France–Japan relations (19th century) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The development of France-Japan relations in the 19th century coincided with Japan's opening to the Western world, following two centuries of seclusion under the "

Japan had had numerous contacts with the West during the

Japan had had numerous contacts with the West during the

During its period of self-imposed isolation (

During its period of self-imposed isolation ( Historical events, such as the life of

Historical events, such as the life of  In 1840, the Rangaku scholar Udagawa Yōan reported for the first time in details the findings and theories of

In 1840, the Rangaku scholar Udagawa Yōan reported for the first time in details the findings and theories of

Sakoku

was the Isolationism, isolationist Foreign policy of Japan, foreign policy of the Japanese Tokugawa shogunate under which, for a period of 265 years during the Edo period (from 1603 to 1868), relations and trade between Japan and other countri ...

" system and France's expansionist policy in Asia. The two countries became very important partners from the second half of the 19th century in the military, economic, legal and artistic fields. The Bakufu

, officially , was the title of the military dictators of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, though during part of the Kamakur ...

modernized its army through the assistance of French military missions (Jules Brunet

Jules Brunet (2 January 1838 – 12 August 1911) was a French military officer who served the Tokugawa shogunate during the Boshin War in Japan. Originally sent to Japan as an artillery instructor with the French military mission of 1867, he ref ...

), and Japan later relied on France for several aspects of its modernization, particularly the development of a shipbuilding industry during the early years of the Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrender ...

(Emile Bertin

Emil or Emile may refer to:

Literature

*''Emile, or On Education'' (1762), a treatise on education by Jean-Jacques Rousseau

* ''Émile'' (novel) (1827), an autobiographical novel based on Émile de Girardin's early life

*''Emil and the Detective ...

), and the development of a Legal code. France also derived part of its modern artistic inspiration

Inspiration (from the Latin ''inspirare'', meaning "to breathe into") is an unconscious burst of creativity in a literary, musical, or visual art and other artistic endeavours. The concept has origins in both Hellenism and Hebraism. The Greeks ...

from Japanese art

Japanese art covers a wide range of art styles and media, including ancient pottery, sculpture, ink painting and calligraphy on silk and paper, ''ukiyo-e'' paintings and woodblock prints, ceramics, origami, and more recently manga and anime. It ...

, essentially through Japonism

''Japonisme'' is a French term that refers to the popularity and influence of Japanese art and design among a number of Western European artists in the nineteenth century following the forced reopening of foreign trade with Japan in 1858. Japon ...

and its influence on Impressionism

Impressionism was a 19th-century art movement characterized by relatively small, thin, yet visible brush strokes, open Composition (visual arts), composition, emphasis on accurate depiction of light in its changing qualities (often accentuating ...

, and almost completely relied on Japan for its prosperous silk industry

Context

Nanban trade period

or the , was a period in the history of Japan from the arrival of Europeans in 1543 to the first ''Sakoku'' Seclusion Edicts of isolationism in 1614. Nanban (南蛮 Lit. "Southern barbarian") is a Japanese word which had been used to designate ...

in the second half of the 16th and the early 17th century. During that period, the first contacts between the French and the Japanese occurred when the samurai

were the hereditary military nobility and officer caste of medieval and early-modern Japan from the late 12th century until their abolition in 1876. They were the well-paid retainers of the '' daimyo'' (the great feudal landholders). They h ...

Hasekura Tsunenaga

was a kirishitan Japanese samurai and retainer of Date Masamune, the daimyō of Sendai. He was of Japanese imperial descent with ancestral ties to Emperor Kanmu. Other names include Philip Francis Faxicura, Felipe Francisco Faxicura, and Phi ...

landed in the southern French city of Saint-Tropez

, INSEE = 83119

, postal code = 83990

, image coat of arms = Blason ville fr Saint-Tropez-A (Var).svg

, image flag=Flag of Saint-Tropez.svg

Saint-Tropez (; oc, Sant Tropetz, ; ) is a commune in the Var department and the region of Provence-Al ...

in 1615. François Caron

François Caron (1600–1673) was a French Huguenot refugee to the Netherlands who served the Dutch East India Company (''Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie'' or VOC) for 30 years, rising from cook's mate to the director-general at Batavia (Jak ...

, son of French Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

refugees to the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

, who entered the Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock ...

, and became the first person of French origin to set foot in Japan in 1619. He stayed in Japan for 20 years, where he became a Director for the company.

This period of contact ended with the persecution of the Christian faith in Japan, leading to a near-total closure of the country to foreign interaction. In 1636, Guillaume Courtet

Guillaume Courtet, OP (1589–1637) was a French Dominican priest who has been described as the first Frenchman to have visited Japan. He was martyred in 1637 and canonized in 1987.

Career

Courtet was born in Sérignan, near Béziers, in 1589 o ...

, a French Dominican priest, penetrated into Japan clandestinely, against the 1613 interdiction of Christianity. He was caught, tortured, and died in Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in the ...

on September 29, 1637.Omoto, p.23

Diffusion of French learning to Japan

During its period of self-imposed isolation (

During its period of self-imposed isolation (Sakoku

was the Isolationism, isolationist Foreign policy of Japan, foreign policy of the Japanese Tokugawa shogunate under which, for a period of 265 years during the Edo period (from 1603 to 1868), relations and trade between Japan and other countri ...

), Japan acquired a tremendous amount of scientific knowledge from the West, through the process of Rangaku

''Rangaku'' (Kyūjitai: /Shinjitai: , literally "Dutch learning", and by extension "Western learning") is a body of knowledge developed by Japan through its contacts with the Dutch enclave of Dejima, which allowed Japan to keep abreast of Wester ...

, in the 18th and especially the 19th century. Typically, Dutch traders in the Dejima

, in the 17th century also called Tsukishima ( 築島, "built island"), was an artificial island off Nagasaki, Japan that served as a trading post for the Portuguese (1570–1639) and subsequently the Dutch (1641–1854). For 220 years, it ...

quarter of Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in the ...

would bring to the Japanese some of the latest books about Western sciences, which would be analysed and translated by the Japanese. It is widely thought that Japan had an early start towards industrialization through this medium. French scientific knowledge was transmitted to Japan through this medium.

The first flight of a hot air balloon

A hot air balloon is a lighter-than-air aircraft consisting of a bag, called an envelope, which contains heated air. Suspended beneath is a gondola or wicker basket (in some long-distance or high-altitude balloons, a capsule), which carries p ...

by the brothers Montgolfier

The Montgolfier brothers – Joseph-Michel Montgolfier (; 26 August 1740 – 26 June 1810) and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier (; 6 January 1745 – 2 August 1799) – were aviation pioneers, balloonists and paper manufacturers from the commune A ...

in France in 1783, was reported less than four years later by the Dutch in Dejima, and published in the 1787 ''Sayings of the Dutch''. The new technology was demonstrated in 1805, almost twenty years later, when the Swiss

Swiss may refer to:

* the adjectival form of Switzerland

* Swiss people

Places

* Swiss, Missouri

* Swiss, North Carolina

*Swiss, West Virginia

* Swiss, Wisconsin

Other uses

*Swiss-system tournament, in various games and sports

*Swiss Internation ...

Johann Caspar Horner

Johann Caspar Horner (Zürich, 12 March 1774 – Zürich, 3 November 1834) was a Swiss physicist, mathematician and astronomer.

Life

At the beginning he wanted to be a priest, but later he went to Göttingen, where he learnt astronomy. Then he ...

and the Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

n Georg Heinrich von Langsdorff, two scientists of the Krusenstern mission that also brought the Russian ambassador Nikolai Rezanov

Nikolai Petrovich Rezanov (russian: Николай Петрович Резанов) ( – ), a Russian nobleman and statesman, promoted the project of Russian colonization of Alaska and California to three successive Emperors of All Russia� ...

to Japan, made a hot air balloon out of Japanese paper (washi

is traditional Japanese paper. The term is used to describe paper that uses local fiber, processed by hand and made in the traditional manner. ''Washi'' is made using fibers from the inner bark of the gampi tree, the mitsumata shrub (''Ed ...

), and made a demonstration in front of about 30 Japanese delegates. Hot air balloons would mainly remain curiosities, becoming the object of numerous experiments and popular depictions, until the development of military usages during the early Meiji era

The is an era of Japanese history that extended from October 23, 1868 to July 30, 1912.

The Meiji era was the first half of the Empire of Japan, when the Japanese people moved from being an isolated feudal society at risk of colonization b ...

.

