Foreign Policy Of The Theodore Roosevelt Administration on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The foreign policy of the Theodore Roosevelt administration covers American foreign policy from 1901 to 1909, with attention to the main diplomatic and military issues, as well as topics such as immigration restriction and trade policy. For the administration as a whole see

Roosevelt had been a major advocate of imperial expansion in the late 1890s. However by 1905 he had lost interest in the new acquisitions and focused his attention on building the Panama Canal and guaranteeing its security in the Caribbean region. Adam Burns says, "Roosevelt began the period as an ardent

imperialist and changed his views to reflect a change in US public opinion and strategic concerns....Roosevelt came to believe that retention of the hilippineislands would need to end sooner rather than later."

Roosevelt had been a major advocate of imperial expansion in the late 1890s. However by 1905 he had lost interest in the new acquisitions and focused his attention on building the Panama Canal and guaranteeing its security in the Caribbean region. Adam Burns says, "Roosevelt began the period as an ardent

imperialist and changed his views to reflect a change in US public opinion and strategic concerns....Roosevelt came to believe that retention of the hilippineislands would need to end sooner rather than later."

In December 1902, an Anglo-German naval blockade of

In December 1902, an Anglo-German naval blockade of  A crisis in the

A crisis in the

Roosevelt sought the creation of a canal through Central America which would link the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean. Most members of Congress preferred that the canal cross through

Roosevelt sought the creation of a canal through Central America which would link the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean. Most members of Congress preferred that the canal cross through

online

* Beale, Howard K. ''Theodore Roosevelt and the Rise of America to World Power'' (1956); a standard history of his foreign policy; focus on Britain, China, Japan and Germany

online

* Blake, Nelson Manfred. "Ambassadors at the court of Theodore Roosevelt." ''Mississippi Valley Historical Review'' 42.2 (1955): 179-206

online

* Brands, H.W. ''TR: The Last Romantic'' (Basic Books, 1997) full scholarly biography

online

* Bryne, Alex. ''The Monroe Doctrine and United States National Security in the Early Twentieth Century'' (Springer Nature, 2020). * Burns, Adam D. "Adapting to Empire: William H. Taft, Theodore Roosevelt, and the Philippines, 1900–08." ''Comparative American Studies: An International Journal'' 11.4 (2013): 418-433. * Burton, D. H. "Theodore Roosevelt and the Special Relationship with Britain" ''History Today'' (Aug 1973), 23#8 pp 527–535 online. * Collin, Richard H. ''Theodore Roosevelt's Caribbean: The Panama Canal, the Monroe Doctrine, and the Latin American Context'' (1990), a defense of TR's policies

online review

* . * Cullinane, Michael Patrick. "The ‘Gentlemen's’ Agreement–Exclusion by Class." ''Immigrants & Minorities'' 32.2 (2014): 139-161

online

* Cullinane, Michael Patrick. "Theodore Roosevelt in the eyes of the Allies." ''Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era'' 15.1 (2016): 80-101

online

focus on World War I * Dennett, Tyler. ''John Hay: from poetry to politics'' (1933), Pulitzer prize. * Dennett, Tyler. ''Roosevelt and the Russo-Japanese war: a critical study of American policy in Eastern Asia in 1902-5, based primarily upon the private papers of Theodore Roosevelt'' (1925

online

* Esthus, Raymond A. ''Theodore Roosevelt and the International Rivalries'' (1970) *

online

* Green, Michael J. ''By More Than Providence: Grand Strategy and American Power in the Asia Pacific Since 1783'' (2019), pp 78–113

excerpt

* Haglund, David G. "Roosevelt as “Friend of France”—But Which One?" ''Diplomatic history'' 31.5 (2007): 883-908

online

* .

excerpt

*

excerpt

* * Hewes, Jr. James E. ''From Root to McNamara: Army Organization and Administration, 1900-1963'' (1975) * Hill, Howard C. ''Roosevelt and the Caribbean'' (University of Chicago Press, 1927)

online review

* Hodge, Carl C. "A Whiff of Cordite: Theodore Roosevelt and the Transoceanic Naval Arms Race, 1897–1909." ''Diplomacy & Statecraft'' 19.4 (2008): 712-731. * Holmes, James R. ''Theodore Roosevelt and world order: Police power in international relations'' (2006)

online review

* Hunt, Michael H. "Americans in the China Market: Economic Opportunities and Economic Nationalism, 1890s-1931." ''Business History Review'' 51.3 (1977): 277-307. * Jones, Gregg. ''Honor in the Dust: Theodore Roosevelt, War in the Philippines, and the Rise and Fall of America's Imperial Dream'' (Penguin. 2012

excerpt

* Karsten, Peter. "The Nature of 'Influence': Roosevelt, Mahan and the Concept of Sea Power." ''American Quarterly'' 23#4 (1971): 585-600

online

* Kinzer, Stephen. ''The True Flag: Theodore Roosevelt, Mark Twain, and the Birth of American Empire'' (2017

excerpt

* Krabbendam, Hans, and John Thompson, eds. ''America's Transatlantic Turn: Theodore Roosevelt and the "Discovery" of Europe'' (2012

excerpt

* Lewis, Tom Tandy. "Franco-American diplomatic relations, 1898-1907" (PhD dissertation, U of Oklahoma, 1970

online

*

online

*

online

** Marks, Frederick. “Morality as a Drive Wheel in the Diplomacy of Theodore Roosevelt.” ''Diplomatic History'' 2#1 (1978), pp. 43–62, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24909943. * , popular biography. * Moore, Gregory. ''Defining and Defending the Open Door Policy: Theodore Roosevelt and China, 1901–1909'' (Lexington Books, 2015)

online review

* * Nester, William R. ''Theodore Roosevelt and the Art of American Power: An American for All Time'' (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019)

excerpt

* Neu, Charles E. "Theodore Roosevelt and American Involvement in the Far East, 1901-1909." ''Pacific Historical Review'' 35.4 (1966): 433-449

online

* Neu, Charles E. ''An Uncertain Friendship: Theodore Roosevelt and Japan, 1906–1909'' (1967

online

* O'Gara, Gordon Carpenter. ''Theodore Roosevelt and the Rise of the Modern Navy'' (Princeton UP, 1943)

online

focus on organization * . On TR's controversial reforms. * Patterson, David S. "Japanese‐American Relations: The 1906 California Crisis, the Gentlemen's Agreement, and the World Cruise." in Serge Ricard ed. ''A Companion to Theodore Roosevelt'' (2011) pp: 391-416. * . Pulitzer prize

online free

2nd edition 1956 is updated and shortened

1956 edition

* Ricard, Serge. "An Atlantic triangle in the 1900s: Theodore Roosevelt's ‘special relationships’ with France and Britain." ''Journal of Transatlantic Studies'' 8.3 (2010): 202-212. * . * . * . * . * Russell, Greg. "Theodore Roosevelt's Diplomacy and the Quest for Great Power Equilibrium in Asia," ''Presidential Studies Quarterly'' 2008 38(3): 433-455. * Taliaferro, John. ''All the Great Prizes: The Life of John Hay, from Lincoln to Roosevelt'' (2014) pp 344–542

excerpt

* Thompson, John M. ''Great Power Rising: Theodore Roosevelt and the Politics of US Foreign Policy'' (Oxford UP, 2019

