Flora Japonica (1784 book) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Carl Peter Thunberg, also known as Karl Peter von Thunberg, Carl Pehr Thunberg, or Carl Per Thunberg (11 November 1743 – 8 August 1828), was a

In August 1775, he arrived at the Dutch

In August 1775, he arrived at the Dutch

A genus of tropical plants, ''

A genus of tropical plants, ''

Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

naturalist and an "apostle" of Carl Linnaeus. After studying under Linnaeus at Uppsala University, he spent seven years travelling in southern Africa and Asia, collecting and describing many plants and animals new to European science, and observing local cultures. He has been called "the father of South African botany

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek w ...

", "pioneer of Occidental Medicine in Japan", and the "Japanese Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the ...

".

Early life

Thunberg was born and grew up inJönköping

Jönköping (, ) is a city in southern Sweden with 112,766 inhabitants (2022). Jönköping is situated on the southern shore of Sweden's second largest lake, Vättern, in the province of Småland.

The city is the seat of Jönköping Municipali ...

, Sweden. At the age of 18, he entered Uppsala University

Uppsala University ( sv, Uppsala universitet) is a public university, public research university in Uppsala, Sweden. Founded in 1477, it is the List of universities in Sweden, oldest university in Sweden and the Nordic countries still in opera ...

where he was taught by Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the ...

, regarded as the "father of modern taxonomy

Taxonomy is the practice and science of categorization or classification.

A taxonomy (or taxonomical classification) is a scheme of classification, especially a hierarchical classification, in which things are organized into groups or types. ...

". Thunberg graduated in 1767 after 6 years of studying. To deepen his knowledge in botany, medicine and natural history, he was encouraged by Linnaeus in 1770 to travel to Paris and Amsterdam. In Amsterdam and Leiden Thunberg met the Dutch botanist and physician Johannes Burman

Johannes Burman (26 April 1707 in Amsterdam – 20 February 1780), was a Dutch botanist and physician. Burman specialized in plants from Ceylon, Amboina and Cape Colony. The name '' Pelargonium'' was introduced by Johannes Burman.

Johannes ...

and his son Nicolaas Burman, who himself had been a disciple of Linnaeus.

Having heard of Thunberg's inquisitive mind, his skills in botany and medicine and Linnaeus' high esteem of his Swedish pupil, Johannes Burman and Laurens Theodorus Gronovius

Laurens Theodoor Gronovius (1 June 1730 – 8 August 1777), also known as Laurentius Theodorus Gronovius or as Laurens Theodoor Gronow, was a Dutch naturalist born in Leiden. He was the son of botanist Jan Frederik Gronovius (1686–1762).

Throu ...

, a councillor of Leiden, convinced Thunberg to travel to either the West or the East Indies to collect plant and animal specimens for the botanic garden at Leiden, which was lacking exotic exhibits. Thunberg was eager to travel to the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is t ...

and apply his knowledge.

With the help of Burman and Gronovius, Thunberg entered the Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock ...

(Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock co ...

, V.O.C.) as a surgeon on board the ''Schoonzicht''. As the East Indies were under Dutch control, the only way to enter the colonies was via the V.O.C. Hence, Thunberg embarked in December 1771. In March 1772, he reached Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

in now South Africa.

South Africa

During his three-year stay, Thunberg perfected his Dutch and studied the culture of theKhoikhoi

Khoekhoen (singular Khoekhoe) (or Khoikhoi in the former orthography; formerly also ''Hottentot (racial term), Hottentots''"Hottentot, n. and adj." ''OED Online'', Oxford University Press, March 2018, www.oed.com/view/Entry/88829. Accessed 13 ...

, (known to the Dutch as "Hottentotten"), the native people of western South Africa. The Khoikhoi were the first non-European culture he encountered. Their customs and traditions elicited both his disgust and admiration. For example, he considered their custom to grease their skin with fat and dust as an obnoxious habit about which he wrote in his travelogue: "For uncleanliness, the Hottentots have the greatest love. They grease their entire body with greasy substances and above this, they put cow dung, fat or something similar."Thunberg 1986, p. 180 Yet, this harsh judgement is moderated by the reason he saw for this practice and so he continues that: "This stops up their pores and their skin is covered with a thick layer which protects it from heat in Summer and from cold during Winter." This attitude – to try to justify rituals he did not understand – also marked his encounters with Japanese people.

