Frank S. Black on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

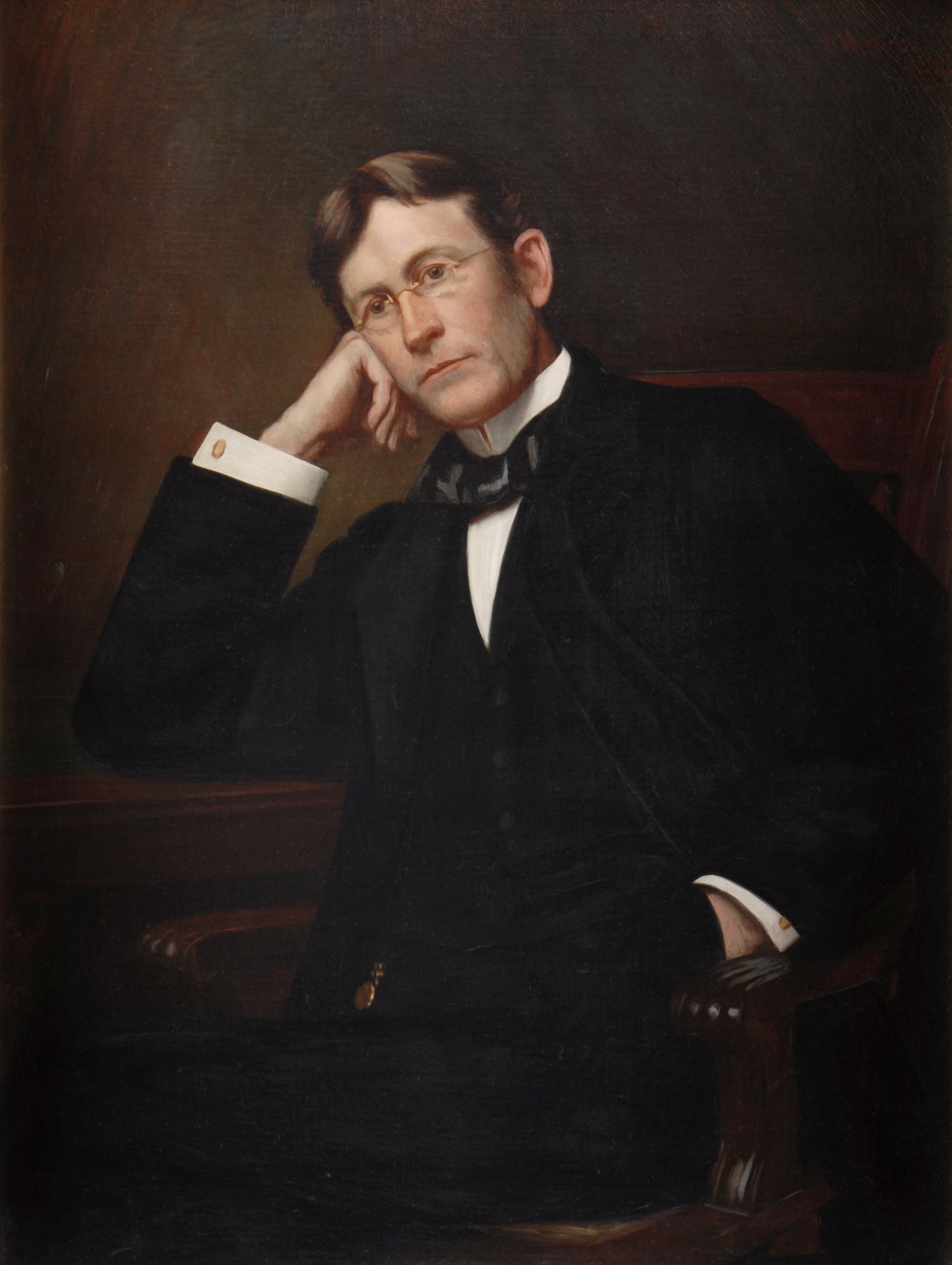

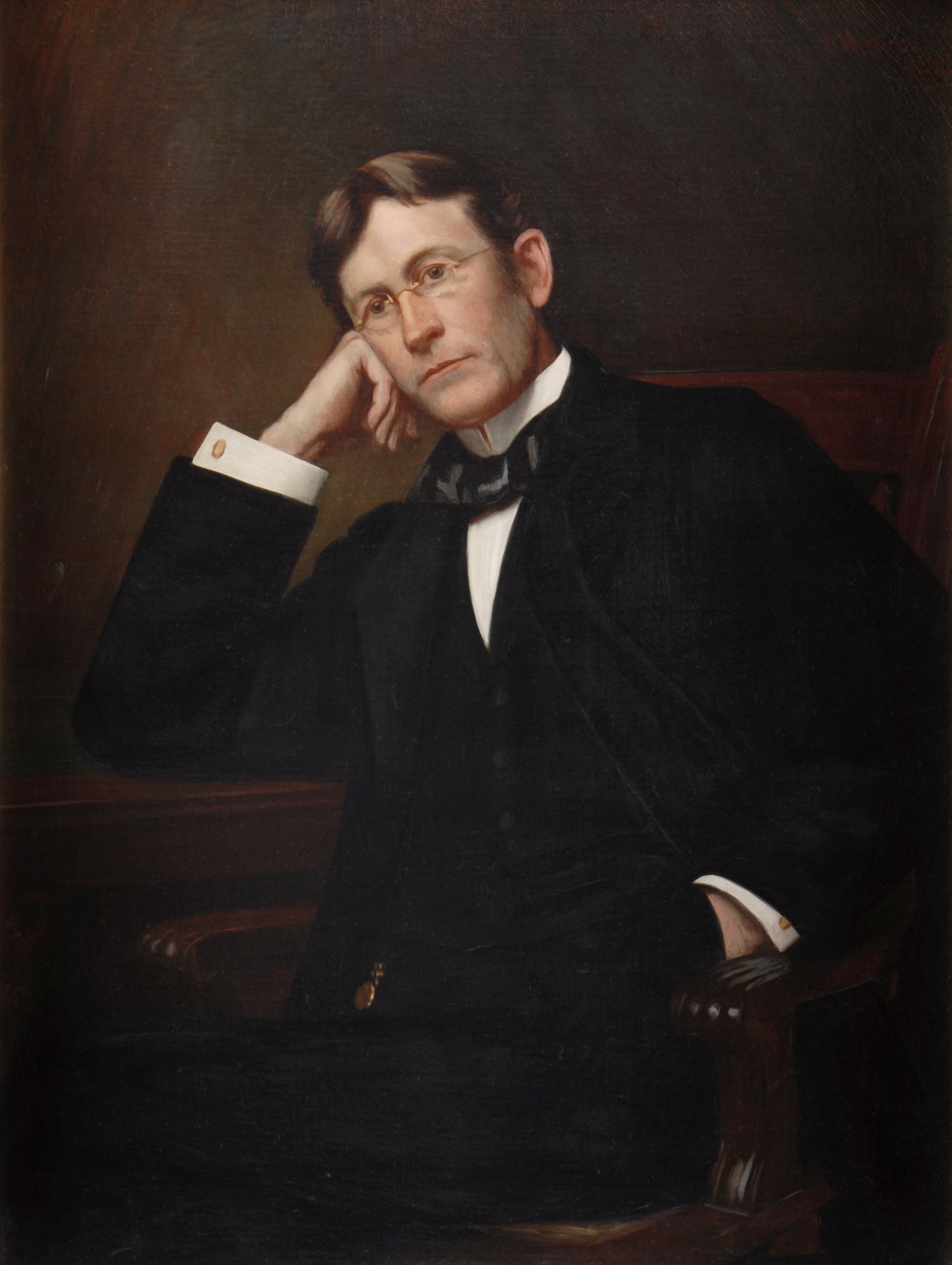

Frank Swett Black (March 8, 1853March 22, 1913) was an American newspaper editor, lawyer and politician. A

After leaving office, Black resumed his law practice. Among the noteworthy cases in which he was involved, Black took part in the defense of Roland B. Molineaux in the famed '' People v. Molineux'' case. After Molineaux was convicted of murder, the conviction was overturned and he won an acquittal at retrial. The case was the source of the well-known " Molineux rule" which limits the ability of prosecutors to use prior crimes as proof that a defendant committed the crime with which he is charged. Black also took part in the defense of Caleb Powers for the assassination of Kentucky governor

