Far right in the United Kingdom on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Far-right politics in the United Kingdom have existed since at least the 1930s, with the formation of

John Tyndall formed the New National Front in 1980, and changed its name to the

John Tyndall formed the New National Front in 1980, and changed its name to the

documentary led to Griffin being charged with Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

, fascist and anti-semitic movements. It went on to acquire more explicitly racial connotations, being dominated in the 1960s and 1970s by self-proclaimed white nationalist

White nationalism is a type of racial nationalism or pan-nationalism which espouses the belief that white people are a raceHeidi Beirich and Kevin Hicks. "Chapter 7: White nationalism in America". In Perry, Barbara. ''Hate Crimes''. Greenwoo ...

organisations that opposed non-white and Asian

Asian may refer to:

* Items from or related to the continent of Asia:

** Asian people, people in or descending from Asia

** Asian culture, the culture of the people from Asia

** Asian cuisine, food based on the style of food of the people from Asi ...

immigration, such as the National Front (NF), the British Movement (BM) and British National Party

The British National Party (BNP) is a far-right, fascist political party in the United Kingdom. It is headquartered in Wigton, Cumbria, and its leader is Adam Walker. A minor party, it has no elected representatives at any level of UK gover ...

(BNP), or the British Union of Fascists (BUF). Since the 1980s, the term has mainly been used to describe those groups, such as the English Defence League

The English Defence League (EDL) is a far-right, Islamophobic organisation in the United Kingdom. A social movement and pressure group that employs street demonstrations as its main tactic, the EDL presents itself as a single-issue movement ...

, who express the wish to preserve what they perceive to be British culture, and those who campaign against the presence of non-indigenous ethnic minorities

The term 'minority group' has different usages depending on the context. According to its common usage, a minority group can simply be understood in terms of demographic sizes within a population: i.e. a group in society with the least number o ...

and what they perceive to be an excessive number of asylum seekers.

The NF and the BNP have been strongly opposed to non-white immigration

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not natives or where they do not possess citizenship in order to settle as permanent residents or naturalized citizens. Commuters, tourists, a ...

. They have encouraged the repatriation of ethnic minorities: the NF favours compulsory repatriation, while the BNP favours voluntary repatriation. The BNP have had a number of local councillors in some inner-city areas of East London, and towns in Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other English counties, functions have ...

and Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancash ...

, such as Burnley

Burnley () is a town and the administrative centre of the wider Borough of Burnley in Lancashire, England, with a 2001 population of 73,021. It is north of Manchester and east of Preston, Lancashire, Preston, at the confluence of the River C ...

and Keighley

Keighley ( ) is a market town and a civil parish

in the City of Bradford Borough of West Yorkshire, England. It is the second largest settlement in the borough, after Bradford.

Keighley is north-west of Bradford city centre, north-west of ...

. East London has been the bedrock of far-right support in the UK since the 1930s, whereas BNP success in the north of England is a newer phenomenon. The only other part of the country to provide any significant level of support for such views is the West Midlands

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some ...

.