Since the main purpose for his journey was to collect specimens for the gardens in Leiden, Thunberg regularly took field trips into the interior of South Africa. Between September 1772 and January 1773, he accompanied the Dutch superintendent of the V.O.C. garden, Johan Andreas Auge. Their journey took them to the north of Saldanha Bay

Saldanha Bay ( af, Saldanhabaai) is a natural harbour on the south-western coast of South Africa. The town that developed on the northern shore of the bay, also called Saldanha, was incorporated with five other towns into the Saldanha Bay Local Mu ...

, east along the Breede Valley

Breede River Valley is a region of Western Cape Province, South Africa known for being the largest fruit and wine producing valley in the Western Cape, as well as South Africa's leading race-horse breeding area. It is part of the Boland bordering ...

through the Langkloof

The Langkloof is a 160 km long valley in South Africa, lying between Herold, a small village northeast of George, and The Heights - just beyond Twee Riviere.

History

The kloof was given its name by Isaq Schrijver in 1689, and more thorough ...

as far as the Gamtoos River

Gamtoos River or Gamptoos River is a river in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. It is formed by the confluence of the Kouga River and the Groot River (Eastern Cape), Groot River and is approximately long

with a catchment area of .

Cours ...

and returning by way of the Little Karoo

The Karoo ( ; from the Afrikaans borrowing of the South Khoekhoe !Orakobab or Khoemana word ''ǃ’Aukarob'' "Hardveld") is a semi-desert natural region of South Africa. No exact definition of what constitutes the Karoo is available, so its ext ...

. During this expedition and later, Thunberg kept in regular contact with scholars in Europe, especially the Netherlands and Sweden, but also with other members of the V.O.C. who sent him animal skins. Shortly after returning, Thunberg met Francis Masson

Francis Masson (August 1741 – 23 December 1805) was a Scotland, Scottish botanist and gardener, and Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Kew Gardens’ first Botanical expedition, plant hunter.

Life

Masson was born in Aberdeen.

In the 1760s, he ...

, a Scots gardener who had come to Cape Town to collect plants for the Royal Gardens at Kew

Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew is a non-departmental public body in the United Kingdom sponsored by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. An internationally important botanical research and education institution, it employs 1,100 ...

. They were drawn together by their shared interests. During one of their trips, they were joined by Robert Jacob Gordon

Robert Jacob Gordon (29 September 1743, in Doesburg, Gelderland – 25 October 1795, in Cape Town) was a Dutch explorer, soldier, artist, naturalist and linguist of Scottish descent.

Life

Robert Jacob Gordon was the son of Maj. General Jacob ...

, on leave from his regiment in the Netherlands. Together, the scientists undertook two further inland expeditions.

During his three expeditions into the interior, Thunberg collected many specimens of both flora and fauna. At the initiative of Linnaeus, he graduated at Uppsala as Doctor of Medicine in absentia while he was at the Cape in 1772. Thunberg left the Cape for Batavia

Batavia may refer to:

Historical places

* Batavia (region), a land inhabited by the Batavian people during the Roman Empire, today part of the Netherlands

* Batavia, Dutch East Indies, present-day Jakarta, the former capital of the Dutch East In ...

on 2 March 1775. He arrived in Batavia on 18 May 1775, and left for Japan on 20 June.

Japan

In August 1775, he arrived at the Dutch

In August 1775, he arrived at the Dutch factory

A factory, manufacturing plant or a production plant is an industrial facility, often a complex consisting of several buildings filled with machinery, where workers manufacture items or operate machines which process each item into another. T ...

of the V.O.C. at Dejima

, in the 17th century also called Tsukishima ( 築島, "built island"), was an artificial island off Nagasaki, Japan that served as a trading post for the Portuguese (1570–1639) and subsequently the Dutch (1641–1854). For 220 years, it ...

