Free Church Of Scotland (1843–1900) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Free Church of Scotland is a Scottish denomination which was formed in 1843 by a large withdrawal from the established

The Free Church was formed by

The Free Church was formed by

Led by Dr. Thomas Chalmers (1780–1847), a third of the membership walked out, including nearly all the Gaelic-speakers and the missionaries, and most of the Highlanders. The established Church kept all the properties, buildings and endowments. The seceders created a voluntary fund of over £400,000 to build 700 new churches; 400

Led by Dr. Thomas Chalmers (1780–1847), a third of the membership walked out, including nearly all the Gaelic-speakers and the missionaries, and most of the Highlanders. The established Church kept all the properties, buildings and endowments. The seceders created a voluntary fund of over £400,000 to build 700 new churches; 400

The first task of the new church was to provide income for her initial 500 ministers and places of worship for her people. As she aspired to be the national church of the Scottish people, she set herself the ambitious task of establishing a presence in every parish in Scotland (except in the Highlands, where FC ministers were initially in short supply.) Sometimes land owners were less than helpful such as at Strontian, where the church took to a boat.

The building programme produced 470 new churches within a year and over 700 by 1847.

The first task of the new church was to provide income for her initial 500 ministers and places of worship for her people. As she aspired to be the national church of the Scottish people, she set herself the ambitious task of establishing a presence in every parish in Scotland (except in the Highlands, where FC ministers were initially in short supply.) Sometimes land owners were less than helpful such as at Strontian, where the church took to a boat.

The building programme produced 470 new churches within a year and over 700 by 1847.

The Free Church of Scotland became very active in foreign

The Free Church of Scotland became very active in foreign

From its inception, the Free Church claimed it was the authentic Church of Scotland. Constitutionally, despite the Disruption, she continued to support the establishment principle. However some joined the United Presbyterian Church in calling for the

From its inception, the Free Church claimed it was the authentic Church of Scotland. Constitutionally, despite the Disruption, she continued to support the establishment principle. However some joined the United Presbyterian Church in calling for the

It is noted that duplicates appear in 1866 and 1867.

*

It is noted that duplicates appear in 1866 and 1867.

*

''Annals of the Free Church of Scotland, 1843-1900''

T. & T. Clark, Edinburgh, 1914, with Supplementary Information * Finlayson, Alexander

Unity and diversity: the founders of the Free Church of Scotland

', Fearn, Ross-shire, Great Britain, Christian Focus, 2010. * * Mechie, S. ''The Church and Scottish Social Development, 1780–1870'' (1960) * {{DEFAULTSORT:Free Church of Scotland (1843-1900) Presbyterianism in Scotland Religious organizations established in 1843 1843 establishments in Scotland 1900 disestablishments in Scotland de:Free Church of Scotland sv:Skotska frikyrkan

Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Reformation of 1560, when it split from the Catholic Church ...

in a schism

A schism ( , , or, less commonly, ) is a division between people, usually belonging to an organization, movement, or religious denomination. The word is most frequently applied to a split in what had previously been a single religious body, suc ...

known as the Disruption of 1843

The Disruption of 1843, also known as the Great Disruption, was a schism in 1843 in which 450 evangelical ministers broke away from the Church of Scotland to form the Free Church of Scotland.

The main conflict was over whether the Church of S ...

. In 1900, the vast majority of the Free Church of Scotland joined with the United Presbyterian Church of Scotland to form the United Free Church of Scotland

The United Free Church of Scotland (UF Church; gd, An Eaglais Shaor Aonaichte, sco, The Unitit Free Kirk o Scotland) is a Scottish Presbyterian denomination formed in 1900 by the union of the United Presbyterian Church of Scotland (or UP) and ...

(which itself mostly re-united with the Church of Scotland in 1929). In 1904, the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

judged that the constitutional minority that did not enter the 1900 union were entitled to the whole of the church's patrimony, the Free Church of Scotland acquiesced in the division of those assets, between itself and those who had entered the union, by a Royal Commission in 1905. Despite the late founding date, Free Church of Scotland leadership claims an unbroken succession of leaders going all the way back to the Apostles

An apostle (), in its literal sense, is an emissary, from Ancient Greek ἀπόστολος (''apóstolos''), literally "one who is sent off", from the verb ἀποστέλλειν (''apostéllein''), "to send off". The purpose of such sending ...

.

Origins

The Free Church was formed by

The Free Church was formed by Evangelicals

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide interdenominational movement within Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being " born again", in which an individual expe ...

who broke from the Establishment of the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Reformation of 1560, when it split from the Catholic Church ...

in 1843 in protest against what they regarded as the state's encroachment on the spiritual independence of the Church. Leading up to the Disruption many of the issues were discussed from an evangelical position in Hugh Miller

Hugh Miller (10 October 1802 – 23/24 December 1856) was a self-taught Scottish geologist and writer, folklorist and an evangelical Christian.

Life and work

Miller was born in Cromarty, the first of three children of Harriet Wright (''b ...