Historical events, such as the life of

Historical events, such as the life of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

, were relayed by the Dutch and were published in contemporary Japanese books. Characteristically, some historical facts could be presented exactly (the imprisonment of Napoleon "in the African island of Saint Helena"), while others could be incorrect (such as the anachronistic depiction of the British guards wearing 16th century cuirasses

A cuirass (; french: cuirasse, la, coriaceus) is a piece of armour that covers the torso, formed of one or more pieces of metal or other rigid material. The word probably originates from the original material, leather, from the French '' cuir ...

and weapons.

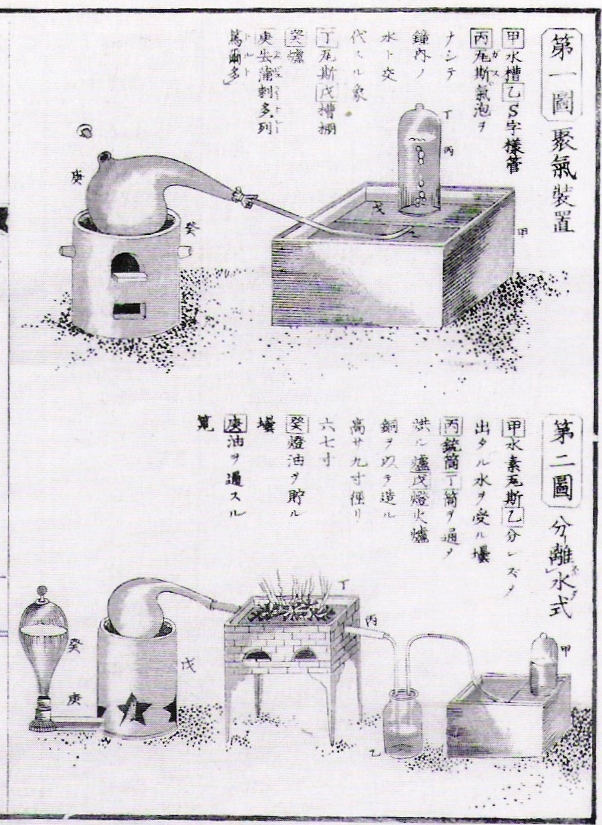

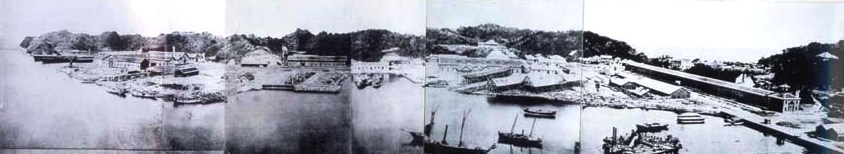

In 1840, the Rangaku scholar Udagawa Yōan reported for the first time in details the findings and theories of

In 1840, the Rangaku scholar Udagawa Yōan reported for the first time in details the findings and theories of Lavoisier

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier ( , ; ; 26 August 17438 May 1794),

CNRS (

After nearly two centuries of strictly enforced seclusion, various contacts occurred from the middle of the 19th century as France was trying to expand its influence in Asia. After the signature of the

After nearly two centuries of strictly enforced seclusion, various contacts occurred from the middle of the 19th century as France was trying to expand its influence in Asia. After the signature of the  Forcade and Ko were picked up to be used as translators in Japan, and father Leturdu was left in Tomari, soon joined by Father Mathieu Adnet. On July 24, 1846, Admiral Cécille arrived in

Forcade and Ko were picked up to be used as translators in Japan, and father Leturdu was left in Tomari, soon joined by Father Mathieu Adnet. On July 24, 1846, Admiral Cécille arrived in

During the 19th century, numerous attempts by Western countries were made (other than by the Dutch, who already had a trade post in

During the 19th century, numerous attempts by Western countries were made (other than by the Dutch, who already had a trade post in

The opening of contacts between France and Japan coincided with a series biological catastrophes in Europe, as the silk industry, in which France had a leading role centered on the city of

The opening of contacts between France and Japan coincided with a series biological catastrophes in Europe, as the silk industry, in which France had a leading role centered on the city of  Foreign silk traders started to settle in the harbour of

Foreign silk traders started to settle in the harbour of

The Japanese soon responded to these contacts by sending their own embassies to France. The ''

The Japanese soon responded to these contacts by sending their own embassies to France. The '' A Second Japanese Embassy to Europe in 1863, in an effort to pay lip service the 1863 "

A Second Japanese Embassy to Europe in 1863, in an effort to pay lip service the 1863 "

Conversely, the

Conversely, the  As the shogunate was confronted with discontent in the southern parts of the country, and foreign shipping was being fired at in violation of treaties, France participated to allied naval interventions such as the

As the shogunate was confronted with discontent in the southern parts of the country, and foreign shipping was being fired at in violation of treaties, France participated to allied naval interventions such as the

The Japanese

The Japanese  Foreign powers agreed to take a neutral stance during the Boshin war, but a large portion of the French mission resigned and joined the forces they had trained in their conflict against Imperial forces. French forces would become a target of Imperial forces, leading to the Kobe incident on January 11, 1868, in which a fight erupts in

Foreign powers agreed to take a neutral stance during the Boshin war, but a large portion of the French mission resigned and joined the forces they had trained in their conflict against Imperial forces. French forces would become a target of Imperial forces, leading to the Kobe incident on January 11, 1868, in which a fight erupts in

French weaponry also played a key role in the conflict.

French weaponry also played a key role in the conflict.

Despite its support of the losing side of the conflict during the

Despite its support of the losing side of the conflict during the

France was also highly regarded for the quality of its Legal system, and was used as an example to establish the country's legal code. Georges Bousquet taught law from 1871 to 1876. The legal expert

France was also highly regarded for the quality of its Legal system, and was used as an example to establish the country's legal code. Georges Bousquet taught law from 1871 to 1876. The legal expert

Despite the French defeat during the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871), France was still considered as an example in the military field as well, and was used as a model for the development of the

Despite the French defeat during the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871), France was still considered as an example in the military field as well, and was used as a model for the development of the

The French Navy leading engineer Émile Bertin was invited to Japan for four years (from 1886 to 1890) to reinforce the

The French Navy leading engineer Émile Bertin was invited to Japan for four years (from 1886 to 1890) to reinforce the

In a rather rare case of "reverse

In a rather rare case of "reverse

As Japan opened to Western influence, numerous Western travellers visited the country, taking a great interest in the arts and culture. The French writer

As Japan opened to Western influence, numerous Western travellers visited the country, taking a great interest in the arts and culture. The French writer

online

* Chiba, Yoko. "Japonisme: East-West renaissance in the late 19th century." ''Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature'' (1998): 1-20

online

* Curtin, Philip D. ''The World and the West. The European Challenge and the Overseas Response in the Age of Empire'' (Cambridge University Press, 2000.) * Dedet, Andre. "Pierre Loti in Japan: Impossible exoticism" ''Journal of European Studies'' (1999) 29#1 pp 21–25. Covers racist attitudes of 19th-century French naval officer and writer Pierre Loti* Foucrier, Annick, ed. ''The French and the Pacific World, 17th-19th Centuries: Explorations, Migrations, and Cultural Exchanges'' (Ashgate Pub Limited, 2005). * Hokenson, Jan. ''Japan, France, and East-West Aesthetics: French Literature, 1867-2000.'' (Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press, 2004). * Howe, Christopher. ''The origins of Japanese Trade Supremacy, Development and technology in Asia from 1540 to the Pacific War'' (U of Chicago Press 1996) * Insun, Yu. "Vietnam-China Relations in the 19th Century: Myth and Reality of the Tributary System." ''Journal of Northeast Asian History'' 6.1 (2009): 81-117

online

* Kawano, Kenji. "The French-Revolution and the Meiji-Ishin." ''International Social Science Journal'' 41.1 (1989): 45–52, compares the two revolutions. * Perrin, Noel. ''Giving up the gun'' (David R. Godine, 1976) * Put, Max. ''Plunder & Pleasure: Japanese Art in the West, 1860-1930'' (2000), 151pp covers 1860 to 1930. * Sims, Richard. "Japan'S Rejection of Alliance with France during the Franco-Chinese Dispute of 1883-1885." ''Journal Of Asian History'' 29.2 (1995): 109–148

online

* Sims, Richard.

Policy Towards the Bakufu and Meiji Japan 1854–9''

(Routledge, 1998( * Weisberg, Gabriel P. ''Japonisme: Japanese influence on French art, 1854-1910'' (1976). * White, John Albert. ''Transition to Global Rivalry: Alliance Diplomacy & the Quadruple Entente, 1895-1907'' (1995) 344 pp. re France, Japan, Russia, Britain

Japan-France Relations

{{DEFAULTSORT:France-Japan Relations (19th century)

CNRS (

Takeda Ayasaburō

, was a Japanese Rangaku scholar, and the architect of the fortress of Goryōkaku in Hokkaidō.

