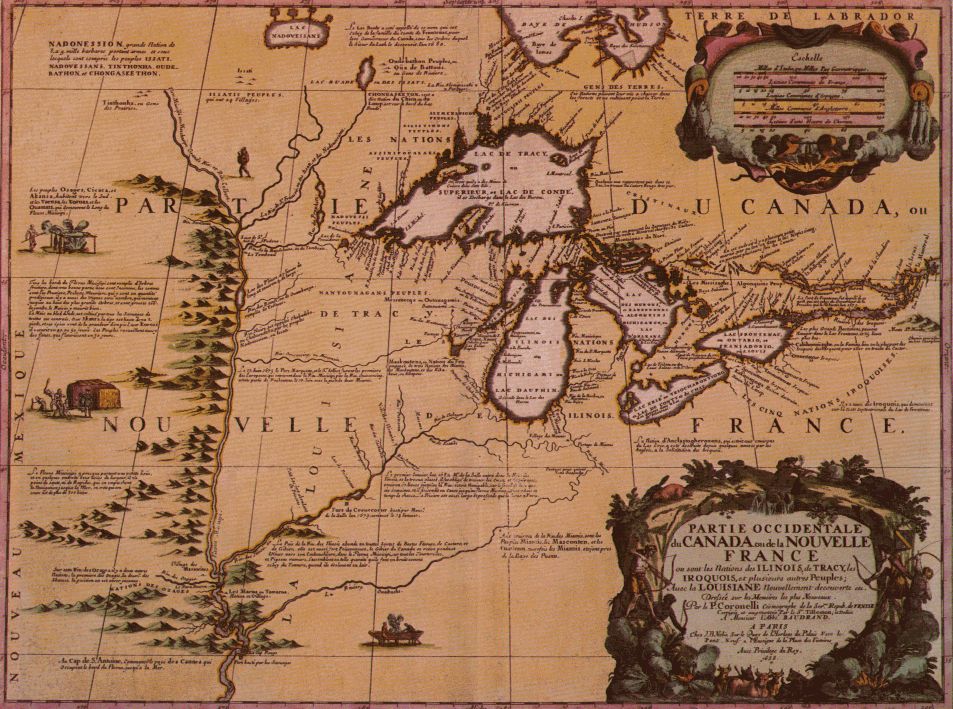

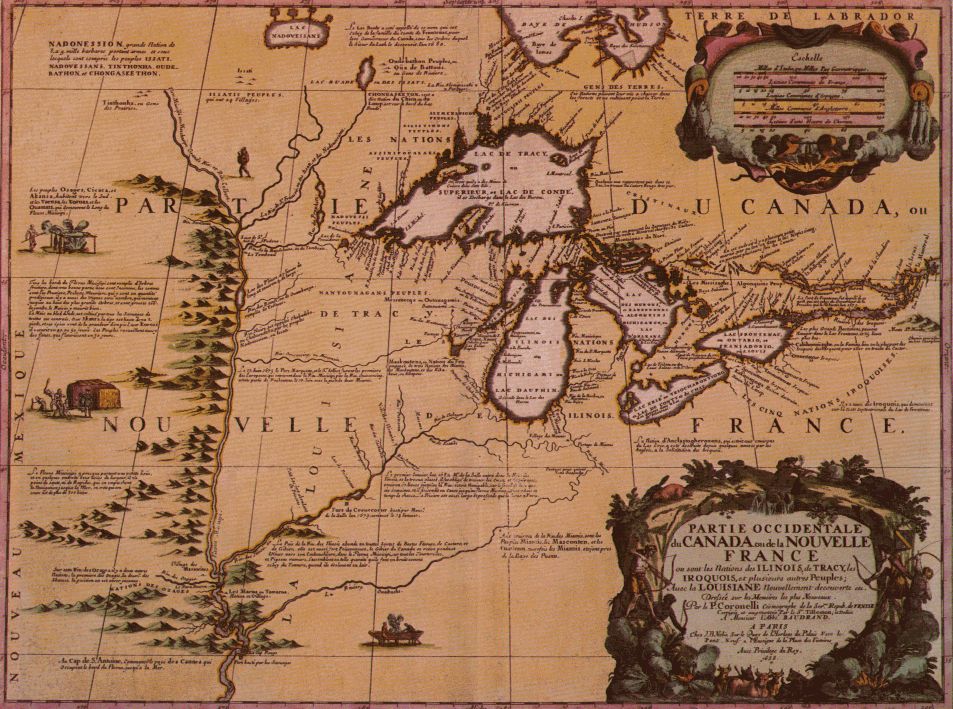

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

in

North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

, beginning with the exploration of the

Gulf of Saint Lawrence

, image = Baie de la Tour.jpg

, alt =

, caption = Gulf of St. Lawrence from Anticosti National Park, Quebec

, image_bathymetry = Golfe Saint-Laurent Depths fr.svg

, alt_bathymetry = Bathymetry ...

by

Jacques Cartier

Jacques Cartier ( , also , , ; br, Jakez Karter; 31 December 14911 September 1557) was a French-Breton maritime explorer for France. Jacques Cartier was the first European to describe and map the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and the shores of th ...

in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

and

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

in 1763 under the

Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

.

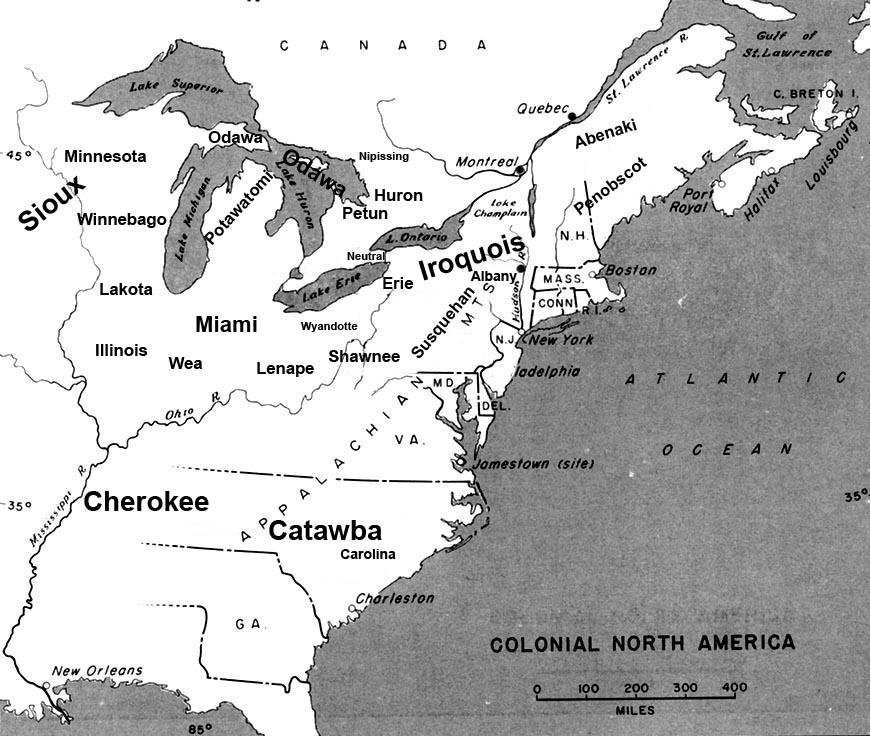

The vast territory of ''New France'' consisted of five colonies at its peak in 1712, each with its own administration:

Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

, the most developed colony, was divided into the districts of

Québec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Government of Canada, Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is ...

,

Trois-Rivières

Trois-Rivières (, – 'Three Rivers') is a city in the Mauricie administrative region of Quebec, Canada, at the confluence of the Saint-Maurice River, Saint-Maurice and Saint Lawrence River, Saint Lawrence rivers, on the north shore of the Sain ...

