Franz Josef Archipelago on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

, native_name =

, image_name = Map of Franz Josef Land-en.svg

, image_caption = Map of Franz Josef Land

, image_size =

, map_image = Franz Josef Land location-en.svg

, map_caption = Location of Franz Josef Land

, nickname =

, location =

There are two candidates for the discovery of Franz Josef Land. The first was the Norwegian sealing vessel ''Spidsbergen'', with captain

There are two candidates for the discovery of Franz Josef Land. The first was the Norwegian sealing vessel ''Spidsbergen'', with captain

Nansen's ''Fram'' expedition was an 1893–1896 attempt by the Norwegian explorer

Nansen's ''Fram'' expedition was an 1893–1896 attempt by the Norwegian explorer

''Hertha'' was sent to explore the area, and its captain, I. I. Islyamov hoisted a Russian iron flag at Cape Flora and proclaimed Russian sovereignty over the archipelago. The act was motivated by the ongoing

''Hertha'' was sent to explore the area, and its captain, I. I. Islyamov hoisted a Russian iron flag at Cape Flora and proclaimed Russian sovereignty over the archipelago. The act was motivated by the ongoing

As part of the opening up of Franz Josef Land, the Institute of Geography in Moscow, Stockholm university and Umeå university (Sweden) conducted expeditions to Alexandra Land in August 1990 and August 1991, studying climate- and glacial history by radiocarbon dating raised beaches and antlers from extinct caribou. The work was conducted from a small research base southwest of Nagurskoye, built in 1989. Also in 1990, a collaboration between the Academy of Sciences, the Norwegian Polar Institute and the

As part of the opening up of Franz Josef Land, the Institute of Geography in Moscow, Stockholm university and Umeå university (Sweden) conducted expeditions to Alexandra Land in August 1990 and August 1991, studying climate- and glacial history by radiocarbon dating raised beaches and antlers from extinct caribou. The work was conducted from a small research base southwest of Nagurskoye, built in 1989. Also in 1990, a collaboration between the Academy of Sciences, the Norwegian Polar Institute and the

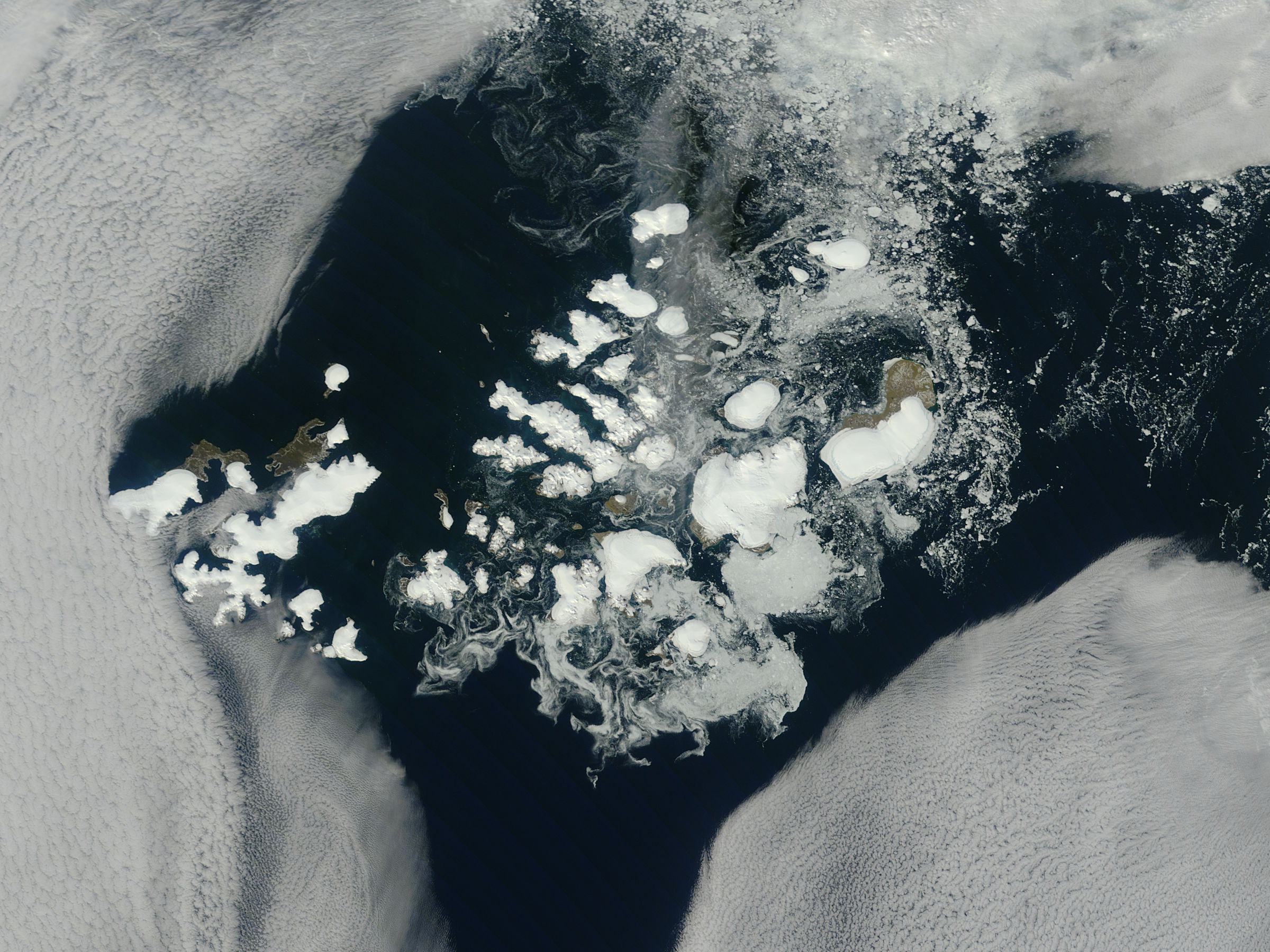

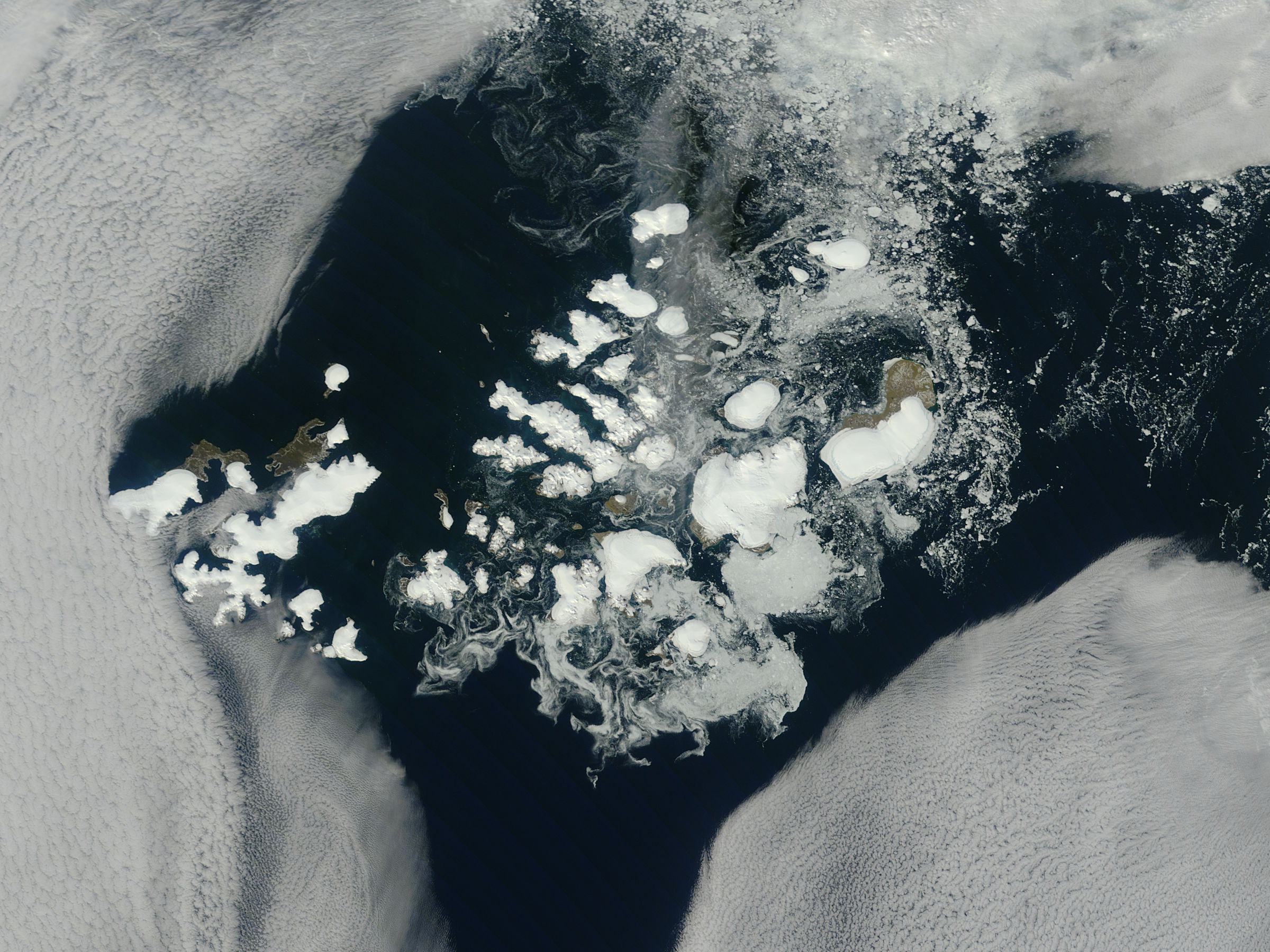

The archipelago constitutes the northernmost part of Russia's Arkhangelsk Oblast, located between 79°46′ and 81°52′ north and 44°52′ and 62°25′ east. It is situated north of

