Florence MacCarthy (politician) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Florence MacCarthy ( ga, Fínghin mac Donncha Mac Carthaig) (1560–1640), was an Irish clan chief and member of the

Mac Carthaig was born in 1560 at Kilbrittain Castle near

Mac Carthaig was born in 1560 at Kilbrittain Castle near

Gaelic nobility of Ireland

This article concerns the Gaelic nobility of Ireland from ancient to modern times. It only partly overlaps with Chiefs of the Name because it excludes Scotland and other discussion. It is one of three groups of Irish nobility, the others being ...

( ga, flaith) of the late 16th-century

The 16th century begins with the Julian year 1501 ( MDI) and ends with either the Julian or the Gregorian year 1600 ( MDC) (depending on the reckoning used; the Gregorian calendar introduced a lapse of 10 days in October 1582).

The 16th centu ...

and the last credible claimant to the Mac Carthaig Mór title before its suppression by English authority. Mac Carthaig's involvement in the Nine Years' War

The Nine Years' War (1688–1697), often called the War of the Grand Alliance or the War of the League of Augsburg, was a conflict between France and a European coalition which mainly included the Holy Roman Empire (led by the Habsburg monarch ...

(1595–1603) led to his arrest by the Crown, and he spent the last 40 years of his life in custody in London. His clan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, clans may claim descent from founding member or apical ancestor. Clans, in indigenous societies, tend to be endogamous, meaning ...

's lands were divided among his relatives and Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the establis ...

colonialist

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose their relig ...

s.

Early life

Mac Carthaig was born in 1560 at Kilbrittain Castle near

Mac Carthaig was born in 1560 at Kilbrittain Castle near Kinsale

Kinsale ( ; ) is a historic port and fishing town in County Cork, Ireland. Located approximately south of Cork City on the southeast coast near the Old Head of Kinsale, it sits at the mouth of the River Bandon, and has a population of 5,281 (a ...

in the province of Munster

Munster ( gle, an Mhumhain or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the south of Ireland. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" ( ga, rí ruirech). Following the ...

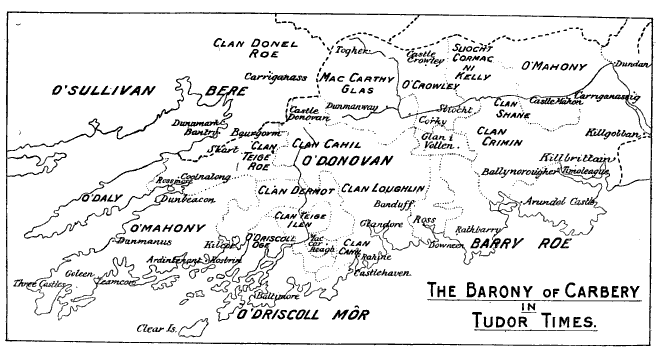

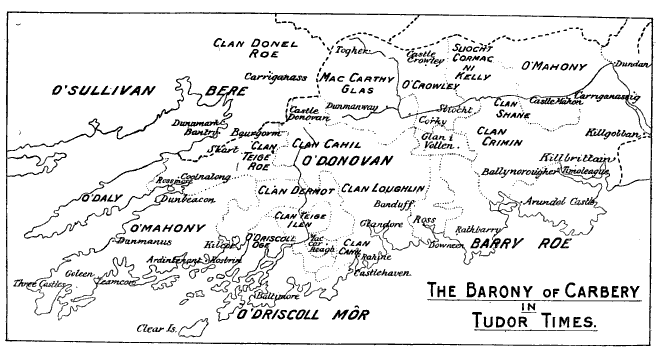

in Ireland, into the MacCarthy Reagh dynasty, rulers of Carbery Carbery or Carbury may refer to:

;People:

* Brian Carbury (1918–1961), New Zealand fighter ace

* Douglas Carbery (1894–1959), British soldier and airman

* Ethna Carbery (1864–1902), Irish writer

* James Joseph Carbery (1823–1887), Irish Dom ...

, the son of Donogh MacCarthy Reagh, 15th Prince of Carbery. His grandfather was Donal MacCarthy Reagh, 12th Prince of Carbery.