, and

Montréal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple-p ...

;

Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay ( crj, text=ᐐᓂᐯᒄ, translit=Wînipekw; crl, text=ᐐᓂᐹᒄ, translit=Wînipâkw; iu, text=ᑲᖏᖅᓱᐊᓗᒃ ᐃᓗᐊ, translit=Kangiqsualuk ilua or iu, text=ᑕᓯᐅᔭᕐᔪᐊᖅ, translit=Tasiujarjuaq; french: b ...

;

Acadie in the northeast;

Plaisance on the island of

Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

; and

Louisiane

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is border ...

.

It extended from Newfoundland to the

Canadian Prairies

The Canadian Prairies (usually referred to as simply the Prairies in Canada) is a region in Western Canada. It includes the Canadian portion of the Great Plains and the Prairie Provinces, namely Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. These provin ...

and from Hudson Bay to the

Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an oceanic basin, ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of ...

, including all the

Great Lakes of North America

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lakes ...

.

In the 16th century, the lands were used primarily to draw from the wealth of natural resources such as furs through trade with the various indigenous peoples. In the seventeenth century, successful settlements began in Acadia and in Quebec. In the

1713 Treaty of Utrecht

The Peace of Utrecht was a series of peace treaties signed by the belligerents in the War of the Spanish Succession, in the Dutch city of Utrecht between April 1713 and February 1715. The war involved three contenders for the vacant throne o ...

, France ceded to Great Britain its claims over mainland Acadia, Hudson Bay, and Newfoundland. France established the colony of

Île Royale

The Salvation Islands (french: Îles du Salut, so called because the missionaries went there to escape plague on the mainland; sometimes mistakenly called Safety Islands) are a group of small islands of volcano, volcanic origin about off the coa ...

on

Cape Breton Island

Cape Breton Island (french: link=no, île du Cap-Breton, formerly '; gd, Ceap Breatainn or '; mic, Unamaꞌki) is an island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.

The island accounts for 18. ...

, where they built the

Fortress of Louisbourg

The Fortress of Louisbourg (french: Forteresse de Louisbourg) is a National Historic Site and the location of a one-quarter partial reconstruction of an 18th-century French fortress at Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia. Its two sie ...

.

The population rose slowly but steadily. In 1754, New France's population consisted of 10,000

Acadian

The Acadians (french: Acadiens , ) are an ethnic group descended from the French who settled in the New France colony of Acadia during the 17th and 18th centuries. Most Acadians live in the region of Acadia, as it is the region where the de ...

s, 55,000 ''

Canadiens

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fren ...

'', and about 4,000 settlers in

upper and lower Louisiana; 69,000 in total. The British expelled the Acadians in the

Great Upheaval

The Expulsion of the Acadians, also known as the Great Upheaval, the Great Expulsion, the Great Deportation, and the Deportation of the Acadians (french: Le Grand Dérangement or ), was the forced removal, by the British, of the Acadian peo ...

from 1755 to 1764, which has been remembered on

July 28

Events Pre-1600

* 1364 – Troops of the Republic of Pisa and the Republic of Florence clash in the Battle of Cascina.

* 1540 – Henry VIII of England marries his fifth wife, Catherine Howard, on the same day his former Chancellor, T ...

each year since 2003. Their descendants are dispersed in the

Maritime provinces

The Maritimes, also called the Maritime provinces, is a region of Eastern Canada consisting of three provinces: New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. The Maritimes had a population of 1,899,324 in 2021, which makes up 5.1% of Ca ...

of Canada and in

Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and north ...

and

Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

, with small populations in

Chéticamp, Nova Scotia

Chéticamp (; ) is an unincorporated place on the Cabot Trail on the west coast of Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia, Canada. It is a local service centre. A majority of the population are Acadians. Together with its smaller neighbour, Saint-Joseph ...

and the

Magdalen Islands

The Magdalen Islands (french: Îles de la Madeleine ) are a small archipelago in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence with a land area of . While part of the Province of Quebec, the islands are in fact closer to the Maritime provinces and Newfoundland th ...

. Some also went to France.

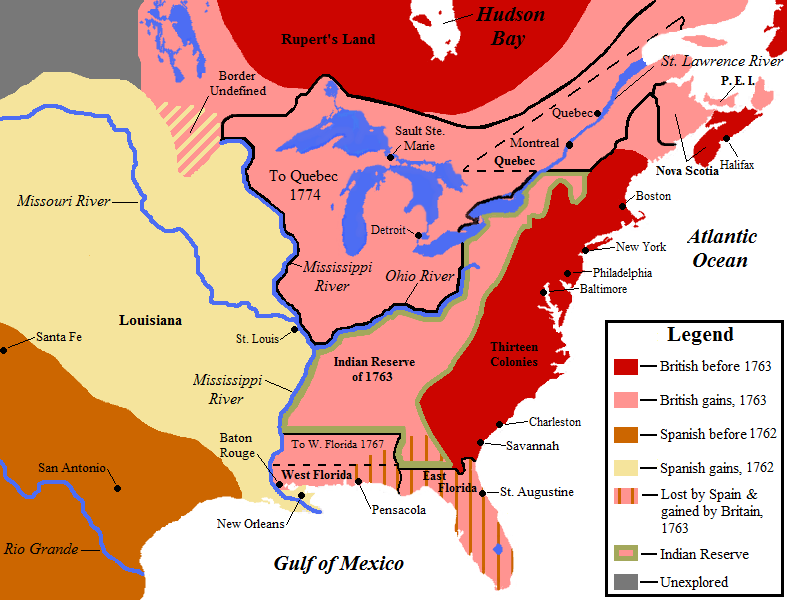

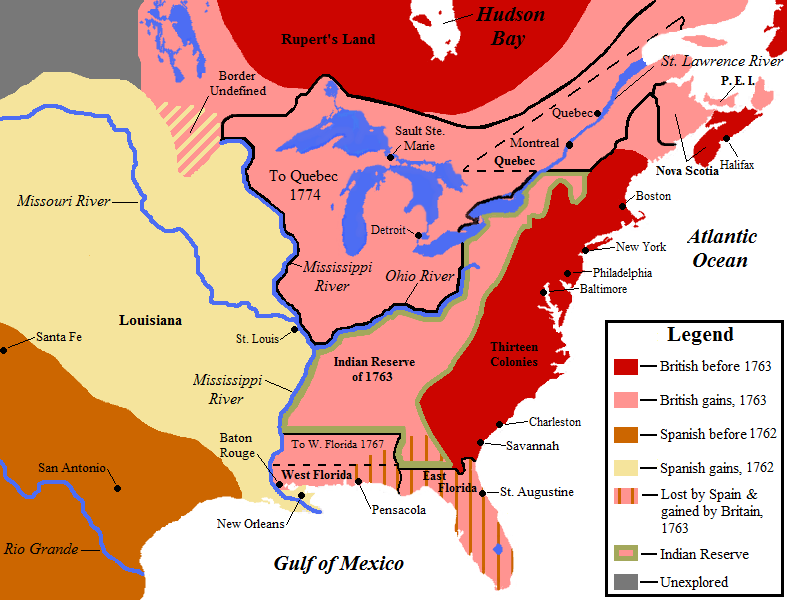

After the

Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

(which included the

French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

in America), France ceded the rest of New France to Great Britain and Spain in the

Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

of 1763 (except the islands of

Saint Pierre and Miquelon

Saint Pierre and Miquelon (), officially the Territorial Collectivity of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon (french: link=no, Collectivité territoriale de Saint-Pierre et Miquelon ), is a self-governing territorial overseas collectivity of France in t ...

