Frag Grenade on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A grenade is an explosive weapon typically thrown by hand (also called hand grenade), but can also refer to a shell (explosive

A grenade is an explosive weapon typically thrown by hand (also called hand grenade), but can also refer to a shell (explosive

Rudimentary incendiary grenades appeared in the Eastern Roman Empire, Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, not long after the reign of Leo III the Isaurian, Leo III (717–741).Robert James Forbes: "Studies in Ancient Technology," Leiden 1993, , p. 107 Byzantine soldiers learned that Greek fire, a Byzantine invention of the previous century, could not only be thrown by flamethrowers at the enemy but also in stone and ceramic jars. Later, glass containers were employed. The use of such explosive missiles soon spread to Muslim armies in the Near East, from where it reached China by the 10th century.

Rudimentary incendiary grenades appeared in the Eastern Roman Empire, Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, not long after the reign of Leo III the Isaurian, Leo III (717–741).Robert James Forbes: "Studies in Ancient Technology," Leiden 1993, , p. 107 Byzantine soldiers learned that Greek fire, a Byzantine invention of the previous century, could not only be thrown by flamethrowers at the enemy but also in stone and ceramic jars. Later, glass containers were employed. The use of such explosive missiles soon spread to Muslim armies in the Near East, from where it reached China by the 10th century.

In China, during the Song Dynasty (960–1279 AD), weapons known as Zhen Tian Lei (, "Sky-shaking Thunder") were created when Chinese soldiers packed gunpowder into ceramic or metal containers fitted with fuses. In 1044, a military book ''Wujing Zongyao'' ("Compilation of Military Classics") described various gunpowder recipes in which one can find, according to Joseph Needham, the prototype of the modern hand grenade. The mid-14th-century book ''Huolongjing'' (, "Fire Dragon Manual"), written by Jiao Yu (), recorded an earlier Song-era cast-iron cannon known as the "flying-cloud thunderclap cannon" (; ). The manuscript stated that (Needham's modified Wade-Giles spelling):

In China, during the Song Dynasty (960–1279 AD), weapons known as Zhen Tian Lei (, "Sky-shaking Thunder") were created when Chinese soldiers packed gunpowder into ceramic or metal containers fitted with fuses. In 1044, a military book ''Wujing Zongyao'' ("Compilation of Military Classics") described various gunpowder recipes in which one can find, according to Joseph Needham, the prototype of the modern hand grenade. The mid-14th-century book ''Huolongjing'' (, "Fire Dragon Manual"), written by Jiao Yu (), recorded an earlier Song-era cast-iron cannon known as the "flying-cloud thunderclap cannon" (; ). The manuscript stated that (Needham's modified Wade-Giles spelling):

Grenade-like devices were also known in ancient India. In a 12th-century work Mujmalut Tawarikh based on an Arabic work which is itself based on original Sanskrit work, a terracotta elephant filled with explosives set with a Fuse (explosives), fuse was placed hidden in the van and exploded as the invading army approached near.

The first cast-iron bombshells and grenades appeared in Europe in 1467, where their initial role was with the besieging and defense of castles and fortifications.Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 179. A hoard of several hundred ceramic hand grenades was discovered during construction in front of a bastion of the Bavarian city of Ingolstadt, Germany dated to the 17th century. Many of the grenades retained their original black powder loads and igniters. The grenades were most likely intentionally dumped in the moat of the bastion prior to 1723. By the mid 17th century, infantry known as Grenadiers began to emerge in the armies of Europe, who specialized in shock and close quarters combat, mostly with the usage of grenades and fierce melee combat. In 1643, it is possible that "Grenados" were thrown amongst the Welsh at Holt, Wrexham, Holt Bridge during the English Civil War. The word "grenade" was also used during the events surrounding the Glorious Revolution in 1688, where cricket ball-sized ( in circumference) iron spheres packed with gunpowder and fitted with slow-burning wicks were first used against the Jacobitism, Jacobites in the battles of Battle of Killiecrankie, Killiecrankie and Battle of Glen Shiel, Glen Shiel. These grenades were not very effective owing both to the unreliability of their Fuse (explosives), fuse, as well inconsistent times to detonation, and as a result, saw little use. Grenades were also used during the Golden Age of Piracy, especially during boarding actions; pirate Captain Thompson used "vast numbers of powder flasks, grenade shells, and stinkpots" to defeat two pirate-hunters sent by the Governor of Jamaica in 1721.

Improvised grenades were increasingly used from the mid-19th century, the confines of trenches enhancing the effect of small explosive devices. In a letter to his sister, Colonel Hugh Robert Hibbert described an improvised grenade that was employed by British troops during the Crimean War (1854–1856):

In the American Civil War, both sides used hand grenades equipped with a plunger that detonated the device on impact. The Union (American Civil War), Union relied on experimental Ketchum Grenades, which had a tail to ensure that the nose would strike the target and start the fuze. The Confederacy (American Civil War), Confederacy used spherical hand grenades that weighed about , sometimes with a paper fuze. They also used 'Rains' and 'Adams' grenades, which were similar to the Ketchum in appearance and mechanism. Improvised hand grenades were also used to great effect by the Russian defenders of Port Arthur, China, Port Arthur during the Russo-Japanese War.

Grenade-like devices were also known in ancient India. In a 12th-century work Mujmalut Tawarikh based on an Arabic work which is itself based on original Sanskrit work, a terracotta elephant filled with explosives set with a Fuse (explosives), fuse was placed hidden in the van and exploded as the invading army approached near.

The first cast-iron bombshells and grenades appeared in Europe in 1467, where their initial role was with the besieging and defense of castles and fortifications.Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 179. A hoard of several hundred ceramic hand grenades was discovered during construction in front of a bastion of the Bavarian city of Ingolstadt, Germany dated to the 17th century. Many of the grenades retained their original black powder loads and igniters. The grenades were most likely intentionally dumped in the moat of the bastion prior to 1723. By the mid 17th century, infantry known as Grenadiers began to emerge in the armies of Europe, who specialized in shock and close quarters combat, mostly with the usage of grenades and fierce melee combat. In 1643, it is possible that "Grenados" were thrown amongst the Welsh at Holt, Wrexham, Holt Bridge during the English Civil War. The word "grenade" was also used during the events surrounding the Glorious Revolution in 1688, where cricket ball-sized ( in circumference) iron spheres packed with gunpowder and fitted with slow-burning wicks were first used against the Jacobitism, Jacobites in the battles of Battle of Killiecrankie, Killiecrankie and Battle of Glen Shiel, Glen Shiel. These grenades were not very effective owing both to the unreliability of their Fuse (explosives), fuse, as well inconsistent times to detonation, and as a result, saw little use. Grenades were also used during the Golden Age of Piracy, especially during boarding actions; pirate Captain Thompson used "vast numbers of powder flasks, grenade shells, and stinkpots" to defeat two pirate-hunters sent by the Governor of Jamaica in 1721.

Improvised grenades were increasingly used from the mid-19th century, the confines of trenches enhancing the effect of small explosive devices. In a letter to his sister, Colonel Hugh Robert Hibbert described an improvised grenade that was employed by British troops during the Crimean War (1854–1856):

In the American Civil War, both sides used hand grenades equipped with a plunger that detonated the device on impact. The Union (American Civil War), Union relied on experimental Ketchum Grenades, which had a tail to ensure that the nose would strike the target and start the fuze. The Confederacy (American Civil War), Confederacy used spherical hand grenades that weighed about , sometimes with a paper fuze. They also used 'Rains' and 'Adams' grenades, which were similar to the Ketchum in appearance and mechanism. Improvised hand grenades were also used to great effect by the Russian defenders of Port Arthur, China, Port Arthur during the Russo-Japanese War.

Around the turn of the 20th century, the ineffectiveness of the available types of hand grenades, coupled with their levels of danger to the user and difficulty of operation, meant that they were regarded as increasingly obsolete pieces of military equipment. In 1902, the British War Office announced that hand grenades were obsolete and had no place in modern warfare. But within two years, following the success of improvised grenades in the trench warfare conditions of the Russo-Japanese War, and reports from Aylmer Haldane, General Sir Aylmer Haldane, a British observer of the conflict, a reassessment was quickly made and the Board of Ordnance was instructed to develop a practical hand grenade. Various models using a Fuse (explosives), percussion fuze were built, but this type of fuze suffered from various practical problems, and they were not commissioned in large numbers.

Marten Hale, better known for patenting the Hales rifle grenade, developed a modern hand grenade in 1906 but was unsuccessful in persuading the British Army to adopt the weapon until 1913. Hale's chief competitor was Nils Waltersen Aasen, who invented his design in 1906 in Norway, receiving a patent for it in England. Aasen began his experiments with developing a grenade while serving as a sergeant in the Oscarsborg Fortress. Aasen formed the ''Aasenske Granatkompani'' in Denmark, which before the First World War produced and exported hand grenades in large numbers across Europe. He had success in marketing his weapon to the French and was appointed as a Legion of Honour, Knight of the French Legion of Honour in 1916 for the invention.

