Fort Shaw Indian School on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Fort Shaw (originally named Camp Reynolds) was a

Major William Clinton's command of Fort Shaw was only temporary. On August 11, 1867, Colonel I. V. D. Reeves transferred the 13th Infantry Regiment's headquarters to Fort Shaw. Lieutenant Colonel G. L. Andrews was regimental second-in-command, and named headquarters commandant, overseeing the operations of the fort itself. During their tenure at the fort, a steam engine was brought in to pump water from the river to the kitchens and sinks. The unit also received

Major William Clinton's command of Fort Shaw was only temporary. On August 11, 1867, Colonel I. V. D. Reeves transferred the 13th Infantry Regiment's headquarters to Fort Shaw. Lieutenant Colonel G. L. Andrews was regimental second-in-command, and named headquarters commandant, overseeing the operations of the fort itself. During their tenure at the fort, a steam engine was brought in to pump water from the river to the kitchens and sinks. The unit also received

Just five years later, in 1874, gold was discovered by the U.S. Army in the

Just five years later, in 1874, gold was discovered by the U.S. Army in the

Fort Shaw Web site

National Register of Historic Places in Cascade County, Montana

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

fort

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

located on the Sun River

The Sun River (also called the Medicine River) is a tributary of the Missouri River in the Great Plains, approximately 130 mi (209 km) long, in Montana in the United States.

It rises in the Rocky Mountains in two forks, the North Fork ...

24 miles west of Great Falls, Montana

Great Falls is the third most populous city in the U.S. state of Montana and the county seat of Cascade County. The population was 60,442 according to the 2020 census. The city covers an area of and is the principal city of the Great Falls, M ...

, in the United States. It was founded on June 30, 1867, and abandoned by the Army in July 1891. It later served as a school for Native American children from 1892 to 1910. Portions of the fort survive today as a small museum. The fort lent its name to the community of Fort Shaw, Montana

Fort Shaw is a census-designated place (CDP) in Cascade County, Montana, United States. The population was 280 at the 2010 census. Named for a former United States military outpost, it is part of the Great Falls, Montana Metropolitan Statistical ...

, which grew up around it.

Fort Shaw is part of the Fort Shaw Historic District and Cemetery, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic v ...

on January 11, 1985.

Founding the fort

Most of what was to become Montana became part of the United States with theLouisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

of 1803. Although first organized into an incorporated territory in 1805 as part of the Louisiana Territory

The Territory of Louisiana or Louisiana Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1805, until June 4, 1812, when it was renamed the Missouri Territory. The territory was formed out of the ...

, it was not until large numbers of farmers, miners, and fur trappers began moving into the region in the 1850s that the government of the United States paid much attention to the area. The creation of the Montana Territory

The Territory of Montana was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 26, 1864, until November 8, 1889, when it was admitted as the 41st state in the Union as the state of Montana.

Original boundaries

T ...

in 1864 came about, in part, due to the rapid influx of miners after the gold strikes of 1862 to 1864 in the southwest part of the state.

Camp Reynolds was established on the site on June 30, 1867. The camp was established by Major William Clinton, in command of four companies

A company, abbreviated as co., is a legal entity representing an association of people, whether natural, legal or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members share a common purpose and unite to achieve specific, declared go ...

of the 13th Infantry Regiment. The site was about upstream from the confluence of the Sun and Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

rivers. It was about upstream from the point where the Mullan Road

Mullan Road was the first wagon road to cross the Rocky Mountains to the Inland of the Pacific Northwest. It was built by U.S. Army troops under the command of Lt. John Mullan, between the spring of 1859 and summer 1860. It led from Fort Benton, ...

crossed the river. It was also about upstream from the site of the former St. Peter's Mission, which had been evacuated in April 1866 after the Piegan Blackfeet

The Piegan ( Blackfoot: ''Piikáni'') are an Algonquian-speaking people from the North American Great Plains. They were the largest of three Blackfoot-speaking groups that made up the Blackfoot Confederacy; the Siksika and Kainai were the oth ...

killed four white settlers nearby (one almost on the doorstep of the mission). The first Blackfeet Indian Agency office, established in 1854 by Isaac Stevens

Isaac Ingalls Stevens (March 25, 1818 – September 1, 1862) was an American military officer and politician who served as governor of the Territory of Washington from 1853 to 1857, and later as its delegate to the United States House of Represen ...

(Governor of the Washington Territory), was also nearby. The 13th Infantry Regiment previously established Camp Cooke near the mouth of the Judith River

The Judith River is a tributary of the Missouri River, approximately 124 mi (200 km) long, running through central Montana in the United States. It rises in the Little Belt Mountains and flows northeast past Utica and Hobson. It is ...

in July 1866, and Camp Reynolds was intended to keep the Mullan Road

Mullan Road was the first wagon road to cross the Rocky Mountains to the Inland of the Pacific Northwest. It was built by U.S. Army troops under the command of Lt. John Mullan, between the spring of 1859 and summer 1860. It led from Fort Benton, ...

open and prohibit further Native American attacks on settlements to the south.

On July 4, 1867, the United States Department of the Army

The United States Department of the Army (DA) is one of the three military departments within the United States Department of Defense, Department of Defense of the U.S. The Department of the Army is the Federal government of the United States ...

issued orders to have the name of the encampment changed to Fort Shaw in honor of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw

Robert Gould Shaw (October 10, 1837 – July 18, 1863) was an American officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War. Born into a prominent Boston Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist family, he accepted command of the firs ...

, a Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

officer who commanded the all-black 54th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry

The 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment that saw extensive service in the Union Army during the American Civil War. The unit was the second African-American regiment, following the 1st Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry R ...

during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

. The post's name was changed on August 1, 1867. Initially, Fort Shaw was to have had barracks space for six companies of infantry, but this was scaled back to four companies after the U.S. Army decided to build Fort Ellis

Fort Ellis was a United States Army fort established August 27, 1867, east of present-day Bozeman, Montana. Troops from the fort participated in many major campaigns of the Indian Wars. The fort was closed on August 2, 1886.

History

The fort w ...

near present-day Bozeman, Montana

Bozeman is a city and the county seat of Gallatin County, Montana, United States. Located in southwest Montana, the 2020 census put Bozeman's population at 53,293, making it the fourth-largest city in Montana. It is the principal city of th ...

