Frog Mascots on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A frog is any member of a diverse and largely

A frog is any member of a diverse and largely

The Anura include all modern frogs and any

The Anura include all modern frogs and any  Frogs and toads are broadly classified into three suborders: Archaeobatrachia, which includes four families of primitive frogs;

Frogs and toads are broadly classified into three suborders: Archaeobatrachia, which includes four families of primitive frogs;

In 2008, ''Gerobatrachus hottoni'', a Temnospondyli, temnospondyl with many frog- and salamander-like characteristics, was discovered in Texas. It dated back 290 million years and was hailed as a Transitional fossil, missing link, a Stem group, stem batrachian close to the common ancestor of frogs and salamanders, consistent with the widely accepted hypothesis that frogs and salamanders are more closely related to each other (forming a clade called Batrachia) than they are to caecilians. However, others have suggested that ''Gerobatrachus hottoni'' was only a Dissorophoidea, dissorophoid temnospondyl unrelated to extant amphibians.

Salientia (Latin ''salire'' (''salio''), "to jump") is the name of the total group that includes modern frogs in the order Anura as well as their close fossil relatives, the "proto-frogs" or "stem-frogs". The common features possessed by these proto-frogs include 14 Vertebral column, presacral vertebrae (modern frogs have eight or 9), a long and forward-sloping Ilium (bone), ilium in the pelvis, the presence of a Parietal bone, frontoparietal bone, and a lower jaw without teeth. The earliest known amphibians that were more closely related to frogs than to salamanders are ''Triadobatrachus massinoti'', from the early Triassic period of

In 2008, ''Gerobatrachus hottoni'', a Temnospondyli, temnospondyl with many frog- and salamander-like characteristics, was discovered in Texas. It dated back 290 million years and was hailed as a Transitional fossil, missing link, a Stem group, stem batrachian close to the common ancestor of frogs and salamanders, consistent with the widely accepted hypothesis that frogs and salamanders are more closely related to each other (forming a clade called Batrachia) than they are to caecilians. However, others have suggested that ''Gerobatrachus hottoni'' was only a Dissorophoidea, dissorophoid temnospondyl unrelated to extant amphibians.

Salientia (Latin ''salire'' (''salio''), "to jump") is the name of the total group that includes modern frogs in the order Anura as well as their close fossil relatives, the "proto-frogs" or "stem-frogs". The common features possessed by these proto-frogs include 14 Vertebral column, presacral vertebrae (modern frogs have eight or 9), a long and forward-sloping Ilium (bone), ilium in the pelvis, the presence of a Parietal bone, frontoparietal bone, and a lower jaw without teeth. The earliest known amphibians that were more closely related to frogs than to salamanders are ''Triadobatrachus massinoti'', from the early Triassic period of

Frogs have no tail, except as larvae, and most have long hind legs, elongated ankle bones, webbed toes, no claws, large eyes, and a smooth or warty skin. They have short vertebral columns, with no more than 10 free vertebrae and fused tailbones (urostyle or coccyx). Frogs range in size from ''Paedophryne amauensis'' of Papua New Guinea that is in snout–to–Cloaca, vent length to the up to and goliath frog (''Conraua goliath'') of central Africa. There are prehistoric, extinct species that reached even larger sizes.

Frogs have no tail, except as larvae, and most have long hind legs, elongated ankle bones, webbed toes, no claws, large eyes, and a smooth or warty skin. They have short vertebral columns, with no more than 10 free vertebrae and fused tailbones (urostyle or coccyx). Frogs range in size from ''Paedophryne amauensis'' of Papua New Guinea that is in snout–to–Cloaca, vent length to the up to and goliath frog (''Conraua goliath'') of central Africa. There are prehistoric, extinct species that reached even larger sizes.

The muscular system has been similarly modified. The hind limbs of ancestral frogs presumably contained pairs of muscles which would act in opposition (one muscle to flex the knee, a different muscle to extend it), as is seen in most other limbed animals. However, in modern frogs, almost all muscles have been modified to contribute to the action of jumping, with only a few small muscles remaining to bring the limb back to the starting position and maintain posture. The muscles have also been greatly enlarged, with the main leg muscles accounting for over 17% of the total mass of frogs.

Many frogs have webbed feet and the degree of webbing is directly proportional to the amount of time the species spends in the water. The completely aquatic African dwarf frog (''Hymenochirus'' sp.) has fully webbed toes, whereas those of White's tree frog (''Litoria caerulea''), an arboreal species, are only a quarter or half webbed. Exceptions include flying frogs in the Hylidae and Rhacophoridae, which also have fully webbed toes used in gliding.

Tree frog, Arboreal frogs have pads located on the ends of their toes to help grip vertical surfaces. These are not suction pads, the surface consisting instead of columnar cells with flat tops with small gaps between them lubricated by mucous glands. When the frog applies pressure, the cells adhere to irregularities on the surface and the grip is maintained through Capillarity, surface tension. This allows the frog to climb on smooth surfaces, but the system does not function efficiently when the pads are excessively wet.

In many arboreal frogs, a small "intercalary structure" on each toe increases the surface area touching the Substrate (biology), substrate. Furthermore, many arboreal frogs have hip joints that allow both hopping and walking. Some frogs that live high in trees even possess an elaborate degree of webbing between their toes. This allows the frogs to "parachute" or make a controlled glide from one position in the canopy to another.

Ground-dwelling frogs generally lack the adaptations of aquatic and arboreal frogs. Most have smaller toe pads, if any, and little webbing. Some burrowing frogs such as Couch's Spadefoot Toad, Couch's spadefoot (''Scaphiopus couchii'') have a flap-like toe extension on the hind feet, a

The muscular system has been similarly modified. The hind limbs of ancestral frogs presumably contained pairs of muscles which would act in opposition (one muscle to flex the knee, a different muscle to extend it), as is seen in most other limbed animals. However, in modern frogs, almost all muscles have been modified to contribute to the action of jumping, with only a few small muscles remaining to bring the limb back to the starting position and maintain posture. The muscles have also been greatly enlarged, with the main leg muscles accounting for over 17% of the total mass of frogs.

Many frogs have webbed feet and the degree of webbing is directly proportional to the amount of time the species spends in the water. The completely aquatic African dwarf frog (''Hymenochirus'' sp.) has fully webbed toes, whereas those of White's tree frog (''Litoria caerulea''), an arboreal species, are only a quarter or half webbed. Exceptions include flying frogs in the Hylidae and Rhacophoridae, which also have fully webbed toes used in gliding.

Tree frog, Arboreal frogs have pads located on the ends of their toes to help grip vertical surfaces. These are not suction pads, the surface consisting instead of columnar cells with flat tops with small gaps between them lubricated by mucous glands. When the frog applies pressure, the cells adhere to irregularities on the surface and the grip is maintained through Capillarity, surface tension. This allows the frog to climb on smooth surfaces, but the system does not function efficiently when the pads are excessively wet.

In many arboreal frogs, a small "intercalary structure" on each toe increases the surface area touching the Substrate (biology), substrate. Furthermore, many arboreal frogs have hip joints that allow both hopping and walking. Some frogs that live high in trees even possess an elaborate degree of webbing between their toes. This allows the frogs to "parachute" or make a controlled glide from one position in the canopy to another.

Ground-dwelling frogs generally lack the adaptations of aquatic and arboreal frogs. Most have smaller toe pads, if any, and little webbing. Some burrowing frogs such as Couch's Spadefoot Toad, Couch's spadefoot (''Scaphiopus couchii'') have a flap-like toe extension on the hind feet, a

File:WoodFrog DarienLakesStatePark 2020-06-16 (02).jpg, Wood Frog:(''Lithobates sylvaticus or Rana sylvatica'') uses disruptive coloration including black eye markings similar to voids between leaves, bands of the dorsal skin (dorsolateral dermal plica) similar to a leaf midrib as well as stains, spots & leg stripes similar to fallen leaf features.

File:Hip-pocket Frog - Assa darlingtoni.jpg, alt=Frog barely recognisable against brown decaying leaf litter., Pouched frog (''Assa darlingtoni'') camouflaged against leaf litter.

The call or croak of a frog is unique to its species. Frogs create this sound by passing air through the larynx in the throat. In most calling frogs, the sound is amplified by one or more vocal sacs, membranes of skin under the throat or on the corner of the mouth, that distend during the amplification of the call. Some frog calls are so loud that they can be heard up to a mile (1.6km) away. Additionally, some species have been found to use man-made structures such as drain pipes for artificial amplification of their call. The Ascaphus truei, coastal tailed frog (''Ascaphus truei'') lives in mountain streams in North America and does not vocalize.