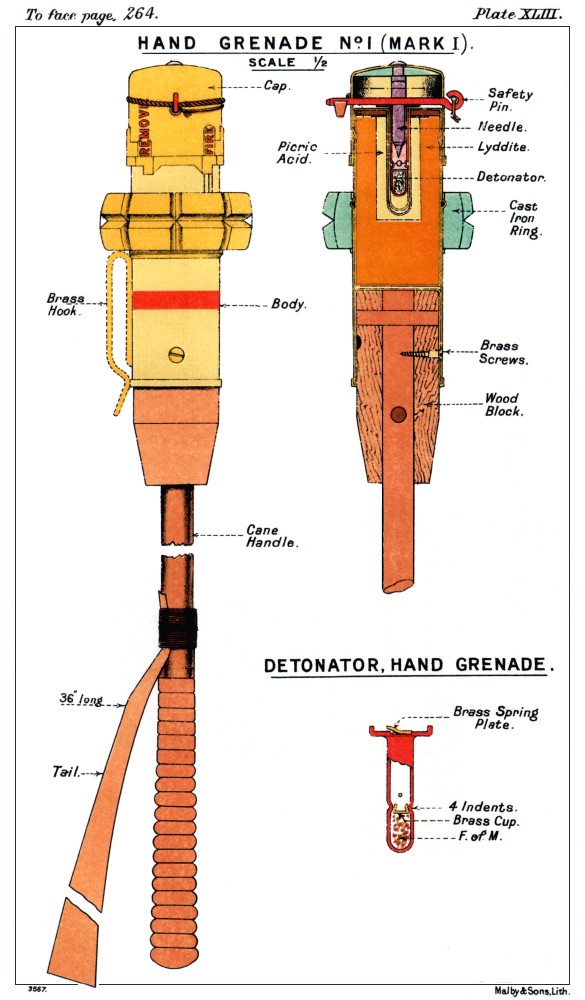

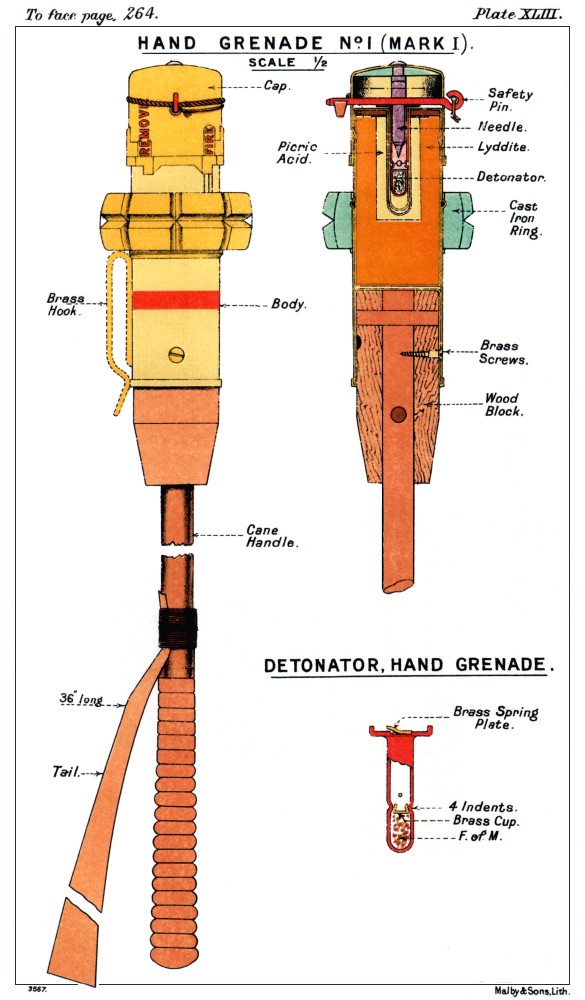

The Royal Laboratory developed the No. 1 grenade in 1908. It contained explosive material with an iron Fragmentation (weaponry), fragmentation band, with an impact Fuse (explosives), fuze, detonating when the top of the grenade hit the ground. A long cane handle (approximately 16 inches or 40 cm) allowed the user to throw the grenade farther than the blast of the explosion. It suffered from the handicap that the percussion fuse was armed before throwing, which meant that if the user was in a trench or other confined space, he was apt to detonate it and kill himself when he drew back his arm to throw it.

Early in World War I, combatant nations only had small grenades, similar to Hales' and Aasen's design. The Italian Besozzi grenade had a five-second fuze with a match-tip that was ignited by striking on a ring on the soldier's hand. As an interim measure, troops often improvised their own grenades, such as the jam tin grenade.

Around the turn of the 20th century, the ineffectiveness of the available types of hand grenades, coupled with their levels of danger to the user and difficulty of operation, meant that they were regarded as increasingly obsolete pieces of military equipment. In 1902, the British War Office announced that hand grenades were obsolete and had no place in modern warfare. But within two years, following the success of improvised grenades in the trench warfare conditions of the Russo-Japanese War, and reports from Aylmer Haldane, General Sir Aylmer Haldane, a British observer of the conflict, a reassessment was quickly made and the Board of Ordnance was instructed to develop a practical hand grenade. Various models using a Fuse (explosives), percussion fuze were built, but this type of fuze suffered from various practical problems, and they were not commissioned in large numbers.

Marten Hale, better known for patenting the Hales rifle grenade, developed a modern hand grenade in 1906 but was unsuccessful in persuading the British Army to adopt the weapon until 1913. Hale's chief competitor was Nils Waltersen Aasen, who invented his design in 1906 in Norway, receiving a patent for it in England. Aasen began his experiments with developing a grenade while serving as a sergeant in the Oscarsborg Fortress. Aasen formed the ''Aasenske Granatkompani'' in Denmark, which before the First World War produced and exported hand grenades in large numbers across Europe. He had success in marketing his weapon to the French and was appointed as a Legion of Honour, Knight of the French Legion of Honour in 1916 for the invention.

The Royal Laboratory developed the No. 1 grenade in 1908. It contained explosive material with an iron Fragmentation (weaponry), fragmentation band, with an impact Fuse (explosives), fuze, detonating when the top of the grenade hit the ground. A long cane handle (approximately 16 inches or 40 cm) allowed the user to throw the grenade farther than the blast of the explosion. It suffered from the handicap that the percussion fuse was armed before throwing, which meant that if the user was in a trench or other confined space, he was apt to detonate it and kill himself when he drew back his arm to throw it.

Early in World War I, combatant nations only had small grenades, similar to Hales' and Aasen's design. The Italian Besozzi grenade had a five-second fuze with a match-tip that was ignited by striking on a ring on the soldier's hand. As an interim measure, troops often improvised their own grenades, such as the jam tin grenade.

Improvised grenades were replaced when manufactured versions became available. The first modern fragmentation grenade was the Mills bomb, which became available to British front-line troops in 1915.

William Mills (inventor), William Mills, a hand grenade designer from Sunderland, Tyne and Wear, Sunderland, patented, developed and manufactured the "Mills bomb" at the Mills Munition Factory in Birmingham, England in 1915, designating it the No.5. It was described as the first "safe grenade." They were explosive-filled steel canisters with a triggering pin and a distinctive deeply notched surface. This segmentation is often erroneously thought to aid fragmentation (weaponry), fragmentation, though Mills' own notes show the external grooves were purely to aid the soldier to grip the weapon. Improved fragmentation designs were later made with the notches on the inside, but at that time they would have been too expensive to produce. The external segmentation of the original Mills bomb was retained, as it provided a positive :wikt:grip, grip surface. This basic "pin-and-pineapple" design is still used in some modern grenades.

The Mills bomb underwent numerous modifications. The No. 23 was a variant of the No. 5 with a rodded base plug which allowed it to be rifle grenade, fired from a rifle. This concept evolved further with the No. 36, a variant with a detachable base plate to allow use with a rifle discharger cup. The final variation of the Mills bomb, the No. 36M, was specially designed and waterproofed with shellac for use initially in the hot climate of Mesopotamia in 1917, and remained in production for many years. By 1918, the No. 5 and No. 23 were declared obsolete and the No. 36 (but not the 36M) followed in 1932.

The Mills had a grooved cast-iron "pineapple" with a central striker held by a close hand lever and secured with a pin. A competent thrower could manage with reasonable accuracy, but the grenade could throw lethal fragments farther than this; after throwing, the user had to take cover immediately. The British Home Guard was instructed that the throwing range of the No. 36 was about with a danger area of about .

Approximately 75,000,000 grenades were manufactured during World War I, used in the war and remaining in use through to the World War II, Second World War. At first, the grenade was fitted with a seven-second fuze, but during combat in the Battle of France in 1940, this delay proved too long, giving defenders time to escape the explosion or to throw the grenade back, so the delay was reduced to four seconds.