, a small artificial island

An artificial island is an island that has been constructed by people rather than formed by natural means. Artificial islands may vary in size from small islets reclaimed solely to support a single pillar of a building or structure to those tha ...

(120 m by 75 m) in the Bay of Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in the ...

connected to the city by a single small bridge. However, like the Dutch merchants, Thunberg was at first rarely allowed to leave the island. These restrictions had been imposed by the Japanese ''shogun'' Tokugawa Ieyasu

was the founder and first ''shōgun'' of the Tokugawa Shogunate of Japan, which ruled Japan from 1603 until the Meiji Restoration in 1868. He was one of the three "Great Unifiers" of Japan, along with his former lord Oda Nobunaga and fellow ...

in 1639 after the Portuguese, who had been the first Europeans to arrive in Japan in 1543, persisted in missionary activity. The only locals who were allowed regular contact with the Dutch were the interpreters of Nagasaki and the relevant authorities of the city.

Shortly after the ''Schoonzicht's'' arrival on Deshima, Thunberg was appointed head surgeon of the trading post. To still be able to collect specimens of Japanese plants and animals as well as to gather information on the population, Thunberg began to construct networks with the interpreters by sending them small notes containing medical knowledge and receiving botanical knowledge or rare Japanese coins in return. Quickly, the news spread that a well-educated Dutch physician was in town who seemed to be able to help the local doctors cure syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms of syphilis vary depending in which of the four stages it presents (primary, secondary, latent, an ...

, known in Japan as the "Dutch disease". As a result, the appropriate authorities granted him more visits to the city and finally even allowed him one-day trips into the vicinity of Nagasaki, where Thunberg had the chance to collect specimens by himself.

During his visits in town, Thunberg began to recruit students, mainly the Nagasaki interpreters and local physicians. He taught them new medical treatments, such as using mercury to treat syphilis, and the production of new medicines. During this process, he also instructed his pupils in the Dutch language and European manners, furthering the growing interest into Dutch and European culture by the Japanese, known as ''rangaku

''Rangaku'' (Kyūjitai: /Shinjitai: , literally "Dutch learning", and by extension "Western learning") is a body of knowledge developed by Japan through its contacts with the Dutch enclave of Dejima, which allowed Japan to keep abreast of Wester ...

''. Thunberg had brought some seeds of European vegetables with him and showed the Japanese some botanical practices, expanding Japanese horticultural practices.

Thunberg also profited from his teachings himself. As a former medical student he was mainly interested in medical knowledge, and the Japanese showed him the practice of acupuncture

Acupuncture is a form of alternative medicine and a component of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) in which thin needles are inserted into the body. Acupuncture is a pseudoscience; the theories and practices of TCM are not based on scientifi ...

. The exchange of ideas between Thunberg and the local physicians led to the development of a new acupuncture point called '' shakutaku''. The discovery of ''shakutaku'' was a result of Thunberg's anatomic knowledge and the Japanese traditional medicine of neuronic moxibustion

Moxibustion () is a traditional Chinese medicine therapy which consists of burning dried mugwort ('' wikt:moxa'') on particular points on the body. It plays an important role in the traditional medical systems of China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, ...

. Thunberg brought back knowledge on Japan's religion and societal structure, boosting interest into Japan, an early cultural form of Japonism

''Japonisme'' is a French term that refers to the popularity and influence of Japanese art and design among a number of Western European artists in the nineteenth century following the forced reopening of foreign trade with Japan in 1858. Japon ...

.

In both countries, Thunberg's knowledge exchange led to a cultural opening-up, which also manifested itself in the spread of universities and boarding schools which taught knowledge of the other culture. For this reason, Thunberg has been called "the most important eye witness of Tokugawa Japan

The or is the period between 1603 and 1867 in the history of Japan, when Japan was under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate and the country's 300 regional ''daimyo''. Emerging from the chaos of the Sengoku period, the Edo period was characterize ...

in the eighteenth century".