Takeda was born in the Ōzu Domain (modern-day Ōzu, Ehime) in 1827. He studied medicine, Western sciences (rangaku), navigation, military archite ...

built the fortresses of Goryokaku and Benten Daiba

was a key fortress of the Republic of Ezo in 1868–1869. It was located at the entrance of the bay of Hakodate, in the northern island of Hokkaidō, Japan.

Benten Daiba was built by the Japanese architect Takeda Ayasaburō on the site former ...

between 1854 and 1866, using Dutch books on military architecture describing the fortification of the French architect Vauban.

Education in the French language started in 1808 in Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in the ...

, when the Dutch Hendrik Doeff started to teach French to Japanese interpreters. The need to learn French was identified when threatening letters were sent by the Russian government in this language.Omoto, p.34

First modern contacts (1844–1864)

First contacts with Okinawa (1844)

After nearly two centuries of strictly enforced seclusion, various contacts occurred from the middle of the 19th century as France was trying to expand its influence in Asia. After the signature of the

After nearly two centuries of strictly enforced seclusion, various contacts occurred from the middle of the 19th century as France was trying to expand its influence in Asia. After the signature of the Treaty of Nanking

The Treaty of Nanjing was the peace treaty which ended the First Opium War (1839–1842) between Great Britain and the Qing dynasty of China on 29 August 1842. It was the first of what the Chinese later termed the Unequal Treaties.

In the ...

by Great Britain in 1842, both France and the United States tried to increase their efforts in the Orient.

The first contacts occurred with the Ryūkyū Kingdom

The Ryukyu Kingdom, Middle Chinese: , , Classical Chinese: (), Historical English language, English names: ''Lew Chew'', ''Lewchew'', ''Luchu'', and ''Loochoo'', Historical French name: ''Liou-tchou'', Historical Dutch name: ''Lioe-kioe'' wa ...

(modern Okinawa

is a prefecture of Japan. Okinawa Prefecture is the southernmost and westernmost prefecture of Japan, has a population of 1,457,162 (as of 2 February 2020) and a geographic area of 2,281 km2 (880 sq mi).

Naha is the capital and largest city ...

), a vassal of the Japanese fief of Satsuma Satsuma may refer to:

* Satsuma (fruit), a citrus fruit

* ''Satsuma'' (gastropod), a genus of land snails

Places Japan

* Satsuma, Kagoshima, a Japanese town

* Satsuma District, Kagoshima, a district in Kagoshima Prefecture

* Satsuma Domain, a sou ...

since 1609. In 1844, a French naval expedition under Captain Fornier-Duplan onboard ''Alcmène'' visited Okinawa

is a prefecture of Japan. Okinawa Prefecture is the southernmost and westernmost prefecture of Japan, has a population of 1,457,162 (as of 2 February 2020) and a geographic area of 2,281 km2 (880 sq mi).

Naha is the capital and largest city ...

on April 28, 1844. Trade was denied, but Father Forcade was left behind with a Chinese translator, named Auguste Ko. Forcade and Ko remained in the Ameku Shogen-ji Temple near the port Tomari, Naha

is the capital city of Okinawa Prefecture, the southernmost prefecture of Japan. As of 1 June 2019, the city has an estimated population of 317,405 and a population density of 7,939 persons per km2 (20,562 persons per sq. mi.). The total area i ...

city under strict surveillance, only able to learn the Japanese language from monks. After a period of one year, on May 1, 1846, the French ship ''Sabine'', commanded by Guérin, arrived, soon followed by ''La Victorieuse'', commanded by Charles Rigault de Genouilly

Admiral Pierre-Louis-Charles Rigault de Genouilly (, 12 April 1807 – 4 May 1873) was a French naval officer. He fought with distinction in the Crimean War and the Second Opium War, but is chiefly remembered today for his command of French and ...

, and ''Cléopâtre'', under Admiral Cécille

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

. They came with the news that Pope Gregory XVI

Pope Gregory XVI ( la, Gregorius XVI; it, Gregorio XVI; born Bartolomeo Alberto Cappellari; 18 September 1765 – 1 June 1846) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 2 February 1831 to his death in 1 June 1846. He h ...

had nominated Forcade as Bishop of Samos

Samos (, also ; el, Σάμος ) is a Greek island in the eastern Aegean Sea, south of Chios, north of Patmos and the Dodecanese, and off the coast of western Turkey, from which it is separated by the -wide Mycale Strait. It is also a separate ...

and Vicar Apostolic

A vicar (; Latin: ''vicarius'') is a representative, deputy or substitute; anyone acting "in the person of" or agent for a superior (compare "vicarious" in the sense of "at second hand"). Linguistically, ''vicar'' is cognate with the English pref ...

of Japan. Cécille offered the kingdom French protection against British expansionism, but in vain, and only obtained that two missionaries could stay.Polak 2001, p.19

Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in the ...

, but failed in his negotiations and was denied landing, and Bishop Forcade never set foot in mainland Japan. The Ryu-Kyu court in Naha

is the capital city of Okinawa Prefecture, the southernmost prefecture of Japan. As of 1 June 2019, the city has an estimated population of 317,405 and a population density of 7,939 persons per km2 (20,562 persons per sq. mi.). The total area i ...

complained in early 1847 about the presence of the French missionaries, who had to be removed in 1848.

France would have no further contacts with Okinawa for the next 7 years, until news came that Commodore Perry had obtained an agreement with the islands on July 11, 1854, following his treaty with Japan. A French cruiser arrived in Shimoda in early 1855 while the USS ''Powhatan'' was still there with the ratified treaty, but was denied contacts as a formal agreement did not exist between France and Japan. France sent an embassy under Rear-Admiral Cécille onboard ''La Virginie'' in order to obtain similar advantages to those of other Western powers. A convention was signed on November 24, 1855.

Contacts with mainland Japan (1858)

Dejima

, in the 17th century also called Tsukishima ( 築島, "built island"), was an artificial island off Nagasaki, Japan that served as a trading post for the Portuguese (1570–1639) and subsequently the Dutch (1641–1854). For 220 years, it ...

) to open trade and diplomatic relations with Japan. France made such an attempt in 1846 with the visit of Admiral Cécille to Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in the ...

, but he was denied landing.

A Frenchman by the name of Charles Delprat is known to have lived in Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in the ...

since about 1853, as a licensee to the Dutch trade. He was able to advise the initial French diplomatic efforts by Baron Gros

Antoine-Jean Gros (; 16 March 177125 June 1835) was a French painter of historical subjects. He was given title of Baron Gros in 1824.

Gros studied under Jacques-Louis David in Paris and began an independent artistic career during the French ...

in Japan. He strongly recommended against Catholic prozelitism and was influential in suppressing such intentions among French diplomats. He also presented a picture of Japan as a country which had little to learn from the West: "In studying closely the customs, the institutions, the laws of the Japanese, one concludes by asking oneself if their civilization, entirely appropriate to their country, has anything to envy in ours, or that of the United States."

The formal opening of diplomatic relations with Japan however started with the American Commodore Perry in 1852–1854, when Perry threatened to bomb Edo or blockade the country.Vié, p.99 He obtained the signature of the Convention of Kanagawa

The Convention of Kanagawa, also known as the Kanagawa Treaty (, ''Kanagawa Jōyaku'') or the Japan–US Treaty of Peace and Amity (, ''Nichibei Washin Jōyaku''), was a treaty signed between the United States and the Tokugawa Shogunate on March ...

on March 31, 1854. Soon, the 1858 Chinese defeat in the Anglo-French expedition to China

The Second Opium War (), also known as the Second Anglo-Sino War, the Second China War, the Arrow War, or the Anglo-French expedition to China, was a colonial war lasting from 1856 to 1860, which pitted the British Empire and the French Emp ...

further gave a concrete example of Western strength to Japanese leadership.

In 1858, the Treaty of Amity and Commerce between France and Japan

The Treaty of Amity and Commerce between France and Japan (Japanese: 日仏修好通商条約) (1858) opened diplomatic relations and trade between the two counties.

Description

The treaty was signed in Edo on October 9, 1858, by Jean-Baptiste ...

was signed in Edo on October 9, 1858, by Jean-Baptiste Louis Gros

Jean-Baptiste-Louis Gros (1793–1870), also known as Baron Gros, was a French diplomat and later senator, as well as a notable pioneer of photography.

Life and career

He entered the French diplomatic service in 1823 and was given the title of ...

