Flavivirus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Flavivirus'' is a genus of

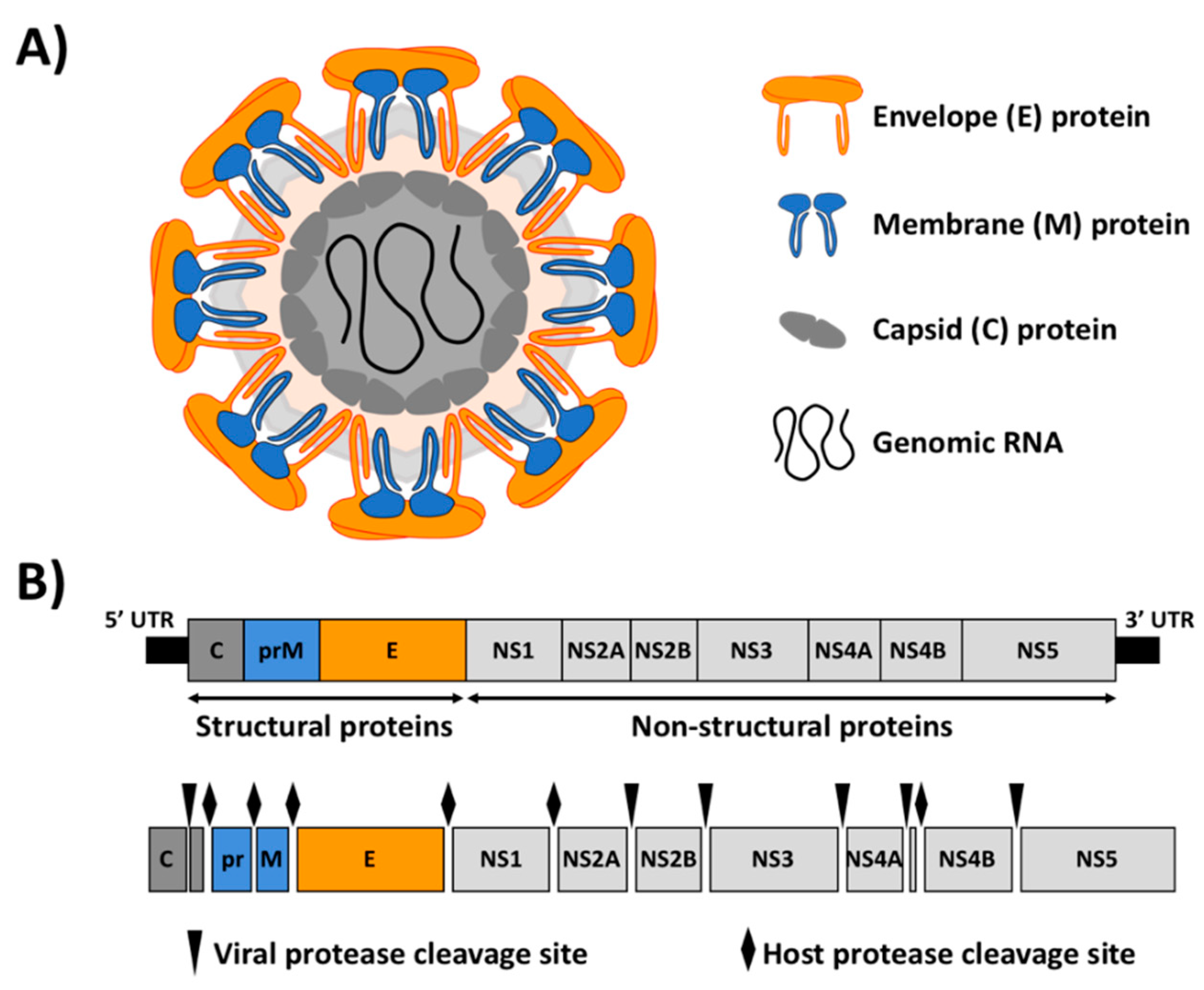

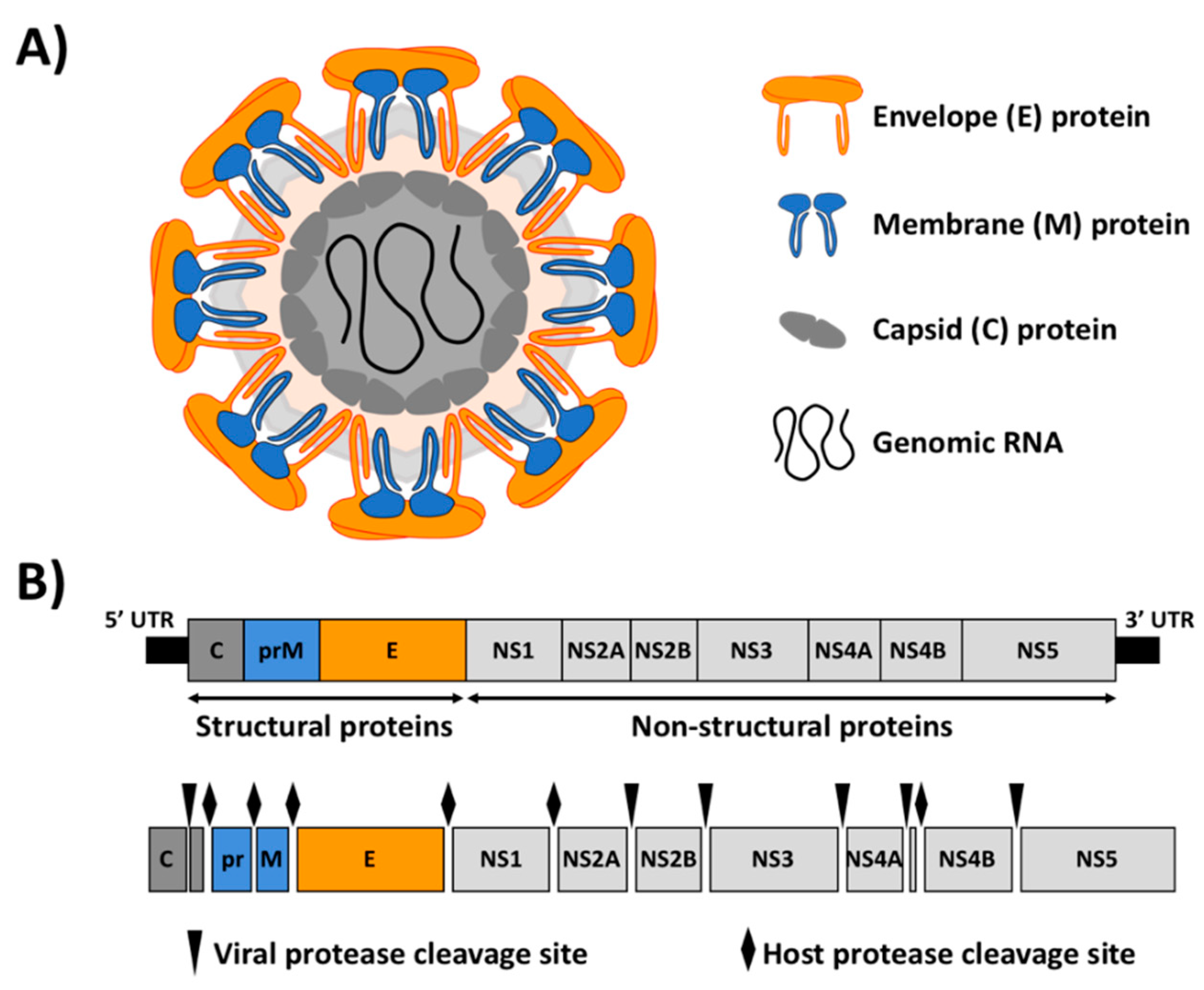

Flaviviruses are enveloped and spherical and have icosahedral geometries with a pseudo T=3 symmetry. The virus particle diameter is around 50 nm.

Flaviviruses are enveloped and spherical and have icosahedral geometries with a pseudo T=3 symmetry. The virus particle diameter is around 50 nm.

