Ficus Aurea on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Ficus aurea'', commonly known as the Florida strangler fig (or simply strangler fig), golden fig, or ''higuerón'', is a tree in the family

''Ficus aurea'' is a tree which may reach heights of . It is

''Ficus aurea'' is a tree which may reach heights of . It is

Flora Mesoamericana: Lista Anotada. Retrieved on 2008-07-02 It grows from sea level up to 1,800 m (5,500 ft)

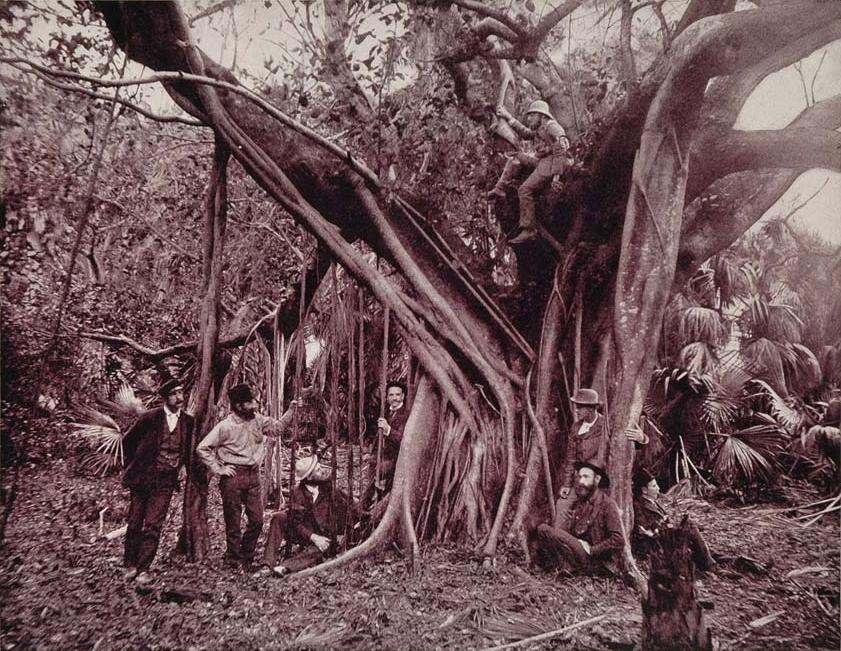

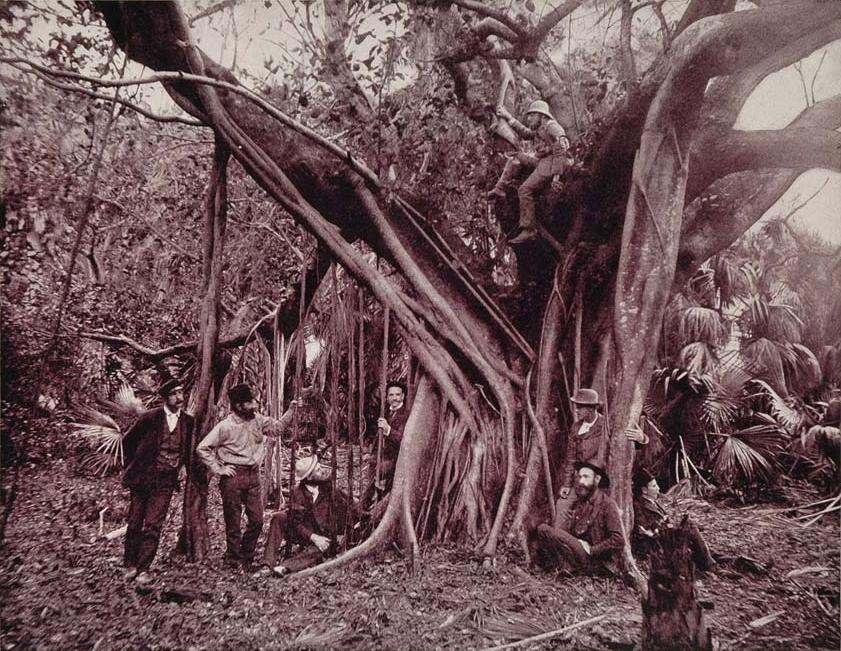

''Ficus aurea'' is a strangler fig—it tends to establish on a host tree which it gradually encircles and "strangles", eventually taking the place of that tree in the forest canopy. While this makes ''F. aurea'' an agent in the mortality of other trees, there is little to indicate that its choice of hosts is species specific. However, in

''Ficus aurea'' is a strangler fig—it tends to establish on a host tree which it gradually encircles and "strangles", eventually taking the place of that tree in the forest canopy. While this makes ''F. aurea'' an agent in the mortality of other trees, there is little to indicate that its choice of hosts is species specific. However, in

Interactive Distribution Map for Ficus aurea

{{Taxonbar, from=Q2561277 aurea Trees of the Caribbean Trees of Central America Flora of Florida Trees of Mexico Plants described in 1846 Taxa named by Thomas Nuttall Epiphytes Garden plants of North America Plants used in bonsai Ornamental trees Flora without expected TNC conservation status

Moraceae

The Moraceae — often called the mulberry family or fig family — are a family of flowering plants comprising about 38 genera and over 1100 species. Most are widespread in tropical and subtropical regions, less so in temperate climates; however ...

that is native to the U.S. state of Florida

Florida is a U.S. state, state located in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia (U.S. state), Geo ...