The archipelago constitutes the northernmost part of Russia's Arkhangelsk Oblast, located between 79°46′ and 81°52′ north and 44°52′ and 62°25′ east. It is situated north of

Geologically the archipelago is located on the northern edge of the Barents Sea Platform, within an area where

Geologically the archipelago is located on the northern edge of the Barents Sea Platform, within an area where

Streams only form during the runoff period from May through early September.

Streams only form during the runoff period from May through early September.

Franz Josef Land is in a transition zone between an

Franz Josef Land is in a transition zone between an

The climate and permafrost limits soil development in the archipelago. Large areas are devoid of soil, with permafrost polygons being the most common site for soil to occur. The soil typically has incomplete

The climate and permafrost limits soil development in the archipelago. Large areas are devoid of soil, with permafrost polygons being the most common site for soil to occur. The soil typically has incomplete  Trees, shrubs and tall plants cannot survive. About 150 species of

Trees, shrubs and tall plants cannot survive. About 150 species of

World's Northernmost Islands Added to Russian National Park, written by Brian Clark Howard, National Geographic (Published August 6, 2016, last access 1.may, 2019)

{{Authority control Archipelagoes of the Arctic Ocean Archipelagoes of the Kara Sea Islands of the Barents Sea Archipelagoes of Arkhangelsk Oblast Norway–Soviet Union relations Franz Joseph I of Austria

Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceans. It spans an area of approximately and is known as the coldest of all the oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, a ...

, coordinates =

, archipelago =

, total_islands = 192

, major_islands =

, area_km2 = 16134

, length_km =

, width_km =

, highest_mount = Wilczek Land

Wilczek Land (russian: Земля Вильчека; , german: Wilczek-Land), is an island in the Arctic Ocean at . It is the second-largest island in Franz Josef Land, in Arctic Russia.

This island should not be confused with the small Wilczek I ...

, elevation_m = 670

, population = 0

, population_as_of = 2017

, density_km2 =

, ethnic_groups =

, country =

, country_admin_divisions_title = Federal subject

, country_admin_divisions = Arkhangelsk Oblast

Arkhangelsk Oblast (russian: Арха́нгельская о́бласть, ''Arkhangelskaya oblast'') is a federal subjects of Russia, federal subject of Russia (an oblast). It includes the Arctic Ocean, Arctic archipelagos of Franz Josef Land ...

, additional_info =

Franz Josef Land, Frantz Iosef Land, Franz Joseph Land or Francis Joseph's Land ( rus, Земля́ Фра́нца-Ио́сифа, r=Zemlya Frantsa-Iosifa, no, Fridtjof Nansen Land) is a Russian archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands.

Examples of archipelagos include: the Indonesian Archi ...

in the Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceans. It spans an area of approximately and is known as the coldest of all the oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, a ...

. It is inhabited only by military personnel. It constitutes the northernmost part of Arkhangelsk Oblast

Arkhangelsk Oblast (russian: Арха́нгельская о́бласть, ''Arkhangelskaya oblast'') is a federal subjects of Russia, federal subject of Russia (an oblast). It includes the Arctic Ocean, Arctic archipelagos of Franz Josef Land ...

and consists of 192 islands, which cover an area of , stretching from east to west and from north to south. The islands are categorized in three groups (western, central, and eastern) separated by the British Channel

British Channel (russian: Британский канал) is a strait in the western part of the Franz Josef Land archipelago in Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia. It was first reported and named in 1875 by the Jackson–Harmsworth expedition.

The ...

and the Austrian Strait

Austrian Strait (russian: Австрийский пролив) is a strait in the eastern part of the Franz Josef Land archipelago in Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia. It was first reported and named in 1874 by the Austro-Hungarian North Pole Expedition ...

. The central group is further divided into a northern and southern section by the Markham Sound

Markham Sound ( ru , пролив Маркама) is a strait in the eastern part of the Franz Josef Land archipelago in Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia. It was first reported and named in 1874 by the Austro-Hungarian North Pole Expedition. The nam ...

. The largest island is Prince George Land, which measures , followed by Wilczek Land

Wilczek Land (russian: Земля Вильчека; , german: Wilczek-Land), is an island in the Arctic Ocean at . It is the second-largest island in Franz Josef Land, in Arctic Russia.

This island should not be confused with the small Wilczek I ...

, Graham Bell Island

Graham Bell Island (russian: Остров Греэм-Белл, ''Ostrov Greem-Bell'') is an island in the Franz Josef Archipelago in the Arctic Ocean, and is administratively part of Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia.

Geography

Graham Bell Island is ...

and Alexandra Land

Alexandra Land (russian: Земля Александры, ''Zemlya Aleksandry'') is a large island located in Franz Josef Land, Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russian Federation. Not counting detached and far-lying Victoria Island, it is the westernmost i ...

.

Eighty-five percent of the archipelago is glaciated

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires distinguishing features, such as ...

, with large unglaciated areas on the largest islands and many of the smallest ones. The islands have a combined coastline of . Compared to other Arctic archipelagos, Franz Josef Land has a high dissection rate of 3.6 square kilometers per coastline kilometer. Cape Fligely

Cape Fligely (; ''Mys Fligeli''), is located on the northern shores of Rudolf Island and Franz Josef Land in the Russian Federation, and is the northernmost point of Russia, Europe, and Eurasia as a whole. It is south from the North Pole.

Histo ...

on Rudolf Island

Prince Rudolf Land, Crown Prince Rudolf Land, Prince Rudolf Island or Rudolf Island (russian: Остров Рудольфа) is the northernmost island of the Franz Josef Archipelago, Russia and is home to the northernmost point in Russia.

Owing ...

is the northernmost point of the Eastern Hemisphere

The Eastern Hemisphere is the half of the planet Earth which is east of the prime meridian (which crosses Greenwich, London, United Kingdom) and west of the antimeridian (which crosses the Pacific Ocean and relatively little land from pole to pol ...

. The highest elevations are found in the eastern group, with the highest point located on Wiener Neustadt Land, above mean sea level

Height above mean sea level is a measure of the vertical distance (height, elevation or altitude) of a location in reference to a historic mean sea level taken as a vertical datum. In geodesy, it is formalized as ''orthometric heights''.

The comb ...

.

The archipelago was first spotted by the Norwegian sailors Nils Fredrik Rønnbeck

Nils Fredrik Røn(n)beck ( sv, Rönnbäck, March 22, 1820 – January 4, 1891) was a Swedish-Norwegian polar skipper and ice pilot. He discovered Franz Josef Land in 1865.

Life

Rønnbeck was born Nils Johansson Söderlund in Storön in Kalix, in ...

and Johan Petter Aidijärvi in 1865, although they did not report their finding. The first reported finding was in the 1873 Austro-Hungarian North Pole expedition

The Austro-Hungarian North Pole expedition was an Arctic expedition to find the North-East Passage that ran from 1872 to 1874 under the leadership of Julius Payer and Karl Weyprecht. The expedition discovered and partially explored Franz Josef Lan ...

led by Julius von Payer

Julius Johannes Ludovicus Ritter von Payer (2 September 1841, – 29 August 1915), ennobled Ritter von Payer in 1876, was an officer of the Austro-Hungarian Army, mountaineer, arctic explorer, cartographer, painter, and professor at the There ...

and Karl Weyprecht

Karl Weyprecht, also spelt Carl Weyprecht, (8 September 1838 – 2 March 1881) was an Austro-Hungarian explorer. He was an officer (''k.u.k. Linienschiffsleutnant'') in the Austro-Hungarian Navy. He is most famous as an Arctic explorer, and a ...

, who named the area after Emperor Franz Joseph I

Franz Joseph I or Francis Joseph I (german: Franz Joseph Karl, hu, Ferenc József Károly, 18 August 1830 – 21 November 1916) was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, and the other states of the Habsburg monarchy from 2 December 1848 until his ...