. Fort Shaw, along with Fort Ellis, was one of two principal U.S. Army forts intended to protect the burgeoning mining settlements of south-central and southwest Montana.

Construction of the fort

When first established, Fort Shaw consisted of officers and men housed in canvas tents. Construction of log cabin housing began in August 1867, and by late fall the men had constructed barracks for half the soldiers, a temporary storehouse, and three officers' huts. But only half of the post hospital was erected before cold weather forced construction to halt and the men to enter winter quarters. The finished buildings were only barely habitable and the men and officers very cramped, but the winter was not a harsh one. The remaining structures were raised and finished in the spring and summer of 1868. During 1869, the structures were made more comfortable and military decorations added. Floors were hard-packed dirt (and remained so throughout the fort's existence). Fort Shaw was constructed around a square parade ground on each side. The interior and exterior building walls were made ofadobe

Adobe ( ; ) is a building material made from earth and organic materials. is Spanish for ''mudbrick''. In some English-speaking regions of Spanish heritage, such as the Southwestern United States, the term is used to refer to any kind of e ...

bricks in size. Exterior walls were thick, while interior walls were thick. The interior walls of the seven officers' quarters were finished in white plaster, and had glass windows set in white-painted wood casements. There were four U-shaped infantry barracks, each on a side and with ceilings. Barracks walls were unfinished, and had four windows ( in size). Each barracks contained several rooms: A sergeant's room (), a storeroom (), a mess

The mess (also called a mess deck aboard ships) is a designated area where military personnel socialize, eat and (in some cases) live. The term is also used to indicate the groups of military personnel who belong to separate messes, such as the o ...

room (), kitchen (), laundry (), and sleeping quarters/recreation room (). Roofs were boards at first, but shingled as shingles became available.

A number of other buildings were also constructed. These included a commissary

A commissary is a government official charged with oversight or an ecclesiastical official who exercises in special circumstances the jurisdiction of a bishop.

In many countries, the term is used as an administrative or police title. It often c ...

and quartermaster

Quartermaster is a military term, the meaning of which depends on the country and service. In land armies, a quartermaster is generally a relatively senior soldier who supervises stores or barracks and distributes supplies and provisions. In m ...

storehouse (), which in its interior included a commissary officer's office (); a company clerk's office (); a room for issuing stores (); two storerooms (); and a quartermaster's office (). The U-shaped storehouse also had a cellar and a () yard, enclosed by a gate. Other buildings included a guardhouse (with stone prison cells) and quarters for the company band (, with a high ceiling); a T-shaped hospital (); two-story commanding officer's quarters (), with bedroom, dining room, sitting room, kitchen, servants' room, and two garret

A garret is a habitable attic, a living space at the top of a house or larger residential building, traditionally, small, dismal, and cramped, with sloping ceilings. In the days before elevators this was the least prestigious position in a bu ...

rooms; and duplex officers' quarters (), each including a front room, back room, kitchen, servants' room, garret room, and a shared single mess room. A chapel, post school, library, bakery, ordnance (weapons and ammunition) room, magazine

A magazine is a periodical publication, generally published on a regular schedule (often weekly or monthly), containing a variety of content. They are generally financed by advertising, purchase price, prepaid subscriptions, or by a combinatio ...

, water tanks, outhouse

An outhouse is a small structure, separate from a main building, which covers a toilet. This is typically either a pit latrine or a bucket toilet, but other forms of dry toilet, dry (non-flushing) toilets may be encountered. The term may als ...

s, and outdoor brick washing sinks made up the rest of the post.

Fort Shaw was so well laid out and so beautifully constructed that it was called the "queen of Montana's military posts".

A cemetery

A cemetery, burial ground, gravesite or graveyard is a place where the remains of dead people are buried or otherwise interred. The word ''cemetery'' (from Greek , "sleeping place") implies that the land is specifically designated as a buri ...

was located west of the post, and a vegetable garden about east.

Life at the fort

The military reservation extended along the length of the Sun River Valley from present-dayVaughn, Montana

Vaughn is a census-designated place (CDP) in Cascade County, Montana, United States. The population was 658 at the 2010 census. It is part of the Great Falls, Montana Metropolitan Statistical Area. It is named for Montana pioneer Robert Vaughn, w ...

, upstream for . Fort Shaw was located almost on the slopes of Shaw Butte, which was two-thirds of the way up the valley to the west, and was about above the river. The river was shallow and easily forded almost anywhere along its length, except during the spring freshets.

Food was largely imported. A limited supply of fish was obtained from the Sun River, which at that time was a clear, swift-running stream with a stony bottom. Wild game (bighorn sheep

The bighorn sheep (''Ovis canadensis'') is a species of sheep native to North America. It is named for its large horns. A pair of horns might weigh up to ; the sheep typically weigh up to . Recent genetic testing indicates three distinct subspec ...

, black-tailed deer

Two forms of black-tailed deer or blacktail deer that occupy coastal woodlands in the Pacific Northwest of North America are subspecies of the mule deer (''Odocoileus hemionus''). They have sometimes been treated as a species, but virtually all r ...

, elk

The elk (''Cervus canadensis''), also known as the wapiti, is one of the largest species within the deer family, Cervidae, and one of the largest terrestrial mammals in its native range of North America and Central and East Asia. The common ...

, pronghorn

The pronghorn (, ) (''Antilocapra americana'') is a species of artiodactyl (even-toed, hoofed) mammal indigenous to interior western and central North America. Though not an antelope, it is known colloquially in North America as the American a ...

, and white-tailed deer

The white-tailed deer (''Odocoileus virginianus''), also known as the whitetail or Virginia deer, is a medium-sized deer native to North America, Central America, and South America as far south as Peru and Bolivia. It has also been introduced t ...

), duck

Duck is the common name for numerous species of waterfowl in the family Anatidae. Ducks are generally smaller and shorter-necked than swans and geese, which are members of the same family. Divided among several subfamilies, they are a form t ...

s, geese

A goose (plural, : geese) is a bird of any of several waterfowl species in the family (biology), family Anatidae. This group comprises the genera ''Anser (bird), Anser'' (the grey geese and white geese) and ''Branta'' (the black geese). Some o ...