Due to his scientific reputation, Thunberg was given the opportunity in 1776 to accompany the Dutch ambassador M. Feith to the shogun's court in Edo, today's Tokyo. During that journey, he collected many specimens of plants and animals and talked to locals along the way. It is during this time that Thunberg started writing two of his scientific works, the ''Flora Japonica'' (1784) and the '' Fauna Japonica'' (1833). The latter was completed by the German traveller Philipp Franz von Siebold

Philipp Franz Balthasar von Siebold (17 February 1796 – 18 October 1866) was a German physician, botanist and traveler. He achieved prominence by his studies of Japanese flora (plants), flora and fauna (animals), fauna and the introduction of ...

, who visited Japan between 1823 and 1829 and based the ''Fauna Japonica'' on Thunberg's notes which he carried with him all the time in Japan.

On his way to Edo, Thunberg also obtained many Japanese coins, which he described in detail in the fourth volume of his travelogue, ''Travels in Europe, Africa and Asia, performed between the Years 1770 and 1779''. The coins provided new insights for European scholars into the culture, religion and history of Japan, as their possession and export by foreigners had been strictly forbidden by the shogun. This prohibition had been imposed to prevent the Empire of China

The earliest known written records of the history of China date from as early as 1250 BC, from the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BC), during the reign of king Wu Ding. Ancient historical texts such as the '' Book of Documents'' (early chapte ...

and other rivals of the shogunate from copying the money and flooding the Japanese markets with forged coins.

In November 1776, after Thunberg had returned from the shogun's court, he left for Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's List ...

, now part of Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guine ...

. From there, he travelled to Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

(now Sri Lanka) in July 1777. Here again, his major interest lay in collecting plants and other specimens.

In February 1778, Thunberg left Ceylon to return to Europe.

Return to Europe

In 1778, Thunberg left Ceylon for Amsterdam, with a two week stay at the Cape. He finally arrived at Amsterdam in October 1778. He made a short trip to London where he metJoseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1820) was an English naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences.

Banks made his name on the 1766 natural-history expedition to Newfoundland and Labrador. He took part in Captain James ...

. He saw there the Japanese collection from the 1680s of the German naturalist Engelbert Kaempfer

Engelbert Kaempfer (16 September 16512 November 1716) was a German naturalist, physician, explorer and writer known for his tour of Russia, Persia, India, Southeast Asia, and Japan between 1683 and 1693.

He wrote two books about his travels. ''A ...

(1651–1716), who had preceded him at Dejima. He also met Forster, who showed him his collections from Cook

Cook or The Cook may refer to:

Food preparation

* Cooking, the preparation of food

* Cook (domestic worker), a household staff member who prepares food

* Cook (professional), an individual who prepares food for consumption in the food industry

* ...

's second voyage.

On arrival in Sweden in March 1779, he learned of the death of Linnaeus one year earlier. Thunberg was first appointed botanical demonstrator in 1777, and in 1781 professor of medicine and natural philosophy at the University of Uppsala. His publications and specimens resulted in the description of many new taxa.

He published his ''Flora Japonica'' in 1784, and in 1788 he began to publish his travels. He completed his ''Prodromus Plantarum'' in 1800, his ''Icones Plantarum Japonicarum'' in 1805, and his ''Flora Capensis'' in 1813. He published numerous memoirs in the transactions of various Swedish and international scientific societies. He was an honorary member of sixty-six scientific societies. In 1776, while still in Asia, he had been elected a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences ( sv, Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien) is one of the Swedish Royal Academies, royal academies of Sweden. Founded on 2 June 1739, it is an independent, non-governmental scientific organization that takes special ...

. He was elected a member of the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

in 1791. In 1809 he became correspondent, and in 1823 an associate member of the Royal Institute of the Netherlands.

He died at Thunaberg near Uppsala

Uppsala (, or all ending in , ; archaically spelled ''Upsala'') is the county seat of Uppsala County and the List of urban areas in Sweden by population, fourth-largest city in Sweden, after Stockholm, Gothenburg, and Malmö. It had 177,074 inha ...

on 8 August 1828.

