Frank Whittle on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Air Commodore Sir Frank Whittle, (1 June 1907 – 8 August 1996) was an English engineer, inventor and

Whittle was born in a

Whittle was born in a

Retrieved: 18 July 2008 When he was nine years old, the family moved to the nearby town of Royal Leamington Spa where his father, a highly inventive practical engineer and mechanic,Details from the Sir Frank Whittle Jet Heritage Centre display at the

Sir Frank Whittle

'',

, ''The Sir Frank Whittle Commemorative Trust'' As Whittle was still a full-time RAF officer and currently at Cambridge, he was given the title "Honorary Chief Engineer and Technical Consultant". Needing special permission to work outside the RAF, he was placed on the Special Duty List and allowed to work on the design as long as it was for no more than six hours a week. However he was allowed to continue at Cambridge for a year doing post-graduate work which gave him time to work on the turbojet. The Air Ministry still saw little immediate value in the effort (they regarded it as long-range research), and having no production facilities of its own, Power Jets entered into an agreement with steam turbine specialists British Thomson-Houston (BTH) to build an experimental engine facility at a BTH factory in

These delays and the lack of funding slowed the project. In Germany,

These delays and the lack of funding slowed the project. In Germany,

In mid-1941, relations between Power Jets and Rover had continued to deteriorate. Rover had established a version of Power Jet's set-up at Waterloo Mill, associated with their

In mid-1941, relations between Power Jets and Rover had continued to deteriorate. Rover had established a version of Power Jet's set-up at Waterloo Mill, associated with their

Whittle wanted to improve the efficiency of the jet engine at lower speeds. According to Whittle, "I wanted to 'gear down the jet', ie to convert a low-mass high-velocity jet into a high-mass low-velocity jet. The obvious way to do this was to use an additional turbine to extract energy from the jet and use this energy to drive a low-pressure compressor or fan capable of 'breathing' far more air than the jet engine itself and forcing this additional air rearwards as a 'cold jet'. The complete system is known as a '

Whittle wanted to improve the efficiency of the jet engine at lower speeds. According to Whittle, "I wanted to 'gear down the jet', ie to convert a low-mass high-velocity jet into a high-mass low-velocity jet. The obvious way to do this was to use an additional turbine to extract energy from the jet and use this energy to drive a low-pressure compressor or fan capable of 'breathing' far more air than the jet engine itself and forcing this additional air rearwards as a 'cold jet'. The complete system is known as a '

In 1946, Whittle accepted a post as Technical Advisor on Engine Design and Production to Controller of Supplies (Air); was made a Commander of the US

In 1946, Whittle accepted a post as Technical Advisor on Engine Design and Production to Controller of Supplies (Air); was made a Commander of the US

*1907–1923: Frank Whittle

*1923–1926: Apprentice Frank Whittle

*1926–1928:

*1907–1923: Frank Whittle

*1923–1926: Apprentice Frank Whittle

*1926–1928:

* In

* In

* Whittle Parkway in Burnham is named after him.

* One of the main buildings at the Royal Air Force College Cranwell is called Whittle Hall. It houses the Officer & Aircrew Cadet Training Unit and the Air Power Studies Division of

* Whittle Parkway in Burnham is named after him.

* One of the main buildings at the Royal Air Force College Cranwell is called Whittle Hall. It houses the Officer & Aircrew Cadet Training Unit and the Air Power Studies Division of

Campbell-Smith, Duncan

(2020). ''Jet Man: The Making and Breaking of Frank Whittle, Genius of the Jet Revolution''. Head of Zeus. * * * * * *

Whittle grave marker in Westminster Abbey

Whittle Archive

News report – Memorial for University of Cambridge Student who Invented the Jet Engine

at the Royal Air Force History website

''abstract'' * ttp://archive.pepublishing.com/content/p2qq75p425787023/ Early History of the Whittle Jet Propulsion Gas Turbine by Frank Whittle''Full text of the first James Claydon lecture''

Air of Authority – Sir Frank Whittle

a 1949 ''Flight'' report of a Frank Whittle lecture to the Aero Club de France

a 1951 ''Flight'' article

Whittle Power Jet Papers

– Correspondence from the archives of Peterhouse College in

The Papers of Sir Frank Whittle

held at

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

(RAF) air officer

An air officer is an air force officer of the rank of air commodore or higher. Such officers may be termed "officers of air rank". While the term originated in the Royal Air Force, air officers are also to be found in many Commonwealth nations ...

. He is credited with inventing the turbojet

The turbojet is an airbreathing jet engine which is typically used in aircraft. It consists of a gas turbine with a propelling nozzle. The gas turbine has an air inlet which includes inlet guide vanes, a compressor, a combustion chamber, and ...

engine. A patent was submitted by Maxime Guillaume In aerospace, Maxime Guillaume (born 1888) was an agricultural engineer who filed a French patent for a turbojet engine in 1921.

The first patent for using a gas turbine to power an aircraft was filed in 1921 by Guillaume. ," French patent no. 534 ...

in 1921 for a similar invention which was technically unfeasible at the time. Whittle's jet engine

A jet engine is a type of reaction engine discharging a fast-moving jet of heated gas (usually air) that generates thrust by jet propulsion. While this broad definition can include rocket, Pump-jet, water jet, and hybrid propulsion, the term ...

s were developed some years earlier than those of Germany's Hans von Ohain

Hans Joachim Pabst von Ohain (14 December 191113 March 1998) was a German physicist, engineer, and the designer of the first operational jet engine. Together with Frank Whittle he is called the "father of the jet engine". His first test unit ran ...

, who designed the first-to-fly (but never operational) turbojet engine.

Whittle demonstrated an aptitude for engineering and an interest in flying from an early age. At first he was turned down by the RAF but, determined to join the force, he overcame his physical limitations and was accepted and sent to No. 2 School of Technical Training to join No 1 Squadron of Cranwell Aircraft Apprentices. He was taught the theory of aircraft engines and gained practical experience in the engineering workshops. His academic and practical abilities as an Aircraft Apprentice earned him a place on the officer training course at Cranwell

Cranwell is a village in the North Kesteven district of Lincolnshire, England. It is part of the civil parish of Cranwell and Byard's Leap and is situated approximately north-west from Sleaford and south-east from the city and county town o ...

. He excelled in his studies and became an accomplished pilot. While writing his thesis he formulated the fundamental concepts that led to the creation of the turbojet engine, taking out a patent on his design in 1930. His performance on an officers' engineering course earned him a place on a further course at Peterhouse

Peterhouse is the oldest constituent college of the University of Cambridge in England, founded in 1284 by Hugh de Balsham, Bishop of Ely. Today, Peterhouse has 254 undergraduates, 116 full-time graduate students and 54 fellows. It is quite o ...

, Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

, where he graduated with a First.

Without Air Ministry

The Air Ministry was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom with the responsibility of managing the affairs of the Royal Air Force, that existed from 1918 to 1964. It was under the political authority of the Secretary of State ...

support, he and two retired RAF servicemen formed Power Jets

Power Jets was a British company set up by Frank Whittle for the purpose of designing and manufacturing jet engines. The company was nationalised in 1944, and evolved into the National Gas Turbine Establishment.

History

Founded on 27 Januar ...

Ltd to build his engine with assistance from the firm of British Thomson-Houston. Despite limited funding, a prototype was created, which first ran in 1937. Official interest was forthcoming following this success, with contracts being placed to develop further engines, but the continuing stress seriously affected Whittle's health, eventually resulting in a nervous breakdown in 1940. In 1944 when Power Jets was nationalised he again suffered a nervous breakdown, and resigned from the board in 1946.

In 1948, Whittle retired from the RAF and received a knighthood

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the Gr ...

. He joined BOAC

British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) was the British state-owned airline created in 1939 by the merger of Imperial Airways and British Airways Ltd. It continued operating overseas services throughout World War II. After the passi ...

as a technical advisor before working as an engineering specialist with Shell

Shell may refer to:

Architecture and design

* Shell (structure), a thin structure

** Concrete shell, a thin shell of concrete, usually with no interior columns or exterior buttresses

** Thin-shell structure

Science Biology

* Seashell, a hard o ...

, followed by a position with Bristol Aero Engines

The Bristol Aeroplane Company, originally the British and Colonial Aeroplane Company, was both one of the first and one of the most important British aviation companies, designing and manufacturing both airframes and aircraft engines. Notable a ...

. After emigrating to the U.S. in 1976 he accepted the position of NAVAIR Research Professor at the United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy ...

from 1977 to 1979. In August 1996, Whittle died of lung cancer at his home in Columbia, Maryland. In 2002, Whittle was ranked number 42 in the BBC poll of the 100 Greatest Britons.

