Francis Marbury on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Francis Marbury (sometimes spelled Merbury) (1555–1611) was a Cambridge-educated English cleric,

As a young man Marbury was considered to be a "hothead" and felt strongly that the clergy should be well educated, and clashed with his superiors on this issue. He spent time preaching at

As a young man Marbury was considered to be a "hothead" and felt strongly that the clergy should be well educated, and clashed with his superiors on this issue. He spent time preaching at

In 1590 Marbury once again felt emboldened to speak out against his superiors, denouncing the Church of England for selecting poorly educated bishops and poorly trained ministers. The Bishop of Lincoln, calling him an "impudent Puritan," removed him from preaching and teaching, and put him under house arrest. On 15 October 1590 Marbury wrote a letter to the statesman

In 1590 Marbury once again felt emboldened to speak out against his superiors, denouncing the Church of England for selecting poorly educated bishops and poorly trained ministers. The Bishop of Lincoln, calling him an "impudent Puritan," removed him from preaching and teaching, and put him under house arrest. On 15 October 1590 Marbury wrote a letter to the statesman

Marbury was said to have 20 children, but only 18 have been identified, three with his first wife, Elizabeth Moore, and 15 with his second wife, Bridget Dryden. The three children from his first marriage were all girls, Mary (c. 1584–1585), Susan (baptised 12 September 1585; married a Mr Twyford) and Elizabeth (c. 1587–1601). His children with Bridget Dryden were Mary (born c. 1588), John (baptised 15 February 1589/90), Anne (baptised 20 July 1591), Bridget (baptised 8 May 1593; buried 15 October 1598), Francis (baptised 20 October 1594), Emme (baptised 21 December 1595), Erasmus (baptised 15 February 1596/7), Anthony (baptised 11 September 1598; buried 9 April 1601), Bridget (baptised 25 November 1599), Jeremuth (or Jeremoth, baptised 31 March 1601), Daniel (baptised 14 September 1602), Elizabeth (baptised 20 January 1604/5), Thomas (born c. 1606?), Anthony (born c. 1608), and

Marbury was said to have 20 children, but only 18 have been identified, three with his first wife, Elizabeth Moore, and 15 with his second wife, Bridget Dryden. The three children from his first marriage were all girls, Mary (c. 1584–1585), Susan (baptised 12 September 1585; married a Mr Twyford) and Elizabeth (c. 1587–1601). His children with Bridget Dryden were Mary (born c. 1588), John (baptised 15 February 1589/90), Anne (baptised 20 July 1591), Bridget (baptised 8 May 1593; buried 15 October 1598), Francis (baptised 20 October 1594), Emme (baptised 21 December 1595), Erasmus (baptised 15 February 1596/7), Anthony (baptised 11 September 1598; buried 9 April 1601), Bridget (baptised 25 November 1599), Jeremuth (or Jeremoth, baptised 31 March 1601), Daniel (baptised 14 September 1602), Elizabeth (baptised 20 January 1604/5), Thomas (born c. 1606?), Anthony (born c. 1608), and

Rootsweb biography History of Protestant Nonconformity in England

{{DEFAULTSORT:Marbury, Francis 1555 births 1611 deaths 16th-century English educators 17th-century English educators 16th-century English Puritan ministers 17th-century English Puritan ministers 16th-century English writers 16th-century male writers 17th-century English writers 17th-century English male writers Alumni of Christ's College, Cambridge English Renaissance dramatists 16th-century English dramatists and playwrights

schoolmaster

The word schoolmaster, or simply master, refers to a male school teacher. This usage survives in British independent schools, both secondary and preparatory, and a few Indian boarding schools (such as The Doon School) that were modelled after B ...

and playwright. He is best known for being the father of Anne Hutchinson

Anne Hutchinson (née Marbury; July 1591 – August 1643) was a Puritan spiritual advisor, religious reformer, and an important participant in the Antinomian Controversy which shook the infant Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638. Her ...