After leaving office, Black resumed his law practice. Among the noteworthy cases in which he was involved, Black took part in the defense of Roland B. Molineaux in the famed '' People v. Molineux'' case. After Molineaux was convicted of murder, the conviction was overturned and he won an acquittal at retrial. The case was the source of the well-known " Molineux rule" which limits the ability of prosecutors to use prior crimes as proof that a defendant committed the crime with which he is charged. Black also took part in the defense of Caleb Powers for the assassination of Kentucky governor

Biography, Frank Swett Black

at National Governors Association

Frank S. Black

at New York State Hall of Governors

Today in Masonic History: Frank Swett Black is Born

at MasonryToday.com {{DEFAULTSORT:Black, Frank Swett 1853 births 1913 deaths People from Limington, Maine Politicians from Troy, New York Dartmouth College alumni New York (state) lawyers Journalists from New York (state) 19th-century American politicians Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives from New York (state) Republican Party governors of New York (state) 19th-century American newspaper editors Burials in New Hampshire 19th-century American lawyers

Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

, he was a member of the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the Lower house, lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the United States Senate, Senate being ...

from 1895 to 1897, and the 32nd Governor of New York from 1897 to 1898.

A native of Limington, Maine

Limington is a town in York County, Maine, United States. The population was 3,892 at the 2020 census. Limington is a tourist destination with historic architecture. It is part of the Portland– South Portland–Biddeford, Maine metropo ...

, Black graduated from Dartmouth College

Dartmouth College (; ) is a private research university in Hanover, New Hampshire. Established in 1769 by Eleazar Wheelock, it is one of the nine colonial colleges chartered before the American Revolution. Although founded to educate Native A ...

in 1875 and moved to New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, where he edited and reported for newspapers in Johnstown and Troy

Troy ( el, Τροία and Latin: Troia, Hittite language, Hittite: 𒋫𒊒𒄿𒊭 ''Truwiša'') or Ilion ( el, Ίλιον and Latin: Ilium, Hittite language, Hittite: 𒃾𒇻𒊭 ''Wiluša'') was an ancient city located at Hisarlik in prese ...

. He studied law, attained admission to the bar in 1879, and practiced in Troy.

Black became involved in politics by giving speeches for Republican candidates and serving as chairman of the party in Rensselaer County

Rensselaer County is a county in the U.S. state of New York. As of the 2020 census, the population was 161,130. Its county seat is Troy. The county is named in honor of the family of Kiliaen van Rensselaer, the original Dutch owner of the la ...

. In 1894, he was a successful candidate for the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the Lower house, lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the United States Senate, Senate being ...

, and he served a partial term, March 1895 to January 1897. Black resigned before the end of his term because he had been elected governor.

In 1896, Black was the successful Republican nominee for governor. He served one term, January 1897 to December 1898. He was an unsuccessful candidate for renomination in 1898, losing at the party's state convention to Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

, who went on to win the general election.

After leaving office, Black resumed the practice of law and remained active in politics as a campaign speaker for Republican candidates. He died in Troy on March 22, 1913 and was buried at his summer home, a farm in Freedom, New Hampshire

Freedom is a town located in Carroll County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 1,689 at the 2020 census, up from 1,489 at the 2010 census. The town's eastern boundary runs along the Maine state border. Ossipee Lake, with a resort ...

.

Early life

Black was born nearLimington, Maine

Limington is a town in York County, Maine, United States. The population was 3,892 at the 2020 census. Limington is a tourist destination with historic architecture. It is part of the Portland– South Portland–Biddeford, Maine metropo ...

on March 8, 1853, one of eleven children born to farmer Jacob Black and Charlotte (Butters) Black. His father moved the family to Alfred, Maine

Alfred is a town in York County, Maine, United States. As of the 2020 census, the town population was 3,073. Alfred is the seat of York County and home to part of the Massabesic Experimental Forest. National Register of Historic Places has two l ...

after accepting an appointment as keeper of the York County jail. Black graduated from Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus li ...