Early life

terraced house

In architecture and city planning, a terrace or terraced house ( UK) or townhouse ( US) is a form of medium-density housing that originated in Europe in the 16th century, whereby a row of attached dwellings share side walls. In the United State ...

in Newcombe Road, Earlsdon

Earlsdon is a residential suburb and electoral ward of Coventry, England. It lies approximately one mile to the southwest of Coventry City Centre. It is the birthplace of aviation pioneer Frank Whittle.

Amenities

Most shops and restaurants are ...

, Coventry, England, on 1 June 1907, the eldest son of Moses Whittle and Sara Alice Garlick.Whittle's biography on the RAF history website p. 1Retrieved: 18 July 2008 When he was nine years old, the family moved to the nearby town of Royal Leamington Spa where his father, a highly inventive practical engineer and mechanic,Details from the Sir Frank Whittle Jet Heritage Centre display at the

Midland Air Museum

The Midland Air Museum (MAM) is situated just outside the village of Baginton in Warwickshire, England, and is adjacent to Coventry Airport. The museum includes the ''Sir Frank Whittle Jet Heritage Centre'' (named after the local aviation pionee ...

purchased the Leamington Valve and Piston Ring Company, which comprised a few lathes and other tools and a single-cylinder gas engine

A gas engine is an internal combustion engine that runs on a gaseous fuel, such as coal gas, producer gas, biogas, landfill gas or natural gas. In the United Kingdom, the term is unambiguous. In the United States, due to the widespread use of ...

, on which Whittle became an expert.Sir Frank Whittle

'',

The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was fo ...

, Obituaries, 10 August 1996 Whittle developed a rebellious and adventurous streak, together with an early interest in aviation.

After two years attending Milverton School, Whittle won a scholarship to a secondary school which in due course became Leamington College for Boys

North Leamington School (NLS) is a mixed, non-selective, comprehensive school for students aged 11 to 18 years located at the northeastern edge of Leamington Spa, Warwickshire, England. It is rated as a ''good'' school by Ofsted, and has 6.7 ...

, but when his father's business faltered there was not enough money to keep him there. He quickly developed practical engineering skills while helping in his father's workshop, and being an enthusiastic reader spent much of his spare time in the Leamington reference library, reading about astronomy, engineering, turbines, and the theory of flight. At the age of 15, determined to be a pilot, Whittle applied to join the RAF

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

.

Entering the RAF

In January 1923, having passed the RAF entrance examination with a high mark, Whittle reported to RAF Halton as anAircraft Apprentice

An aircraft is a vehicle that is able to fly by gaining support from the air. It counters the force of gravity by using either static lift or by using the dynamic lift of an airfoil, or in a few cases the downward thrust from jet engines. ...

. He lasted only two days: just five feet tall and with a small chest measurement, he failed the medical. He then put himself through a vigorous training programme and special diet devised by a physical training instructor at Halton to build up his physique, only to fail again six months later, when he was told that he could not be given a second chance, despite having added three inches to his height and chest. Undeterred, he applied again under an assumed name and presented himself as a candidate at the No 2 School of Technical Training RAF Cranwell

Royal Air Force Cranwell or more simply RAF Cranwell is a Royal Air Force station in Lincolnshire, England, close to the village of Cranwell, near Sleaford. Among other functions, it is home to the Royal Air Force College (RAFC), which trai ...

. This time he passed the physical and, in September that year, 364365 Boy Whittle, F, started his three-year training as an aircraft mechanic in No. 1 Squadron of No. 4 Apprentices Wing, RAF Cranwell, because RAF Halton No. 1 School of Technical Training was unable to accommodate all the aircraft apprentices at that time.

Whittle hated the strict discipline imposed on apprentices and, convinced there was no hope of ever becoming a pilot, he at one time seriously considered deserting. However, throughout his early days as an aircraft apprentice (and at the Royal Air Force College Cranwell

The Royal Air Force College (RAFC) is the Royal Air Force military academy which provides initial training to all RAF personnel who are preparing to become commissioned officers. The College also provides initial training to aircrew cadets and ...

), he maintained his interest in model aircraft and joined the Model Aircraft Society, where he built working replicas. The quality of these attracted the eye of the Apprentice Wing commanding officer, who noted that Whittle was also a mathematical genius. He was so impressed that in 1926 he recommended Whittle for officer training at RAF College Cranwell.

For Whittle, this was the chance of a lifetime, not only to enter the commissioned ranks but also because the training included flying lessons on the Avro 504

The Avro 504 was a First World War biplane aircraft made by the Avro aircraft company and under licence by others. Production during the war totalled 8,970 and continued for almost 20 years, making it the most-produced aircraft of any kind tha ...

. While at Cranwell he lodged in a bungalow at Dorrington. Being an ex-apprentice amongst a majority of ex-public school

Public school may refer to:

* State school (known as a public school in many countries), a no-fee school, publicly funded and operated by the government

* Public school (United Kingdom), certain elite fee-charging independent schools in England an ...

boys, life as an officer cadet was not easy for him, but he nevertheless excelled in the courses and went solo in 1927 after only 13.5 hours instruction, quickly progressing to the Bristol Fighter and gaining a reputation for daredevil low flying and aerobatics.

A requirement of the course was that each student had to produce a thesis for graduation: Whittle decided to write his on potential aircraft design developments, notably flight at high altitudes and speeds over 500 mph (800 km/h). In ''Future Developments in Aircraft Design'' he showed that incremental improvements in existing propeller engines were unlikely to make such flight routine. Instead he described what is today referred to as a motorjet

A motorjet is a rudimentary type of jet engine which is sometimes referred to as ''thermojet'', a term now commonly used to describe a particular and completely unrelated pulsejet design.

Design

At the heart the motorjet is an ordinary pis ...

; a motor using a conventional piston engine to provide compressed air to a combustion chamber whose exhaust was used directly for thrust – essentially an afterburner

An afterburner (or reheat in British English) is an additional combustion component used on some jet engines, mostly those on military supersonic aircraft. Its purpose is to increase thrust, usually for supersonic flight, takeoff, and co ...

attached to a propeller engine. The idea was not new and had been talked about for some time in the industry, but Whittle's aim was to demonstrate that at increased altitudes the lower outside air density would increase the design's efficiency. For long-range flight, using an Atlantic-crossing mailplane as his example, the engine would spend most of its time at high altitude and thus could outperform a conventional powerplant. According to Whittle, "...I came to the general conclusion that if very high speeds were to be combined with long range, it would be necessary to fly at very great height, where the low air density would greatly reduce resistance in proportion to speed."

Of the few apprentices accepted into the Royal Air Force College, Whittle graduated in 1928 at the age of 21 and was commissioned as a pilot officer

Pilot officer (Plt Off officially in the RAF; in the RAAF and RNZAF; formerly P/O in all services, and still often used in the RAF) is the lowest commissioned rank in the Royal Air Force and the air forces of many other Commonwealth countri ...

in July. He ranked second in his class in academics, won the Andy Fellowes Memorial Prize for Aeronautical Sciences for his thesis, and was described as an "exceptional to above average" pilot. However, his flight logbook also showed numerous red ink warnings about showboating and overconfidence, and because of dangerous flying in an Armstrong Whitworth Siskin

The Armstrong Whitworth Siskin was a biplane single-seat fighter aircraft developed and produced by the British aircraft manufacturer Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft. It was also the first all-metal fighter to be operated by the Royal Air Force (RA ...

he was disqualified from the end of term flying contest.

Development of the turbojet engine

Whittle continued working on the motorjet principle after his thesis work but eventually abandoned it when further calculations showed it would weigh as much as a conventional engine of the same thrust. Pondering the problem he thought: "Why not substitute a turbine for the piston engine?" Instead of using a piston engine to provide the compressed air for the burner, a turbine could be used to extract some power from the exhaust and drive a similar compressor to those used for superchargers. The remaining exhaust thrust would power the aircraft. On 27 August 1928, Pilot Officer Whittle joined No. 111 Squadron, Hornchurch, flying Siskin IIIs. His continuing reputation for low flying and aerobatics provoked a public complaint that almost led to his being court-martialled. Within a year he was posted toCentral Flying School

The Central Flying School (CFS) is the Royal Air Force's primary institution for the training of military flying instructors. Established in 1912 at the Upavon Aerodrome, it is the longest existing flying training school. The school was based at ...

, at Wittering, for a flying instructor's course. He became a popular and gifted instructor, and was selected as one of the entrants in a competition to select a team to perform the "crazy flying" routine in the 1930 Royal Air Force Air Display at RAF Hendon

Hendon is an urban area in the Borough of Barnet, North-West London northwest of Charing Cross. Hendon was an ancient manor and parish in the county of Middlesex and a former borough, the Municipal Borough of Hendon; it has been part of Grea ...

. He destroyed two aircraft in accidents during rehearsals but remained unscathed on both occasions. After the second incident an enraged Flight Lieutenant Harold W. Raeburn said furiously, "Why don't you take all my bloody aeroplanes, make a heap of them in the middle of the aerodrome and set fire to them – it's quicker!"