, the commander of the French expedition in China, opening diplomatic relations between the two countries.Polak 2001, p.29 He was assisted by Charles de Chassiron

Baron Charles Gustave Martin de Chassiron (1818-1871) was a French diplomat of the 19th century. He travelled to China and Japan as one of the two ''Attachés'' of the French Embassy under Baron Gros, with the title of "Detaché extraordinaire ...

and Alfred de Moges. In 1859, Gustave Duchesne de Bellecourt

Gustave Duchesne, Prince de Bellecourt (1817 – 1881) was a French diplomat who was active in Asia, and especially in Japan. He was the first French official representative in Japan from 1859 to 1864, following the signature of the Treaty of Am ...

arrived and became the first French representative in Japan. A French Consulate was opened that year at the Temple of Saikai-ji

, more commonly , is a Japanese temple in 4-16-23, Mita, Minato, Tokyo (on the Tsuki no Misaki). Its religious sect and principal image are Pure Land Buddhism and Amitābha respectively.

This is a 26th the place where can get the green paper ...

, in Mita, Edo, at the same time as an American Consulate was established at the Temple of Zenpuku-ji

Zenpuku-ji (善福寺), also known as Azabu-san (麻布山), is a Jōdo Shinshū temple located in the Azabu district of Tokyo, Japan. It is one of the oldest Tokyo temples, after Asakusa.

History

Founded by Kūkai in 824, Zenpuku-ji was origi ...

, and a British Consulate at the Temple of Tōzen-ji

, is a Buddhist temple located in Takanawa, Minato, Tokyo, Japan. The temple belongs to the Myōshin-ji branch of the Rinzai school of Japanese Zen.Cortazzi, Hugh. (2000) ''Collected Writings of Sir Hugh Cortazzi'', Vol. II, pp. 210211. One of th ...

.

The first trilingual Japanese dictionary incorporating French was written in 1854 by Murakami Eishun Murakami may refer to:

* 3295 Murakami, a minor planet

* Murakami (crater), an impact crater on the far side of the Moon

* Murakami (name), a Japanese surname, including a list of people with the name

* Murakami, Niigata, a city in Niigata prefectu ...

, and the first large Franco-Japanese dictionary was published in 1864. The French language was taught by Mermet de Cachon in Hakodate

is a city and port located in Oshima Subprefecture, Hokkaido, Japan. It is the capital city of Oshima Subprefecture. As of July 31, 2011, the city has an estimated population of 279,851 with 143,221 households, and a population density of 412.8 ...

in 1859, or by Léon Dury in Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in the ...

between 1863 and 1873. Léon Dury, who was also French Consul in Nagasaki, taught to about 50 students every year, among whom were future politicians such as Inoue Kowashi

Viscount Inoue Kowashi was a Japanese statesman of the Meiji period.

Biography Early life

Inoue was born into a '' samurai'' family in Higo Province (present-day Kumamoto Prefecture), as the third son of ''Karō'' Iida Gongobei. In 1866 ...

or Saionji Kinmochi

Prince was a Japanese politician and statesman who served as Prime Minister of Japan from 1906 to 1908 and from 1911 to 1912. He was elevated from marquis to prince in 1920. As the last surviving member of Japan's ''genrō,'' he was the most in ...

.

Development of trade relations

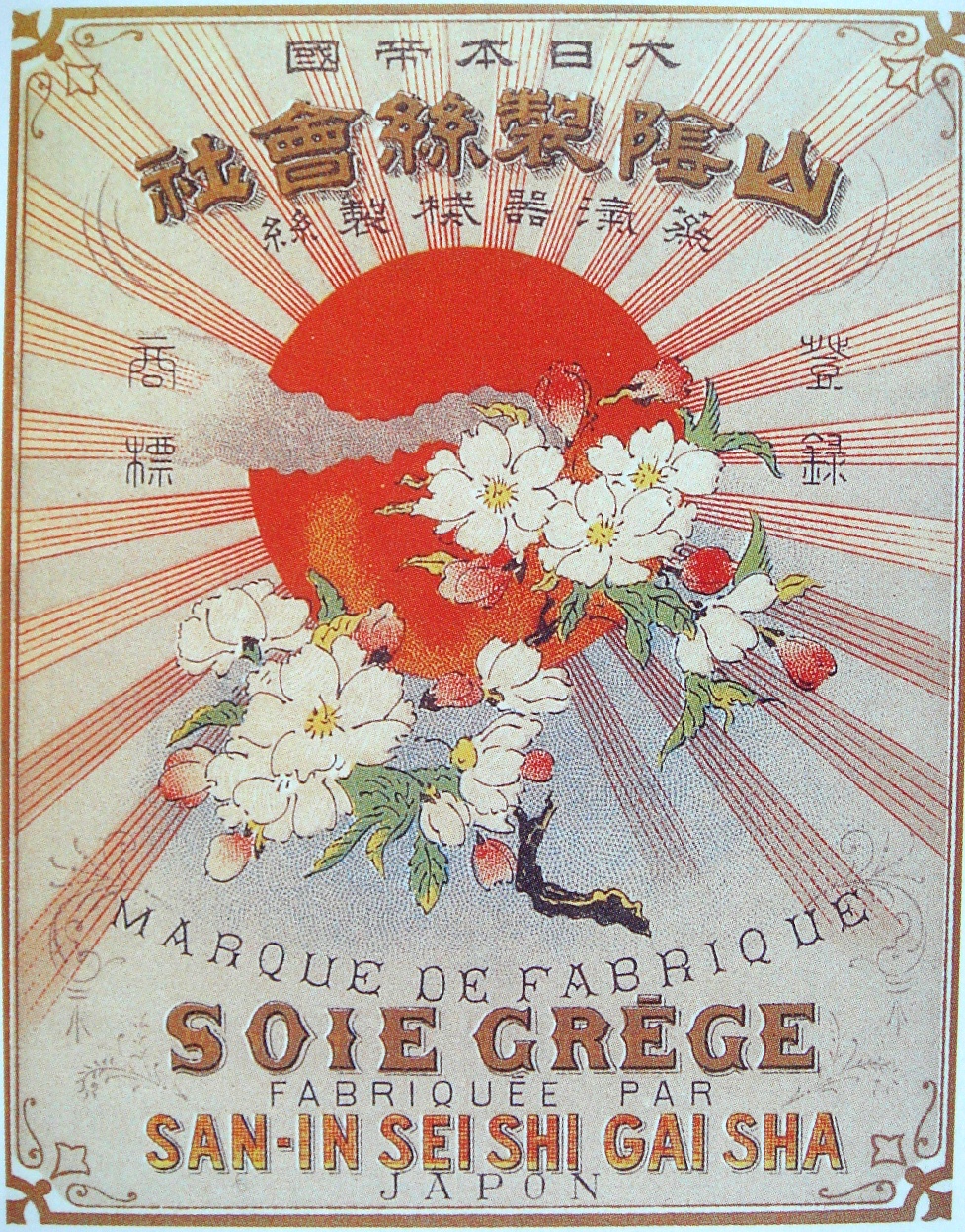

The opening of contacts between France and Japan coincided with a series biological catastrophes in Europe, as the silk industry, in which France had a leading role centered on the city of

The opening of contacts between France and Japan coincided with a series biological catastrophes in Europe, as the silk industry, in which France had a leading role centered on the city of Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of t ...

, was devastated with the appearance of various silkworm

The domestic silk moth (''Bombyx mori''), is an insect from the moth family Bombycidae. It is the closest relative of ''Bombyx mandarina'', the wild silk moth. The silkworm is the larva or caterpillar of a silk moth. It is an economically imp ...

pandemics from Spain: the "tacherie" or "muscardine", the "pébrine

Pébrine, or "pepper disease," is a disease of silkworms, which is caused by protozoan microsporidian parasites, mainly '' Nosema bombycis'' and, to a lesser extent, '' Vairimorpha'', '' Pleistophora'' and '' Thelohania'' species. The parasites i ...

" and the "flacherie".Polak 2001, p.27 From 1855, France already was forced to import 61% of its raw silks. This increased to 84% in 1860. The silkworm from Japan ''Antheraea yamamai

''Antheraea yamamai'', the Japanese silk moth or Japanese oak silkmoth (Japanese: or ) is a moth of the family Saturniidae. It is endemic to east Asia, but has been imported to Europe for tussar silk production and is now found in southeastern Eu ...

'' proved to be the only ones capable to resist to the European illnesses and were imported to France. Japanese raw silk also proved to be of the best quality on the world market.