excerpt

** Thompson, John M. "A 'Polygonal' Relationship: Theodore Roosevelt, The United States and Europe." ''Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era'' 15.1 (2016): 102-106. ** Thompson, John M. "Theodore Roosevelt and the Politics of the Roosevelt Corollary." ''Diplomacy & Statecraft'' 26.4 (2015): 571-590. ** Thompson, John M. "'Panic-Struck Senators, Businessmen and Everybody Else': Theodore Roosevelt, Public Opinion, and the Intervention in Panama." ''Theodore Roosevelt Association Journal'' *(Winter/Spring 2011), Vol. 32 Issue 1/2, pp 7–28. * Tilchin, William N. "For the Present and the Future: The Well-Conceived, Successful, and Farsighted Statecraft of President Theodore Roosevelt." ''Diplomacy & Statecraft'' 19.4 (2008): 658-670. * Tilchin, William N. ''Theodore Roosevelt and the British Empire: A Study in Presidential Statecraft'' (1997) * Turk, Richard W. ''The Ambiguous Relationship: Theodore Roosevelt and Alfred Thayer Mahan'' (1987)

online book

also se

online review

* Turk, Richard W. "The United States Navy and the 'Taking' of Panama, 1901-1903." ''Military Affairs'' (1974): 92-96

online

* Wimmel, Kenneth. ''Theodore Roosevelt and the Great White Fleet: American Seapower Comes of Age'' (Brassey's 1998).

online

* Cullinane, Michael Patrick. ''Theodore Roosevelt's Ghost: The History and Memory of an American Icon'' (LSU Press, 2017)

excerpt

* Gable, John. “The Man in the Arena of History: The Historiography of Theodore Roosevelt” in ''Theodore Roosevelt: Many-Sided American,'' ed, by. Natalie Naylor, Douglas Brinkley and John Gable (Hearts of the Lakes, 1992), 613–643. * May, Ernest R. and James C. Thomson, eds, ''American-East Asian Relations: A Survey'' (1972) pp 131–172, historiography. * Ricard, Serge, ed. ''A Companion to Theodore Roosevelt'' (2011

contents

chapters 5, 15=23, 27. Essays by scholars. * Tilchin, William. "The Rising Star of Theodore Roosevelt'S Diplomacy: Major Studies From Beale to the Present," ''Theodore Roosevelt Association Journal'' (July 1989) 15#3 pp 2–18. * Walker, Stephen G., and Mark Schafer. "Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson as cultural icons of US foreign policy." ''Political Psychology'' 28.6 (2007): 747-776.

Extensive essay on Theodore Roosevelt and shorter essays on each member of his cabinet and First Lady from the Miller Center of Public Affairs

{{Foreign policy of U.S. presidents Presidency of Theodore Roosevelt 1900s in the United States Progressive Era in the United States Roosevelt, Theodore History of the foreign relations of the United States Roosevelt, Theodore administration Roosevelt, Theodore War scare

Presidency of Theodore Roosevelt

The presidency of Theodore Roosevelt started on September 14, 1901, when Theodore Roosevelt became the 26th president of the United States upon the assassination of President William McKinley, and ended on March 4, 1909. Roosevelt had been th ...

. In foreign policy, he focused on Central America where he began construction of the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a condui ...

. He modernized the U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cl ...

and expanded the Navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It in ...

. He sent the Great White Fleet on a world tour to project American naval power. Roosevelt was determined to continue the expansion of U.S. influence begun under President William McKinley (1897–1901). Roosevelt presided over a rapprochement

In international relations, a rapprochement, which comes from the French word ''rapprocher'' ("to bring together"), is a re-establishment of cordial relations between two countries. This may be done due to a mutual enemy, as was the case with Germ ...

with the Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It i ...

. He promulgated the Roosevelt Corollary

In the history of United States foreign policy, the Roosevelt Corollary was an addition to the Monroe Doctrine articulated by President Theodore Roosevelt in his State of the Union address in 1904 after the Venezuelan crisis of 1902–1903. ...

, which held that the United States would intervene in the finances of unstable Caribbean and Central American countries in order to forestall direct European intervention. Partly as a result of the Roosevelt Corollary, the United States would engage in a series of interventions in Latin America, known as the Banana Wars

The Banana Wars were a series of conflicts that consisted of military occupation, police action, and intervention by the United States in Central America and the Caribbean between the end of the Spanish–American War in 1898 and the inceptio ...

. After Colombia rejected a treaty granting the U.S. a lease across the isthmus of Panama, Roosevelt supported the secession of Panama. He subsequently signed a treaty with Panama which established the Panama Canal Zone. The Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a condui ...

was completed in 1914, greatly reducing transport time between the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean. Roosevelt's well-publicized actions were widely applauded.

The Open Door Policy

The Open Door Policy () is the United States diplomatic policy established in the late 19th and early 20th century that called for a system of equal trade and investment and to guarantee the territorial integrity of Qing China. The policy wa ...

was the priority of Secretary of State John Hay towards China, as he sought to keep open trade and equal trade opportunities in China for all countries. In practice, Britain agreed but the Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of Japan, 1947 constitu ...

and the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

kept their zones closed. China had five times the population of the U.S., but outside the few treaty ports (controlled by Europeans), there was vast poverty. American schemes to build railways went nowhere; the one American product which the Chinese did buy was kerosene

Kerosene, paraffin, or lamp oil is a combustible hydrocarbon liquid which is derived from petroleum. It is widely used as a fuel in aviation as well as households. Its name derives from el, κηρός (''keros'') meaning "wax", and was regi ...

from Standard Oil for their lamps.

Roosevelt admired Japan but American public opinion grew increasingly hostile. Roosevelt made clear to Tokyo that Washington respected Japan's control of Korea. He reached the Gentlemen's Agreement of 1907

The was an informal agreement between the United States of America and the Empire of Japan whereby Japan would not allow further emigration to the United States and the United States would not impose restrictions on Japanese immigrants already ...

, effectively ending Japanese immigration in the hope of cooling bad feelings.

Roosevelt sought to mediate and arbitrate other disputes, and in 1906 he helped resolve the First Moroccan Crisis

The First Moroccan Crisis or the Tangier Crisis was an international crisis between March 1905 and May 1906 over the status of Morocco. Germany wanted to challenge France's growing control over Morocco, aggravating France and Great Britain. The ...

by attending the Algeciras Conference. His vigorous and successful efforts to broker the end of the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

, won him the 1906 Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiolog ...

.

Background

McKinley was assassinated in September 1901 and was succeeded by Vice President Theodore Roosevelt. He was the foremost of the five key men whose ideas and energies reshaped American foreign policy: John Hay (1838-1905);Henry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot Lodge (May 12, 1850 November 9, 1924) was an American Republican politician, historian, and statesman from Massachusetts. He served in the United States Senate from 1893 to 1924 and is best known for his positions on foreign policy. ...

(1850-1924); Alfred Thayer Mahan

Alfred Thayer Mahan (; September 27, 1840 – December 1, 1914) was a United States naval officer and historian, whom John Keegan called "the most important American strategist of the nineteenth century." His book '' The Influence of Sea Powe ...

(1840-1914); and Elihu Root (1845-1937).Beliefs

In the analysis byHenry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (; ; born Heinz Alfred Kissinger, May 27, 1923) is a German-born American politician, diplomat, and geopolitical consultant who served as United States Secretary of State and National Security Advisor under the presid ...

