In the 1700's to early 1800's

New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

did allow Women the right to vote before the passing of the

19th Amendment, but in 1807 the state restricted the right to vote to "...tax-paying, white male citizens..."

Women's

legal right

Some philosophers distinguish two types of rights, natural rights and legal rights.

* Natural rights are those that are not dependent on the laws or customs of any particular culture or government, and so are ''universal'', ''fundamental right ...

to vote was established in the United States over the course of more than half a century, first in various

states and localities, sometimes on a limited basis, and then nationally in 1920 with the passing of the

19th Amendment.

The demand for

women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

began to gather strength in the 1840s, emerging from the broader movement for

women's rights

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countries, ...

. In 1848, the

Seneca Falls Convention

The Seneca Falls Convention was the first women's rights convention. It advertised itself as "a convention to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of woman".Wellman, 2004, p. 189 Held in the Wesleyan Methodist Church ...

, the first women's rights convention, passed a resolution in favor of women's suffrage despite opposition from some of its organizers, who believed the idea was too extreme.

By the time of the first

National Women's Rights Convention

The National Women's Rights Convention was an annual series of meetings that increased the visibility of the early women's rights movement in the United States. First held in 1850 in Worcester, Massachusetts, the National Women's Rights Convention ...

in 1850, however, suffrage was becoming an increasingly important aspect of the movement's activities.

The first national

suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in representative democracy, public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally i ...

organizations were established in 1869 when two competing organizations were formed, one led by

Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony (born Susan Anthony; February 15, 1820 – March 13, 1906) was an American social reformer and women's rights activist who played a pivotal role in the women's suffrage movement. Born into a Quaker family committed to so ...

and

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (November 12, 1815 – October 26, 1902) was an American writer and activist who was a leader of the women's rights movement in the U.S. during the mid- to late-19th century. She was the main force behind the 1848 Seneca ...

and the other by

Lucy Stone

Lucy Stone (August 13, 1818 – October 18, 1893) was an American orator, abolitionist and suffragist who was a vocal advocate for and organizer promoting rights for women. In 1847, Stone became the first woman from Massachusetts to earn a colle ...

and

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (September 24, 1825 – February 22, 1911) was an American Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, suffragist, poet, Temperance movement, temperance activist, teacher, public speaker, and writer. Beginning in 1 ...

. After years of rivalry, they merged in 1890 as the

National American Woman Suffrage Association

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was an organization formed on February 18, 1890, to advocate in favor of women's suffrage in the United States. It was created by the merger of two existing organizations, the National ...

(NAWSA) with Anthony as its leading force. The

Women's Christian Temperance Union

The Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) is an international temperance organization, originating among women in the United States Prohibition movement. It was among the first organizations of women devoted to social reform with a program th ...

(WCTU), which was the largest women's organization at that time, was established in 1873 and also pursued women's suffrage, giving a huge boost to the movement.

Hoping that the

U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

would rule that

women

A woman is an adult female human. Prior to adulthood, a female human is referred to as a girl (a female child or Adolescence, adolescent). The plural ''women'' is sometimes used in certain phrases such as "women's rights" to denote female hum ...

had a constitutional right to vote, suffragists made several attempts to vote in the early 1870s and then filed

lawsuits

-

A lawsuit is a proceeding by a party or parties against another in the civil court of law. The archaic term "suit in law" is found in only a small number of laws still in effect today. The term "lawsuit" is used in reference to a civil actio ...

when they were turned away. Anthony actually succeeded in voting in 1872 but was arrested for that act and found guilty in a widely publicized trial that gave the movement fresh momentum. After the

Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

ruled against them in the 1875 case ''

Minor v. Happersett

''Minor v. Happersett'', 88 U.S. (21 Wall.) 162 (1875), is a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that, while women are no less citizens than men are, citizenship does not confer a right to vote, and therefore state laws barri ...

'', suffragists began the decades-long campaign for an amendment to the

U.S. Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the natio ...

that would

enfranchise

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

women. Much of the movement's energy, however, went toward working for suffrage on a state-by-state basis. These efforts included pursuing officeholding rights separately in an effort to bolster their argument in favor of voting rights.

The first state to grant women the right to vote had been Wyoming, in 1869, followed by Utah in 1870, Colorado in 1893, Idaho in 1896, Washington in 1910, California in 1911, Oregon and Arizona in 1912, Montana in 1914, North Dakota, New York, and Rhode Island in 1917, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Michigan in 1918.

The efforts of

Emma Smith DeVoe

Emma Smith DeVoe (August 22, 1848 – September 3, 1927) was an American women suffragist in the early twentieth century, changing the face of politics for both women and men alike. When she died, the Tacoma News Tribune called her Washington s ...

were crucial to obtaining suffrage in Idaho and later Washington. She also founded the National Council of Women Voters, with the five western equal suffrage states (Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, Idaho, and Washington) as the members. The purpose was to help other states gain suffrage, to educate women for political action, and to improve the station of women in politics, society, and economics. Some historians regard this as the prototype for the

National League of Women Voters

The League of Women Voters (LWV or the League) is a nonprofit, nonpartisan political organization in the United States. Founded in 1920, its ongoing major activities include registering voters, providing voter information, and advocating for vot ...

.

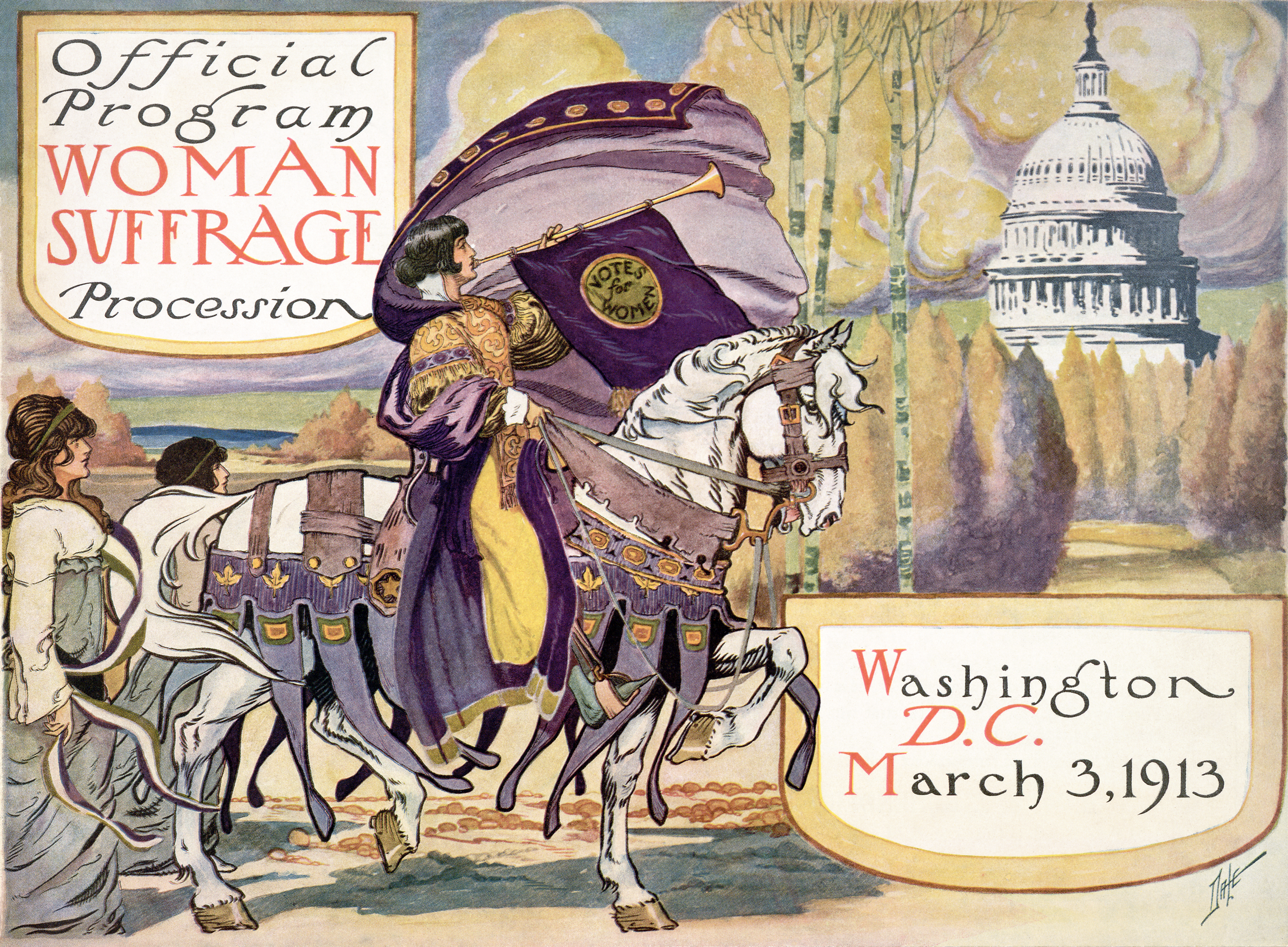

In 1916

Alice Paul

Alice Stokes Paul (January 11, 1885 – July 9, 1977) was an American Quaker, suffragist, feminist, and women's rights activist, and one of the main leaders and strategists of the campaign for the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ...

formed the

National Woman's Party

The National Woman's Party (NWP) was an American women's political organization formed in 1916 to fight for women's suffrage. After achieving this goal with the 1920 adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, the NW ...

