Freya Von Moltke on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

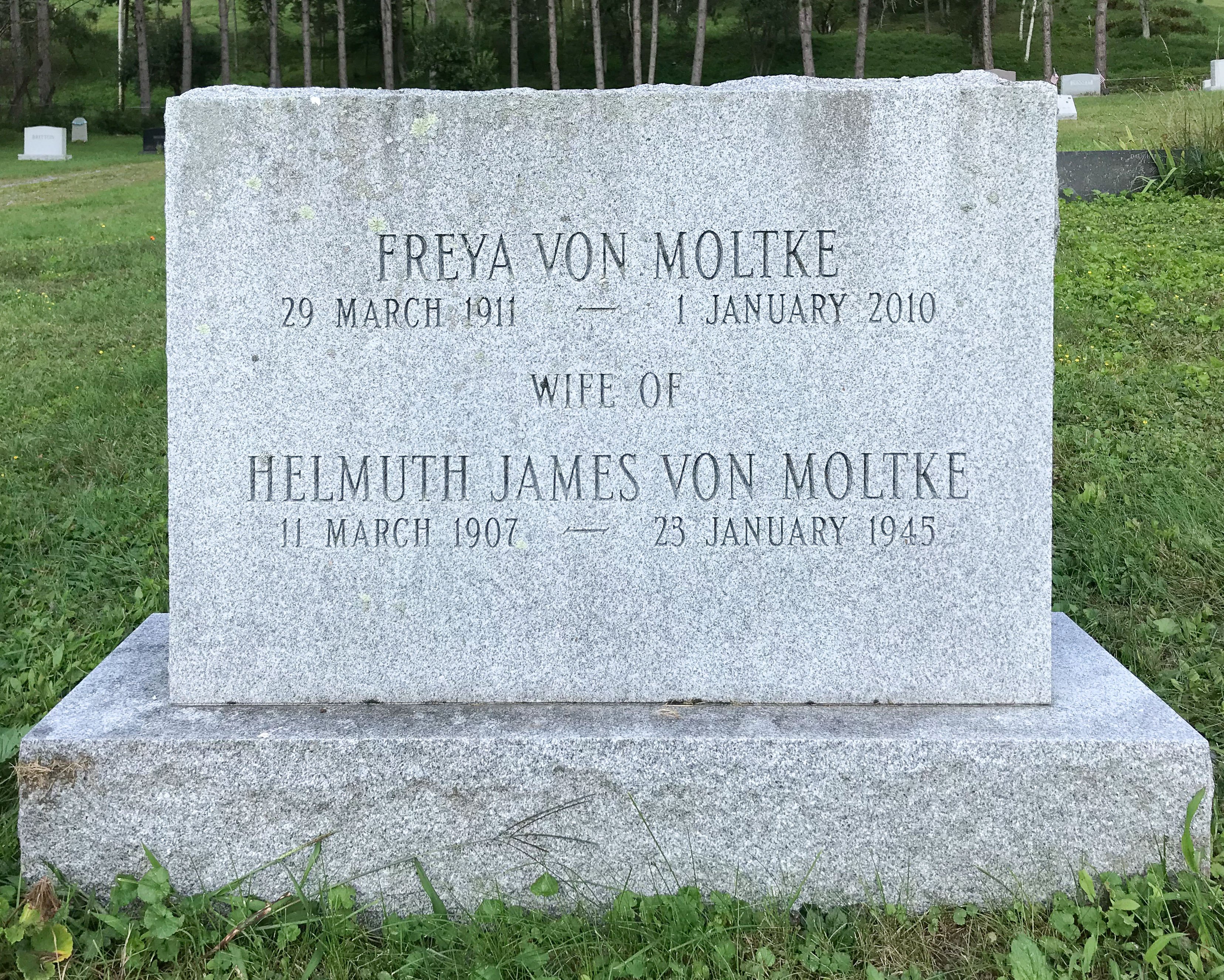

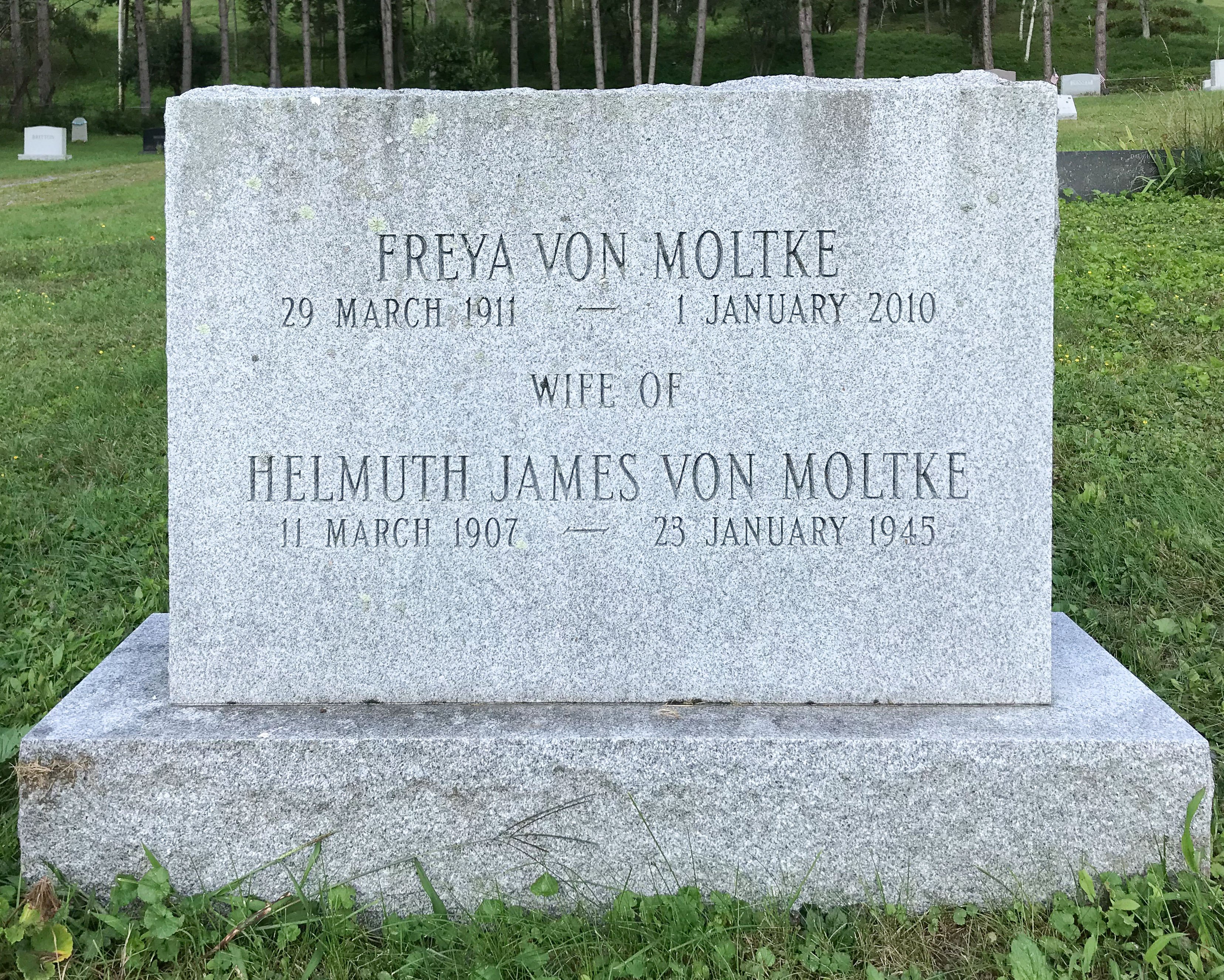

Freya von Moltke (née Deichmann; 29 March 1911 – 1 January 2010) was a German American lawyer and participant in the anti-

Moltke was born Freya Deichmann in

Moltke was born Freya Deichmann in

Following her law studies, Moltke visited summers at her husband's estate in Kreisau, where he had actively managed the farming activities, a pursuit atypical of a German nobleman, before retaining an overseer. She joined work on the farm, while her husband started an

Following her law studies, Moltke visited summers at her husband's estate in Kreisau, where he had actively managed the farming activities, a pursuit atypical of a German nobleman, before retaining an overseer. She joined work on the farm, while her husband started an

In Berlin Moltke's husband had a circle of acquaintances who opposed

In Berlin Moltke's husband had a circle of acquaintances who opposed

In 1999,

In 1999,

"Tribute to Freya von Moltke

accessed 28 January 2011

FemBiography

Website of the Freya von Moltke Foundation

– ''Daily Telegraph'' obituary {{DEFAULTSORT:Moltke, Freya von 1911 births 2010 deaths

Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

opposition group, the Kreisau Circle

The Kreisau Circle (German: ''Kreisauer Kreis'', ) (1940–1944) was a group of about twenty-five German dissidents in Nazi Germany led by Helmuth James von Moltke, who met at his estate in the rural town of Kreisau, Silesia. The circle was com ...

