February Revolution on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in

The revolution was provoked by Russian military failures during the First World War, as well as public dissatisfaction with the way the country was run on the home front. The economic challenges faced due to fighting a total war also contributed.

In August 1914, all classes supported and virtually all political deputies voted in favour of the war. The declaration of war was followed by a revival of

The revolution was provoked by Russian military failures during the First World War, as well as public dissatisfaction with the way the country was run on the home front. The economic challenges faced due to fighting a total war also contributed.

In August 1914, all classes supported and virtually all political deputies voted in favour of the war. The declaration of war was followed by a revival of

Nicholas's response on 27 February O.S (12 March N.S), perhaps based on the Empress's earlier letter to him that the concern about Petrograd was an over-reaction, was one of irritation that "again, this fat Rodzianko has written me lots of nonsense, to which I shall not even deign to reply". Meanwhile, events unfolded in Petrograd. The bulk of the garrison mutinied, starting with the

Nicholas's response on 27 February O.S (12 March N.S), perhaps based on the Empress's earlier letter to him that the concern about Petrograd was an over-reaction, was one of irritation that "again, this fat Rodzianko has written me lots of nonsense, to which I shall not even deign to reply". Meanwhile, events unfolded in Petrograd. The bulk of the garrison mutinied, starting with the

The February Revolution immediately caused widespread excitement in Petrograd. On 3 March O.S (16 March N.S), a

The February Revolution immediately caused widespread excitement in Petrograd. On 3 March O.S (16 March N.S), a

During the

During the

When discussing the historiography of the February Revolution there are three historical interpretations which are relevant: Communist, Liberal, and Revisionist. These three different approaches exist separately from one another because of their respective beliefs of what ultimately caused the collapse of a Tsarist government in February.

* Communist historians present a story in which the masses that brought about revolution in February were organized groups of 'modernizing' peasants who were bringing about an era of both industrialization and freedom. Communist historian Boris Sokolov has been outspoken about the belief that the revolution in February was a coming together of the people and was more positive than the October revolution. Communist historians consistently place little emphasis on the role of World War I (WWI) in leading to the February Revolution.

* In contrast, Liberal perspectives of the February Revolution almost always acknowledge WWI as a catalyst to revolution. On the whole, though, Liberal historians credit the Bolsheviks with the ability to capitalize on the worry and dread instilled in Russian citizens because of WWI. The overall message and goal of the February Revolution, according to the Liberal perspective, was ultimately democracy; the proper climate and attitude had been created by WWI and other political factors which turned public opinion against the Tsar.

* Revisionist historians present a timeline where the revolution in February was far less inevitable than the liberals and communists would make it seem. Revisionists track the mounting pressure on the Tsarist regime back further than the other two groups to unsatisfied peasants in the countryside upset over matters of land-ownership. This tension continued to build into 1917 when dissatisfaction became a full-blown institutional crisis incorporating the concerns of many groups. Revisionist historian Richard Pipes has been outspoken about his anti-communist approach to the Russian Revolution.

::''"Studying Russian history from the West European perspective, one also becomes conscious of the effect that the absence of feudalism had on Russia. Feudalism had created in the West networks of economic and political institutions that served the central state... once

When discussing the historiography of the February Revolution there are three historical interpretations which are relevant: Communist, Liberal, and Revisionist. These three different approaches exist separately from one another because of their respective beliefs of what ultimately caused the collapse of a Tsarist government in February.

* Communist historians present a story in which the masses that brought about revolution in February were organized groups of 'modernizing' peasants who were bringing about an era of both industrialization and freedom. Communist historian Boris Sokolov has been outspoken about the belief that the revolution in February was a coming together of the people and was more positive than the October revolution. Communist historians consistently place little emphasis on the role of World War I (WWI) in leading to the February Revolution.

* In contrast, Liberal perspectives of the February Revolution almost always acknowledge WWI as a catalyst to revolution. On the whole, though, Liberal historians credit the Bolsheviks with the ability to capitalize on the worry and dread instilled in Russian citizens because of WWI. The overall message and goal of the February Revolution, according to the Liberal perspective, was ultimately democracy; the proper climate and attitude had been created by WWI and other political factors which turned public opinion against the Tsar.

* Revisionist historians present a timeline where the revolution in February was far less inevitable than the liberals and communists would make it seem. Revisionists track the mounting pressure on the Tsarist regime back further than the other two groups to unsatisfied peasants in the countryside upset over matters of land-ownership. This tension continued to build into 1917 when dissatisfaction became a full-blown institutional crisis incorporating the concerns of many groups. Revisionist historian Richard Pipes has been outspoken about his anti-communist approach to the Russian Revolution.

::''"Studying Russian history from the West European perspective, one also becomes conscious of the effect that the absence of feudalism had on Russia. Feudalism had created in the West networks of economic and political institutions that served the central state... once

Revolutions (Russian Empire)

, in

* Melancon, Michael S.

Social Conflict and Control, Protest and Repression (Russian Empire)

, in

* Sanborn, Joshua A.

Russian Empire

, in

* Gaida, Fedor Aleksandrovich

Governments, Parliaments and Parties (Russian Empire)

, in

* Albert, Gleb

Labour Movements, Trade Unions and Strikes (Russian Empire)

, in

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20100107023609/http://www.thecorner.org/hist/russia/revo1917.htm Russian Revolutions 1905–1917

Leon Trotsky's account

Лютнева революція. Жіночий бунт, який знищив Російську імперію (February Revolution. Female mutiny that destroyed the Russian Empire)

Soviet historiography

Soviet historiography is the methodology of history studies by historians in the Soviet Union (USSR). In the USSR, the study of history was marked by restrictions imposed by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). Soviet historiography i ...

as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and sometimes as the March Revolution, was the first of two revolutions which took place in Russia in 1917.

The main events of the revolution took place in and near Petrograd (present-day Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

), the then-capital of Russia, where long-standing discontent with the monarchy erupted into mass protests against food rationing on 23 February Old Style

Old Style (O.S.) and New Style (N.S.) indicate dating systems before and after a calendar change, respectively. Usually, this is the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar as enacted in various European countries between 158 ...

(8 March New Style

Old Style (O.S.) and New Style (N.S.) indicate dating systems before and after a calendar change, respectively. Usually, this is the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar as enacted in various European countries between 158 ...

). Revolutionary activity lasted about eight days, involving mass demonstrations and violent armed clashes with police and gendarmes

Wrong info! -->

A gendarmerie () is a military force with law enforcement duties among the civilian population. The term ''gendarme'' () is derived from the medieval French expression ', which translates to "men-at-arms" (literally, " ...

, the last loyal forces of the Russian monarchy. On 27 February O.S. (12 March N.S.) the forces of the capital's garrison sided with the revolutionaries. Three days later Tsar Nicholas II

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Pola ...

abdicated

Abdication is the act of formally relinquishing monarchical authority. Abdications have played various roles in the succession procedures of monarchies. While some cultures have viewed abdication as an extreme abandonment of duty, in other societ ...

, ending Romanov

The House of Romanov (also transcribed Romanoff; rus, Романовы, Románovy, rɐˈmanəvɨ) was the reigning imperial house of Russia from 1613 to 1917. They achieved prominence after the Tsarina, Anastasia Romanova, was married to ...

dynastic rule and the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

. The Russian Provisional Government

The Russian Provisional Government ( rus, Временное правительство России, Vremennoye pravitel'stvo Rossii) was a provisional government of the Russian Republic, announced two days before and established immediately ...

under Prince Georgy Lvov replaced the Council of Ministers of Russia The Russian Council of Ministers is an executive governmental council that brings together the principal officers of the Executive Branch of the Russian government. This includes the chairman of the government and ministers of federal government dep ...

.

The Provisional Government proved deeply unpopular and was forced to share dual power with the Petrograd Soviet

The Petrograd Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies (russian: Петроградский совет рабочих и солдатских депутатов, ''Petrogradskiy soviet rabochikh i soldatskikh deputatov'') was a city council of P ...

