Frederick Funston on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

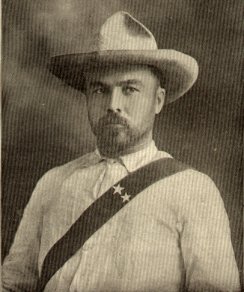

Frederick Funston (November 9, 1865 – February 19, 1917), also known as Fighting Fred Funston, was a

He eventually joined the Cuban Liberation Army that was fighting for independence from

He eventually joined the Cuban Liberation Army that was fighting for independence from

In 1906, Funston was commander of the Presidio of San Francisco when the

In 1906, Funston was commander of the Presidio of San Francisco when the

;Rank and organization:

:Colonel, 20th Kansas Volunteer Infantry.

;Place and date:

:At Rio Grande de la Pampanga,

;Rank and organization:

:Colonel, 20th Kansas Volunteer Infantry.

;Place and date:

:At Rio Grande de la Pampanga,

"Funston, Frederick"

in ''The National Cyclopedia of American Biography,'' Vol. 11, pp. 40–41.

Frederick Funston

are available on Kansas Memory, the digital portal of the Kansas Historical Society, Topeka, Kansas

Frederick Funston papers

are available at the Kansas Historical Society, Topeka, Kansas * {{DEFAULTSORT:Funston, Frederick 1865 births 1906 San Francisco earthquake 1917 deaths United States Army Medal of Honor recipients American military personnel of the Banana Wars American military personnel of the Philippine–American War American military personnel of the Spanish–American War United States Army generals University of Kansas alumni Commandants of the United States Army Command and General Staff College Philippine–American War recipients of the Medal of Honor Burials at San Francisco National Cemetery People from New Carlisle, Ohio People from Iola, Kansas Military personnel from Ohio American expatriates in the Philippines 19th-century United States Army personnel 20th-century United States Army personnel Phi Delta Theta members

general

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

in the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

, best known for his roles in the Spanish–American War

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Restoration (Spain), Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine (1889), USS ''Maine'' in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the ...

and the Philippine–American War

The Philippine–American War, known alternatively as the Philippine Insurrection, Filipino–American War, or Tagalog Insurgency, emerged following the conclusion of the Spanish–American War in December 1898 when the United States annexed th ...

; he received the Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest Awards and decorations of the United States Armed Forces, military decoration and is awarded to recognize American United States Army, soldiers, United States Navy, sailors, Un ...

for his actions during the latter conflict.

Early life, education, and work

Funston was born in 1865 inNew Carlisle, Ohio

New Carlisle ( ) is a city in Clark County, Ohio, United States. The population was 5,559 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Springfield, Ohio metropolitan area.

History

New Carlisle was originally called Monroe, and under the latter name w ...

, to Edward H. Funston and Anne Eliza ''Mitchell'' Funston. In 1867, his family moved to Allen County, Kansas. His father was elected to the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Artic ...

in 1884 and served five terms.

Funston was a slight individual who stood tall and weighed when he applied in 1886 to the United States Military Academy; he was rejected. Funston graduated from Iola High School in 1886. He attended the University of Kansas from 1886 to 1890. While there, he joined the Phi Delta Theta fraternity and became friends with William Allen White, who became a writer and won a Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prizes () are 23 annual awards given by Columbia University in New York City for achievements in the United States in "journalism, arts and letters". They were established in 1917 by the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made his fo ...

. He worked as a trainman for the Santa Fe Railroad before becoming a reporter in Kansas City, Missouri

Kansas City, Missouri, abbreviated KC or KCMO, is the largest city in the U.S. state of Missouri by List of cities in Missouri, population and area. The city lies within Jackson County, Missouri, Jackson, Clay County, Missouri, Clay, and Pl ...

, in 1890.

Career

After one year as ajournalist

A journalist is a person who gathers information in the form of text, audio or pictures, processes it into a newsworthy form and disseminates it to the public. This is called journalism.

Roles

Journalists can work in broadcast, print, advertis ...

, Funston moved into more scientific exploration, focusing primarily on botany

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

. First serving as part of an exploring and surveying expedition in Death Valley, California. In 1891, he then traveled to Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

to spend the next two years in work for the United States Department of Agriculture

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is an executive department of the United States federal government that aims to meet the needs of commercial farming and livestock food production, promotes agricultural trade and producti ...

.