, prairie chicken

''Tympanuchus'' is a small genus of Aves, birds in the grouse family. They are commonly referred to as prairie chickens.

Taxonomy

The genus ''Tympanuchus'' was introduced in 1841 by the German zoologist C. L. Gloger, Constantin Wilhelm Lambert ...

, rabbit

Rabbits, also known as bunnies or bunny rabbits, are small mammals in the family Leporidae (which also contains the hares) of the order Lagomorpha (which also contains the pikas). ''Oryctolagus cuniculus'' includes the European rabbit speci ...

s, and sage-grouse

Sage-grouse are grouse belonging to the bird genus ''Centrocercus.'' The genus includes two species: the Gunnison grouse (''Centrocercus minimus'') and the greater sage-grouse (''Centrocercus urophasianus''). These birds are distributed through ...

were often hunted for food, but were scarce in the area and not relied on heavily for food. Nearby ranches supplied the post with vegetables, albeit at very high prices. Flour was usually shipped in from the east, as the Montana-grown summer wheat produced bread which was dark and heavy.

Fuel was scarce. Wood grew only sparsely in the valley, and the post imported wood logs for fuel and construction at the cost of from the foothills of the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico in ...

about to the west. Lignite

Lignite, often referred to as brown coal, is a soft, brown, combustible, sedimentary rock formed from naturally compressed peat. It has a carbon content around 25–35%, and is considered the lowest rank of coal due to its relatively low heat ...

coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when dea ...

was obtained from mines in the Dearborn River

The Dearborn River is a tributary of the Missouri River, approximately 70 mi (113 km) long, in central Montana in the United States. It rises in the Lewis and Clark National Forest, near Scapegoat Mountain in the Lewis and Clark Ran ...

valley, about away, and used for both heating and cooking.

Water, too, was a problem. The valley was very well-drained by the river, and no springs were located near the post. Water was obtained by digging a long trench from the river to the post. Although a steam engine was later used to pump water from the river to various building via wooden pipes, these pipes often became clogged or froze in winter. Below-ground wooden pipes were laid in 1885 to rectify the problem.

Forage for animals was also an issue. Since the strong drainage inhibited the growth of grass, hay

Hay is grass, legumes, or other herbaceous plants that have been cut and dried to be stored for use as animal fodder, either for large grazing animals raised as livestock, such as cattle, horses, goats, and sheep, or for smaller domesticated ...

had to be imported from elsewhere in Montana, primarily the Missouri River valley to the east.

Disease was common. Influenza

Influenza, commonly known as "the flu", is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These symptoms ...

, fever

Fever, also referred to as pyrexia, is defined as having a body temperature, temperature above the human body temperature, normal range due to an increase in the body's temperature Human body temperature#Fever, set point. There is not a single ...

, and diarrhea

Diarrhea, also spelled diarrhoea, is the condition of having at least three loose, liquid, or watery bowel movements each day. It often lasts for a few days and can result in dehydration due to fluid loss. Signs of dehydration often begin wi ...

(particularly in the spring) were common. Although smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

regularly killed hundreds of Native Americans in the area each year, few members of the Army came down with the disease.

Fort Shaw was not an isolated post. Mail was delivered three times a week, the fort served as a post office

A post office is a public facility and a retailer that provides mail services, such as accepting letters and parcels, providing post office boxes, and selling postage stamps, packaging, and stationery. Post offices may offer additional serv ...

for the local populace, and there was a telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

office for both civilian and military use.

History of the fort

Early leadership

Major William Clinton's command of Fort Shaw was only temporary. On August 11, 1867, Colonel I. V. D. Reeves transferred the 13th Infantry Regiment's headquarters to Fort Shaw. Lieutenant Colonel G. L. Andrews was regimental second-in-command, and named headquarters commandant, overseeing the operations of the fort itself. During their tenure at the fort, a steam engine was brought in to pump water from the river to the kitchens and sinks. The unit also received

Major William Clinton's command of Fort Shaw was only temporary. On August 11, 1867, Colonel I. V. D. Reeves transferred the 13th Infantry Regiment's headquarters to Fort Shaw. Lieutenant Colonel G. L. Andrews was regimental second-in-command, and named headquarters commandant, overseeing the operations of the fort itself. During their tenure at the fort, a steam engine was brought in to pump water from the river to the kitchens and sinks. The unit also received breech-loading

A breechloader is a firearm in which the user loads the ammunition (cartridge or shell) via the rear (breech) end of its barrel, as opposed to a muzzleloader, which loads ammunition via the front ( muzzle).

Modern firearms are generally breech ...

rifles, which greatly increased its effectiveness. About 33 civilians were employed at the fort as well, working as blacksmiths, carpenters, clerks, masons, and saddlers. One of Colonel Reeves' first actions was to disarm the Montana Militia, a short-lived paramilitary organization formed by Acting Governor Thomas Francis Meagher

Thomas Francis Meagher (; 3 August 18231 July 1867) was an Irish nationalist and leader of the Young Irelanders in the Rebellion of 1848. After being convicted of sedition, he was first sentenced to death, but received transportation for life ...

in 1864 and supplied with arms by the U.S. Army. Reeves acted quickly, and the militia was disbanded by October 1, 1867.

General Phillipe Régis de Trobriand took command of Fort Shaw on June 4, 1869. A steam engine (whether a second one or a replacement is unclear) was brought to the fort in 1869. Excessive drinking and desertion by his troops were a constant problem. General Trobriand and the 13th Infantry Regiment left Fort Shaw on June 11, 1870. His unit was replaced by the headquarters company and six companies of the 7th Infantry Regiment, commanded by Colonel John Gibbon

John Gibbon (April 20, 1827 – February 6, 1896) was a career United States Army officer who fought in the American Civil War and the Indian Wars.

Early life

Gibbon was born in the Holmesburg section of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the fourt ...

.

