Free Derry on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Free Derry ( ga, Saor Dhoire) was a self-declared autonomous

Free Derry ( ga, Saor Dhoire) was a self-declared autonomous

The

The

The Derry March – Chronology of Events Surrounding the March

'', Conflict Archive on the Internet. Retrieved 11 November 2008. After the meeting of Londonderry Corporation was again disrupted in August, Eamonn Melaugh telephoned the

CAIN Web Service

) The march met with violent opposition from

The Apprentice Boys' parade is an annual celebration by unionists of the relief of the

The Apprentice Boys' parade is an annual celebration by unionists of the relief of the

History – Battle of the Bogside

'', The Museum of Free Derry. Retrieved 11 November 2008. Walkie-talkies were used to maintain contact between different areas of fighting and DCDA headquarters in Paddy Doherty's house in Westland Street, and first aid stations were operating, staffed by doctors, nurses and volunteers. Women and girls made milk-bottle crates of petrol bombs for supply to the youths in the front line and "Radio Free Derry" broadcast to the fighters and their families. On the third day of fighting, 14 August, the Northern Ireland Government mobilised the

An anti-internment protest organised by NICRA at Magilligan Camp in January 1972 was met with violence from the

An anti-internment protest organised by NICRA at Magilligan Camp in January 1972 was met with violence from the

CAIN Web Service

* McCann, Eamonn, ''War and an Irish Town'', 2nd edition, Pluto Press, London, 1980, * Ó Dochartaigh, Niall, ''From Civil Rights to Armalites: Derry and the Birth of the Irish Troubles'', Palgrave MacMillan, Basingstoke, 2005, * Office of the Police Ombudsman for Northern Ireland, ''Report of the Police Ombudsman for Northern Ireland into a complaint made by the Devenny family on 20 April 2001'', Belfast, 2001

* Farrell, Sean, ''Rituals and Riots: Sectarian Violence and Political Culture in Ulster, 1784–1886'',The University Press of Kentucky 2000,

Museum of Free Derry

{{Coord, 54.997, -7.326, display=title The Troubles in Derry (city) 1969 establishments in Northern Ireland 1972 disestablishments in Northern Ireland

Free Derry ( ga, Saor Dhoire) was a self-declared autonomous

Free Derry ( ga, Saor Dhoire) was a self-declared autonomous Irish nationalist

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cu ...

area of Derry

Derry, officially Londonderry (), is the second-largest city in Northern Ireland and the fifth-largest city on the island of Ireland. The name ''Derry'' is an anglicisation of the Old Irish name (modern Irish: ) meaning 'oak grove'. The ...

, Northern Ireland, that existed between 1969 and 1972, during the Troubles

The Troubles ( ga, Na Trioblóidí) were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it is sometimes described as an "i ...

. It emerged during the Northern Ireland civil rights movement

The Northern Ireland civil rights movement dates to the early 1960s, when a number of initiatives emerged in Northern Ireland which challenged the inequality and discrimination against ethnic Irish Catholics that was perpetrated by the Ulster Pr ...

, which sought to end discrimination against the Irish Catholic

Irish Catholics are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland whose members are both Catholic and Irish. They have a large diaspora, which includes over 36 million American citizens and over 14 million British citizens (a quarter of the British ...

/nationalist minority by the Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

/ unionist government. The civil rights movement highlighted the sectarianism

Sectarianism is a political or cultural conflict between two groups which are often related to the form of government which they live under. Prejudice, discrimination, or hatred can arise in these conflicts, depending on the political status quo ...

and police brutality

Police brutality is the excessive and unwarranted use of force by law enforcement against an individual or a group. It is an extreme form of police misconduct and is a civil rights violation. Police brutality includes, but is not limited to, ...

of the overwhelmingly Protestant police force, the Royal Ulster Constabulary

The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) was the police force in Northern Ireland from 1922 to 2001. It was founded on 1 June 1922 as a successor to the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC)Richard Doherty, ''The Thin Green Line – The History of the Royal ...

(RUC). The area, which included the mainly-Catholic Bogside

The Bogside is a neighbourhood outside the city walls of Derry, Northern Ireland. The large gable-wall murals by the Bogside Artists, Free Derry Corner and the Gasyard Féile (an annual music and arts festival held in a former gasyard) are p ...

and Creggan neighbourhoods, was first secured by community activists on 5 January 1969 following an incursion into the Bogside by RUC officers. Residents built barricade

Barricade (from the French ''barrique'' - 'barrel') is any object or structure that creates a barrier or obstacle to control, block passage or force the flow of traffic in the desired direction. Adopted as a military term, a barricade denot ...

s and carried clubs

Club may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Club'' (magazine)

* Club, a ''Yie Ar Kung-Fu'' character

* Clubs (suit), a suit of playing cards

* Club music

* "Club", by Kelsea Ballerini from the album ''kelsea''

Brands and enterprises

...

and similar arms to prevent the RUC from entering. Its name was taken from a sign painted on a gable wall in the Bogside which read, "You are now entering Free Derry". For six days the area was a no-go area

A "no-go area" or "no-go zone" is a neighborhood or other geographic area where some or all outsiders are either physically prevented from entering or can enter at risk. The term includes exclusion zones, which are areas that are officially kept o ...

, after which the residents took down the barricades and RUC patrols resumed. Tensions remained high over the following months.

On 12 August 1969, sporadic violence led to the Battle of the Bogside

The Battle of the Bogside was a large three-day riot that took place from 12 to 14 August 1969 in Derry, Northern Ireland. Thousands of Catholic/Irish nationalist residents of the Bogside district, organised under the Derry Citizens' Defence ...

: a three-day pitched battle between thousands of residents and the RUC, which spread to other parts of Northern Ireland. Barricades were re-built, petrol bomb

A Molotov cocktail (among several other names – ''see other names'') is a hand thrown incendiary weapon constructed from a frangible container filled with flammable substances equipped with a fuse (typically a glass bottle filled with flammab ...

"factories" and first aid posts were set up, and a radio transmitter ("Radio Free Derry") broadcast messages calling for resistance. The RUC fired CS gas

The compound 2-chlorobenzalmalononitrile (also called ''o''-chlorobenzylidene malononitrile; chemical formula: C10H5ClN2), a cyanocarbon, is the defining component of tear gas commonly referred to as CS gas, which is used as a riot control agent ...

into the Bogside – the first time it had been used by UK police. On 14 August, the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

were deployed at the edge of the Bogside and the RUC were withdrawn. The Derry Citizens Defence Association

The Derry Citizens' Defense Association (DCDA) was an organisation set up in Derry in July 1969 in response to a threat to nationalist residents from the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and civilian unionists, in connection with the annual par ...