Reasons for his travels

It was common for Enlightenment scholars to travel throughout Europe and to more distant regions, and to write subsequent travelogues. However, Thunberg was notable in his travel destination and the popularity of his account of his travels, which was translated into German, English and French. Three main reasons for this have been proposed: # Besides being encouraged by Linnaeus and Gronovius to travel to Japan, the fact that, for half a century, no new information on the country had reached Europe attracted Thunberg to travel there. In 1690,Engelbert Kaempfer

Engelbert Kaempfer (16 September 16512 November 1716) was a German naturalist, physician, explorer and writer known for his tour of Russia, Persia, India, Southeast Asia, and Japan between 1683 and 1693.

He wrote two books about his travels. ''A ...

, a German traveller, had sailed to Japan and spent two years on the island of Deshima. Kaempfer's 1729 travelogue became a famous work on the shogunate; yet, when Thunberg came to Japan, Kaempfer's writings were already more than fifty years old.Jung 2002, pp. 90–92 The time was right for new knowledge.

# The Age of Enlightenment furthered a scientific hunger for new information. In the light of the increasing emphasis on using the rational human mind, many students were keen to leave the boundaries of Europe and apply their knowledge and gather new insights about less well-known regions.

# Thunberg was a very inquisitive and intelligent man, a "person of acute mind"Screech, T. (2012). ''Japan Extolled and Decried: Carl Peter Thunberg and the Shogun’s Realm, 1775 – 1776''. Routledge: Taylor and Francis Group, London and New York, p. 2 who sought new challenges. Hence, the journey was in Thunberg's personal interest and complied well with his character.