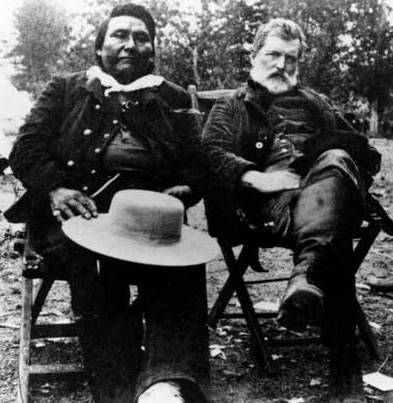

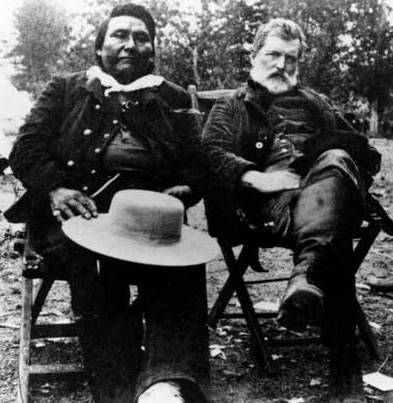

Command of Colonel Gibbon and fighting in the Indian Wars

Gibbon worked to improve living conditions at Fort Shaw. He improved the roofing of the barracks buildings, had the exterior walls of all buildings plastered, expanded the storehouses, and expanded and improved the corrals and stables. Irrigation for the fort's vegetable garden was completed, and companies assigned to maintain each plot. In 1871, he obtained a plow for tilling the garden. He also worked to expand the fort's civilian workforce, adding carpenters, masons, and sawmill operators. Desertion and theft of fort supplies, both major problems, were also reduced. Gibbon also worked to improve security in the area. He began surveying and constructing a road between Fort Shaw and Camp Baker (near present-day White Sulphur Springs) to provide better communications with that post and to better monitor the movements of Native American groups and bands. This so improved security in the area that Gibbon counseled against the construction of ablockhouse

A blockhouse is a small fortification, usually consisting of one or more rooms with loopholes, allowing its defenders to fire in various directions. It is usually an isolated fort in the form of a single building, serving as a defensive stro ...

at Camp Baker because it would send a signal to whites that the area was still not free from Native American attack. Gibbon also used his troops to scout out the little-explored area of the Rocky Mountain Front

The Rocky Mountain Front is a somewhat unified geologic and ecosystem area in North America where the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains meet the plains. In 1983, the Bureau of Land Management called the Rocky Mountain Front "a nationally signif ...

. These explorations led to the rediscovery and accurate mapping of Lewis and Clark Pass.

The area around Fort Shaw was a hotbed of conflict between Native Americans and white settlers in the late 1860s. A series of Piegan Blackfeet and Sioux

The Sioux or Oceti Sakowin (; Dakota language, Dakota: Help:IPA, /otʃʰeːtʰi ʃakoːwĩ/) are groups of Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribes and First Nations in Canada, First Nations peoples in North America. The ...

raids between 1865 and 1869 left several whites dead. In mid-1869, two innocent Piegan Blackfeet were killed in retaliation in broad daylight in the town of Fort Benton, Montana

Fort Benton is a city in and the county seat of Chouteau County, Montana, United States. Established in 1846, Fort Benton is the oldest continuously occupied settlement in Montana. The city's waterfront area, the most important aspect of its 1 ...

, about to the northeast of Fort Shaw. One of them was the brother of the Piegan leader Mountain Chief

Mountain Chief (''Ninna-stako'' in the Blackfoot language; – 1942) was a South Piegan warrior of the Blackfoot Tribe. Mountain Chief was also called Big Brave (Omach-katsi) and adopted the name Frank Mountain Chief. Mountain Chief was involved ...

, who initiated a series of reprisals which killed about 25 white settlers. In response, General Philip Sheridan

General of the Army Philip Henry Sheridan (March 6, 1831 – August 5, 1888) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the American Civil War. His career was noted for his rapid rise to major general and his close as ...

ordered Major Eugene Baker to take two companies of the 2d Cavalry Regiment from Fort Ellis and two companies of infantry from Fort Shaw and attack Mountain Chief's band of Piegans. Baker attacked the Piegans on the morning of January 23, 1870. Unfortunately, he attacked the wrong band: The Piegans were led by Heavy Runner, a Piegan Blackfeet who had signed a peace agreement with the United States. When Heavy Runner rushed out of his camp with his peace treaty in hand, he was shot dead. In what became known as the Marias Massacre

The Marias Massacre (also known as the Baker Massacre or the Piegan Massacre) was a massacre of Piegan Blackfeet Native peoples which was committed by the United States Army as part of the Indian Wars. The massacre took place on January 23, 1870, ...

, more than 173 Piegean Blackfeet (including 53 women and children) were murdered.

Just five years later, in 1874, gold was discovered by the U.S. Army in the

Just five years later, in 1874, gold was discovered by the U.S. Army in the Black Hills

The Black Hills ( lkt, Ȟe Sápa; chy, Moʼȯhta-voʼhonáaeva; hid, awaxaawi shiibisha) is an isolated mountain range rising from the Great Plains of North America in western South Dakota and extending into Wyoming, United States. Black Elk P ...

of the Dakotas. A gold rush

A gold rush or gold fever is a discovery of gold—sometimes accompanied by other precious metals and rare-earth minerals—that brings an onrush of miners seeking their fortune. Major gold rushes took place in the 19th century in Australia, New Z ...

occurred in 1875 and 1876 in which thousands of white miners and settlers flooded the area in violation of several treaties guaranteeing that the Black Hills would belong to the Lakota people. Conflict between Native Americans and white settlers broke out. Responding to pleas from whites, President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

decided to clear the Black Hills of all native people. After an attack

Attack may refer to:

Warfare and combat

* Offensive (military)

* Charge (warfare)

* Attack (fencing)

* Strike (attack)

* Attack (computing)

* Attack aircraft

Books and publishing

* ''The Attack'' (novel), a book

* '' Attack No. 1'', comic an ...

against a combined Sioux-Cheyenne

The Cheyenne ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. Their Cheyenne language belongs to the Algonquian language family. Today, the Cheyenne people are split into two federally recognized nations: the Southern Cheyenne, who are enroll ...

village on the Powder River by General George Crook

George R. Crook (September 8, 1828 – March 21, 1890) was a career United States Army officer, most noted for his distinguished service during the American Civil War and the Indian Wars. During the 1880s, the Apache nicknamed Crook ''Nantan ...

accomplished little in March 1876, General Sheridan decided on a three-pronged attack to occur in southwestern Montana in the summer of 1876. Colonel Gibbon was ordered to form a "Montana Column" from elements of at Fort Shaw and Fort Ellis, and to march south across the plains to ensure that no Native American tribes moved north or west of the Yellowstone River

The Yellowstone River is a tributary of the Missouri River, approximately long, in the Western United States. Considered the principal tributary of upper Missouri, via its own tributaries it drains an area with headwaters across the mountains an ...

