French Revolutionary Legion on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The French Revolutionary Legion on the Mississippi was an American mercenary force commissioned by leaders of

The French Revolutionary Legion on the Mississippi was an American mercenary force commissioned by leaders of

The French Revolutionary Legion on the Mississippi was an American mercenary force commissioned by leaders of

The French Revolutionary Legion on the Mississippi was an American mercenary force commissioned by leaders of Revolutionary France

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

in 1793. Its purpose was to reassert French influence in the North American interior, which was lost in the Treaty of Paris (1763)

The Treaty of Paris, also known as the Treaty of 1763, was signed on 10 February 1763 by the kingdoms of Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain, Kingdom of France, France and Spanish Empire, Spain, with Kingdom of Portugal, Portugal in agree ...

.

French Revolutionary Legion

Edmond-Charles Genêt

Edmond-Charles Genêt (January 8, 1763July 14, 1834), also known as Citizen Genêt, was the French envoy to the United States appointed by the Girondins during the French Revolution. His actions on arriving in the United States led to a major po ...

, the French ambassador to the United States, created the French Revolutionary Legion in response to outrage against Spain. Genêt hoped to rally the ethnic French of the western United States, as well as traditional French allies among the Native American nations. Genêt sent André Michaux

André Michaux, also styled Andrew Michaud, (8 March 174611 October 1802) was a French botanist and explorer. He is most noted for his study of North American flora. In addition Michaux collected specimens in England, Spain, France, and even Per ...

