Franco-British union on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A Franco-British Union is a concept for a union between the two

A Franco-British Union is a concept for a union between the two

British offer of Franco-British Union

An unlikely marriage

Letter From Britain: Darker realities behind Britons' longing for Frangleterre

Le rêve inachevé de la Frangleterre

Prelude to Downfall: The British Offer of Union to France, June 1940

Battle of France France–United Kingdom relations Suez Crisis United Kingdom in World War II France in World War II Proposed political unions British Empire in World War II

A Franco-British Union is a concept for a union between the two

A Franco-British Union is a concept for a union between the two independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in the New Hope, Pennsylvania, area of the United States during the early 1930s

* Independe ...

sovereign state

A sovereign state or sovereign country, is a political entity represented by one central government that has supreme legitimate authority over territory. International law defines sovereign states as having a permanent population, defined ter ...

s of the United Kingdom and France. Such a union was proposed during certain crises of the 20th century; it has some historical precedents.

Historical unions

England and France

Ties between France and England have been intimate since theNorman Conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Conq ...

, in which the duke of Normandy

In the Middle Ages, the duke of Normandy was the ruler of the Duchy of Normandy in north-western France. The duchy arose out of a grant of land to the Viking leader Rollo by the French king Charles III in 911. In 924 and again in 933, Normand ...

, an important French fief, became king of England, while also owing feudal ties to the French crown.

The relationship was never stable, and it only endured as long as the French crown was weak. From 1066 to 1214, the king of England held extensive fiefs in northern France, adding to Normandy the counties of Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and nor ...

, Anjou Anjou may refer to:

Geography and titles France

*County of Anjou, a historical county in France and predecessor of the Duchy of Anjou

**Count of Anjou, title of nobility

*Duchy of Anjou, a historical duchy and later a province of France

**Duke ...

, and Touraine

Touraine (; ) is one of the traditional provinces of France. Its capital was Tours. During the political reorganization of French territory in 1790, Touraine was divided between the departments of Indre-et-Loire, :Loir-et-Cher, Indre and Vien ...

, and the Duchy of Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica during the period ...

. After 1154, the King of England was also duke of Aquitaine

The Duke of Aquitaine ( oc, Duc d'Aquitània, french: Duc d'Aquitaine, ) was the ruler of the medieval region of Aquitaine (not to be confused with modern-day Aquitaine) under the supremacy of Frankish, English, and later French kings.

As su ...

(or Guienne

Guyenne or Guienne (, ; oc, Guiana ) was an old French province which corresponded roughly to the Roman province of ''Aquitania Secunda'' and the archdiocese of Bordeaux.

The name "Guyenne" comes from ''Aguyenne'', a popular transformation of ...

), together with Poitou

Poitou (, , ; ; Poitevin: ''Poetou'') was a province of west-central France whose capital city was Poitiers. Both Poitou and Poitiers are named after the Pictones Gallic tribe.

Geography

The main historical cities are Poitiers (historical c ...

, Gascony, and other southern French fiefs dependent upon Aquitaine. Together with the northern territories, this meant that the King of England controlled more than half of France – the so-called Angevin Empire

The Angevin Empire (; french: Empire Plantagenêt) describes the possessions of the House of Plantagenet during the 12th and 13th centuries, when they ruled over an area covering roughly half of France, all of England, and parts of Ireland and W ...

– though still nominally as the king of France's vassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerai ...

. The centre of gravity of this composite realm was generally south of the English channel; four of the first seven kings after the Norman Conquest were French-born, and all were native speakers of French. For centuries thereafter the royalty and nobility of England were educated in French as well as English. In certain respects, England became an outlying province of France; English law took the strong impress of local French law, and there was an influx of French words into the English language.

