiographies and memoirs

* * * * * * *Other works

* * *External links

"Freedom Rides: Recollections by David Fankhauser"

~ Civil Rights Movement Archive

''Get On the Bus: The Freedom Riders of 1961''

National Public Radio

NEVER-SEEN: MLK & the Freedom Rides

- slideshow by ''

Life magazine

''Life'' was an American magazine published weekly from 1883 to 1972, as an intermittent "special" until 1978, and as a monthly from 1978 until 2000. During its golden age from 1936 to 1972, ''Life'' was a wide-ranging weekly general-interest ma ...

''''You Don't Have to Ride Jim Crow!''

New Hampshire Public Television/American Public Television documentary of the Journey of Reconciliation

''Eyes on the Prize''

Blackside, Inc./PBS documentary of the Civil Rights Movement (Episode 3 is the Freedom Rides)

"JFK, Freedom Riders, and the Civil Rights Movement"

EDSITEment lesson plan

"The Freedom Riders and the Popular Music of the Civil Rights"

EDSITEment lesson plan

Montgomery County Sheriff's Office, Alabama Department of Archives & History *

''

People's Century

''People's Century'' is a television documentary series examining the 20th century. It was a joint production of the BBC in the United Kingdom and PBS member station WGBH Boston in the United States. The series was first shown on BBC in the 1995 ...

'' television series. PBS

The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) is an American public broadcasting, public broadcaster and Non-commercial activity, non-commercial, Terrestrial television, free-to-air television network based in Arlington, Virginia. PBS is a publicly fu ...

and BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...The Freedom Riders

- slideshow by ''

Life magazine

''Life'' was an American magazine published weekly from 1883 to 1972, as an intermittent "special" until 1978, and as a monthly from 1978 until 2000. During its golden age from 1936 to 1972, ''Life'' was a wide-ranging weekly general-interest ma ...

''FBI files on the Freedom Riders

Online collection of Ride-related articles written by Freedom Riders~ Civil Rights Movement Archive.

Curated links to Freedom Riders archival material

Civil Rights Digital Library.

Civil Rights Activist Bob Zellner interviewed

on ''Conversations from Penn State''

Freedom Riders

historical marker in

Villa Rica, Georgia

Villa Rica (Spanish, Italian, and Portuguese translation: Rich Village) is a city in Carroll and Douglas counties in the U.S. state of Georgia. Located roughly 30 miles west of Atlanta, a decision to develop housing on a large tract of land led ...

CORE's Route 40 Project

campaign for desegregation of Maryland highway, 1961

''Freedom Riders'' interviews by ''American Experience''

at the

American Archive of Public Broadcasting

The American Archive of Public Broadcasting (AAPB) is a collaboration between the Library of Congress and WGBH Educational Foundation, founded through the efforts of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. The AAPB is a national effort to digital ...

{{African American topics

1961 in American politics

1961 protests

African-American history of Alabama

African-American history of Mississippi

African-American history of South Carolina

Bus transportation in the United States

Civil rights movement

Civil rights protests in the United States

Conflicts in 1961

History of African-American civil rights

History of the Southern United States

Nashville Student Movement