Theodore Roosevelt was the first president to develop the guideline that it was America's duty to make its enormous power and potential influence felt globally. The idea of being a passive "city on the hill" model that others could look up to, he rejected. Roosevelt, trained in biology, was a social darwinist

Social Darwinism refers to various theories and societal practices that purport to apply biological concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest to sociology, economics and politics, and which were largely defined by scholars in We ...

who believed in survival of the fittest. The international world in his view was a realm of violence and conflict. The United States had all the economic and geographical potential to be the fittest nation on the globe. The United States had a duty to act decisively. For example in terms of the Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine was a United States foreign policy position that opposed European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It held that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign powers was a potentially hostile act ...

, America had to prevent European incursions in the Western Hemisphere. But there was more, as he expressed in his famous Roosevelt Corollary

In the history of United States foreign policy, the Roosevelt Corollary was an addition to the Monroe Doctrine articulated by President Theodore Roosevelt in his State of the Union address in 1904 after the Venezuelan crisis of 1902–1903. ...

to the Monroe Doctrine: the U.S. had to be the policeman of the region because unruly, corrupt smaller nations had to be controlled, and if United States did not do it, European powers would in fact intervene and develop their own base of power in the hemisphere in contravention to the Monroe Doctrine.

Roosevelt was a realist and a conservative. He deplored many of the increasingly popular idealistic liberal themes, such as were promoted by William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the Democratic Party, running three times as the party's nominee for President ...

, the anti-imperialists, and Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

. Kissinger says he rejected the efficacy of international law. Roosevelt argued that if a country could not protect its own interests, the international community could not help very much. He ridiculed disarmament proposals that were increasingly common. He saw no likelihood of an international power capable of checking wrongdoing on a major scale. As for world government:I regard the Wilson–Bryan attitude of trusting to fantastic peace treaties, too impossible promises, to all kinds of scraps of paper without any backing in efficient force, as abhorrent. It is infinitely better for a nation and for the world to have the Frederick the Great and Bismarck tradition as regards foreign policy than to have the Bryan or Bryan–Wilson attitude as a permanent national attitude.... A milk-and-water righteousness unbacked by force is...as wicked as and even more mischievous than force divorced from righteousness.On the positive side, Roosevelt favored spheres of influence, whereby one great power would generally prevail, such as the United States in the Western Hemisphere or Great Britain in the Indian subcontinent. Japan fit that role and he approved. However he had deep distrust of both Germany and Russia.

Organization

Roosevelt was a highly energetic actor who personally made practically all the major foreign policy decisions. He had strong views on foreign policy, as he wanted the United States to assert itself as agreat power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power in ...

in international relations. Anxious to ensure a smooth transition, Roosevelt kept Secretary of State John Hay in office; Hay's health failed in 1903, although he remained in office until his death in 1905. Another holdover from McKinley's cabinet, Secretary of War Elihu Root, had been a Roosevelt confidante for years, and he continued to serve as President Roosevelt's close ally. Root returned to the private sector in 1904 and was replaced by William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

, who had previously served as the governor-general of the Philippines. After Hay's death in 1905, Roosevelt convinced Root to return to the Cabinet as secretary of state, and Root remained in office until the final days of Roosevelt's tenure. Taft increasingly became Roosevelt's trusted troubleshooter in foreign affairs, and his designated presidential successor in 1908 Roosevelt was very close to Senator Henry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot Lodge (May 12, 1850 November 9, 1924) was an American Republican politician, historian, and statesman from Massachusetts. He served in the United States Senate from 1893 to 1924 and is best known for his positions on foreign policy. ...

of Massachusetts, but otherwise largely kept his distance from congressional leaders, much to the annoyance of those senators who were accustomed to discussing diplomatic issues with President McKinley. Much of the trouble was blamed on Secretary of State John Hay, who had poor relations with the Senate in general and Lodge in particular. Hay and Lodge fought bitterly over the principle of commercial reciprocity with Newfoundland. Big Stick diplomacy

Roosevelt was adept at coining phrases to concisely summarize his policies. "Big stick" was his catch phrase for his hard pushing foreign policy: "Speak softly and carry a big stick; you will go far." Roosevelt described his style as "the exercise of intelligent forethought and of decisive action sufficiently far in advance of any likely crisis." Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany, who was bombastic and incautious in his public remarks, Roosevelt emphasized quiet discussion with all the interested parties to come to a consensus decision before he acted, The "big stick" generally referred to his highly visible naval buildup, and also to newspaper-based public opinion, when it became agitated on a foreign policy issue. As practiced by Roosevelt, big stick diplomacy had five components. First it was essential to possess serious military capabilities—the Big Stick—that forced the adversary to pay close attention. At the time that meant a world-class navy. The US Army remains quite small. The other qualities were to act justly toward other nations, never to bluff, to strike only if prepared to strike hard, and the willingness to allow the adversary to save face in defeat. Roosevelt generally followed the speak softly adage with one curious exception. He later claimed that he had personally resolved the Venezuela crisis of December 1902 by issuing an ultimatum to Germany that threatened war in a matter of days. In 1916 at a time Roosevelt was vigorously denouncing President Woodrow Wilson for being too weak to battle German aggression in World War I, Roosevelt claimed that he had threatened Germany with an immediate war back in 1902. Historians have repeatedly combed all the possible published and unpublished sources in the United States and Europe and have found no evidence whatever of any actual ultimatum being issued or discussed in Washington or Berlin. Roosevelt says he was threatening war against a major power but at the time he did not consult with his State Department, War Department, Navy Department, his generals, his admirals, nor leaders of Congress. Germany did pull back, in respond to the flareup of anti-German public opinion in American newspapers, and did pay attention to the build-up of the U.S. Navy, so it followed Great Britain in quickly accepting arbitration.Great power politics

Victory in theSpanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (cloc ...

had made the United States a power in both the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

and the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contin ...

, and Roosevelt was determined to continue the expansion of U.S. influence. Reflecting this view, Roosevelt stated in 1905, "We have become a great nation, forced by the face of its greatness into relations with the other nations of the earth, and we must behave as beseems a people with such responsibilities." Roosevelt believed that the United States had a duty to uphold a balance of power in international relations and seek to reduce tensions among the great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power in ...

s. He was also adamant in upholding the Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine was a United States foreign policy position that opposed European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It held that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign powers was a potentially hostile act ...

, the American policy of opposing European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. Roosevelt viewed the German Empire as the biggest potential threat to the United States, and he feared that the Germans would attempt to establish a base in the Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea ( es, Mar Caribe; french: Mer des Caraïbes; ht, Lanmè Karayib; jam, Kiaribiyan Sii; nl, Caraïbische Zee; pap, Laman Karibe) is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere. It is bounded by Mexico ...

. Given this fear, Roosevelt pursued closer relations with Britain, a rival of Germany, and responded skeptically to German Kaiser Wilhelm II

, house = Hohenzollern

, father = Frederick III, German Emperor

, mother = Victoria, Princess Royal

, religion = Lutheranism (Prussian United)

, signature = Wilhelm II, German Emperor Signature-.svg

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor ...