(NWP), a group focused on the passage of a national suffrage amendment. Over 200 NWP supporters, the

Silent Sentinels

The Silent Sentinels, also known as the Sentinels of Liberty, were a group of over 2,000 women in favor of women's suffrage organized by Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party, who protested in front of the White House during Woodrow Wilson's ...

, were arrested in 1917 while picketing the

White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

, some of whom went on

hunger strike

A hunger strike is a method of non-violent resistance in which participants fast as an act of political protest, or to provoke a feeling of guilt in others, usually with the objective to achieve a specific goal, such as a policy change. Most ...

and endured

forced feeding

Force-feeding is the practice of feeding a human or animal against their will. The term ''gavage'' (, , ) refers to supplying a substance by means of a small plastic feeding tube passed through the nose ( nasogastric) or mouth (orogastric) into t ...

after being sent to prison. Under the leadership of

Carrie Chapman Catt

Carrie Chapman Catt (; January 9, 1859 Fowler, p. 3 – March 9, 1947) was an American women's suffrage leader who campaigned for the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which gave U.S. women the right to vote in 1920. Catt ...

, the two-million-member NAWSA also made a national suffrage amendment its top priority. After a hard-fought series of votes in the U.S. Congress and in state legislatures, the

Nineteenth Amendment became part of the U.S. Constitution on August 18, 1920. It states, "The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex."

National history

Early voting activity

Lydia Taft

Lydia Taft (née Chapin; February 2, 1712November 9, 1778) was the first woman known to legally vote in colonial America. This occurred at a town meeting in the New England town of Uxbridge in Massachusetts Colony, on October 30, 1756.

Early lif ...

(1712–1778), a wealthy widow, was allowed to vote in town meetings in

Uxbridge, Massachusetts

Uxbridge is a town in Worcester County, Massachusetts first colonized in 1662 and incorporated in 1727. It was originally part of the town of Mendon, MA, Mendon, and named for the Marquess of Anglesey, Earl of Uxbridge. The town is located south ...

in 1756.

No other women in the colonial era are known to have voted.

The

New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

constitution of 1776 enfranchised all adult inhabitants who owned a specified amount of property. Laws enacted in 1790 and 1797 referred to voters as "he or she", and women regularly voted. A law passed in 1807, however, excluded women from voting in that state.

Kentucky passed the first statewide woman suffrage law in the antebellum era (since New Jersey revoked their woman suffrage rights in 1807) in 1838 – allowing voting by any widow or ''feme sole'' (legally, the head of household) over 21 who resided in and owned property subject to taxation for the new county "common school" system. This partial suffrage rights for women was not expressed as for whites only.

Emergence of the women's rights movement

The demand for women's suffrage

emerged as part of the broader movement for women's rights. In the UK in 1792

Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft (, ; 27 April 1759 – 10 September 1797) was a British writer, philosopher, and advocate of women's rights. Until the late 20th century, Wollstonecraft's life, which encompassed several unconventional personal relationsh ...

wrote a pioneering book called ''

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

''A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects'' (1792), written by British philosopher and women's rights advocate Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797), is one of the earliest works of feminist philosoph ...

''.

In Boston in 1838

Sarah Grimké

Sarah (born Sarai) is a biblical matriarch and prophetess, a major figure in Abrahamic religions. While different Abrahamic faiths portray her differently, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam all depict her character similarly, as that of a pi ...

published ''The Equality of the Sexes and the Condition of Women,'' which was widely circulated.

In 1845

Margaret Fuller

Sarah Margaret Fuller (May 23, 1810 – July 19, 1850), sometimes referred to as Margaret Fuller Ossoli, was an American journalist, editor, critic, translator, and women's rights advocate associated with the American transcendentalism movemen ...

published ''

Woman in the Nineteenth Century

''Woman in the Nineteenth Century'' is a book by American journalist, editor, and women's rights advocate Margaret Fuller. Originally published in July 1843 in ''The Dial'' magazine as "The Great Lawsuit. Man versus Men. Woman versus Women", it w ...

'', a key document in American

feminism

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

that first appeared in serial form in 1839 in ''

The Dial

''The Dial'' was an American magazine published intermittently from 1840 to 1929. In its first form, from 1840 to 1844, it served as the chief publication of the Transcendentalists. From the 1880s to 1919 it was revived as a political review and ...

'', a

transcendentalist journal that Fuller edited.

Significant barriers had to be overcome, however, before a campaign for women's suffrage could develop significant strength. One barrier was strong opposition to women's involvement in public affairs, a practice that was not fully accepted even among reform activists. Only after fierce debate were women accepted as members of the

American Anti-Slavery Society

The American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS; 1833–1870) was an abolitionist society founded by William Lloyd Garrison and Arthur Tappan. Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave, had become a prominent abolitionist and was a key leader of this society ...

at its convention of 1839, and the organization split at its next convention when women were appointed to committees.

Opposition was especially strong against the idea of women speaking to audiences of both men and women.

Frances Wright

Frances Wright (September 6, 1795 – December 13, 1852), widely known as Fanny Wright, was a Scottish-born lecturer, writer, freethinker, feminist, utopian socialist, abolitionist, social reformer, and Epicurean philosopher, who became a ...

, a

Scottish

Scottish usually refers to something of, from, or related to Scotland, including:

*Scottish Gaelic, a Celtic Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family native to Scotland

*Scottish English

*Scottish national identity, the Scottish ide ...

woman, was subjected to sharp criticism for delivering public lectures in the U.S. in 1826 and 1827. When the

Grimké sisters

Sarah Moore Grimké (1792–1873) and Angelina Emily GrimkéUnited States. National Park Service. "Grimke Sisters." U.S. Department of the Interior, October 8, 2014. Accessed:October 14, 2014. (1805–1879), known as the Grimké sisters, were th ...

, who had been born into a slave-holding family in

South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, spoke against slavery throughout the northeast in the mid-1830s, the ministers of the

Congregational Church

Congregational churches (also Congregationalist churches or Congregationalism) are Protestant churches in the Calvinist tradition practising congregationalist church governance, in which each congregation independently and autonomously runs its ...

, a major force in that region, published a statement condemning their actions. Despite the disapproval, in 1838

Angelina Grimké

Angelina Emily Grimké Weld (February 20, 1805 – October 26, 1879) was an American abolitionist, political activist, women's rights advocate, and supporter of the women's suffrage movement. She and her sister Sarah Moore Grimké were c ...

spoke against slavery before the Massachusetts legislature, the first woman in the U.S. to speak before a legislative body.

Other women began to give public speeches, especially in opposition to slavery and in support of

women's rights

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countries, ...

. Early female speakers included

Ernestine Rose

Ernestine Louise Rose (January 13, 1810 – August 4, 1892) was a suffragist, abolitionist, and freethinker who has been called the “first Jewish feminist.” Her career spanned from the 1830s to the 1870s, making her a contemporary to the more ...

, a Jewish immigrant from Poland; Lucretia Mott, a

Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belie ...

minister and

abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

; and

Abby Kelley Foster

Abby Kelley Foster (January 15, 1811 – January 14, 1887) was an American abolitionist and radical social reformer active from the 1830s to 1870s. She became a fundraiser, lecturer and committee organizer for the influential American Anti-Sl ...

, a Quaker abolitionist.

Toward the end of the 1840s

Lucy Stone

Lucy Stone (August 13, 1818 – October 18, 1893) was an American orator, abolitionist and suffragist who was a vocal advocate for and organizer promoting rights for women. In 1847, Stone became the first woman from Massachusetts to earn a colle ...

launched her career as a public speaker, soon becoming the most famous female lecturer.

Supporting both the abolitionist and women's rights movements, Stone played a major role in reducing the prejudice against women speaking in public.

Opposition remained strong, however. A regional women's rights convention in Ohio in 1851 was disrupted by male opponents.

Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth (; born Isabella Baumfree; November 26, 1883) was an American abolitionist of New York Dutch heritage and a women's rights activist. Truth was born into slavery in Swartekill, New York, but escaped with her infant daughter to f ...

, who delivered her famous speech "

Ain't I a Woman?

"Ain't I a Woman?" is a speech, delivered extemporaneously, by Sojourner Truth (1797–1883), born into slavery in New York State. Some time after gaining her freedom in 1827, she became a well known anti-slavery speaker. Her speech was deliver ...

" at the convention, directly addressed some of this opposition in her speech.

The

National Women's Rights Convention

The National Women's Rights Convention was an annual series of meetings that increased the visibility of the early women's rights movement in the United States. First held in 1850 in Worcester, Massachusetts, the National Women's Rights Convention ...

in 1852 was also disrupted, and mob action at the 1853 convention came close to violence.

The World's Temperance Convention in New York City in 1853 bogged down for three days in a dispute about whether women would be allowed to speak there.

Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony (born Susan Anthony; February 15, 1820 – March 13, 1906) was an American social reformer and women's rights activist who played a pivotal role in the women's suffrage movement. Born into a Quaker family committed to so ...

, a leader of the suffrage movement, later said, "No advanced step taken by women has been so bitterly contested as that of speaking in public. For nothing which they have attempted, not even to secure the suffrage, have they been so abused, condemned and antagonized."

Laws that sharply restricted the independent activity of married women also created barriers to the campaign for women's suffrage. According to

William Blackstone

Sir William Blackstone (10 July 1723 – 14 February 1780) was an English jurist, judge and Tory politician of the eighteenth century. He is most noted for writing the ''Commentaries on the Laws of England''. Born into a middle-class family i ...

's ''

Commentaries on the Laws of England

The ''Commentaries on the Laws of England'' are an influential 18th-century treatise on the common law of England by Sir William Blackstone, originally published by the Clarendon Press at Oxford, 1765–1770. The work is divided into four volume ...

'', an authoritative commentary on the

English common law

English law is the common law legal system of England and Wales, comprising mainly criminal law and civil law, each branch having its own courts and procedures.

Principal elements of English law

Although the common law has, historically, bee ...

on which the American legal system is modeled, "by marriage, the husband and wife are one person in law: that is, the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage", referring to the legal doctrine of

coverture

Coverture (sometimes spelled couverture) was a legal doctrine in the English common law in which a married woman's legal existence was considered to be merged with that of her husband, so that she had no independent legal existence of her own. U ...

that was introduced to England by the

Normans

The Normans (Norman language, Norman: ''Normaunds''; french: Normands; la, Nortmanni/Normanni) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norsemen, Norse Viking settlers and indigenous West Fran ...

in the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

. In 1862 the Chief Justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court denied a divorce to a woman whose husband had horsewhipped her, saying, "The law gives the husband power to use such a degree of force necessary to make the wife behave and know her place."

Married women in many states could not legally sign contracts, which made it difficult for them to arrange for convention halls, printed materials and other things needed by the suffrage movement.

Restrictions like these were overcome in part by the passage of

married women's property laws in several states, supported in some cases by wealthy fathers who did not want their daughters' inheritance to fall under the complete control of their husbands.

Sentiment in favor of women's rights was strong within the radical wing of the abolitionist movement.

William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was a prominent American Christian, abolitionist, journalist, suffragist, and social reformer. He is best known for his widely read antislavery newspaper '' The Liberator'', which he found ...

, the leader of the

American Anti-Slavery Society

The American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS; 1833–1870) was an abolitionist society founded by William Lloyd Garrison and Arthur Tappan. Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave, had become a prominent abolitionist and was a key leader of this society ...

, said "I doubt whether a more important movement has been launched touching the destiny of the race, than this in regard to the equality of the sexes".

The abolitionist movement, however, attracted only about one per cent of the population at that time, and radical abolitionists were only one part of that movement.

Early backing for women's suffrage

The

New York State Constitutional Convention of 1846 received petitions in support of women's suffrage from residents of at least three counties.

Several members of the radical wing of the abolitionist movement supported suffrage. In 1846,

Samuel J. May

Samuel Joseph May (September 12, 1797 – July 1, 1871) was an American reformer during the nineteenth century who championed education, women's rights, and abolition of slavery. May argued on behalf of all working people that the rights of h ...

, a

Unitarian minister and radical abolitionist, vigorously supported women's suffrage in a sermon that was later circulated as the first in a series of women's rights tracts.

In 1846, the Liberty League, an offshoot of the abolitionist

Liberty Party, petitioned Congress to enfranchise women.

A convention of the

Liberty Party in

Rochester, New York

Rochester () is a City (New York), city in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York, the county seat, seat of Monroe County, New York, Monroe County, and the fourth-most populous in the state after New York City, Buffalo, New York, Buffalo, ...

in May 1848 approved a resolution calling for "universal suffrage in its broadest sense, including women as well as men."

Gerrit Smith

Gerrit Smith (March 6, 1797 – December 28, 1874), also spelled Gerritt Smith, was a leading American social reformer, abolitionist, businessman, public intellectual, and philanthropist. Married to Ann Carroll Fitzhugh, Smith was a candidat ...

, its candidate for president, delivered a speech shortly afterwards at the National Liberty Convention in

Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second-largest city in the U.S. state of New York (behind only New York City) and the seat of Erie County. It is at the eastern end of Lake Erie, at the head of the Niagara River, and is across the Canadian border from South ...

that elaborated on his party's call for women's suffrage.

Lucretia Mott

Lucretia Mott (''née'' Coffin; January 3, 1793 – November 11, 1880) was an American Quaker, abolitionist, women's rights activist, and social reformer. She had formed the idea of reforming the position of women in society when she was amongs ...

was suggested as the party's vice-presidential candidate—the first time that a woman had been proposed for federal executive office in the U.S.—and she received five votes from delegates at that convention.

Early women's rights conventions

Women's suffrage was not a major topic within the women's rights movement at that point. Many of its activists were aligned with the

Garrisonian

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was a prominent American Christian, abolitionist, journalist, suffragist, and social reformer. He is best known for his widely read antislavery newspaper '' The Liberator'', which he foun ...

wing of the abolitionist movement, which believed that activists should avoid political activity and focus instead on convincing others of their views with "moral suasion".

Many were Quakers whose traditions barred both men and women from participation in secular political activity.

A series of women's rights conventions did much to alter these attitudes.

Seneca Falls convention

The first women's rights convention was the

Seneca Falls Convention

The Seneca Falls Convention was the first women's rights convention. It advertised itself as "a convention to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of woman".Wellman, 2004, p. 189 Held in the Wesleyan Methodist Church ...

, a regional event held on July 19 and 20, 1848, in

Seneca Falls in the

Finger Lakes

The Finger Lakes are a group of eleven long, narrow, roughly north–south lakes located south of Lake Ontario in an area called the ''Finger Lakes region'' in New York, in the United States. This region straddles the northern and transitional ...

region of

New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

.

Five women called the convention, four of whom were

Quaker social activists, including the well-known

Lucretia Mott

Lucretia Mott (''née'' Coffin; January 3, 1793 – November 11, 1880) was an American Quaker, abolitionist, women's rights activist, and social reformer. She had formed the idea of reforming the position of women in society when she was amongs ...

. The fifth was

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (November 12, 1815 – October 26, 1902) was an American writer and activist who was a leader of the women's rights movement in the U.S. during the mid- to late-19th century. She was the main force behind the 1848 Seneca ...

, who had discussed the need to organize for women's rights with Mott several years earlier.

Stanton, who came from a family that was deeply involved in politics, became a major force in convincing the women's movement that political pressure was crucial to its goals, and that the right to vote was a key weapon.

An estimated 300 women and men attended this two-day event, which was widely noted in the press.

