Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, – February 20, 1895) was an American

social reformer,

abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from

slavery in Maryland, he became a national leader of the

abolitionist movement

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

in

Massachusetts and New York, becoming famous for his oratory and incisive

antislavery writings. Accordingly, he was described by abolitionists in his time as a living counterexample to enslavers' arguments that enslaved people lacked the intellectual capacity to function as independent American citizens.

Northerners at the time found it hard to believe that such a great orator had once been enslaved. It was in response to this disbelief that Douglass wrote his first autobiography.

Douglass wrote three autobiographies, describing his experiences as an enslaved person in his ''

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave'' (1845), which became a bestseller and was influential in promoting the cause of abolition, as was his second book, ''

My Bondage and My Freedom'' (1855). Following the

Civil War, Douglass was an active campaigner for the rights of freed slaves and wrote his last autobiography, ''

Life and Times of Frederick Douglass''. First published in 1881 and revised in 1892, three years before his death, the book covers his life up to those dates. Douglass also actively supported

women's suffrage, and he held several public offices. Without his knowledge or consent, Douglass became the first African American nominated for vice president of the United States,

as the running mate of

Victoria Woodhull on the

Equal Rights Party ticket.

Douglass believed in

dialogue

Dialogue (sometimes spelled dialog in American English) is a written or spoken conversational exchange between two or more people, and a literary and theatrical form that depicts such an exchange. As a philosophical or didactic device, it is c ...

and in making alliances across racial and ideological divides, as well as in the

liberal values of the

U.S. Constitution. When radical abolitionists, under the motto "No Union with Slaveholders", criticized Douglass's willingness to engage in dialogue with slave owners, he replied: "I would unite with anybody to do right and with nobody to do wrong."

Life as an enslaved person

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey was born

enslaved on the

Eastern Shore Eastern Shore may refer to:

* Eastern Shore (Nova Scotia), a region

* Eastern Shore (electoral district), a provincial electoral district in Nova Scotia

* Eastern Shore of Maryland, a region

* Eastern Shore of Virginia, a region

* Eastern Shore (Al ...

of the

Chesapeake Bay in

Talbot County, Maryland. The

plantation was between

Hillsboro and

Cordova;

"I was born in Tuckahoe, near Hillsborough, and about twelve miles from Easton, in Talbot County, Maryland." (Tuckahoe refers to the area west of Tuckahoe Creek in Talbot County.) his birthplace was likely his grandmother's cabin east of Tappers Corner, and west of

Tuckahoe Creek.

[Frederick Douglass , Museums and Gardens]

" ''Talbot Historic Society''. 2016. Archived from th

original

on December 22, 2016. Retrieved December 22, 2016. In his first autobiography, Douglass stated: "I have no accurate knowledge of my age, never having seen any authentic record containing it."

Frederick Douglass began his own story thusly: "I was born in Tuckahoe, near Hillsborough, and about twelve miles from Easton, in Talbot County, Maryland." (Tuckahoe is not a town; it refers to the area west of Tuckahoe Creek in Talbot County.) In successive autobiographies, Douglass gave more precise estimates of when he was born, his final estimate being 1817. In successive autobiographies, he gave more precise estimates of when he was born, his final estimate being 1817.

However, based on the extant records of Douglass's former owner, Aaron Anthony, historian Dickson J. Preston determined that Douglass was born in February 1818.

Though the exact date of his birth is unknown, he chose to celebrate February 14 as his birthday, remembering that his mother called him her "Little

Valentine

A valentine is a card or gift given on Valentine's Day, or one's sweetheart.

Valentine or Valentines may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Valentine (name), a given name and a surname, including a list of people and fictional char ...

."

Birth family

Douglass was of

mixed race, which likely included Native American and

African

African or Africans may refer to:

* Anything from or pertaining to the continent of Africa:

** People who are native to Africa, descendants of natives of Africa, or individuals who trace their ancestry to indigenous inhabitants of Africa

*** Ethn ...

on his mother's side, as well as European. In contrast, his father was "almost certainly white", according to historian

David W. Blight in his 2018 biography of Douglass. Douglass said his mother Harriet Bailey gave him his name Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey and, after he escaped to the North in September 1838, he took the surname

Douglass, having already dropped his two middle names.

He later wrote of his earliest times with his mother:

The opinion was...whispered that my master was my father; but of the correctness of this opinion I know nothing. ... My mother and I were separated when I was but an infant. ... It is a common custom, in the part of Maryland from which I ran away, to part children from their mothers at a very early age. ... I do not recollect of ever seeing my mother by the light of day. She was with me in the night. She would lie down with me, and get me to sleep, but long before I waked she was gone.

After separation from his mother during infancy, young Frederick lived with his

maternal grandmother Betsy Bailey, who was also enslaved, and his maternal grandfather Isaac, who was

free

Free may refer to:

Concept

* Freedom, having the ability to do something, without having to obey anyone/anything

* Freethought, a position that beliefs should be formed only on the basis of logic, reason, and empiricism

* Emancipate, to procur ...

. Betsy would live until 1849. Frederick's mother remained on the plantation about away, only visiting Frederick a few times before her death when he was 7 years old.

Returning much later, about 1883, to purchase land in Talbot County that was meaningful to him, he was invited to address "a colored school":

Early learning and experience

The Auld family

At the age of 6, Douglass was separated from his grandparents and moved to the

Wye House plantation, where Aaron Anthony worked as overseer.

After Anthony died in 1826, Douglass was given to Lucretia Auld, wife of Thomas Auld, who sent him to serve Thomas' brother Hugh Auld and his wife Sophia Auld in

Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was d ...

. From the day he arrived, Sophia saw to it that Douglass was properly fed and clothed, and that he slept in a bed with sheets and a blanket.

Douglass described her as a kind and tender-hearted woman, who treated him "as she supposed one human being ought to treat another." Douglass felt that he was lucky to be in the city, where he said enslaved people were almost

freemen, compared to those on plantations.

When Douglass was about 12, Sophia Auld began teaching him the

alphabet. Hugh Auld disapproved of the tutoring, feeling that

literacy would encourage enslaved people to desire freedom. Douglass later referred to this as the "first decidedly

antislavery lecture" he had ever heard. "'Very well, thought I,'" wrote Douglass. "'Knowledge unfits a child to be a slave.' I instinctively assented to the proposition, and from that moment I understood the direct pathway from slavery to freedom."

Under her husband's influence, Sophia came to believe that education and slavery were incompatible and one day snatched a newspaper away from Douglass. She stopped teaching him altogether and hid all potential reading materials, including her Bible, from him.

In his autobiography, Douglass related how he learned to read from white children in the neighborhood, and by observing the writings of the men with whom he worked.

Douglass continued, secretly, to teach himself to read and write. He later often said, "knowledge is the pathway from slavery to freedom." As Douglass began to read newspapers, pamphlets, political materials, and books of every description, this new realm of thought led him to question and condemn the institution of slavery. In later years, Douglass credited ''

The Columbian Orator

''The Columbian Orator'' is a collection of political essays, poems, and dialogues collected and written by Caleb Bingham. Published in 1797, it includes speeches by George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and some imagined speeches by historical fi ...

'', an anthology that he discovered at about age 12, with clarifying and defining his views on freedom and human rights. First published in 1797, the book is a classroom reader, containing essays, speeches, and dialogues, to assist students in learning reading and grammar. He later learned that his mother had also been literate, about which he would later declare:

I am quite willing, and even happy, to attribute any love of letters I possess, and for which I have got—despite of prejudices—only too much credit, not to my admitted Anglo-Saxon paternity, but to the native genius of my sable, unprotected, and uncultivated mother—a woman, who belonged to a race whose mental endowments it is, at present, fashionable to hold in disparagement and contempt.

William Freeland

When Douglass was hired out to William Freeland, he "gathered eventually more than thirty male slaves on Sundays, and sometimes even on weeknights, in a Sabbath literacy school."

Edward Covey

In 1833, Thomas Auld took Douglass back from Hugh ("

a means of punishing Hugh," Douglass later wrote). Thomas sent Douglass to work for

Edward Covey

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sa ...

, a poor farmer who had a reputation as a "slave-breaker". He

whipped Douglass so frequently that his wounds had little time to heal. Douglass later said the frequent whippings broke his body, soul, and spirit. The 16-year-old Douglass finally rebelled against the beatings, however, and fought back. After Douglass won a physical confrontation, Covey never tried to beat him again.

Recounting his beatings at Covey's farm in ''Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave'', Douglass described himself as "a man transformed into a brute!" Still, Douglass came to see his physical fight with Covey as life-transforming, and introduced the story in his autobiography as such: "You have seen how a man was made a slave; you shall see how a slave was made a man."