's widely circulating newspaper The Witness. Of the driving personalities behind the Disruption Thomas Chalmers

Thomas Chalmers (17 March 178031 May 1847), was a Scottish minister, professor of theology, political economist, and a leader of both the Church of Scotland and of the Free Church of Scotland. He has been called "Scotland's greatest nine ...

was probably the most influential with Robert Candlish

Robert Smith Candlish (23 March 1806 – 19 October 1873) was a Scottish minister who was a leading figure in the Disruption of 1843. He served for many years in both St. George's Church and St George's Free Church on Charlotte Square in Edi ...

perhaps second. Alexander Murray Dunlop

Alexander Colquhoun-Stirling-Murray-Dunlop (27 December 1798 – 1 September 1870) was a Scottish church advocate and Liberal Party politician. He was the Member of Parliament (MP) for Greenock from 1852 to 1868. He was a very influential fi ...

, the church lawyer, was also very involved.

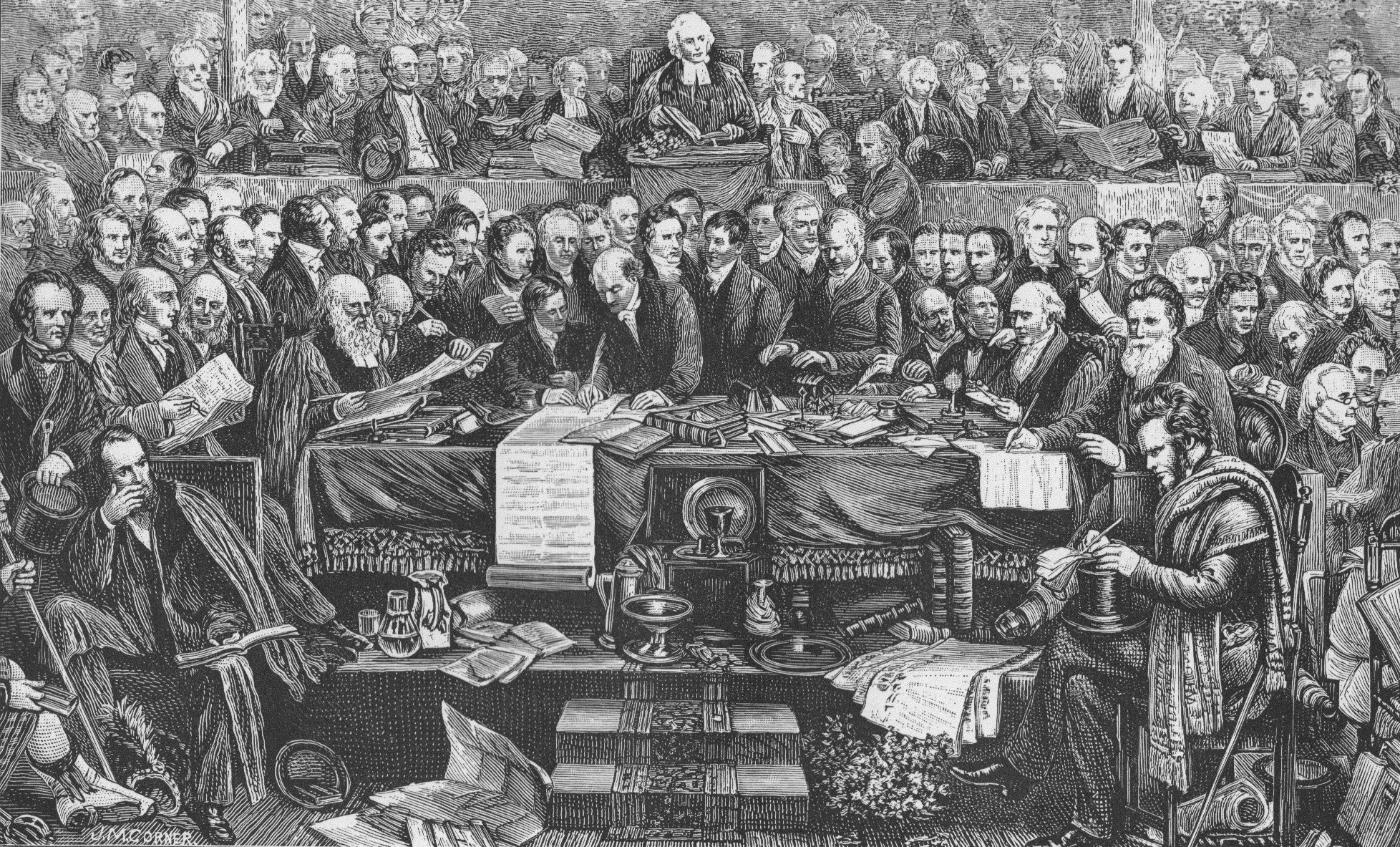

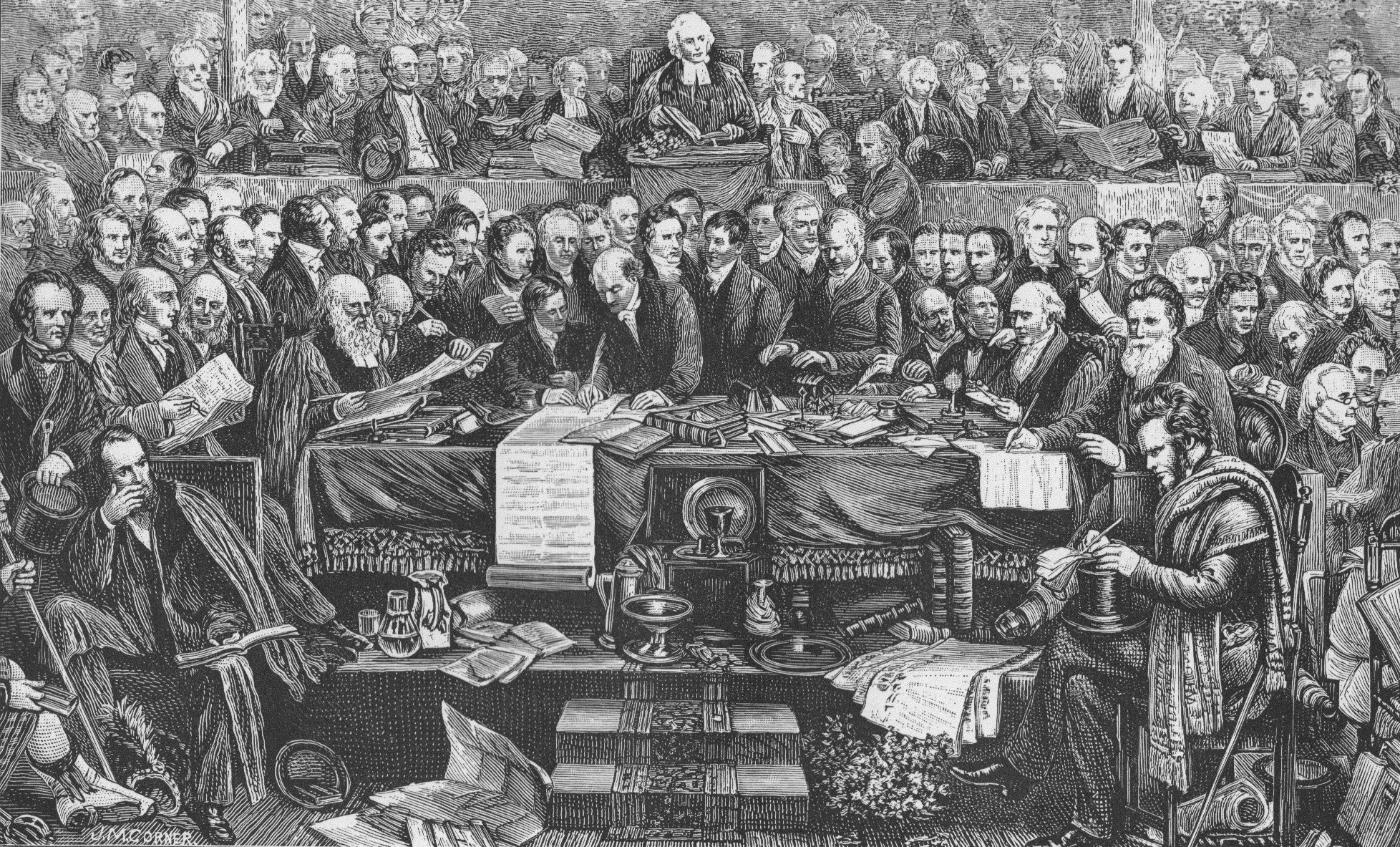

The Disruption of 1843

The Disruption of 1843, also known as the Great Disruption, was a schism in 1843 in which 450 evangelical ministers broke away from the Church of Scotland to form the Free Church of Scotland.

The main conflict was over whether the Church of S ...

was a bitter, nationwide division which split the established Church of Scotland. It was larger than the previous historical secessions of 1733 or 1761. The evangelical element had been demanding the purification of the Church, and it attacked the patronage system