, considered the most famous English woman in colonial America, and Katherine Marbury Scott

Katherine Marbury Scott (born approx.1607-1610, died 1687) was a Quaker advocate and colonist of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Like her older sister, Anne Hutchinson, she was persecuted by the Puritans when her open opposition to Puritan authoritie ...

, the first known woman to convert to Quakerism in the United States.

Born in 1555, Marbury was the son of William Marbury, a lawyer from Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (abbreviated Lincs.) is a county in the East Midlands of England, with a long coastline on the North Sea to the east. It borders Norfolk to the south-east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south-west, Leicestershire ...

, and Agnes Lenton. Young Marbury attended Christ's College, Cambridge

Christ's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college includes the Master, the Fellows of the College, and about 450 undergraduate and 170 graduate students. The college was founded by William Byngham in 1437 as ...

. He is not known to have graduated, though he was ordained as a deacon in the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

in January 1578. He was given a ministry position in Northampton and almost immediately came into conflict with the bishop. Taking a position commonly used by Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

s, he criticised the church leadership for staffing the parish churches with poorly trained clergy and for tolerating poorly trained bishops. After serving two short jail terms, he was ordered not to return to Northampton, but disregarded the mandate and was subsequently brought before the Bishop of London, John Aylmer, for trial in November 1578. During the examination, Aylmer called Marbury an ass, an idiot and a fool, and sentenced him to Marshalsea

The Marshalsea (1373–1842) was a notorious prison in Southwark, just south of the River Thames. Although it housed a variety of prisoners, including men accused of crimes at sea and political figures charged with sedition, it became known, in ...

prison for his impudence.

After two years in prison Marbury was considered sufficiently reformed to preach again and was sent to Alford in Lincolnshire, close to his ancestral home. Here he married and began a family, but again felt emboldened to speak out against the church leadership and was put under house arrest. Following a time without employment, he became desperate, writing letters to prominent officials, and was eventually allowed to resume preaching. Making good on his promise to curb his tongue, he preached uneventfully in Alford and with a growing prominence was rewarded with a position in London in 1605. He was given a second parish in 1608, which was exchanged for another closer to home a year later. He died unexpectedly in 1611 at the age of 55. With two wives Marbury had 18 children, three of whom matriculated at Brasenose College, Oxford

Brasenose College (BNC) is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. It began as Brasenose Hall in the 13th century, before being founded as a college in 1509. The library and chapel were added in the mi ...

, and one of whom, Anne, became a puritan dissident in the Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as the ...

who had a leading role in the colony's Antinomian Controversy

The Antinomian Controversy, also known as the Free Grace Controversy, was a religious and political conflict in the Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638. It pitted most of the colony's ministers and magistrates against some adherents of ...

.

Early life

Francis Marbury, born in London and baptised on 27 October 1555, was one of six children of William Marbury (1524–1581), and the youngest of three sons. His father, who possibly attendedPembroke College, Cambridge

Pembroke College (officially "The Master, Fellows and Scholars of the College or Hall of Valence-Mary") is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge, England. The college is the third-oldest college of the university and has over 700 ...

in 1544, was a lawyer in Lincolnshire, a member of the Middle Temple

The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, commonly known simply as Middle Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court exclusively entitled to call their members to the English Bar as barristers, the others being the Inner Temple, Gray's Inn an ...

, where he was admitted "specially ... at the instance of Mr. Francis Barnades" in May 1551, and still active until 1573; he was elected Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

for Newport Iuxta Launceston

Newport was a rotten borough situated in Cornwall. It is now the suburb of Newport within the town of Launceston, which was itself also a parliamentary borough at the same period. It is also referred to as Newport Iuxta Launceston, to distingui ...

in 1572. His mother was Agnes, the daughter of John Lenton of Old Wynkill, Staffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation Staffs.) is a landlocked county in the West Midlands region of England. It borders Cheshire to the northwest, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to the east, Warwickshire to the southeast, the West Midlands Cou ...

according to historian John Champlin, but genealogist Meredith Colket suggests that Lenton was from Aldwinkle

Aldwincle (sometimes Aldwinkle or Aldwinckle) is a village and civil parish in North Northamptonshire, with a population at the time of the 2011 census of 322. It stands by a bend in the River Nene, to the north of Thrapston. The name of the v ...

in Northamptonshire, which is much closer to where the Marburys lived. Marbury was likely educated in London, perhaps at St Paul's School, and he became well grounded in Latin as well as learning some Greek. Though he was born and raised in London, his family maintained close ties with Lincolnshire. His older brother, Edward, was knighted there in 1603, and died in 1605 as the High Sheriff of Lincolnshire

This is a list of High Sheriffs of Lincolnshire.