(DCDA) declared their intention to hold the area against both the RUC and the British Army until their demands were met. The British Army made no attempt to enter the area. The situation continued until October 1969 when, following publication of the Hunt Report

The Hunt Report, or the Report of the Advisory Committee on Police in Northern Ireland, was produced by a committee headed by Baron Hunt in 1969. An investigation was performed into the perceived bias in policing in Northern Ireland against Catho ...

, military police

Military police (MP) are law enforcement agencies connected with, or part of, the military of a state. In wartime operations, the military police may support the main fighting force with force protection, convoy security, screening, rear recon ...

were allowed in.

The Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various paramilitary organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dedicated to irredentism through Irish republicanism, the belief tha ...

(IRA) began to re-arm and recruit after August 1969. In December 1969 it split into the Official IRA

The Official Irish Republican Army or Official IRA (OIRA; ) was an Irish republican paramilitary group whose goal was to remove Northern Ireland from the United Kingdom and create a "workers' republic" encompassing all of Ireland. It emerged ...

and the Provisional IRA

The Irish Republican Army (IRA; ), also known as the Provisional Irish Republican Army, and informally as the Provos, was an Irish republicanism, Irish republican paramilitary organisation that sought to end British rule in Northern Ireland, fa ...

. Both were supported by the people of Free Derry. Meanwhile, the initially good relations between the British Army and the nationalist community worsened. In July 1971 there was a surge of recruitment into the IRA after two young men were shot dead by British troops in Derry. The government introduced internment

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simpl ...

on 9 August 1971 in Operation Demetrius

Operation Demetrius was a British Army operation in Northern Ireland on 9–10 August 1971, during the Troubles. It involved the mass arrest and internment (imprisonment without trial) of people suspected of being involved with the Irish Republi ...

. In response, barricades went up once more around Free Derry. This time, Free Derry was defended by well-armed members of the IRA. From within the area they launched attacks on the British Army, and the Provisionals began a bombing campaign in the city centre. As before, unarmed "auxiliaries" manned the barricades, and crime was dealt with by a voluntary body known as the Free Derry Police.

Support for the IRA rose further after Bloody Sunday

Bloody Sunday may refer to:

Historical events Canada

* Bloody Sunday (1923), a day of police violence during a steelworkers' strike for union recognition in Sydney, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia

* Bloody Sunday (1938), police violence aga ...

in January 1972, when thirteen unarmed men and boys were shot dead by the British Parachute Regiment during a protest march in the Bogside (a 14th man was wounded and died months later). Following the Bloody Friday bombings, the British decided to re-take the "no-go" areas. Free Derry came to an end on 31 July 1972 in Operation Motorman

Operation Motorman was a large operation carried out by the British Army ( HQ Northern Ireland) in Northern Ireland during the Troubles. The operation took place in the early hours of 31 July 1972 with the aim of retaking the "no-go areas" (ar ...

, when thousands of British troops moved in with armoured vehicles and bulldozers.

Background

Derry

Derry, officially Londonderry (), is the second-largest city in Northern Ireland and the fifth-largest city on the island of Ireland. The name ''Derry'' is an anglicisation of the Old Irish name (modern Irish: ) meaning 'oak grove'. The ...

City lies near the border between Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

and the Republic of Ireland

Ireland ( ga, Éire ), also known as the Republic of Ireland (), is a country in north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 counties of the island of Ireland. The capital and largest city is Dublin, on the eastern side of the island. A ...

. It has a majority nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

population, and nationalists won a majority of seats in the 1920 local elections. Despite this, the Ulster Unionist Party

The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) is a unionist political party in Northern Ireland. The party was founded in 1905, emerging from the Irish Unionist Alliance in Ulster. Under Edward Carson, it led unionist opposition to the Irish Home Rule movem ...

controlled the local council

A council is a group of people who come together to consult, deliberate, or make decisions. A council may function as a legislature, especially at a town, city or county/shire level, but most legislative bodies at the state/provincial or natio ...

, Londonderry Corporation, from 1923 onwards. The Unionists maintained their majority, firstly, by manipulating the constituency boundaries (gerrymandering

In representative democracies, gerrymandering (, originally ) is the political manipulation of electoral district boundaries with the intent to create undue advantage for a party, group, or socioeconomic class within the constituency. The m ...

) so that the South Ward, with a nationalist majority, returned eight councillors while the much smaller North Ward and Waterside Ward, with unionist majorities, returned twelve councillors between them; secondly, by allowing only ratepayers

Rates are a type of property tax system in the United Kingdom, and in places with systems deriving from the British one, the proceeds of which are used to fund local government. Some other countries have taxes with a more or less comparable role ...

to vote in local elections, rather than one man, one vote

"One man, one vote", or "one person, one vote", expresses the principle that individuals should have equal representation in voting. This slogan is used by advocates of political equality to refer to such electoral reforms as universal suffrage, ...

, so that a higher number of nationalists, who did not own or rent homes, were disenfranchised; and thirdly, by denying council housing

Public housing in the United Kingdom, also known as council estates, council housing, or social housing, provided the majority of rented accommodation until 2011 when the number of households in private rental housing surpassed the number in so ...

to nationalists outside the South Ward constituency. The result was that there were about 2,000 nationalist families, and practically no unionists, on the housing waiting list, and that housing in the nationalist area was crowded and of a very poor condition. The South Ward comprised the Bogside

The Bogside is a neighbourhood outside the city walls of Derry, Northern Ireland. The large gable-wall murals by the Bogside Artists, Free Derry Corner and the Gasyard Féile (an annual music and arts festival held in a former gasyard) are p ...

, Brandywell, Creggan, Bishop Street and Foyle Road, and it was this area that would become Free Derry.

The

The Derry Housing Action Committee

The Derry Housing Action Committee (DHAC), was an organisation formed in 1968 in Derry, Northern Ireland to protest about housing conditions and provision.

The DHAC was formed in February 1968 by two socialists and four tenants in response to the ...

(DHAC) was formed in March 1968 by members of the Derry Branch of the Northern Ireland Labour Party

The Northern Ireland Labour Party (NILP) was a political party in Northern Ireland which operated from 1924 until 1987.

Origins

The roots of the NILP can be traced back to the formation of the Belfast Labour Party in 1892. William Walker stoo ...

and the James Connolly Republican Club, including Eamonn McCann

Eamonn McCann (born 10 March 1943) is an Irish politician, journalist, political activist, and former councillor from Derry, Northern Ireland. McCann was a People Before Profit (PBP) Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) for Foyle from 2016 ...

and Eamonn Melaugh. It disrupted a meeting of Londonderry Corporation in March 1968 and in May blocked traffic by placing a caravan that was home to a family of four in the middle of the Lecky Road in the Bogside and staging a sit-down protest at the opening of the second deck of the Craigavon Bridge

The Craigavon Bridge is one of three bridges in Derry, Northern Ireland. It crosses the River Foyle further south than the Foyle Bridge and Peace Bridge. It is one of only a few double-decker road bridges in Europe. It was named after Lord Craiga ...

