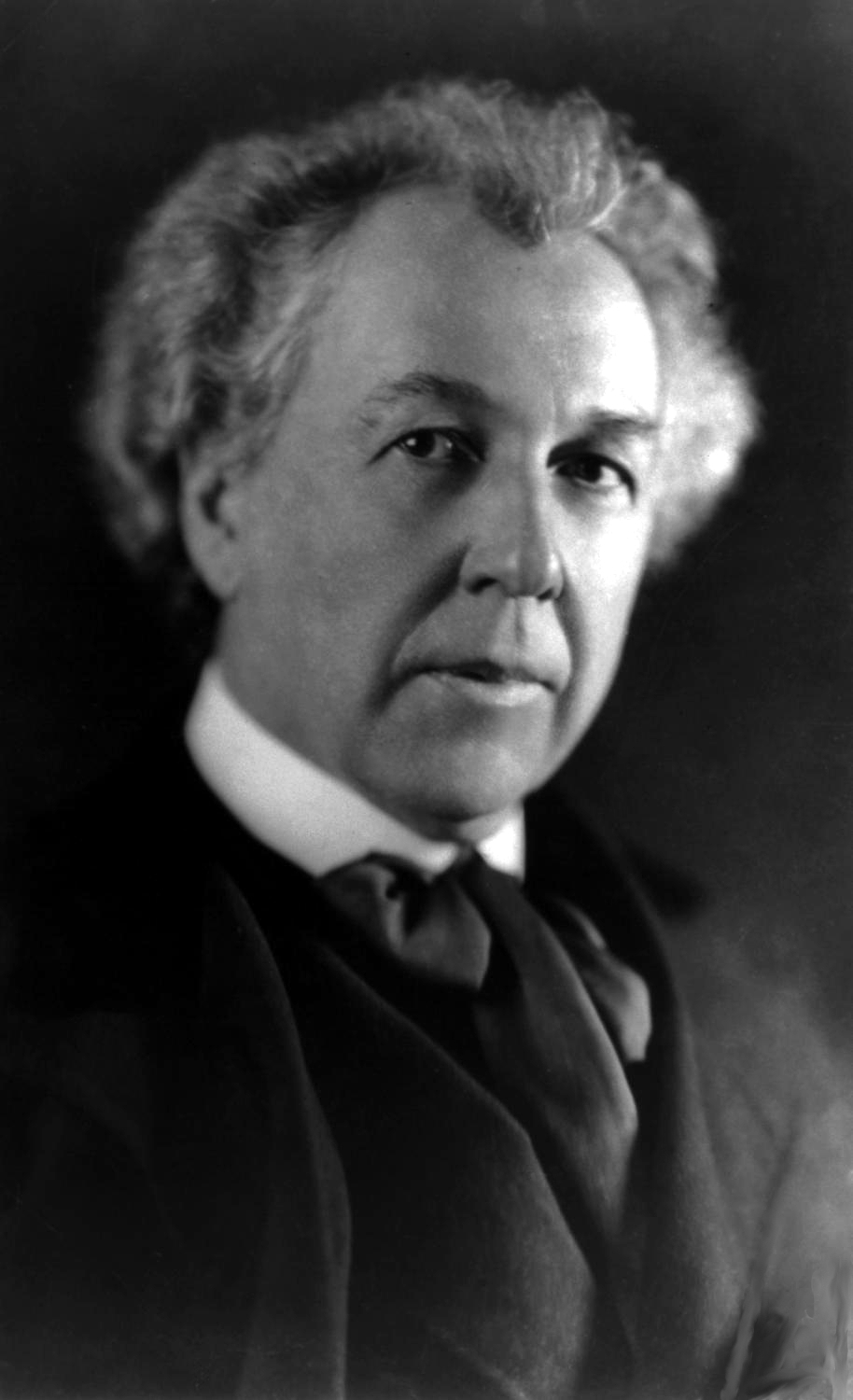

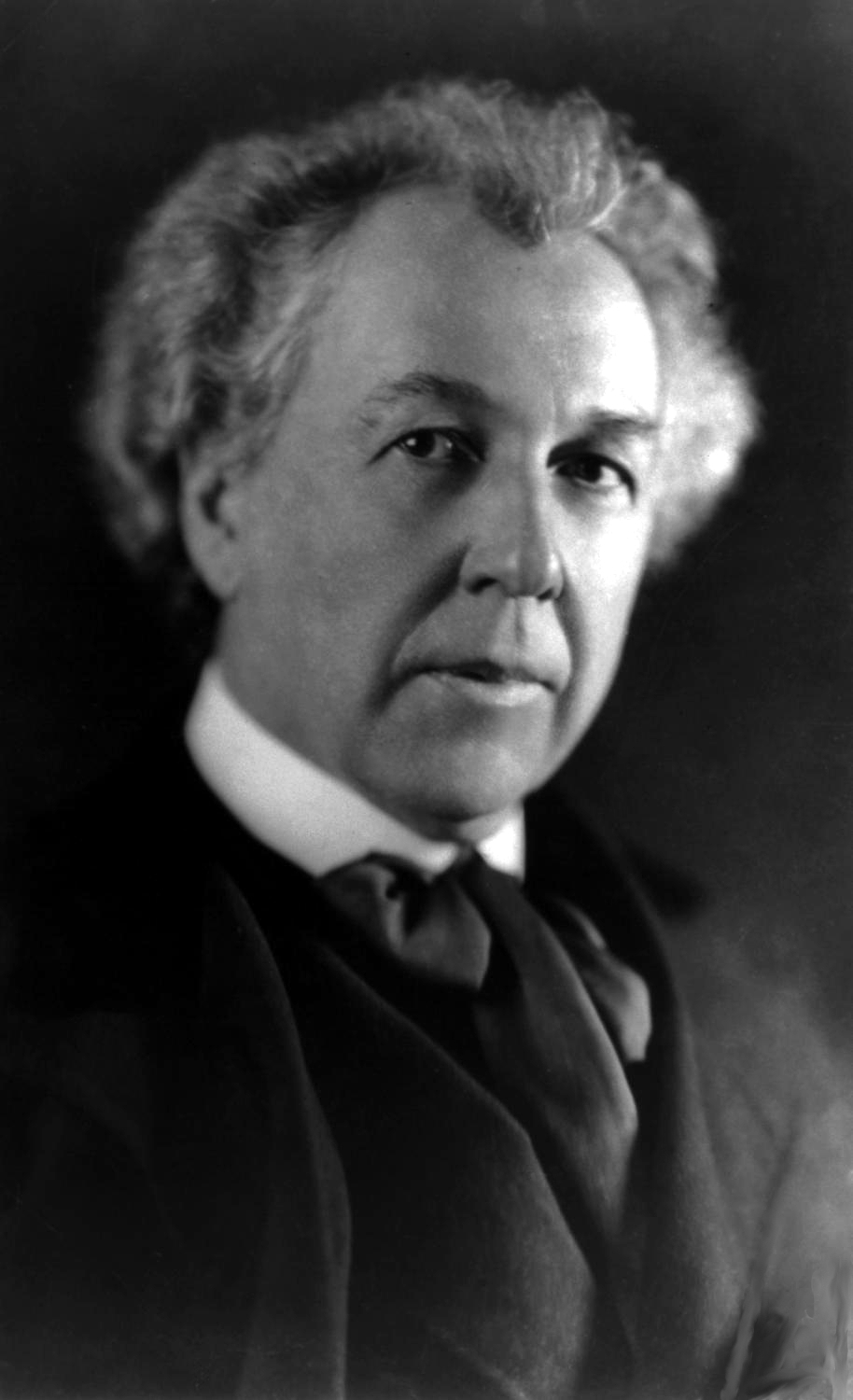

Frank Lloyd Wright (June 8, 1867 – April 9, 1959) was an American architect, designer, writer, and educator. He designed

more than 1,000 structures over a creative period of 70 years. Wright played a key role in the architectural movements of the twentieth century, influencing architects worldwide through his works and hundreds of apprentices in his

Taliesin Fellowship

The School of Architecture is a private architecture school in Paradise Valley, Arizona. It was founded in 1986 as an accredited school by surviving members of the Taliesin Fellowship. The school offers a Master of Architecture program that focus ...

. Wright believed in designing in harmony with humanity and the environment, a philosophy he called

organic architecture

Organic architecture is a philosophy of architecture which promotes harmony between human habitation and the natural world. This is achieved through design approaches that aim to be sympathetic and well-integrated with a site, so buildings, furn ...

. This philosophy was exemplified in

Fallingwater

Fallingwater is a house designed by the architect Frank Lloyd Wright in 1935 in the Laurel Highlands of southwest Pennsylvania, about southeast of Pittsburgh in the United States. It is built partly over a waterfall on Bear Run in the Mill R ...

(1935), which has been called "the best all-time work of American architecture".