The main function of calling is for male frogs to attract mates. Males may call individually or there may be a chorus of sound where numerous males have converged on breeding sites. In many frog species, such as the Common Tree Frog, common tree frog (''Polypedates leucomystax''), females reply to males' calls, which acts to reinforce reproductive activity in a breeding colony. Female frogs prefer males that produce sounds of greater intensity and lower frequency, attributes that stand out in a crowd. The rationale for this is thought to be that by demonstrating his prowess, the male shows his fitness to produce superior offspring.

A different call is emitted by a male frog or unreceptive female when mounted by another male. This is a distinct chirruping sound and is accompanied by a vibration of the body. Tree frogs and some non-aquatic species have a rain call that they make on the basis of humidity cues prior to a shower. Many species also have a territorial call that is used to drive away other males. All of these calls are emitted with the mouth of the frog closed. A distress call, emitted by some frogs when they are in danger, is produced with the mouth open resulting in a higher-pitched call. It is typically used when the frog has been grabbed by a predator and may serve to distract or disorient the attacker so that it releases the frog.

file:Banded_Bull_Frog_Call.ogg, left, Distinctive low "jug-o-rum" sound of banded bullfrog.

Many species of frog have deep calls. The croak of the American bullfrog (''Rana catesbiana'') is sometimes written as "jug o' rum". The Pacific Tree Frog, Pacific tree frog (''Pseudacris regilla'') produces the onomatopoeia, onomatopoeic "ribbit" often heard in films. Other renderings of frog calls into speech include "brekekekex koax koax", the call of the marsh frog (''Pelophylax ridibundus'') in ''The Frogs'', an Ancient Greek comic drama by Aristophanes. The calls of the Concave-eared torrent frog (''Amolops tormotus'') are unusual in many aspects. The males are notable for their varieties of calls where upward and downward frequency modulations take place. When they communicate, they produce calls that fall in the ultrasound frequency range. The last aspect that makes this species of frog's calls unusual is that nonlinear acoustic phenomena are important components in their acoustic signals.

The call or croak of a frog is unique to its species. Frogs create this sound by passing air through the larynx in the throat. In most calling frogs, the sound is amplified by one or more vocal sacs, membranes of skin under the throat or on the corner of the mouth, that distend during the amplification of the call. Some frog calls are so loud that they can be heard up to a mile (1.6km) away. Additionally, some species have been found to use man-made structures such as drain pipes for artificial amplification of their call. The Ascaphus truei, coastal tailed frog (''Ascaphus truei'') lives in mountain streams in North America and does not vocalize.

The main function of calling is for male frogs to attract mates. Males may call individually or there may be a chorus of sound where numerous males have converged on breeding sites. In many frog species, such as the Common Tree Frog, common tree frog (''Polypedates leucomystax''), females reply to males' calls, which acts to reinforce reproductive activity in a breeding colony. Female frogs prefer males that produce sounds of greater intensity and lower frequency, attributes that stand out in a crowd. The rationale for this is thought to be that by demonstrating his prowess, the male shows his fitness to produce superior offspring.

A different call is emitted by a male frog or unreceptive female when mounted by another male. This is a distinct chirruping sound and is accompanied by a vibration of the body. Tree frogs and some non-aquatic species have a rain call that they make on the basis of humidity cues prior to a shower. Many species also have a territorial call that is used to drive away other males. All of these calls are emitted with the mouth of the frog closed. A distress call, emitted by some frogs when they are in danger, is produced with the mouth open resulting in a higher-pitched call. It is typically used when the frog has been grabbed by a predator and may serve to distract or disorient the attacker so that it releases the frog.

file:Banded_Bull_Frog_Call.ogg, left, Distinctive low "jug-o-rum" sound of banded bullfrog.

Many species of frog have deep calls. The croak of the American bullfrog (''Rana catesbiana'') is sometimes written as "jug o' rum". The Pacific Tree Frog, Pacific tree frog (''Pseudacris regilla'') produces the onomatopoeia, onomatopoeic "ribbit" often heard in films. Other renderings of frog calls into speech include "brekekekex koax koax", the call of the marsh frog (''Pelophylax ridibundus'') in ''The Frogs'', an Ancient Greek comic drama by Aristophanes. The calls of the Concave-eared torrent frog (''Amolops tormotus'') are unusual in many aspects. The males are notable for their varieties of calls where upward and downward frequency modulations take place. When they communicate, they produce calls that fall in the ultrasound frequency range. The last aspect that makes this species of frog's calls unusual is that nonlinear acoustic phenomena are important components in their acoustic signals.

;Jumping

Frogs are generally recognized as exceptional jumpers and, relative to their size, the best jumpers of all vertebrates. The striped rocket frog, ''Litoria nasuta'', can leap over , a distance that is more than fifty times its body length of . There are tremendous differences between species in jumping capability. Within a species, jump distance increases with increasing size, but relative jumping distance (body-lengths jumped) decreases. The Euphlyctis cyanophlyctis, Indian skipper frog (''Euphlyctis cyanophlyctis'') has the ability to leap out of the water from a position floating on the surface. The tiny northern cricket frog (''Acris crepitans'') can "skitter" across the surface of a pond with a series of short rapid jumps.

Slow-motion photography shows that the muscles have passive flexibility. They are first stretched while the frog is still in the crouched position, then they are contracted before being stretched again to launch the frog into the air. The fore legs are folded against the chest and the hind legs remain in the extended, streamlined position for the duration of the jump. In some extremely capable jumpers, such as the Cuban tree frog (''Osteopilus septentrionalis'') and the northern leopard frog (''Rana pipiens''), the peak power exerted during a jump can exceed that which the muscle is theoretically capable of producing. When the muscles contract, the energy is first transferred into the stretched tendon which is wrapped around the ankle bone. Then the muscles stretch again at the same time as the tendon releases its energy like a catapult to produce a powerful acceleration beyond the limits of muscle-powered acceleration. A similar mechanism has been documented in locusts and grasshoppers.

Early hatching of froglets can have negative effects on frog jumping performance and overall locomotion. The hindlimbs are unable to completely form, which results in them being shorter and much weaker relative to a normal hatching froglet. Early hatching froglets may tend to depend on other forms of locomotion more often, such as swimming and walking.

;Walking and running

;Jumping

Frogs are generally recognized as exceptional jumpers and, relative to their size, the best jumpers of all vertebrates. The striped rocket frog, ''Litoria nasuta'', can leap over , a distance that is more than fifty times its body length of . There are tremendous differences between species in jumping capability. Within a species, jump distance increases with increasing size, but relative jumping distance (body-lengths jumped) decreases. The Euphlyctis cyanophlyctis, Indian skipper frog (''Euphlyctis cyanophlyctis'') has the ability to leap out of the water from a position floating on the surface. The tiny northern cricket frog (''Acris crepitans'') can "skitter" across the surface of a pond with a series of short rapid jumps.

Slow-motion photography shows that the muscles have passive flexibility. They are first stretched while the frog is still in the crouched position, then they are contracted before being stretched again to launch the frog into the air. The fore legs are folded against the chest and the hind legs remain in the extended, streamlined position for the duration of the jump. In some extremely capable jumpers, such as the Cuban tree frog (''Osteopilus septentrionalis'') and the northern leopard frog (''Rana pipiens''), the peak power exerted during a jump can exceed that which the muscle is theoretically capable of producing. When the muscles contract, the energy is first transferred into the stretched tendon which is wrapped around the ankle bone. Then the muscles stretch again at the same time as the tendon releases its energy like a catapult to produce a powerful acceleration beyond the limits of muscle-powered acceleration. A similar mechanism has been documented in locusts and grasshoppers.

Early hatching of froglets can have negative effects on frog jumping performance and overall locomotion. The hindlimbs are unable to completely form, which results in them being shorter and much weaker relative to a normal hatching froglet. Early hatching froglets may tend to depend on other forms of locomotion more often, such as swimming and walking.

;Walking and running

Frogs in the families Bufonidae, Rhinophrynidae, and

Frogs in the families Bufonidae, Rhinophrynidae, and  Frogs that live in or visit water have adaptations that improve their swimming abilities. The hind limbs are heavily muscled and strong. The webbing between the toes of the hind feet increases the area of the foot and helps propel the frog powerfully through the water. Members of the family Pipidae are wholly aquatic and show the most marked specialization. They have inflexible vertebral columns, flattened, streamlined bodies, lateral line systems, and powerful hind limbs with large webbed feet. Tadpoles mostly have large tail fins which provide thrust when the tail is moved from side to side.