Cuba

He eventually joined the Cuban Liberation Army that was fighting for independence from

He eventually joined the Cuban Liberation Army that was fighting for independence from Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

in 1896 after having been inspired to join following a rousing speech given by Gen. Daniel E. Sickles at Madison Square Garden

Madison Square Garden, colloquially known as the Garden or by its initials MSG, is a multi-purpose indoor arena in New York City. It is located in Midtown Manhattan between Seventh Avenue (Manhattan), Seventh and Eighth Avenue (Manhattan), Eig ...

in New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

.

After a bout of malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

, Funston's weight dropped to an alarming 95 lb. The Cubans gave him a leave of absence. When Funston returned to the United States, he was commissioned as a colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

of the 20th Kansas Infantry Regiment in the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

on May 13, 1898, in the early days of the Spanish–American War

The Spanish–American War (April 21 – August 13, 1898) was fought between Restoration (Spain), Spain and the United States in 1898. It began with the sinking of the USS Maine (1889), USS ''Maine'' in Havana Harbor in Cuba, and resulted in the ...

. In the fall, he met Eda Blankart at a patriotic gathering, and after a brief courtship, they married on October 25, 1898. Within two weeks of the marriage, he had to depart for war, landing in the Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

as part of the U.S. forces that would become engaged in the Philippine–American War.

Philippines

Funston was in command in various engagements with Filipino nationalists. In April 1899, he took a Filipino position at Calumpit by swimming the Bagbag River, then crossing the Pampanga River under heavy fire. For his bravery, Funston was soon promoted to the rank of brigadier general of volunteers and awarded the Medal of Honor on February 14, 1900. Funston played the key role in planning and carrying out the capture of Filipino PresidentEmilio Aguinaldo

Emilio Aguinaldo y Famy (: March 22, 1869February 6, 1964) was a Filipino revolutionary, statesman, and military leader who became the first List of presidents of the Philippines, president of the Philippines (1899–1901), and the first pre ...

on March 23, 1901, at Palanan. The capture of Aguinaldo made Funston a national hero in the U.S., although the anti-imperialist movement criticized him when the details of Aguinaldo's capture became known. Funston's party, escorted by a company of Macabebe Scouts, had gained access to Aguinaldo's camp by posing as prisoners. Funston's mission to capture Aguinaldo brought him a Regular Army

A regular army is the official army of a state or country (the official armed forces), contrasting with irregular forces, such as volunteer irregular militias, private armies, mercenaries, etc. A regular army usually has the following:

* a ...

commission just as he was scheduled to be mustered out of the volunteer service and, at only 35 years old, Funston was appointed a brigadier general in the Regular Army in recognition of his capture of Aguinaldo.

In 1902, Funston returned to the United States to increased public opposition to the Philippine–American War, and became the focus of a great deal of controversy. Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by the pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, and essayist. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has produced," with William Fau ...

, a strong opponent of U.S. imperialism

Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of Power (international relations), power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power (diplomatic power and cultura ...

, published a sarcasm-filled denunciation of Funston's mission and methods under the title " A Defence of General Funston" in the ''North American Review

The ''North American Review'' (''NAR'') was the first literary magazine in the United States. It was founded in Boston in 1815 by journalist Nathan Hale (journalist), Nathan Hale and others. It was published continuously until 1940, after which i ...

''. Poet Ernest Crosby also wrote a satirical, anti-imperialist novel, '' Captain Jinks, Hero'', that parodied the career of Funston.

Funston was considered a useful advocate for American expansionism

Expansionism refers to states obtaining greater territory through military Imperialism, empire-building or colonialism.

In the classical age of conquest moral justification for territorial expansion at the direct expense of another established p ...

; however, when he publicly made insulting remarks about anti-imperialist Republican Senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or Legislative chamber, chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the Ancient Rome, ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior ...

George Frisbie Hoar

George Frisbie Hoar (August 29, 1826 – September 30, 1904) was an American attorney and politician, represented Massachusetts in the United States Senate from 1877 until his death in 1904. He belonged to an extended family that became politic ...

of Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

, mocking his "overheated conscience" in Denver, just prior to a planned visit to Boston, the epicenter of the U.S. anti-imperialism movement, President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

denied his furlough request and ordered him to be silenced and officially reprimanded.

United States and overseas again

In 1906, Funston was commander of the Presidio of San Francisco when the

In 1906, Funston was commander of the Presidio of San Francisco when the 1906 San Francisco earthquake

At 05:12 AM Pacific Time Zone, Pacific Standard Time on Wednesday, April 18, 1906, the coast of Northern California was struck by a major earthquake with an estimated Moment magnitude scale, moment magnitude of 7.9 and a maximum Mercalli inte ...

hit. He declared martial law

Martial law is the replacement of civilian government by military rule and the suspension of civilian legal processes for military powers. Martial law can continue for a specified amount of time, or indefinitely, and standard civil liberties ...