History

1930s to 1960s

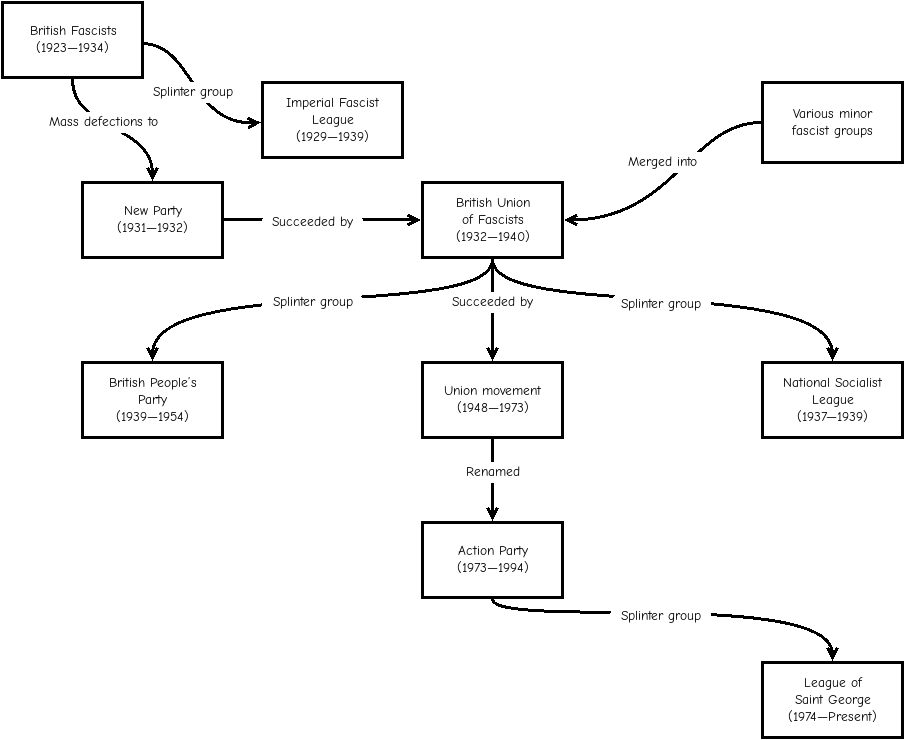

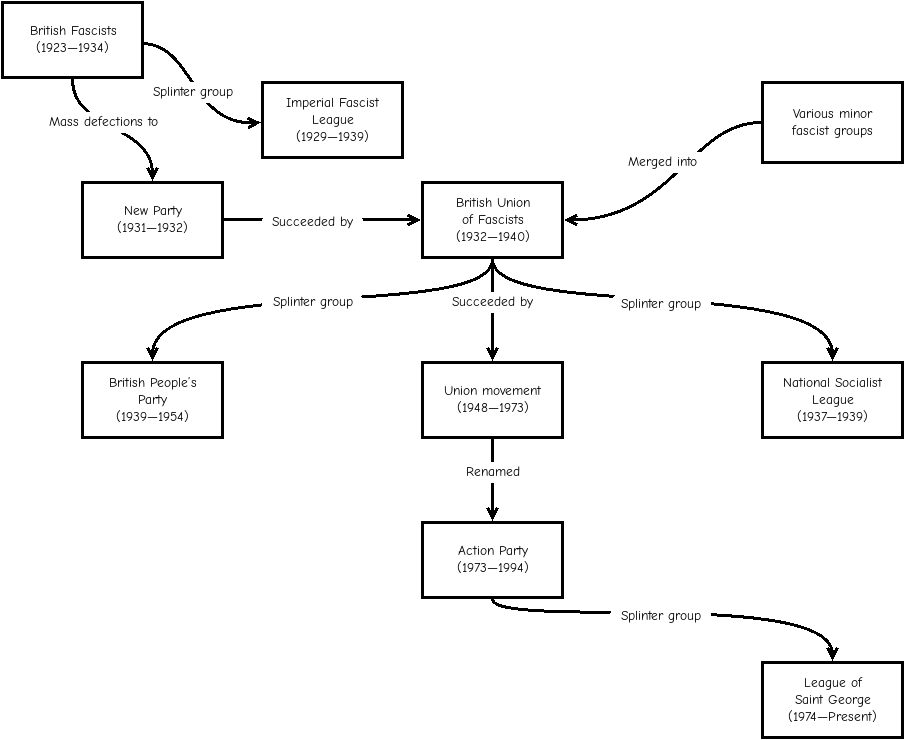

The British far right rose out of the fascist movement. In 1932,Oswald Mosley

Sir Oswald Ernald Mosley, 6th Baronet (16 November 1896 – 3 December 1980) was a British politician during the 1920s and 1930s who rose to fame when, having become disillusioned with mainstream politics, he turned to fascism. He was a member ...

founded the British Union of Fascists (BUF), which was banned during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. Founded in 1954 by A. K. Chesterton

Arthur Kenneth Chesterton (1 May 1899 – 16 August 1973) was a British far-right journalist and political activist. From 1933 to 1938, he was a member of the British Union of Fascists (BUF). Disillusioned with Oswald Mosley, he left th ...

