Faulkner Award For Fiction Winners on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William Cuthbert Faulkner (; September 25, 1897 – July 6, 1962) was an American writer known for his novels and short stories set in the fictional

. ''Past winners & finalists by category''. The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved 2012-03-28. Faulkner died from a heart attack on July 6, 1962, following a fall from his horse the prior month.

William Cuthbert Faulkner was born on September 25, 1897 in New Albany, Mississippi, the first of four sons of Murry Cuthbert Faulkner (1870–1932) and Maud Butler (1871–1960).MWP: William Faulkner (1897–1962)

William Cuthbert Faulkner was born on September 25, 1897 in New Albany, Mississippi, the first of four sons of Murry Cuthbert Faulkner (1870–1932) and Maud Butler (1871–1960).MWP: William Faulkner (1897–1962)

, OleMiss.edu; accessed September 26, 2017. His family was upper middle-class, but "not quite of the old feudal cotton aristocracy". After Maud rejected Murry's plan to become a rancher in Texas, the family moved to

When he was 17, Faulkner met

When he was 17, Faulkner met

''William Faulkner''

, New York: Oxford University Press, 2007; In 1922, his poem "Portrait" was published in the New Orleans literary magazine ''Double Dealer''. The magazine published his "New Orleans" short story collection three years later. After dropping out, he took a series of odd jobs: at a New York City bookstore, a carpenter in Oxford, and as the Ole Miss postmaster. He resigned from the post office with the declaration: "I will be damned if I propose to be at the beck and call of every itinerant scoundrel who has two cents to invest in a postage stamp."

While most writers of Faulkner's

While most writers of Faulkner's

In autumn 1928, just after his 31st birthday, Faulkner began working on ''

In autumn 1928, just after his 31st birthday, Faulkner began working on ''

''William Faulkner and Southern History''

, New York: Oxford University Press, 1993; . He made money on his 1931 novel, ''

By 1932, Faulkner was in need of money. He asked Wasson to sell the serialization rights for his newly completed novel, ''Light in August'', to a magazine for $5,000, but none accepted the offer. Then

By 1932, Faulkner was in need of money. He asked Wasson to sell the serialization rights for his newly completed novel, ''Light in August'', to a magazine for $5,000, but none accepted the offer. Then

Faulkner was awarded the

Faulkner was awarded the

From the early 1920s to the outbreak of World War II, Faulkner published 13 novels and many short stories. This body of work formed the basis of his reputation and earned him the Nobel Prize at age 52. Faulkner's prodigious output include celebrated novels such as ''

From the early 1920s to the outbreak of World War II, Faulkner published 13 novels and many short stories. This body of work formed the basis of his reputation and earned him the Nobel Prize at age 52. Faulkner's prodigious output include celebrated novels such as ''

.

.

"'I'm Afraid I've Got Involved With a Nut': New Faulkner Letters." Southern Literary Journal 47.1 (2014): 98–114.

* Kerr, Elizabeth Margaret, and Kerr, Michael M. ''William Faulkner's Yoknapatawpha: A Kind of Keystone in the Universe''. Fordham Univ Press, 1985 , * *Liénard-Yeterian, Marie. 'Faulkner et le cinéma', Paris: Michel Houdiard Editeur, 2010. * * * * Sensibar, Judith L. ''The Origins of Faulkner's Art''. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1984. * Sensibar, Judith L. ''Faulkner and Love: The Women Who Shaped His Art, A Biography''. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008. * Sensibar, Judith L. ''Vision in Spring''. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1984. . * * * * * * *

William Faulkner Papers

at the

William Faulkner Collection

at the

Digital Yoknapatawpha

Faulkner at Virginia: An Audio Archive

{{DEFAULTSORT:Faulkner, William 1897 births 1962 deaths 20th-century American dramatists and playwrights 20th-century American male writers 20th-century American novelists 20th-century American poets 20th-century American screenwriters 20th-century American short story writers Accidental deaths in Mississippi American erotica writers American male novelists American male screenwriters American male short story writers American Nobel laureates British Army personnel of World War I Deaths by horse-riding accident in the United States Lost Generation writers Mississippi postmasters Modernist writers National Book Award winners Nobel laureates in Literature Novelists from Mississippi O. Henry Award winners People from New Albany, Mississippi People from Oxford, Mississippi People from Ripley, Mississippi Pulitzer Prize for Fiction winners Screenwriters from Mississippi Southern United States in fiction University of Virginia alumni Writers of American Southern literature Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

Yoknapatawpha County

Yoknapatawpha County () is a fictional Mississippi county created by the American author William Faulkner, largely based upon and inspired by Lafayette County, Mississippi, and its county seat of Oxford (which Faulkner renamed "Jefferson"). Faulk ...

, based on Lafayette County, Mississippi

Lafayette County is a county in the U.S. state of Mississippi. At the 2010 census, the population was 47,351. Its county seat is Oxford. The local pronunciation of the name is "la-FAY-et." The county's name honors Marquis de Lafayette, a French ...

, where Faulkner spent most of his life. A Nobel Prize laureate

The Nobel Prizes ( sv, Nobelpriset, no, Nobelprisen) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institutet, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make out ...

, Faulkner is one of the most celebrated writers of American literature

American literature is literature written or produced in the United States of America and in the colonies that preceded it. The American literary tradition thus is part of the broader tradition of English-language literature, but also inc ...

and is considered the greatest writer of Southern literature

Southern United States literature consists of American literature written about the Southern United States or by writers from the region. Literature written about the American South first began during the colonial era, and developed significan ...

.

Born in New Albany, Mississippi

New Albany is a city in and the county seat of Union County, Mississippi, United States. According to the 2020 United States Census, the population was 7,626.

History

New Albany was first organized in 1840 at the site of a grist mill and saw mil ...

, Faulkner's family moved to Oxford, Mississippi

Oxford is a city and college town in the U.S. state of Mississippi. Oxford lies 75 miles (121 km) south-southeast of Memphis, Tennessee, and is the county seat of Lafayette County. Founded in 1837, it was named after the British city of Oxf ...

when he was a young child. With the outbreak of World War I, he joined the Royal Canadian Air Force

The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF; french: Aviation royale canadienne, ARC) is the air and space force of Canada. Its role is to "provide the Canadian Forces with relevant, responsive and effective airpower". The RCAF is one of three environm ...

but did not serve in combat. Returning to Oxford, he attended the University of Mississippi

The University of Mississippi (byname Ole Miss) is a public research university that is located adjacent to Oxford, Mississippi, and has a medical center in Jackson. It is Mississippi's oldest public university and its largest by enrollment.

...

for three semesters before dropping out. He moved to New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

, where he wrote his first novel ''Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Soldiers' Pay

''Soldiers' Pay'' is the first novel published by the American author William Faulkner. It was originally published by Boni & Liveright on February 25, 1926. It is unclear if ''Soldiers' Pay'' is the first novel written by Faulkner. It is however t ...

'' (1925). He went back to Oxford and wrote ''Sartoris

''Sartoris'' is a novel, first published in 1929, by the American author William Faulkner. It portrays the decay of the Mississippi aristocracy following the social upheaval of the American Civil War. The 1929 edition is an abridged version of ...

'' (1927), his first work set in the fictional Yoknapatawpha County. In 1929, he published ''The Sound and the Fury

''The Sound and the Fury'' is a novel by the American author William Faulkner. It employs several narrative styles, including stream of consciousness. Published in 1929, ''The Sound and the Fury'' was Faulkner's fourth novel, and was not immedi ...

''. The following year, he wrote ''As I Lay Dying

''As I Lay Dying'' is a 1930 Southern Gothic novel by American author William Faulkner. Faulkner's fifth novel, it is consistently ranked among the best novels of 20th-century literature.The New Lifetime Reading Plan: The Classical Guide to Wor ...

''. Seeking greater economic success, he went to Hollywood

Hollywood usually refers to:

* Hollywood, Los Angeles, a neighborhood in California

* Hollywood, a metonym for the cinema of the United States

Hollywood may also refer to:

Places United States

* Hollywood District (disambiguation)

* Hollywood, ...

to work as a screenwriter.

Faulkner's renown reached its peak upon the publication of Malcolm Cowley

Malcolm Cowley (August 24, 1898 – March 27, 1989) was an American writer, editor, historian, poet, and literary critic. His best known works include his first book of poetry, ''Blue Juniata'' (1929), his lyrical memoir, ''Exile's Return ...

's ''The Portable Faulkner'' and his being awarded the 1949 Nobel Prize in Literature

The 1949 Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded the American author William Faulkner (1897–1962) "for his powerful and artistically unique contribution to the modern American novel." The prize was awarded in 1950. The Nobel Committee for Literatu ...