Whittle showed his engine concept around the base, where it attracted the attention of Flying Officer Pat Johnson, formerly a patent examiner. Johnson, in turn, took the concept to the commanding officer of the base. This set in motion a chain of events that almost led to the engines being produced much sooner than actually occurred.

Earlier, in July 1926, A. A. Griffith had published a paper on compressors and turbines, which he had been studying at the Royal Aircraft Establishment

The Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) was a British research establishment, known by several different names during its history, that eventually came under the aegis of the Ministry of Defence (United Kingdom), UK Ministry of Defence (MoD), bef ...

(RAE). He showed that such designs up to this point had been flying "stalled", and that by giving the compressor blades an aerofoil-shaped cross-section their efficiency could be dramatically improved. The paper went on to describe how the increased efficiency of these sorts of compressors and turbines would allow a jet engine to be produced, although he felt the idea was impractical, and instead suggested using the power as a turboprop

A turboprop is a turbine engine that drives an aircraft propeller.

A turboprop consists of an intake, reduction gearbox, compressor, combustor, turbine, and a propelling nozzle. Air enters the intake and is compressed by the compressor. ...

. At the time most superchargers used a centrifugal compressor

Centrifugal compressors, sometimes called impeller compressors or radial compressors, are a sub-class of dynamic axisymmetric work-absorbing turbomachinery.

They achieve pressure rise by adding energy to the continuous flow of fluid through t ...

, so there was limited interest in the paper.

Encouraged by his commanding officer, in late 1929 Whittle sent his concept to the Air Ministry

The Air Ministry was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom with the responsibility of managing the affairs of the Royal Air Force, that existed from 1918 to 1964. It was under the political authority of the Secretary of State ...

to see if it would be of any interest to them. With little knowledge of the topic they turned to the only other person who had written on the subject and passed the paper on to Griffith. Griffith appears to have been convinced that Whittle's "simple" design could never achieve the sort of efficiencies needed for a practical engine. After pointing out an error in one of Whittle's calculations, he went on to comment that the centrifugal design would be too large for aircraft use and that using the jet directly for power would be rather inefficient. The RAF returned his comment to Whittle, referring to the design as being "impracticable".

Pat Johnson remained convinced of the validity of the idea, and had Whittle patent the idea in January 1930. Since the RAF was not interested in the concept they did not declare it secret, meaning that Whittle was able to retain the rights to the idea, which would have otherwise been their property. Johnson arranged a meeting with British Thomson-Houston (BTH), whose chief turbine engineer seemed to agree with the basic idea. However, BTH did not want to spend the £60,000 it would cost to develop it, and this potential brush with early success went no further.

In January 1930, Whittle was promoted to flying officer. In Coventry, on 24 May 1930, Whittle married his fiancée, Dorothy Mary Lee, with whom he later had two sons, David and Ian. Then, in 1931, he was posted to the Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment

The Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment (MAEE) was a British military research and test organisation. It was originally formed as the Marine Aircraft Experimental Station in October 1918 at RAF Isle of Grain, a former Royal Naval Air Serv ...

at Felixstowe

Felixstowe ( ) is a port town in Suffolk, England. The estimated population in 2017 was 24,521. The Port of Felixstowe is the largest Containerization, container port in the United Kingdom. Felixstowe is approximately 116km (72 miles) northea ...

as an armament officer and test pilot

A test pilot is an aircraft pilot with additional training to fly and evaluate experimental, newly produced and modified aircraft with specific maneuvers, known as flight test techniques.Stinton, Darrol. ''Flying Qualities and Flight Testing ...

of seaplanes, where he continued to publicise his idea. This posting came as a surprise for he had never previously flown a seaplane, but he nevertheless increased his reputation as a pilot by flying some 20 different types of floatplanes, flying boats, and amphibians.

While at Felixstowe, Whittle met with the firm of Armstrong Siddeley

Armstrong Siddeley was a British engineering group that operated during the first half of the 20th century. It was formed in 1919 and is best known for the production of luxury vehicles and aircraft engines.

The company was created following t ...

, and their technical advisor W.S. Farren. The firm rejected Whittle's proposal, doubting material was available to sustain the required very high temperatures. Whittle's turbojet proposal required a compressor with a pressure ratio of 4:1, while the best current supercharger only had half that value. Besides publishing a paper on superchargers, Whittle wrote The Case for the Gas Turbine

A gas turbine, also called a combustion turbine, is a type of continuous flow internal combustion engine. The main parts common to all gas turbine engines form the power-producing part (known as the gas generator or core) and are, in the directio ...

. According to John Golley, "The paper contained example calculations which showed the big increase in efficiency which could be obtained with the gas turbine at great height due to the beneficial effects of low air temperature. It also contained calculations to demonstrate the degree to which range would depend on height with turbojet aircraft."

Every officer with a permanent commission was expected to take a specialist course, and as a result Whittle attended the Officers School of Engineering at RAF Henlow

RAF Henlow is a Royal Air Force station in Bedfordshire, England, equidistant from Bedford, Luton and Stevenage. It houses the RAF Centre of Aviation Medicine, the Joint Arms Control Implementation Group (JACIG), elements of Defence Equipment ...

in 1932. He obtained an aggregate of 98% in all subjects in his entrance exam, which allowed him to complete a shortened one-year course. Whittle received a Distinction in every subject, except mechanical Drawing, noting he was "A very able student. He works hard and has originality. He is suitable for experimental duties."

His performance in the course was so exceptional that in 1934 he was permitted to take a two-year engineering course as a member of Peterhouse

Peterhouse is the oldest constituent college of the University of Cambridge in England, founded in 1284 by Hugh de Balsham, Bishop of Ely. Today, Peterhouse has 254 undergraduates, 116 full-time graduate students and 54 fellows. It is quite o ...

, the oldest college of Cambridge University

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

, graduating in 1936 with a First

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

in the Mechanical Sciences Tripos

At the University of Cambridge, a Tripos (, plural 'Triposes') is any of the examinations that qualify an undergraduate for a bachelor's degree or the courses taken by a student to prepare for these. For example, an undergraduate studying mathe ...

. In February 1934, he had been promoted to the rank of flight lieutenant

Flight lieutenant is a junior commissioned rank in air forces that use the Royal Air Force (RAF) system of ranks, especially in Commonwealth countries. It has a NATO rank code of OF-2. Flight lieutenant is abbreviated as Flt Lt in the India ...

.

Power Jets Ltd

Still at Cambridge, Whittle could ill afford the £5 renewal fee for his jet engine patent when it became due in January 1935, and because the Air Ministry refused to pay it the patent was allowed to lapse. Shortly afterwards, in May, he received mail from Rolf Dudley-Williams, who had been with him at Cranwell in the 1920s and Felixstowe in 1930. Williams arranged a meeting with Whittle, himself, and another by-then-retired RAF serviceman,James Collingwood Tinling

James Collingwood Burdett Tinling (24 March 1900 – 1983) was an ex-RAF officer who joined with Rolf Dudley-Williams and Frank Whittle in 1936 to set up Power Jets Ltd, which manufactured the world's first working jet engine.

Tinling was born i ...

. The two proposed a partnership that allowed them to act on Whittle's behalf to gather public financing so that development could go ahead. Whittle thought improvements to his original idea could be patented, noting, "Its virtue lies entirely in its extremely low weight, and that it will work at heights where atmospheric density is very low." This led to three provisional specifications being filed, as the group sought to develop a jet-propelled airplane.

The agreement soon bore fruit, and in 1935, through Tinling's father, Whittle was introduced to Mogens L. Bramson, a well-known independent consulting aeronautical engineer. Bramson was initially sceptical but after studying Whittle's ideas became an enthusiastic supporter. Bramson introduced Whittle and his two associates to the investment bank O.T. Falk & Partners, where discussions took place with Lancelot Law Whyte

Lancelot Law Whyte (4 November 1896 – 14 September 1972) was a Scottish philosopher, theoretical physicist, historian of science and financier. Early life and career

Lancelot Law Whyte, the son of Dr. Alexander Whyte, was born in Edinburgh, Sco ...

and occasionally Sir Maurice Bonham-Carter. The firm had an interest in developing speculative projects that conventional banks would not touch. Whyte was impressed by the 28-year-old Whittle and his design when they met on 11 September 1935:

However O.T. Falk & Partners specified they would only invest in Whittle's engine if they had independent verification that it was feasible. They financed an independent engineering review from Bramson (The historic "Bramson Report"

), which was issued in November 1935. It was favourable and Falk then agreed to finance Whittle. With that the jet engine was finally on its way to becoming a reality.

On 27 January 1936, the principals signed the "Four Party Agreement", creating "Power Jets

Power Jets was a British company set up by Frank Whittle for the purpose of designing and manufacturing jet engines. The company was nationalised in 1944, and evolved into the National Gas Turbine Establishment.