.The Derry March – Chronology of Events Surrounding the March

'', Conflict Archive on the Internet. Retrieved 11 November 2008. After the meeting of Londonderry Corporation was again disrupted in August, Eamonn Melaugh telephoned the

Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association

) was an organisation that campaigned for civil rights in Northern Ireland during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Formed in Belfast on 9 April 1967,

(NICRA) and invited them to hold a march in Derry. The date chosen was 5 October 1968, an ad hoc committee was formed (although in reality most of the organising was done by McCann and Melaugh) and the route was to take the marchers inside the city walls, where nationalists were traditionally not permitted to march. The Minister of Home Affairs

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergency ...

, William Craig, made an order on 3 October prohibiting the march on the grounds that the Apprentice Boys of Derry

The Apprentice Boys of Derry is a Protestant fraternal society with a worldwide membership of over 10,000, founded in 1814 and based in the city of Derry, Northern Ireland. There are branches in Ulster and elsewhere in Ireland, Scotland, Engla ...

were intending to hold a march on the same day. In the words of Martin Melaugh of CAIN

Cain ''Káïn''; ar, قابيل/قايين, Qābīl/Qāyīn is a Biblical figure in the Book of Genesis within Abrahamic religions. He is the elder brother of Abel, and the firstborn son of Adam and Eve, the first couple within the Bible. He wa ...

"this particular tactic...provided the excuse needed to ban the march." When the marchers attempted to defy the ban on 5 October they were stopped by a Royal Ulster Constabulary

The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) was the police force in Northern Ireland from 1922 to 2001. It was founded on 1 June 1922 as a successor to the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC)Richard Doherty, ''The Thin Green Line – The History of the Royal ...

(RUC) cordon. The police drew their batons and struck marchers, including Stormont MP Eddie McAteer

Eddie McAteer (25 June 1914 – 25 March 1986) was an Irish nationalist politician in Northern Ireland.

Born in Coatbridge, Scotland, McAteer's family moved to Derry in Northern Ireland while he was young. In 1930 he joined the Inland Revenu ...

and Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Bu ...

MP Gerry Fitt

Gerard Fitt, Baron Fitt (9 April 1926 – 26 August 2005) was a politician in Northern Ireland. He was a founder and the first leader of the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP), a social democratic and Irish nationalist party.

Early year ...

. Subsequently, the police "broke ranks and used their batons indiscriminately on people in Duke Street". Marchers trying to escape met another party of police and "these police also used their batons indiscriminately." Water cannons were also used. The police action caused outrage in the nationalist area of Derry, and at a meeting four days later the Derry Citizens' Action Committee (DCAC) was formed, with John Hume

John Hume (18 January 19373 August 2020) was an Irish nationalist politician from Northern Ireland, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in the recent political history of Ireland, as one of the architects of the Northern Irela ...

as chairman and Ivan Cooper

Ivan Averill Cooper (5 January 1944 – 26 June 2019) was an Irish politician from Northern Ireland. He was a member of the Parliament of Northern Ireland and a founding member of the SDLP. He is best known for leading the anti-internment march o ...

as vice-chairman.

The first barricades

Another group formed as a result of the events of 5 October was People's Democracy, a group of students inQueen's University Belfast

, mottoeng = For so much, what shall we give back?

, top_free_label =

, top_free =

, top_free_label1 =

, top_free1 =

, top_free_label2 =

, top_free2 =

, established =

, closed =

, type = Public research university

, parent = ...

. They organised a march from Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdo ...

to Derry in support of civil rights, starting out with about forty young people on 1 January 1969.Bowes Egan and Vincent McCormack, ''Burntollet'' (1969) CAIN Web Service

) The march met with violent opposition from

loyalist

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cro ...

counter-demonstrators at several points along the route. Finally, at Burntollet Bridge, five miles outside Derry, they were attacked by a mob of about two hundred wielding clubs—some of them studded with nails—and stones. Half of the attackers were later identified from press photographs as members of the B-Specials

The Ulster Special Constabulary (USC; commonly called the "B-Specials" or "B Men") was a quasi-military reserve special constable police force in what would later become Northern Ireland. It was set up in October 1920, shortly before the par ...

. The police, who were at the scene, chatted to the B-Specials as they prepared their ambush, and then failed to protect the marchers, many of whom ran into the river and were attacked with stones thrown from the bank. Dozens of marchers were taken to hospital. The remainder continued on to Derry where they were attacked once more on their way to Craigavon Bridge before they finally reached Guildhall Square, where they held a rally. Rioting broke out after the rally. Police drove rioters into the Bogside, but did not come after them. In the early hours of the following morning, 5 January, members of the RUC charged into St. Columb's Wells and Lecky Road in the Bogside, breaking windows and beating residents.1,500 arm to defend their area, ''The Irish Times'', 6 January 1969 In his report on the disturbances, Lord Cameron remarked that "for such conduct among members of a disciplined and well-led force there can be no acceptable justification or excuse" and added that "its effect in rousing passions and inspiring hostility towards the police was regrettably great."