From slavery to freedom

Douglass first tried to escape from Freeland, who had hired him from his owner, but was unsuccessful. In 1837, Douglass met and fell in love with

Anna Murray, a

free black woman in Baltimore about five years his senior. Her free status strengthened his belief in the possibility of gaining his own freedom. Murray encouraged him and supported his efforts by aid and money.

On September 3, 1838, Douglass successfully escaped by boarding a northbound train of the

Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad. The area where he boarded was thought to be a short distance east of the train depot, in a recently developed neighborhood between the modern neighborhoods of

Harbor East

Inner Harbor East, now more recently referred to more commonly as simply as Harbor East, is a relatively new mixed-use development project in Baltimore, Maryland, United States along the northern shoreline of the Northwest Branch of the Pataps ...

and

Little Italy. This depot was at President and Fleet Streets, east of

"The Basin" of the

Baltimore harbor

Helen Delich Bentley Port of Baltimore is a shipping port along the tidal basins of the three branches of the Patapsco River in Baltimore, Maryland on the upper northwest shore of the Chesapeake Bay. It is the nation's largest port facilities fo ...

, on the northwest branch of the

Patapsco River

The Patapsco River mainstem is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed April 1, 2011 river in central Maryland that flows into the Chesapeake Bay. The river's tidal port ...

. Research cited in 2021, however, suggests that Douglass in fact boarded the train at the Canton Depot of the Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore Railroad on Boston Street, in the Canton neighborhood of Baltimore, further east.

Douglass reached

Havre de Grace, Maryland

Havre de Grace (), abbreviated HdG, is a city in Harford County, Maryland, Harford County, Maryland. It is situated at the mouth of the Susquehanna River and the head of Chesapeake Bay. It is named after the port city of Le Havre, France, which ...

, in

Harford County

Harford County is located in the U.S. state of Maryland. As of the 2020 census, the population was 260,924. Its county seat is Bel Air. Harford County is included in the Baltimore-Columbia-Towson, MD Metropolitan Statistical Area, which is al ...

, in the northeast corner of the state, along the southwest shore of the

Susquehanna River

The Susquehanna River (; Lenape: Siskëwahane) is a major river located in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, overlapping between the lower Northeast and the Upland South. At long, it is the longest river on the East Coast of the ...

, which flowed into the

Chesapeake Bay. Although this placed him only some from the Maryland–Pennsylvania state line, it was easier to continue by rail through Delaware, another slave state. Dressed in a sailor's

uniform provided to him by Murray, who also gave him part of her savings to cover his travel costs, he carried identification papers and

protection papers

Protection papers, also known as "Seamen Protection Papers", "Seamen Protection Certificates", or "Sailor's Protection Papers", were issued to American seamen during the last part of the 18th century through the first half of the 20th century. Thes ...

that he had obtained from a free black seaman.

Douglass crossed the wide Susquehanna River by the railroad's steam-ferry at Havre de Grace to

Perryville on the opposite shore, in

Cecil County

Cecil County () is a county located in the U.S. state of Maryland at the northeastern corner of the state, bordering both Pennsylvania and Delaware. As of the 2020 census, the population was 103,725. The county seat is Elkton. The county was ...

, then continued by train across the state line to

Wilmington, Delaware, a large port at the head of the

Delaware Bay. From there, because the rail line was not yet completed, he went by

steamboat

A steamboat is a boat that is marine propulsion, propelled primarily by marine steam engine, steam power, typically driving propellers or Paddle steamer, paddlewheels. Steamboats sometimes use the ship prefix, prefix designation SS, S.S. or S/S ...

along the

Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. From the meeting of its branches in Hancock (village), New York, Hancock, New York, the river flows for along the borders of N ...

further northeast to the "Quaker City" of

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, an anti-slavery stronghold. He continued to the safe house of abolitionist

David Ruggles

David Ruggles (March 15, 1810 – December 16, 1849) was an African-American abolitionist in New York who resisted slavery by his participation in a Committee of Vigilance and the Underground Railroad to help fugitive slaves reach free stat ...

in

New York City. His entire journey to freedom took less than 24 hours.

Douglass later wrote of his arrival in New York City:

Once Douglass had arrived, he sent for Murray to follow him north to New York. She brought the basics for them to set up a home. They were married on September 15, 1838, by a black

Presbyterian minister, just eleven days after Douglass had reached New York.

[ At first they adopted Johnson as their married name, to divert attention.]

Abolitionist and preacher

The couple settled in

The couple settled in New Bedford, Massachusetts

New Bedford (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ) is a city in Bristol County, Massachusetts, Bristol County, Massachusetts. It is located on the Acushnet River in what is known as the South Coast (Massachusetts), South Coast region. Up throug ...

(an abolitionist center, full of former enslaved people), in 1838, moving to Lynn, Massachusetts, in 1841.Douglas

Douglas may refer to:

People

* Douglas (given name)

* Douglas (surname)

Animals

*Douglas (parrot), macaw that starred as the parrot ''Rosalinda'' in Pippi Longstocking

*Douglas the camel, a camel in the Confederate Army in the American Civil W ...

".

Douglass thought of joining a white

Douglass thought of joining a white Methodist Church

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related Christian denomination, denominations of Protestantism, Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John W ...

, but was disappointed, from the beginning, upon finding that it was segregated. Later, he joined the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church

African or Africans may refer to:

* Anything from or pertaining to the continent of Africa:

** People who are native to Africa, descendants of natives of Africa, or individuals who trace their ancestry to indigenous inhabitants of Africa

*** Ethn ...

, an independent black denomination first established in New York City, which counted among its members Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth (; born Isabella Baumfree; November 26, 1883) was an American abolitionist of New York Dutch heritage and a women's rights activist. Truth was born into slavery in Swartekill, New York, but escaped with her infant daughter to f ...

and Harriet Tubman. He became a licensed preacher in 1839,steward

Steward may refer to:

Positions or roles

* Steward (office), a representative of a monarch

* Steward (Methodism), a leader in a congregation and/or district

* Steward, a person responsible for supplies of food to a college, club, or other ins ...

, Sunday-school

A Sunday school is an educational institution, usually (but not always) Christian in character. Other religions including Buddhism, Islam, and Judaism have also organised Sunday schools in their temples and mosques, particularly in the West.

Su ...

superintendent, and sexton. In 1840, Douglass delivered a speech in Elmira, New York

Elmira () is a city and the county seat of Chemung County, New York, United States. It is the principal city of the Elmira, New York, metropolitan statistical area, which encompasses Chemung County. The population was 26,523 at the 2020 cens ...

, then a station on the Underground Railroad, in which a black congregation would form years later, becoming the region's largest church by 1940.["Religious Facts You Might Not Know about Frederick Douglass"](_blank)

, ''Religion News'', June 19, 2013.

Douglass also joined several organizations in New Bedford and regularly attended abolitionist meetings. He subscribed to William Lloyd Garrison's weekly newspaper, ''The Liberator

Liberator or The Liberators or ''variation'', may refer to:

Literature

* ''Liberators'' (novel), a 2009 novel by James Wesley Rawles

* ''The Liberators'' (Suvorov book), a 1981 book by Victor Suvorov

* ''The Liberators'' (comic book), a Britis ...

''. He later said that "no face and form ever impressed me with such sentiments f the hatred of slavery

F, or f, is the sixth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''ef'' (pronounced ), and the plural is ''efs''.

Hist ...

as did those of William Lloyd Garrison." So deep was this influence that in his last autobiography, Douglass said "his paper took a place in my heart second only to The Bible."

Garrison was likewise impressed with Douglass and had written about his anti-colonization

Colonization, or colonisation, constitutes large-scale population movements wherein migrants maintain strong links with their, or their ancestors', former country – by such links, gain advantage over other inhabitants of the territory. When ...

stance in ''The Liberator'' as early as 1839. Douglass first heard Garrison speak in 1841, at a lecture that Garrison gave in Liberty Hall, New Bedford. At another meeting, Douglass was unexpectedly invited to speak. After telling his story, Douglass was encouraged to become an anti-slavery lecturer. A few days later, Douglass spoke at the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society's annual convention, in Nantucket

Nantucket () is an island about south from Cape Cod. Together with the small islands of Tuckernuck and Muskeget, it constitutes the Town and County of Nantucket, a combined county/town government that is part of the U.S. state of Massachuse ...

. Then 23 years old, Douglass conquered his nervousness and gave an eloquent speech about his life as a slave.