History

Founded on 27 Januar ...

Ltd" which was incorporated in March 1936. The parties were O.T. Falk & Partners, the Air Ministry, Whittle and, together, Williams and Tinling. Falk was represented on the board of Power Jets by Whyte as chairman and Bonham-Carter as a director (with Bramson acting as alternate). Whittle, Williams and Tinling retained a 49% share of the company in exchange for Falk and Partners putting in £2,000 with the option of a further £18,000 within 18 months.POWER JETS A brief biography, ''The Sir Frank Whittle Commemorative Trust'' As Whittle was still a full-time RAF officer and currently at Cambridge, he was given the title "Honorary Chief Engineer and Technical Consultant". Needing special permission to work outside the RAF, he was placed on the Special Duty List and allowed to work on the design as long as it was for no more than six hours a week. However he was allowed to continue at Cambridge for a year doing post-graduate work which gave him time to work on the turbojet. The Air Ministry still saw little immediate value in the effort (they regarded it as long-range research), and having no production facilities of its own, Power Jets entered into an agreement with steam turbine specialists British Thomson-Houston (BTH) to build an experimental engine facility at a BTH factory in

Rugby, Warwickshire

Rugby is a market town in eastern Warwickshire, England, close to the River Avon. In the 2021 census its population was 78,125, making it the second-largest town in Warwickshire. It is the main settlement within the larger Borough of Rugby whi ...

. Work progressed quickly, and by the end of the year 1936 the prototype detail design was finalised and parts for it were well on their way to being completed, all within the original £2,000 budget. However, by 1936, Germany had also started working on jet engines ( Herbert A. Wagner at Junkers and Hans von Ohain

Hans Joachim Pabst von Ohain (14 December 191113 March 1998) was a German physicist, engineer, and the designer of the first operational jet engine. Together with Frank Whittle he is called the "father of the jet engine". His first test unit ran ...

at Heinkel) and, although they too had difficulty overcoming conservatism, the German Ministry of Aviation (Reichsluftfahrtministerium) was more supportive than their British counterpart. Von Ohain applied for a patent for a turbojet engine in 1935 but having earlier reviewed and critiqued Whittle's patents, had to narrow the scope of his own filing. In Spain, air-force pilot and engineer Virgilio Leret Ruiz

Virgilio Leret Ruiz (23 August 1902 – 18 July 1936) was a Spanish air force commander, writer and pioneer of aeronautical engineering with a patented jet-engine design. He is believed to be the first officer executed in the Spanish Civil War af ...

had been granted a patent for a jet engine in March 1935, and Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

president Manuel Azaña

Manuel Azaña Díaz (; 10 January 1880 – 3 November 1940) was a Spanish politician who served as Prime Minister of the Second Spanish Republic (1931–1933 and 1936), organizer of the Popular Front in 1935 and the last President of the Repu ...

arranged for initial construction at the Hispano-Suiza aircraft factory in Madrid in 1936, but Leret was executed months later by Francoist

Francoist Spain ( es, España franquista), or the Francoist dictatorship (), was the period of Spanish history between 1939 and 1975, when Francisco Franco ruled Spain after the Spanish Civil War with the title . After his death in 1975, Spai ...

Moroccan troops after commanding the defence of his seaplane base near Melilla

Melilla ( , ; ; rif, Mřič ; ar, مليلية ) is an autonomous city of Spain located in north Africa. It lies on the eastern side of the Cape Three Forks, bordering Morocco and facing the Mediterranean Sea. It has an area of . It was par ...

at the onset of the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

. His plans were hidden from the Francoists and secretly handed to the British embassy in Madrid a few years later when his wife, Carlota O'Neill

Carlota Alejandra Regina Micaela O'Neill y de Lamo (27 March 1905 – 20 June 2000) was a Spanish- Mexican writer and journalist. Her husband, Captain Virgilio Leret Ruiz, was executed after opposing the July 1936 military uprising in Melilla whi ...

, was released from prison.

Despite lengthy delays in their own programme, the Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

beat the British efforts into the air by nine months. A lack of cobalt

Cobalt is a chemical element with the symbol Co and atomic number 27. As with nickel, cobalt is found in the Earth's crust only in a chemically combined form, save for small deposits found in alloys of natural meteoric iron. The free element, pr ...

for high-temperature steel alloys meant the German designs were always at risk of overheating and damaging their turbines. The low-grade alloy production versions of the Junkers Jumo 004, designed by Dr. Anselm Franz Anselm Franz (January 20, 1900—November 18, 1994) was a pioneering Austrian jet engine engineer known for the development of the Jumo 004, the world's first mass-produced turbojet engine by Nazi Germany during World War II, and his work on tur ...

and which powered the Messerschmitt Me 262

The Messerschmitt Me 262, nicknamed ''Schwalbe'' (German: "Swallow") in fighter versions, or ''Sturmvogel'' (German: "Storm Bird") in fighter-bomber versions, is a fighter aircraft and fighter-bomber that was designed and produced by the Germa ...

would typically last only 10–25 hours (longer with an experienced pilot) before burning out; if it was accelerated too quickly, the compressor would stall and power was immediately lost, and sometimes it exploded on their first startup. Over 200 German pilots were killed during training. Nevertheless, the Me 262 could fly far faster than allied planes and had very effective firepower. Although Me 262s were introduced late in the war they shot down 542 or more allied planes and in one allied bombing raid downed 32 of the 36 Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress

The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress is a four-engined heavy bomber developed in the 1930s for the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC). Relatively fast and high-flying for a bomber of its era, the B-17 was used primarily in the European Theater ...

es.

Financial difficulty

Earlier, in January, when the company formed,Henry Tizard

Sir Henry Thomas Tizard (23 August 1885 – 9 October 1959) was an English chemist, inventor and Rector of Imperial College, who developed the modern "octane rating" used to classify petrol, helped develop radar in World War II, and led the fir ...

, the rector of Imperial College London

Imperial College London (legally Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine) is a public research university in London, United Kingdom. Its history began with Prince Albert, consort of Queen Victoria, who developed his vision for a cu ...

and chairman of the Aeronautical Research Committee

The Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (ACA) was a UK agency founded on 30 April 1909, to undertake, promote, and institutionalize aeronautical research. In 1919 it was renamed the Aeronautical Research Committee, later becoming the Aeronautical ...

(ARC), had prompted the Air Ministry's Director of Scientific Research to ask for a write-up of the design. The report was once again passed on to Griffith for comment, but was not received back until March 1937 by which point Whittle's design was well along. Griffith had already started construction of his own turbine engine design and, perhaps to avoid tainting his own efforts, he returned a somewhat more positive review. However, he remained highly critical of some features, notably the use of jet thrust. The Engine Sub-Committee of ARC studied Griffith's report, and decided to fund his effort instead. Given this astonishing display of official indifference, Falk and Partners gave notice that they could not provide funding beyond £5,000.

Nevertheless, the team pressed ahead, and the Power Jets WU

The Power Jets WU (Whittle Unit) was a series of three very different experimental jet engines produced and tested by Frank Whittle and his small team in the late 1930s.

Design and development

The WU "First Model", also known by Whittle as th ...

(Whittle Unit, or W.U.) engine began test runs on 12 April 1937. Initially, the W.U. showed an alarming tendency to race out of control, due to issues with the fuel injection, before stable speeds were reached. However, by August, Whittle acknowledged a major reconstruction effort was needed to solve the combustion problem and compressor efficiency.

On 9 July, Falk & Partners gave the company an emergency loan of £250. On 27 July, Falk's option expired, but they agreed to continue financing Power Jets by loan. Also in July, Whittle's post-graduate stay at Cambridge was over, but then he was placed on the Special Duty List so he could work full-time on the engine. On 1 November, Williams, Tinling and Whittle took control of Power Jets. Whittle was promoted to squadron leader

Squadron leader (Sqn Ldr in the RAF ; SQNLDR in the RAAF and RNZAF; formerly sometimes S/L in all services) is a commissioned rank in the Royal Air Force and the air forces of many countries which have historical British influence. It is als ...

in December. Tizard pronounced it "streaks ahead" of any other advanced engine he had seen, and managed to interest the Air Ministry

The Air Ministry was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom with the responsibility of managing the affairs of the Royal Air Force, that existed from 1918 to 1964. It was under the political authority of the Secretary of State ...

enough to fund development with a contract for £5,000 to develop a flyable version. However, it was not until March 1938 that a contract was signed, when Power Jets became subject to the Official Secrets Act, limiting the ability to raise additional funds. In January 1938, BTH invested £2,500.