. He is the only Mississippi-born Nobel laureate. Two of his works, ''A Fable

''A Fable'' is a 1954 novel written by the American author William Faulkner. He spent more than a decade and tremendous effort on it, and aspired for it to be "the best work of my life and maybe of my time".

It won the Pulitzer Prize and the Nat ...

'' (1954) and his last novel ''The Reivers

''The Reivers: A Reminiscence'', published in 1962, is the last novel by the American author William Faulkner. The bestselling novel was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1963. Faulkner previously won this award for his book ''A Fable'', ...

'' (1962), won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction is one of the seven American Pulitzer Prizes that are annually awarded for Letters, Drama, and Music. It recognizes distinguished fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life, published during ...

."Fiction". ''Past winners & finalists by category''. The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved 2012-03-28. Faulkner died from a heart attack on July 6, 1962, following a fall from his horse the prior month.

Life

Childhood and heritage

William Cuthbert Faulkner was born on September 25, 1897 in New Albany, Mississippi, the first of four sons of Murry Cuthbert Faulkner (1870–1932) and Maud Butler (1871–1960).MWP: William Faulkner (1897–1962)

William Cuthbert Faulkner was born on September 25, 1897 in New Albany, Mississippi, the first of four sons of Murry Cuthbert Faulkner (1870–1932) and Maud Butler (1871–1960).MWP: William Faulkner (1897–1962), OleMiss.edu; accessed September 26, 2017. His family was upper middle-class, but "not quite of the old feudal cotton aristocracy". After Maud rejected Murry's plan to become a rancher in Texas, the family moved to

Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, Mississippi in 1902, Minter (1980), p. 8. where Faulkner's father established a livery stable and hardware store before becoming the University of Mississippi

The University of Mississippi (byname Ole Miss) is a public research university that is located adjacent to Oxford, Mississippi, and has a medical center in Jackson. It is Mississippi's oldest public university and its largest by enrollment.

...

's business manager. Except for short periods elsewhere, Faulkner lived in Oxford for the rest of his life.

Faulkner spent his boyhood listening to stories which were told to him by his elders including stories which were about the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, slavery, the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

, and the Faulkner family.Minter, David L. ''William Faulkner, His Life and Work''. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980; Young William was greatly influenced by the history of his family and the region in which he lived. Mississippi marked his sense of humor, his sense of the tragic position of "black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white have o ...

and white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White on ...

" Americans

Americans are the Citizenship of the United States, citizens and United States nationality law, nationals of the United States, United States of America.; ; Although direct citizens and nationals make up the majority of Americans, many Multi ...

, his characterization of Southern characters, and his timeless themes, including fiercely intelligent people who are dwelling behind the façades of good ol' boy

An old boy network (also known as old boys' network, ol' boys' club, old boys' club, old boys' society, good ol' boys club, or good ol' boys system) is an informal system in which wealthy men with similar social or educational background help ...

s and simpletons. He was particularly influenced by stories of his great-grandfather William Clark Falkner

William Clark Falkner (July 6, 1825 or 1826 – November 6, 1889) was a soldier, lawyer, politician, businessman, and author in northern Mississippi. He is most notable for the influence he had on the work of his great-grandson, author William F ...

, who had become a near legendary figure in North Mississippi. Born into poverty, he was a strict disciplinarian and was a Confederate colonel. Tried and acquited twice on charges of murder, he became a member of the Mississippi House and became a part-owner of a railroad before being murdered by his co-owner. Many aspects of his biography were incorporated into his later works.

Faulkner initially excelled in school and skipped the second grade. However, beginning somewhere in the fourth and fifth grades of his schooling, Faulkner became a much quieter and more withdrawn child. He occasionally played hooky and became indifferent about schoolwork. Instead, he took an interest in studying the history of Mississippi

The history of the state of Mississippi extends back to thousands of years of indigenous peoples. Evidence of their cultures has been found largely through archeological excavations, as well as existing remains of earthwork mounds built thousands ...

. The decline of his performance in school continued, and Faulkner wound up repeating the eleventh and twelfth grades, never graduating from high school. As a teenager in Oxford, Faulkner dated Estelle Oldham (1897–1972), the popular daughter of Major Lemuel and Lida Oldham, and he also believed he would marry her. However, Estelle dated other boys during their romance, and, in 1918, Cornell Franklin

Cornell Sidney Franklin (1892–1959) was an American lawyer and judge and also served as the chairman of the Shanghai Municipal Council from 1937 to 1940.

Early life

Franklin was born April 1, 1892, in Columbus, Mississippi, United States. He ...

(five years Faulkner's senior) proposed marriage to her before Faulkner did. She accepted. Parini (2004), pp. 36–37.

Trip to the North and early writings

When he was 17, Faulkner met

When he was 17, Faulkner met Phil Stone

Philip Avery Stone (23 February 1893 – 20 February 1967) also known as Phil Stone, was an attorney from Oxford, Mississippi and mentor to William Faulkner. Educated at the University of Mississippi and Yale, Stone had a law office in Oxfo ...

, who became an important early influence on his writing. Stone was four years his senior and came from one of Oxford's older families; he was passionate about literature and had bachelor's degrees from Yale

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wor ...

and the University of Mississippi. Stone read and was impressed by some of Faulkner's early poetry, becoming one of the first to recognize and encourage Faulkner's talent. Stone mentored the young Faulkner, introducing him to the works of writers like James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influential and important writers of ...

, who influenced Faulkner's own writing. In his early 20s, Faulkner gave poems and short stories he had written to Stone in hopes of their being published. Stone sent these to publishers, but they were uniformly rejected. In spring 1918, Faulkner traveled to live with Stone at Yale, his first trip to the North. Through Stone, Faulkner met writers like Sherwood Anderson

Sherwood Anderson (September 13, 1876 – March 8, 1941) was an American novelist and short story writer, known for subjective and self-revealing works. Self-educated, he rose to become a successful copywriter and business owner in Cleveland and ...

, Robert Frost

Robert Lee Frost (March26, 1874January29, 1963) was an American poet. His work was initially published in England before it was published in the United States. Known for his realistic depictions of rural life and his command of American colloq ...

, and Ezra Pound

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (30 October 1885 – 1 November 1972) was an expatriate American poet and critic, a major figure in the early modernist poetry movement, and a Fascism, fascist collaborator in Italy during World War II. His works ...

. O'Connor (1959), p. 5.

Faulkner attempted to join the US Army, but was rejected for being under weight and his short stature of 5'5. Although he initially planned to join the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

in hopes of being commissioned as an officer, Faulkner then joined the Canadian RAF with a forged letter of reference and left Yale to receive training in Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the ancho ...

. Accounts of Faulkner being rejected from the United States Army Air Service

The United States Army Air Service (USAAS)Craven and Cate Vol. 1, p. 9 (also known as the ''"Air Service"'', ''"U.S. Air Service"'' and before its legislative establishment in 1920, the ''"Air Service, United States Army"'') was the aerial war ...

due to his short stature, despite wide publication, are false. Despite his claims, records indicate that Faulkner was never actually a member of the British Royal Flying Corps

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colors =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries =

, decorations ...

and never saw active service during the First World War. Despite claiming so in his letters, Faulkner did not receive cockpit training or even fly. Faulkner returned to Oxford in December 1918, where he told acquaintances false war-stories and even faked a war wound.

In 1918, Faulkner's surname changed from "Falkner" to "Faulkner". According to one story, a careless typesetter made an error. When the misprint appeared on the title page of his first book, Faulkner was asked whether he wanted the change. He supposedly replied, "Either way suits me." In adolescence, Faulkner began writing poetry almost exclusively. He did not write his first novel until 1925. His literary influences are deep and wide. He once stated that he modeled his early writing on the Romantic era

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

in late 18th- and early 19th-century England.

He attended the University of Mississippi, enrolling in 1919, studying for three semesters before dropping out in November 1920. Faulkner joined the Sigma Alpha Epsilon

Sigma Alpha Epsilon (), commonly known as SAE, is a North American Greek-letter social college fraternity. It was founded at the University of Alabama on March 9, 1856. Of all existing national social fraternities today, Sigma Alpha Epsilon is t ...

fraternity, and pursued his dream to become a writer. He skipped classes often and received a "D" grade in English. However, some of his poems were published in campus publications.Coughlan, Robert. ''The Private World of William Faulkner'', New York: Harper & Brothers, 1953.Porter, Carolyn''William Faulkner''

, New York: Oxford University Press, 2007; In 1922, his poem "Portrait" was published in the New Orleans literary magazine ''Double Dealer''. The magazine published his "New Orleans" short story collection three years later. After dropping out, he took a series of odd jobs: at a New York City bookstore, a carpenter in Oxford, and as the Ole Miss postmaster. He resigned from the post office with the declaration: "I will be damned if I propose to be at the beck and call of every itinerant scoundrel who has two cents to invest in a postage stamp."