The F1 grenade (France), F1 grenade was first produced in limited quantities by France in May 1915. This new weapon had improvements from the experience of the first months of the war: the shape was more modern, with an external groove pattern for better grip and easier fragmentation. The second expectation proved deceptive, as the explosion in practice gave no more than 10 fragments (although the pattern was designed to split into all the 38 drawn divisions). The design proved to be very functional, especially due to its stability compared to other grenades of the same period. The F1 was used by many foreign armies from 1915 to 1940.

Improvised grenades were replaced when manufactured versions became available. The first modern fragmentation grenade was the Mills bomb, which became available to British front-line troops in 1915.

William Mills (inventor), William Mills, a hand grenade designer from Sunderland, Tyne and Wear, Sunderland, patented, developed and manufactured the "Mills bomb" at the Mills Munition Factory in Birmingham, England in 1915, designating it the No.5. It was described as the first "safe grenade." They were explosive-filled steel canisters with a triggering pin and a distinctive deeply notched surface. This segmentation is often erroneously thought to aid fragmentation (weaponry), fragmentation, though Mills' own notes show the external grooves were purely to aid the soldier to grip the weapon. Improved fragmentation designs were later made with the notches on the inside, but at that time they would have been too expensive to produce. The external segmentation of the original Mills bomb was retained, as it provided a positive :wikt:grip, grip surface. This basic "pin-and-pineapple" design is still used in some modern grenades.

The Mills bomb underwent numerous modifications. The No. 23 was a variant of the No. 5 with a rodded base plug which allowed it to be rifle grenade, fired from a rifle. This concept evolved further with the No. 36, a variant with a detachable base plate to allow use with a rifle discharger cup. The final variation of the Mills bomb, the No. 36M, was specially designed and waterproofed with shellac for use initially in the hot climate of Mesopotamia in 1917, and remained in production for many years. By 1918, the No. 5 and No. 23 were declared obsolete and the No. 36 (but not the 36M) followed in 1932.

The Mills had a grooved cast-iron "pineapple" with a central striker held by a close hand lever and secured with a pin. A competent thrower could manage with reasonable accuracy, but the grenade could throw lethal fragments farther than this; after throwing, the user had to take cover immediately. The British Home Guard was instructed that the throwing range of the No. 36 was about with a danger area of about .

Approximately 75,000,000 grenades were manufactured during World War I, used in the war and remaining in use through to the World War II, Second World War. At first, the grenade was fitted with a seven-second fuze, but during combat in the Battle of France in 1940, this delay proved too long, giving defenders time to escape the explosion or to throw the grenade back, so the delay was reduced to four seconds.

The F1 grenade (France), F1 grenade was first produced in limited quantities by France in May 1915. This new weapon had improvements from the experience of the first months of the war: the shape was more modern, with an external groove pattern for better grip and easier fragmentation. The second expectation proved deceptive, as the explosion in practice gave no more than 10 fragments (although the pattern was designed to split into all the 38 drawn divisions). The design proved to be very functional, especially due to its stability compared to other grenades of the same period. The F1 was used by many foreign armies from 1915 to 1940.

Stick grenades have a long handle attached to the grenade proper, providing Mechanical advantage, leverage for longer throwing distance, at the cost of additional weight.

The British introduced their No. 1 grenade in 1908. It had been designed on reports of Japanese weapons used in the Russo-Japanese war. The handle was very long and a streamer tied to the end was used to ensure the fuse hit the ground properly.

The term "stick grenade" is commonly associated with the German ''Stielhandgranate'' introduced in 1915 and developed throughout World War I. A friction igniter was used; this method was uncommon in other countries but widely used for German grenades.

A pull cord ran down the hollow handle from the

Stick grenades have a long handle attached to the grenade proper, providing Mechanical advantage, leverage for longer throwing distance, at the cost of additional weight.

The British introduced their No. 1 grenade in 1908. It had been designed on reports of Japanese weapons used in the Russo-Japanese war. The handle was very long and a streamer tied to the end was used to ensure the fuse hit the ground properly.

The term "stick grenade" is commonly associated with the German ''Stielhandgranate'' introduced in 1915 and developed throughout World War I. A friction igniter was used; this method was uncommon in other countries but widely used for German grenades.

A pull cord ran down the hollow handle from the

Fragmentation grenades are common in armies. They are weapons that are designed to disperse fragments on detonation, aimed to damage targets within as the lethal and injury radii. The body is generally made of a hard synthetic material or steel, which will provide some fragmentation as shards and splinters, though in modern grenades a pre-formed fragmentation matrix is often used. The pre-formed fragmentation may be spherical, cuboid, wire or notched wire. Most AP grenades are designed to detonate either after a time delay or on impact.

When the word ''grenade'' is used without specification, and context does not suggest otherwise, it is generally assumed to refer to a fragmentation grenade.

Fragmentation grenades can be divided into two main types, defensive and offensive, where the former are designed to be used from a position of cover (e.g. in a slit trench or behind a suitable wall) against an open area outside, and have an effective kill radius greater than the distance they can be thrown; while the latter are for use by assaulting troops, and have a smaller effective radius.

The Mills bombs and the French/F-1 grenade (Russia), Soviet F1 are examples of defensive grenades. The Dutch V40, Swiss HG 85, and US MK3 are examples of offensive grenades.

Modern fragmentation grenades, such as the United States M67 grenade, have a wounding radius of – half that of older style grenades, which can still be encountered – and can be thrown about . Fragments may travel more than .

Fragmentation grenades are common in armies. They are weapons that are designed to disperse fragments on detonation, aimed to damage targets within as the lethal and injury radii. The body is generally made of a hard synthetic material or steel, which will provide some fragmentation as shards and splinters, though in modern grenades a pre-formed fragmentation matrix is often used. The pre-formed fragmentation may be spherical, cuboid, wire or notched wire. Most AP grenades are designed to detonate either after a time delay or on impact.

When the word ''grenade'' is used without specification, and context does not suggest otherwise, it is generally assumed to refer to a fragmentation grenade.

Fragmentation grenades can be divided into two main types, defensive and offensive, where the former are designed to be used from a position of cover (e.g. in a slit trench or behind a suitable wall) against an open area outside, and have an effective kill radius greater than the distance they can be thrown; while the latter are for use by assaulting troops, and have a smaller effective radius.

The Mills bombs and the French/F-1 grenade (Russia), Soviet F1 are examples of defensive grenades. The Dutch V40, Swiss HG 85, and US MK3 are examples of offensive grenades.

Modern fragmentation grenades, such as the United States M67 grenade, have a wounding radius of – half that of older style grenades, which can still be encountered – and can be thrown about . Fragments may travel more than .

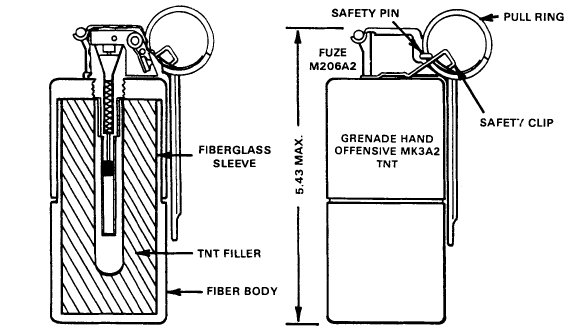

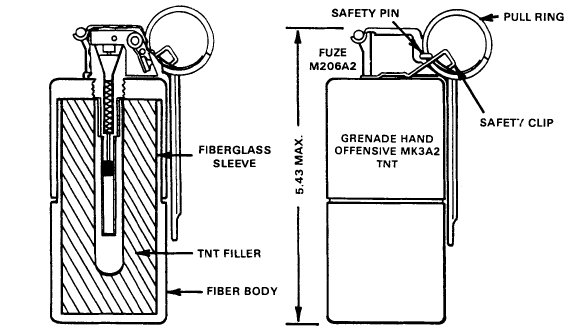

The high explosive (HE) or concussion grenade is an Anti-personnel weapon, anti-personnel device that is designed to damage, daze or otherwise stun its targets with overpressure shockwaves. Compared to fragmentation grenades, the explosive filler is usually of a greater weight and volume, and the case is much thinner – the US MK3A2 concussion grenade, for example, has a body of fiber (similar to the packing container for the fragmentation grenade).

These grenades are usually classed as offensive weapons because the effective casualty radius is much less than the distance it can be thrown, and its explosive power works better within more confined spaces such as fortifications or buildings, where entrenched defenders often occupy. The concussion effect, rather than any expelled fragments, is the effective killer. In the case of the US MK3 grenade, Mk3A2, the casualty radius is published as in ''open'' areas, but fragments and bits of fuze may be projected as far as from the detonation point.