In December 1937, Victor Crompton became Power Jets first employee, as an assistant to Whittle. Because of the dangerous nature of the work being carried out, development was moved largely from Rugby to BTH's lightly used Ladywood foundry at nearby Lutterworth

Lutterworth is a market town and civil parish in the Harborough district of Leicestershire, England. The town is located in southern Leicestershire, close to the borders with Warwickshire and Northamptonshire. It is located north of Rugby, ...

in Leicestershire in 1938. Tests with a reconstructed W.U. engine commenced on 16 April 1938, and proceeded until a catastrophic failure of the turbine on 6 May. Yet, the engine ran for 1 hour and 45 minutes, and generated a thrust

Thrust is a reaction force described quantitatively by Newton's third law. When a system expels or accelerates mass in one direction, the accelerated mass will cause a force of equal magnitude but opposite direction to be applied to that syst ...

of at 13,000 rpm

Revolutions per minute (abbreviated rpm, RPM, rev/min, r/min, or with the notation min−1) is a unit of rotational speed or rotational frequency for rotating machines.

Standards

ISO 80000-3:2019 defines a unit of rotation as the dimensionl ...

. Another W.U. engine reconstruction was started on 30 May 1938, but using ten combustion chambers to match the ten compressor discharge ducts. Avoiding a single large combustion chamber made the engine lighter and more compact. Tests commenced with this third W.U. on 26 October 1938.

These delays and the lack of funding slowed the project. In Germany,

These delays and the lack of funding slowed the project. In Germany, Hans von Ohain

Hans Joachim Pabst von Ohain (14 December 191113 March 1998) was a German physicist, engineer, and the designer of the first operational jet engine. Together with Frank Whittle he is called the "father of the jet engine". His first test unit ran ...

had filed for a patent in 1935, which in 1939, led to the world's first flyable jet aircraft

A jet aircraft (or simply jet) is an aircraft (nearly always a fixed-wing aircraft) propelled by jet engines.

Whereas the engines in propeller-powered aircraft generally achieve their maximum efficiency at much lower speeds and altitudes, je ...

, the Heinkel He 178

The Heinkel He 178 was an experimental aircraft designed and produced by the German aircraft manufacturer Heinkel. It was the world's first aircraft to fly using the thrust from a turbojet engine.

The He 178 was developed to test the jet propu ...

, powered by the Heinkel HeS 3

The Heinkel HeS 3 (HeS - ''Heinkel Strahltriebwerke'') was the world's first operational jet engine to power an aircraft. Designed by Hans von Ohain while working at Heinkel, the engine first flew as the primary power of the Heinkel He 178, pilote ...

. There is little doubt that Whittle's efforts would have been at the same level or even more advanced had the Air Ministry taken a greater interest in the design. When war

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

broke out in September 1939, Power Jets had a payroll of only 10 and Griffith's operations at the RAE and Metropolitan-Vickers

Metropolitan-Vickers, Metrovick, or Metrovicks, was a British heavy electrical engineering company of the early-to-mid 20th century formerly known as British Westinghouse. Highly diversified, it was particularly well known for its industrial el ...

were similarly small.

Whittle's smoking increased to three packs a day and he suffered from various stress-related ailments such as frequent severe headaches, indigestion, insomnia, anxiety, eczema

Dermatitis is inflammation of the skin, typically characterized by itchiness, redness and a rash. In cases of short duration, there may be small blisters, while in long-term cases the skin may become thickened. The area of skin involved can ...

and heart palpitations, while his weight dropped to nine stone (126 lb / 57 kg). To keep to his 16-hour workdays, he sniffed Benzedrine

Amphetamine (contracted from alpha- methylphenethylamine) is a strong central nervous system (CNS) stimulant that is used in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), narcolepsy, and obesity. It is also commonly used a ...

during the day and then took tranquillizers and sleeping pills at night to offset the effects and allow him to sleep. He admitted later he had become addicted to benzedrine. Over this period he became irritable and developed an "explosive" temper.

Changing fortunes

On 30 June 1939, Power Jets could barely afford to keep the lights on when yet another visit was made by Air Ministry personnel. This time Whittle was able to run the third reconstructed W.U. at 16,000 rpm for 20 minutes without any difficulty. One of the members of the team was the Director of Scientific Research, David Randall Pye, who walked out of the demonstration utterly convinced of the importance of the project. The Ministry agreed to buy the W.U. and then loan it back to them, injecting cash, and placed an order for a flyable version of the engine, referred to as the Power Jets W.1 and Power Jets W.2. By then, the Ministry had a tentative contract with theGloster Aircraft Company

The Gloster Aircraft Company was a British aircraft manufacturer from 1917 to 1963.

Founded as the Gloucestershire Aircraft Company Limited during the First World War, with the aircraft construction activities of H H Martyn & Co Ltd of Chelte ...

for a simple aircraft specifically to flight-test the W.1, the single-engine Gloster E.28/39.

Whittle had already studied the problem of turning the massive W.U. into a flyable design, with what he described as very optimistic targets, to power a little aeroplane weighing 2,000 lb with a static thrust of 1,389 lb. The designed maximum thrust for the W.1 was , while that for the W.2, was The W.2 was to be flown in the twin-engine Gloster Meteor

The Gloster Meteor was the first British jet fighter and the Allies of World War II, Allies' only jet aircraft to engage in combat operations during the Second World War. The Meteor's development was heavily reliant on its ground-breaking turb ...

fighter, designated F.9/40, but the engine was replaced with the W.2B, having

a designed static thrust of . An experimental version of the W.1, designated W.1X, was used as a mock-up for the E.28 installation. A second E.28 was powered by the W.1A, that incorporated W.2 features such as air cooling of the turbine and a different compressor intake. On 26 March 1940, the jet engine was listed as a potential war winner by Air Marshal Tedder Tedder is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*Arthur Tedder, 1st Baron Tedder, British air marshal

* Constant Tedder, former Chief Executive Officer of Jagex Games Studio

* Ernest Tedder (1915–1972), English cricketer

*Henry Ric ...

, and given the associated priority.

Power Jets also spent some time in May 1940 drawing up the W.2Y, a similar design with a "straight-through" airflow that resulted in a longer engine and, more critically, a longer driveshaft but having a somewhat simpler layout. To reduce the weight of the driveshaft as much as possible, the W.2Y used a large diameter, thin-walled, shaft almost as large as the turbine disc, "necked down" at either end where it connected to the turbine and compressor.

In April, the Air Ministry issued contracts for W.2 production lines with a capacity of up to 3,000 engines a month in 1942, asking BTH, Vauxhall

Vauxhall ( ) is a district in South West London, part of the London Borough of Lambeth, England. Vauxhall was part of Surrey until 1889 when the County of London was created. Named after a medieval manor, "Fox Hall", it became well known for ...

and the Rover Company

The Rover Company Limited was a British car manufacturing company that operated from its base in Solihull in Warwickshire. Its lasting reputation for quality and performance was such that its first postwar model reviewed by '' Road & Track'' i ...

to join. However, the contract was eventually taken up by Rover only. In June, Whittle received a promotion to wing commander

Wing commander (Wg Cdr in the RAF, the IAF, and the PAF, WGCDR in the RNZAF and RAAF, formerly sometimes W/C in all services) is a senior commissioned rank in the British Royal Air Force and air forces of many countries which have historical ...

.

On 19 July 1940, Power Jets abandoned effort to vaporize fuel, and adopted the controlled atomising burner for the combustion chamber, developed by Isaac Lubbock of Asiatic Petroleum Company Asiatic Petroleum Company (APC) was a joint venture between the Shell and Royal Dutch oil companies founded in 1903. It operated in Asia in the early twentieth century. The corporate headquarters were on The Bund in Shanghai, China. The division ...

. In the words of Whittle, "the introduction of the Shell system may be said to mark the point where combustion ceased to be an obstacle to development." The size of Power Jets also increased with the WWII

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

effort, increasing from 25 employees in January 1940 to 70 in September 1940.

Rover

Meanwhile, work continued with the W.U., which eventually went through nine rebuilds in an attempt to solve the combustion problems that had dominated the testing. On 9 October the W.U. ran once again, this time equipped with Lubbock or "Shell" atomising-burner combustion chambers. Combustion problems ceased to be an obstacle to development of the engine although intensive development was started on all features of the new combustion chambers. By this point it was clear that Gloster's first airframe would be ready long before Rover could deliver an engine. Unwilling to wait, Whittle cobbled together an engine from spare parts, creating the W.1X ("X" standing for "experimental") which ran for the first time on 14 December 1940. Shortly afterwards an application for a US patent was made by Power Jets for an "Aircraft propulsion system and power unit" The W.1X engine powered the E.28/39 for taxi testing on 7 April 1941 near the factory in Gloucester, where it took to the air for two or three short hops of several hundred yards at about six feet from the ground. The definitive W.1 of 850lbf

The pound of force or pound-force (symbol: lbf, sometimes lbf,) is a unit of force used in some systems of measurement, including English Engineering units and the foot–pound–second system.

Pound-force should not be confused with pound-m ...