Flaviviruses replicate in the

Flaviviruses replicate in the  Once

Once

The positive sense RNA genome of ''Flavivirus'' contains 5' and 3'

The positive sense RNA genome of ''Flavivirus'' contains 5' and 3'

The 3'UTRs are typically 0.3–0.5 kb in length and contain a number of highly conserved

The 3'UTRs are typically 0.3–0.5 kb in length and contain a number of highly conserved  These two conserved secondary structures are also known as pseudo-repeat elements. They were originally identified within the genome of ''Dengue virus'' and are found adjacent to each other within the 3'UTR. They appear to be widely conserved across the Flaviviradae. These DB elements have a secondary structure consisting of three helices and they play a role in ensuring efficient translation. Deletion of DB1 has a small but significant reduction in translation but deletion of DB2 has little effect. Deleting both DB1 and DB2 reduced

These two conserved secondary structures are also known as pseudo-repeat elements. They were originally identified within the genome of ''Dengue virus'' and are found adjacent to each other within the 3'UTR. They appear to be widely conserved across the Flaviviradae. These DB elements have a secondary structure consisting of three helices and they play a role in ensuring efficient translation. Deletion of DB1 has a small but significant reduction in translation but deletion of DB2 has little effect. Deleting both DB1 and DB2 reduced

Subgenomic ''flavivirus'' RNA (sfRNA) is an extension of the 3' UTR and has been demonstrated to play a role in ''flavivirus'' replication and pathogenesis. sfRNA is produced by incomplete degradation of genomic viral RNA by the host cells 5'-3' exoribonuclease 1 (XRN1). As the XRN1 degrades viral RNA, it stalls at stemloops formed by the secondary structure of the 5' and 3' UTR. This pause results in an undigested fragment of genome RNA known as sfRNA. sfRNA influences the life cycle of the ''flavivirus'' in a concentration dependent manner. Accumulation of sfRNA causes (1) antagonization of the cell's innate immune response, thus decreasing host defense against the virus (2) inhibition of XRN1 and Dicer activity to modify RNAi pathways that destroy viral RNA (3) modification of the viral replication complex to increase viral reproduction. Overall, sfRNA is implied in multiple pathways that compromise host defenses and promote infection by flaviviruses.

Subgenomic ''flavivirus'' RNA (sfRNA) is an extension of the 3' UTR and has been demonstrated to play a role in ''flavivirus'' replication and pathogenesis. sfRNA is produced by incomplete degradation of genomic viral RNA by the host cells 5'-3' exoribonuclease 1 (XRN1). As the XRN1 degrades viral RNA, it stalls at stemloops formed by the secondary structure of the 5' and 3' UTR. This pause results in an undigested fragment of genome RNA known as sfRNA. sfRNA influences the life cycle of the ''flavivirus'' in a concentration dependent manner. Accumulation of sfRNA causes (1) antagonization of the cell's innate immune response, thus decreasing host defense against the virus (2) inhibition of XRN1 and Dicer activity to modify RNAi pathways that destroy viral RNA (3) modification of the viral replication complex to increase viral reproduction. Overall, sfRNA is implied in multiple pathways that compromise host defenses and promote infection by flaviviruses.