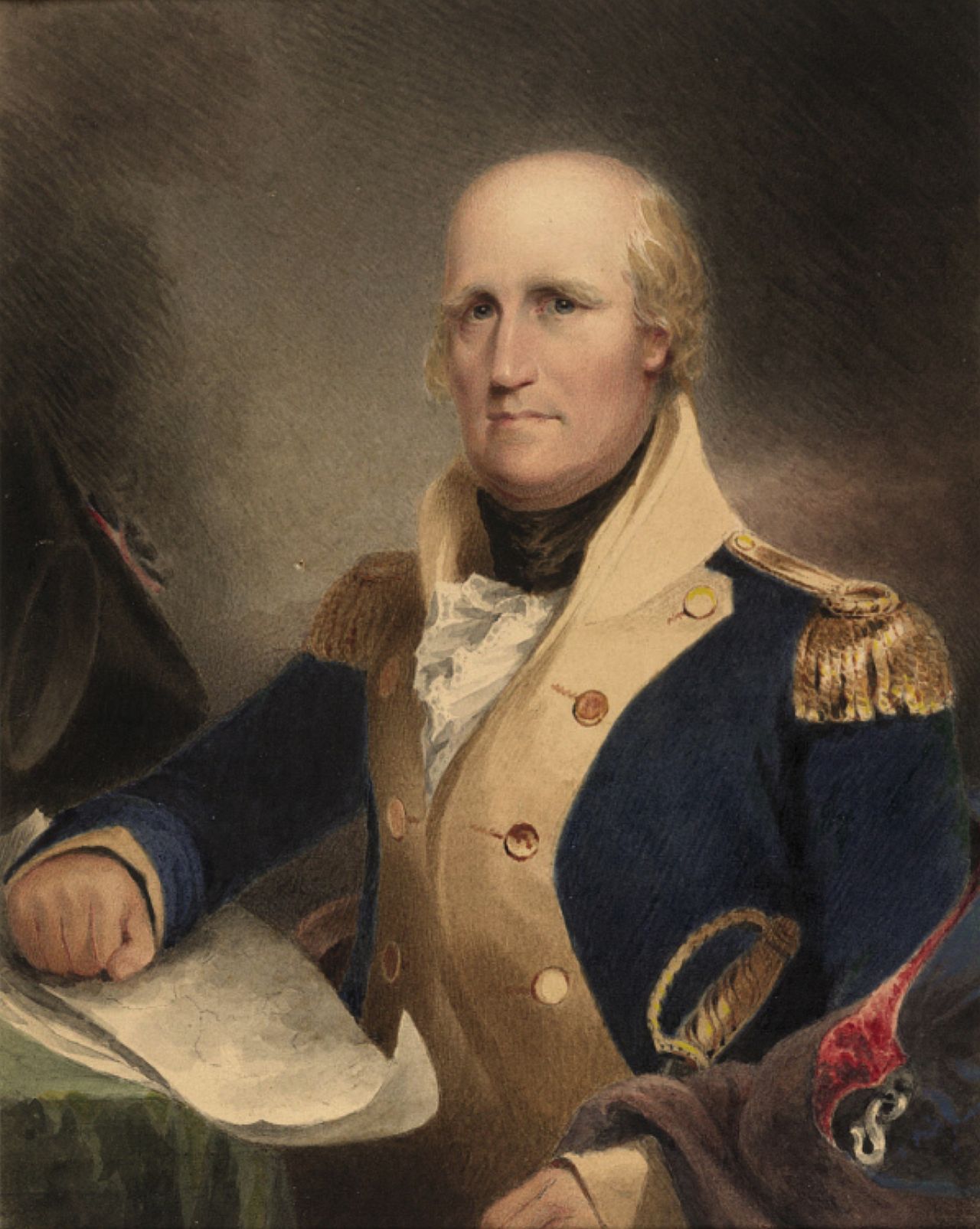

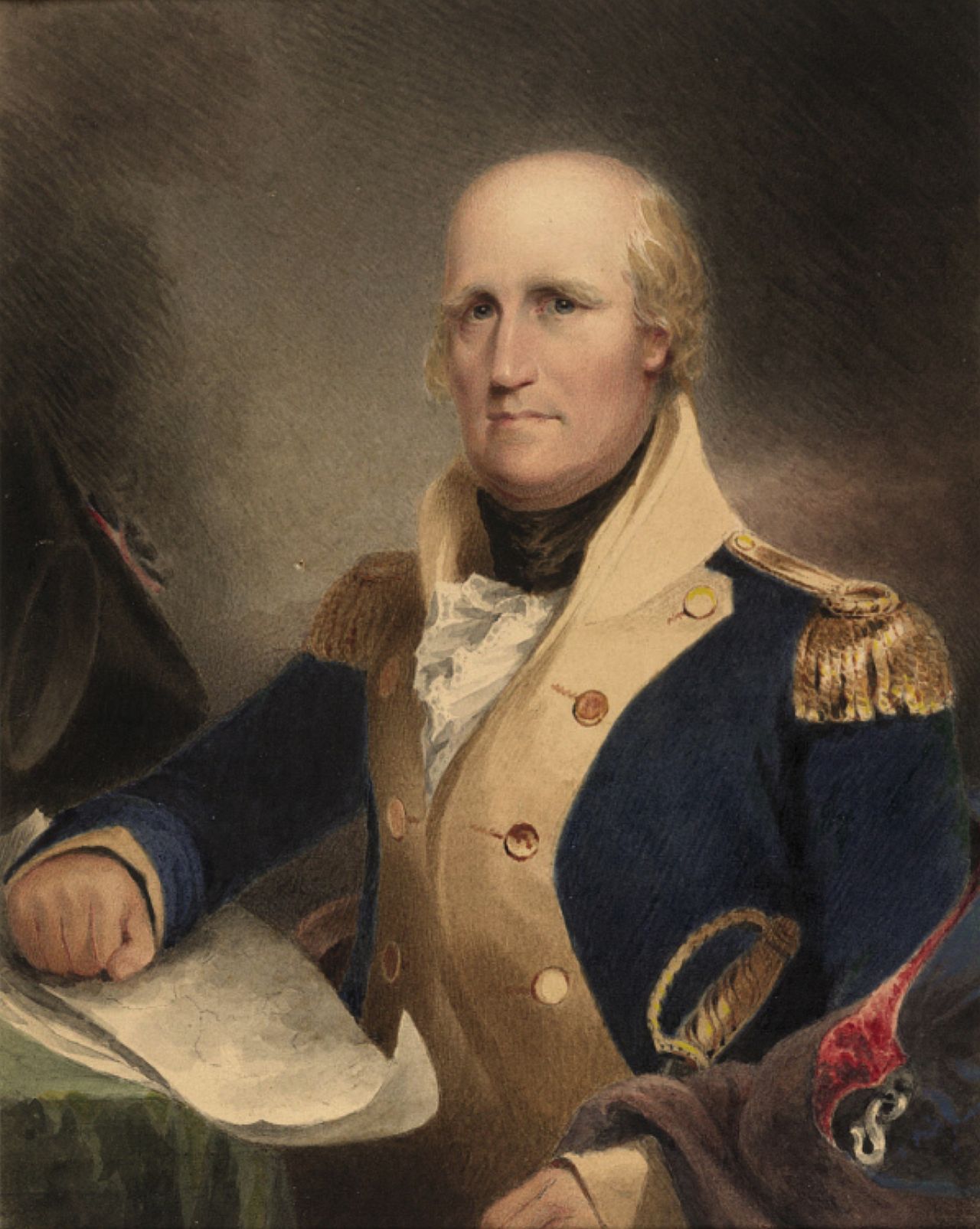

and two French artillery officers to Kentucky and commissioned George Rogers Clark

George Rogers Clark (November 19, 1752 – February 13, 1818) was an American surveyor, soldier, and militia officer from Virginia who became the highest-ranking American patriot military officer on the northwestern frontier during the Ame ...

as "Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

in the Armies of France and Commander-in-chief of the French Revolutionary Legion on the Mississippi River". Clark began to organize a campaign to seize New Madrid, St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

, Natchez Natchez may refer to:

Places

* Natchez, Alabama, United States

* Natchez, Indiana, United States

* Natchez, Louisiana, United States

* Natchez, Mississippi, a city in southwestern Mississippi, United States

* Grand Village of the Natchez, a site o ...

, and New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

, in Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

, in order to gain free navigation on the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

. Genêt dispatched the ''Little Democrat'' to establish a blockade at New Orleans. Clark won the tacit support of Kentucky governor Isaac Shelby

Isaac Shelby (December 11, 1750 – July 18, 1826) was the first and fifth Governor of Kentucky and served in the state legislatures of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic an ...

, who when pressed by the Washington administration to arrest Clark, responded with doubts that he had "any legal authority to restrain or to punish them." Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

officially protested the Legion's violation of U.S. neutrality, but suggested that the campaign would be in the best interests of the United States. Clark advertised in the Centinel of the Northwest Territory that anyone who served with the French Legion would be granted 1,000 to 3,000 acres of conquered lands, depending on the years of service; and all plunder would be divided. Clark was able to raise two infantry regiments, and was prepared to launch his campaign when it was cancelled by another French official.

