Ferdinand Stoliczka on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ferdinand Stoliczka (

His early works were studies on some freshwater

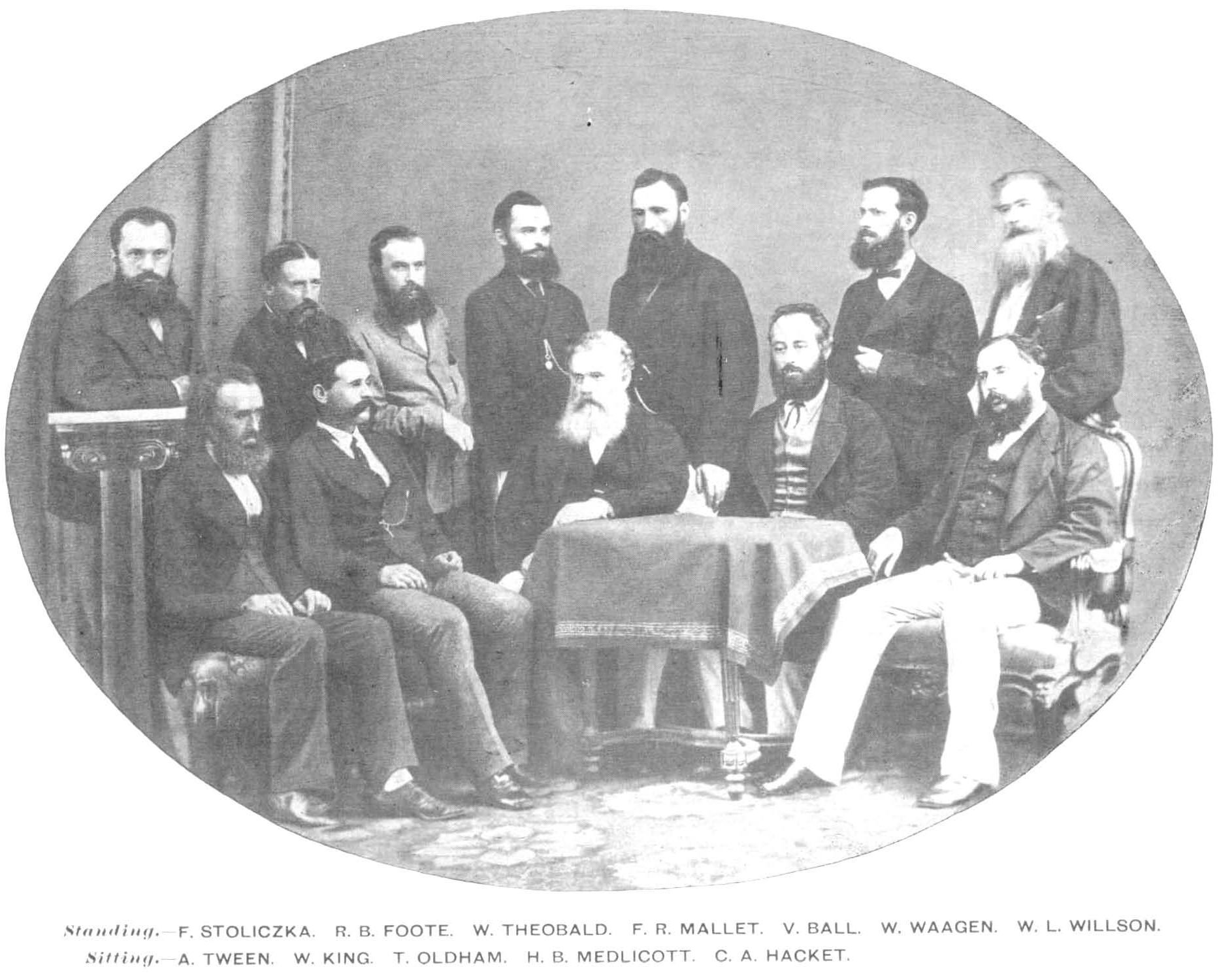

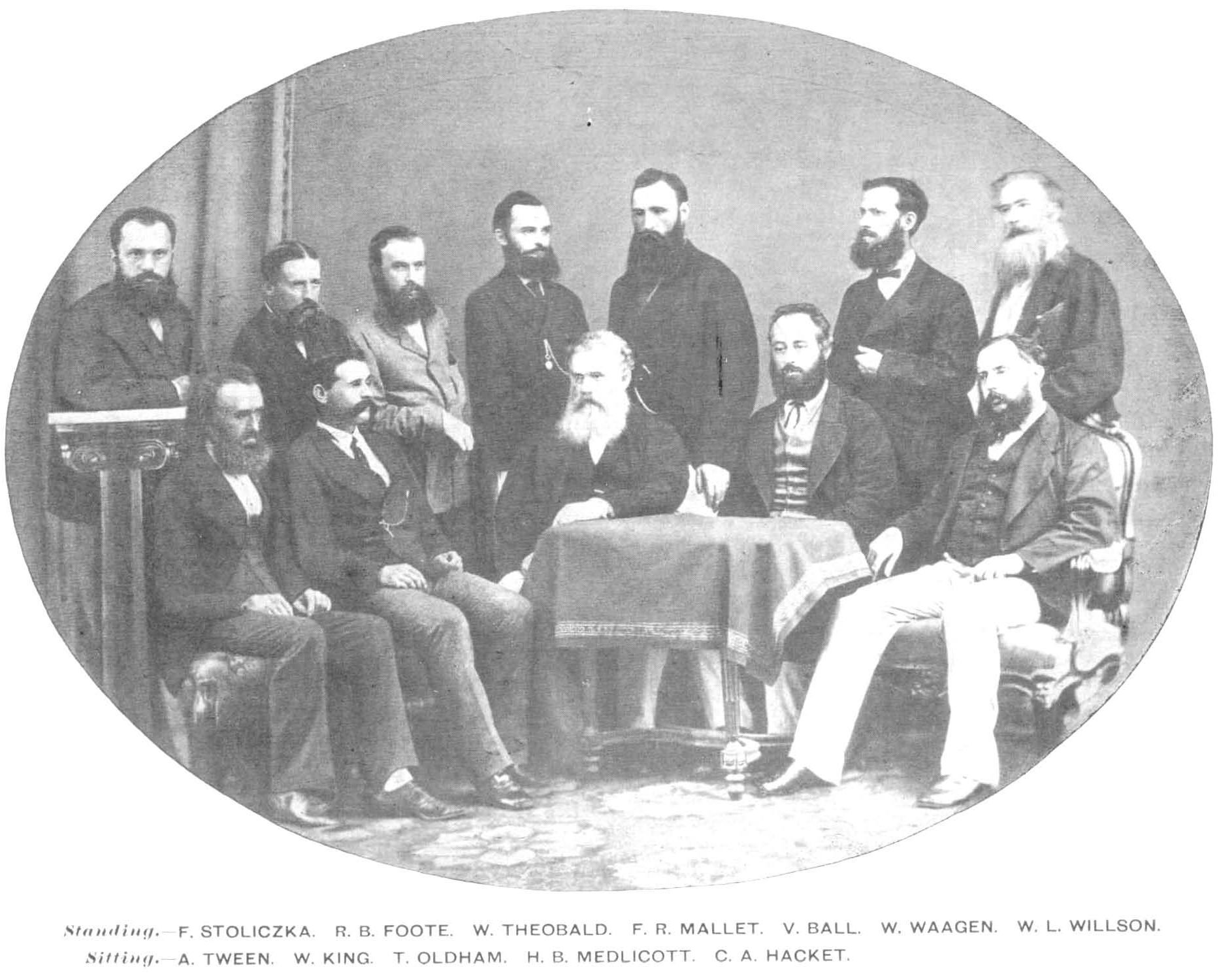

In 1862 Stoliczka joined the

In 1862 Stoliczka joined the  He studied the geology of the western

He studied the geology of the western

His third and last expedition was the most important expedition (1873–1874) during the height of the "