;Burrowing

Some frogs have become adapted for burrowing and a life underground. They tend to have rounded bodies, short limbs, small heads with bulging eyes, and hind feet adapted for excavation. An extreme example of this is the purple frog (''Nasikabatrachus sahyadrensis'') from southern India which feeds on termites and spends almost its whole life underground. It emerges briefly during the monsoon to mate and breed in temporary pools. It has a tiny head with a pointed snout and a plump, rounded body. Because of this fossorial existence, it was Species description, first described in 2003, being new to the scientific community at that time, although previously known to local people.

Frogs that live in or visit water have adaptations that improve their swimming abilities. The hind limbs are heavily muscled and strong. The webbing between the toes of the hind feet increases the area of the foot and helps propel the frog powerfully through the water. Members of the family Pipidae are wholly aquatic and show the most marked specialization. They have inflexible vertebral columns, flattened, streamlined bodies, lateral line systems, and powerful hind limbs with large webbed feet. Tadpoles mostly have large tail fins which provide thrust when the tail is moved from side to side.

;Burrowing

Some frogs have become adapted for burrowing and a life underground. They tend to have rounded bodies, short limbs, small heads with bulging eyes, and hind feet adapted for excavation. An extreme example of this is the purple frog (''Nasikabatrachus sahyadrensis'') from southern India which feeds on termites and spends almost its whole life underground. It emerges briefly during the monsoon to mate and breed in temporary pools. It has a tiny head with a pointed snout and a plump, rounded body. Because of this fossorial existence, it was Species description, first described in 2003, being new to the scientific community at that time, although previously known to local people.

The spadefoot toads of North America are also adapted to underground life. The Plains spadefoot toad (''Spea bombifrons'') is typical and has a flap of keratinised bone attached to one of the Metatarsus, metatarsals of the hind feet which it uses to dig itself backwards into the ground. As it digs, the toad wriggles its hips from side to side to sink into the loose soil. It has a shallow burrow in the summer from which it emerges at night to forage. In winter, it digs much deeper and has been recorded at a depth of . The tunnel is filled with soil and the toad hibernates in a small chamber at the end. During this time, urea accumulates in its tissues and water is drawn in from the surrounding damp soil by osmosis to supply the toad's needs. Spadefoot toads are "explosive breeders", all emerging from their burrows at the same time and converging on temporary pools, attracted to one of these by the calling of the first male to find a suitable breeding location.

The burrowing frogs of Australia have a rather different lifestyle. The western spotted frog (''Heleioporus albopunctatus'') digs a burrow beside a river or in the bed of an ephemeral stream and regularly emerges to forage. Mating takes place and eggs are laid in a foam nest inside the burrow. The eggs partially develop there, but do not hatch until they are submerged following heavy rainfall. The tadpoles then swim out into the open water and rapidly complete their development. Madagascan burrowing frogs are less fossorial and mostly bury themselves in leaf litter. One of these, the Scaphiophryne marmorata, green burrowing frog (''Scaphiophryne marmorata''), has a flattened head with a short snout and well-developed metatarsal tubercles on its hind feet to help with excavation. It also has greatly enlarged terminal discs on its fore feet that help it to clamber around in bushes. It breeds in temporary pools that form after rains.

;Climbing

The spadefoot toads of North America are also adapted to underground life. The Plains spadefoot toad (''Spea bombifrons'') is typical and has a flap of keratinised bone attached to one of the Metatarsus, metatarsals of the hind feet which it uses to dig itself backwards into the ground. As it digs, the toad wriggles its hips from side to side to sink into the loose soil. It has a shallow burrow in the summer from which it emerges at night to forage. In winter, it digs much deeper and has been recorded at a depth of . The tunnel is filled with soil and the toad hibernates in a small chamber at the end. During this time, urea accumulates in its tissues and water is drawn in from the surrounding damp soil by osmosis to supply the toad's needs. Spadefoot toads are "explosive breeders", all emerging from their burrows at the same time and converging on temporary pools, attracted to one of these by the calling of the first male to find a suitable breeding location.

The burrowing frogs of Australia have a rather different lifestyle. The western spotted frog (''Heleioporus albopunctatus'') digs a burrow beside a river or in the bed of an ephemeral stream and regularly emerges to forage. Mating takes place and eggs are laid in a foam nest inside the burrow. The eggs partially develop there, but do not hatch until they are submerged following heavy rainfall. The tadpoles then swim out into the open water and rapidly complete their development. Madagascan burrowing frogs are less fossorial and mostly bury themselves in leaf litter. One of these, the Scaphiophryne marmorata, green burrowing frog (''Scaphiophryne marmorata''), has a flattened head with a short snout and well-developed metatarsal tubercles on its hind feet to help with excavation. It also has greatly enlarged terminal discs on its fore feet that help it to clamber around in bushes. It breeds in temporary pools that form after rains.

;Climbing

Tree frogs live high in the canopy (biology), canopy, where they scramble around on the branches, twigs, and leaves, sometimes never coming down to earth. The "true" tree frogs belong to the family Hylidae, but members of other frog families have independently adopted an arboreal habit, a case of convergent evolution. These include the glass frogs (Centrolenidae), the Hyperoliidae, bush frogs (Hyperoliidae), some of the narrow-mouthed frogs (Microhylidae), and the Rhacophoridae, shrub frogs (Rhacophoridae). Most tree frogs are under in length, with long legs and long toes with adhesive pads on the tips. The surface of the toe pads is formed from a closely packed layer of flat-topped, hexagonal epidermis (skin), epidermal cells separated by grooves into which glands secrete mucus. These toe pads, moistened by the mucus, provide the grip on any wet or dry surface, including glass. The forces involved include boundary friction of the toe pad epidermis on the surface and also surface tension and viscosity. Tree frogs are very acrobatic and can catch insects while hanging by one toe from a twig or clutching onto the blade of a windswept reed. Some members of the subfamily Phyllomedusinae have Opposable thumb#Opposition and apposition, opposable toes on their feet. The Phyllomedusa ayeaye, reticulated leaf frog (''Phyllomedusa ayeaye'') has a single opposed Digit (anatomy), digit on each fore foot and two opposed digits on its hind feet. This allows it to grasp the stems of bushes as it clambers around in its riverside habitat.

;Gliding

During the evolutionary history of frogs, several different groups have independently taken to the air. Some frogs in the tropical rainforest are specially adapted for gliding from tree to tree or parachuting to the forest floor. Typical of them is Rhacophorus nigropalmatus, Wallace's flying frog (''Rhacophorus nigropalmatus'') from Malaysia and Borneo. It has large feet with the fingertips expanded into flat adhesive discs and the digits fully webbed. Flaps of skin occur on the lateral margins of the limbs and across the tail region. With the digits splayed, the limbs outstretched, and these flaps spread, it can glide considerable distances, but is unable to undertake powered flight. It can alter its direction of travel and navigate distances of up to between trees.

Tree frogs live high in the canopy (biology), canopy, where they scramble around on the branches, twigs, and leaves, sometimes never coming down to earth. The "true" tree frogs belong to the family Hylidae, but members of other frog families have independently adopted an arboreal habit, a case of convergent evolution. These include the glass frogs (Centrolenidae), the Hyperoliidae, bush frogs (Hyperoliidae), some of the narrow-mouthed frogs (Microhylidae), and the Rhacophoridae, shrub frogs (Rhacophoridae). Most tree frogs are under in length, with long legs and long toes with adhesive pads on the tips. The surface of the toe pads is formed from a closely packed layer of flat-topped, hexagonal epidermis (skin), epidermal cells separated by grooves into which glands secrete mucus. These toe pads, moistened by the mucus, provide the grip on any wet or dry surface, including glass. The forces involved include boundary friction of the toe pad epidermis on the surface and also surface tension and viscosity. Tree frogs are very acrobatic and can catch insects while hanging by one toe from a twig or clutching onto the blade of a windswept reed. Some members of the subfamily Phyllomedusinae have Opposable thumb#Opposition and apposition, opposable toes on their feet. The Phyllomedusa ayeaye, reticulated leaf frog (''Phyllomedusa ayeaye'') has a single opposed Digit (anatomy), digit on each fore foot and two opposed digits on its hind feet. This allows it to grasp the stems of bushes as it clambers around in its riverside habitat.

;Gliding

During the evolutionary history of frogs, several different groups have independently taken to the air. Some frogs in the tropical rainforest are specially adapted for gliding from tree to tree or parachuting to the forest floor. Typical of them is Rhacophorus nigropalmatus, Wallace's flying frog (''Rhacophorus nigropalmatus'') from Malaysia and Borneo. It has large feet with the fingertips expanded into flat adhesive discs and the digits fully webbed. Flaps of skin occur on the lateral margins of the limbs and across the tail region. With the digits splayed, the limbs outstretched, and these flaps spread, it can glide considerable distances, but is unable to undertake powered flight. It can alter its direction of travel and navigate distances of up to between trees.