. After reaching the Yellowstone, he was to move downstream until he rendezvoused with a "Dakota Column", under the command of General Alfred Terry

Alfred Howe Terry (November 10, 1827 – December 16, 1890) was a Union general in the American Civil War and the military commander of the Dakota Territory from 1866 to 1869, and again from 1872 to 1886. In 1865, Terry led Union troops to vic ...

. Gibbon left Fort Shaw on March 17, 1877, with five companies (about 200 men and 12 officers), and reached Fort Ellis on March 22. In April, Gibbon left Fort Ellis with both infantry and cavalry (totalling about 450 men and officers), heading for the Yellowstone. On June 20, Gibbon's command rendezvoused with Terry at the mouth of the Rosebud River

The Rosebud River is a major tributary of the Red Deer River in Alberta, Canada. The Rosebud River passes through agricultural lands and ranchland for most of its course, and through badlands in its final reaches. It provides water for irri ...

. General Terry ordered his subordinate, Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer

George Armstrong Custer (December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876) was a United States Army officer and cavalry commander in the American Civil War and the American Indian Wars.

Custer graduated from West Point in 1861 at the bottom of his class, b ...

, to proceed south along the Rosebud and then west to the Little Bighorn River. Custer was to follow the Little Bighorn River north to the Bighorn River

The Bighorn River is a tributary of the Yellowstone, approximately long, in the states of Wyoming and Montana in the western United States. The river was named in 1805 by fur trader François Larocque for the bighorn sheep he saw along its ban ...

, where he was to rendezvous with Gibbon and Terry—who were to proceed west along the Yellowstone to the Bighorn, and then south along the Bighorn to meet Custer. Subsequently, Gibbon's Fort Shaw soldiers did not participate in the Battle of the Little Bighorn

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, and also commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Nor ...

on June 25–26, during which most of Custer's command was famously wiped out. Gibbon entered the valley of the Little Bighorn on June 27, where the Fort Shaw soldiers assisted in burying the dead.

Soldiers at Fort Shaw participated in another famous Indian battle in 1877. For many years, several bands of the Nez Perce people

The Nez Percé (; autonym in Nez Perce language: , meaning "we, the people") are an Indigenous people of the Plateau who are presumed to have lived on the Columbia River Plateau in the Pacific Northwest region for at least 11,500 years.Ames, K ...

lived in the valley of the Wallowa River

The Wallowa River is a tributary of the Grande Ronde River, approximately long, in northeastern Oregon in the United States. It drains a valley on the Columbia Plateau in the northeast corner of the state north of Wallowa Mountains.

The Wallowa ...

in northeast Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

. But increasing white settlement in the area led to calls to have the Native Americans placed on a reservation. In May 1877, General Oliver O. Howard

Oliver Otis Howard (November 8, 1830 – October 26, 1909) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the Civil War. As a brigade commander in the Army of the Potomac, Howard lost his right arm while leading his men against ...

ordered all remaining Nez Perce onto a reservation with 30 days. Several young Native Americans killed some white settlers, leading to a reprisal by General Howard. Yet, in the Battle of White Bird Canyon

The Battle of White Bird Canyon was fought on June 17, 1877, in Idaho Territory. White Bird Canyon was the opening battle of the Nez Perce War between the Nez Perce Indians and the United States. The battle was a significant defeat of the U.S. ...

on June 17, 1877, a force of about 80 Nez Perce warriors defeated a unit of 200 of Howard's artillery, cavalry, and infantry. More than 800 Nez Perce men, women, and children tried to flee over Lolo Pass into Montana to seek help from other tribes, which deeply alarmed whites in the Montana Territory. A hundred Nez Perce held off 500 U.S. Army troops at the Battle of the Clearwater

The Battle of the Clearwater (July 11–12, 1877) was a battle in the Idaho Territory between the Nez Perce under Chief Joseph and the United States Army. Under General O. O. Howard, the army surprised a Nez Perce village; the Nez Perce counter- ...

on July 11–12. Colonel Gibbon hastily assembled a force of about 200 artillery, cavalry, and infantry and proceeded up the Bitterroot River

The Bitterroot River is a northward flowing river running through the Bitterroot Valley, from the confluence of its West and East forks near Conner in southern Ravalli County to its confluence with the Clark Fork River near Missoula in Missoul ...

into the Big Hole Basin to stop them. On August 9, Gibbon attacked with his infantry and artillery at dawn. But the Nez Perce captured his howitzer

A howitzer () is a long- ranged weapon, falling between a cannon (also known as an artillery gun in the United States), which fires shells at flat trajectories, and a mortar, which fires at high angles of ascent and descent. Howitzers, like ot ...

and Nez Perce sharpshooters killed 30 of his men and officers. The Battle of the Big Hole

The Battle of the Big Hole was fought in Montana Territory, August 9–10, 1877, between the United States Army and the Nez Perce tribe of Native Americans during the Nez Perce War. Both sides suffered heavy casualties. The Nez Perce withd ...

continued until August 10, as the Nez Perce pinned Gibbon's men down in a coulee

Coulee, or coulée ( or ) is a term applied rather loosely to different landforms, all of which refer to a kind of valley or drainage zone. The word ''coulee'' comes from the Canadian French ''coulée'', from French ''couler'' 'to flow'.

The ...

. The band finally fled, 89 of their own (mostly women and children) dead. After a lengthy flight through Montana, the Nez Perce finally surrendered at the Battle of Bear Paw

The Battle of Bear Paw (also sometimes called Battle of the Bears Paw or Battle of the Bears Paw Mountains) was the final engagement of the Nez Perce War of 1877. Following a running fight from north central Idaho Territory over the previous f ...

near Chinook, Montana

Chinook is a city in and the county seat of Blaine County, Montana, United States. The population was 1,185 at the 2020 census. Points of interest are the Bear Paw Battlefield Museum located in the small town's center and the Bear Paw Battlefi ...