This anomalous situation came to an end with the Battle of Bouvines

The Battle of Bouvines was fought on 27 July 1214 near the town of Bouvines in the County of Flanders. It was the concluding battle of the Anglo-French War of 1213–1214. Although estimates on the number of troops vary considerably among mod ...

in 1214, when King Philip II of France

Philip II (21 August 1165 – 14 July 1223), byname Philip Augustus (french: Philippe Auguste), was King of France from 1180 to 1223. His predecessors had been known as kings of the Franks, but from 1190 onward, Philip became the first French m ...

deposed King John of England

John (24 December 1166 – 19 October 1216) was King of England from 1199 until his death in 1216. He lost the Duchy of Normandy and most of his other French lands to King Philip II of France, resulting in the collapse of the Angevin ...

from his northern French fiefs; in the chaos that followed, the heir to the throne of France, later Louis VIII, was offered the throne of England by rebellious English barons from 1216 to 1217 and travelled there to take it. He was proclaimed king of England in St. Paul's Cathedral, where many nobles, including King Alexander II of Scotland

Alexander II ( Medieval Gaelic: '; Modern Gaelic: '; 24 August 1198 – 6 July 1249) was King of Scotland from 1214 until his death. He concluded the Treaty of York (1237) which defined the boundary between England and Scotland, virtually un ...

, paid him homage. He captured Winchester

Winchester is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs Nation ...

and soon controlled over half the kingdom, but after the death of King John his support dwindled and he was forced to make peace, renouncing his claim to the throne. England was ultimately able to retain a reduced Guienne

Guyenne or Guienne (, ; oc, Guiana ) was an old French province which corresponded roughly to the Roman province of ''Aquitania Secunda'' and the archdiocese of Bordeaux.

The name "Guyenne" comes from ''Aguyenne'', a popular transformation of ...

as a French fief, which was retained and enlarged when war between the two kingdoms resumed in 1337.

From 1340 to 1360, and from 1369 on, the king of England assumed the title of "king of France"; but although England was generally successful in its war with France, no attempt was made to make the title a reality during that period of time.

The situation changed with King Henry V of England

Henry V (16 September 1386 – 31 August 1422), also called Henry of Monmouth, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1413 until his death in 1422. Despite his relatively short reign, Henry's outstanding military successes in the ...

's invasion of France in 1415. By 1420, England controlled northern France (including the capital) for the first time in 200 years. King Charles VI of France

Charles VI (3 December 136821 October 1422), nicknamed the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé) and later the Mad (french: le Fol or ''le Fou''), was King of France from 1380 until his death in 1422. He is known for his mental illness and psychotic ...

was forced to disinherit his own son, the Dauphin Charles, in favour of Henry V. As Henry predeceased the French king by a few months, his son Henry VI was proclaimed king of England and of France from 1422 by the English and their allies but the Dauphin retained control over parts of central and southern France and claimed the crown for himself. From 1429 the Dauphin's party, including Joan of Arc, counterattacked and succeeded in crowning him as king.

Fighting between England and France continued for more than twenty years after, but by 1453 the English were expelled from all of France except Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's prefecture is its third-largest city of Arras. Th ...

, which was lost in 1558. England also briefly held the town of Dunkirk

Dunkirk (french: Dunkerque ; vls, label=French Flemish, Duunkerke; nl, Duinkerke(n) ; , ;) is a commune in the department of Nord in northern France.

in 1658–1662. The kings of England and their successor kings of Great Britain, purely as a habitual expression and with no associated political claim, continued to use the title "king of France" until 1801; the heads of the House of Stuart

The House of Stuart, originally spelt Stewart, was a royal house of Scotland, England, Ireland and later Great Britain. The family name comes from the office of High Steward of Scotland, which had been held by the family progenitor Walter fi ...

, out of power since 1688, used the title until their extinction in 1807.

Scotland and France

Norman or French culture first gained a foothold in Scotland during the Davidian Revolution, when KingDavid I David I may refer to:

* David I, Caucasian Albanian Catholicos c. 399

* David I of Armenia, Catholicos of Armenia (728–741)

* David I Kuropalates of Georgia (died 881)

* David I Anhoghin, king of Lori (ruled 989–1048)

* David I of Scotland ...

introduced Continental-style reforms throughout all aspects of Scottish life: social, religious, economic and administrative. He also invited immigrant French and Anglo-French peoples to Scotland. This effectively created a Franco-Scottish aristocracy, with ties to the French aristocracy as well as many to the Franco-English aristocracy. From the Wars of Scottish Independence

The Wars of Scottish Independence were a series of military campaigns fought between the Kingdom of Scotland and the Kingdom of England in the late 13th and early 14th centuries.

The First War (1296–1328) began with the English invasion of ...