.

In 1926, the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

annexed the islands, which were known at the time as Fridtjof Nansen Land, and settled small outposts for research and military purposes. The Kingdom of Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the ...

rejected the claim and several private expeditions were sent to the islands. With the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

, the islands became off limits for foreigners and two military airfields were built. The islands have been a nature sanctuary since 1994 and became part of the Russian Arctic National Park

Russian Arctic National Park (russian: Национальный парк "Русская Арктика") is a national park of Russia, which was established in June 2009. It was expanded in 2016, and it covers a large and remote area of the Ar ...

in 2012.

History

There are two candidates for the discovery of Franz Josef Land. The first was the Norwegian sealing vessel ''Spidsbergen'', with captain

There are two candidates for the discovery of Franz Josef Land. The first was the Norwegian sealing vessel ''Spidsbergen'', with captain Nils Fredrik Rønnbeck

Nils Fredrik Røn(n)beck ( sv, Rönnbäck, March 22, 1820 – January 4, 1891) was a Swedish-Norwegian polar skipper and ice pilot. He discovered Franz Josef Land in 1865.

Life

Rønnbeck was born Nils Johansson Söderlund in Storön in Kalix, in ...

and harpooner Johan Petter Aidijärvi. They sailed northeast from Svalbard

Svalbard ( , ), also known as Spitsbergen, or Spitzbergen, is a Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. North of mainland Europe, it is about midway between the northern coast of Norway and the North Pole. The islands of the group range ...

in 1865 searching for suitable sealing sites, and they found land that was most likely Franz Josef Land. The account is believed to be factual, but an announcement of the discovery was never made, and their sighting therefore remained unknown to subsequent explorers. This was at the time common to keep newly discovered areas secret, as their discovery was aimed at exploiting them for sealing and whaling, and exposure would cause competitors to flock to the site. Russian scientist N. G. Schilling proposed in 1865 that the ice conditions in the Barents Sea could only be explained if there was another land mass in the area, but he never received funding for an expedition.

The Austro-Hungarian North Pole Expedition

The Austro-Hungarian North Pole expedition was an Arctic expedition to find the North-East Passage that ran from 1872 to 1874 under the leadership of Julius Payer and Karl Weyprecht. The expedition discovered and partially explored Franz Josef Lan ...

of 1872–74 was the first to announce the discovery of the islands. Led by Julius von Payer

Julius Johannes Ludovicus Ritter von Payer (2 September 1841, – 29 August 1915), ennobled Ritter von Payer in 1876, was an officer of the Austro-Hungarian Army, mountaineer, arctic explorer, cartographer, painter, and professor at the There ...

and Karl Weyprecht

Karl Weyprecht, also spelt Carl Weyprecht, (8 September 1838 – 2 March 1881) was an Austro-Hungarian explorer. He was an officer (''k.u.k. Linienschiffsleutnant'') in the Austro-Hungarian Navy. He is most famous as an Arctic explorer, and a ...

of Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

on board the schooner

A schooner () is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schoon ...

''Tegetthoff'', the expedition's primary goal was to find the Northeast Passage

The Northeast Passage (abbreviated as NEP) is the shipping route between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, along the Arctic coasts of Norway and Russia. The western route through the islands of Canada is accordingly called the Northwest Passage (N ...

and its secondary goal to reach the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distinguish from the Mag ...

. Starting in July 1872, the vessel drifted from Novaya Zemlya

Novaya Zemlya (, also , ; rus, Но́вая Земля́, p=ˈnovəjə zʲɪmˈlʲa, ) is an archipelago in northern Russia. It is situated in the Arctic Ocean, in the extreme northeast of Europe, with Cape Flissingsky, on the northern island, ...

to a new landmass, which they named in honor of Franz Joseph I

Franz Joseph I or Francis Joseph I (german: Franz Joseph Karl, hu, Ferenc József Károly, 18 August 1830 – 21 November 1916) was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, and the other states of the Habsburg monarchy from 2 December 1848 until his ...

(1830–1916), Emperor of Austria

The Emperor of Austria (german: Kaiser von Österreich) was the ruler of the Austrian Empire and later the Austro-Hungarian Empire. A hereditary imperial title and office proclaimed in 1804 by Holy Roman Emperor Francis II, a member of the Ho ...

. The expedition contributed significantly to the mapping and exploration of the islands. The next expedition to spot the archipelago was the Dutch Expedition for the Exploration of the Barents Sea, on board the schooner ''Willem Barents''. Constrained by the ice, they never reached land.Barr (1995): 61

Polar exploration

Benjamin Leigh Smith

Benjamin Leigh Smith (12 March 1828 – 4 January 1913) was an English Arctic explorer and yachtsman. He is the grandson of the Radical abolitionist William Smith.

Early life

He was born in Whatlington, Sussex, the extramarital child ...

's expedition in 1880, aboard the barque

A barque, barc, or bark is a type of sailing ship, sailing vessel with three or more mast (sailing), masts having the fore- and mainmasts Square rig, rigged square and only the mizzen (the aftmost mast) Fore-and-aft rig, rigged fore and aft. Som ...

''Eira'', followed a route from Spitsbergen

Spitsbergen (; formerly known as West Spitsbergen; Norwegian: ''Vest Spitsbergen'' or ''Vestspitsbergen'' , also sometimes spelled Spitzbergen) is the largest and the only permanently populated island of the Svalbard archipelago in northern Norw ...

to Franz Josef Land, landing on Bell Island in August. Leigh Smith explored the vicinity and set up a base at Eira Harbour, before exploring towards McClintock Island

MacKlintok Island or McClintock Island (russian: Остров Мак-Клинтока; Ostrov Mak-Klintoka) is an island in Franz Josef Land, Russia.

This island is roughly square-shaped and its maximum length is . Its area is and it is largely ...

. He returned the following year in the same vessel, landing at Grey Bay on George Land.Barr (1995): 62 The explorers were stopped by ice at Cape Flora

Northbrook Island (russian: остров Нортбрук) is an island located in the southern edge of the Franz Josef Archipelago, Russia. Its highest point is 344 m above sea level.

Northbrook Island is one of the most accessible locations ...

, and ''Eira'' sank on 21 August. They built a cottage and stayed the winter,Barr (1995): 63 to be rescued by the British vessels ''Kara'' and ''Hope'' the following summer.Barr (1995): 64 These early expeditions concentrated their explorations on the southern and central parts of the archipelago.Barr (1995): 65

Nansen's ''Fram'' expedition was an 1893–1896 attempt by the Norwegian explorer

Nansen's ''Fram'' expedition was an 1893–1896 attempt by the Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen

Fridtjof Wedel-Jarlsberg Nansen (; 10 October 186113 May 1930) was a Norwegian polymath and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. He gained prominence at various points in his life as an explorer, scientist, diplomat, and humanitarian. He led the team t ...

to reach the geographical North Pole by harnessing the natural east–west current of the Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceans. It spans an area of approximately and is known as the coldest of all the oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, a ...

. Departing in 1893, ''Fram'' drifted from the New Siberian Islands

The New Siberian Islands ( rus, Новосиби́рские Oстрова, r=Novosibirskiye Ostrova; sah, Саҥа Сибиир Aрыылара, translit=Saña Sibiir Arıılara) are an archipelago in the Extreme North of Russia, to the north o ...

for one and a half years before Nansen became impatient and set out to reach the North Pole on skis with Hjalmar Johansen

Fredrik Hjalmar Johansen (15 May 1867 – 3 January 1913) was a Norwegian polar explorer. He participated on the first and third ''Fram'' expeditions. He shipped out with the Fridtjof Nansen expedition in 1893–1896, and accompanied Nansen to ...

. Eventually, they gave up on reaching the pole and instead found their way to Franz Josef Land, the nearest land known to man. They were thus able to establish that there was no large landmass north of this archipelago.Barr (1995): 72 In the meantime the Jackson–Harmsworth Expedition set off in 1894, set up a base on Bell Island, and stayed for the winter. The following season they spent exploring. By pure chance, at Cape Flora

Northbrook Island (russian: остров Нортбрук) is an island located in the southern edge of the Franz Josef Archipelago, Russia. Its highest point is 344 m above sea level.

Northbrook Island is one of the most accessible locations ...

in the spring of 1896, Nansen stumbled upon Frederick George Jackson

Frederick George Jackson (6 March 1860 – 13 March 1938) was an English Arctic explorer remembered for his expedition to Franz Josef Land, when he located the missing Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen.

Biography

Early life

Jackson w ...

, who was able to transport him back to Norway.Barr (1995): 76 Nansen and Jackson explored the northern, eastern, and western portions of the islands.