In politics and government, a spoils system (also known as a patronage system) is a practice in which a political party, after winning an election, gives government jobs to its supporters, friends (cronyism), and relatives (nepotism) as a reward ...

, which allowed rich landowners to select the local ministers. It became a political battle between evangelicals on one side and the "Moderates" and gentry on the other. The evangelicals secured passage by the church's General Assembly in 1834, of the "Veto Act", asserting that, as a fundamental law of the Church, no pastor should be forced by the gentry upon a congregation contrary to the popular will, and that any nominee could be rejected by majority of the heads of families. This direct blow at the right of private patrons was challenged in the civil courts, and was decided (1838) against the evangelicals. In 1843, 450 evangelical ministers (out of 1,200 ministers in all) broke away, and formed the Free Church of Scotland.

Led by Dr. Thomas Chalmers (1780–1847), a third of the membership walked out, including nearly all the Gaelic-speakers and the missionaries, and most of the Highlanders. The established Church kept all the properties, buildings and endowments. The seceders created a voluntary fund of over £400,000 to build 700 new churches; 400

Led by Dr. Thomas Chalmers (1780–1847), a third of the membership walked out, including nearly all the Gaelic-speakers and the missionaries, and most of the Highlanders. The established Church kept all the properties, buildings and endowments. The seceders created a voluntary fund of over £400,000 to build 700 new churches; 400 manse

A manse () is a clergy house inhabited by, or formerly inhabited by, a minister, usually used in the context of Presbyterian, Methodist, Baptist and other Christian traditions.