, the League of Empire Loyalists

The League of Empire Loyalists (LEL) was a British pressure group (also called a "ginger group" in Britain and the Commonwealth of Nations), established in 1954. Its ostensible purpose was to stop the dissolution of the British Empire. The League ...

became the main British far right group at the time. It was a pressure group rather than a political party, and did not contest elections. Most of its members were part of the Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

, and they were known for politically embarrassing stunts at party conferences. Its more extreme elements wanted to make the group more political, which led to a number of splinter groups forming, including the White Defence League

The White Defence League (WDL) was a British neo-Nazi political party. Using the provocative marching techniques popularised by Oswald Mosley, its members included John Tyndall.

Formation

The WDL had its roots in Colin Jordan's decision to sp ...

and the National Labour Party. These both stood in local elections in 1958, and merged in 1960 to form the British National Party

The British National Party (BNP) is a far-right, fascist political party in the United Kingdom. It is headquartered in Wigton, Cumbria, and its leader is Adam Walker. A minor party, it has no elected representatives at any level of UK gover ...

(BNP).

With the decline of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

becoming inevitable, British far-right parties turned their attention to internal matters. The 1950s had seen an increase in immigration to the UK from its former colonies, particularly India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 243 million people, and has the world's second-lar ...

, the Caribbean and Uganda

}), is a landlocked country in East Africa. The country is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the south by Tanzania. The sou ...

. Led by John Bean

John Bean may refer to:

* John Bean (cricketer) (1913–2005), English cricketer and British Army officer

* John Bean (politician) (1927–2021), long-standing participant in the British far right

* John Bean (explorer) ( 1751–1757), Canadian e ...

and Andrew Fountaine, the BNP opposed the admittance of these people to the UK. A number of its rallies, such as one in 1962 in Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square ( ) is a public square in the City of Westminster, Central London, laid out in the early 19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. At its centre is a high column bearing a statue of Admiral Nelson comm ...

, London, ended in race riots. After a few early successes, the party got into difficulties and was destroyed by internal arguments. In 1967 it joined forces with John Tyndall and the remnants of Chesterton's League of Empire Loyalists to form the National Front (NF).

The Conservative Monday Club

The Conservative Monday Club (usually known as the Monday Club) is a British political pressure group, aligned with the Conservative Party, though no longer endorsed by it. It also has links to the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and Ulster Unioni ...

, a far-right group within the Conservative Party, was formed in 1961. Its stated aim was "to safeguard the liberty of the subject and integrity of the family in accordance with the customs, traditions, and character of the British people". They expressed general opposition to post-colonial states and immigration, as well as support for hard-line loyalism in Northern Ireland.

1970s to 1990s

The NF quickly grew to be the biggest British far right party in the UK. It polled 44% in a local election in Deptford, London, and finished third in threeby-election

A by-election, also known as a special election in the United States and the Philippines, a bye-election in Ireland, a bypoll in India, or a Zimni election (Urdu: ضمنی انتخاب, supplementary election) in Pakistan, is an election used to f ...

s, although these results were atypical of the country as a whole. The party supported extreme loyalism

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British C ...

in Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

, and attracted Conservative Party members who had become disillusioned after Harold Macmillan had recognised the right to independence of the Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

n colonies, and had criticised Apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

in South Africa. During the 1970s, the NF's rallies became a regular feature of British politics. Election results remained strong in a few working class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colo ...

urban areas, with a number of local council seats won, but the party never came anywhere near winning representation in parliament.

The smaller far right groups maintained anti-immigration policies, but there was a move towards a more inclusionist vision of the UK, and a focus on opposing what became the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been de ...