Once the basic geography of Franz Josef Land had become apparent, expeditions shifted to using the archipelago as a basis to reach the North Pole. The first such attempt was conducted by the National Geographic Society

The National Geographic Society (NGS), headquartered in Washington, D.C., United States, is one of the largest non-profit scientific and educational organizations in the world.

Founded in 1888, its interests include geography, archaeology, and ...

-sponsored American journalist Walter Wellman

Walter E. Wellman (November 3, 1858 – January 31, 1934) was an American journalist, explorer, and aëronaut.

Biographical background

Walter Wellman was born in Mentor, Ohio, in 1858. He was the sixth son of Alonzo Wellman and the fourth by ...

in 1898. The two Norwegians, Paul Bjørvig and Bernt Bentsen, stayed the winter 1898–9 at Cape Heller on Wilczek Land

Wilczek Land (russian: Земля Вильчека; , german: Wilczek-Land), is an island in the Arctic Ocean at . It is the second-largest island in Franz Josef Land, in Arctic Russia.

This island should not be confused with the small Wilczek I ...

, but insufficient fuel caused the latter to die. Wellman returned the following year, but the polar expedition itself was quickly abandoned when they lost most of their equipment. Italian nobleman Luigi Amedeo

Prince Luigi Amedeo, Duke of the Abruzzi, (29 January 1873 – 18 March 1933) was an Italian mountaineer and explorer, briefly Infante of Spain as son of Amadeo I of Spain, member of the royal House of Savoy and cousin of the Italian King Vi ...

organized the next expedition in 1899, on the ''Stella Polare''. They stayed the winter, and in February and again in March 1900 set out towards the pole, but failed to get far.

Evelyn Baldwin

Evelyn may refer to:

Places

* Evelyn, London

*Evelyn Gardens, a garden square in London

* Evelyn, Ontario, Canada

* Evelyn, Michigan, United States

* Evelyn, Texas, United States

* Evelyn, Wirt County, West Virginia, United States

* Evelyn ...

, sponsored by William Ziegler

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Eng ...

, organized the Ziegler Polar Expedition

The Ziegler polar expedition of 1903–1905, also known as the Fiala expedition, was a failed attempt to reach the North Pole. The expedition party remained stranded north of the Arctic Circle for two years before being rescued, yet all but one o ...

of 1901. Setting up a base on Alger Island, he stayed the winter exploring the area, but failed to press northwards. The expedition was largely regarded as an utter failure by the exploration and scientific community, which cited the lack of proper management. Unhappy with the outcome, Ziegler organized a new expedition, for which he appointed Anthony Fiala

Anthony Fiala (September 19, 1869 – April 8, 1950) was an American explorer, born in Jersey City, New Jersey, Jersey City, New Jersey, and educated at Cooper Union and the National Academy of Design, New York City. In early life he was engaged ...

, second-in-command in the first expedition, as leader.Barr (1995): 88 It arrived in 1903 and spent the winter. Their ship, ''America'', was crushed beyond repair in December and disappeared in January. Still, they made two attempts towards the pole, both of which were quickly abandoned. They were forced to stay another year, making yet another unsuccessful attempt at the pole, before being evacuated in 1905 by the '' Terra Nova''.Barr (1995): 92

The first Russian expedition was carried out in 1901, when the icebreaker ''Yermak

Yermak Timofeyevich ( rus, Ерма́к Тимофе́евич, p=jɪˈrmak tʲɪmɐˈfʲejɪvʲɪtɕ; born between 1532 and 1542 – August 5 or 6, 1585) was a Cossacks, Cossack ataman and is today a hero in Russian folklore and myths. During ...

'' traveled to the islands. The next expedition, led by hydrologist Georgy Sedov

Georgy Yakovlevich Sedov (russian: Гео́ргий Я́ковлевич Седо́в; – ) was a Russian Arctic explorer.

Born in the village of Krivaya Kosa of Taganrog district (now Novoazovskyi Raion, Donetsk Oblast) in a fisherman's fami ...

, embarked in 1912 but did not reach the archipelago until the following year because of ice. Among its scientific contributions were the first snow measurements of the archipelago, and the determination that changes of the magnetic field

A magnetic field is a vector field that describes the magnetic influence on moving electric charges, electric currents, and magnetic materials. A moving charge in a magnetic field experiences a force perpendicular to its own velocity and to ...

occur in cycles of fifteen years. It also conducted topographical surveys of the surrounding area. Scurvy set in during the second winter, killing a machinist. Despite lacking prior experience or sufficient provisions, Sedov insisted on pressing forward with a march to the pole. His condition deteriorated and he died on 6 March.

''Hertha'' was sent to explore the area, and its captain, I. I. Islyamov hoisted a Russian iron flag at Cape Flora and proclaimed Russian sovereignty over the archipelago. The act was motivated by the ongoing

''Hertha'' was sent to explore the area, and its captain, I. I. Islyamov hoisted a Russian iron flag at Cape Flora and proclaimed Russian sovereignty over the archipelago. The act was motivated by the ongoing First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and Russian fears of the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

establishing themselves there. The world's first Arctic flight took place in August 1914, when Polish aviator (one of the first pilots of the Russian Navy) Jan Nagórski

Alfons Jan Nagórski (1888–1976), also known as ''Ivan Iosifovich Nagurski'', was a Polish engineer and pioneer of aviation, the first person to fly an airplane in the Arctic and the first aviator to perform a loop with a flying boat.

Biog ...

overflew Franz Josef Land in search of Sedov's group. ''Andromeda'' set out for the same purpose; while failing to locate them, the crew were able to finally determine the non-existence of Peterman Land and King Oscar Land, suspected lands north of the islands.Barr (1995): 134

The Soviet Union

Soviet expeditions were sent almost yearly from 1923. Franz Josef Land had been considered ''terra nullius

''Terra nullius'' (, plural ''terrae nullius'') is a Latin expression meaning " nobody's land".

It was a principle sometimes used in international law to justify claims that territory may be acquired by a state's occupation of it.

:

:

...

'' – land belonging to no one – but on 15 April 1926 the Soviet Union declared its annexation

Annexation (Latin ''ad'', to, and ''nexus'', joining), in international law, is the forcible acquisition of one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. It is generally held to be an illegal act ...

of the archipelago. Emulating Canada's declaration of the sector principle, they pronounced all land between the Soviet mainland and the North Pole to be Soviet territory. This principle has never been internationally recognized.Barr (1995): 95 Both Italy and Norway protested. Norway was first and foremost concerned about its economic interests in the area, in a period when Norwegian hunters and whalers were also being barred from the White Sea

The White Sea (russian: Белое море, ''Béloye móre''; Karelian and fi, Vienanmeri, lit. Dvina Sea; yrk, Сэрако ямʼ, ''Serako yam'') is a southern inlet of the Barents Sea located on the northwest coast of Russia. It is su ...

, Novaya Zemlya and Greenland; the Soviet government, however, largely remained passive, and did not evict Norwegian hunting ships during the following years. Nor did the Soviets interfere when, in 1926, several foreign ships entered the waters in search of the vanished airship

An airship or dirigible balloon is a type of aerostat or lighter-than-air aircraft that can navigate through the air under its own power. Aerostats gain their lift from a lifting gas that is less dense than the surrounding air.

In early ...

''Italia

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

''.

Norway attempted both a diplomatic solution and a Lars Christensen

Lars Christensen (6 April 1884 – 10 December 1965) was a Norwegian shipowner and whaling magnate. He was also a philanthropist with a keen interest in the exploration of Antarctica.

Career

Lars Christensen was born at Sandar in Vestfold, Norw ...

-financed expedition to establish a weather station to gain economic control over the islands, but both failed in 1929.Barr (1995): 96 Instead the Soviet icebreaker ''Sedov Sedov may refer to:

* STS Sedov, a sail training ship

* Sedov (surname)

* Georgiy Sedov (icebreaker)

* 2785 Sedov, an asteroid

* Cape Sedov, an Antarctic ice cape

{{Disambiguation ...

'' set out, led by Otto Schmidt

Otto Yulyevich Shmidt, be, Ота Юльевіч Шміт, Ota Juljevič Šmit (born Otto Friedrich Julius Schmidt; – 7 September 1956), better known as Otto Schmidt, was a Soviet scientist, mathematician, astronomer, geophysicist, statesm ...

, landed in Tikhaya Bay, and began construction of a permanent base. The Soviet government proposed renaming the archipelago Fridtjof Nansen Land in 1930, but the name never came into use. In 1930 the Norwegian Bratvaag Expedition

The ''Bratvaag'' Expedition was a Norwegian expedition in 1930 led by Dr. Gunnar Horn, whose official tasks were hunting seals and to study glaciers and seas in the Svalbard Arctic region. The name of the expedition was taken from its ship, M/S ...

visited the archipelago, but was asked by Soviet authorities to respect Soviet territorial water in the future. Other expeditions that year were the Norwegian-Swedish balloon expedition led by Hans Wilhelmsson Ahlmann

Hans Jakob Konrad Wilhelmsson Ahlmann (14 November 1889 – 10 March 1974) was a Swedish geographer, glaciologist, and diplomat.