New Orleans and early novels

While most writers of Faulkner's

While most writers of Faulkner's generation

A generation refers to all of the people born and living at about the same time, regarded collectively. It can also be described as, "the average period, generally considered to be about 20–30 years, during which children are born and gr ...

travelled to and lived in Europe, Faulkner remained writing in the United States. Pikoulis (1982), p. ix. Faulkner spent the first half of 1925 in New Orleans, Louisiana

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

, where many Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

bohemian

Bohemian or Bohemians may refer to:

*Anything of or relating to Bohemia

Beer

* National Bohemian, a brand brewed by Pabst

* Bohemian, a brand of beer brewed by Molson Coors

Culture and arts

* Bohemianism, an unconventional lifestyle, origin ...

artists and writers lived, specifically in the French Quarter

The French Quarter, also known as the , is the oldest neighborhood in the city of New Orleans. After New Orleans (french: La Nouvelle-Orléans) was founded in 1718 by Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, the city developed around the ("Old Squ ...

where Faulkner lived beginning in March. During his time in New Orleans, Faulkner's focus drifted from poetry to prose and his literary style made a marked transition from Victorian to modernist

Modernism is both a philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new forms of art, philosophy, an ...

. ''The Times-Picayune

''The Times-Picayune/The New Orleans Advocate'' is an American newspaper published in New Orleans, Louisiana, since January 25, 1837. The current publication is the result of the 2019 acquisition of ''The Times-Picayune'' (itself a result of th ...

'' published several of his short works of prose. After being directly influenced by Sherwood Anderson

Sherwood Anderson (September 13, 1876 – March 8, 1941) was an American novelist and short story writer, known for subjective and self-revealing works. Self-educated, he rose to become a successful copywriter and business owner in Cleveland and ...

, he made his first attempt at fiction writing. Anderson assisted in the publication of ''Soldiers' Pay'' and ''Mosquitoes

Mosquitoes (or mosquitos) are members of a group of almost 3,600 species of small flies within the family Culicidae (from the Latin ''culex'' meaning "gnat"). The word "mosquito" (formed by ''mosca'' and diminutive ''-ito'') is Spanish for "litt ...

'', Faulkner's second novel, set in New Orleans, by recommending them to his publisher.Hannon, Charles. "Faulkner, William". ''The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Literature''. Jay Parini (2004), Oxford University Press, Inc. The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Literature: (e-reference edition). Oxford University Press. The miniature house at 624 Pirate's Alley, just around the corner from St. Louis Cathedral in New Orleans, is now the site of Faulkner House Books, where it also serves as the headquarters of the Pirate's Alley Faulkner Society.

Also in New Orleans, Faulkner wrote his first novel, ''Soldiers' Pay

''Soldiers' Pay'' is the first novel published by the American author William Faulkner. It was originally published by Boni & Liveright on February 25, 1926. It is unclear if ''Soldiers' Pay'' is the first novel written by Faulkner. It is however t ...

.'' ''Soldiers' Pay'' and his other early works were written in a style similar to contemporaries Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer, and journalist. His economical and understated style—which he termed the iceberg theory—had a strong influence on 20th-century fic ...

and F. Scott Fitzgerald

Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald (September 24, 1896 – December 21, 1940) was an American novelist, essayist, and short story writer. He is best known for his novels depicting the flamboyance and excess of the Jazz Age—a term he popularize ...

, at times nearly exactly appropriating phrases.

During the summer of 1927, Faulkner wrote his first novel set in his fictional Yoknapatawpha County, titled ''Flags in the Dust

''Flags in the Dust'' is a novel by the American author William Faulkner, completed in 1927. His publisher heavily edited the manuscript with Faulkner's reluctant consent, removing about 40,000 words in the process. That version was published as ...

.'' This novel drew heavily from the traditions and history of the South, in which Faulkner had been engrossed in his youth. He was extremely proud of the novel upon its completion and he believed it a significant step up from his previous two novels—however, when submitted for publication to Boni & Liveright

Boni & Liveright (pronounced "BONE-eye" and "LIV-right") is an American trade book publisher established in 1917 in New York City by Albert Boni and Horace Liveright. Over the next sixteen years the firm, which changed its name to Horace Live ...

, it was rejected. Faulkner was devastated by this rejection but he eventually allowed his literary agent, Ben Wasson, to edit the text, and the novel was published in 1929 as ''Sartoris

''Sartoris'' is a novel, first published in 1929, by the American author William Faulkner. It portrays the decay of the Mississippi aristocracy following the social upheaval of the American Civil War. The 1929 edition is an abridged version of ...

.'' The work was notable in that it was his first novel that dealt with the Civil War rather than the contemporary emphasis on World War I and its legacy.