. After the July Days

The July Days (russian: Июльские дни) were a period of unrest in Petrograd, Russia, between . It was characterised by spontaneous armed demonstrations by soldiers, sailors, and industrial workers engaged against the Russian Provisi ...

, in which the Government killed hundreds of protesters, Alexander Kerensky

Alexander Fyodorovich Kerensky, ; original spelling: ( – 11 June 1970) was a Russian lawyer and revolutionary who led the Russian Provisional Government and the short-lived Russian Republic for three months from late July to early Nove ...

became head of Government. He was unable to fix Russia's immediate problems, including food shortages and mass unemployment, as he attempted to keep Russia involved in the ever more unpopular war

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

. The failures of the Provisional Government led to the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mome ...

by the Communist Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

later that year. The February Revolution had weakened the country; the October Revolution broke it, resulting in the Russian Civil War

, date = October Revolution, 7 November 1917 – Yakut revolt, 16 June 1923{{Efn, The main phase ended on 25 October 1922. Revolt against the Bolsheviks continued Basmachi movement, in Central Asia and Tungus Republic, the Far East th ...

and the eventual formation of the Soviet Union.

The revolution appeared to have broken out without any real leadership or formal planning. Russia had been suffering from a number of economic and social problems, which compounded after the start of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in 1914. Disaffected soldiers from the city's garrison joined bread rioters, primarily women

A woman is an adult female human. Prior to adulthood, a female human is referred to as a girl (a female child or Adolescence, adolescent). The plural ''women'' is sometimes used in certain phrases such as "women's rights" to denote female hum ...

in bread lines, and industrial strikers on the streets. As more and more troops of the undisciplined garrison of the capital deserted, and with loyal troops away at the F

front, the city fell into chaos, leading to the Tsar's decision to abdicate under his generals' advice. In all, over 1,300 people were killed during the protests of February 1917.Curtis 1957, p. 30. The historiographical reasons for the revolution have varied. Russian historians writing during the time of the Soviet Union cited as cause anger of the proletariat against the bourgeois boiling over. Russian Liberals cited World War I. Revisionists tracked it back to land disputes after the serf era. Modern historians cite a combination of these factors and criticize mythologization of the event.

Etymology

Despite occurring in March of theGregorian calendar

The Gregorian calendar is the calendar used in most parts of the world. It was introduced in October 1582 by Pope Gregory XIII as a modification of, and replacement for, the Julian calendar. The principal change was to space leap years dif ...

, the event is most commonly known as the "February Revolution" because at the time Russia still used the Julian calendar

The Julian calendar, proposed by Roman consul Julius Caesar in 46 BC, was a reform of the Roman calendar. It took effect on , by edict. It was designed with the aid of Greek mathematicians and astronomers such as Sosigenes of Alexandr ...

. The event is sometimes known as the "March Revolution", after the Soviet Union modernized its calendar. To avoid confusion, both O.S and N.S. dates have been given for events. (For more details see Old Style and New Style dates

Old Style (O.S.) and New Style (N.S.) indicate dating systems before and after a calendar change, respectively. Usually, this is the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar as enacted in various European countries between 158 ...

) .

Causes

A number of factors contributed to the February Revolution, both short and long-term. Historians disagree on the main factors that contributed to this. Liberal historians emphasise the turmoil created by the war, whereas Marxists emphasise the inevitability of change.Alexander Rabinowitch

Alexander Rabinowitch (born 30 August 1934) is an American historian. He is Professor Emeritus of History at the Indiana University, Bloomington, where he taught from 1968 until 1999, and Affiliated Research Scholar at the St. Petersburg Institute ...

summarises the main long-term and short-term causes:

:"The February 1917 revolution ... grew out of pre-war political and economic instability, technological backwardness, and fundamental social divisions, coupled with gross mismanagement of the war effort, continuing military defeats, domestic economic dislocation, and outrageous scandals surrounding the monarchy."

Long-term causes

Despite its occurrence at the height of World War I, the roots of the February Revolution dated further back. Chief among these was Imperial Russia's failure, throughout the 19th and early 20th century, to modernise its archaic social, economic, and political structures while maintaining the stability of ubiquitous devotion to an autocratic monarch. As historian Richard Pipes writes, "the incompatibility of capitalism and autocracy struck all who gave thought to the matter". The first major event of theRussian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and ad ...

was the February Revolution, a chaotic affair caused by the culmination of over a century of civil and military unrest between the common people and the Tsar and aristocratic landowners. The causes can be summarized as the ongoing cruel treatment of peasants by the bourgeoisie, poor working conditions of industrial workers, and the spreading of western democratic ideas by political activists, leading to a growing political and social awareness in the lower classes. Dissatisfaction of proletarians was compounded by food shortages and military failures. In 1905, Russia experienced humiliating losses in its war with Japan, then during Bloody Sunday

Bloody Sunday may refer to:

Historical events Canada

* Bloody Sunday (1923), a day of police violence during a steelworkers' strike for union recognition in Sydney, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia

* Bloody Sunday (1938), police violence aga ...

and the Revolution of 1905, Tsarist troops fired upon a peaceful, unarmed crowd. These events further divided Nicholas II

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Pola ...

from his people. Widespread strikes, riots, and the famous mutiny on the Battleship ''Potemkin'' ensued.

These conditions caused much agitation among the small working and professional classes. This tension erupted into general revolt with the 1905 Revolution, and again under the strain of war in 1917, this time with lasting consequences.

Short-term causes

The revolution was provoked by Russian military failures during the First World War, as well as public dissatisfaction with the way the country was run on the home front. The economic challenges faced due to fighting a total war also contributed.

In August 1914, all classes supported and virtually all political deputies voted in favour of the war. The declaration of war was followed by a revival of

The revolution was provoked by Russian military failures during the First World War, as well as public dissatisfaction with the way the country was run on the home front. The economic challenges faced due to fighting a total war also contributed.

In August 1914, all classes supported and virtually all political deputies voted in favour of the war. The declaration of war was followed by a revival of nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

across Russian society, which temporarily reduced internal strife. The army achieved some early victories (such as in Galicia in 1915 and with the Brusilov Offensive in 1916) but also suffered major defeats, notably Tannenberg in August 1914, the Winter Battle in Masuria in February 1915 and the loss of Russian Poland during May to August 1915. Nearly six million casualties —dead, wounded, and missing— had been accrued by January 1917. Mutinies

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military, of a crew or of a crew of pirates) to oppose, change, or overthrow an organization to which they were previously loyal. The term is commonly used for a rebellion among members ...

sprang up more often (most due to simple war-weariness

War-weariness is the public or political disapproval for the continuation of a prolonged conflict or war. The causes normally involve the intensity of casualties—financial, civilian, and military. It also occurs when a belligerent has the abil ...

), morale

Morale, also known as esprit de corps (), is the capacity of a group's members to maintain belief in an institution or goal, particularly in the face of opposition or hardship. Morale is often referenced by authority figures as a generic value ...

was at its lowest, and the newly called-up officers and commanders were at times very incompetent. Like all major armies, Russia's armed forces had inadequate supply. The pre-revolution desertion rate ran at around 34,000 a month. Meanwhile, the wartime alliance of industry, the Duma

A duma (russian: дума) is a Russian assembly with advisory or legislative functions.

The term ''boyar duma'' is used to refer to advisory councils in Russia from the 10th to 17th centuries. Starting in the 18th century, city dumas were for ...

(lower house of parliament) and the Stavka

The ''Stavka'' (Russian and Ukrainian: Ставка) is a name of the high command of the armed forces formerly in the Russian Empire, Soviet Union and currently in Ukraine.

In Imperial Russia ''Stavka'' referred to the administrative staff, a ...

(Military High Command) started to work outside the Tsar's control.