Foreign silk traders started to settle in the harbour of

Foreign silk traders started to settle in the harbour of Yokohama

is the second-largest city in Japan by population and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city and the most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a 2020 population of 3.8 million. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of To ...

, and silk trade developed. In 1859, Louis Bourret, who already had been active in China, establishes in branch office in Yokohama for silk trade. From 1860, silk traders from Lyon are recorded in Yokohama, from where they immediately dispatched raw silk and silk worm eggs to France. For this early trade they relied on British shipping, and shipments transited through London to reach Lyon. As of 1862, 12 French people were installed in Yokohama, of whom 10 were traders.

Japanese embassies to France (1862, 1863, 1867)

The Japanese soon responded to these contacts by sending their own embassies to France. The ''

The Japanese soon responded to these contacts by sending their own embassies to France. The ''shōgun

, officially , was the title of the military dictators of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, though during part of the Kamakur ...

'' sent the First Japanese Embassy to Europe

The First Japanese Embassy to Europe (Japanese:第1回遣欧使節, also 開市開港延期交渉使節団) was sent to Europe by the Tokugawa shogunate in 1862. The head of the mission was Takenouchi Yasunori, governor of Shimotsuke Provinc ...

, led by Takenouchi Yasunori in 1862.Omoto, p.36 The mission was sent in order to learn about Western civilization, ratify treaties, and delay the opening of cities and harbour to foreign trade. Negotiation

Negotiation is a dialogue between two or more people or parties to reach the desired outcome regarding one or more issues of conflict. It is an interaction between entities who aspire to agree on matters of mutual interest. The agreement c ...

s were made in France, the UK, the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

, Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

and finally Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

. They were almost gone an entire year. On April 13, 1862, the first Japanese Minister to France delivered his credentials to Napoleon III in the Tuileries palace.

Order to expel barbarians

The was an edict issued by the Japanese Emperor Kōmei in 1863 against the Westernization of Japan following the opening of the country by Commodore Perry in 1854.

The order

The edict was based on widespread anti-foreign and legitimist sentim ...

" (攘夷実行の勅命) an edict

An edict is a decree or announcement of a law, often associated with monarchism, but it can be under any official authority. Synonyms include "dictum" and "pronouncement".

''Edict'' derives from the Latin edictum.

Notable edicts

* Telepinu Proc ...

by Emperor Kōmei

was the 121st Emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. Imperial Household Agency (''Kunaichō'')孝明天皇 (121)/ref> Kōmei's reign spanned the years from 1846 through 1867, corresponding to the final years of the ...

, and the Bombardment of Shimonoseki

The refers to a series of military engagements in 1863 and 1864, fought to control the Shimonoseki Straits of Japan by joint naval forces from Great Britain, France, the Netherlands and the United States, against the Japanese feudal domain of ...

incidents, in a wish to close again the country to Western influence, and return to sakoku

was the Isolationism, isolationist Foreign policy of Japan, foreign policy of the Japanese Tokugawa shogunate under which, for a period of 265 years during the Edo period (from 1603 to 1868), relations and trade between Japan and other countri ...

status. The mission negotiated in vain to obtain French agreement to the closure of the harbour of Yokohama

is the second-largest city in Japan by population and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city and the most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a 2020 population of 3.8 million. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of To ...

to foreign trade.

Japan also participated to the 1867 World Fair in Paris, having its own pavilion. The fair aroused considerable interest in Japan, and allowed many visitors to come in contact with Japanese art and techniques. Many Japanese representatives visited the Fair on this occasion, including a member of the House of the ''shōgun

, officially , was the title of the military dictators of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, though during part of the Kamakur ...

'', his younger brother Tokugawa Akitake

was a younger half-brother of the Japanese Shōgun Tokugawa Yoshinobu and final daimyō of Mito Domain. He represented the Tokugawa shogunate at the courts of several European powers during the final days of Bakumatsu period Japan.

Biography ...

. The southern region of Satsuma Satsuma may refer to:

* Satsuma (fruit), a citrus fruit

* ''Satsuma'' (gastropod), a genus of land snails

Places Japan

* Satsuma, Kagoshima, a Japanese town

* Satsuma District, Kagoshima, a district in Kagoshima Prefecture

* Satsuma Domain, a sou ...

(a regular opponent to the Bakufu

, officially , was the title of the military dictators of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, though during part of the Kamakur ...

) also had a representation at the World Fair, as the suzerain

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is calle ...

of the Kingdom of Naha in the Ryu Kyu islands.Vie, p.103 The Satsuma mission was composed of 20 envoys, among them 14 students, who participated to the fair, and also negotiated the purchase of weapons and mechanical looms.

Major exchanges at the end of the shogunate (1864–1867)

France decided to reinforce and formalize links with Japan by sending its second representativeLéon Roches

Léon Roches (September 27, 1809, Grenoble – 1901) was a representative of the French government in Japan from 1864 to 1868.

Léon Roches was a student at the Lycée de Tournon in Grenoble, and followed an education in Law. After only 6 mo ...

to Japan in 1864. Roches himself originated from the region of Lyon, and was therefore highly knowledgeable of the issues related to the silk industry.

Conversely, the

Conversely, the shogunate

, officially , was the title of the military dictators of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, though during part of the Kamakur ...

wished to engage in a vast program of industrial development in many areas, and in order to finance and foster it relied on the exportations of silk and the development of local resources such as mining (iron, coal, copper, silver, gold).

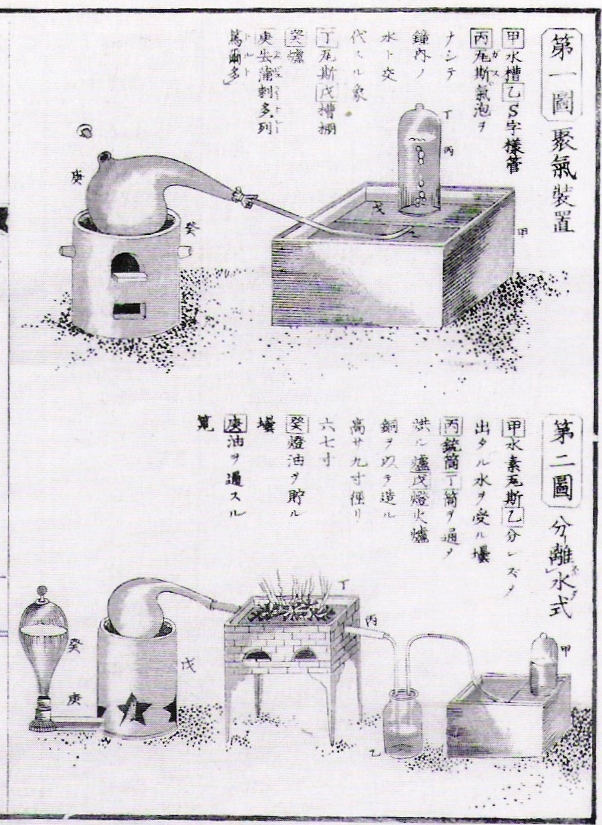

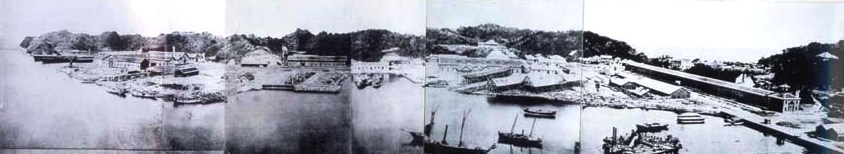

Very soon relations developed at a high pace. The Japanese shogunate, wishing to obtain foreign expertise in shipping obtained the dispatch of the French engineer Léonce Verny

François Léonce Verny, (2 December 1837 – 2 May 1908) was a French officer and naval engineerSims, Richard. (1998) ''French Policy Towards the Bakufu and Meiji Japan 1854-95: A Case of Misjudgement and Missed Opportunities,'' p. 246./ref> ...

to build the Yokosuka

is a city in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan.

, the city has a population of 409,478, and a population density of . The total area is . Yokosuka is the 11th most populous city in the Greater Tokyo Area, and the 12th in the Kantō region.

The city ...

arsenal, Japan's first modern arsenal. Verny arrived in Japan in November 1864. In June 1865, France delivered 15 cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

s to the shogunate. Verny worked together with Shibata Takenaka

was an emissary for Japan who visited France in 1865 to help prepare for the construction of the Yokosuka arsenal with French support. Also known as as well as "Shadow" because of his reconnaissance work.

Life

Takenaka was born in Edo ...

who visited France in 1865 to prepare for the construction of the Yokosuka

is a city in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan.