, the northern and western Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean S ...

, southern Mexico

Mexico ( Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Gua ...

and Central America

Central America ( es, América Central or ) is a subregion of the Americas. Its boundaries are defined as bordering the United States to the north, Colombia to the south, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. ...

south to Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a List of transcontinental countries#North America and South America, transcontinental country spanning the Central America, southern ...

. The specific epithet ''aurea'' was applied by English botanist Thomas Nuttall

Thomas Nuttall (5 January 1786 – 10 September 1859) was an English botanist and zoologist who lived and worked in America from 1808 until 1841.

Nuttall was born in the village of Long Preston, near Settle in the West Riding of Yorkshire an ...

who described the species in 1846.

''Ficus aurea'' is a strangler fig

Strangler fig is the common name for a number of tropical and subtropical plant species in the genus ''Ficus'', including those that are commonly known as banyans. Some of the more well-known species are:

* '' Ficus altissima''

* '' Ficus aurea'' ...

. In figs of this group, seed germination usually takes place in the canopy of a host

A host is a person responsible for guests at an event or for providing hospitality during it.

Host may also refer to:

Places

* Host, Pennsylvania, a village in Berks County

People

* Jim Host (born 1937), American businessman

* Michel Hos ...

tree with the seedling living as an epiphyte

An epiphyte is an organism that grows on the surface of a plant and derives its moisture and nutrients from the air, rain, water (in marine environments) or from debris accumulating around it. The plants on which epiphytes grow are called phoroph ...

until its roots establish contact with the ground. After that, it enlarges and strangles its host, eventually becoming a free-standing tree in its own right. Individuals may reach in height. Like all figs, it has an obligate mutualism with fig wasp

Fig wasps are wasps of the superfamily Chalcidoidea which spend their larval stage inside figs. Most are pollinators but others simply feed off the plant. The non-pollinators belong to several groups within the superfamily Chalcidoidea, while the ...

s: figs are only pollinated by fig wasps, and fig wasps can only reproduce in fig flowers. The tree provides habitat, food and shelter for a host of tropical lifeforms including epiphytes in cloud forests

A cloud forest, also called a water forest, primas forest, or tropical montane cloud forest (TMCF), is a generally tropical or subtropical, evergreen, montane, moist forest characterized by a persistent, frequent or seasonal low-level cloud ...

and bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweig ...

s, mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fu ...

s, reptile

Reptiles, as most commonly defined are the animals in the class Reptilia ( ), a paraphyletic grouping comprising all sauropsids except birds. Living reptiles comprise turtles, crocodilians, squamates ( lizards and snakes) and rhynchoce ...

s and invertebrate

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chorda ...

s. ''F. aurea'' is used in traditional medicine

Traditional medicine (also known as indigenous medicine or folk medicine) comprises medical aspects of traditional knowledge that developed over generations within the folk beliefs of various societies, including indigenous peoples, before the ...

, for live fencing, as an ornamental Ornamental may refer to:

*Ornamental grass, a type of grass grown as a decoration

* Ornamental iron, mild steel that has been formed into decorative shapes, similar to wrought iron work

*Ornamental plant, a plant that is grown for its ornamental qu ...

and as a bonsai

Bonsai ( ja, 盆栽, , tray planting, ) is the Japanese art of growing and training miniature trees in pots, developed from the traditional Chinese art form of ''penjing''. Unlike ''penjing'', which utilizes traditional techniques to produce ...

.

Description

''Ficus aurea'' is a tree which may reach heights of . It is

''Ficus aurea'' is a tree which may reach heights of . It is monoecious

Monoecy (; adj. monoecious ) is a sexual system in seed plants where separate male and female cones or flowers are present on the same plant. It is a monomorphic sexual system alongside gynomonoecy, andromonoecy and trimonoecy.

Monoecy is con ...

: each tree bears functional male and female flowers. The size and shape of the leaves is variable. Some plants have leaves that are usually less than 10 cm (4 in) long while others have leaves that are larger. The shape of the leaves and of the leaf base also varies—some plants have leaves that are oblong or elliptic with a wedge-shaped to rounded base, while others have heart-shaped or ovate leaves with cordate

Cordate is an adjective meaning 'heart-shaped' and is most typically used for:

* Cordate (leaf shape), in plants

* Cordate axe, a prehistoric stone tool

See also

* Chordate

A chordate () is an animal of the phylum Chordata (). All chordate ...

to rounded bases. ''F. aurea'' has paired figs which are green when unripe, turning yellow as they ripen. They differ in size (0.6–0.8 cm .2–0.3 in about 1 cm .4 in or 1.0–1.2 cm .4–0.5 inin diameter); figs are generally sessile

Sessility, or sessile, may refer to:

* Sessility (motility), organisms which are not able to move about

* Sessility (botany), flowers or leaves that grow directly from the stem or peduncle of a plant

* Sessility (medicine), tumors and polyps that ...