The only resolution that was not adopted unanimously by the convention was the one demanding women's right to vote, which was introduced by Stanton. When her husband, a well-known social reformer, learned that she intended to introduce this resolution, he refused to attend the convention and accused her of acting in a way that would turn the proceedings into a farce. Lucretia Mott, the main speaker, was also disturbed by the proposal. The resolution was adopted only after

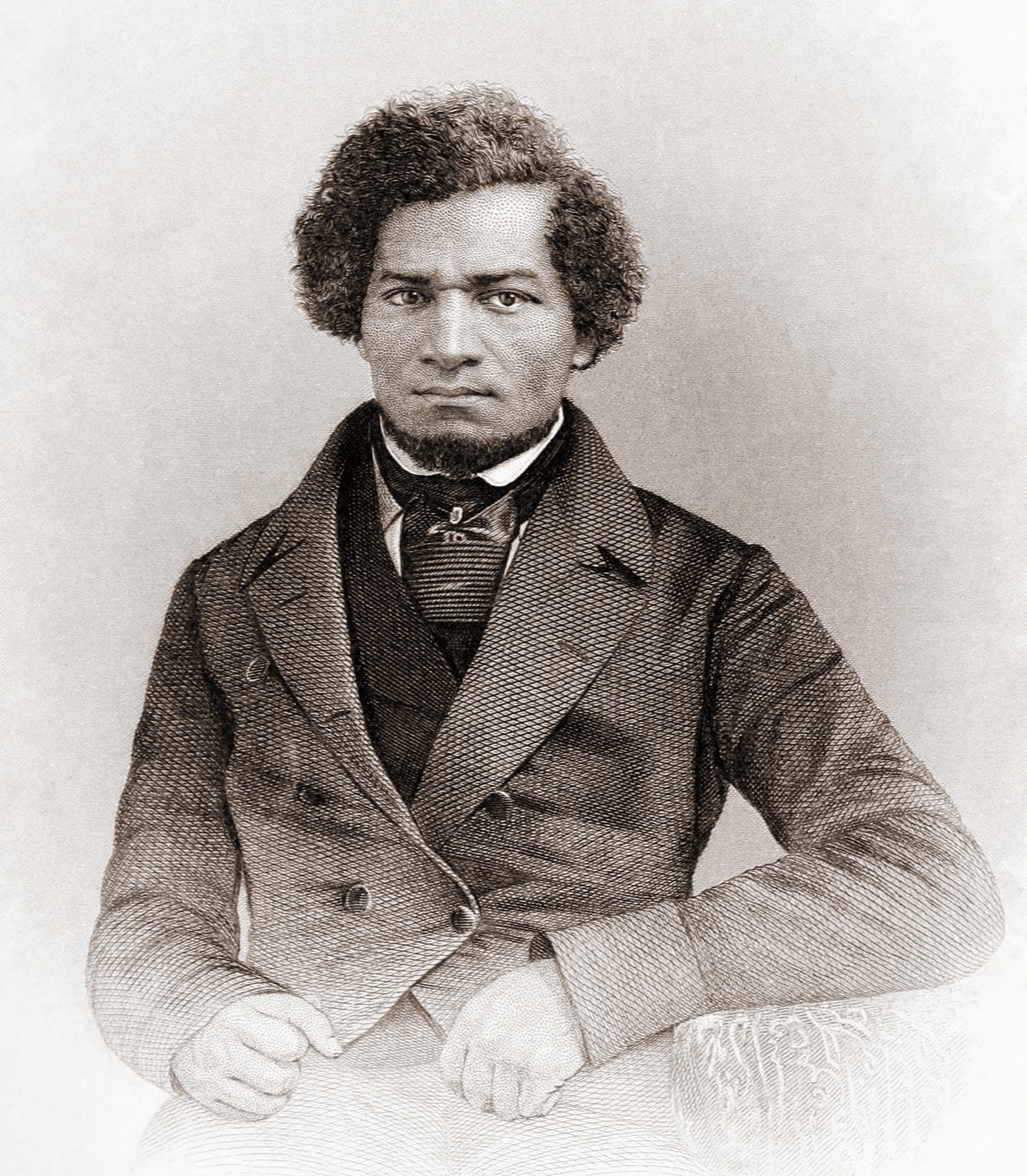

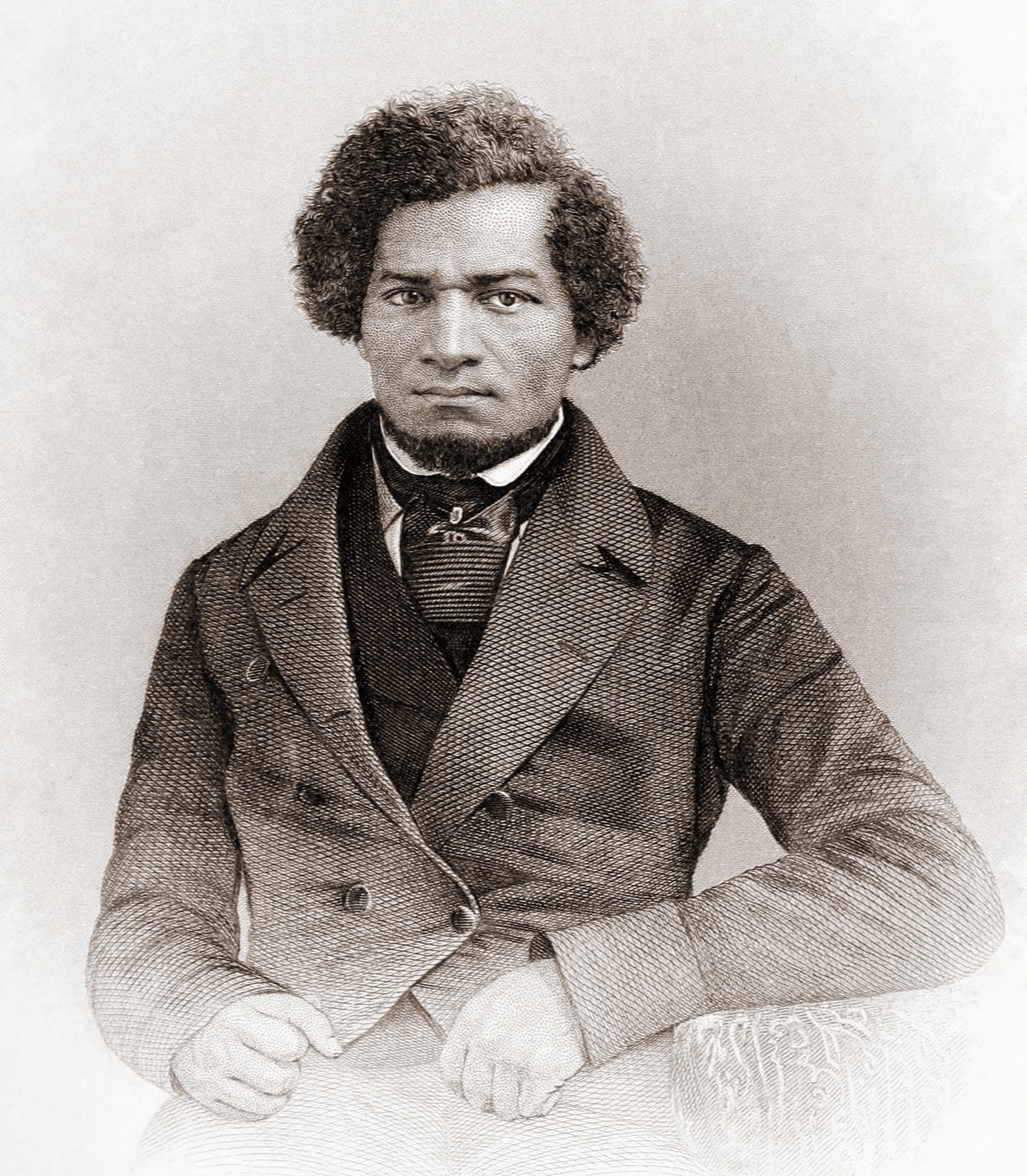

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

, an abolitionist leader and a former slave, gave it his strong support.

The convention's

Declaration of Sentiments

The Declaration of Sentiments, also known as the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments, is a document signed in 1848 by 68 women and 32 men—100 out of some 300 attendees at the first women's rights convention to be organized by women. Held in Sen ...

, which was written primarily by Stanton, expressed an intent to build a women's rights movement, and it included a list of grievances, the first two of which protested the lack of women's suffrage. The grievances which were aimed at the United States government "demanded government reform and changes in male roles and behaviors that promoted inequality for women."

This convention was followed two weeks later by the

Rochester Women's Rights Convention of 1848

The Rochester Women's Rights Convention of 1848 met on August 2, 1848 in Rochester, New York. Many of its organizers had participated in the Seneca Falls Convention, the first women's rights convention, two weeks earlier in Seneca Falls, a small ...

, which featured many of the same speakers and likewise voted to support women's suffrage. It was the first women's rights convention to be chaired by a woman, a step that was considered to be radical at the time. That meeting was followed by the

Ohio Women's Convention at Salem in 1850 The Ohio Women's Convention at Salem in 1850 met on April 19–20, 1850 in Salem, Ohio, a center for reform activity. It was the third in a series of women's rights conventions that began with the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848. It was the first o ...

, the first women's rights convention to be organized on a statewide basis, which also endorsed women's suffrage.