Wright was the pioneer of what came to be called the

Prairie School movement of architecture and also developed the concept of the

Usonia

Usonia () is a word that was used by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright to refer to the United States in general (in preference to ''America''), and more specifically to his vision for the landscape of the country, including the planning of ...

n home in

Broadacre City

Broadacre City was an urban or suburban development concept proposed by Frank Lloyd Wright throughout most of his lifetime. He presented the idea in his book ''The Disappearing City'' in 1932. A few years later he unveiled a very detailed twelve- ...

, his vision for urban planning in the United States. He also designed original and innovative offices, churches, schools, skyscrapers, hotels, museums, and other commercial projects. Wright-designed interior elements (including

leaded glass windows, floors, furniture and even tableware) were integrated into these structures. He wrote several books and numerous articles and was a popular lecturer in the United States and in Europe. Wright was recognized in 1991 by the

American Institute of Architects

The American Institute of Architects (AIA) is a professional organization for architects in the United States. Headquartered in Washington, D.C., the AIA offers education, government advocacy, community redevelopment, and public outreach to su ...

as "the greatest American architect of all time".

In 2019, a selection of his work became a listed

World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for h ...

as ''

The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright

The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright is a UNESCO World Heritage Site consisting of a selection of eight buildings across the United States that were designed by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright. These sites demonstrate his phi ...

''.

Raised in rural Wisconsin, Wright studied civil engineering at the

University of Wisconsin

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, t ...

and then apprenticed in Chicago, briefly with

Joseph Lyman Silsbee

Joseph Lyman Silsbee (November 25, 1848 – January 31, 1913) was a significant American architect during the 19th and 20th centuries. He was well known for his facility of drawing and gift for designing buildings in a variety of styles. His most ...

, and then with

Louis Sullivan

Louis Henry Sullivan (September 3, 1856 – April 14, 1924) was an American architect, and has been called a "father of skyscrapers" and "father of modernism". He was an influential architect of the Chicago School, a mentor to Frank Lloy ...

at

Adler & Sullivan Adler & Sullivan was an architectural firm founded by Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan in Chicago. Among its projects was the multi-purpose Auditorium Building in Chicago and the Wainwright Building skyscraper in St Louis. In 1883 Louis Sullivan was ...

. Wright opened his own successful Chicago practice in 1893 and established a studio in his

Oak Park, Illinois

Oak Park is a village in Cook County, Illinois, adjacent to Chicago. It is the 29th-most populous municipality in Illinois with a population of 54,583 as of the 2020 U.S. Census estimate. Oak Park was first settled in 1835 and later incorporated ...

home in 1898. His fame increased and his personal life sometimes made headlines: leaving his first wife Catherine Tobin for

Mamah Cheney in 1909; the murder of Mamah and her children and others at his

Taliesin estate by a staff member in 1914; his tempestuous marriage with second wife Miriam Noel (m. 1923–1927); and his courtship and marriage with

Olgivanna Lazović (m. 1928–1959).

Early years

Ancestry

Frank Lloyd Wright was born on June 8, 1867, in the town of

Richland Center, Wisconsin

Richland Center is a city in Richland County, Wisconsin, United States that also serves as the county seat. The population was 5,114 at the 2020 census.

History

Richland Center was founded in 1851 by Ira Sherwin Hazeltine, a native of Andover, V ...

, but maintained throughout his life that he was born in 1869.

In 1987 a biographer of Wright suggested that he may have been christened as "Frank Lincoln Wright" or "Franklin Lincoln Wright" but these assertions were not supported by any evidence.

Wright's father, William Cary Wright (1825–1904), was a "gifted musician, orator, and sometime preacher who had been admitted to the bar in 1857."

He was also a published composer. Originally from

, William Wright had been a

Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compe ...

minister, but he later joined his wife's family in the

Unitarian faith.

Wright's mother, Anna Lloyd Jones (1838/39–1923) was a teacher and a member of the Lloyd Jones clan; her parents had emigrated from

Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

to

Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

. One of Anna's brothers was

Jenkin Lloyd Jones

Jenkin Lloyd Jones (November 14, 1843 – September 12, 1918) was a Unitarian minister in the United States, and also the uncle of Frank Lloyd Wright. He founded All Souls Unitarian Church in Chicago, Illinois, as well as its community outr ...

, an important figure in the spread of the Unitarian faith in the

Midwest.

Childhood (1867–1885)

According to Wright's autobiography, his mother declared when she was expecting that her first child would grow up to build beautiful buildings. She decorated his nursery with engravings of English cathedrals torn from a periodical to encourage the infant's ambition.

Wright grew up in a "unstable household,

..constant lack of resources,

..unrelieved poverty and anxiety" and had a "deeply disturbed and obviously unhappy childhood".

His father held pastorates in

McGregor, Iowa (1869),

Pawtucket, Rhode Island

Pawtucket is a city in Providence County, Rhode Island, United States. The population was 75,604 at the 2020 census, making the city the fourth-largest in the state. Pawtucket borders Providence and East Providence to the south, Central Fal ...

(1871), and

Weymouth, Massachusetts ("To Work Is to Conquer")

, image_map = Norfolk County Massachusetts incorporated and unincorporated areas Weymouth highlighted.svg

, mapsize = 250px

, map_caption = Location in Norfolk County in Massa ...

(1874). Because the Wright family struggled financially also in Weymouth, they returned to Spring Green, where the supportive Lloyd Jones family could help William find employment. In 1877, they settled in

Madison Madison may refer to:

People

* Madison (name), a given name and a surname

* James Madison (1751–1836), fourth president of the United States

Place names

* Madison, Wisconsin, the state capital of Wisconsin and the largest city known by this ...

, where William gave music lessons and served as the secretary to the newly formed Unitarian society. Although William was a distant parent, he shared his love of music with his children.

In 1876, Anna saw an exhibit of educational blocks called the

Froebel Gifts

The Froebel gifts (german: Fröbelgaben) are educational play materials for young children, originally designed by Friedrich Fröbel for the first kindergarten at Bad Blankenburg. Playing with Froebel gifts, singing, dancing, and growing plants we ...

, the foundation of an innovative

kindergarten

Kindergarten is a preschool educational approach based on playing, singing, practical activities such as drawing, and social interaction as part of the transition from home to school. Such institutions were originally made in the late 18th ce ...

curriculum. Anna, a trained teacher, was excited by the program and bought a set with which the 9-year old Wright spent much time playing. The blocks in the set were geometrically shaped and could be assembled in various combinations to form two- and three-dimensional compositions. In his autobiography, Wright described the influence of these exercises on his approach to design: "For several years, I sat at the little kindergarten table-top... and played... with the cube, the sphere and the triangle— these smooth wooden maple blocks... All are in my fingers to this day... "

In 1881, soon after Wright turned 14, his parents separated. In 1884, his father sued for a divorce from Anna on the grounds of "... emotional cruelty and physical violence and spousal abandonment". Wright attended

Madison High School Madison High School may refer to:

* Madison County High School (Alabama), Gurley, Alabama

* Madison High School (Idaho), Rexburg, Idaho

* Madison Consolidated High School, Madison, Indiana

* Madison High School (Kansas), Madison, Kansas

* Kentuc ...

, but there is no evidence that he graduated. His father left Wisconsin after the divorce was granted in 1885. Wright said that he never saw his father again.

Education (1885–1887)

In 1886, at age 19, Wright wanted to become an architect; he was admitted to the

University of Wisconsin–Madison

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United Stat ...

as a special student and worked under Allan D. Conover, a professor of civil engineering, before leaving the school without taking a degree. Wright was granted an honorary doctorate of fine arts from the university in 1955. In 1886 Wright collaborated with the Chicago architectural firm of Joseph Lyman Silsbee —accredited as draftsman and construction supervisor— on the 1886

Unity Chapel for Wright's family in Spring Green, Wisconsin.

Early career

Silsbee and other early work experience (1887–1888)

In 1887, Wright arrived in Chicago in search of employment. As a result of the devastating

Great Chicago Fire of 1871

The Great Chicago Fire was a conflagration that burned in the American city of Chicago during October 8–10, 1871. The fire killed approximately 300 people, destroyed roughly of the city including over 17,000 structures, and left more than 10 ...

and a population boom, new development was plentiful. Wright later recorded in his autobiography that his first impression of Chicago was as an ugly and chaotic city. Within days of his arrival, and after interviews with several prominent firms, he was hired as a

draftsman

A drafter (also draughtsman / draughtswoman in British and Commonwealth English, draftsman / draftswoman or drafting technician in American and Canadian English) is an engineering technician who makes detailed technical drawings or plans for ...

with Joseph Lyman Silsbee.

While with the firm, he also worked on two other family projects: All Souls Church in Chicago for his uncle, Jenkin Lloyd Jones, and the

Hillside Home School I

Hillside Home School I, also known as the Hillside Home Building, was a Shingle Style building that architect Frank Lloyd Wright designed in 1887 for his aunts, Ellen and Jane Lloyd Jones for their Hillside Home School in the town of Wyoming, ...

in Spring Green for two of his aunts.