, with her husband, Helmuth James von Moltke

Helmuth James Graf von Moltke (11 March 1907 – 23 January 1945) was a German jurist who, as a draftee in the German Abwehr, acted to subvert German human-rights abuses of people in territories occupied by Germany during World War II. He ...

. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, her husband acted to subvert German human-rights abuses of people in territories occupied by Germany and became a founding member of the Kreisau Circle, whose members opposed the government of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

.

The Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

government executed her husband for treason, he having discussed with the Kreisau Circle group the prospects for a Germany based on moral and democratic principles that could develop after Hitler. Moltke preserved her husband's letters that detailed his activities during the war, and chronicled events from her perspective. She supported the founding of a center for international understanding at the former Moltke estate in Krzyżowa, Świdnica County

Krzyżowa (german: Kreisau, until 1930: ''Creisau'') is a village in the administrative district of Gmina Świdnica, within Świdnica County, Lower Silesian Voivodeship, in southwestern Poland.

It lies in the historic Lower Silesia region, ap ...

, Poland (formerly Kreisau, Germany).

Early life and education

Moltke was born Freya Deichmann in

Moltke was born Freya Deichmann in Cologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western States of Germany, state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 m ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, the daughter of banker Carl Theodor Deichmann and his wife, Ada Deichmann (née von Schnitzler). In 1930, she began studying law at the University of Bonn and attended seminars at the University of Breslau

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, th ...

. While working as a researcher she met her future husband Helmuth James von Moltke.

On 18 October 1931, the two married in her home town of Cologne. The couple initially resided in a modest house at the Moltke family's Kreisau estate in Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

(German: ''Schlesien''), then Germany, post WWII part of Poland. They moved to Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

so her husband could complete his legal training. She studied law in Berlin and received a Juris Doctor

The Juris Doctor (J.D. or JD), also known as Doctor of Jurisprudence (J.D., JD, D.Jur., or DJur), is a graduate-entry professional degree in law

and one of several Doctor of Law degrees. The J.D. is the standard degree obtained to practice law ...

degree from Friedrich Wilhelm University of Berlin in 1935.

Pre-war Kreisau, 1935-1939

international law

International law (also known as public international law and the law of nations) is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for ...

practice in Berlin and studied to become an English barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include taking cases in superior courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, researching law and ...

.

In 1933, Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

, became chancellor of Germany, which Moltke's husband foresaw would be a disaster for Germany, not the transitory figure that others expected. The Moltkes encouraged their overseer to join the Nazi Party to shield the community of Kreisau from government interference.

In 1937, Moltke gave birth to their first son, Helmuth Caspar. Thereafter, she lived at Kreisau year-round. Her husband inherited the Kreisau estate in 1939.

Wartime Kreisau 1939-1945

In 1939,World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

began with the German invasion of Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

and Moltke's husband was immediately "drafted at the beginning of the Polish campaign by the High Command of the Armed Forces, Counter-Intelligence Service, Foreign Division, as an expert in martial law and international public law."

In his travels through German-occupied countries, her husband observed many human rights abuses, which he attempted to thwart by insisting that Germany observe the Geneva Convention

upright=1.15, Original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are four treaties, and three additional protocols, that establish international legal standards for humanitarian treatment in war. The singular term ''Geneva Conven ...

and through local actions in creating more benign outcomes for local inhabitants, citing legal principles.

In October 1941, her husband wrote, "Certainly more than a thousand people are murdered in this way every day, and another thousand German men are habituated to murder... What shall I say when I am asked: And what did you do during that time?" In the same letter he said, "Since Saturday the Berlin Jews are being rounded up. Then they are sent off with what they can carry.... How can anyone know these things and walk around free?" In 1941 Moltke gave birth to their second son, Konrad, at Kreisau.

In Berlin Moltke's husband had a circle of acquaintances who opposed

In Berlin Moltke's husband had a circle of acquaintances who opposed Nazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

and who met frequently there, but on three occasions met at Kreisau. These three incidental gatherings were the basis for the term "Kreisau Circle

The Kreisau Circle (German: ''Kreisauer Kreis'', ) (1940–1944) was a group of about twenty-five German dissidents in Nazi Germany led by Helmuth James von Moltke, who met at his estate in the rural town of Kreisau, Silesia. The circle was com ...

." The meetings at Kreisau had an agenda of well-organized discussion topics, starting with relatively innocuous ones as cover. The topics of the first meeting of May, 1942 included the failure of German educational and religious institutions to fend off the rise of Nazism. The theme of the second meeting in the Fall of 1942 was on post-war reconstruction, assuming the likely defeat of Germany. This included both economic planning and self-government, developing a pan-European concept that pre-dated the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been des ...