President George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

was angered by Genêt's lack of diplomatic tact, and demanded his recall in December 1793. In February 1794, a new ambassador from France, Jean Antoine Joseph Fauchet Jean Antoine Joseph Fauchet (1761, Saint-Quentin – 1834, Paris) was a French diplomat, and French ambassador to the United States.

He studied law. When the French Revolution broke out, he published pamphlets praising the event. He was a secreta ...

, arrived in Philadelphia with an arrest warrant for Genêt. On March 4, Fauchet issued an order cancelling the expedition into Louisiana. Clark and Shelby continued their preparations, however, so President Washington issued a Proclamation of Neutrality

The Proclamation of Neutrality was a formal announcement issued by U.S. President George Washington on April 22, 1793, that declared the nation neutral in the conflict between France and Great Britain. It threatened legal proceedings against any ...

on March 24 which forbid Americans from invading Spain. On March 31, Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Henry Knox

Henry Knox (July 25, 1750 – October 25, 1806), a Founding Father of the United States, was a senior general of the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War, serving as chief of artillery in most of Washington's campaigns. Following the ...

ordered General Anthony Wayne

Anthony Wayne (January 1, 1745 – December 15, 1796) was an American soldier, officer, statesman, and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. He adopted a military career at the outset of the American Revolutionary War, where his mil ...

to build a fortification on the site of Fort Massac

Fort Massac (or Fort Massiac) was a French colonial and early National-era fort on the Ohio River in Massac County, Illinois, United States.

Its site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1971.