Born in Karlsborg, Sweden, Ahlmann grew up in Stockholm. He studied with Professor Gerard De Geer at Stockholm Unive ...

on ''Quest'' and the German airship '' Graf Zeppelin''. Except for a German weather station emplaced during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, these were the last Western expeditions to Franz Josef Land until 1990.Barr (1995): 100

Soviet activities grew rapidly following the International Polar Year

The International Polar Years (IPY) are collaborative, international efforts with intensive research focus on the polar regions. Karl Weyprecht, an Austro-Hungarian naval officer, motivated the endeavor in 1875, but died before it first occurred i ...

in 1932. The archipelago was circumnavigated, people landed on Victoria Island, and a topographical map

In modern mapping, a topographic map or topographic sheet is a type of map characterized by large- scale detail and quantitative representation of relief features, usually using contour lines (connecting points of equal elevation), but historic ...

was completed. In 1934–35 geological and glaciological expeditions were carried out, cartographic flights were flown, and up to sixty people stayed the winters between 1934 and 1936, which also saw the first birth. The first drifting ice station

A drifting ice station is a temporary or semi-permanent facility built on an ice floe. During the Cold War the Soviet Union and the United States maintained a number of stations in the Arctic Ocean on floes such as Fletcher's Ice Island for rese ...

was set up out of Rudolf Island in 1936.Barr (1995): 138 An airstrip

An aerodrome (Commonwealth English) or airdrome (American English) is a location from which aircraft flight operations take place, regardless of whether they involve air cargo, passengers, or neither, and regardless of whether it is for publ ...

was then constructed on a glacier on the island, and by 1937 the winter population hit 300.

Activity dwindled during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

and only a small group of men were kept at Rudolf Island, remaining unsupplied throughout the war. They never discovered Nazi Germany's establishment of a weather station, named Schatzgräber, on Alexandra Land

Alexandra Land (russian: Земля Александры, ''Zemlya Aleksandry'') is a large island located in Franz Josef Land, Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russian Federation. Not counting detached and far-lying Victoria Island, it is the westernmost i ...

as part of the North Atlantic weather war

The North Atlantic weather war occurred during World War II. The Allies (Britain in particular) and Germany tried to gain a monopoly on weather data in the North Atlantic and Arctic oceans. Meteorological intelligence was important as it affect ...

. The German station was evacuated in 1944 after the men were struck by trichinosis

Trichinosis, also known as trichinellosis, is a parasitic disease caused by roundworms of the ''Trichinella'' type. During the initial infection, invasion of the intestines can result in diarrhea, abdominal pain, and vomiting. Migration of larv ...

from eating polar bear

The polar bear (''Ursus maritimus'') is a hypercarnivorous bear whose native range lies largely within the Arctic Circle, encompassing the Arctic Ocean, its surrounding seas and surrounding land masses. It is the largest extant bear specie ...

meat. Apparent physical evidence of the base was discovered in 2016.

The Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

produced renewed Soviet interest in the islands because of their strategic military significance. The islands were regarded as an "unsinkable aircraft carrier". The site of the former German weather station was selected as the location of a Soviet aerodrome and military base, Nagurskoye

Nagurskoye (russian: Нагу́рское; also written as Nagurskoye, or Nagurskaja) is an airfield in Alexandra Land in Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia located north of Murmansk. It is an extremely remote Arctic base and Russia's northernmost mi ...

. With the advent of intercontinental ballistic missiles

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more thermonuclear warheads). Conventional, chemical, and biological weapons ca ...

, the Soviet Union changed its military strategy in 1956, abolishing the strategic need for an airbase on the archipelago. The International Geophysical Year

The International Geophysical Year (IGY; french: Année géophysique internationale) was an international scientific project that lasted from 1 July 1957 to 31 December 1958. It marked the end of a long period during the Cold War when scientific ...

of 1957 and 1958 gave a new rise to the scientific interest in the archipelago and an airstrip was built on Heiss Island in 1956. The following year the geophysical Ernst Krenkel Observatory

Ernst Krenkel Observatory (russian: Обсерватория имени Эрнста Кренкеля), also known as Kheysa, was a former Soviet rocket launching site located on Heiss Island, Franz Josef Land. It is named after a famous Arctic ex ...

was established there.Barr (1995): 141 Activity at Tikhaya Bay was closed in 1959.

Because of the islands' military significance, the Soviet Union closed off the area to foreign researchers, although Soviet researchers carried out various expeditions, including in geophysics, studies of the ionosphere

The ionosphere () is the ionized part of the upper atmosphere of Earth, from about to above sea level, a region that includes the thermosphere and parts of the mesosphere and exosphere. The ionosphere is ionized by solar radiation. It plays an ...

, marine biology, botany, ornithology, and glaciology.Barr (1995): 144 The Soviet Union opened up the archipelago for international activities from 1990, with foreigners having fairly straightforward access.Barr (1995): 104

Recent history

As part of the opening up of Franz Josef Land, the Institute of Geography in Moscow, Stockholm university and Umeå university (Sweden) conducted expeditions to Alexandra Land in August 1990 and August 1991, studying climate- and glacial history by radiocarbon dating raised beaches and antlers from extinct caribou. The work was conducted from a small research base southwest of Nagurskoye, built in 1989. Also in 1990, a collaboration between the Academy of Sciences, the Norwegian Polar Institute and the

As part of the opening up of Franz Josef Land, the Institute of Geography in Moscow, Stockholm university and Umeå university (Sweden) conducted expeditions to Alexandra Land in August 1990 and August 1991, studying climate- and glacial history by radiocarbon dating raised beaches and antlers from extinct caribou. The work was conducted from a small research base southwest of Nagurskoye, built in 1989. Also in 1990, a collaboration between the Academy of Sciences, the Norwegian Polar Institute and the Polish Academy of Sciences

The Polish Academy of Sciences ( pl, Polska Akademia Nauk, PAN) is a Polish state-sponsored institution of higher learning. Headquartered in Warsaw, it is responsible for spearheading the development of science across the country by a society of ...

resulted in the first of several archaeological expeditions organized by the Institute of Culture in Moscow. The military base on Graham Bell Island was abandoned in the early 1990s. The military presence at Nagurskoye was reduced to that of a border post, and the number of people stationed at Krenkel Observatory was reduced from 70 to 12. The archipelago and the surrounding waters were declared a nature reserve

A nature reserve (also known as a wildlife refuge, wildlife sanctuary, biosphere reserve or bioreserve, natural or nature preserve, or nature conservation area) is a protected area of importance for flora, fauna, or features of geological or ...

in April 1994. The opening of the archipelago also saw the introduction of tourism, most of which takes place on Russian-operated icebreakers.Barr (1995): 152 In 2011, in a move to better accommodate tourism in the archipelago, the Russian Arctic National Park

Russian Arctic National Park (russian: Национальный парк "Русская Арктика") is a national park of Russia, which was established in June 2009. It was expanded in 2016, and it covers a large and remote area of the Ar ...

was expanded to include Franz Josef Land. However, in August 2019, Russia abruptly withdrew its approval for a Norwegian cruise ship to visit the islands.

In 2012, the Russian Air Force

" Air March"

, mascot =

, anniversaries = 12 August

, equipment =

, equipment_label =

, battles =

, decorations =

, bat ...

decided to reopen the Graham Bell Airfield as part of a series of reopenings of air bases in the Arctic. A major new base, named the ''Arctic Trefoil'' for its three lobed structure, was constructed at Nagurskoye

Nagurskoye (russian: Нагу́рское; also written as Nagurskoye, or Nagurskaja) is an airfield in Alexandra Land in Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia located north of Murmansk. It is an extremely remote Arctic base and Russia's northernmost mi ...

. It can maintain 150 soldiers for 18 months and has an area of 14,000 square meters.

In 2017, Russian president Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin; (born 7 October 1952) is a Russian politician and former intelligence officer who holds the office of president of Russia. Putin has served continuously as president or prime minister since 1999: as prime min ...

visited the archipelago.

In August 2019, a geographic expedition by Russian Northern Fleet

Severnyy flot

, image = Great emblem of the Northern Fleet.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Northern Fleet's great emblem

, start_date = June 1, 1733; Sov ...

discovered several new islands in the archipelago. They were previously buried under Vylki Glacier until part of it melted.

In April 2020, the archipelago was used by the Russian Airborne Forces

The Russian Airborne Forces (russian: Воздушно-десантные войска России, ВДВ, Vozdushno-desantnye voyska Rossii, VDV) are the airborne forces branch of the Russian Armed Forces. It was formed in 1992 from units o ...

to perform the world's first high-altitude military parachuting

High-altitude military parachuting, or military free fall (MFF), is a method of delivering military personnel, military equipment, and other military supplies from a transport aircraft at a high altitude via free-fall parachute insertion. Two ...