. The NF began to support non-white radicals such as Louis Farrakhan

Louis Farrakhan (; born Louis Eugene Walcott, May 11, 1933) is an American religious leader, Black supremacy, black supremacist, Racism, anti-white and Antisemitism, antisemitic Conspiracy theory, conspiracy theorist, and former singer who hea ...

. This led to the splintering of the various groups, with radical political soldiers such as a young Nick Griffin

Nicholas John Griffin (born 1 March 1959) is a British politician and white supremacist who represented North West England as a Member of the European Parliament (MEP) from 2009 to 2014. He served as chairman and then president of the far-righ ...

forming the Third Way

The Third Way is a centrist political position that attempts to reconcile right-wing and left-wing politics by advocating a varying synthesis of centre-right economic policies with centre-left social policies. The Third Way was born from ...

group, and traditionalists creating the Flag Group

The Flag Group was a British far-right political party, formed from one of the two wings of the National Front in the 1980s. Formed in opposition to the Political Soldier wing of the Official National Front, it took its name from ''The Flag'', a ...

.

Membership of the Monday Club

The Conservative Monday Club (usually known as the Monday Club) is a British political pressure group, aligned with the Conservative Party, though no longer endorsed by it. It also has links to the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and Ulster Unioni ...

meanwhile, who gave strong support to Apartheid in South Africa

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

and to Ian Smith's illegal declaration of independence in Rhodesia, fell to under 600 by 1987.

John Tyndall formed the New National Front in 1980, and changed its name to the

John Tyndall formed the New National Front in 1980, and changed its name to the British National Party

The British National Party (BNP) is a far-right, fascist political party in the United Kingdom. It is headquartered in Wigton, Cumbria, and its leader is Adam Walker. A minor party, it has no elected representatives at any level of UK gover ...

(BNP) in 1982. They, alongside the Conservative Monday Club, campaigned against the increasing integration of the UK into the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been de ...

. However, Tyndall's reputation of a 'brutal, street fighting background' and his admiration for Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

and the Nazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in N ...

prevented the party from gaining any respectability. They developed a policy of eschewing the traditional far right methods of extra-parliamentary movements, and concentrated instead on the ballot box. Nick Griffin

Nicholas John Griffin (born 1 March 1959) is a British politician and white supremacist who represented North West England as a Member of the European Parliament (MEP) from 2009 to 2014. He served as chairman and then president of the far-righ ...

replaced Tyndall as BNP leader in 1999 and introduced several policies to make the party more electable. Repatriation of ethnic minorities was made voluntary and several other policies were moderated.

2000s

The National Front continued to decline, whilst Nick Griffin and the BNP grew in popularity. Around the turn of the 21st century, the BNP won a number of councillor seats. They continued their anti-immigration policy, and a damagingBBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...incitement to racial hatred

Incitement to ethnic or racial hatred is a crime under the laws of several countries.

Australia

In Australia, the Racial Hatred Act 1995 amends the Racial Discrimination Act 1975, inserting Part IIA – Offensive Behaviour Because of Race, Colour ...

(although he was acquitted). The 2006 local elections brought the BNP the most successful results of any far right party in British history. They gained 33 council seats, the second highest gain of any party at the elections; in Barking and Dagenham

The London Borough of Barking and Dagenham () is a London borough in East London. It lies around 9 miles (14.4 km) east of Central London. It is an Outer London borough and the south is within the London Riverside section of the Thames Ga ...

, they gained 12 councillor seats.

In the 2008 local elections, the party won a record 100 councillor seats, and a seat on the Greater London Assembly, which would prove the party's high water mark. At the June 2009 European Parliament Election, the BNP gained two Members of the European Parliament for Yorkshire and the Humber

Yorkshire and the Humber is one of nine official regions of England at the first level of ITL for statistical purposes. The population in 2011 was 5,284,000 with its largest settlements being Leeds, Sheffield, Bradford, Hull, and York.