). Britain acquired Canada, Acadia, and French Louisiana east of the

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

, except for the

Île d'Orléans

Île d'Orléans (; en, Island of Orleans) is an island located in the Saint Lawrence River about east of downtown Quebec City, Quebec, Canada. It was one of the first parts of the province to be colonized by the French, and a large percentage ...

, which was granted to Spain with the territory to the west. In 1800, Spain returned

its portion of Louisiana to France under the secret

Treaty of San Ildefonso, and

Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

sold it to the United States in the

Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

of 1803, permanently ending French colonial efforts on the American mainland.

New France eventually became absorbed within the United States and Canada, with the only vestige of French rule being the tiny islands of

Saint Pierre and Miquelon

Saint Pierre and Miquelon (), officially the Territorial Collectivity of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon (french: link=no, Collectivité territoriale de Saint-Pierre et Miquelon ), is a self-governing territorial overseas collectivity of France in t ...

. In the United States, the legacy of New France includes

numerous place names as well as

small pockets of French-speaking communities.

Early exploration (1523–1650s)

Around 1523, the

Florentine navigator

Giovanni da Verrazzano

Giovanni da Verrazzano ( , , often misspelled Verrazano in English; 1485–1528) was an Italian ( Florentine) explorer of North America, in the service of King Francis I of France.

He is renowned as the first European to explore the Atlantic ...

convinced King

Francis I Francis I or Francis the First may refer to:

* Francesco I Gonzaga (1366–1407)

* Francis I, Duke of Brittany (1414–1450), reigned 1442–1450

* Francis I of France (1494–1547), King of France, reigned 1515–1547

* Francis I, Duke of Saxe-Lau ...

to commission an expedition to find a western route to

Cathay

Cathay (; ) is a historical name for China that was used in Europe. During the early modern period, the term ''Cathay'' initially evolved as a term referring to what is now Northern China, completely separate and distinct from China, which ...

(China). Late that year, Verrazzano set sail in

Dieppe

Dieppe (; Norman: ''Dgieppe'') is a coastal commune in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France.

Dieppe is a seaport on the English Channel at the mouth of the river Arques. A regular ferry service runs to Newha ...

, crossing the Atlantic on a small

caravel

The caravel (Portuguese: , ) is a small maneuverable sailing ship used in the 15th century by the Portuguese to explore along the West African coast and into the Atlantic Ocean. The lateen sails gave it speed and the capacity for sailing win ...

with 50 men.

After exploring the coast of the present-day

Carolinas

The Carolinas are the U.S. states of North Carolina and South Carolina, considered collectively. They are bordered by Virginia to the north, Tennessee to the west, and Georgia to the southwest. The Atlantic Ocean is to the east.

Combining Nort ...

early the following year, he headed north along the coast, eventually anchoring in the

Narrows

A narrows or narrow (used interchangeably but usually in the plural form), is a restricted land or water passage. Most commonly a narrows is a strait, though it can also be a water gap.

A narrows may form where a stream passes through a tilted ...

of

New York Bay

New York Bay is the large tidal body of water in the New York–New Jersey Harbor Estuary where the Hudson River, Raritan River, and Arthur Kill empty into the Atlantic Ocean between Sandy Hook and Rockaway Point.

Geography

New York Bay is usu ...

.

The first European to visit the site of present-day New York, Verrazzano named it

Nouvelle-Angoulême

The written history of New York City began with the first European explorer, the Italian Giovanni da Verrazzano in 1524. European settlement began with the Dutch in 1608.

The "Sons of Liberty" campaigned against British authority in New York Ci ...

in honour of the

king

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

, the former count of

Angoulême

Angoulême (; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''Engoulaeme''; oc, Engoleime) is a communes of France, commune, the Prefectures of France, prefecture of the Charente Departments of France, department, in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region of southwestern Franc ...

. Verrazzano's voyage convinced the king to seek to establish a colony in the newly discovered land. Verrazzano gave the names ''Francesca'' and ''Nova Gallia'' to that land between

New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Am ...

(Mexico) and English Newfoundland.

In 1534,

Jacques Cartier

Jacques Cartier ( , also , , ; br, Jakez Karter; 31 December 14911 September 1557) was a French-Breton maritime explorer for France. Jacques Cartier was the first European to describe and map the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and the shores of th ...

planted a cross in the

Gaspé Peninsula

The Gaspé Peninsula, also known as Gaspesia (; ), is a peninsula along the south shore of the Saint Lawrence River that extends from the Matapedia Valley in Quebec, Canada, into the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. It is separated from New Brunswick o ...

and claimed the land in the name of

King Francis I

Francis I (french: François Ier; frm, Francoys; 12 September 1494 – 31 March 1547) was King of France from 1515 until his death in 1547. He was the son of Charles, Count of Angoulême, and Louise of Savoy. He succeeded his first cousin once ...

.

It was the first province of New France. The first settlement of 400 people, Fort

Charlesbourg-Royal

Fort Charlesbourg Royal (1541—1543) is a National Historic Site in the Cap-Rouge neighbourhood of Quebec City, Quebec, Canada. Established by Jacques Cartier in 1541, it was France's first attempt at a colony in North America, and was abandon ...

(present-day

Quebec City

Quebec City ( or ; french: Ville de Québec), officially Québec (), is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Quebec. As of July 2021, the city had a population of 549,459, and the Communauté métrop ...

), was attempted in 1541 but lasted only two years.

French fishing fleets continued to sail to the Atlantic coast and into the St. Lawrence River, making alliances with Canadian

First Nations

First Nations or first peoples may refer to:

* Indigenous peoples, for ethnic groups who are the earliest known inhabitants of an area.

Indigenous groups

*First Nations is commonly used to describe some Indigenous groups including:

**First Natio ...

that became important once France began to occupy the land. French merchants soon realized the St. Lawrence region was full of valuable

fur

Fur is a thick growth of hair that covers the skin of mammals. It consists of a combination of oily guard hair on top and thick underfur beneath. The guard hair keeps moisture from reaching the skin; the underfur acts as an insulating blanket t ...

-bearing animals, especially the

beaver

Beavers are large, semiaquatic rodents in the genus ''Castor'' native to the temperate Northern Hemisphere. There are two extant species: the North American beaver (''Castor canadensis'') and the Eurasian beaver (''C. fiber''). Beavers ar ...

, which were becoming rare in

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

. Eventually, the French crown decided to colonize the territory to secure and expand its influence in America.

Another early French attempt at settlement in North America took place in 1564 at

Fort Caroline

Fort Caroline was an attempted French colonial settlement in Florida, located on the banks of the St. Johns River in present-day Duval County. It was established under the leadership of René Goulaine de Laudonnière on 22 June, 1564, followin ...

, now

Jacksonville, Florida

Jacksonville is a city located on the Atlantic coast of northeast Florida, the most populous city proper in the state and is the largest city by area in the contiguous United States as of 2020. It is the seat of Duval County, with which the ...

. Intended as a haven for

Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

s, Caroline was founded under the leadership of

René Goulaine de Laudonnière

Rene Goulaine de Laudonnière (c. 1529–1574) was a French Huguenot explorer and the founder of the French colony of Fort Caroline in what is now Jacksonville, Florida. Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, a Huguenot, sent Jean Ribault and Laudonnière ...

and

Jean Ribault

Jean Ribault (also spelled ''Ribaut'') (1520 – October 12, 1565) was a French naval officer, navigator, and a colonizer of what would become the southeastern United States. He was a major figure in the French attempts to colonize Florida. A H ...

. It was sacked by the

Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Cana ...

led by

Pedro Menéndez de Avilés

Pedro Menéndez de Avilés (; ast, Pedro (Menéndez) d'Avilés; 15 February 1519 – 17 September 1574) was a Spanish admiral, explorer and conquistador from Avilés, in Asturias, Spain. He is notable for planning the first regular trans-oceani ...

who slaughtered every Protestant there and then established the settlement of

St. Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Afri ...

on 20 September 1565.

Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17th and early ...

and

Canada (New France)

The colony of Canada was a French colony within the larger territory of New France. It was claimed by France in 1535 during the second voyage of Jacques Cartier, in the name of the French king, Francis I. The colony remained a French territory u ...

were inhabited by

indigenous

Indigenous may refer to:

*Indigenous peoples

*Indigenous (ecology), presence in a region as the result of only natural processes, with no human intervention

*Indigenous (band), an American blues-rock band

*Indigenous (horse), a Hong Kong racehorse ...

nomadic

Algonquian peoples

The Algonquian are one of the most populous and widespread North American native language groups. Historically, the peoples were prominent along the Atlantic Coast and into the interior along the Saint Lawrence River and around the Great Lakes. T ...

and sedentary

Iroquoian

The Iroquoian languages are a language family of indigenous peoples of North America. They are known for their general lack of labial consonants. The Iroquoian languages are polysynthetic and head-marking.

As of 2020, all surviving Iroquoian la ...

peoples. These lands were full of unexploited and valuable natural resources, which attracted all of Europe. By the 1580s, French trading companies had been set up, and ships were contracted to bring back furs. Much of what transpired between the indigenous population and their European visitors around that time is not known, for lack of historical records.

[

Other attempts at establishing permanent settlements were also failures. In 1598, a French trading post was established on ]Sable Island

Sable Island (french: île de Sable, literally "island of sand") is a small Canadian island situated southeast of Halifax, Nova Scotia, and about southeast of the closest point of mainland Nova Scotia in the North Atlantic Ocean. The island i ...

, off the coast of Acadia, but was unsuccessful. In 1600, a trading post was established at Tadoussac

Tadoussac () is a village in Quebec, Canada, at the confluence of the Saguenay and Saint Lawrence rivers. The indigenous Innu call the place ''Totouskak'' (plural for ''totouswk'' or ''totochak'') meaning "bosom", probably in reference to the t ...

, but only five settlers survived the winter.[

In 1604, a settlement was founded at ]Île-Saint-Croix

Saint Croix Island (french: Île Sainte-Croix), long known to locals as Dochet Island, is a small uninhabited island in Maine near the mouth of the Saint Croix River that forms part of the Canada–United States border separating Maine from New ...

on Baie François (Bay of Fundy

The Bay of Fundy (french: Baie de Fundy) is a bay between the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, with a small portion touching the U.S. state of Maine. It is an arm of the Gulf of Maine. Its extremely high tidal range is the hi ...

), which was moved to Port-Royal Port Royal is the former capital city of Jamaica.

Port Royal or Port Royale may also refer to:

Institutions

* Port-Royal-des-Champs, an abbey near Paris, France, which spawned influential schools and writers of the 17th century

** Port-Royal Abb ...

in 1605.[ It was abandoned in 1607, re-established in 1610, and destroyed in 1613, after which settlers moved to other nearby locations, creating settlements that were collectively known as ]Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17th and early ...

, and the settlers as Acadians

The Acadians (french: Acadiens , ) are an ethnic group descended from the French who settled in the New France colony of Acadia during the 17th and 18th centuries. Most Acadians live in the region of Acadia, as it is the region where the des ...

.[

]

Foundation of Quebec City (1608)

In 1608, King Henry IV sponsored

In 1608, King Henry IV sponsored Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Mons

Pierre Dugua de Mons (or Du Gua de Monts; c. 1558 – 1628) was a French merchant, explorer and colonizer. A Calvinist, he was born in the Château de Mons, in Royan, Saintonge (southwestern France) and founded the first permanent French sett ...

and Samuel de Champlain

Samuel de Champlain (; Fichier OrigineFor a detailed analysis of his baptismal record, see RitchThe baptism act does not contain information about the age of Samuel, neither his birth date nor his place of birth. – 25 December 1635) was a Fre ...

as founders of the city of Quebec with 28 men. This was the second permanent French settlement in the colony of Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

. Colonization was slow and difficult. Many settlers died early because of harsh weather and diseases. In 1630, there were only 103 colonists living in the settlement, but by 1640, the population had reached 355.

Champlain allied himself with the Algonquin

Algonquin or Algonquian—and the variation Algonki(a)n—may refer to:

Languages and peoples

*Algonquian languages, a large subfamily of Native American languages in a wide swath of eastern North America from Canada to Virginia

**Algonquin la ...

and Montagnais peoples in the area, who were at war with the Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

, as soon as possible. In 1609, Champlain and two French companions accompanied his Algonquin, Montagnais, and Huron

Huron may refer to:

People

* Wyandot people (or Wendat), indigenous to North America

* Wyandot language, spoken by them

* Huron-Wendat Nation, a Huron-Wendat First Nation with a community in Wendake, Quebec

* Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi ...

allies south from the St. Lawrence Valley to Lake Champlain

, native_name_lang =

, image = Champlainmap.svg

, caption = Lake Champlain-River Richelieu watershed

, image_bathymetry =

, caption_bathymetry =

, location = New York/Vermont in the United States; and Quebec in Canada

, coords =

, type =

, ...

. He participated decisively in a battle against the Iroquois there, killing two Iroquois chiefs with the first shot of his arquebus

An arquebus ( ) is a form of long gun that appeared in Europe and the Ottoman Empire during the 15th century. An infantryman armed with an arquebus is called an arquebusier.

Although the term ''arquebus'', derived from the Dutch word ''Haakbus ...

. This military engagement against the Iroquois solidified Champlain's status with New France's Huron and Algonquin allies, enabling him to maintain bonds essential to New France's interests in the fur trade. Champlain also arranged to have young French men live with local indigenous people, to learn their language and customs and help the French adapt to life in North America. These ''

Champlain also arranged to have young French men live with local indigenous people, to learn their language and customs and help the French adapt to life in North America. These ''coureurs des bois

A coureur des bois (; ) or coureur de bois (; plural: coureurs de(s) bois) was an independent entrepreneurial French-Canadian trader who travelled in New France and the interior of North America, usually to trade with First Nations peoples by e ...

'' ("runners of the woods"), including Étienne Brûlé

Étienne Brûlé (; – c. June 1633) was the first European explorer to journey beyond the St. Lawrence River into what is now known as Canada. He spent much of his early adult life among the Hurons, and mastered their language and learned ...

, extended French influence south and west to the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lakes ...

and among the Huron tribes who lived there. Ultimately, for the better part of a century, the Iroquois and French clashed in a series of attacks and reprisals.English colonies

The English overseas possessions, also known as the English colonial empire, comprised a variety of overseas territories that were colonised, conquered, or otherwise acquired by the former Kingdom of England during the centuries before the Ac ...

to the south were much more populous and wealthier. Cardinal Richelieu

Armand Jean du Plessis, Duke of Richelieu (; 9 September 1585 – 4 December 1642), known as Cardinal Richelieu, was a French clergyman and statesman. He was also known as ''l'Éminence rouge'', or "the Red Eminence", a term derived from the ...

, adviser to Louis XIII

Louis XIII (; sometimes called the Just; 27 September 1601 – 14 May 1643) was King of France from 1610 until his death in 1643 and King of Navarre (as Louis II) from 1610 to 1620, when the crown of Navarre was merged with the French crown ...