History

The Spanish explorer ...

to stop the expedition. Wayne sent a company of infantry and some artillery to Fort Massac in May after receiving word that Spain had sent five gunboats up the Mississippi to the Ohio River. The French government revoked the commissions granted to the Americans for the war against Spain. By July, the French Revolutionary Legion had dispersed. Clark's planned campaign collapsed, and he was unable to convince the French to reimburse him for his expenses.

Brigadier General James Wilkinson

James Wilkinson (March 24, 1757 – December 28, 1825) was an American soldier, politician, and double agent who was associated with several scandals and controversies.

He served in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, b ...

, 2nd in command of the Legion of the United States

The Legion of the United States was a reorganization and extension of the Continental Army from 1792 to 1796 under the command of Major General Anthony Wayne. It represented a political shift in the new United States, which had recently adopte ...

, claimed credit for undermining Clark and for preventing supplies from being shipped down the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

. He submitted receipts of $8,640 to Spanish Governor Carondelet for his efforts.

France issued a new commission to Clark in 1796. The plan to invade Louisiana was revisited in 1798, but failed to yield any results. The French First Republic

In the history of France, the First Republic (french: Première République), sometimes referred to in historiography as Revolutionary France, and officially the French Republic (french: République française), was founded on 21 September 1792 ...

, under Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

, gained possession of the territory in the 1800 Third Treaty of San Ildefonso

The Third Treaty of San Ildefonso was a secret agreement signed on 1 October 1800 between the Spanish Empire and the French Republic by which Spain agreed in principle to exchange its North American colony of Louisiana for territories in Tuscany. ...

. It was purchased by the United States in 1803.

American Revolutionary Legion

In October 1793, a similar force was raised in South Carolina. French ConsulMichel Ange Bernard Mangourit

Michel Ange Bernard de Mangourit (21 August 1752, Rennes – 17 February 1829) was a French diplomat, and French ambassador to the United States from 1796 to 1800, during the Quasi-War.

Life

He was the son of Bernard de Mangourit and Marguerite- ...

wanted to capture Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

from Spain and then assist Clark in the invasion of Louisiana. He commissioned William Tate as a French Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

to lead this force. Tate's deputy commander was Stephen Drayton, the personal secretary to Governor William Moultrie

William Moultrie (; November 23, 1730 – September 27, 1805) was an American planter and politician who became a general in the American Revolutionary War. As colonel leading a state militia, in 1776 he prevented the British from taking Charle ...

. Tate was instructed to recruit from outside the United States, but he recruited from the region of the Carolinas

The Carolinas are the U.S. states of North Carolina and South Carolina, considered collectively. They are bordered by Virginia to the north, Tennessee to the west, and Georgia to the southwest. The Atlantic Ocean is to the east.

Combining Nort ...

, especially rural settlers. He is known to have attracted sixty-six officers, but claimed to have raised more than 2,000 volunteers. Like Clark, Tate's commission was rescinded by Fauchet. South Carolina threatened to arrest Tate for treason, and he fled to France in 1795, where he was given command of the Légion Noire

La Légion noire (The Black Legion) was a military unit of the French Revolutionary Army. It took part in what was the unsuccessful last invasion of Britain in February 1797, at the time of writing.

The Legion was created on the orders of Genera ...

during the 1797 invasion of Britain that ended with the Battle of Fishguard

The Battle of Fishguard was a military invasion of Great Britain by Revolutionary France during the War of the First Coalition. The brief campaign, on 22–24 February 1797, is the most recent landing on British soil by a hostile foreign force ...

.

References

Sources

* * * * * * * {{cite book , last=Winkler , first=John F , title=Fallen Timbers 1794: The US Army's first victory , author-link= , publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing

Bloomsbury Publishing plc is a British worldwide publishing house of fiction and non-fiction. It is a constituent of the FTSE SmallCap Index. Bloomsbury's head office is located in Bloomsbury, an area of the London Borough of Camden. It has a U ...

, year=2013 , isbn= 978-1-7809-6377-8

1790s in Kentucky

1793 in the United States

1794 in the United States

Presidency of George Washington

Volunteer units and formations of the French Revolutionary Wars