, as common enemies of England and its ruling House of Plantagenet

The House of Plantagenet () was a royal house which originated from the lands of Anjou in France. The family held the English throne from 1154 (with the accession of Henry II at the end of the Anarchy) to 1485, when Richard III died in b ...

, Scotland and France started to enjoy a close diplomatic relationship, the Auld Alliance

The Auld Alliance ( Scots for "Old Alliance"; ; ) is an alliance made in 1295 between the kingdoms of Scotland and France against England. The Scots word ''auld'', meaning ''old'', has become a partly affectionate term for the long-lasting a ...

, from 1295 to 1560. From the Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Europe, the Ren ...

and into the Early Modern Period Scotland and its burgh

A burgh is an autonomous municipal corporation in Scotland and Northern England, usually a city, town, or toun in Scots. This type of administrative division existed from the 12th century, when King David I created the first royal burghs. Bur ...

s also benefited from close economic and trading links with France in addition to its links to the Low Countries, Scandinavia and the Baltic.

The prospect of dynastic union came in the 15th and 16th centuries, when Margaret

Margaret is a female first name, derived via French () and Latin () from grc, μαργαρίτης () meaning "pearl". The Greek is borrowed from Persian.

Margaret has been an English name since the 11th century, and remained popular through ...

, eldest daughter of James I of Scotland

James I (late July 139421 February 1437) was King of Scots from 1406 until his assassination in 1437. The youngest of three sons, he was born in Dunfermline Abbey to King Robert III and Annabella Drummond. His older brother David, Duke of ...

, married the future Louis XI of France

Louis XI (3 July 1423 – 30 August 1483), called "Louis the Prudent" (french: le Prudent), was King of France from 1461 to 1483. He succeeded his father, Charles VII.

Louis entered into open rebellion against his father in a short-lived revol ...

. James V of Scotland

James V (10 April 1512 – 14 December 1542) was King of Scotland from 9 September 1513 until his death in 1542. He was crowned on 21 September 1513 at the age of seventeen months. James was the son of King James IV and Margaret Tudor, and du ...

married two French brides in succession. His infant daughter, Mary I

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, and as "Bloody Mary" by her Protestant opponents, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain from January 1556 until her death in 1558. She ...

, succeeded him on his death in 1542. For many years thereafter the country was ruled under a regency led by her French mother, Mary of Guise

Mary of Guise (french: Marie de Guise; 22 November 1515 – 11 June 1560), also called Mary of Lorraine, was a French noblewoman of the House of Guise, a cadet branch of the House of Lorraine and one of the most powerful families in France. Sh ...

, who succeeded in marrying her daughter to the future Francis II of France

Francis II (french: François II; 19 January 1544 – 5 December 1560) was King of France from 1559 to 1560. He was also King consort of Scotland as a result of his marriage to Mary, Queen of Scots, from 1558 until his death in 1560.

He ...

. The young couple were king and queen of France and Scotland from 1559 until Francis died in 1560. Mary returned to a Scotland heaving with political revolt and religious revolution, which made a continuation of the alliance impossible.

Cordial economic and cultural relations did continue however, although throughout the 17th century, the Scottish establishment became increasingly Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their n ...

, often belligerent to Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, a facet which was somewhat at odds with Louis XIV

Louis XIV (Louis Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was List of French monarchs, King of France from 14 May 1643 until his death in 1715. His reign of 72 years and 110 days is the Li ...

's aggressively Catholic foreign and domestic policy. The relationship was further weakened by the Union of the Crowns

The Union of the Crowns ( gd, Aonadh nan Crùintean; sco, Union o the Crouns) was the accession of James VI of Scotland to the throne of the Kingdom of England as James I and the practical unification of some functions (such as overseas dip ...

in 1603, which meant from then on that although still independent, executive power in the Scottish government, the Crown, was shared with the Kingdom of England and Scottish foreign policy came into line more with that of England than with France.

A last episode of this Franco-Scottish friendship is the stay of Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptized 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as "The Father of Economics"——� ...

in Toulouse

Toulouse ( , ; oc, Tolosa ) is the prefecture of the French department of Haute-Garonne and of the larger region of Occitania. The city is on the banks of the River Garonne, from the Mediterranean Sea, from the Atlantic Ocean and fr ...

in 1764.