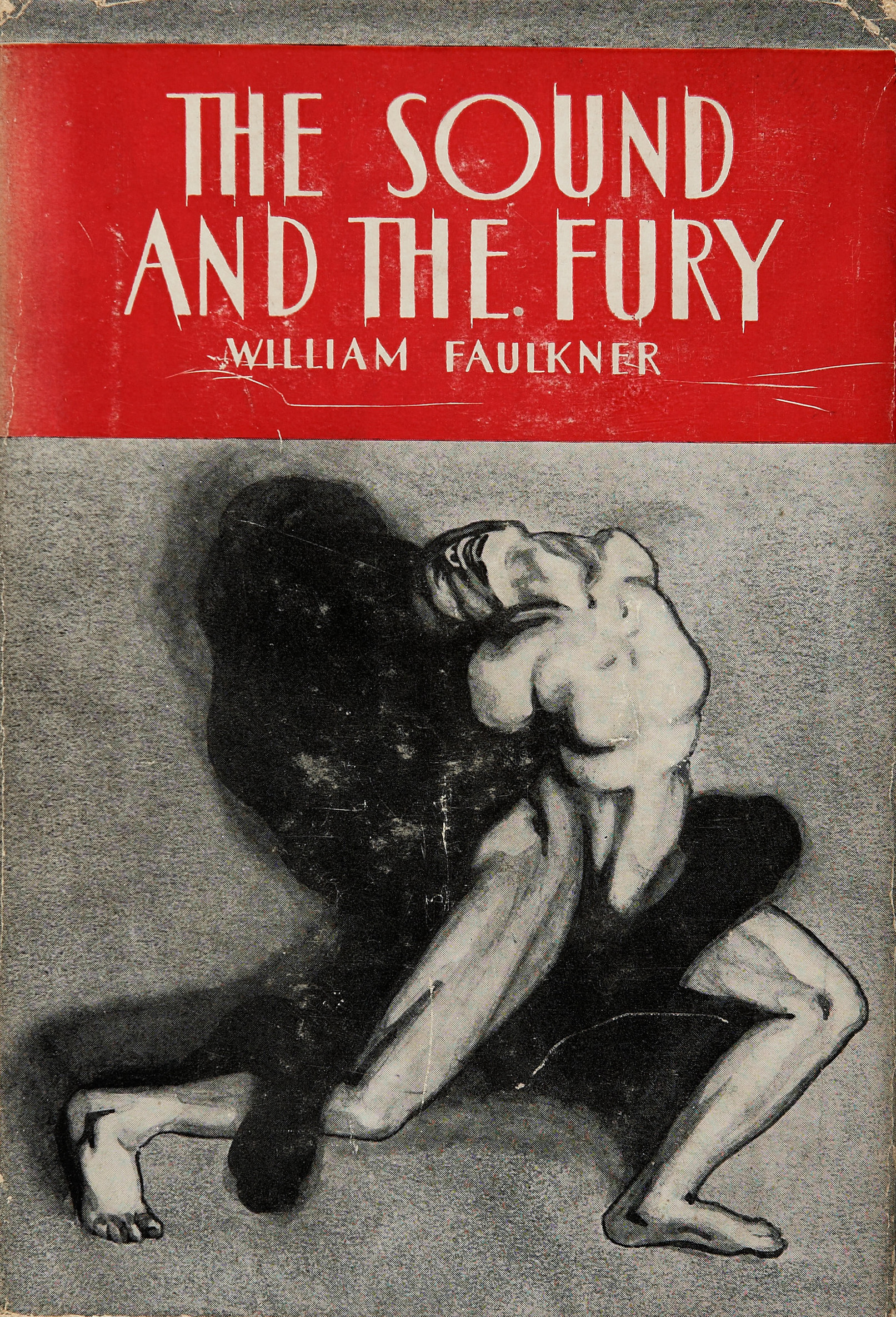

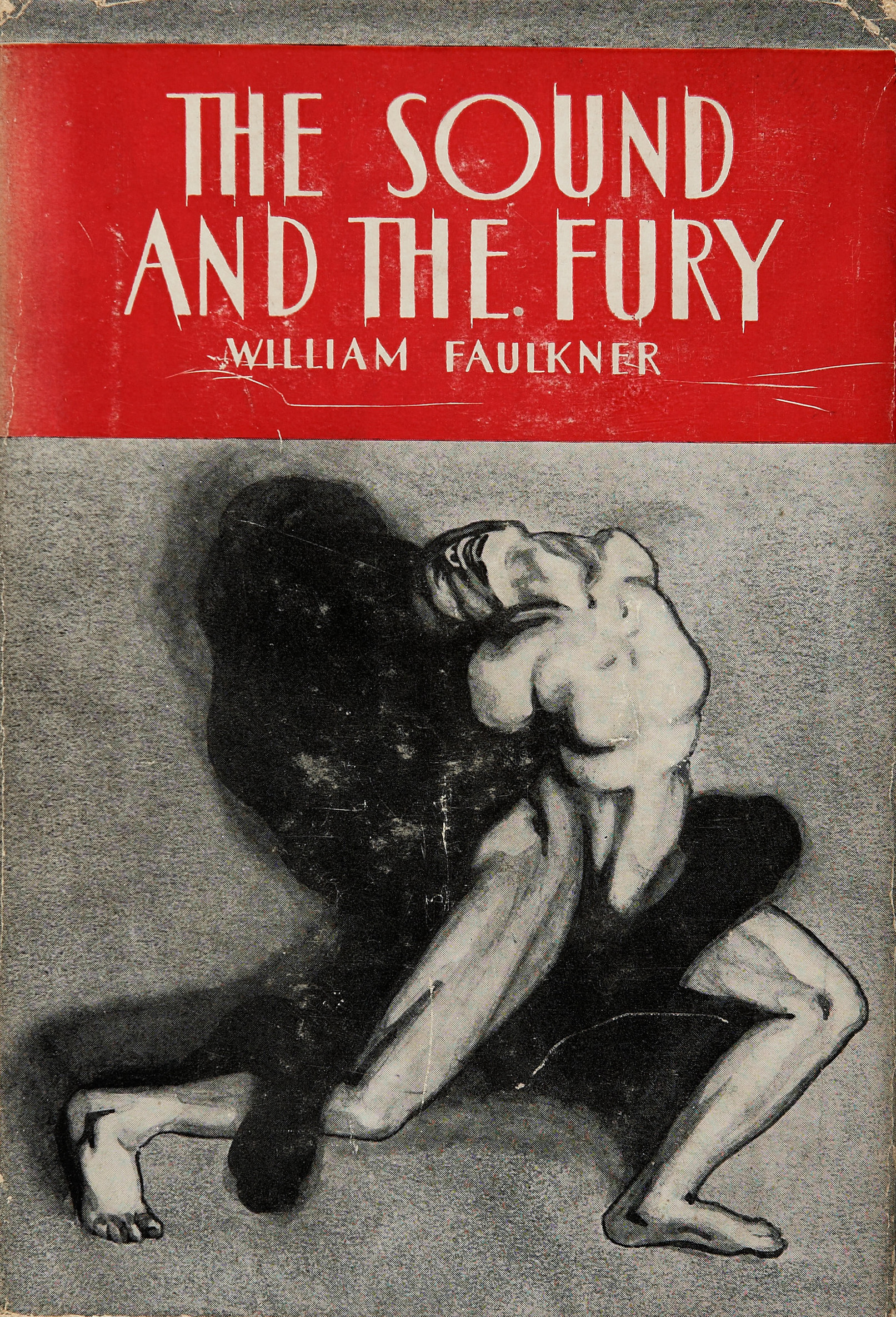

''The Sound and the Fury''

In autumn 1928, just after his 31st birthday, Faulkner began working on ''

In autumn 1928, just after his 31st birthday, Faulkner began working on ''The Sound and the Fury

''The Sound and the Fury'' is a novel by the American author William Faulkner. It employs several narrative styles, including stream of consciousness. Published in 1929, ''The Sound and the Fury'' was Faulkner's fourth novel, and was not immedi ...

''. He started by writing three short stories about a group of children with the last name Compson, but soon began to feel that the characters he had created might be better suited for a full-length novel. Perhaps as a result of disappointment in the initial rejection of ''Flags in the Dust'', Faulkner had now become indifferent to his publishers and wrote this novel in a much more experimental style. In describing the writing process for this work, Faulkner later said, "One day I seemed to shut the door between me and all publisher's addresses and book lists. I said to myself, 'Now I can write.'" After its completion, Faulkner insisted that Wasson not do any editing or add any punctuation for clarity.

In 1929, Faulkner married Estelle Oldham, with Andrew Kuhn serving as best man at the wedding. Estelle brought with her two children from her previous marriage to Cornell Franklin

Cornell Sidney Franklin (1892–1959) was an American lawyer and judge and also served as the chairman of the Shanghai Municipal Council from 1937 to 1940.

Early life

Franklin was born April 1, 1892, in Columbus, Mississippi, United States. He ...

and Faulkner hoped to support his new family as a writer. Faulkner and Estelle later had a daughter, Jill, in 1933. He began writing ''As I Lay Dying

''As I Lay Dying'' is a 1930 Southern Gothic novel by American author William Faulkner. Faulkner's fifth novel, it is consistently ranked among the best novels of 20th-century literature.The New Lifetime Reading Plan: The Classical Guide to Wor ...

'' in 1929 while working night shifts at the University of Mississippi Power House The University of Mississippi Power House was located on the campus of the University of Mississippi in Oxford, Mississippi. The original building was constructed in 1908 as a central power plant for the entire campus.

Author William Faulkner was e ...

. The novel was published in 1930. Parini (2004), p. 142.

Beginning in 1930, Faulkner sent some of his short stories to various national magazines. Several of these were published and brought him enough income to buy a house in Oxford for his family, which he named Rowan Oak

Rowan Oak is William Faulkner's former home in Oxford, Mississippi. It is a primitive Greek Revival house built in the 1840s by Colonel Robert Sheegog, an Irish immigrant planter from Tennessee. Faulkner purchased the house when it was in disrepai ...

.Williamson, Joel''William Faulkner and Southern History''

, New York: Oxford University Press, 1993; . He made money on his 1931 novel, ''

Sanctuary

A sanctuary, in its original meaning, is a sacred place, such as a shrine. By the use of such places as a haven, by extension the term has come to be used for any place of safety. This secondary use can be categorized into human sanctuary, a saf ...

'', which was widely reviewed and read (but widely disliked for its perceived criticism of the South). With the onset of the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, Faulkner was not satisfied with his economic situation. With limited royalties from his work, he published short stories in magazines such as ''The Saturday Evening Post

''The Saturday Evening Post'' is an American magazine, currently published six times a year. It was issued weekly under this title from 1897 until 1963, then every two weeks until 1969. From the 1920s to the 1960s, it was one of the most widely c ...

'' to supplement his income. Bartunek (2017), p. 98.

''Light in August'' and Hollywood years

By 1932, Faulkner was in need of money. He asked Wasson to sell the serialization rights for his newly completed novel, ''Light in August'', to a magazine for $5,000, but none accepted the offer. Then

By 1932, Faulkner was in need of money. He asked Wasson to sell the serialization rights for his newly completed novel, ''Light in August'', to a magazine for $5,000, but none accepted the offer. Then MGM Studios

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc., also known as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures and abbreviated as MGM, is an American film, television production, distribution and media company owned by Amazon through MGM Holdings, founded on April 17, 1924 a ...

offered Faulkner work as a screenwriter in Hollywood. Faulkner was not an avid movie goer and had reservations about working in the movie industry. As André Bleikasten comments, he “was in dire need of money and had no idea how to get it…So he went to Hollywood.” Bleikasten (2017), p. 218. It has been noted that authors like Faulkner were not always hired for their writing prowess but "to enhance the prestige of the …writers who hired them." He arrived in Culver City, California

Culver City is a city in Los Angeles County, California, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population was 40,779. Founded in 1917 as a "whites only" sundown town, it is now an ethnically diverse city with what was called the "third-most d ...

, in May 1932. The job began a sporadic relationship with moviemaking and with California, which was difficult but he endured in order to earn "a consistent salary that supported his family back home."

Initially, he declared a desire to work on Mickey Mouse cartoons, not realizing that they were produced by Walt Disney Productions

The Walt Disney Company, commonly known as Disney (), is an American multinational mass media and entertainment conglomerate headquartered at the Walt Disney Studios complex in Burbank, California. Disney was originally founded on October ...

and not MGM. His first screenplay was for ''Today We Live

''Today We Live'' is a 1933 American pre-Code romance drama film produced and directed by Howard Hawks and starring Joan Crawford, Gary Cooper, Robert Young and Franchot Tone.