The High Sheriff is the oldest secular office under the Crown. Formerly the High Sheriff was the principal law enforcement officer in the county but over the centuries most of the responsibilitie ...

.

Marbury matriculated at Christ's College, Cambridge

Christ's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college includes the Master, the Fellows of the College, and about 450 undergraduate and 170 graduate students. The college was founded by William Byngham in 1437 as ...

in 1571, but is not known to have graduated. He was ordained deacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions. Major Christian churches, such as the Catholic Churc ...

by Edmund Scambler

Edmund Scambler (c. 1520 – 7 May 1594) was an English bishop.

Life

He was born at Gressingham, and was educated at Peterhouse, Cambridge, Queens' College, Cambridge and Jesus College, Cambridge, graduating B.A. in 1542.

Under Mary I of Engl ...

, Bishop of Peterborough, on 7 January 1578. Though he was young when he became a deacon, he was not ordained as priest until 1605. While Marbury was of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

, he had decidedly Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

views. Not all English subjects thought that Queen Elizabeth had gone far enough to cleanse the English Church of Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

rites and governance, or to ensure that its ministers were capable of saving souls through powerful preaching. The most vocal of these critics were the Puritans, and Marbury was among the most radical of the non-conforming Puritans, the Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

s. These more extreme non-conformists wanted to "abolish all the pomp and ceremony of the Church of England and remodel its government according to what they thought was the Bible's simple, consensual pattern." To do this, they would eliminate bishops appointed by the monarchs, and introduce sincere Christians to choose the church's elders (or governors). The church leadership would then consist of two ministers, one a teacher in charge of doctrine, and the other a pastor in charge of people's souls, and also include a ruling lay leader.

1578 trial

As a young man Marbury was considered to be a "hothead" and felt strongly that the clergy should be well educated, and clashed with his superiors on this issue. He spent time preaching at

As a young man Marbury was considered to be a "hothead" and felt strongly that the clergy should be well educated, and clashed with his superiors on this issue. He spent time preaching at Northampton

Northampton () is a market town and civil parish in the East Midlands of England, on the River Nene, north-west of London and south-east of Birmingham. The county town of Northamptonshire, Northampton is one of the largest towns in England; ...

, but soon came into conflict with the bishop's chancellor, Dr James Ellis, who was on a mission to suppress any nonconforming clergy. After two short imprisonments, Marbury was directed to leave Northampton and not return. He disregarded this order, and was then brought to trial in the consistory court

A consistory court is a type of ecclesiastical court, especially within the Church of England where they were originally established pursuant to a charter of King William the Conqueror, and still exist today, although since about the middle of th ...

of St Paul's in London before the high commission on 5 November 1578. Here he was examined by the Bishop of London

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

, John Aylmer, and by Sir Owen Hopton

Sir Owen Hopton (c. 1519 – 1595) was an English provincial landowner, administrator and MP, and was Lieutenant of the Tower of London from c. 1570 to 1590.

Early career

Owen Hopton was the eldest son and heir of Sir Arthur Hopton of Cockf ...

, Dr Lewis, and Archdeacon John Mullins. Marbury made a transcript of this trial from memory and used it to educate and amuse his children, he being the hero, and the Bishop being portrayed as somewhat of a buffoon, and the transcript can be found in Benjamin Brook's study of notable Puritans. Historian Lennam finds nothing in this transcript that is either "improbable or inconsistent with the Bishop's testy reputation."