(3.8 kN) thrust ran on 12 April 1941, and on 15 May the W.1-powered E.28/39 took off from Cranwell at 7:40 pm, flying for 17 minutes and reaching a maximum speed of around 340 mph (545 km/h). At the end of the flight, Pat Johnson, who had encouraged Whittle for so long said to him, "Frank, it flies." Whittle replied, "Well, that's what it was bloody well designed to do, wasn't it?"

Within days the aircraft was reaching 370 mph (600 km/h) at 25,000 feet (7,600 m), exceeding the performance of the contemporary Spitfires

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft used by the Royal Air Force and other Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. Many variants of the Spitfire were built, from the Mk 1 to the Rolls-Royce Grif ...

. Success of the design was now evident, and in 1941, Rolls-Royce, Hawker Siddeley, the Bristol Aeroplane Company, and de Havilland

The de Havilland Aircraft Company Limited () was a British aviation manufacturer established in late 1920 by Geoffrey de Havilland at Stag Lane Aerodrome Edgware on the outskirts of north London. Operations were later moved to Hatfield in H ...

became interested in gas turbine aircraft propulsion.

The stress on Whittle was expressed in a 27 May 1941 letter to Henry Tizard

Sir Henry Thomas Tizard (23 August 1885 – 9 October 1959) was an English chemist, inventor and Rector of Imperial College, who developed the modern "octane rating" used to classify petrol, helped develop radar in World War II, and led the fir ...

:

Barnoldswick

Barnoldswick (pronounced ) is a market town and civil parish in the Borough of Pendle, Lancashire, England. It is within the boundaries of the historic West Riding of Yorkshire, Barnoldswick and the surrounding areas of West Craven have be ...

factory, near Clitheroe

Clitheroe () is a town and civil parish in the Borough of Ribble Valley, Lancashire, England; it is located north-west of Manchester. It is near the Forest of Bowland and is often used as a base for tourists visiting the area. In 2018, the Cl ...

. Rover was working on an alternative to Whittle's "reverse-flow" combustion chambers, by developing a "straight-through" combustion chamber and turbine wheel. Rover referred to the engine as the B.26, sanctioned by the Directorate of Engine Development, but kept secret until April 1942, from Power Jets, the Controller of Research and Development, and the Director of Scientific Research.

Rolls-Royce

Earlier, in January 1940, Whittle had met DrStanley Hooker

Sir Stanley George Hooker, CBE, FRS, DPhil, BSc, FRAeS, MIMechE, FAAAS, (30 September 1907 – 24 May 1984) was a mathematician and jet engine engineer. He was employed first at Rolls-Royce where he worked on the earliest designs such as ...

of Rolls-Royce

Rolls-Royce (always hyphenated) may refer to:

* Rolls-Royce Limited, a British manufacturer of cars and later aero engines, founded in 1906, now defunct

Automobiles

* Rolls-Royce Motor Cars, the current car manufacturing company incorporated in ...

, who in turn introduced Whittle to Rolls-Royce board member and manager of their Derby factory, Ernest Hives

Ernest Walter Hives, 1st Baron Hives (21 April 1886 – 24 April 1965), was the one-time head of the Rolls-Royce Aero Engine division and chairman of Rolls-Royce Ltd.

Hives was born in Reading, Berkshire to John and Mary Hives, living at 31 C ...

(later Lord Hives). Hooker was in charge of the supercharger division at Rolls-Royce Derby and was a specialist in fluid dynamics

In physics and engineering, fluid dynamics is a subdiscipline of fluid mechanics that describes the flow of fluids— liquids and gases. It has several subdisciplines, including ''aerodynamics'' (the study of air and other gases in motion) an ...

. He had already increased the power of the Merlin piston engine by improving its supercharger. Such a speciality was naturally suited to the aero-thermodynamics of jet engines in which the optimisation of airflow in compressor, combustion chambers, turbine and jet pipe, is fundamental. Hives agreed to supply key parts to help the project. Also, Rolls-Royce built a compressor test rig which helped Whittle solve the surging problems (unstable airflow in the compressor) on the W.2 engine.

On 10 December 1941 Whittle suffered a nervous breakdown

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness or psychiatric disorder, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. Such features may be persistent, relapsing and remitti ...

, and left work for a month. However, by the end of January 1942, Power Jets had three W.2B engines, two built by Rover. In February 1942, flight trials of the W.1A engine began in the E.28, which reached 430 mph (690 km/h) at 15,000 feet (4,600 m). On 13 March 1942, Whittle started work on a redesign of the W.2B, referred to as the W.2/500.

On 13 September 1942, W.2/500 performance tests matched predictions, showing a thrust of at full speed. In October 1941, the Ministry approved a new factory to be built outside Whetstone, Leicestershire

Whetstone is a village and civil parish in the Blaby district of Leicestershire, England and largely acts as a commuter village for Leicester, five miles to the north. The population at the 2011 census was 6,556. It is part of the Leicester ...

.