The significance of Mac Carthaig's career lies in his command of territories in west Munster, at a time when the Tudor conquest of Ireland was underway. Southwest Munster was the area most open to Spanish intervention, which had been mooted from the late 1570s to aid Catholic rebellions in Ireland. The overlord of much of this area, but excluding Carbery, was the MacCarthy Mór

MacCarthy ( ga, Mac Cárthaigh), also spelled Macarthy, McCarthy or McCarty, is an Irish Irish clans, clan originating from Kingdom of Munster, Munster, an area they ruled during the Middle Ages. It was divided into several great branches; the M ...

of Desmond, whose lands were located in modern west Cork

Cork or CORK may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Cork (plug), a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

***Wine cork

Places Ireland

* Cork (city)

** Metropolitan Cork, also known as G ...

and Kerry

Kerry or Kerri may refer to:

* Kerry (name), a given name and surname of Gaelic origin (including a list of people with the name)

Places

* Kerry, Queensland, Australia

* County Kerry, Ireland

** Kerry Airport, an international airport in County ...

. There were, in addition, three more princely branches of the MacCarthy dynasty

MacCarthy ( ga, Mac Cárthaigh), also spelled Macarthy, McCarthy or McCarty, is an Irish clan originating from Munster, an area they ruled during the Middle Ages. It was divided into several great branches; the MacCarthy Reagh, MacCarthy of Musk ...

, the MacCarthys of Muskerry

The MacCarthy dynasty of Muskerry is a tacksman branch of the MacCarthy Mor dynasty, the Kings of Desmond.

Origins and advancement

The MacCarthy of Muskerry are a cadet branch of the MacCarthy Mor ...

, the MacCarthys of Duhallow

Duhallow () is a barony located in the north-western part of County Cork, Ireland.

Legal context

Baronies were created after the Norman invasion of Ireland as divisions of counties and were used in the administration of justice and the raising ...

, and finally the most wealthy: the MacCarthy Reagh of independent Carbery, of whom Florence's father had been a (semi-)sovereign prince. It was into a complex interplay between the crown government and these opposing branches that Florence found himself pitched.

The Mac Carthaig Reagh branch established itself as loyal to the crown during the Desmond Rebellions

The Desmond Rebellions occurred in 1569–1573 and 1579–1583 in the Irish province of Munster.

They were rebellions by the Earl of Desmond, the head of the Fitzmaurice/FitzGerald Dynasty in Munster, and his followers, the Geraldines and ...

(1569–73 and 1579–83), to assert their independence from their nominal overlords, the Earl of Desmond and the Mac Carthaig Mór, both of whom had joined the rebellion. Mac Carthaig's father, Donnchadh Mac Carthaig Reagh, served the crown faithfully and reported that he had mobilised his men to drive the rebel Gerald FitzGerald, 15th Earl of Desmond out of his territory during the Second Desmond Rebellion. When his father died in 1581, Mac Carthaig, by then in his late teens or early twenties, led around 300 men in the English service with the assistance of an English captain, William Stanley, and his lieutenant, Jacques de Franceschi, under the overall command of the Earl of Ormonde. They drove Desmond's remaining followers out of MacCarthy territory, 'into his own waste country', where the rebel earls' troops could find no provisions and deserted. Mac Carthaig also claimed credit for the killings of Gorey MacSweeney and Morrice Roe, two of Desmond's gallowglass captains.

Upon his father's death in 1581, Mac Carthaig inherited substantial property but was not the prince's tanist (second in command and usually successor to the head), and therefore did not assume his father's title, which went to Mac Carthaig's uncle, Owen MacCarthy Reagh, 16th Prince of Carbery. The position of tanist went to Mac Carthaig's cousin, Donal na Pipi (Donal of the Pipes). But, in 1583, Mac Carthaig did go to court, where he was received by the queen, who granted him 1000 marks and an annuity of 100 marks. In 1585 he served as a member of the Irish Parliament at Dublin.

The Tower

Upon his marriage to Ellen, the daughter and sole heir of the Mac Carthaig Mór (alsoEarl of Clancare

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. The title originates in the Old English word ''eorl'', meaning "a man of noble birth or rank". The word is cognate with the Scandinavian form ''jarl'', and meant "chieftain", particular ...