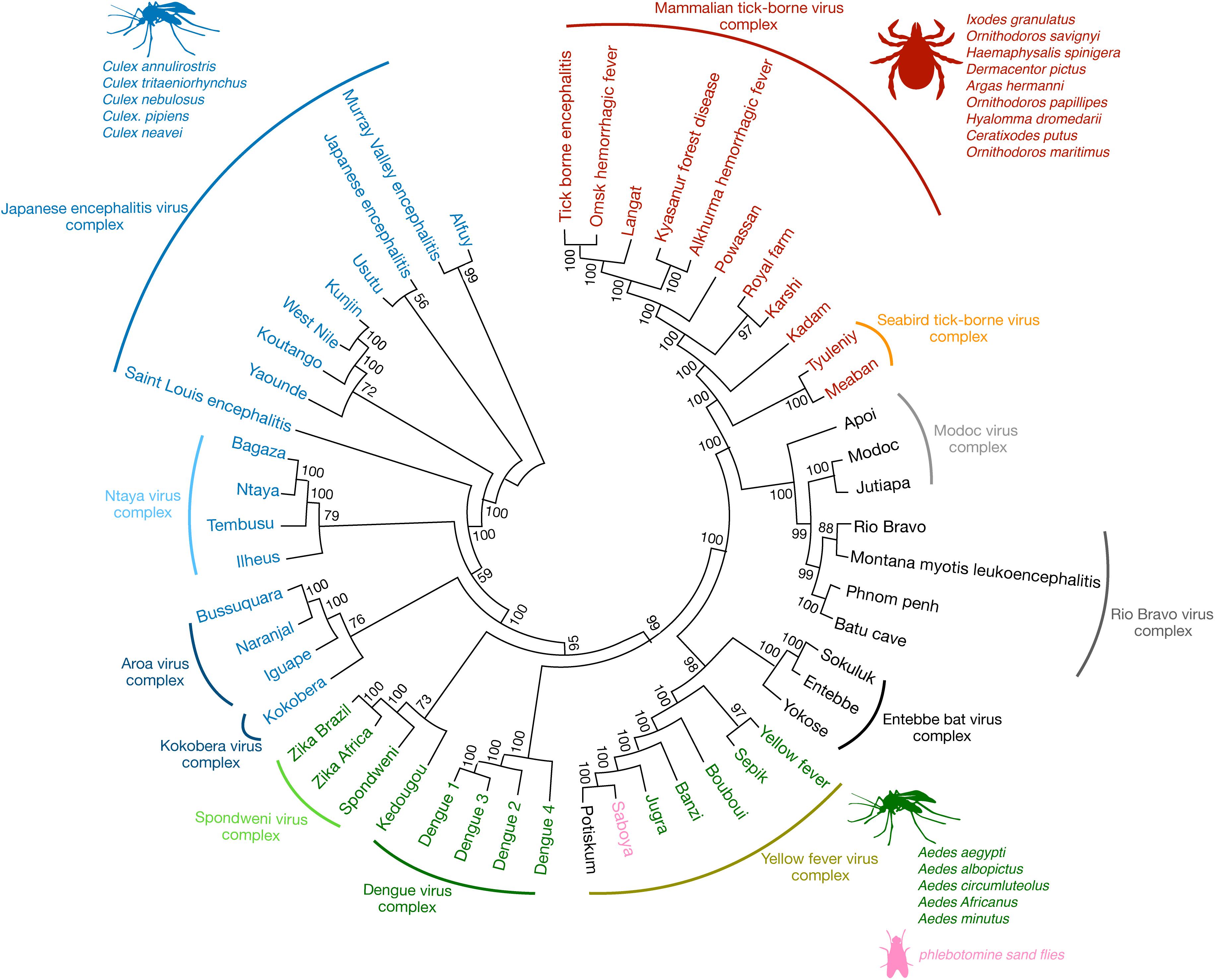

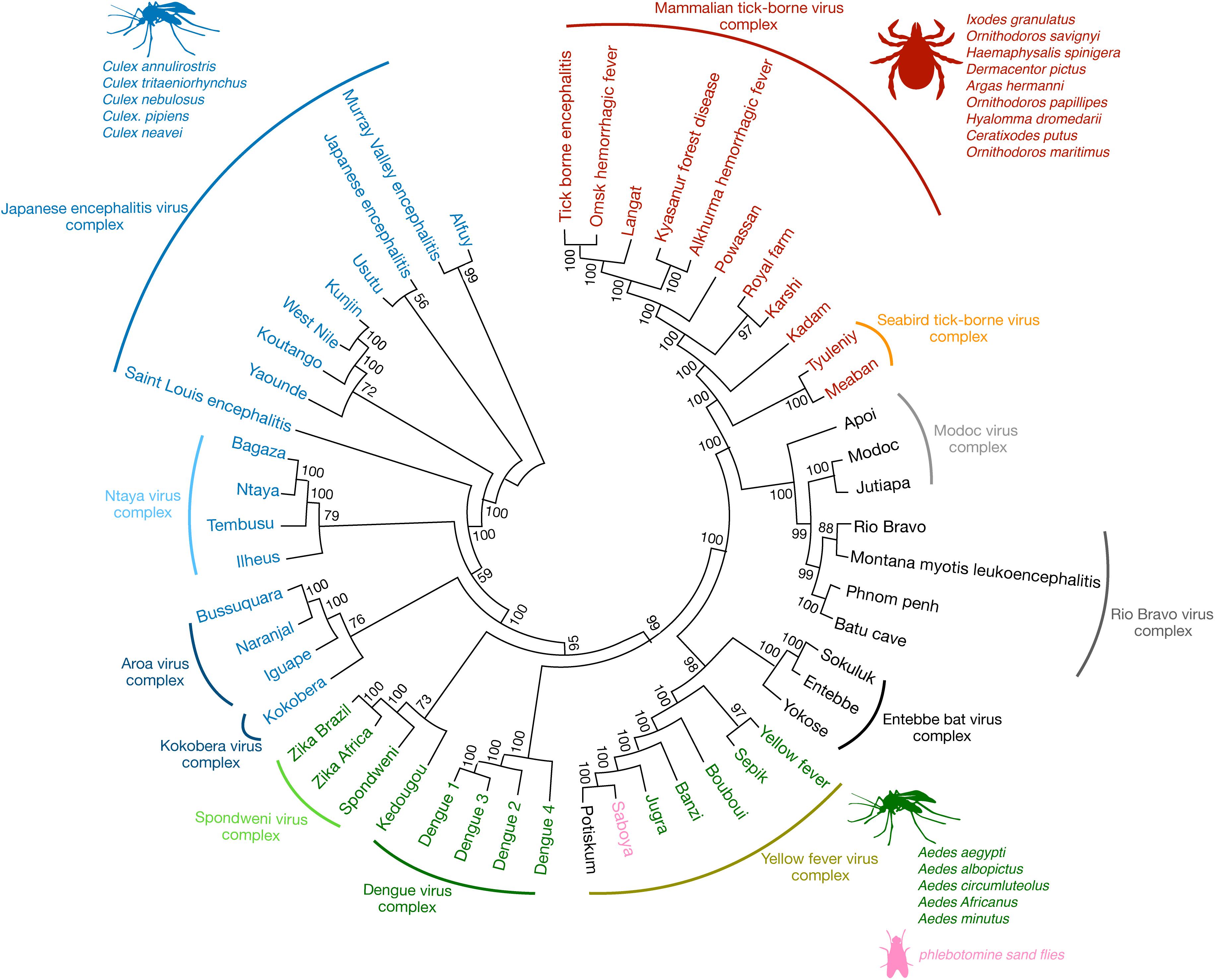

The flaviviruses can be divided into two clades: one with vector-borne viruses and the other with no known vector. The vector clade, in turn, can be subdivided into a mosquito-borne clade and a tick-borne clade. These groups can be divided again.

The mosquito group can be divided into two branches: one branch contains neurotropic viruses, often associated with encephalitic disease in humans or livestock. This branch tends to be spread by ''

The flaviviruses can be divided into two clades: one with vector-borne viruses and the other with no known vector. The vector clade, in turn, can be subdivided into a mosquito-borne clade and a tick-borne clade. These groups can be divided again.

The mosquito group can be divided into two branches: one branch contains neurotropic viruses, often associated with encephalitic disease in humans or livestock. This branch tends to be spread by '' Estimates of divergence times have been made for several of these viruses. The origin of these viruses appears to be at least 9400 to 14,000 years ago. The Old World and New World dengue strains diverged between 150 and 450 years ago. The European and Far Eastern tick-borne encephalitis strains diverged about 1087 (1610–649) years ago. European tick-borne encephalitis and louping ill viruses diverged about 572 (844–328) years ago. This latter estimate is consistent with historical records. ''Kunjin virus'' diverged from ''West Nile virus'' approximately 277 (475–137) years ago. This time corresponds to the settlement of Australia from Europe. The Japanese encephalitis group appears to have evolved in Africa 2000–3000 years ago and then spread initially to South East Asia before migrating to the rest of Asia.

Estimates of divergence times have been made for several of these viruses. The origin of these viruses appears to be at least 9400 to 14,000 years ago. The Old World and New World dengue strains diverged between 150 and 450 years ago. The European and Far Eastern tick-borne encephalitis strains diverged about 1087 (1610–649) years ago. European tick-borne encephalitis and louping ill viruses diverged about 572 (844–328) years ago. This latter estimate is consistent with historical records. ''Kunjin virus'' diverged from ''West Nile virus'' approximately 277 (475–137) years ago. This time corresponds to the settlement of Australia from Europe. The Japanese encephalitis group appears to have evolved in Africa 2000–3000 years ago and then spread initially to South East Asia before migrating to the rest of Asia.

The very successful yellow fever 17D vaccine, introduced in 1937, produced dramatic reductions in epidemic activity.

Effective inactivated

The very successful yellow fever 17D vaccine, introduced in 1937, produced dramatic reductions in epidemic activity.

Effective inactivated

MicrobiologyBytes: FlavivirusesNovartis Institute for Tropical Diseases (NITD)

– Dengue Fever research at the Novartis Institute for Tropical Diseases (NITD)

Dengueinfo.org

– Depository of dengue virus genomic sequence data

Virus Pathogen Database and Analysis Resource (ViPR): FlaviviridaeRfam entry for Flavivirus 3'UTR stem loop IVRfam entry for Flavivirus DB elementRfam entry for Flavivirus 3' UTR cis-acting replication element (CRE)Rfam entry for the Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) hairpin structure

{{Authority control Rodent-carried diseases Flaviviridae Virus genera

positive-strand RNA virus

Positive-strand RNA viruses (+ssRNA viruses) are a group of related viruses that have positive-sense, single-stranded genomes made of ribonucleic acid. The positive-sense genome can act as messenger RNA (mRNA) and can be directly translated int ...

es in the family ''Flaviviridae

''Flaviviridae'' is a family of enveloped positive-strand RNA viruses which mainly infect mammals and birds. They are primarily spread through arthropod vectors (mainly ticks and mosquitoes). The family gets its name from the yellow fever virus ...

''. The genus includes the West Nile virus

West Nile virus (WNV) is a single-stranded RNA virus that causes West Nile fever. It is a member of the family ''Flaviviridae'', from the genus ''Flavivirus'', which also contains the Zika virus, dengue virus, and yellow fever virus. The virus ...

, dengue virus

''Dengue virus'' (DENV) is the cause of dengue fever. It is a mosquito-borne, single positive-stranded RNA virus of the family ''Flaviviridae''; genus ''Flavivirus''. Four serotypes of the virus have been found, a reported fifth has yet to be co ...

, tick-borne encephalitis virus

Tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) is a positive-strand RNA virus associated with tick-borne encephalitis in the genus '' Flavivirus''.

Classification

Taxonomy

TBEV is a member of the genus '' Flavivirus''. Other close relatives, members ...

, yellow fever virus

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. In ...

, Zika virus

''Zika virus'' (ZIKV; pronounced or ) is a member of the virus family ''Flaviviridae''. It is spread by daytime-active ''Aedes'' mosquitoes, such as '' A. aegypti'' and '' A. albopictus''. Its name comes from the Ziika Forest of Uganda, whe ...

and several other virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1 ...

es which may cause encephalitis

Encephalitis is inflammation of the brain. The severity can be variable with symptoms including reduction or alteration in consciousness, headache, fever, confusion, a stiff neck, and vomiting. Complications may include seizures, hallucinations, ...

, as well as insect-specific flaviviruses (ISFs) such as cell fusing agent virus (CFAV), Palm Creek virus

Palm Creek virus (PCV) is an insect virus belonging to the genus '' Flavivirus'', of the family ''Flaviviridae''. It was discovered in 2013 from the mosquito '' Coquillettidia xanthogaster''. The female mosquitoes were originally collected in 201 ...