In an attempt to boost morale and repair his reputation as a leader, Tsar Nicholas announced in the summer of 1915 that he would take personal command of the army, in defiance of almost universal advice to the contrary. The result was disastrous on three grounds. Firstly, it associated the monarchy with the unpopular war; secondly, Nicholas proved to be a poor leader of men on the front, often irritating his own commanders with his interference; and thirdly, being at the front made him unavailable to govern. This left the reins of power to his wife, the German Tsarina Alexandra, who was unpopular and accused of being a German spy, and under the thumb of her confidant – Grigori Rasputin, himself so unpopular that he was assassinated by members of the nobility in December 1916. The Tsarina proved an ineffective ruler in a time of war, announcing a rapid succession of different Prime Ministers and angering the Duma. The lack of strong leadership is illustrated by a telegram from Octobrist

The Union of 17 October (russian: Союз 17 Октября, ''Soyuz 17 Oktyabrya''), commonly known as the Octobrist Party (Russian: Октябристы, ''Oktyabristy''), was a liberal-reformist constitutional monarchist political party in la ...

politician Mikhail Rodzianko

Mikhail Vladimirovich Rodzianko (russian: Михаи́л Влади́мирович Родзя́нко; uk, Михайло Володимирович Родзянко; 21 February 1859, Yekaterinoslav Governorate – 24 January 1924, Beod ...

to the Tsar on 26 February O.S. (11 March N.S) 1917, in which Rodzianko begged for a minister with the "confidence of the country" be instated immediately. Delay, he wrote, would be "tantamount to death".

On the home front, a famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food, caused by several factors including war, natural disasters, crop failure, population imbalance, widespread poverty, an economic catastrophe or government policies. This phenomenon is usually accompani ...

loomed and commodities became scarce due to the overstretched railroad network. Meanwhile, refugees from German-occupied Russia came in their millions. The Russian economy

The economy of Russia has gradually transformed from a planned economy into a mixed market-oriented economy.

—Rosefielde, Steven, and Natalia Vennikova. “Fiscal Federalism in Russia: A Critique of the OECD Proposals.” Cambridge Journa ...

, which had just seen one of the highest growth rates in Europe, was blocked from the continent's markets by the war. Though industry did not collapse, it was considerably strained and when inflation soared, wages could not keep up. The Duma, which was composed of liberal deputies, warned Tsar Nicholas II of the impending danger and counselled him to form a new constitutional government, like the one he had dissolved after some short-term attempts in the aftermath of the 1905 Revolution. The Tsar ignored the advice. Historian Edward Acton argues that "by stubbornly refusing to reach any '' modus vivendi'' with the Progressive Bloc

The Progressive Bloc () is an electoral alliance in the Dominican Republic. The alliance is led by the Dominican Liberation Party

The Dominican Liberation Party ( Spanish: Partido de la Liberación Dominicana, referred to here by its Spanis ...

of the Duma... Nicholas undermined the loyalty of even those closest to the throne ndopened an unbridgeable breach between himself and the public opinion." In short, the Tsar no longer had the support of the military, the nobility or the Duma (collectively the ''élites''), or the Russian people. The inevitable result was revolution.

Events

Towards the February Revolution

When Rasputin was assassinated on 30 December 1916, and the assassins went unchallenged, this was interpreted as an indication of the truth of the accusation his wife relied on the Siberianstarets

A starets (russian: стáрец, p=ˈstarʲɪt͡s; fem. ) is an elder of an Eastern Orthodox monastery who functions as venerated adviser and teacher. ''Elders'' or ''spiritual fathers'' are charismatic spiritual leaders whose wisdom stems from Go ...

. The authority of the tsar, who now stood as a moral weakling, sank further. On the Emperor dismissed his Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister i ...

, Alexander Trepov

Alexander Fyodorovich Trepov (; 30 September 1862, Kiev – 10 November 1928, Nice) was the Prime Minister of the Russian Empire from 23 November 1916 until 9 January 1917. He was conservative, a monarchist, a member of the Russian Assembly, a ...

. On a hesitatant Nikolai Golitsyn

Prince Nikolai Dmitriyevich Golitsyn (russian: Никола́й Дми́триевич Голи́цын; 12 April 1850 – 2 July 1925) was a Russian aristocrat, monarchist and the last prime minister of Imperial Russia. He was in office from 2 ...

became the successor of Trepov. Golitsyn begged the Emperor to cancel his appointment, citing his lack of preparation for the role of Prime Minister. On Mikhail Belyaev succeeded Dmitry Shuvayev

Dmitry Savelyevich Shuvayev (; – 19 December 1937) was a Russian military leader, Infantry General (1912) and Minister of War (1916).

Life

Dmitry Shuvayev graduated from Alexander Military School in 1872. Between 1873 and 1875, he particip ...

(who did not speak any foreign language) as Minister of War, likely at the request of the Empress.

The Duma President Mikhail Rodzianko

Mikhail Vladimirovich Rodzianko (russian: Михаи́л Влади́мирович Родзя́нко; uk, Михайло Володимирович Родзянко; 21 February 1859, Yekaterinoslav Governorate – 24 January 1924, Beod ...

, Grand Duchess Marie Pavlovna and British ambassador Buchanan joined calls for Alexandra to be removed from influence, but Nicholas still refused to take their advice. Many people came to the conclusion that the problem was not Rasputin. According to Rodzianko the Empress "exerts an adverse influence on all appointments, including even those in the army." On 11 January O.S. (24 January N.S.) the Duma opening was postponed to the 25th (7 February N.S.).

On 14 January O.S. (27 January N.S.) Georgy Lvov proposed to Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich that he (the Grand Duke) should take control of the country. At the end of January/beginning of February major negotiations took place between the Allied powers in Petrograd; unofficially they sought to clarify the internal situation in Russia.

On 8 February, at the wish of the Tsar, Nikolay Maklakov

Nikolay Alexeyevich Maklakov (9 September 1871 – 5 September 1918) (N.S.) was a Chamberlain of the Imperial court, a Russian monarchist, and a prominent right-wing statesman. He was a governor in the Ukrain and state councillor who served as ...

, together with Alexander Protopopov

Alexander Dmitrievich Protopopov (; 18 December 1866 – 27 October 1918) was a Russian publicist and politician who served as Minister of the Interior from September 1916 to February 1917.

Protopopov became a leading liberal politician in Rus ...

..., drafted the text of the manifesto on the dissolution of the Duma (before it was opened on 14 February 1917). The Duma was dissolved and Protopopov was proclaimed dictator

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a small clique. The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to rule the republic in tim ...

. On 14 February O.S. (27 February N.S.) police agents reported that army officers had, for the first time, mingled with the crowds demonstrating against the war and the government on Nevsky Prospekt. Alexander Kerensky

Alexander Fyodorovich Kerensky, ; original spelling: ( – 11 June 1970) was a Russian lawyer and revolutionary who led the Russian Provisional Government and the short-lived Russian Republic for three months from late July to early Nove ...

took the opportunity to attack the Tsarist regime.

Protests

By 1917, the majority of Petersburgers had lost faith in theTsarist regime

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. The ...

. Government corruption was unrestrained, and Tsar Nicholas II

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Pola ...

had frequently disregarded the Imperial Duma

The State Duma, also known as the Imperial Duma, was the lower house of the Governing Senate in the Russian Empire, while the upper house was the State Council. It held its meetings in the Taurida Palace in St. Petersburg. It convened four times ...