, although he did not have the authority to do so, and martial law was never officially declared. Funston attempted to defend the city from the spread of fire, and directed the demolition of buildings using explosives to create firebreaks, but his orders often resulted in more fires. Funston gave orders to shoot all looters on sight; however, these orders resulted in numerous cases of innocent people being shot.

At the time, local officials praised Funston's actions in the earthquake and fire emergency. Historians have since taken issue with some of his actions in the disaster, arguing that he should not have used military forces in a peacetime emergency.

From December 1907 through March 1908, Funston was in charge of troops at the Goldfield mining center in Esmeralda County, Nevada, where the army put down a labor strike by the Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), whose members are nicknamed "Wobblies", is an international labor union founded in Chicago, United States in 1905. The nickname's origin is uncertain. Its ideology combines general unionism with indu ...

.

After two years as commandant of the Army Service School in Fort Leavenworth

Fort Leavenworth () is a United States Army installation located in Leavenworth County, Kansas, in the city of Leavenworth, Kansas, Leavenworth. Built in 1827, it is the second oldest active United States Army post west of Washington, D.C., an ...

, Funston served three years as commander of the Department of Luzon in the Philippines. He was briefly shifted to the same role in the Hawaiian Department (April 3, 1913, to January 22, 1914).

Funston was active in the United States' conflict with Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

in 1914 to 1916, as commanding general of the army's Southern Department, being promoted to major general in November 1914. He was commander of Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio

San Antonio ( ; Spanish for " Saint Anthony") is a city in the U.S. state of Texas and the most populous city in Greater San Antonio. San Antonio is the third-largest metropolitan area in Texas and the 24th-largest metropolitan area in the ...

, Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

, where he prodded Second Lieutenant Dwight Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

into becoming the football coach for the Peacock Military Academy and later approved Eisenhower's request of leave for his wedding. He occupied the city of Veracruz

Veracruz, formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entit ...

. He commanded all forces involved in the hunt for Pancho Villa

Francisco "Pancho" Villa ( , , ; born José Doroteo Arango Arámbula; 5 June 1878 – 20 July 1923) was a Mexican revolutionary and prominent figure in the Mexican Revolution. He was a key figure in the revolutionary movement that forced ...

, and provided security for the United States border with Mexico during the " Bandit War".

World War I and death

Just prior to the American entry into World War I, in April 1917, PresidentWoodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

had favored Funston to head any American Expeditionary Force

The American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) was a formation of the United States Armed Forces on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front during World War I, composed mostly of units from the United States Army, U.S. Army. The AEF was establis ...

(AEF) that would be sent overseas. Funston's intense focus on his work led to health problems: first, with a case of indigestion in January 1917, followed a month later by a fatal heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when Ischemia, blood flow decreases or stops in one of the coronary arteries of the heart, causing infarction (tissue death) to the heart muscle. The most common symptom ...

at the age of 51 in San Antonio, Texas

San Antonio ( ; Spanish for "Anthony of Padua, Saint Anthony") is a city in the U.S. state of Texas and the most populous city in Greater San Antonio. San Antonio is the List of Texas metropolitan areas, third-largest metropolitan area in Texa ...

.

In the moments before his death, Funston was relaxing in the lobby of the St. Anthony Hotel in San Antonio, listening to an orchestra play '' The Blue Danube'' waltz

The waltz ( , meaning "to roll or revolve") is a ballroom dance, ballroom and folk dance, in triple (3/4 time, time), performed primarily in closed position. Along with the ländler and allemande, the waltz was sometimes referred to by the ...

. After commenting, "How beautiful it all is," he collapsed from a massive heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when Ischemia, blood flow decreases or stops in one of the coronary arteries of the heart, causing infarction (tissue death) to the heart muscle. The most common symptom ...

and died. He was holding six-year-old Inez Harriett Silverberg in his arms.

Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American general who served as a top commander during World War II and the Korean War, achieving the rank of General of the Army (United States), General of the Army. He served with dis ...

, then a major, had the unpleasant duty of breaking the news to President Wilson and Secretary of War Newton D. Baker. As MacArthur explained in his memoirs, "had the voice of doom spoken, the result could not have been different. The silence seemed like that of death itself. You could hear your own breathing."