(HALO) paradrop

A parachute is a device used to slow the motion of an object through an atmosphere by creating drag or, in a ram-air parachute, aerodynamic lift. A major application is to support people, for recreation or as a safety device for aviators, who ...

from the lower border of the Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar regions of Earth, polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenla ...

stratosphere

The stratosphere () is the second layer of the atmosphere of the Earth, located above the troposphere and below the mesosphere. The stratosphere is an atmospheric layer composed of stratified temperature layers, with the warm layers of air ...

. The crews of Il-76

The Ilyushin Il-76 (russian: Илью́шин Ил-76; NATO reporting name: Candid) is a multi-purpose, fixed-wing, four-engine turbofan strategic airlifter designed by the Soviet Union's Ilyushin design bureau. It was first planned as a commer ...

aircraft practiced at the northernmost airfield of the country on the island

An island (or isle) is an isolated piece of habitat that is surrounded by a dramatically different habitat, such as water. Very small islands such as emergent land features on atolls can be called islets, skerries, cays or keys. An island ...

of Franz Josef Land. Not only did the paratroopers endure the partial oxygen of the stratosphere common under the HALO technique; they encountered deep freeze conditions mitigated by military tested oxygen tanks and uniforms. Challenges to the Arctic mission included undirected terrain, in the absence of ground navigation systems. During the end of the mission, the paratroopers spent a day during which they conducted classes on survival in Arctic conditions and built shelters from snow.

Geography

The archipelago constitutes the northernmost part of Russia's Arkhangelsk Oblast, located between 79°46′ and 81°52′ north and 44°52′ and 62°25′ east. It is situated north of

The archipelago constitutes the northernmost part of Russia's Arkhangelsk Oblast, located between 79°46′ and 81°52′ north and 44°52′ and 62°25′ east. It is situated north of Novaya Zemlya

Novaya Zemlya (, also , ; rus, Но́вая Земля́, p=ˈnovəjə zʲɪmˈlʲa, ) is an archipelago in northern Russia. It is situated in the Arctic Ocean, in the extreme northeast of Europe, with Cape Flissingsky, on the northern island, ...

and east of the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard

Svalbard ( , ), also known as Spitsbergen, or Spitzbergen, is a Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. North of mainland Europe, it is about midway between the northern coast of Norway and the North Pole. The islands of the group range ...

.Barr (1995): 8 Located within the Arctic Ocean, Franz Josef Land constitutes the northeastern border of the Barents Sea and the northwestern border of the Kara Sea. The islands are from the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distinguish from the Mag ...

and from the Yamal Peninsula

The Yamal Peninsula (russian: полуостров Ямал, poluostrov Yamal) is located in the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug of northwest Siberia, Russia. It extends roughly 700 km (435 mi) and is bordered principally by the Kara ...

, the closest point of the Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelago a ...

n mainland. The archipelago falls within varying definitions of the Asia–Europe border, and is therefore variously defined as part of Asia or of Europe. Cape Flighely, situated at 81°50′ north, is the northernmost point in Eurasia and the Eastern Hemisphere

The Eastern Hemisphere is the half of the planet Earth which is east of the prime meridian (which crosses Greenwich, London, United Kingdom) and west of the antimeridian (which crosses the Pacific Ocean and relatively little land from pole to pol ...

, and of either Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

or Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an area ...

, depending on the continental definition. It is the third-closest landmass to the North Pole.Lück (2008): 182

The archipelago comprises 191 uninhabited islands with a combined area of . These stretch from east to west and from north to south. One can categorize the islands into three groups, a western, central and eastern, separated by the British Channel and the Austrian Strait. The central group is further divided into a northern and southern section by the Markham Strait. Graham Bell Island is separated from the eastern group by the Severo–Vostochnyi Strait.Barr (1995): 9 There are two named island clusters: Zichy Land

Zichy Land (russian: Земля Зичи; ''Zemlya Zichy'') is a geographical subgroup of Franz Josef Land, Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia.

It is formed by the central cluster of large islands in the midst of the archipelago. The islands are separate ...

north of Markham Sound

Markham Sound ( ru , пролив Маркама) is a strait in the eastern part of the Franz Josef Land archipelago in Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia. It was first reported and named in 1874 by the Austro-Hungarian North Pole Expedition. The nam ...

; and Belaya Zemlya

, native_name =

, image_name = Belaya Zemlya 2020-07-29 Sentinel-2 L2A Highlight Optimized Natural Color.jpg

, image_caption = Sentinel-2 image (2020)

, image_size =

, map_image = Kara sea ZFJBZ.PNG

, map_caption ...

to the extreme northeast. The straits are narrow, between several hundred meters to wide. They reach depths of , below the shelf of the Barents Sea.

The largest island is Prince George Land, which measures . Three additional islands exceed in size: Wilczek Land

Wilczek Land (russian: Земля Вильчека; , german: Wilczek-Land), is an island in the Arctic Ocean at . It is the second-largest island in Franz Josef Land, in Arctic Russia.

This island should not be confused with the small Wilczek I ...

, Graham Bell Island

Graham Bell Island (russian: Остров Греэм-Белл, ''Ostrov Greem-Bell'') is an island in the Franz Josef Archipelago in the Arctic Ocean, and is administratively part of Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia.

Geography

Graham Bell Island is ...

and Alexandra Land

Alexandra Land (russian: Земля Александры, ''Zemlya Aleksandry'') is a large island located in Franz Josef Land, Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russian Federation. Not counting detached and far-lying Victoria Island, it is the westernmost i ...

. Five more islands exceed : Hall Island, Salisbury Island Salisbury Island may refer to:

* Salisbury Island (California), United States

* Salisbury Island (Nunavut), Canada

*Salisbury Island (Russia)

*Salisbury Island (Western Australia), Australia

*Iona Island (New York), once known as Salisbury Island

...

, McClintock Island

MacKlintok Island or McClintock Island (russian: Остров Мак-Клинтока; Ostrov Mak-Klintoka) is an island in Franz Josef Land, Russia.

This island is roughly square-shaped and its maximum length is . Its area is and it is largely ...

, Jackson Island

Jackson Island (russian: Остров Джексона, ''Ostrov Dzheksona'') is an island located in Franz Josef Land, Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russian Federation. This island is part of the Zichy Land subgroup of the central part of the archipelago ...

and Hooker Island

Hooker Island (russian: остров Гукера; ''Ostrov Gukera'') is one of the central islands of Franz Josef Land. It is located in the central area of the archipelago at . It is administered by the Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia.

History

Hoo ...

. The smallest 135 islands constitute 0.4 percent of the archipelago's area. The highest elevation is a peak on Wilczek Land, which rises above mean sea level. Victoria Island

Victoria Island ( ikt, Kitlineq, italic=yes) is a large island in the Arctic Archipelago that straddles the boundary between Nunavut and the Northwest Territories of Canada. It is the List of islands by area, eighth-largest island in the world, ...

, located to the west of Alexandra Land, is administratively part of the archipelago, but the island is not geographically part of the island group and is closer to Svalbard, located from Kvitøya

Kvitøya (English: "White Island") is an island in the Svalbard archipelago in the Arctic Ocean, with an area of . It is the easternmost part of the Kingdom of Norway. The closest Russian Arctic possession, Victoria Island, lies only to the ea ...

.

Geology

Geologically the archipelago is located on the northern edge of the Barents Sea Platform, within an area where

Geologically the archipelago is located on the northern edge of the Barents Sea Platform, within an area where Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceo ...

sedimentary

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock (geology), rock that are formed by the accumulation or deposition of mineral or organic matter, organic particles at Earth#Surface, Earth's surface, followed by cementation (geology), cementation. Sedimentati ...

rocks are exposed. The area has four units

Unit may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* UNIT, a fictional military organization in the science fiction television series ''Doctor Who''

* Unit of action, a discrete piece of action (or beat) in a theatrical presentation

Music

* ''Unit'' (alb ...

separated by regional erosion surface

In geology and geomorphology, an erosion surface is a surface of rock or regolith that was formed by erosion and not by construction (e.g. lava flows, sediment deposition) nor fault displacement. Erosional surfaces within the stratigraphic reco ...

s. The Upper Paleozoic

The Paleozoic (or Palaeozoic) Era is the earliest of three geologic eras of the Phanerozoic Eon.