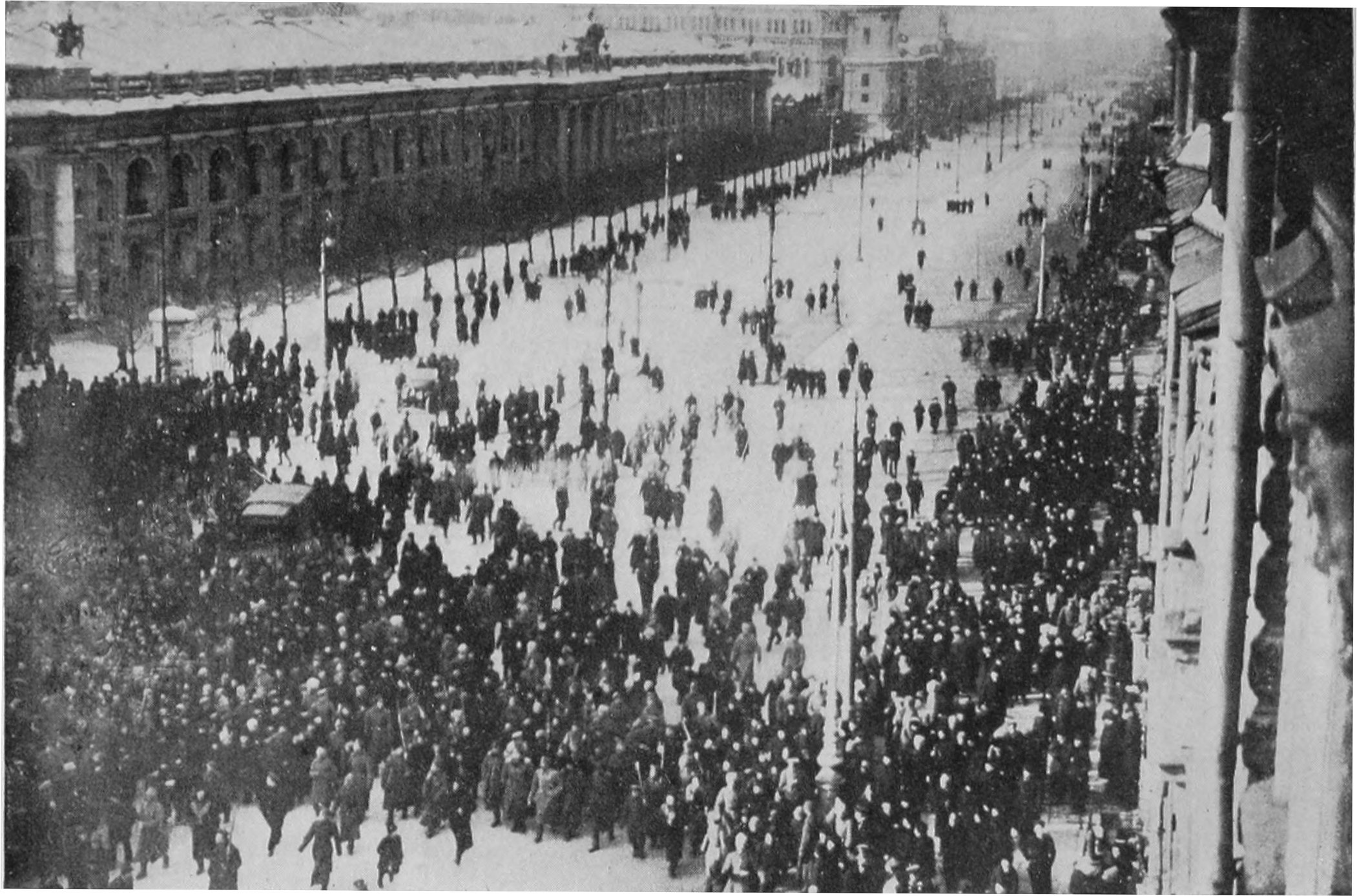

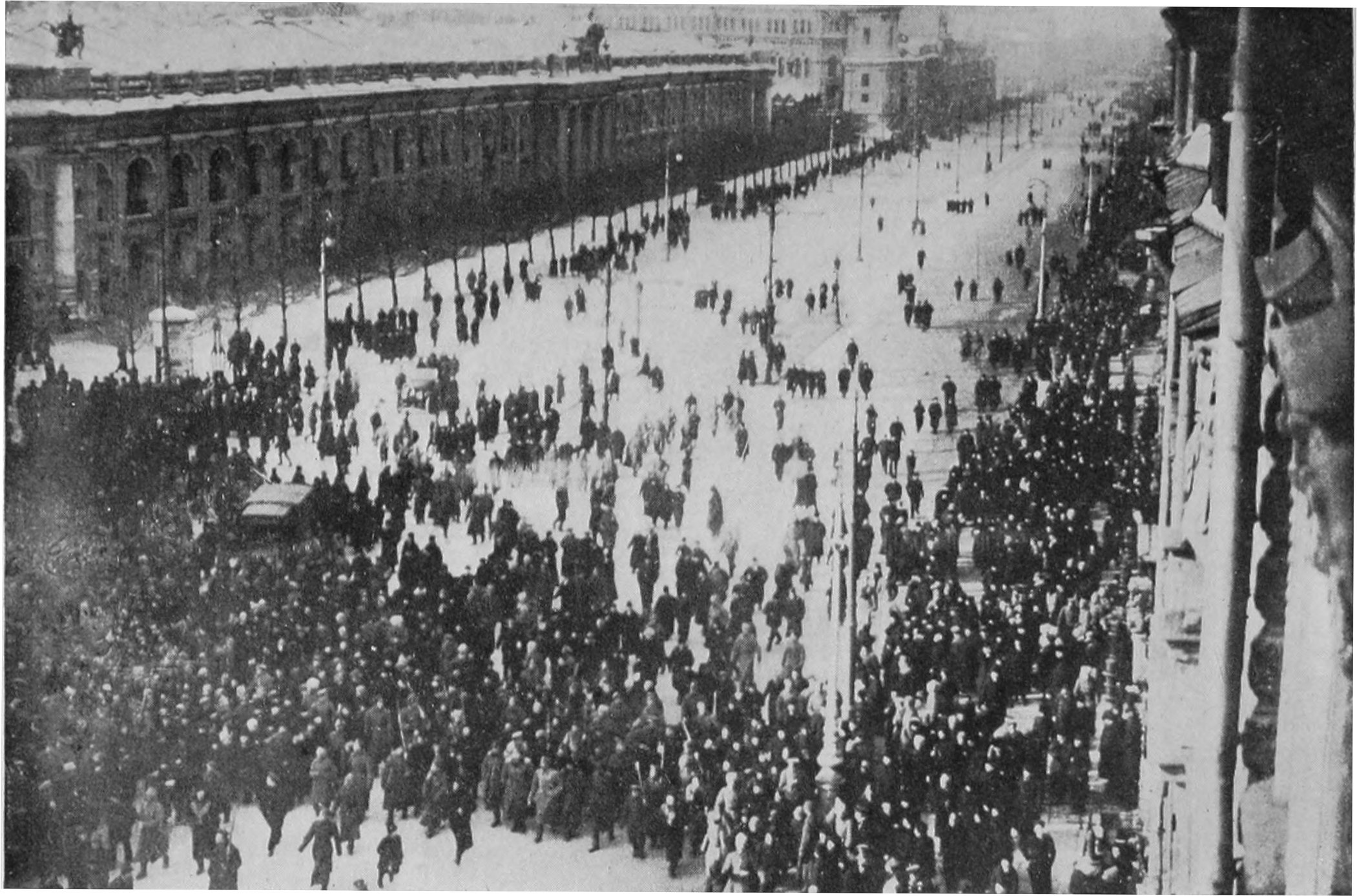

. Thousands of workers flooded the streets of Petrograd (modern St. Petersburg) to show their dissatisfaction.Curtis 1957, p. 1. The first major protest of the February Revolution occurred on 18 February O.S. (3 March N.S) as workers of Putilov Factory, Petrograd's largest industrial plant, announced a strike

Strike may refer to:

People

* Strike (surname)

Physical confrontation or removal

*Strike (attack), attack with an inanimate object or a part of the human body intended to cause harm

*Airstrike, military strike by air forces on either a suspected ...

to demonstrate against the government. Strikes continued on the following days. Due to heavy snowstorms, tens of thousands of freight cars were stuck on the tracks, with the bread and fuel. On 22 February O.S. (7 March N.S.) the Tsar left for the front.

On 23 February O.S. (8 March N.S.), Putilov protesters were joined in the uprising by those celebrating International Woman's Day and protesting against the government's implemented food rationing.Williams 1987, p. 9. As the Russian government began rationing flour and bread, rumors of food shortages circulated and bread riots erupted across the city of Petrograd. Women, in particular, were passionate in showing their dissatisfaction with the implemented rationing system, and the female workers marched to nearby factories to recruit over 50,000 workers for the strikes. Both men and women flooded the streets of Petrograd, demanding an end to Russian food shortages, the end of World War I, and the end of autocracy

Autocracy is a system of government in which absolute power over a state is concentrated in the hands of one person, whose decisions are subject neither to external legal restraints nor to regularized mechanisms of popular control (except perh ...