Modern concepts

''Entente cordiale'' (1904)

In April 1904 the United Kingdom and theThird French Republic

The French Third Republic (french: Troisième République, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 194 ...

signed a series of agreements, known as the ''Entente Cordiale

The Entente Cordiale (; ) comprised a series of agreements signed on 8 April 1904 between the United Kingdom and the French Republic which saw a significant improvement in Anglo-French relations. Beyond the immediate concerns of colonial de ...

'', which marked the end of centuries of intermittent conflict between the two powers, and the start of a period of peaceful co-existence. Although French historian Fernand Braudel

Fernand Braudel (; 24 August 1902 – 27 November 1985) was a French historian and leader of the Annales School. His scholarship focused on three main projects: ''The Mediterranean'' (1923–49, then 1949–66), ''Civilization and Capitalism'' ...

(1902–1985) described England and France as a single unit, nationalist political leaders from both sides were uncomfortable with the idea of such a merging.

World War II (1940)

In December 1939,Jean Monnet

Jean Omer Marie Gabriel Monnet (; 9 November 1888 – 16 March 1979) was a French civil servant, entrepreneur, diplomat, financier, administrator, and political visionary. An influential supporter of European unity, he is considered one of the ...

of the French Economic Mission in London became the head of the Anglo-French Co-ordinating Committee, which co-ordinated joint planning of the two countries' wartime economies. The Frenchman hoped for a postwar United States of Europe

The United States of Europe (USE), the European State, the European Federation and Federal Europe, is the hypothetical scenario of the European integration leading to formation of a sovereign superstate (similar to the United States of Ameri ...

and saw an Anglo-French political union as a step toward his goal. He discussed the idea with Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician of the Conservative Party who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. He is best known for his foreign policy of appeaseme ...

, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

's assistant Desmond Morton, and other British officials.

In June 1940, French Prime Minister

The prime minister of France (french: link=no, Premier ministre français), officially the prime minister of the French Republic, is the head of government of the French Republic and the leader of the Council of Ministers.

The prime minister i ...

Paul Reynaud's government faced imminent defeat in the Battle of France

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the German invasion of France during the Second Wor ...

. In March, they and the British had agreed that neither country would seek a separate peace with Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. The French cabinet on 15 June voted to ask Germany for the terms of an armistice. Reynaud, who wished to continue the war from North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, was forced to submit the proposal to Churchill's War Cabinet. He claimed that he would have to resign if the British were to reject the proposal.

The British opposed a French surrender, and in particular the possible loss of the French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

to the Germans, and so sought to keep Reynaud in office. On 14 June British diplomat Robert Vansittart and Morton wrote with Monnet and his deputy René Pleven

René Pleven (; 15 April 1901 – 13 January 1993) was a notable French politician of the Fourth Republic. A member of the Free French, he helped found the Democratic and Socialist Union of the Resistance (UDSR), a political party that was mea ...

a draft "Franco-British Union" proposal. They hoped that such a union would help Reynaud persuade his cabinet to continue the war from North Africa, but Churchill was sceptical when on 15 June the British War Cabinet discussed the proposal and a similar one from Secretary of State for India

His (or Her) Majesty's Principal Secretary of State for India, known for short as the India Secretary or the Indian Secretary, was the British Cabinet minister and the political head of the India Office responsible for the governance of th ...

Leo Amery. On the morning of 16 June, the War Cabinet agreed to the French armistice request on the condition that the French fleet sail to British harbours. This disappointed Reynaud, who had hoped to use a British rejection to persuade his cabinet to continue to fight.

Reynaud supporter Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Governm ...

had arrived in London earlier that day, however, and Monnet told him about the proposed union. De Gaulle convinced Churchill that "some dramatic move was essential to give Reynaud the support which he needed to keep his Government in the war". The Frenchman then called Reynaud and told him that the British prime minister proposed a union between their countries, an idea which Reynaud immediately supported. De Gaulle, Monnet, Vansittart, and Pleven quickly agreed to a document proclaiming a joint citizenship, foreign trade

International trade is the exchange of capital, goods, and services across international borders or territories because there is a need or want of goods or services. (see: World economy)

In most countries, such trade represents a significant ...