His third and last expedition was the most important expedition (1873–1874) during the height of the " Dr. H. W. Bellew did the post-mortem and confirmed "spinal meningitis deteriorated by over-exertion in strenuous endeavours after information, and the great height." Today this is generally believed to have been Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS), a condition well known to Himalayan travellers. It manifests as pulmonary or cerebral oedema. Above this is fatal in about 40% of the cases. Conditions that aggravate it include exertion, fast ascent and alcohol, all of which were present in his case.

In his report on the expedition, Thomas E. Gordon touched on the death of his "highly valued friend and talented companion." Gordon, Thomas Edward (1876) .

Dr. H. W. Bellew did the post-mortem and confirmed "spinal meningitis deteriorated by over-exertion in strenuous endeavours after information, and the great height." Today this is generally believed to have been Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS), a condition well known to Himalayan travellers. It manifests as pulmonary or cerebral oedema. Above this is fatal in about 40% of the cases. Conditions that aggravate it include exertion, fast ascent and alcohol, all of which were present in his case.

In his report on the expedition, Thomas E. Gordon touched on the death of his "highly valued friend and talented companion." Gordon, Thomas Edward (1876) .

The roof of the world: being a narrative of a journey over the high plateau of Tibet to the Russian frontier and the Oxus sources on Pamir.

' Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas. p. 171. A granite obelisk is erected in his memory at the Moravian mission cemetery in

Stoliczka's interest in birds started only in 1864 when in the Himalayas and he was greatly encouraged by

Stoliczka's interest in birds started only in 1864 when in the Himalayas and he was greatly encouraged by

Scientific results of the second Yarkand Mission; (1891)Birds

Herbert Giess, Early Modern European Explorers at the Mountain Jade Quarries in the Kun Lun Mountains in Xinjiang, China

Genera proposed by Stoliczka

(1871) Paleontologia Indica. Cretaceous fauna of southern India. Volume 3

{{DEFAULTSORT:Stoliczka, Ferdinand 1838 births 1874 deaths Austrian ornithologists Austrian paleontologists Austrian lepidopterists Charles University alumni Czech ornithologists Czech paleontologists Czech entomologists Czech lepidopterists Moravian-German people Austrian people of Czech descent Explorers of Central Asia Explorers of the Himalayas People from Kroměříž

Czech

Czech may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the Czech Republic, a country in Europe

** Czech language

** Czechs, the people of the area

** Czech culture

** Czech cuisine

* One of three mythical brothers, Lech, Czech, and Rus'

Places

* Czech, ...

written Stolička, 7 June 1838 – 19 June 1874) was a Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The me ...

n palaeontologist

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

who worked in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

on paleontology

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

, geology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Ear ...

and various aspects of zoology

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the Animal, animal kingdom, including the anatomy, structure, embryology, evolution, Biological clas ...

, including ornithology

Ornithology is a branch of zoology that concerns the "methodological study and consequent knowledge of birds with all that relates to them." Several aspects of ornithology differ from related disciplines, due partly to the high visibility and th ...

, malacology

Malacology is the branch of invertebrate zoology that deals with the study of the Mollusca (mollusks or molluscs), the second-largest phylum of animals in terms of described species after the arthropods. Mollusks include snails and slugs, clams, ...

, and herpetology

Herpetology (from Greek ἑρπετόν ''herpetón'', meaning "reptile" or "creeping animal") is the branch of zoology concerned with the study of amphibians (including frogs, toads, salamanders, newts, and caecilians (gymnophiona)) and rept ...

. He died of high altitude sickness in Murgo

Murgo is a small hilly village which lies on the border of Leh district in the union territory of Ladakh in India, close to Chinese-controlled Aksai Chin. It is one of the northernmost villages of India.

Name

The name "Murgo" means "gatewa ...

during an expedition across the Himalayas.