'', an adaptation of his short story "Turnabout", which received a mixed response. He then wrote a screen adaptation of ''Sartoris'' that was never produced. From 1932 to 1954, Faulkner worked on around 50 films. In early 1944, Faulkner wrote a screenplay adaptation of Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer, and journalist. His economical and understated style—which he termed the iceberg theory—had a strong influence on 20th-century fic ...

's novel ''To Have and Have Not

''To Have and Have Not'' is a novel by Ernest Hemingway published in 1937 by Charles Scribner's Sons. The book follows Harry Morgan, a fishing boat captain out of Key West, Florida. ''To Have and Have Not'' was Hemingway's second novel set in th ...

''. The film

A film also called a movie, motion picture, moving picture, picture, photoplay or (slang) flick is a work of visual art that simulates experiences and otherwise communicates ideas, stories, perceptions, feelings, beauty, or atmosphere ...

, which starred Lauren Bacall

Lauren Bacall (; born Betty Joan Perske; September 16, 1924 – August 12, 2014) was an American actress. She was named the 20th-greatest female star of classic Hollywood cinema by the American Film Institute and received an Academy Honorary Aw ...

and Humphrey Bogart

Humphrey DeForest Bogart (; December 25, 1899 – January 14, 1957), nicknamed Bogie, was an American film and stage actor. His performances in Classical Hollywood cinema films made him an American cultural icon. In 1999, the American Film In ...

, was released later that year and remains the only film with contributions from two Nobel Prize Laureates.

Faulkner was highly critical of what he found in Hollywood, and he wrote letters that were "scathing in tone, painting a miserable portrait of a literary artist imprisoned in a cultural Babylon

''Bābili(m)''

* sux, 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠

* arc, 𐡁𐡁𐡋 ''Bāḇel''

* syc, ܒܒܠ ''Bāḇel''

* grc-gre, Βαβυλών ''Babylṓn''

* he, בָּבֶל ''Bāvel''

* peo, 𐎲𐎠𐎲𐎡𐎽𐎢 ''Bābiru''

* elx, 𒀸𒁀𒉿𒇷 ''Babi ...

." Many scholars have brought attention to the dilemma he experienced and that the predicament had caused him serious unhappiness. In Hollywood he worked with director Howard Hawks

Howard Winchester Hawks (May 30, 1896December 26, 1977) was an American film director, producer and screenwriter of the classic Hollywood era. Critic Leonard Maltin called him "the greatest American director who is not a household name."

A v ...

, with whom he quickly developed a friendship, as they both enjoyed drinking and hunting. Howard Hawks' brother, William Hawks

William Bellinger Hawks (January 29, 1901 – January 10, 1969) was an American film producer.

Career

Hawks attended Yale University, where he was a member of Scroll and Key and graduated in 1923. In his early career, Hawks was a stockbroker. ...

, became Faulkner's Hollywood

Hollywood usually refers to:

* Hollywood, Los Angeles, a neighborhood in California

* Hollywood, a metonym for the cinema of the United States

Hollywood may also refer to:

Places United States

* Hollywood District (disambiguation)

* Hollywood, ...

agent. Faulkner continued to find reliable work as a screenwriter from the 1930s to the 1950s. While staying in Hollywood, Faulkner adopted a "vagrant" lifestyle, living in brief stints in hotels like the Garden of Allah Hotel

The Garden of Allah was a famous hotel in West Hollywood, California (then an unincorporated area of Los Angeles which was usually considered a part of Hollywood, Los Angeles, Hollywood), at 8152 Sunset Boulevard between Crescent Heights and Haven ...

and frequenting the bar at the Roosevelt Hotel at the Musso & Frank Grill

Musso & Frank Grill is a restaurant located at 6667-9 Hollywood Boulevard in the Hollywood neighborhood of Los Angeles. The restaurant opened in 1919 and is named for original owners Joseph Musso and Frank Toulet. It is the oldest restaurant in H ...

where he was said to have regularly gone behind the bar to mix his own Mint Julips. He had an extramarital affair with Hawks' secretary and script girl

A script supervisor (also called continuity supervisor or script) is a member of a film crew who oversees the continuity of the motion picture including wardrobe, props, set dressing, hair, makeup and the actions of the actors during a scene. The ...

, Meta Carpenter.

With the onset of World War II, in 1942, Faulkner tried to join the United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the air service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part of the United States Army Signal ...

but was rejected. He instead worked on local civil defense

Civil defense ( en, region=gb, civil defence) or civil protection is an effort to protect the citizens of a state (generally non-combatants) from man-made and natural disasters. It uses the principles of emergency operations: prevention, miti ...

. Capps (1966), p. 3. The war drained Faulkner of his enthusiasm. He described the war as "bad for writing". Amid this creative slowdown, in 1943, Faulkner began work on a new novel that merged World War I's Unknown Soldier with the Passion of Christ

In Christianity, the Passion (from the Latin verb ''patior, passus sum''; "to suffer, bear, endure", from which also "patience, patient", etc.) is the short final period in the life of Jesus Christ.

Depending on one's views, the "Passion" m ...

. Published over a decade later as ''A Fable

''A Fable'' is a 1954 novel written by the American author William Faulkner. He spent more than a decade and tremendous effort on it, and aspired for it to be "the best work of my life and maybe of my time".

It won the Pulitzer Prize and the Nat ...

'', it won the 1954 Pulitzer Prize. The award for ''A Fable'' was a controversial political choice. The jury had selected Milton Lott

Milton Lott (1916 – 1996) was an author of western novels. He grew up in the Snake River Valley, in Idaho and attended University of California, Berkeley. While there he started writing his first published novel, ''The Last Hunt''. He work ...

's ''The Last Hunt

''The Last Hunt'' is a 1956 American Western film directed by Richard Brooks and produced by Dore Schary. The screenplay was by Richard Brooks from the novel '' The Last Hunt'', by Milton Lott. The music score was by Daniele Amfitheatrof and ...

'' for the prize, but Pulitzer Prize Administrator Professor John Hohenberg convinced the Pulitzer board that Faulkner was long overdue for the award, despite ''A Fable'' being a lesser work of his, and the board overrode the jury's selection, much to the disgust of its members.

By the time of ''The Portable Faulkner''s publication, most of his novels had been out of print.

Nobel Prize and later years

Faulkner was awarded the

Faulkner was awarded the 1949 Nobel Prize in Literature

The 1949 Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded the American author William Faulkner (1897–1962) "for his powerful and artistically unique contribution to the modern American novel." The prize was awarded in 1950. The Nobel Committee for Literatu ...

for "his powerful and artistically unique contribution to the modern American novel". It was awarded at the following year's banquet along with the 1950 Prize to Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British mathematician, philosopher, logician, and public intellectual. He had a considerable influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, linguistics, ...

.

When Faulkner visited Stockholm

Stockholm () is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in Sweden by population, largest city of Sweden as well as the List of urban areas in the Nordic countries, largest urban area in Scandinavia. Approximately 980,000 people liv ...

in December 1950 to receive the Nobel Prize, he met Else Jonsson (1912–1996), who was the widow of journalist Thorsten Jonsson (1910–1950). Jonsson was a reporter for ''Dagens Nyheter

''Dagens Nyheter'' (, ), abbreviated ''DN'', is a daily newspaper in Sweden. It is published in Stockholm and aspires to full national and international coverage, and is widely considered Sweden's newspaper of record.

History and profile

''Da ...

'' from 1943 to 1946, who had interviewed Faulkner in 1946 and introduced his works to Swedish readers. Faulkner and Else had an affair that lasted until the end of 1953. At the banquet where they met in 1950, publisher Tor Bonnier introduced Else as the widow of the man responsible for Faulkner winning the Nobel prize.

Faulkner's Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech on the immortality of the artists, although brief, contained a number of allusions and references to other literary works. However, Faulkner detested the fame and glory that resulted from his recognition. His aversion was so great that his 17-year-old daughter learned of the Nobel Prize only when she was called to the principal's office during the school day. He donated part of his Nobel money "to establish a fund to support and encourage new fiction writers", eventually resulting in the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction

The PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction is awarded annually by the PEN/Faulkner Foundation to the authors of the year's best works of fiction by living American citizens. The winner receives US$15,000 and each of four runners-up receives US$5000. Fi ...

, and donated another part to a local Oxford bank, establishing a scholarship fund to help educate African-American teachers at Rust College

Rust College is a private historically black college in Holly Springs, Mississippi. Founded in 1866, it is the second-oldest private college in the state. Affiliated with the United Methodist Church, it is one of ten historically black colleges ...

in nearby Holly Springs, Mississippi

Holly Springs is a city in, and the county seat of, Marshall County, Mississippi, United States, near the southern border of Tennessee. Near the Mississippi Delta, the area was developed by European Americans for cotton plantations and was dep ...