Ultimately derived from the Latin ''mansus'', "dwelling", from ' ...

s (residences for the ministers) were erected at a cost of £250,000; and an equal or larger amount was expended on the building of 500 parochial schools, as well as a college

A college (Latin: ''collegium'') is an educational institution or a constituent part of one. A college may be a degree-awarding tertiary educational institution, a part of a collegiate or federal university, an institution offerin ...

in Edinburgh. After the passing of the Education Act of 1872, most of these schools were voluntarily transferred to the newly established public school-boards.

Chalmers' ideas shaped the breakaway group. He stressed a social vision that revived and preserved Scotland's communal traditions at a time of strain on the social fabric of the country. Chalmers's idealised small equalitarian, kirk-based, self-contained communities that recognised the individuality of their members and the need for co-operation. That vision also affected the mainstream Presbyterian churches, and by the 1870s it had been assimilated by the established Church of Scotland. Chalmers's ideals demonstrated that the church was concerned with the problems of urban society, and they represented a real attempt to overcome the social fragmentation that took place in industrial towns and cities.

Nature

Finances

The first task of the new church was to provide income for her initial 500 ministers and places of worship for her people. As she aspired to be the national church of the Scottish people, she set herself the ambitious task of establishing a presence in every parish in Scotland (except in the Highlands, where FC ministers were initially in short supply.) Sometimes land owners were less than helpful such as at Strontian, where the church took to a boat.

The building programme produced 470 new churches within a year and over 700 by 1847.

The first task of the new church was to provide income for her initial 500 ministers and places of worship for her people. As she aspired to be the national church of the Scottish people, she set herself the ambitious task of establishing a presence in every parish in Scotland (except in the Highlands, where FC ministers were initially in short supply.) Sometimes land owners were less than helpful such as at Strontian, where the church took to a boat.

The building programme produced 470 new churches within a year and over 700 by 1847. Manse

A manse () is a clergy house inhabited by, or formerly inhabited by, a minister, usually used in the context of Presbyterian, Methodist, Baptist and other Christian traditions.

Ultimately derived from the Latin ''mansus'', "dwelling", from ' ...

s and over 700 schools soon followed. This programme was made possible by extraordinary financial generosity, which came from the Evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide interdenominational movement within Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being " born again", in which an individual expe ...

awakening and the wealth of the emerging middle class.

The church created a Sustentation Fund, the brainchild of Thomas Chalmers

Thomas Chalmers (17 March 178031 May 1847), was a Scottish minister, professor of theology, political economist, and a leader of both the Church of Scotland and of the Free Church of Scotland. He has been called "Scotland's greatest nine ...

, to which congregations contributed according to their means, and from which all ministers received an 'equal dividend'. This fund provided a modest income for 583 ministers in 1843/4, and by 1900 was able to provide an income for nearly 1200. This centralising and sharing of resources was previously unknown within the Protestant churches in Scotland, but later became the norm.

"Send back the money" campaign

In their original fundraising activities the Free Church sent "missionaries" to theUnited States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

, where they found some slave-owners particularly supportive. However, the church having accepted £3,000 in donations from this source, they were later denounced as unchristian by some abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

. Some Free Churchmen like George Buchan, William Collins, John Wilson and Henry Duncan themselves campaigned for the ultimate abolition of slavery. When Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

arrived in Scotland he became a vocal proponent of the "Send back the money" campaign which urged the Free Church to return the £3,000 donation. In his autobiography "My Bondage and My Freedom" Douglass (p. 386) writes: "The Free Church held on to the blood-stained money, and continued to justify itself in its position — and of course to apologize for slavery — and does so till this day. She lost a glorious opportunity for giving her voice, her vote, and her example to the cause of humanity ; and to-day she is staggering under the curse of the enslaved, whose blood is in her skirts." Douglass spoke at three meetings in Dundee in 1846. In 1844, long before Douglass's arrival, Robert Candlish

Robert Smith Candlish (23 March 1806 – 19 October 1873) was a Scottish minister who was a leading figure in the Disruption of 1843. He served for many years in both St. George's Church and St George's Free Church on Charlotte Square in Edi ...

had spoken against slavery in a debate about a man named John Brown. In 1847 he is quoted as saying, from the floor of the Free Church Assembly: "Never, never, let this church, or this country, cease to testify that slavery is sin, and that it must bring down on the sinners, whether they be in Congress assembled, or as individuals throughout the land, the just judgement of Almighty God."Not all American Presbyterians shared his anti-slavery view, although some did both in the north and the south. Presbyterian thinker

B. B. Warfield

Benjamin Breckinridge Warfield (November 5, 1851 – February 16, 1921) was professor of theology at Princeton Seminary from 1887 to 1921. He served as the last principal of the Princeton Theological Seminary from 1886 to 1902. After the death o ...

regarded the integration of freed slaves as one of the largest problems America had ever faced. An official letter from the Free Church did reach the Assembly of the Southern Presbyterian Church in May 1847. The official Free Church position was described as being "very strongly against slavery".