Funston lay in state at both the Alamo and the City Hall Rotunda in San Francisco. The latter honor gave him the distinction of being the first person to be recognized with this tribute, with his subsequent burial taking place in San Francisco National Cemetery. After his death, the position of AEF commander went to Major General John J. Pershing, who, as commanding general of the Punitive Expedition in 1916, had been Funston's subordinate. The Lake Merced military reservation (part of San Francisco's coastal defenses) was renamed Fort Funston in his honor, while the training camp built in 1917 next to Fort Riley in Kansas (which became the second-largest World War I camp) was named Camp Funston

Camp Funston is a U.S. Army training camp located on the grounds of Fort Riley, southwest of Manhattan, Kansas. The camp was named for Brigadier General Frederick Funston (1865–1917). It is one of sixteen such camps that were established at ...

. San Francisco's Funston Park and Funston Avenue are named for him, as is Funston Avenue in his hometown of New Carlisle, Ohio, and Funston Avenue near Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio. In Hawaii, Funston Road at Schofield Barracks and Funston Road at Fort Shafter are named after him. Funston's daughter, and his son and grandson, both of whom served in the United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the Air force, air service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is one of the six United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Tracing its ori ...

, were later interred with him.

Medal of Honor citation

;Rank and organization:

:Colonel, 20th Kansas Volunteer Infantry.

;Place and date:

:At Rio Grande de la Pampanga,

;Rank and organization:

:Colonel, 20th Kansas Volunteer Infantry.

;Place and date:

:At Rio Grande de la Pampanga, Luzon

Luzon ( , ) is the largest and most populous List of islands in the Philippines, island in the Philippines. Located in the northern portion of the List of islands of the Philippines, Philippine archipelago, it is the economic and political ce ...

, Philippine Islands, April 27, 1899.

;Entered service at:

: Iola, Kansas.

;Birth:

:New Carlisle, Ohio

New Carlisle ( ) is a city in Clark County, Ohio, United States. The population was 5,559 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Springfield, Ohio metropolitan area.

History

New Carlisle was originally called Monroe, and under the latter name w ...

.

;Date of issue:

:February 14, 1900.

;Citation:

:Crossed the river on a raft and by his skill and daring enabled the general commanding to carry the enemy's entrenched position on the north bank of the river and to drive him with great loss from the important strategic position of Calumpit.

Legacy

Fort Funston inSan Francisco, California

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

, is named for him.

Streets are named for Funston in San Francisco, New Carlisle, Ohio

New Carlisle ( ) is a city in Clark County, Ohio, United States. The population was 5,559 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Springfield, Ohio metropolitan area.

History

New Carlisle was originally called Monroe, and under the latter name w ...

, Reading, Pennsylvania, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, Pacific Grove, California, and Hollywood, Florida

Hollywood is a city in Broward County, Florida, United States. It is a suburb in the Miami metropolitan area. The population of Hollywood was 153,067 as of 2020, making it the Broward County#Communities, third-largest city in Broward County, th ...

. Part of Fort Riley, Kansas, was also named for him.

Frederick Funston Elementary School in Chicago, Illinois is a K-8 Chicago Public School In the Logan Square neighborhood. It is home to the Funston Falcons.

In popular culture

* He was portrayed by Troy Montero in the 2012 Filipino film '' El Presidente''. * He was portrayed by Pablo Espinosa in the 1997 TNT television series ''Rough Riders''. * He was mentioned once in ''The Woggle-Bug Book'' by L. Frank Baum published in 1905.See also

* List of Philippine–American War Medal of Honor recipients * A Defence of General Funston (Mark Twain's satirical essay).References

:Further reading

"Funston, Frederick"

in ''The National Cyclopedia of American Biography,'' Vol. 11, pp. 40–41.

External links

* * * Photos and other items related tFrederick Funston

are available on Kansas Memory, the digital portal of the Kansas Historical Society, Topeka, Kansas

Frederick Funston papers

are available at the Kansas Historical Society, Topeka, Kansas * {{DEFAULTSORT:Funston, Frederick 1865 births 1906 San Francisco earthquake 1917 deaths United States Army Medal of Honor recipients American military personnel of the Banana Wars American military personnel of the Philippine–American War American military personnel of the Spanish–American War United States Army generals University of Kansas alumni Commandants of the United States Army Command and General Staff College Philippine–American War recipients of the Medal of Honor Burials at San Francisco National Cemetery People from New Carlisle, Ohio People from Iola, Kansas Military personnel from Ohio American expatriates in the Philippines 19th-century United States Army personnel 20th-century United States Army personnel Phi Delta Theta members