Academy in 1871, then taught school while attending Dartmouth College

Dartmouth College (; ) is a private research university in Hanover, New Hampshire. Established in 1769 by Eleazar Wheelock, it is one of the nine colonial colleges chartered before the American Revolution. Although founded to educate Native A ...

. He graduated with a Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four years ...

degree in 1875, was an editor of all three of the school's student publications, and won prizes for oratory. While in college, Black joined the Delta Kappa Epsilon

Delta Kappa Epsilon (), commonly known as ''DKE'' or ''Deke'', is one of the oldest fraternities in the United States, with fifty-six active chapters and five active colonies across North America. It was founded at Yale College in 1844 by fifteen ...

fraternity.

Start of career

After completing his education, Black movedRome, New York

Rome is a city in Oneida County, New York, United States, located in the Central New York, central part of the state. The population was 32,127 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Rome is one of two principal cities in the Utica–Ro ...

, where he sold chromolithographs

Chromolithography is a method for making multi-colour printmaking, prints. This type of colour printing stemmed from the process of lithography, and includes all types of lithography that are printed in colour. When chromolithography is used to ...

. He soon moved to Johnstown, New York

Johnstown is a city in and the county seat of Fulton County in the U.S. state of New York. The city was named after its founder, Sir William Johnson, Superintendent of Indian Affairs in the Province of New York and a major general during the Seve ...

to become editor of the ''Johnstown Journal'', the publisher of which was a member of the Stalwart faction of Republicans who were loyal to Roscoe Conkling

Roscoe Conkling (October 30, 1829April 18, 1888) was an American lawyer and Republican Party (United States), Republican politician who represented New York (state), New York in the United States House of Representatives and the United States Se ...

. A member of the Half-Breed

Half-breed is a term, now considered offensive, used to describe anyone who is of mixed race; although, in the United States, it usually refers to people who are half Native American and half European/white.

Use by governments United States

In ...

faction of the Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

*Republican Party (Liberia)

* Republican Part ...

and follower of James G. Blaine

James Gillespie Blaine (January 31, 1830January 27, 1893) was an American statesman and Republican politician who represented Maine in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1863 to 1876, serving as Speaker of the U.S. House of Representative ...

, Black changed the political stance of the paper while its publisher was out of town, for which he was promptly fired. He then moved to Troy, New York

Troy is a city in the U.S. state of New York and the county seat of Rensselaer County. The city is located on the western edge of Rensselaer County and on the eastern bank of the Hudson River. Troy has close ties to the nearby cities of Albany a ...

, where he worked for the ''Troy Whig'' and ''Troy Times''. While working as a night reporter, clerk in the Troy post office, and process server

Service of process is the procedure by which a party to a lawsuit gives an appropriate notice of initial legal action to another party (such as a defendant), court, or administrative body in an effort to exercise jurisdiction over that person s ...

, he studied law at the firm of Robertson & Foster. Black attained admission to the bar

An admission to practice law is acquired when a lawyer receives a license to practice law. In jurisdictions with two types of lawyer, as with barristers and solicitors, barristers must gain admission to the bar whereas for solicitors there are dist ...

in 1879 and began to practice in Troy.

In 1888, Black campaigned for Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 23rd president of the United States from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the Harrison family of Virginia–a grandson of the ninth pr ...

for president. In 1892, he campaigned for Harrison's reelection, but Harrison was defeated by former President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

. His continued political activities included serving as chairman of the Republican Party in Rensselaer County

Rensselaer County is a county in the U.S. state of New York. As of the 2020 census, the population was 161,130. Its county seat is Troy. The county is named in honor of the family of Kiliaen van Rensselaer, the original Dutch owner of the la ...

. In March 1894, an election day dispute between Republicans and Democrats in Troy culminated with the murder of Robert Ross, a Republican. Black assisted in the prosecution of the defendants, Democrats Bartholomew "Bat" Shea and John McGough, who were convicted. McGough was sentenced to 20 years in prison, and Shea was executed.

U.S. House

Largely as the result of publicity from the Ross murder case, in November 1894, Black was elected to the54th United States Congress

The 54th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1895, ...

