As a winner-take-all method, FPTP often produces disproportional results (when electing members of an assembly, such as a parliament) in the sense that political parties do not get representation according to their share of the popular vote. This usually favours the largest party and parties with strong regional support to the detriment of smaller parties without a geographically concentrated base. Supporters of electoral reform are generally highly critical of FPTP because of this and point out other flaws, such as FPTP's vulnerability to gerrymandering, the high amount of wasted votes and the chance of a majority reversal (when the party that wins the most votes gets fewer seats than the second largest party, and so loses the election). For these reasons, many countries have abandoned FPTP in favour of other electoral systems, but FPTP is used as the primary form of allocating seats for legislative elections in about a third of the world's countries, mostly in the English-speaking world.

Some countries use FPTP alongside proportional representation in a parallel voting system, the PR element not compensating for but added to the disproportionality of FPTP. Others use it in so-called compensatory mixed systems, such as part of

As a winner-take-all method, FPTP often produces disproportional results (when electing members of an assembly, such as a parliament) in the sense that political parties do not get representation according to their share of the popular vote. This usually favours the largest party and parties with strong regional support to the detriment of smaller parties without a geographically concentrated base. Supporters of electoral reform are generally highly critical of FPTP because of this and point out other flaws, such as FPTP's vulnerability to gerrymandering, the high amount of wasted votes and the chance of a majority reversal (when the party that wins the most votes gets fewer seats than the second largest party, and so loses the election). For these reasons, many countries have abandoned FPTP in favour of other electoral systems, but FPTP is used as the primary form of allocating seats for legislative elections in about a third of the world's countries, mostly in the English-speaking world.

Some countries use FPTP alongside proportional representation in a parallel voting system, the PR element not compensating for but added to the disproportionality of FPTP. Others use it in so-called compensatory mixed systems, such as part of Terminology

The phrase ''first-past-the-post'' is a metaphor from BritishIllustration

Under a first-past-the-post voting method, the highest-polling candidate is elected. In this real-life illustration from the 2011 Singaporean presidential election, presidential candidate Tony Tan obtained a greater number of votes than any of the other candidates. Therefore, he was declared the winner, although the second-placed candidate had an inferior margin of only 0.35% and a majority of voters (64.8%) did not vote for Tony Tan: It is not clear that Tan would have won if the votes against him had not been split among the other three candidates.Effects

The effect of a system based on plurality voting spread over many separate districts is that the larger parties, and parties with more geographically concentrated support, gain a disproportionately large share of seats, while smaller parties with more evenly distributed support gain a disproportionately small share. As voting patterns are similar in about two-thirds of the districts, it is more likely that a single party will hold a majority of legislative seats under FPTP than happens in a proportional system, and under FPTP it is rare to elect a majority government that actually has the support of a majority of voters. In Canada, majority governments have been formed thanks to one party winning a majority of the votes cast in Canada only three times since 1921: in 1940 Canadian federal election, 1940, 1958 Canadian federal election, 1958 and 1984 Canadian federal election, 1984. In the United Kingdom, 19 of the 24 general elections since 1922 have produced a single-party majority government. In all but two of them (1931 United Kingdom general election, 1931 and 1935 United Kingdom general election, 1935), the leading party did not take a majority of the votes across the UK. For example, the 2005 United Kingdom general election, 2005 general election results were as follows: In this example, Labour took a majority of the seats with only 36% of the vote. The largest ''two'' parties took 69% of the vote and 88% of the seats. In contrast, the Liberal Democrats took more than 20% of the vote but only about 10% of the seats. FPTP wastes fewer votes when it is used in two-party contests. But waste of votes and minority governments are more likely when large groups of voters vote for three, four or more parties as in Canadian elections. Canada uses FPTP and only two of the last seven federal Canadian elections (2011 Canadian federal election, 2011 and 2015 Canadian federal election, 2015) produced single-party majority governments. In none of them did the leading party receive a majority of the votes.Arguments in support