, wished to make New France as significant as the English colonies. In 1627, Richelieu founded the Company of One Hundred Associates

The Company of One Hundred Associates ( French: formally the Compagnie de la Nouvelle-France, or colloquially the Compagnie des Cent-Associés or Compagnie du Canada), or Company of New France, was a French trading and colonization company ch ...

to invest in New France, promising land parcels to hundreds of new settlers and to turn Canada into an important mercantile and farming colony.Governor of New France The governor of New France was the viceroy of the King of France in North America. A French nobleman, he was appointed to govern the colonies of New France, which included Canada, Acadia and Louisiana. The residence of the Governor was at the Chatea ...

and forbade non-Roman Catholics

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

to live there. Consequently, any Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

emigrants to New France were forced to convert to Catholicism, prompting many of them to relocate to the English colonies instead.Recollets

The Recollects (french: Récollets) were a French reform branch of the Friars Minor, a Franciscan order. Denoted by their gray habits and pointed hoods, the Recollects took vows of poverty and devoted their lives to prayer, penance, and spirit ...

and the Jesuits

The Society of Jesus ( la, Societas Iesu; abbreviation: SJ), also known as the Jesuits (; la, Iesuitæ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

, became firmly established in the territory. Richelieu also introduced the seigneurial system Seigneurial system may refer to:

* Manorialism - the socio-economic system of the Middle Ages and Early Modern period

* Seigneurial system of New France

The manorial system of New France, known as the seigneurial system (french: Régime seigneu ...

, a semi-feudal system of farming based on ribbon farm

Ribbon farms (also known as strip farms, long-lot farms, or just long lots) are long, narrow land divisions for farming, usually lined up along a waterway. In some instances, they line a road.

Background

Ribbon or strip farms were prevalent in ...

s that remained a characteristic feature of the St. Lawrence valley until the 19th century. While Richelieu's efforts did little to increase the French presence in New France, they did pave the way for the success of later efforts.Trois-Rivières

Trois-Rivières (, – 'Three Rivers') is a city in the Mauricie administrative region of Quebec, Canada, at the confluence of the Saint-Maurice River, Saint-Maurice and Saint Lawrence River, Saint Lawrence rivers, on the north shore of the Sain ...

, which Laviolette did in 1634. Champlain died in 1635.

On 23 September 1646, under the command of Pierre LeGardeur, Le Cardinal arrived to Quebec with Jules (Gilles) Trottier II and his family. Le Cardinal, commissioned by the Communauté des Habitants, had arrived from La Rochelle, France

La Rochelle (, , ; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''La Rochéle''; oc, La Rochèla ) is a city on the west coast of France and a seaport on the Bay of Biscay, a part of the Atlantic Ocean. It is the capital of the Charente-Maritime department. With 7 ...

. Communauté des Habitants at the time of Trottier traded fur primarily. On 4 July 1646, by Pierre Teuleron, sieur de Repentigny, granted Trottier land in La Rochelle to build and develop New France, under the authorization Jacques Le Neuf de la Poterie.

Royal takeover and attempts to settle

In 1650, New France had seven hundred colonists and Montreal had only a few dozen settlers. Because the First Nations people did most of the work of beaver hunting, the company needed few French employees. The sparsely-populated New France almost fell to hostile Iroquois forces completely as well. In 1660, settler

In 1650, New France had seven hundred colonists and Montreal had only a few dozen settlers. Because the First Nations people did most of the work of beaver hunting, the company needed few French employees. The sparsely-populated New France almost fell to hostile Iroquois forces completely as well. In 1660, settler Adam Dollard des Ormeaux

Adam Dollard des Ormeaux (July 23, 1635 – May 21, 1660) is an iconic figure in the history of New France. Arriving in the colony in 1658, Dollard was appointed the position of garrison commander of the fort of Ville-Marie (now Montreal). ...

led a Canadian and Huron militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

against a much larger Iroquois force; none of the Canadians survived, although they did turn back the Iroquois invasion.

In 1627, Quebec had only eighty-five French colonists and was easily overwhelmed two years later when three English privateers plundered the settlement. In 1663, New France finally became more secure when Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Vers ...

made it a royal province, taking control away from the Company of One Hundred Associates

The Company of One Hundred Associates ( French: formally the Compagnie de la Nouvelle-France, or colloquially the Compagnie des Cent-Associés or Compagnie du Canada), or Company of New France, was a French trading and colonization company ch ...

. In the same year the Société Notre-Dame de Montréal

The Société Notre-Dame de Montréal, otherwise known as the ''Société de Notre-Dame de Montréal pour la conversion des Sauvages de la Nouvelle-France'', was a religious organisation responsible for founding Ville-Marie, the original name for ...

ceded its possessions to the Seminaire de Saint-Sulpice.

The Crown paid for transatlantic passages and offered other incentives to those willing to move to New France as well, after which the population of New France grew to three thousand.

In 1665, Louis XIV sent a French garrison, the Carignan-Salières Regiment

The Carignan-Salières Regiment was a Piedmont French military unit formed by merging two other regiments in 1659. They were led by the new Governor, Daniel de Rémy de Courcelles, and Lieutenant-General Alexandre de Prouville, Sieur de Tracy. ...

, to Quebec. The colonial government was reformed along the lines of the government of France, with the Governor General and Intendant

An intendant (; pt, intendente ; es, intendente ) was, and sometimes still is, a public official, especially in France, Spain, Portugal, and Latin America. The intendancy system was a centralizing administrative system developed in France. In ...

subordinate to the French Minister of the Marine. In 1665, Jean Talon

Jean Talon, Count d'Orsainville (; January 8, 1626 – November 23, 1694) was a French colonial administrator who served as the first Intendant of New France. Talon was appointed by King Louis XIV and his minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to ...

Minister of the Marine accepted an appointment from Jean-Baptiste Colbert

Jean-Baptiste Colbert (; 29 August 1619 – 6 September 1683) was a French statesman who served as First Minister of State from 1661 until his death in 1683 under the rule of King Louis XIV. His lasting impact on the organization of the countr ...

as the first Intendant of New France. These reforms limited the power of the Bishop of Quebec, who had held the greatest amount of power after the death of Champlain.

Talon tried reforming the seigneurial system by forcing the ''seigneurs'' to reside on their land and limiting the size of the ''seigneuries,'' intending to make more land available to new settlers. Talon's attempts failed since very few settlers arrived and the various industries he established failed to surpass the importance of the fur trade.

Settlers and their families

The first settler was brought to Quebec by Champlainthe apothecary

The first settler was brought to Quebec by Champlainthe apothecary Louis Hébert

Louis Hébert (c. 1575 – 25 January 1627) is widely considered the first European apothecary in the region that would later become Canada, as well as the first European to farm in said region. He was born around 1575 at 129 de la rue Saint ...

and his family, of Paris. They came expressly to settle, stay in one place to make the New France settlement function. Waves of recruits came in response to the requests for men with specific skills, like farming, apothecaries, blacksmiths. As couples married, cash incentives to have large families were put in place, and were effective.

To strengthen and make the colony the centre of France's colonial empire, Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Vers ...

decided to send single women, between 15 and 30 years old and known as the King's Daughters

The King's Daughters (french: filles du roi or french: filles du roy, label=none in the spelling of the era) is a term used to refer to the approximately 800 young French women who immigrated to New France between 1663 and 1673 as part of a pr ...

, or, in French, ''les filles du roi'', to New France. He also paid for their passages and granted goods or money as their dowries if or when they married. Approximately 800 girls and women went there during 1663–1673. The King's Daughters

The King's Daughters (french: filles du roi or french: filles du roy, label=none in the spelling of the era) is a term used to refer to the approximately 800 young French women who immigrated to New France between 1663 and 1673 as part of a pr ...

found husbands among the male settlers new lives for themselves within two years of their respective immigrations. They came on their own choice, many because they could not contract favorable marriages in the French social hierarchy. Primarily, they came from Parisian, Norman, and west-central commoner families. By 1672, the population of New France had risen to 6,700 people, a marked increase from the population of 3,200 people in 1663. At the same time, the government encouraged marriages with the indigenous peoples and welcomed

At the same time, the government encouraged marriages with the indigenous peoples and welcomed indentured servants

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment, ...