, representing New York's 19th congressional district

New York's 19th congressional district is located in New York's Catskills and mid-Hudson Valley regions. It lies partially in the northernmost region of the New York metropolitan area and mostly south of Albany. This district is currently rep ...

. He served from March 4, 1895 to January 7, 1897, when he resigned because he had been elected governor. During his House term, Black was a member of the Committee on Pacific Railroads and the Committee on Private Land Claims. He was a delegate to the 1896 Republican National Convention

The 1896 Republican National Convention was held in a temporary structure south of the St. Louis City Hall in Saint Louis, Missouri, from June 16 to June 18, 1896.

Former Governor William McKinley of Ohio was nominated for president on the firs ...

and supported William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in ...

for president.

Governor

Black was elected governor in 1896 and served from January 1, 1897 to December 31, 1898. A highlight of his governorship was completion of construction on theNew York State Capitol

The New York State Capitol, the seat of the Government of New York State, New York state government, is located in Albany, New York, Albany, the List of U.S. state capitals, capital city of the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. The seat o ...

, which had fallen far behind schedule and had been plagued with cost overruns.

As governor, Black advocated for conservation of the area now known as the Adirondack State Park

The Adirondack Park is a part of New York's Forest Preserve in northeastern New York, United States. The park was established in 1892 for “the free use of all the people for their health and pleasure”, and for watershed protection. The park ...

. As part of this effort, he oversaw the establishment of the New York State College of Forestry

The New York State College of Forestry, the first professional school of forestry in North America, opened its doors at Cornell University, in Ithaca, New York, in the autumn of 1898., It was advocated for by Governor Frank S. Black, but after jus ...

. During Black's governorship, the boroughs that now make up New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

were consolidated into one municipality.

Black also oversaw New York's participation in the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

. Under his leadership, 16,000 New York soldiers were raised, trained, and equipped for accession into the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

as it expanded for the war. In addition, he successfully advocated for election reforms, including allowing soldiers to vote while they were out of state or outside the United States.

In his 1894 and 1896 campaigns, Black had been nominated at Republican conventions by political operative Louis F. Payn, who was widely regarded as a corrupt associate of Thomas C. Platt

Thomas Collier Platt (July 15, 1833 – March 6, 1910), also known as Tom Platt

, the boss of New York State's Republican Party. As governor, Black caused a controversy when he appointed Payn as state insurance superintendent. Despite criticism from advocates of good government and civil service reform, Black continued to support Payn. Even though he backed Payn, Black incurred Platt's displeasure when Black successfully opposed a bill Platt favored, which would have banned from newspapers editorial cartoons critical of state government officials. (As governor, Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

won a showdown with Platt over Payn's reappointment, which resulted in the selection of another candidate.)

Late in Black's term, state officials were accused of squandering taxpayer money on a project to expand the Erie Canal

The Erie Canal is a historic canal in upstate New York that runs east-west between the Hudson River and Lake Erie. Completed in 1825, the canal was the first navigable waterway connecting the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes, vastly reducing t ...

, which had come to be regarded as a boondoggle

A boondoggle is a project that is considered a waste of both time and money, yet is often continued due to extraneous policy or political motivations.

Etymology

"Boondoggle" was the name of the newspaper of the Roosevelt Troop of the Boy Sco ...

because of delays and excessive costs. Black's chances for reelection were jeopardized, so Republicans replaced him as their 1898 gubernatorial nominee with Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

, who had recently attained hero status in Cuba during the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

. Roosevelt won the November general election by narrowly defeating Democratic nominee Augustus Van Wyck

Augustus Van Wyck (October 14, 1850 – June 8, 1922) was an American judge and politician who served as Supreme Court Justice of Brooklyn, New York. In 1898 he received the Democratic Nomination for New York State governor against the Republican ...

. In 1899, an investigating commission appointed by Black, in conjunction with two special counsels appointed by Roosevelt, exonerated those involved of criminal wrongdoing.