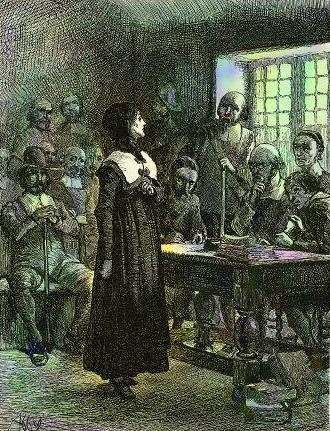

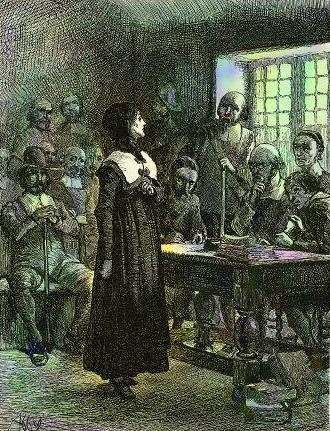

In the trial, Aylmer began the accusations of Marbury, saying "you had rattled the Bishop of Peterborough," to which Marbury accused the bishop of placing poorly trained ministers in the parish churches, adding that the bishops were poorly supervised. Aylmer then retorted, "The Bishop of Peterborough was never more overseen in his life than when he admitted thee to be a preacher in Northampton." Marbury warned that for every soul damned by the lack of adequate preaching, the guilt "is on the bishops' hands." To this Aylmer replied, "Thou takest upon thee to be a preacher, but there is nothing in thee. Thou art a very ass, an idiot, and a fool."

As the examination continued, Aylmer considered the ability of the Church of England to put trained ministers in every parish. He barked, "This fellow would have a preacher in every parish church!" to which Marbury replied, "so would St. Paul." Then Aylmer asked, "But where is the living for them?" To this Marbury answered, "A man might cut a large thong out of your hide, and that of the other prelates, and it would never be missed." Having lost his patience, the bishop retorted, "Thou are an overthwart, proud, puritan knave." Marbury answered, "I am no puritan. I beseech you to be good to me. I have been twice in prison already, but I know not why. To this, Aylmer was unsympathetic, and he rendered the sentence, "Have him to the Marshalsea

The Marshalsea (1373–1842) was a notorious prison in Southwark, just south of the River Thames. Although it housed a variety of prisoners, including men accused of crimes at sea and political figures charged with sedition, it became known, in ...

. There he shall cope with the papists." Marbury then threatened divine retribution upon the bishop by warning him to beware the judgements of God. His daughter Anne Hutchinson

Anne Hutchinson (née Marbury; July 1591 – August 1643) was a Puritan spiritual advisor, religious reformer, and an important participant in the Antinomian Controversy which shook the infant Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638. Her ...

would make a similar threat towards the magistrates and ministers at her civil trial before the Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

Court, nearly 60 years later.

Later life

For his conviction of heresy, Marbury spent two years in the Marshalsea prison, on the south side of the RiverThames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

, across from London. In 1580, at the age of 25, he was released and was considered sufficiently reformed to preach and teach, and moved to the market town of Alford in Lincolnshire, about north of London, near his ancestral home. He was soon appointed curate

A curate () is a person who is invested with the ''care'' or ''cure'' (''cura'') ''of souls'' of a parish. In this sense, "curate" means a parish priest; but in English-speaking countries the term ''curate'' is commonly used to describe clergy w ...

(deputy vicar) of St Wilfrid's Church, Alford

St Wilfrid's, Alford is the Church of England parish church in Alford, Lincolnshire, England. It is a Grade I listed building.

Background

The church is named after St Wilfrid and is the second church to be built on the site, the earlier bein ...

. His father died in 1581, leaving Marbury with some welcome income as well as "lawe bookes and a ring of gold."

Sometime about 1582 he married his first wife, Elizabeth Moore, and in 1585 he became the schoolmaster at Alford Grammar School, free to the poor and founded under Queen Elizabeth. Marbury is thought to have been the teacher or tutor of young John Smith, who became an early explorer and leader in the Jamestown Colony

The Jamestown settlement in the Colony of Virginia was the first permanent English settlement

''English Settlement'' is the fifth studio album and first double album by the English rock band XTC, released 12 February 1982 on Virgin Reco ...

in Virginia.