Other draftsmen who worked for Silsbee in 1887 included future architects Cecil Corwin,

George W. Maher

George Washington Maher (December 25, 1864 – September 12, 1926) was an American architect during the first quarter of the 20th century. He is considered part of the Prairie School-style and was known for blending traditional architecture wit ...

, and

George G. Elmslie. Wright soon befriended Corwin, with whom he lived until he found a permanent home.

Feeling that he was underpaid for the quality of his work for Silsbee at $8 a week, the young draftsman quit and found work as an

architectural designer

The term architectural designer may refer to a building designer who is not a registered architect, architectural technologist or any other person that is involved in the design process of buildings or urban landscapes.

Architectural designers ...

at the firm of Beers, Clay, and Dutton. However, Wright soon realized that he was not ready to handle building design by himself; he left his new job to return to Joseph Silsbee—this time with a raise in salary. Although Silsbee adhered mainly to

Victorian and

Revivalist architecture, Wright found his work to be more "gracefully picturesque" than the other "brutalities" of the period.

Adler & Sullivan (1888–1893)

Wright learned that the Chicago firm of

Adler & Sullivan Adler & Sullivan was an architectural firm founded by Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan in Chicago. Among its projects was the multi-purpose Auditorium Building in Chicago and the Wainwright Building skyscraper in St Louis. In 1883 Louis Sullivan was ...

was "... looking for someone to make the finished drawings for the interior of the

Auditorium Building

The Auditorium Building in Chicago is one of the best-known designs of Louis Sullivan and Dankmar Adler. Completed in 1889, the building is located at the northwest corner of South Michigan Avenue and Ida B. Wells Drive. The building was des ...

". Wright demonstrated that he was a competent impressionist of Louis Sullivan's ornamental designs and two short interviews later, was an official

apprentice

Apprenticeship is a system for training a new generation of practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study (classroom work and reading). Apprenticeships can also enable practitioners to gain a ...

in the firm. Wright did not get along well with Sullivan's other draftsmen; he wrote that several violent altercations occurred between them during the first years of his apprenticeship. For that matter, Sullivan showed very little respect for his own employees as well. In spite of this, "Sullivan took

right

Rights are legal, social, or ethical principles of freedom or entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal system, social convention, or ethical ...

under his wing and gave him great design responsibility."

As an act of respect, Wright would later refer to Sullivan as (German for "Dear Master").

He also formed a bond with office foreman Paul Mueller. Wright later engaged Mueller in the construction of several of his public and commercial buildings between 1903 and 1923.

By 1890, Wright had an office next to Sullivan's that he shared with friend and draftsman

George Elmslie

George Grant Elmslie (February 20, 1869 – April 23, 1952) was a Scottish-born American Prairie School architect whose work is mostly found in the Midwestern United States. He worked with Louis Sullivan and later with William Gray Purcell as ...

, who had been hired by Sullivan at Wright's request.

[ During this time, Wright worked on Sullivan's bungalow (1890) and the James A. Charnley bungalow (1890) in ]Ocean Springs, Mississippi

Ocean Springs is a city in Jackson County, Mississippi, United States, approximately east of Biloxi and west of Gautier. It is part of the Pascagoula, Mississippi Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 17,225 at the 2000 U.S. Census ...

, the Berry-MacHarg House, James A. Charnley House

The James Charnley Residence, also known as the Charnley-Persky House, is a historic house museum at 1365 North Astor Street in the Gold Coast, Chicago, Gold Coast neighborhood of Chicago, Illinois. Built in 1892, it is one of the few surviv ...

(both 1891), and the Louis Sullivan House (1892), all in Chicago. Despite Sullivan's loan and overtime salary, Wright was constantly short on funds. Wright admitted that his poor finances were likely due to his expensive tastes in wardrobe and vehicles, and the extra luxuries he designed into his house. To supplement his income and repay his debts, Wright accepted independent commissions for at least nine houses. These "bootlegged" houses, as he later called them, were conservatively designed in variations of the fashionable Queen Anne and

Despite Sullivan's loan and overtime salary, Wright was constantly short on funds. Wright admitted that his poor finances were likely due to his expensive tastes in wardrobe and vehicles, and the extra luxuries he designed into his house. To supplement his income and repay his debts, Wright accepted independent commissions for at least nine houses. These "bootlegged" houses, as he later called them, were conservatively designed in variations of the fashionable Queen Anne and Colonial Revival

The Colonial Revival architectural style seeks to revive elements of American colonial architecture.

The beginnings of the Colonial Revival style are often attributed to the Centennial Exhibition of 1876, which reawakened Americans to the archit ...

styles. Nevertheless, unlike the prevailing architecture of the period, each house emphasized simple geometric massing and contained features such as bands of horizontal windows, occasional cantilever

A cantilever is a rigid structural element that extends horizontally and is supported at only one end. Typically it extends from a flat vertical surface such as a wall, to which it must be firmly attached. Like other structural elements, a cant ...

s, and open floor plans, which would become hallmarks of his later work. Eight of these early houses remain today, including the Thomas Gale

Thomas Gale (1635/1636?7 or 8 April 1702) was an English classical scholar, antiquarian and cleric.

Life

Gale was born at Scruton, Yorkshire. He was educated at Westminster School and Trinity College, Cambridge, of which he became a fellow ...

, Robert Parker, George Blossom, and Walter Gale houses.

As with the residential projects for Adler & Sullivan, he designed his bootleg houses on his own time. Sullivan knew nothing of the independent works until 1893, when he recognized that one of the houses was unmistakably a Frank Lloyd Wright design. This particular house, built for Allison Harlan, was only blocks away from Sullivan's townhouse in the Chicago community of Kenwood. Aside from the location, the geometric purity of the composition and balcony tracery

Tracery is an architectural device by which windows (or screens, panels, and vaults) are divided into sections of various proportions by stone ''bars'' or ''ribs'' of moulding. Most commonly, it refers to the stonework elements that support the ...

in the same style as the Charnley House likely gave away Wright's involvement. Since Wright's five-year contract forbade any outside work, the incident led to his departure from Sullivan's firm.[ Several stories recount the break in the relationship between Sullivan and Wright; even Wright later told two different versions of the occurrence. In ''An Autobiography'', Wright claimed that he was unaware that his side ventures were a breach of his contract. When Sullivan learned of them, he was angered and offended; he prohibited any further outside commissions and refused to issue Wright the ]deed

In common law, a deed is any legal instrument in writing which passes, affirms or confirms an interest, right, or property and that is signed, attested, delivered, and in some jurisdictions, sealed. It is commonly associated with transferring ...

to his Oak Park house until after he completed his five years. Wright could not bear the new hostility from his master and thought that the situation was unjust. He "... threw down ispencil and walked out of the Adler & Sullivan office never to return". Dankmar Adler, who was more sympathetic to Wright's actions, later sent him the deed. However, Wright told his Taliesin

Taliesin ( , ; 6th century AD) was an early Brittonic poet of Sub-Roman Britain whose work has possibly survived in a Middle Welsh manuscript, the '' Book of Taliesin''. Taliesin was a renowned bard who is believed to have sung at the courts ...

apprentices (as recorded by Edgar Tafel

Edgar A. Tafel (March 12, 1912 – January 18, 2011)Dunlap, David W''The New York Times'' (January 24, 2011) was an American architect, best known as a disciple of Frank Lloyd Wright.

Early life and career

Tafel was born in New York City to R ...

) that Sullivan fired him on the spot upon learning of the Harlan House. Tafel also recounted that Wright had Cecil Corwin sign several of the bootleg jobs, indicating that Wright was aware of their forbidden nature. Regardless of the correct series of events, Wright and Sullivan did not meet or speak for 12 years.[

]

Transition and experimentation (1893–1900)

After leaving Adler & Sullivan, Wright established his own practice on the top floor of the Sullivan-designed Schiller Building

The Schiller Theater Building was designed by Louis Sullivan and Dankmar Adler of the firm Adler & Sullivan for the German Opera Company. At the time of its construction, it was among the tallest buildings in Chicago. Its centerpiece was a 1300-s ...

on Randolph Street

Randolph Street is a street in Chicago. It runs east–west through the Chicago Loop, carrying westbound traffic west from Michigan Avenue across the Chicago River on the Randolph Street Bridge, interchanging with the Kennedy Expressway (I-90/ I ...

in Chicago. Wright chose to locate his office in the building because the tower location reminded him of the office of Adler & Sullivan. Cecil Corwin followed Wright and set up his architecture practice in the same office, but the two worked independently and did not consider themselves partners.

