Fletcher Christian on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Fletcher Christian (25 September 1764 – 20 September 1793) was master's mate on board HMS ''Bounty'' during

Christian was survived by Maimiti and his son, Thursday October Christian (born 1790). Besides Thursday October, Fletcher Christian also had a younger son named Charles Christian (born 1792) and a daughter Mary Ann Christian (born 1793). Thursday and Charles are the ancestors of almost everybody with the surname Christian on

Christian was survived by Maimiti and his son, Thursday October Christian (born 1790). Besides Thursday October, Fletcher Christian also had a younger son named Charles Christian (born 1792) and a daughter Mary Ann Christian (born 1793). Thursday and Charles are the ancestors of almost everybody with the surname Christian on

Christian was portrayed in films by:

* Wilton Powers in '' The Mutiny of the Bounty'' (1916)

*

Christian was portrayed in films by:

* Wilton Powers in '' The Mutiny of the Bounty'' (1916)

*

So Good It Hurts

' (Sin Record Company/Cooking Vinyl, Rough Trade Records Germany) (1988) * Rasputina "Cage in a Cave" from Oh Perilous World (Filthy Bonnet) (2007) *

History of Pitcairn Island

Genealogical information The following genealogical information about Fletcher Christian and the other ''Bounty'' crew members comes from descendants of the ''Bounty'' crew, who may not be reliable and from historical archives.

HMS Bounty Ancestors and Cousins

George Snell's HMS ''Bounty'' Descendants Page

Norfolk Island Research and Genealogy Centre

Related information

Fletcher Christian's biography

PISC Crew Encyclopedia

Pitcairn Islands Study Centre

(PISC) {{DEFAULTSORT:Christian, Fletcher English people murdered abroad English murder victims History of Norfolk Island 18th-century pirates HMS Bounty mutineers People from Cockermouth People murdered in the Pitcairn Islands Pitcairn Islands people of Manx descent Royal Navy officers 1764 births 1793 deaths People from Dearham English emigrants to the Pitcairn Islands English people of Manx descent Castaways Pitcairn Islands people 18th-century Manx people

Lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

William Bligh

Vice-Admiral William Bligh (9 September 1754 – 7 December 1817) was an officer of the Royal Navy and a colonial administrator. The mutiny on the HMS ''Bounty'' occurred in 1789 when the ship was under his command; after being set adrift i ...

's voyage to Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Austra ...

during 1787–1789 for breadfruit

Breadfruit (''Artocarpus altilis'') is a species of flowering tree in the mulberry and jackfruit family ( Moraceae) believed to be a domesticated descendant of '' Artocarpus camansi'' originating in New Guinea, the Maluku Islands, and the Phil ...

plants. In the mutiny on the ''Bounty'', Christian seized command of the ship from Bligh on 28 April 1789. Some of the mutineers were left on Tahiti, while Christian, eight other mutineers, six Tahitian men and eleven Tahitian women settled on isolated Pitcairn Island

Pitcairn Island is the only inhabited island of the Pitcairn Islands, of which many inhabitants are descendants of mutineers of HMS ''Bounty''.

Geography

The island is of volcanic origin, with a rugged cliff coastline. Unlike many other ...

, and ''Bounty'' was burned. After the settlement was discovered in 1808, the sole surviving mutineer gave conflicting accounts of how Christian died.

Early life

Christian was born on 25 September 1764, at his family home of Moorland Close, Eaglesfield, nearCockermouth

Cockermouth is a market town and civil parish in the Borough of Allerdale in Cumbria, England, so named because it is at the confluence of the River Cocker as it flows into the River Derwent. The mid-2010 census estimates state that Cocke ...

in Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is a historic counties of England, historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th c ...

, England. Fletcher's father's side had originated from the Isle of Man

)

, anthem = " O Land of Our Birth"

, image = Isle of Man by Sentinel-2.jpg

, image_map = Europe-Isle_of_Man.svg

, mapsize =

, map_alt = Location of the Isle of Man in Europe

, map_caption = Location of the Isle of Man (green)

in Europ ...

and most of his paternal great-grandfathers were historic Deemsters, their original family surname McCrystyn.

Fletcher was the brother to Edward

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sax ...

and Humphrey, being the three sons of Charles Christian of Moorland Close and of the large Ewanrigg Hall estate in Dearham, Cumberland, an attorney-at-law descended from Manx gentry, and his wife Ann Dixon.