The name ''Paleozoic'' ( ;) was coined by the British geologist Adam Sedgwick in 1838

by combining the Greek words ''palaiós'' (, "old") and ' ...

unit is poorly exposed and was created by folding

Fold, folding or foldable may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Fold'' (album), the debut release by Australian rock band Epicure

* Fold (poker), in the game of poker, to discard one's hand and forfeit interest in the current pot

*Abov ...

during the Caledonian period. The Lower Mesozoic unit, consisting of coastal and marine sediment

Sediment is a naturally occurring material that is broken down by processes of weathering and erosion, and is subsequently transported by the action of wind, water, or ice or by the force of gravity acting on the particles. For example, sand an ...

s from the Upper Triassic

The Triassic ( ) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.6 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.36 Mya. The Triassic is the first and shortest period ...

period, is present on most islands and on the bottom of the straits and consists of limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms whe ...

s, shale

Shale is a fine-grained, clastic sedimentary rock formed from mud that is a mix of flakes of clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4) and tiny fragments (silt-sized particles) of other minerals, especial ...

s, sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicates) ...

s and conglomerate.

The Upper Mesozoic unit dominates in the southern and western parts, consisting of massive effusive

In physics and chemistry, effusion is the process in which a gas escapes from a container through a hole of diameter considerably smaller than the mean free path of the molecules. Such a hole is often described as a ''pinhole'' and the escape ...

rocks made up of basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanite, aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the planetary surface, surface of a terrestrial ...

ic sheets separated by volcanic ash

Volcanic ash consists of fragments of rock, mineral crystals, and volcanic glass, created during volcano, volcanic eruptions and measuring less than 2 mm (0.079 inches) in diameter. The term volcanic ash is also often loosely used t ...

es and tuff

Tuff is a type of rock made of volcanic ash ejected from a vent during a volcanic eruption. Following ejection and deposition, the ash is lithified into a solid rock. Rock that contains greater than 75% ash is considered tuff, while rock cont ...

s, mixed with terrigenous

In oceanography, terrigenous sediments are those derived from the erosion of rocks on land; that is, they are derived from ''terrestrial'' (as opposed to marine) environments. Consisting of sand, mud, and silt carried to sea by rivers, their ...

rocks with layers of coal. The Mesozoic-Tertiary unit remains mostly on the sea floor and consist of marine quartz

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica (silicon dioxide). The atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon-oxygen tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tetrahedra, giving an overall chemical form ...

sandstones and shales. Plate tectonics

Plate tectonics (from the la, label=Late Latin, tectonicus, from the grc, τεκτονικός, lit=pertaining to building) is the generally accepted scientific theory that considers the Earth's lithosphere to comprise a number of large ...

of the Arctic Ocean created basalt lava

Lava is molten or partially molten rock (magma) that has been expelled from the interior of a terrestrial planet (such as Earth) or a moon onto its surface. Lava may be erupted at a volcano or through a fracture in the crust, on land or un ...

s and dolerite

Diabase (), also called dolerite () or microgabbro,

is a mafic, holocrystalline, subvolcanic rock equivalent to volcanic basalt or plutonic gabbro. Diabase dikes and sills are typically shallow intrusive bodies and often exhibit fine-grained ...

sheets and dykes in the Upper Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The J ...

and Lower Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of th ...

periods. The land is rising by per year, due to the melting of the Barents Sea Ice Sheet c. 10,000 years ago.

Hydrology

Franz Josef Land is dominated by glaciation, which covers an area of , or 85 percent of the archipelago. The glaciers have an average thickness of , which would convert to . This would alone give aeustatic

Mean sea level (MSL, often shortened to sea level) is an average surface level of one or more among Earth's coastal bodies of water from which heights such as elevation may be measured. The global MSL is a type of vertical datuma standardised g ...

rise in sea level

Mean sea level (MSL, often shortened to sea level) is an average surface level of one or more among Earth's coastal bodies of water from which heights such as elevation may be measured. The global MSL is a type of vertical datuma standardised g ...

should it melt. Large ice-free areas are only found on the largest islands, such as the Armitage Peninsula of George Land, the Kholmistyi Peninsula of Graham Bell Island, the Central'naya Susha of Alexandra Land, the Ganza Point of Wilczek Land and the Heyes Island. Most of the smaller islands are unglaciated.

Permafrost

Permafrost is ground that continuously remains below 0 °C (32 °F) for two or more years, located on land or under the ocean. Most common in the Northern Hemisphere, around 15% of the Northern Hemisphere or 11% of the global surface ...

causes most of the runoff to take place on the surface, with streams only forming on the largest islands. The longest river is long and forms on George Land, while there are several streams on Alexandra Land, the longest being . There are about one thousand lakes in the archipelago, the majority of which are located on Alexandra Land and George Land. Most lakes are located in depressions caused by glacial erosion, in addition to a smaller number of lagoon lakes. Their sizes vary from to . Most are only deep, with the deepest measured at .

The sea current

Currents, Current or The Current may refer to:

Science and technology

* Current (fluid), the flow of a liquid or a gas

** Air current, a flow of air

** Ocean current, a current in the ocean

*** Rip current, a kind of water current

** Current (stre ...

s surrounding the archipelago touch eastern Svalbard and northern Novaya Zemlya. The cold Makarov Current flows from the north and the Arctic Current flows from the northwest, while the warmer Novaya Zemlya Current flows from the south. The latter has temperatures over , while the bottom water lies below . The southern coastal regions of the archipelago experience currents from east to west. Average velocity is between per second. The tidal component in coastal areas is per second. Pack ice

Drift ice, also called brash ice, is sea ice that is not attached to the shoreline or any other fixed object (shoals, grounded icebergs, etc.).Leppäranta, M. 2011. The Drift of Sea Ice. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. Unlike fast ice, which is "fasten ...

occurs throughout the year around the entire island group, with the lowest levels being during August and September. One-year winter ice starts forming in October and reaches a thickness of . Icebergs

An iceberg is a piece of freshwater ice more than 15 m long that has broken off a glacier or an ice shelf and is floating freely in open (salt) water. Smaller chunks of floating glacially-derived ice are called "growlers" or "bergy bits". The ...

are common year-round.

Climate

Franz Josef Land is in a transition zone between an

Franz Josef Land is in a transition zone between an ice cap climate

An ice cap climate is a polar climate where no mean monthly temperature exceeds . The climate covers areas in or near the high latitudes (65° latitude) to polar regions (70–90° north and south latitude), such as Antarctica, some of the northe ...

(EF) and a tundra climate

The tundra climate is a polar climate sub-type located in high latitudes and high mountains. undra climate https://www.britannica.com/science/tundra-climateThe Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2019 It is classified as ET according to Köppen ...

(ET), technically falling into the latter because July and August average above freezing, nevertheless, low temperatures remain below freezing year round. The main forces influencing the climate are the glaciation and sea ice. At 81° north the archipelago experiences 141 annual days of midnight sun

The midnight sun is a natural phenomenon that occurs in the summer months in places north of the Arctic Circle or south of the Antarctic Circle, when the Sun remains visible at the local midnight. When the midnight sun is seen in the Arctic, t ...

, from 12 April to 30 August. During the winter it experiences 128 days of polar night

The polar night is a phenomenon where the nighttime lasts for more than 24 hours that occurs in the northernmost and southernmost regions of Earth. This occurs only inside the polar circles. The opposite phenomenon, the polar day, or midnig ...

from 19 October to 23 February. Abundant cloud cover further cools the climate. The sea starts to freeze in late September and reaches its annual maximum in March, at which time ninety-five percent of the sea is ice-covered. The ice coverage starts to decrease in May and experiences major melting in June, with the minimum occurring in August or early September.

During winter, high-pressure weather and clear skies cause radiation loss from the ground, sending temperatures down to . During shifts the temperatures can change by within hours. Coastal stations experience mean January temperatures of between and , varying heavily from year to year depending on the degree of cycles in weather patterns. During summer the temperatures are a lot more even and average at between and at Hayes Island. Fog is most common during the summer. Average annual precipitation at the coastal stations is between , with the wettest months being from July through September. Elevated areas can experience considerably higher precipitation. Franz Josef Land is significantly colder than Spitsbergen

Spitsbergen (; formerly known as West Spitsbergen; Norwegian: ''Vest Spitsbergen'' or ''Vestspitsbergen'' , also sometimes spelled Spitzbergen) is the largest and the only permanently populated island of the Svalbard archipelago in northern Norw ...

, which experiences warmer winter averages, but is warmer than the Canadian Arctic Archipelago

The Arctic Archipelago, also known as the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, is an archipelago lying to the north of the Canadian continental mainland, excluding Greenland (an autonomous territory of Denmark).

Situated in the northern extremity of No ...

.

Nature

soil profile

A soil horizon is a layer parallel to the soil surface whose physical, chemical and biological characteristics differ from the layers above and beneath. Horizons are defined in many cases by obvious physical features, mainly colour and texture. ...

s and polygonal form with rich content of iron and either neutral or slightly acidic. The brown upper humus

In classical soil science, humus is the dark organic matter in soil that is formed by the decomposition of plant and animal matter. It is a kind of soil organic matter. It is rich in nutrients and retains moisture in the soil. Humus is the Lati ...

layers have three percent organic matter, increasing to eight percent in the southernmost islands. Arctic desert soils occur on the eastern group islands, while the areas near the edge of the glaciers have bog-like arctic soil.