Supporters of FPTP argue that it is easy to understand, and ballots can be counted and processed more easily than those in Ranked voting, preferential voting systems. FPTP often produces governments which have legislative voting majorities, thus providing such governments the legislative power necessary to implement their electoral manifesto commitments during their term in office. This may be beneficial for the country in question in circumstances where the government's legislative agenda has broad public support, albeit potentially divided across party lines, or at least benefits society as a whole. However handing a legislative voting majority to a government which lacks popular support can be problematic where said government's policies favour only that fraction of the electorate that supported it, particularly if the electorate divides on tribal, religious, or urban–rural lines. Supporters of FPTP also argue that the use of proportional representation (PR) may enable smaller parties to become decisive in the country's legislature and gain leverage they would not otherwise enjoy, although this can be somewhat mitigated by a large enough electoral threshold. They argue that FPTP generally reduces this possibility, except where parties have a strong regional basis. A journalist at ''Haaretz'' noted that Israel's highly proportional Knesset "affords great power to relatively small parties, forcing the government to give in to political blackmail and to reach compromises"; Tony Blair, defending FPTP, argued that other systems give small parties the balance of power, and influence disproportionate to their votes. Allowing people into parliament who did not finish first in their district was described by David Cameron as creating a "Parliament full of second-choices who no one really wanted but didn't really object to either." Winston Churchill criticized the alternative vote system as "determined by the most worthless votes given for the most worthless candidates."Arguments against

Unrepresentative

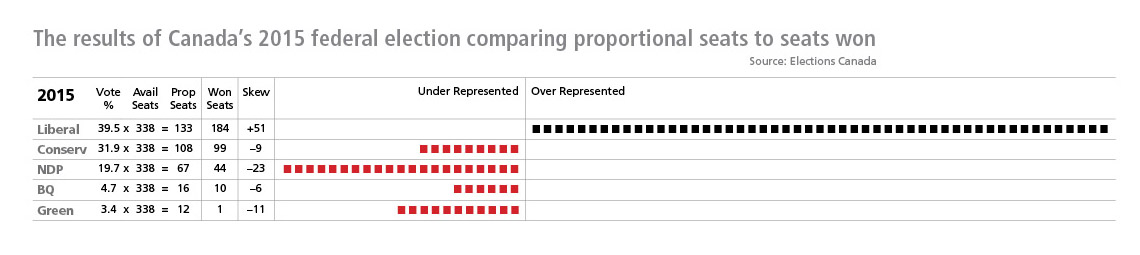

First past the post is most often criticized for its failure to reflect the popular vote in the number of parliamentary/legislative seats awarded to competing parties. Critics argue that a fundamental requirement of an election system is to accurately represent the views of voters, but FPTP often fails in this respect. It often creates "false majorities" by over-representing larger parties (giving a majority of the parliamentary/legislative seats to a party that did not receive a majority of the votes) while under-representing smaller ones. The diagram here, summarizing Canada's 2015 federal election, demonstrates how FPTP can misrepresent the popular vote.

First past the post is most often criticized for its failure to reflect the popular vote in the number of parliamentary/legislative seats awarded to competing parties. Critics argue that a fundamental requirement of an election system is to accurately represent the views of voters, but FPTP often fails in this respect. It often creates "false majorities" by over-representing larger parties (giving a majority of the parliamentary/legislative seats to a party that did not receive a majority of the votes) while under-representing smaller ones. The diagram here, summarizing Canada's 2015 federal election, demonstrates how FPTP can misrepresent the popular vote.

Wasted votes

Wasted votes are seen as those cast for losing candidates, and for winning candidates in excess of the number required for victory. For example, in the 2005 United Kingdom general election, UK general election of 2005, 52% of votes were cast for losing candidates and 18% were excess votes—a total of 70% "wasted" votes. On this basis a large majority of votes may play no part in determining the outcome. This winner-takes-all system may be one of the reasons why "voter participation tends to be lower in countries with FPTP than elsewhere."Majority reversal

A majority reversal or election inversion is a situation where the party that gets an overall majority of votes loses the election or does not get a plurality of seats. Famous examples of the second placed party (in votes nationally) winning a majority of seats include the elections in Ghana in 2012, in New Zealand in 1978 and in 1981 and in the United Kingdom in 1951. Famous examples of the second placed party (in votes nationally) winning a plurality of seats include the election in Canada in 2019 and 2021. Even when a party wins more than half the votes in an almost purely two-party-competition, it is possible for the runner-up to win a majority of seats. This happened in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines in 1966 Vincentian general election, 1966, 1998 Vincentian general election, 1998 and 2020 Vincentian general election, 2020 and in Belize in 1993 Belizean general election, 1993. This need not be a result of malapportionment. Even if all seats represent the same number of votes, the second placed party (in votes nationally) can win a majority of seats by efficient vote distribution. Winning seats narrowly and losing elsewhere by big margins is more efficient than winning seats by big margins and losing elsewhere narrowly. For a majority in seats, it is enough to win a plurality of votes in a majority of constituencies. Even with only two parties and equal constituencies, to win a majority of seats just requires receiving more than half the vote in more than half the districts -- even if the other party receives all the votes cast in the other districts -- so just over a quarter of the votes of the whole is theoretically enough for a majority in the legislature. Where multiple parties split the vote in a district, as few as 18 percent of the vote is enough to take a seat in FPTP. And where multiple parties win seats, a minority position in the legislature (a party with much less members than half of the assembly) could have the largest block in the chamber and be set in a commanding position, although still needing majority support to pass a bill.Geographical problems