, but in parts of northern Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area in southern North America and most of Central America. It extends from approximately central Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica ...

figs are borne on short stalks known as peduncles.

Taxonomy

With about 750 species, ''Ficus

''Ficus'' ( or ) is a genus of about 850 species of woody trees, shrubs, vines, epiphytes and hemiepiphytes in the family Moraceae. Collectively known as fig trees or figs, they are native throughout the tropics with a few species extending in ...

'' (Moraceae

The Moraceae — often called the mulberry family or fig family — are a family of flowering plants comprising about 38 genera and over 1100 species. Most are widespread in tropical and subtropical regions, less so in temperate climates; however ...

) is one of the largest angiosperm

Flowering plants are plants that bear flowers and fruits, and form the clade Angiospermae (), commonly called angiosperms. The term "angiosperm" is derived from the Greek words ('container, vessel') and ('seed'), and refers to those plants t ...

genera (David Frodin of Chelsea Physic Garden

The Chelsea Physic Garden was established as the Apothecaries' Garden in London, England, in 1673 by the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries to grow plants to be used as medicines. This four acre physic garden, the term here referring to the sc ...

ranked it as the 31st largest genus). ''Ficus aurea'' is classified in the subgenus

In biology, a subgenus (plural: subgenera) is a taxonomic rank directly below genus.

In the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, a subgeneric name can be used independently or included in a species name, in parentheses, placed between t ...

''Urostigma'' (the strangler figs) and the section

Section, Sectioning or Sectioned may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* Section (music), a complete, but not independent, musical idea

* Section (typography), a subdivision, especially of a chapter, in books and documents

** Section sig ...

''Americana''. Recent molecular phylogenies have shown that subgenus ''Urostigma'' is polyphyletic

A polyphyletic group is an assemblage of organisms or other evolving elements that is of mixed evolutionary origin. The term is often applied to groups that share similar features known as homoplasies, which are explained as a result of conver ...

, but have strongly supported the validity of section ''Americana'' as a discrete group

In mathematics, a topological group ''G'' is called a discrete group if there is no limit point in it (i.e., for each element in ''G'', there is a neighborhood which only contains that element). Equivalently, the group ''G'' is discrete if and on ...

(although its exact relationship to section ''Galoglychia'' is unclear).

Thomas Nuttall

Thomas Nuttall (5 January 1786 – 10 September 1859) was an English botanist and zoologist who lived and worked in America from 1808 until 1841.

Nuttall was born in the village of Long Preston, near Settle in the West Riding of Yorkshire an ...

described the species in the second volume of his 1846 work ''The North American Sylva'' with specific epithet ''aurea'' ('golden' in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

). In 1768, Scottish botanist Philip Miller

Philip Miller FRS (1691 – 18 December 1771) was an English botanist and gardener of Scottish descent. Miller was chief gardener at the Chelsea Physic Garden for nearly 50 years from 1722, and wrote the highly popular '' The Gardeners Dic ...

described '' Ficus maxima'', citing Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his Nobility#Ennoblement, ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalise ...

' ''Hortus Cliffortianus

The ''Hortus Cliffortianus'' is a work of early botanical literature published in 1737.

The work was a collaboration between Carl Linnaeus and the illustrator Georg Dionysius Ehret, financed by George Clifford in 1735-1736. Clifford, a wealthy A ...

'' (1738) and Hans Sloane

Sir Hans Sloane, 1st Baronet (16 April 1660 – 11 January 1753), was an Irish physician, naturalist, and collector, with a collection of 71,000 items which he bequeathed to the British nation, thus providing the foundation of the British Mu ...

's ''Catalogus plantarum quæ in insula Jamaica'' (1696). Sloane's illustration of the species, published in 1725, depicted it with figs borne singly, a characteristic of the ''Ficus'' subgenus '' Pharmacosycea''. As a member of the subgenus '' Urostigma'', ''F. aurea'' has paired figs. However, a closer examination of Sloane's description led Cornelis Berg to conclude that the illustration depicted a member of the subgenus ''Urostigma'' (since it had other diagnostic of that subgenus), almost certainly ''F. aurea'', and that the illustration of singly borne figs was probably artistic license

Artistic license (alongside more contextually-specific derivative terms such as poetic license, historical license, dramatic license, and narrative license) refers to deviation from fact or form for artistic purposes. It can include the alterat ...

. Berg located the plant collection upon which Sloane's illustration was based and concluded that Miller's ''F. maxima'' was, in fact, ''F. aurea''. In his description of ''F. aurea'', which was based on plant material collected in Florida, Thomas Nuttall considered the possibility that his plants belonged to the species that Sloane had described, but came to the conclusion that it was a new species. Under the rules of botanical nomenclature

Botanical nomenclature is the formal, scientific naming of plants. It is related to, but distinct from taxonomy. Plant taxonomy is concerned with grouping and classifying plants; botanical nomenclature then provides names for the results of this ...