's efforts to curry favor with the United States. Roosevelt also attempted to expand U.S. influence in East Asia

East Asia is the eastern region of Asia, which is defined in both Geography, geographical and culture, ethno-cultural terms. The modern State (polity), states of East Asia include China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. ...

and the Pacific, where the Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of Japan, 1947 constitu ...

and the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

exercised considerable authority. Roosevelt admired Japan. Washington and Tokyo agreed to respect each other's interests, especially Japan in Korea and the U.S. in the Philippines.

One aspect of Roosevelt's strategy in East Asia was the Open Door Policy

The Open Door Policy () is the United States diplomatic policy established in the late 19th and early 20th century that called for a system of equal trade and investment and to guarantee the territorial integrity of Qing China. The policy wa ...

, which called for keeping China open to trade from all countries. It was mostly rhetoric with little practical impact.

A major turning point in establishing America's role in European affairs was the Moroccan crisis of 1905–1906. France and Britain had agreed that France would dominate Morocco, but Germany suddenly protested aggressively, with the disregard for quiet diplomacy characteristic of Kaiser Wilhelm. Berlin asked Roosevelt to serve as an intermediary, and he helped arrange a multinational conference at Algeciras, Morocco, where the crisis was resolved. Roosevelt advised Europeans in the future the United States would probably avoid any involvement in Europe, even as a mediator, so European foreign ministers stopped including the United States as a potential factor in the European balance of power.

Relations with Britain, France and Germany

Throughout his life Roosevelt had a deep interest in European affairs. However he greatly enjoyed personal diplomacy; European governments consequently appointed personal friends of Roosevelt to be ambassador in Washington. More than old friendship was involved, for when Germany sent Roosevelt's old friend, Hermann Speck von Sternburg, as ambassador, relations remained strained. The key working partnerships were with Britain, followed by France. Though Roosevelt had not previously been acquainted with Jean Jules Jusserand when he became France's ambassador in 1902, the two would become close friends and worked to greatly enhance the relationship between the two nations. Britain at this time was withdrawing from its isolationism, and forming closer relationships with Japan, France and the United States.Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

was a much more complex matter. It was a new nation – formed only in 1871, and already dominated much of the economic and political affairs of Europe. It was building a modern Navy to challenge the British Royal Navy. According to Howard K. Beale, the Kaiser respected Roosevelt and felt flattered when he was compared to the president in the newspapers. Roosevelt admired German military prowess and naval ambitions, but like many contemporary statesmen he realized that William was increasingly erratic and ran roughshod over the diplomatic niceties that smoothed out most tensions. Roosevelt saw Germany as the main adversary to American influence in Latin America, and indeed as the greatest single threat to world peace.

Aftermath of the Spanish–American War

Roosevelt had been a major advocate of imperial expansion in the late 1890s. However by 1905 he had lost interest in the new acquisitions and focused his attention on building the Panama Canal and guaranteeing its security in the Caribbean region. Adam Burns says, "Roosevelt began the period as an ardent

imperialist and changed his views to reflect a change in US public opinion and strategic concerns....Roosevelt came to believe that retention of the hilippineislands would need to end sooner rather than later."

Roosevelt had been a major advocate of imperial expansion in the late 1890s. However by 1905 he had lost interest in the new acquisitions and focused his attention on building the Panama Canal and guaranteeing its security in the Caribbean region. Adam Burns says, "Roosevelt began the period as an ardent

imperialist and changed his views to reflect a change in US public opinion and strategic concerns....Roosevelt came to believe that retention of the hilippineislands would need to end sooner rather than later."Philippines

Roosevelt inherited a country torn by debate over the territories acquired in theSpanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (cloc ...

. Roosevelt believed that Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

should be quickly granted independence and that Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and unincorporated ...

should remain a semi-autonomous possession under the terms of the Foraker Act

The Foraker Act, , officially known as the Organic Act of 1900, is a United States federal law that established civilian (albeit limited popular) government on the island of Puerto Rico, which had recently become a possession of the United State ...

. He at first wanted U.S. forces to remain in the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

to establish a stable, democratic government, even in the face of an insurrection

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

led by Emilio Aguinaldo. Roosevelt feared that a quick U.S. withdrawal would lead to instability in the Philippines or an intervention by a major power such as Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

or Japan. By 1902 he was in favor of early independence, although Taft argued that a longer tutelage was necessary.

The Filipino insurrection largely ended with the capture of Miguel Malvar

Miguel Malvar y Carpio (September 27, 1865 – October 13, 1911) was a Filipino general who served during the Philippine Revolution and, subsequently, during the Philippine–American War. He assumed command of the Philippine revolutionary forc ...

in 1902. In remote Southern areas, the Muslim Moros

In Greek mythology, Moros /ˈmɔːrɒs/ or Morus /ˈmɔːrəs/ (Ancient Greek: Μόρος means 'doom, fate') is the 'hateful' personified spirit of impending doom, who drives mortals to their deadly fate. It was also said that Moros gave peop ...

resisted American rule in an ongoing conflict known as the Moro Rebellion, but elsewhere the insurgents came to accept American rule. Roosevelt continued the McKinley policies of removing the Catholic friars (with compensation to the Pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

), upgrading the infrastructure, introducing public health programs, and launching a program of economic and social modernization. The enthusiasm shown in 1898-99 for colonies cooled off, and Roosevelt saw the islands as "our heel of Achilles." He told Taft in 1907, "I should be glad to see the islands made independent, with perhaps some kind of international guarantee for the preservation of order, or with some warning on our part that if they did not keep order we would have to interfere again." By then the president and his foreign policy advisers turned away from Asian issues to concentrate on Latin America, and Roosevelt redirected Philippine policy to prepare the islands to become the first Western colony in Asia to achieve self-government. Though most Filipino leaders favored independence, some minority groups, especially the Chinese who controlled much of local business, wanted to stay under American rule indefinitely.

The Philippines was a major target for the progressive reformers. A 1907 report to Secretary of War Taft provided a summary of what the civil administration had achieved in the Roosevelt years. It included, in addition to the rapid building of a public school system based on English teaching:

:steel and concrete wharves at the newly renovated Port of Manila

The Port of Manila ( fil, Pantalan ng Maynila) refers to the collective facilities and terminals that process maritime trade function in harbors in Metro Manila. Located in the Port Area and Tondo districts of Manila, Philippines facing the M ...

; dredging the River Pasig,; streamlining of the Insular Government; accurate, intelligible accounting; the construction of a telegraph and cable communications network; the establishment of a postal savings bank; large-scale road-and bridge-building; impartial and incorrupt policing; well-financed civil engineering; the conservation of old Spanish architecture; large public parks; a bidding process for the right to build railways; Corporation law; and a coastal and geological survey.

Cuba

While the Philippines remained under U.S. control until 1946, Cuba gained nominal independence in 1902. However thePlatt Amendment

On March 2, 1901, the Platt Amendment was passed as part of the 1901 Army Appropriations Bill.protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over most of its int ...

of the United States. Roosevelt won congressional approval for a reciprocity agreement with Cuba in December 1902, thereby lowering tariffs on trade between the two countries. In 1906, an insurrection erupted against Cuban President Tomás Estrada Palma

Tomás Estrada Palma (c. July 6, 1832 – November 4, 1908) was a Cuban politician, the president of the Cuban Republican in Arms during the Ten Years' War, and the first President of Cuba, between May 20, 1902, and September 28, 1906.