Namesake plants

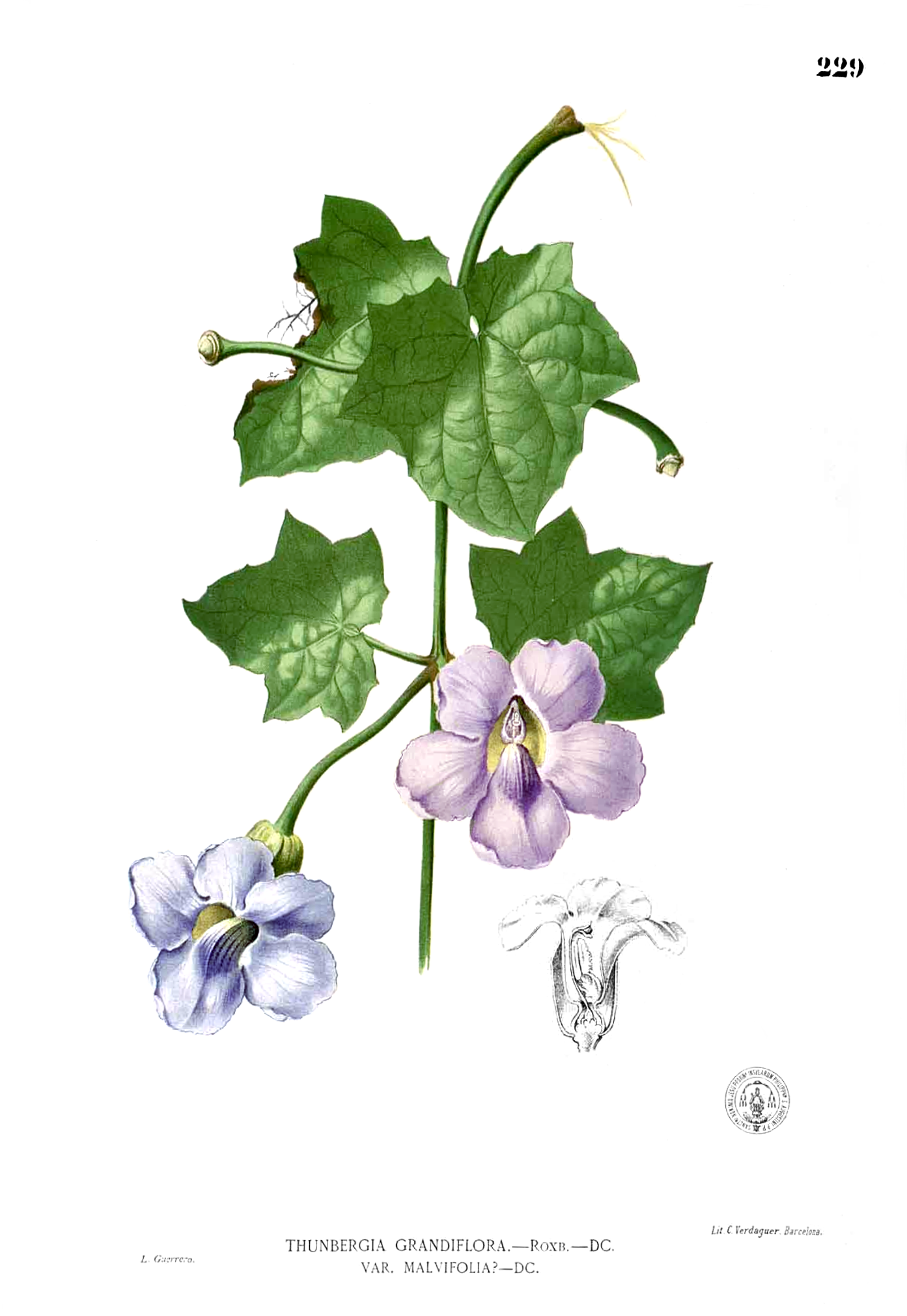

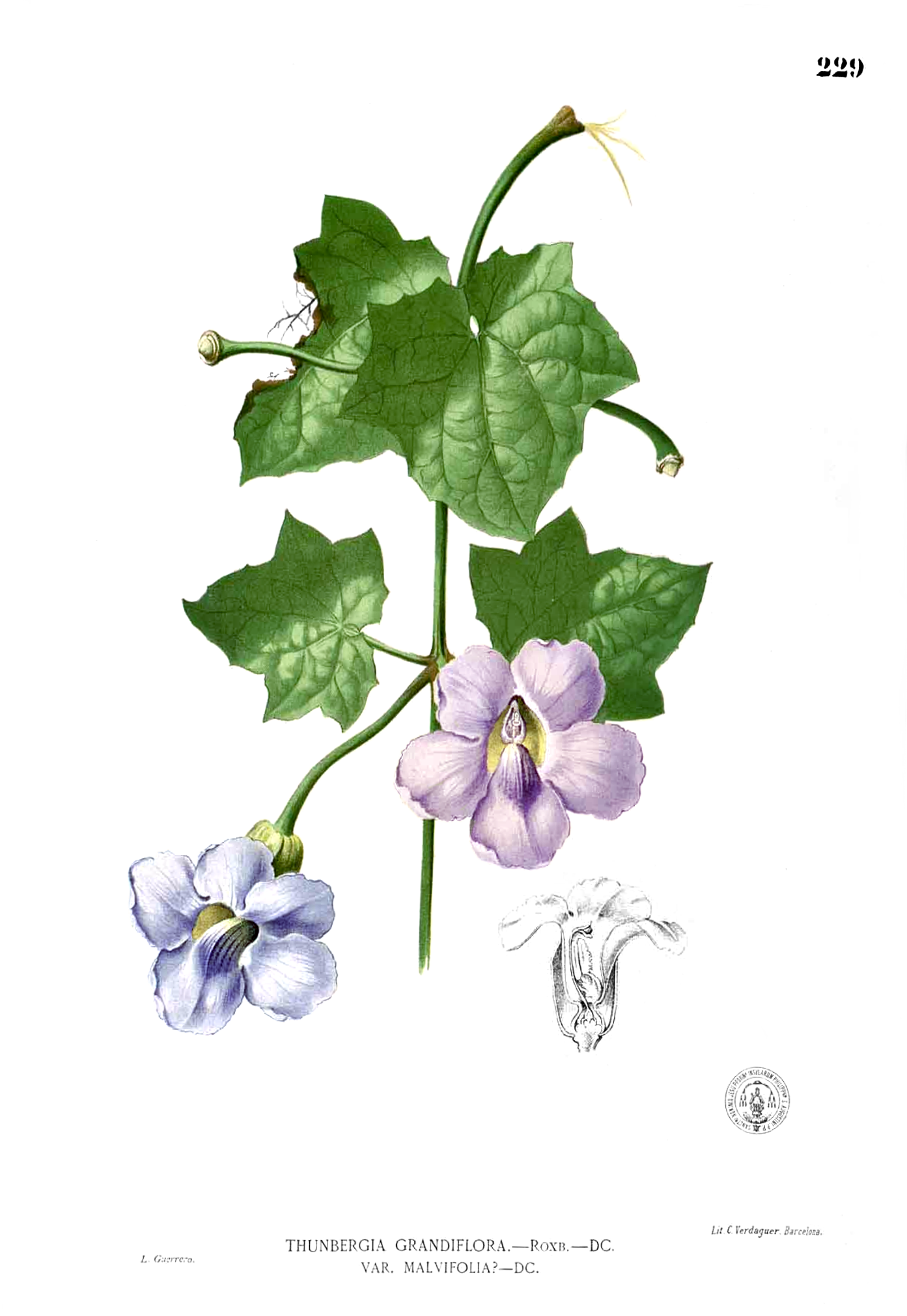

A genus of tropical plants, ''

A genus of tropical plants, ''Thunbergia

''Thunbergia'' is a genus of flowering plants in the family Acanthaceae, native to tropical regions of Africa, Madagascar and southern Asia. ''Thunbergia'' species are vigorous annual or perennial vines and shrubs growing to 2–8 m tall. The ge ...

'', family Acanthaceae

Acanthaceae is a family (the acanthus family) of dicotyledonous flowering plants containing almost 250 genera and about 2500 species. Most are tropical herbs, shrubs, or twining vines; some are epiphytes. Only a few species are distributed in te ...

, which are cultivated as evergreen climbers, is named after him.

Thunberg is cited in naming some 254 species of both plants and animals (though significantly more plants than animals). Notable examples of plants referencing Thunberg in their specific epithet

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called nomenclature ("two-name naming system") or binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, bot ...

s include:

*''Allium thunbergii

thumb

''Allium thunbergii'', Thunberg's chive or Thunberg garlic, is an East Asian species of wild onion native to Japan (incl Bonin + Ryukyu Islands), Korea, and China (incl. Taiwan). It grows at elevations up to 3000 m. The Flora of China reco ...

''

*''Amaranthus thunbergii

''Amaranthus thunbergii'', commonly known as Thunberg's amaranthus or Thunberg's pigweed, is found in Africa.