Theology

Great importance was attached to maintaining an educated ministry within the Free Church. Because the established Church of Scotland controlled the divinity faculties of the universities, the Free Church set up its own colleges. New College was opened in 1850 with five chairs: Systematic Theology, Apologetics and Practical Theology, Church History, Hebrew and Old Testament, and New Testament Exegesis. The Free Church also set up Christ's College in Aberdeen in 1856 andTrinity College Trinity College may refer to:

Australia

* Trinity Anglican College, an Anglican coeducational primary and secondary school in , New South Wales

* Trinity Catholic College, Auburn, a coeducational school in the inner-western suburbs of Sydney, New ...

in Glagow followed later. The first generation of teachers were enthusiastic proponents of Westminster Calvinism.

For example, David Welsh

David Welsh FRSE (11 December 179324 April 1845) was a Scottish divine and academic. He was Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in 1842. In the Disruption of 1843 he was one of the leading figures in the establishmen ...

was an early professor. James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was an American lawyer, diplomat and politician who served as the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861. He previously served as secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and repr ...

followed Thomas Chalmers as professor of Systematic Theology when he died in 1847. James Bannerman was appointed to the chair of Apologetics and Pastoral Theology and his ''The Church of Christ'' volumes 1 and 2 were widely read. William Cunningham was one of the early Church History professors. John "Rabbi" Duncan was an early professor of Hebrew. Other chairs were added such as the Missionary Chair of Duff.

This position was subsequently abandoned, as theologians such as A. B. Bruce, Marcus Dods and George Adam Smith

:''Note in particular that this George Smith is to be distinguished from George Smith (Assyriologist) (1840–1876) who researched in some overlapping areas.''

Sir George Adam Smith (19 October 1856 – 3 March 1942) was a Scottish the ...

began to teach a more liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

understanding of the faith. 'Believing criticism' of the Bible was a central approach taught by such as William Robertson Smith

William Robertson Smith (8 November 184631 March 1894) was a Scottish orientalist, Old Testament scholar, professor of divinity, and minister of the Free Church of Scotland. He was an editor of the ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' and contributo ...

and he was dismissed from his chair by the Assembly in 1881. Attempts were made between 1890 and 1895 to bring many of these professors to the bar of the Assembly on charges of heresy, but these moves failed, with only minor warnings being issued.

In 1892 the Free Church, following the example of the United Presbyterian Church and the Church of Scotland, and with union with those denominations as the goal, passed a Declaratory Act relaxing the standard of subscription to the confession. This had the result that a small number of congregations and even fewer ministers, mostly in the Highlands, severed their connection with the church and formed the Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland

The Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland ( gd, An Eaglais Shaor Chlèireach, ) was formed in 1893. The Church identifies itself as the spiritual descendant of the Scottish Reformation. The Church web-site states that it is 'the constitutional hei ...

. Others with similar theological views waited for imminent union but chose to continue with the Free Church.

Activity

The Free Church of Scotland became very active in foreign

The Free Church of Scotland became very active in foreign mission

Mission (from Latin ''missio'' "the act of sending out") may refer to:

Organised activities Religion

*Christian mission, an organized effort to spread Christianity

*Mission (LDS Church), an administrative area of The Church of Jesus Christ of ...

s. Many of the staff from the established Church of Scotland's India mission adhered to the Free Church. The church soon also established herself in Africa, with missionaries such as James Stewart

James Maitland Stewart (May 20, 1908 – July 2, 1997) was an American actor and military pilot. Known for his distinctive drawl and everyman screen persona, Stewart's film career spanned 80 films from 1935 to 1991. With the strong morality h ...

(1831-1905) and with the co-operation of Robert Laws (1851-1934) of the United Presbyterian Church, as well as becoming involved in evangelisation of the Jews. Her focus on mission resulted in one of the largest missionary organisations in the world. Preachers like William Chalmers Burns

William Chalmers Burns (宾惠廉, 1 April 1815 – 4 April 1868) was a Scottish Evangelist and Missionary to China with the English Presbyterian Mission who originated from Kilsyth, North Lanarkshire. He was the coordinator of the Overseas ...

worked in Canada and China. Alexander Duff and John Anderson John Anderson may refer to:

Business

*John Anderson (Scottish businessman) (1747–1820), Scottish merchant and founder of Fermoy, Ireland

* John Byers Anderson (1817–1897), American educator, military officer and railroad executive, mentor of ...

worked in India. Duff can be seen behind Hugh Miller in the Disruption Painting signing Missions in Bengal. There were missions related to the Free Church and visited by Duff at Lake Nyassa in Africa and in the Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus li ...

.

The early Free Church was also concerned with educational reform including setting up Free Church schools. Members of the Free Church also became associated with the colonisation of New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

: the Free Church offshoot the Otago Association

The Otago Association was founded in 1845 by adherents of the Free Church of Scotland with the purpose of establishing a colony of like-minded Scots in Otago in the South Island of New Zealand, chiefly at Dunedin.

In addition to religion, the ec ...

sent out emigrants in 1847 who established the Otago

Otago (, ; mi, Ōtākou ) is a region of New Zealand located in the southern half of the South Island administered by the Otago Regional Council. It has an area of approximately , making it the country's second largest local government reg ...

settlement in 1848. Thomas Burns was one of the first churchmen in the colony which developed into Dunedin

Dunedin ( ; mi, Ōtepoti) is the second-largest city in the South Island of New Zealand (after Christchurch), and the principal city of the Otago region. Its name comes from , the Scottish Gaelic name for Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland. Th ...

.