His coll ...

due to his electoral frauds. Both Estrada Palma and his liberal opponents called for an intervention by the U.S., but Roosevelt was reluctant to intervene. When Estrada Palma and his Cabinet resigned, Roosevelt sent Secretary of War Taft briefly as acting governor, then sent Charles Edward Magoon

Charles Edward Magoon (December 5, 1861 – January 14, 1920) was an American lawyer, judge, diplomat, and administrator who is best remembered as a governor of the Panama Canal Zone; he also served as Minister to Panama at the same time. Hi ...

as Provisional Governor for the Second Occupation of Cuba

The Provisional Government of Cuba lasted from September 1906 to February 1909. This period was also referred to as the Second Occupation of Cuba.

When the government of Cuban President Tomás Estrada Palma collapsed, U.S. President Theodore R ...

. U.S. forces restored peace to the island, and the occupation ceased shortly before the end of Roosevelt's presidency.

Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico had been something of an afterthought during the Spanish–American War, but it assumed importance due to its strategic position in the Caribbean Sea. The island provided an ideal naval base for defense of the Panama Canal, and it also served as an economic and political link to the rest of Latin America. Washington created a new political status for the island. The Foraker Act and subsequent Supreme Court cases established Puerto Rico as the firstunincorporated territory

Territories of the United States are sub-national administrative divisions overseen by the federal government of the United States. The various American territories differ from the U.S. states and tribal reservations as they are not sove ...

, meaning that the United States Constitution would not fully apply to Puerto Rico. Though the U.S. imposed tariffs on most Puerto Rican imports, it also invested in the island's infrastructure and education system; the goal was to Americanize the islanders. According to Matthew P. Johnson, the Puerto Rican Irrigation Service, funded by Washington, built large dams to irrigate canefields owned by North American sugar companies. Sugar yields doubled as a result and the dams generated cheap electricity. Nationalist sentiment remained strong on the island and Puerto Ricans continued to speak Spanish rather than English.

Hawaii

McKinley convinced Congress to annex the Republic of Hawaii in 1898, as desired by local leaders. There was concern in Washington that otherwise Japan would take over the islands. In the late 19th century, the rapid growth of sugar plantations led to the importation of large numbers of laborers, especially from Japan. About 124,000 Japanese worked on fifty or more plantations. China, the Philippines, Portugal and other countries sent an additional 300,000 workers. When Hawaii became part of the U.S. in 1898, the Japanese were the largest element of the population then. Although immigration from Japan largely ended by 1907, they have remained the largest racial element ever since. Pearl Harbor became the focus of American naval and military strength in the Pacific. The telegraph cable was laid from San Francisco to Manila via Hawaii and Midway Island in 1902 and 1903, bringing inexpensive communications and linking the U.S. to the main Pacific islands and to Asia.Army and Navy reform

The Army gets a General Staff

Roosevelt placed an emphasis on expanding and reforming the United States military. TheUnited States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land warfare, land military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight Uniformed services of the United States, U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army o ...

, with 39,000 men in 1890, was the smallest and least powerful army of any major power in the late 19th century. By contrast, France's army consisted of 542,000 soldiers. The Spanish–American War had been fought mostly by temporary volunteers and state national guard units, and it demonstrated that more effective control over the department and bureaus was necessary. Roosevelt gave strong support to the reforms proposed by Secretary of War Elihu Root, who wanted a uniformed chief of staff as general manager and a European-style general staff for planning. Overcoming opposition from General Nelson A. Miles

Nelson Appleton Miles (August 8, 1839 – May 15, 1925) was an American military general who served in the American Civil War, the American Indian Wars, and the Spanish–American War.

From 1895 to 1903, Miles served as the last Commanding Gen ...

, the Commanding General of the United States Army

The Commanding General of the United States Army was the title given to the service chief and highest-ranking officer of the United States Army (and its predecessor the Continental Army), prior to the establishment of the Chief of Staff of the ...

, Root succeeded in enlarging West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

and establishing the U.S. Army War College

The United States Army War College (USAWC) is a U.S. Army educational institution in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, on the 500-acre (2 km2) campus of the historic Carlisle Barracks. It provides graduate-level instruction to senior military officer ...

as well as the general staff. Root also changed the procedures for promotions, organized schools for the special branches of the service, devised the principle of rotating officers from staff to line, and increased the Army's connections to the National Guard

National Guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

Nat ...

.

Modernizing the Navy

Roosevelt made naval expansion a priority, and his tenure saw an increase in the number of ships, officers, and enlisted men in the Navy. According to Gordon O'Gara, Roosevelt had a major success in building the world's second most powerful fleet, behind Great Britain. New technology and managerial techniques brought in from the industrial world had a quick impact. Construction time of new ships was cut by 40%; new turbine engine technologies replaced bulky coal with oil; ships were given radios—called wireless—to communicate with each other and with headquarters; gunnery became much more accurate, and the speed of ships was greatly increased. But by building oil tankers the Navy could refuel anywhere around the world. By deepening the training and selecting highly qualified leaders such as William S. Sims, the Navy could now operate large complex fleets, far from home port. He demonstrated this success through the Great White Fleet of 1907-1909, the world's largest and most dramatic example of taking a powerful battle fleet around the globe. Roosevelt worked with CaptainAlfred Thayer Mahan

Alfred Thayer Mahan (; September 27, 1840 – December 1, 1914) was a United States naval officer and historian, whom John Keegan called "the most important American strategist of the nineteenth century." His book '' The Influence of Sea Powe ...

and paid very close attention to Mahan's argument in ''The Influence of Sea Power upon History

''The Influence of Sea Power upon History: 1660–1783'' is a history of naval warfare published in 1890 by the American naval officer and historian Alfred Thayer Mahan. It details the role of sea power during the seventeenth and eighteenth cent ...

, 1660–1783'' (1890) and his many magazine essays. Mahan said that only a nation with a powerful fleet could dominate the world's oceans, exert its diplomacy to the fullest, and defend its own borders. Though the new fleet did not match the worldwide strength of the British fleet, it became the dominant naval force in the Western Hemisphere.

Rapprochement with Great Britain

The Great Rapprochement

The Great Rapprochement is a historical term referring to the convergence of diplomatic, political, military, and economic objectives of the United States and the British Empire from 1895 to 1915, the two decades before American entry into World W ...

between Britain and the United States had begun with British support of the United States during the Spanish–American War, and it continued as Britain withdrew its fleet from the Caribbean in favor of focusing on the rising German naval threat. Roosevelt sought a continuation of close relations with Britain in order to ensure peaceful, shared hegemony over the Western hemisphere. With the British acceptance of the Monroe Doctrine and American acceptance of the British control of Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

, only two potential major issues remained between the U.S. and Britain: the Alaska boundary dispute

The Alaska boundary dispute was a territorial dispute between the United States and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, which then controlled Canada's foreign relations. It was resolved by arbitration in 1903. The dispute had existed ...

and construction of a canal across Central America

Central America ( es, América Central or ) is a subregion of the Americas. Its boundaries are defined as bordering the United States to the north, Colombia to the south, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. ...

. Under McKinley, Secretary of State Hay had negotiated the Hay–Pauncefote Treaty

The Hay–Pauncefote Treaty is a treaty signed by the United States and Great Britain on 18 November 1901, as a legal preliminary to the U.S. building of the Panama Canal. It nullified the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty of 1850 and gave the United States ...