. By the following day 24 February O.S. (9 March N.S), nearly 200,000 protesters filled the streets, demanding the replacement of the Tsar with a more progressive political leader. They called for the war to end and for the Russian monarchy to be overthrown. By 25 February O.S (10 March N.S), nearly all industrial enterprises in Petrograd were shut down by the uprising. Although all gatherings on the streets were absolutely forbidden some 250,000 people were on strike. The president of the Imperial Duma Rodzianko asked the chairman of the Council of Ministers Golitsyn to resign; the minister of Foreign Affairs Nikolai Pokrovsky proposed the resignation of the whole government. There were disturbances on the Nevsky Prospect during the day and in the late afternoon four people were killed.

The Tsar took action to address the riots on 25 February O.S (10 March N.S) by wiring garrison commander General Sergey Semyonovich Khabalov, an inexperienced and extremely indecisive commander of the Petrograd military district

The Petersburg Military District (Питербургский вое́нный о́круг) was a Military District of the Russian Empire originally created in August 1864 following Order B-228 of Dmitry Milyutin, the Minister of War of the Russia ...

, to disperse the crowds with rifle fire and to suppress the "impermissible" rioting by force. On 26 February O.S (11 March N.S) the centre of the city was cordoned off. Nikolai Pokrovsky reported about his negotiations with the Bloc (led by Maklakov) at the session of the Council of Ministers in the Mariinsky Palace

Mariinsky Palace (), also known as Marie Palace, was the last neoclassical Imperial residence to be constructed in Saint Petersburg. It was built between 1839 and 1844, designed by the court architect Andrei Stackenschneider. It houses the ci ...

. The Bloc spoke for the resignation of the government.

During the late afternoon of 26 February O.S (11 March N.S) the Fourth Company of the Pavlovsky Reserve Regiment broke out of their barracks upon learning that another detachment of the regiment had clashed with demonstrators near the Kazan Cathedral. After firing at mounted police the soldiers of the Fourth Company were disarmed by the Preobrazhensky Regiment

The Preobrazhensky Life-Guards Regiment (russian: Преображенский лейб-гвардии полк, ''Preobrazhensky leyb-gvardii polk'') was a regiment of the Imperial Guard of the Imperial Russian Army from 1683 to 1917.

The P ...

. This marked the first instance of open mutiny in the Petrograd garrison. On 26 February O.S (11 March N.S) Mikhail Rodzianko

Mikhail Vladimirovich Rodzianko (russian: Михаи́л Влади́мирович Родзя́нко; uk, Михайло Володимирович Родзянко; 21 February 1859, Yekaterinoslav Governorate – 24 January 1924, Beod ...

, Chairman of the Duma

A duma (russian: дума) is a Russian assembly with advisory or legislative functions.

The term ''boyar duma'' is used to refer to advisory councils in Russia from the 10th to 17th centuries. Starting in the 18th century, city dumas were for ...

, had sent the Tsar a report of the chaos in a telegram (exact wordings and translations differ, but each retains a similar sense):

Golitsyn received by telegraph a decree

A decree is a legal proclamation, usually issued by a head of state (such as the president of a republic or a monarch), according to certain procedures (usually established in a constitution). It has the force of law. The particular term used ...

from the Tsar dissolving the Duma once again. Golitsyn used a (signed, but not yet dated) ukaze

In Imperial Russia, a ukase () or ukaz (russian: указ ) was a proclamation of the tsar, government, or a religious leader (patriarch) that had the force of law. "Edict" and "decree" are adequate translations using the terminology and concepts ...

declaring that his Majesty had decided to interrupt the Duma until April, leaving it with no legal authority to act. The Council of Elders and the deputies refused to comply in the face of unrest.

On the next day (27 February O.S, 12 March N.S), the Duma remained obedient, and "did not attempt to hold an official sitting". Then some delegates decided to form a Provisional Committee of the State Duma

The Provisional Committee of the State Duma () was a special government body established on March 12, 1917 (27 February O.S.) by the Fourth State Duma deputies at the outbreak of the February Revolution in the same year. It was formed under th ...

, led by Rodzianko and backed by major Moscow manufacturers and St. Petersburg bankers. Vasily Maklakov was appointed as one of the 24 commissars of the Provisional Committee of the State Duma. Its first meeting was on the same evening and ordered the arrest of all the ex-ministers and senior officials. The Duma refused to head the revolutionary movement. At the same time, socialists also formed the Petrograd Soviet

The Petrograd Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies (russian: Петроградский совет рабочих и солдатских депутатов, ''Petrogradskiy soviet rabochikh i soldatskikh deputatov'') was a city council of P ...

. In the Mariinsky Palace

Mariinsky Palace (), also known as Marie Palace, was the last neoclassical Imperial residence to be constructed in Saint Petersburg. It was built between 1839 and 1844, designed by the court architect Andrei Stackenschneider. It houses the ci ...

the Council of Ministers of Russia The Russian Council of Ministers is an executive governmental council that brings together the principal officers of the Executive Branch of the Russian government. This includes the chairman of the government and ministers of federal government dep ...

, assisted by Rodzyanko

Alexander Pavlovich Rodzyanko (russian: Александр Павлович Родзянко; 26 August 1879 – 6 May 1970) was an officer of the Imperial Russian Army during the World War I and lieutenant-general and a corps commander of the W ...

, held its last meeting. Protopopov was told to resign and offered to commit suicide. The Council formally submitted its resignation to the Tsar.

By nightfall, General Khabalov and his forces faced a capital controlled by revolutionaries.Wildman 1970, p. 8. The protesters of Petrograd burned and sacked the premises of the district court, the headquarters of the secret police, and many police stations. They also occupied the Ministry of Transport, seized the arsenal, and released prisoners into the city. Army officers retreated into hiding and many took refuge in the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

, but moved that night to the Winter Palace

The Winter Palace ( rus, Зимний дворец, Zimnij dvorets, p=ˈzʲimnʲɪj dvɐˈrʲɛts) is a palace in Saint Petersburg that served as the official residence of the Emperor of all the Russias, Russian Emperor from 1732 to 1917. The p ...

.

Tsar's return and abdication

Nicholas's response on 27 February O.S (12 March N.S), perhaps based on the Empress's earlier letter to him that the concern about Petrograd was an over-reaction, was one of irritation that "again, this fat Rodzianko has written me lots of nonsense, to which I shall not even deign to reply". Meanwhile, events unfolded in Petrograd. The bulk of the garrison mutinied, starting with the

Nicholas's response on 27 February O.S (12 March N.S), perhaps based on the Empress's earlier letter to him that the concern about Petrograd was an over-reaction, was one of irritation that "again, this fat Rodzianko has written me lots of nonsense, to which I shall not even deign to reply". Meanwhile, events unfolded in Petrograd. The bulk of the garrison mutinied, starting with the Volinsky Regiment

The Volinsky Lifeguard Regiment (russian: Волынский лейб-гвардии полк), more correctly translated as the Volhynian Life-Guards Regiment, was a Russian Imperial Guard infantry regiment. Created out of a single battalion o ...

. Soldiers of this regiment brought the

, Preobrazhensky, and Moskovsky Regiments out on the street to join the rebellion, resulting in the hunting down of police and the gathering of 40,000 rifles which were dispersed among the workers. Even the Cossack units that the government had come to use for crowd control showed signs that they supported the people. Although few actively joined the rioting, many officers were either shot or went into hiding; the ability of the garrison to hold back the protests was all but nullified. Symbols of the Tsarist regime were rapidly torn down around the city and governmental authority in the capital collapsed – not helped by the fact that Nicholas had earlier that day suspended a session in the Duma

A duma (russian: дума) is a Russian assembly with advisory or legislative functions.

The term ''boyar duma'' is used to refer to advisory councils in Russia from the 10th to 17th centuries. Starting in the 18th century, city dumas were for ...

that was intended to discuss the issue further, leaving it with no legal authority to act. Attempts were made by high-ranking military leaders to persuade the Tsar to resign power to the Duma.