National conventions

The first in a series of

National Women's Rights Convention

The National Women's Rights Convention was an annual series of meetings that increased the visibility of the early women's rights movement in the United States. First held in 1850 in Worcester, Massachusetts, the National Women's Rights Convention ...

s was held in

Worcester, Massachusetts

Worcester ( , ) is a city and county seat of Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. Named after Worcester, England, the city's population was 206,518 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the second-List of cities i ...

on October 23–24, 1850, at the initiative of

Lucy Stone

Lucy Stone (August 13, 1818 – October 18, 1893) was an American orator, abolitionist and suffragist who was a vocal advocate for and organizer promoting rights for women. In 1847, Stone became the first woman from Massachusetts to earn a colle ...

and

Paulina Wright Davis

Paulina Wright Davis ( Kellogg; August 7, 1813 – August 24, 1876) was an American abolitionist, suffragist, and educator. She was one of the founders of the New England Woman Suffrage Association.

Early life

Davis was born in Bloomfield, New ...

.

National conventions were held afterwards almost every year through 1860, when the

Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

(1861–1865) interrupted the practice.

Suffrage was a preeminent goal of these conventions, no longer the controversial issue it had been at Seneca Falls only two years earlier.

At the first national convention Stone gave a speech that included a call to petition state legislatures for the right of suffrage.

Reports of this convention reached Britain, prompting

Harriet Taylor, soon to be married to philosopher

John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, Member of Parliament (MP) and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of classical liberalism, he contributed widely to ...

, to write an essay called "The Enfranchisement of Women," which was published in the ''

Westminster Review

The ''Westminster Review'' was a quarterly British publication. Established in 1823 as the official organ of the Philosophical Radicals, it was published from 1824 to 1914. James Mill was one of the driving forces behind the liberal journal until ...

''. Heralding the women's movement in the U.S., Taylor's essay helped to initiate a similar movement in Britain. Her essay was reprinted as a women's rights tract in the U.S. and was sold for decades.

Wendell Phillips

Wendell Phillips (November 29, 1811 – February 2, 1884) was an American abolitionist, advocate for Native Americans, orator, and attorney.

According to George Lewis Ruffin, a Black attorney, Phillips was seen by many Blacks as "the one whi ...

, a prominent abolitionist and women's rights advocate, delivered a speech at the second national convention in 1851 called "Shall Women Have the Right to Vote?" Describing women's suffrage as the cornerstone of the women's movement, it was later circulated as a women's rights tract.

Several of the women who played leading roles in the national conventions, especially Stone, Anthony and Stanton, were also leaders in establishing women's suffrage organizations after the Civil War.

They also included the demand for suffrage as part of their activities during the 1850s. In 1852 Stanton advocated women's suffrage in a speech at the New York State Temperance Convention.

In 1853 Stone became the first woman to appeal for women's suffrage before a body of lawmakers when she addressed the Massachusetts Constitutional Convention.

In 1854 Anthony organized a petition campaign in New York State that included the demand for suffrage. It culminated in a women's rights convention in the state capitol and a speech by Stanton before the state legislature.

In 1857 Stone refused to pay taxes on the grounds that women were taxed without being able to vote on tax laws. The

constable

A constable is a person holding a particular office, most commonly in criminal law enforcement. The office of constable can vary significantly in different jurisdictions. A constable is commonly the rank of an officer within the police. Other peop ...

sold her household goods at auction until enough money had been raised to pay her tax bill.

The women's rights movement was loosely structured during this period, with few state organizations and no national organization other than a coordinating committee that arranged the annual national conventions.

Much of the organizational work for these conventions was performed by Stone, the most visible leader of the movement during this period.

At the national convention in 1852, a proposal was made to form a national women's rights organization, but the idea was dropped after fears were voiced that such a move would create cumbersome machinery and lead to internal divisions.

Anthony–Stanton collaboration

Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony (born Susan Anthony; February 15, 1820 – March 13, 1906) was an American social reformer and women's rights activist who played a pivotal role in the women's suffrage movement. Born into a Quaker family committed to so ...

and

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (November 12, 1815 – October 26, 1902) was an American writer and activist who was a leader of the women's rights movement in the U.S. during the mid- to late-19th century. She was the main force behind the 1848 Seneca ...

met in 1851 and soon became close friends and co-workers.

Their decades-long collaboration was pivotal for the suffrage movement and contributed significantly to the broader struggle for women's rights, which Stanton called "the greatest revolution the world has ever known or ever will know."

They had complementary skills: Anthony excelled at organizing while Stanton had an aptitude for intellectual matters and writing. Stanton, who was homebound with several children during this period, wrote speeches that Anthony delivered to meetings that she herself organized.

Together they developed a sophisticated movement in New York State,

but their work at this time dealt with women's issues in general, not specifically suffrage. Anthony, who eventually became the person most closely associated in the public mind with women's suffrage,

later said "I wasn't ready to vote, didn't want to vote, but I did want equal pay for equal work."

In the period just before the Civil War, Anthony gave priority to anti-slavery work over her work for the women's movement.

Women's Loyal National League

Over Anthony's objections, leaders of the movement agreed to suspend women's rights activities during the Civil War in order to focus on the abolition of slavery.

In 1863 Anthony and Stanton organized the

Women's Loyal National League

The Women's Loyal National League, also known as the Woman's National Loyal League and other variations of that name, was formed on May 14, 1863, to campaign for an amendment to the U.S. Constitution that would abolish slavery. It was organized b ...

, the first national women's political organization in the U.S.

It collected nearly 400,000 signatures on petitions to abolish slavery in the largest petition drive in the nation's history up to that time.

[Venet (1991)]

p. 148

/ref>

Although it was not a suffrage organization, the League made it clear that it stood for political equality for women,

and it indirectly advanced that cause in several ways. Stanton reminded the public that petitioning was the only political tool available to women at a time when only men were allowed to vote.

The League's impressive petition drive demonstrated the value of formal organization to the women's movement, which had traditionally resisted organizational structures,

and it marked a continuation of the shift of women's activism from moral suasion to political action.

Although it was not a suffrage organization, the League made it clear that it stood for political equality for women,

and it indirectly advanced that cause in several ways. Stanton reminded the public that petitioning was the only political tool available to women at a time when only men were allowed to vote.

The League's impressive petition drive demonstrated the value of formal organization to the women's movement, which had traditionally resisted organizational structures,

and it marked a continuation of the shift of women's activism from moral suasion to political action.[

Its 5000 members constituted a widespread network of women activists who gained experience that helped create a pool of talent for future forms of social activism, including suffrage.

]

American Equal Rights Association

The Eleventh National Women's Rights Convention

The National Women's Rights Convention was an annual series of meetings that increased the visibility of the early women's rights movement in the United States. First held in 1850 in Worcester, Massachusetts, the National Women's Rights Convention ...

, the first since the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, was held in 1866, helping the women's rights movement regain the momentum it had lost during the war.

The convention voted to transform itself into the American Equal Rights Association

The American Equal Rights Association (AERA) was formed in 1866 in the United States. According to its constitution, its purpose was "to secure Equal Rights to all American citizens, especially the right of suffrage, irrespective of race, color o ...

(AERA), whose purpose was to campaign for the equal rights of all citizens, especially the right of suffrage.

In addition to Anthony and Stanton, who organized the convention, the leadership of the new organization included such prominent abolitionist and women's rights activists as Lucretia Mott

Lucretia Mott (''née'' Coffin; January 3, 1793 – November 11, 1880) was an American Quaker, abolitionist, women's rights activist, and social reformer. She had formed the idea of reforming the position of women in society when she was amongs ...

, Lucy Stone

Lucy Stone (August 13, 1818 – October 18, 1893) was an American orator, abolitionist and suffragist who was a vocal advocate for and organizer promoting rights for women. In 1847, Stone became the first woman from Massachusetts to earn a colle ...

and Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

. Its drive for universal suffrage

Universal suffrage (also called universal franchise, general suffrage, and common suffrage of the common man) gives the right to vote to all adult citizens, regardless of wealth, income, gender, social status, race, ethnicity, or political stanc ...

, however, was resisted by some abolitionist leaders and their allies in the Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

*Republican Party (Liberia)

* Republican Part ...

, who wanted women to postpone their campaign for suffrage until it had first been achieved for male African Americans. Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and newspaper editor, editor of the ''New-York Tribune''. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congressm ...

, a prominent newspaper editor, told Anthony and Stanton, "This is a critical period for the Republican Party and the life of our Nation... I conjure you to remember that this is 'the negro's hour,' and your first duty now is to go through the State and plead his claims."

They and others, including Lucy Stone, refused to postpone their demands, however, and continued to push for universal suffrage

Universal suffrage (also called universal franchise, general suffrage, and common suffrage of the common man) gives the right to vote to all adult citizens, regardless of wealth, income, gender, social status, race, ethnicity, or political stanc ...