While living in Lynn, Douglass engaged in an early protest against segregated transportation. In September 1841, at Lynn Central Square station, Douglass and his friend

While living in Lynn, Douglass engaged in an early protest against segregated transportation. In September 1841, at Lynn Central Square station, Douglass and his friend James N. Buffum

James Needham Buffum (May 16, 1807 – June 12, 1887) was a Massachusetts politician who served as the 12th and 14th Mayor of Lynn, Massachusetts.

Early life

Buffum was born in North Berwick, Maine on May 16, 1807 to Samuel and Hannah (Varney) ...

were thrown off an Eastern Railroad

The Eastern Railroad was a railroad connecting Boston, Massachusetts to Portland, Maine. Throughout its history, it competed with the Boston and Maine Railroad for service between the two cities, until the Boston & Maine put an end to the compe ...

train because Douglass refused to sit in the segregated railroad coach.American Anti-Slavery Society

The American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS; 1833–1870) was an abolitionist society founded by William Lloyd Garrison and Arthur Tappan. Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave, had become a prominent abolitionist and was a key leader of this society ...

's "Hundred Conventions" project, a six-month tour at meeting halls throughout the eastern and midwestern United States. During this tour, slavery supporters frequently accosted Douglass. At a lecture in Pendleton, Indiana, an angry mob chased and beat Douglass before a local Quaker family, the Hardys, rescued him. His hand was broken in the attack; it healed improperly and bothered him for the rest of his life. A stone marker in Falls Park in the Pendleton Historic District commemorates this event.

In 1847, Douglass explained to Garrison, "I have no love for America, as such; I have no patriotism. I have no country. What country have I? The Institutions of this Country do not know me—do not recognize me as a man."

Autobiography

Douglass's best-known work is his first autobiography, '' Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave'', written during his time in Lynn, Massachusetts and published in 1845. At the time, some skeptics questioned whether a black man could have produced such an eloquent piece of literature. The book received generally positive reviews and became an immediate bestseller. Within three years, it had been reprinted nine times, with 11,000 copies circulating in the United States. It was also translated into French and Dutch and published in Europe.

Douglass published three autobiographies during his lifetime (and revised the third of these), each time expanding on the previous one. The 1845 ''Narrative'' was his biggest seller and probably allowed him to raise the funds to gain his legal freedom the following year, as discussed below. In 1855, Douglass published '' My Bondage and My Freedom''. In 1881, in his sixties, Douglass published '' Life and Times of Frederick Douglass'', which he revised in 1892.

Travels to Ireland and Great Britain

Douglass's friends and mentors feared that the publicity would draw the attention of his ex-owner, Hugh Auld, who might try to get his "property" back. They encouraged Douglass to tour Ireland, as many former slaves had done. Douglass set sail on the ''Cambria'' for Liverpool, England, on August 16, 1845. He traveled in Ireland as the Great Famine was beginning.

The feeling of freedom from American racial discrimination amazed Douglass:[Douglass, Frederick. ]885

Year 885 (Roman numerals, DCCCLXXXV) was a common year starting on Friday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place Europe

* Summer – Emperor Charles the Fat summons a meeting of officials at ...

2003. '' My Bondage and My Freedom: Part I – Life as a Slave, Part II – Life as a Freeman'', introduction by James McCune Smith, edited by J. Stauffer. New York: Random House. . p

371

Eleven days and a half gone, and I have crossed three thousand miles of the perilous deep. Instead of a democratic government, I am under a monarchical government. Instead of the bright, blue sky of America, I am covered with the soft, grey fog of the Emerald Isle reland I breathe, and lo! the chattel lave

''Lave'' was an ironclad floating battery of the French Navy during the 19th century. She was part of the of floating batteries.

In the 1850s, the British and French navies deployed iron-armoured floating batteries as a supplement to the wooden ...

becomes a man. I gaze around in vain for one who will question my equal humanity, claim me as his slave, or offer me an insult. I employ a cab—I am seated beside white people—I reach the hotel—I enter the same door—I am shown into the same parlor—I dine at the same table—and no one is offended.... I find myself regarded and treated at every turn with the kindness and deference paid to white people. When I go to church, I am met by no upturned nose and scornful lip to tell me, ''We don't allow niggers in here!''

Still, Douglass was astounded by the extreme levels of poverty he encountered, much of it reminding him of his experiences in slavery. In a letter to William Lloyd Garrison, Douglass wrote "I see much here to remind me of my former condition, and I confess I should be ashamed to lift up my voice against American slavery, but that I know the cause of humanity is one the world over. He who really and truly feels for the American slave, cannot steel his heart to the woes of others; and he who thinks himself an abolitionist, yet cannot enter into the wrongs of others, has yet to find a true foundation for his anti-slavery faith."

He also met and befriended the Irish nationalist and strident abolitionist Daniel O'Connell, who was to be a great inspiration.

Douglass spent two years in Ireland and Great Britain, lecturing in churches and chapels. His draw was such that some facilities were "crowded to suffocation". One example was his hugely popular ''London Reception Speech'', which Douglass delivered in May 1846 at Alexander Fletcher Alexander Fletcher or Alex Fletcher may refer to:

* Alexander Fletcher (British politician) (1929–1989), known as Sir Alex Fletcher, Conservative Member of Parliament (MP) in the UK

* Alexander Fletcher (colonial politician), Canadian politician ...

's Finsbury Chapel. Douglass remarked that in England he was treated not "as a color, but as a man".Cork

Cork or CORK may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Cork (plug), a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

***Wine cork

Places Ireland

* Cork (city)

** Metropolitan Cork, also known as G ...

and Waterford, Ireland, and London to celebrate Douglass's visit: the first is on the Imperial Hotel in Cork and was unveiled on August 31, 2012; the second is on the façade of Waterford City Hall, unveiled on October 7, 2013. It commemorates his speech there on October 9, 1845. The third plaque adorns Nell Gwynn House, South Kensington in London, at the site of an earlier house where Douglass stayed with the British abolitionist George Thompson.)

Douglass spent time in Scotland and was appointed "Scotland's Antislavery agent." He made anti-slavery speeches and wrote letters back to the USA. He considered the city of Edinburgh to be elegant, grand and very welcoming. Maps of the places in the city that were important to his stay are held by the National Library of Scotland. A plaque and a mural on Gilmore Place in Edinburgh mark his stay there in 1846.

"A variety of collaborative projects are currently n 2021

N, or n, is the fourteenth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''en'' (pronounced ), plural ''ens''.

History

...

underway to commemorate Frederick Douglass’s journey and visit to Ireland in the 19th century."

Return to the United States; the abolitionist movement

After returning to the U.S. in 1847, using £500 () given to him by English supporters,

After returning to the U.S. in 1847, using £500 () given to him by English supporters,The Unconstitutionality of Slavery

''The Unconstitutionality of Slavery'' (1845) was a book by American abolitionist Lysander Spooner advocating the view that the United States Constitution prohibited slavery. This view was advocated in contrast to that of William Lloyd Garrison ...

'' (1846), which examined the United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven ar ...

as an antislavery document. Douglass's change of opinion about the Constitution and his splitting from Garrison around 1847 became one of the abolitionist movement's most notable divisions. Douglass angered Garrison by saying that the Constitution could and should be used as an instrument in the fight against slavery.

Letter to his former owner

In September 1848, on the tenth anniversary of his escape, Douglass published an open letter addressed to his former master, Thomas Auld, berating him for his conduct, and inquiring after members of his family still held by Auld.Oh! sir, a slaveholder never appears to me so completely an agent of hell, as when I think of and look upon my dear children. It is then that my feelings rise above my control. ... The grim horrors of slavery rise in all their ghastly terror before me, the wails of millions pierce my heart, and chill my blood. I remember the chain, the gag, the bloody whip, the deathlike gloom overshadowing the broken spirit of the fettered bondman, the appalling liability of his being torn away from wife and children, and sold like a beast in the market.

In a graphic passage, Douglass asked Auld how he would feel if Douglass had come to take away his daughter Amanda into slavery, treating her the way he and members of his family had been treated by Auld.

Women's rights

In 1848, Douglass was the only black person to attend the Seneca Falls Convention, the first women's rights convention, in upstate New York. Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (November 12, 1815 – October 26, 1902) was an American writer and activist who was a leader of the women's rights movement in the U.S. during the mid- to late-19th century. She was the main force behind the 1848 Seneca ...

asked the assembly to pass a resolution asking for women's suffrage. Many of those present opposed the idea, including influential Quakers James

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguat ...

and Lucretia Mott.[ Douglass stood and spoke eloquently in favor of women's suffrage; he said that he could not accept the right to vote as a black man if women could also not claim that right. He suggested that the world would be a better place if women were involved in the political sphere.