Geographical favouritism

Generally FPTP favours parties who can concentrate their vote into certain voting districts (or in a wider sense in specific geographic areas). This is because in doing this they win many seats and don't 'waste' many votes in other areas. The British Electoral Reform Society (ERS) says that regional parties benefit from this system. "With a geographical base, parties that are small UK-wide can still do very well". On the other hand, minor parties that do not concentrate their vote usually end up getting a much lower proportion of seats than votes, as they lose most of the seats they contest and 'waste' most of their votes. The ERS also says that in FPTP elections using many separate districts "small parties without a geographical base find it hard to win seats". Make Votes Matter said that in the 2017 United Kingdom general election, 2017 UK general election, "the Green Party, Liberal Democrats and UKIP (minor, non-regional parties) received 11% of votes between them, yet they ''shared'' just 2% of seats", and in the 2015 United Kingdom general election, 2015 UK general election, "[t]he same three parties received almost a quarter of all the votes cast, yet these parties ''shared'' just 1.5% of seats." According to Make Votes Matter, and shown in the chart below, in the 2015 UK general election UK Independence Party, UKIP came in third in terms of number of votes (3.9 million/12.6%), but gained only one seat in Parliament, resulting in one seat per 3.9 million votes. The Conservatives on the other hand received one seat per 34,000 votes.Distorted geographical representation

The winner-takes-all nature of FPTP leads to distorted patterns of representation, since it exaggerates the correlation between party support and geography. For example, in the UK the Conservative Party (UK), Conservative Party represents most of the rural seats in England, and most of the south of England, while the Labour Party (UK), Labour Party represents most of the English cities and most of the north of England. This pattern hides the large number of votes for the non-dominant party. Parties can find themselves without elected politicians in significant parts of the country, heightening feelings of regionalism. Party supporters (who may nevertheless be a significant minority) in those sections of the country are unrepresented. In the 2019 Canadian federal election Conservative Party of Canada, Conservatives won 98% of the seats in Alberta and Saskatchewan with only 68% of the vote. The lack of non-Conservative representation gives the appearance of greater Conservative support than actually exists. Similarly, in Canada's 2021 elections, the Conservative Party won 88% of the seats in Alberta with only 55% of the vote, and won 100% of the seats in Saskatchewan with only 59% of the vote.Safe seats

First-past-the-post within geographical areas tends to deliver (particularly to larger parties) a significant number of safe seats, where a representative is sheltered from any but the most dramatic change in voting behaviour. In the UK, the Electoral Reform Society estimates that more than half the seats can be considered as safe. It has been claimed that members involved in the 2009 United Kingdom parliamentary expenses scandal, expenses scandal were significantly more likely to hold a safe seat. However, other voting systems, notably the Party-list proportional representation, party-list system, can also create politicians who are relatively immune from electoral pressure (especially when using a closed-list).Tactical voting