.

In April 1867 Stone and her husband Henry Blackwell opened the AERA campaign in Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the ...

in support of referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

s in that state that would enfranchise

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

both African Americans and women.

Wendell Phillips

Wendell Phillips (November 29, 1811 – February 2, 1884) was an American abolitionist, advocate for Native Americans, orator, and attorney.

According to George Lewis Ruffin, a Black attorney, Phillips was seen by many Blacks as "the one whi ...

, an abolitionist leader who opposed mixing those two causes, surprised and angered AERA workers by blocking the funding that the AERA had expected for their campaign.

After an internal struggle, Kansas Republicans decided to support suffrage for black men only and formed an "Anti-Female Suffrage Committee" to oppose the AERA's efforts.

By the end of summer the AERA campaign had almost collapsed, and its finances were exhausted.

Anthony and Stanton were harshly criticized by Stone and other AERA members for accepting help during the last days of the campaign from George Francis Train

George Francis Train (March 24, 1829 – January 18, 1904) was an American entrepreneur who organized the clipper ship line that sailed around Cape Horn to San Francisco; he also organized the Union Pacific Railroad and the Credit Mobilier in th ...

, a wealthy businessman who supported women's rights. Train antagonized many activists by attacking the Republican Party, which had won the loyalty of many reform activists, and openly disparaging the integrity and intelligence of African Americans.

After the Kansas campaign, the AERA increasingly divided into two wings, both advocating universal suffrage but with different approaches. One wing, whose leading figure was Lucy Stone, was willing for black men to achieve suffrage first, if necessary, and wanted to maintain close ties with the Republican Party and the abolitionist movement. The other, whose leading figures were Anthony and Stanton, insisted that women and black men be enfranchised at the same time and worked toward a politically independent women's movement that would no longer be dependent on abolitionists for financial and other resources.

The acrimonious annual meeting of the AERA in May 1869 signaled the effective demise of the organization, in the aftermath of which two competing woman suffrage organizations were created.

New England Woman Suffrage Association

Partly as a result of the developing split in the women's movement, in 1868 the

Partly as a result of the developing split in the women's movement, in 1868 the New England Woman Suffrage Association The New England Woman Suffrage Association (NEWSA) was established in November 1868 to campaign for the right of women to vote in the U.S. Its principal leaders were Julia Ward Howe, its first president, and Lucy Stone, who later became president. ...

(NEWSA), the first major political organization in the U.S. with women's suffrage as its goal, was formed.

The planners for the NEWSA's founding convention worked to attract Republican support and seated leading Republican politicians, including a U.S. senator, on the speaker's platform.

Amid increasing confidence that the Fifteenth Amendment, which would in effect enfranchise black men, was assured of passage, Lucy Stone, a future president of the NEWSA, showed her preference for enfranchising both women and African Americans by unexpectedly introducing a resolution calling for the Republican Party to "drop its watchword of 'Manhood Suffrage'"

and to support universal suffrage

Universal suffrage (also called universal franchise, general suffrage, and common suffrage of the common man) gives the right to vote to all adult citizens, regardless of wealth, income, gender, social status, race, ethnicity, or political stanc ...

instead. Despite opposition by Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

and others, Stone convinced the meeting to approve the resolution.

Two months later, however, when the Fifteenth Amendment was in danger of becoming stalled in Congress, Stone backed away from that position and declared that "Woman must wait for the Negro."

The Fifteenth Amendment

In May 1869, two days after the final AERA annual meeting, Anthony, Stanton and others formed the National Woman Suffrage Association

The National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) was formed on May 15, 1869, to work for women's suffrage in the United States. Its main leaders were Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. It was created after the women's rights movement spl ...

(NWSA). In November 1869, Lucy Stone

Lucy Stone (August 13, 1818 – October 18, 1893) was an American orator, abolitionist and suffragist who was a vocal advocate for and organizer promoting rights for women. In 1847, Stone became the first woman from Massachusetts to earn a colle ...

, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (September 24, 1825 – February 22, 1911) was an American Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist, suffragist, poet, Temperance movement, temperance activist, teacher, public speaker, and writer. Beginning in 1 ...

, Julia Ward Howe

Julia Ward Howe (; May 27, 1819 – October 17, 1910) was an American author and poet, known for writing the "Battle Hymn of the Republic" and the original 1870 pacifist Mother's Day Proclamation. She was also an advocate for abolitionism ...

, Henry Blackwell and others, many of whom had helped to create the New England Woman Suffrage Association a year earlier, formed the American Woman Suffrage Association

The American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) was a single-issue national organization formed in 1869 to work for women's suffrage in the United States. The AWSA lobbied state governments to enact laws granting or expanding women's right to vote ...

(AWSA). The hostile rivalry between these two organizations created a partisan atmosphere that endured for decades, affecting even professional historians of the women's movement.

The immediate cause for the split was the proposed Fifteenth Amendment to the

The immediate cause for the split was the proposed Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the natio ...

, a reconstruction amendment that would prohibit the denial of suffrage because of race. The original language of the amendment included a clause banning voting discrimination on the basis of sex, but was later removed.[Rakow and Kramarae eds. (2001)]

p. 48

/ref>

Anthony and Stanton also warned that black men, who would gain voting power under the amendment, were overwhelmingly opposed to women's suffrage.

They were not alone in being unsure of black male support for women's suffrage. Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

, a strong supporter of women's suffrage, said, "The race to which I belong have not generally taken the right ground on this question."

Douglass, however, strongly supported the amendment, saying it was a matter of life and death for former slaves. Lucy Stone, who became the AWSA's most prominent leader, supported the amendment but said she believed that suffrage for women would be more beneficial to the country than suffrage for black men.

The AWSA and most AERA members also supported the amendment.

Both wings of the movement were strongly associated with opposition to slavery, but their leaders sometimes expressed views that reflected the racial attitudes of that era. Stanton, for example, believed that a long process of education would be needed before what she called the "lower orders" of former slaves and immigrant workers would be able to participate meaningfully as voters.The Revolution

A revolution is a drastic political change that usually occurs relatively quickly. For revolutions which affect society, culture, and technology more than political systems, see social revolution.

Revolution may also refer to:

Aviation

*Warner ...

'', Stanton wrote, "American women of wealth, education, virtue and refinement, if you do not wish the lower orders of Chinese, Africans, Germans and Irish, with their low ideas of womanhood to make laws for you and your daughters ... demand that women too shall be represented in government."

In another article she made a similar statement while personifying those four ethnic groups as "Patrick and Sambo and Hans and Yung Tung".

Lucy Stone called a suffrage meeting in New Jersey to consider the question, "Shall women alone be omitted in the reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

? Shall hey

Hey or Hey! may refer to:

Music

* Hey (band), a Polish rock band

Albums

* ''Hey'' (Andreas Bourani album) or the title song (see below), 2014

* ''Hey!'' (Julio Iglesias album) or the title song, 1980

* ''Hey!'' (Jullie album) or the title s ...

... be ranked politically below the most ignorant and degraded men?"

Henry Blackwell, Stone's husband and an AWSA officer, published an open letter to Southern legislatures assuring them that if they allowed both blacks and women to vote, "the political supremacy of your white race will remain unchanged" and "the black race would gravitate by the law of nature toward the tropics."

The AWSA aimed for close ties with the Republican Party, hoping that the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment would lead to a Republican push for women's suffrage.

The NWSA, while determined to be politically independent, was critical of the Republicans. Anthony and Stanton wrote a letter to the 1868 Democratic National Convention

The 1868 Democratic National Convention was held at Tammany Hall in New York City between July 4, and July 9, 1868. The first Democratic convention after the conclusion of the American Civil War, the convention was notable for the return of Democr ...

that criticized Republican sponsorship of the Fourteenth Amendment (which granted citizenship to black men but for the first time introduced the word "male" into the Constitution), saying, "While the dominant party has with one hand lifted up two million black men and crowned them with the honor and dignity of citizenship, with the other it has dethroned fifteen million white women—their own mothers and sisters, their own wives and daughters—and cast them under the heel of the lowest orders of manhood."

They urged liberal Democrats to convince their party, which did not have a clear direction at that point, to embrace universal suffrage.

The two organizations had other differences as well. Although each campaigned for suffrage at both the state and national levels, the NWSA tended to work more at the national level and the AWSA more at the state level.

The NWSA initially worked on a wider range of issues than the AWSA, including divorce reform and equal pay for women

Equal pay for equal work is the concept of labour rights that individuals in the same workplace be given equal pay. It is most commonly used in the context of sexual discrimination, in relation to the gender pay gap. Equal pay relates to the full ...