Concussion grenades have also been used as depth charges (underwater explosives) around boats and underwater targets; some like the US United States hand grenades#Mk 40 Mod 0/1, Mk 40 concussion grenade are designed for use against enemy divers and Frogman, frogmen. Underwater explosions kill or otherwise incapacitate the target by creating a lethal shock wave underwater.Dockery 1997, p. 188.

The US Army Armament Research, Development and Engineering Center (ARDEC) announced in 2016 that they were developing a grenade which could operate in either fragmentation or blast mode (selected at any time before throwing), the electronically fuzed ''enhanced tactical multi-purpose'' (ET-MP) hand grenade.

Some concussion grenades with cylindrical bodies can be converted into fragmentation grenades by coupling with a separate factory-made payload of fragments wrapped around the outside: a "fragmentation sleeve (jacket)", as shown in the WW2 ''Splitterring'' sleeves for the stick grenade and M39 "egg hand grenade".

The high explosive (HE) or concussion grenade is an Anti-personnel weapon, anti-personnel device that is designed to damage, daze or otherwise stun its targets with overpressure shockwaves. Compared to fragmentation grenades, the explosive filler is usually of a greater weight and volume, and the case is much thinner – the US MK3A2 concussion grenade, for example, has a body of fiber (similar to the packing container for the fragmentation grenade).

These grenades are usually classed as offensive weapons because the effective casualty radius is much less than the distance it can be thrown, and its explosive power works better within more confined spaces such as fortifications or buildings, where entrenched defenders often occupy. The concussion effect, rather than any expelled fragments, is the effective killer. In the case of the US MK3 grenade, Mk3A2, the casualty radius is published as in ''open'' areas, but fragments and bits of fuze may be projected as far as from the detonation point.

Concussion grenades have also been used as depth charges (underwater explosives) around boats and underwater targets; some like the US United States hand grenades#Mk 40 Mod 0/1, Mk 40 concussion grenade are designed for use against enemy divers and Frogman, frogmen. Underwater explosions kill or otherwise incapacitate the target by creating a lethal shock wave underwater.Dockery 1997, p. 188.

The US Army Armament Research, Development and Engineering Center (ARDEC) announced in 2016 that they were developing a grenade which could operate in either fragmentation or blast mode (selected at any time before throwing), the electronically fuzed ''enhanced tactical multi-purpose'' (ET-MP) hand grenade.

Some concussion grenades with cylindrical bodies can be converted into fragmentation grenades by coupling with a separate factory-made payload of fragments wrapped around the outside: a "fragmentation sleeve (jacket)", as shown in the WW2 ''Splitterring'' sleeves for the stick grenade and M39 "egg hand grenade".

A range of hand-thrown grenades have been designed for use against heavy armored vehicles. An early and unreliable example was the British sticky bomb of 1940, which was too short-ranged to use effectively. Designs such as the German ''Panzerwurfmine'' (L) and the Soviet RPG-43, RPG-40, RPG-6 and RKG-3 series of grenades used a high-explosive anti-tank (HEAT) warhead using a cone-shaped cavity on one end and some method to stabilize flight and increase the probability of right angle impact for the shaped charge's metal stream to effectively penetrate the tank armor.

Due to improvements in modern vehicle armor, anti-tank hand grenades have become almost obsolete and replaced by rocket-propelled grenade, rocket-propelled shaped charges. However, they were still used with limited success against lightly-armored Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected, mine-resistant ambush protected (MRAP) vehicles, designed for protection only against improvised explosive devices in the Iraqi insurgency (2003–2006), Iraqi insurgency in the early 2000s.

A range of hand-thrown grenades have been designed for use against heavy armored vehicles. An early and unreliable example was the British sticky bomb of 1940, which was too short-ranged to use effectively. Designs such as the German ''Panzerwurfmine'' (L) and the Soviet RPG-43, RPG-40, RPG-6 and RKG-3 series of grenades used a high-explosive anti-tank (HEAT) warhead using a cone-shaped cavity on one end and some method to stabilize flight and increase the probability of right angle impact for the shaped charge's metal stream to effectively penetrate the tank armor.

Due to improvements in modern vehicle armor, anti-tank hand grenades have become almost obsolete and replaced by rocket-propelled grenade, rocket-propelled shaped charges. However, they were still used with limited success against lightly-armored Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected, mine-resistant ambush protected (MRAP) vehicles, designed for protection only against improvised explosive devices in the Iraqi insurgency (2003–2006), Iraqi insurgency in the early 2000s.

A stun grenade, also known as a ''flash grenade'' or ''flashbang'', is a non-lethal weapon. The first devices like this were created in the 1960s at the order of the British Special Air Service as a distraction grenade.

It is designed to produce a blinding flash of light and loud noise without causing permanent injury. The flash produced momentarily activates all light sensitive cells in the human eye, eye, making vision impossible for approximately five seconds, until the eye restores itself to its normal, unstimulated state. The loud blast causes temporary loss of hearing, and also disturbs the Perilymph, fluid in the ear, causing loss of balance.

These grenades are designed to temporarily neutralize the combat effectiveness of enemies by disorienting their senses.

When detonation, detonated, the fuze-grenade body assembly remains intact. The body is a tube with holes along the sides that emit the light and sound of the explosion. The explosion does not generally cause fragmentation injury, but can still burn. The concussive blast of the detonation can injure and the heat created can ignite flammable materials such as fuel. The fires that occurred during the Iranian Embassy Siege in London were caused by stun grenades. The filler consists of about of a pyrotechnic metal-oxidant mix of magnesium or aluminium and an oxidizer such as ammonium perchlorate or potassium perchlorate.

A stun grenade, also known as a ''flash grenade'' or ''flashbang'', is a non-lethal weapon. The first devices like this were created in the 1960s at the order of the British Special Air Service as a distraction grenade.

It is designed to produce a blinding flash of light and loud noise without causing permanent injury. The flash produced momentarily activates all light sensitive cells in the human eye, eye, making vision impossible for approximately five seconds, until the eye restores itself to its normal, unstimulated state. The loud blast causes temporary loss of hearing, and also disturbs the Perilymph, fluid in the ear, causing loss of balance.

These grenades are designed to temporarily neutralize the combat effectiveness of enemies by disorienting their senses.

When detonation, detonated, the fuze-grenade body assembly remains intact. The body is a tube with holes along the sides that emit the light and sound of the explosion. The explosion does not generally cause fragmentation injury, but can still burn. The concussive blast of the detonation can injure and the heat created can ignite flammable materials such as fuel. The fires that occurred during the Iranian Embassy Siege in London were caused by stun grenades. The filler consists of about of a pyrotechnic metal-oxidant mix of magnesium or aluminium and an oxidizer such as ammonium perchlorate or potassium perchlorate.

Incendiary grenades produce intense heat by means of a chemical reaction. Seventh-century "Greek fire" first used by the Byzantine Empire, which could be lit and thrown in breakable pottery, could be considered the earliest form of incendiary grenade.

The body of modern incendiary grenades is often similar in appearance to that of a smoke grenade, though generally smaller in size. The filler can be various chemicals, and while white phosphorus is well known, red phosphorus is also used for a number of reasons, not least because it is more stable and requires ignition, making it a safer option for the troops using it.

White phosphorus was used in the British No 77 grenade, No. 77 Mk. 1 and in a solution form for the Home Guard (United Kingdom), British Home Guard's No 76 special incendiary grenade during World War II.

The Molotov cocktail is an improvised incendiary grenade made with a glass bottle typically filled with gasoline (petrol), although sometimes another flammable liquid or mixture is used. The Molotov cocktail is ignited by a burning strip of cloth or a rag stuffed in the bottle's orifice when it shatters against its target which sets a small area on fire. The Molotov cocktail received its name during the Soviet invasion of Finland in 1939 (Winter War, the Winter War) by Finnish troops after the former Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov, whom they deemed responsible for the war. A similar weapon was used earlier in the decade by Franco's troops during the Spanish Civil War.

Incendiary grenades produce intense heat by means of a chemical reaction. Seventh-century "Greek fire" first used by the Byzantine Empire, which could be lit and thrown in breakable pottery, could be considered the earliest form of incendiary grenade.

The body of modern incendiary grenades is often similar in appearance to that of a smoke grenade, though generally smaller in size. The filler can be various chemicals, and while white phosphorus is well known, red phosphorus is also used for a number of reasons, not least because it is more stable and requires ignition, making it a safer option for the troops using it.

White phosphorus was used in the British No 77 grenade, No. 77 Mk. 1 and in a solution form for the Home Guard (United Kingdom), British Home Guard's No 76 special incendiary grenade during World War II.

The Molotov cocktail is an improvised incendiary grenade made with a glass bottle typically filled with gasoline (petrol), although sometimes another flammable liquid or mixture is used. The Molotov cocktail is ignited by a burning strip of cloth or a rag stuffed in the bottle's orifice when it shatters against its target which sets a small area on fire. The Molotov cocktail received its name during the Soviet invasion of Finland in 1939 (Winter War, the Winter War) by Finnish troops after the former Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov, whom they deemed responsible for the war. A similar weapon was used earlier in the decade by Franco's troops during the Spanish Civil War.