To a greater extent than many others, the first-past-the-post method encourages "tactical voting". Voters have an incentive to vote for a candidate who they predict is more likely to win, as opposed to their preferred candidate who may be unlikely to win and for whom a vote could be considered as wasted vote, wasted. The position is sometimes summarised, in an extreme form, as "all votes for anyone other than the runner-up are votes for the winner." This is because votes for these other candidates deny potential support from the second-placed candidate, who might otherwise have won. Following the extremely close 2000 United States presidential election, 2000 U.S. presidential election, some supporters of Democratic Party (United States), Democratic candidate Al Gore believed one reason he lost to Republican Party (United States), Republican George W. Bush is that a portion of the electorate (2.7%) voted for Ralph Nader of the Green Party (United States), Green Party, and exit polls indicated that more of them would have preferred Gore (45%) to Bush (27%). This election was ultimately determined by the United States presidential election in Florida, 2000, results from Florida, where Bush prevailed over Gore by a margin of only 537 votes (0.009%), which was far exceeded by the 97488 (1.635%) votes cast for Nader in that state. In Puerto Rico, there has been a tendency for Puerto Rican Independence Party, Independentista voters to support Popular Democratic Party of Puerto Rico, Populares candidates. This phenomenon is responsible for some Popular victories, even though the New Progressive Party of Puerto Rico, Estadistas have the most voters on the island, and is so widely recognised that Puerto Ricans sometimes call the Independentistas who vote for the Populares "melons", because that fruit is green on the outside but red on the inside (in reference to the party colors). Because voters have to predict who the top two candidates will be, results can be significantly distorted: * Some voters will vote based on their view of how others will vote as well, changing their originally intended vote; * Substantial power is given to the media, because some voters will believe its assertions as to who the leading contenders are likely to be. Even voters who distrust the media will know that others ''do'' believe the media, and therefore those candidates who receive the most media attention will probably be the most popular; * A new candidate with no track record, who might otherwise be supported by the majority of voters, may be considered unlikely to be one of the top two, and thus lose votes to tactical voting; * The method may promote votes ''against'' as opposed to votes ''for''. For example, in the UK (and only in the Great Britain region), entire campaigns have been organised with the aim of voting ''against'' the Conservative Party (UK), Conservative Party by voting Labour Party (UK), Labour, Liberal Democrats (UK), Liberal Democrat in England and Wales, and since 2015 the Scottish National Party, SNP in Scotland, depending on which is seen as best placed to win in each locality. Such behaviour is difficult to measure objectively. Proponents of other voting methods in single-member districts argue that these would reduce the need for tactical voting and reduce the spoiler effect. Examples include preferential voting systems, such as Instant-runoff voting, instant runoff voting, as well as the two-round system of runoffs and less tested methods such as approval voting and Condorcet methods.Effect on political parties and society

Duverger's law is an idea in political science which says that constituencies that use first-past-the-post methods will lead to two-party systems, given enough time. Economist Jeffrey Sachs explains: However, most countries with first-past-the-post elections have multiparty legislatures (albeit with two parties larger than the others), the United States being the major exception. There is a counter-argument to Duverger's Law, that while on the national level a plurality system may encourage two parties, in the individual constituencies supermajorities will lead to the vote fracturing. It has been suggested that the distortions in geographical representation provide incentives for parties to ignore the interests of areas in which they are too weak to stand much chance of gaining representation, leading to governments that do not govern in the national interest. Further, during election campaigns the campaigning activity of parties tends to focus on marginal seats where there is a prospect of a change in representation, leaving safer areas excluded from participation in an active campaign. Political parties operate by targeting districts, directing their activists and policy proposals toward those areas considered to be marginal, where each additional vote has more value.Smaller parties may reduce the success of the largest similar party

Under first-past-the-post, a small party may draw votes and seats away from a larger party that it is ''more'' similar to, and therefore give an advantage to one it is ''less'' similar to. For example, in the 2000 United States presidential election, the left-leaning Ralph Nader drew more votes from the left-leaning Al Gore than his opponent, leading to Ralph Nader 2000 presidential campaign#The "spoiler" controversy, accusations that Nader was a "spoiler" for the Democrats.Suppression of political diversity

According to the political pressure group Make Votes Matter, FPTP creates a powerful electoral incentive for large parties to target similar segments of voters with similar policies. The effect of this reduces political diversity in a country because the larger parties are incentivised to coalesce around similar policies. The ACE Electoral Knowledge Network describes India's use of FPTP as a "legacy of British colonialism".May abet extreme politics

The Constitution Society published a report in April 2019 stating that, "[in certain circumstances] FPTP can ... abet Extremism, extreme politics, since should a radical faction gain control of one of the major political parties, FPTP works to preserve that party's position. ...This is because the psychological effect of the plurality system disincentivises a major party's supporters from voting for a minor party in protest at its policies, since to do so would likely only help the major party's main rival. Rather than curtailing extreme voices, FPTP today empowers the (relatively) extreme voices of the Labour and Conservative party memberships." Electoral reform campaigners have argued that the use of FPTP in South Africa was a contributory factor in the country adopting the apartheid system after the 1948 South African general election#Results, 1948 general election in that country.Likelihood of involvement in war