Charles's marriage to Ann brought with it the small property of Moorland Close, "a quadrangle pile of buildings ... half castle, half farmstead." The property can be seen to the north of the Cockermouth to Egremont A5086 road. Charles died in 1768 when Fletcher was not yet four. Ann proved herself grossly irresponsible with money. By 1779, when Fletcher was fifteen, Ann had run up a debt of nearly £6,500 (equal to £ today), and faced the prospect of debtors' prison

A debtors' prison is a prison for people who are unable to pay debt. Until the mid-19th century, debtors' prisons (usually similar in form to locked workhouses) were a common way to deal with unpaid debt in Western Europe.Cory, Lucinda"A Histori ...

. Moorland Close was lost and Ann and her three younger children were forced to flee to the Isle of Man, to their relative's estate, where English creditors had no power.

The three elder Christian sons managed to arrange a £40 (equal to £ today) per year annuity for their mother, allowing the family to live in genteel poverty. Christian spent seven years at the Cockermouth Free School from the age of nine. One of his younger contemporaries there was Cockermouth native William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (7 April 177023 April 1850) was an English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication '' Lyrical Ballads'' (1798).

Wordsworth's ' ...

. It is commonly suggested that the two were "school friends"; in fact, Christian was six years older than Wordsworth. His mother Ann died on the Isle of Man in 1819.

Naval career

:''Seehere

Here is an adverb that means "in, on, or at this place". It may also refer to:

Software

* Here Technologies, a mapping company

* Here WeGo (formerly Here Maps), a mobile app and map website by Here

Television

* Here TV (formerly "here!"), a ...

for a comparison of assignments to William Bligh''

Fletcher Christian began his naval career at a late age, joining the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

as a cabin boy when he was already seventeen years old (the average age for this position was between 12 to 15). He served for over a year on a third-rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy, a third rate was a ship of the line which from the 1720s mounted between 64 and 80 guns, typically built with two gun decks (thus the related term two-decker). Years of experience proved that the thi ...

ship-of-the-line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which depended on the two colu ...

along with his future commander, William Bligh, who was posted as the ship's sixth lieutenant. Christian next became a midshipman

A midshipman is an officer of the lowest rank, in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Canada (Naval Cadet), Australia, Bangladesh, Namibia, New Zealand, South Af ...

on the sixth-rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy used to categorise sailing warships, a sixth-rate was the designation for small warships mounting between 20 and 28 carriage-mounted guns on a single deck, sometimes with smaller guns on the upper works a ...

post ship HMS ''Eurydice'' and was made Master's Mate six months after the ship put to sea. The muster rolls of indicate Christian was signed on for a 21-month voyage to India. The ship's muster shows Christian's conduct was more than satisfactory because "some seven months out from England, he had been promoted from midshipman to master's mate".

After ''Eurydice'' had returned from India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

, Christian was reverted to midshipman and paid off from the Royal Navy. Unable to find another midshipman assignment, Christian decided to join the British merchant fleet and applied for a berth on board William Bligh's ship ''Britannia''. Bligh had himself been discharged from the Royal Navy and was now a merchant captain. Bligh accepted Christian on the ship's books as an able seaman

An able seaman (AB) is a seaman and member of the deck department of a merchant ship with more than two years' experience at sea and considered "well acquainted with his duty". An AB may work as a watchstander, a day worker, or a combination o ...

, but granted him all the rights of a ship's officer including dining and berthing in the officer quarters. On a second voyage to Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of Hispa ...

with Bligh, Christian was rated as the ship's Second Mate.

In 1787 Bligh approached Christian to serve on board HMAV ''Bounty'' for a two-year voyage to transport breadfruit

Breadfruit (''Artocarpus altilis'') is a species of flowering tree in the mulberry and jackfruit family ( Moraceae) believed to be a domesticated descendant of '' Artocarpus camansi'' originating in New Guinea, the Maluku Islands, and the Phil ...

from Tahiti to the West Indies. Bligh originally had every intention of Christian serving as the ship's Master, but the Navy Board turned down this request due to Christian's low seniority in service years and appointed John Fryer John Fryer may refer to:

*John Fryer (physician) (died 1563), English physician, humanist and early reformer

*John Fryer (physician, died 1672), English physician

*John Fryer (travel writer) (1650–1733), British travel-writer and doctor

*Sir John ...

instead. Christian was retained as Master's Mate. The following year, halfway through the Bounty's voyage, Bligh appointed Christian as acting lieutenant, thus making him senior to Fryer.