, on October 5, 1877. Montana saw its last skirmishes with Native Americans in 1878.

Later commanders

In the summer of 1878, the 7th Infantry was moved toSaint Paul, Minnesota

Saint Paul (abbreviated St. Paul) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital of the U.S. state of Minnesota and the county seat of Ramsey County, Minnesota, Ramsey County. Situated on high bluffs overlooking a bend in the Mississip ...

, and Fort Shaw became the headquarters of the 3rd U.S. Infantry Regiment under the command of Colonel John R. Brooke

John Rutter Brooke (July 21, 1838 – September 5, 1926) was one of the last surviving Union generals of the American Civil War when he died at the age of 88.

Early life

Brooke was born in Pottstown, Pennsylvania, and was educated in nearby Coll ...

. Brooke was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel on March 20, 1879, and assigned to the 13th Infantry Regiment (then in the Dakotas). But undisclosed personnel issues kept Brooke at Fort Shaw. He was joined by Colonel Luther Prentice Bradley. There were six companies in the 3rd Infantry. Company A was assigned to Fort Benton. Companies C, E, F, and G were assigned to Fort Shaw. Company K was assigned to Fort Logan (the former Camp Baker).

Life at Fort Shaw was increasingly peaceful. Company E of the 3rd Infantry was sent from Fort Shaw to Fort Ellis in the spring of 1879, and it was followed by Company C in the summer. (They stayed there until Fort Ellis closed in 1886, and then were transferred to Fort Custer, where they remained.) Companies A and K were reassigned to Fort Shaw in 1881. In the fall and summer of 1882 and 1883, at least two companies from Fort Shaw were kept in the field at all times, observing Native American movements and discouraging raids on white settlements south of the Piegan Blackfeet reservation. The peaceful life was not necessarily fun for the isolated soldiers, who often visited nearby communities to drink. In 1885, the first Independence Day

An independence day is an annual event commemorating the anniversary of a nation's independence or statehood, usually after ceasing to be a group or part of another nation or state, or more rarely after the end of a military occupation. Man ...

celebrations occurred in Great Falls. Soldiers from Fort Shaw became roaring drunk during the day, and fired several cannonballs down Central Avenue (the city's main street) around midnight.

In April 1888, Colonel Brooke was promoted to brigadier general, and the 3rd Infantry transferred to forts in the Dakotas and Minnesota. The 25th Infantry Regiment, under the command of Colonel George Lippitt Andrews

George Lippitt Andrews (April 22, 1828 – July 19, 1920) was an officer of the United States Army, who commanded the African-American 25th Infantry Regiment for 20 years.

Early life and education

Andrews was born in Providence, Rhode Isla ...

, took up station at Fort Shaw in May 1888 in its stead. By this time, Fort Shaw was no longer seen as a key fort in the Army's chain of military posts across Montana. Colonel Andrews, his headquarters company, and two companies of infantry resided at Fort Missoula

Fort Missoula was established by the United States Army in 1877 on land that is now part of the city of Missoula, Montana, Missoula, Montana, to protect settlers in Western Montana from possible threats from the Indigenous peoples of the Americas, ...

, more than to the west over the Rocky Mountains. Just two companies of the 25th Infantry (I and K) resided at Fort Shaw, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel James J. Van Horn. These two companies were "skeletonized" in September 1890, leaving Fort Shaw with only a minimal military presence.

The construction of Fort Assinniboine

Fort Assinniboine was a United States Army fort located in present-day north central Montana (historically within the military Department of Dakota). It was built in 1879 and operated by the Army through 1911. The 10th Cavalry Buffalo Soldiers, ...

(which cost $1 million to build) in 1879 led to the creation of a new center of U.S. military power in Montana far from the more settled central and southwestern parts of the state, and led to the eventual closure of Fort Shaw and Fort Ellis. Fort Shaw was abandoned by the U.S. Army on July 1, 1891.

Civilian use

Fort Shaw Indian school

By 1892, the Fort Shaw military reservation totaled . Ownership of Fort Shaw was transferred from theUnited States Department of War

The United States Department of War, also called the War Department (and occasionally War Office in the early years), was the United States Cabinet department originally responsible for the operation and maintenance of the United States Army, a ...

to the United States Department of the Interior

The United States Department of the Interior (DOI) is one of the executive departments of the U.S. federal government headquartered at the Main Interior Building, located at 1849 C Street NW in Washington, D.C. It is responsible for the mana ...

on April 30, 1892. The Interior Department turned over to the Fort Peck Indian school on June 6, 1903. Another were turned over to the school for agricultural purposes on July 6, 1905. On July 22, 1905, President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

issued an executive order

In the United States, an executive order is a directive by the president of the United States that manages operations of the federal government. The legal or constitutional basis for executive orders has multiple sources. Article Two of th ...

giving the Secretary of the Interior Secretary of the Interior may refer to:

* Secretary of the Interior (Mexico)

* Interior Secretary of Pakistan

* Secretary of the Interior and Local Government (Philippines)

* United States Secretary of the Interior

See also

*Interior ministry ...

the authority to dispose of all the land of the former Fort Shaw Military Reservation, holding in reserve those acres in use by the Indian school.

By the 1880s, the United States government undertook a major initiative to pacify Native American tribes through nonviolent means. A key element in this effort was the creation of boarding schools. These schools, sometimes on reservations but just as often not, were originally run by religious groups. By the 1890s, however, the schools had been largely secularized and were being run by government employees and government-employed teachers. The goal of Indian boarding schools was two-fold: First, to strip Native American children of their language and culture, teach them the English language

English is a West Germanic language of the Indo-European language family, with its earliest forms spoken by the inhabitants of early medieval England. It is named after the Angles, one of the ancient Germanic peoples that migrated to the is ...

, and instill in them the values and cultural ways of white Americans; and second, to teach them academic subjects, vocational trades, and other skills that were valued by white American business and society.

The Fort Shaw school came into existence after the government boarding school on the Fort Peck Indian Reservation

The Fort Peck Indian Reservation ( asb, húdam wįcášta, dak, Waxchį́ca oyáte) is located near Fort Peck, Montana, in the northeast part of the state. It is the home of several federally recognized bands of Assiniboine

The Assinibo ...

suffered severe fires in November 1891 and the fall of 1892. The school was modeled on Indian schools in Carlisle, Pennsylvania

Carlisle is a Borough (Pennsylvania), borough in and the county seat of Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, United States. Carlisle is located within the Cumberland Valley, a highly productive agricultural region. As of the 2020 United States census, ...