The response of the Duma, urged on by the Progressive Bloc

The Progressive Bloc () is an electoral alliance in the Dominican Republic. The alliance is led by the Dominican Liberation Party

The Dominican Liberation Party ( Spanish: Partido de la Liberación Dominicana, referred to here by its Spanis ...

, was to establish a Provisional Committee to restore law and order; the Provisional Committee declared itself the governing body of the Russian Empire. Chief among them was the desire to bring the war to a successful conclusion in conjunction with the Allies, and the very cause of their opposition was the ever-deepening conviction that this was unattainable under the present government and under the present regime. Meanwhile, the socialist parties re-established the Petrograd Soviet

The Petrograd Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies (russian: Петроградский совет рабочих и солдатских депутатов, ''Petrogradskiy soviet rabochikh i soldatskikh deputatov'') was a city council of P ...

, first created during the 1905 revolution, to represent workers and soldiers. The remaining loyal units switched allegiance the next day.

On 28 February O.S (13 March N.S), at five in the morning, the Tsar left Mogilev

Mogilev (russian: Могилёв, Mogilyov, ; yi, מאָלעוו, Molev, ) or Mahilyow ( be, Магілёў, Mahilioŭ, ) is a city in eastern Belarus, on the Dnieper River, about from the border with Russia's Smolensk Oblast and from the bor ...

, (and also directed Nikolai Ivanov to go to Tsarskoye Selo) but was unable to reach Petrograd as revolutionaries controlled railway stations around the capital. Around midnight the train was stopped at Malaya Vishera

Malaya Vishera (russian: Ма́лая Ви́шера) is a town and the administrative center of Malovishersky District in Novgorod Oblast, Russia. Population:

History

The name of the town originates from the Malaya Vishera River, a tributary ...

, turned, and in the evening of 1 March O.S (14 March N.S) Nicholas arrived in Pskov. In the meantime, the units guarding the Alexander Palace in Tsarskoe Selo either "declared their neutrality" or left for Petrograd and thus abandoned the Imperial Family. On 28 February Nikolay Maklakov

Nikolay Alexeyevich Maklakov (9 September 1871 – 5 September 1918) (N.S.) was a Chamberlain of the Imperial court, a Russian monarchist, and a prominent right-wing statesman. He was a governor in the Ukrain and state councillor who served as ...

was arrested having tried to prevent a revolution together with Alexander Protopopov

Alexander Dmitrievich Protopopov (; 18 December 1866 – 27 October 1918) was a Russian publicist and politician who served as Minister of the Interior from September 1916 to February 1917.

Protopopov became a leading liberal politician in Rus ...

(on 8 February).

The Army Chief Nikolai Ruzsky

Nikolai Vladimirovich Ruzsky (russian: Никола́й Влади́мирович Ру́зский; – October 18, 1918) was a Russian general, member of the state and military councils, best known for his role in World War I and the abdi ...

, and the Duma deputies Vasily Shulgin

Vasily Vitalyevich Shulgin (russian: Васи́лий Вита́льевич Шульги́н; 13 January 1878 – 15 February 1976) was a Russian conservative monarchist, politician and member of the White movement.

Young years

Shulgin was bo ...

and Alexander Guchkov

Alexander Ivanovich Guchkov (russian: Алекса́ндр Ива́нович Гучко́в) (14 October 1862 – 14 February 1936) was a Russian politician, Chairman of the Third Duma and Minister of War in the Russian Provisional Government. ...

who had come to advise the Tsar, suggested that he abdicate the throne. He did so on behalf of himself and his son, Tsarevich Alexei

Grand Duke Alexei Petrovich of Russia (28 February 1690 – 26 June 1718) was a Russian Tsarevich. He was born in Moscow, the son of Tsar Peter I and his first wife, Eudoxia Lopukhina. Alexei despised his father and repeatedly thwarted Peter's p ...

. At 3 o'clock in the afternoon of Thursday, 2 March O.S (15 March N.S), Nicholas nominated his brother, the Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich, to succeed him. The next day the Grand Duke realised that he would have little support as ruler, so he declined the crown, stating that he would take it only if that was the consensus of democratic action by the Russian Constituent Assembly

The All Russian Constituent Assembly (Всероссийское Учредительное собрание, Vserossiyskoye Uchreditelnoye sobraniye) was a constituent assembly convened in Russia after the October Revolution of 1917. It met fo ...

, which shall define the form of government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

for Russia. The 300-year-old Romanov dynasty ended with the Grand Duke's decision on 3 March O.S (16 March N.S). On 8 March O.S (22 March N.S) the former Tsar, addressed with contempt by the sentries as "Nicholas Romanov", was reunited with his family at the Alexander Palace at Tsarskoye Selo

Tsarskoye Selo ( rus, Ца́рское Село́, p=ˈtsarskəɪ sʲɪˈlo, a=Ru_Tsarskoye_Selo.ogg, "Tsar's Village") was the town containing a former residence of the Russian imperial family and visiting nobility, located south from the c ...

. He and his family and loyal retainers were placed under protective custody by the Provisional Government in the palace.

Establishment of Dual Power

The February Revolution immediately caused widespread excitement in Petrograd. On 3 March O.S (16 March N.S), a

The February Revolution immediately caused widespread excitement in Petrograd. On 3 March O.S (16 March N.S), a provisional government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, or a transitional government, is an emergency governmental authority set up to manage a political transition generally in the cases of a newly formed state or ...

was announced by the Provisional Committee of the State Duma

The Provisional Committee of the State Duma () was a special government body established on March 12, 1917 (27 February O.S.) by the Fourth State Duma deputies at the outbreak of the February Revolution in the same year. It was formed under th ...

. The Provisional Government published its manifesto declaring itself the governing body of the Russian Empire that same day. The manifesto proposed a plan of civic and political rights and the installation of a democratically elected Russian Constituent Assembly

The All Russian Constituent Assembly (Всероссийское Учредительное собрание, Vserossiyskoye Uchreditelnoye sobraniye) was a constituent assembly convened in Russia after the October Revolution of 1917. It met fo ...

, but did not touch on many of the topics that were driving forces in the revolution such as participation in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and land. At the same time, the Petrograd Soviet

The Petrograd Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies (russian: Петроградский совет рабочих и солдатских депутатов, ''Petrogradskiy soviet rabochikh i soldatskikh deputatov'') was a city council of P ...

(or workers' council) began organizing and was officially formed on 27 February. The Petrograd Soviet and the Provisional Government shared dual power over Russia. The term dual power came about as the driving forces in the fall of the monarchy, opposition to the human and widespread political movement, became politically institutionalized.

While the Soviet represented the proletariat, the provisional government represented the bourgeoisie. The Soviet had stronger practical power because it controlled the workers and the soldiers, but it did not want to become involved in administration and bureaucracy; the Provisional Government lacked support from the population. Since the Provisional Government did not have the support of the majority and, in an effort to keep their claim to democratic mandate, they welcomed socialist parties to join in order to gain more support and Dvoyevlastiye (dual power) was established. However, the Soviet asserted ''de facto'' supremacy as early as 1 March O.S (14 March N.S) (before the creation of the Provisional Government), by issuing Order No. 1

The Order No. 1 was issued March 1, 1917 (March 14 New Style) and was the first official decree of the Petrograd Soviet, Petrograd Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies. The order was issued following the February Revolution in response to acti ...

:

Order No. 1 ensured that the Dual Authority developed on the Soviet's conditions. The Provisional Government was not a publicly elected body (having been self-proclaimed by committee members of the old Duma) and it lacked the political legitimacy to question this arrangement and instead arranged for elections to be held later. The Provisional Government had the formal authority in Russia but the Soviet Executive Committee and the soviets had the support of the majority of the population. The Soviet held the real power to effect change. The Provisional Government represented an alliance between liberals and socialists who wanted political reform.

The initial soviet executive chairmen were Menshevik Nikolay Chkheidze

Nikoloz Chkheidze ( ka, ნიკოლოზ (კარლო) ჩხეიძე; russian: Никола́й (Карло) Семёнович Чхеи́дзе, translit=Nikolay (Karlo) Semyonovich Chkheidze) commonly known as Karlo Chkheidze ( � ...