), Fínghin mac Donncha fell foul of the crown government in Munster on account of the prospective unification of the two main branches of the Clan Carthy. To add to government suspicion, there was also a rumour of communications by him with Spain. In particular, he was accused of contact with William Stanley and Jacques de Franceschi, who had defected with a regiment of Irish soldiers from the English to the Spanish side in the Eighty Years' War

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt ( nl, Nederlandse Opstand) ( c.1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish government. The causes of the war included the Refo ...

in Flanders.

As a result of these suspicions, Mac Carthaig was arrested in 1588 as a precaution against his assumption of the title of Mac Carthaig Mór, which would have given him command over huge estates and thousands of followers. The English authorities considered this too dangerous a prospect in a country they were trying to pacify and disarm.

Initially detained by Carew at Shandon Castle in Cork, after six months Mac Carthaig was moved to Dublin, and then to London, where he arrived in February 1589 to be committed to the Tower. His wife escaped from Cork a few days later, probably on his instructions. Mac Carthaig was examined by the privy council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

in March and denied all complicity in the continental intrigues of the English Catholic, Sir William Stanley. He was sent back to the Tower, but fifteen months later his wife appeared at court and Sir Thomas Butler, 10th Earl of Ormonde

Thomas Butler, 10th Earl of Ormond and 3rd Earl of Ossory PC (Ire) (; – 1614), was an influential courtier in London at the court of Elizabeth I. He was Lord Treasurer of Ireland from 1559 to his death. He fought for the crown in the ...

, volunteered to stand surety for him in the sum of £1000. Since no charges were proved against him, Mac Carthaig was set at liberty in January 1591 on condition that he not leave England nor travel more than three miles outside London without permission.

The Queen's principal secretary, Lord Burghley, backed him, and he obtained protection against his creditors and permission to recover an old fine of £500 due to the Crown from Lord Barry, a neighbour and rival of his in Munster, whom he blamed for his arrest; Barry was later to accuse him of disloyalty as this suit was prosecuted. Mac Carthaig subsequently obtained permission to return to Ireland.

Succession disputes

Fínghin mac Donncha returned to Ireland (though he was still technically a prisoner) in November 1593, following his wife and child. In the next year, his uncle Owen (the Mac Carthaig Reagh) died and was succeeded by his nephew, Donal na Pípí. The latter bound himself in the sum of £10,000 not to divert the Mac Carthaig Reagh succession from MacCarthy, who was in turn his tanist. Mac Carthaig appeared before the council at Dublin in June 1594 to reply to the accusations of David de Barry, 5th Viscount Buttevant, a local rival of Mac Carthaig's with whom he had a land dispute, which again implicated him pro-Spanish intrigues with William Stanley. Florence then returned to England by licence and remained there until the spring of 1596 in a vain attempt to prosecute Lord Buttevant. The execution ofPatrick O'Collun

Patrick O'Collun , also known as Patrick Cullen or Patrick Collen, (died 1594) was an Irish soldier and fencing master who was executed at Tyburn in 1594 for treason, in that he had conspired to murder Queen Elizabeth I.

Background

Little is kno ...

, a fencing master, for conspiracy to murder the Queen in 1594 did nothing to restore Mac Carthaig's reputation since O'Collun had once been a member of his household.

In 1596, Donal Mac Carthaig, Mac Carthaig Mór and Earl of Clancarthy, died without male issue and the matter of the succession became highly complicated. Clancar's estate should by law have reverted to the crown, but Mac Carthaig had a mortgage on the lands and also had right by his wife. Another Donal, the Earl's illegitimate son (not to be confused with Donal na Pipi), also asserted a claim, not to the English Earldom, but to the title of Mac Carthaig Mór. Fínghin mac Donncha Mac Carthaig would in future correspondence refer to Donal as "Donal the bastard".

It was most unlikely that the English authorities would acknowledge Mac Carthaig or grant him the derived English title as they wanted to break up the Mac Carthaig lands; so the real dispute in law came down to the recovery of lands by Florence from an English mortgagee (William Brown), who had possessed them on account of a debt owed to him by the earl. In June 1598, Mac Carthaig travelled to England to pursue the matter.