The importance of Home Missions also grew, these having the purpose of increasing church attendance, particularly amongst the poorer communities in large cities. Thomas Chalmers

Thomas Chalmers (17 March 178031 May 1847), was a Scottish minister, professor of theology, political economist, and a leader of both the Church of Scotland and of the Free Church of Scotland. He has been called "Scotland's greatest nine ...

led the way with a territorial mission in Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

's West Port (1844- ), which epitomised his idea of a "godly commonwealth". Free churchmen were at the forefront of the 1859 Revival as well as of the Moody and Sankey's campaign of 1873–1875 in Britain. However, Chalmers's social ideas were never fully realised, as the gap between the church and the urban masses continued to increase.

Towards the end of the 19th century, Free Churches sanctioned the use of instrumental music. An association formed in 1891 to promote order and reverence in public services. In 1898 it published ''A New Directory for Public Worship'' which, while not providing set forms of prayer, offered directions. The Free Church took an interest in hymnology

Hymnology (from Greek ὕμνος ''hymnos'', "song of praise" and -λογία ''-logia'', "study of") is the scholarly study of religious song, or the hymn, in its many aspects, with particular focus on choral and congregational song. It may be m ...

and church music, which led to the production of its hymnbook.

Unions and relationships with other Presbyterians

Disestablishment

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the state. Conceptually, the term refers to the creation of a secular stat ...

of the Church of Scotland.

In 1852 the Original Secession Church joined the Free Church; in 1876 most of the Reformed Presbyterian Church followed suit. However, a leadership-led attempt to unite with the United Presbyterians was not successful. These attempts began as early as 1863 when the Free Church began talks with the UPC with a view to a union. However, a report laid before the Assembly of 1864 showed that the two churches were not agreed as to the relationship between state and church. The Free Church maintained that national resources could be used in aid of the church, provided that the state abstain from all interference in its internal government. The United Presbyterians held that, as the state had no authority in spiritual things, it was not within its jurisdiction to legislate as to what was true in religion, prescribe a creed or any form of worship for its subjects, or to endow the church from national resources. Any union would therefore have to leave this question open. At the time this difference was sufficient to preclude the union being pursued.

In the following years the Free Church Assembly showed increasing willingness for union on these open terms. However, the 'establishment' minority prevented a successful conclusion during the years between 1867–73. After negotiations failed in 1873, the two churches agreed a 'Mutual Eligibility Act' enabling a congregation of one denomination to call a minister from the other.

During this period the antidisestablishmentarian

Antidisestablishmentarianism (, ) is a position that advocates that a state Church (the "established church") should continue to receive government patronage, rather than be disestablished.

In 19th century Britain, it developed as a politica ...

party continued to shrink and became increasingly alienated. This decline was hastened when some congregations left to form the Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland

The Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland ( gd, An Eaglais Shaor Chlèireach, ) was formed in 1893. The Church identifies itself as the spiritual descendant of the Scottish Reformation. The Church web-site states that it is 'the constitutional hei ...

in 1893.

Starting in 1895, union began to be officially discussed once more. A joint committee made up of men from both denominations noted remarkable agreement on doctrinal standards, rules and methods. After a few concessions from both sides, a common constitution was agreed. However, a minority in the Free Church Assembly protested, and threatened to test its legality in the courts.

The respective assemblies of the churches met for the last time on 30 October 1900. On the following day the union was completed, and the United Free Church of Scotland

The United Free Church of Scotland (UF Church; gd, An Eaglais Shaor Aonaichte, sco, The Unitit Free Kirk o Scotland) is a Scottish Presbyterian denomination formed in 1900 by the union of the United Presbyterian Church of Scotland (or UP) and ...

came into being.

However, a minority of those who dissented remained outside the union, claiming that they were the true Free Church and that the majority had departed from the church when they formed the United Free Church. After a protracted legal battle, the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

found in favour of the minority (in spite of the belief of most that the true kirk is above the state) and awarded them the right to keep the name Free Church of Scotland, though the majority was able to keep most of the financial resources. (See Free Church of Scotland for the history of the continuing body.)

Moderators of the General Assembly

It is noted that duplicates appear in 1866 and 1867.

*

It is noted that duplicates appear in 1866 and 1867.

*Thomas Chalmers

Thomas Chalmers (17 March 178031 May 1847), was a Scottish minister, professor of theology, political economist, and a leader of both the Church of Scotland and of the Free Church of Scotland. He has been called "Scotland's greatest nine ...

(May 1843)

* Thomas Brown (October 1843)

* Henry Grey (1844)

*Patrick MacFarlan

Patrick MacFarlan (4 April 1781 – 13 November 1849) was a Scottish minister who served as Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in 1834 and as Moderator of the General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland in 1845. ...

(1845) Gaelic Moderator John Macdonald

* Robert James Brown (1846)

* James Sievewright (1847)

*Patrick Clason

Patrick Clason (13 October 1789 – 30 July 1867) was a Scottish minister who served as Moderator of the General Assembly to the Free Church of Scotland in 1848/49.

Life

He was born on 13 October 1789 in the manse at Dalziel near the Riv ...

(1848)

*Mackintosh MacKay

Mackintosh MacKay (1793 – 1873) was a Scottish minister and author who served as Moderator of the General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland in 1849. He edited the Highland Society's prodigious Gaelic dictionary ('Dictionarium Scoto-Celt ...