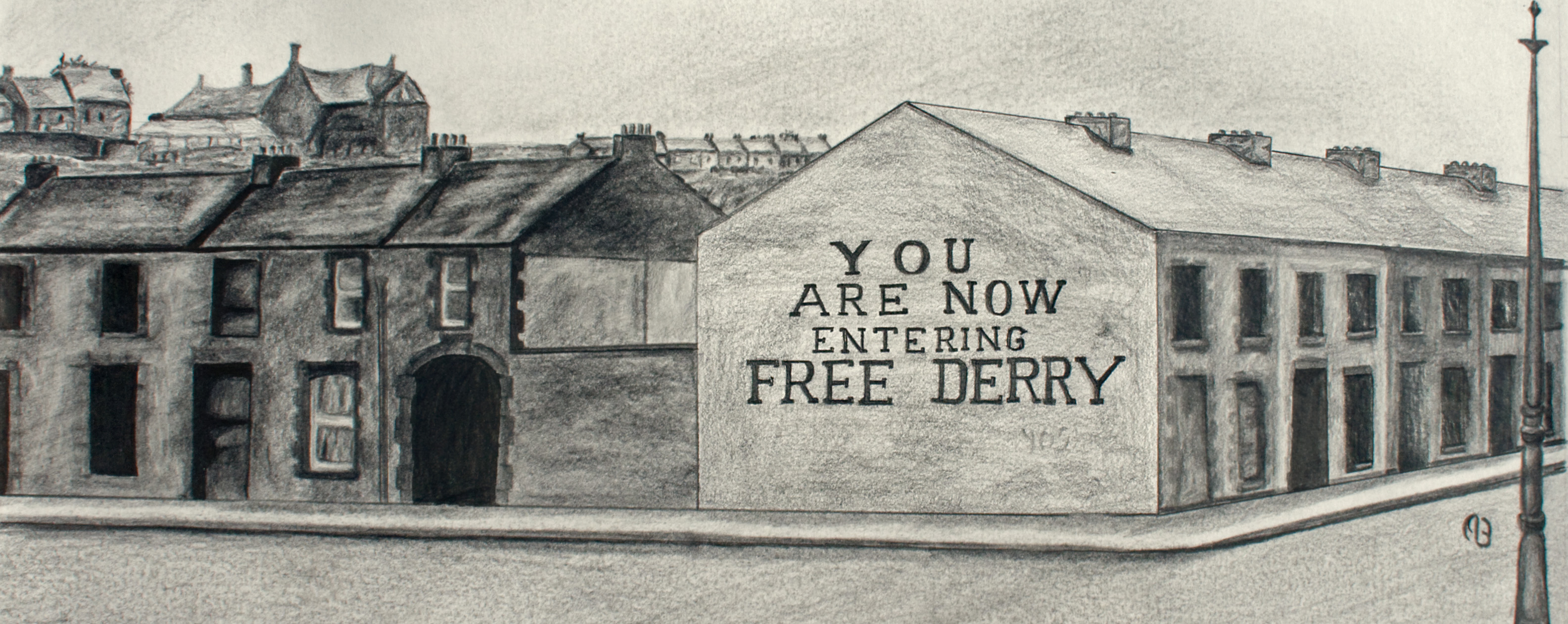

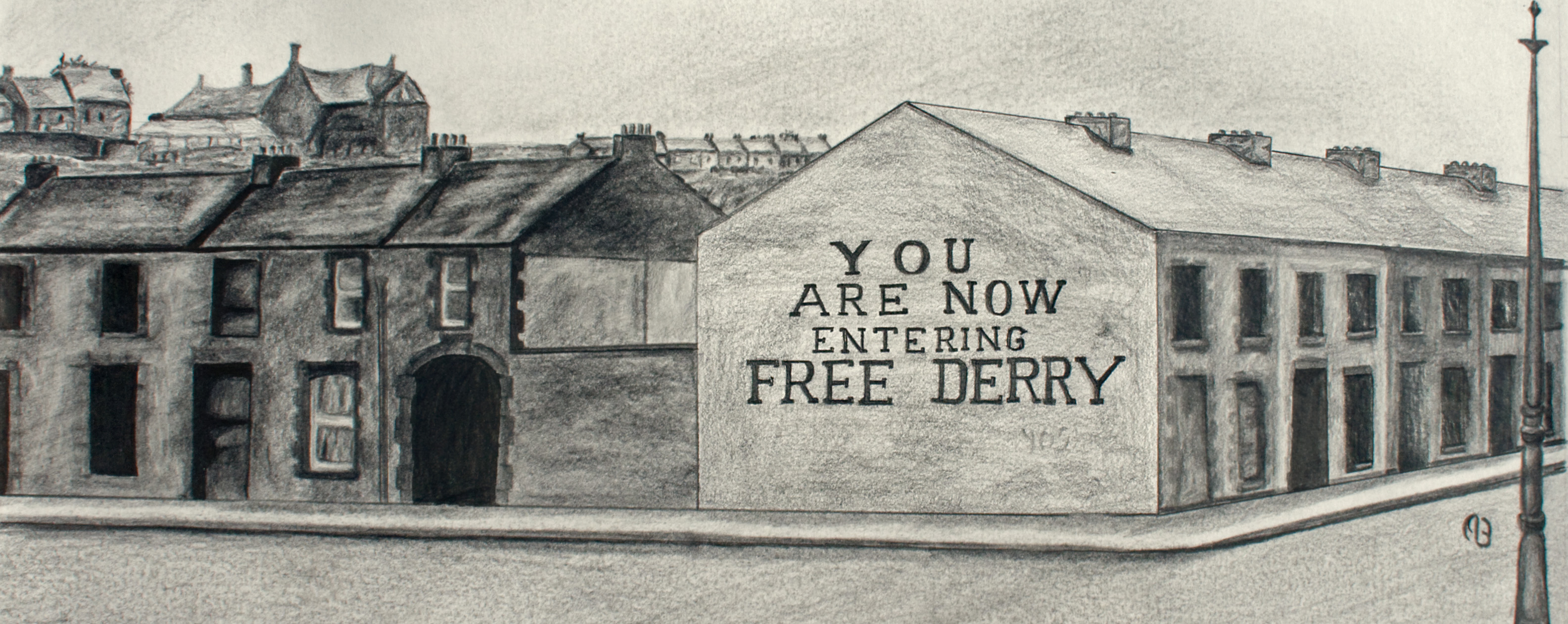

That afternoon over 1,500 Bogside residents built barricade

Barricade (from the French ''barrique'' - 'barrel') is any object or structure that creates a barrier or obstacle to control, block passage or force the flow of traffic in the desired direction. Adopted as a military term, a barricade denot ...

s, armed themselves with steel bars, wooden clubs and hurleys, and told the police that they would not be allowed into the area. DCAC chairman John Hume told a meeting of residents that they were to defend the area and no-one was to come in. Groups of men wearing armband

An armband is a piece of material worn around the arm. They may be worn for pure ornamentation, or to mark the wearer as belonging to group, or as insignia having a certain rank, status, office or role, or being in a particular state or condit ...

s patrolled the streets in shifts. A local activist painted "You are now entering Free Derry" in light-coloured paint on the blackened gable wall of a house on the corner of Lecky Road and Fahan Street. For many years, it was believed that it was John 'Caker' Casey that painted it, but after Casey's death it emerged that it might have been another young activist, Liam Hillen. The corner where the slogan was painted, which was a popular venue for meetings, later became known as "Free Derry Corner

Free Derry Corner is a historical landmark in the Bogside neighbourhood of Derry, Northern Ireland, which lies in the intersection of the Lecky Road, Rossville Street and Fahan Street. A free-standing gable wall commemorates Free Derry, a self ...

". On 7 January, the barricaded area was extended to include the Creggan, another nationalist area on a hill overlooking the Bogside. A clandestine radio

Pirate radio or a pirate radio station is a radio station that broadcasts without a valid license.