However, the situation was transformed by the arrival in Munster of the Ulster forces of Hugh O'Neill, who was leading a nationwide rebellion – the Nine Years' War – against the English government in Ireland. In the autumn, Donal Mac Carthaig (the late Earl's illegitimate son) was reported to have acknowledged the authority of the rebel O'Neill and assumed the title of Mac Carthaig Mór, but the O'Sullivan Mór withheld the White Wand

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White on ...

or rod of inauguration (which symbolically approved the accession) in favour of Fínghin mac Donncha Mac Carthaig. In a desperate situation, when it seemed that all the native lords in Munster were going into rebellion, the crown granted Mac Carthaig a free pardon, on terms that he immediately withdraw his followers from rebellion in return for qualified acknowledgement of his title against Donal Mac Carthaig, but he prevaricated and only returned to Munster after Sir Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex

Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex, KB, PC (; 11 January 1591 – 14 September 1646) was an English Parliamentarian and soldier during the first half of the 17th century. With the start of the Civil War in 1642, he became the first Captain ...

– whose favour he had been relying upon – threw up his command as lord lieutenant in Ireland in late 1599 and returned to England under a cloud. Mac Carthaig had managed to negotiate English support for his claims to land and title, but he also maintained contact with the rebels to the same end. This has made some commentators claim that his real sympathy lay with the rebels, especially as he was described in his youth as being "very zealous in the old religion atholicism. However, it is more likely Fínghin mac Donncha was using both sides as a lever to further his own aims.

War in Munster

During theNine Years' War

The Nine Years' War (1688–1697), often called the War of the Grand Alliance or the War of the League of Augsburg, was a conflict between France and a European coalition which mainly included the Holy Roman Empire (led by the Habsburg monarch ...

in Munster, Mac Carthaig failed to engage with the English military campaign and secretly negotiated with the rebels under Hugh O'Neill and the Spanish. O'Neill's strategy was to back those local Irish lords who had a grievance against English authority and were in command of sufficient land and followers to contribute to his war effort.

In 1599, Mac Carthaig visited Fitzthomas, the rebel "Súgan" Earl of Desmond

Earl of Desmond is a title in the peerage of Ireland () created four times. When the powerful Earl of Desmond took arms against Queen Elizabeth Tudor, around 1578, along with the King of Spain and the Pope, he was confiscated from his estates, s ...

, in Carbery, where he claimed to have spoken in the queen's favour; it is more likely that Mac Carthaig promised his support for the rebels on condition that O'Neill acknowledge him as Mac Carthaig Mor. In the following days, Fitzthomas, followed reluctantly by Donal Mac Carthaig, laid waste to Lord Barry's territory of Ibawne, on the ground that Barry had refused to join the rebellion. From his base at Kinsale

Kinsale ( ; ) is a historic port and fishing town in County Cork, Ireland. Located approximately south of Cork City on the southeast coast near the Old Head of Kinsale, it sits at the mouth of the River Bandon, and has a population of 5,281 (a ...

, Fínghin mac Donncha closed all the approaches into his own country.

In 1600 O'Neill's army arrived in Munster and pitched camp between the rivers Lee

Lee may refer to:

Name

Given name

* Lee (given name), a given name in English

Surname

* Chinese surnames romanized as Li or Lee:

** Li (surname 李) or Lee (Hanzi ), a common Chinese surname

** Li (surname 利) or Lee (Hanzi ), a Chinese ...

and Bandon, whereupon MacCarthy came into the camp for an interview and was installed there as Mac Carthaig Mór at the expense of his rival, Donal Mac Carthaig. To the English, it now appeared that Mac Carthaig had sided conclusively with O'Neill, and military action was taken against him. In fact, Florence may simply have been playing both sides to become the Mac Carthaig Mor. In April an English expedition led by Captain George Flower raided his lands in Carbery and fought a bloody skirmish with Mac Carthaig's levies, which left over 200 men dead between the two sides.