, the name ''F. maxima'' has priority over ''F. aurea'' since Miller's description was published in 1768, while Nuttall's description was published in 1846.

In their 1914 ''Flora of Jamaica'', William Fawcett William or Bill Fawcett or ''variation'', may refer to:

People

* William Fawcett (actor) (1894–1974), American actor who was awarded the ''Légion d'honneur''

* William Fawcett (author) (1902–1941), English journalist and writer on horses, hun ...

and Alfred Barton Rendle

Alfred Barton Rendle FRS (19 January 1865 – 11 January 1938) was an English botanist.

Rendle was born in Lewisham to John Samuel and Jane Wilson Rendle.

He was educated in Lewisham where he first became interested in plants, St Olave's Gra ...

linked Sloane's illustration to the tree species that was then known as ''Ficus suffocans'', a name that had been assigned to it in August Grisebach

August Heinrich Rudolf Grisebach () was a German botanist and phytogeographer. He was born in Hannover on 17 April 1814 and died in Göttingen on 9 May 1879.

Biography

Grisebach studied at the Lyceum in Hanover, the cloister-school at Ilfeld, ...

's ''Flora of the British West Indian Islands''. Gordon DeWolf agreed with their conclusion and used the name ''F. maxima'' for that species in the 1960 ''Flora of Panama''.DeWolf, Gordon P., Jr. "Ficus (Tourn.) L." in Since this use has become widespread, Berg proposed that the name ''Ficus maxima'' be conserved in the way DeWolf had used it, a proposal that was accepted by the nomenclatural committee.

Reassigning the name ''Ficus maxima'' did not leave ''F. aurea'' as the oldest name for this species, as German naturalist Johann Heinrich Friedrich Link

Johann Heinrich Friedrich Link (2 February 1767 – 1 January 1851) was a German naturalist and botanist.

Biography

Link was born at Hildesheim as a son of the minister August Heinrich Link (1738–1783), who taught him love of nature throug ...

had described ''Ficus ciliolosa'' in 1822. Berg concluded that the species Link described was actually ''F. aurea'', and since Link's description predated Nuttall's by 24 years, priority should have been given to the name ''F. ciliolosa''. Since the former name was widely used and the name ''F. ciliolosa'' had not been, Berg proposed that the name ''F. aurea'' be conserved. In response to this, the nomenclatural committee ruled that rather than conserving ''F. aurea'', that it would be better to reject ''F. ciliolosa''. Conserving ''F. aurea'' would mean that precedence would be given to that name over all others. By simply rejecting ''F. ciliolosa'', the committee left open the possibility that the name ''F. aurea'' could be supplanted by another older name, if one were to be discovered.

Synonyms

In 1920, American botanist Paul C. Standley described three new species based on collections from Panama and Costa Rica—''Ficus tuerckheimii'', ''F. isophlebia'' and ''F. jimenezii''. DeWolf concluded that they were all the same species, and Berg synonymised them with ''F. aurea''. These names have been used widely for Mexican and Central American populations, and continue to be used by some authors. Berg suspected that ''Ficus rzedowskiana'' Carvajal and Cuevas-Figueroa may also belong to this species, but he had not examined the original material upon which this species was based. Berg considered ''F. aurea'' to be a species with at least four morphs. "None of the morphs", he wrote, "can be related to certain habitats or altitudes." Thirty years earlier, William Burger had come to a very different conclusion with respect to ''Ficus tuerckheimii'', ''F. isophlebia'' and ''F. jimenezii''—he rejected DeWolf's synonymisation of these three species as based on incomplete evidence. Burger noted that the three taxa occupied different habitats which could be separated in terms of rainfall and elevation.Reproduction and growth

Figs have an obligate mutualism withfig wasp

Fig wasps are wasps of the superfamily Chalcidoidea which spend their larval stage inside figs. Most are pollinators but others simply feed off the plant. The non-pollinators belong to several groups within the superfamily Chalcidoidea, while the ...

s, (Agaonidae); figs are only pollinated by these wasps, and they can only reproduce in fig flowers. Generally, each fig species depends on a single species of wasp for pollination. The wasps are similarly dependent on their fig species in order to reproduce. ''Ficus aurea'' is pollinated by '' Pegoscapus mexicanus'' ( Ashmead).

Figs have complicated inflorescence

An inflorescence is a group or cluster of flowers arranged on a stem that is composed of a main branch or a complicated arrangement of branches. Morphologically, it is the modified part of the shoot of seed plants where flowers are formed o ...

s called syconia

Syconium (plural ''syconia'') is the type of inflorescence borne by figs (genus ''Ficus''), formed by an enlarged, fleshy, hollow receptacle with multiple ovaries on the inside surface. In essence, it is really a fleshy stem with a number of flow ...