, or ''engagés'' sent to New France. The women there contributed to establishing family life, civil society, and rapid demographic growth significantly.[

Besides household duties, some women participated in the fur trade, the major source of money in New France. They worked at home alongside their husbands or fathers as merchants, clerks, and provisioners. Some were widows who took over their husbands' roles. Some even became independent and active entrepreneurs.

]

Settlements in Louisiana

The French extended their territorial claim to the south and to the west of the

The French extended their territorial claim to the south and to the west of the American colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th centur ...

late in the 17th century, naming it for King Louis XIV, as La Louisiane

Louisiana (french: La Louisiane; ''La Louisiane Française'') or French Louisiana was an administrative district of New France. Under French control from 1682 to 1769 and 1801 (nominally) to 1803, the area was named in honor of King Louis XIV, ...

. In 1682, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle (; November 22, 1643 – March 19, 1687), was a 17th-century French explorer and fur trader in North America. He explored the Great Lakes region of the United States and Canada, the Mississippi River, ...

explored the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

Valley and the Mississippi River Valley

The Mississippi embayment is a physiographic feature in the south-central United States, part of the Mississippi Alluvial Plain. It is essentially a northward continuation of the fluvial sediments of the Mississippi River Delta to its conflu ...

, and he claimed the entire territory for France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

as far south as the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an oceanic basin, ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of ...

.Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

. The colony was devastated by disease, and the surviving settlers were killed in 1688, in an attack by the area's indigenous population

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

. Other parts of Louisiana were settled and developed with success, such as and southern Illinois

Southern Illinois, also known as Little Egypt, is the southern third of Illinois, principally along and south of Interstate 64. Although part of a Midwestern United States, Midwestern state, this region is aligned in culture more with that of th ...

, leaving a strong French influence in these areas long after the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

.

Many strategic fort

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

s were built there, under the orders of Governor Louis de Buade de Frontenac

Louis de Buade, Comte de Frontenac et de Palluau (; 22 May 162228 November 1698) was a French soldier, courtier, and Governor General of New France in North America from 1672 to 1682, and again from 1689 to his death in 1698. He established a nu ...

. Forts were also built in the older portions of New France that had not yet been settled. Many of these forts were garrisoned by the Troupes de la Marine, the only regular soldiers in New France between 1683 and 1755.

Growth of the settlements

The European population grew slowly under French rule,

The European population grew slowly under French rule,[ Yves Landry says, "Canadians had an exceptional diet for their time." The ]1666 census of New France

The 1666 census of New France was the first census conducted in Canada (and also North America). It was organized by Jean Talon, the first Intendant of New France, between 1665 and 1666.

Talon and the French Minister of the Marine Jean-Baptiste C ...

was the first census conducted in North America.Jean Talon

Jean Talon, Count d'Orsainville (; January 8, 1626 – November 23, 1694) was a French colonial administrator who served as the first Intendant of New France. Talon was appointed by King Louis XIV and his minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to ...

, the first Intendant of New France The Intendant of New France was an administrative position in the French colony of New France. He controlled the colony's entire civil administration. He gave particular attention to settlement and economic development, and to the administration of ...

, between 1665 and 1666.[ According to Talon's census there were 3,215 people in New France, comprising 538 separate families.][

By the early 1700s the New France settlers were well established along the ]Saint Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connectin ...

and Acadian Peninsula

The Acadian Peninsula (french: Péninsule acadienne) is situated in the northeastern corner of New Brunswick, Canada, encompassing portions of Gloucester and Northumberland Counties. It derives its name from the large Acadian population locate ...

with a population around 15,000 to 16,000. The first population figures for Acadia are from 1671, which enumerated only 450 people.Chemin du Roy

The Chemin du Roy (; French for "King's Highway" or "King's Road") is a historic road along the north shore of the St. Lawrence River in Quebec. The road begins in Repentigny and extends almost eastward towards Quebec City, its eastern terminus ...

'') was built between Montreal and Quebec to encourage faster trade. The shipping industry also flourished as new ports were built and old ones were upgraded. The number of colonists greatly increased. By 1720, Canada had become a self-sufficient colony with a population of 24,594.Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo language, Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, Historical region, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known ...

, Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

, Île-de-France

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 = +01:00

, timezone1_DST = CEST

, utc_offset1_DST = +02:00

, blank_name_sec1 = Gross regional product

, blank_info_sec1 = Ranked 1st

, bla ...

, Poitou-Charentes

Poitou-Charentes (; oc, Peitau-Charantas; Poitevin-Saintongese: ) is a former administrative region on the southwest coast of France. It is part of the new region Nouvelle-Aquitaine. It comprises four departments: Charente, Charente-Maritime, D ...

and Pays de la Loire

Pays de la Loire (; ; br, Broioù al Liger) is one of the 18 regions of France, in the west of the mainland. It was created in the 1950s to serve as a zone of influence for its capital, Nantes, one of a handful of "balancing metropolises" ().

...

) the population of Canada increased to 55,000 according to the last French census of 1754.

Fur trade and economy

According to the

According to the staples thesis In economic development, the staples thesis is a theory of export-led growth. The theory "has its origins in research into Canadian social, political, and economic history carried out in Canadian universities...by members of what were then known as ...

, the economic development of New France was marked by the emergence of successive economies based on staple commodities, each of which dictated the political and cultural settings of the time. During the 16th and early 17th centuries New France's economy was heavily centered on its Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

fisheries. This would change in the later half of the 17th and 18th centuries as French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

settlement penetrated further into the continental interior. Here French economic interests would shift and concentrate itself on the development of the North American fur trade

The North American fur trade is the commercial trade in furs in North America. Various Indigenous peoples of the Americas traded furs with other tribes during the pre-Columbian era. Europeans started their participation in the North American fur ...

. It would soon become the new staple good that would strengthen and drive New France's economy, in particular that of Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-most populous city in Canada and List of towns in Quebec, most populous city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian ...

, for the next century.

The trading post of Ville-Marie, established on the current island of Montreal, quickly became the economic hub for the French fur trade. It achieved this in great part due to its particular location along the St. Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connecting ...

. From here a new economy emerged, one of size and density that provided increased economic opportunities for the inhabitants of New France. In December 1627 the Company of New France

The Company of One Hundred Associates (French: formally the Compagnie de la Nouvelle-France, or colloquially the Compagnie des Cent-Associés or Compagnie du Canada), or Company of New France, was a French trading and colonization company cha ...

was recognized and given commercial rights to the gathering and export of furs

Fur is a thick growth of hair that covers the skin of mammals. It consists of a combination of oily guard hair on top and thick underfur beneath. The guard hair keeps moisture from reaching the skin; the underfur acts as an insulating blanket t ...

from French territories. By trading with various indigenous populations and securing the main markets its power grew steadily for the next decade. As a result, it was able to set specific price points for furs and other valuable goods, often doing so to protect its economic hegemony over other trading partners and other areas of the economy.

The fur trade itself was based on a commodity

In economics, a commodity is an economic good, usually a resource, that has full or substantial fungibility: that is, the market treats instances of the good as equivalent or nearly so with no regard to who produced them.

The price of a comm ...

of small bulk but high value. Because of this it managed to attract increased attention and/or input capital that would otherwise be intended for other areas of the economy. The Montreal area witnessed a stagnant agricultural sector; it remained for the most part subsistence orientated with little or no trade purposes outside of the French colony

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the ''metropole, metropolit ...

. This was a prime example of the handicapping effect the fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the mos ...

had on its neighbouring areas of the economy

An economy is an area of the production, distribution and trade, as well as consumption of goods and services. In general, it is defined as a social domain that emphasize the practices, discourses, and material expressions associated with the ...