.

In 1951, the government of France made Faulkner a Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon B ...

.

Faulkner served as the first Writer-in-Residence at the University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a Public university#United States, public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. Founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson, the university is ranked among the top academic institutions in the United S ...

at Charlottesville

Charlottesville, colloquially known as C'ville, is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia. It is the county seat of Albemarle County, which surrounds the city, though the two are separate legal entities. It is named after Queen Cha ...

from February to June 1957 and again in 1958.

In 1961, Faulkner began writing his nineteenth and final novel, ''The Reivers

''The Reivers: A Reminiscence'', published in 1962, is the last novel by the American author William Faulkner. The bestselling novel was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1963. Faulkner previously won this award for his book ''A Fable'', ...

''. The novel is a nostalgic reminiscence, in which an elderly grandfather relates a humorous episode in which he and two boys stole a car to drive to a Memphis

Memphis most commonly refers to:

* Memphis, Egypt, a former capital of ancient Egypt

* Memphis, Tennessee, a major American city

Memphis may also refer to:

Places United States

* Memphis, Alabama

* Memphis, Florida

* Memphis, Indiana

* Memp ...

bordello. In summer 1961, he finished the first draft. During this time, he injured himself in a series of falls.

On June 17, 1962, Faulkner suffered a serious injury in a fall from his horse, which led to thrombosis

Thrombosis (from Ancient Greek "clotting") is the formation of a blood clot inside a blood vessel, obstructing the flow of blood through the circulatory system. When a blood vessel (a vein or an artery) is injured, the body uses platelets (thro ...

. He suffered a fatal heart attack on July 6, 1962, at the age of 64, at Wright's Sanatorium in Byhalia, Mississippi

Byhalia , is a town in Marshall County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 1,302 as of the 2010 census.

History

Byhalia was founded in the 1830s and named after Byhalia Creek, which flows past the site.

Geography

According to the U ...

. Faulkner is buried with his family in St. Peter's Cemetery in Oxford.

Writing

From the early 1920s to the outbreak of World War II, Faulkner published 13 novels and many short stories. This body of work formed the basis of his reputation and earned him the Nobel Prize at age 52. Faulkner's prodigious output include celebrated novels such as ''

From the early 1920s to the outbreak of World War II, Faulkner published 13 novels and many short stories. This body of work formed the basis of his reputation and earned him the Nobel Prize at age 52. Faulkner's prodigious output include celebrated novels such as ''The Sound and the Fury

''The Sound and the Fury'' is a novel by the American author William Faulkner. It employs several narrative styles, including stream of consciousness. Published in 1929, ''The Sound and the Fury'' was Faulkner's fourth novel, and was not immedi ...

'' (1929), ''As I Lay Dying

''As I Lay Dying'' is a 1930 Southern Gothic novel by American author William Faulkner. Faulkner's fifth novel, it is consistently ranked among the best novels of 20th-century literature.The New Lifetime Reading Plan: The Classical Guide to Wor ...

'' (1930), ''Light in August

''Light in August'' is a 1932 novel by the Southern American author William Faulkner. It belongs to the Southern gothic and modernist literary genres.

Set in the author's present day, the interwar period, the novel centers on two strangers, a ...

'' (1932), and ''Absalom, Absalom!

''Absalom, Absalom!'' is a novel by the American author William Faulkner, first published in 1936. Taking place before, during, and after the American Civil War, it is a story about three families of the American South, with a focus on the life o ...

'' (1936). He was also a prolific writer of short stories

A short story is a piece of prose fiction that typically can be read in one sitting and focuses on a self-contained incident or series of linked incidents, with the intent of evoking a single effect or mood. The short story is one of the oldest t ...

.

Faulkner's first short story collection, ''These 13

''These 13'' is a 1931 collection of short stories written by William Faulkner, and dedicated to his first daughter, Alabama, who died nine days after her birth on January 11, 1931, and to his wife Estelle. No longer in print, ''These 13'' is now ...

'' (1931), includes many of his most acclaimed (and most frequently anthologized

In book publishing, an anthology is a collection of literary works chosen by the compiler; it may be a collection of plays, poems, short stories, songs or excerpts by different authors.

In genre fiction, the term ''anthology'' typically catego ...

) stories, including "A Rose for Emily

"A Rose for Emily" is a short story by American author William Faulkner, first published on April 30, 1930, in an issue of '' The Forum''. The story takes place in Faulkner's fictional Jefferson, Mississippi, in the equally fictional county of ...

", "Red Leaves

"Red Leaves" is a short story by American author William Faulkner. First published in the ''Saturday Evening Post'' on October 25, 1930, it was one of Faulkner's first stories to appear in a national magazine. The next year the story was included i ...

", "That Evening Sun

"That Evening Sun" is a short story by the American author William Faulkner, published in 1931 in the collection '' These 13'', which included Faulkner's most anthologized story, "A Rose for Emily". The story was originally published, in a slight ...

", and " Dry September". He set many of his short stories and novels in Yoknapatawpha County

Yoknapatawpha County () is a fictional Mississippi county created by the American author William Faulkner, largely based upon and inspired by Lafayette County, Mississippi, and its county seat of Oxford (which Faulkner renamed "Jefferson"). Faulk ...

—which was based on and nearly geographically identical to Lafayette County (of which his hometown of Oxford, Mississippi

Oxford is a city and college town in the U.S. state of Mississippi. Oxford lies 75 miles (121 km) south-southeast of Memphis, Tennessee, and is the county seat of Lafayette County. Founded in 1837, it was named after the British city of Oxf ...

, is the county seat). Yoknapatawpha was Faulkner's "postage stamp", and the bulk of work that it represents is widely considered by critics to amount to one of the most monumental fictional creations in the history of literature. Three of his novels, ''The Hamlet

''The Hamlet'' is a novel by the American author William Faulkner, published in 1940, about the fictional Snopes family of Mississippi. Originally a standalone novel, it was later followed by '' The Town'' (1957), and '' The Mansion'' (1959), ...

'', '' The Town'' and ''The Mansion

The Mansion or The Mansions may refer to:

Books

* ''The Interior Castle'', also known as ''The Mansions'' (1577), a spiritual guide written by Teresa of Ávila

* ''The Mansion'' (novel), a 1959 book written by novelist William Faulkner

Buildings ...

'', known collectively as the Snopes Trilogy, document the town of Jefferson and its environs, as an extended family headed by Flem Snopes insinuates itself into the lives and psyches of the general populace. Yoknapatawpha County has been described as a mental landscape.

His short story "A Rose for Emily

"A Rose for Emily" is a short story by American author William Faulkner, first published on April 30, 1930, in an issue of '' The Forum''. The story takes place in Faulkner's fictional Jefferson, Mississippi, in the equally fictional county of ...

" was his first story published in a major magazine, the ''Forum'', but received little attention from the public. After revisions and reissues, it gained popularity and is now considered one of his best.

Faulkner wrote two volumes of poetry which were published in small printings, ''The Marble Faun'' (1924), and ''A Green Bough'' (1933), and a collection of mystery stories, ''Knight's Gambit'' (1949).

Style and technique

Faulkner was known for his experimental style with meticulous attention todiction

Diction ( la, dictionem (nom. ), "a saying, expression, word"), in its original meaning, is a writer's or speaker's distinctive vocabulary choices and style of expression in a poem or story.Crannell (1997) ''Glossary'', p. 406 In its common meanin ...

and cadence

In Western musical theory, a cadence (Latin ''cadentia'', "a falling") is the end of a phrase in which the melody or harmony creates a sense of full or partial resolution, especially in music of the 16th century onwards.Don Michael Randel (1999) ...

. In contrast to the minimalist

In visual arts, music and other media, minimalism is an art movement that began in post–World War II in Western art, most strongly with American visual arts in the 1960s and early 1970s. Prominent artists associated with minimalism include Don ...

understatement of his contemporary Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer, and journalist. His economical and understated style—which he termed the iceberg theory—had a strong influence on 20th-century fic ...

, Faulkner made frequent use of "stream of consciousness

In literary criticism, stream of consciousness is a narrative mode or method that attempts "to depict the multitudinous thoughts and feelings which pass through the mind" of a narrator. The term was coined by Daniel Oliver (physician), Daniel Ol ...

" in his writing, and wrote often highly emotional, subtle, cerebral, complex, and sometimes Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

or grotesque

Since at least the 18th century (in French and German as well as English), grotesque has come to be used as a general adjective for the strange, mysterious, magnificent, fantastic, hideous, ugly, incongruous, unpleasant, or disgusting, and thus ...

stories of a wide variety of characters including former slaves or descendants of slaves, poor white, agrarian, or working-class Southerners, and Southern aristocrats.