(PCV), and Parramatta River virus

Parramatta River virus (PaRV) is an insect virus belonging to ''Flaviviridae'' and endemic to Australia. It was discovered in 2015. The virus was identified from the mosquito '' Aedes vigilax'' collected from Sydney under the joint research projec ...

(PaRV). While dual-host flaviviruses can infect vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () ( chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, ...

s as well as arthropods, insect-specific flaviviruses are restricted to their competent arthropods. The means by which flaviviruses establish persistent infection in their competent vectors and cause disease in humans depends upon several virus-host interactions, including the intricate interplay between flavivirus-encoded immune antagonists and the host antiviral innate immune effector molecules.

Flaviviruses are named for the yellow fever virus; the word ''flavus'' means 'yellow' in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, and yellow fever in turn is named from its propensity to cause yellow jaundice

Jaundice, also known as icterus, is a yellowish or greenish pigmentation of the skin and sclera due to high bilirubin levels. Jaundice in adults is typically a sign indicating the presence of underlying diseases involving abnormal heme meta ...

in victims.

Flaviviruses share several common aspects: common size (40–65 nm), symmetry ( enveloped, icosahedral

In geometry, an icosahedron ( or ) is a polyhedron with 20 faces. The name comes and . The plural can be either "icosahedra" () or "icosahedrons".

There are infinitely many non- similar shapes of icosahedra, some of them being more symmetrica ...

nucleocapsid

A capsid is the protein shell of a virus, enclosing its genetic material. It consists of several oligomeric (repeating) structural subunits made of protein called protomers. The observable 3-dimensional morphological subunits, which may or may ...

), nucleic acid

Nucleic acids are biopolymers, macromolecules, essential to all known forms of life. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomers made of three components: a 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main cl ...

(positive-sense

In molecular biology and genetics, the sense of a nucleic acid molecule, particularly of a strand of DNA or RNA, refers to the nature of the roles of the strand and its complement in specifying a sequence of amino acids. Depending on the context ...

, single-stranded RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

around 10,000–11,000 bases), and appearance under the electron microscope

An electron microscope is a microscope that uses a beam of accelerated electrons as a source of illumination. As the wavelength of an electron can be up to 100,000 times shorter than that of visible light photons, electron microscopes have a hi ...

.

Most of these viruses are primarily transmitted by the bite from an infected arthropod

Arthropods (, (gen. ποδός)) are invertebrate animals with an exoskeleton, a Segmentation (biology), segmented body, and paired jointed appendages. Arthropods form the phylum Arthropoda. They are distinguished by their jointed limbs and Arth ...

(mosquito or tick), and hence are classified as arboviruses

Arbovirus is an informal name for any virus that is transmitted by arthropod vectors. The term ''arbovirus'' is a portmanteau word (''ar''thropod-''bo''rne ''virus''). ''Tibovirus'' (''ti''ck-''bo''rne ''virus'') is sometimes used to more sp ...

. Human infections with most of these arboviruses are incidental, as humans are unable to replicate the virus to high enough titer

Titer (American English) or titre (British English) is a way of expressing concentration. Titer testing employs serial dilution to obtain approximate quantitative information from an analytical procedure that inherently only evaluates as positiv ...

s to reinfect the arthropods needed to continue the virus life-cycle – humans are then a dead end host. The exceptions to this are the ''yellow fever virus'', ''dengue virus

''Dengue virus'' (DENV) is the cause of dengue fever. It is a mosquito-borne, single positive-stranded RNA virus of the family ''Flaviviridae''; genus ''Flavivirus''. Four serotypes of the virus have been found, a reported fifth has yet to be co ...

'' and ''zika virus

''Zika virus'' (ZIKV; pronounced or ) is a member of the virus family ''Flaviviridae''. It is spread by daytime-active ''Aedes'' mosquitoes, such as '' A. aegypti'' and '' A. albopictus''. Its name comes from the Ziika Forest of Uganda, whe ...

''. These three viruses still require mosquito vectors but are well-enough adapted to humans as to not necessarily depend upon animal hosts (although they continue to have important animal transmission routes, as well).

Other virus transmission routes for arboviruses include handling infected animal carcasses, blood transfusion, sex, child birth and consumption of unpasteurised milk products. Transmission from nonhuman vertebrates to humans without an intermediate vector arthropod however mostly occurs with low probability. For example, early tests with yellow fever showed that the disease is not contagious

Contagious may refer to:

* Contagious disease

Literature

* Contagious (magazine), a marketing publication

* ''Contagious'' (novel), a science fiction thriller novel by Scott Sigler

Music

Albums

*''Contagious'' (Peggy Scott-Adams album), 1997

* ...

.

The known non-arboviruses of the ''flavivirus'' family reproduce in either arthropods or vertebrates, but not both, with one odd member of the genus affecting a nematode

The nematodes ( or grc-gre, Νηματώδη; la, Nematoda) or roundworms constitute the phylum Nematoda (also called Nemathelminthes), with plant-Parasitism, parasitic nematodes also known as eelworms. They are a diverse animal phylum inhab ...

.

Structure

Flaviviruses are enveloped and spherical and have icosahedral geometries with a pseudo T=3 symmetry. The virus particle diameter is around 50 nm.

Flaviviruses are enveloped and spherical and have icosahedral geometries with a pseudo T=3 symmetry. The virus particle diameter is around 50 nm.

Genome

Flaviviruses havepositive-sense

In molecular biology and genetics, the sense of a nucleic acid molecule, particularly of a strand of DNA or RNA, refers to the nature of the roles of the strand and its complement in specifying a sequence of amino acids. Depending on the context ...

, single-stranded RNA genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ge ...

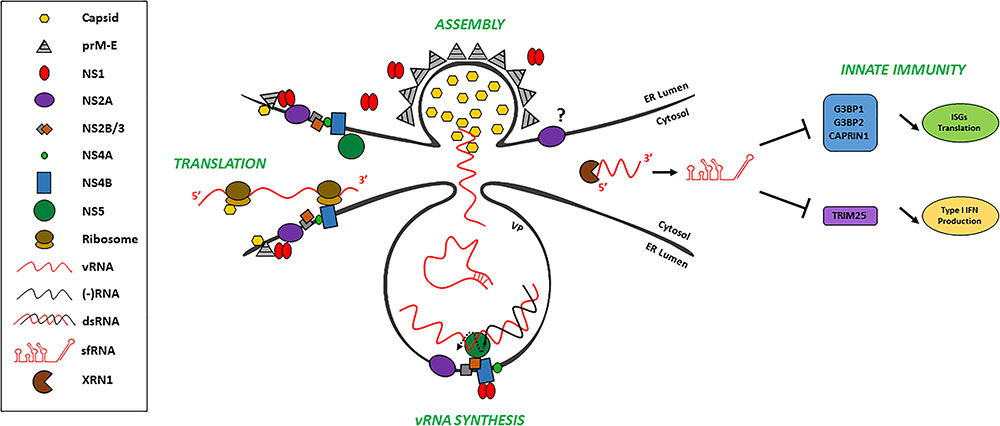

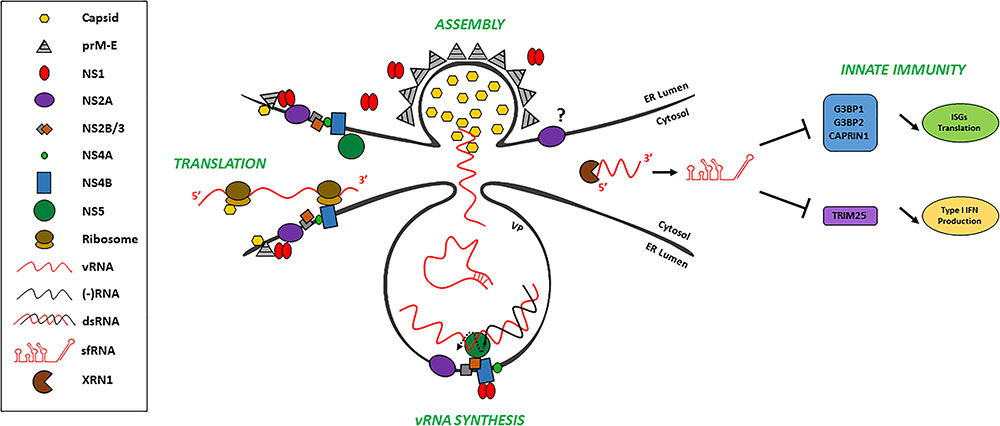

s which are non-segmented and around 10–11 kbp in length. In general, the genome encodes three structural proteins (Capsid, prM, and Envelope) and seven non-structural proteins (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5). The genomic RNA is modified at the 5′ end of positive-strand genomic RNA with a cap-1 structure (me7-GpppA-me2).