In 1896, Wright moved from the Schiller Building to the nearby and newly completed Steinway Hall

Steinway Hall (German: ) is the name of buildings housing concert halls, showrooms and sales departments for Steinway & Sons pianos. The first Steinway Hall was opened in 1866 in New York City. Today, Steinway Halls and are located in cities such ...

building. The loft space was shared with Robert C. Spencer, Jr., Myron Hunt

Myron Hubbard Hunt (February 27, 1868 – May 26, 1952) was an American architect whose numerous projects include many noted landmarks in Southern California and Evanston, Illinois. Hunt was elected a Fellow in the American Institute of Archi ...

, and Dwight H. Perkins. These young architects, inspired by the Arts and Crafts Movement and the philosophies of Louis Sullivan, formed what became known as the Prairie School.Marion Mahony

Marion Mahony Griffin (; February 14, 1871 – August 10, 1961) was an American architect and artist. She was one of the first licensed female architects in the world, and is considered an original member of the Prairie School. Her work in ...

, who in 1895 transferred to Wright's team of drafters and took over production of his presentation drawings and watercolor renderings. Mahony, the third woman to be licensed as an architect in Illinois and one of the first licensed female architects in the U.S., also designed furniture, leaded glass windows, and light fixtures, among other features, for Wright's houses. Between 1894 and the early 1910s, several other leading Prairie School architects and many of Wright's future employees launched their careers in the offices of Steinway Hall. Wright's projects during this period followed two basic models. His first independent commission, the Winslow House, combined Sullivanesque ornamentation with the emphasis on simple geometry and horizontal lines. The Francis Apartments (1895, demolished 1971),

Wright's projects during this period followed two basic models. His first independent commission, the Winslow House, combined Sullivanesque ornamentation with the emphasis on simple geometry and horizontal lines. The Francis Apartments (1895, demolished 1971), Heller House

The Isidore H. Heller House is a house located at 5132 South Woodlawn Avenue in the Hyde Park community area of Chicago in Cook County, Illinois, United States. The house was designed by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright. The design is c ...

(1896), Rollin Furbeck House

Rollin Furbeck House is a Frank Lloyd Wright designed house in Oak Park, Illinois that was built in 1897. It is part of the Frank Lloyd Wright-Prairie School of Architecture Historic District.

Architecture

The house is considered a major tra ...

(1897) and Husser House (1899, demolished 1926) were designed in the same mode. For his more conservative clients, Wright designed more traditional dwellings. These included the Dutch Colonial Revival

Dutch Colonial is a style of domestic architecture, primarily characterized by gambrel roofs having curved eaves along the length of the house. Modern versions built in the early 20th century are more accurately referred to as "Dutch Colonial Rev ...

style Bagley House (1894), Tudor Revival

Tudor Revival architecture (also known as mock Tudor in the UK) first manifested itself in domestic architecture in the United Kingdom in the latter half of the 19th century. Based on revival of aspects that were perceived as Tudor architecture ...

style Moore House I (1895), and Queen Anne style Charles E. Roberts

Charles E. Roberts (March 13, 1843 – March 1934) was an American engineer, inventor and an important early client and patron of Frank Lloyd Wright. In 1896, Wright remodeled Robert's house in Oak Park.

Personal life

Charles E Roberts was b ...

House (1896). While Wright could not afford to turn down clients over disagreements in taste, even his most conservative designs retained simplified massing and occasional Sullivan-inspired details.

Soon after the completion of the Winslow House in 1894, Edward Waller, a friend and former client, invited Wright to meet Chicago architect and planner

Soon after the completion of the Winslow House in 1894, Edward Waller, a friend and former client, invited Wright to meet Chicago architect and planner Daniel Burnham

Daniel Hudson Burnham (September 4, 1846 – June 1, 1912) was an American architect and urban designer. A proponent of the '' Beaux-Arts'' movement, he may have been, "the most successful power broker the American architectural profession has ...

. Burnham had been impressed by the Winslow House and other examples of Wright's work; he offered to finance a four-year education at the and two years in Rome. To top it off, Wright would have a position in Burnham's firm upon his return. In spite of guaranteed success and support of his family, Wright declined the offer. Burnham, who had directed the classical design of the World's Columbian Exposition

The World's Columbian Exposition (also known as the Chicago World's Fair) was a world's fair held in Chicago in 1893 to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's arrival in the New World in 1492. The centerpiece of the Fair, hel ...

and was a major proponent of the Beaux Arts movement, thought that Wright was making a foolish mistake. Yet for Wright, the classical education of the lacked creativity and was altogether at odds with his vision of modern American architecture. Wright relocated his practice to his home in 1898 to bring his work and family lives closer. This move made further sense as the majority of the architect's projects at that time were in Oak Park or neighboring River Forest. The birth of three more children prompted Wright to sacrifice his original home studio space for additional bedrooms and necessitated his design and construction of an expansive studio addition to the north of the main house. The space, which included a hanging

Wright relocated his practice to his home in 1898 to bring his work and family lives closer. This move made further sense as the majority of the architect's projects at that time were in Oak Park or neighboring River Forest. The birth of three more children prompted Wright to sacrifice his original home studio space for additional bedrooms and necessitated his design and construction of an expansive studio addition to the north of the main house. The space, which included a hanging balcony

A balcony (from it, balcone, "scaffold") is a platform projecting from the wall of a building, supported by columns or console brackets, and enclosed with a balustrade, usually above the ground floor.

Types

The traditional Maltese balcony ...

within the two-story drafting room, was one of Wright's first experiments with innovative structure. The studio embodied Wright's developing aesthetics and would become the laboratory from which his next 10 years of architectural creations would emerge.

Prairie Style houses (1900–1914)

By 1901, Wright had completed about 50 projects, including many houses in Oak Park. As his son John Lloyd Wright wrote:

William Eugene Drummond

William Eugene Drummond (March 28, 1876 – September 13, 1948) was a Chicago Prairie School architect.

Early years and education

He was born in Newark, New Jersey, the son of carpenter and cabinet maker Eugene Drummond and his wife Ida Marietta ...

, Francis Barry Byrne

Francis Barry Byrne (December 19, 1883 – December 18, 1967) was a member of the group of architects known as the Prairie School. After the demise of the Prairie School, about 1914 to 1916, Byrne continued as a successful architect by dev ...

, Walter Burley Griffin

Walter Burley Griffin (November 24, 1876February 11, 1937) was an American architect and landscape architect. He is known for designing Canberra, Australia's capital city and the New South Wales towns of Griffith and Leeton. He has been cr ...

, Albert Chase McArthur

Albert Chase McArthur (February 2, 1881 – March 1951) was a Prairie School architect, and the designer of the Arizona Biltmore Hotel in Phoenix, Arizona.

Early years

Albert McArthur was born on February 2, 1881, in Dubuque, Iowa. He was th ...

, Marion Mahony

Marion Mahony Griffin (; February 14, 1871 – August 10, 1961) was an American architect and artist. She was one of the first licensed female architects in the world, and is considered an original member of the Prairie School. Her work in ...

, Isabel Roberts

Isabel Roberts (March 1871 – December 27, 1955) was a Prairie School figure, member of the architectural design team in the Oak Park Studio of Frank Lloyd Wright and partner with Ida Annah Ryan in the Orlando, Florida architecture firm, "R ...

, and George Willis were the draftsmen. Five men, two women. They wore flowing ties, and smocks suitable to the realm. The men wore their hair like Papa, all except Albert, he didn't have enough hair. They worshiped Papa! Papa liked them! I know that each one of them was then making valuable contributions to the pioneering of the modern American architecture for which my father gets the full glory, headaches, and recognition today!

Between 1900 and 1901, Frank Lloyd Wright completed four houses, which have since been identified as the onset of the "

Between 1900 and 1901, Frank Lloyd Wright completed four houses, which have since been identified as the onset of the "Prairie Style

Prairie School is a late 19th- and early 20th-century architectural style, most common in the Midwestern United States. The style is usually marked by horizontal lines, flat or hipped roofs with broad overhanging eaves, windows grouped i ...

". Two, the Hickox and Bradley Houses, were the last transitional step between Wright's early designs and the Prairie creations.Willits House

The Ward W. Willits House is a building designed by architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Designed in 1901, the Willits house is considered one of the first of the great Prairie School houses. Built in the Chicago suburb of Highland Park, Illinois, th ...

received recognition as the first mature examples of the new style.Curtis Publishing Company

The Curtis Publishing Company, founded in 1891 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, became one of the largest and most influential publishers in the United States during the early 20th century. The company's publications included the ''Ladies' Home Jour ...

, Edward Bok

Edward William Bok (born Eduard Willem Gerard Cesar Hidde Bok) (October 9, 1863 – January 9, 1930) was a Dutch-born American editor and Pulitzer Prize-winning author. He was editor of the ''Ladies' Home Journal'' for 30 years (1889–1919). He ...