After Douglass's powerful words, the attendees passed the resolution.][

In the wake of the Seneca Falls Convention, Douglass used an editorial in ''The North Star'' to press the case for women's rights. He recalled the "marked ability and dignity" of the proceedings, and briefly conveyed several arguments of the convention and feminist thought at the time.

On the first count, Douglass acknowledged the "decorum" of the participants in the face of disagreement. In the remainder, he discussed the primary document that emerged from the conference, a Declaration of Sentiments, and the "infant" feminist cause. Strikingly, he expressed the belief that " discussion of the rights of animals would be regarded with far more complacency...than would be a discussion of the rights of women," and Douglass noted the link between abolitionism and feminism, the overlap between the communities.

His opinion as the editor of a prominent newspaper carried weight, and he stated the position of the ''North Star'' explicitly: "We hold woman to be justly entitled to all we claim for man." This letter, written a week after the convention, reaffirmed the first part of the paper's slogan, "right is of no sex."

After the Civil War, when the 15th Amendment giving black men the right to vote was being debated, Douglass split with the Stanton-led faction of the women's rights movement. Douglass supported the amendment, which would grant suffrage to black men. Stanton opposed the 15th Amendment because it limited the expansion of suffrage to black men; she predicted its passage would delay for decades the cause for women's right to vote. Stanton argued that American women and black men should band together to fight for universal suffrage, and opposed any bill that split the issues.][Foner, p. 600.]

Douglass thought such a strategy was too risky, that there was barely enough support for black men's suffrage. He feared that linking the cause of women's suffrage to that of black men would result in failure for both. Douglass argued that white women, already empowered by their social connections to fathers, husbands, and brothers, at least vicariously had the vote. Black women, he believed, would have the same degree of empowerment as white women once black men had the vote.

Ideological refinement

Meanwhile, in 1851, Douglass merged the ''North Star'' with

Meanwhile, in 1851, Douglass merged the ''North Star'' with Gerrit Smith

Gerrit Smith (March 6, 1797 – December 28, 1874), also spelled Gerritt Smith, was a leading American social reformer, abolitionist, businessman, public intellectual, and philanthropist. Married to Ann Carroll Fitzhugh, Smith was a candidat ...

's ''Liberty Party Paper'' to form ''Frederick Douglass' Paper'', which was published until 1860.

On July 5, 1852, Douglass delivered an address in Corinthian Hall at a meeting organized by the Rochester Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society. This speech eventually became known as "What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?

"What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?" was a speech delivered by Frederick Douglass on July 5, 1852, at Corinthian Hall in Rochester, New York, at a meeting organized by the Rochester Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society. In the address, Douglass st ...

"; one biographer called it "perhaps the greatest antislavery oration ever given." In 1853, he was a prominent attendee of the radical abolitionist National African American Convention in Rochester. Douglass was one of five people whose names were attached to the address of the convention to the people of the United States published under the title, ''The Claims of Our Common Cause''. The other four were Amos Noë Freeman

Amos Noë Freeman (1809—1893) was an African-American abolitionist, Presbyterian minister, and educator. He was the first full-time minister of Abyssinian Congregational Church in Portland, Maine, where he led a station on the Underground ...

, James Monroe Whitfield

James Monroe Whitfield (c. April 10, 1822 – April 23, 1871) was an African-American poet, abolitionist, and political activist. He was a notable writer and activist in abolitionism and African emigration during the antebellum era. He published th ...

, Henry O. Wagoner

Henry O. Wagoner (February 27, 1816 – January 27, 1901) was an abolitionist and civil rights activist in Chicago and Denver. In the 1830s, as a free black man in Maryland, he worked on a farm and worked to free slaves with a loose group of indiv ...

, and George Boyer Vashon

George Boyer Vashon (July 25, 1824 – October 5, 1878) was an African American scholar, poet, lawyer, and abolitionist.

Biography

George Boyer Vashon was born in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, the third child and only son of an abolitionist, John Be ...

.

Like many abolitionists, Douglass believed that education would be crucial for African Americans to improve their lives; he was an early advocate for school desegregation

School integration in the United States is the process (also known as desegregation) of ending race-based segregation within American public and private schools. Racial segregation in schools existed throughout most of American history and rema ...

. In the 1850s, Douglass observed that New York's facilities and instruction for African-American children were vastly inferior to those for European Americans. Douglass called for court action to open all schools to all children. He said that full inclusion within the educational system was a more pressing need for African Americans than political issues such as suffrage.

John Brown

On March 12, 1859, Douglass met with radical abolitionists John Brown John Brown most often refers to:

*John Brown (abolitionist) (1800–1859), American who led an anti-slavery raid in Harpers Ferry, Virginia in 1859

John Brown or Johnny Brown may also refer to:

Academia

* John Brown (educator) (1763–1842), Ir ...

, George DeBaptiste, and others at William Webb's house in Detroit to discuss emancipation. Douglass met Brown again when Brown visited his home two months before leading the raid on Harpers Ferry. Brown penned his Provisional Constitution during his two-week stay with Douglass. Also staying with Douglass for over a year was Shields Green

Shields Green (1836? – December 16, 1859), who also referred to himself as "'Emperor"', was, according to Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave from Charleston, South Carolina, and a leader in John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, in October 1859. ...

, a fugitive slave whom Douglass was helping, as he often did.

Shortly before the raid, Douglass, taking Green with him, travelled from Rochester, via New York City, to Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, Brown's communications headquarters. He was recognized there by black people, who asked him for a lecture. Douglass agreed, although he said his only topic was slavery. Green joined him on the stage; Brown, incognito, sat in the audience. A white reporter, referring to "Nigger Democracy", called it a "flaming address" by "the notorious Negro Orator".

There, in an abandoned stone quarry for secrecy, Douglass and Green met with Brown and John Henri Kagi, to discuss the raid. After discussions lasting, as Douglass put it, "a day and a night", he disappointed Brown by declining to join him, considering the mission suicidal. To Douglass's surprise, Green went with Brown instead of returning to Rochester with Douglass. Anne Brown said that Green told her that Douglass promised to pay him on his return, but David Blight

David William Blight (born 1949) is the Sterling Professor of History, of African American Studies, and of American Studies and Director of the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition at Yale University. Previous ...

called this "much more ex post facto bitterness than reality".

Almost all that is known about this incident comes from Douglass. It is clear that it was of immense importance to him, both as a turning point in his life—not accompanying John Brown—and its importance in his public image. The meeting was not revealed by Douglass for 20 years. He first disclosed it in his speech on John Brown at Storer College in 1881, trying unsuccessfully to raise money to support a John Brown professorship at Storer, to be held by a black man. He again referred to it stunningly in his last ''Autobiography''.

After the raid, which took place between October 16 and 18, 1859, Douglass was accused both of supporting Brown and of not supporting him enough. He was nearly arrested on a Virginia warrant, and fled for a brief time to Canada before proceeding onward to England on a previously planned lecture tour, arriving near the end of November. During his lecture tour of Great Britain, on March 26, 1860, Douglass delivered a speech before the Scottish Anti-Slavery Society in Glasgow, " The Constitution of the United States: is it pro-slavery or anti-slavery?", outlining his views on the American Constitution. That month, on the 13th, Douglass's youngest daughter Annie died in Rochester, New York, just days shy of her 11th birthday. Douglass sailed back from England the following month, traveling through Canada to avoid detection.

Years later, in 1881, Douglass shared a stage at Storer College in Harpers Ferry with Andrew Hunter Andrew Hunter or Andy Hunter may refer to:

Sports

*Andrew Hunter (British swimmer) (born 1986), British swimmer who was a medalist in the Commonwealth Games

* Andrew Hunter (Irish swimmer) (born 1952), Irish swimmer

*Andy Hunter (footballer, born 1 ...

, the prosecutor who secured Brown's conviction and execution. Hunter congratulated Douglass.