In explosive breeders, the first male that finds a suitable breeding location, such as a temporary pool, calls loudly and other frogs of both sexes converge on the pool. Explosive breeders tend to call in unison creating a chorus that can be heard from far away. The spadefoot toads (''Scaphiopus spp.'') of North America fall into this category. Mate selection and courtship is not as important as speed in reproduction. In some years, suitable conditions may not occur and the frogs may go for two or more years without breeding. Some female New Mexico Spadefoot Toad, New Mexico spadefoot toads (''Spea multiplicata'') only spawn half of the available eggs at a time, perhaps retaining some in case a better reproductive opportunity arises later.

At the breeding site, the male mounts the female and grips her tightly round the body. Typically, amplexus takes place in the water, the female releases her eggs and the male covers them with sperm; fertilization is external fertilization, external. In many species such as the Great Plains toad (''Bufo cognatus''), the male restrains the eggs with his back feet, holding them in place for about three minutes. Members of the West African genus ''Nimbaphrynoides'' are unique among frogs in that they are Viviparity, viviparous; ''Limnonectes larvaepartus'', ''Eleutherodactylus jasperi'' and members of the Tanzanian genus ''Nectophrynoides'' are the only frogs known to be Ovoviviparity, ovoviviparous. In these species, fertilization is Internal fertilization, internal and females give birth to fully developed juvenile frogs, except ''L. larvaepartus'', which give birth to tadpoles.

In explosive breeders, the first male that finds a suitable breeding location, such as a temporary pool, calls loudly and other frogs of both sexes converge on the pool. Explosive breeders tend to call in unison creating a chorus that can be heard from far away. The spadefoot toads (''Scaphiopus spp.'') of North America fall into this category. Mate selection and courtship is not as important as speed in reproduction. In some years, suitable conditions may not occur and the frogs may go for two or more years without breeding. Some female New Mexico Spadefoot Toad, New Mexico spadefoot toads (''Spea multiplicata'') only spawn half of the available eggs at a time, perhaps retaining some in case a better reproductive opportunity arises later.

At the breeding site, the male mounts the female and grips her tightly round the body. Typically, amplexus takes place in the water, the female releases her eggs and the male covers them with sperm; fertilization is external fertilization, external. In many species such as the Great Plains toad (''Bufo cognatus''), the male restrains the eggs with his back feet, holding them in place for about three minutes. Members of the West African genus ''Nimbaphrynoides'' are unique among frogs in that they are Viviparity, viviparous; ''Limnonectes larvaepartus'', ''Eleutherodactylus jasperi'' and members of the Tanzanian genus ''Nectophrynoides'' are the only frogs known to be Ovoviviparity, ovoviviparous. In these species, fertilization is Internal fertilization, internal and females give birth to fully developed juvenile frogs, except ''L. larvaepartus'', which give birth to tadpoles.

Frogs may lay their in eggs as clumps, surface films, strings, or individually. Around half of species deposit eggs in water, others lay eggs in vegetation, on the ground or in excavations. The tiny Yellow-Striped Pygmy Eleuth, yellow-striped pygmy eleuth (''Eleutherodactylus limbatus'') lays eggs singly, burying them in moist soil. The Smoky Jungle Frog, smoky jungle frog (''Leptodactylus pentadactylus'') makes a nest of foam in a hollow. The eggs hatch when the nest is flooded, or the tadpoles may complete their development in the foam if flooding does not occur. The red-eyed treefrog (''Agalychnis callidryas'') deposits its eggs on a leaf above a pool and when they hatch, the larvae fall into the water below.

In certain species, such as the wood frog (''Rana sylvatica''), Symbiosis, symbiotic unicellular green algae are present in the gelatinous material. It is thought that these may benefit the developing larvae by providing them with extra oxygen through photosynthesis. The interior of globular egg clusters of the Wood Frog, wood frog has been also been found to be up to 6 °C (11 °F) warmer than the surrounding water and this speeds up the development of the larvae. The larvae developing in the eggs can detect vibrations caused by nearby predatory wasps or snakes, and will hatch early to avoid being eaten. In general, the length of the egg stage depends on the species and the environmental conditions. Aquatic eggs normally hatch within one week when the capsule splits as a result of enzymes released by the developing larvae.

Direct development, where eggs hatch into juveniles like small adults, is also known in many frogs, for example, ''Ischnocnema henselii,'' ''Common coquí, Eleutherodactylus coqui'', and ''Raorchestes ochlandrae'' and ''Raorchestes chalazodes.''

Frogs may lay their in eggs as clumps, surface films, strings, or individually. Around half of species deposit eggs in water, others lay eggs in vegetation, on the ground or in excavations. The tiny Yellow-Striped Pygmy Eleuth, yellow-striped pygmy eleuth (''Eleutherodactylus limbatus'') lays eggs singly, burying them in moist soil. The Smoky Jungle Frog, smoky jungle frog (''Leptodactylus pentadactylus'') makes a nest of foam in a hollow. The eggs hatch when the nest is flooded, or the tadpoles may complete their development in the foam if flooding does not occur. The red-eyed treefrog (''Agalychnis callidryas'') deposits its eggs on a leaf above a pool and when they hatch, the larvae fall into the water below.

In certain species, such as the wood frog (''Rana sylvatica''), Symbiosis, symbiotic unicellular green algae are present in the gelatinous material. It is thought that these may benefit the developing larvae by providing them with extra oxygen through photosynthesis. The interior of globular egg clusters of the Wood Frog, wood frog has been also been found to be up to 6 °C (11 °F) warmer than the surrounding water and this speeds up the development of the larvae. The larvae developing in the eggs can detect vibrations caused by nearby predatory wasps or snakes, and will hatch early to avoid being eaten. In general, the length of the egg stage depends on the species and the environmental conditions. Aquatic eggs normally hatch within one week when the capsule splits as a result of enzymes released by the developing larvae.

Direct development, where eggs hatch into juveniles like small adults, is also known in many frogs, for example, ''Ischnocnema henselii,'' ''Common coquí, Eleutherodactylus coqui'', and ''Raorchestes ochlandrae'' and ''Raorchestes chalazodes.''

The larvae that emerge from the eggs, known as tadpoles (or occasionally polliwogs). Tadpoles lack eyelids and limbs, and have cartilaginous skeletons, gills for respiration (external gills at first, internal gills later), and tails they use for swimming. As a general rule, free-living larvae are fully aquatic, but at least one species (''Nannophrys ceylonensis'') has semiterrestrial tadpoles which live among wet rocks.

From early in its development, a gill pouch covers the tadpole's gills and front legs. The lungs soon start to develop and are used as an accessory breathing organ. Some species go through metamorphosis while still inside the egg and hatch directly into small frogs. Tadpoles lack true teeth, but the jaws in most species have two elongated, parallel rows of small,

The larvae that emerge from the eggs, known as tadpoles (or occasionally polliwogs). Tadpoles lack eyelids and limbs, and have cartilaginous skeletons, gills for respiration (external gills at first, internal gills later), and tails they use for swimming. As a general rule, free-living larvae are fully aquatic, but at least one species (''Nannophrys ceylonensis'') has semiterrestrial tadpoles which live among wet rocks.

From early in its development, a gill pouch covers the tadpole's gills and front legs. The lungs soon start to develop and are used as an accessory breathing organ. Some species go through metamorphosis while still inside the egg and hatch directly into small frogs. Tadpoles lack true teeth, but the jaws in most species have two elongated, parallel rows of small,

Frogs are primary predators and an important part of the food web. Being Ectotherm, cold-blooded, they make efficient use of the food they eat with little energy being used for metabolic processes, while the rest is transformed into biomass (ecology), biomass. They are themselves eaten by secondary predators and are the primary terrestrial consumers of invertebrates, most of which feed on plants. By reducing herbivory, they play a part in increasing the growth of plants and are thus part of a delicately balanced ecosystem.

Little is known about the longevity of frogs and toads in the wild, but some can live for many years. Skeletochronology is a method of examining bones to determine age. Using this method, the ages of mountain yellow-legged frogs (''Rana muscosa'') were studied, the phalanges of the toes showing seasonal lines where growth slows in winter. The oldest frogs had ten bands, so their age was believed to be 14 years, including the four-year tadpole stage. Captive frogs and toads have been recorded as living for up to 40 years, an age achieved by a European common toad (''Bufo bufo''). The cane toad (''Bufo marinus'') has been known to survive 24 years in captivity, and the American bullfrog (''Rana catesbeiana'') 14 years. Frogs from temperate climates hibernate during the winter, and four species are known to be able to withstand freezing during this time, including the wood frog (''Rana sylvatica'').