Leblang and Chan found that a country's electoral system is the most important predictor of a country's involvement in war, according to three different measures: (1) when a country was the first to enter a war; (2) when it joined a multinational coalition in an ongoing war; and (3) how long it stayed in a war after becoming a party to it. When the people are fairly represented in parliament, more of those groups who may object to any potential war have access to the political power necessary to prevent it. In a proportional democracy, war and other major decisions generally requires the consent of the majority. The British human rights campaigner Peter Tatchell, and others, have argued that Britain entered the Iraq War primarily because of the political effects of FPTP and that proportional representation would have prevented Britain's involvement in the war.Manipulation

Gerrymandering

Because FPTP permits many wasted votes, an election under FPTP is more easily gerrymandered. Through gerrymandering, electoral areas are designed deliberately to unfairly increase the number of seats won by one party by redrawing the map such that one party has a small number of districts in which it has an overwhelming majority of votes (whether due to policy, demographics which tend to favour one party, or other reasons), and many districts where it is at a smaller disadvantage.Manipulation charges

The presence of spoiler (politician), spoilers often gives rise to suspicions that strategic nomination, manipulation of the slate has taken place. A spoiler may have received incentives to run. A spoiler may also drop out at the last moment, inducing charges that dropping out had been intended from the beginning.Campaigns to replace FPTP

Many countries which use FPTP have active campaigns to switch to proportional representation (e.g. UK and Canada). Most modern democracies use forms of proportional representation (PR). In the case of the UK, the campaign to scrap FPTP has been ongoing since at least the 1970s. However, in both these countries, reform campaigners face the obstacle of large incumbent parties who control the legislature and who are incentivised to resist any attempts to replace the FPTP system that elected them on a minority vote.Voting method criteria

Scholars rate voting methods using mathematically derived voting method criterion, voting method criteria, which describe desirable features of a method. No ranked preference method can meet all the criteria, because some of them are mutually exclusive, as shown by results such as Arrow's impossibility theorem and the Gibbard–Satterthwaite theorem.FPTP as a single-winner system

FPTP used in single-member constituencies to elect assemblies (SMP)

Countries using FPTP/SMP

Heads of state elected by FPTP

* Angola * Bosnia and Herzegovina (one for each main ethnic group) * Cameroon * Democratic Republic of the Congo * Equatorial Guinea * The Gambia * Honduras * Iceland * Kiribati * Malawi * Mexico * Nicaragua * State of Palestine, Palestine * Panama * Paraguay * Philippines * Rwanda * Singapore * South Korea * Taiwan, Republic of China (Taiwan) - Additional Articles of the Constitution of the Republic of China, constitutional amendment, from 1996 * Tanzania * VenezuelaLegislatures elected exclusively by FPTP/SMP

The following is a list of countries currently following the first-past-the-post voting system for their national legislatures. * Antigua and Barbuda * Azerbaijan * Bahamas * Bangladesh * Barbados * Belarus * Belize * Bhutan (both houses) * Botswana * Canada (for the House of Commons (Canada), lower house only) * Dominica * Dominican Republic * Eritrea * Eswatini * Ethiopia * The Gambia * Ghana * Grenada * India (for the Lok Sabha, lower house only) * Jamaica * Kenya * Liberia * Malaysia * Malawi * Maldives * Micronesia * Myanmar (both houses) * Nigeria (both houses) * Palau (both houses) * Poland (for Senate of Poland, upper house only) * Qatar * Saint Kitts and Nevis * Saint Lucia * Saint Vincent and the Grenadines * Samoa * Sierra Leone * Solomon Islands * Tonga * Trinidad and Tobago * Uganda * United Kingdom * Elections in the United States, United States (both houses) - see footnote * Yemen * Zambia Subnational legislatures * Cook Islands (New Zealand) * US Virgin Islands * Bermuda * Cayman Islands * British Virgin Islands Footnote: Prior to the 2020 United States election, 2020 election, the US states of Alaska and Maine completely abandoned FPTP in favor of Instant-runoff voting, ranked-choice voting or RCV. In the US, 48 of the 50 U.S. state, states and the Washington, D.C., District of Columbia use FPTP to choose the electors of the Electoral College (United States), Electoral College (which in turn elects the president); Maine and Nebraska use a variation where the electoral vote of each congressional district is awarded by FPTP, and the statewide winner is awarded an additional two electoral votes. In states that employ FPTP, the presidential candidate gaining the greatest number of votes wins all the state's available electors (seats), regardless of the number or share of votes won, or the difference separating the leading candidate and the first runner-up.Use of FPTP/SMP in mixed systems for electing legislatures