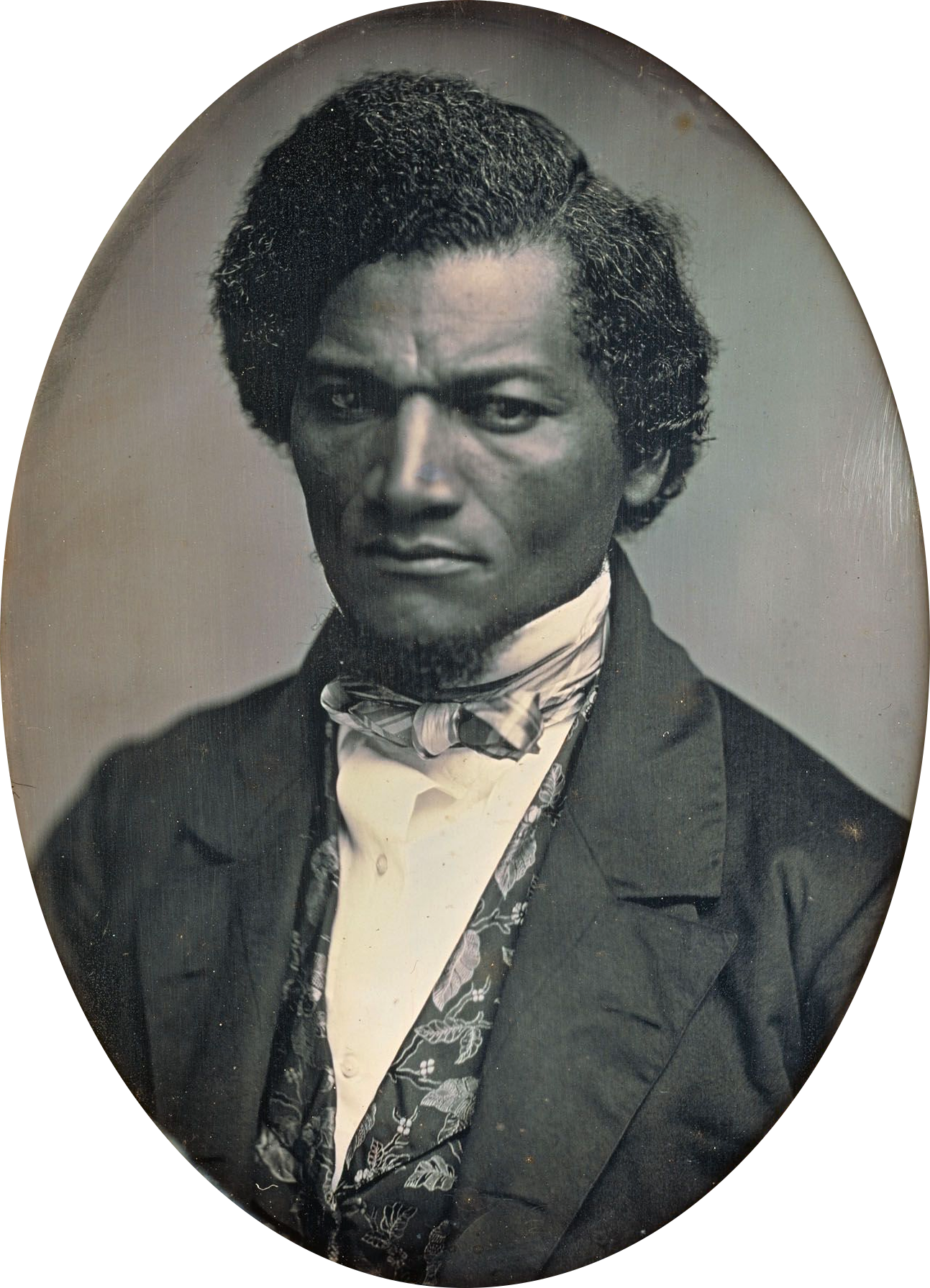

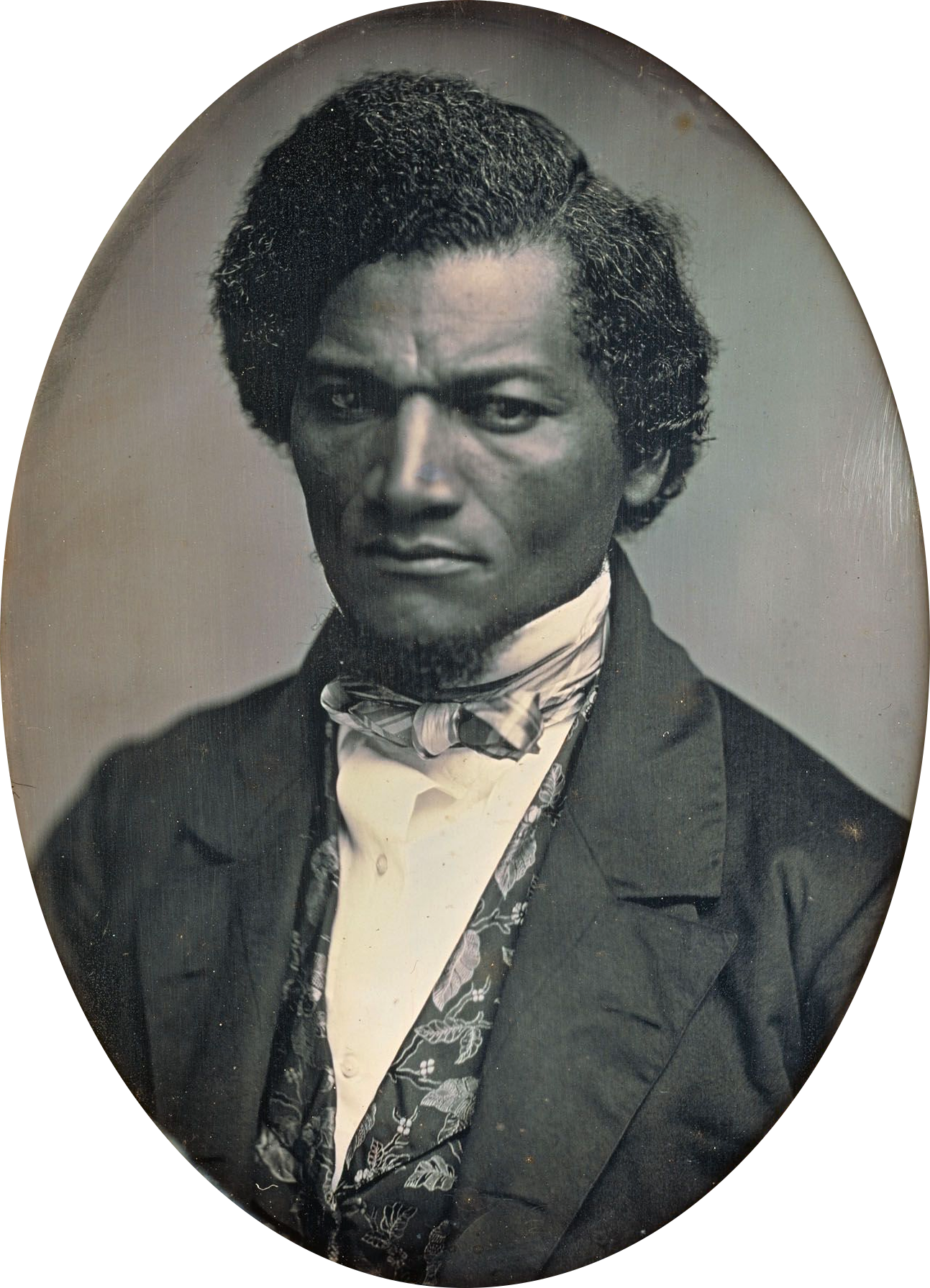

Photography

Douglass considered photography very important in ending slavery and racism, and believed that the camera would not lie, even in the hands of a racist white person, as photographs were an excellent counter to many racist caricatures, particularly in blackface

Blackface is a form of theatrical makeup used predominantly by non-Black people to portray a caricature of a Black person.

In the United States, the practice became common during the 19th century and contributed to the spread of racial stereo ...

minstrelsy. He was the most photographed American of the 19th century, consciously using photography to advance his political views. He never smiled, specifically so as not to play into the racist caricature of a happy enslaved person. He tended to look directly into the camera and confront the viewer with a stern look.

Religious views

As a child, Douglass was exposed to a number of religious sermons, and in his youth, he sometimes heard Sophia Auld reading the Bible. In time, he became interested in literacy; he began reading and copying bible verses, and he eventually converted to Christianity

Conversion to Christianity is the religious conversion of a previously non-Christian person to Christianity. Different Christian denominations may perform various different kinds of rituals or ceremonies initiation into their community of belie ...

.I was not more than thirteen years old, when in my loneliness and destitution I longed for some one to whom I could go, as to a father and protector. The preaching of a white Methodist minister, named Hanson, was the means of causing me to feel that in God I had such a friend. He thought that all men, great and small, bond and free, were sinners in the sight of God: that they were by nature rebels against His government; and that they must repent of their sins, and be reconciled to God through Christ. I cannot say that I had a very distinct notion of what was required of me, but one thing I did know well: I was wretched and had no means of making myself otherwise.