, the city has a population of 409,478, and a population density of . The total area is . Yokosuka is the 11th most populous city in the Greater Tokyo Area, and the 12th in the Kantō region.

The city ...

(order of the machinery) arsenal and organize a French military mission to Japan. Altogether, about 100 French workers and engineers worked in Japan to establish these early industrial plants, as well as lighthouses

A lighthouse is a tower, building, or other type of physical structure designed to emit light from a system of lamps and lenses and to serve as a beacon for navigational aid, for maritime pilots at sea or on inland waterways.

Lighthouses mark ...

, brick factories, and water transportation systems. These establishments helped Japan acquire its first knowledge of modern industry.

In the educational field as well, a school to train engineers was established in Yokosuka by Verny, and a Franco-Japanese College was established in Yokohama

is the second-largest city in Japan by population and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city and the most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a 2020 population of 3.8 million. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of To ...

in 1865.Omoto, p.27

As the shogunate was confronted with discontent in the southern parts of the country, and foreign shipping was being fired at in violation of treaties, France participated to allied naval interventions such as the

As the shogunate was confronted with discontent in the southern parts of the country, and foreign shipping was being fired at in violation of treaties, France participated to allied naval interventions such as the Bombardment of Shimonoseki

The refers to a series of military engagements in 1863 and 1864, fought to control the Shimonoseki Straits of Japan by joint naval forces from Great Britain, France, the Netherlands and the United States, against the Japanese feudal domain of ...

in 1864 (9 British, 3 French, 4 Dutch, 1 American warships).

Following the new tax treaty between Western powers and the shogunate in 1866, Great Britain, France, the United States and the Netherlands took the opportunity to establish a stronger presence in Japan by setting up true embassies in Yokohama. France built a large colonial-style embassy on northern Naka-Dōri street.

Military missions and collaboration in the Boshin war

The Japanese

The Japanese Bakufu

, officially , was the title of the military dictators of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, though during part of the Kamakur ...

government, challenged at home by factions which desired the expulsion of foreign powers and the restoration of Imperial rule, also wished to develop military skills as soon as possible. The French military took a central role in the military modernization of Japan.

Negotiations with Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

started through Shibata Takenaka

was an emissary for Japan who visited France in 1865 to help prepare for the construction of the Yokosuka arsenal with French support. Also known as as well as "Shadow" because of his reconnaissance work.

Life

Takenaka was born in Edo ...

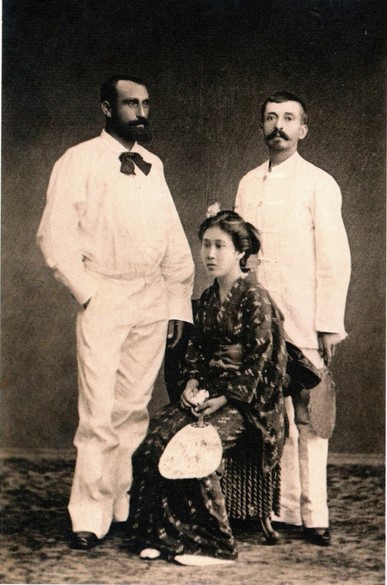

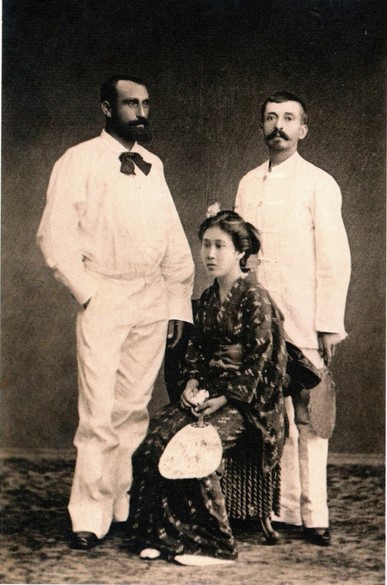

as soon as 1865. In 1867, the first French Military Mission to Japan arrived in Yokohama

is the second-largest city in Japan by population and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city and the most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a 2020 population of 3.8 million. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of To ...

, among them Captain Jules Brunet

Jules Brunet (2 January 1838 – 12 August 1911) was a French military officer who served the Tokugawa shogunate during the Boshin War in Japan. Originally sent to Japan as an artillery instructor with the French military mission of 1867, he ref ...

. The military mission would engage into a training program to modernize the armies of the shogunate, until the Boshin war

The , sometimes known as the Japanese Revolution or Japanese Civil War, was a civil war in Japan fought from 1868 to 1869 between forces of the ruling Tokugawa shogunate and a clique seeking to seize political power in the name of the Imperi ...

broke out a year later leading to a full-scale civil war between the shogunate and the pro-Imperial forces. By the end of 1867, the French mission had trained a total of 10,000 men, voluntaries and recruits, organized into seven infantry regiments, one cavalry battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of 300 to 1,200 soldiers commanded by a lieutenant colonel, and subdivided into a number of companies (usually each commanded by a major or a captain). In some countries, battalions are ...

, and four artillery battalions.Polak 2001, p.73 There is a well-known photograph of the ''shōgun'' Tokugawa Yoshinobu

Prince was the 15th and last ''shōgun'' of the Tokugawa shogunate of Japan. He was part of a movement which aimed to reform the aging shogunate, but was ultimately unsuccessful. He resigned of his position as shogun in late 1867, while aiming ...

in French uniform, taken during that period.

Foreign powers agreed to take a neutral stance during the Boshin war, but a large portion of the French mission resigned and joined the forces they had trained in their conflict against Imperial forces. French forces would become a target of Imperial forces, leading to the Kobe incident on January 11, 1868, in which a fight erupts in

Foreign powers agreed to take a neutral stance during the Boshin war, but a large portion of the French mission resigned and joined the forces they had trained in their conflict against Imperial forces. French forces would become a target of Imperial forces, leading to the Kobe incident on January 11, 1868, in which a fight erupts in Akashi Akashi may refer to:

People

*Akashi (surname)

Places

*Akashi, Hyōgo

*Akashi Station, a Japanese railroad station on the Sanyō Main Line

*Akashi Strait

*Akashi Kaikyō Bridge, crossing the former

*Akashi Castle

*Akashi Domain

* Akashi, the name ...

between 450 samurai of the Okayama

is the capital city of Okayama Prefecture in the Chūgoku region of Japan. The city was founded on June 1, 1889. , the city has an estimated population of 720,841 and a population density of 910 persons per km2. The total area is .

The city is ...

fief and French sailors, leading to the occupation of central Kobe by foreign troops. Also in 1868 eleven French sailors from the Dupleix were killed in the Sakai incident

270px, Monument to the Tosa samurai at Myōkoku-ji in Sakai

The was a diplomatic incident that occurred on March 8, 1868, in Bakumatsu period Japan involving the deaths of eleven French sailors from the French corvette ''Dupleix'' in the port ...

, in Sakai

is a city located in Osaka Prefecture, Japan. It has been one of the largest and most important seaports of Japan since the medieval era. Sakai is known for its keyhole-shaped burial mounds, or kofun, which date from the fifth century and incl ...

, near Osaka

is a designated city in the Kansai region of Honshu in Japan. It is the capital of and most populous city in Osaka Prefecture, and the third most populous city in Japan, following Special wards of Tokyo and Yokohama. With a population of 2. ...

, by southern rebel forces.

Jules Brunet

Jules Brunet (2 January 1838 – 12 August 1911) was a French military officer who served the Tokugawa shogunate during the Boshin War in Japan. Originally sent to Japan as an artillery instructor with the French military mission of 1867, he ref ...

would become a leader of the military effort of the shogunate, reorganizing its defensive efforts and accompanying it to Hokkaido until the ultimate defeat. After the fall of Edo, Jules Brunet fled north with Enomoto Takeaki

Viscount was a Japanese samurai and admiral of the Tokugawa navy of Bakumatsu period Japan, who remained faithful to the Tokugawa shogunate and fought against the new Meiji government until the end of the Boshin War. He later served in the Mei ...

, the leader of the shogunate's navy, and helped set up the Ezo Republic

The was a short-lived separatist state established in 1869 on the island of Ezo, now Hokkaido, by a part of the former military of the Tokugawa shogunate at the end of the ''Bakumatsu'' period in Japan. It was the first government to attempt t ...

, with Enomoto Takeaki as the President, Japan's only Republic ever. He also helped organize the defense of Hokkaidō

is Japan's second largest island and comprises the largest and northernmost prefecture, making up its own region. The Tsugaru Strait separates Hokkaidō from Honshu; the two islands are connected by the undersea railway Seikan Tunnel.