(1849)

*Nathaniel Paterson

Nathaniel Paterson (1787–25 April 1871) was a Scottish minister who served as Moderator of the General Assembly to the Free Church of Scotland in 1850/51. He was a close friend of Walter Scott and was included in his circle of "worthies".

...

(1850)

* Alexander Duff (1851)

*Angus Makellar

Angus Makellar (1780–1859) was a Scottish minister of the Church of Scotland who served as Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in 1840. Leaving in the Disruption of 1843 he also served as Moderator of the General Asse ...

(1852)

* John Smyth (1853)

* James Grierson (1854)

* James Henderson (1855)

*Thomas M'Crie the Younger

Thomas M'Crie (earlier spellings include McCree and Maccrie) (7 November 1797–9 May 1875) was a Presbyterian minister and church historian. He was a Scottish Secession minister who joined the Free Church of Scotland and served as the M ...

(1856)

*James Julius Wood

James Julius Wood (1800–1877) was a 19th-century Scottish minister who served as Moderator of the General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland 1857/8.

Life

He was born in Jedburgh on 4 September 1800 the son of Dr William Wood MD and ...

(1857)

*Alexander Beith

Alexander Beith (1799–1891) was a Scottish divine and author who served as Moderator of the General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland 1858/59.

Early life and education

He was born at Campbeltown, Argyllshire, on 13 January 1799. ...

(1858)

* William Cunningham (1859)

* Robert Buchanan (1860)

*Robert Smith Candlish

Robert Smith Candlish (23 March 1806 – 19 October 1873) was a Scottish minister who was a leading figure in the Disruption of 1843. He served for many years in both St. George's Church and St George's Free Church on Charlotte Square in Edin ...

(1861)

*Thomas Guthrie

Thomas Guthrie FRSE (12 July 1803 – 24 February 1873) was a Scottish divine and philanthropist, born at Brechin in Angus (at that time also called Forfarshire). He was one of the most popular preachers of his day in Scotland, and was associat ...

(1862)

* Roderick McLeod (1863)

*Patrick Fairbairn

Patrick Fairbairn (28 January 1805 – 6 August 1874) was a Scottish Free Church minister and theologian. He was Moderator of the General Assembly 1864/65.

Early life and career

He was born in Halyburton, Greenlaw, Berwickshire, on 28 Ja ...

(1864)

*James Begg

James Begg (31 October 1808 in New Monkland, Lanarkshire, Scotland – 29 September 1883) was a minister of the Free Church of Scotland who served as Moderator of the General Assembly 1865/66.

Life

He was born in the manse at New Monkla ...

(1865)

* William Wilson (1866)

* John Roxburgh (1866 or 1867)

*Robert Smith Candlish

Robert Smith Candlish (23 March 1806 – 19 October 1873) was a Scottish minister who was a leading figure in the Disruption of 1843. He served for many years in both St. George's Church and St George's Free Church on Charlotte Square in Edin ...

(1867)

* William Nixon (1868)

* Henry Wellwood Moncreiff (1869)

* John Wilson (1870)

* Robert Elder (1871)

*Charles John Brown

Charles John Brown (born 13 October 1959) is an American prelate of the Roman Catholic Church who has been serving as an apostolic nuncio since 2012. He is currently the apostolic nuncio to the Philippines. Before entering the diplomatic se ...

(1872)

* Alexander Duff (1873) the only person to serve a second term

*Robert Walter Stewart

Robert Walter Stewart (1812–1887) was a Scottish minister of the Free Church of Scotland and who spent much time working in Italy and served as Moderator of the General Assembly 1874/75. He helped to promote the Waldensian Church and the P ...

(1874)

* Alexander Moody Stuart (1875)

* Thomas McLauchlan (1876)

*William Henry Goold

William Henry Goold (15 December 1815 – 29 June 1897) was a Scottish minister of both the Reformed Presbyterian Church of Scotland, Reformed Presbyterian Church and the Free Church of Scotland (1843–1900), Free Church of Scotland. He wa ...

(1877)

*Andrew Bonar

Andrew Alexander Bonar (29 May 1810 in Edinburgh – 30 December 1892 in Glasgow) was a minister of the Free Church of Scotland (1843-1900), Free Church of Scotland, a contemporary and acquaintance of Robert Murray M'Cheyne and youngest brother ...

(1878)

*James Chalmers Burns

James Chalmers Burns (29 March 1809–30 November 1892) was a Scottish minister, who served as Moderator of the General Assembly for the Free Church of Scotland 1879/80.

Early life and education

He was born on 29 March 1809 in the manse at ...

(1879)

*Thomas Main

Thomas Forrest Main (1911–1990) was a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst who coined the term ' therapeutic community'. He is particularly remembered for his often cited paper, ''The Ailment'' (1957).

Life

Thomas Main was born on 25 February 191 ...

(1880)

*William Laughton

William Laughton (1812–7 November 1897) was a Scottish minister of the Free Church of Scotland who served as Moderator of the General Assembly to the Free Church 1881/82.

Life

Laughton was born in London in 1812, the eldest son of Captain W ...