Life cycle

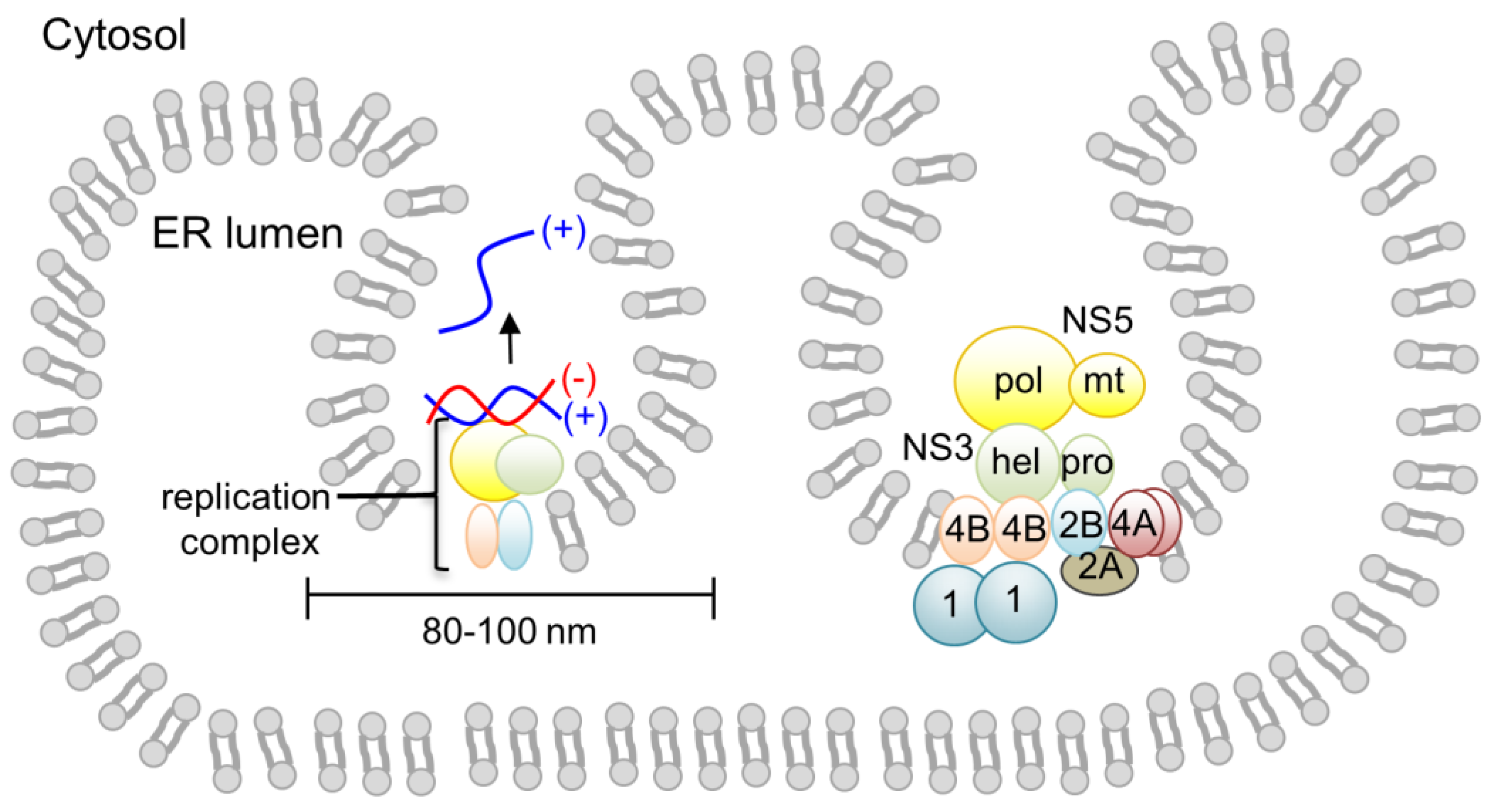

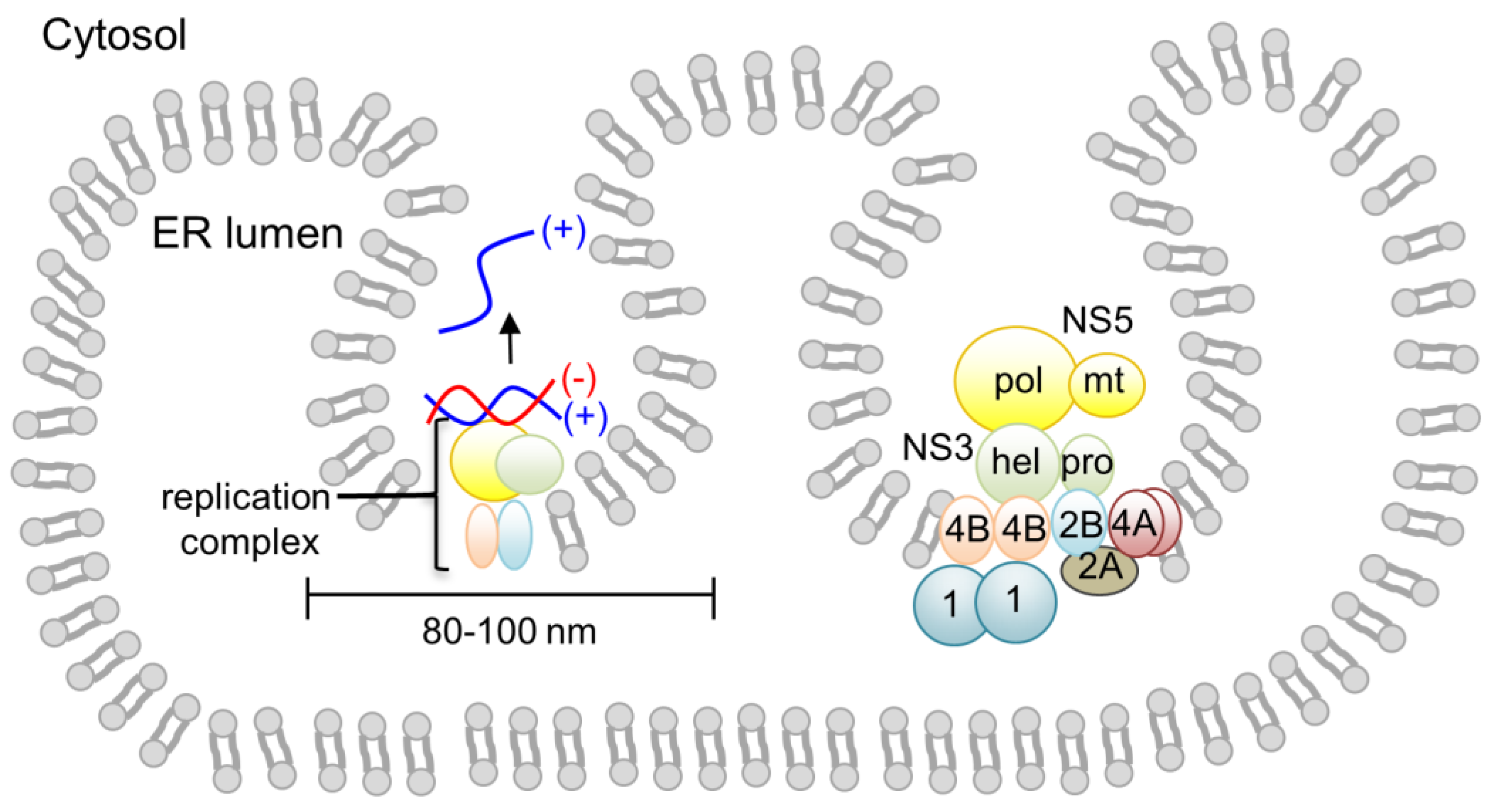

Flaviviruses replicate in the

Flaviviruses replicate in the cytoplasm

In cell biology, the cytoplasm is all of the material within a eukaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, except for the cell nucleus. The material inside the nucleus and contained within the nuclear membrane is termed the nucleoplasm. The ...