In an interview with ''The Paris Review

''The Paris Review'' is a quarterly English-language literary magazine established in Paris in 1953 by Harold L. Humes, Peter Matthiessen, and George Plimpton. In its first five years, ''The Paris Review'' published works by Jack Kerouac, Philip ...

'' in 1956, Faulkner remarked: Let the writer take up surgery or bricklaying if he is interested in technique. There is no mechanical way to get the writing done, no shortcut. The young writer would be a fool to follow a theory. Teach yourself by your own mistakes; people learn only by error. The good artist believes that nobody is good enough to give him advice. He has supreme vanity. No matter how much he admires the old writer, he wants to beat him.Writer

Flannery O'Connor

Mary Flannery O'Connor (March 25, 1925August 3, 1964) was an American novelist, short story writer and essayist. She wrote two novels and 31 short stories, as well as a number of reviews and commentaries.

She was a Southern writer who often ...

stated that "the presence alone of Faulkner in our midst makes a great difference in what the writer can and cannot permit himself to do. Nobody wants his mule and wagon stalled on the same track the ''Dixie Limited'' is roaring down".

Faulkner's contemporary critical reception was mixed, with ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' noting that many critics regarded his work as "raw slabs of pseudorealism that had relatively little merit as serious writing". His style has been described as "impenetrably convoluted".

Themes and analysis

Faulkner's work has been examined by many critics from a wide variety of critical perspectives, including his position on slavery in the South and his view that desegregation was not an idea to be forced, arguing desegregation should "go slow" so as not to upend the southern way of life. The essayist and novelistJames Baldwin

James Arthur Baldwin (August 2, 1924 – December 1, 1987) was an American writer. He garnered acclaim across various media, including essays, novels, plays, and poems. His first novel, '' Go Tell It on the Mountain'', was published in 1953; de ...

was highly critical of his views around integration.

The New Critics

New Criticism was a formalist movement in literary theory that dominated American literary criticism in the middle decades of the 20th century. It emphasized close reading, particularly of poetry, to discover how a work of literature functioned as ...

became interested in Faulkner's work, with Cleanth Brooks

Cleanth Brooks ( ; October 16, 1906 – May 10, 1994) was an American literary critic and professor. He is best known for his contributions to New Criticism in the mid-20th century and for revolutionizing the teaching of poetry in American higher ...

writing ''The Yoknapatawpha Country'' and Michael Millgate writing ''The Achievement of William Faulkner''. Since then, critics have looked at Faulkner's work using other approaches, such as feminist and psychoanalytic methods. Faulkner's works have been placed within the literary traditions of modernism

Modernism is both a philosophy, philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western world, Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new fo ...

and the Southern Renaissance

The Southern Renaissance (also known as Southern Renascence) was the reinvigoration of American Southern literature in the 1920s and 1930s with the appearance of writers such as William Faulkner, Thomas Wolfe, Caroline Gordon, Margaret Mitchell, K ...

.

French philosopher Albert Camus

Albert Camus ( , ; ; 7 November 1913 – 4 January 1960) was a French philosopher, author, dramatist, and journalist. He was awarded the 1957 Nobel Prize in Literature at the age of 44, the second-youngest recipient in history. His work ...

wrote that Faulkner successfully imported classical tragedy

Tragedy (from the grc-gre, τραγῳδία, ''tragōidia'', ''tragōidia'') is a genre of drama based on human suffering and, mainly, the terrible or sorrowful events that befall a main character. Traditionally, the intention of tragedy ...

into the 20th century through his "interminably unwinding spiral of words and sentences that conducts the speaker to the abyss of sufferings buried in the past".

Legacy

Influence

According to critic and translator Valerie Miles, Faulkner's influence on Latin American fiction is considerable, with fictional worlds created byGabriel García Márquez

Gabriel José de la Concordia García Márquez (; 6 March 1927 – 17 April 2014) was a Colombian novelist, short-story writer, screenwriter, and journalist, known affectionately as Gabo () or Gabito () throughout Latin America. Considered one ...

(Macondo

Macondo is a fictional town described in Gabriel García Márquez's novel '' One Hundred Years of Solitude''. It is the home town of the Buendía family.

Aracataca

Macondo is often supposed to draw from García Márquez's childhood town, Aracat ...

) and Juan Carlos Onetti

Juan Carlos Onetti Borges (July 1, 1909 – May 30, 1994) was a Uruguayan novelist and author of short stories.

Early life

Onetti was born in Montevideo, Uruguay. He was the son of Carlos Onetti, a customs official, and Honoria Borges, who b ...

(Santa Maria) being "very much in the vein of" Yoknapatawpha: "Carlos Fuentes

Carlos Fuentes Macías (; ; November 11, 1928 – May 15, 2012) was a Mexican novelist and essayist. Among his works are ''The Death of Artemio Cruz'' (1962), '' Aura'' (1962), '' Terra Nostra'' (1975), ''The Old Gringo'' (1985) and ''Christophe ...

's ''The Death of Artemio Cruz

''The Death of Artemio Cruz'' ( es, La muerte de Artemio Cruz, ) is a novel written in 1962 by Mexican writer Carlos Fuentes. It is considered to be a milestone in the Latin American Boom.

Plot summary

Artemio Cruz, a corrupt soldier, politician, ...

'' wouldn't exist if not for ''As I Lay Dying

''As I Lay Dying'' is a 1930 Southern Gothic novel by American author William Faulkner. Faulkner's fifth novel, it is consistently ranked among the best novels of 20th-century literature.The New Lifetime Reading Plan: The Classical Guide to Wor ...

''". Fuentes himself cited Faulkner as one of the writers most important to him. Faulkner also had great influence on Mario Vargas Llosa

Jorge Mario Pedro Vargas Llosa, 1st Marquess of Vargas Llosa (born 28 March 1936), more commonly known as Mario Vargas Llosa (, ), is a Peruvian novelist, journalist, essayist and former politician, who also holds Spanish citizenship. Vargas Ll ...

, particularly on the early novels ''The Time of the Hero

''The Time of the Hero'' (original title: ''La ciudad y los perros'', literally "The City and the Dogs") is a 1963 novel by Peruvian writer and Nobel laureate Mario Vargas Llosa. It was Vargas Llosa's first novel and is set among the cadets at t ...

'', ''The Green House

''The Green House'' (Original title: ''La Casa Verde'') is the second novel by the Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa, published in 1966. The novel is set over a period of forty years (from the early part of the 20th century to the 1960s) in tw ...

'' and ''Conversation in the Cathedral

''Conversation in The Cathedral'' (original title: ''Conversación en La catedral'') is a 1969 novel by Spanish-Peruvian writer and essayist Mario Vargas Llosa, translated by Gregory Rabassa. One of Vargas Llosa's major works, it is a portrayal of ...

''. Vargas Llosa has claimed that during his student years he learned more from Yoknapatawpha than from classes.

The works of William Faulkner are a clear influence on the French novelist Claude Simon

Claude Simon (; 10 October 1913 – 6 July 2005) was a French novelist, and was awarded the 1985 Nobel Prize in Literature.

Biography

Claude Simon was born in Tananarive on the isle of Madagascar. His parents were French, his father being a ...

, and the Portuguese novelist António Lobo Antunes

António Lobo Antunes, GCSE (; born 1 September 1942) is a Portuguese novelist and retired medical doctor. He has been named as a contender for the Nobel Prize in Literature. He has been awarded the 2000 Austrian State Prize, the 2003 Ovid ...

. Cormac McCarthy

Cormac McCarthy (born Charles Joseph McCarthy Jr., July 20, 1933) is an American writer who has written twelve novels, two plays, five screenplays and three short stories, spanning the Western and post-apocalyptic genres. He is known for his gr ...

has been described as a "disciple of Faulkner".

After his death, Estelle and their daughter, Jill, lived at Rowan Oak until Estelle's death in 1972. The property was sold to the University of Mississippi

The University of Mississippi (byname Ole Miss) is a public research university that is located adjacent to Oxford, Mississippi, and has a medical center in Jackson. It is Mississippi's oldest public university and its largest by enrollment.

...

that same year. The house and furnishings are maintained much as they were in Faulkner's day. Faulkner's scribblings are preserved on the wall, including the day-by-day outline covering a week he wrote on the walls of his small study to help him keep track of the plot twists in his novel, ''A Fable

''A Fable'' is a 1954 novel written by the American author William Faulkner. He spent more than a decade and tremendous effort on it, and aspired for it to be "the best work of my life and maybe of my time".

It won the Pulitzer Prize and the Nat ...

''.

Some of Faulkner's works have been adapted into films such as James Franco

James Edward Franco (born April 19, 1978) is an American actor and filmmaker. For his role in '' 127 Hours'' (2010), he was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actor. Franco is known for his roles in films, such as Sam Raimi's ''Spider-Ma ...