The la ...

in the Battle of Hakodate

The was fought in Japan from December 4, 1868 to June 27, 1869, between the remnants of the Tokugawa shogunate army, consolidated into the armed forces of the rebel Ezo Republic, and the armies of the newly formed Imperial government (composed ...

. Troops were structured under a hybrid Franco-Japanese leadership, with Otori Keisuke as Commander-in-chief, and Jules Brunet as second in command. Each of the four brigades were commanded by a French officer ( Fortant, Marlin

Marlins are fish from the family Istiophoridae, which includes about 10 species. A marlin has an elongated body, a spear-like snout or bill, and a long, rigid dorsal fin which extends forward to form a crest. Its common name is thought to deri ...

, Cazeneuve Cazeneuve may refer to:

People

*André Cazeneuve (died 1874), French soldier in Japanese service

*Bernard Cazeneuve (born 1963), French prime minister

* Jean Cazeneuve (1915–2005), French sociologist and anthropologist.

* Louis Cazeneuve (1 ...

, Bouffier), with eight Japanese commanders as second in command of each half-brigade.

Other French officers, such as the French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

officer Eugène Collache

Eugène Collache (29 January 1847 in Perpignan – 25 October 1883 in Paris) was French Navy officer who fought in Japan for the ''shōgun'' during the Boshin War.

Arrival in Japan

Eugène Collache was an officer of the French Navy in the 19t ...

, are even known to have fought on the side of the ''shōgun'' in samurai

were the hereditary military nobility and officer caste of medieval and early-modern Japan from the late 12th century until their abolition in 1876. They were the well-paid retainers of the '' daimyo'' (the great feudal landholders). They h ...

attire. These events, involving French officers rather than American ones, were nonetheless an inspiration for the depiction of an American hero in the movie ''The Last Samurai

''The Last Samurai'' is a 2003 epic period action drama film directed and co-produced by Edward Zwick, who also co-wrote the screenplay with John Logan and Marshall Herskovitz from a story devised by Logan. The film stars Ken Watanabe in the ...

''.

Weaponry

French weaponry also played a key role in the conflict.

French weaponry also played a key role in the conflict. Minié rifle

The Minié rifle was an important infantry rifle of the mid-19th century. A version was adopted in 1849 following the invention of the Minié ball in 1847 by the French Army captain Claude-Étienne Minié of the Chasseurs d'Orléans and Henr ...

s were sold in quantities. The French mission brought with them 200 cases of material, including various models of artillery pieces. The French mission also brought 25 thoroughbred

The Thoroughbred is a horse breed best known for its use in horse racing. Although the word ''thoroughbred'' is sometimes used to refer to any breed of purebred horse, it technically refers only to the Thoroughbred breed. Thoroughbreds are c ...

Arabian horse

The Arabian or Arab horse ( ar, الحصان العربي , DIN 31635, DMG ''ḥiṣān ʿarabī'') is a horse breed, breed of horse that originated on the Arabian Peninsula. With a distinctive head shape and high tail carriage, the Arabian is ...

s, which were given to the ''shōgun'' as a present from Napoleon III.

The French-built ironclad

An ironclad is a steam engine, steam-propelled warship protected by Wrought iron, iron or steel iron armor, armor plates, constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships ...

warship ''Kōtetsu'', originally purchased by the shogunate

, officially , was the title of the military dictators of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, though during part of the Kamakur ...

to the United States but suspended from delivery when the Boshin war started due to the official neutrality of foreign powers, became the first ironclad warship of the Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrender ...

when the Emperor Meiji was restored, and had a decisive role in the Naval Battle of Hakodate Bay in May 1869, which marked the end of the Boshin War

The , sometimes known as the Japanese Revolution or Japanese Civil War, was a civil war in Japan fought from 1868 to 1869 between forces of the ruling Tokugawa shogunate and a clique seeking to seize political power in the name of the Imperi ...

, and the complete establishment of the Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored practical imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Although there were ...

.

Collaboration with Satsuma

In 1867, the southern principality ofSatsuma Satsuma may refer to:

* Satsuma (fruit), a citrus fruit

* ''Satsuma'' (gastropod), a genus of land snails

Places Japan

* Satsuma, Kagoshima, a Japanese town

* Satsuma District, Kagoshima, a district in Kagoshima Prefecture

* Satsuma Domain, a sou ...

, a now-declared enemy of the Bakufu

, officially , was the title of the military dictators of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, though during part of the Kamakur ...

, also invited French technicians, such as the mining engineer François Coignet. Coignet would later become the Director of the Osaka

is a designated city in the Kansai region of Honshu in Japan. It is the capital of and most populous city in Osaka Prefecture, and the third most populous city in Japan, following Special wards of Tokyo and Yokohama. With a population of 2. ...

Mining Office.

Collaboration during the Meiji period (1868–)

Boshin War

The , sometimes known as the Japanese Revolution or Japanese Civil War, was a civil war in Japan fought from 1868 to 1869 between forces of the ruling Tokugawa shogunate and a clique seeking to seize political power in the name of the Imperi ...

, France continued to play a key role in introducing modern technologies in Japan even after the 1868 Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored practical imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Although there were ...

, encompassing not only the economic or military fields.

French residents such as Ludovic Savatier (who was in Japan from 1867 to 1871, and again from 1873 to 1876 as a Navy doctor based in Yokosuka) were able to witness the considerable acceleration in the modernization of Japan from that time:

The Iwakura mission

The Iwakura Mission or Iwakura Embassy (, ''Iwakura Shisetsudan'') was a Japanese diplomatic voyage to the United States and Europe conducted between 1871 and 1873 by leading statesmen and scholars of the Meiji period. It was not the only such m ...

visited France from December 16, 1872, to February 17, 1873, and met with President Thiers. The mission also visited various factories and took great interest in the various systems and technologies being employed. Nakae Chōmin

was the pen-name of a journalist, political theorist and statesman in Meiji-period Japan. His real name was . His major contribution was the popularization of the egalitarian doctrines of the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau in Japan ...

, who was a member of the mission staff and the Ministry of Justice A Ministry of Justice is a common type of government department that serves as a justice ministry.

Lists of current ministries of justice

Named "Ministry"

* Ministry of Justice (Abkhazia)

* Ministry of Justice (Afghanistan)

* Ministry of Just ...

, stayed in France to study the French legal system with the radical

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and ...

republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

Émile Acollas. Later he became a journalist, thinker and translator and introduced French thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

to Japan.

Trade

As trade between the two countries developed, France became the first importer of Japanese silk, absorbing more than 50% of Japan's raw silk production between 1865 and 1885. Silk remained the center of Franco-Japanese economic relations until the First World War. As of 1875,Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of t ...

had become the world center for silk processing, and Yokohama

is the second-largest city in Japan by population and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city and the most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a 2020 population of 3.8 million. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of To ...

had become the center for the supply of the raw material.Polak 2001, p.47 Around 1870, Japan produced about 8.000 tons of silk, with Lyon absorbing half of this production, and 13.000 tons in 1910, becoming the first world producer of silk, although the United States had overtaken France as the first importer of Japanese silk from around 1885. Silk exports allowed Japan to gather currencies to purchase foreign goods and technologies.

Technologies

In 1870, Henri Pelegrin was invited to direct the construction of Japan's first gas-lightning system in the streets ofNihonbashi

is a business district of Chūō, Tokyo, Japan which grew up around the bridge of the same name which has linked two sides of the Nihonbashi River at this site since the 17th century. The first wooden bridge was completed in 1603. The current ...

, Ginza

Ginza ( ; ja, 銀座 ) is a district of Chūō, Tokyo, located south of Yaesu and Kyōbashi, west of Tsukiji, east of Yūrakuchō and Uchisaiwaichō, and north of Shinbashi. It is a popular upscale shopping area of Tokyo, with numerous intern ...

and Yokohama

is the second-largest city in Japan by population and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city and the most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a 2020 population of 3.8 million. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of To ...

. In 1872, Paul Brunat

Paul may refer to:

*Paul (given name), a given name (includes a list of people with that name)

*Paul (surname), a list of people

People

Christianity

*Paul the Apostle (AD c.5–c.64/65), also known as Saul of Tarsus or Saint Paul, early Chris ...

opened the first modern Japanese silk spinning factory at Tomioka. Three craftsmen from the Nishijin weaving district in Kyoto, Sakura tsuneshichi, Inoue Ihee and Yoshida Chushichi traveled to Lyon. They traveled back to Japan in 1873, importing a Jacquard loom

The Jacquard machine () is a device fitted to a loom that simplifies the process of manufacturing textiles with such complex patterns as brocade, damask and matelassé. The resulting ensemble of the loom and Jacquard machine is then called a Ja ...