On 28 April 1789, Fletcher Christian led a mutiny on board the ''Bounty'' and from this point forward was considered an outlaw. He was formally stripped of his naval rank in March 1790 and discharged after Bligh returned to England and reported the mutiny to the Admiralty Board.

Mutiny on the ''Bounty''

In 1787, Christian was appointed master's mate on ''Bounty'', on Bligh's recommendation, for the ship'sbreadfruit

Breadfruit (''Artocarpus altilis'') is a species of flowering tree in the mulberry and jackfruit family ( Moraceae) believed to be a domesticated descendant of '' Artocarpus camansi'' originating in New Guinea, the Maluku Islands, and the Phil ...

expedition to Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Austra ...

. During the voyage out, Bligh appointed him acting lieutenant. ''Bounty'' arrived at Tahiti on 26 October 1788 and Christian spent the next five months there.

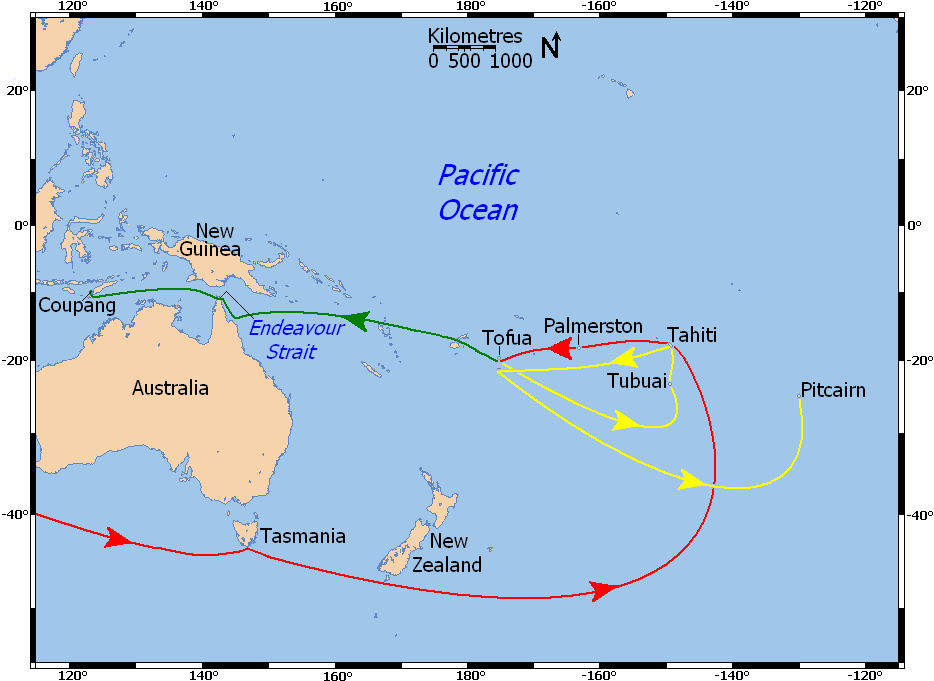

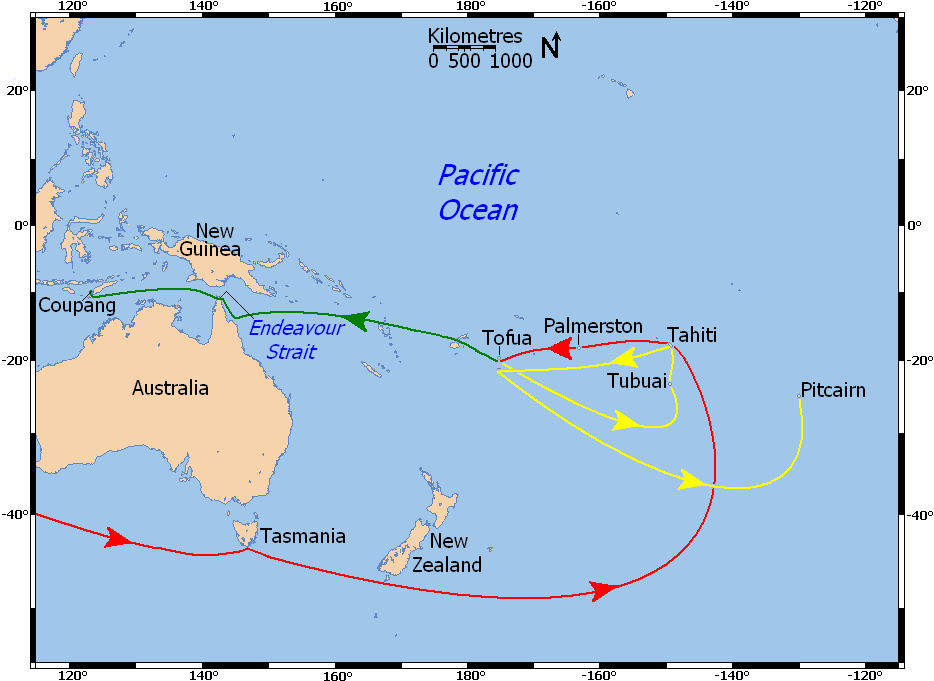

''Bounty'' set sail with its cargo of breadfruit plantings on 4 April 1789. Some 1,300 miles west of Tahiti, near Tonga

Tonga (, ; ), officially the Kingdom of Tonga ( to, Puleʻanga Fakatuʻi ʻo Tonga), is a Polynesian country and archipelago. The country has 171 islands – of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in ...

, mutiny broke out on 28 April 1789, led by Christian. According to accounts, the sailors were attracted to the "idyllic" life and sexual opportunities afforded on the Pacific island of Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Austra ...

. Following the court-martial of captured mutineers, Edward Christian

Edward Christian (3 March 1758 – 29 March 1823) was an English judge and law professor. He was the older brother of Fletcher Christian, leader of the mutiny on the ''Bounty''.

Life

Edward Christian was one of the three sons of Charles Ch ...

argued that they were motivated by Bligh's allegedly harsh treatment of them. Eighteen mutineers set Bligh afloat in a small boat with eighteen of the twenty-two crew loyal to him.

Following the mutiny, Christian first travelled to Tahiti, where he married Maimiti, the daughter of one of the local chiefs. He then attempted to build a colony on Tubuai

Tubuai or Tupuai is the main island of the Austral Island group, located south of Tahiti. In addition to Tubuai, the group of islands include Rimatara, Rurutu, Raivavae, Rapa and the uninhabited Îles Maria. They are part of the Austral Isla ...