(1881)

* Robert MacDonald (minister) (1882)

*Horatius Bonar

Horatius Bonar (19 December 180831 July 1889), a contemporary and acquaintance of Robert Murray M'cheyne was a Scotland, Scottish churchman and poet. He is principally remembered as a prodigious hymnodist. Friends knew him as Horace Bona ...

(1883)

* Walter Ross Taylor (1884)

* David Brown (1885)

* Alexander Neil Somerville (1886)

*Robert Rainy

Robert Rainy (1 January 1826 – 22 December 1906), was a Scottish Presbyterian divine. Rainy Hall in New College, Edinburgh (the Divinity faculty in Edinburgh University) is named after him.

Life

He was born on New Year's Day 1826 at 28 M ...

(1887)

* Gustavus Aird (1888) (the only year the Assembly was solely in Inverness)

* John Laird (1889)

* Thomas Brown (1890)

* Thomas Smith (1891)

*William Garden Blaikie

William Garden Blaikie FRSE (5 February 1820, in Aberdeen – 11 June 1899) was a Scottish minister, writer, biographer, and temperance reformer.

Life

His father James Ogilvie Blaikie was the first Provost of Aberdeen following its reformed ...

(1892)

*Walter Chalmers Smith

Walter Chalmers Smith (5 December 1824 – 19 September 1908), was a hymnist, author, poet and minister of the Free Church of Scotland, chiefly remembered for his hymn "Immortal, Invisible, God Only Wise". In 1893 he served as Moderator of the ...

(1893)

* George Douglas (1894)

* James Hood Wilson (1895)

* William Miller (1896)

* Hugh Macmillan (1897)

*Alexander Whyte

''For the British colonial administrator, see Alexander Frederick Whyte''

Rev Alexander Whyte D.D.,LL.D. (13 January 18366 January 1921) was a Scottish divine. He was Moderator of the General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland in 1898.

...

(1898)

*James Stewart

James Maitland Stewart (May 20, 1908 – July 2, 1997) was an American actor and military pilot. Known for his distinctive drawl and everyman screen persona, Stewart's film career spanned 80 films from 1935 to 1991. With the strong morality h ...

(1899)

* Walter Ross Taylor (1900)

Gaelic Moderators

For certain years a separate Gaelic Moderator served at a separate Assembly inInverness

Inverness (; from the gd, Inbhir Nis , meaning "Mouth of the River Ness"; sco, Innerness) is a city in the Scottish Highlands. It is the administrative centre for The Highland Council and is regarded as the capital of the Highlands. Histori ...

. This had advantages of allowing northern ministers to travel less to the Assembly. It did however create a division. In this division it was largely the northern ministers who remained in the Free Church following the Union of 1900. Known Gaelic Moderators are:Ewing, William ''Annals of the Free Church''

* Rev John MacDonald (1845)

* Gustavus Aird (1888)

Other areas

The Free Church were spread the length and breadth of Scotland and also had churches in the northmost sectors of England and several churches inLondon

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

. Their influence in other countries focused on Canada and New Zealand, where there were a high proportion of Scots. They ran a specific recruitment campaign to get Free Church ministers to go to New Zealand. Moderators in New Zealand included:

* Gordon Webster (1898)

Prince Edward Island, Canada, retains a number of Free Churches of Scotland affiliated with the Synod in Scotland as missionary churches. This alliance was established by the Moderator of the Free Church of Scotland, Rev. Ewen MacDougall, in the 1930s, at the time of the establishment of the Presbyterian Church in Canada and the subsequent establishment of the United Church of Canada. The large enclave of Free Church of Scotland congregations has been attributed to a religious revival under the preaching of Rev. Donald MacDonald. The extant Church of Scotland congregations of Prince Edward Island, Canada, continue to adhere to a simple form of worship with a focus on a biblical exegesis from the pulpit, singing of the Psalms and biblical paraphrases without accompaniment or choir, led by a chanter, and prayer. The houses of worship remain simple with minimal embellishment.

See also

*Religion in the United Kingdom

Religion in the United Kingdom, and in the countries that preceded it, has been dominated for over 1,000 years by various forms of Christianity, replacing Romano-British religions, Celtic and Anglo-Saxon paganism as the primary religion. Rel ...

References

Notes

Bibliography

* Brown, Stewart J. ''Thomas Chalmers and the Godly Commonwealth in Scotland'' (1982) * Cameron, N. ''et al.'' (eds) ''Dictionary of Scottish Church History and Theology'', Edinburgh T&T Clark 1993 * Devine, T. M. ''The Scottish Nation'' (1999) ch 16 * Drummond, Andrew Landale, and James Bulloch. ''The Church in Victorian Scotland, 1843–1874'' (Saint Andrew Press, 1975) * Ewing, William''Annals of the Free Church of Scotland, 1843-1900''

T. & T. Clark, Edinburgh, 1914, with Supplementary Information * Finlayson, Alexander

Unity and diversity: the founders of the Free Church of Scotland

', Fearn, Ross-shire, Great Britain, Christian Focus, 2010. * * Mechie, S. ''The Church and Scottish Social Development, 1780–1870'' (1960) * {{DEFAULTSORT:Free Church of Scotland (1843-1900) Presbyterianism in Scotland Religious organizations established in 1843 1843 establishments in Scotland 1900 disestablishments in Scotland de:Free Church of Scotland sv:Skotska frikyrkan