. The NWSA was led by women only while the AWSA included both men and women among its leadership.

Events soon removed much of the basis for the split in the movement. In 1870 debate about the Fifteenth Amendment was made irrelevant when that amendment was officially ratified. In 1872 disgust with corruption in government led to a mass defection of abolitionists and other social reformers from the Republicans to the short-lived Liberal Republican Party.

The rivalry between the two women's groups was so bitter, however, that a merger proved to be impossible until 1890.

New Departure

In 1869 Francis and Virginia Minor

Virginia Louisa Minor (March 27, 1824 – August 14, 1894) was an American women's suffrage activist. She is best remembered as the plaintiff in '' Minor v. Happersett'', an 1875 United States Supreme Court case in which Minor unsuccessfully arg ...

, husband and wife suffragists from Missouri, outlined a strategy that came to be known as the New Departure, which engaged the suffrage movement for several years.

Arguing that the U.S. Constitution implicitly enfranchised women, this strategy relied heavily on Section 1 of the recently adopted Fourteenth Amendment,[ (The name of this article's author i]

here.

which reads, "All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws."

In 1871 the NWSA officially adopted the New Departure strategy, encouraging women to attempt to vote and to file lawsuits if denied that right.

In 1871 the NWSA officially adopted the New Departure strategy, encouraging women to attempt to vote and to file lawsuits if denied that right.spiritualists

Spiritualism is the metaphysical school of thought opposing physicalism and also is the category of all spiritual beliefs/views (in monism and dualism) from ancient to modern. In the long nineteenth century, Spiritualism (when not lowercase) b ...

, nearly 200 women placed their ballots into a separate box and attempted to have them counted, but without success. The AWSA did not officially adopt the New Departure strategy, but Lucy Stone

Lucy Stone (August 13, 1818 – October 18, 1893) was an American orator, abolitionist and suffragist who was a vocal advocate for and organizer promoting rights for women. In 1847, Stone became the first woman from Massachusetts to earn a colle ...

, its leader, attempted to vote in her home town in New Jersey.

In one court case resulting from a lawsuit brought by women who had been prevented from voting, the U.S. District Court in Washington, D.C., ruled that women did not have an implicit right to vote, declaring that, "The fact that the practical working of the assumed right would be destructive of civilization is decisive that the right does not exist."

In 1871 Victoria Woodhull

Victoria Claflin Woodhull, later Victoria Woodhull Martin (September 23, 1838 – June 9, 1927), was an American leader of the women's suffrage movement who ran for President of the United States in the 1872 election. While many historians ...

, a stockbroker, was invited to speak before a committee of Congress, the first woman to do so.Henry Ward Beecher

Henry Ward Beecher (June 24, 1813 – March 8, 1887) was an American Congregationalist clergyman, social reformer, and speaker, known for his support of the Abolitionism, abolition of slavery, his emphasis on God's love, and his 1875 adultery ...

, president of the AWSA, and Elizabeth Tilton, wife of a leading NWSA member.

Beecher's subsequent trial was reported in newspapers across the country, resulting in what one scholar has called "political theater" that badly damaged the reputation of the suffrage movement.

The Supreme Court in 1875 put an end to the New Departure strategy by ruling in ''Minor v. Happersett

''Minor v. Happersett'', 88 U.S. (21 Wall.) 162 (1875), is a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that, while women are no less citizens than men are, citizenship does not confer a right to vote, and therefore state laws barri ...

'' that "the Constitution of the United States does not confer the right of suffrage upon anyone".[ This article also points out that Supreme Court rulings did not establish the connection between citizenship and voting rights until the mid-twentieth century.]

The NWSA decided to pursue the far more difficult strategy of campaigning for a constitutional amendment that would guarantee voting rights for women.

''United States v. Susan B. Anthony''

In a case that generated national controversy, Susan B. Anthony was arrested for violating the Enforcement Act of 1870

The Enforcement Act of 1870, also known as the Civil Rights Act of 1870 or First Ku Klux Klan Act, or Force Act (41st Congress, Sess. 2, ch. 114, , enacted May 31, 1870, effective 1871) was a United States federal law that empowered the President ...

by casting a vote in the 1872 presidential election. At the trial, the judge directed the jury to deliver a guilty verdict. When he asked Anthony, who had not been permitted to speak during the trial, if she had anything to say, she responded with what one historian has called "the most famous speech in the history of the agitation for woman suffrage".[ She called "this high-handed outrage upon my citizen's rights", saying, "... you have trampled under foot every vital principle of our government. My natural rights, my civil rights, my political rights, my judicial rights, are all alike ignored." The judge sentenced Anthony to pay a fine of $100, she responded, "I shall never pay a dollar of your unjust penalty", and she never did.][ However the judge did not order her to be imprisoned until she paid the fine, for Anthony could have appealed her case.]Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of Pe ...

posthumously pardoned

A pardon is a government decision to allow a person to be relieved of some or all of the legal consequences resulting from a criminal conviction. A pardon may be granted before or after conviction for the crime, depending on the laws of the ju ...

Anthony on the centennial

{{other uses, Centennial (disambiguation), Centenary (disambiguation)

A centennial, or centenary in British English, is a 100th anniversary or otherwise relates to a century, a period of 100 years.

Notable events

Notable centennial events at a ...

of the ratification of the 19th Amendment.

''History of Woman Suffrage''

In 1876 Anthony, Stanton and Matilda Joslyn Gage began working on the History of Woman Suffrage

''History of Woman Suffrage'' is a book that was produced by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Matilda Joslyn Gage and Ida Husted Harper. Published in six volumes from 1881 to 1922, it is a history of the women's suffrage movement, primar ...

. Originally envisioned as a modest publication that would be produced quickly, the history evolved into a six-volume work of more than 5700 pages written over a period of 41 years. Its last two volumes were published in 1920, long after the deaths of the project's originators, by Ida Husted Harper, who also assisted with the fourth volume. Written by leaders of one wing of the divided women's movement (Lucy Stone, their main rival, refused to have anything to do with the project), the History of Woman Suffrage preserves an enormous amount of material that might have been lost forever, but it does not give a balanced view of events where their rivals are concerned. Because it was for years the main source of documentation about the suffrage movement, historians have had to uncover other sources to provide a more balanced view.

Introduction of the women's suffrage amendment

In 1878 Senator Aaron A. Sargent

Aaron Augustus Sargent (September 28, 1827 – August 14, 1887) was an American journalist, lawyer, politician and diplomat. In 1878, Sargent historically introduced what would later become the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Con ...

, a friend of Susan B. Anthony, introduced into Congress a women's suffrage amendment. More than forty years later it would become the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution with no changes to its wording. Its text is identical to that of the Fifteenth Amendment except that it prohibits the denial of suffrage because of sex rather than "race, color, or previous condition of servitude".

Although a machine politician on most issues, Sargent was a consistent supporter of women's rights who spoke at suffrage conventions and promoted suffrage through the legislative process.

Early female candidates for national office

Calling attention to the irony of being legally entitled to run for office while denied the right to vote, Elizabeth Cady Stanton declared herself a candidate for the U.S. Congress in 1866, the first woman to do so.

In 1872 Victoria Woodhull

Victoria Claflin Woodhull, later Victoria Woodhull Martin (September 23, 1838 – June 9, 1927), was an American leader of the women's suffrage movement who ran for President of the United States in the 1872 election. While many historians ...

formed her own party and declared herself to be its candidate for President of the U.S. even though she was ineligible because she was not yet 35 years old.

In 1884 Belva Ann Lockwood

Belva Ann Bennett Lockwood (October 24, 1830 – May 19, 1917) was an American lawyer, politician, educator, and author who was active in the women's rights and women's suffrage movements. She was one of the first women lawyers in the United Sta ...

, the first female lawyer to argue a case before the U.S. Supreme Court, became the first woman to conduct a viable campaign for president.

She was nominated, without her advance knowledge, by a California group called the Equal Rights Party. Lockwood advocated women's suffrage and other reforms during a coast-to-coast campaign that received respectful coverage from at least some major periodicals. She financed her campaign partly by charging admission to her speeches. Neither the AWSA nor the NWSA, both of whom had already endorsed the Republican candidate for president, supported Lockwood's candidacy.

Apart from runs for national office, many women were elected or appointed to hold certain offices across the country prior to the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment.

Initial successes

Women were enfranchised in frontier Wyoming Territory in 1869 and in Utah in 1870.