In some cases, radio stations are considered legal where the signal is transmitted, but illegal where the signals are received—especially w ...

station calling itself "Radio Free Derry" began broadcasting to residents,Advice given for Derry 'Revolution', ''The Irish Times'', 11 January 1969, page 14 playing rebel songs and encouraging resistance.McCann, Eamonn, ''War and an Irish Town'', p. 56 On a small number of occasions law-breakers attempted crimes, but were dealt with by the patrols. Despite all this, the ''Irish Times

''The Irish Times'' is an Irish daily broadsheet newspaper and online digital publication. It launched on 29 March 1859. The editor is Ruadhán Mac Cormaic. It is published every day except Sundays. ''The Irish Times'' is considered a newspaper ...

'' reported that "the infrastructure of revolutionary control in the area has not been developed beyond the maintenance of patrols." Following some acts of destruction and of violence late in the week, members of the DCAC including Ivan Cooper addressed residents on Friday, 10 January and called on them to dismantle the barricades. The barricades were taken down the following morning.

April 1969

Over the next three months there were violent clashes, with local youths throwing stones at police. Violence came to a head on Saturday, 19 April after a planned march from Burntollet Bridge to the city centre was banned. A protest in the city centre led to clashes with "Paisleyites"—unionists in sympathy with the anti-civil rights stance ofIan Paisley

Ian Richard Kyle Paisley, Baron Bannside, (6 April 1926 – 12 September 2014) was a Northern Irish loyalist politician and Protestant religious leader who served as leader of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) from 1971 to 2008 and First ...

. Police attempting to drive the protesters back into the Bogside were themselves driven back to their barracks. A series of pitched battles followed, and barricades were built, often under the supervision of Bernadette Devlin

Josephine Bernadette McAliskey (née Devlin; born 23 April 1947), usually known as Bernadette Devlin or Bernadette McAliskey, is an Irish civil rights leader, and former politician. She served as Member of Parliament (MP) for Mid Ulster in North ...

, newly elected MP for Mid Ulster. Police pursuing rioters broke into a house in William Street and severely beat the occupant, Samuel Devenny, his family and two friends. Devenny was brought to hospital "bleeding profusely from a number of head wounds." At midnight four hundred RUC men in full riot gear and carrying riot shields occupied the Bogside.RUC obey Bogside ultimatum, ''The Irish Times'', 21 April 1969 Convoys of police vehicles drove through the area with headlights blazing.

The following day, several thousand residents, led by the DCAC, withdrew to the Creggan and issued an ultimatum to the RUC – withdraw within two hours or be driven out. With fifteen minutes of the two hours remaining, the police marched out through the Butcher's Gate, even as the residents were entering from the far side. The barricades were not maintained on this occasion, and routine patrols were not prevented.

Samuel Devenny suffered a heart attack four days after his beating. On 17 July he suffered a further heart attack and died. Thousands attended his funeral, and the mood was sufficiently angry that it was clear the annual Apprentice Boys

The Apprentice Boys of Derry is a Protestant fraternal society with a worldwide membership of over 10,000, founded in 1814 and based in the city of Derry, Northern Ireland. There are branches in Ulster and elsewhere in Ireland, Scotland, Engla ...

' parade, scheduled for 12 August, could not take place without causing serious disturbance.

August – October 1969

The Apprentice Boys' parade is an annual celebration by unionists of the relief of the

The Apprentice Boys' parade is an annual celebration by unionists of the relief of the siege of Derry

The siege of Derry in 1689 was the first major event in the Williamite War in Ireland. The siege was preceded by a first attempt against the town by Jacobite forces on 7 December 1688 that was foiled when 13 apprentices shut the gates ...

in 1689, which began when thirteen young apprentice

Apprenticeship is a system for training a new generation of practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study (classroom work and reading). Apprenticeships can also enable practitioners to gain a ...

boys shut the city's gates against the army of King James. At that time the parade was held on 12 August each year. Participants from across Northern Ireland and Britain marched along the city walls above the Bogside, and were often openly hostile to the residents. On 30 July 1969 the Derry Citizens Defence Association

The Derry Citizens' Defense Association (DCDA) was an organisation set up in Derry in July 1969 in response to a threat to nationalist residents from the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and civilian unionists, in connection with the annual par ...

(DCDA) was formed to try to preserve peace during the period of the parade, and to defend the Bogside and Creggan in the event of an attack. The chairman was Seán Keenan, an Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various paramilitary organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dedicated to irredentism through Irish republicanism, the belief tha ...

(IRA) veteran; the vice-chairman was Paddy Doherty, a popular local man sometimes known as "Paddy Bogside" and the secretary was Johnnie White, another leading republican and leader of the James Connolly Republican Club. Street committees were formed under the overall command of the DCDA and barricades were built on the night of 11 August. The parade took place as planned on 12 August. As it passed through Waterloo Place, on the edge of the Bogside, hostilities began between supporters and opponents of the parade. Fighting between the two groups continued for two hours, then the police joined in. They charged up William Street against the Bogsiders, followed by the 'Paisleyites'. They were met with a hail of stones and petrol bombs. The ensuing battle became known as the Battle of the Bogside

The Battle of the Bogside was a large three-day riot that took place from 12 to 14 August 1969 in Derry, Northern Ireland. Thousands of Catholic/Irish nationalist residents of the Bogside district, organised under the Derry Citizens' Defence ...

. Late in the evening, having been driven back repeatedly, the police fired canisters of CS gas

The compound 2-chlorobenzalmalononitrile (also called ''o''-chlorobenzylidene malononitrile; chemical formula: C10H5ClN2), a cyanocarbon, is the defining component of tear gas commonly referred to as CS gas, which is used as a riot control agent ...

into the crowd. Youths on the roof of a high-rise block of flats on Rossville Street threw petrol bombs down on the police.History – Battle of the Bogside

'', The Museum of Free Derry. Retrieved 11 November 2008. Walkie-talkies were used to maintain contact between different areas of fighting and DCDA headquarters in Paddy Doherty's house in Westland Street, and first aid stations were operating, staffed by doctors, nurses and volunteers. Women and girls made milk-bottle crates of petrol bombs for supply to the youths in the front line and "Radio Free Derry" broadcast to the fighters and their families. On the third day of fighting, 14 August, the Northern Ireland Government mobilised the

Ulster Special Constabulary

The Ulster Special Constabulary (USC; commonly called the "B-Specials" or "B Men") was a quasi-military reserve special constable police force in what would later become Northern Ireland. It was set up in October 1920, shortly before the par ...