After bearing three daughters, Marbury's first wife died about 1586, and within a year of her death he married Bridget Dryden, about ten years younger than he, from a prominent Northamptonshire family. Bridget was born in the Canons Ashby House

Canons Ashby House is a Grade I listed Elizabethan manor house located in the village of Canons Ashby, about south of the town of Daventry in the county of Northamptonshire, England. It has been owned by the National Trust for Places of Historic ...

in Northamptonshire, the daughter of John Dryden and Elizabeth Cope. Her brother, Erasmus Dryden, was the grandfather of the playwright and Poet Laureate

A poet laureate (plural: poets laureate) is a poet officially appointed by a government or conferring institution, typically expected to compose poems for special events and occasions. Albertino Mussato of Padua and Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch) ...

John Dryden

''

John Dryden (; – ) was an English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who in 1668 was appointed England's first Poet Laureate.

He is seen as dominating the literary life of Restoration England to such a point that the per ...

.

In 1590 Marbury once again felt emboldened to speak out against his superiors, denouncing the Church of England for selecting poorly educated bishops and poorly trained ministers. The Bishop of Lincoln, calling him an "impudent Puritan," removed him from preaching and teaching, and put him under house arrest. On 15 October 1590 Marbury wrote a letter to the statesman

In 1590 Marbury once again felt emboldened to speak out against his superiors, denouncing the Church of England for selecting poorly educated bishops and poorly trained ministers. The Bishop of Lincoln, calling him an "impudent Puritan," removed him from preaching and teaching, and put him under house arrest. On 15 October 1590 Marbury wrote a letter to the statesman William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley

William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley (13 September 15204 August 1598) was an English statesman, the chief adviser of Queen Elizabeth I for most of her reign, twice Secretary of State (1550–1553 and 1558–1572) and Lord High Treasurer from 1 ...

, who was the uncle of Marbury's acquaintance, Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both ...

. In the letter he explained his religious creed and claimed that he was deprived of his preaching licence "for causes unknown to him." Without employment, he tended his gardens and tutored his children, reading to them from his own writings, the Bible, and John Foxe

John Foxe (1516/1517 – 18 April 1587), an English historian and martyrologist, was the author of '' Actes and Monuments'' (otherwise ''Foxe's Book of Martyrs''), telling of Christian martyrs throughout Western history, but particularly the su ...

's ''Book of Martyrs

The ''Actes and Monuments'' (full title: ''Actes and Monuments of these Latter and Perillous Days, Touching Matters of the Church''), popularly known as Foxe's Book of Martyrs, is a work of Protestant history and martyrology by Protestant Engli ...

''. Somehow the family was able to survive, perhaps from borrowing from the Drydens. While this suspension from preaching was thought to be short by historian Lennam, his daughter's biographer, Eve LaPlante, wrote that it lasted nearly four years. Whichever the case, by 1594 he was once again preaching, and from this point forward, Marbury resolved to curb his tongue and not openly question those in positions of authority.

Following this final suspension, both his fame and fortune rose, and at one point Marbury became lecturer at St Saviour, Southwark

Southwark Cathedral ( ) or The Cathedral and Collegiate Church of St Saviour and St Mary Overie, Southwark, London, lies on the south bank of the River Thames close to London Bridge. It is the mother church of the Anglican Diocese of Southwar ...

. In 1602 he was given the honour of delivering the "Spittle sermon" in London on Easter Tuesday, and again at St Paul's Cross

St Paul's Cross (alternative spellings – "Powles Crosse") was a preaching cross and open-air pulpit in the grounds of Old St Paul's Cathedral, City of London. It was the most important public pulpit in Tudor and early Stuart England, and ma ...

in London in June. The following year he had the distinction of delivering a special sermon on the accession of James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

to the throne, and at this point several of his sermons were finding their way into print. With the support of Richard Vaughan, the Bishop of London

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

, he was moved to London in 1605, finding a residence in the heart of the city where he was given the position of vicar

A vicar (; Latin: ''vicarius'') is a representative, deputy or substitute; anyone acting "in the person of" or agent for a superior (compare "vicarious" in the sense of "at second hand"). Linguistically, ''vicar'' is cognate with the English pref ...

of St Martin Vintry

St Martin Vintry was a parish church in the Vintry ward of the City of London, England. It was destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666 and never rebuilt.