I consulted a good old colored man named Charles Lawson, and in tones of holy affection he told me to pray, and to "cast all my care upon God." This I sought to do; and though for weeks I was a poor, broken-hearted mourner, traveling through doubts and fears, I finally found my burden lightened, and my heart relieved. I loved all mankind, slaveholders not excepted, though I abhorred slavery more than ever. I saw the world in a new light, and my great concern was to have everybody converted. My desire to learn increased, and especially, did I want a thorough acquaintance with the contents of the Bible.

Douglass was mentored by Rev. Charles Lawson, and, early in his activism, he often included biblical allusions and religious metaphors in his speeches. Although a believer, he strongly criticized religious hypocrisy,What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?

"What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?" was a speech delivered by Frederick Douglass on July 5, 1852, at Corinthian Hall in Rochester, New York, at a meeting organized by the Rochester Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society. In the address, Douglass st ...

'', an oration Douglass gave in the Corinthian Hall of Rochester, he sharply criticized the attitude of religious people who kept silent about slavery, and he charged that ministers committed a "blasphemy

Blasphemy is a speech crime and religious crime usually defined as an utterance that shows contempt, disrespects or insults a deity, an object considered sacred or something considered inviolable. Some religions regard blasphemy as a religiou ...

" when they taught it as sanctioned by religion. He considered that a law passed to support slavery was "one of the grossest infringements of Christian Liberty" and said that pro-slavery clergymen within the American Church "stripped the love of God of its beauty, and leave the throne of religion a huge, horrible, repulsive form", and "an abomination in the sight of God".Ichabod Spencer Ichabod Smith Spencer (February 23, 1798 – November 23, 1854) was a popular 19th-century American Presbyterian preacher and author.J. M. Sherwood, "Sketch of Life and Character", in ''Sermons of Ichabod S. Spencer - Volume 1'' (1864).

Spencer was ...

, and Orville Dewey

Orville Dewey (March 28, 1794 – March 21, 1882) was an American Unitarian minister.

Early life

Dewey was born in Sheffield, Massachusetts. His ancestors were among the first settlers of Sheffield, where he spent his early life, alternately ...

, he said that they taught, against the Scriptures, that "we ought to obey man's law before the law of God". He further asserted, "in speaking of the American church, however, let it be distinctly understood that I mean the great mass of the religious organizations of our land. There are exceptions, and I thank God that there are. Noble men may be found, scattered all over these Northern States ... Henry Ward Beecher of Brooklyn, Samuel J. May

Samuel Joseph May (September 12, 1797 – July 1, 1871) was an American reformer during the nineteenth century who championed education, women's rights, and abolition of slavery. May argued on behalf of all working people that the rights of h ...

of Syracuse, and my esteemed friend obert R. Raymonde Obert may refer to the following people:

;Given name

*Obert Bika (born 1993), Papua New Guinean football midfielder

*Obert Logan (1941–2003), American football safety

*Obert Mpofu, Zimbabwean politician

*Obert Nyampipira (born 1966), Zimbabwean ...

.non-denominational

A non-denominational person or organization is one that does not follow (or is not restricted to) any particular or specific religious denomination.

Overview

The term has been used in the context of various faiths including Jainism, Baháʼí Fait ...

liberation theology, Douglass was a deeply spiritual man, as his home continues to show. The fireplace mantle features busts of two of his favorite philosophers, David Friedrich Strauss, author of ''The Life of Jesus'', and Ludwig Feuerbach, author of '' The Essence of Christianity''. In addition to several Bibles and books about various religions in the library, images of angels and Jesus are displayed, as well as interior and exterior photographs of Washington's Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church

Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church ("Metropolitan AME Church") is a historic church located at 1518 M Street, N.W., in downtown Washington, D.C. It affiliates with the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

History

The congregati ...

.

Civil War years

Before the Civil War

By the time of the Civil War, Douglass was one of the most famous black men in the country, known for his orations on the condition of the black race and on other issues such as women's rights. His eloquence gathered crowds at every location. His reception by leaders in England and Ireland added to his stature.

He had been seriously proposed for the congressional seat of his friend and supporter Gerrit Smith

Gerrit Smith (March 6, 1797 – December 28, 1874), also spelled Gerritt Smith, was a leading American social reformer, abolitionist, businessman, public intellectual, and philanthropist. Married to Ann Carroll Fitzhugh, Smith was a candidat ...

, who declined to run again after his term ended in 1854.[ Smith recommended to him that he not run, because there were "strenuous objections" from members of Congress. The possibility "afflicted some with convulsions, others with panic, more with an astonishing flow of exceedingly select and nervous language", "giving vent to all sorts of linguistic enormities." If the House agreed to seat him, which was unlikely, all the Southern members would walk out, so the country would finally be split.]

Fight for emancipation and suffrage

Douglass and the abolitionists argued that because the aim of the Civil War was to end slavery, African Americans should be allowed to engage in the fight for their freedom. Douglass publicized this view in his newspapers and several speeches. After Lincoln had finally allowed black soldiers to serve in the Union army, Douglass helped the recruitment efforts, publishing his famous broadside ''Men of Color to Arms!'' on March 21, 1863. His eldest son, Charles Douglass, joined the

Douglass and the abolitionists argued that because the aim of the Civil War was to end slavery, African Americans should be allowed to engage in the fight for their freedom. Douglass publicized this view in his newspapers and several speeches. After Lincoln had finally allowed black soldiers to serve in the Union army, Douglass helped the recruitment efforts, publishing his famous broadside ''Men of Color to Arms!'' on March 21, 1863. His eldest son, Charles Douglass, joined the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment

The 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment that saw extensive service in the Union Army during the American Civil War. The unit was the second African-American regiment, following the 1st Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry ...

, but was ill for much of his service.Emancipation Proclamation

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the Civil War. The Proclamation changed the legal sta ...

, which took effect on January 1, 1863, declared the freedom of all slaves in Confederate-held territory. (Slaves in Union-held areas were not covered because the proclamation was permissible under the Constitution only as a war measure; they were freed with the adoption of the 13th Amendment on December 6, 1865.) Douglass described the spirit of those awaiting the proclamation: "We were waiting and listening as for a bolt from the sky ... we were watching ... by the dim light of the stars for the dawn of a new day ... we were longing for the answer to the agonizing prayers of centuries."

During the U.S. Presidential Election of 1864, Douglass supported John C. Frémont

John Charles Frémont or Fremont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was an American explorer, military officer, and politician. He was a U.S. Senator from California and was the first Republican nominee for president of the United States in 1856 ...

, who was the candidate of the abolitionist Radical Democracy Party. Douglass was disappointed that President Lincoln did not publicly endorse suffrage for black freedmen. Douglass believed that since African-American men were fighting for the Union in the American Civil War, they deserved the right to vote.

After Lincoln's death

The postwar ratification of the 13th Amendment, on December 6, 1865, outlawed slavery, "except as a punishment for crime." The 14th Amendment provided for birthright citizenship and prohibited the states from abridging the privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States or denying any "person" due process of law or equal protection of the laws. The 15th Amendment protected all citizens from being discriminated against in voting because of race.Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

on the subject of black suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in representative democracy, public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally i ...

.

On April 14, 1876, Douglass delivered the keynote speech at the unveiling of the Emancipation Memorial

The Emancipation Memorial, also known as the Freedman's Memorial or the Emancipation Group is a monument in Lincoln Park in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Washington, D.C. It was sometimes referred to as the "Lincoln Memorial" before the more ...

in Washington's Lincoln Park. He spoke frankly about Lincoln, noting what he perceived as both positive and negative attributes of the late President. Calling Lincoln "the white man's President," Douglass criticized Lincoln's tardiness in joining the cause of emancipation, noting that Lincoln initially opposed the expansion of slavery but did not support its elimination. But Douglass also asked, "Can any colored man, or any white man friendly to the freedom of all men, ever forget the night which followed the first day of January 1863, when the world was to see if Abraham Lincoln would prove to be as good as his word?" He also said: "Though Mr. Lincoln shared the prejudices of his white fellow-countrymen against the Negro, it is hardly necessary to say that in his heart of hearts he loathed and hated slavery...." Most famously, he added: "Viewed from the genuine abolition ground, Mr. Lincoln seemed tardy, cold, dull, and indifferent; but measuring him by the sentiment of his country, a sentiment he was bound as a statesman to consult, he was swift, zealous, radical, and determined."