Early life

Stoliczka was born at the lodge ''Zámeček'' nearKroměříž

Kroměříž (; german: Kremsier) is a town in the Zlín Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 28,000 inhabitants. It is known for the Kroměříž Castle with castle gardens, which are a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The town centre with the c ...

in Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The me ...

. Stoliczka, whose father was a forester who took care of the estate of the Archbishop of Olomouc, studied at a German Secondary school in Kroměříž. Although Stoliczka published 79 articles from 1859–1875, he never wrote anything in Czech. It is believed that he spoke German at home. In his Calcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, the official name until 2001) is the Capital city, capital of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal, on the eastern ba ...

years he was an important figure in the German-speaking community there.

Stoliczka studied geology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Ear ...

and palaeontology at Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

and the University of Vienna

The University of Vienna (german: Universität Wien) is a public research university located in Vienna, Austria. It was founded by Duke Rudolph IV in 1365 and is the oldest university in the German-speaking world. With its long and rich histor ...

under Professor Eduard Suess

Eduard Suess (; 20 August 1831 - 26 April 1914) was an Austrian geologist and an expert on the geography of the Alps. He is responsible for hypothesising two major former geographical features, the supercontinent Gondwana (proposed in 1861) and t ...

and Dr Rudolf Hoernes

Rudolf Hoernes (7 October 1850 – 20 August 1912) was an Austrian geologist, born in Vienna, son of Moritz Hoernes. He studied under Eduard Suess and became a Professor of geology in Graz. He was known for his earthquake studies in 1878 and ...

. He graduated with a Ph D from the University of Tübingen on 14 November 1861.His early works were studies on some freshwater

mollusca

Mollusca is the second-largest phylum of invertebrate animals after the Arthropoda, the members of which are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 85,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized. The number of fossil species is esti ...

from the Cretaceous rocks of the north-eastern Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Sw ...

about which he wrote to the Vienna Academy in 1859. His scientific career proper started in the Austrian Geological Survey, which he joined in 1861, and his first papers there were based on work in the Alps and Hungary.

Career in India

In 1862 Stoliczka joined the

In 1862 Stoliczka joined the Geological Survey of India

The Geological Survey of India (GSI) is a scientific agency of India. It was founded in 1851, as a Government of India organization under the Ministry of Mines, one of the oldest of such organisations in the world and the second oldest survey ...

(GSI) under the British Government in India after being recruited by Dr Thomas Oldham

Thomas Oldham (4 May 1816, Dublin – 17 July 1878, Rugby) was an Anglo-Irish geologist.

He was educated at Trinity College, Dublin and studied civil engineering at the University of Edinburgh as well as geology under Robert Jameson.

In 183 ...

(1816–1878). In Calcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, the official name until 2001) is the Capital city, capital of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal, on the eastern ba ...

he was assigned the job of documenting the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of th ...

fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

s of southern India and published them in the ''Palaeontologia indica'', along with William Thomas Blanford

William Thomas Blanford (7 October 183223 June 1905) was an English geologist and naturalist. He is best remembered as the editor of a major series on ''The Fauna of British India, Including Ceylon and Burma''.

Biography

Blanford was born ...

. By May 1873 this work was completed with four volumes totalling nearly 1500 quarto size pages with 178 plates. Among these works was the osteological description of ''Oxyglossus pusillus'', a fossil frog from the Deccan Traps

The Deccan Traps is a large igneous province of west-central India (17–24°N, 73–74°E). It is one of the largest volcanic features on Earth, taking the form of a large shield volcano. It consists of numerous layers of solidified flood ...

of Bombay.

He studied the geology of the western

He studied the geology of the western Himalayas

The Himalayas, or Himalaya (; ; ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the planet's highest peaks, including the very highest, Mount Everest. Over 100 ...

and Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa people, ...

, and published numerous papers on many subjects including Indian zoology

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the Animal, animal kingdom, including the anatomy, structure, embryology, evolution, Biological clas ...