. Flowers are entirely contained within an enclosed structure. Their only connection with the outside is through a small pore called ostiole

An ''ostiole'' is a small hole or opening through which algae or fungi release their mature spores.

The word is a diminutive of "ostium", "opening".

The term is also used in higher plants, for example to denote the opening of the involuted ...

. Monoecious

Monoecy (; adj. monoecious ) is a sexual system in seed plants where separate male and female cones or flowers are present on the same plant. It is a monomorphic sexual system alongside gynomonoecy, andromonoecy and trimonoecy.

Monoecy is con ...

figs like ''F. aurea'' have both male and female flowers within the syconium. Female flowers mature first. Once mature, they produce a volatile chemical attractant. Female wasps squeeze their way through the ostiole into the interior of the syconium. Inside the syconium, they pollinate the flowers, lay their eggs in some of them, and die. The eggs hatch and the larvae parasitise the flowers in which they were laid. After four to seven weeks (in ''F. aurea''), adult wasps emerge. Males emerge first, mate with the females, and cut exit holes through the walls of the fig. The male flowers mature around the same time as the female wasps emerge. The newly emerged female wasps actively pack their bodies with pollen from the male flowers before leaving through the exit holes the males have cut and fly off to find a syconium in which to lay their eggs. Over the next one to five days, figs ripen. The ripe figs are eaten by various mammals and birds which disperse the seeds.

Phenology

Figs flower and fruit asynchronously. Flowering and fruiting is staggered throughout the population. This fact is important for fig wasps—female wasps need to find a syconium in which to lay their eggs within a few days of emergence, something that would not be possible if all the trees in a population flowered and fruited at the same time. This also makes figs important food resources forfrugivore

A frugivore is an animal that thrives mostly on raw fruits or succulent fruit-like produce of plants such as roots, shoots, nuts and seeds. Approximately 20% of mammalian herbivores eat fruit. Frugivores are highly dependent on the abundance and ...

s (animals that feed nearly exclusively on fruit); figs are one of the few fruit available at times of the year when fruit are scarce.

Although figs flower asynchronously as a population, in most species flowering is synchronised within an individual. Newly emerged female wasps must move away from their natal tree in order to find figs in which to lay their eggs. This is to the advantage of the fig, since it prevents self-pollination

Self-pollination is a form of pollination in which pollen from the same plant arrives at the stigma of a flower (in flowering plants) or at the ovule (in gymnosperms). There are two types of self-pollination: in autogamy, pollen is transferred to ...

. In Florida, individual ''F. aurea'' trees flower and fruit asynchronously. Within-tree asynchrony in flowering is likely to raise the probability of self-pollination, but it may be an adaptation that allows the species to maintain an adequate population of wasps at low population densities or in strongly seasonal climates.

Flowering phenology

Phenology is the study of periodic events in biological life cycles and how these are influenced by seasonal and interannual variations in climate, as well as habitat factors (such as elevation).

Examples include the date of emergence of leaves ...

in ''Ficus'' has been characterised into five phases. In most figs, phase A is followed almost immediately by phase B. However, in ''F. aurea'' immature inflorescences can remain dormant for more than nine months.

Growth

''Ficus aurea'' is a fast-growing tree. As ahemiepiphyte

A hemiepiphyte is a plant that spends part of its life cycle as an epiphyte

An epiphyte is an organism that grows on the surface of a plant and derives its moisture and nutrients from the air, rain, water (in marine environments) or from debr ...

it germinates in the canopy

Canopy may refer to:

Plants

* Canopy (biology), aboveground portion of plant community or crop (including forests)

* Canopy (grape), aboveground portion of grapes

Religion and ceremonies

* Baldachin or canopy of state, typically placed over an a ...

of a host tree and begins life as an epiphyte

An epiphyte is an organism that grows on the surface of a plant and derives its moisture and nutrients from the air, rain, water (in marine environments) or from debris accumulating around it. The plants on which epiphytes grow are called phoroph ...

before growing roots down to the ground. ''F. aurea'' is also a strangler fig

Strangler fig is the common name for a number of tropical and subtropical plant species in the genus ''Ficus'', including those that are commonly known as banyans. Some of the more well-known species are:

* '' Ficus altissima''

* '' Ficus aurea'' ...

(not all hemiepiphytic figs are stranglers)—the roots fuse and encircle the host tree. This usually results in the death of the host, since it effectively girdles the tree. Palms, which lack secondary growth

In botany, secondary growth is the growth that results from cell division in the cambia or lateral meristems and that causes the stems and roots to thicken, while primary growth is growth that occurs as a result of cell division at the tips ...

, are not affected by this, but they can still be harmed by competition for light, water and nutrients. Following Hurricane Andrew

Hurricane Andrew was a very powerful and destructive Category 5 Atlantic hurricane that struck the Bahamas, Florida, and Louisiana in August 1992. It is the most destructive hurricane to ever hit Florida in terms of structures damaged ...

in 1992, ''F. aurea'' trees regenerated from root suckers and standing trees.