The leaves are used as a flavouring or leafy vegetable.Grubben, G.J.H. & Denton, O.A. (2004) Plant Resources of Tropical Africa 2. Vege ...

''

*''Arisaema thunbergii

''Arisaema thunbergii'', commonly known as Asian jack-in-the-pulpit, is a plant species in the family Araceae

The Araceae are a family of monocotyledonous flowering plants in which flowers are borne on a type of inflorescence called a spa ...

''

*''Berberis thunbergii

''Berberis thunbergii'', the Japanese barberry, Thunberg's barberry, or red barberry, is a species of flowering plant in the barberry family Berberidaceae, native to Japan and eastern Asia, though widely naturalized in China and North America, w ...

''

*'' Fritillaria thunbergii''

*''Geranium thunbergii

''Geranium thunbergii'' (Thunberg's geranium) is a cranesbill species that iscommonly known as Japanese geranium or Japanese cranesbill. It is one of the most popular folk medicines and also an official antidiarrheic drug in Japan.Structure of ...

''

*''Lespedeza thunbergii

''Lespedeza thunbergii'' is a species of flowering plant in the Fabaceae, legume family (biology), family known by the common names Thunberg's bushclover, Thunberg's lespedeza, and shrub lespedeza. It is native to China and Japan.

This species p ...

''

*''Pinus thunbergii

''Pinus thunbergii'' (syn: ''Pinus thunbergiana''), also called black pine, Japanese black pine, and Japanese pine, is a pine tree native to coastal areas of Japan (Kyūshū, Shikoku and Honshū) and South Korea.