. He was also briefly (in 1868) the joint curator of the Indian Museum and also the Natural History Secretary of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. He was involved in editing the Society's journal.

Expeditions

He visited Burma, Malaya and Singapore, and made two trips to the Andaman and Nicobar Islands and theRann of Kutch

The Rann of Kutch (alternately spelled as Kuchchh) is a large area of salt marshes that span the border between India and Pakistan. It is located in Gujarat (primarily the Kutch district), India, and in Sindh, Pakistan. It is divided into t ...

. His first Himalayan trip was in 1864 with F. R. Mallet of the GSI. In 1865 he visited again with an artist friend and a dog to the Ladakh Valley. He visited Kutch in 1871–1872 but noted that his geology work kept him from making many observations. He noted wild cheetah

The cheetah (''Acinonyx jubatus'') is a large cat native to Africa and central Iran. It is the fastest land animal, estimated to be capable of running at with the fastest reliably recorded speeds being , and as such has evolved specialized ...

s from the region and also what is now Stoliczka's bushchat. In 1873 he joined an expedition organized by Hume along with Valentine Ball

Valentine Ball (14 July 1843 – 15 June 1895) was an Irish geologist, son of Robert Ball (1802–1857) and a brother of Sir Robert Ball. Ball worked in India for twenty years before returning to take up a position in Ireland.

Life and wo ...

to the Andaman and Nicobar islands.

Last expedition

His third and last expedition was the most important expedition (1873–1874) during the height of the "

His third and last expedition was the most important expedition (1873–1874) during the height of the "Great Game

The Great Game is the name for a set of political, diplomatic and military confrontations that occurred through most of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century – involving the rivalry of the British Empire and the Russian Empi ...

", the rivalry between the Russian and British empires. Eastern Turkestan (Kashgar

Kashgar ( ug, قەشقەر, Qeshqer) or Kashi ( zh, c=喀什) is an oasis city in the Tarim Basin region of Southern Xinjiang. It is one of the westernmost cities of China, near the border with Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Pakistan ...

ia) was a buffer state of prime importance. The British launched an official diplomatic enterprise—the Second Yarkand Mission

The second (symbol: s) is the unit of time in the International System of Units (SI), historically defined as of a day – this factor derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes and finally to 60 seconds ...

led by Thomas Douglas Forsyth

Sir Thomas Douglas Forsyth (7 October 1827 – 17 December 1886) was an Anglo-Indian administrator and diplomat.

Early life

Forsyth was born in Birkenhead on 7 October 1827. He was the tenth child of Thomas Forsyth, a Liverpool merchant. His ...

and to Yakub Beg

Muhammad Yaqub Bek (محمد یعقوب بیگ; uz, Яъқуб-бек, ''Ya’qub-bek''; ; 182030 May 1877) was a Khoqandi ruler of Yettishar (Kashgaria) during his invasion of Xinjiang from 1865 to 1877. He held the title of Atalik Ghazi (" ...

, the ruler of Chinese Turkestan. The mission included 350 support staff and 550 animals. The expedition also needed 6476 porters and 1621 horses and it is said that the Ladakh economy took four years to recover from the losses incurred. The seven sahibs on the mission, in addition to Forsyth and Stoliczka, were Thomas E. Gordon, John Biddulph

Colonel John Biddulph (25 July 1840 – 24 December 1921) was a British soldier, author and naturalist who served in the government of British India.

Biddulph was born in 1840, and was the third son of Robert Biddulph. He was educated at Wes ...

, Henry Bellew, Henry Trotter, and R. A. Champman. Trotter, Henry (1917). "The Amir Yakoub Khan and Eastern Turkestan in Mid-Nineteenth Century". ''Journal of the Royal Central Asian Society

''Asian Affairs'', the journal of the Royal Society for Asian Affairs, has been published continuously since 1914 (originally as the ''Journal of the Central Asian Society'', and from 1931 to 1969 as the ''Journal of the Royal Central Asian Socie ...

'' 4 (4): 95-112.