It is ...

and North West England. In October 2009, BNP leader Nick Griffin was allowed on the BBC topical debate show ''Question Time

A question time in a parliament occurs when members of the parliament ask questions of government ministers (including the prime minister), which they are obliged to answer. It usually occurs daily while parliament is sitting, though it can be ca ...

''. His appearance caused much controversy and the show was watched by over 8 million people.

Current (2010–)

At the 2010 general election, the BNP fielded 338 candidates across England, Scotland and Wales and won 563,743 votes (1.9% of total) but no seats.Nick Griffin

Nicholas John Griffin (born 1 March 1959) is a British politician and white supremacist who represented North West England as a Member of the European Parliament (MEP) from 2009 to 2014. He served as chairman and then president of the far-righ ...

subsequently said he would resign as BNP leader in 2013, and was eventually expelled from the party in 2014 as the BNP fell into obscurity. The National Front fielded 17 candidates at the 2010 Election and received 10,784 votes.

The anti-Islamist group, the English Defence League

The English Defence League (EDL) is a far-right, Islamophobic organisation in the United Kingdom. A social movement and pressure group that employs street demonstrations as its main tactic, the EDL presents itself as a single-issue movement ...

(EDL), started to rise in popularity, appealing to nationalist sentiments on a cultural rather than explicitly racial basis. Originally formed in Luton

Luton () is a town and unitary authority with borough status, in Bedfordshire, England. At the 2011 census, the Luton built-up area subdivision had a population of 211,228 and its built-up area, including the adjacent towns of Dunstable a ...

in 2009, it protests against what it considers the Islamification of Britain by organising demonstrations in towns and cities across England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, the largest of which occurred in Luton in February 2011. Soon after, right-wing populist

Right-wing populism, also called national populism and right-wing nationalism, is a political ideology that combines right-wing politics and populist rhetoric and themes. Its rhetoric employs anti- elitist sentiments, opposition to the Establ ...

party UK Independence Party

The UK Independence Party (UKIP; ) is a Eurosceptic, right-wing populist political party in the United Kingdom. The party reached its greatest level of success in the mid-2010s, when it gained two members of Parliament and was the largest par ...

(UKIP) started to gain popularity. Although labelled as far-right by some political observers, UKIP was not universally considered so. UKIP and the EDL benefited over this period from a rightward shift in the electorate, while former far-right parties such as the BNP and National Front became fringe groups and wield very little media attention or power.

In 2010, Robin Tilbrook, the chairman of the English nationalist

English nationalism is a nationalism that asserts that the English are a nation and promotes the cultural unity of English people. In a general sense, it comprises political and social movements and sentiment inspired by a love for English c ...

party the English Democrats

The English Democrats is a right-wing to far-right, English nationalist political party active in England. A minor party, it currently has no elected representatives at any level of UK government.

The English Democrats were established in 20 ...

, met with Sergey Yerzunov, a member of the executive committee of the Russian nationalist group Russky Obraz. Shortly afterwards, Obraz announced that they were in alliance with the English Democrats. Other members of this alliance include Serbian Obraz, 1389 Movement, Golden Dawn, Danes' Party, Slovenska Pospolitost, Workers' Party and Noua Dreaptă

''Noua Dreaptă'' ( en, The New Right) is an ultranationalist, far-right organization in Romania and Moldova, founded in 2000. The party claims to be the successor to the far-right Iron Guard, with its aesthetics and ideology being directly i ...

. Since 2010, a number of former members of the BNP have joined the English Democrats, with the party chairman quoted as saying, "They will help us become an electorally credible party." In an April 2013 interview, Tilbrook said that about 200–300 out of the party's membership of 3,000 were former BNP members. He said it was "perfectly fair" that such people would "change their minds" and join a "moderate, sensible English nationalist party".

In 2011, the far-right, anti-Islamist party Britain First

Britain First is a far-right, British fascist political party formed in 2011 by former members of the British National Party (BNP). The group was founded by Jim Dowson, an anti-abortion and far-right campaigner.