Frogs are primary predators and an important part of the food web. Being Ectotherm, cold-blooded, they make efficient use of the food they eat with little energy being used for metabolic processes, while the rest is transformed into biomass (ecology), biomass. They are themselves eaten by secondary predators and are the primary terrestrial consumers of invertebrates, most of which feed on plants. By reducing herbivory, they play a part in increasing the growth of plants and are thus part of a delicately balanced ecosystem.

Little is known about the longevity of frogs and toads in the wild, but some can live for many years. Skeletochronology is a method of examining bones to determine age. Using this method, the ages of mountain yellow-legged frogs (''Rana muscosa'') were studied, the phalanges of the toes showing seasonal lines where growth slows in winter. The oldest frogs had ten bands, so their age was believed to be 14 years, including the four-year tadpole stage. Captive frogs and toads have been recorded as living for up to 40 years, an age achieved by a European common toad (''Bufo bufo''). The cane toad (''Bufo marinus'') has been known to survive 24 years in captivity, and the American bullfrog (''Rana catesbeiana'') 14 years. Frogs from temperate climates hibernate during the winter, and four species are known to be able to withstand freezing during this time, including the wood frog (''Rana sylvatica'').

Although care of offspring is poorly understood in frogs, up to an estimated 20% of amphibian species may care for their young in some way. The evolution of biparental care in tropical frogs, evolution of parental care in frogs is driven primarily by the size of the water body in which they breed. Those that breed in smaller water bodies tend to have greater and more complex parental care behaviour. Because predation of eggs and larvae is high in large water bodies, some frog species started to lay their eggs on land. Once this happened, the desiccating terrestrial environment demands that one or both parents keep them moist to ensure their survival. The subsequent need to transport hatched tadpoles to a water body required an even more intense form of parental care.

In small pools, predators are mostly absent and competition between tadpoles becomes the variable that constrains their survival. Certain frog species avoid this competition by making use of smaller phytotelmata (water-filled leaf wikt:axil, axils or small woody cavities) as sites for depositing a few tadpoles. While these smaller rearing sites are free from competition, they also lack sufficient nutrients to support a tadpole without parental assistance. Frog species that changed from the use of larger to smaller phytotelmata have evolved a strategy of providing their offspring with nutritive but unfertilized eggs. The female strawberry poison-dart frog (''Oophaga pumilio'') lays her eggs on the forest floor. The male frog guards them from predation and carries water in his cloaca to keep them moist. When they hatch, the female moves the tadpoles on her back to a water-holding bromeliad or other similar water body, depositing just one in each location. She visits them regularly and feeds them by laying one or two unfertilized eggs in the phytotelma, continuing to do this until the young are large enough to undergo metamorphosis. The granular poison frog (''Oophaga granulifera'') looks after its tadpoles in a similar way.

Many other diverse forms of parental care are seen in frogs. The tiny male ''Colostethus subpunctatus'' stands guard over his egg cluster, laid under a stone or log. When the eggs hatch, he transports the tadpoles on his back to a temporary pool, where he partially immerses himself in the water and one or more tadpoles drop off. He then moves on to another pool. The male common midwife toad (''Alytes obstetricans'') carries the eggs around with him attached to his hind legs. He keeps them damp in dry weather by immersing himself in a pond, and prevents them from getting too wet in soggy vegetation by raising his hindquarters. After three to six weeks, he travels to a pond and the eggs hatch into tadpoles. The tungara frog (''Physalaemus pustulosus'') builds a floating nest from foam to protect its eggs from predation. The foam is made from proteins and lectins, and seems to have antimicrobial properties. Several pairs of frogs may form a colonial nest on a previously built raft. The eggs are laid in the centre, followed by alternate layers of foam and eggs, finishing with a foam capping.

Some frogs protect their offspring inside their own bodies. Both male and female pouched frogs (''Assa darlingtoni'') guard their eggs, which are laid on the ground. When the eggs hatch, the male lubricates his body with the jelly surrounding them and immerses himself in the egg mass. The tadpoles wriggle into skin pouches on his side, where they develop until they metamorphose into juvenile frogs. The female gastric-brooding frog (''Rheobatrachus'' sp.) from Australia, now probably extinct, swallows her fertilized eggs, which then develop inside her stomach. She ceases to feed and stops secreting stomach acid. The tadpoles rely on the yolks of the eggs for nourishment. After six or seven weeks, they are ready for metamorphosis. The mother regurgitates the tiny frogs, which hop away from her mouth. The female Darwin's frog (''Rhinoderma darwinii'') from Chile lays up to 40 eggs on the ground, where they are guarded by the male. When the tadpoles are about to hatch, they are engulfed by the male, which carries them around inside his much-enlarged vocal sac. Here they are immersed in a frothy, viscous liquid that contains some nourishment to supplement what they obtain from the yolks of the eggs. They remain in the sac for seven to ten weeks before undergoing metamorphosis, after which they move into the male's mouth and emerge.

Although care of offspring is poorly understood in frogs, up to an estimated 20% of amphibian species may care for their young in some way. The evolution of biparental care in tropical frogs, evolution of parental care in frogs is driven primarily by the size of the water body in which they breed. Those that breed in smaller water bodies tend to have greater and more complex parental care behaviour. Because predation of eggs and larvae is high in large water bodies, some frog species started to lay their eggs on land. Once this happened, the desiccating terrestrial environment demands that one or both parents keep them moist to ensure their survival. The subsequent need to transport hatched tadpoles to a water body required an even more intense form of parental care.

In small pools, predators are mostly absent and competition between tadpoles becomes the variable that constrains their survival. Certain frog species avoid this competition by making use of smaller phytotelmata (water-filled leaf wikt:axil, axils or small woody cavities) as sites for depositing a few tadpoles. While these smaller rearing sites are free from competition, they also lack sufficient nutrients to support a tadpole without parental assistance. Frog species that changed from the use of larger to smaller phytotelmata have evolved a strategy of providing their offspring with nutritive but unfertilized eggs. The female strawberry poison-dart frog (''Oophaga pumilio'') lays her eggs on the forest floor. The male frog guards them from predation and carries water in his cloaca to keep them moist. When they hatch, the female moves the tadpoles on her back to a water-holding bromeliad or other similar water body, depositing just one in each location. She visits them regularly and feeds them by laying one or two unfertilized eggs in the phytotelma, continuing to do this until the young are large enough to undergo metamorphosis. The granular poison frog (''Oophaga granulifera'') looks after its tadpoles in a similar way.

Many other diverse forms of parental care are seen in frogs. The tiny male ''Colostethus subpunctatus'' stands guard over his egg cluster, laid under a stone or log. When the eggs hatch, he transports the tadpoles on his back to a temporary pool, where he partially immerses himself in the water and one or more tadpoles drop off. He then moves on to another pool. The male common midwife toad (''Alytes obstetricans'') carries the eggs around with him attached to his hind legs. He keeps them damp in dry weather by immersing himself in a pond, and prevents them from getting too wet in soggy vegetation by raising his hindquarters. After three to six weeks, he travels to a pond and the eggs hatch into tadpoles. The tungara frog (''Physalaemus pustulosus'') builds a floating nest from foam to protect its eggs from predation. The foam is made from proteins and lectins, and seems to have antimicrobial properties. Several pairs of frogs may form a colonial nest on a previously built raft. The eggs are laid in the centre, followed by alternate layers of foam and eggs, finishing with a foam capping.

Some frogs protect their offspring inside their own bodies. Both male and female pouched frogs (''Assa darlingtoni'') guard their eggs, which are laid on the ground. When the eggs hatch, the male lubricates his body with the jelly surrounding them and immerses himself in the egg mass. The tadpoles wriggle into skin pouches on his side, where they develop until they metamorphose into juvenile frogs. The female gastric-brooding frog (''Rheobatrachus'' sp.) from Australia, now probably extinct, swallows her fertilized eggs, which then develop inside her stomach. She ceases to feed and stops secreting stomach acid. The tadpoles rely on the yolks of the eggs for nourishment. After six or seven weeks, they are ready for metamorphosis. The mother regurgitates the tiny frogs, which hop away from her mouth. The female Darwin's frog (''Rhinoderma darwinii'') from Chile lays up to 40 eggs on the ground, where they are guarded by the male. When the tadpoles are about to hatch, they are engulfed by the male, which carries them around inside his much-enlarged vocal sac. Here they are immersed in a frothy, viscous liquid that contains some nourishment to supplement what they obtain from the yolks of the eggs. They remain in the sac for seven to ten weeks before undergoing metamorphosis, after which they move into the male's mouth and emerge.