of the host cells. The genome mimics the cellular mRNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of Protein biosynthesis, synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is ...

molecule in all aspects except for the absence of the poly-adenylated (poly-A) tail. This feature allows the virus to exploit cellular apparatuses to synthesize both structural and non-structural proteins, during replication. The cellular ribosome

Ribosomes ( ) are macromolecular machines, found within all cells, that perform biological protein synthesis (mRNA translation). Ribosomes link amino acids together in the order specified by the codons of messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules to ...

is crucial to the replication of the flavivirus, as it translates the RNA, in a similar fashion to cellular mRNA, resulting in the synthesis of a single polyprotein

Proteolysis is the breakdown of proteins into smaller polypeptides or amino acids. Uncatalysed, the hydrolysis of peptide bonds is extremely slow, taking hundreds of years. Proteolysis is typically catalysed by cellular enzymes called protease ...

.

Cellular RNA cap structures are formed via the action of an RNA triphosphatase

The enzyme polynucleotide 5′-phosphatase (RNA 5′-triphosphatase, RTPase, EC 3.1.3.33) is an enzyme that catalyzes the reaction

:a 5′-phosphopolynucleotide + H2O \rightleftharpoons a polynucleotide + phosphate

This enzyme belongs to the fam ...

, with guanylyltransferase Guanylyl transferases are enzymes that transfer a guanosine mono phosphate group, usually from GTP to another molecule, releasing pyrophosphate. Many eukaryotic guanylyl transferases are capping enzymes that catalyze the formation of the 5' cap in ...

, N7-methyltransferase

Methyltransferases are a large group of enzymes that all methylate their substrates but can be split into several subclasses based on their structural features. The most common class of methyltransferases is class I, all of which contain a Ross ...

and 2′-O methyltransferase. The virus encodes these activities in its non-structural proteins. The NS3 protein encodes a RNA triphosphatase

The enzyme polynucleotide 5′-phosphatase (RNA 5′-triphosphatase, RTPase, EC 3.1.3.33) is an enzyme that catalyzes the reaction

:a 5′-phosphopolynucleotide + H2O \rightleftharpoons a polynucleotide + phosphate

This enzyme belongs to the fam ...

within its helicase

Helicases are a class of enzymes thought to be vital to all organisms. Their main function is to unpack an organism's genetic material. Helicases are motor proteins that move directionally along a nucleic acid phosphodiester backbone, separatin ...

domain. It uses the helicase ATP hydrolysis site to remove the γ-phosphate from the 5′ end of the RNA. The N-terminal domain of the non-structural protein 5 (NS5) has both the N7-methyltransferase and guanylyltransferase activities necessary for forming mature RNA cap structures. RNA binding affinity is reduced by the presence of ATP or GTP and enhanced by S-adenosyl methionine

''S''-Adenosyl methionine (SAM), also known under the commercial names of SAMe, SAM-e, or AdoMet, is a common cosubstrate involved in methyl group transfers, transsulfuration, and aminopropylation. Although these anabolic reactions occur throug ...

. This protein also encodes a 2′-O methyltransferase.

Once

Once translated

Translation is the communication of the meaning of a source-language text by means of an equivalent target-language text. The English language draws a terminological distinction (which does not exist in every language) between ''transla ...

, the polyprotein is cleaved by a combination of viral and host protease

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalyzes (increases reaction rate or "speeds up") proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the ...

s to release mature polypeptide

Peptides (, ) are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. Long chains of amino acids are called proteins. Chains of fewer than twenty amino acids are called oligopeptides, and include dipeptides, tripeptides, and tetrapeptides.

A p ...

products. Nevertheless, cellular post-translational modification is dependent on the presence of a poly-A tail; therefore this process is not host-dependent. Instead, the poly-protein contains an autocatalytic

A single chemical reaction is said to be autocatalytic if one of the reaction products is also a catalyst for the same or a coupled reaction.Steinfeld J.I., Francisco J.S. and Hase W.L. ''Chemical Kinetics and Dynamics'' (2nd ed., Prentice-Hall 199 ...

feature which automatically releases the first peptide, a virus specific enzyme. This enzyme is then able to cleave the remaining poly-protein into the individual products. One of the products cleaved is a RNA-dependent RNA polymerase

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) or RNA replicase is an enzyme that catalyzes the replication of RNA from an RNA template. Specifically, it catalyzes synthesis of the RNA strand complementary to a given RNA template. This is in contrast to t ...

, responsible for the synthesis of a negative-sense RNA molecule. Consequently, this molecule acts as the template for the synthesis of the genomic progeny RNA.

''Flavivirus'' genomic RNA replication occurs on rough endoplasmic reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is, in essence, the transportation system of the eukaryotic cell, and has many other important functions such as protein folding. It is a type of organelle made up of two subunits – rough endoplasmic reticulum ( ...

membranes in membranous compartments. New viral particles are subsequently assembled. This occurs during the budding

Budding or blastogenesis is a type of asexual reproduction in which a new organism develops from an outgrowth or bud due to cell division at one particular site. For example, the small bulb-like projection coming out from the yeast cell is know ...

process which is also responsible for the accumulation of the envelope and cell lysis

Lysis ( ) is the breaking down of the membrane of a cell, often by viral, enzymic, or osmotic (that is, "lytic" ) mechanisms that compromise its integrity. A fluid containing the contents of lysed cells is called a ''lysate''. In molecular bio ...

.

A G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (also known as ADRBK1) appears to be important in entry and replication for several viruses in ''Flaviviridae''.

Humans, mammals, mosquitoes, and ticks serve as the natural host. Transmission routes are zoonosis

A zoonosis (; plural zoonoses) or zoonotic disease is an infectious disease of humans caused by a pathogen (an infectious agent, such as a bacterium, virus, parasite or prion) that has jumped from a non-human (usually a vertebrate) to a human. ...

and bite.

RNA secondary structure elements

The positive sense RNA genome of ''Flavivirus'' contains 5' and 3'

The positive sense RNA genome of ''Flavivirus'' contains 5' and 3' untranslated region

In molecular genetics, an untranslated region (or UTR) refers to either of two sections, one on each side of a coding sequence on a strand of mRNA. If it is found on the 5' side, it is called the 5' UTR (or leader sequence), or if it is foun ...

s (UTRs).

5'UTR

The 5'UTRs are 95–101 nucleotides long in ''Dengue virus

''Dengue virus'' (DENV) is the cause of dengue fever. It is a mosquito-borne, single positive-stranded RNA virus of the family ''Flaviviridae''; genus ''Flavivirus''. Four serotypes of the virus have been found, a reported fifth has yet to be co ...

''. There are two conserved structural elements in the ''Flavivirus'' 5'UTR, a large stem loop (SLA) and a short stem loop (SLB). SLA folds into a Y-shaped structure with a side stem loop and a small top loop. SLA is likely to act as a promoter, and is essential for viral RNA synthesis. SLB is involved in interactions between the 5'UTR and 3'UTR which result in the cyclisation of the viral RNA, which is essential for viral replication.