, but there the mutineers came into conflict with natives. Abandoning the island, he stopped briefly in Tahiti again, and dropped off sixteen crewmen. These sixteen included four Bligh loyalists who had been left behind on ''Bounty'' and two who had neither participated in, nor resisted, the mutiny. The remaining nine mutineers, six Tahitian men and eleven Tahitian women, then sailed eastward. In time, they landed on Pitcairn Island

Pitcairn Island is the only inhabited island of the Pitcairn Islands, of which many inhabitants are descendants of mutineers of HMS ''Bounty''.

Geography

The island is of volcanic origin, with a rugged cliff coastline. Unlike many other ...

, where they stripped ''Bounty'' of all that could be floated ashore before Matthew Quintal set it on fire, stranding them. The resulting sexual imbalance, combined with the effective enslavement of the Tahitian men by the mutineers, led to insurrection and the deaths of most of the men.

Death

The American seal-hunting ship ''Topaz'' visited Pitcairn in 1808 and found only one mutineer,John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

(who had used the alias Alexander Smith while on ''Bounty''), still alive along with nine Tahitian women. The mutineers who had perished had, however, already had children with their Tahitian wives. Most of these children were still living. Adams and Maimiti claimed Christian had been murdered during the conflict between the Tahitian men and the mutineers. According to an account by a Pitcairn woman named Jenny who left the island in 1817, Christian was shot while working by a pond next to the home of his pregnant wife. Along with Christian, four other mutineers and all six of the Tahitian men who had come to the island were killed in the conflict. William McCoy, one of the four surviving mutineers, fell off a cliff while intoxicated and was killed. Quintal was later killed by the remaining two mutineers, Adams and Ned Young, after he attacked them. Young became the new leader of Pitcairn.

John Adams gave conflicting accounts of Christian's death to visitors on ships that subsequently visited Pitcairn. He was variously said to have died of natural causes, committed suicide, become insane or been murdered.