Later life

After leaving office, Black resumed his law practice. Among the noteworthy cases in which he was involved, Black took part in the defense of Roland B. Molineaux in the famed '' People v. Molineux'' case. After Molineaux was convicted of murder, the conviction was overturned and he won an acquittal at retrial. The case was the source of the well-known " Molineux rule" which limits the ability of prosecutors to use prior crimes as proof that a defendant committed the crime with which he is charged. Black also took part in the defense of Caleb Powers for the assassination of Kentucky governor

After leaving office, Black resumed his law practice. Among the noteworthy cases in which he was involved, Black took part in the defense of Roland B. Molineaux in the famed '' People v. Molineux'' case. After Molineaux was convicted of murder, the conviction was overturned and he won an acquittal at retrial. The case was the source of the well-known " Molineux rule" which limits the ability of prosecutors to use prior crimes as proof that a defendant committed the crime with which he is charged. Black also took part in the defense of Caleb Powers for the assassination of Kentucky governor William Goebel

William Justus Goebel (January 4, 1856 – February 3, 1900) was an American Democratic politician who served as the 34th governor of Kentucky for four days in 1900, having been sworn in on his deathbed a day after being shot by an assassin. ...

.

Black maintained his interest in politics even after leaving office. He was a delegate to the 1904 Republican National Convention

The 1904 Republican National Convention was held in the Chicago Coliseum, Chicago, Cook County, Illinois, on June 21 to June 23, 1904.

The popular President Theodore Roosevelt had easily ensured himself of the nomination; a threat had come fro ...

, and nominated President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

for election to a full term. Later that year, he was a candidate for the Republican nomination for United States Senator

The United States Senate is the Upper house, upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives being the Lower house, lower chamber. Together they compose the national Bica ...

, but withdrew in favor of incumbent Chauncey Depew

Chauncey Mitchell Depew (April 23, 1834April 5, 1928) was an American attorney, businessman, and Republican politician. He is best remembered for his two terms as United States Senator from New York and for his work for Cornelius Vanderbilt, as ...

, who went on to win reelection. In 1908, Black, who had fallen out with Roosevelt, supported Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes Sr. (April 11, 1862 – August 27, 1948) was an American statesman, politician and jurist who served as the 11th Chief Justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. A member of the Republican Party, he previously was the ...

for president over Roosevelt's choice, William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

.

Black remained a popular and sought-after speaker for political events and other occasions. Among his best-known orations was a 1903 commemorative eulogy for Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

delivered to the Republican Club of the City of New York during its annual Lincoln's Birthday celebration.

Death and burial

Black died from heart disease at his home in Troy on March 22, 1913. He was cremated and his ashes were buried at his summer home, a farm inFreedom, New Hampshire

Freedom is a town located in Carroll County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 1,689 at the 2020 census, up from 1,489 at the 2010 census. The town's eastern boundary runs along the Maine state border. Ossipee Lake, with a resort ...

.

Family

In 1879, Black married Lois B. Hamlin (1858-1931) ofProvincetown, Massachusetts

Provincetown is a New England town located at the extreme tip of Cape Cod in Barnstable County, Massachusetts, in the United States. A small coastal resort town with a year-round population of 3,664 as of the 2020 United States Census, Provincet ...

, whom he had met while teaching school. They were the parents of a son, Arthur (1880-1953).

Honors

In 1898, Black received thehonorary degree

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or ''ad hono ...

of LL.D.

Legum Doctor (Latin: “teacher of the laws”) (LL.D.) or, in English, Doctor of Laws, is a doctorate-level academic degree in law or an honorary degree, depending on the jurisdiction. The double “L” in the abbreviation refers to the early ...

from Dartmouth College.

References

Sources

Books

* * * * * * * *Magazines

* *Internet

* *Newspapers

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

*Biography, Frank Swett Black

at National Governors Association

Frank S. Black

at New York State Hall of Governors

Today in Masonic History: Frank Swett Black is Born

at MasonryToday.com {{DEFAULTSORT:Black, Frank Swett 1853 births 1913 deaths People from Limington, Maine Politicians from Troy, New York Dartmouth College alumni New York (state) lawyers Journalists from New York (state) 19th-century American politicians Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives from New York (state) Republican Party governors of New York (state) 19th-century American newspaper editors Burials in New Hampshire 19th-century American lawyers