At first sight, frogs seem rather defenceless because of their small size, slow movement, thin skin, and lack of defensive structures, such as spines, claws or teeth. Many use camouflage to avoid detection, the skin often being spotted or streaked in neutral colours that allow a stationary frog to merge into its surroundings. Some can make prodigious leaps, often into water, that help them to evade potential attackers, while many have other defensive adaptations and strategies.

The skin of many frogs contains mild toxic substances called bufotoxins to make them unpalatable to potential predators. Most toads and some frogs have large poison glands, the parotoid glands, located on the sides of their heads behind the eyes and other glands elsewhere on their bodies. These glands secrete mucus and a range of toxins that make frogs slippery to hold and distasteful or poisonous. If the noxious effect is immediate, the predator may cease its action and the frog may escape. If the effect develops more slowly, the predator may learn to avoid that species in future. Poisonous frogs tend to advertise their toxicity with bright colours, an adaptive strategy known as aposematism. The Poison dart frog, poison dart frogs in the family Dendrobatidae do this. They are typically red, orange, or yellow, often with contrasting black markings on their bodies. ''Allobates zaparo'' is not poisonous, but mimics the appearance of two different toxic species with which it shares a common range in an effort to deceive predators. Other species, such as the European Fire-bellied Toad, European fire-bellied toad (''Bombina bombina''), have their warning colour underneath. They "flash" this when attacked, adopting a pose that exposes the vivid colouring on their bellies.

At first sight, frogs seem rather defenceless because of their small size, slow movement, thin skin, and lack of defensive structures, such as spines, claws or teeth. Many use camouflage to avoid detection, the skin often being spotted or streaked in neutral colours that allow a stationary frog to merge into its surroundings. Some can make prodigious leaps, often into water, that help them to evade potential attackers, while many have other defensive adaptations and strategies.

The skin of many frogs contains mild toxic substances called bufotoxins to make them unpalatable to potential predators. Most toads and some frogs have large poison glands, the parotoid glands, located on the sides of their heads behind the eyes and other glands elsewhere on their bodies. These glands secrete mucus and a range of toxins that make frogs slippery to hold and distasteful or poisonous. If the noxious effect is immediate, the predator may cease its action and the frog may escape. If the effect develops more slowly, the predator may learn to avoid that species in future. Poisonous frogs tend to advertise their toxicity with bright colours, an adaptive strategy known as aposematism. The Poison dart frog, poison dart frogs in the family Dendrobatidae do this. They are typically red, orange, or yellow, often with contrasting black markings on their bodies. ''Allobates zaparo'' is not poisonous, but mimics the appearance of two different toxic species with which it shares a common range in an effort to deceive predators. Other species, such as the European Fire-bellied Toad, European fire-bellied toad (''Bombina bombina''), have their warning colour underneath. They "flash" this when attacked, adopting a pose that exposes the vivid colouring on their bellies.

Some frogs, such as the poison dart frogs, are especially toxic. The native peoples of South America extract poison from these frogs to apply to their Dart (missile), weapons for hunting, although few species are toxic enough to be used for this purpose. At least two non-poisonous frog species in tropical America (''Eleutherodactylus, Eleutherodactylus gaigei'' and ''Lithodytes lineatus'') Batesian mimicry, mimic the colouration of dart poison frogs for self-protection. Some frogs obtain poisons from the ants and other arthropods they eat. Others, such as the Australian corroboree frogs (''Pseudophryne corroboree'' and ''Pseudophryne pengilleyi''), can synthesize the alkaloids themselves. The chemicals involved may be irritants, hallucinogens, seizure, convulsants, neurotoxin, nerve poisons or vasoconstrictors. Many predators of frogs have become adapted to tolerate high levels of these poisons, but other creatures, including humans who handle the frogs, may be severely affected.

Some frogs use bluff or deception. The European common toad (''Bufo bufo'') adopts a characteristic stance when attacked, inflating its body and standing with its hindquarters raised and its head lowered. The bullfrog (''Rana catesbeiana'') crouches down with eyes closed and head tipped forward when threatened. This places the parotoid glands in the most effective position, the other glands on its back begin to ooze noxious secretions and the most vulnerable parts of its body are protected. Another tactic used by some frogs is to "scream", the sudden loud noise tending to startle the predator. The gray tree frog (''Hyla versicolor'') makes an explosive sound that sometimes repels the shrew ''Blarina brevicauda''. Although toads are avoided by many predators, the Common Garter Snake, common garter snake (''Thamnophis sirtalis'') regularly feeds on them. The strategy employed by juvenile American toads (''Bufo americanus'') on being approached by a snake is to crouch down and remain immobile. This is usually successful, with the snake passing by and the toad remaining undetected. If it is encountered by the snake's head, however, the toad hops away before crouching defensively.

Some frogs, such as the poison dart frogs, are especially toxic. The native peoples of South America extract poison from these frogs to apply to their Dart (missile), weapons for hunting, although few species are toxic enough to be used for this purpose. At least two non-poisonous frog species in tropical America (''Eleutherodactylus, Eleutherodactylus gaigei'' and ''Lithodytes lineatus'') Batesian mimicry, mimic the colouration of dart poison frogs for self-protection. Some frogs obtain poisons from the ants and other arthropods they eat. Others, such as the Australian corroboree frogs (''Pseudophryne corroboree'' and ''Pseudophryne pengilleyi''), can synthesize the alkaloids themselves. The chemicals involved may be irritants, hallucinogens, seizure, convulsants, neurotoxin, nerve poisons or vasoconstrictors. Many predators of frogs have become adapted to tolerate high levels of these poisons, but other creatures, including humans who handle the frogs, may be severely affected.

Some frogs use bluff or deception. The European common toad (''Bufo bufo'') adopts a characteristic stance when attacked, inflating its body and standing with its hindquarters raised and its head lowered. The bullfrog (''Rana catesbeiana'') crouches down with eyes closed and head tipped forward when threatened. This places the parotoid glands in the most effective position, the other glands on its back begin to ooze noxious secretions and the most vulnerable parts of its body are protected. Another tactic used by some frogs is to "scream", the sudden loud noise tending to startle the predator. The gray tree frog (''Hyla versicolor'') makes an explosive sound that sometimes repels the shrew ''Blarina brevicauda''. Although toads are avoided by many predators, the Common Garter Snake, common garter snake (''Thamnophis sirtalis'') regularly feeds on them. The strategy employed by juvenile American toads (''Bufo americanus'') on being approached by a snake is to crouch down and remain immobile. This is usually successful, with the snake passing by and the toad remaining undetected. If it is encountered by the snake's head, however, the toad hops away before crouching defensively.

Frogs live on all the continents except Antarctica, but they are not present on certain islands, especially those far away from continental land masses. Many species are isolated in restricted ranges by changes of climate or inhospitable territory, such as stretches of sea, mountain ridges, deserts, forest clearance, road construction, or other man-made barriers. Usually, a greater diversity of frogs occurs in tropical areas than in temperate regions, such as Europe. Some frogs inhabit arid areas, such as deserts, and rely on specific adaptations to survive. Members of the Australian genus ''Cyclorana'' bury themselves underground where they create a water-impervious cocoon in which to aestivation, aestivate during dry periods. Once it rains, they emerge, find a temporary pool, and breed. Egg and tadpole development is very fast in comparison to those of most other frogs, so breeding can be completed before the pond dries up. Some frog species are adapted to a cold environment. The wood frog (''Rana sylvatica''), whose habitat extends into the Arctic Circle, buries itself in the ground during winter. Although much of its body freezes during this time, it maintains a high concentration of glucose in its vital organs, which protects them from damage.

Frogs live on all the continents except Antarctica, but they are not present on certain islands, especially those far away from continental land masses. Many species are isolated in restricted ranges by changes of climate or inhospitable territory, such as stretches of sea, mountain ridges, deserts, forest clearance, road construction, or other man-made barriers. Usually, a greater diversity of frogs occurs in tropical areas than in temperate regions, such as Europe. Some frogs inhabit arid areas, such as deserts, and rely on specific adaptations to survive. Members of the Australian genus ''Cyclorana'' bury themselves underground where they create a water-impervious cocoon in which to aestivation, aestivate during dry periods. Once it rains, they emerge, find a temporary pool, and breed. Egg and tadpole development is very fast in comparison to those of most other frogs, so breeding can be completed before the pond dries up. Some frog species are adapted to a cold environment. The wood frog (''Rana sylvatica''), whose habitat extends into the Arctic Circle, buries itself in the ground during winter. Although much of its body freezes during this time, it maintains a high concentration of glucose in its vital organs, which protects them from damage.