* ''See also'': The organ ...

was formed by former members of the BNP. Britain First campaigns primarily against immigration

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not natives or where they do not possess citizenship in order to settle as permanent residents or naturalized citizens. Commuters, tourists, a ...

, multiculturalism

The term multiculturalism has a range of meanings within the contexts of sociology, political philosophy, and colloquial use. In sociology and in everyday usage, it is a synonym for " ethnic pluralism", with the two terms often used interchang ...

and what it sees as the Islamisation of the United Kingdom, and advocates the preservation of traditional British culture. The group is inspired by Ulster loyalism

Ulster loyalism is a strand of Ulster unionism associated with working class Ulster Protestants in Northern Ireland. Like other unionists, loyalists support the continued existence of Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom, and oppose a u ...

and has a vigilante

Vigilantism () is the act of preventing, investigating and punishing perceived offenses and crimes without legal authority.

A vigilante (from Spanish, Italian and Portuguese “vigilante”, which means "sentinel" or "watcher") is a person who ...

wing called the "Britain First Defence Force". It attracted attention by taking direct action such as protests outside homes of alleged Islamists, and what it describes as " Christian patrols" and "invasions" of British mosques, and has been noted for its online activism

Internet activism is the use of electronic communication technologies such as social media, e-mail, and podcasts for various forms of activism to enable faster and more effective communication by citizen movements, the delivery of particular infor ...

. Its leader Paul Golding

upGolding at a Britain First rally in 2019

Paul Golding (born January 1982) is a British far-right political leader who is currently the leader of Britain First.

In December 2016, Golding was sentenced to eight weeks imprisonment for breaching ...

stood as a candidate in the 2016 London mayoral election

The 2016 London mayoral election was held on 5 May 2016 to elect the Mayor of London, on the same day as the London Assembly election. It was the fifth election to the position of mayor, which was created in 2000 after a referendum in Greate ...

, receiving 31,372 or 1.2% of the vote, coming eighth of twelve candidates. Golding was jailed for eight weeks in December 2016 for breaking a court order banning him from entering mosques or encouraging others to do so.

In February 2013, the British Democratic Party

The British Democratic Party (BDP) was a short-lived far-right political party in the United Kingdom. A breakaway group from the National Front, the BDP was severely damaged after it became involved in a gun-running sting and was absorbed by the ...

was launched by former Member of the European Parliament

A Member of the European Parliament (MEP) is a person who has been elected to serve as a popular representative in the European Parliament.

When the European Parliament (then known as the Common Assembly of the ECSC) first met in 1952, its ...

(MEP) and National Front chairman Andrew Brons

Andrew Henry William Brons (born 3 June 1947) is a British politician and former MEP. Long active in far-right politics in Britain, he was elected as a Member of the European Parliament (MEP) for Yorkshire and the Humber for the British National ...

, who resigned from the BNP in October 2012 after narrowly failing in his campaign to unseat Nick Griffin

Nicholas John Griffin (born 1 March 1959) is a British politician and white supremacist who represented North West England as a Member of the European Parliament (MEP) from 2009 to 2014. He served as chairman and then president of the far-righ ...

as leader of the BNP in 2011. Brons remains the party's inaugural president, and the chairman is James Lewthwaite. The BDP has attracted former members of the British National Party

The British National Party (BNP) is a far-right, fascist political party in the United Kingdom. It is headquartered in Wigton, Cumbria, and its leader is Adam Walker. A minor party, it has no elected representatives at any level of UK gover ...

(BNP), Democratic Nationalists, Freedom Party, UK Independence Party

The UK Independence Party (UKIP; ) is a Eurosceptic, right-wing populist political party in the United Kingdom. The party reached its greatest level of success in the mid-2010s, when it gained two members of Parliament and was the largest par ...