.

Nonetheless, by the beginning of the 1700s the economic prosperity the fur trade stimulated slowly transformed Montreal. Economically, it was no longer a town of small traders or of fur fairs but rather a city of merchants and of bright lights. The primary sector of the

Nonetheless, by the beginning of the 1700s the economic prosperity the fur trade stimulated slowly transformed Montreal. Economically, it was no longer a town of small traders or of fur fairs but rather a city of merchants and of bright lights. The primary sector of the fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the mos ...

, the act of acquiring and the selling of the furs, quickly promoted the growth of complementary second and tertiary sectors of the economy. For instance a small number of tanneries was established in Montreal as well as a larger number of inns, taverns and markets that would support the growing number of inhabitants whose livelihood depended on the fur trade. Already by 1683 there were well over 140 families and there may have been as many as 900 people living in Montreal.

The founding of the Compagnie des Indes in 1718, once again highlighted the economic importance of the fur trade. This merchant association, like its predecessor the Compagnie des Cent Associes, regulated the fur trade to the best of its abilities imposing price points, supporting government sale taxes and combating black market practices. However, by the middle half of the 18th century the fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the mos ...

was in a slow decline.Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-most populous city in Canada and List of towns in Quebec, most populous city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian ...

and New France altogether; many began trading with either British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

or Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

merchants to the south.

Coureurs des bois and voyageurs

The

The coureurs des bois

A coureur des bois (; ) or coureur de bois (; plural: coureurs de(s) bois) was an independent entrepreneurial French-Canadian trader who travelled in New France and the interior of North America, usually to trade with First Nations peoples by e ...

were responsible for starting the flow of trade from Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-most populous city in Canada and List of towns in Quebec, most populous city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian ...

, carrying French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

goods into upper territories while indigenous people were bringing down their furs

Fur is a thick growth of hair that covers the skin of mammals. It consists of a combination of oily guard hair on top and thick underfur beneath. The guard hair keeps moisture from reaching the skin; the underfur acts as an insulating blanket t ...

. The coureurs traveled with intermediate trading tribes, and found that they were anxious to prevent French access to the more distant fur-hunting tribes. Still, the coureurs kept thrusting outwards using the Ottawa River

The Ottawa River (french: Rivière des Outaouais, Algonquin: ''Kichi-Sìbì/Kitchissippi'') is a river in the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Quebec. It is named after the Algonquin word 'to trade', as it was the major trade route of Eastern ...

as their initial step upon the journey and keeping Montreal as their starting point.Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

. It was for this reason that Montreal and the Ottawa River was a central location of indigenous warfare and rivalry.

Montreal faced difficulties by having too many coureurs out in the woods. The furs coming down were causing an oversupply on the markets of Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

. This challenged the coureurs trade because they so easily evaded controls, monopolies, and taxation, and additionally because the coureurs trade was held to debauch both French and various indigenous groups. The coureur debauched Frenchmen by accustoming them to fully live with indigenous, and indigenous by trading on their desire for alcohol.colony

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the ''metropole, metropolit ...

, and in 1678, it was confirmed by a General Assembly that the trade was to be made in public so as to better assure the safety of the indigenous population. It was also forbidden to take spirits inland to trade with indigenous groups. However these restrictions on the coureurs, for a variety of reasons, never worked. The fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the mos ...

remained dependent on spirits, and increasingly in the hands of the coureurs who journeyed north in search of furs.voyageurs

The voyageurs (; ) were 18th and 19th century French Canadians who engaged in the transporting of furs via canoe during the peak of the North American fur trade. The emblematic meaning of the term applies to places (New France, including the ' ...

.

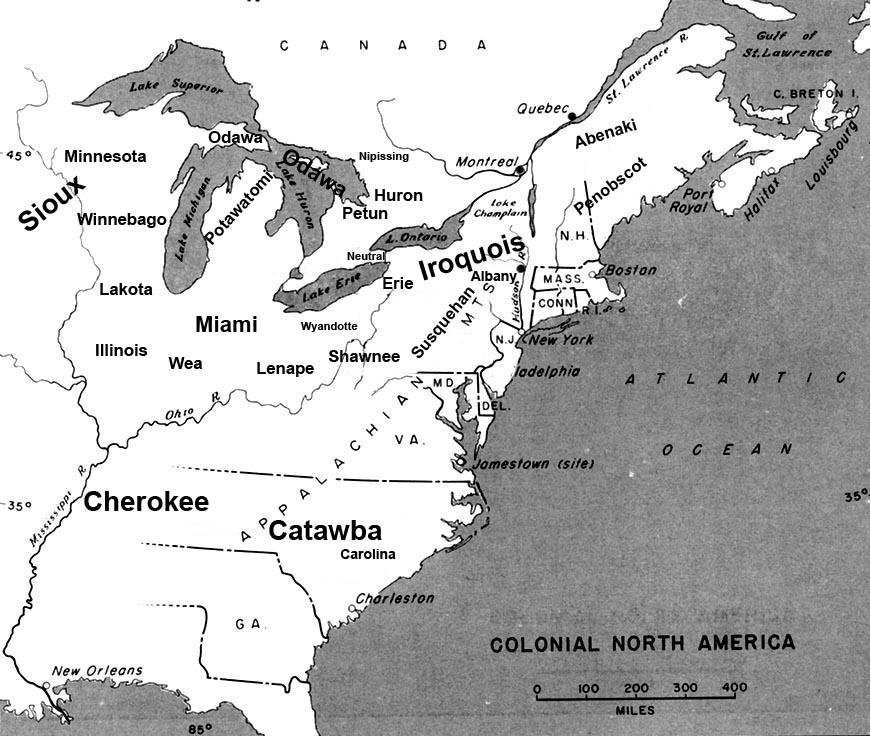

Indigenous peoples

The two factions, Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

and French, were constantly at war with one another until the Great Peace of Montréal in 1701. The relationship between the Iroquois and the French first began in 1609. The relationship between the French and Iroquois began violently. As Samuel De Champlain

Samuel de Champlain (; Fichier OrigineFor a detailed analysis of his baptismal record, see RitchThe baptism act does not contain information about the age of Samuel, neither his birth date nor his place of birth. – 25 December 1635) was a Fre ...

travelled from the St. Lawrence Valley

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connecting t ...

, accompanied by his Algonquin

Algonquin or Algonquian—and the variation Algonki(a)n—may refer to:

Languages and peoples

*Algonquian languages, a large subfamily of Native American languages in a wide swath of eastern North America from Canada to Virginia

**Algonquin la ...

, Montagnais, and Huron

Huron may refer to:

People

* Wyandot people (or Wendat), indigenous to North America

* Wyandot language, spoken by them

* Huron-Wendat Nation, a Huron-Wendat First Nation with a community in Wendake, Quebec

* Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi ...

allies, the killing of three Iroquoian chiefs on Lake Champlain

, native_name_lang =

, image = Champlainmap.svg

, caption = Lake Champlain-River Richelieu watershed

, image_bathymetry =

, caption_bathymetry =

, location = New York/Vermont in the United States; and Quebec in Canada

, coords =

, type =

, ...

was Champlain’s war of fortifying his stance with his fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the mos ...

allies. The allices forged were in the interest of trade.

The French and Algonquins

The Algonquin people are an Indigenous people who now live in Eastern Canada. They speak the Algonquin language, which is part of the Algonquian language family. Culturally and linguistically, they are closely related to the Odawa, Potawatomi, ...

first encountered one another in 1603 after Samuel de Champlain

Samuel de Champlain (; Fichier OrigineFor a detailed analysis of his baptismal record, see RitchThe baptism act does not contain information about the age of Samuel, neither his birth date nor his place of birth. – 25 December 1635) was a Fre ...

established France's first permanent North American settlement along the St. Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connecting ...