(B-Specials), a force greatly feared by nationalists in Derry and elsewhere. Before they engaged, however, British troops

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurkhas ...

were deployed at the scene, carrying automatic rifle

An automatic rifle is a type of autoloading rifle that is capable of fully automatic fire. Automatic rifles are generally select-fire weapons capable of firing in semi-automatic and automatic firing modes (some automatic rifles are capable of ...

s and sub-machine guns

A submachine gun (SMG) is a magazine-fed, automatic carbine designed to fire handgun cartridges. The term "submachine gun" was coined by John T. Thompson, the inventor of the Thompson submachine gun, to describe its design concept as an automati ...

. The RUC and B-Specials withdrew, and the troops took up positions outside the barricaded area.

A deputation that included Eamonn McCann met senior army officers and told them that the army would not be allowed in until certain demands were met, including the disarming of the RUC, the disbandment of the B-Specials and the abolition of Stormont (the Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

and Government of Northern Ireland

The government of Northern Ireland is, generally speaking, whatever political body exercises political authority over Northern Ireland. A number of separate systems of government exist or have existed in Northern Ireland.

Following the partitio ...

). The officers agreed that neither troops nor police would enter the Bogside and Creggan districts. A 'peace corps' was formed to maintain law and order. When the British Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national ...

, Jim Callaghan

Leonard James Callaghan, Baron Callaghan of Cardiff, ( ; 27 March 191226 March 2005), commonly known as Jim Callaghan, was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1976 to 1979 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1976 to 1980. Callaghan is ...

, visited Northern Ireland and announced his intention to visit the Bogside on 28 August, he was told that he would not be allowed to bring either police or soldiers with him. Callaghan agreed. Accompanied by members of the Defence Committee, he was "swept along by a surging crowd of thousands" up Rossvile Street and into Lecky Road, where he "took refuge" in a local house, and later addressed crowds from an upstairs window. In preparation for Callaghan's visit the "Free Derry" wall was painted white and the "You are now entering Free Derry" sign was professionally re-painted in black lettering.

Following Callaghan's visit, some barricades were breached, but the majority remained while the people awaited concrete evidence of reform. Still the army made no move to enter the area. Law and order was maintained by a 'peace corps'—volunteers organised by the DCDA to patrol the streets and man the barricades. There was very little crime. Punishment, in the words of Eamonn McCann, "as often as not consisted of a stern lecture from Seán Keenan on the need for solidarity within the area." In September the barricades were replaced with a white line painted on the road.

The Hunt Report

The Hunt Report, or the Report of the Advisory Committee on Police in Northern Ireland, was produced by a committee headed by Baron Hunt in 1969. An investigation was performed into the perceived bias in policing in Northern Ireland against Catho ...

on the future of policing in Northern Ireland was presented to the Stormont cabinet in early October. Jim Callaghan held talks with the cabinet in Belfast on 10 October, following which the report's recommendations were accepted and made public. They included the recommendation that the RUC should be 'ordinarily' unarmed, and that the B-Specials should be phased out and replaced by a new force. The new RUC Chief Constable, Arthur Young, an Englishman, was announced, and travelled to Belfast with Callaghan. The same day, Seán Keenan announced that the DCDA was to be dissolved. On 11 October Callaghan and Young visited Free Derry, and on 12 October the first military police

Military police (MP) are law enforcement agencies connected with, or part of, the military of a state. In wartime operations, the military police may support the main fighting force with force protection, convoy security, screening, rear recon ...

entered the Bogside, on foot and unarmed.

IRA resurgence

TheIrish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various paramilitary organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dedicated to irredentism through Irish republicanism, the belief tha ...

(IRA) had been inactive militarily since the end of the Border Campaign in 1962. It was low in both personnel and equipment—Chief of Staff Cathal Goulding

Cathal Goulding ( ga, Cathal Ó Goillín; 2 January 1923 – 26 December 1998) was Chief of Staff of the Irish Republican Army and the Official IRA.

Early life and career

One of seven children born on East Arran Street in north Dublin to an ...

told Seán Keenan and Paddy Doherty in August 1969 that he "couldn't defend the Bogside. I haven't the men nor the guns to do it." During the 1960s the leadership of the republican movement had moved to the left

Left may refer to:

Music

* ''Left'' (Hope of the States album), 2006

* ''Left'' (Monkey House album), 2016

* "Left", a song by Nickelback from the album ''Curb'', 1996

Direction

* Left (direction), the relative direction opposite of right

* L ...

. Its focus was on class struggle

Class conflict, also referred to as class struggle and class warfare, is the political tension and economic antagonism that exists in society because of socio-economic competition among the social classes or between rich and poor.

The forms ...

and its aim was to unite the Irish nationalist and unionist working classes to overthrow capitalism, both British and Irish. Republican Clubs were formed in Northern Ireland, where Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( , ; en, " eOurselves") is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active throughout both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Gri ...

was proscribed. These clubs were involved in the formation of NICRA in 1967. In Derry, the James Connolly Republican Club worked closely with Labour Party radicals, with whom they set up the Derry Housing Action Committee and Derry Unemployed Action Committee. The Derry Citizens' Defence Association was formed initially by republicans, who then invited other nationalists to join. Although there were tensions between the younger leaders like Johnnie White and the older, traditional republicans such as Seán Keenan, both sides saw the unrest of 1968–69 as a chance to advance republican aims, and the two shared the platform at the Easter Rising

The Easter Rising ( ga, Éirí Amach na Cásca), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the a ...

commemoration in April 1969.

The events of August 1969 in Derry, and more particularly in Belfast where the IRA was unable to prevent loss of life or protect families burned out of their homes, brought to a head the divisions that had already appeared within the movement between the radicals and the traditionalists, and led to a split in December 1969 into the Official IRA

The Official Irish Republican Army or Official IRA (OIRA; ) was an Irish republican paramilitary group whose goal was to remove Northern Ireland from the United Kingdom and create a "workers' republic" encompassing all of Ireland. It emerged ...

and the Provisional IRA

The Irish Republican Army (IRA; ), also known as the Provisional Irish Republican Army, and informally as the Provos, was an Irish republicanism, Irish republican paramilitary organisation that sought to end British rule in Northern Ireland, fa ...

. Initially, both armies organised for defensive

Defense or defence may refer to:

Tactical, martial, and political acts or groups

* Defense (military), forces primarily intended for warfare

* Civil defense, the organizing of civilians to deal with emergencies or enemy attacks

* Defense indust ...

purposes only, although the Provisionals were planning towards an offensive

Offensive may refer to:

* Offensive, the former name of the Dutch political party Socialist Alternative

* Offensive (military), an attack

* Offensive language

** Fighting words or insulting language, words that by their very utterance inflict inj ...

campaign. In Derry there was far less hostility between the two organisations than elsewhere and householders commonly paid subscriptions to both. When rioters were arrested after the Officials' Easter parade in March 1970, Officials and Provisionals picketed their trial together. At the start the Officials attracted most of the younger members. Martin McGuinness

James Martin Pacelli McGuinness ( ga, Séamus Máirtín Pacelli Mag Aonghusa; 23 May 1950 – 21 March 2017) was an Irish republican politician and statesman from Sinn Féin and a leader within the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) during ...