The crowd, roused by his speech, gave Douglass a standing ovation. Lincoln's widow Mary Lincoln supposedly gave Lincoln's favorite walking-stick

A walking stick or walking cane is a device used primarily to aid walking, provide postural stability or support, or assist in maintaining a good posture. Some designs also serve as a fashion accessory, or are used for self-defense.

Walking sti ...

to Douglass in appreciation. That walking-stick still rests in his final residence, "Cedar Hill" in Washington, D.C., now preserved as the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site.

After delivering the speech, Frederick Douglass immediately wrote to the National Republican newspaper in Washington (which published five days later, April 19), criticizing the statue's design and suggesting the park could be improved by more dignified monuments of free black people. "The negro here, though rising, is still on his knees and nude," Douglass wrote. "What I want to see before I die is a monument representing the negro, not couchant on his knees like a four-footed animal, but erect on his feet like a man."

Reconstruction era

After the Civil War, Douglass continued to work for equality for African Americans and women. Due to his prominence and activism during the war, Douglass received several political appointments. He served as president of the Reconstruction-era Freedman's Savings Bank.

Meanwhile, white insurgents had quickly arisen in the South after the war, organizing first as secret vigilante groups, including the

After the Civil War, Douglass continued to work for equality for African Americans and women. Due to his prominence and activism during the war, Douglass received several political appointments. He served as president of the Reconstruction-era Freedman's Savings Bank.

Meanwhile, white insurgents had quickly arisen in the South after the war, organizing first as secret vigilante groups, including the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

. Armed insurgency took different forms. Powerful paramilitary groups included the White League and the Red Shirts, both active during the 1870s in the Deep South. They operated as "the military arm of the Democratic Party", turning out Republican officeholders and disrupting elections. Starting 10 years after the war, Democrats regained political power in every state of the former Confederacy and began to reassert white supremacy. They enforced this by a combination of violence, late 19th-century laws imposing segregation and a concerted effort to disfranchise

Disfranchisement, also called disenfranchisement, or voter disqualification is the restriction of suffrage (the right to vote) of a person or group of people, or a practice that has the effect of preventing a person exercising the right to vote. D ...

African Americans. New labor and criminal laws also limited their freedom.

To combat these efforts, Douglass supported the presidential campaign of Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

in 1868

Events

January–March

* January 2 – British Expedition to Abyssinia: Robert Napier leads an expedition to free captive British officials and missionaries.

* January 3 – The 15-year-old Mutsuhito, Emperor Meiji of Jap ...

. In 1870, Douglass started his last newspaper, the '' New National Era'', attempting to hold his country to its commitment to equality. After the midterm elections, Grant signed the Civil Rights Act of 1871 (also known as the Klan Act), and the second and third

After the midterm elections, Grant signed the Civil Rights Act of 1871 (also known as the Klan Act), and the second and third Enforcement Acts

The Enforcement Acts were three bills that were passed by the United States Congress between 1870 and 1871. They were criminal codes that protected African Americans’ right to vote, to hold office, to serve on juries, and receive equal protect ...

. Grant used their provisions vigorously, suspending '' habeas corpus'' in South Carolina and sending troops there and into other states. Under his leadership over 5,000 arrests were made. Grant's vigor in disrupting the Klan made him unpopular among many whites but earned praise from Douglass. A Douglass associate wrote that African Americans "will ever cherish a grateful remembrance of rant'sname, fame and great services."

In 1872, Douglass became the first African American nominated for Vice President of the United States, as Victoria Woodhull's running mate on the Equal Rights Party ticket. He was nominated without his knowledge. Douglass neither campaigned for the ticket nor acknowledged that he had been nominated.

Family life

Douglass and Anna Murray had five children: Rosetta Douglass

Rosetta Douglass-Sprague (June 24, 1839 – November 25, 1906) was an American teacher and activist. She was a founding member of the National Association for Colored Women. Her mother was Anna Murray Douglass and her father was Frederick Dougla ...

, Lewis Henry Douglass

Lewis Henry Douglass (October 9, 1840 – September 19, 1908) was an American military Sergeant Major, the oldest son of Frederick Douglass and his first wife Anna Murray Douglass.

Biography

Lewis Henry Douglass was born on 9 October 1840 in ...

, Frederick Douglass Jr.

Frederick Douglass Jr. (March 3, 1842 – July 26, 1892) was the second son of Frederick Douglass and his wife Anna Murray Douglass. Born in New Bedford, Massachusetts, he was an Abolitionism, abolitionist, essayist, newspaper editor, and an offi ...

, Charles Remond Douglass, and Annie Douglass (died at the age of ten). Charles and Rosetta helped produce his newspapers.

Anna Douglass remained a loyal supporter of her husband's public work. His relationships with Julia Griffiths

Julia Griffiths (21 May 1811 – 1895) was a British abolitionist who worked with the American former slave Frederick Douglass. The two met in London, England, during Douglass's tour of the British Isles in 1845–47. In 1849, Griffiths joined Do ...

and Ottilie Assing, two women with whom he was professionally involved, caused recurring speculation and scandals. Assing was a journalist recently immigrated from Germany, who first visited Douglass in 1856 seeking permission to translate ''My Bondage and My Freedom'' into German. Until 1872, she often stayed at his house "for several months at a time" as his "intellectual and emotional companion."Honeoye, New York

Honeoye ( ) is a hamlet in the Town of Richmond, in Ontario County, New York, United States. The population was 579 at the 2010 census, which lists the community as a census-designated place (CDP).

It is located 33 miles (53 kilometers) sout ...

. Pitts was the daughter of Gideon Pitts Jr., an abolitionist colleague and friend of Douglass's. A graduate of Mount Holyoke College

Mount Holyoke College is a private liberal arts women's college in South Hadley, Massachusetts. It is the oldest member of the historic Seven Sisters colleges, a group of elite historically women's colleges in the Northeastern United States.

...

(then called Mount Holyoke Female Seminary), Pitts worked on a radical feminist publication named ''Alpha'' while living in Washington, D.C. She later worked as Douglass's secretary.

Assing, who had depression and was diagnosed with incurable breast cancer, committed suicide in France in 1884 after hearing of the marriage. Upon her death, Assing bequeathed Douglass a $13,000 trust fund, a "large album", and his choice of books from her library.

The marriage of Douglass and Pitts provoked a storm of controversy, since Pitts was both white and nearly 20 years younger. Many in her family stopped speaking to her; his children considered the marriage a repudiation of their mother. But feminist Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (November 12, 1815 – October 26, 1902) was an American writer and activist who was a leader of the women's rights movement in the U.S. during the mid- to late-19th century. She was the main force behind the 1848 Seneca ...

congratulated the couple. Douglass responded to the criticisms by saying that his first marriage had been to someone the color of his mother, and his second to someone the color of his father.

Final years in Washington, D.C.

The Freedman's Savings Bank went bankrupt on June 29, 1874, just a few months after Douglass became its president in late March. During that same economic crisis, his final newspaper, ''The New National Era'', failed in September. When Republican Rutherford B. Hayes was elected president, he named Douglass as United States Marshal for the District of Columbia, the first person of color to be so named. The Senate voted to confirm him on March 17, 1877. Douglass accepted the appointment, which helped assure his family's financial security. In 1877, Douglass visited his former enslaver Thomas Auld on his deathbed, and the two men reconciled. Douglass had met Auld's daughter, Amanda Auld Sears, some years prior. She had requested the meeting and had subsequently attended and cheered one of Douglass's speeches. Her father complimented her for reaching out to Douglass. The visit also appears to have brought closure to Douglass, although some criticized his effort.

In 1877, Douglass visited his former enslaver Thomas Auld on his deathbed, and the two men reconciled. Douglass had met Auld's daughter, Amanda Auld Sears, some years prior. She had requested the meeting and had subsequently attended and cheered one of Douglass's speeches. Her father complimented her for reaching out to Douglass. The visit also appears to have brought closure to Douglass, although some criticized his effort.Ida B. Wells

Ida B. Wells (full name: Ida Bell Wells-Barnett) (July 16, 1862 – March 25, 1931) was an American investigative journalist, educator, and early leader in the civil rights movement. She was one of the founders of the National Association for ...

. He remarried in 1884, as mentioned above.

Douglass also continued his speaking engagements and travel, both in the United States and abroad. With new wife Helen, Douglass traveled to England, Ireland, France, Italy, Egypt, and Greece from 1886 to 1887. He became known for advocating Irish Home Rule

The Irish Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for Devolution, self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1 ...

and supported Charles Stewart Parnell in Ireland.