3'UTR

The 3'UTRs are typically 0.3–0.5 kb in length and contain a number of highly conserved

The 3'UTRs are typically 0.3–0.5 kb in length and contain a number of highly conserved secondary structure

Protein secondary structure is the three dimensional conformational isomerism, form of ''local segments'' of proteins. The two most common Protein structure#Secondary structure, secondary structural elements are alpha helix, alpha helices and beta ...

s which are conserved and restricted to the ''flavivirus'' family. The majority of analysis has been carried out using ''West Nile virus

West Nile virus (WNV) is a single-stranded RNA virus that causes West Nile fever. It is a member of the family ''Flaviviridae'', from the genus ''Flavivirus'', which also contains the Zika virus, dengue virus, and yellow fever virus. The virus ...

'' (WNV) to study the function the 3'UTR.

Currently 8 secondary structures have been identified within the 3'UTR of WNV and are (in the order in which they are found with the 3'UTR) SL-I, SL-II, SL-III, SL-IV, DB1, DB2 and CRE. Some of these secondary structures have been characterised and are important in facilitating viral replication

Viral replication is the formation of biological viruses during the infection process in the target host cells. Viruses must first get into the cell before viral replication can occur. Through the generation of abundant copies of its genome an ...

and protecting the 3'UTR from 5' endonuclease

Endonucleases are enzymes that cleave the phosphodiester bond within a polynucleotide chain. Some, such as deoxyribonuclease I, cut DNA relatively nonspecifically (without regard to sequence), while many, typically called restriction endonucleases ...

digestion. Nuclease resistance protects the downstream 3' UTR RNA fragment from degradation and is essential for virus-induced cytopathicity and pathogenicity.

* SL-II

SL-II has been suggested to contribute to nuclease resistance. It may be related to another hairpin loop

Stem-loop intramolecular base pairing is a pattern that can occur in single-stranded RNA. The structure is also known as a hairpin or hairpin loop. It occurs when two regions of the same strand, usually complementary in nucleotide sequence wh ...

identified in the 5'UTR of the ''Japanese encephalitis virus

Japanese encephalitis (JE) is an infection of the brain caused by the Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV). While most infections result in little or no symptoms, occasional inflammation of the brain occurs. In these cases, symptoms may include he ...

'' (JEV) genome. The JEV hairpin is significantly over-represented upon host cell infection and it has been suggested that the hairpin structure may play a role in regulating RNA synthesis.

*SL-IV

This secondary structure is located within the 3'UTR of the genome of ''Flavivirus'' upstream of the DB elements. The function of this conserved structure is unknown but is thought to contribute to ribonuclease resistance.

* DB1/DB2

These two conserved secondary structures are also known as pseudo-repeat elements. They were originally identified within the genome of ''Dengue virus'' and are found adjacent to each other within the 3'UTR. They appear to be widely conserved across the Flaviviradae. These DB elements have a secondary structure consisting of three helices and they play a role in ensuring efficient translation. Deletion of DB1 has a small but significant reduction in translation but deletion of DB2 has little effect. Deleting both DB1 and DB2 reduced

These two conserved secondary structures are also known as pseudo-repeat elements. They were originally identified within the genome of ''Dengue virus'' and are found adjacent to each other within the 3'UTR. They appear to be widely conserved across the Flaviviradae. These DB elements have a secondary structure consisting of three helices and they play a role in ensuring efficient translation. Deletion of DB1 has a small but significant reduction in translation but deletion of DB2 has little effect. Deleting both DB1 and DB2 reduced translation

Translation is the communication of the Meaning (linguistic), meaning of a #Source and target languages, source-language text by means of an Dynamic and formal equivalence, equivalent #Source and target languages, target-language text. The ...

efficiency of the viral genome to 25%.

*CRE

CRE is the Cis-acting replication element, also known as the 3'SL RNA elements, and is thought to be essential in viral replication by facilitating the formation of a "replication complex". Although evidence has been presented for an existence of a pseudoknot

__NOTOC__

A pseudoknot is a nucleic acid secondary structure containing at least two stem-loop structures in which half of one stem is intercalated between the two halves of another stem. The pseudoknot was first recognized in the turnip yellow ...

structure in this RNA, it does not appear to be well conserved across flaviviruses. Deletions of the 3' UTR of flaviviruses have been shown to be lethal for infectious clones.

Conserved hairpin cHP

A conserved hairpin (cHP) structure was later found in several ''Flavivirus''genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ge ...

s and is thought to direct translation of capsid proteins. It is located just downstream of the AUG start codon

The start codon is the first codon of a messenger RNA (mRNA) transcript translated by a ribosome. The start codon always codes for methionine in eukaryotes and Archaea and a N-formylmethionine (fMet) in bacteria, mitochondria and plastids. The ...

.

The role of RNA secondary structures in sfRNA production

Subgenomic ''flavivirus'' RNA (sfRNA) is an extension of the 3' UTR and has been demonstrated to play a role in ''flavivirus'' replication and pathogenesis. sfRNA is produced by incomplete degradation of genomic viral RNA by the host cells 5'-3' exoribonuclease 1 (XRN1). As the XRN1 degrades viral RNA, it stalls at stemloops formed by the secondary structure of the 5' and 3' UTR. This pause results in an undigested fragment of genome RNA known as sfRNA. sfRNA influences the life cycle of the ''flavivirus'' in a concentration dependent manner. Accumulation of sfRNA causes (1) antagonization of the cell's innate immune response, thus decreasing host defense against the virus (2) inhibition of XRN1 and Dicer activity to modify RNAi pathways that destroy viral RNA (3) modification of the viral replication complex to increase viral reproduction. Overall, sfRNA is implied in multiple pathways that compromise host defenses and promote infection by flaviviruses.

Subgenomic ''flavivirus'' RNA (sfRNA) is an extension of the 3' UTR and has been demonstrated to play a role in ''flavivirus'' replication and pathogenesis. sfRNA is produced by incomplete degradation of genomic viral RNA by the host cells 5'-3' exoribonuclease 1 (XRN1). As the XRN1 degrades viral RNA, it stalls at stemloops formed by the secondary structure of the 5' and 3' UTR. This pause results in an undigested fragment of genome RNA known as sfRNA. sfRNA influences the life cycle of the ''flavivirus'' in a concentration dependent manner. Accumulation of sfRNA causes (1) antagonization of the cell's innate immune response, thus decreasing host defense against the virus (2) inhibition of XRN1 and Dicer activity to modify RNAi pathways that destroy viral RNA (3) modification of the viral replication complex to increase viral reproduction. Overall, sfRNA is implied in multiple pathways that compromise host defenses and promote infection by flaviviruses.

Evolution

The flaviviruses can be divided into two clades: one with vector-borne viruses and the other with no known vector. The vector clade, in turn, can be subdivided into a mosquito-borne clade and a tick-borne clade. These groups can be divided again.

The mosquito group can be divided into two branches: one branch contains neurotropic viruses, often associated with encephalitic disease in humans or livestock. This branch tends to be spread by ''

The flaviviruses can be divided into two clades: one with vector-borne viruses and the other with no known vector. The vector clade, in turn, can be subdivided into a mosquito-borne clade and a tick-borne clade. These groups can be divided again.

The mosquito group can be divided into two branches: one branch contains neurotropic viruses, often associated with encephalitic disease in humans or livestock. This branch tends to be spread by ''Culex

''Culex'' is a genus of mosquitoes, several species of which serve as vectors of one or more important diseases of birds, humans, and other animals. The diseases they vector include arbovirus infections such as West Nile virus, Japanese encep ...

'' species and to have bird reservoirs. The second branch is the non-neurotropic viruses associated with human haemorrhagic disease. These tend to have ''Aedes

''Aedes'' is a genus of mosquitoes originally found in tropical and subtropical zones, but now found on all continents except perhaps Antarctica. Some species have been spread by human activity: ''Aedes albopictus'', a particularly invasive spe ...

'' species as vectors and primate

Primates are a diverse order of mammals. They are divided into the strepsirrhines, which include the lemurs, galagos, and lorisids, and the haplorhines, which include the tarsiers and the simians (monkeys and apes, the latter including huma ...

hosts.