Practice or simulation grenades are similar in handling and function to other hand grenades, except that they only produce a loud popping noise and a puff of smoke on detonation. The grenade body can be reused. Another type is the throwing practice grenade which is completely inert and often cast in one piece. It is used to give soldiers a feel for the weight and shape of real grenades and for practicing precision throwing. Examples of practice grenades include the K417 Biodegradable Practice Hand Grenade by CNOTech Korea.

Practice or simulation grenades are similar in handling and function to other hand grenades, except that they only produce a loud popping noise and a puff of smoke on detonation. The grenade body can be reused. Another type is the throwing practice grenade which is completely inert and often cast in one piece. It is used to give soldiers a feel for the weight and shape of real grenades and for practicing precision throwing. Examples of practice grenades include the K417 Biodegradable Practice Hand Grenade by CNOTech Korea.

Various fuzes (detonation mechanisms) are used, depending on purpose:

; Impact: Examples of grenades fitted with contact fuzes are the German M1913 and M1915 Diskushandgranate, and British grenades fitted with the No. 247 "''All ways''" fuze - these were the No 69 grenade, No. 69 grenade, No. 70 grenade, No. 73 grenade, No 77 grenade, No. 77 grenade, No.79 grenade and gammon bomb, No. 82 grenade (Gammon bomb).

; Instantaneous fuze: These have no delay and were mainly used for victim actuated booby traps: they can be pull, pressure or release switches. Booby traps are classed as mines under the Ottawa Treaty.

; Timed fuze: In a timed fuze grenade, the fuze is ignited on the release of the safety lever, or by pulling the igniter cord in the case of many stick grenades, and detonation occurs following a timed delay. Timed fuze grenades are generally preferred to hand-thrown percussion grenades because their fusing mechanisms are safer and more robust than those used in percussion grenades. Fuzes are commonly fixed, though the Russian UZRGM (russian: УЗРГМ) fuzes are interchangeable and allow the delay to be varied, or replaced by a zero-delay pull fuze. This is potentially dangerous due to the risk of confusion by operators.

Beyond the basic "pin-and-lever" mechanism, many contemporary grenades have other safety features. The main ones are the safety clip and a locking end to the release pin. The clip was introduced in the M61 grenade (1960s, Vietnam War), and was also then known as the "jungle clip" – it provides a backup for the safety pin, in case it is dislodged, eg. by jungle flora. This is particularly important as poorly trained troops have been known to use the safety lever as a hook from which to suspend the grenade, despite the apparently obvious danger this poses. The 2016 US ET-MP uses a user-settable timed electronic fuze, though neither the fuze nor grenade have yet been accepted into service anywhere in the world.

Various fuzes (detonation mechanisms) are used, depending on purpose:

; Impact: Examples of grenades fitted with contact fuzes are the German M1913 and M1915 Diskushandgranate, and British grenades fitted with the No. 247 "''All ways''" fuze - these were the No 69 grenade, No. 69 grenade, No. 70 grenade, No. 73 grenade, No 77 grenade, No. 77 grenade, No.79 grenade and gammon bomb, No. 82 grenade (Gammon bomb).

; Instantaneous fuze: These have no delay and were mainly used for victim actuated booby traps: they can be pull, pressure or release switches. Booby traps are classed as mines under the Ottawa Treaty.

; Timed fuze: In a timed fuze grenade, the fuze is ignited on the release of the safety lever, or by pulling the igniter cord in the case of many stick grenades, and detonation occurs following a timed delay. Timed fuze grenades are generally preferred to hand-thrown percussion grenades because their fusing mechanisms are safer and more robust than those used in percussion grenades. Fuzes are commonly fixed, though the Russian UZRGM (russian: УЗРГМ) fuzes are interchangeable and allow the delay to be varied, or replaced by a zero-delay pull fuze. This is potentially dangerous due to the risk of confusion by operators.

Beyond the basic "pin-and-lever" mechanism, many contemporary grenades have other safety features. The main ones are the safety clip and a locking end to the release pin. The clip was introduced in the M61 grenade (1960s, Vietnam War), and was also then known as the "jungle clip" – it provides a backup for the safety pin, in case it is dislodged, eg. by jungle flora. This is particularly important as poorly trained troops have been known to use the safety lever as a hook from which to suspend the grenade, despite the apparently obvious danger this poses. The 2016 US ET-MP uses a user-settable timed electronic fuze, though neither the fuze nor grenade have yet been accepted into service anywhere in the world.

The classic hand grenade design has a safety handle or lever (known in the US forces as a ''spoon'') and a removable safety pin that prevents the handle from being released: the safety lever is spring-loaded, and once the safety pin is removed, the lever will release and ignite the detonator, then fall off. Thus, to use a grenade, the lever is grasped (to prevent release), then the pin is removed, and then the grenade is thrown, which releases the lever and ignites the detonator, triggering an explosion. Some grenade types also have a safety clip to prevent the handle from coming off in transit.

To use a grenade, the soldier grips it with the throwing hand, ensuring that the thumb holds the safety lever in place; if there is a safety clip, it is removed prior to use. Left-handed soldiers invert the grenade, so the thumb is still the digit that holds the safety lever. The soldier then grabs the safety pin's pull ring with the index or middle finger of the other hand and removes it. They then throw the grenade towards the target. Soldiers are trained to throw grenades in standing, prone-to-standing, kneeling, prone-to-kneeling, and alternative prone positions and in under- or side-arm throws. If the grenade is thrown from a standing position the thrower must then immediately seek cover or lie prone if no cover is nearby.

Once the soldier throws the grenade, the safety lever releases, the striker throws the safety lever away from the grenade body as it rotates to detonate the primer. The primer explodes and ignites the fuze (sometimes called the delay element). The fuze burns down to the detonator, which explodes the main charge.

When using an antipersonnel grenade, the objective is to have the grenade explode so that the target is within its effective radius. The M67 frag grenade has an advertised effective kill zone radius of , while the casualty-inducing radius is approximately . Within this range, people are generally injured badly enough to effectively render them harmless. These ranges only indicate the area where a target is virtually certain to be incapacitated; individual fragments can still cause injuries as far as away.

An alternative technique is to release the lever ''before'' throwing the grenade, which allows the fuze to burn partially and decrease the time to detonation after throwing; this is referred to as ''cooking''. A shorter delay is useful to reduce the ability of the enemy to take cover, throw or kick the grenade away and can also be used to allow a fragmentation grenade to explode into the air over defensive positions. This technique is inherently dangerous, due to shorter delay (meaning a closer explosion), greater complexity (must make sure to throw after waiting), and increased variability (fuzes vary from grenade to grenade), and thus is discouraged in the United States Marine Corps, U.S. Marine Corps, and banned in training. Nonetheless, cooking a grenade and throwing one back is frequently seen in Hollywood films and video games.

The classic hand grenade design has a safety handle or lever (known in the US forces as a ''spoon'') and a removable safety pin that prevents the handle from being released: the safety lever is spring-loaded, and once the safety pin is removed, the lever will release and ignite the detonator, then fall off. Thus, to use a grenade, the lever is grasped (to prevent release), then the pin is removed, and then the grenade is thrown, which releases the lever and ignites the detonator, triggering an explosion. Some grenade types also have a safety clip to prevent the handle from coming off in transit.

To use a grenade, the soldier grips it with the throwing hand, ensuring that the thumb holds the safety lever in place; if there is a safety clip, it is removed prior to use. Left-handed soldiers invert the grenade, so the thumb is still the digit that holds the safety lever. The soldier then grabs the safety pin's pull ring with the index or middle finger of the other hand and removes it. They then throw the grenade towards the target. Soldiers are trained to throw grenades in standing, prone-to-standing, kneeling, prone-to-kneeling, and alternative prone positions and in under- or side-arm throws. If the grenade is thrown from a standing position the thrower must then immediately seek cover or lie prone if no cover is nearby.

Once the soldier throws the grenade, the safety lever releases, the striker throws the safety lever away from the grenade body as it rotates to detonate the primer. The primer explodes and ignites the fuze (sometimes called the delay element). The fuze burns down to the detonator, which explodes the main charge.

When using an antipersonnel grenade, the objective is to have the grenade explode so that the target is within its effective radius. The M67 frag grenade has an advertised effective kill zone radius of , while the casualty-inducing radius is approximately . Within this range, people are generally injured badly enough to effectively render them harmless. These ranges only indicate the area where a target is virtually certain to be incapacitated; individual fragments can still cause injuries as far as away.