Distribution

''Ficus aurea'' ranges from Florida, across the northern Caribbean to Mexico, and south across Central America. It is present in central and southern Florida and theFlorida Keys

The Florida Keys are a coral cay archipelago located off the southern coast of Florida, forming the southernmost part of the continental United States. They begin at the southeastern coast of the Florida peninsula, about south of Miami, and ...

, The Bahamas, the Caicos Islands, Hispaniola, Cuba, Jamaica, the Cayman Islands, San Andrés (a Colombian possession in the western Caribbean), southern Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Costa Rica and Panama.Ficus aurea Nutt.Flora Mesoamericana: Lista Anotada. Retrieved on 2008-07-02 It grows from sea level up to 1,800 m (5,500 ft)

above sea level

Height above mean sea level is a measure of the vertical distance (height, elevation or altitude) of a location in reference to a historic mean sea level taken as a vertical datum. In geodesy, it is formalized as ''orthometric heights''.

The comb ...

, in habitats ranging from Bahamian dry forests, to cloud forest

A cloud forest, also called a water forest, primas forest, or tropical montane cloud forest (TMCF), is a generally tropical or subtropical, evergreen, montane, moist forest characterized by a persistent, frequent or seasonal low-level clou ...

in Costa Rica.

''Ficus aurea'' is found in central and southern Florida as far north as Volusia County

Volusia County (, ) is located in the east-central part of the U.S. state of Florida, stretching between the St. Johns River and the Atlantic Ocean. As of the 2020 census, the county was home to 553,543 people, an increase of 11.9% from the ...

; it is one of only two native fig species in Florida. The species is present in a range of south Florida ecosystems, including coastal hardwood hammocks, cabbage palm hammocks,

tropical hardwood hammocks and shrublands, temperate hardwood hammocks and shrublands and along watercourses. In The Bahamas, ''F. aurea'' is found in tropical dry forests on North Andros, Great Exuma

Exuma is a district of The Bahamas, consisting of over 365 islands, also called cays.

The largest of the cays is Great Exuma, which is 37 mi (60 km) in length and joined to another island, Little Exuma, by a small bridge. The capital ...

and Bimini

Bimini is the westernmost district of the Bahamas and comprises a chain of islands located about due east of Miami. Bimini is the closest point in the Bahamas to the mainland United States and approximately west-northwest of Nassau. The popula ...

. ''F. aurea'' occurs in 10 states in Mexico, primarily in the south, but extending as far north as Jalisco

Jalisco (, , ; Nahuatl: Xalixco), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Jalisco ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Jalisco ; Nahuatl: Tlahtohcayotl Xalixco), is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Federal En ...

. It is found in tropical deciduous forest, tropical semi-evergreen forest, tropical evergreen forest, cloud forest and in aquatic or subaquatic habitats.

Ecology

''Ficus aurea'' is a strangler fig—it tends to establish on a host tree which it gradually encircles and "strangles", eventually taking the place of that tree in the forest canopy. While this makes ''F. aurea'' an agent in the mortality of other trees, there is little to indicate that its choice of hosts is species specific. However, in

''Ficus aurea'' is a strangler fig—it tends to establish on a host tree which it gradually encircles and "strangles", eventually taking the place of that tree in the forest canopy. While this makes ''F. aurea'' an agent in the mortality of other trees, there is little to indicate that its choice of hosts is species specific. However, in dry forests

The tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forest is a habitat type defined by the World Wide Fund for Nature and is located at tropical and subtropical latitudes. Though these forests occur in climates that are warm year-round, and may receive ...

on Great Exuma

Exuma is a district of The Bahamas, consisting of over 365 islands, also called cays.

The largest of the cays is Great Exuma, which is 37 mi (60 km) in length and joined to another island, Little Exuma, by a small bridge. The capital ...

in The Bahamas, ''F. aurea'' establishes exclusively on palms, in spite of the presence of several other large trees that should provide suitable hosts. Eric Swagel and colleagues attributed this to the fact that humus

In classical soil science, humus is the dark organic matter in soil that is formed by the decomposition of plant and animal matter. It is a kind of soil organic matter. It is rich in nutrients and retains moisture in the soil. Humus is the Latin ...

accumulates on the leaf bases of these palms and provides a relatively moist microclimate

A microclimate (or micro-climate) is a local set of atmospheric conditions that differ from those in the surrounding areas, often with a slight difference but sometimes with a substantial one. The term may refer to areas as small as a few squa ...

in a dry environment, facilitating seedling survival.

Figs are sometimes considered to be potential keystone species

A keystone species is a species which has a disproportionately large effect on its natural environment relative to its abundance, a concept introduced in 1969 by the zoologist Robert T. Paine. Keystone species play a critical role in maintain ...

in communities of fruit-eating animals because of their asynchronous

Asynchrony is the state of not being in synchronization.