, in which the British consented to U.S. construction of the canal. Roosevelt won Senate ratification of the treaty in December 1901.Morris (2001) pp 25–26

Alaska boundary dispute with Canada

The boundary between Alaska and Canada had become an issue in the late 1890s due to the Klondike Gold Rush, as prospectors discovered in the CanadianYukon

Yukon (; ; formerly called Yukon Territory and also referred to as the Yukon) is the smallest and westernmost of Canada's three territories. It also is the second-least populated province or territory in Canada, with a population of 43,964 as ...

and most new arrivals took the short cut through Alaska. A treaty on the border had been reached by Britain and Russia in the 1825 Treaty of Saint Petersburg, and the United States had assumed Russian claims on the region through the 1867 Alaska Purchase

The Alaska Purchase (russian: Продажа Аляски, Prodazha Alyaski, Sale of Alaska) was the United States' acquisition of Alaska from the Russian Empire. Alaska was formally transferred to the United States on October 18, 1867, through a ...

. The United States argued that the treaty had given Alaska sovereignty over disputed territories which included the gold rush boom towns of Dyea

Dyea ( ) is a former town in the U.S. state of Alaska. A few people live on individual small homesteads in the valley; however, it is largely abandoned. It is located at the convergence of the Taiya River and Taiya Inlet on the south side of th ...

and Skagway

The Municipality and Borough of Skagway is a first-class borough in Alaska on the Alaska Panhandle. As of the 2020 census, the population was 1,240, up from 968 in 2010. The population doubles in the summer tourist season in order to deal with ...

. The Venezuela Crisis briefly threatened to disrupt peaceful negotiations over the border, but conciliatory actions by the British during the crisis helped defuse any possibility of broader hostilities. In January 1903, the U.S. and Britain reached the Hay–Herbert Treaty, which would empower a six-member tribunal, composed of American, British, and Canadian delegates, to set the border between Alaska and Canada. With the help of Senator Henry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot Lodge (May 12, 1850 November 9, 1924) was an American Republican politician, historian, and statesman from Massachusetts. He served in the United States Senate from 1893 to 1924 and is best known for his positions on foreign policy. ...

, Roosevelt won the Senate's consent to the Hay–Herbert Treaty in February 1903. The tribunal consisted of three American delegates, two Canadian delegates, and Lord Alverstone

Richard Everard Webster, 1st Viscount Alverstone, (22 December 1842 – 15 December 1915) was a British barrister, politician and judge who served in many high political and judicial offices.

Background and education

Webster was the second son ...

, the lone delegate from Britain itself. Alverstone joined with the three American delegates in accepting most American claims, and the tribunal announced its decision in October 1903. The outcome of the tribunal strengthened relations between the United States and Britain, though many Canadians were outraged by the tribunal's decision.

Venezuela Crisis and Roosevelt Corollary

In December 1902, an Anglo-German naval blockade of

In December 1902, an Anglo-German naval blockade of Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

began an incident known as the Venezuelan Crisis. The blockade originated due to money owed by Venezuela that it refused to repay to European creditors. Both powers assured the U.S. that they were not interested in conquering Venezuela, and Roosevelt sympathized with the European creditors, but he became suspicious that Germany would demand territorial indemnification from Venezuela. Roosevelt and Hay feared that even an allegedly temporary occupation could lead to a permanent German military presence in the Western Hemisphere and that was a violation of the Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine was a United States foreign policy position that opposed European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It held that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign powers was a potentially hostile act ...

. As the blockade began, Roosevelt mobilized the U.S. fleet under the command of Admiral George Dewey

George Dewey (December 26, 1837January 16, 1917) was Admiral of the Navy, the only person in United States history to have attained that rank. He is best known for his victory at the Battle of Manila Bay during the Spanish–American War, with ...

. Germany, fearing the wrath of American public opinion, agreed to arbitration and Venezuela reached a settlement with Germany and Britain in February 1903.

Though Roosevelt would not tolerate European territorial ambitions in Latin America, he also believed that Latin American countries should pay the debts they owed to European credits. In late 1904, Roosevelt announced his Roosevelt Corollary

In the history of United States foreign policy, the Roosevelt Corollary was an addition to the Monroe Doctrine articulated by President Theodore Roosevelt in his State of the Union address in 1904 after the Venezuelan crisis of 1902–1903. ...

to the Monroe Doctrine. It stated that the U.S. would intervene in the finances of unstable Caribbean and Central American countries if they defaulted on their debts to European creditors. In effect, the U.S. would guarantee their debts, making it unnecessary for European powers to intervene. Roosevelt said the U.S. would be a "policeman." Europe went along and relied on the American policeman to collect its debts in Latin America.

A crisis in the

A crisis in the Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic ( ; es, República Dominicana, ) is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean region. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares with ...

became the first test case for the Roosevelt Corollary. Deeply in debt, the nation struggled to repay its European creditors. Fearing another intervention by Germany and Britain, Roosevelt reached an agreement with Dominican President Carlos Felipe Morales to take temporary control of the Dominican economy. Washington took control of the Dominican customs house, brought in economists such as Jacob Hollander

Jacob Harry Hollander (1871–1940) was an American economist.

Biography

Hollander was born in Baltimore, Maryland. He graduated from Johns Hopkins University with a BA in 1891, and a PhD in 1894. He became associate professor of finance there. ...

to restructure the economy, and ensured a steady flow of revenue to the Dominican Republic's foreign creditors. The intervention stabilized the political and economic situation in the Dominican Republic.

Panama Canal

Roosevelt sought the creation of a canal through Central America which would link the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean. Most members of Congress preferred that the canal cross through

Roosevelt sought the creation of a canal through Central America which would link the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean. Most members of Congress preferred that the canal cross through Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the countr ...

, which was eager to reach an agreement, but Roosevelt preferred the isthmus of Panama, under the loose control of Colombia. Colombia had been engulfed in a civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

since 1898, and a previous attempt to build a canal across Panama had failed under the leadership of Ferdinand de Lesseps

Ferdinand Marie, Comte de Lesseps (; 19 November 1805 – 7 December 1894) was a French diplomat and later developer of the Suez Canal, which in 1869 joined the Mediterranean and Red Seas, substantially reducing sailing distances and times ...

. A presidential commission appointed by McKinley had recommended the construction of the canal across Nicaragua, but it noted that a canal across Panama could prove less expensive and might be completed more quickly. Roosevelt and most of his advisers favored the Panama Canal, as they believed that war with a European power, possibly Germany, could soon break out over the Monroe Doctrine and the U.S. fleet would remain divided between the two oceans until the canal was completed.Morris (2001) pp. 201–202 After a long debate, Congress passed the Spooner Act

The First Spooner Act of 1902 (also referred to as the Panama Canal Act, 32 Stat. 481) was written by a United States senator from Wisconsin, John Coit Spooner, enacted on June 28, 1902, and signed by President Roosevelt the following day. It aut ...

of 1902, which granted Roosevelt $170 million to build the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a condui ...

. Following the passage of the Spooner Act, the Roosevelt administration began negotiations with the Colombian government regarding the construction of a canal through Panama.