History

The church stood at what is now the junction of Queen Street and Upper Thames ...

. Here his Puritan views, though somewhat muffled, were nevertheless present and tolerated, since there was a shortage of pastors.

London was a vibrant and cosmopolitan city, and active playwrights of the time were William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

, Christopher Marlowe

Christopher Marlowe, also known as Kit Marlowe (; baptised 26 February 156430 May 1593), was an English playwright, poet and translator of the Elizabethan era. Marlowe is among the most famous of the Elizabethan playwrights. Based upon the ...

, and Ben Jonson

Benjamin "Ben" Jonson (c. 11 June 1572 – c. 16 August 1637) was an English playwright and poet. Jonson's artistry exerted a lasting influence upon English poetry and stage comedy. He popularised the comedy of humours; he is best known for t ...

, whose plays were performed just across the river. The Marburys managed to avoid the bubonic plague

Bubonic plague is one of three types of plague caused by the plague bacterium (''Yersinia pestis''). One to seven days after exposure to the bacteria, flu-like symptoms develop. These symptoms include fever, headaches, and vomiting, as well a ...

that occasionally worked its way through the city. Marbury took on additional work in 1608, preaching in the parish of St Pancras, Soper Lane

St Pancras, Soper Lane, was a parish church in the City of London, in England. Of medieval origin, it was destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666 and not rebuilt.

History

St Pancras, Soper Lane, was in the Ward of Cheap, City of London.

, travelling there by horse twice a week. In 1610 he was able to replace that position with one much closer to home, and became rector of St Margaret, New Fish Street

St Margaret, New Fish Street, was a parish church in the City of London.

The Mortality Bill for the year 1665, published by the Parish Clerks' Company, shows 97 parishes within the City of London. By September 6 the city lay in ruins, 86 churche ...

, a short walk from St Martin Vintry. Marbury died unexpectedly in February 1611, at the age of 55. He had written his will in January 1611, and its brevity suggests that it was written in a hurry following a sudden and serious illness. The will mentions his wife by name and 12 living children, but only his daughter Susan, from his first marriage, is mentioned by name. His widow resided for a time at St Peter, Paul's Wharf, London, but about December 1620 she married Reverend Thomas Newman of Berkhamsted

Berkhamsted ( ) is a historic market town in Hertfordshire, England, in the Bulbourne valley, north-west of London. The town is a civil parish with a town council within the borough of Dacorum which is based in the neighbouring large new town ...

, Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is one of the home counties in southern England. It borders Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire to the north, Essex to the east, Greater London to the south, and Buckinghamshire to the west. For govern ...

, and died in 1645.

Works and legacy

Marbury's most noted work, ''The Contract of Marriage between Wit and Wisdom'' was written in 1579 while he was in prison. It was a moral interlude or "wit play", following '' The Play of Wit and Science'' byJohn Redford

John Redford (c. 1500 - died October or November 1547) was a major English composer, organist, and dramatist of the Tudor period. From about 1525 he was organist at St Paul's Cathedral (succeeding Thomas Hickman). He was choirmaster there from ...

, and an adaptation of its sequel ''The Marriage of Wit and Science''. The play was noted in 1590 as one of the "current plays of the time." Author T. N. S. Lennam described the work as a "lusty, occasionally very coarse, short interlude in which the morality material is dominated by rather imitative farcical episodes more elementally entertaining than didactic."

Marbury also helped write the preface to the works of other religious writers. One of these prefaces was written for Robert Rollock

Robert Rollock (c. 15558 or 9 February 1599) was Scottish academic and minister in the Church of Scotland, and the first regent and first principal of the University of Edinburgh. Born into a noble family, he distinguished himself during ...