Asynchrony or asynchronous may refer to:

Electronics and computing

* Asynchrony (computer programming), the occurrence of events independent of the main program flow, and ways to deal with ...

fruiting patterns. Nathaniel Wheelwright reports that emerald toucanets fed on unripe ''F. aurea'' fruit at times of fruit scarcity in Monteverde

Monteverde is the twelfth canton of the Puntarenas province of Costa Rica. It is located in the Cordillera de Tilarán mountain range. Roughly a four-hour drive from the Central Valley, Monteverde is one of the country's major ecotourism de ...

, Costa Rica

Costa Rica (, ; ; literally "Rich Coast"), officially the Republic of Costa Rica ( es, República de Costa Rica), is a country in the Central American region of North America, bordered by Nicaragua to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the ...

. Wheelwright listed the species as a year-round food source for the resplendent quetzal

The resplendent quetzal (''Pharomachrus mocinno'') is a small bird found in southern Mexico and Central America, with two recognized subspecies, ''P. m. mocinno'' and ''P. m. costaricensis''. These animals live in tropical forests, particularly ...

at the same site. In the Florida Keys

The Florida Keys are a coral cay archipelago located off the southern coast of Florida, forming the southernmost part of the continental United States. They begin at the southeastern coast of the Florida peninsula, about south of Miami, and ...

, ''F. aurea'' is one of five fruit species that dominate the diet fed by white-crowned pigeons to their nestlings. ''F. aurea'' is also important in the diet of mammalian frugivores—both fruit and young leaves are consumed by black howler monkeys in Belize.

The interaction between figs and fig wasp

Fig wasps are wasps of the superfamily Chalcidoidea which spend their larval stage inside figs. Most are pollinators but others simply feed off the plant. The non-pollinators belong to several groups within the superfamily Chalcidoidea, while the ...

s is especially well-known (see section on reproduction

Reproduction (or procreation or breeding) is the biological process by which new individual organisms – " offspring" – are produced from their "parent" or parents. Reproduction is a fundamental feature of all known life; each individual o ...

, above). In addition to its pollinators (''Pegoscapus mexicanus''), ''F. aurea'' is exploited by a group of non-pollinating chalcidoid wasps whose larvae develop in its figs. These include gall

Galls (from the Latin , 'oak-apple') or ''cecidia'' (from the Greek , anything gushing out) are a kind of swelling growth on the external tissues of plants, fungi, or animals. Plant galls are abnormal outgrowths of plant tissues, similar to be ...

ers, inquiline

In zoology, an inquiline (from Latin ''inquilinus'', "lodger" or "tenant") is an animal that lives commensally in the nest, burrow, or dwelling place of an animal of another species. For example, some organisms such as insects may live in the h ...

s and kleptoparasite

Kleptoparasitism (etymologically, parasitism by theft) is a form of feeding in which one animal deliberately takes food from another. The strategy is evolutionarily stable when stealing is less costly than direct feeding, which can mean when foo ...

s as well as parasitoid

In evolutionary ecology, a parasitoid is an organism that lives in close association with its host (biology), host at the host's expense, eventually resulting in the death of the host. Parasitoidism is one of six major evolutionarily stable str ...

s of both the pollinating and non-pollinating wasps.

The invertebrates within ''F. aurea'' syconia in southern Florida include a pollinating wasp, ''P. mexicanus'', up to eight or more species of non-pollinating wasps, a plant-parasitic nematode transported by the pollinator, mites, and a predatory rove beetle whose adults and larvae eat fig wasps.

Nematodes: ''Schistonchus aureus'' (Aphelenchoididae) is a plant-parasitic nematode associated with the pollinator ''Pegoscapus mexicanus'' and syconia of ''F. aurea''.

Mites: belonging to the family Tarsonemidae (Acarina) have been recognized in the syconia of ''F. aurea'' and ''F. citrifolia'', but they have not been identified even to genus, and their behavior is undescribed.

Rove beetles: ''Charoxus spinifer'' is a rove beetle (Coleoptera: Staphylinidae) whose adults enter late-stage syconia of ''F. aurea'' and ''F. citrifolia''. Adults eat fig wasps; larvae develop within the syconia and prey on fig wasps, then pupate in the ground.

As a large tree, ''F. aurea'' can be an important host for epiphyte

An epiphyte is an organism that grows on the surface of a plant and derives its moisture and nutrients from the air, rain, water (in marine environments) or from debris accumulating around it. The plants on which epiphytes grow are called phoroph ...

s. In Costa Rican cloud forests, where ''F. aurea'' is "the most conspicuous component" of intact forest, trees in forest patches supported richer communities of epiphytic bryophyte

The Bryophyta s.l. are a proposed taxonomic division containing three groups of non-vascular land plants (embryophytes): the liverworts, hornworts and mosses. Bryophyta s.s. consists of the mosses only. They are characteristically limited in s ...

s, while isolated trees supported greater lichen

A lichen ( , ) is a composite organism that arises from algae or cyanobacteria living among filaments of multiple fungi species in a mutualistic relationship.Florida International University

Florida International University (FIU) is a public research university with its main campus in Miami-Dade County. Founded in 1965, the school opened its doors to students in 1972. FIU has grown to become the third-largest university in Florida ...

ecologist Suzanne Koptur reported the presence of extrafloral nectaries on ''F. aurea'' figs in the Florida Everglades

The Everglades is a natural region of tropical wetlands in the southern portion of the U.S. state of Florida, comprising the southern half of a large drainage basin within the Neotropical realm. The system begins near Orlando with the Kissimm ...