The mission set out from Rawalpindi

Rawalpindi ( or ; Urdu, ) is a city in the Punjab province of Pakistan. It is the fourth largest city in Pakistan after Karachi, Lahore and Faisalabad, and third largest in Punjab after Lahore and Faisalabad. Rawalpindi is next to Pakistan's ...

to Leh ''via'' Murree. The mission travelled past the Pangong Lake

Pangong Tso or Pangong Lake (;

; hi, text=पैंगोंग झील) is an endorheic lake spanning eastern Ladakh and West Tibet situated at an elevation of . It is long and divided into five sublakes, called ''Pangong Tso'', ''Tso ...

, Changchenmo and Karakash Valley onto Shahidulla and finally to Yarkand

Yarkant County,, United States National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency also Shache County,, United States National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency also transliterated from Uyghur as Yakan County, is a county in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous ...

. They reached Kashgar in December 1873. On 17 March 1874 they began the return journey. They were to visit the Pamir and Afghanistan areas but could not do so due to the political situation and returned to India via Ladakh. On 16 June 1874 he had severe headaches as they crossed the Karakoram pass (5580 m). That night, he wrote....

:''...upon this followed massive dolomitic limestone and this was overlain with blue shales. I must have a ramble in these limestones tomorrow.''

Captain Trotter reported that on the 18th "he started on horseback early in the morning to examine some rocks up the stream." He returned tired and complained of a headache. He breathed heavily and coughed all night. The native doctor diagnosed acute bronchitis and inflammation of the lungs and treated him with brandy mixed in a cough mixture. At 2 p.m. he drank some port wine and "his respiration grew slower and slower, and also did his pulse, and he finally breathed his last, dying so quietly that it was impossible to say at what precise instant he passed away".

Stoliczka died on 19 June 1874 at Murgo

Murgo is a small hilly village which lies on the border of Leh district in the union territory of Ladakh in India, close to Chinese-controlled Aksai Chin. It is one of the northernmost villages of India.

Name

The name "Murgo" means "gatewa ...

in Ladakh

Ladakh () is a region administered by India as a union territory which constitutes a part of the larger Kashmir region and has been the subject of dispute between India, Pakistan, and China since 1947. (subscription required) Quote: "Jammu and ...

. His dying request was that the birds part of the scientific results of the expedition be published by Allan Octavian Hume

Allan Octavian Hume, CB ICS (4 June 1829 – 31 July 1912) was a British civil servant, political reformer, ornithologist and botanist who worked in British India. He was the founder of the Indian National Congress. A notable ornithologist, Hum ...

. This work was finally, however, completed by Richard Bowdler-Sharpe seventeen years later.

Dr. H. W. Bellew did the post-mortem and confirmed "spinal meningitis deteriorated by over-exertion in strenuous endeavours after information, and the great height." Today this is generally believed to have been Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS), a condition well known to Himalayan travellers. It manifests as pulmonary or cerebral oedema. Above this is fatal in about 40% of the cases. Conditions that aggravate it include exertion, fast ascent and alcohol, all of which were present in his case.

In his report on the expedition, Thomas E. Gordon touched on the death of his "highly valued friend and talented companion." Gordon, Thomas Edward (1876) .

Dr. H. W. Bellew did the post-mortem and confirmed "spinal meningitis deteriorated by over-exertion in strenuous endeavours after information, and the great height." Today this is generally believed to have been Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS), a condition well known to Himalayan travellers. It manifests as pulmonary or cerebral oedema. Above this is fatal in about 40% of the cases. Conditions that aggravate it include exertion, fast ascent and alcohol, all of which were present in his case.

In his report on the expedition, Thomas E. Gordon touched on the death of his "highly valued friend and talented companion." Gordon, Thomas Edward (1876) .The roof of the world: being a narrative of a journey over the high plateau of Tibet to the Russian frontier and the Oxus sources on Pamir.

' Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas. p. 171. A granite obelisk is erected in his memory at the Moravian mission cemetery in

Leh

Leh () ( lbj, ) is the joint capital and largest city of Ladakh, a union territory of India. Leh, located in the Leh district, was also the historical capital of the Kingdom of Ladakh, the seat of which was in the Leh Palace, the former res ...

. An obituary was published in ''Nature'' on 9 July 1874 by W. T. Blanford.

Ornithological contributions

Stoliczka's interest in birds started only in 1864 when in the Himalayas and he was greatly encouraged by

Stoliczka's interest in birds started only in 1864 when in the Himalayas and he was greatly encouraged by Allan Octavian Hume

Allan Octavian Hume, CB ICS (4 June 1829 – 31 July 1912) was a British civil servant, political reformer, ornithologist and botanist who worked in British India. He was the founder of the Indian National Congress. A notable ornithologist, Hum ...

, the "father of Indian Ornithology". His first ornithological work was making large collections of birds from the Sutlej Valley.

Arthur Viscount Walden recognized his contributions and welcomed the geologist Stoliczka ''to a high place among scientific ornithologists'' but disagreed with Stoliczka's idea of adding new species due to small differences in plumage. Hume however supported Stoliczka and wrote a note in the journal, Ibis, against the ''cabinet naturalists'' of London who knew nothing about the geography of India. Hume shortly afterwards started the journal ''Stray Feathers'' and persuaded ornithologists in India to publish there.

Some of Stoliczka's new species were later found to have been already described by the Russian zoologist N. A. Severtzov. A week before his death, Stoliczka wrote to Valentine Ball

Valentine Ball (14 July 1843 – 15 June 1895) was an Irish geologist, son of Robert Ball (1802–1857) and a brother of Sir Robert Ball. Ball worked in India for twenty years before returning to take up a position in Ireland.

Life and wo ...

...

: 'Please tell Waterhouse to order for the Asiatic, Severtzov's ''Turkestanskie Jevotnie'' immediately, if it is not at the Indian Museum. If they do not like ordering it, order it for myself through Truebner without delay. Do not forget, please.'

A partial list of his publications on birds include

* Stoliczka, F. (1873): Letters to the Editor. Stray Feathers. 1(5):425-427.

* Stoliczka, F. (1874): Letters to the Editor. Stray Feathers. 2(4&5):461-463.

* Stoliczka, F. (1874): Letters to the Editor. Stray Feathers. 2(4&5):463-465.

* Stoliczka, F. (1875): The avifauna of Kashgar in winter. Stray Feathers. 3(1,2&3):215-220.

* Stoliczka, F. (1872): Notice of the mammals and birds inhabiting Kachh utch Jour. Asiatic Soc. Bengal 41(2):211-258.

* Stoliczka, F. (1868): Ornithological observations in the Sutlej valley, N.W. Himalayas. Jour. Asiatic Soc. Bengal 37(2):1-70.

Herpetological contributions

In the scientific field ofherpetology

Herpetology (from Greek ἑρπετόν ''herpetón'', meaning "reptile" or "creeping animal") is the branch of zoology concerned with the study of amphibians (including frogs, toads, salamanders, newts, and caecilians (gymnophiona)) and rept ...

Stoliczka described many new species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

of amphibians

Amphibians are four-limbed and ectothermic vertebrates of the class Amphibia. All living amphibians belong to the group Lissamphibia. They inhabit a wide variety of habitats, with most species living within terrestrial, fossorial, arbore ...

and reptiles

Reptiles, as most commonly defined are the animals in the Class (biology), class Reptilia ( ), a paraphyletic grouping comprising all sauropsid, sauropsids except birds. Living reptiles comprise turtles, crocodilians, Squamata, squamates (lizar ...

, and several species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

and a genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus com ...

have been named in his honor by other herpetologist

Herpetology (from Greek ἑρπετόν ''herpetón'', meaning "reptile" or "creeping animal") is the branch of zoology concerned with the study of amphibians (including frogs, toads, salamanders, newts, and caecilians (gymnophiona)) and rept ...

s.