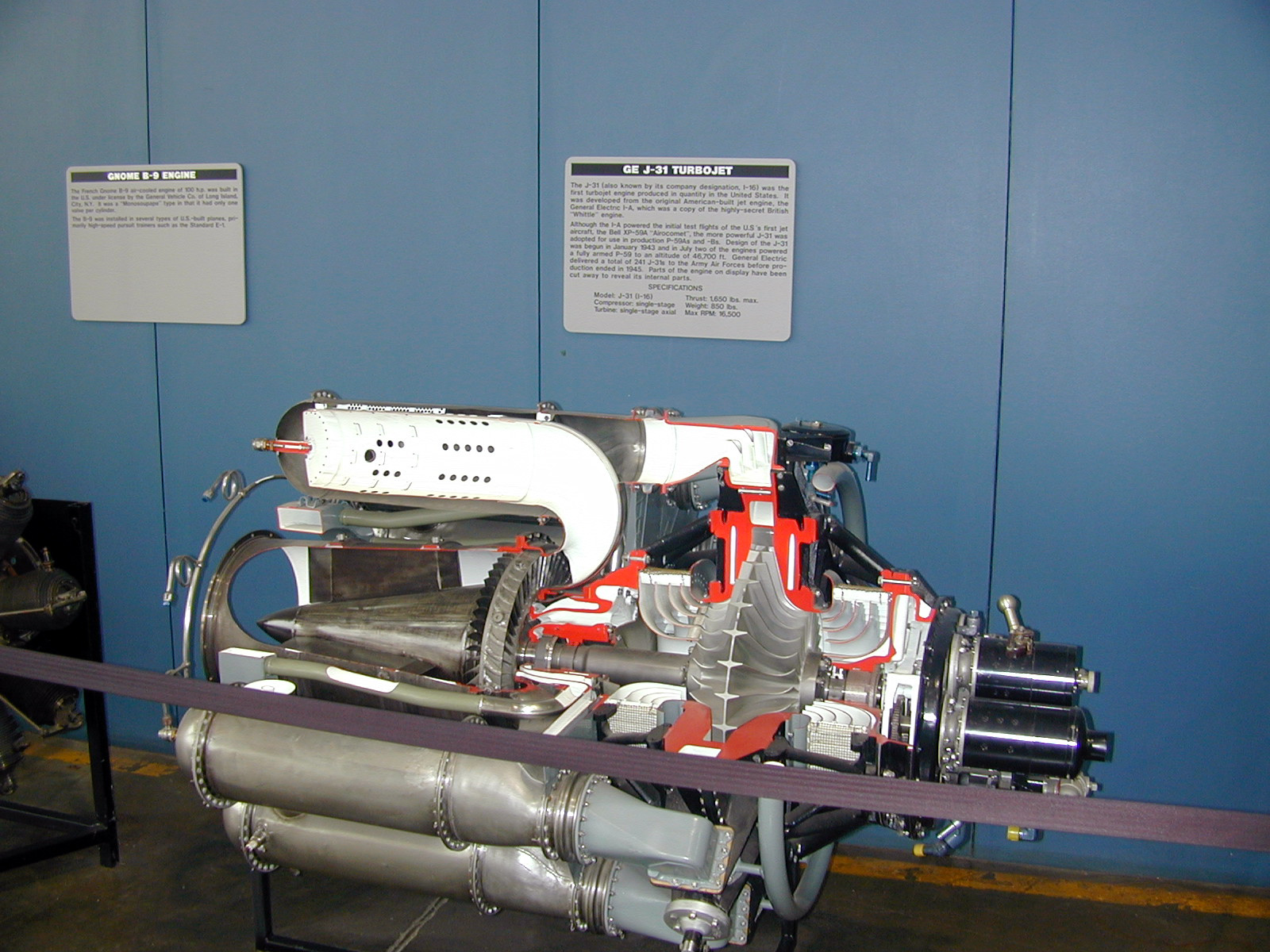

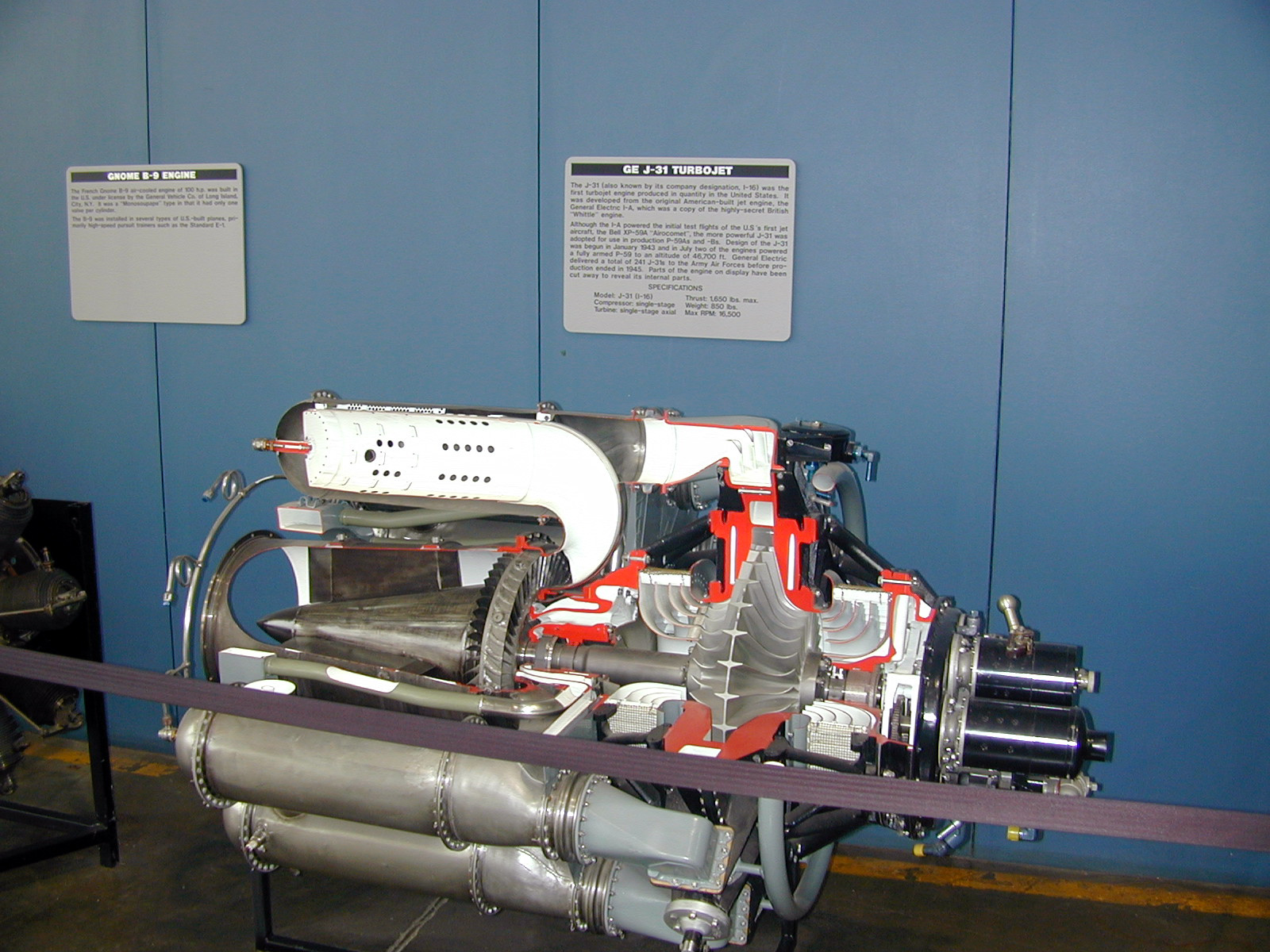

From 3 June until 14 August 1942 Whittle visited the United States. At the General Electric

General Electric Company (GE) is an American multinational conglomerate founded in 1892, and incorporated in New York state and headquartered in Boston. The company operated in sectors including healthcare, aviation, power, renewable energ ...

's Lynn Factory, Whittle reviewed the Type I Supercharger, GE's code name for their jet engine, based on Power Jets' W.1X. An improved version of the W.2B would also be built, called the I-16, incorporating features of the W.2/500. Whittle also toured the Bell Aircraft

The Bell Aircraft Corporation was an American aircraft manufacturer, a builder of several types of fighter aircraft for World War II but most famous for the Bell X-1, the first supersonic aircraft, and for the development and production of many ...

, and the three Bell XP-59A Airacomets, a twin-engine fighter powered by the General Electric I-A

The General Electric I-A was the first working jet engine in the United States, manufactured by General Electric (GE) and achieving its first run on April 18, 1942.

The engine was the result of receiving an imported Power Jets W.1X that was flo ...

jet engines. This fighter took flight in October 1942, one year and one day after GE received Power Jets' W.1X.

On 11 December 1942 Whittle had a meeting with Ministry of Aircraft Production Wilfrid Freeman

Air Chief Marshal Sir Wilfrid Rhodes Freeman, 1st Baronet, (18 July 1888 – 15 May 1953) was one of the most important influences on the rearmament of the Royal Air Force (RAF) in the years up to and including the Second World War.

RAF caree ...

and Air Marshal Linnell. According to Whittle, "He made it clear that he had definitely decided to transfer Barnoldswick and Clitheroe to Rolls-Royce management." Spencer Wilks

Spencer Bernau Wilks (26 May 189110 March 1971) was a British manager and administrator in the motor manufacturing industry. He served variously in positions including Managing Director, Chairman, and President of the Rover Company from 1929 unt ...

of Rover met with Hives and Hooker at the "Swan and Royal" pub, in Clitheroe, near the Barnoldswick factory. By arrangement with the Ministry of Aircraft Production they traded the jet factory at Barnoldswick for Rolls-Royce's tank engine

A tank locomotive or tank engine is a steam locomotive that carries its water in one or more on-board water tanks, instead of a more traditional tender. Most tank engines also have bunkers (or fuel tanks) to hold fuel; in a tender-tank locomo ...

factory in Nottingham.

Testing and production ramp-up was immediately accelerated. By January 1943, Rolls-Royce had achieved 400 hours of run time, ten times Rover's number of the previous month, and in May 1943, the W.2B passed its first 100-hour development test at of thrust.

When Rolls-Royce became involved, Ray Dorey, the manager of the company's Flight Centre at Hucknall Airfield

Hucknall Aerodrome was a former general aviation and RAF aerodrome located north northwest of Nottingham, Nottinghamshire, England and west of Hucknall town. The aerodrome had been operated by the Merlin Flying Club since 1971, and then by R ...

on the north side of Nottingham, had a Whittle W.2B engine installed in the rear of a Vickers Wellington

The Vickers Wellington was a British twin-engined, long-range medium bomber. It was designed during the mid-1930s at Brooklands in Weybridge, Surrey. Led by Vickers-Armstrongs' chief designer Rex Pierson; a key feature of the aircraft is its g ...

bomber. The installation was done by Vickers at Weybridge.

Continued impact

Whittle wanted to improve the efficiency of the jet engine at lower speeds. According to Whittle, "I wanted to 'gear down the jet', ie to convert a low-mass high-velocity jet into a high-mass low-velocity jet. The obvious way to do this was to use an additional turbine to extract energy from the jet and use this energy to drive a low-pressure compressor or fan capable of 'breathing' far more air than the jet engine itself and forcing this additional air rearwards as a 'cold jet'. The complete system is known as a '

Whittle wanted to improve the efficiency of the jet engine at lower speeds. According to Whittle, "I wanted to 'gear down the jet', ie to convert a low-mass high-velocity jet into a high-mass low-velocity jet. The obvious way to do this was to use an additional turbine to extract energy from the jet and use this energy to drive a low-pressure compressor or fan capable of 'breathing' far more air than the jet engine itself and forcing this additional air rearwards as a 'cold jet'. The complete system is known as a 'turbofan

The turbofan or fanjet is a type of airbreathing jet engine that is widely used in aircraft engine, aircraft propulsion. The word "turbofan" is a portmanteau of "turbine" and "fan": the ''turbo'' portion refers to a gas turbine engine which ac ...

'." The first embodiment was referred to as a No 1 Thrust Augmentor, which consisted of an "aft fan", or additional turbine, in the exhaust of the main engine. In 1942, No 2 Augmentor, a conventional two-stage system with the fan blades external to the turbine blades, was used by GE in the Convair 990 Coronado

The Convair 990 Coronado is an American narrow-body four-engined jet airliner produced between 1961 and 1963 by the Convair division of American company General Dynamics. It was a stretched version of its earlier Convair 880 produced in respon ...