In the same month, Sir George Carew was appointed governor of Munster, with sufficient men and resources to pacify the province. Carew summoned Mac Carthaig to Cork for an explanation of his conduct; at first, Mac Carthaig refused to come in without guarantees for his life and liberty, and when he did come in he refused to give his son as hostage. Carew urged him to support the English campaign, but Mac Carthaig promised no more than his neutrality, arguing that he was loyal, but that if he were to side openly with the English his own followers would desert him (a common plea of Gaelic leaders).

In fact, at this time Mac Carthaig, in an intercepted letter to Hugh Roe O'Donnell, had sought to assure the northern rebels of his commitment to their cause. He was also the main contact in the south of Ireland for the Spanish, who planned a landing in Munster, which Mac Carthaig most likely expected would settle the war for good. On 5 January 1600, he wrote to Philip II of Spain

Philip II) in Spain, while in Portugal and his Italian kingdoms he ruled as Philip I ( pt, Filipe I). (21 May 152713 September 1598), also known as Philip the Prudent ( es, Felipe el Prudente), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from ...

, via his agent in Ulster, Donagh mac Cormac Mac Carthaig, offering,

In the months that followed, Carew broke the rebellion in Munster, retaking rebel castles, arresting Fitzthomas, the Súgan Earl, and persuading Donal MacCarthy to change sides. Carew viewed this as highly significant, because Donal Mac Carthaig was not only a credible rival, but also knew the remote and mountainous terrain in which Fínghin mac Donncha was based. Having pacified the province, Carew had no intention of leaving Fínghin mac Donncha installed as MacCarthy Mór, judging that his supremacy would make any future English presence in the area impossible. To this end, he arrested Florence, having called him to his camp for talks, 14 days before the expiry of the safe conduct "on discretion" (i.e. without charge) – an action which, although unlawful, was approved by the Queen's secretary, Robert Cecil Robert Cecil may refer to:

* Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury (1563–1612), English administrator and politician, MP for Westminster, and for Hertfordshire

* Robert Cecil (1670–1716), Member of Parliament for Castle Rising, and for Wootton Ba ...

, for reasons of state.

The Irish ''Annals of the Four Masters

The ''Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland'' ( ga, Annála Ríoghachta Éireann) or the ''Annals of the Four Masters'' (''Annála na gCeithre Máistrí'') are chronicles of medieval Irish history. The entries span from the Deluge, dated as 2,24 ...

'' states:

Mac Carthaigm was sent to England in August 1601 and committed to the Tower. Carew also arrested Mac Carthaig's son, as well as his kinsmen, Dermot mac Owen and Taig mac Cormac, and his follower, O'Mahon. Only a month later, the Spanish landed at Kinsale

Kinsale ( ; ) is a historic port and fishing town in County Cork, Ireland. Located approximately south of Cork City on the southeast coast near the Old Head of Kinsale, it sits at the mouth of the River Bandon, and has a population of 5,281 (a ...

and enquired immediately for Mac Carthaig, their main local contact. His absence was no doubt a serious disadvantage in organising local support. Most of the Mhic Carthaig, including both Donal and Donal na Pipi, did go over to the Spanish side, but surrendered after the English victory over the Irish and Spanish at the Battle of Kinsale

The siege of Kinsale, or Battle of Kinsale ( ga, Léigear/Cath Chionn tSáile), was the ultimate battle in England's conquest of Gaelic Ireland, commencing in October 1601, near the end of the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, and at the climax of t ...

in 1601.

In custody in London

Mac Carthaig vainly petitioned for release from prison with a promise to serve against O'Neill. After the English victory at the battle of Kinsale, his brother, Diarmuid Maol ("Bald Dermot"), who commanded Fínghin mac Donncha's followers in his absence, was killed accidentally in a cattle-raid by some ofDonal II O'Donovan

Donal II O'Donovan ( ga, Domhnall Ó Donnabháin), The O'Donovan of Clann Cathail, Lord of Clancahill (died 1639), was the son of Ellen O'Leary, daughter of O'Leary of Inchigeelagh, Carrignacurra, and Donal of the Skins, The O'Donovan of Clann Ca ...