's ''As I Lay Dying

''As I Lay Dying'' is a 1930 Southern Gothic novel by American author William Faulkner. Faulkner's fifth novel, it is consistently ranked among the best novels of 20th-century literature.The New Lifetime Reading Plan: The Classical Guide to Wor ...

'' (2013). They have received a polarized response, with many critics contending that Faulkner's works are "unfilmable". Faulkner's final work, ''The Reivers'', was adapted into a 1969 film starring Steve McQueen

Terrence Stephen McQueen (March 24, 1930November 7, 1980) was an American actor. His antihero persona, emphasized during the height of the counterculture of the 1960s, made him a top box-office draw for his films of the late 1950s, 1960s, and 1 ...

.

Faulkner remains especially popular in France, where a 2009 poll found him the second most popular writer (after only Marcel Proust

Valentin Louis Georges Eugène Marcel Proust (; ; 10 July 1871 – 18 November 1922) was a French novelist, critic, and essayist who wrote the monumental novel ''In Search of Lost Time'' (''À la recherche du temps perdu''; with the previous Eng ...

). Contemporary Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (, ; ; 21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was one of the key figures in the philosophy of existentialism (and phenomenology), a French playwright, novelist, screenwriter, political activist, biographer, and litera ...

stated that "for young people in France, Faulkner is a god", and Albert Camus

Albert Camus ( , ; ; 7 November 1913 – 4 January 1960) was a French philosopher, author, dramatist, and journalist. He was awarded the 1957 Nobel Prize in Literature at the age of 44, the second-youngest recipient in history. His work ...

made a stage adaptation of Faulkner's ''Requiem for a Nun

''Requiem for a Nun'' is a work of fiction written by William Faulkner. It is a sequel to Faulkner's early novel ''Sanctuary'', which introduced the characters of Temple Drake, her friend (later husband) Gowan Stevens, and Gowan's uncle Gavin Ste ...

''.

He also won the U.S. National Book Award

The National Book Awards are a set of annual U.S. literary awards. At the final National Book Awards Ceremony every November, the National Book Foundation presents the National Book Awards and two lifetime achievement awards to authors.

The Nat ...

twice, for ''Collected Stories'' in 1951"National Book Awards – 1951".

National Book Foundation

The National Book Foundation (NBF) is an American nonprofit organization established, "to raise the cultural appreciation of great writing in America". Established in 1989 by National Book Awards, Inc.,Edwin McDowell. "Book Notes: 'The Joy Luc ...

. Retrieved 2012-03-31. (With essays by Neil Baldwin and Harold Augenbraum from the Awards 50- and 60-year anniversary publications.) and ''A Fable

''A Fable'' is a 1954 novel written by the American author William Faulkner. He spent more than a decade and tremendous effort on it, and aspired for it to be "the best work of my life and maybe of my time".

It won the Pulitzer Prize and the Nat ...

'' in 1955."National Book Awards – 1955".

National Book Foundation

The National Book Foundation (NBF) is an American nonprofit organization established, "to raise the cultural appreciation of great writing in America". Established in 1989 by National Book Awards, Inc.,Edwin McDowell. "Book Notes: 'The Joy Luc ...

. Retrieved 2012-03-31. (With acceptance speech by Faulkner and essays by Neil Baldwin and Harold Augenbraum from the Awards 50- and 60-year anniversary publications.)

The United States Postal Service

The United States Postal Service (USPS), also known as the Post Office, U.S. Mail, or Postal Service, is an independent agency of the executive branch of the United States federal government responsible for providing postal service in the U ...

issued a 22-cent postage stamp in his honor on August 3, 1987. Faulkner had once served as Postmaster at the University of Mississippi, and in his letter of resignation in 1923 wrote:

As long as I live under the capitalistic system, I expect to have my life influenced by the demands of moneyed people. But I will be damned if I propose to be at the beck and call of every itinerant scoundrel who has two cents to invest in a postage stamp. This, sir, is my resignation.On October 10, 2019, a

Mississippi Writers Trail The Mississippi Writers Trail is a series of historical markers which celebrate the literary, social, historical, and cultural contributions of Mississippi's most acclaimed and influential writers. An advisory committee of state cultural agencies ov ...

historical marker was installed at Rowan Oak

Rowan Oak is William Faulkner's former home in Oxford, Mississippi. It is a primitive Greek Revival house built in the 1840s by Colonel Robert Sheegog, an Irish immigrant planter from Tennessee. Faulkner purchased the house when it was in disrepai ...

in Oxford, Mississippi honoring the contributions of William Faulkner to the American literary landscape.

Collections

The manuscripts of most of Faulkner's works, correspondence, personal papers, and over 300 books from his working library reside at theAlbert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library

The Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library at the University of Virginia is a research library that specializes in American history and literature, history of Virginia and the southeastern United States, the history of the University ...

at the University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a Public university#United States, public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. Founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson, the university is ranked among the top academic institutions in the United S ...

, where he spent much of his time in his final years. The library also houses some of the writer's personal effects and the papers of major Faulkner associates and scholars, such as his biographer Joseph Blotner, bibliographer Linton Massey, and Random House editor Albert Erskine.

Southeast Missouri State University

Southeast Missouri State University (SEMO) is a public university in Cape Girardeau, Missouri. In addition to the main campus, the university has four regional campuses offering full degree programs and a secondary campus housing the Holland Col ...

, where the Center for Faulkner Studies is located, also owns a generous collection of Faulkner materials, including first editions, manuscripts, letters, photographs, artwork, and many materials pertaining to Faulkner's time in Hollywood. The university possesses many personal files and letters kept by Joseph Blotner, along with books and letters that once belonged to Malcolm Cowley. The university achieved the collection due to a generous donation by Louis Daniel Brodsky, a collector of Faulkner materials, in 1989.

Further significant Faulkner materials reside at the University of Mississippi

The University of Mississippi (byname Ole Miss) is a public research university that is located adjacent to Oxford, Mississippi, and has a medical center in Jackson. It is Mississippi's oldest public university and its largest by enrollment.

...

, the Harry Ransom Center

The Harry Ransom Center (until 1983 the Humanities Research Center) is an archive, library and museum at the University of Texas at Austin, specializing in the collection of literary and cultural artifacts from the Americas and Europe for the pur ...

, and the New York Public Library

The New York Public Library (NYPL) is a public library system in New York City. With nearly 53 million items and 92 locations, the New York Public Library is the second largest public library in the United States (behind the Library of Congress ...

.

The Random House records at Columbia University also include letters by and to Faulkner.Jaillant (2014)

In 1966, the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a fort, since it sits on strategic high groun ...

dedicated a William Faulkner Room in its library.

Selected list of works

* ''The Sound and the Fury

''The Sound and the Fury'' is a novel by the American author William Faulkner. It employs several narrative styles, including stream of consciousness. Published in 1929, ''The Sound and the Fury'' was Faulkner's fourth novel, and was not immedi ...

'' (1929)

* ''As I Lay Dying

''As I Lay Dying'' is a 1930 Southern Gothic novel by American author William Faulkner. Faulkner's fifth novel, it is consistently ranked among the best novels of 20th-century literature.The New Lifetime Reading Plan: The Classical Guide to Wor ...

'' (1930)

* ''Light in August

''Light in August'' is a 1932 novel by the Southern American author William Faulkner. It belongs to the Southern gothic and modernist literary genres.

Set in the author's present day, the interwar period, the novel centers on two strangers, a ...

'' (1932)

* ''Absalom, Absalom!

''Absalom, Absalom!'' is a novel by the American author William Faulkner, first published in 1936. Taking place before, during, and after the American Civil War, it is a story about three families of the American South, with a focus on the life o ...

'' (1936)

* '' The Wild Palms'' (1939)

* ''Go Down, Moses

"Go Down Moses" is a spiritual phrase that describes events in the Old Testament of the Bible, specifically Exodus 5:1: "And the LORD spake unto Moses, Go unto Pharaoh, and say unto him, Thus saith the LORD, Let my people go, that they may se ...

'' (1942)

* ''The Reivers

''The Reivers: A Reminiscence'', published in 1962, is the last novel by the American author William Faulkner. The bestselling novel was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1963. Faulkner previously won this award for his book ''A Fable'', ...

'' (1962)

Filmography

*''Flesh

Flesh is any aggregation of soft tissues of an organism. Various multicellular organisms have soft tissues that may be called "flesh". In mammals, including humans, ''flesh'' encompasses muscle

Skeletal muscles (commonly referred to as mu ...

'' (1932)

*''Today We Live

''Today We Live'' is a 1933 American pre-Code romance drama film produced and directed by Howard Hawks and starring Joan Crawford, Gary Cooper, Robert Young and Franchot Tone.

'' (1933)

*''The Story of Temple Drake