. A No 3 Augmentor, known as the "tip turbine", had the turbine blades outside the fan. A No 4 Augmentor, in combination with the W2/700, included an afterburner

An afterburner (or reheat in British English) is an additional combustion component used on some jet engines, mostly those on military supersonic aircraft. Its purpose is to increase thrust, usually for supersonic flight, takeoff, and co ...

, was the design powerplant for the Miles M.52

The Miles M.52 was a turbojet-powered supersonic research aircraft project designed in the United Kingdom in the mid-1940s. In October 1943, Miles Aircraft was issued with a contract to produce the aircraft in accordance with Air Ministry Sp ...

project. According to Whittle, "The first attempt at the turbofan proper, ie having the fan ahead of and supercharging the core engine, was the LR1 intended as the power plant of a four-engined bomber for operations in the Pacific. The mass flow through the fan of the LR1 was to have been 3-4 times that through the core engine, ie the 'bypass ratio

The bypass ratio (BPR) of a turbofan engine is the ratio between the mass flow rate of the bypass stream to the mass flow rate entering the core. A 10:1 bypass ratio, for example, means that 10 kg of air passes through the bypass duct for ev ...

' was 2-3." Filed in March 1936, Whittle's main turbofan patent 471368, expired in 1962.

Whittle's work had caused a minor revolution within the British engine manufacturing industry and, even before the E.28/39 flew, most companies had set up their own research efforts. In 1939, Metropolitan-Vickers

Metropolitan-Vickers, Metrovick, or Metrovicks, was a British heavy electrical engineering company of the early-to-mid 20th century formerly known as British Westinghouse. Highly diversified, it was particularly well known for its industrial el ...

set up a project to develop an axial-flow design as a turboprop

A turboprop is a turbine engine that drives an aircraft propeller.

A turboprop consists of an intake, reduction gearbox, compressor, combustor, turbine, and a propelling nozzle. Air enters the intake and is compressed by the compressor. ...

but later re-engineered the design as a pure jet known as the Metrovick F.2. Rolls-Royce had already copied the W.1 to produce the low-rated WR.1 but later stopped work on this project after taking over Rover's efforts. In 1941, de Havilland started a jet fighter project, the Spider Crab — later called Vampire

A vampire is a mythical creature that subsists by feeding on the Vitalism, vital essence (generally in the form of blood) of the living. In European folklore, vampires are undead, undead creatures that often visited loved ones and caused mi ...

— along with their own engine to power it, Frank Halford

Major Frank Bernard Halford CBE FRAeS (7 March 1894 – 16 April 1955) was an English aircraft engine designer. He is best known for the series of de Havilland Gipsy engines, widely used by light aircraft in the 1920s and 30s.

Career

Educat ...

's Goblin

A goblin is a small, grotesque, monstrous creature that appears in the folklore of multiple European cultures. First attested in stories from the Middle Ages, they are ascribed conflicting abilities, temperaments, and appearances depending on ...

(Halford H.1). Armstrong Siddeley

Armstrong Siddeley was a British engineering group that operated during the first half of the 20th century. It was formed in 1919 and is best known for the production of luxury vehicles and aircraft engines.

The company was created following t ...

also developed a more complex axial-flow design with an engineer called Heppner, the ASX

Australian Securities Exchange Ltd or ASX, is an Australian public company that operates Australia's primary securities exchange, the Australian Securities Exchange (sometimes referred to outside of Australia as, or confused within Australia as ...

but reversed Vickers' thinking and later modified it into a turboprop instead, the Python

Python may refer to:

Snakes

* Pythonidae, a family of nonvenomous snakes found in Africa, Asia, and Australia

** ''Python'' (genus), a genus of Pythonidae found in Africa and Asia

* Python (mythology), a mythical serpent

Computing

* Python (pro ...

. The Bristol Aeroplane Company proposed to combine jet and piston engines but dropped the idea and concentrated on propeller turbines instead.

Nationalisation

During a demonstration of the E.28/39 toWinston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

in April 1943, Whittle proposed to Stafford Cripps, Minister of Aircraft Production, that all jet development be nationalised. He pointed out that the company had been funded by private investors who helped develop the engine successfully, only to see production contracts go to other companies. Nationalisation was the only way to repay those debts and ensure a fair deal for everyone, and he was willing to surrender his shares in Power Jets to make this happen. In October, Cripps told Whittle that he decided a better solution would be to nationalise Power Jets only.

Whittle believed that he had triggered this decision, but Cripps had already been considering how best to maintain a successful jet programme and act responsibly regarding the state's substantial financial investment, while at the same time wanting to establish a research centre that could use Power Jets' talents, and had come to the conclusion that national interests demanded the setting up of a Government-owned establishment. On 1 December Cripps advised Power Jets' directors that the Treasury would not pay more than £100,000 for the company.

In January 1944 Whittle was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

in the New Year Honours

The New Year Honours is a part of the British honours system, with New Year's Day, 1 January, being marked by naming new members of orders of chivalry and recipients of other official honours. A number of other Commonwealth realms also mark this ...

. By this time he was a group captain

Group captain is a senior commissioned rank in the Royal Air Force, where it originated, as well as the air forces of many countries that have historical British influence. It is sometimes used as the English translation of an equivalent rank i ...

, having been promoted from wing commander

Wing commander (Wg Cdr in the RAF, the IAF, and the PAF, WGCDR in the RNZAF and RAAF, formerly sometimes W/C in all services) is a senior commissioned rank in the British Royal Air Force and air forces of many countries which have historical ...

in July 1943. Later that month after further negotiations the Ministry made another offer of £135,500 for Power Jets, which was reluctantly accepted after the Ministry refused arbitration on the matter. Since Whittle had already offered to surrender his shares he would receive nothing at all, while Williams and Tinling each received almost £46,800 for their stock, and investors of cash or services had a threefold return on their original investment. Whittle met with Cripps to object personally to the nationalisation efforts and how they were being handled, but to no avail. The final terms were agreed on 28 March, and Power Jets officially became Power Jets (Research and Development) Ltd, with Roxbee Cox as chairman, Constant of RAE Head of Engineering Division, and Whittle as Chief Technical Advisor. On 5 April 1944, the Ministry sent Whittle an award of only £10,000 for his shares.

From the end of March, Whittle spent six months in hospital recovering from nervous exhaustion, and resigned from Power Jets (R and D) Ltd in January 1946. In July the company was merged with the gas turbine division of the RAE to form the National Gas Turbine Establishment

The National Gas Turbine Establishment (NGTE Pyestock) in Farnborough, part of the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE), was the prime site in the UK for design and development of gas turbine and jet engines. It was created by merging the design te ...

(NGTE) at Farnborough, and 16 Power Jets engineers, following Whittle's example, also resigned.

After the war

In 1946, Whittle accepted a post as Technical Advisor on Engine Design and Production to Controller of Supplies (Air); was made a Commander of the US

In 1946, Whittle accepted a post as Technical Advisor on Engine Design and Production to Controller of Supplies (Air); was made a Commander of the US Legion of Merit

The Legion of Merit (LOM) is a military award of the United States Armed Forces that is given for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services and achievements. The decoration is issued to members of the eight ...

; and was appointed a Companion of the Order of the Bath

Companion may refer to:

Relationships Currently

* Any of several interpersonal relationships such as friend or acquaintance

* A domestic partner, akin to a spouse

* Sober companion, an addiction treatment coach

* Companion (caregiving), a caregive ...

in 1947. During May 1948 Whittle received an ex-gratia

(; also spelled ''ex-gratia'') is Latin for "by favour", and is most often used in a legal context. When something has been done ''ex gratia'', it has been done voluntarily, out of kindness or grace. In law, an ''ex gratia payment'' is a paymen ...

award of £100,000 from the Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors in recognition of his work on the jet engine, and two months later he was made a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established ...

.

During a lecture tour in the US, Whittle again broke down and retired from the RAF on medical grounds on 26 August 1948, leaving with the rank of air commodore. He joined BOAC

British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) was the British state-owned airline created in 1939 by the merger of Imperial Airways and British Airways Ltd. It continued operating overseas services throughout World War II. After the passi ...

as a technical advisor on aircraft gas turbines and travelled extensively over the next few years, viewing jet engine developments in the United States, Canada, Africa, Asia and the Middle East. He left BOAC in 1952 and spent the next year working on a biography, ''Jet: The Story of a Pioneer''. He was awarded the Royal Society of Arts

The Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (RSA), also known as the Royal Society of Arts, is a London-based organisation committed to finding practical solutions to social challenges. The RSA acronym is used m ...

' Albert Medal that year.

Returning to work in 1953, he accepted a position as a Mechanical Engineering Specialist with Shell

Shell may refer to:

Architecture and design

* Shell (structure), a thin structure

** Concrete shell, a thin shell of concrete, usually with no interior columns or exterior buttresses

** Thin-shell structure

Science Biology

* Seashell, a hard o ...