, who in August 1969 had helped defend the barricades, initially joined the Officials, but a few months later left to join the Provisionals.

Relations between the British Army and the residents had steadily decayed since the first appearance of troops in August 1969. In September, after clashes between nationalist and unionist crowds that led to the death of a Protestant man, William King, the British Army erected a 'peace ring' to enclose the nationalist population in the area they had previously controlled. Roads into the city centre were closed at night and people were prevented from walking on certain streets. Although some moderate nationalists accepted this as necessary, there was anger among young people. Clashes between youths and troops became more frequent. The riot following the Officials' Easter parade in March 1970 marked the first time that the army used 'snatch squad The term "snatch squad" refers to two tactics used by police in riot control and crowd control.

In riot control

The snatch squad in riot control involves several police officers, usually wearing protective riot gear, rushing forwards—occasionally ...

s', who rushed into the Bogside wielding batons to make arrests. The snatch squads soon became a common feature of army arrest operations. There was also a belief that they were arresting people at random, sometimes days after the alleged offence, and based on the identification of people that they had seen from a considerable distance. The rioters were condemned as hooligans

Hooliganism is disruptive or unlawful behavior such as rioting, bullying and vandalism, usually in connection with crowds at sporting events.

Etymology

There are several theories regarding the origin of the word ''hooliganism,'' which is a ...

by moderates, who saw the riots as hampering attempts to resolve the situation. The Labour radicals and Official republicans, still working together, tried to turn the youth away from rioting and create socialist organisations—one such organisation was named the Young Hooligans Association—but to no avail. The Provisionals, while disapproving of riots, viewed them as the inevitable consequence of British occupation. This philosophy was more attractive to rioters, and some of them joined the Provisional IRA. The deaths of two leading Provisionals in a premature explosion in June 1970 resulted in young militants becoming more prominent in the organisation. Nevertheless, up to July 1971 the Provisional IRA remained numerically small.

Two men, Séamas Cusack and Desmond Beattie, were shot dead in separate incidents in the early morning and afternoon of 8 July 1971. They were the first people to be killed by the British Army in Derry. In both cases the British Army claimed that the men were attacking them with guns or bombs, while eyewitnesses insisted that both were unarmed. The Social Democratic and Labour Party

The Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) ( ga, Páirtí Sóisialta Daonlathach an Lucht Oibre) is a social-democratic and Irish nationalist political party in Northern Ireland. The SDLP currently has eight members in the Northern Ireland ...

(SDLP), the newly formed party of which John Hume and Ivan Cooper were leading members, withdrew from Stormont in protest, but among residents there was a perception that moderate policies had failed. The result was a surge of support for the IRA. The Provisionals held a meeting the following Sunday at which they called on people to "join the IRA". Following the meeting, people queued up to join, and there was large-scale rioting. The British Army post at Bligh's Lane came under sustained attack, and troops there and around the city came under fire from the IRA.

Internment and the third Free Derry

The increasing violence in Derry and elsewhere led to increasing speculation thatinternment

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simpl ...

would be introduced in Northern Ireland, and on 9 August 1971 hundreds of republicans and nationalists were arrested in dawn raids. In Derry, residents came out onto the streets to resist the arrests, and fewer people were taken there than elsewhere; nevertheless leading figures including Seán Keenan and Johnnie White were interned. In response, barricades were erected once again and the third Free Derry came into existence. Unlike its predecessors, this Free Derry was marked by a strong IRA presence, both Official and Provisional. It was defended by armed paramilitaries—a no-go area

A "no-go area" or "no-go zone" is a neighborhood or other geographic area where some or all outsiders are either physically prevented from entering or can enter at risk. The term includes exclusion zones, which are areas that are officially kept o ...

, one in which British security forces were unable to operate.Ó Dochartaigh, Niall, ''From Civil Rights to Armalites'', p. 236

Gun attacks on the British Army increased. Six soldiers were wounded in the first day after internment, and shortly afterwards a soldier was killed—the first to be killed by either IRA in Derry. The army moved into the area in force on 18 August to dismantle the barricades. A gun battle ensued in which a young Provisional IRA officer, Eamonn Lafferty, was killed. A crowd staging a sit-down protest was hosed down and the protesters, including John Hume and Ivan Cooper, arrested. With barricades re-appearing as quickly as they were removed, the army eventually abandoned their attempt.

The Derry Provisionals had little contact with the IRA elsewhere. They had few weapons (about twenty) which they used mainly for sniping. At the same time, they launched their bombing campaign in Derry. Unlike in Belfast, they were careful to avoid killing or injuring innocent people. Eamonn McCann wrote that "the Derry Provos, under Martin McGuinness, had managed to bomb the city centre until it looked as if it had been hit from the air without causing any civilian casualties."

Although both IRAs operated openly, neither was in control of Free Derry. The barricades were manned by unarmed 'auxiliaries'. Crime was dealt with by a volunteer force called the Free Derry Police, which was headed by Tony O'Doherty

Anthony "Tony" O'Doherty (born 23 April 1947) is a Northern Irish former footballer and football manager.

A native of Creggan, Derry, O'Doherty played for Coleraine FC, Derry City FC, Finn Harps, Dundalk FC and briefly for Ballymena United and ...

, a Derry footballer

A football player or footballer is a sportsperson who plays one of the different types of football. The main types of football are association football, American football, Canadian football, Australian rules football, Gaelic football, rugby ...

and Northern Ireland International.

Bloody Sunday

An anti-internment protest organised by NICRA at Magilligan Camp in January 1972 was met with violence from the

An anti-internment protest organised by NICRA at Magilligan Camp in January 1972 was met with violence from the 1st Battalion, The Parachute Regiment

The 1st Battalion, Parachute Regiment (1 PARA), is a battalion of the British Army's Parachute Regiment. Along with various other regiments and corps from across the British Armed Forces, it is part of Special Forces Support Group.

A special ...

(1 Para). NICRA had organised a march from the Creggan to Derry city centre, in defiance of a ban, on the following Sunday, 30 January 1972. Both IRAs were asked, and agreed, to suspend operations on that day to ensure the march passed off peacefully. The British Army erected barricades around the Free Derry area to prevent marchers from reaching the city centre. On the day, march organisers turned the march away from the barriers and up to Free Derry Corner

Free Derry Corner is a historical landmark in the Bogside neighbourhood of Derry, Northern Ireland, which lies in the intersection of the Lecky Road, Rossville Street and Fahan Street. A free-standing gable wall commemorates Free Derry, a self ...