, currency

A currency, "in circulation", from la, currens, -entis, literally meaning "running" or "traversing" is a standardization of money in any form, in use or circulation as a medium of exchange, for example banknotes and coins.

A more general ...

, war cabinet, and military command. Churchill withdrew the armistice approval, and at 3 p.m. the War Cabinet met again to consider the union document. Despite the radical nature of the proposal, Churchill and the ministers recognized the need for a dramatic act to encourage the French and reinforce Reynaud's support within his cabinet before it met again at 5 pm.

The final "Declaration of union" approved by the British War Cabinet stated that

Churchill and De Gaulle called Reynaud to tell him about the document, and they arranged for a joint meeting of the two governments in Concarneau

Concarneau (, meaning ''Bay of Cornouaille'') is a commune in the Finistère department of Brittany in north-western France. Concarneau is bordered to the west by the Baie de La Forêt.

The town has two distinct areas: the modern town on the ...

the next day. The declaration immediately succeeded in its goal of encouraging Reynaud, who saw the union as the only alternative to surrender and who could now cite the British rejection of the armistice.

Other French leaders were less enthusiastic, however. At the 5 p.m. cabinet meeting, many called it a British "last minute plan" to steal its colonies, and said that "be nga Nazi province" was preferable to becoming a British dominion. Philippe Pétain

Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Pétain (24 April 1856 – 23 July 1951), commonly known as Philippe Pétain (, ) or Marshal Pétain (french: Maréchal Pétain), was a French general who attained the position of Marshal of France at the end of Worl ...

, a leader of the pro-armistice group, called union "fusion with a corpse". While President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Albert Lebrun

Albert François Lebrun (; 29 August 1871 – 6 March 1950) was a French politician, President of France from 1932 to 1940. He was the last president of the Third Republic. He was a member of the centre-right Democratic Republican Alliance (A ...

and some others were supportive, the cabinet's opposition stunned Reynaud. He resigned that evening without taking a formal vote on the union or an armistice, and later called the failure of the union the "greatest disappointment of my political career".

Reynaud had erred, however, by conflating opposition to the union – which a majority of the cabinet almost certainly opposed – with support for an armistice, which it almost certainly did not. If the proposal had been made a few days earlier, instead of the 16th when the French only had hours to decide between armistice and North Africa, Reynaud's cabinet might have considered it more carefully.

Pétain formed a new government that evening, which immediately decided to ask Germany for armistice terms. The British cancelled their plans to travel to Concarneau.