The tick-borne viruses also form two distinct groups: one is associated with seabird

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adapted to life within the marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent evolution, as the same enviro ...

s and the other – the tick-borne encephalitis complex viruses – is associated primarily with rodent

Rodents (from Latin , 'to gnaw') are mammals of the order Rodentia (), which are characterized by a single pair of continuously growing incisors in each of the upper and lower jaws. About 40% of all mammal species are rodents. They are na ...

s.

The viruses that lack a known vector can be divided into three groups: one closely related to the mosquito-borne viruses, which is associated with bat

Bats are mammals of the order Chiroptera.''cheir'', "hand" and πτερόν''pteron'', "wing". With their forelimbs adapted as wings, they are the only mammals capable of true and sustained flight. Bats are more agile in flight than most ...

s; a second, genetically more distant, is also associated with bats; and a third group is associated with rodents.

Evolutionary relationships between endogenised viral elements of Flaviviruses and contemporary flaviviruses using maximum likelihood approaches have identified that arthropod-vectored flaviviruses likely emerged from an arachnid source. This contradicts earlier work with a smaller number of extant viruses showing that the tick-borne viruses emerged from a mosquito-borne group.

Several partial and complete genomes of flaviviruses have been found in aquatic invertebrates such as the sea spider

Sea spiders are marine arthropods of the order Pantopoda ( ‘all feet’), belonging to the class Pycnogonida, hence they are also called pycnogonids (; named after ''Pycnogonum'', the type genus; with the suffix '). They are cosmopolitan, fou ...

''Endeis spinosa'' and several crustaceans and cephalopods. These sequences appear to be related to those in the insect-specific flaviviruses and also the Tamana bat virus groupings. While it is not presently clear how aquatic flaviviruses fit into the evolution of this group of viruses, there is some evidence that one of these viruses, Wenzhou shark flavivirus, infects both a crustacean (''Portunus trituberculatus'') Pacific spadenose shark (''Scoliodon macrorhynchos'') shark host, indicating an aquatic arbovirus life cycle.

Estimates of divergence times have been made for several of these viruses. The origin of these viruses appears to be at least 9400 to 14,000 years ago. The Old World and New World dengue strains diverged between 150 and 450 years ago. The European and Far Eastern tick-borne encephalitis strains diverged about 1087 (1610–649) years ago. European tick-borne encephalitis and louping ill viruses diverged about 572 (844–328) years ago. This latter estimate is consistent with historical records. ''Kunjin virus'' diverged from ''West Nile virus'' approximately 277 (475–137) years ago. This time corresponds to the settlement of Australia from Europe. The Japanese encephalitis group appears to have evolved in Africa 2000–3000 years ago and then spread initially to South East Asia before migrating to the rest of Asia.

Estimates of divergence times have been made for several of these viruses. The origin of these viruses appears to be at least 9400 to 14,000 years ago. The Old World and New World dengue strains diverged between 150 and 450 years ago. The European and Far Eastern tick-borne encephalitis strains diverged about 1087 (1610–649) years ago. European tick-borne encephalitis and louping ill viruses diverged about 572 (844–328) years ago. This latter estimate is consistent with historical records. ''Kunjin virus'' diverged from ''West Nile virus'' approximately 277 (475–137) years ago. This time corresponds to the settlement of Australia from Europe. The Japanese encephalitis group appears to have evolved in Africa 2000–3000 years ago and then spread initially to South East Asia before migrating to the rest of Asia.

Phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek φυλή/ φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups o ...

studies of the ''West Nile virus'' has shown that it emerged as a distinct virus around 1000 years ago. This initial virus developed into two distinct lineages, lineage 1 and its multiple profiles is the source of the epidemic transmission in Africa and throughout the world. Lineage 2 was considered an Africa zoonosis

A zoonosis (; plural zoonoses) or zoonotic disease is an infectious disease of humans caused by a pathogen (an infectious agent, such as a bacterium, virus, parasite or prion) that has jumped from a non-human (usually a vertebrate) to a human. ...

. However, in 2008, lineage 2, previously only seen in horses in sub-Saharan Africa and Madagascar, began to appear in horses in Europe, where the first known outbreak affected 18 animals in Hungary in 2008. Lineage 1 ''West Nile virus'' was detected in South Africa in 2010 in a mare

A mare is an adult female horse or other equine. In most cases, a mare is a female horse over the age of three, and a filly is a female horse three and younger. In Thoroughbred horse racing, a mare is defined as a female horse more than four ...

and her aborted fetus

A fetus or foetus (; plural fetuses, feti, foetuses, or foeti) is the unborn offspring that develops from an animal embryo. Following embryonic development the fetal stage of development takes place. In human prenatal development, fetal deve ...

; previously, only lineage 2 ''West Nile virus'' had been detected in horses and humans in South Africa. A 2007 fatal case in a killer whale

The orca or killer whale (''Orcinus orca'') is a toothed whale belonging to the oceanic dolphin family, of which it is the largest member. It is the only extant species in the genus ''Orcinus'' and is recognizable by its black-and-white pa ...

in Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

broadened the known host range

In biology and medicine, a host is a larger organism that harbours a smaller organism; whether a parasitic, a mutualistic, or a commensalist ''guest'' (symbiont). The guest is typically provided with nourishment and shelter. Examples include a ...

of ''West Nile virus'' to include cetacean

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals that includes whales, dolphins, and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively carnivorous diet. They propel them ...

s.

''Omsk haemorrhagic fever virus'' appears to have evolved within the last 1000 years. The viral genomes can be divided into 2 clades — A and B. Clade A has five genotypes, and clade B has one. These clades separated about 700 years ago. This separation appears to have occurred in the Kurgan province. Clade A subsequently underwent division into clade C, D and E 230 years ago. Clade C and E appear to have originated in the Novosibirsk and Omsk Provinces, respectively. The muskrat ''Ondatra zibethicus

The muskrat (''Ondatra zibethicus'') is a medium-sized semiaquatic rodent native to North America and an introduced species in parts of Europe, Asia, and South America. The muskrat is found in wetlands over a wide range of climates and habitat ...

'', which is highly susceptible to this virus, was introduced into this area in the 1930s.

Taxonomy

Species

In the genus ''Flavivirus'' there are 53 defined species:Sorted by vector

Vaccines

The very successful yellow fever 17D vaccine, introduced in 1937, produced dramatic reductions in epidemic activity.

Effective inactivated

The very successful yellow fever 17D vaccine, introduced in 1937, produced dramatic reductions in epidemic activity.

Effective inactivated Japanese encephalitis

Japanese encephalitis (JE) is an infection of the brain caused by the Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV). While most infections result in little or no symptoms, occasional inflammation of the brain occurs. In these cases, symptoms may include he ...

and Tick-borne encephalitis

Tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) is a viral infectious disease involving the central nervous system. The disease most often manifests as meningitis, encephalitis or meningoencephalitis. Myelitis and spinal paralysis also occurs. In about one third ...

vaccines were introduced in the middle of the 20th century. Unacceptable adverse events have prompted change from a mouse-brain inactivated Japanese encephalitis vaccine

Japanese encephalitis vaccine is a vaccine that protects against Japanese encephalitis. The vaccines are more than 90% effective. The duration of protection with the vaccine is not clear but its effectiveness appears to decrease over time. Doses ...

to safer and more effective second generation Japanese encephalitis vaccines. These may come into wide use to effectively prevent this severe disease in the huge populations of Asia—North, South and Southeast.

The dengue viruses produce many millions of infections annually due to transmission by a successful global mosquito vector. As mosquito control has failed, several dengue vaccines are in varying stages of development. CYD-TDV, sold under the trade name Dengvaxia, is a tetravalent chimeric vaccine that splices structural genes of the four dengue viruses onto a 17D yellow fever backbone. Dengvaxia is approved in five countries.

References

Further reading

* * * * *External links

MicrobiologyBytes: Flaviviruses

– Dengue Fever research at the Novartis Institute for Tropical Diseases (NITD)

Dengueinfo.org

– Depository of dengue virus genomic sequence data

{{Authority control Rodent-carried diseases Flaviviridae Virus genera