; Lawrence, Kansas

Lawrence is the county seat of Douglas County, Kansas, Douglas County, Kansas, United States, and the sixth-largest city in the state. It is in the northeastern sector of the state, astride Interstate 70, between the Kansas River, Kansas and Waka ...

; and Newkirk, Oklahoma

Newkirk is a city and county seat of Kay County, Oklahoma, United States. The population was 2,172 at the 2020 census.

History

Newkirk is on land known as the Cherokee Outlet (popularly called the "Cherokee Strip"), which belonged to the Chero ...

, and was named the Fort Shaw Government Industrial Indian Boarding School, The school officially opened on December 27, 1892, with Dr. William Winslow as the school's superintendent, first teacher, and physician. It had 52 students, but by the end of 1893 enrollment had climbed to 176. Administrators and faculty were housed in the old officers' quarters, which students boarded in the former soldiers' barracks. Students ranged in age from five to 18, and came from tribes in Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming. Half of each day was spent learning English and in academic study. The rest of the day was spent working in the school's garden, stables, and pastures raising the meat and vegetables which supplied the school with food; in making uniforms and shoes for the children to wear; and in maintaining and repairing the school's buildings and furniture. The vocational curriculum was gender-specific. Girls learned to cook "white" food the "white" way, sew, clean house, make dairy products (butter, cream, skim milk) from raw milk

Milk is a white liquid food produced by the mammary glands of mammals. It is the primary source of nutrition for young mammals (including breastfed human infants) before they are able to digestion, digest solid food. Immune factors and immune ...

, and engage in crochet

Crochet (; ) is a process of creating textiles by using a crochet hook to interlock loops of yarn, thread (yarn), thread, or strands of other materials. The name is derived from the French term ''crochet'', meaning 'hook'. Hooks can be made from ...

ing, lace

Lace is a delicate fabric made of yarn or thread in an open weblike pattern, made by machine or by hand. Generally, lace is divided into two main categories, needlelace and bobbin lace, although there are other types of lace, such as knitted o ...

-making, and other needlework. Boys were taught the essentials of farming and ranching, as well as skills such as blacksmithing, carpentry, construction, masonry, and woodworking. Sports were taught to both boys and girls. Girls played double ball, lacrosse

Lacrosse is a team sport played with a lacrosse stick and a lacrosse ball. It is the oldest organized sport in North America, with its origins with the indigenous people of North America as early as the 12th century. The game was extensively ...

, and shinny

Shinny (also shinney, pick-up hockey, pond hockey, or "outdoor puck") is an informal type of hockey played on ice. It is also used as another term for street hockey. There are no formal rules or specific positions, and often, there are no goalte ...

(informal ice hockey

Ice hockey (or simply hockey) is a team sport played on ice skates, usually on an ice skating rink with lines and markings specific to the sport. It belongs to a family of sports called hockey. In ice hockey, two opposing teams use ice hock ...

). Boys were taught baseball

Baseball is a bat-and-ball sport played between two teams of nine players each, taking turns batting and fielding. The game occurs over the course of several plays, with each play generally beginning when a player on the fielding tea ...

, football

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kicking a ball to score a goal. Unqualified, the word ''football'' normally means the form of football that is the most popular where the word is used. Sports commonly c ...

, and track

Track or Tracks may refer to:

Routes or imprints

* Ancient trackway, any track or trail whose origin is lost in antiquity

* Animal track, imprints left on surfaces that an animal walks across

* Desire path, a line worn by people taking the shorte ...

.

Students at Fort Shaw usually spent their first two years at the school learning English and "white" cultural norms. Children were grouped in grades according to their skill levels, which meant that both very young children and young adults could be found in the same class. Students advanced to the next grade based on achievement, and there was no social stigma for students who stayed for a two or more years in the same grade. Fort Shaw's curriculum ended at the eighth grade, but students in their late teens (indeed, some as old as 25 years of age) could be found studying there.

Dr. Winslow resigned his position on September 9, 1898, and Frederick C. Campbell became Fort Shaw School's superintendent. At that time, the school had 300 students from every tribe in Montana as well as the Bannock

Bannock may mean:

* Bannock (food), a kind of bread, cooked on a stone or griddle

* Bannock (Indigenous American), various types of bread, usually prepared by pan-frying

* Bannock people, a Native American people of what is now southeastern Oregon ...

, Colville, Kalispel

The Pend d'Oreille ( ), also known as the Kalispel (), are Indigenous peoples of the Northwest Plateau. Today many of them live in Montana and eastern Washington of the United States. The Kalispel peoples referred to their primary tribal range a ...

, Paiute

Paiute (; also Piute) refers to three non-contiguous groups of indigenous peoples of the Great Basin. Although their languages are related within the Numic group of Uto-Aztecan languages, these three groups do not form a single set. The term "Pai ...

, and Shoshone

The Shoshone or Shoshoni ( or ) are a Native American tribe with four large cultural/linguistic divisions:

* Eastern Shoshone: Wyoming

* Northern Shoshone: southern Idaho

* Western Shoshone: Nevada, northern Utah

* Goshute: western Utah, easter ...

tribes of neighboring Idaho, Washington, and Wyoming. Most students had a white father and Native American mother, and another many were there voluntarily a large number had been forcibly taken from their parents by government agents and forced to attend the "white" school against their wishes. Senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

Paris Gibson

Paris Gibson (July 1, 1830December 16, 1920) was an American entrepreneur and politician.

Gibson was born in Brownfield, Maine. An 1851 graduate of Bowdoin College, he served as a member of the Montana State Senate and as a Democratic member ...

visited the school in 1901, at which time it had 30 administrators and teachers and 316 students. A girls' basketball team was organized at Fort Shaw School in 1902. Campbell became the girls' basketball coach. The girls' team began interscholastic play in November 1902 (defeating Butte Parochial High School), and on January 15, 1903, played the very first basketball game (men's or women's) in nearby Great Falls, Montana

Great Falls is the third most populous city in the U.S. state of Montana and the county seat of Cascade County. The population was 60,442 according to the 2020 census. The city covers an area of and is the principal city of the Great Falls, M ...