. Extrafloral nectaries are structures which produce nectar

Nectar is a sugar-rich liquid produced by plants in glands called nectaries or nectarines, either within the flowers with which it attracts pollinating animals, or by extrafloral nectaries, which provide a nutrient source to animal mutualist ...

but are not associated with flowers. They are usually interpreted as defensive structure and are often produced in response to attack by insect herbivore

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically adapted to eating plant material, for example foliage or marine algae, for the main component of its diet. As a result of their plant diet, herbivorous animals typically have mouthp ...

s. They attract insects, primarily ants, which defend the nectaries, thus protecting the plant against herbivores.

Uses

''Ficus aurea'', amongst other related ''Ficus'' species, has been a source of bark for preparing ''amate

Amate ( es, amate from nah, āmatl ) is a type of bark paper that has been manufactured in Mexico since the precontact times. It was used primarily to create codices.

Amate paper was extensively produced and used for both communication, record ...

'', the bark paper used for codices

The codex (plural codices ) was the historical ancestor of the modern book. Instead of being composed of sheets of paper, it used sheets of vellum, papyrus, or other materials. The term ''codex'' is often used for ancient manuscript books, with ...

in the Mesoamerican civilizations. The oldest example dates back to 75 CE and was found in a shaft tomb culture site in Huitzilapa, Jalisco

Jalisco (, , ; Nahuatl: Xalixco), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Jalisco ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Jalisco ; Nahuatl: Tlahtohcayotl Xalixco), is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Federal En ...

in Mexico

Mexico ( Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Gua ...

.

The fruit of ''Ficus aurea'' is edible and was used for food by the Native Americans and early settlers in Florida; it is still eaten occasionally as a backyard source of native fruit. The latex was used to make a chewing gum, and aerial roots may have been used to make lashings, arrows, bowstrings and fishing lines. The fruit was used to make a rose-coloured dye. ''F. aurea'' was also used in traditional medicine

Traditional medicine (also known as indigenous medicine or folk medicine) comprises medical aspects of traditional knowledge that developed over generations within the folk beliefs of various societies, including indigenous peoples, before the ...

in The Bahamas and Florida. Allison Adonizio and colleagues screened ''F. aurea'' for anti-quorum sensing

In biology, quorum sensing or quorum signalling (QS) is the ability to detect and respond to cell population density by gene regulation. As one example, QS enables bacteria to restrict the expression of specific genes to the high cell densities a ...

activity (as a possible means of anti-bacterial action), but found no such activity.

Individual ''F. aurea'' trees are common on dairy farms in La Cruz, Cañitas and Santa Elena in Costa Rica, since they are often spared when forest is converted to pasture

Pasture (from the Latin ''pastus'', past participle of ''pascere'', "to feed") is land used for grazing. Pasture lands in the narrow sense are enclosed tracts of farmland, grazed by domesticated livestock, such as horses, cattle, sheep, or swin ...

. In interviews, farmers identified the species as useful for fence posts, live fencing and firewood, and as a food species for wild birds and mammals.

''Ficus aurea'' is used as an ornamental tree

Ornamental plants or garden plants are plants that are primarily grown for their beauty but also for qualities such as scent or how they shape physical space. Many flowering plants and garden varieties tend to be specially bred cultivars that i ...

, an indoor tree and as a bonsai

Bonsai ( ja, 盆栽, , tray planting, ) is the Japanese art of growing and training miniature trees in pots, developed from the traditional Chinese art form of ''penjing''. Unlike ''penjing'', which utilizes traditional techniques to produce ...

. Like other figs, it tends to invade built structures and foundations, and need to be removed to prevent structural damage. Although young trees are described as "rather ornamental", older trees are considered to be difficult to maintain (because of the adventitious roots Important structures in plant development are buds, shoots, roots, leaves, and flowers; plants produce these tissues and structures throughout their life from meristems located at the tips of organs, or between mature tissues. Thus, a living plant ...

that develop off branches) and are not recommended for small areas. However, it was considered a useful tree for "enviroscaping" to conserve energy in south Florida, since it is "not as aggressive as many exotic fig species," although it must be given enough space.

References

External links

Interactive Distribution Map for Ficus aurea

{{Taxonbar, from=Q2561277 aurea Trees of the Caribbean Trees of Central America Flora of Florida Trees of Mexico Plants described in 1846 Taxa named by Thomas Nuttall Epiphytes Garden plants of North America Plants used in bonsai Ornamental trees Flora without expected TNC conservation status