In 2006, of 4,035 species of amphibians that depend on water during some lifecycle stage, 1,356 (33.6%) were considered to be threatened. This is likely to be an underestimate because it excludes 1,427 species for which evidence was insufficient to assess their status. Frog populations have declined dramatically since the 1950s. More than one-third of frog species are considered to be threatened with extinction, and more than 120 species are believed to have become extinct since the 1980s. Among these species are the gastric-brooding frogs of Australia and the golden toad of Costa Rica. The latter is of particular concern to scientists because it inhabited the pristine Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve and its population crashed in 1987, along with about 20 other frog species in the area. This could not be linked directly to human activities, such as deforestation, and was outside the range of normal fluctuations in population size. Elsewhere, habitat loss is a significant cause of frog population decline, as are pollutants, climate change, increased ultraviolet, UVB radiation, and the introduction of Indigenous (ecology), non-native predators and competitors. A Canadian study conducted in 2006 suggested heavy traffic in their environment was a larger threat to frog populations than was habitat loss. Emerging infectious diseases, including chytridiomycosis and ranavirus, are also devastating populations.

Many environmental scientists believe amphibians, including frogs, are good biological indicator species, indicators of broader

In 2006, of 4,035 species of amphibians that depend on water during some lifecycle stage, 1,356 (33.6%) were considered to be threatened. This is likely to be an underestimate because it excludes 1,427 species for which evidence was insufficient to assess their status. Frog populations have declined dramatically since the 1950s. More than one-third of frog species are considered to be threatened with extinction, and more than 120 species are believed to have become extinct since the 1980s. Among these species are the gastric-brooding frogs of Australia and the golden toad of Costa Rica. The latter is of particular concern to scientists because it inhabited the pristine Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve and its population crashed in 1987, along with about 20 other frog species in the area. This could not be linked directly to human activities, such as deforestation, and was outside the range of normal fluctuations in population size. Elsewhere, habitat loss is a significant cause of frog population decline, as are pollutants, climate change, increased ultraviolet, UVB radiation, and the introduction of Indigenous (ecology), non-native predators and competitors. A Canadian study conducted in 2006 suggested heavy traffic in their environment was a larger threat to frog populations than was habitat loss. Emerging infectious diseases, including chytridiomycosis and ranavirus, are also devastating populations.

Many environmental scientists believe amphibians, including frogs, are good biological indicator species, indicators of broader

Frog legs are eaten by humans in many parts of the world. Indonesia is the world's largest exporter of frog meat, exporting more than 5,000 tonnes of frog meat each year, mostly to France, Belgium and Luxembourg.̺ Originally, they were supplied from local wild populations, but overexploitation led to a diminution in the supply. This resulted in the development of Aquaculture, frog farming and a global trade in frogs. The main importing countries are France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the United States, while the chief exporting nations are Indonesia and China. The annual global trade in the American bullfrog (''Rana catesbeiana''), mostly farmed in China, varies between 1200 and 2400 tonnes.

The Leptodactylus fallax, mountain chicken frog, so-called as it tastes of chicken, is now endangered, in part due to human consumption, and was a major food choice of the Dominicans. Coon, possum, partridges, prairie hen, and frogs were among the fare Mark Twain recorded as part of American cuisine.

Frog legs are eaten by humans in many parts of the world. Indonesia is the world's largest exporter of frog meat, exporting more than 5,000 tonnes of frog meat each year, mostly to France, Belgium and Luxembourg.̺ Originally, they were supplied from local wild populations, but overexploitation led to a diminution in the supply. This resulted in the development of Aquaculture, frog farming and a global trade in frogs. The main importing countries are France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the United States, while the chief exporting nations are Indonesia and China. The annual global trade in the American bullfrog (''Rana catesbeiana''), mostly farmed in China, varies between 1200 and 2400 tonnes.

The Leptodactylus fallax, mountain chicken frog, so-called as it tastes of chicken, is now endangered, in part due to human consumption, and was a major food choice of the Dominicans. Coon, possum, partridges, prairie hen, and frogs were among the fare Mark Twain recorded as part of American cuisine.

Because frog toxins are extraordinarily diverse, they have raised the interest of biochemists as a "natural pharmacy". The alkaloid epibatidine, a painkiller 200 times more potent than morphine, is made by some species of Poison dart frog, poison dart frogs. Other chemicals isolated from the skins of frogs may offer resistance to HIV infection. Dart poisons are under active investigation for their potential as therapeutic drugs.

It has long been suspected that pre-Columbian Mesoamericans used a toxic secretion produced by the cane toad as a hallucinogen, but more likely they used substances secreted by the Colorado River toad (''Bufo alvarius''). These contain bufotenin (5-MeO-DMT), a psychoactive drug, psychoactive compound that has been used in modern times as a recreational drug. Typically, the skin secretions are dried and then smoked. Illicit drug use by licking the skin of a toad has been reported in the media, but this may be an urban myth.

Exudations from the skin of the golden poison frog (''Phyllobates terribilis'') are traditionally used by native Colombians to poison the darts they use for hunting. The tip of the projectile is rubbed over the back of the frog and the dart is launched from a blowgun. The combination of the two alkaloid toxins batrachotoxin and homobatrachotoxin is so powerful, one frog contains enough poison to kill an estimated 22,000 mice. Two other species, the Kokoe poison dart frog (''Phyllobates aurotaenia'') and the black-legged dart frog (''Phyllobates bicolor'') are also used for this purpose. These are less toxic and less abundant than the golden poison frog. They are impaled on pointed sticks and may be heated over a fire to maximise the quantity of poison that can be transferred to the dart.

Because frog toxins are extraordinarily diverse, they have raised the interest of biochemists as a "natural pharmacy". The alkaloid epibatidine, a painkiller 200 times more potent than morphine, is made by some species of Poison dart frog, poison dart frogs. Other chemicals isolated from the skins of frogs may offer resistance to HIV infection. Dart poisons are under active investigation for their potential as therapeutic drugs.

It has long been suspected that pre-Columbian Mesoamericans used a toxic secretion produced by the cane toad as a hallucinogen, but more likely they used substances secreted by the Colorado River toad (''Bufo alvarius''). These contain bufotenin (5-MeO-DMT), a psychoactive drug, psychoactive compound that has been used in modern times as a recreational drug. Typically, the skin secretions are dried and then smoked. Illicit drug use by licking the skin of a toad has been reported in the media, but this may be an urban myth.

Exudations from the skin of the golden poison frog (''Phyllobates terribilis'') are traditionally used by native Colombians to poison the darts they use for hunting. The tip of the projectile is rubbed over the back of the frog and the dart is launched from a blowgun. The combination of the two alkaloid toxins batrachotoxin and homobatrachotoxin is so powerful, one frog contains enough poison to kill an estimated 22,000 mice. Two other species, the Kokoe poison dart frog (''Phyllobates aurotaenia'') and the black-legged dart frog (''Phyllobates bicolor'') are also used for this purpose. These are less toxic and less abundant than the golden poison frog. They are impaled on pointed sticks and may be heated over a fire to maximise the quantity of poison that can be transferred to the dart.