's men under the command of Fínghin Mac Carthaig, his first cousin, son of his uncle Owen; many of his kinsmen were also killed in various encounters with English or rival Irish forces. In 1604 he was transferred to the Marshalsea for his health, but sent back to the Tower, with the privilege of access to his books.

In 1606, Donal na Pípí surrendered his claim to the Mac Carthaig lordship and received a grant of the territory of Carbery. Then Sir Richard Boyle, Earl of Cork, and Lord Barry tried to wrest from Mac Carthaig the territory inherited from his father, but he successfully resisted by means of the law. However, much of his former lands were re-distributed. He went to the Marshalsea again in 1608, was released in 1614 on bonds of £5000 not to leave London, and in 1617 was recommitted to the Tower on the information of his servant, Teige O'Hurley, alleging his involvement with William Stanley and several exiled Irish Catholic priests and nobles, including Hugh Maguire. Mac Carthaig was due for release in 1619 but was sent back to the Gatehouse in 1624, to "a little narrow close room without sight of the air", owing to the death of two of his sureties, Donogh O'Brien, 4th Earl of Thomond

Donogh O'Brien, 4th Earl of Thomond and Baron Ibrickan, PC (Ire) (died 1624), was a Protestant Irish nobleman and soldier. He fought for Queen Elizabeth during Tyrone's Rebellion and participated in the Siege of Kinsale. He obtained the tran ...

and Sir Patrick Barnewall. He was freed in 1626 on fresh sureties and won his protracted suit for the barony of Molahiffe in 1630 (although the lands were still in the possession of the English mortgagees in 1637).

MacCarthy lived the remainder of his life in London, where he wrote a history of Ireland, Mac Carthaigh's Book, based on Old Irish

Old Irish, also called Old Gaelic ( sga, Goídelc, Ogham script: ᚌᚑᚔᚇᚓᚂᚉ; ga, Sean-Ghaeilge; gd, Seann-Ghàidhlig; gv, Shenn Yernish or ), is the oldest form of the Goidelic/Gaelic language for which there are extensive writt ...

texts. He wrote that, "although they he Irishare thought by many fitter to be rooted out than suffered to enjoy their lands, they are not so rebellious or dangerous as they are termed by such as covet it". He died in 1640.

Legacy

Mac Carthaig had a troubled relationship with his wife, who grew jealous of his inheritance and who informed on him to the English authorities. She also seems to have disapproved of his political choices, reportedly saying that she, "would not go begging in Ulster or Spain". In 1607 he reported that he had, "sent away that wicked woman that was my wife…whom I saw not nor could abide in almost a year before my commitment mprisonment. Nevertheless, he did have four children by her who are known: Teige (died as a boy in the Tower), Donal (who converted to Protestantism and married Sarah daughter of the MacDonnell Earl of Antrim), Florence (married Mary daughter ofDonal III O'Donovan

Donal III O'Donovan ( ga, Domhnall Ó Donnabháin), The O'Donovan of Clancahill, born before 1584, was the son of Helena de Barry and Donal II O'Donovan, The O'Donovan of Clancahill. From the inauguration of his father in 1584 to the date of his ...

), and Cormac (Charles).

In time, the title of Mac Carthaig Mór was subdued and the personal lands of Fínghin mac Donncha Mac Carthaig were distributed to English settlers, among them Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Cork

Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Cork (13 October 1566 – 15 September 1643), also known as the Great Earl of Cork, was an English politician who served as Lord Treasurer of the Kingdom of Ireland.

Lord Cork was an important figure in the continuing ...

. The MacCarthy lords, including Donal na Pipi of Carberry, Donal MacCarthy (son of the earl) and Dermot MacCarthy of Muskerry were granted title to their lands, but had to surrender up to a third of their inheritance to the crown. Donagh MacCarthy, the son of Dermot Mac Carthaig, later created Viscount of Muskerry, would later be one of the leaders of the Irish Rebellion of 1641

The Irish Rebellion of 1641 ( ga, Éirí Amach 1641) was an uprising by Irish Catholics in the Kingdom of Ireland, who wanted an end to anti-Catholic discrimination, greater Irish self-governance, and to partially or fully reverse the plantatio ...

and Confederate Ireland in the 1640s.