An alternative technique is to release the lever ''before'' throwing the grenade, which allows the fuze to burn partially and decrease the time to detonation after throwing; this is referred to as ''cooking''. A shorter delay is useful to reduce the ability of the enemy to take cover, throw or kick the grenade away and can also be used to allow a fragmentation grenade to explode into the air over defensive positions. This technique is inherently dangerous, due to shorter delay (meaning a closer explosion), greater complexity (must make sure to throw after waiting), and increased variability (fuzes vary from grenade to grenade), and thus is discouraged in the United States Marine Corps, U.S. Marine Corps, and banned in training. Nonetheless, cooking a grenade and throwing one back is frequently seen in Hollywood films and video games.

Grenades have often been used in the field to construct booby traps, using some action of the intended target (such as opening a door or starting a car) to trigger the grenade. These grenade-based booby traps are simple to construct in the field as long as instant fuzes are available; a delay in detonation can allow the intended target to take cover. The most basic technique involves wedging a grenade in a tight spot so the safety lever does not leave the grenade when the pin is pulled. A string is then tied from the head assembly to another stationary object. When a soldier steps on the string, the grenade is pulled out of the narrow passageway, the safety lever is released, and the grenade detonates.

Abandoned booby traps and discarded grenades contribute to the problem of unexploded ordnance (UXO). The use of target triggered grenades and AP mines is banned to the signatories of the Ottawa Treaty and may be treated as a war crime wherever it is ratified. Many countries, including India, the People's Republic of China, Russia, and the United States, have not signed the treaty citing self-defense needs.

Grenades have often been used in the field to construct booby traps, using some action of the intended target (such as opening a door or starting a car) to trigger the grenade. These grenade-based booby traps are simple to construct in the field as long as instant fuzes are available; a delay in detonation can allow the intended target to take cover. The most basic technique involves wedging a grenade in a tight spot so the safety lever does not leave the grenade when the pin is pulled. A string is then tied from the head assembly to another stationary object. When a soldier steps on the string, the grenade is pulled out of the narrow passageway, the safety lever is released, and the grenade detonates.

Abandoned booby traps and discarded grenades contribute to the problem of unexploded ordnance (UXO). The use of target triggered grenades and AP mines is banned to the signatories of the Ottawa Treaty and may be treated as a war crime wherever it is ratified. Many countries, including India, the People's Republic of China, Russia, and the United States, have not signed the treaty citing self-defense needs.

Stylized pictures of early grenades, emitting a flame, are used as ornaments on military uniforms, particularly in Britain, France (esp. French gendarmerie, French ''gendarmerie'' and the French Army), and Italy (''carabinieri''). Fusilier regiments in the British and Commonwealth tradition (e.g. the Princess Louise Fusiliers, Canadian Army) wear a cap-badge depicting flaming grenade, reflecting their historic use of grenades in the assault. The British Grenadier Guards took their name and cap badge of a burning grenade from repelling an attack of French grenadiers at Battle of Waterloo, Waterloo. The Spanish artillery arm uses a flaming grenade as its badge. The flag of the Russian Ground Forces also bears a flaming grenade device. Ukrainian Mechanized Infantry (Ukraine), mechanized infantry and engineers use a flaming grenade in their branch insignia. The Finnish Army Corps of Engineers' emblem consists of a stick hand grenade (symbolizing demolition) and a shovel (symbolizing construction) in saltire.

The branch insignia of the United States Army Ordnance Corps also uses this symbol, the grenade being symbolic of explosive ordnance in general. The United States Marine Corps uses the grenade as part of the insignia for one officer rank and one staff NCO rank on their uniforms. Chief warrant officers designated as marine gunners replace the rank insignia worn on the left collar with a "bursting bomb" and a larger "bursting bomb" insignia is worn above the rank insignia on both shoulder epaulets when a coat is worn. Additionally, the rank insignia for master gunnery sergeant has three chevrons pointing up, with four rockers on the bottom. In the middle of this is a bursting bomb or grenade. U.S. Navy aviation ordnanceman's rating badge features a winged device of similar design.

Stylized pictures of early grenades, emitting a flame, are used as ornaments on military uniforms, particularly in Britain, France (esp. French gendarmerie, French ''gendarmerie'' and the French Army), and Italy (''carabinieri''). Fusilier regiments in the British and Commonwealth tradition (e.g. the Princess Louise Fusiliers, Canadian Army) wear a cap-badge depicting flaming grenade, reflecting their historic use of grenades in the assault. The British Grenadier Guards took their name and cap badge of a burning grenade from repelling an attack of French grenadiers at Battle of Waterloo, Waterloo. The Spanish artillery arm uses a flaming grenade as its badge. The flag of the Russian Ground Forces also bears a flaming grenade device. Ukrainian Mechanized Infantry (Ukraine), mechanized infantry and engineers use a flaming grenade in their branch insignia. The Finnish Army Corps of Engineers' emblem consists of a stick hand grenade (symbolizing demolition) and a shovel (symbolizing construction) in saltire.

The branch insignia of the United States Army Ordnance Corps also uses this symbol, the grenade being symbolic of explosive ordnance in general. The United States Marine Corps uses the grenade as part of the insignia for one officer rank and one staff NCO rank on their uniforms. Chief warrant officers designated as marine gunners replace the rank insignia worn on the left collar with a "bursting bomb" and a larger "bursting bomb" insignia is worn above the rank insignia on both shoulder epaulets when a coat is worn. Additionally, the rank insignia for master gunnery sergeant has three chevrons pointing up, with four rockers on the bottom. In the middle of this is a bursting bomb or grenade. U.S. Navy aviation ordnanceman's rating badge features a winged device of similar design.

"Getting Good with the Grenade...It Pays!"

– November 1944 ''Popular Science'' article with complete history, cutaway, and illustrations

"How Grenades Work"

– from HowStuffWorks {{Authority control Grenades, Hand grenades, 8th-century introductions Byzantine inventions Incendiary weapons Infantry weapons Non-lethal weapons

A grenade is an explosive weapon typically thrown by hand (also called hand grenade), but can also refer to a shell (explosive

A grenade is an explosive weapon typically thrown by hand (also called hand grenade), but can also refer to a shell (explosive projectile

A projectile is an object that is propelled by the application of an external force and then moves freely under the influence of gravity and air resistance. Although any objects in motion through space are projectiles, they are commonly found in ...

) shot from the muzzle of a rifle

A rifle is a long-barreled firearm designed for accurate shooting, with a barrel that has a helical pattern of grooves ( rifling) cut into the bore wall. In keeping with their focus on accuracy, rifles are typically designed to be held with ...

(as a rifle grenade) or a grenade launcher

A grenade launcher is a weapon that fires a specially-designed large-caliber projectile, often with an explosive, smoke or gas warhead. Today, the term generally refers to a class of dedicated firearms firing unitary grenade cartridges. The mos ...

. A modern hand grenade generally consists of an explosive charge ("filler"), a detonator

A detonator, frequently a blasting cap, is a device used to trigger an explosive device. Detonators can be chemically, mechanically, or electrically initiated, the last two being the most common.

The commercial use of explosives uses electri ...

mechanism, an internal striker

Striker or The Strikers may refer to:

People

*A participant in a strike action

*A participant in a hunger strike

*Blacksmith's striker, a type of blacksmith's assistant

*Striker's Independent Society, the oldest mystic krewe in America

People wi ...

to trigger the detonator, and a safety lever secured by a cotter pin. The user removes the safety pin before throwing, and once the grenade leaves the hand the safety lever gets released, allowing the striker to trigger a primer

Primer may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''Primer'' (film), a 2004 feature film written and directed by Shane Carruth

* ''Primer'' (video), a documentary about the funk band Living Colour

Literature

* Primer (textbook), a t ...

that ignites a fuze

In military munitions, a fuze (sometimes fuse) is the part of the device that initiates function. In some applications, such as torpedoes, a fuze may be identified by function as the exploder. The relative complexity of even the earliest fuze d ...

(sometimes called the delay element), which burns down to the detonator and explodes the main charge.

Grenades work by dispersing fragments ( fragmentation grenades), shockwave

In physics, a shock wave (also spelled shockwave), or shock, is a type of propagating disturbance that moves faster than the local speed of sound in the medium. Like an ordinary wave, a shock wave carries energy and can propagate through a me ...

s ( high-explosive, anti-tank

Anti-tank warfare originated from the need to develop technology and tactics to destroy tanks during World War I. Since the Triple Entente deployed the first tanks in 1916, the German Empire developed the first anti-tank weapons. The first deve ...

and stun grenades), chemical aerosol

An aerosol is a suspension (chemistry), suspension of fine solid particles or liquid Drop (liquid), droplets in air or another gas. Aerosols can be natural or Human impact on the environment, anthropogenic. Examples of natural aerosols are fog o ...

s ( smoke and gas grenade

A grenade is an explosive weapon typically thrown by hand (also called hand grenade), but can also refer to a shell (explosive projectile) shot from the muzzle of a rifle (as a rifle grenade) or a grenade launcher. A modern hand grenade genera ...

s) or fire (incendiary grenade

A grenade is an explosive weapon typically thrown by hand (also called hand grenade), but can also refer to a shell (explosive projectile) shot from the muzzle of a rifle (as a rifle grenade) or a grenade launcher. A modern hand grenade gen ...

s). Fragmentation grenades ("frags") are probably the most common in modern armies, and when the word ''grenade'' is used in everyday speech, it is generally assumed to refer to a fragmentation grenade. Their outer casings, generally made of a hard Organic compound#Synthetic compounds, synthetic material or steel, are designed to Rupture (engineering), rupture and Fragmentation (weaponry), fragment on detonation, sending out numerous fragments (Sherd, shards and splinters) as fast-flying projectiles. In modern grenades, a pre-formed fragmentation matrix inside the grenade is commonly used, which may be spherical, cuboid, wire or notched wire. Most anti-personnel (AP) grenades are designed to detonate either after a time delay or on impact.