AmphibiaWeb

Gallery of Frogs

nbsp;– Photography and images of various frog species

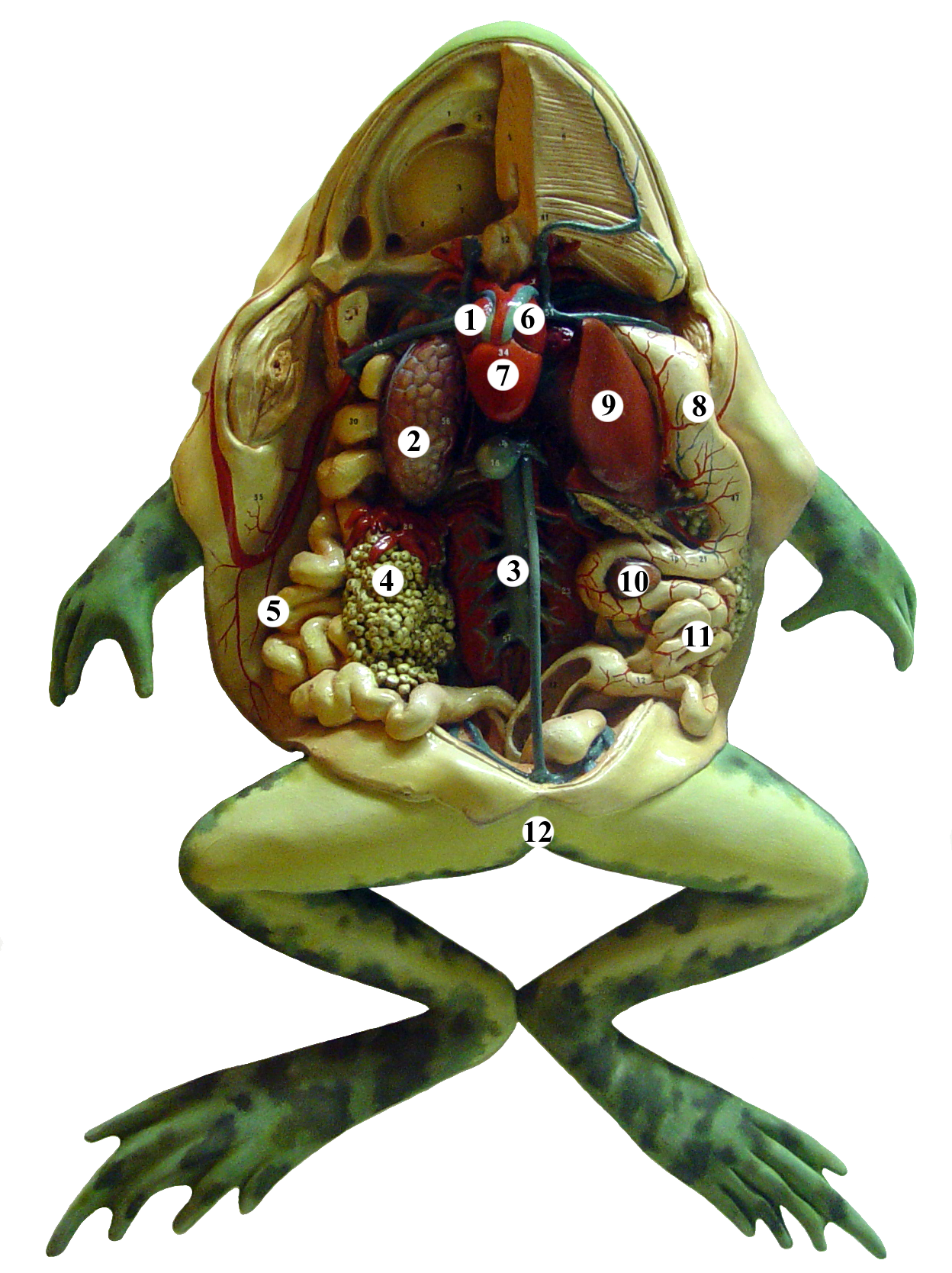

The Whole Frog Project

nbsp;– Virtual frog dissection and anatomy

''San Francisco Chronicle'', 20 April 1992

nbsp;– Features many unusual frogs

''Scientific American'': Researchers Pinpoint Source of Poison Frogs' Deadly Defenses

Time-lapse video showing the egg's development until hatching

Frog vocalisations from around the world

nbsp;– From the British Library Sound Archive

Frog calls

nbsp;– From Manitoba, Canada {{Featured article Frogs, 01 Articles containing video clips Extant Hettangian first appearances

A frog is any member of a diverse and largely

A frog is any member of a diverse and largely carnivorous

A carnivore , or meat-eater (Latin, ''caro'', genitive ''carnis'', meaning meat or "flesh" and ''vorare'' meaning "to devour"), is an animal or plant whose food and energy requirements derive from animal tissues (mainly muscle, fat and other sof ...

group of short-bodied, tailless amphibian

Amphibians are tetrapod, four-limbed and ectothermic vertebrates of the Class (biology), class Amphibia. All living amphibians belong to the group Lissamphibia. They inhabit a wide variety of habitats, with most species living within terres ...

s composing the order

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* Heterarchy, a system of organization wherein the elements have the potential to be ranked a number of d ...

Anura (ανοὐρά, literally ''without tail'' in Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

). The oldest fossil "proto-frog" '' Triadobatrachus'' is known from the Early Triassic

The Early Triassic is the first of three epochs of the Triassic Period of the geologic timescale. It spans the time between Ma and Ma (million years ago). Rocks from this epoch are collectively known as the Lower Triassic Series, which is a un ...

of Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

, but molecular clock dating suggests their split from other amphibians may extend further back to the Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.9 Mya. It is the last period of the Paleoz ...

, 265 million years ago

The abbreviation Myr, "million years", is a unit of a quantity of (i.e. ) years, or 31.556926 teraseconds.

Usage

Myr (million years) is in common use in fields such as Earth science and cosmology. Myr is also used with Mya (million years ago). ...

. Frogs are widely distributed, ranging from the tropics

The tropics are the regions of Earth surrounding the Equator. They are defined in latitude by the Tropic of Cancer in the Northern Hemisphere at N and the Tropic of Capricorn in

the Southern Hemisphere at S. The tropics are also referred to ...

to subarctic

The subarctic zone is a region in the Northern Hemisphere immediately south of the true Arctic, north of humid continental regions and covering much of Alaska, Canada, Iceland, the north of Scandinavia, Siberia, and the Cairngorms. Generally, ...

regions, but the greatest concentration of species diversity is in tropical rainforest

Tropical rainforests are rainforests that occur in areas of tropical rainforest climate in which there is no dry season – all months have an average precipitation of at least 60 mm – and may also be referred to as ''lowland equatori ...

. Frogs account for around 88% of extant amphibian species. They are also one of the five most diverse vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () ( chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, ...

orders. Warty frog species tend to be called toad

Toad is a common name for certain frogs, especially of the family Bufonidae, that are characterized by dry, leathery skin, short legs, and large bumps covering the parotoid glands.

A distinction between frogs and toads is not made in scientif ...

s, but the distinction between frogs and toads is informal, not from taxonomy

Taxonomy is the practice and science of categorization or classification.

A taxonomy (or taxonomical classification) is a scheme of classification, especially a hierarchical classification, in which things are organized into groups or types. ...

or evolutionary history.

An adult frog has a stout body, protruding eye

Eyes are organs of the visual system. They provide living organisms with vision, the ability to receive and process visual detail, as well as enabling several photo response functions that are independent of vision. Eyes detect light and conv ...

s, anteriorly-attached tongue

The tongue is a muscular organ (anatomy), organ in the mouth of a typical tetrapod. It manipulates food for mastication and swallowing as part of the digestive system, digestive process, and is the primary organ of taste. The tongue's upper surfa ...

, limbs folded underneath, and no tail

The tail is the section at the rear end of certain kinds of animals’ bodies; in general, the term refers to a distinct, flexible appendage to the torso. It is the part of the body that corresponds roughly to the sacrum and coccyx in mammals, r ...

(the tail of tailed frogs is an extension of the male cloaca). Frogs have gland

In animals, a gland is a group of cells in an animal's body that synthesizes substances (such as hormones) for release into the bloodstream (endocrine gland) or into cavities inside the body or its outer surface (exocrine gland).

Structure

De ...

ular skin, with secretions ranging from distasteful to toxic. Their skin varies in colour from well-camouflage

Camouflage is the use of any combination of materials, coloration, or illumination for concealment, either by making animals or objects hard to see, or by disguising them as something else. Examples include the leopard's spotted coat, the ...

d dappled brown, grey and green to vivid patterns of bright red or yellow and black to show toxicity and ward off predators. Adult frogs live in fresh water and on dry land; some species are adapted for living underground or in trees.

Frogs typically lay their eggs in water. The eggs hatch into aquatic larva

A larva (; plural larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into adults. Animals with indirect development such as insects, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase of their life cycle.

The ...

e called tadpole

A tadpole is the larval stage in the biological life cycle of an amphibian. Most tadpoles are fully aquatic, though some species of amphibians have tadpoles that are terrestrial. Tadpoles have some fish-like features that may not be found i ...

s that have tails and internal gill

A gill () is a respiratory organ that many aquatic organisms use to extract dissolved oxygen from water and to excrete carbon dioxide. The gills of some species, such as hermit crabs, have adapted to allow respiration on land provided they are ...

s. They have highly specialized rasping mouth parts suitable for herbivorous, omnivorous or planktivorous

A planktivore is an aquatic organism that feeds on planktonic food, including zooplankton and phytoplankton. Planktivorous organisms encompass a range of some of the planet's smallest to largest multicellular animals in both the present day and ...

diets. The life cycle is completed when they metamorphose into adults. A few species deposit eggs on land or bypass the tadpole stage. Adult frogs generally have a carnivorous diet consisting of small invertebrates

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chordate ...

, but omnivorous species exist and a few feed on plant matter. Frog skin has a rich microbiome

A microbiome () is the community of microorganisms that can usually be found living together in any given habitat. It was defined more precisely in 1988 by Whipps ''et al.'' as "a characteristic microbial community occupying a reasonably well ...