At the 1888 Republican National Convention

The 1888 Republican National Convention was a presidential nominating convention held at the Auditorium Building in Chicago, Illinois, on June 19–25, 1888. It resulted in the nomination of former Senator Benjamin Harrison of Indiana for preside ...

, Douglass became the first African American to receive a vote for President of the United States in a major party's roll call vote. That year, Douglass spoke at Claflin College

Claflin University is a private historically black university in Orangeburg, South Carolina. Founded in 1869 after the American Civil War by northern missionaries for the education of freedmen and their children, it offers bachelor's and master ...

, a historically black college in Orangeburg, South Carolina, and the state's oldest such institution.

Many African Americans, called Exodusters, escaped the Klan and racially discriminatory laws in the South by moving to Kansas, where some formed all-black towns to have a greater level of freedom and autonomy. Douglass favored neither this nor the Back-to-Africa movement. He thought the latter resembled the American Colonization Society, which he had opposed in his youth. In 1892, at an Indianapolis conference convened by Bishop Henry McNeal Turner

Henry McNeal Turner (February 1, 1834 – May 8, 1915) was an American minister, politician, and the 12th elected and consecrated bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME). After the American Civil War, he worked to establish new A.M ...

, Douglass spoke out against the separatist movements, urging blacks to stick it out.Chargé d'affaires

A ''chargé d'affaires'' (), plural ''chargés d'affaires'', often shortened to ''chargé'' (French) and sometimes in colloquial English to ''charge-D'', is a diplomat who serves as an embassy's chief of mission in the absence of the ambassador ...

for Santo Domingo in 1889,Douglass Place

Douglass Place is a group of historic rowhouses located at Baltimore, Maryland, United States. Built in 1892, it represents typical "alley houses" of the period in Baltimore, two narrow bays wide, two stories high over a cellar, with shed roofs ...

, in the Fells Point area of Baltimore. The complex still exists, and in 2003 was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Death

On February 20, 1895, Douglass attended a meeting of the National Council of Women in Washington, D.C. During that meeting, he was brought to the platform and received a standing ovation. Shortly after he returned home, Douglass died of a massive heart attack.

On February 20, 1895, Douglass attended a meeting of the National Council of Women in Washington, D.C. During that meeting, he was brought to the platform and received a standing ovation. Shortly after he returned home, Douglass died of a massive heart attack.Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church

Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church ("Metropolitan AME Church") is a historic church located at 1518 M Street, N.W., in downtown Washington, D.C. It affiliates with the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

History

The congregati ...

. Although Douglass had attended several churches in the nation's capital, he had a pew here and had donated two standing candelabras when this church had moved to a new building in 1886. He also gave many lectures there, including his last major speech, "The Lesson of the Hour."Jeremiah Rankin

Jeremiah Eames Rankin (January 2, 1828 – November 28, 1904) was an abolitionist, champion of the temperance movement, minister of Washington D.C.'s First Congregational Church, and correspondent with Frederick Douglass. In 1890 he was appoin ...

, President of Howard University, delivered "a masterly address". A letter from Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (November 12, 1815 – October 26, 1902) was an American writer and activist who was a leader of the women's rights movement in the U.S. during the mid- to late-19th century. She was the main force behind the 1848 Seneca ...

was read. The Secretary of the Haitian Legation "expressed the condolence of his country in melodious French."

Douglass's coffin was transported to Rochester, New York, where he had lived for 25 years, longer than anywhere else in his life. His body was received in state at City Hall, flags were flown at half mast, and schools adjourned. He was buried next to Anna in the Douglass family plot of Mount Hope Cemetery, Rochester's premier memorial park.[ Helen was also buried there, in 1903. His grave is, with that of Susan B. Anthony, the most visited in the cemetery.][

]

Works

Writings

* 1845. '' Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself'' (first autobiography).

* 1853. " The Heroic Slave." pp. 174–239 in ''Autographs for Freedom'', edited by Julia Griffiths

Julia Griffiths (21 May 1811 – 1895) was a British abolitionist who worked with the American former slave Frederick Douglass. The two met in London, England, during Douglass's tour of the British Isles in 1845–47. In 1849, Griffiths joined Do ...

. Boston: Jewett and Company.

* 1855. '' My Bondage and My Freedom'' (second autobiography).

* 1881 (revised 1892). '' Life and Times of Frederick Douglass'' (third and final autobiography).

* 1847–1851. '' The North Star'', an abolitionist newspaper founded and edited by Douglass. He merged the paper with another, creating the ''Frederick Douglass' Paper''.

* 1886. '' Three Addresses on the Relations Subsisting between the White and Colored People of the United States'', at Gutenberg.org

* 2012.

In the Words of Frederick Douglass: Quotations from Liberty's Champion

', edited by John R. McKivigan and Heather L. Kaufman. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. .

*

Speeches

* 1841. "The Church and Prejudice"

* 1852. "What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?

"What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?" was a speech delivered by Frederick Douglass on July 5, 1852, at Corinthian Hall in Rochester, New York, at a meeting organized by the Rochester Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society. In the address, Douglass st ...

" In 2020, National Public Radio produced a video of descendants of Douglass reading excerpts from the speech.

* 1859. ''Self-Made Men

"Self-Made Men" is a lecture, first delivered in 1859, by Frederick Douglass, which gives his own definition of the self-made man and explains what he thinks are the means to become such a man.

Douglass's View

Douglass stresses the low origins ...

''.

* 1863, July 6. "Speech at National Hall, for the Promotion of Colored Enlistments."

* 1881.

Legacy and honors

Biographer David Blight

David William Blight (born 1949) is the Sterling Professor of History, of African American Studies, and of American Studies and Director of the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition at Yale University. Previous ...

states that Douglass, "played a pivotal role in America’s Second Founding out of the apocalypse of the Civil War, and he very much wished to see himself as a founder and a defender of the Second American Republic."

Roy Finkenbine argues:

The most influential African American of the nineteenth century, Douglass made a career of agitating the American conscience. He spoke and wrote on behalf of a variety of reform causes: women's rights, temperance, peace, land reform, free public education, and the abolition of capital punishment. But he devoted the bulk of his time, immense talent, and boundless energy to ending slavery and gaining equal rights for African Americans. These were the central concerns of his long reform career. Douglass understood that the struggle for emancipation and equality demanded forceful, persistent, and unyielding agitation. And he recognized that African Americans must play a conspicuous role in that struggle. Less than a month before his death, when a young black man solicited his advice to an African American just starting out in the world, Douglass replied without hesitation: ″Agitate! Agitate! Agitate!″

The Episcopal Church

The Episcopal Church, based in the United States with additional dioceses elsewhere, is a member church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. It is a mainline Protestant denomination and is divided into nine Ecclesiastical provinces and dioces ...

remembers Douglass with a Lesser Feast annually on its liturgical calendar for February 20, the anniversary of his death. Many public schools have also been named in his honor. Douglass still has living descendants today, such as Ken Morris, who is also a descendant of Booker T. Washington

Booker Taliaferro Washington (April 5, 1856November 14, 1915) was an American educator, author, orator, and adviser to several presidents of the United States. Between 1890 and 1915, Washington was the dominant leader in the African-American c ...

. Other honors and remembrances include:

* In 1871, a bust of Douglass was unveiled at Sibley Hall Sibley may refer to:

* Sibley (surname)

* Sibley (automobile)

Places and landmarks

In Canada:

* Sibley Peninsula, Ontario (on Lake Superior)

In the United States:

* Sibley, Illinois

* Sibley, Iowa

* Sibley, Kansas

* Sibley, Louisiana

* Sible ...

, University of Rochester.

* In 1895, the first hospital for black people in Philadelphia, PA was named the Frederick Douglass Memorial Hospital. Black medical professionals, excluded from other facilities, were trained and employed there. In 1948, it merged to form Mercy-Douglass Hospital.

* In 1899, a statue of Frederick Douglass was unveiled in Rochester, New York, making Douglass the first African-American to be so memorialized in the country.

* In 1921, members of the Alpha Phi Alpha

Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. () is the oldest intercollegiate historically African American fraternity. It was initially a literary and social studies club organized in the 1905–1906 school year at Cornell University but later evolved int ...

fraternity (the first African-American intercollegiate fraternity) designated Frederick Douglass as an honorary member. Douglass thus became the only man to receive an honorary membership posthumously.

* The Frederick Douglass Memorial Bridge

The Frederick Douglass Memorial Bridge is a through arch bridge that carries South Capitol Street over the Anacostia River in Washington, D.C. It was completed in 2021 and replaced an older swing bridge that was completed in 1950 as the South ...

, sometimes referred to as the South Capitol Street Bridge, just south of the US Capitol