. Tomioka became Japan's first large-scale silk-reeling factory, and an example for the industrialization of the country.

France was also highly regarded for the quality of its Legal system, and was used as an example to establish the country's legal code. Georges Bousquet taught law from 1871 to 1876. The legal expert

France was also highly regarded for the quality of its Legal system, and was used as an example to establish the country's legal code. Georges Bousquet taught law from 1871 to 1876. The legal expert Gustave Émile Boissonade

Gustave Émile Boissonade de Fontarabie (7 June 1825 – 27 June 1910) was a French legal scholar, responsible for drafting much of Japan's civil code during the Meiji Era, and honored as one of the founders of modern Japan's legal system.

Bio ...

was sent to Japan in 1873 to help build a modern legal system, and helped the country through 22 years.

Japan again participated to the 1878 World Fair in Paris. Every time France was deemed to have a specific expertise, its technologies were introduced. In 1882, the first tramways were introduced from France and started to function at Asakusa

is a district in Taitō, Tokyo, Japan. It is known as the location of the Sensō-ji, a Buddhist temple dedicated to the bodhisattva Kannon. There are several other temples in Asakusa, as well as various festivals, such as the .

History

The ...

, and between Shinbashi

, sometimes transliterated Shimbashi, is a district of Minato, Tokyo, Japan.

Name

Read literally, the characters in Shinbashi mean "new bridge".

History

The area was the site of a bridge built across the Shiodome River in 1604. The river was la ...

and Ueno

is a district in Tokyo's Taitō Ward, best known as the home of Ueno Park. Ueno is also home to some of Tokyo's finest cultural sites, including the Tokyo National Museum, the National Museum of Western Art, and the National Museum of Na ...

. In 1898, the first automobile was introduced in Japan, a French Panhard-Levassor

Panhard was a French motor vehicle manufacturer that began as one of the first makers of automobiles. It was a manufacturer of light tactical and military vehicles. Its final incarnation, now owned by Renault Trucks Defense, was formed ...

.

Military collaboration

Despite the French defeat during the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871), France was still considered as an example in the military field as well, and was used as a model for the development of the

Despite the French defeat during the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871), France was still considered as an example in the military field as well, and was used as a model for the development of the Imperial Japanese Army

The was the official ground-based armed force of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945. It was controlled by the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office and the Ministry of the Army, both of which were nominally subordinate to the Emperor o ...

. As soon as 1872, a second French military mission to Japan (1872–80) was invited, with the objective of organizing the army and establishing a military educational system. The mission established the Ichigaya Military Academy (), built in 1874, on the ground of today's Ministry of Defense

{{unsourced, date=February 2021

A ministry of defence or defense (see spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is an often-used name for the part of a government responsible for matters of defence, found in states ...

. In 1877, the modernized Imperial Japanese Army would defeat the Satsuma rebellion

The Satsuma Rebellion, also known as the was a revolt of disaffected samurai against the new imperial government, nine years into the Meiji Era. Its name comes from the Satsuma Domain, which had been influential in the Restoration and beca ...

led by Saigō Takamori

was a Japanese samurai and nobleman. He was one of the most influential samurai in Japanese history and one of the three great nobles who led the Meiji Restoration. Living during the late Edo and early Meiji periods, he later led the Satsum ...

.

A third French military mission to Japan (1884–89) composed of five men started in 1884, but this time the Japanese also involved some German officers for the training of the General Staff

A military staff or general staff (also referred to as army staff, navy staff, or air staff within the individual services) is a group of officers, enlisted and civilian staff who serve the commander of a division or other large military un ...

from 1886 to 1889 (the Meckel Mission), although the training of the rest of the Officers remained to the French mission. After 1894, Japan did not employ any foreign military instructor, until 1918 when the country welcomed the fourth French military mission to Japan (1918–19)

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

, with the objective of acquiring technologies and techniques in the burgeoning area of military aviation

Military aviation comprises military aircraft and other flying machines for the purposes of conducting or enabling aerial warfare, including national airlift ( air cargo) capacity to provide logistical supply to forces stationed in a war the ...

.

Formation of the Imperial Japanese Navy

The French Navy leading engineer Émile Bertin was invited to Japan for four years (from 1886 to 1890) to reinforce the

The French Navy leading engineer Émile Bertin was invited to Japan for four years (from 1886 to 1890) to reinforce the Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrender ...

, and direct the construction of the arsenals of Kure

is a port and major shipbuilding city situated on the Seto Inland Sea in Hiroshima Prefecture, Japan. With a strong industrial and naval heritage, Kure hosts the second-oldest naval dockyard in Japan and remains an important base for the Japan M ...

and Sasebo

is a core city located in Nagasaki Prefecture, Japan. It is also the second largest city in Nagasaki Prefecture, after its capital, Nagasaki. On 1 June 2019, the city had an estimated population of 247,739 and a population density of 581 persons p ...

. For the first time, with French assistance, the Japanese were able to build a full fleet, some of it built in Japan, some of it in France and a few other European nations. The three cruisers designed by Emile Bertin (''Matsushima

is a group of islands in Miyagi Prefecture, Japan. There are some 260 tiny islands (''shima'') covered in pines (''matsu'') – hence the name – and it is considered to be one of the Three Views of Japan.

Nearby cultural properties ...

'', ''Itsukushima

is an island in the western part of the Inland Sea of Japan, located in the northwest of Hiroshima Bay. It is popularly known as , which in Japanese means "Shrine Island". The island is one of Hayashi Gahō's Three Views of Japan specified in ...

'', and ''Hashidate

The is a limited express train service operated by West Japan Railway Company (JR West) in Japan. One of the services making up JR West's "Big X Network", it connects Kyoto Station, Amanohashidate Station and Toyooka Station via the Sanin Mai ...

'') were equipped with 12.6in (32 cm) Canet guns

The Canet guns were a series of weapon systems developed by the French engineer Gustave Canet (1846–1908), who worked as an engineer from 1872 to 1881 for the London Ordnance Works, then for Forges et Chantiers de la Méditerranée, and from 1 ...

, an extremely powerful weapon for the time. These efforts contributed to the Japanese victory in the First Sino-Japanese war

The First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 1894 – 17 April 1895) was a conflict between China and Japan primarily over influence in Korea. After more than six months of unbroken successes by Japanese land and naval forces and the loss of the po ...

.

This period also allowed Japan "to embrace the revolutionary new technologies embodied in torpedoes, torpedo-boats and mines, of which the French at the time were probably the world's best exponents".

Japanese influences on France

Silk technology

Rangaku

''Rangaku'' (Kyūjitai: /Shinjitai: , literally "Dutch learning", and by extension "Western learning") is a body of knowledge developed by Japan through its contacts with the Dutch enclave of Dejima, which allowed Japan to keep abreast of Wester ...

" (that is, the science of isolationist Japan making its way to the West), an 1803 treatise on the raising of silk worm

Silk is a natural fiber, natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be weaving, woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoon (silk), cocoons. The be ...

s and manufacture of silk, the was brought to Europe by von Siebold and translated into French and Italian in 1848, contributing to the development of the silk industry in Europe.

In 1868, Léon de Rosny

Leon, Léon (French) or León (Spanish) may refer to:

Places

Europe

* León, Spain, capital city of the Province of León

* Province of León, Spain

* Kingdom of León, an independent state in the Iberian Peninsula from 910 to 1230 and again f ...

published a translation of a Japanese work on silk worms: ''Traité de l'éducation des vers a soie au Japon''. In 1874, Ernest de Bavier published a detailed study of the silk industry in Japan (''La sericulture, le commerce des soies et des graines et l'industrie de la soie au Japon'', 1874).

Arts

Japanese art

Japanese art covers a wide range of art styles and media, including ancient pottery, sculpture, ink painting and calligraphy on silk and paper, ''ukiyo-e'' paintings and woodblock prints, ceramics, origami, and more recently manga and anime. It ...

decisively influenced the art of France, and the art of the West in general during the 19th century. From the 1860s, ukiyo-e

Ukiyo-e is a genre of Japanese art which flourished from the 17th through 19th centuries. Its artists produced woodblock prints and paintings

Painting is the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a solid surfac ...

, a genre of Japanese wood-block print

Woodblock printing or block printing is a technique for printing text, images or patterns used widely throughout East Asia and originating in China in antiquity as a method of printing on textiles and later paper. Each page or image is crea ...

s and paintings, became a source of inspiration for many European impressionist painters in France and the rest of the West, and eventually for Art Nouveau