Christian was survived by Maimiti and his son, Thursday October Christian (born 1790). Besides Thursday October, Fletcher Christian also had a younger son named Charles Christian (born 1792) and a daughter Mary Ann Christian (born 1793). Thursday and Charles are the ancestors of almost everybody with the surname Christian on

Christian was survived by Maimiti and his son, Thursday October Christian (born 1790). Besides Thursday October, Fletcher Christian also had a younger son named Charles Christian (born 1792) and a daughter Mary Ann Christian (born 1793). Thursday and Charles are the ancestors of almost everybody with the surname Christian on Pitcairn

The Pitcairn Islands (; Pitkern: '), officially the Pitcairn, Henderson, Ducie and Oeno Islands, is a group of four volcanic islands in the southern Pacific Ocean that form the sole British Overseas Territory in the Pacific Ocean. The four i ...

and Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the Nor ...

Islands, as well as the many descendants who have moved to Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

, New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

.

Rumours have persisted for more than two hundred years that Christian's murder was faked, that he had left the island and that he made his way back to England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

. Many scholars believe that the rumours of Christian returning to England helped to inspire Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who, with his friend William Wordsworth, was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lak ...

's ''The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

''The Rime of the Ancient Mariner'' (originally ''The Rime of the Ancyent Marinere'') is the longest major poem by the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, written in 1797–1798 and published in 1798 in the first edition of '' Lyrical Ball ...

''.

There is no portrait or drawing extant of Fletcher Christian that was drawn from life. Bligh described Christian as "5 ft. 9 in. high 75 cm blackish or very dark complexion. Hair – Blackish or very dark brown. Make – Strong. A star tatowed on his left breast, and tatowed on the backside. His knees stand a little out and he may be called a little bow legged. He is subject to violent perspiration, particularly in his hand, so that he soils anything he handles".

Portrayals in the arts

Appearances in literature

Christian's principal literary appearances are in the treatments of ''Bounty'' story, including '' Mutiny on the Bounty'' (1932), '' Pitcairn's Island'' (1934) and ''After the Bounty'' (an edited version of James Morrison's journal, 2009). He also appears in R. M. Ballantyne's ''The Lonely Island; or, The Refuge of the Mutineers'' (1880) and inCharles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian er ...

' '' The Long Voyage'' (1853).

In Peter F. Hamilton's '' Night's Dawn'' trilogy, Fletcher Christian's ghost appears, possessing a human body, and helps two non-possessed girls escape. William Kinsolving's 1996 novel ''Mister Christian'' and Val McDermid

Valarie "Val" McDermid, (born 4 June 1955) is a Scottish crime writer, best known for a series of novels featuring clinical psychologist Dr. Tony Hill in a grim sub-genre that McDermid and others have identified as Tartan Noir.

Biography

...

's 2006 thriller ''The Grave Tattoo'' are both based on Christian's rumoured return to the Lake District

The Lake District, also known as the Lakes or Lakeland, is a mountainous region in North West England. A popular holiday destination, it is famous for its lakes, forests, and mountains (or '' fells''), and its associations with William Wordswor ...

and the fact that he was at school with William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (7 April 177023 April 1850) was an English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication '' Lyrical Ballads'' (1798).

Wordsworth's ' ...

. Dan L. Thrapp's 2002 novel ''Mutiny's Curse '' is based on a similar premise. In 1959 Louis MacNeice

Frederick Louis MacNeice (12 September 1907 – 3 September 1963) was an Irish poet and playwright, and a member of the Auden Group, which also included W. H. Auden, Stephen Spender and Cecil Day-Lewis. MacNeice's body of work was widely ...

produced a BBC Radio play called ''I Call Me Adam'', written by Laurie Lee

Laurence Edward Alan "Laurie" Lee, MBE (26 June 1914 – 13 May 1997) was an English poet, novelist and screenwriter, who was brought up in the small village of Slad in Gloucestershire.

His most notable work is the autobiographical trilo ...

, about the mutineers' lives on Pitcairn.

Film portrayals

Christian was portrayed in films by:

* Wilton Powers in '' The Mutiny of the Bounty'' (1916)

*

Christian was portrayed in films by:

* Wilton Powers in '' The Mutiny of the Bounty'' (1916)

* Errol Flynn

Errol Leslie Thomson Flynn (20 June 1909 – 14 October 1959) was an Australian-American actor who achieved worldwide fame during the Classical Hollywood cinema, Golden Age of Hollywood. He was known for his romantic swashbuckler roles, freque ...

in ''In the Wake of the Bounty

''In the Wake of the Bounty'' (1933) is an Australian film directed by Charles Chauvel about the 1789 Mutiny on the Bounty. It is notable as the screen debut of Errol Flynn, playing Fletcher Christian. The film preceded MGM's more famous ''Mutin ...