The U.S. and Colombia signed the Hay–Herrán Treaty

The Hay–Herrán Treaty was a treaty signed on January 22, 1903, between United States Secretary of State John M. Hay of the United States and Tomás Herrán of Colombia. Had it been ratified, it would have allowed the United States a renewab ...

in January 1903, granting the U.S. a lease across the isthmus of Panama. The Colombian Senate refused to ratify the treaty, and attached amendments calling for more money from the U.S. and greater Colombian control over the canal zone. Panamanian rebel leaders, long eager to break off from Colombia, appealed to the United States for military aid. Roosevelt saw the leader of Colombia, José Manuel Marroquín

Jose Manuel Cayetano Marroquín Ricaurte (August 6, 1827 – September 19, 1908) was a Colombian political figure and the 27th President of Colombia.

Biographic data

José Manuel Marroquín was born in Bogotá, on August 6, 1827. He died i ...

, as a corrupt and irresponsible autocrat, and he believed that the Colombians had acted in bad faith by reaching and then rejecting the treaty. After an insurrection broke out in Panama, Roosevelt dispatched the USS Nashville to prevent the Colombian government from landing soldiers in Panama, and Colombia was unable to re-establish control over the province. Shortly after Panama declared its independence in November 1903, the U.S. recognized Panama as an independent nation and began negotiations regarding construction of the canal. According to Roosevelt biographer Edmund Morris, most other Latin American nations welcomed the prospect of the new canal in hopes of increased economic activity, but anti-imperialists

Anti-imperialism in political science and international relations is a term used in a variety of contexts, usually by nationalist movements who want to secede from a larger polity (usually in the form of an empire, but also in a multi-ethnic so ...

in the U.S. raged against Roosevelt's aid to the Panamanian separatists.

Secretary of State Hay and French diplomat Philippe-Jean Bunau-Varilla

Philippe-Jean Bunau-Varilla () (26 July 1859 – 18 May 1940) was a French engineer and soldier. With the assistance of American lobbyist and lawyer William Nelson Cromwell, Bunau-Varilla greatly influenced Washington's decision concerning t ...

, who represented the Panamanian government, quickly negotiated the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty

The Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty ( es, Tratado Hay-Bunau Varilla) was a treaty signed on November 18, 1903, by the United States and Panama, which established the Panama Canal Zone and the subsequent construction of the Panama Canal. It was named ...

. Signed on November 18, 1903, it established the Panama Canal Zone—over which the United States would exercise sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

—and insured the construction of an Atlantic to Pacific ship canal across the Isthmus of Panama. Panama sold the Canal Zone (consisting of the Panama Canal and an area generally extending on each side of the centerline) to the United States for $10 million and a steadily increasing yearly sum. In February 1904, Roosevelt won Senate ratification of the treaty in a 66-to-14 vote. The Isthmian Canal Commission

The Isthmian Canal Commission (often known as the ICC) was an American administration commission set up to oversee the construction of the Panama Canal in the early years of American involvement. Established on February 26, 1904, it was given cont ...

, supervised by Secretary of War Taft, was established to govern the zone and oversee the construction of the canal. Roosevelt appointed George Whitefield Davis as the first governor of the Panama Canal Zone and John Findley Wallace

John Findley Wallace (September 10, 1852 – July 3, 1921) was an American engineer and administrator, best known for serving as the Chief Engineer of the Panama Canal between 1904 and 1905. He had previously gained experience in railroad ...

as the Chief Engineer

A chief engineer, commonly referred to as "ChEng" or "Chief", is the most senior engine officer of an engine department on a ship, typically a merchant ship, and holds overall leadership and the responsibility of that department..Chief engineer ...

of the canal project. When Wallace resigned in 1905, Roosevelt appointed John Frank Stevens

John Frank Stevens (April 25, 1853 – June 2, 1943) was an American civil engineer who built the Great Northern Railway in the United States and was chief engineer on the Panama Canal between 1905 and 1907.

Biography

Stevens was born in ...

, who built a railroad in the canal zone and initiated the construction of a lock

Lock(s) may refer to:

Common meanings

*Lock and key, a mechanical device used to secure items of importance

*Lock (water navigation), a device for boats to transit between different levels of water, as in a canal

Arts and entertainment

* ''Lock ...

canal. Stevens was replaced in 1907 by George Washington Goethals

George Washington Goethals ( June 29, 1858 – January 21, 1928) was a United States Army General and civil engineer, best known for his administration and supervision of the construction and the opening of the Panama Canal. He was the State E ...

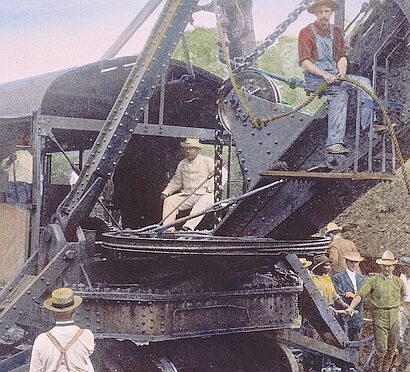

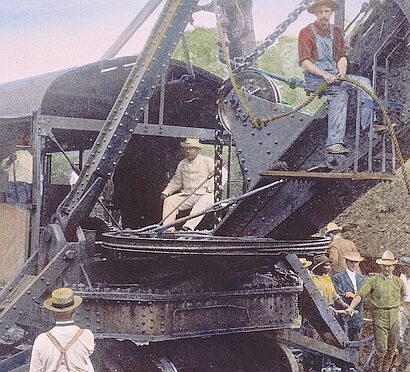

, who saw construction through to its completion. Roosevelt traveled to Panama in November 1906 to inspect progress on the canal, becoming the first sitting president to travel outside of the United States.

Open Door in China?

Roosevelt kept McKinley's Secretary of State John Hay until his death in 1905. Hay took charge of China policy. His ''Open Door Note'', sent in September, 1899, to the major European powers and Japan, proposed to keep China open to trade with all countries on an equal basis. It would keep any power from totally controlling China. It did not end the system of "treaty ports

Treaty ports (; ja, 条約港) were the port cities in China and Japan that were opened to foreign trade mainly by the unequal treaties forced upon them by Western powers, as well as cities in Korea opened up similarly by the Japanese Empire. ...

", especially Shanghai, which remained under the control of Western powers and where they transacted their export and import business. The Open Door policy was rooted in the desire of the government in Washington to pressure big business to invest in and trade with the supposedly huge Chinese markets. The policy won nominal support of all the rivals, and it also tapped the deep-seated sympathies of those who opposed imperialism by its policy pledging to protect China's sovereignty and territorial integrity from partition. It had almost no impact in actual practice. It had no legal standing or enforcement mechanism, and it did not lead to significant new American business activity. For example, multiple plans to build railways all failed.

Mediator for Russo-Japanese War

Russia had occupied the Chinese region ofManchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer M ...

in the aftermath of the 1900 Boxer Rebellion, and the United States, Japan, and Britain all sought the end of its military presence in the region. Russia agreed to withdraw its forces in 1902, but it reneged on this promise and sought to expand its influence in Manchuria to the detriment of the other powers. Roosevelt was unwilling to consider using the military to intervene in the far-flung region, but Japan prepared for war against Russia in order to remove it from Manchuria. When the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

broke out in February 1904, Roosevelt sympathized with the Japanese but sought to act as a mediator in the conflict. He hoped to uphold the Open Door policy in China and prevent either country from emerging as the dominant power in East Asia. Throughout 1904, both Japan and Russia expected to win the war, but the Japanese gained a decisive advantage after capturing the Russian naval base at Port Arthur in January 1905. In mid-1905, Roosevelt persuaded the parties to meet in a peace conference in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, starting on August 5. His persistent and effective mediation led to the signing of the Treaty of Portsmouth

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal pers ...

on September 5, ending the war. For his efforts, Roosevelt was awarded the 1906 Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiolog ...