The flora

Flora is all the plant life present in a particular region or time, generally the naturally occurring (indigenous) native plants. Sometimes bacteria and fungi are also referred to as flora, as in the terms '' gut flora'' or '' skin flora''.

E ...

varies between islands, based on the natural conditions. On some islands, vegetation

Vegetation is an assemblage of plant species and the ground cover they provide. It is a general term, without specific reference to particular taxa, life forms, structure, spatial extent, or any other specific botanical or geographic character ...

is limited to lichen

A lichen ( , ) is a composite organism that arises from algae or cyanobacteria living among filaments of multiple fungi species in a mutualistic relationship.nunatak

A nunatak (from Inuit ''nunataq'') is the summit or ridge of a mountain that protrudes from an ice field or glacier that otherwise covers most of the mountain or ridge. They are also called glacial islands. Examples are natural pyramidal peaks. ...

s and snow algae

Snow algae are a group of freshwater micro-algae which grow in the alpine and polar regions of the earth. These algae have been observed to come in a variety of colors associated with both the individual species, stage of life or topography/geogra ...

on glacier surfaces.Barr (1995): 33

Trees, shrubs and tall plants cannot survive. About 150 species of

Trees, shrubs and tall plants cannot survive. About 150 species of bryophyte

The Bryophyta s.l. are a proposed taxonomic division containing three groups of non-vascular land plants (embryophytes): the liverworts, hornworts and mosses. Bryophyta s.s. consists of the mosses only. They are characteristically limited in ...

s dominate the grassy turf, of which two-thirds are moss

Mosses are small, non-vascular flowerless plants in the taxonomic division Bryophyta (, ) '' sensu stricto''. Bryophyta (''sensu lato'', Schimp. 1879) may also refer to the parent group bryophytes, which comprise liverworts, mosses, and hor ...

es and a third liverwort

The Marchantiophyta () are a division of non-vascular land plants commonly referred to as hepatics or liverworts. Like mosses and hornworts, they have a gametophyte-dominant life cycle, in which cells of the plant carry only a single set of g ...

s. The most common species are ''Aulacomnium'', ''Ditrichum'', ''Drepanocladus'', ''Orthothecium'' and ''Tomenthypnum''. More than 100 species of lichen are found on the island, the most common being ''Caloplaca

''Caloplaca'' is a lichen genus comprising a number of distinct species. Members of the genus are commonly called firedot lichen, jewel lichen.Field Guide to California Lichens, Stephen Sharnoff, Yale University Press, 2014, gold lichens, "ora ...

'', ''Lecanora

''Lecanora'' is a genus of lichen commonly called rim lichens.Field Guide to California Lichens, Stephen Sharnoff, Yale University Press, 2014, Lichens in the genus ''Squamarina'' are also called rim lichens. Members of the genus have roughly ci ...

'', ''Lecidea

''Lecidea'' is a genus of crustose lichens with a carbon black ring or outer margin (exciple) around the fruiting body disc (apothecium), usually (or always) found growing on (saxicolous) or in (endolithic) rock.Field Guide to California Lichens, ...

'', ''Ochrolechia

''Ochrolechia'' is a genus of crustose lichens in the family Ochrolechiaceae.

Species

, Species Fungorum accepts 38 species of ''Ochrolechia'':

*'' Ochrolechia aegaea''

*'' Ochrolechia africana''

*'' Ochrolechia alaskana''

*'' Ochrolechia a ...

'' and ''Rinodina

''Rinodina'' is a genus of lichen-forming fungi in the family Physciaceae. The genus has a widespread distribution and contains about 265 species. It is hypothesized that a few saxicolous lichen, saxicolous species common to dry regions of wester ...

''. There are sixteen species of grass

Poaceae () or Gramineae () is a large and nearly ubiquitous family of monocotyledonous flowering plants commonly known as grasses. It includes the cereal grasses, bamboos and the grasses of natural grassland and species cultivated in lawns an ...

and about 100 species of algae

Algae (; singular alga ) is an informal term for a large and diverse group of photosynthetic eukaryotic organisms. It is a polyphyletic grouping that includes species from multiple distinct clades. Included organisms range from unicellular mic ...

, most commonly Cyanophyta

Cyanobacteria (), also known as Cyanophyta, are a phylum of gram-negative bacteria that obtain energy via photosynthesis. The name ''cyanobacteria'' refers to their color (), which similarly forms the basis of cyanobacteria's common name, blue ...

and Diatomea

A diatom ( Neo-Latin ''diatoma''), "a cutting through, a severance", from el, διάτομος, diátomos, "cut in half, divided equally" from el, διατέμνω, diatémno, "to cut in twain". is any member of a large group comprising se ...

.Barr (1995): 35 Fifty-seven species of vascular plant

Vascular plants (), also called tracheophytes () or collectively Tracheophyta (), form a large group of land plants ( accepted known species) that have lignified tissues (the xylem) for conducting water and minerals throughout the plant. They al ...

s have been reported. The most common are Arctic poppy and saxifraga

''Saxifraga'' is the largest genus in the family Saxifragaceae, containing about 465 species of holarctic perennial plants, known as saxifrages or rockfoils. The Latin word ''saxifraga'' means literally "stone-breaker", from Latin ' ("rock" or " ...

, which grow everywhere, independent of habitat, with the latter's nine species being found on all islands. Common plants in wet areas are '' Alopecurus magellanicus'' (alpine meadow- foxtail grass), buttercup

''Ranunculus'' is a large genus of about almost 1700 to more than 1800 species of flowering plants in the family Ranunculaceae. Members of the genus are known as buttercups, spearworts and water crowfoots.

The genus is distributed in Europe, ...

s and polar willow. ''Alopecurus magellanicus'' and ''Papaver dahlianum

''Papaver dahlianum'', commonly called the Svalbard poppy, is a poppy species common on Svalbard, north-eastern Greenland and a small area of northern Norway. It is the symbolic flower of Svalbard. Some sources regard this species as part of ''P ...

'' are the tallest plants, able to reach heights of .

More than one hundred taxa

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; plural taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular nam ...

of single-cell pelagic

The pelagic zone consists of the water column of the open ocean, and can be further divided into regions by depth (as illustrated on the right). The word ''pelagic'' is derived . The pelagic zone can be thought of as an imaginary cylinder or wa ...

algae

Algae (; singular alga ) is an informal term for a large and diverse group of photosynthetic eukaryotic organisms. It is a polyphyletic grouping that includes species from multiple distinct clades. Included organisms range from unicellular mic ...

have been identified around the archipelago, the most common being ''Thalassiosira antarctica

''Thalassiosira'' is a genus of centric diatoms, comprising over 100 marine and freshwater species. It is a diverse group of photosynthetic eukaryotes that make up a vital part of marine and freshwater ecosystems, in which they are key primary pr ...

'' and '' Chaetoceros decipiens''. The bloom takes place between May and August. Of the roughly fifty species of zooplankton

Zooplankton are the animal component of the planktonic community ("zoo" comes from the Greek word for ''animal''). Plankton are aquatic organisms that are unable to swim effectively against currents, and consequently drift or are carried along by ...

, calanoid

Calanoida is an order of copepods, a group of arthropods commonly found as zooplankton. The order includes around 46 families with about 1800 species of both marine and freshwater copepods between them.

Description

Calanoids can be distinguis ...

s dominate, with ''Calanus glacialis

''Calanus glacialis'' is an Arctic copepod found in the north-western Atlantic Ocean, adjoining waters, and the northwestern Pacific and its nearby waters. It ranges from sea level to in depth. Females generally range from about in length, an ...

'' and ''Calanus hyperboreus

''Calanus hyperboreus'' is a copepod found in the Arctic and northern Atlantic. It occurs from the surface to depths of .

Description

The size of ''C. hyperboreus'' varies with its geography; individuals located in more temperate waters usually ...

'' constituting the greater portion of the biomass. On the sea bottom there are 34 species of macroalgae

Seaweed, or macroalgae, refers to thousands of species of macroscopic, multicellular, marine algae. The term includes some types of ''Rhodophyta'' (red), ''Phaeophyta'' (brown) and ''Chlorophyta'' (green) macroalgae. Seaweed species such as k ...

and at least 500 species of macrofauna

Fauna is all of the animal life present in a particular region or time. The corresponding term for plants is ''flora'', and for fungi, it is ''funga''. Flora, fauna, funga and other forms of life are collectively referred to as '' biota''. Zool ...

. Most common are crustaceans

Crustaceans (Crustacea, ) form a large, diverse arthropod taxon which includes such animals as decapods, seed shrimp, branchiopods, fish lice, krill, remipedes, isopods, barnacles, copepods, amphipods and mantis shrimp. The crustacean group ...

such as amphipod