Because Utah held two elections before Wyoming, Utah became the first place in the nation where women legally cast ballots after the launch of the suffrage movement. The short-lived Populist Party endorsed women's suffrage, contributing to the enfranchisement of women in Colorado in 1893 and Idaho in 1896. In some localities, women gained various forms of partial suffrage, such as voting for school boards. According to a 2018 study in ''The Journal of Politics'', states with large suffrage movements and competitive political environments were more likely to extend voting rights to women; this is one reason why Western states were quicker to adopt women's suffrage than states in the East.

In the late 1870s, the suffrage movement received a major boost when the

Women were enfranchised in frontier Wyoming Territory in 1869 and in Utah in 1870.

Because Utah held two elections before Wyoming, Utah became the first place in the nation where women legally cast ballots after the launch of the suffrage movement. The short-lived Populist Party endorsed women's suffrage, contributing to the enfranchisement of women in Colorado in 1893 and Idaho in 1896. In some localities, women gained various forms of partial suffrage, such as voting for school boards. According to a 2018 study in ''The Journal of Politics'', states with large suffrage movements and competitive political environments were more likely to extend voting rights to women; this is one reason why Western states were quicker to adopt women's suffrage than states in the East.

In the late 1870s, the suffrage movement received a major boost when the Women's Christian Temperance Union

The Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) is an international temperance organization, originating among women in the United States Prohibition movement. It was among the first organizations of women devoted to social reform with a program th ...

(WCTU), the largest women's organization in the country, decided to campaign for suffrage and created a Franchise Department to support that effort. Frances Willard

Frances Elizabeth Caroline Willard (September 28, 1839 – February 17, 1898) was an American educator, temperance reformer, and women's suffragist. Willard became the national president of Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) in 1879 an ...

, its pro-suffrage leader, urged WCTU members to pursue the right to vote as a means of protecting their families from alcohol and other vices.

In 1886 the WCTU submitted to Congress petitions with 200,000 signatures in support of a national suffrage amendment.

In 1885 the Grange, a large farmers' organization, officially endorsed women's suffrage.

In 1890 the American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutu ...

, a large labor alliance, endorsed women's suffrage and subsequently collected 270,000 names on petitions supporting that goal.

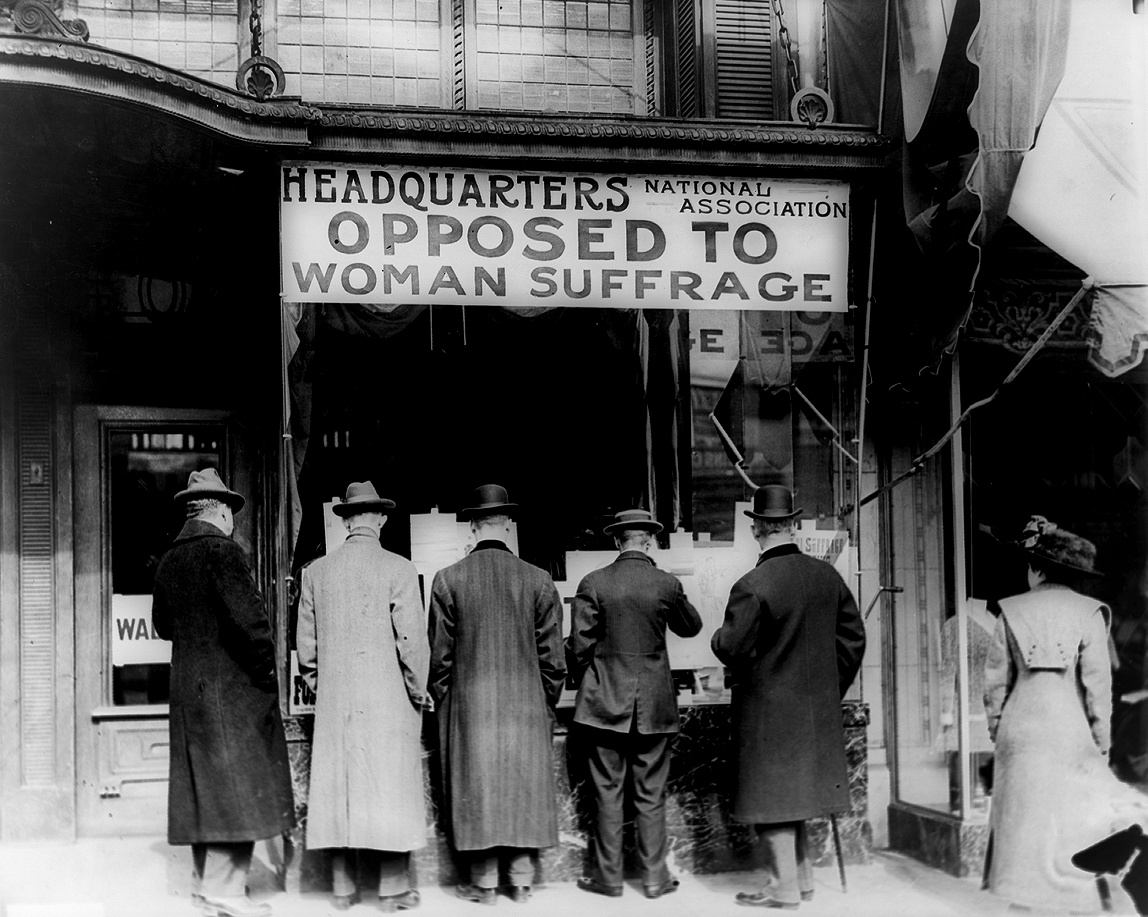

1890–1919

Merger of rival suffrage organizations

The AWSA, which was especially strong in New England, was initially the larger of the two rival suffrage organizations, but it declined in strength during the 1880s. Stanton and Anthony, the leading figures in the competing NWSA, were more widely known as leaders of the women's suffrage movement during this period and were more influential in setting its direction. They sometimes used daring tactics. Anthony, for example, interrupted the official ceremonies of the 100th anniversary of the U.S. Declaration of Independence to present the NWSA's Declaration of Rights for Women. The AWSA declined any involvement in the action.

Over time, the NWSA moved into closer alignment with the AWSA, placing less emphasis on confrontational actions and more on respectability, and no longer promoting a wide range of reforms. The NWSA's hopes for a federal suffrage amendment were frustrated when the Senate voted against it in 1887, after which the NWSA put more energy into campaigning at the state level, as the AWSA was already doing.

Over time, the NWSA moved into closer alignment with the AWSA, placing less emphasis on confrontational actions and more on respectability, and no longer promoting a wide range of reforms. The NWSA's hopes for a federal suffrage amendment were frustrated when the Senate voted against it in 1887, after which the NWSA put more energy into campaigning at the state level, as the AWSA was already doing.[Gordon, Ann D, "Woman Suffrage (Not Universal Suffrage) by Federal Amendment" in Wheeler, Marjorie Spruill (ed.), (1995), ''Votes for Women!: The Woman Suffrage Movement in Tennessee, the South, and the Nation'']

pp. 8, 14–16

Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. Work at the state level, however, also had its frustrations. Between 1870 and 1910, the suffrage movement conducted 480 campaigns in 33 states just to have the issue of women's suffrage brought before the voters, and those campaigns resulted in only 17 instances of the issue actually being placed on the ballot. These efforts led to women's suffrage in two states, Colorado and Idaho.

Alice Stone Blackwell

Alice Stone Blackwell (September 14, 1857 – March 15, 1950) was an American feminist, suffragist, journalist, radical socialist, and human rights advocate.

Early life and education

Blackwell was born in East Orange, New Jersey to Henry Browne ...

, daughter of AWSA leaders Lucy Stone and Henry Blackwell, was a major influence in bringing the rival suffrage leaders together, proposing a joint meeting in 1887 to discuss a merger. Anthony and Stone favored the idea, but opposition from several NWSA veterans delayed the move. In 1890 the two organizations merged as the National American Woman Suffrage Association

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was an organization formed on February 18, 1890, to advocate in favor of women's suffrage in the United States. It was created by the merger of two existing organizations, the National ...

(NAWSA). Stanton was president of the new organization, and Stone was chair of its executive committee, but Anthony, who had the title of vice president, was its leader in practice, becoming president herself in 1892 when Stanton retired.

National American Woman Suffrage Association

Although Anthony was the leading force in the newly merged organization, it did not always follow her lead. In 1893 the NAWSA voted over Anthony's objection to alternate the site of its annual conventions between Washington and various other parts of the country. Anthony's pre-merger NWSA had always held its conventions in Washington to help maintain focus on a national suffrage amendment. Arguing against this decision, she said she feared, accurately as it turned out, that the NAWSA would engage in suffrage work at the state level at the expense of national work.

Stanton, elderly but still very much a radical, did not fit comfortably into the new organization, which was becoming more conservative. In 1895 she published ''The Woman's Bible