. The third meeting, in June of 1943, addressed how to handle the legacy of Nazi war crimes after the fall of the dictatorship. These and other meetings resulted in "Principles for the New ost-NaziOrder" and "Directions to Regional Commissioners" that her husband asked Moltke to hide in a place that not even he knew.

On 19 January 1944, the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one organi ...

arrested Moltke's husband for warning an acquaintance of that person's impending arrest. She was allowed to visit him under benign conditions and found that he could continue to work and receive papers. On 20 July 1944 there was an attempt on Hitler's life, which the Gestapo used as a pretext to eliminate perceived opponents to the Nazi regime. In January 1945, Helmuth von Moltke was tried, convicted, and executed by a Gestapo " People's Court" for treason, having discussed with the Kreisau Circle group the prospects for a Germany based on moral and democratic principles that could develop after Hitler.

Fleeing Kreisau 1945

In the spring of 1945 Moltke and another Kreisau widow had evacuated their families toCzechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

to avoid the Russian offensive, which ultimately bypassed Kreisau. After the fall of Berlin on 2 May 1945, the Russians

, native_name_lang = ru

, image =

, caption =

, population =

, popplace =

118 million Russians in the Russian Federation (2002 ''Winkler Prins'' estimate)

, region1 =

, pop1 ...

sent a small detachment to occupy Kreisau. Using improvised notes in Russian and Czech, she obtained safe passage for both families to return to Kreisau from hiding. A Russian company was billeted at the Moltke estate to "supervise the harvest" during the summer of 1945. When the Poles began to occupy the small farms, vacated by Germans, the Russians became protectors of the occupants of the Moltke estate.

After a trip to Berlin, where she met Allen Dulles

Allen Welsh Dulles (, ; April 7, 1893 – January 29, 1969) was the first civilian Director of Central Intelligence (DCI), and its longest-serving director to date. As head of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) during the early Cold War, he ov ...

and received American rations for a difficult return trip to Silesia to retrieve her children, Moltke followed the advice of Gero von Schulze-Gaevernitz to leave Kreisau. Gaevernitz was an American officer, who came to inspect conditions in Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

. Moltke gave him for safekeeping the letters that her husband had written to her, which she had hidden from the Nazis in her beehives. Thanks to British friends of her husband, emissaries from the British Embassy in Poland arranged for her evacuation from Poland.

Transitions, 1945-2010

After World War II, Moltke publicized her husband's ideas and actions during the war, to serve as an example of principled opposition. As early as 1949 she traveled to the United States to lecture on "Germany: Past and present", "Germany: Totalitarianism versus democracy," "German youth and the new education", and "Women's position in the new Germany". After her escape from Silesia, Moltke moved toSouth Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

, where she settled with her two young sons, Caspar and Konrad. She worked as a social worker and a therapist for disabilities.

In 1956, unable to further tolerate Apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

, she returned to Berlin where she commenced her work in publicizing the Kreisau Circle. Her effort was supported by Eugen Gerstenmaier

Eugen Karl Albrecht Gerstenmaier (25 August 1906 – 13 March 1986, in Oberwinter) was a German Evangelical theologian, resistance fighter in the Third Reich, and a CDU politician. From 1954 to 1969, he served as President of the Bundestag. With ...

, then president of the Bundestag

The Bundestag (, "Federal Diet") is the German federal parliament. It is the only federal representative body that is directly elected by the German people. It is comparable to the United States House of Representatives or the House of Commons ...

, among others.

In 1960, she moved to Norwich, Vermont

Norwich is a town in Windsor County, in the U.S. state of Vermont. The population was 3,612 at the 2020 census. Home to some of the state of Vermont's wealthiest residents, the municipality is a commuter town for nearby Hanover, New Hampshir ...

, to join the social philosopher

Social philosophy examines questions about the foundations of social institutions, social behavior, and interpretations of society in terms of ethical values rather than empirical relations. Social philosophers emphasize understanding the social c ...

, Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy

Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy (July 6, 1888 – February 24, 1973) was a historian and social philosopher, whose work spanned the disciplines of history, theology, sociology, linguistics and beyond. Born in Berlin, Germany into a non-observant Jewish f ...

, who died in 1973. In 1986, at the age of 75, Moltke became a United States citizen

Citizenship of the United States is a legal status that entails Americans with specific rights, duties, protections, and benefits in the United States. It serves as a foundation of fundamental rights derived from and protected by the Constituti ...

to pursue her interest in participating in the U.S. political system.