, but some youths proceeded to the barrier at William Street and stoned soldiers. Troops from 1 Para then moved into Free Derry and opened fire, killing thirteen people, all of whom were subsequently found to be unarmed. A fourteenth shooting victim died four months later in June 1972. Like the killing of Cusack and Beattie the previous year, Bloody Sunday

Bloody Sunday may refer to:

Historical events Canada

* Bloody Sunday (1923), a day of police violence during a steelworkers' strike for union recognition in Sydney, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia

* Bloody Sunday (1938), police violence aga ...

had the effect of hugely increasing recruitment to the IRA, even among people who previously would have been 'moderates'.

February – July 1972

Both the Provisional and Official IRA stepped up attacks after Bloody Sunday, with the tacit support of the residents. Local feelings changed, however, with the killing of Ranger William Best by the Official IRA. Best was a 19-year-old local man who was home on leave from the British Army at his parents' house in the Creggan. He was abducted, interrogated and shot. The following day 500 women marched to the Republican Club offices in protest. Nine days later, on 29 May, the Official IRA declared a ceasefire. The Provisional IRA initially stated that they would not follow suit, but after informal approaches to the British Government they announced a ceasefire from 26 June. Martin McGuinness was the Derry representative in a party of senior Provisionals who travelled to London for talks withWilliam Whitelaw

William Stephen Ian Whitelaw, 1st Viscount Whitelaw, (28 June 1918 – 1 July 1999) was a British Conservative Party politician who served in a wide number of Cabinet positions, most notably as Home Secretary from 1979 to 1983 and as ''de fac ...

, the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland

A secretary, administrative professional, administrative assistant, executive assistant, administrative officer, administrative support specialist, clerk, military assistant, management assistant, office secretary, or personal assistant is a w ...

. The talks were not resumed after the ending of the truce following a violent confrontation in Belfast when troops prevented Catholic families from taking over houses in the Lenadoon estate.

Political pressure for the action against the "no-go" areas increased after the events of Bloody Friday in Belfast. A British Army attack was considered inevitable, and the IRA took the decision not to resist it. On 31 July 1972, Operation Motorman

Operation Motorman was a large operation carried out by the British Army ( HQ Northern Ireland) in Northern Ireland during the Troubles. The operation took place in the early hours of 31 July 1972 with the aim of retaking the "no-go areas" (ar ...

was launched when thousands of British troops, equipped with armoured cars and armoured bulldozers ( AVREs), dismantled the barricades and occupied the area.

Subsequent history

After Operation Motorman, the British Army controlled the Bogside and Creggan by stationing large numbers of troops within the area, by conducting large-scale 'search' operations that were in fact undertaken for purposes of intelligence gathering, and by setting up over a dozen covert observation posts.Ó Dochartaigh, Niall, ''From Civil Rights to Armalites'' pp. 250–1 Over the following years IRA violence in the city was contained to the point where it was possible to believe 'the war was over' in the area, although there were still frequent street riots. Nationalists—even those who did not support the IRA—remained bitterly opposed to the army and to the state. Many of the residents' original grievances were addressed with the passing of theLocal Government Act (Northern Ireland) 1972

The Local Government (Northern Ireland) Act 1972 (1972 c. 9) was an Act of the Parliament of Northern Ireland that constituted district councils to administer the twenty-six local government districts created by the Local Government (Boundaries) ...

, which redrew the electoral boundaries and introduced universal adult suffrage based on the single transferable vote

Single transferable vote (STV) is a multi-winner electoral system in which voters cast a single vote in the form of a ranked-choice ballot. Voters have the option to rank candidates, and their vote may be transferred according to alternate p ...

. Elections were held in May 1973. Nationalists gained a majority on the council for the first time since 1923. Since then the area has been extensively redeveloped, with modern housing replacing the old houses and flats. The Free Derry era is commemorated by the Free Derry wall, the murals of the Bogside Artists

The Bogside Artists are a trio of mural painters from Derry, Northern Ireland, consisting of brothers Tom and William Kelly, and Kevin Hasson (b. 8 January 1958). Their most famous work, a series of outdoor murals called the People's Gallery, is ...

and the Museum of Free Derry

The Museum of Free Derry is a museum located in Derry, Northern Ireland that focuses on the 1960s civil rights era known as The Troubles and the Free Derry Irish nationalist movement in the early 1970s. Located in the Bogside

The Bogside i ...

.Davenport, Fionn et al., ''Ireland'', Lonely Planet

Lonely Planet is a travel guide book publisher. Founded in Australia in 1973, the company has printed over 150 million books.

History Early years

Lonely Planet was founded by married couple Maureen and Tony Wheeler. In 1972, they embarked ...

, Melbourne, 2006,p. 629

See also

*History of Northern Ireland

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbrella term comprising past events as well ...

* History of Derry

The earliest references to the history of Derry date to the 6th century when a monastery was founded there; however, archaeological sites and objects predating this have been found. The name Derry comes from the Old Irish word ''Daire'' (modern: ...

* Northern Ireland Civil Rights Movement

The Northern Ireland civil rights movement dates to the early 1960s, when a number of initiatives emerged in Northern Ireland which challenged the inequality and discrimination against ethnic Irish Catholics that was perpetrated by the Ulster Pr ...

* Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone

The Capitol Hill Occupied Protest or the Capitol Hill Organized Protest (CHOP), originally Free Capitol Hill and later the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone (CHAZ), was an Occupation (protest), occupation protest and self-declared permanent autonomo ...

References

Bibliography

* Devlin, Bernadette, ''The Price of my Soul'', 1st edition, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1969 * Lord Cameron, ''Disturbances in Northern Ireland'', HMSO, Belfast, 1969CAIN Web Service

* McCann, Eamonn, ''War and an Irish Town'', 2nd edition, Pluto Press, London, 1980, * Ó Dochartaigh, Niall, ''From Civil Rights to Armalites: Derry and the Birth of the Irish Troubles'', Palgrave MacMillan, Basingstoke, 2005, * Office of the Police Ombudsman for Northern Ireland, ''Report of the Police Ombudsman for Northern Ireland into a complaint made by the Devenny family on 20 April 2001'', Belfast, 2001

* Farrell, Sean, ''Rituals and Riots: Sectarian Violence and Political Culture in Ulster, 1784–1886'',The University Press of Kentucky 2000,

External links

* Museum of Free DerryMuseum of Free Derry

{{Coord, 54.997, -7.326, display=title The Troubles in Derry (city) 1969 establishments in Northern Ireland 1972 disestablishments in Northern Ireland