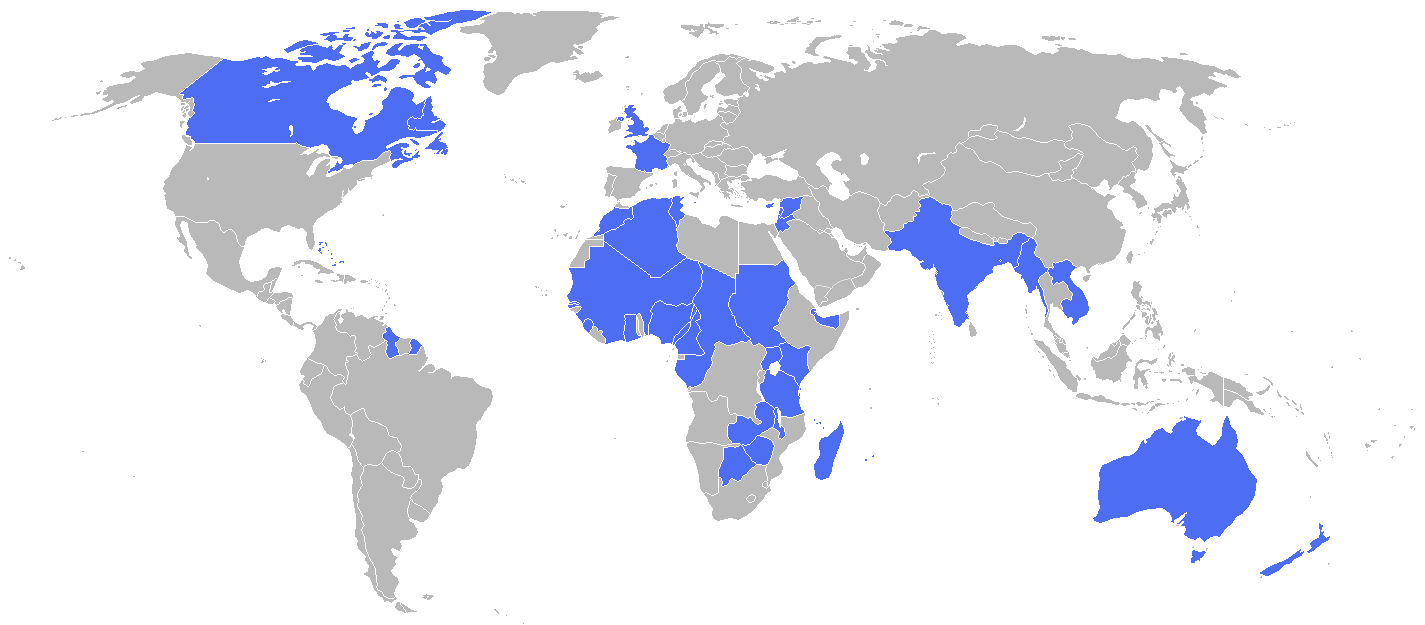

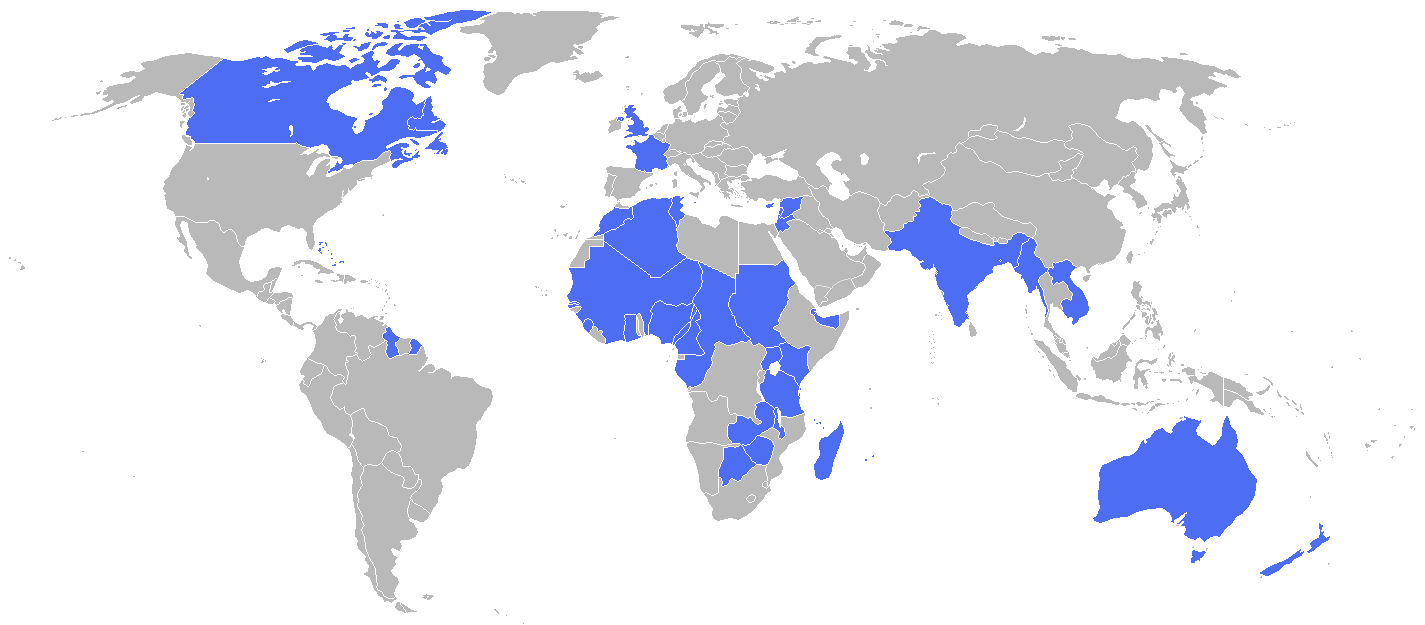

Suez Crisis (1956)

In September 1956, due to a common foe during theSuez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab–Israeli war, also called the Tripartite Aggression ( ar, العدوان الثلاثي, Al-ʿUdwān aṯ-Ṯulāṯiyy) in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel,Also known as the Suez War or 1956 Wa ...