, Matvey Skobelev and Alexander Kerensky

Alexander Fyodorovich Kerensky, ; original spelling: ( – 11 June 1970) was a Russian lawyer and revolutionary who led the Russian Provisional Government and the short-lived Russian Republic for three months from late July to early Nove ...

. The chairmen believed that the February Revolution was a "Bourgeois revolution" about bringing capitalist development to Russia instead of socialism. The center-left was well represented, and the government was initially chaired by a liberal aristocrat, Prince Georgy Yevgenyevich Lvov, a man with no connections to any official party. The Provisional government included 9 Duma

A duma (russian: дума) is a Russian assembly with advisory or legislative functions.

The term ''boyar duma'' is used to refer to advisory councils in Russia from the 10th to 17th centuries. Starting in the 18th century, city dumas were for ...

deputies and 6 from the Kadet

)

, newspaper = ''Rech''

, ideology = ConstitutionalismConstitutional monarchismLiberal democracyParliamentarism Political pluralismSocial liberalism

, position = Centre to centre-left

, international =

, colours ...

party in ministerial positional, representing professional and business interests, the bourgeoisie. As the left moved further left in Russia over the course of 1917, the Kadets became the main conservative party. Despite this, the provisional government strove to implement further left-leaning policies with the repeal of the death penalty, amnesty for political prisoners, and freedom of the press.

Dual Power was not prevalent outside of the capital and political systems varied from province to province. One example of a system gathered the educated public, workers, and soldiers to facilitate order and food systems, democratic elections, and the removal of tsarist officials. In a short amount of time, 3,000 deputies were elected to the Petrograd Soviet. The Soviet quickly became the representative body responsible for fighting for workers and soldiers hopes for "bread, peace, and land". In the spring of 1917, 700 soviets were established across Russia, equalling about a third of the population, representing the proletariat and their interests. The soviets spent their time pushing for a constituent assembly rather than swaying the public to believe they were a more morally sound means of governing.

Long-term effects

After the abdication of the throne by the Tsar, the Provisional Government declared itself the new form of authority. The Provisional Government sharedKadet

)

, newspaper = ''Rech''

, ideology = ConstitutionalismConstitutional monarchismLiberal democracyParliamentarism Political pluralismSocial liberalism

, position = Centre to centre-left

, international =

, colours ...

views. The Kadets began to be seen as a conservative political party and as "state-minded" by other Russians. At the same time that the Provisional Government was put into place, the Soviet Executive Committee was also forming. The soviets represented workers and soldiers, while the Provisional Government represented the middle and upper social classes. The soviets also gained support from Social Revolutionists and Mensheviks when the two groups realized that they did not want to support the Provisional Government. When these two powers existed at the same time, "dual power" was created. The Provisional Government was granted formal authority, but the Soviet Executive Committee had the support of the people resulting in political unrest until the Bolshevik takeover in October.

During the

During the April Crisis

The April Crisis, which occurred in Russia throughout April 1917, broke out in response to a series of political and public controversies. Conflict over Russia's foreign policy goals tested the dual power arrangement between the Petrograd Sovie ...

(1917) Ivan Ilyin

Ivan Alexandrovich Ilyin or Il'in (Ива́н Алекса́ндрович Ильи́н, – 21 December 1954) was a Russian jurist, a dogmatic religious and political philosopher, an orator and conservative monarchist. He perceived the Febru ...

agreed with the Kadet

)

, newspaper = ''Rech''

, ideology = ConstitutionalismConstitutional monarchismLiberal democracyParliamentarism Political pluralismSocial liberalism

, position = Centre to centre-left

, international =

, colours ...

Minister of Foreign Affairs Pavel Milyukov who staunchly opposed Petrograd Soviet

The Petrograd Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies (russian: Петроградский совет рабочих и солдатских депутатов, ''Petrogradskiy soviet rabochikh i soldatskikh deputatov'') was a city council of P ...

demands for peace at any cost. Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

, exile

Exile is primarily penal expulsion from one's native country, and secondarily expatriation or prolonged absence from one's homeland under either the compulsion of circumstance or the rigors of some high purpose. Usually persons and peoples suf ...

d in neutral Switzerland, arrived in Petrograd from Zürich

Zürich () is the list of cities in Switzerland, largest city in Switzerland and the capital of the canton of Zürich. It is located in north-central Switzerland, at the northwestern tip of Lake Zürich. As of January 2020, the municipality has 43 ...

on 16 April O.S (29 April N.S). He immediately began to undermine the provisional government, issuing his April Theses

The April Theses (russian: апрельские тезисы, transliteration: ') were a series of ten directives issued by the Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin upon his April 1917 return to Petrograd from his exile in Switzerland via Germany ...

the next month. These theses were in favor of "Revolutionary defeatism

Revolutionary defeatism is a concept made most prominent by Vladimir Lenin in World War I. It is based on the Marxist idea of class struggle. Arguing that the proletariat could not win or gain in a capitalist war, Lenin declared its true enemy is ...

", which argues that the real enemy is those who send the proletariat into war, as opposed to the "imperialist

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

war" (whose "link to Capital" must be demonstrated to the masses) and the " social-chauvinists" (such as Georgi Plekhanov, the grandfather of Russian socialism), who supported the war. The theses were read by Lenin to a meeting of only Bolsheviks and again to a meeting of Bolsheviks and Mensheviks

The Mensheviks (russian: меньшевики́, from меньшинство 'minority') were one of the three dominant factions in the Russian socialist movement, the others being the Bolsheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries.

The factions eme ...

, both being extreme leftist parties, and was also published. He believed that the most effective way to overthrow the government was to be a minority party and to give no support to the Provisional Government. Lenin also tried to take control of the Bolshevik movement and attempted to win proletariat support by the use of slogans such as "Peace, bread and land", "End the war without annexations or indemnities", "All power to the Soviet" and "All land to those who work it".

Initially, Lenin and his ideas did not have widespread support, even among Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

. In what became known as the July Days

The July Days (russian: Июльские дни) were a period of unrest in Petrograd, Russia, between . It was characterised by spontaneous armed demonstrations by soldiers, sailors, and industrial workers engaged against the Russian Provisi ...

, approximately half a million soldiers, sailors, and workers, some of them armed, came out onto the streets of Petrograd in protest. The protesters seized automobiles, fought with people of authority, and often fired their guns into the air. The crowd was so uncontrollable that the Soviet leadership sent the Socialist Revolutionary Victor Chernov

Viktor Mikhailovich Chernov (russian: Ви́ктор Миха́йлович Черно́в; December 7, 1873 – April 15, 1952) was a Russian revolutionary and one of the founders of the Russian Socialist-Revolutionary Party. He was the primar ...

, a widely liked politician, to the streets to calm the crowd. The demonstrators, lacking leadership, disbanded and the government survived. Leaders of the Soviet placed the blame of the July Days on the Bolsheviks, as did the Provisional Government who issued arrest warrants for prominent Bolsheviks. Historians debated from early on whether this was a planned Bolshevik attempt to seize power or a strategy to plan a future coup. Lenin fled to Finland and other members of the Bolshevik party were arrested. Lvov was replaced by the Socialist Revolutionary

The Socialist Revolutionary Party, or the Party of Socialist-Revolutionaries (the SRs, , or Esers, russian: эсеры, translit=esery, label=none; russian: Партия социалистов-революционеров, ), was a major politi ...

minister Alexander Kerensky

Alexander Fyodorovich Kerensky, ; original spelling: ( – 11 June 1970) was a Russian lawyer and revolutionary who led the Russian Provisional Government and the short-lived Russian Republic for three months from late July to early Nove ...

as head of the Provisional Government.