Grenades are often spherical, cylindrical, ovoid or truncated ovoid in shape, and of a size that fits the hand of a normal adult. Some grenades are mounted at the end of a handle and known as "stick grenades". The stick design provides Mechanical advantage, leverage for throwing longer distances, but at the cost of additional weight and length, and has been considered obsolete by western countries since the second World War and Cold War periods. A friction igniter inside the handle or on the top of the grenade head was used to initiate the fuse.

Etymology

The word ''grenade'' is likely derived from the French word spelled exactly the same, meaning pomegranate, as the bomb is reminiscent of the many-seeded fruit in size and shape. Its first use in English dates from the 1590s.History

Pre-gunpowder

Rudimentary incendiary grenades appeared in the Eastern Roman Empire, Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, not long after the reign of Leo III the Isaurian, Leo III (717–741).Robert James Forbes: "Studies in Ancient Technology," Leiden 1993, , p. 107 Byzantine soldiers learned that Greek fire, a Byzantine invention of the previous century, could not only be thrown by flamethrowers at the enemy but also in stone and ceramic jars. Later, glass containers were employed. The use of such explosive missiles soon spread to Muslim armies in the Near East, from where it reached China by the 10th century.

Rudimentary incendiary grenades appeared in the Eastern Roman Empire, Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, not long after the reign of Leo III the Isaurian, Leo III (717–741).Robert James Forbes: "Studies in Ancient Technology," Leiden 1993, , p. 107 Byzantine soldiers learned that Greek fire, a Byzantine invention of the previous century, could not only be thrown by flamethrowers at the enemy but also in stone and ceramic jars. Later, glass containers were employed. The use of such explosive missiles soon spread to Muslim armies in the Near East, from where it reached China by the 10th century.

Gunpowder

In China, during the Song Dynasty (960–1279 AD), weapons known as Zhen Tian Lei (, "Sky-shaking Thunder") were created when Chinese soldiers packed gunpowder into ceramic or metal containers fitted with fuses. In 1044, a military book ''Wujing Zongyao'' ("Compilation of Military Classics") described various gunpowder recipes in which one can find, according to Joseph Needham, the prototype of the modern hand grenade. The mid-14th-century book ''Huolongjing'' (, "Fire Dragon Manual"), written by Jiao Yu (), recorded an earlier Song-era cast-iron cannon known as the "flying-cloud thunderclap cannon" (; ). The manuscript stated that (Needham's modified Wade-Giles spelling):

In China, during the Song Dynasty (960–1279 AD), weapons known as Zhen Tian Lei (, "Sky-shaking Thunder") were created when Chinese soldiers packed gunpowder into ceramic or metal containers fitted with fuses. In 1044, a military book ''Wujing Zongyao'' ("Compilation of Military Classics") described various gunpowder recipes in which one can find, according to Joseph Needham, the prototype of the modern hand grenade. The mid-14th-century book ''Huolongjing'' (, "Fire Dragon Manual"), written by Jiao Yu (), recorded an earlier Song-era cast-iron cannon known as the "flying-cloud thunderclap cannon" (; ). The manuscript stated that (Needham's modified Wade-Giles spelling):

Grenade-like devices were also known in ancient India. In a 12th-century work Mujmalut Tawarikh based on an Arabic work which is itself based on original Sanskrit work, a terracotta elephant filled with explosives set with a Fuse (explosives), fuse was placed hidden in the van and exploded as the invading army approached near.

The first cast-iron bombshells and grenades appeared in Europe in 1467, where their initial role was with the besieging and defense of castles and fortifications.Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 179. A hoard of several hundred ceramic hand grenades was discovered during construction in front of a bastion of the Bavarian city of Ingolstadt, Germany dated to the 17th century. Many of the grenades retained their original black powder loads and igniters. The grenades were most likely intentionally dumped in the moat of the bastion prior to 1723. By the mid 17th century, infantry known as Grenadiers began to emerge in the armies of Europe, who specialized in shock and close quarters combat, mostly with the usage of grenades and fierce melee combat. In 1643, it is possible that "Grenados" were thrown amongst the Welsh at Holt, Wrexham, Holt Bridge during the English Civil War. The word "grenade" was also used during the events surrounding the Glorious Revolution in 1688, where cricket ball-sized ( in circumference) iron spheres packed with gunpowder and fitted with slow-burning wicks were first used against the Jacobitism, Jacobites in the battles of Battle of Killiecrankie, Killiecrankie and Battle of Glen Shiel, Glen Shiel. These grenades were not very effective owing both to the unreliability of their Fuse (explosives), fuse, as well inconsistent times to detonation, and as a result, saw little use. Grenades were also used during the Golden Age of Piracy, especially during boarding actions; pirate Captain Thompson used "vast numbers of powder flasks, grenade shells, and stinkpots" to defeat two pirate-hunters sent by the Governor of Jamaica in 1721.

Improvised grenades were increasingly used from the mid-19th century, the confines of trenches enhancing the effect of small explosive devices. In a letter to his sister, Colonel Hugh Robert Hibbert described an improvised grenade that was employed by British troops during the Crimean War (1854–1856):

In the American Civil War, both sides used hand grenades equipped with a plunger that detonated the device on impact. The Union (American Civil War), Union relied on experimental Ketchum Grenades, which had a tail to ensure that the nose would strike the target and start the fuze. The Confederacy (American Civil War), Confederacy used spherical hand grenades that weighed about , sometimes with a paper fuze. They also used 'Rains' and 'Adams' grenades, which were similar to the Ketchum in appearance and mechanism. Improvised hand grenades were also used to great effect by the Russian defenders of Port Arthur, China, Port Arthur during the Russo-Japanese War.

Grenade-like devices were also known in ancient India. In a 12th-century work Mujmalut Tawarikh based on an Arabic work which is itself based on original Sanskrit work, a terracotta elephant filled with explosives set with a Fuse (explosives), fuse was placed hidden in the van and exploded as the invading army approached near.

The first cast-iron bombshells and grenades appeared in Europe in 1467, where their initial role was with the besieging and defense of castles and fortifications.Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 179. A hoard of several hundred ceramic hand grenades was discovered during construction in front of a bastion of the Bavarian city of Ingolstadt, Germany dated to the 17th century. Many of the grenades retained their original black powder loads and igniters. The grenades were most likely intentionally dumped in the moat of the bastion prior to 1723. By the mid 17th century, infantry known as Grenadiers began to emerge in the armies of Europe, who specialized in shock and close quarters combat, mostly with the usage of grenades and fierce melee combat. In 1643, it is possible that "Grenados" were thrown amongst the Welsh at Holt, Wrexham, Holt Bridge during the English Civil War. The word "grenade" was also used during the events surrounding the Glorious Revolution in 1688, where cricket ball-sized ( in circumference) iron spheres packed with gunpowder and fitted with slow-burning wicks were first used against the Jacobitism, Jacobites in the battles of Battle of Killiecrankie, Killiecrankie and Battle of Glen Shiel, Glen Shiel. These grenades were not very effective owing both to the unreliability of their Fuse (explosives), fuse, as well inconsistent times to detonation, and as a result, saw little use. Grenades were also used during the Golden Age of Piracy, especially during boarding actions; pirate Captain Thompson used "vast numbers of powder flasks, grenade shells, and stinkpots" to defeat two pirate-hunters sent by the Governor of Jamaica in 1721.

Improvised grenades were increasingly used from the mid-19th century, the confines of trenches enhancing the effect of small explosive devices. In a letter to his sister, Colonel Hugh Robert Hibbert described an improvised grenade that was employed by British troops during the Crimean War (1854–1856):

In the American Civil War, both sides used hand grenades equipped with a plunger that detonated the device on impact. The Union (American Civil War), Union relied on experimental Ketchum Grenades, which had a tail to ensure that the nose would strike the target and start the fuze. The Confederacy (American Civil War), Confederacy used spherical hand grenades that weighed about , sometimes with a paper fuze. They also used 'Rains' and 'Adams' grenades, which were similar to the Ketchum in appearance and mechanism. Improvised hand grenades were also used to great effect by the Russian defenders of Port Arthur, China, Port Arthur during the Russo-Japanese War.