, as part of a project to improve modern house design. "A Home in a Prairie Town" and "A Small House with Lots of Room in it" appeared respectively in the February and July 1901 issues of the journal. Although neither of the affordable house plans was ever constructed, Wright received increased requests for similar designs in following years.[ Wright came to Buffalo and designed homes for three of the company's executives: the ]Darwin D. Martin House

The Darwin D. Martin House Complex is a historic house museum in Buffalo, New York. The property's buildings were designed by renowned architect Frank Lloyd Wright and built between 1903 and 1905. The house is considered to be one of the most imp ...

(1904), the William R. Heath House

The William R. Heath House was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, built from 1903 to 1905, and is located at 76 Soldiers Place in Buffalo, New York. It is built in the Prairie School architectural style. It is a contributing property in the Elmwoo ...

1905), and the Walter V. Davidson House

The Walter V. Davidson House, located at 57 Tillinghast Place in Buffalo, New York, was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright and built in 1908. It is an example of Wright's Prairie School architectural style. The house is a contributing property to ...

(1908). Other Wright houses considered to be masterpieces of the Prairie Style are the Frederick Robie House

The Frederick C. Robie House is a U.S. National Historic Landmark now on the campus of the University of Chicago in the South Side neighborhood of Hyde Park in Chicago, Illinois. Built between 1909 and 1910, the building was designed as a sing ...

in Chicago and the Avery and Queene Coonley House

The Avery Coonley House, also known as the Coonley House or Coonley Estate was designed by architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Constructed 1908–12, this is a residential estate of several buildings built on the banks of the Des Plaines River in Rivers ...

in Riverside, Illinois

Riverside is a suburban village in Cook County, Illinois, United States. A significant portion of the village is in the Riverside Landscape Architecture District, designated a National Historic Landmark in 1970. The population of the village was ...

. The Robie House, with its extended cantilever

A cantilever is a rigid structural element that extends horizontally and is supported at only one end. Typically it extends from a flat vertical surface such as a wall, to which it must be firmly attached. Like other structural elements, a cant ...

ed roof lines supported by a 110-foot-long (34 m) channel of steel, is the most dramatic. Its living and dining areas form virtually one uninterrupted space. With this and other buildings, included in the publication of the Wasmuth Portfolio

The ''Wasmuth Portfolio'' (1910) is a two-volume folio of 100 lithographs of the work of the American architect Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959).

Titled ', it was published in Germany in 1911 by the Berlin publisher Ernst Wasmuth, with an accom ...

(1910), Wright's work became known to European architects and had a profound influence on them after World War I.

Wright's residential designs of this era were known as "prairie houses" because the designs complemented the land around Chicago. Prairie Style houses often have a combination of these features: one or two stories with one-story projections, an open floor plan, low-pitched roofs with broad, overhanging eaves, strong horizontal lines, ribbons of windows (often casements), a prominent central chimney, built-in stylized cabinetry, and a wide use of natural materials—especially stone and wood.

By 1909, Wright had begun to reject the upper-middle-class Prairie Style single-family house

A stand-alone house (also called a single-detached dwelling, detached residence or detached house) is a free-standing residential building. It is sometimes referred to as a single-family home, as opposed to a multi-family residential dwellin ...

model, shifting his focus to a more democratic architecture. Wright went to Europe in 1909 with a portfolio of his work and presented it to Berlin publisher Ernst Wasmuth. ''Studies and Executed Buildings of Frank Lloyd Wright'', published in 1911, was the first major exposure of Wright's work in Europe. The work contained more than 100 lithographs of Wright's designs and is commonly known as the Wasmuth Portfolio

The ''Wasmuth Portfolio'' (1910) is a two-volume folio of 100 lithographs of the work of the American architect Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959).

Titled ', it was published in Germany in 1911 by the Berlin publisher Ernst Wasmuth, with an accom ...

.

Notable public works (1900–1917)

Wright designed the house of Cornell

Cornell University is a private statutory land-grant research university based in Ithaca, New York. It is a member of the Ivy League. Founded in 1865 by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, Cornell was founded with the intention to teach a ...

's chapter of Alpha Delta Phi literary society (1900), the Hillside Home School II

The Hillside Home School II was originally designed by architect Frank Lloyd Wright in 1901 for his aunts Jane and Ellen C. Lloyd Jones in the town of Wyoming, Wisconsin (south of the village of Spring Green). The Lloyd Jones sisters commissioned ...

(built for his aunts) in Spring Green, Wisconsin (1901) and the Unity Temple

Unity Temple is a Unitarian Universalist church in Oak Park, Illinois, and the home of the Unity Temple Unitarian Universalist Congregation. It was designed by the American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, and built between 1905 and 1908. Unity Te ...

(1905) in Oak Park, Illinois. As a lifelong Unitarian and member of Unity Temple, Wright offered his services to the congregation after their church burned down, working on the building from 1905 to 1909. Wright later said that Unity Temple was the edifice in which he ceased to be an architect of structure, and became an architect of space.

Some other early notable public buildings and projects in this era: the Larkin Administration Building

The Larkin Building was an early 20th century building. It was designed in 1903 by Frank Lloyd Wright and built in 1904-1906 for the Larkin Soap Company of Buffalo, New York. The five story dark red brick building used pink tinted mortar and ...

(1905); the Geneva Inn ( Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, 1911); the Midway Gardens

Midway Gardens (opened in 1914, demolished in 1929) was a 360,000 square feet indoor/outdoor entertainment facility in the Hyde Park neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago. It was designed by architect Frank Lloyd Wright, who also collaborate ...

(Chicago, Illinois, 1913); the Banff National Park Pavilion

The Banff National Park Pavilion, was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright and Francis Conroy Sullivan, one of Wright's only Canadian students. Designed in 1911, in the Prairie School style, construction began in 1913 and was completed the following yea ...

(Alberta

Alberta ( ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is part of Western Canada and is one of the three prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to the west, Saskatchewan to the east, the Northwest Ter ...

, Canada, 1914).

Designing in Japan (1917–1922)

While working in Japan, Frank Lloyd Wright left an impressive architectural heritage. The

While working in Japan, Frank Lloyd Wright left an impressive architectural heritage. The Imperial Hotel Imperial Hotel or Hotel Imperial may refer to:

Hotels Australia

* Imperial Hotel, Ravenswood, Queensland

* Imperial Hotel, York, Western Australia

Austria

* Hotel Imperial, Vienna

India

* The Imperial, New Delhi

Ireland

* Imperial Hotel, D ...

, completed in 1923, is the most important. Thanks to its solid foundations and steel construction, the hotel survived the Great Kanto Earthquake

Great may refer to: Descriptions or measurements

* Great, a relative measurement in physical space, see Size

* Greatness, being divine, majestic, superior, majestic, or transcendent

People

* List of people known as "the Great"

*Artel Great (born ...

almost unscathed. The hotel was damaged during the bombing of Tokyo

The was a series of firebombing air raids by the United States Army Air Force during the Pacific campaigns of World War II. Operation Meetinghouse, which was conducted on the night of 9–10 March 1945, is the single most destructive bombin ...

and by the subsequent US military occupation of it after World War II. As land in the center of Tokyo increased in value the hotel was deemed obsolete and was demolished in 1968 but the lobby was saved and later re-constructed at the Meiji Mura architecture museum in Nagoya in 1976.

Jiyu Gakuen was founded as a girls' school in 1921. The construction of the main building began in 1921 under Wright's direction and, after his departure, was continued by Endo. The school building, like the Imperial Hotel, is covered with Ōya stones.

The Yodoko Guesthouse (designed in 1918 and completed in 1924) was built as the summer villa for Tadzaemon Yamamura.

Frank Lloyd Wright's architecture had a strong influence on young Japanese architects. The Japanese architects Wright commissioned to carry out his designs were Arata Endo, Takehiko Okami, Taue Sasaki and Kameshiro Tsuchiura. Endo supervised the completion of the Imperial Hotel after Wright's departure in 1922 and also supervised the construction of the Jiyu Gakuen Girls' School and the Yodokō Guest House. Tsuchiura went on to create so-called "light" buildings, which had similarities to Wright's later work.

Jiyu Gakuen was founded as a girls' school in 1921. The construction of the main building began in 1921 under Wright's direction and, after his departure, was continued by Endo. The school building, like the Imperial Hotel, is covered with Ōya stones.

The Yodoko Guesthouse (designed in 1918 and completed in 1924) was built as the summer villa for Tadzaemon Yamamura.

Frank Lloyd Wright's architecture had a strong influence on young Japanese architects. The Japanese architects Wright commissioned to carry out his designs were Arata Endo, Takehiko Okami, Taue Sasaki and Kameshiro Tsuchiura. Endo supervised the completion of the Imperial Hotel after Wright's departure in 1922 and also supervised the construction of the Jiyu Gakuen Girls' School and the Yodokō Guest House. Tsuchiura went on to create so-called "light" buildings, which had similarities to Wright's later work.