, an Anglo-French Task Force was created. French Prime Minister Guy Mollet

Guy Alcide Mollet (; 31 December 1905 – 3 October 1975) was a French politician. He led the socialist French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO) from 1946 to 1969 and was the French Prime Minister from 1956 to 1957.

As Prime Minist ...

proposed a union between the United Kingdom and the French Union

The French Union () was a political entity created by the French Fourth Republic to replace the old French colonial empire system, colloquially known as the " French Empire" (). It was the formal end of the "indigenous" () status of French subj ...

with Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states durin ...

as head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and ...

and a common citizenship. As an alternative, Mollet proposed that France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

join the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

. The UK Prime Minister Anthony Eden

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon, (12 June 1897 – 14 January 1977) was a British Conservative Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1955 until his resignation in 1957.

Achieving rapid promo ...

rejected both proposals and France went on to join the Treaty of Rome

The Treaty of Rome, or EEC Treaty (officially the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community), brought about the creation of the European Economic Community (EEC), the best known of the European Communities (EC). The treaty was sig ...

, which established the European Economic Community

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organization created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lis ...

and strengthened the Franco-German cooperation.

When the Mollet proposal was first made public in the United Kingdom on 15 January 2007 through an article by Mike Thomson published on the BBC News website, it received rather satirical treatment in the media of both countries, including the name, coined by the BBC, of Frangleterre (merging "France" with ''Angleterre'', which is the French word for "England"). The UK broadcaster stated that Mollet's proposal originated from newly declassified material, arguing no such archive documents exist in France.

On 16 January 2007, during a LCP television programme, French journalist Christine Clerc asked former French Interior Minister Charles Pasqua

Charles Victor Pasqua (18 April 192729 June 2015) was a French businessman and Gaullist politician. He was Interior Minister from 1986 to 1988, under Jacques Chirac's '' cohabitation'' government, and also from 1993 to 1995, under the government ...

(Gaullist

Gaullism (french: link=no, Gaullisme) is a French political stance based on the thought and action of World War II French Resistance leader Charles de Gaulle, who would become the founding President of the Fifth French Republic. De Gaulle with ...

) about Mollet's 1956 proposal. Pasqua answered, "if his request had been made official, Mollet would have been brought to trial forhigh treason Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ..."..

In fiction

The Lord Darcy alternative history stories take place in a world whereRichard I of England

Richard I (8 September 1157 – 6 April 1199) was King of England from 1189 until his death in 1199. He also ruled as Duke of Normandy, Duke of Aquitaine, Aquitaine and Duchy of Gascony, Gascony, Lord of Cyprus, and Count of Poitiers, Co ...

lived much longer and managed to unite England and France under his rule; by the 20th century, ''Anglo-French'' is a common language spoken by the inhabitants on both sides of the Channel, and there is no doubt of their all being a single people.

See also

*France–United Kingdom relations

The historical ties between France and the United Kingdom, and the countries preceding them, are long and complex, including conquest, wars, and alliances at various points in history. The Roman era saw both areas largely conquered by Rome, ...

* English claims to the French throne

From the 1340s to the 19th century, excluding two brief intervals in the 1360s and the 1420s, the kings and queens of England and Ireland (and, later, of Great Britain) also claimed the throne of France. The claim dates from Edward III, who cl ...

* Gallic Empire

The Gallic Empire or the Gallic Roman Empire are names used in modern historiography for a breakaway part of the Roman Empire that functioned ''de facto'' as a separate state from 260 to 274. It originated during the Crisis of the Third Century, ...

* Carausian Revolt

References

{{ReflistExternal links

British offer of Franco-British Union

An unlikely marriage

Letter From Britain: Darker realities behind Britons' longing for Frangleterre

Le rêve inachevé de la Frangleterre

Prelude to Downfall: The British Offer of Union to France, June 1940

Battle of France France–United Kingdom relations Suez Crisis United Kingdom in World War II France in World War II Proposed political unions British Empire in World War II