's ''A Treatise on God's Effectual Calling'' (1603), and another was for Richard Rogers' seminal work, ''Seven Treatises'' (1604). In the latter, Marbury praised Rogers "for having delivered a crushing blow against the Catholics and thereby vindicating the Church of England." This prefatory material summed up the puritan unitary vision for England: "one godly ruler, one godly church, and one godly path to heaven, with puritan ministers writing the guidebooks."

While Marbury was not considered one of the great Puritan ministers of his day, he was nevertheless well known. Sir Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both ...

called him "The Preacher," and recognised him as such in his 1624 work ''Apothegm''. A leading minister of the time, Reverend Robert Bolton

Robert Bolton (1572 – 16 December 1631) was an English clergyman and academic, noted as a preacher.

Life

He was born on Whit Sunday in Blackburn, Lancashire, the sixth son of Adam Bolton of Backhouse. He attended what is now Queen Elizabeth' ...

, expressed a considerable respect for Marbury's teachings.

One negative aspect of Marbury's later career involved his time in Alford when he was the governor of the free grammar school there between 1595 and 1605. A 1618 court case pointed to Marbury's improper handling of the school's endowments, and following an inquisition, the surviving executors to Marbury's will were ordered to pay "certain sums unto the Governors" of the school as compensation.

Family

Marbury was said to have 20 children, but only 18 have been identified, three with his first wife, Elizabeth Moore, and 15 with his second wife, Bridget Dryden. The three children from his first marriage were all girls, Mary (c. 1584–1585), Susan (baptised 12 September 1585; married a Mr Twyford) and Elizabeth (c. 1587–1601). His children with Bridget Dryden were Mary (born c. 1588), John (baptised 15 February 1589/90), Anne (baptised 20 July 1591), Bridget (baptised 8 May 1593; buried 15 October 1598), Francis (baptised 20 October 1594), Emme (baptised 21 December 1595), Erasmus (baptised 15 February 1596/7), Anthony (baptised 11 September 1598; buried 9 April 1601), Bridget (baptised 25 November 1599), Jeremuth (or Jeremoth, baptised 31 March 1601), Daniel (baptised 14 September 1602), Elizabeth (baptised 20 January 1604/5), Thomas (born c. 1606?), Anthony (born c. 1608), and

Marbury was said to have 20 children, but only 18 have been identified, three with his first wife, Elizabeth Moore, and 15 with his second wife, Bridget Dryden. The three children from his first marriage were all girls, Mary (c. 1584–1585), Susan (baptised 12 September 1585; married a Mr Twyford) and Elizabeth (c. 1587–1601). His children with Bridget Dryden were Mary (born c. 1588), John (baptised 15 February 1589/90), Anne (baptised 20 July 1591), Bridget (baptised 8 May 1593; buried 15 October 1598), Francis (baptised 20 October 1594), Emme (baptised 21 December 1595), Erasmus (baptised 15 February 1596/7), Anthony (baptised 11 September 1598; buried 9 April 1601), Bridget (baptised 25 November 1599), Jeremuth (or Jeremoth, baptised 31 March 1601), Daniel (baptised 14 September 1602), Elizabeth (baptised 20 January 1604/5), Thomas (born c. 1606?), Anthony (born c. 1608), and Katherine

Katherine, also spelled Catherine, and Catherina, other variations are feminine Given name, names. They are popular in Christian countries because of their derivation from the name of one of the first Christian saints, Catherine of Alexandria ...

(born c. 1610).

Three of Marbury's sons, Erasmus, Jeremuth, and the second Anthony, all matriculated at Brasenose College, Oxford

Brasenose College (BNC) is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. It began as Brasenose Hall in the 13th century, before being founded as a college in 1509. The library and chapel were added in the mi ...

. His daughter Anne married William Hutchinson William, Willie, Willy, Billy or Bill Hutchinson may refer to:

Politics and law

* Asa Hutchinson (born 1950), full name William Asa Hutchinson, 46th governor of Arkansas

* William Hutchinson (Rhode Island judge) (1586–1641), merchant, judge, ...

and sailed to New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

in 1634, becoming a dissident Puritan minister at the centre of the Antinomian Controversy

The Antinomian Controversy, also known as the Free Grace Controversy, was a religious and political conflict in the Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638. It pitted most of the colony's ministers and magistrates against some adherents of ...