. (Fort Shaw lost to Butte Parochial, 15-to-6.) In 1903, the team twice defeated the women's basketball team from Montana Agricultural College, once in Great Falls (36-to-9) and again in Bozeman (20-to-0). The Fort Shaw girls defeated nearly every high school and college girls' basketball team in the state, as well as several high school boys' teams. The team ended its first year as undisputed (if unofficial) state champion. It was unable to reproduce that record in the 1903–04 season, as the team could not secure appointments for games with any other high school in the state that year.

In 1904, school superintendent Fred Campbell agreed to send his girls' basketball team to the Louisiana Purchase Exposition

The Louisiana Purchase Exposition, informally known as the St. Louis World's Fair, was an World's fair, international exposition held in St. Louis, Missouri, United States, from April 30 to December 1, 1904. Local, state, and federal funds tota ...

(better known as the St. Louis World's Fair) in St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi River, Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the Greater St. Louis, ...

. To fund their trip, the team stopped at numerous points along the way to play exhibition games against other high school and college girls' teams. After each game, the girls donned traditional native ceremonial garb and charged a fee (50 cents) for a program of dance, music, and recitations. Part of the United States' pavilion at the world's fair

A world's fair, also known as a universal exhibition or an expo, is a large international exhibition designed to showcase the achievements of nations. These exhibitions vary in character and are held in different parts of the world at a specif ...

was a Model Indian School. The girls would live and take classes at the school, and twice a week would hold intra-squad exhibitions. The girls also agreed to take on all challengers. The girls departed from Fort Shaw on June 1, 1904. The 11 girls defeated every single team they played over the next five months, earning themselves the title "world champions".

The Fort Shaw Indian school closed in 1910 due to low attendance.

Ownership by the town of Fort Shaw

After its closure as an Indian school, Fort Shaw was turned over to the Fort Shaw Public School District, and the buildings were used as a public school. The nameFort Shaw

Fort Shaw (originally named Camp Reynolds) was a United States Army fort located on the Sun River 24 miles west of Great Falls, Montana, in the United States. It was founded on June 30, 1867, and abandoned by the Army in July 1891. It later serv ...

was revived when it became the name of a station and later a small town on the Vaughn-Augusta branch line of the Great Northern Railroad and some distance from the fort remnants. Today there are some buildings from the old days of the fort and one serves as a historical museum that's only open during the summer.

Today, most of the existing buildings and grounds of Fort Shaw, with the exception of the school and playground are under a long term lease by the Sun River Valley Historical Society.

Commanding officers

The commanding officers at Fort Shaw changed over time. Not all officers were present even when assigned to the fort, as they often traveled with their troops or moved among the various forts, camps, and settlements under their jurisdiction. 1867–1870 — 13th Infantry Regiment *General Phillipe Régis de Trobriand *Colonel I. V. D. Reeves *Lieutenant Colonel G. L. Andrews (post commandant) *Major William Clinton 1870–1878 — 7th Infantry Regiment *Colonel John Gibbon 1878–1888 — 3rd U.S. Infantry Regiment *Colonel John R. Brooke *Lieutenant Colonel George Gibsin 1888–1891 — 25th Infantry Regiment *Lieutenant Colonel James J. Van Horn *Lieutenant Colonel George Leonard Andrews (commanding from Fort Missoula)Fort Shaw historic site

In 1936, the state of Montana erected a historic marker at the site of Fort Shaw. The marker consists of aredwood

Sequoioideae, popularly known as redwoods, is a subfamily of coniferous trees within the family

Family (from la, familia) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affini ...

board on which is text describing Fort Shaw and some of its history. The sign hangs on short chains from a redwood crossbar which itself is mortar-joined and bolted to upright redwood posts. The posts are set in a stone and mortar based about high. The painted sign was replaced with one in which the text was routed

Routing is the process of selecting a path for traffic in a network or between or across multiple networks. Broadly, routing is performed in many types of networks, including circuit-switched networks, such as the public switched telephone netwo ...

and painted white in the 1940s. It is one of the original historic highway markers erected by the state, and is one in the best condition as of 2008.

The National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an agency of the United States federal government within the U.S. Department of the Interior that manages all national parks, most national monuments, and other natural, historical, and recreational propertie ...

considered adding Fort Shaw to its system after proposals by the Sons and Daughters of Montana Pioneers in 1936 and 1938. However, after conducting a study, officials determined the site was "not of national significance." Fort Shaw is part of the Fort Shaw Historic District and Cemetery, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places on January 11, 1985. A portion of the fort remains standing as of 2009.

References

;Notes ;CitationsBibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *{{cite book , last1=Sherris , first1=Arieh (Ari) , last2=Pete , first2=Tachini , last3=Thompson , first3=Lynn E. , last4=Haynes , first4=Erin Lynn , chapter=Task-Based Language Teaching Practices That Support Salish Language Revitalization , title=Keeping Languages Alive: Documentation, Pedagogy and Revitalization , editor-last1=Jones , editor-first1=Mari C. , editor-last2=Jones , editor-first2=Sarah Ogilvie , url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8DhEAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA157&dq=%22Fort+Shaw%22+closed+1910&hl=en&sa=X&ei=wAk-U77DM4ny2gXfmIDQAw&ved=0CDoQ6AEwATgU#v=onepage&q=%22Fort%20Shaw%22%20closed%201910&f=false , location=Cambridge, UK , publisher=Cambridge University Press , year=2013 , isbn=9781107029064External links

Fort Shaw Web site

National Register of Historic Places in Cascade County, Montana

Shaw

Shaw may refer to:

Places Australia

*Shaw, Queensland

Canada

*Shaw Street, a street in Toronto

England

*Shaw, Berkshire, a village

*Shaw, Greater Manchester, a location in the parish of Shaw and Crompton

*Shaw, Swindon, a List of United Kingdom ...

1867 establishments in Montana Territory

Buildings and structures completed in 1867

Schools in Cascade County, Montana

Educational institutions established in 1892

1892 establishments in Montana

Museums in Cascade County, Montana

Educational institutions disestablished in 1910