'' (1933)

* Clark Gable

William Clark Gable (February 1, 1901November 16, 1960) was an American film actor, often referred to as "The King of Hollywood". He had roles in more than 60 motion pictures in multiple genres during a career that lasted 37 years, three decades ...

in '' Mutiny on the Bounty'' (1935)

* Marlon Brando

Marlon Brando Jr. (April 3, 1924 – July 1, 2004) was an American actor. Considered one of the most influential actors of the 20th century, he received numerous accolades throughout his career, which spanned six decades, including two Academ ...

in '' Mutiny on the Bounty'' (1962)

* Mel Gibson

Mel Columcille Gerard Gibson (born January 3, 1956) is an American actor, film director, and producer. He is best known for his action hero roles, particularly his breakout role as Max Rockatansky in the first three films of the post-apoca ...

in '' The Bounty'' (1984)

The 1935 and 1962 films are based on the 1932 novel '' Mutiny on the Bounty'' in which Christian is a major character and is generally portrayed positively. The authors of that novel, Charles Nordhoff

Charles Bernard Nordhoff (February 1, 1887 – April 10, 1947) was an American novelist and traveler, born in England. Nordhoff is perhaps best known for '' The Bounty Trilogy'', three historical novels he wrote with James Norman Hall: ''Mutiny ...

and James Norman Hall, also wrote two sequels, one of which, '' Pitcairn's Island'', is the story of the tragic events after the mutiny that apparently resulted in Christian's death along with other violent deaths on Pitcairn Island

Pitcairn Island is the only inhabited island of the Pitcairn Islands, of which many inhabitants are descendants of mutineers of HMS ''Bounty''.

Geography

The island is of volcanic origin, with a rugged cliff coastline. Unlike many other ...

. (The other sequel, '' Men Against the Sea'', is the story of Bligh's voyage after the mutiny.) This series of novels uses fictionalised versions of minor crew members as narrators of the stories.

'' The Bounty,'' released in 1984, is less sympathetic to Christian than previous treatments were.

Musical portrayal

* David Essex in ''Mutiny!'' (1985) *Mekons

The Mekons are a British band formed in the late 1970s as an art collective. They are one of the longest-running and most prolific of the first-wave British punk rock bands.

The band's style has evolved over time to incorporate aspects of ...

"(Sometimes I Feel Like) Fletcher Christian" from So Good It Hurts

' (Sin Record Company/Cooking Vinyl, Rough Trade Records Germany) (1988) * Rasputina "Cage in a Cave" from Oh Perilous World (Filthy Bonnet) (2007) *

The Rolling Stones

The Rolling Stones are an English rock band formed in London in 1962. Active for six decades, they are one of the most popular and enduring bands of the rock era. In the early 1960s, the Rolling Stones pioneered the gritty, rhythmically dr ...

“(Dancing in the Light)”

See also

*Garth Christian

Garth Christian was an English nature writer, editor, teacher and conservationist.

Life

He was born in a Derbyshire vicarage which had been occupied by his father and grandfather for almost 50 years, and was a member of the same family as Flet ...

– a relative

* Descendants of the Bounty mutineers – Thomas Colman Christian, who died 7 July 2013.

References

Notes Bibliography * * * * Further reading * * Christian, Harrison (2021). ''Men Without Country: The true story of exploration and rebellion in the South Seas''. Ultimo Press. 2021. . * Conway, Christiane (2005). ''Letters from the Isle of Man – The Bounty – Correspondence of Nessy and Peter Heywood''. The Manx Experience. .External links

General informationHistory of Pitcairn Island

Genealogical information The following genealogical information about Fletcher Christian and the other ''Bounty'' crew members comes from descendants of the ''Bounty'' crew, who may not be reliable and from historical archives.

HMS Bounty Ancestors and Cousins

George Snell's HMS ''Bounty'' Descendants Page

Norfolk Island Research and Genealogy Centre

Related information

Fletcher Christian's biography

PISC Crew Encyclopedia

Pitcairn Islands Study Centre

(PISC) {{DEFAULTSORT:Christian, Fletcher English people murdered abroad English murder victims History of Norfolk Island 18th-century pirates HMS Bounty mutineers People from Cockermouth People murdered in the Pitcairn Islands Pitcairn Islands people of Manx descent Royal Navy officers 1764 births 1793 deaths People from Dearham English emigrants to the Pitcairn Islands English people of Manx descent Castaways Pitcairn Islands people 18th-century Manx people