Textile concrete block system

In the early 1920s, Wright designed a "

In the early 1920s, Wright designed a "textile

Textile is an umbrella term that includes various fiber-based materials, including fibers, yarns, filaments, threads, different fabric types, etc. At first, the word "textiles" only referred to woven fabrics. However, weaving is not the ...

" concrete block system. The system of precast blocks, reinforced by an internal system of bars, enabled "fabrication as infinite in color, texture, and variety as in that rug."Millard House

Millard House, also known as La Miniatura, is a textile block house designed by Frank Lloyd Wright and built in 1923 in Pasadena, California. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976.

Wright's textile block houses

Th ...

in Pasadena, California, in 1923. Typically Wrightian is the joining of the structure to its site by a series of terraces that reach out into and reorder the landscape, making it an integral part of the architect's vision.Ennis House

The Ennis House is a residential dwelling in the Los Feliz neighborhood of Los Angeles, California, United States, south of Griffith Park. The home was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright for Charles and Mabel Ennis in 1923 and was built in 1924.

Fol ...

and the Samuel Freeman House

The Samuel Freeman House (also known as the Samuel and Harriet Freeman House) is a Frank Lloyd Wright house in the Hollywood Hills of Los Angeles, California built in 1923. The house was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1 ...

(both 1923), Wright had further opportunities to test the limits of the textile block system, including limited use in the Arizona Biltmore Hotel

The Arizona Biltmore Hotel is a resort located in Phoenix near 24th Street and Camelback Road. It is part of Hilton Hotels' Waldorf Astoria Hotels and Resorts. It was featured on the Travel Channel show ''Great Hotels.'' The Arizona Biltmore h ...

in 1927. The Ennis house is often used in films, television, and print media to represent the future.Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright Jr. (March 31, 1890 – May 31, 1978), commonly known as Lloyd Wright, was an American architect, active primarily in Los Angeles and Southern California. He was a landscape architect for various Los Angeles projects (192 ...

, supervised construction for the Storer, Freeman, and Ennis Houses. Architectural historian Thomas Hines has suggested that Lloyd's contribution to these projects is often overlooked.

After World War II, Wright updated the concrete block system, calling it the "Usonian Automatic" system, resulting in the construction of several notable homes. As he explained in ''The Natural House'' (1954), "The original blocks are made on the site by ramming concrete into wood or metal wrap-around forms, with one outside face (which may be pattered), and one rear or inside face, generally coffer

A coffer (or coffering) in architecture is a series of sunken panels in the shape of a square, rectangle, or octagon in a ceiling, soffit or vault.

A series of these sunken panels was often used as decoration for a ceiling or a vault, also ...

ed, for lightness."

Midlife problems

Family turmoil

In 1903, while Wright was designing a house for

In 1903, while Wright was designing a house for Edwin Cheney

Edwin Henry Cheney (June 13, 1869 - December 18, 1942) was an American electrical engineer from Oak Park, Illinois, United States.

Edwin was the son of James Wilson Cheney (b. August 20, 1841) and Armilla Armanda (b. ca. 1846), daughter of Linus ...

(a neighbor in Oak Park), he became enamored with Cheney's wife, Mamah. Mamah Borthwick Cheney was a modern woman with interests outside the home. She was an early feminist, and Wright viewed her as his intellectual equal. Their relationship became the talk of the town; they often could be seen taking rides in Wright's automobile through Oak Park. In 1909, Wright and Mamah Cheney met up in Europe, leaving their spouses and children behind. Wright remained in Europe for almost a year, first in Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany Regions of Italy, region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilan ...

, Italy (where he lived with his eldest son Lloyd) and, later, in Fiesole, Italy, where he lived with Mamah. During this time, Edwin Cheney granted Mamah a divorce, though Kitty still refused to grant one to her husband. After Wright returned to the United States in October 1910, he persuaded his mother to buy land for him in Spring Green, Wisconsin. The land, bought on April 10, 1911, was adjacent to land held by his mother's family, the Lloyd-Joneses. Wright began to build himself a new home, which he called , by May 1911. The recurring theme of also came from his mother's side: in Welsh mythology

Welsh mythology (Welsh: ''Mytholeg Cymru'') consists of both folk traditions developed in Wales, and traditions developed by the Celtic Britons elsewhere before the end of the first millennium. As in most of the predominantly oral societies Celti ...

was a poet, magician, and priest. The family motto, "'" ("The Truth Against the World"), was taken from the Welsh poet , who also had a son named Taliesin. The motto is still used today as the cry of the druids and chief bard of the in Wales.

Tragedy at Taliesin

On August 15, 1914, while Wright was working in Chicago, a servant (Julian Carlton) set fire to the living quarters of Taliesin and then murdered seven people with an axe as the fire burned.hydrochloric acid

Hydrochloric acid, also known as muriatic acid, is an aqueous solution of hydrogen chloride. It is a colorless solution with a distinctive pungent smell. It is classified as a strong acid

Acid strength is the tendency of an acid, symbol ...

immediately following the attack in an attempt to kill himself.lynched

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged transgressor, punish a convicted transgressor, or intimidate people. It can also be an ex ...

on the spot, but was taken to the Dodgeville jail.

Divorces

In 1922, Kitty Wright finally granted Wright a divorce. Under the terms of the divorce, Wright was required to wait one year before he could marry his then-mistress, Maude "Miriam" Noel. In 1923, Wright's mother, Anna (Lloyd Jones) Wright, died. Wright wed Miriam Noel in November 1923, but her addiction to morphine

Morphine is a strong opiate that is found naturally in opium, a dark brown resin in poppies (''Papaver somniferum''). It is mainly used as a pain medication, and is also commonly used recreationally, or to make other illicit opioids. T ...

led to the failure of the marriage in less than one year. In 1924, after the separation, but while still married, Wright met Olga (Olgivanna) Lazovich Hinzenburg. They moved in together at Taliesin in 1925, and soon after Olgivanna became pregnant. Their daughter, Iovanna, was born on December 3, 1925.

On April 20, 1925, another fire destroyed the bungalow at Taliesin. Crossed wires from a newly installed telephone system were deemed to be responsible for the blaze, which destroyed a collection of Japanese prints that Wright estimated to be worth $250,000 to $500,000 ($ to $ in ). Wright rebuilt the living quarters, naming the home " Taliesin III".

In 1926, Olga's ex-husband, Vlademar Hinzenburg, sought custody of his daughter, Svetlana. In October 1926, Wright and Olgivanna were accused of violating the Mann Act

The White-Slave Traffic Act, also called the Mann Act, is a United States federal law, passed June 25, 1910 (ch. 395, ; ''codified as amended at'' ). It is named after Congressman James Robert Mann of Illinois.

In its original form the act mad ...

and arrested in Tonka Bay, Minnesota

Tonka Bay is a city in Hennepin County, Minnesota, United States. It is located on Lake Minnetonka between the upper and lower lakes. It gained some popularity in the 1880s and 1890s as a summer lake resort. The population of Tonka Bay was 1,475 ...

. The charges were later dropped.

Wright and Miriam Noel's divorce was finalized in 1927. Wright was again required to wait for one year before remarrying. Wright and Olgivanna married in 1928.

Later career

Taliesin Fellowship

In 1932, Wright and his wife Olgivanna put out a call for students to come to Taliesin to study and work under Wright while they learned architecture and spiritual development. Olgivanna Wright had been a student of G. I. Gurdjieff who had previously established a similar school. Twenty-three came to live and work that year, including John (Jack) H. Howe, who would become Wright's chief draftsman. A total of 625 people joined The Fellowship in Wright's lifetime. The Fellowship was a source of workers for Wright's later projects, including: Fallingwater; The Johnson Wax Headquarters; and The Guggenheim Museum in New York City.

Considerable controversy exists over the living conditions and education of the fellows. Wright was reputedly a difficult person to work with. One apprentice wrote: "He is devoid of consideration and has a blind spot regarding others' qualities. Yet I believe, that a year in his studio would be worth any sacrifice." The Fellowship evolved into The School of Architecture at Taliesin

The School of Architecture is a private architecture school in Paradise Valley, Arizona. It was founded in 1986 as an accredited school by surviving members of the Taliesin Fellowship. The school offers a Master of Architecture program that focuse ...

which was an accredited school until it closed under acrimonious circumstances in 2020. In June 2020 the school moved to the Cosanti Foundation, which it had worked with in the past.

Usonian Houses

Wright is responsible for a series of concepts of suburban development united under the term

Wright is responsible for a series of concepts of suburban development united under the term Broadacre City

Broadacre City was an urban or suburban development concept proposed by Frank Lloyd Wright throughout most of his lifetime. He presented the idea in his book ''The Disappearing City'' in 1932. A few years later he unveiled a very detailed twelve- ...