It is called () in Korean, () ...

''

*''Spiraea thunbergii

''Spiraea thunbergii'' (珍珠绣线菊), Thunberg spiraea or Thunberg's meadowsweet, is a species of flowering plant in the rose family, native to East China and Japan, and widely cultivated elsewhere.

Names

Other common names include baby's br ...

''

Selected publications

;Botany *''Flora Japonica'' (1784) *Edo travel accompaniment. *''Prodromus Plantarum Capensium'' (Uppsala, vol. 1: 1794, vol. 2: 1800)''Prodromus Plantarum Capensium'' at Biodiversity Heritage Library. (see ''External links'' below). *''Flora Capensis'' (1807, 1811, 1813, 1818, 1820, 1823) *''Voyages de C.P. Thunberg au Japon par le Cap de Bonne-Espérance, les Isles de la Sonde'', etc. *''Icones plantarum japonicarum'' (1805) ;Entomology *''Donationis Thunbergianae 1785 continuatio I. Museum naturalium Academiae Upsaliensis'', pars III, 33–42 pp. (1787). *''Dissertatio Entomologica Novas Insectorum species sistens, cujus partem quintam. Publico examini subjicit Johannes Olai Noraeus, Uplandus''. Upsaliae, pp. 85–106, pl. 5. (1789). *''D. D. Dissertatio entomologica sistens Insecta Suecica. Exam. Jonas Kullberg''. Upsaliae, pp. 99–104 (1794).See also

*An'ei

was a after ''Meiwa'' and before ''Tenmei.'' This period spanned the years November 1772 through March 1781. The reigning emperors were and .

Change of era

* 1772 : The era name was changed to ''An'ei'' (meaning "peaceful eternity") to mark t ...

* Kuze Hirotami

(1737–1800), also known as , was a Japanese politician during late 18th-century ''Nagasaki bugyō'' or governor of Nagasaki port, located on southwestern shore of Kyūshū island in the Japanese archipelago.Screech, Timon. (2006). ''Secret Mem ...

* Sakoku

was the Isolationism, isolationist Foreign policy of Japan, foreign policy of the Japanese Tokugawa shogunate under which, for a period of 265 years during the Edo period (from 1603 to 1868), relations and trade between Japan and other countri ...

* List of Westerners who visited Japan before 1868

This list contains notable Europeans and Americans who visited Japan before the Meiji Restoration. The name of each individual is followed by the year of the first visit, the country of origin, and a brief explanation.

16th century

* Two Portugu ...

Notes

References

* * Jung, C. (2002). ''Kaross und Kimono: „Hottentotten“ und Japaner im Spiegel des Reiseberichts von Carl Peter Thunberg, 1743 – 1828.'' aross and Kimono: “Hottentots” and Japanese in the Mirror of Carl Peter Thunberg's Travelogue, 1743 – 1828 Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart, Germany *Skuncke, Marie-Christine (2014). ''Carl Peter Thunberg: Botanist and Physician.''Swedish Collegium for Advanced Studies, Uppsala, Sweden * Thunberg, C. P. (1986). ''Travels at the Cape of Good Hope, 1772–1775 : based on the English edition London, 1793–1795''. (Ed. V. S. Forbes) LondonExternal links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Thunberg, Carl Peter 18th-century Swedish botanists 18th-century male writers 18th-century non-fiction writers 18th-century Swedish physicians 18th-century Swedish zoologists 1743 births 1828 deaths Age of Liberty people Botanical writers Botanists active in Africa Botanists active in Japan Bryologists Burials at Uppsala old cemetery Dutch East India Company people Fellows of the Royal Society Honorary members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences Japanologists Members of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences People from Jönköping Pteridologists Swedish entomologists Swedish expatriates in Japan Swedish lepidopterists Swedish male writers Swedish mycologists Swedish non-fiction writers Swedish ornithologists Swedish phycologists Swedish taxonomists Taxon authorities of Hypericum species Swedish expatriates in the Dutch Republic Male non-fiction writers 19th-century Swedish botanists