Kerensky declared freedom of speech, ended capital punishment, released thousands of political prisoners, and tried to maintain Russian involvement in World War I. He faced many challenges related to the war: there were still very heavy military losses on the front; dissatisfied soldiers deserted in larger numbers than before; other political groups did their utmost to undermine him; there was a strong movement in favor of withdrawing Russia from the war, which was seen to be draining the country, and many who had initially supported it now wanted out; and there was a great shortage of food and supplies, which was very difficult to remedy in wartime conditions. All of these were highlighted by the soldiers, urban workers, and peasants who claimed that little had been gained by the February Revolution. Kerensky was expected to deliver on his promises of jobs, land, and food, and failed to do so. In August 1917 Russian socialists assembled for a conference on defense, which resulted in a split between the Bolsheviks, who rejected the continuation of the war, and moderate socialists.

The Kornilov Affair arose when Commander-in-Chief of the Army, General Lavr Kornilov, directed an army under Aleksandr Krymov to march toward Petrograd with Kerensky's agreement. Although the details remain sketchy, Kerensky appeared to become frightened by the possibility of a coup, and the order was countermanded. (Historian Richard Pipes is adamant that the episode was engineered by Kerensky). On 27 August O.S (9 September N.S), feeling betrayed by the Kerensky government, who had previously agreed with his views on how to restore order to Russia, Kornilov pushed on towards Petrograd. With few troops to spare on the front, Kerensky was turned to the Petrograd Soviet for help. Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

, Mensheviks

The Mensheviks (russian: меньшевики́, from меньшинство 'minority') were one of the three dominant factions in the Russian socialist movement, the others being the Bolsheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries.

The factions eme ...

and Socialist Revolutionaries

The Socialist Revolutionary Party, or the Party of Socialist-Revolutionaries (the SRs, , or Esers, russian: эсеры, translit=esery, label=none; russian: Партия социалистов-революционеров, ), was a major politi ...

confronted the army and convinced them to stand down. Right-wingers felt betrayed, and the left-wingers were resurgent. On 1 September O.S. (14 September N.S.) Kerensky formally abolished the monarchy and proclaimed the creation of the Russian Republic

The Russian Republic,. referred to as the Russian Democratic Federal Republic. in the 1918 Constitution, was a short-lived state which controlled, ''de jure'', the territory of the former Russian Empire after its proclamation by the Rus ...

. On October 24, Kerensky accused the Bolsheviks of treason. After the Bolshevik walkout, some of the remaining delegates continued to stress that ending the war as soon as possible was beneficial to the nation.

Pressure from the Allies to continue the war against Germany put the government under increasing strain. The conflict between the "diarchy" became obvious, and ultimately the regime and the dual power formed between the Petrograd Soviet and the Provisional Government, instigated by the February Revolution, was overthrown by the Bolsheviks in the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mome ...

.

Historiography

When discussing the historiography of the February Revolution there are three historical interpretations which are relevant: Communist, Liberal, and Revisionist. These three different approaches exist separately from one another because of their respective beliefs of what ultimately caused the collapse of a Tsarist government in February.

* Communist historians present a story in which the masses that brought about revolution in February were organized groups of 'modernizing' peasants who were bringing about an era of both industrialization and freedom. Communist historian Boris Sokolov has been outspoken about the belief that the revolution in February was a coming together of the people and was more positive than the October revolution. Communist historians consistently place little emphasis on the role of World War I (WWI) in leading to the February Revolution.

* In contrast, Liberal perspectives of the February Revolution almost always acknowledge WWI as a catalyst to revolution. On the whole, though, Liberal historians credit the Bolsheviks with the ability to capitalize on the worry and dread instilled in Russian citizens because of WWI. The overall message and goal of the February Revolution, according to the Liberal perspective, was ultimately democracy; the proper climate and attitude had been created by WWI and other political factors which turned public opinion against the Tsar.

* Revisionist historians present a timeline where the revolution in February was far less inevitable than the liberals and communists would make it seem. Revisionists track the mounting pressure on the Tsarist regime back further than the other two groups to unsatisfied peasants in the countryside upset over matters of land-ownership. This tension continued to build into 1917 when dissatisfaction became a full-blown institutional crisis incorporating the concerns of many groups. Revisionist historian Richard Pipes has been outspoken about his anti-communist approach to the Russian Revolution.

::''"Studying Russian history from the West European perspective, one also becomes conscious of the effect that the absence of feudalism had on Russia. Feudalism had created in the West networks of economic and political institutions that served the central state... once

When discussing the historiography of the February Revolution there are three historical interpretations which are relevant: Communist, Liberal, and Revisionist. These three different approaches exist separately from one another because of their respective beliefs of what ultimately caused the collapse of a Tsarist government in February.

* Communist historians present a story in which the masses that brought about revolution in February were organized groups of 'modernizing' peasants who were bringing about an era of both industrialization and freedom. Communist historian Boris Sokolov has been outspoken about the belief that the revolution in February was a coming together of the people and was more positive than the October revolution. Communist historians consistently place little emphasis on the role of World War I (WWI) in leading to the February Revolution.

* In contrast, Liberal perspectives of the February Revolution almost always acknowledge WWI as a catalyst to revolution. On the whole, though, Liberal historians credit the Bolsheviks with the ability to capitalize on the worry and dread instilled in Russian citizens because of WWI. The overall message and goal of the February Revolution, according to the Liberal perspective, was ultimately democracy; the proper climate and attitude had been created by WWI and other political factors which turned public opinion against the Tsar.

* Revisionist historians present a timeline where the revolution in February was far less inevitable than the liberals and communists would make it seem. Revisionists track the mounting pressure on the Tsarist regime back further than the other two groups to unsatisfied peasants in the countryside upset over matters of land-ownership. This tension continued to build into 1917 when dissatisfaction became a full-blown institutional crisis incorporating the concerns of many groups. Revisionist historian Richard Pipes has been outspoken about his anti-communist approach to the Russian Revolution.

::''"Studying Russian history from the West European perspective, one also becomes conscious of the effect that the absence of feudalism had on Russia. Feudalism had created in the West networks of economic and political institutions that served the central state... once he central state

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...

replaced the feudal system, as a source of social support and relative stability. Russia knew no feudalism in the traditional sense of the word, since, after the emergence of the Muscovite monarchy in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, all landowners were tenants-in-chief of the Crown, and subinfeudation was unknown. As a result, all power was concentrated in the Crown."'' — (Pipes, Richard. A Concise History of the Russian Revolution. New York: Vintage, 1996.)

Out of these three approaches, all of them have received modern criticism. The February Revolution is seen by many present-day scholars as an event which gets "mythologized".

See also

* 1905 Russian Revolution * ''Nicholas and Alexandra

''Nicholas and Alexandra'' is a 1971 British epic historical drama film directed by Franklin J. Schaffner, from a screenplay written by James Goldman and Edward Bond, based on Robert K. Massie's 1967 book of the same name, which is a partia ...

'', a biographical film of the Tsar and his family

* Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and ad ...

* Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

* Women in the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolutions of 1917 saw the collapse of the Russian Empire, a short-lived provisional government, and the creation of the world's first socialist state under the Bolsheviks. They made explicit commitments to promote the equality of men ...

* World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

* Index of articles related to the Russian Revolution and Civil War

* Bibliography of the Russian Revolution and Civil War

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * Online sources *External links

* Read, ChristopherRevolutions (Russian Empire)

, in

* Melancon, Michael S.

Social Conflict and Control, Protest and Repression (Russian Empire)

, in

* Sanborn, Joshua A.

Russian Empire

, in

* Gaida, Fedor Aleksandrovich

Governments, Parliaments and Parties (Russian Empire)

, in

* Albert, Gleb

Labour Movements, Trade Unions and Strikes (Russian Empire)

, in

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20100107023609/http://www.thecorner.org/hist/russia/revo1917.htm Russian Revolutions 1905–1917

Leon Trotsky's account

Лютнева революція. Жіночий бунт, який знищив Російську імперію (February Revolution. Female mutiny that destroyed the Russian Empire)

Ukrayinska Pravda

''Ukrainska Pravda'' ( uk, Українська правда, lit=Ukrainian Truth) is a Ukrainian online newspaper founded by Georgiy Gongadze on 16 April 2000 (the day of the Ukrainian constitutional referendum). Published mainly in Ukrai ...

{{Authority control

1917 in Russia

Nicholas II of Russia

Russian Provisional Government

*

March 1917 events

Dissolution of the Russian Empire