. He proposed the idea in his book ''The Disappearing City'' in 1932 and unveiled a model of this community of the future, showing it in several venues in the following years. Concurrent with the development of Broadacre City, also referred to as Usonia, Wright conceived a new type of dwelling that came to be known as the Usonia

Usonia () is a word that was used by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright to refer to the United States in general (in preference to ''America''), and more specifically to his vision for the landscape of the country, including the planning of ...

n House. Although an early version of the form can be seen in the Malcolm Willey House

The Malcolm Willey House is located in Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States. It was designed by the American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, and built in 1934. Wright named the house "Gardenwall".

Malcolm Willey was an administrator at the Univ ...

(1934) in Minneapolis, the Usonian ideal emerged most completely in the Herbert and Katherine Jacobs First House

Herbert and Katherine Jacobs First House, commonly referred to as Jacobs I, is a single family home located at 441 Toepfer Avenue in Madison, Wisconsin, United States. Designed by noted American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, it was constructed i ...

(1937) in Madison, Wisconsin. Designed on a gridded concrete slab that integrated the house's radiant heating system, the house featured new approaches to construction, including walls composed of a "sandwich" of wood siding, plywood cores and building paper—a significant change from typically framed walls. Usonian houses commonly featured flat roofs and were usually constructed without basements or attics, all features that Wright had been promoting since the early 20th century.

Usonian houses were Wright's response to the transformation of domestic life that occurred in the early 20th century when servants had become less prominent or completely absent from most American households. By developing homes with progressively more open plans, Wright allotted the woman of the house a "workspace", as he often called the kitchen, where she could keep track of and be available for the children and/or guests in the dining room. As in the Prairie Houses, Usonian living areas had a fireplace as a point of focus. Bedrooms, typically isolated and relatively small, encouraged the family to gather in the main living areas. The conception of spaces instead of rooms was a development of the Prairie ideal. The built-in furnishings related to the Arts and Crafts movement's principles that influenced Wright's early work. Spatially and in terms of their construction, the Usonian houses represented a new model for independent living and allowed dozens of clients to live in a Wright-designed house at relatively low cost. His Usonian homes set a new style for suburban design that influenced countless postwar developers. Many features of modern American homes date back to Wright: open plans, slab-on-grade foundations, and simplified construction techniques that allowed more mechanization and efficiency in building.

Significant later works

''

''Fallingwater

Fallingwater is a house designed by the architect Frank Lloyd Wright in 1935 in the Laurel Highlands of southwest Pennsylvania, about southeast of Pittsburgh in the United States. It is built partly over a waterfall on Bear Run in the Mill R ...

'', one of Wright's most famous private residences (completed 1937), was built for Mr. and Mrs. Edgar J. Kaufmann, Sr., at Mill Run, Pennsylvania. Constructed over a 30-foot waterfall, it was designed according to Wright's desire to place the occupants close to the natural surroundings. The house was intended to be more of a family getaway, rather than a live-in home.limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms whe ...

for all verticals and concrete for the horizontals. The house cost $155,000, including the architect's fee of $8,000. It was one of Wright's most expensive pieces.Taliesin West

Taliesin West was architect Frank Lloyd Wright's winter home and studio in the desert from 1937 until his death in 1959 at the age of 91. Today it is the headquarters of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation.

Open to the public for tours, Taliesin ...

, Wright's winter home and studio complex in Scottsdale, Arizona

, settlement_type = City

, named_for = Winfield Scott

, image_skyline =

, image_seal = Seal of Scottsdale (Arizona).svg

, image_blank_emblem = City of Scottsdale Script Logo.svg

, nick ...

, was a laboratory for Wright from 1937 to his death in 1959. It is now the home of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation

Taliesin West was architect Frank Lloyd Wright's winter home and studio in the desert from 1937 until his death in 1959 at the age of 91. Today it is the headquarters of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation.

Open to the public for tours, Taliesin ...

.

The design and construction of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, often referred to as The Guggenheim, is an art museum at 1071 Fifth Avenue on the corner of East 89th Street on the Upper East Side of Manhattan in New York City. It is the permanent home of a continuously exp ...

in New York City occupied Wright from 1943 until 1959 and is probably his most recognized masterpiece. The building's unique central geometry was meant to allow visitors to easily experience Guggenheim's collection of nonobjective geometric paintings by taking an elevator to the top level and then viewing artworks by walking down the slowly descending, central spiral ramp.

The only realized skyscraper designed by Wright is the

The only realized skyscraper designed by Wright is the Price Tower

The Price Tower is a nineteen-story, 221-foot-high tower at 510 South Dewey Avenue in Bartlesville, Oklahoma. It was built in 1956 to a design by Frank Lloyd Wright. It is the only realized skyscraper by Wright, and is one of only two vertical ...

, a 19-story tower in Bartlesville, Oklahoma

Bartlesville is a city mostly in Washington County in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. The population was 37,290 at the 2020 census. Bartlesville is north of Tulsa and south of the Kansas border. It is the county seat of Washington County. The Ca ...

. It is also one of the two existing vertically oriented Wright structures (the other is the S.C. Johnson Wax Research Tower

Johnson Wax Headquarters is the world headquarters and administration building of S. C. Johnson & Son in Racine, Wisconsin. Designed by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright for the company's president, Herbert F. "Hib" Johnson, the building was ...

in Racine, Wisconsin

Racine ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Racine County, Wisconsin, United States. It is located on the shore of Lake Michigan at the mouth of the Root River. Racine is situated 22 miles (35 km) south of Milwaukee and approximately 60 ...

). The Price Tower was commissioned by Harold C. Price of the H. C. Price Company, a local oil pipeline and chemical firm. On March 29, 2007, Price Tower was designated a National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the United States government for its outstanding historical significance. Only some 2,500 (~3%) of over 90,000 places listed ...

by the United States Department of the Interior

The United States Department of the Interior (DOI) is one of the executive departments of the U.S. federal government headquartered at the Main Interior Building, located at 1849 C Street NW in Washington, D.C. It is responsible for the ma ...

, one of only 20 such properties in Oklahoma.

Monona Terrace

Monona Terrace (officially the Monona Terrace Community and Convention Center) is a convention center on the shores of Lake Monona in Madison, Wisconsin.

Controversy

Originally designed by Wisconsin native Frank Lloyd Wright, it was first propo ...

, originally designed in 1937 as municipal offices for Madison, Wisconsin, was completed in 1997 on the original site, using a variation of Wright's final design for the exterior, with the interior design altered by its new purpose as a convention center. The "as-built" design was carried out by Wright's apprentice Tony Puttnam. Monona Terrace was accompanied by controversy throughout the 60 years between the original design and the completion of the structure.

Florida Southern College

Florida Southern College (Florida Southern, Southern or FSC) is a private college in Lakeland, Florida. In 2019, the student population at FSC consisted of 3,073 students along with 130 full-time faculty members. The college offers 50 undergradu ...

, located in Lakeland, Florida

Lakeland is the most populous city in Polk County, Florida, part of the Tampa Bay Area, located along Interstate 4 east of Tampa. According to the 2020 U.S. Census Bureau release, the city had a population of 112,641. Lakeland is a principal ci ...

, constructed 12 (out of 18 planned) Frank Lloyd Wright buildings between 1941 and 1958 as part of the Child of the Sun

Child of the Sun is a collection of buildings designed by Frank Lloyd Wright on the campus of the Florida Southern College in Lakeland, Florida. The twelve original buildings were constructed between 1941 and 1958. Another of Wright's designs, a ...

project. It is the world's largest single-site collection of Frank Lloyd Wright architecture.

Personal style and concepts

Design elements

His Prairie houses use themed, coordinated design elements (often based on plant forms) that are repeated in windows, carpets, and other fittings. He made innovative use of new building materials such as

His Prairie houses use themed, coordinated design elements (often based on plant forms) that are repeated in windows, carpets, and other fittings. He made innovative use of new building materials such as precast concrete

Precast concrete is a construction product produced by casting concrete in a reusable mold or "form" which is then cured in a controlled environment, transported to the construction site and maneuvered into place; examples include precast bea ...

blocks, glass bricks, and zinc came

A came is a divider bar used between small pieces of glass to make a larger glazing panel.

There are two kinds of came: the H-shaped sections that hold two pieces together and the U-shaped sections that are used for the borders. Cames are mostl ...

s (instead of the traditional lead) for his leadlight windows, and he famously used Pyrex

Pyrex (trademarked as ''PYREX'' and ''pyrex'') is a brand introduced by Corning Inc. in 1915 for a line of clear, low-thermal-expansion borosilicate glass used for laboratory glassware and kitchenware. It was later expanded to include kitchenwa ...

glass tubing as a major element in the Johnson Wax Headquarters

Johnson Wax Headquarters is the world headquarters and administration building of S. C. Johnson & Son in Racine, Wisconsin. Designed by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright for the company's president, Herbert F. "Hib" Johnson, the building was c ...