, and was, according to historian Michael Winship, "the most famous, or infamous, English woman in colonial American history." His only other child to emigrate was his youngest child, Katherine

Katherine, also spelled Catherine, and Catherina, other variations are feminine Given name, names. They are popular in Christian countries because of their derivation from the name of one of the first Christian saints, Catherine of Alexandria ...

, who married Richard Scott and settled in Providence

Providence often refers to:

* Providentia, the divine personification of foresight in ancient Roman religion

* Divine providence, divinely ordained events and outcomes in Christianity

* Providence, Rhode Island, the capital of Rhode Island in the ...

in the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations

The Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations was one of the original Thirteen Colonies established on the east coast of America, bordering the Atlantic Ocean. It was founded by Roger Williams. It was an English colony from 1636 until ...

. Katherine and her husband were at times Puritans, Baptists, and Quakers, and Katherine was whipped in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

for confronting Governor John Endecott

John Endecott (also spelled Endicott; before 1600 – 15 March 1664/1665), regarded as one of the Fathers of New England, was the longest-serving governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, which became the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. He serv ...

over his persecution of Quakers and supporting her future son-in-law Christopher Holder

Christopher Holder (1631–1688), was an early Quaker evangelist who was imprisoned and whipped, had an ear cut off, and was threatened with death for his religious activism in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and in England. A native of Gloucestersh ...

who had his right ear cut off for his Quaker evangelism.

Marbury's sister, Catherine, married in 1583 Christopher Wentworth, and they became grandparents of William Wentworth

William Charles Wentworth (August 179020 March 1872) was an Australian pastoralist, explorer, newspaper editor, lawyer, politician and author, who became one of the wealthiest and most powerful figures of early colonial New South Wales.

Throug ...

who followed Reverend John Wheelwright

John Wheelwright (c. 1592–1679) was a Puritan clergyman in England and America, noted for being banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony during the Antinomian Controversy, and for subsequently establishing the town of Exeter, New Hamps ...

to New England, and eventually settled in Dover, New Hampshire

Dover is a city in Strafford County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 32,741 at the 2020 census, making it the largest city in the New Hampshire Seacoast region and the fifth largest municipality in the state. It is the county se ...

, becoming the ancestor of many men of prominence.

Ancestry

In 1914, John Champlin published the bulk of the currently known ancestry of Francis Marbury. Most of the material in the following ancestor chart is from Champlin, supplemented by genealogist Meredith Colket. The Williamson line was published in ''The American Genealogist

''The American Genealogist'' is a quarterly peer-reviewed academic journal which focuses on genealogy and family history. It was established by Donald Lines Jacobus in 1922 as the ''New Haven Genealogical Magazine''. In July 1932 it was renamed ' ...

'' by F. N. Craig in 1992, while an online source, cited within, covers the Angevine line. An online source giving the ancestry of Agnes Lenton is incorrect based on Walter Davis' research published in the ''New England Historic Genealogical Register'' in 1964.

See also

*Puritanism

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. P ...

* List of Puritans

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ''Online sources'' * * * * *Further reading

* Marbury, Francis, ''The Marriage Between Wit and Wisdom'' (1971),Malone Society

The Malone Society is a British-based text publication and general scholarly society devoted to the study of 16th- and early 17th-century drama. It publishes editions of plays from manuscript, facsimile editions of printed and manuscript plays of ...

Reprint Series, No. 125

* see p 20

*

External links

Rootsweb biography

{{DEFAULTSORT:Marbury, Francis 1555 births 1611 deaths 16th-century English educators 17th-century English educators 16th-century English Puritan ministers 17th-century English Puritan ministers 16th-century English writers 16th-century male writers 17th-century English writers 17th-century English male writers Alumni of Christ's College, Cambridge English Renaissance dramatists 16th-century English dramatists and playwrights