Taxon described by him

*See :Taxa named by Ferdinand StoliczkaEponymous species and subspecies

Some of the species and subspecies named after Stoliczka are listed below. Not all names may be currently valid.Taxon named in his honor

*The snake genus '' Stoliczkia'' ("Stoliczka", p. 255). *The ammonite genus '' Stoliczkaia'' *The nursery web spider genus '' Stoliczka'' * Ladakh banded apollo, '' Parnassius stoliczkanus'' C. & R. Felder 1864 * Orange clouded yellow, ''Colias stoliczkana

''Colias stoliczkana'', the orange clouded yellow, is a small butterfly of the family Pieridae, that is, the yellows and whites, that is found in India.

See also

*Pieridae

*List of butterflies of India

*List of butterflies of India (Pieridae)

R ...

''

*Stoliczka's crab spider, '' Thomisus stoliczka''

*Stoliczka's barb, ''Pethia stoliczkana

''Pethia stoliczkana'' is a freshwater tropical cyprinid fish native to the upper Mekong, Salwen, Irrawaddy, Meklong and upper Charo Phraya basins in the countries of Nepal, India, Pakistan, Myanmar, Bangladesh, Laos, Thailand, China and ...

''

*Frontier bow-fingered gecko, '' Altiphylax stoliczkai''

*Stoliczka's loach, ''Triplophysa stoliczkai

The Tibetan stone loach (''Triplophysa stolickai'') is a species of ray-finned fish in the family Nemacheilidae. The specific name is sometimes spelled ''stoliczkae'' but the original spelling used by Steindachner is ''stoličkai''.Wu, Y.-Y., Sun ...

'' ( Steindachner, 1866)

* Stoliczka's bushchat, '' Saxicola macrorhyncha''

*Stoliczka's stripe-necked snake, '' Liopeltis stoliczkae''

*Stoliczka's tawny cat snake, ''Boiga ochracea stoliczkae

''Boiga'' is a large genus of rear-fanged, mildly venomous snakes, known commonly as cat-eyed snakes or simply cat snakes, in the family Colubridae. Species of the genus ''Boiga'' are native to southeast Asia, India, and Australia, but due t ...

''

*Stoliczka's treecreeper, ''Certhia nipalensis

The rusty-flanked treecreeper (''Certhia nipalensis'') or the Nepal treecreeper is a species of bird in the family Certhiidae.

It is found in northern India, Nepal, Bhutan and western Yunnan.

Its natural habitats are boreal forests and temperate ...

''

*Stoliczka's trident bat, '' Aselliscus stoliczkanus''

*Stoliczka's mountain vole, '' Alticola stoliczkanus''

*Mongolia rock agama, ''Paralaudakia stoliczkana

''Paralaudakia stoliczkana'' (common name Mongolia rock agama) is a species of lizard in the family Agamidae. The species is native to Xinjiang and Gansu provinces in China, the western parts of Mongolia, and to Kyrgyzstan. www.reptile-database. ...

''

See also

* Stoliczka Island (Остров Столичка)References

Other sources

* Kolmas, Josef (1982) Ferdinand Stoliczka (1838–1874) the life and work of the Czech explorer in India and high Asia. Arbeitskreis Fur Tibetische und Buddhistische Studien Universitat Wien (Vienna) *External links

Herbert Giess, Early Modern European Explorers at the Mountain Jade Quarries in the Kun Lun Mountains in Xinjiang, China

Genera proposed by Stoliczka

(1871) Paleontologia Indica. Cretaceous fauna of southern India. Volume 3

{{DEFAULTSORT:Stoliczka, Ferdinand 1838 births 1874 deaths Austrian ornithologists Austrian paleontologists Austrian lepidopterists Charles University alumni Czech ornithologists Czech paleontologists Czech entomologists Czech lepidopterists Moravian-German people Austrian people of Czech descent Explorers of Central Asia Explorers of the Himalayas People from Kroměříž