Von Moltke has been a subject of many interviews and articles. In 1995, she told interviewer Alison Owings, "People who lived through the Nazi time, and who still live, who did not lose their lives because they were opposed, all had to make compromises."

With the reunification of Germany

German reunification (german: link=no, Deutsche Wiedervereinigung) was the process of re-establishing Germany as a united and fully sovereign state, which took place between 2 May 1989 and 15 March 1991. The day of 3 October 1990 when the Ge ...

, Moltke was supportive of transforming the former Moltke estate in Kreisau into a meeting place to promote German-Polish and European mutual understanding. Poland and Germany invested 30 million Deutsche Mark

The Deutsche Mark (; English: ''German mark''), abbreviated "DM" or "D-Mark" (), was the official currency of West Germany from 1948 until 1990 and later the unified Germany from 1990 until the adoption of the euro in 2002. In English, it was ...

in renovating the venue. It opened in 1998 as the Kreisau International Youth Center. In 2004, a fund was established to promote the long-term support of the meeting place and further the work done there.t As of 2007, Moltke actively supported this initiative as the honorary chair of the board of trustees of the Kreisau Foundation for European Understanding (the supporting entity for the Kreisau meeting site) and the Institute for Cultural Infrastructure, Sachsen in Görlitz.

Freya von Moltke died in Norwich, Vermont

Norwich is a town in Windsor County, in the U.S. state of Vermont. The population was 3,612 at the 2020 census. Home to some of the state of Vermont's wealthiest residents, the municipality is a commuter town for nearby Hanover, New Hampshir ...

on 1 January 2010 at the age of 98.

Recognition and legacy

In 1999,

In 1999, Dartmouth College

Dartmouth College (; ) is a private research university in Hanover, New Hampshire. Established in 1769 by Eleazar Wheelock, it is one of the nine colonial colleges chartered before the American Revolution. Although founded to educate Native A ...

awarded Moltke an honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters for her writings on the German opposition to Hitler during World War II. In the same year, she accepted the Bruecke Prize from the city of Görlitz, Germany, in recognition of her life's work.

Moltke met with three German Chancellors in connection with her life's work, Helmut Kohl

Helmut Josef Michael Kohl (; 3 April 1930 – 16 June 2017) was a German politician who served as Chancellor of Germany from 1982 to 1998 and Leader of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) from 1973 to 1998. Kohl's 16-year tenure is the longes ...

in 1998 to introduce him to the Kreisau International Youth Center built in Krzyżowa, Gerhard Schroeder Gerhard is a name of Germanic origin and may refer to:

Given name

* Gerhard (bishop of Passau) (fl. 932–946), German prelate

* Gerhard III, Count of Holstein-Rendsburg (1292–1340), German prince, regent of Denmark

* Gerhard Barkhorn (1919–19 ...

in 2004 at a wreath-laying ceremony to honor Nazi resisters, and Angela Merkel

Angela Dorothea Merkel (; ; born 17 July 1954) is a German former politician and scientist who served as Chancellor of Germany from 2005 to 2021. A member of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), she previously served as Leader of the Oppo ...

in 2007 at a commemoration of the birth centenary

{{other uses, Centennial (disambiguation), Centenary (disambiguation)

A centennial, or centenary in British English, is a 100th anniversary or otherwise relates to a century, a period of 100 years.

Notable events

Notable centennial events at ...

of her husband, Helmuth von Moltke, where Merkel described her husband as a symbol of "European courage".

Moltke's life served as the basis of a play by Marc Smith, ''A Journey to Kreisau''.

In January 2011, a documentary of her life, including her last interview in English, premiered at Goethe-Institut

The Goethe-Institut (, GI, en, Goethe Institute) is a non-profit German cultural association operational worldwide with 159 institutes, promoting the study of the German language abroad and encouraging international cultural exchange and ...

, Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

.Goethe-Institut Boston"Tribute to Freya von Moltke

accessed 28 January 2011

References

Further reading

In English

* * . * * * * *In German

* * * * * *External links

*FemBiography

Website of the Freya von Moltke Foundation

– ''Daily Telegraph'' obituary {{DEFAULTSORT:Moltke, Freya von 1911 births 2010 deaths

Freya

In Norse paganism, Freyja (Old Norse "(the) Lady") is a goddess associated with love, beauty, fertility, sex, war, gold, and seiðr (magic for seeing and influencing the future). Freyja is the owner of the necklace Brísingamen, rides a chario ...

University of Bonn alumni

German anti-war activists

German human rights activists

Women human rights activists

German non-fiction writers

German emigrants to the United States