A rough portrait of Mac Carthaig was taken to France in 1776 by a collateral kinsman, Justin Mac Carthaig (1744–1811) of Springhouse, Bansha, County Tipperary, who was a direct descendant of Dónal na Pípí and was going into exile because of the harsh treatment in Ireland of Catholics under the Penal Laws. The portrait was kept in the mansion at 3, Rue Mage in the city of Toulouse

Toulouse ( , ; oc, Tolosa ) is the prefecture of the French department of Haute-Garonne and of the larger region of Occitania. The city is on the banks of the River Garonne, from the Mediterranean Sea, from the Atlantic Ocean and from Par ...

where he resided as Count MacCarthy-Reagh of Toulouse. The Count was noted for his rich library which in importance was second only to the King's in Paris.

An anonymous writer in 1686 wrote of Fínghin mac Donncha Mac Carthaig, drawing on a contemporary description in ''Pacata Hibernia'', Of all the MacCarthys, none was ever more famous than…Florence, who was a man of extraordinary stature (being like Saul higher by the head and shoulders than any of his followers) and as great policy with competent courage and as much zeal as anybody for what he falsely imagined to be the true religion, and the liberty of his country''. However, his rival Donal "the bastard" MacCarthy described him as "a damned counterfeit Englishman whose study and practice was to deceive and betray all the Irishmen in Ireland".

See also

* Irish nobility *Eóganachta

The Eóganachta or Eoghanachta () were an Irish dynasty centred on Cashel which dominated southern Ireland (namely the Kingdom of Munster) from the 6/7th to the 10th centuries, and following that, in a restricted form, the Kingdom of Desmond, an ...

* Tudor conquest of Ireland

*Nine Years' War (Ireland)

The Nine Years' War, sometimes called Tyrone's Rebellion, took place in Ireland from 1593 to 1603. It was fought between an Irish alliance—led mainly by Hugh O'Neill of Tyrone and Hugh Roe O'Donnell of Tyrconnell—against English rule in ...

* Mac Carthaigh's Book

References

Notes

Sources

*Richard Bagwell, ''Ireland under the Tudors'' 3 vols. (London, 1885–1890). *John O'Donovan (ed.) ''Annals of Ireland by the Four Masters'' (1851). *''Calendar of State Papers: Carew MSS.'' 6 vols (London, 1867–1873). *''Calendar of State Papers: Ireland'' (London) *Colm Lennon ''Sixteenth Century Ireland – The Incomplete Conquest'' (Dublin, 1995) . *Nicholas P. Canny ''Making Ireland British, 1580–1650'' (Oxford University Press, 2001). . *Steven G. Ellis ''Tudor Ireland'' (London, 1985). . *Hiram Morgan ''Tyrone's War'' (1995). *Cyril Falls ''Elizabeth's Irish Wars'' (1950; reprint London, 1996). . *''Dictionary of National Biography'' 22 vols. (London, 1921–1922): of questionable accuracy in parts, but very useful. *Richard Cox, ''Hibernia Anglicana,'' London, 1689. *Daniel McCarthy, ''The Life and Letter book of Florence McCarthy Reagh, Tanist of Carberry,'' Dublin 1867. *John O’Donovan, (translator), ''The Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland by the Four Masters nnála Ríoghachta Éireann'' Vol. 6, ed. John O'Donovan (Dublin, 1848–51) at http://celt.ucc.ie/index.html *Stafford, Thomas, ''Pacata Hibernia'' 3 Vols. (1633), London 1810, also published in Dublin 1896 (Standish Hayes O'Grady ed.) {{DEFAULTSORT:MacCarthy, Florence MacCarthy dynasty Irish lords 1560 births 1640 deaths Writers from County CorkMacCarthy

MacCarthy ( ga, Mac Cárthaigh), also spelled Macarthy, McCarthy or McCarty, is an Irish clan originating from Munster, an area they ruled during the Middle Ages. It was divided into several great branches; the MacCarthy Reagh, MacCarthy of Mu ...

16th-century Irish people

17th-century Irish people

Prisoners in the Tower of London

People of the Nine Years' War (Ireland)

People from Kilbrittain

16th-century Irish writers

17th-century Irish writers