. The Treaty of Portsmouth resulted in the removal of Russian troops from Manchuria, and it gave Japan control of Korea and the southern half of Sakhalin Island.

Pogroms in Russia

Repeated large-scale murderous attacks on Jews -- called apogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russia ...

-- in the late 19th and early 20th century increasingly angered American opinion. The well-established German Jews in the United States, although they were not directly affected by the Russian pograms, were well organized and convinced Washington to support the cause of Jews in Russia. Led by Oscar Straus, Jacob Schiff

Jacob (; ; ar, يَعْقُوب, Yaʿqūb; gr, Ἰακώβ, Iakṓb), later given the name Israel, is regarded as a patriarch of the Israelites and is an important figure in Abrahamic religions, such as Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Ja ...

, Mayer Sulzberger

Mayer Sulzberger (June 22, 1843 – April 20, 1923) was an American judge and Jewish communal leader.

Biography

Mayer Sulzberger was born at Heidelsheim, Bruchsal, Baden on June 22, 1843. He went to Philadelphia with his parents in 1848, and wa ...

, and Rabbi Stephen Samuel Wise

Stephen Samuel Wise (March 17, 1874 – April 19, 1949) was an early 20th-century American Reform rabbi and Zionist leader in the Progressive Era. Born in Budapest, he was an infant when his family immigrated to New York. He followed his fath ...

, they organize protest meetings, issued publicity, and met with Roosevelt and Hay. Stuart E. Knee reports that in April, 1903, Roosevelt received 363 addresses, 107 letters and 24 petitions signed by thousands of Christians leading public and church leaders--they all called on the Tsar to stop the persecution of Jews. Public rallies were held in scores of cities, topped off at Carnegie Hall in New York in May. The Tsar retreated a bit and fired one local official after the Kishinev pogrom

The Kishinev pogrom or Kishinev massacre was an anti-Jewish riot that took place in Kishinev (modern Chișinău, Moldova), then the capital of the Bessarabia Governorate in the Russian Empire, on . A second pogrom erupted in the city in Octob ...

, which Roosevelt explicitly denounced. But Roosevelt was mediating the war between Russia and Japan and could not publicly take sides. Therefore Secretary Hay took the initiative in Washington.

Finally Roosevelt forwarded a petition to the Tsar, who rejected it claiming the Jews were at fault. Roosevelt won Jewish support in his 1904 landslide reelection. The programs continued, as hundreds of thousands of Jews fled Russia, most heading for London or New York. With American public opinion turning against Russia, Congress officially denounced its policies in 1906. Roosevelt kept a low profile as did his new Secretary of State Elihu Root. However in late 1906 Roosevelt did appoint the first Jew to the cabinet, Oscar Straus becoming Secretary of Commerce and Labor.

Troubled relations with Japan

The American annexation of Hawaii in 1898 was stimulated in part by fear that otherwise Japan would dominate the Hawaiian Republic. By contrast, Germany was the alternative to the American takeover of the Philippines in 1898-1900, and Japan supported the American position. These events were part of the American goal of transitioning into a naval world power, but it needed to find a way to avoid a military confrontation in the Pacific with Japan. One of Theodore Roosevelt's high priorities during his presidency and even afterwards, was the maintenance of friendly relations with Japan. The most serious tensions – including widespread speculation among experts of war between the United States and Japan – came in 1907. The main cause was intense Japanese resentment against the mistreatment of Japanese in California as shown in thePacific Coast race riots of 1907

The Pacific Coast race riots were a series of riots that took place within the United States and Canada. The riots, which resulted in violence, were the result of anti-Asian tension caused by white opposition to the increasing Asian population duri ...

. Repeatedly in 1907, Roosevelt received warnings from authoritative sources at home and abroad that war with Japan was imminent. The British ambassador to Japan reported to his foreign minister in London that, "the Japanese government are fully impressed with the seriousness of the immigration question.A. Whitney Griswold, ''The Far Eastern policy of the United States'' (1938) p. 128. Roosevelt listened closely to the warnings but believed that Japan did not in fact have good reason to attack; nevertheless the risk was there. He told Secretary of State Elihu Root:the only thing that will prevent war is the Japanese feeling that we shall not be beaten, and this feeling we can only excite by keeping and making our navy efficient in the highest degree. It was evidently high time that we should get our whole battle fleet on a practice voyage to the Pacific."Pulitzer prize-winning biographer

Henry F. Pringle

Henry Fowles Pringle (1897–1958) was an American historian and writer most famous for his witty but scholarly biography of Theodore Roosevelt which won the Pulitzer prize in 1932, as well as a scholarly biography of William Howard Taft. His w ...

states that sending Great White Fleet so dramatically to Japan in 1908 was, "the direct result of the Japanese trouble." Furthermore Roosevelt made sure there was a strategy to defend the Philippines. In June 1907 he met with his military and naval leaders to decide on a series of operations to be carried in the Philippines which included shipments of coal, military rations, and the movement of guns and munitions. In Tokyo the British ambassador watched the Japanese reception to the Great White Fleet, and reported to London:The visit of the American fleet has been an unqualified success and has produced a marked and favorable impression on both officers and men of the fleet – in fact it is have the effect our allies wanted it to and has put an end to all this nonsensical war talk."Roosevelt quickly solidified friendly relations with the Root–Takahira Agreement whereby the United States and Japan explicitly recognized each other's major claims. Jingoistic American newspapers continued to attack Japan. The October 23, 1907 ''Puck'' magazine cover shows a Roosevelt in a Japanese uniform defending Tokyo from attack by two Democratic newspapers, the ''

Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

'' and the ''New York World

The ''New York World'' was a newspaper published in New York City from 1860 until 1931. The paper played a major role in the history of American newspapers. It was a leading national voice of the Democratic Party. From 1883 to 1911 under pub ...

''. The papers had predicted a future war with Japan and had criticized William Howard Taft, who had just been in Tokyo where Roosevelt sent him to promote improved relations.

Roosevelt saw Japan as the rising power in Asia, in terms of military strength and economic modernization. He viewed Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

as a backward nation that needed the guidance of Japan to modernize; he approved Japan's takeover of Korea. With the withdrawal of the American legation from Seoul and the refusal of the Secretary of State to receive a Korean protest mission, Washington signaled acceptance of Japan's takeover of Korea. In mid-1905, Taft and Japanese Prime Minister Katsura Tarō

Prince was a Japanese politician and general of the Imperial Japanese Army who served as the Prime Minister of Japan from 1901 to 1906, from 1908 to 1911, and from 1912 to 1913.

Katsura was a distinguished general of the First Sino-Japanese W ...

jointly produced the Taft–Katsura agreement

The , also known as the Taft-Katsura Memorandum, was a 1905 discussion between senior leaders of Japan and the United States regarding the positions of the two nations in greater East Asian affairs, especially regarding the status of Korea and the ...