(UKIP), For Britain Movement

The For Britain Movement was a minor far-right political party in the United Kingdom, founded by the anti-Islam and "counter-jihad" activist Anne Marie Waters after she was defeated in the 2017 UK Independence Party leadership election.

Hi ...

, and Civil Liberty

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties ma ...

, including long-standing far-right political leader John Bean

John Bean may refer to:

* John Bean (cricketer) (1913–2005), English cricketer and British Army officer

* John Bean (politician) (1927–2021), long-standing participant in the British far right

* John Bean (explorer) ( 1751–1757), Canadian e ...

. Nick Lowles of Hope not Hate

Hope not Hate (stylized as HOPE not hate) is an advocacy group based in the United Kingdom which campaigns against racism and fascism. It has also mounted campaigns against Islamic extremism and antisemitism. It is self-described as a "non-par ...

believed the party would be a serious threat to the BNP, commenting "The BDP brings together all of the hardcore Holocaust deniers

Holocaust denial is an antisemitic conspiracy theory that falsely asserts that the Nazi genocide of Jews, known as the Holocaust, is a myth, fabrication, or exaggeration. Holocaust deniers make one or more of the following false statements:

* ...

and racists that have walked away from the BNP over the last two to three years, plus those previously, who could not stomach the party’s image changes". And in 2022 the BDP experienced a sharp increase in membership, with several nationalist local councillors and prominent far-right activists like Derek Beackon

Derek William Beackon is a British far-right politician. He is currently a member of the British Democratic Party (BDP), and a former member of the British National Party (BNP) and National Front. In 1993, he became the BNP's first elected coun ...

joining the party. They are currently the only far-right British political party to have any elected representation, with 4 local councillors.

In June 2016, Jo Cox was murdered by a far-right extremist after being stoked by the campaigns surrounding the Brexit

Brexit (; a portmanteau of "British exit") was the withdrawal of the United Kingdom (UK) from the European Union (EU) at 23:00 GMT on 31 January 2020 (00:00 1 February 2020 CET).The UK also left the European Atomic Energy Community (EAEC ...

referendum. Scholars have suggested that far-right attitudes contributed to and were normalised by the result of the Brexit referendum.

In December 2016, the neo-Nazi group National Action was proscribed as a terrorist organisation.

In October 2017, former UKIP

The UK Independence Party (UKIP; ) is a Eurosceptic, right-wing populist political party in the United Kingdom. The party reached its greatest level of success in the mid-2010s, when it gained two members of Parliament and was the largest p ...

leadership candidate and anti-islam activist Anne Marie Waters

Anne Marie Dorothy Waters (born 24 August 1977) is a far-right politician and activist in the United Kingdom. She founded and led the anti-Islam party For Britain until its dissolution in 2022. She is also the director of Sharia Watch UK, an or ...

launched the For Britain Movement

The For Britain Movement was a minor far-right political party in the United Kingdom, founded by the anti-Islam and "counter-jihad" activist Anne Marie Waters after she was defeated in the 2017 UK Independence Party leadership election.

Hi ...

. Unlike most far-right parties that came before them, For Britain were zionist

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after '' Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Je ...

, opposed to anti-semitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

, and held more moderate views on social issues like LGBT rights

Rights affecting lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender ( LGBT) people vary greatly by country or jurisdiction—encompassing everything from the legal recognition of same-sex marriage to the death penalty for homosexuality.

Notably, ...

. Former English Defence League

The English Defence League (EDL) is a far-right, Islamophobic organisation in the United Kingdom. A social movement and pressure group that employs street demonstrations as its main tactic, the EDL presents itself as a single-issue movement ...

leader Tommy Robinson and singer-songwriter Morrissey announced their support for the party, and fellow far-right and counter-jihad

Counter-jihad, also spelled counterjihad and known as the counter-jihad movement, is a self-titled political current loosely consisting of authors, bloggers, think tanks, street movements and campaign organisations all linked by apocalyptic bel ...

political party Liberty GB merged with For Britain. The party received support from several former members of far-right groups like the British National Party

The British National Party (BNP) is a far-right, fascist political party in the United Kingdom. It is headquartered in Wigton, Cumbria, and its leader is Adam Walker. A minor party, it has no elected representatives at any level of UK gover ...