. In 1610, the Algonquins continued to solidify their relations with the French by guiding Étienne Brûlé

Étienne Brûlé (; – c. June 1633) was the first European explorer to journey beyond the St. Lawrence River into what is now known as Canada. He spent much of his early adult life among the Hurons, and mastered their language and learned ...

into the interiors of Canada.

The relationship between the Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

and the French first began in 1609, where Samuel De Champlain

Samuel de Champlain (; Fichier OrigineFor a detailed analysis of his baptismal record, see RitchThe baptism act does not contain information about the age of Samuel, neither his birth date nor his place of birth. – 25 December 1635) was a Fre ...

engaged in battle against the Iroquois. Champlain travelled from the St. Lawrence Valley

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connecting t ...

, accompanied by his Algonquin

Algonquin or Algonquian—and the variation Algonki(a)n—may refer to:

Languages and peoples

*Algonquian languages, a large subfamily of Native American languages in a wide swath of eastern North America from Canada to Virginia

**Algonquin la ...

, Montagnais, and Huron

Huron may refer to:

People

* Wyandot people (or Wendat), indigenous to North America

* Wyandot language, spoken by them

* Huron-Wendat Nation, a Huron-Wendat First Nation with a community in Wendake, Quebec

* Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi ...

allies, to kill three Iroquoian chiefs on Lake Champlain

, native_name_lang =

, image = Champlainmap.svg

, caption = Lake Champlain-River Richelieu watershed

, image_bathymetry =

, caption_bathymetry =

, location = New York/Vermont in the United States; and Quebec in Canada

, coords =

, type =

, ...

with the first shots of his arquebus

An arquebus ( ) is a form of long gun that appeared in Europe and the Ottoman Empire during the 15th century. An infantryman armed with an arquebus is called an arquebusier.

Although the term ''arquebus'', derived from the Dutch word ''Haakbus ...

. The two factions (Iroquois and French) were constantly at war with one another until the Great Peace of Montréal in 1701. The

The French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

were interested in exploiting the land through the fur trade as well as the timber trade later on. Despite having tools and guns, the French settlers were dependent on Indigenous people to survive in the difficult climate in this part of North America. Many settlers did not know how to survive through the winter; the Indigenous people showed them how to survive in the New World. They showed the settlers how to hunt for food and to use the furs for clothing that would protect them during the winter months.

As the fur trade became the dominant economy in the New World, French voyageurs, trappers and hunters often married or formed relationships with Indigenous women. This allowed the French to develop relations with their wives' Indigenous nations, which in turn provided protection and access to their hunting and trapping grounds.

One specific Indigenous group borne of these relationships are the Métis

The Métis ( ; Canadian ) are Indigenous peoples who inhabit Canada's three Prairie Provinces, as well as parts of British Columbia, the Northwest Territories, and the Northern United States. They have a shared history and culture which derives ...

people, who are descendants of marriages between French men and Indigenous women. Their name originates from an old French term for “person of mixed parentage.” At the beginning of the fur trade, these relationships were encouraged by the French as a way to encourage the First Nations to adopt French culture and solidify alliances, but as the Métis began to emerge as an independent culture around the 1700s, it began to be discouraged by the French. Many Métis families moved to western Canada in response to this, as well as for other reasons, such as fur trading opportunities. One major settlement at this time was in the Red River Valley

The Red River Valley is a region in central North America that is drained by the Red River of the North; it is part of both Canada and the United States. Forming the border between Minnesota and North Dakota when these territories were admitted ...

, strategically placed in a significant area for the fur trade. This was the origin of the modern Métis nation, which was legally recognized by modern Canada as a protected Indigenous group in the Constitution Act, 1982

The ''Constitution Act, 1982'' (french: link=no, Loi constitutionnelle de 1982) is a part of the Constitution of Canada.Formally enacted as Schedule B of the ''Canada Act 1982'', enacted by the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Section 60 of t ...

. Its prior legal history has its roots in acts such as the Manitoba Act, 1870

The ''Manitoba Act, 1870'' (french: link=no, Loi de 1870 sur le Manitoba)Originally entitled (until renamed in 1982) ''An Act to amend and continue the Act 32 and 33 Victoria, chapter 3; and to establish and provide for the Government of the Pro ...

, which began to recognize the Métis nation as a separate group with various rights and protections, but was not supported by the vast majority of Métis as it removed many from land that was rightfully theirs.

The fur trade benefited Indigenous people as well. They traded furs for metal tools and other European-made items that made their lives easier. Tools such as knives, pots and kettles, nets, firearms and hatchets improved the general welfare of indigenous peoples. At the same time, while everyday life became easier, some traditional ways of doing things were abandoned or altered, and while Indigenous people embraced many of these implements and tools, they also were exposed to less vital trade goods, such as alcohol and sugar, sometimes with deleterious effects. The Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

, like most tribes, began to rely on the importation of European goods, like firearms, which contributed significantly to a decrease in the beaver population of the Hudson Valley

The Hudson Valley (also known as the Hudson River Valley) comprises the valley of the Hudson River and its adjacent communities in the U.S. state of New York. The region stretches from the Capital District including Albany and Troy south to ...

. This decline resulted in the fur trade moving further north, along the St. Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connecting ...

.

Formal entry of England in New France area fur trade

Since

Since Henry Hudson

Henry Hudson ( 1565 – disappeared 23 June 1611) was an English sea explorer and navigator during the early 17th century, best known for his explorations of present-day Canada and parts of the northeastern United States.

In 1607 and 160 ...

had claimed Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay ( crj, text=ᐐᓂᐯᒄ, translit=Wînipekw; crl, text=ᐐᓂᐹᒄ, translit=Wînipâkw; iu, text=ᑲᖏᖅᓱᐊᓗᒃ ᐃᓗᐊ, translit=Kangiqsualuk ilua or iu, text=ᑕᓯᐅᔭᕐᔪᐊᖅ, translit=Tasiujarjuaq; french: b ...

, and the surrounding lands for England in 1611, English colonists had begun expanding their boundaries across what is now the Canadian

Canadians (french: Canadiens) are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of ...

north beyond the French-held territory of New France. In 1670, King Charles II of England issued a charter to Prince Rupert and "the Company of Adventurers of England trading into Hudson Bay" for an English monopoly in harvesting furs in Rupert's Land

Rupert's Land (french: Terre de Rupert), or Prince Rupert's Land (french: Terre du Prince Rupert, link=no), was a territory in British North America which comprised the Hudson Bay drainage basin; this was further extended from Rupert's Land t ...

, a portion of the land draining into Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay ( crj, text=ᐐᓂᐯᒄ, translit=Wînipekw; crl, text=ᐐᓂᐹᒄ, translit=Wînipâkw; iu, text=ᑲᖏᖅᓱᐊᓗᒃ ᐃᓗᐊ, translit=Kangiqsualuk ilua or iu, text=ᑕᓯᐅᔭᕐᔪᐊᖅ, translit=Tasiujarjuaq; french: b ...

. This is the start of the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC; french: Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson) is a Canadian retail business group. A fur trading business for much of its existence, HBC now owns and operates retail stores in Canada. The company's namesake business div ...

, ironically aided by French ''coureurs des bois'', Pierre-Esprit Radisson and Médard des Groseilliers, frustrated with French license rules.

The economy of ''La Louisiane''

The major commercial importance of the Louisiana Purchase territory was the Mississippi River. New Orleans, the largest and most important city in the territory, was the most commercial city in the United States until the Civil War, with most jobs there being related to trade and shipping; there was little manufacturing. The first commercial shipment to come down the Mississippi River was of deer and bear hides in 1705.[