Development of modern grenades

Around the turn of the 20th century, the ineffectiveness of the available types of hand grenades, coupled with their levels of danger to the user and difficulty of operation, meant that they were regarded as increasingly obsolete pieces of military equipment. In 1902, the British War Office announced that hand grenades were obsolete and had no place in modern warfare. But within two years, following the success of improvised grenades in the trench warfare conditions of the Russo-Japanese War, and reports from Aylmer Haldane, General Sir Aylmer Haldane, a British observer of the conflict, a reassessment was quickly made and the Board of Ordnance was instructed to develop a practical hand grenade. Various models using a Fuse (explosives), percussion fuze were built, but this type of fuze suffered from various practical problems, and they were not commissioned in large numbers.

Marten Hale, better known for patenting the Hales rifle grenade, developed a modern hand grenade in 1906 but was unsuccessful in persuading the British Army to adopt the weapon until 1913. Hale's chief competitor was Nils Waltersen Aasen, who invented his design in 1906 in Norway, receiving a patent for it in England. Aasen began his experiments with developing a grenade while serving as a sergeant in the Oscarsborg Fortress. Aasen formed the ''Aasenske Granatkompani'' in Denmark, which before the First World War produced and exported hand grenades in large numbers across Europe. He had success in marketing his weapon to the French and was appointed as a Legion of Honour, Knight of the French Legion of Honour in 1916 for the invention.

The Royal Laboratory developed the No. 1 grenade in 1908. It contained explosive material with an iron Fragmentation (weaponry), fragmentation band, with an impact Fuse (explosives), fuze, detonating when the top of the grenade hit the ground. A long cane handle (approximately 16 inches or 40 cm) allowed the user to throw the grenade farther than the blast of the explosion. It suffered from the handicap that the percussion fuse was armed before throwing, which meant that if the user was in a trench or other confined space, he was apt to detonate it and kill himself when he drew back his arm to throw it.

Early in World War I, combatant nations only had small grenades, similar to Hales' and Aasen's design. The Italian Besozzi grenade had a five-second fuze with a match-tip that was ignited by striking on a ring on the soldier's hand. As an interim measure, troops often improvised their own grenades, such as the jam tin grenade.

Around the turn of the 20th century, the ineffectiveness of the available types of hand grenades, coupled with their levels of danger to the user and difficulty of operation, meant that they were regarded as increasingly obsolete pieces of military equipment. In 1902, the British War Office announced that hand grenades were obsolete and had no place in modern warfare. But within two years, following the success of improvised grenades in the trench warfare conditions of the Russo-Japanese War, and reports from Aylmer Haldane, General Sir Aylmer Haldane, a British observer of the conflict, a reassessment was quickly made and the Board of Ordnance was instructed to develop a practical hand grenade. Various models using a Fuse (explosives), percussion fuze were built, but this type of fuze suffered from various practical problems, and they were not commissioned in large numbers.

Marten Hale, better known for patenting the Hales rifle grenade, developed a modern hand grenade in 1906 but was unsuccessful in persuading the British Army to adopt the weapon until 1913. Hale's chief competitor was Nils Waltersen Aasen, who invented his design in 1906 in Norway, receiving a patent for it in England. Aasen began his experiments with developing a grenade while serving as a sergeant in the Oscarsborg Fortress. Aasen formed the ''Aasenske Granatkompani'' in Denmark, which before the First World War produced and exported hand grenades in large numbers across Europe. He had success in marketing his weapon to the French and was appointed as a Legion of Honour, Knight of the French Legion of Honour in 1916 for the invention.

The Royal Laboratory developed the No. 1 grenade in 1908. It contained explosive material with an iron Fragmentation (weaponry), fragmentation band, with an impact Fuse (explosives), fuze, detonating when the top of the grenade hit the ground. A long cane handle (approximately 16 inches or 40 cm) allowed the user to throw the grenade farther than the blast of the explosion. It suffered from the handicap that the percussion fuse was armed before throwing, which meant that if the user was in a trench or other confined space, he was apt to detonate it and kill himself when he drew back his arm to throw it.

Early in World War I, combatant nations only had small grenades, similar to Hales' and Aasen's design. The Italian Besozzi grenade had a five-second fuze with a match-tip that was ignited by striking on a ring on the soldier's hand. As an interim measure, troops often improvised their own grenades, such as the jam tin grenade.

Fragmentation grenade

Improvised grenades were replaced when manufactured versions became available. The first modern fragmentation grenade was the Mills bomb, which became available to British front-line troops in 1915.

William Mills (inventor), William Mills, a hand grenade designer from Sunderland, Tyne and Wear, Sunderland, patented, developed and manufactured the "Mills bomb" at the Mills Munition Factory in Birmingham, England in 1915, designating it the No.5. It was described as the first "safe grenade." They were explosive-filled steel canisters with a triggering pin and a distinctive deeply notched surface. This segmentation is often erroneously thought to aid fragmentation (weaponry), fragmentation, though Mills' own notes show the external grooves were purely to aid the soldier to grip the weapon. Improved fragmentation designs were later made with the notches on the inside, but at that time they would have been too expensive to produce. The external segmentation of the original Mills bomb was retained, as it provided a positive :wikt:grip, grip surface. This basic "pin-and-pineapple" design is still used in some modern grenades.

The Mills bomb underwent numerous modifications. The No. 23 was a variant of the No. 5 with a rodded base plug which allowed it to be rifle grenade, fired from a rifle. This concept evolved further with the No. 36, a variant with a detachable base plate to allow use with a rifle discharger cup. The final variation of the Mills bomb, the No. 36M, was specially designed and waterproofed with shellac for use initially in the hot climate of Mesopotamia in 1917, and remained in production for many years. By 1918, the No. 5 and No. 23 were declared obsolete and the No. 36 (but not the 36M) followed in 1932.

The Mills had a grooved cast-iron "pineapple" with a central striker held by a close hand lever and secured with a pin. A competent thrower could manage with reasonable accuracy, but the grenade could throw lethal fragments farther than this; after throwing, the user had to take cover immediately. The British Home Guard was instructed that the throwing range of the No. 36 was about with a danger area of about .

Approximately 75,000,000 grenades were manufactured during World War I, used in the war and remaining in use through to the World War II, Second World War. At first, the grenade was fitted with a seven-second fuze, but during combat in the Battle of France in 1940, this delay proved too long, giving defenders time to escape the explosion or to throw the grenade back, so the delay was reduced to four seconds.

The F1 grenade (France), F1 grenade was first produced in limited quantities by France in May 1915. This new weapon had improvements from the experience of the first months of the war: the shape was more modern, with an external groove pattern for better grip and easier fragmentation. The second expectation proved deceptive, as the explosion in practice gave no more than 10 fragments (although the pattern was designed to split into all the 38 drawn divisions). The design proved to be very functional, especially due to its stability compared to other grenades of the same period. The F1 was used by many foreign armies from 1915 to 1940.

Improvised grenades were replaced when manufactured versions became available. The first modern fragmentation grenade was the Mills bomb, which became available to British front-line troops in 1915.

William Mills (inventor), William Mills, a hand grenade designer from Sunderland, Tyne and Wear, Sunderland, patented, developed and manufactured the "Mills bomb" at the Mills Munition Factory in Birmingham, England in 1915, designating it the No.5. It was described as the first "safe grenade." They were explosive-filled steel canisters with a triggering pin and a distinctive deeply notched surface. This segmentation is often erroneously thought to aid fragmentation (weaponry), fragmentation, though Mills' own notes show the external grooves were purely to aid the soldier to grip the weapon. Improved fragmentation designs were later made with the notches on the inside, but at that time they would have been too expensive to produce. The external segmentation of the original Mills bomb was retained, as it provided a positive :wikt:grip, grip surface. This basic "pin-and-pineapple" design is still used in some modern grenades.

The Mills bomb underwent numerous modifications. The No. 23 was a variant of the No. 5 with a rodded base plug which allowed it to be rifle grenade, fired from a rifle. This concept evolved further with the No. 36, a variant with a detachable base plate to allow use with a rifle discharger cup. The final variation of the Mills bomb, the No. 36M, was specially designed and waterproofed with shellac for use initially in the hot climate of Mesopotamia in 1917, and remained in production for many years. By 1918, the No. 5 and No. 23 were declared obsolete and the No. 36 (but not the 36M) followed in 1932.

The Mills had a grooved cast-iron "pineapple" with a central striker held by a close hand lever and secured with a pin. A competent thrower could manage with reasonable accuracy, but the grenade could throw lethal fragments farther than this; after throwing, the user had to take cover immediately. The British Home Guard was instructed that the throwing range of the No. 36 was about with a danger area of about .