The following countries use FPTP/SMP to elect part of their national legislature, in different types of mixed systems. Alongside block voting (fully majoritarian systems) or as part of mixed-member majoritarian systems (semi-proportional representation) * Brazil – in the Brazilian Senate, Federal Senate, alongside plurality block voting (alternating elections) * Cote d'Ivoire – in single-member electoral districts, alongside party block voting * Iran – in single-member electoral districts for Assembly of Experts, Khobregan, alongside plurality block voting * Marshall Islands – in single-member electoral districts, alongside plurality block voting * Oman – in single-member electoral districts, alongside plurality block voting * Pakistan – alongside seats distributed proportional to seats already won * Singapore – in single-member electoral districts, alongside plurality block voting * South Korea – as part is a mixed system (AMS and parallel voting) * Taiwan, Republic of China (Taiwan) – as part is a mixed system (parallel voting) As part of mixed-member proportional (MMP) or additional member systems (AMS) * Bolivia * Germany * Lesotho * New Zealand Subnational legislatures * Scottish Parliament, Scotland (United Kingdom) * Senedd Cymru, Wales (United Kingdom) Local elections * London Assembly, Greater London (United Kingdom; not a legislature) * Certain municipalities in South AfricaFormer use

* Argentina (The Argentine Chamber of Deputies, Chamber of Deputies uses Party-list proportional representation, party list PR. Only twice used FPTP, first between 1902 and 1905 used only in the 1904 Argentine presidential election, elections of 1904, and the second time between 1951 and 1957 used only in the 1951 Argentine general election, elections of 1951 and 1954 Argentine legislative election, 1954.) * Australia (replaced by Instant-runoff voting, IRV in 1918 for both the Australian House of Representatives, House of Representatives and the Australian Senate, Senate, with Single transferable vote, STV being introduced to the Senate in 1948) * Belgium (adopted in 1831, replaced by Party-list proportional representation, party list PR in 1899)— the Member of the European Parliament for the German-speaking electoral college is still elected by FPTP * Cyprus (replaced by proportional representation in 1981) * Denmark (replaced by proportional representation in 1920) * Hong Kong (adopted in 1995, replaced by Party-list proportional representation, party list PR in 1998) * Japan (replaced by parallel voting in 1993 Japanese general election, 1993) * Lebanon (replaced by proportional representation in June 2017) * Lesotho (replaced by Mixed-member proportional representation, MMP Party-list proportional representation, Party list in 2002) * Malta (replaced by Single transferable vote, STV in 1921) * Mexico (replaced by parallel voting in 1977) * Nepal (replaced by parallel voting) * Netherlands (replaced by Party-list proportional representation, party list PR in 1917) * New Zealand (replaced by Mixed-member proportional representation, MMP in 1996) * Papua New Guinea (replaced by Instant-runoff voting, IRV in 2002) *Philippines (replaced by parallel voting in 1998 for House of Representatives elections, and by multiple non-transferable vote in 1941 for Senate elections) * Portugal (replaced by Party-list proportional representation, party list PR) *South Africa (replaced by Party-list proportional representation, party list PR in 1994) * Tanzania (replaced by parallel voting in 1995)See also

* Cube rule * Deviation from proportionality * Plurality-at-large voting * Approval voting * Single non-transferable vote * Single transferable voteReferences

External links

A handbook of Electoral System Design

fro

International IDEA

ACE Project: What is the electoral system for Chamber1 of the national legislature?

€”detailed explanation of first-past-the-post voting

ACE Project: Electing a President using FPTP

ACE Project: FPTP on a grand scale in India

The Citizens' Assembly on Electoral Reform says the new proportional electoral system it proposes for British Columbia will improve the practice of democracy in the province.

Vote No to Proportional Representation BC

* [http://www.game-point.net/misc/election2005/ The Problem With First-Past-The-Post Electing (data from UK general election 2005)] *

The fatal flaws of First-past-the-post electoral systems

{{DEFAULTSORT:First-Past-The-Post Single-winner electoral systems