, Generation Identity

A generation refers to all of the people born and living at about the same time, regarded collectively. It can also be described as, "the average period, generally considered to be about 20–30 years, during which children are born and gr ...

, and the neo-Nazi terrorist organisation National Action. For Britain had some limited success in local council elections, but failed to make any significant breakthroughs in the parliamentary by-elections they contested. In July 2022, Waters announced on the party's website that the party was ceasing all operations with immediate effect, with their elected councillors subsequently joining the British Democrats.

In March 2018 Mark Rowley

Sir Mark Peter Rowley (born November 1964) is a British senior police officer who has been the Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis since September 2022.

He was the Assistant Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis for Specialist Operati ...

, the outgoing head of UK counter-terror policing, revealed that four far-right terror plots had been foiled since the Westminster attack in March 2017.

In November 2018 three people, Adam Thomas, Claudia Patatas and Daniel Bogunovic, were convicted of being members of the proscribed terrorist organisation, National Action, after a seven-week trial at the Crown Court in Birmingham. Thomas and Patatas have a child whom they named Adolf.

From 2018 to 2019, under the leadership of Gerard Batten

Gerard Joseph Batten (born 27 March 1954) is a British politician who served as the Leader of the UK Independence Party (UKIP) from 2018 to 2019. He was a founding member of the party in 1993, and served as a Member of the European Parliament ( ...

, UKIP

The UK Independence Party (UKIP; ) is a Eurosceptic, right-wing populist political party in the United Kingdom. The party reached its greatest level of success in the mid-2010s, when it gained two members of Parliament and was the largest p ...

was widely described as moving into far-right territory, at which point many longstanding members – including former leaders Nigel Farage

Nigel Paul Farage (; born 3 April 1964) is a British broadcaster and former politician who was Leader of the UK Independence Party (UKIP) from 2006 to 2009 and 2010 to 2016 and Leader of the Brexit Party (renamed Reform UK in 2021) from 2 ...

and Paul Nuttall

Paul Andrew Nuttall (born 30 November 1976) is a British politician who served as Leader of the UK Independence Party (UKIP) from 2016 to 2017. He was elected to the European Parliament in 2009 as a UK Independence Party (UKIP) candidate, and ...

– left. As the new permanent leader, Batten focused the party more on opposing Islam and sought closer relations with the far-right activist Stephen Yaxley-Lennon, otherwise Tommy Robinson, and his followers. Batten would leave the leadership of UKIP in 2019.

Since 2019 the former director of publicity of the BNP, neo-Nazi and anti-semitic conspiracy theorist Mark Collett has led a new far-right party called Patriotic Alternative.

In late 2020, The British Hand was founded by a 15 year old teenager. Since then the group have been at the root of far-right online propaganda, especially on the social media app Telegram

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

. This led Hope not Hate

Hope not Hate (stylized as HOPE not hate) is an advocacy group based in the United Kingdom which campaigns against racism and fascism. It has also mounted campaigns against Islamic extremism and antisemitism. It is self-described as a "non-par ...

to start an undercover investigation into the group and write an article exposing them.

Election results

See also

*List of British far-right groups since 1945

A ''list'' is any set of items in a row. List or lists may also refer to:

People

* List (surname)

Organizations

* List College, an undergraduate division of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America

* SC Germania List, German rugby unio ...

* Far-left politics in the United Kingdom

Far-left politics in the United Kingdom have existed since at least the 1840s, with the formation of various organisations following ideologies such as Marxism, revolutionary socialism, communism, anarchism and syndicalism.

Following the 1917 R ...

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Far-Right Politics In The United Kingdom Political movements in the United Kingdom Far-right politics in EuropeUnited Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

Right-wing politics in the United Kingdom