. Wright was also one of the first architects to design and install custom-made electric light fittings, including some of the first electric floor lamps, and his very early use of the then-novel spherical glass lampshade (a design previously not possible due to the physical restrictions of gas lighting). In 1897, Wright received a patent for "Prism Glass Tiles" that were used in storefronts to direct light toward the interior. Wright fully embraced glass in his designs and found that it fit well into his philosophy of organic architecture

Organic architecture is a philosophy of architecture which promotes harmony between human habitation and the natural world. This is achieved through design approaches that aim to be sympathetic and well-integrated with a site, so buildings, furn ...

. According to Wright's organic theory, all components of the building should appear unified, as though they belong together. Nothing should be attached to it without considering the effect on the whole. To unify the house to its site, Wright often used large expanses of glass to blur the boundary between the indoors and outdoors.

Influences and collaborations

Wright strongly believed in individualism and did not affiliate with the

Wright strongly believed in individualism and did not affiliate with the American Institute of Architects

The American Institute of Architects (AIA) is a professional organization for architects in the United States. Headquartered in Washington, D.C., the AIA offers education, government advocacy, community redevelopment, and public outreach to su ...

during his career, going so far as to call the organization "a harbor of refuge for the incompetent," and "a form of refined gangsterism". When an associate referred to him as "an old amateur" Wright confirmed, "I am the oldest."Louis Sullivan

Louis Henry Sullivan (September 3, 1856 – April 14, 1924) was an American architect, and has been called a "father of skyscrapers" and "father of modernism". He was an influential architect of the Chicago School, a mentor to Frank Lloy ...

, whom he considered to be his ''Lieber Meister'' (dear master)

# Nature, particularly shapes/forms and colors/patterns of plant life

# Music (his favorite composer was Ludwig van Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classical ...

)

# Japanese art, prints and buildings

# Froebel Gifts

The Froebel gifts (german: Fröbelgaben) are educational play materials for young children, originally designed by Friedrich Fröbel for the first kindergarten at Bad Blankenburg. Playing with Froebel gifts, singing, dancing, and growing plants we ...

He routinely claimed the work of architects and architectural designers who were his employees as his own designs, and that the rest of the Prairie School architects were merely his followers, imitators, and subordinates. As with any architect, though, Wright worked in a collaborative process and drew his ideas from the work of others. In his earlier days, Wright worked with some of the top architects of the Chicago School, including Sullivan. In his Prairie School days, Wright's office was populated by many talented architects, including William Eugene Drummond

William Eugene Drummond (March 28, 1876 – September 13, 1948) was a Chicago Prairie School architect.

Early years and education

He was born in Newark, New Jersey, the son of carpenter and cabinet maker Eugene Drummond and his wife Ida Marietta ...

, John Van Bergen

John Shellette Van Bergen (October 2, 1885 – December 20, 1969) was an American architect born in Oak Park, Illinois. Van Bergen started his architectural career as an apprentice draftsman in 1907. In 1909 he went to work for Frank Lloyd Wrigh ...

, Isabel Roberts

Isabel Roberts (March 1871 – December 27, 1955) was a Prairie School figure, member of the architectural design team in the Oak Park Studio of Frank Lloyd Wright and partner with Ida Annah Ryan in the Orlando, Florida architecture firm, "R ...

, Francis Barry Byrne

Francis Barry Byrne (December 19, 1883 – December 18, 1967) was a member of the group of architects known as the Prairie School. After the demise of the Prairie School, about 1914 to 1916, Byrne continued as a successful architect by dev ...

, Albert McArthur, Marion Mahony Griffin

Marion Mahony Griffin (; February 14, 1871 – August 10, 1961) was an American architect and artist. She was one of the first licensed female architects in the world, and is considered an original member of the Prairie School. Her work in ...

, and Walter Burley Griffin

Walter Burley Griffin (November 24, 1876February 11, 1937) was an American architect and landscape architect. He is known for designing Canberra, Australia's capital city and the New South Wales towns of Griffith and Leeton. He has been cr ...

. The Czech-born architect Antonin Raymond

Antonin Raymond (or cs, Antonín Raymond), born as Antonín Reimann (10 May 1888 – 25 October 1976)"Deaths Elsewhere", ''Miami Herald'', 30 October 1976, p. 10 was a Czech American architect. Raymond was born and studied in Bohemia (now part ...

worked for Wright at Taliesin and led the construction of the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. He subsequently stayed in Japan and opened his own practice. Rudolf Schindler also worked for Wright on the Imperial Hotel and his own work is often credited as influencing Wright's Usonian houses. Schindler's friend Richard Neutra also worked briefly for Wright and became an internationally successful architect. In the Taliesin

Taliesin ( , ; 6th century AD) was an early Brittonic poet of Sub-Roman Britain whose work has possibly survived in a Middle Welsh manuscript, the '' Book of Taliesin''. Taliesin was a renowned bard who is believed to have sung at the courts ...

days, Wright employed many architects and artists who later become notable, such as Aaron Green, John Lautner

John Edward Lautner (16 July 1911 – 24 October 1994) was an American architect. Following an apprenticeship in the mid-1930s with the Taliesin Fellowship led by Frank Lloyd Wright, Lautner opened his own practice in 1938, where he worked for th ...

, E. Fay Jones

Euine Fay Jones (January 31, 1921 – August 30, 2004) was an American architect and designer. An apprentice of Frank Lloyd Wright during his professional career, Jones is the only one of Wright's disciples to have received the AIA Gold Medal (19 ...

, Henry Klumb

Heinrich Klumb (1905 in Cologne, Germany – 1984 in San Juan, Puerto Rico) was a German architect who worked in Puerto Rico during the mid 20th Century.

Education and early life

Klumb was born in Cologne, Germany, in 1905. An honors graduate ...

, William Bernoudy

William Adair Bernoudy (1910–1988) was an American architect.

Bernoudy was born in St. Louis where he attended the Washington University in St. Louis School of Architecture (now Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts. He studied under Frank Llo ...

, and Paolo Soleri

Paolo Soleri (21 June 1919 – 9 April 2013) was an Italian-born American architect. He established the educational Cosanti Foundation and Arcosanti. Soleri was a lecturer in the College of Architecture at Arizona State University and a National ...

.

Community planning

Frank Lloyd Wright was interested in site and community planning throughout his career. His commissions and theories on urban design began as early as 1900 and continued until his death. He had 41 commissions on the scale of community planning or urban design.

His thoughts on suburban design started in 1900 with a proposed subdivision layout for Charles E. Roberts

Charles E. Roberts (March 13, 1843 – March 1934) was an American engineer, inventor and an important early client and patron of Frank Lloyd Wright. In 1896, Wright remodeled Robert's house in Oak Park.

Personal life

Charles E Roberts was b ...

entitled the "Quadruple Block Plan". This design strayed from traditional suburban lot layouts and set houses on small square blocks of four equal-sized lots surrounded on all sides by roads instead of straight rows of houses on parallel streets. The houses, which used the same design as published in "A Home in a Prairie Town" from the ''Ladies' Home Journal'', were set toward the center of the block to maximize the yard space and included private space in the center. This also allowed for far more interesting views from each house. Although this plan was never realized, Wright published the design in the ''Wasmuth Portfolio'' in 1910.

The more ambitious designs of entire communities were exemplified by his entry into the City Club of Chicago Land Development Competition in 1913. The contest was for the development of a suburban quarter section. This design expanded on the Quadruple Block Plan and included several social levels. The design shows the placement of the upscale homes in the most desirable areas and the blue collar

A blue-collar worker is a working class person who performs manual labor. Blue-collar work may involve skilled or unskilled labor. The type of work may involving manufacturing, warehousing, mining, excavation, electricity generation and power ...

homes and apartments separated by parks and common spaces. The design also included all the amenities of a small city: schools, museums, markets, etc. This view of decentralization was later reinforced by theoretical Broadacre City

Broadacre City was an urban or suburban development concept proposed by Frank Lloyd Wright throughout most of his lifetime. He presented the idea in his book ''The Disappearing City'' in 1932. A few years later he unveiled a very detailed twelve- ...

design. The philosophy behind his community planning was decentralization. The new development must be away from the cities. In this decentralized America, all services and facilities could coexist "factories side by side with farm and home".

Notable community planning designs:

* 1900–03 – Quadruple Block Plan, 24 homes in Oak Park, Illinois (unbuilt);

* 1909 – Como Orchard Summer Colony Como Orchards Club, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1909 and located near Darby, Montana, was part of a land development scheme (Como Orchards) inspired by the western railroad expansion.

By 1909 three rail lines ran to Missoula, Montana, and wh ...

, town site development for new town in the Bitterroot Valley, Montana;

* 1913 – Chicago Land Development competition, suburban Chicago quarter section;

* 1934–59 – Broadacre City